Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Hudgins, Sharon W. (2003). The Other Side of Russia: A

Slice of Life in Siberia and the Russian Far East. Col-

lege Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Lincoln, W. Bruce. (1994). The Conquest of a Continent:

Siberia and the Russians. New York: Random House.

Marx, Steven G. (1991). Road to Power. Ithaca, NY: Cor-

nell University Press..

Mote, Victor L. (1998). Siberia Worlds Apart. Boulder, CO:

Westview Press.

Thubron, Colin. (1999). In Siberia. New York: Harper

Collins.

Treadgold, Donald W. (1957). The Great Siberian Migra-

tion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tupper, Harmon. (1965). To the Great Ocean. Boston, MA:

Little, Brown.

V

ICTOR

L. M

OTE

SIGNPOSTS See VEKHI.

SIKORSKY, IGOR IVANOVICH

(1889–1972), scientist, engineer, pilot, and entre-

preneur.

Igor Sikorsky designed the world’s first four-

engined airplane in 1913 (precursor to the most

successful bomber of World War I) and the world’s

first true production helicopter. His single-rotor de-

sign, a major breakthrough in helicopter technol-

ogy, remains the dominant configuration in the

early twenty-first century. The winged-S emblem

still signifies the world’s most advanced rotorcraft.

Born in Kiev, Russia, Sikorsky was the youngest

of five children. His father, a medical doctor and

psychologist, inspired him to explore and learn. He

developed a keen interest in mechanics and astron-

omy. While still a schoolboy he built several model

aircraft and helicopters, as well as bombs. After

completing formal education in Russia and France,

Sikorsky attracted international recognition in

1913 at the age of twenty-four when he designed

and flew the first multimotor airplane. In 1918,

Sikorsky decided to flee his native country: “What

were called the ideals and principles of the Marxist

revolution were not acceptable to me.” He left Pet-

rograd (St. Petersburg) by rail for Murmansk and

from there boarded a steamer for England. Having

lost all his savings, he arrived in England with only

a few hundred English pounds.

He settled in the United States in 1919, even-

tually founding the Sikorsky Aero Engineering Cor-

poration, the forerunner of the Sikorsky Division

of United Technologies. In the early twenty-first

century the corporation manufactures helicopters

for sale around the world. Continually designing

aircraft, Sikorsky received many other patents, in-

cluding patents for helicopter control and stability

systems. He grasped the humanitarian advantages

of helicopters over airplanes. “If a man is in need

of rescue,” he said, “an airplane can come in and

throw flowers on him, and that’s just about all . . .

but a direct-lift aircraft could come in and save his

life.” In the 1930s, Sikorsky designed and manu-

factured a series of large passenger-carrying flying

boats that pioneered the transoceanic commercial

air routes in the Caribbean and Pacific.

See also: AVIATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cochrane, Dorothy. (1989). The Aviation Careers of Igor

Sikorsky. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Hunt, William E. (1998). ’Heelicopter’: Pioneering with Igor

Sikorsky: Based on a Personal Account. Shrewsbury,

UK: Airlife Pub.

Sikorsky, Igor Ivan. (1941). The Story of the Winged-S:

With New Material on the Latest Development of the

Helicopter; an Autobiography by Igor I. Sikorsky; with

Many Illustrations from the Author’s Collection of Pho-

tographs. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co.

Spenser, Jay P. (1998). Whirlybirds: A History of the U.S.

Helicopter Pioneers. Seattle: University of Washing-

ton Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

SILVER AGE

From the late nineteenth century until World War

I, the Russian visual, literary, and performing arts

achieved such creative brilliance that observers—

not least the critic and poet Sergei Makovsky (1878–

1962)—described the period as a “Silver Age.” Many

individuals, institutions, and ideas contributed to

this renaissance: Sergei Diaghilev (1872–1929) and

the St. Petersburg World of Art; painters Lev Bakst

(1866–1924), Viktor Borisov-Musatov (1870–1905),

and Mikhail Vrubel (1856–1910); writers Kon-

stantin Balmont (1867–1942), Andrei Bely (pseu-

donym of Boris Bugayev, 1880–1934), Alexander

Blok (1880–1921), Valery Bryusov (1873–1924),

SILVER AGE

1393

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and Vyacheslav Ivanov (1866–1949); the Ballets

Russes; the new theaters with their repertoires of Ib-

sen and Maeterlinck; and the architecture of the style

moderne—all shared the eschatological mood of the

fin de siècle heightened by the disasters of the Russo-

Japanese War and the 1905 Revolution.

