Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The October Revolution abolished Christianity

and the Agapetos formula as the regime’s ideology.

The Bolsheviks replaced it with Marxist-Leninist di-

alectical historical materialism. Stalin, sensing a

threat from the United Kingdom in 1927, used the

new ideology to legitimize his launching of the

third service class revolution in 1928.

The Soviet service state proved unable to man-

age the economy efficiently, but the service class

remained during the Leonid Brezhnev (1964–1982),

Yuri Andropov (1982–1984), and Konstantin Cher-

nenko (1984–1985) years. The Soviet service class

had already begun to generate into a privileged elite

(what Milovan Djilas termed “the new class”) by

the end of the 1930s, and this degeneration had

turned into a rout by 1985. By the middle of the

1970s “the working class pretended to work and

the state pretended to pay them.” The general trend

was for people to go to work to socialize with their

friends, not to produce anything. By the time of

the coup of August 19, 1991, attempting to over-

throw Mikhail Gorbachev, the privileged elite (the

“nomenklatura”) rode around in their own private

motorcars and went straight to the head of long

lines for ordinary consumer goods such as news-

papers and magazines while getting most of their

goods from closed stores open only to the privileged

elite. It was obvious that the Soviet service state

was no longer working, could not make the econ-

omy grow or improve the lives of its subjects, and

was little more than a debauchery of corruption.

Gorbachev, another believer in socialism, tried to

reform the system, but it proved impossible. The

service state lost its teeth when he repealed Article

6 of the Brezhnev constitution, which had given the

Communist Party a monopoly on Soviet political

life. The Communist Party had also assumed a mo-

nopoly on all elite positions, so that one had to be

a member of the CPSU to hold many jobs. That had

not been true during the times of Stalin and Nikita

Khrushchev. This change was another sign of the

degeneration of the service state under Brezhnev.

When Gorbachev delivered the coup de grace to

the Soviet service state, no one wept. The service

state was a major Russian “contribution” to the

human experience. Whether there ever will be a

fourth service class revolution remains to be seen.

See also: ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; ECONOMY,

TSARIST; INDUSTRIALIZATION; MILITARY, IMPERIAL

ERA; MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET; RUSSIAN

ORTHODOX CHURCH; SERFDOM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1971). Enserfment and Military Change in

Muscovy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hellie, Richard. (1987). “What Happened? How Did He

Get Away with It? Ivan Groznyi’s Paranoia and the

Problem of Institutional Restraints.” Russian History

14:199–224.

Hellie, Richard. (2002). “The Role of the State in Seven-

teenth-Century Muscovy.” In Modernizing Muscovy,

ed. J. T. Kotilaine and Marshall T. Poe. Leiden: Brill.

Kliuchevskii, V. O. (1960). A History of Russia. 5 vols.,

tr. C. J. Hogarth. New York: Russell & Russell.

Swianiewicz, Stanislaw. (1965). Forced Labor and Economic

Development: An Enquiry into the Experience of Soviet

Industrialization. London: Oxford University Press.

Tucker, Robert C. (1990). Stalin in Power: The Revolution

from Above, 1928–1941. New York: Norton.

Voslensky, Michael. (1984). Nomenklatura: The Soviet

Ruling Class, tr. Eric Mosbacher. Garden City, NY:

Doubleday.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

SEVASTOPOL

City and naval base on the southwestern tip of the

Crimean Peninsula in Ukraine.

With its excellent harbors and anchorages, Sev-

astopol has an advantageous location from which

to conduct operations in the Black Sea. The city

stands on the southern shore of Sevastopol Bay and

has a population of 390,000—75 percent Russian

and 20 percent Ukrainian. The site of ancient set-

tlements, modern Sevastopol was founded by

Prince Grigory Potemkin in 1783 after the conquest

of the Crimean Khanate. Admiral F.F. Mekenzy,

commander of the newly created Black Sea Fleet,

placed a naval station there, and in 1784 the set-

tlement was named Sevastopol.

In 1804 Alexander I’s government declared Sev-

astopol the primary naval base of the Black Sea

Fleet. The naval base and the city grew significantly

during the second quarter of the nineteenth cen-

tury when Admiral Mikhail Lazarev served as fleet

commander. By 1844 the city had a population of

more than forty thousand, making it the largest

city in Crimea. Sevastopol became the major base

for fitting out and repairing warships. Its defenses

grew in extent and quality.

In 1853 Admiral Pavel Nakhimov’s squadron

sailed from there to Sinope, where it annihilated a

SEVASTOPOL

1373

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Turkish squadron. During the Crimean War, An-

glo-French forces besieged Sevastopol. The defense

was immortalized by Leo Tolstoy, one of the de-

fenders, in his Sevastopol Tales. Sevastopol fell to

the Anglo-French forces in September 1855.

Following the Crimean War, Sevastopol suf-

fered decline, because the peace treaty denied Rus-

sia the right to maintain a fleet in the Black Sea.

With the remilitarization of the Black Sea after

1870 Sevastopol regained its importance as a naval

base for a modern ironclad fleet.

Sevastopol was associated with rebellion, mu-

tiny, and civil war. In 1830 government restric-

tions to combat a cholera epidemic set off a revolt

among sailors and civilians. In June 1905 the bat-

tleship Potemkin sailed from Sevastopol on its way

to mutiny over bad meat. During the Russian civil

war Sevastopol was the headquarters of Baron Pe-

ter Wrangel’s White Army. The Red Army under

Mikhail Frunze stormed Crimea in October 1920,

and Wrangel evacuated his army to Istanbul.

During World War II Sevastopol was the site

of an eight-month siege by German and Ruman-

ian forces under Field Marshal Erich von Manstein

and fell in July 1942. On May 9, 1944, the Soviet

Fourth Ukrainian Front under the command of

Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin liberated the city.