There was a climactic and ominous sense in the

culture of the Russian Silver Age, for its poetry

spoke of femmes fatales and fleshly indulgence, and

its painting depicted twilights and satanic beasts.

Perhaps even more than the Western European

Symbolists, the Russian poets, painters, and philoso-

phers made every effort to escape the present by

looking back to an Arcadian landscape of pristine

myth and fable or by looking forwards to a utopian

synthesis of art, religion, and organic life. For Rus-

sia’s children of the fin de siècle, Symbolism became

much more than a mere esthetic tendency; rather,

it represented an entire worldview and a way of

life that informed the intense visions of Bely, Blok,

and Vrubel; the religious explorations of the priest,

mathematician, and art historian Pavel Florensky

(1882–1937); the decorative flourishes of Bakst and

Alexandre Benois (1870–1960); and even the ab-

stract systems of Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944)

and Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935). Bely’s novel

Petersburg, Blok’s poem “The Stranger,” Vrubel’s

images of torment and distress, and the galvaniz-

ing music of Alexander Skryabin (1872–1915) all

express the nervous tension and febrile energy of

the Russian Silver Age.

Its most original artist was Vrubel, whose fer-

tile imagination produced disconcerting pictures

such as Demon Downcast (1902, Tretiakov Gallery,

Moscow; hereafter “TG”). While the definitions

“Art Nouveau” and “Neo-Nationalism” come to

mind in the context of his work, Vrubel approached

the act of painting as a constant process of exper-

imentation, returning to his major canvases again

and again, erasing, repainting, altering. His releas-

ing of the energy of the ornament and his intense

elaboration of the surface even prompted future

critics to consider his painting in the context of Cu-

bism, for his broken brushwork strangely antici-

pated the visual dislocation of the late 1900s.

Even so, a characteristic of the Russian Sym-

bolists was more recreative than experimental in

nature, characterized by the aspiration to restore

an esthetic unity to the disciplines through the re-

discovery of a common philosophical and formal

denominator. To this end, they often explored more

than one medium simultaneously. In keeping with

this interdisciplinarity, the principal artistic and in-

tellectual society with which many of them were

associated was called the “World of Art.” Hostile

toward both the Academy and nineteenth century

Realism, the World of Art owed its singular vision,

practical organization, and public effect to Di-

aghilev, who in 1898 launched the famous maga-

zine of the same name (Mir iskusstva, 1898–1904),

sponsored a cycle of important national and inter-

national exhibitions, and propagated Russian art

and music successfully in the West. The World of

Art artists and writers never issued a written man-

ifesto, but their attention to artistic craft, cult of

retrospective beauty, and assumed distance from

the ills of sociopolitical reality indicated a firm be-

lief in “art for art’s sake” and a sense of measured

grace, which they identified with the haunting

beauty of St. Petersburg.

The fame of several World of Art painters, par-

ticularly Bakst and Benois, rests primarily on their

set and costume designs for Diaghilev’s Ballets

Russes (1909–1929), which, with its emphasis on

artistic synthesis, evocation of archaic or exotic cul-

tures, and invention of a new choreographic, mu-

sical, and visual communication, can be regarded

as an extension of the Symbolist platform. The ease

with which the World of Art transferred pictorial

ideas from studio to stage (for instance, produc-

tions such as Cléopatre of 1909, designed by Bakst,

Petrouchka of 1911, designed by Benois, and Le Sacre

du Printemps of 1913, designed by Nicholas Roerich

[1874–1947]) was indicative of a general tendency

toward “theatralization” evident in the culture of

the Silver Age. Here was an exaggerated sensibil-

ity, but also a conviction that artistic movement

was the common denominator of all “great” works

of art. This could take the form of physical move-

ment, such as dance, rhythm, and gesture, or of

abstract equivalents, such as poetical meter and

music, which, for all the Symbolists, was the high-

est form of expression, the most intense and yet

the most minimal material.