Following the end of the existence of the Soviet

Union in 1991, Russia and Ukraine entered into

negotiations over Sevastopol. During the early

twenty-first century the city is a special region

within Ukraine, not under the government of

Crimea, and the Russian and Ukrainian navies

share the naval base.

See also: BLACK SEA FLEET; CRIMEA; CRIMEAN WAR;

UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS; WHITE ARMY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Curtiss, John Shelton. (1979). Russia’s Crimean War.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Tolstoy, Leo. (1961). Sebastopol. Ann Arbor: University

of Michigan Press.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

SEVEN-YEAR PLAN

Following the rise of Nikita Khrushchev to primacy

among the leaders of the Soviet Union, the sixth

five-year plan (1956–1960) was abandoned as in-

feasible, leaving the country without a perspective

plan for the first time in three decades. In one of

his many reorganizations, Khrushchev substituted

a Seven-Year Plan to run from 1959 to 1965. It in-

cluded his new priorities for a much larger chem-

ical industry, more housing, substitution of oil and

gas for coal in the production of electricity and for

powering the railroads, and more emphasis on

agriculture, especially in the eastern areas.

Planned targets for 1965 were ambitious, and

some were even raised in October 1961. Despite

considerable growth of housing construction, meat

production, and consumer durables, fulfillment

was not achieved in many areas. Khrushchev had

grand hopes for the chemical industry and agri-

culture, but the targets for mineral fertilizers, syn-

thetic fibers, and the grain harvest were all missed.

Civilian investment rates fell, and national income

(defined in Marxist concepts) was underfulfilled by

four to seven percent. Gross production volume of

producers goods did exceed the long-term plan,

with an index (1959⫽100) of 196 achieved versus

185–188 planned, while consumer goods fell be-

low it, 160 actual versus 162–165 planned.

The shortfalls can perhaps be explained by the

strain of increased expenditures on space and mil-

itary ventures in these years and the complexity of

planning for more tasks. The continual sovnarkhoz

(regional economic council) reorganizations, which

put considerable strain on Gosplan to coordinate

supplies, probably also had a negative impact on

overall results.

See also: FIVE-YEAR PLANS; GOSPLAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nove, Alec. (1969). An Economic History of the U.S.S.R.

London: Allen Lane.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

SEVEN YEARS’ WAR

The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) involved nearly

every European state and was watershed in world

history. It arose as a result of the Anglo-French

colonial rivalry and because of the growing might

of Prussia in central Europe, which threatened the

interests of Austria, France, and Russia. The out-

SEVEN-YEAR PLAN

1374

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

come ensured that England became the dominant

power in North America, and the war consolidated

the growing power and prestige of Frederick the

Great’s Prussia. For this, he could thank Russia and

its bizarre participation in the war. Internally, Russ-

ian actions in the Seven Years’ War also brought

about a palace coup and the subsequent rule of

Catherine II.

Prussia had emerged as a potential European

power by the middle of the eighteenth century. Un-

der Frederick II (r. 1740–1786), Prussian policies

became increasingly ambitious. Frederick wanted to

consolidate his power and territories gained at the

expense of Austria during the 1840s. Austria, for

its part, desired a return of territories such as Sile-

sia. Russia and France also worried over Prussian

power and potential incursions near their respec-

tive borders. When war broke out between France

and England over their North American territories,

Prussia signed an alliance with England in January

1756. The alliance brought a rapprochement be-

tween France and Austria. By the end of 1756, Rus-

sia signed a new alliance with its traditional ally,

Austria. The sides had been drawn.

After war broke out in 1756 on the continent,

Frederick’s forces enjoyed success against the Aus-

trians. By April 1756 the Prussians reached Prague.

In the Bohemian capital the Austrians rallied, and

Frederick’s forces retreated. At that point Austria’s

allies, including Russia, entered the conflict. Despite

the numbers stacked against him, Frederick con-

tinued to win surprising victories, and 1757 es-

tablished his reputation as a brilliant commander.

The following year brought mixed results and

mounting casualties for the Russians, who lost

twelve thousand troops at August’s Battle of Zorn-

dorf. In 1759 the allies, and particularly Russia,

ratcheted up the pressure. Led by General Pyotr

Saltykov, the Russian army occupied Frankfurt in

June 1759. By 1760 Frederick had only half the

numbers of his Russian and Austrian opponents,

who began to close the circle against Frederick.

Russian commanders in particular focused on

Berlin, and even occupied the Prussian capital for

three days in September and October 1760. Ex-

hausted by the continuous marching demanded of

eighteenth-century warfare, the two sides fought

no serious battles for the rest of 1760 and most of

1761. Frederick’s situation, however, was grave.

Russia and Austria could count on more soldiers

and supplies, and Prussia was cut off from Silesia,

a major supplier of food.

Then the situation changed dramatically. On

January 5, 1762, the Empress Elizabeth died. Her

successor, Peter III, was a fervent admirer of Freder-

ick II and all things Prussian. When he took the

throne, Peter ended the war with Prussia, called his

troops back, and returned all territorial gains. As a

result, Frederick recovered and defeated the Austri-

ans. France, defeated in North America and more dis-

interested about the continental war, also signed a

treaty with Prussia. Frederick’s “miracle” had resulted

from Russia’s flip-flop, and his victory brought the

first step toward Prussian domination of Germany.

At home, Peter III’s decision ran counter to Rus-

sia’s strategic and political interests. Contempo-

raries called the conflict the “Prussian War,” and

even popular prints of the time depicted the war as

a struggle solely between Russia and Prussia. The

decision to hand Frederick victory thus did not go

over well within any segment of the population.

Catherine, Peter’s German wife, led a palace coup

against her husband that toppled him from power

on July 9, 1762. Catherine II’s rise to power would

have been inconceivable had it not been for Russia’s

participation in the war.

See also: AUSTRIA, RELATIONS WITH; CATHERINE II; ELIZ-

ABETH; FRANCE, RELATIONS WITH; PETER III; PRUSSIA,

RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Fred. (2001). Crucible of Empire: The Seven Years’

War and the Fate of Empire in British North America,

1754–1766. New York: Vintage.

Keep, John L. H. (2002). “The Russian Army in the Seven

Years’ War.” In The Military and Society in Russia,

1450–1917, ed. Eric Lohr and Marshall Poe. Leiden:

Brill.

Leonard, Carol. (1993). Reform and Regicide: The Reign of Pe-

ter III of Russia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

S

TEPHEN

M. N

ORRIS

SHAHUMIAN, STEPAN GEORGIEVICH

(1878–1918), Bolshevik party activist and theorist

on the nationality question; principal leader of the

Bolsheviks in Baku during the Russian Revolution

who perished as one of the famous Twenty-Six

Baku Commissars.

Born into an Armenian family in Tiflis (Tbil-

isi), the young Shahumian was educated in local

SHAHUMIAN, STEPAN GEORGIEVICH

1375

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

schools before entering the Riga Polytechnic Insti-

tute in 1900. Active in Armenian student political

circles, he turned toward Marxism in Riga. Expelled

for his political activities, Shahumian continued his

studies at the University of Berlin, where he joined

the Russian Social Democratic Workers’ Party (RS-

DRP). He grew close to Vladimir Lenin and the Bol-

sheviks, translated the Communist Manifesto into

Armenian, and was elected a delegate to the Fourth

(Stockholm) and Fifth (London) Congresses of the

RSDRP. Shahumian was active in the strike move-

ment in Baku during the first Russian revolution

(1905–1907) and throughout the years of reaction

and repression of the labor movement, and was ar-

rested and imprisoned several times. When the Feb-

ruary Revolution broke out, he returned from exile

in Astrakhan and assumed leadership of the Baku

Bolsheviks.

Elected chairman of the Baku Soviet of Work-

ers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, Shahumian was the

most important figure in Baku politics in 1917 and

1918. After the October Revolution, Lenin’s gov-

ernment appointed him Extraordinary Commissar

for the Affairs of the Caucasus. Shahumian headed

the Council of People’s Commissars, the de facto

government of the Baku Commune, from April

through July 1918. Although he was moderate in

temperament and tolerant of diverse political par-

ties, his brief tenure was marked by a brash at-

tempt to expand Soviet power throughout the

Caucasus by military means. As the Turkish army

approached Baku, the soviet voted to invite Persia-

based British forces to defend the city. Shahumian’s

government stepped down and soon was arrested.

On September 20, 1918, anti-Bolsheviks brutally

executed twenty-six commissars, among them

Shahumian, in the deserts of Transcaspia (now

Turkmenistan). The Soviet government blamed the

British for their deaths and commemorated them

as martyrs to the revolution. Reburied in a mass

grave in Baku, they became the inspiration for

paintings, songs, poems, and films. But with the

fall of the Soviet Union, anticommunist Azerbai-

janis disinterred their corpses and destroyed their

monuments.

See also: ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS; BAKU; BOLSHEVISM;

CAUCASUS; SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC WORKERS PARTY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Suny, Ronald Grigor. (1972). The Baku Commune,

1917–1918: Class and Nationality in the Russian Rev-

olution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

R

ONALD

G

RIGOR

S

UNY

SHAKHRAI, SERGEI MIKHAILOVICH

(b. 1956), lawyer and former minister of nation-

alities.

Sergei Shakhrai trained as a lawyer at Rostov

State University and attained the rank of candidate

of juridical sciences from Moscow State University

(MGU) in 1982. He then taught law at MGU un-

til 1990. Shakhrai was a Party member from 1988

to August 1991.

In 1990, Shakhrai was elected to the new

RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies, where he

quickly became chair of the RSFSR Supreme Soviet

Committee for Legislation. He simultaneously

served Boris Yeltsin as a counselor for legal and na-

tionalities affairs. In 1992 he was named a mem-

ber of the Russian Federation Security Council and

deputy chair responsible for nationality issues.

During the November–December 1992 ethnic un-

rest in North Ossetia and Ingushetia, Shakhrai

served as head of the temporary regional adminis-

tration. A Terek Cossack, he also chaired the Rus-

sian parliamentary committee on the rehabilitation

of the Cossacks. In November 1992, Shakhrai was

appointed a deputy prime minister.

In legal matters, Shakhrai argued Yeltsin’s case

in the 1992 Constitutional Court hearings on the

legality of the president’s banning of the CPSU, a

decree written by Shakhrai himself. He also served

as Yeltsin’s representative to the 1993 Duma com-

mission drafting a new Russian constitution and

negotiated many of the subsequent federal power-

sharing treaties. Shakhrai became leader of the

Party of Russian Unity and Accord in October

1993, running on their ticket in the December 1993

Duma election. However, he resigned from the

party when the party joined the Our Home is Rus-

sia movement in August 1995.

Shakhrai was transferred from deputy prime

minister to minister of nationalities and regional

policy in January 1994. This move was soon over-

turned; by April he was reappointed deputy prime

minister and in May removed as minister of na-

tionalities. However, he continued to influence the

decisions of his replacement, Nikolai Yegorov.

Shakhrai’s work in law and nationality affairs

combined in the issue of Chechnya. Despite Chechen

president Dzhokar Dudayev’s assertions otherwise,

Shakhrai insisted that Chechnya remained an inte-

gral part of the Russian Federation. When Dudayev

refused to ratify the new constitution, despite

Shakhrai’s repeated attempts at negotiation, he

SHAKHRAI, SERGEI MIKHAILOVICH

1376

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

provided the legal pretext for an invasion. Shakhrai

and minister of defense Pavel Grachev convinced

Yeltsin that an attack on Chechnya would be quick

and painless; ultimately, the attack was launched

in December 1994. Shakhrai’s prediction proved

false, however, as the first Russo-Chechen war

lasted until August 1996.