A bastion of the Symbolist cause, the World of

Art encompassed a multiplicity of artistic phe-

nomena: the consumptive imagery of Aubrey

Beardsley and the stylizations of the early Kandin-

sky; the Art Nouveau designs of Charles Rennie

Mackintosh and Elena Polenova (1850–98); and the

Decadent verse of Zinaida Gippius (1869–1945) and

Dmitry Merezhkovsky (1866–1941). The World of

Art fulfilled the practical function of propagating

Russian art at home and abroad and of granting

the Russian public access to the work of modern

SILVER AGE

1394

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Western artists through exhibitions and publica-

tions.

The Russian Silver Age was not confined by

strict geographical or social boundaries, for it

also flowered—and perhaps more luxuriously—in

Moscow and the provinces. Even Saratov, a small

town to the south of Moscow, became a major

center of Symbolist enquiry, thanks to the activi-

ties of the painter Borisov-Musatov, who, together

with Vrubel, exerted a profound and permanent in-

fluence on the evolution of Russian Modernism.

Impressed by Puvis de Chavannes and the Nabis

during his residence in Paris, Borisov-Musatov in-

corporated their monumentalism and subdued

palette into his elusive depictions of such wraith-

like women as in Gobelin (1901, TG) and Reservoir

(1902, TG). Evoking a gentler and more tranquil

age, Borisov-Musatov shared the Symbolists’ de-

sire to escape from their troubled time, and one of

SILVER AGE

1395

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

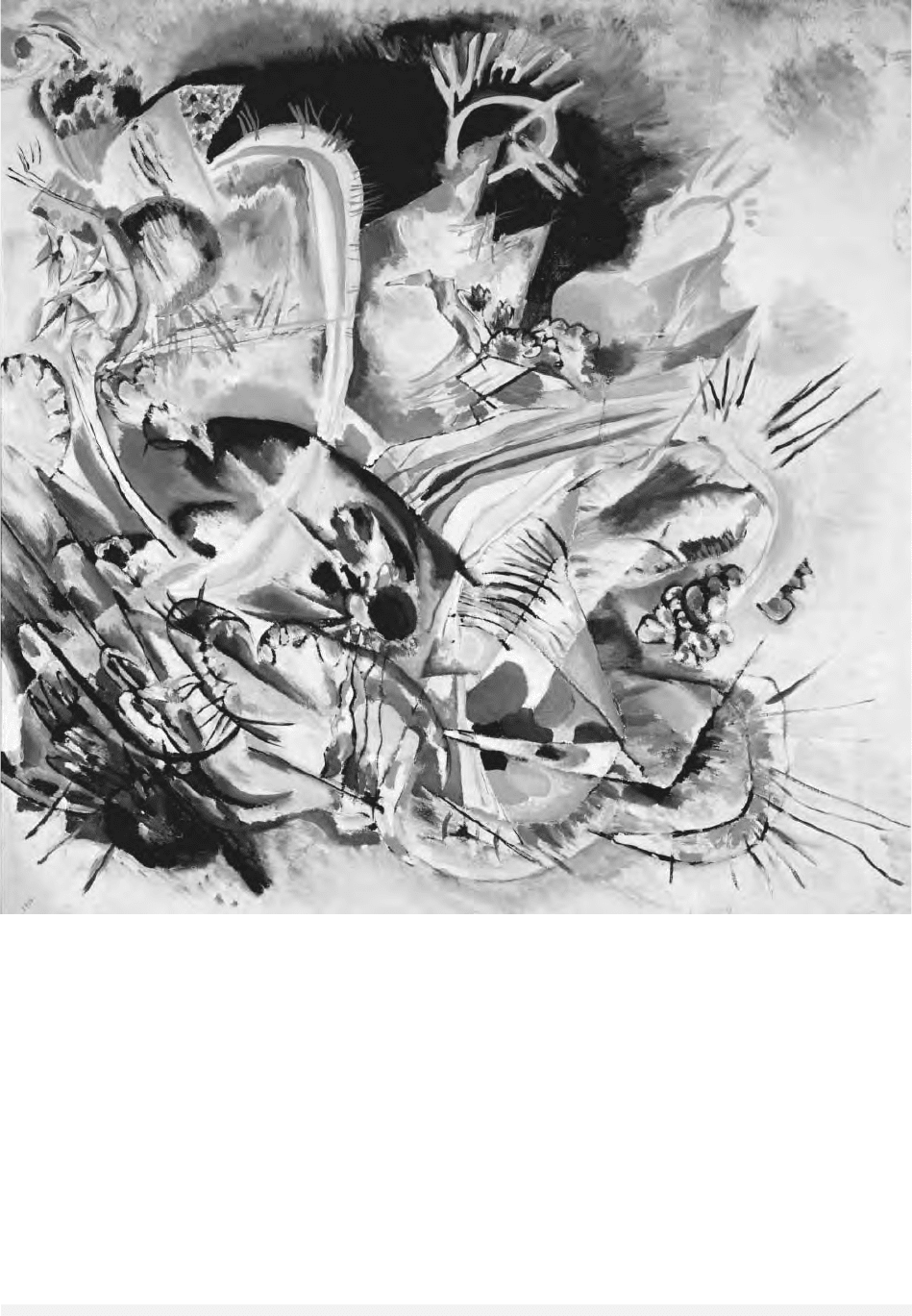

Improvisation V. by Vasily Kandinsky. The abstract works by Kandinsky can be traced to the symbolism of the Silver Age. © G

EOFFREY

C

LEMENTS

/CORBIS

his central motifs, the “Eternal Feminine,” aligned

him with poets such as Bely and Blok.

Borisov-Musatov also established a short-lived

but crucial school of painters, for he was the direct

instigator of the “Blue Rose,” a movement which

can be considered the real beginning of the avant-

garde in Russian art. Apologists of Bely’s esthetics

and Blok’s poetry, the Blue Rose artists, especially

their leader, Pavel Kuznetsov (1878–1968), used a

particular repertoire of symbols (blue-green foliage,

fountains, and vestal maidens) in order to evoke

the global orchestra that they heeded beyond the

world of appearances. Concerned with the oblique

and the intangible, they dematerialized nature and

thereby heralded the radical concept of the picture

as a self-sufficient, abstract unit. The Symbolist

journals, Vesy (Scales,1904–1909 [last issues ap-

peared only in 1910]), Iskusstvo (Art, 1905) and

Zolotoe runo (Golden Fleece, 1906–1909 [last issues

appeared only in 1910]), did much to promote their

ideas and imagery.

Reference to the Symbolist heritage helps to ex-

plain a number of subsequent developments in

Russian art, especially the abstract investigations

of Kandinsky and Malevich, for in many respects

they expanded ideas supported by the Russian in-

telligentsia of the Silver Age. As Kandinsky ex-

plained in his major tract On the Spiritual in Art,

the intuitive and the occult, not science, were the

path to true illumination. Like the Symbolists,

Kandinsky also felt that music could undermine the

cult of objects and that the inner sound could be

apprehended at moments of supersensitory or de-

viant perception. Similarly, Kandinsky was fasci-

nated with the synthetic aspect of the esthetic

experience and aspired to reintegrate the individual

arts into a Gesamtkunstwerk. Reasons for this ap-

proach differed from person to person, although

Benois, Diaghilev, and V. Ivanov agreed that Wag-

ner was to be admired for the way in which he had

combined narrative, musical, and visual forces in

the operatic drama so as to produce an expressive

whole. For Kandinsky, Wagner was a source of vis-

ual inspiration and, similarly, Skryabin’s efforts to

draw distinct parallels between the seven colors of

the spectrum and the seven notes of the diatonic

scale prompted him to investigate the possibility of

a total art.

Even as he was writing On the Spiritual in Art,

Kandinsky also pointed the way toward new es-

thetic criteria, for he emphasized the value of the

primitive, the ethnographic, and the popular, es-

tablishing a fragile alliance with a new generation

of Moscow artists such as Natalia Goncharova

(1881–1962) and Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964).

Praising the color and simplicity of Gauguin and

Matisse, on the one hand, and the vitality of in-

digenous art forms, on the other, the “new bar-

barians” rejected Symbolist mystery in favor of the

concrete and the material. Their first major exhibi-

tion, “The Jack of Diamonds” of 1910–1911, sig-

naled the tarnishing of the Silver Age, for it showed

the vulgar and the ugly, promoting graffiti, chil-

dren’s drawings, and store signboards as genuine

works of art instead of the impalpable visions of

the astral plane and religious ecstasy.