Yeltsin summarily fired Shakhrai in June 1998,

when the lawyer questioned the constitutionality

of a possible third term as president for Yeltsin.

However, Shakhrai was not unemployed for long.

In October, prime minister Yevgeny Primakov ap-

pointed Shakhrai as his own legal advisor. Shakhrai

also won a Duma seat for Perm oblast during the

1999 election. As of 2003 he was a member of the

influential Russian Foreign and Defense Policy

Council and was teaching at Moscow State Insti-

tute for International Relations (MGIMO).

See also: AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH; PARTY OF RUSSIAN UNITY

AND ACCORD

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dunlop, John B. (1998). Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots

of a Separatist Conflict. New York: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Lieven, Anatol. (1998). Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian

Power. New Haven: Yale University Press.

A

NN

E. R

OBERTSON

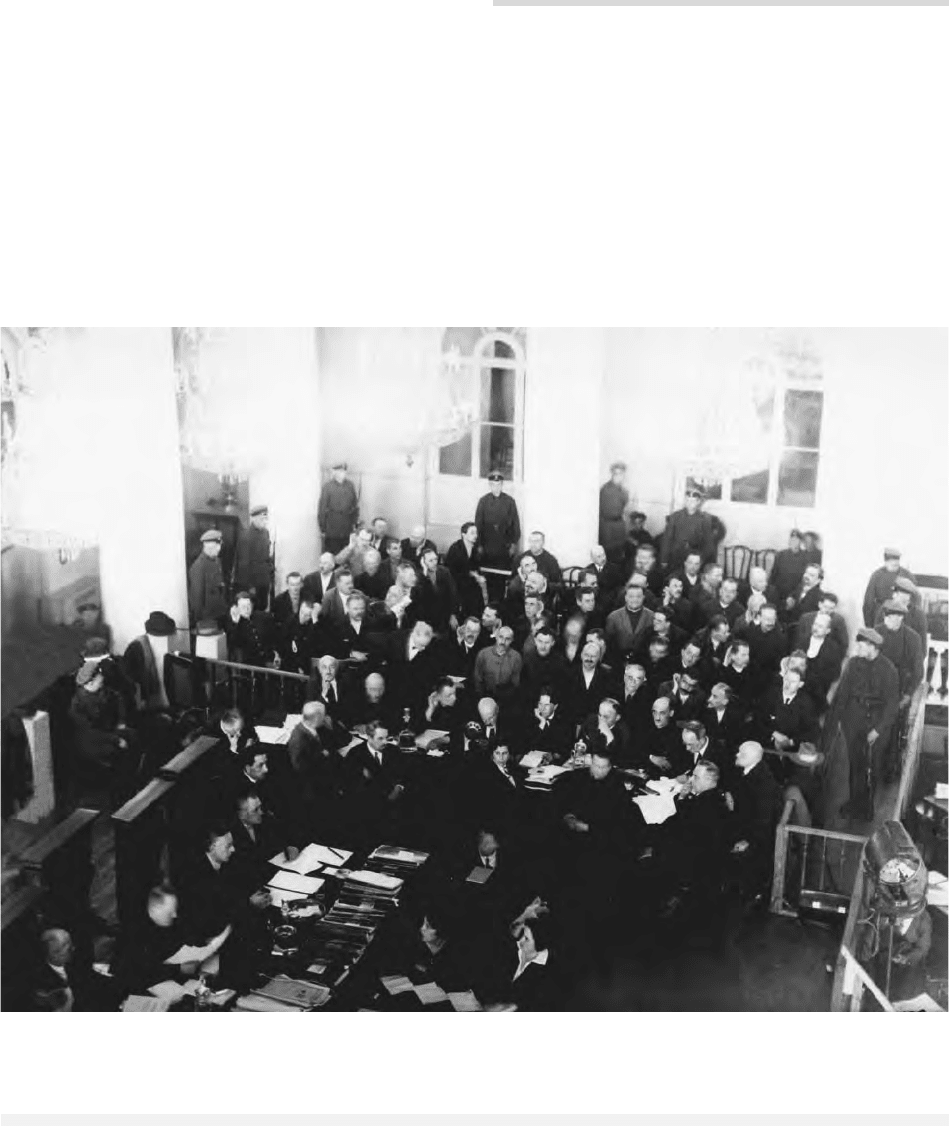

SHAKHTY TRIAL

This famous trial based on fabricated charges was

used by Stalin to start a three-year attack on the

technical intelligentsia of the USSR and to discredit

moderates within the political leadership. Fifty-

three mining engineers and technicians, including

some top officials and three German engineers,

were accused of acts of sabotage and treason dat-

ing back to the 1920s and taking part in a con-

spiracy directed from abroad (involving French

SHAKHTY TRIAL

1377

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Courtroom scene from the Shakhty sabotage trial in 1928. © TASS/SOVFOTO

finance and Polish counterespionage). The story of

conspiracy was fabricated by the Unified State

Political Administration (OGPU) officials in the

North Caucasus mining district known as the

Donbass and focused on such acts as wasting cap-

ital, lowering the quality of production, raising its

costs, mistreating workers, and other forms of

“wrecking.”

Held in a large auditorium at the House of

Trade-Unions in Moscow, this six-week-long trial

was arranged for maximum publicity, with movie

cameras, a hundred journalists in attendance, and

a different public audience each day. The presiding

judge over the specially organized judicial presence

was Andrei Vyshinsky, famous for his appearance

as prosecutor at the major show trials of the 1930s;

the prosecutor at the Shakhty trial was the Bol-

shevik jurist Nikolai Krylenko. For evidence, the

prosecution relied on confessions of the accused,

but twenty-three of the defendants proclaimed their

innocence, and a few others retracted their confes-

sions at trial. As a political show trial Shakhty was

imperfect. Still, all but four of the accused were

convicted, and five of them executed.

In the wake of the Shakhty trial, non-Marxist

engineers and technicians were placed on the de-

fensive and many fell victim to persecution. “Spe-

cialist baiting” ranged from verbal harassment to

firing from jobs, not to speak of arrests and con-

victions in later trials, including the well-known

“Industrial Party” case. By 1931, when Stalin called

a halt to the anti-specialist campaign, Soviet engi-

neers had been tamed and any nascent threat of

technocracy defeated.

On the political level, the Shakhty trial served

Stalin as a vehicle for radicalizing economic policy

and sending a message of warning to moderates in

the leadership (such as Alexei Rykov and Nikolai

Bukharin). If nothing else, the persecution of the

“bourgeois specialists” weakened one of the con-

stituencies that supported a relatively cautious and

moderate approach to industrialization. With hind-

sight it is clear that the Shakhty trial, along with

the renewal of forced grain procurements, signaled

the coming end of the class-conciliatory New Eco-

nomic Policy and the start of a new period of class

war that would culminate in the forced collec-

tivization from 1929 to 1933. An important man-

ifestation of the new class war was the Cultural

Revolution from 1928 to 1931, in which young

communists in many fields of art, science, and pro-

fessional life were encouraged to attack and sup-

plant their non-Marxist senior colleagues.

See also: SHOW TRIALS; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bailes, Kendall. (1978). Technology and Society under Lenin

and Stalin: Origins of the Soviet Technical Intelligentsia,

1917–1941. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1978). “Cultural Revolution as Class

War.” In Cultural Revolution in Russia, 1928–1931,

ed. Sheila Fitzpatrick. Bloomington: Indiana Univer-

sity Press.

Kuromiya, Hiroaki. (1997). “The Shakhty Affair.” South

East European Monitor 4(2):41–64.

P

ETER

H. S

OLOMON

J

R

.

SHAMIL

(1797–1871), the most famous and successful anti-

Russian Islamic resistance leader during the nine-

teenth century; lionized by Chechen and Dagestani

nationalists and co-opted by Russian literature and

the public consciousness as a sign of tsarist impe-

rial expansion and the Russian mission in Asia.

Born in Gimri, modern Dagestan, Shamil demon-

strated an early skill with weapons and horses. He

entered a madrassah where he learned grammar,

logic, rhetoric, and Arabic. There he joined the

Murids, of the Naqshbandi-Khalidi Sufi order, in

1830. Following the transfer of Dagestan from Per-

sia to the Russian Empire, Murids initiated a jihad

against Russia under the leadership of Shamil’s men-

tor, the first imam of Dagestan, Ghazi Muhammed.

After his death and the brief leadership of Hamza

Bek, Shamil became the third imam of Dagestan and

declared it an independent state in 1834. His personal

charisma, political acumen, state building, and mil-

itary ability as well as his blending of an egalitarian

interpretation of Shari’a (Islamic Law) with procla-

mations of jihad against the Russian advance made

him a popular political and religious leader (even

among the non-Muslims of the North Caucasus).

For twenty-five years (1834–1859), Shamil led

raids on Russian positions in the Caucasus. He

reached the peak of prestige in 1845 devastating

the advance of Mikhail Vorontsov, who organized

an army to complete the final conquest of the Cau-

casus. In these years of struggle, Shamil unified the

disparate communities of the North Caucasus, built

a state, organized a regular army, and completed

the Islamicization of Dagestan and Chechnya. In

SHAMIL

1378

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

1857, the Russian Empire took a more aggressive

stance; Generals Alexander Baryatinsky and Niko-

lai Evdokimov overwhelmed the weaker and ex-

hausted forces of Shamil. By April 1859 his fortress

at Vedeno fell and Shamil retreated to Mount Gu-

nib. On September 6, 1859, Shamil surrendered to

the Russians and the resistance movement never re-

covered. He was taken to St. Petersburg for an au-

dience with Tsar Alexander II, paraded around

Russia as a hero and menace, and then exiled to

Kaluga. In March 1871 he died and was buried in

Medina.

Drawing from the rich literary tradition of

Alexander Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov, and Alexan-

der Bestuzhev-Marlinsky, Shamil emerged as a Cau-

casian hero of Russian Romanticism and a symbol

of Russian expansion and its civilizing mission.

Shamil was an international celebrity; his exploits

serialized in numerous languages. Soviet historians

initially lauded Shamil as a hero of a national liber-

ation movement against tsarist imperialism; this be-

came problematic when his name was linked with

anti-Russian and anti-Bolshevik opposition. Thus,

Shamil was depicted by Soviet historians during the

second half of the twentieth century as personally

progressive while his movement was corrupted by

anti-popular and religious elements.

See also: CAUCASUS; ISLAM; NATIONALISM IN THE TSARIST

PERIOD

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gammer, Moshe. (1994). Muslim Resistance to the Tsar:

Shamil and the Conquest of Chechnia and Daghestan.

London: Frank Cass.

M

ICHAEL

R

OULAND

SHAPOSHNIKOV, BORIS MIKHAILOVICH

(1882–1945), marshal (1940), general staff officer,

military theorist, and chief of the Red Army Gen-

eral Staff.

Originally a career officer in tsarist service, Sha-

poshnikov graduated in 1910 from the Nicholas

Academy of the General Staff, then served in

Turkestan, where he possibly contracted malaria,

and in the Warsaw Military District. He attained

regimental command during World War I, joined

the Red Army in 1918, and occupied high staff po-

sitions during the Russian civil war, usually as

planner or intelligence officer. He next served on

the Worker’s and Peasants’ Red Army (RKKA) staff,

then from 1925 to 1928 commanded the Leningrad

and Moscow military districts. From 1928 to 1931

he was RKKA chief of staff, followed by a tour as

commander of the Volga Military District. From

1933 to 1935 he headed the Frunze Military Acad-

emy, after which he commanded the Leningrad

Military District. From 1937 to 1940 he served as

second chief of the newly created Red Army Gen-

eral Staff, followed by appointment after the Win-

ter War (1939–1940) as deputy Defense Commissar.