The destiny of the Russian Silver Age was both

full and empty. On the one hand, the Symbolists

left a positive construction, because some of their

ideas and artifacts prefigured the linguistic and vis-

ual experiments of the avant-garde in the 1910s

and 1920s, including the geometric reductions of

Malevich known as Suprematism. Even the notion

of a single and cohesive style joining architecture

and the applied arts, promoted by the Construc-

tivists in the wake of the October Revolution, can

be viewed as outgrowths of the Symbolists’ con-

cern with the total, organic work of art. On the

other hand, if the Russian Symbolist poets and

painters glimpsed beyond the veil, they rarely com-

pleted the voyage to the other shore. As they jour-

neyed, they erred in bold transgressions and called

for synthesis and synaesthesia as they sought a

spiritual equilibrium for their uneasy era. Ulti-

mately, if their fine antennae did pick up the ce-

lestial signals, the sound was so powerful that it

caused a “dérèglement de tous les sens”—and not

just metaphorically, but in the literal meaning of

that phrase.

See also: DIAGILEV, SERGEI PAVLOVICH; FUTURISM;

GOLDEN AGE OF RUSSIAN LITERATURE; KANDINSKY,

VASILY VASILIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bowlt, John E. (1982). The Silver Age: Russian Art of the

Early Twentieth Century and the “World of Art” Group.

Newtonville, MA: Oriental Research Partners.

Brumfield, William C. (1991). The Origins of Modernism

in Russian Architecture. Berkeley: University of Cali-

fornia Press .

Elliott, David, ed. The Twilight of the Tsars: Russian Art at

the Turn of the Century. Catalog of exhibition at the

Hayward Gallery, London, March 7–May 19, 1991.

Engelstein, Laura. (1992). The Keys to Happiness. Sex and

the Search for Modernity in Fin-de-siècle Russia. Ithaca,

NY: Cornell University Press.

SILVER AGE

1396

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Kandinsky, Vasily. (1946). On the Spiritual in Art. New

York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Proffer, Carl and Proffer, Ellendea, eds. (1975). The Silver

Age of Russian Culture: An Anthology. Ann Arbor, MI:

Ardis.

Pyman, Avril. (1994). A History of Russian Symbolism.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Richardson, William. (1986). “Zolotoe runo” and Russian

Modernism. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis .

Rosenfeld, Alla, ed. (1999). Defining Russian Graphic Arts

1898–1934: From Diaghilev to Stalin. New Brunswick,

NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Salmond, Wendy, ed. The New Style: Russian Perceptions

of Art Nouveau. Special issue of the journal Experi-

ment 7 (2001).

J

OHN

E. B

OWLT

SIMEON

(1316–1353), prince of Moscow and grand prince

of Vladimir.

Like his father Ivan I Danilovich “Moneybag,”

Simeon Ivanovich (“the Proud”) collaborated with

the Tatar overlords and secured a preferential sta-

tus. After Ivan I died in 1340, Simeon and rival

claimants visited the Golden Horde in Saray to so-

licit the patent for the grand princely throne. Khan

Uzbek gave it to Simeon, who became the khan’s

obedient vassal and was thus able to wield at least

limited jurisdiction over rival princes. He also ob-

tained the khan’s backing for his campaigns against

Grand Prince Olgerd of Lithuania who, in the

1340s, increased his incursions into western Rus-

sia. Simeon waged war on Novgorod and forced it

to recognize him as its prince and to pay Tatar trib-

ute to him. With the help of Metropolitan Feog-

nost he asserted greater control over the town than

his father had done. During Simeon’s reign the

principality of Suzdal–Nizhny Novgorod replaced

Tver in the rivalry for supremacy with Moscow.

Although the Tatars helped Simeon fight foreign

enemies, after 1342 Khan Jani-Beg refused to help

him become stronger than his rivals in northeast

Russia. Specifically, he prevented Simeon from in-

creasing the size of his domain and his power as

grand prince.

Simeon’s agreement with his brothers in the

late 1340s alludes, for the first time, to the ap-

panage system of Moscow. The document describes

the relationship between the grand prince and his

brothers and recognizes the domains that Ivan I al-

located to his sons as hereditary appanages. On

April 26, 1353, Simeon died from the plague.

See also: APPANAGE ERA; GRAND PRINCE; MOSCOW; MUS-

COVY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fennell, John L. I. (1968). The Emergence of Moscow,

1304–1359. London: Secker and Warburg.