At the end of July 1941, despite ill health, he re-

placed Georgy Zhukov to serve as chief of the Gen-

eral Staff until May 1942. While recovering from

either nervous exhaustion or malaria, he reverted

to assignment as deputy defense commissar, fol-

lowed in 1943–1945 by tenure as chief of the Acad-

emy of the General Staff.

An officer of intellect and experience, Shaposh-

nikov left his mark on nearly every important mil-

itary organizational and doctrinal innovation of the

1920s and 1930s. His most important scholarly

work was Brain of the Army (published in three vol-

umes, 1927–1929), in which he studied the Aus-

trian model of Conrad von Hoetzendorf and the

tsarist experience in 1914 to argue for the creation

of a modern Soviet general staff headed by an “in-

tegrated great captain.” The consummate general

staff officer, Shaposhnikov was one of the few of-

ficers who enjoyed Josef Stalin’s open respect, and

nearly every subsequent chief of the Red Army/So-

viet General Staff considered himself Shaposh-

nikov’s disciple.

See also: MILITARY, SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Erickson, John. (1962). The Soviet High Command. New

York: St. Martin’s Press.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

SHATALIN, STANISLAV SERGEYEVICH

(1934–1997), Soviet economist; advocate of decen-

tralization and market reforms.

Born in a family of upper-level functionaries of

the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),

Stanislav Shatalin graduated from the economics

department of the Moscow State University and

SHATALIN, STANISLAV SERGEYEVICH

1379

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

entered academia in the era of the Thaw. In 1965

he joined an influential school of economists at the

Central Economics and Mathematics Institute

(TsEMI) who were developing and advocating the

System of Optimal Functioning for the Economy

(SOFE) based on mathematical modeling. He shared

the highest-ranking State Award, served as deputy

director of the All-Union Institute for Systems

Studies and director of the Institute for Economic

Forecasting that had separated from TsEMI, and

became full member of the Academy of Sciences in

1987. In 1989 and 1990, he emerged as a key ad-

visor to Mikhail Gorbachev and a rival to the gov-

ernment economic team of Leonid Abalkin, and

was appointed to the Presidential Council. He coau-

thored the Five-Hundred-Day Plan, a reform pro-

gram that was eventually declined by Gorbachev,

partly because of its emphasis on the decentral-

ization of the Union, but was widely acclaimed in

the West. This program contained, albeit in a dif-

ferent sequence, the essential elements of the sub-

sequent reforms of the 1990s (although some

argue that the five hundred days was more grad-

ual and mindful of the social consequences of dras-

tic deregulation).

After briefly taking part in liberal politics,

Shatalin established and chaired the Reforma Foun-

dation. His twilight years were overshadowed by

the Audit Chamber’s inquiry into a mutually prof-

itable relationship between a bank affiliated with

his foundation and government managers of social

security funds.

See also: FIVE-HUNDRED-DAY PLAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hough, Jerry F. (1997). Democratization and Revolution

in the USSR, 1985–1991. Washington, DC: Brook-

ings Institution Press.

Shatalin, S.; Petrakov, N.; Aleksashenko, S.; Yavlinsky,

G.; and Fedorov, B. (1991). 500 Days: Transition to

the Market. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

D

MITRI

G

LINSKI

SHCHARANSKY, ANATOLY

NIKOLAYEVICH

(b. 1948), prominent Jewish dissident.

Anatoly Shcharansky was arrested on March

15, 1977, after being denied permission to emi-

grate from the Soviet Union. A twenty-nine-year-

old computer expert at the time, Shcharansky had

been a leading figure in the Helsinki Group, the

oldest human rights organization in the Soviet

Union, founded by Yuri F. Orlov on May 12,

1976, for the purpose of upholding the USSR’s

responsibility to implement the Helsinki commit-

ments. The Helsinki Agreement had been promul-

gated a year earlier (August 1975), its text

published in full in both Pravda and Izvestia. The

formation of the Moscow Helsinki Group sparked

the creation of several human rights organizations

throughout the Soviet Union. Shcharansky was a

founding member of the group, along with Ye-

lena Bonner (Andrei Sakharov’s wife), Anatoly

Marchenko, Ludmilla M. Alexeyeva, and others.

In the first three years of the group’s work, nearly

all of its members were arrested or sentenced to

psychiatric hospitalization as a way to repress

their activities.

Shcharansky’s arrest was part of a Soviet cam-

paign against dissidents begun in February 1977.

Others were arrested before him: Alexander Gins-

burg (February 4), Ukrainian dissidents Mikola

Rudenko and Olexy Tikhy (February 7), and Yuri

Orlov (February 10). In June 1977, Shcharansky

was charged with treason, specifically with ac-

cepting CIA funds to create dissension in the Soviet

Union. After a perfunctory trial, he was sentenced

to fourteen years in prison. He was finally released

in February 1986, when he and four other prison-

ers were exchanged for four Soviet spies who had

been held in the West. Shcharansky finally emi-

grated to Israel, where he first changed his name

to Natan Shcharan before settling on Natan Shcha-

ransky. He is active in Israeli politics.

See also: JEWS; REFUSENIKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gilbert, Martin. (1986). Shcharansky, Hero of Our Time.

New York: Viking.

Goldberg, Paul. (1988). The Final Act: The Dramatic, Re-

vealing Story of the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group.

New York: Morrow.

Shcharansky, Anatoly; Bonner, Elena; and Alekseeva, Li-

udmilla. (1986). The Tenth Year of The Watch. New

York: Ellsworth.

Shcharansky, Anatoly, and Hoffman, Stefani. (1998).

Fear No Evil: The Classic Memoir of One Man’s Triumph

Over a Police State. New York: Public Affairs.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

SHCHARANSKY, ANATOLY NIKOLAYEVICH

1380

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

SHCHEPKIN, MIKHAIL SEMEONOVICH

(1788–1863), an actor from the serf estate who

revolutionized acting styles with his realistic por-

trayals.

Born in Ukraine into a family owned by Count

G. S. Volkenshtein, the young Mikhail Shchepkin

began performing in the private theater maintained

on the estate. Indeed, many nobles used their serfs’

skills for entertainment, and Shchepkin represented

an important source of talent for the professional

stage. Especially gifted, by 1800 he was allowed to

participate in amateur productions in nearby

Kursk. Though still a serf, he joined several provin-

cial touring companies as he rose to stardom. Fi-

nally, in 1822, one of his noble fans, Prince N. G.

Repin, persuaded his owner to free him. Later that

year Shchepkin made his debut in Moscow, and in

1824 he began his legendary rule at the imperial

Maly Theater, where he dominated in comedy and

drama, including William Shakespeare’s corpus, for

the next forty years. From his theatrical base in

Moscow, he also toured the provinces and appeared

on St. Petersburg’s imperial stage.

Shchepkin’s artistic significance lies in his in-

fluence over the transformation of acting styles,

developing multi-dimensional characters instead of

simulating the single stereotype. His breakthrough

came in 1830, in his characterization of the fatu-

ous Muscovite nobleman Famusov in Alexander

Griboyedov’s Woe from Wit. Six years later, Shchep-

kin’s rendition of Khlestakov, the petty bureaucrat

mistakenly identified by corrupt provincial officials

as one of the tsar’s investigators in Nikolai Gogol’s

The Inspector General, assured the move toward re-

alism.

His great talent, and popularity on stage, gave

him access to Russia’s highest literary circles, where

he helped novelist Ivan Turgenev write for the

stage. Ironically, though, he surrendered his place

at center stage when he refused to modify his style

to accommodate the next level of realism, plays

written in colloquialisms by Russia’s historically

most popular playwright Alexander Ostrovsky

from the 1860s.

See also: THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Senelick, Laurence. (1984). Serf Actor: The Life and Art of

Mikhail Shchepkin. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

L

OUISE

M

C

R

EYNOLDS

SHCHERBATOV, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH

(1733–1790), historian, publicist, and government

servitor.

Mikhail Mikhailovich Shcherbatov was a scion

of one of Russia’s oldest families of the nobility. His

father-in-law, Prince Ivan Shcherbatov (1696–1761),

was Russian minister to the court of St. James from

1739 to 1742, and from 1743 to1746. Upon re-

tirement from military service in 1762 following

Peter III’s Manifesto on the Freedom of the Nobil-

ity, Mikhail Shcherbatov went on to serve as a

deputy to Catherine II’s Legislative Commission

(1766–1767), and then as Russia’s official histori-

ographer, beginning in 1768.

Shcherbatov is perhaps best known for his pub-

lication On the Corruption of Morals in Russia

(O Povrezhdenii Nravov v Rossii), in which he criti-

cizes Peter the Great’s introduction of the Table of

Ranks (1722). He argued that the rank system re-

duced the prestige of the old nobility and allowed

the rise of a mediocre and materialistic class of servi-

tors. “By the regulations of the military service,

which Peter the Great had newly introduced,” he

wrote, “the peasants began with their masters at the

same stage as soldiers of the rank and file: It was

not uncommon for the peasants, by the law of se-

niority, to reach the grade of officer long before their

masters, whom, as their inferiors, they frequently

beat with sticks. Noble families were so scattered in

the service that often one did not come again in con-

tact with his relatives during his whole lifetime.”

Shcherbatov believed in the innate inequality of hu-

man beings and genetic superiority of the noble aris-

tocracy. He lamented the decline of the pre-Petrine

nobility’s influence during the eighteenth century,

because he did not believe one could achieve the ge-

netic superiority of the latter by meritorious service

alone. While he did advocate a constitutional form

of government, he urged that Russia be ruled by a

hereditary monarch, who would be constrained only

by a constitution and checked only by a Senate com-

posed of the old nobility with extensive financial, ju-

dicial, and executive powers.

See also: KULTURNOST; TABLE OF RANKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cross, A. G., and Smith, G. S., eds. (1994). Literature,

Lives, and Legality in Catherine’s Russia. Cotgrave,

Nottingham, UK: Astra Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

SHCHERBATOV, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH

1381

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

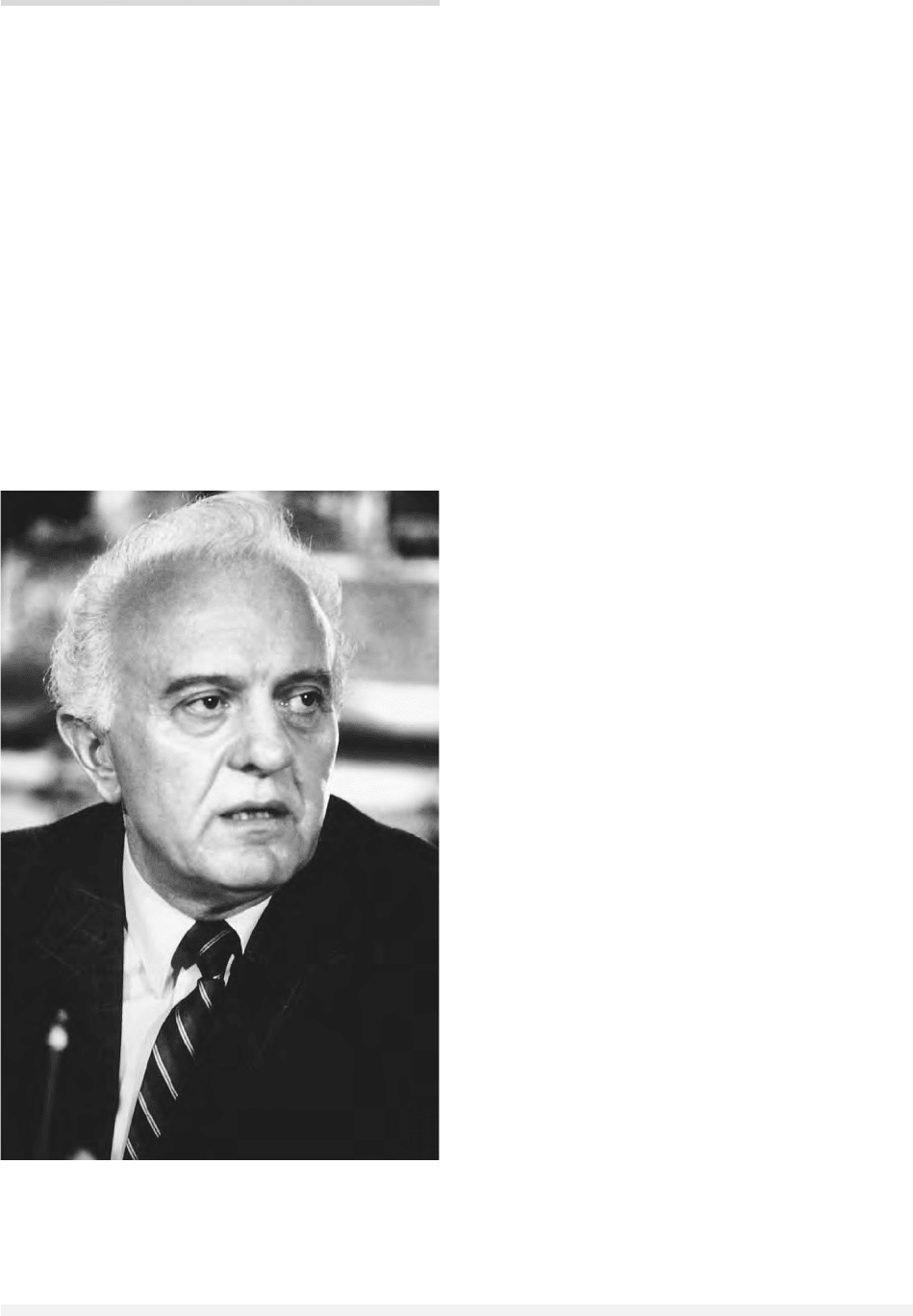

SHEVARDNADZE, EDUARD

AMVROSIEVICH

(b. 1928), foreign minister coincident with the dis-

solution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold

War.

Eduard Shevardhadze was minister of internal

affairs of the Georgian Republic from 1965 to 1972,

first secretary of the republic from 1972 to 1985,

foreign minister of the Soviet Union from 1985 to

1990 and again in 1991, and president of the Re-

public of Georgia from 1992 onward.

Until 1985, Eduard Shevardnadze’s career had

been entirely within the Soviet republic of Georgia.

The character traits he brought with him from

Georgia would serve him well during his years as

foreign minister. He was a man of considerable vi-

sion, with a strong sense of purpose. He was also

a superb politician—opportunistic, flexible, prag-

matic, and ruthless. He was a natural actor, as

every great politician must be, and he was a man

of action, a problem-solver impatient with obsta-

cles, and a brutal political infighter. Perhaps most

important, he was a Georgian with cosmopolitan

leanings, not a Russian who distrusted the West.

Shevardnadze used the available instruments of

power to advance his career and further his policy

objectives in Georgia at the outset of his career. He

repressed dissidents and removed real and potential

opponents. An outstanding Soviet apparatchik, he

acted the role of sycophant to the leaders of the So-

viet Union, extolling the virtues of those in a po-

sition to help him. But he brought to the Foreign

Ministry in Moscow a commitment to radical

change, a willingness to implement reform in an

unorthodox manner, and the political skills and

strength to accomplish his goals.

When Shevardnadze was appointed foreign

minister of the Soviet Union in 1985, it was widely

assumed that he would be little more than a

mouthpiece for Mikhail Gorbachev, who would

conduct his own foreign policy. In turning to a

regional party leader with no foreign-policy back-

ground, however, Gorbachev was relying on per-

sonal instinct and political acumen. As party leader

in Georgia during the 1970s and early 1980s, She-

vardnadze battled corruption and introduced the

most liberal political and economic reforms of any

Soviet regional leader. Gorbachev’s long association

with Shevardnadze was rooted in shared frustra-

tion with the inefficiencies and corruption of the

communist system, and he believed that his friend

had the understanding and political skills necessary

to formulate and implement a new foreign policy.

Shevardnadze played a critical role in concep-

tualizing and implementing the Soviet Union’s dra-

matic about-face during the 1980s. Considered the

moral force behind “new political thinking” in the

former Soviet Union, Shevardnadze was the point

man in the struggle to undermine the forces of

inertia at home and to end Moscow’s isolation

abroad. Two U.S. secretaries of state, George Shultz

and James Baker, have credited him with convinc-

ing them that Moscow was committed to serious

negotiations with the United States. Each became a

proponent of reconciliation in administrations that

were intensely anti-Soviet; each concluded that the

history of Soviet-U.S. relations and the end of the

Cold War would have been far different had it not

been for Shevardnadze.

SHEVARDNADZE, EDUARD AMVROSIEVICH

1382

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

As foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze implemented

Gorbachev’s “new thinking” in international relations. A

RCHIVE

P

HOTOS

, I

NC

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.