Martin, Janet. (1995). Medieval Russia, 980–1584. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

SIMONOV, KONSTANTIN MIKHAILOVICH

(1915–1979), Russian writer and Writers’ Union

official who specialized in describing the Great Pa-

triotic War.

Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov was born in

Petrograd, the son of a military schoolteacher. He

entered a factory school and began working in var-

ious factories while he began writing poetry. He

published his first poems in 1934 and enrolled in

the Gorky Literary Institute. After graduation in

1938, he worked as a journalist and served as a

correspondent for Red Star (Krasnaya zvezda) dur-

ing the war.

During the war, he began to write plays and

fiction about his experiences and became quite pop-

ular during the 1940s and 1950s. The novel Days

and Nights described the battle of Stalingrad in a

realistic, natural manner. His other work was noted

for its adherence to dictates of Socialist Realism. He

won numerous awards, including six Stalin prizes,

a Lenin prize, and the Hero of Socialist Labor medal.

Simonov served in many editorial and adminis-

trative positions during his career. He was editor-in-

chief of Literaturnaia Gazeta (1950–1953), a

secretary of the Union of Soviet Writers (1946–1950,

1967–1969), a member of Central Committee of

Communist Party (1952–1956), and a deputy to

the Supreme Soviet. Most interestingly, he was ed-

itor-in-chief of Novyi mir from 1954–1958, where

he presided over the publication of Vladimir Dud-

intsev’s Not by Bread Alone (Ne khlebom edinim). Un-

der attack, he soon retreated from this liberal

position and thereafter remained within the official

bounds of propriety.

In his posthumous memoirs, Through the Eyes

of a Man from My Generation (Glazami cheloveka

moego pokoleniia), Simonov provides great insight

SIMONOV, KONSTANTIN MIKHAILOVICH

1397

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

into the world of Soviet literary politics under Stalin

and after. His life and work demonstrate the com-

promises some writers chose as they negotiated the

contours of official Soviet culture.

See also: JOURNALISM; NOVY MIR; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Simonov, Konstantin. (1945) Days and Nights, tr. J.

Barnes. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Simonov, Konstantin. (1989). Always a Journalist.

Moscow: Progress Press.

K

ARL

E. L

OEWENSTEIN

SIMONOV MONASTERY

The Simonov Monastery in Moscow was founded

in 1370 by Fyodor, a disciple of Russia’s greatest

and most influential medieval saint, Sergius. Over

the centuries, the Simonov was to become one of

the richest monasteries in Russia. Early twentieth

century official church records place the Simonov

in the top 10 percent based on wealth.

The monastery had six major churches on its

grounds. Among them were churches dedicated to

The Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God, to the Dor-

mition of the Virgin, and to St. Nicholas the Mir-

acle Worker. Many churches had attached side

chapels (or side altars) as well. The Tikhvin Icon

church had, for example, side chapels dedicated to

Basil the Blessed, a famous holy fool; to the mar-

tyrs Valentina and Paraskeva; to St. Sergius; to

Athanasius of Alexandria and the martyr Glykeria;

and to saints Xenophont and Maria. This indicated

a complex and intricate pattern of church struc-

ture, one that pertained to the larger, better en-

dowed monasteries.

Two of the Simonov Monastery’s leading fig-

ures became patriarchs of the Russian Church. Job,

who was appointed abbot of Simonov in 1571, was

the first patriarch in Russia (1589). In 1642, Joseph,

the archimandrite of the Simonov Monastery, was

elected to the patriarchy.

During the War of 1812 the Simonov was

looted by the Napoleonic armies when they entered

a burning Moscow. However, it quickly regained

its material well-being. Much of its income was de-

rived from visitors, pilgrims, and donations. Land

holdings outside Moscow generated income from

the production and milling of grain. In these prac-

tices, it typified many other Russian monasteries.

Of the many famous people buried there, one of

the better known is the nineteenth-century writer

Ivan Aksakov.

See also: CAVES MONASTERY; KIRILL-BELOOZERO MO-

NASTERY; MONASTICISM; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH;

SERGIUS, ST.; TRINITY ST. SERGIUS MONASTERY

N

ICKOLAS

L

UPININ

SINODIK

The sinodik pravoslaviya corresponds to the synod-

icon adopted at the council of the Greek Orthodox

Church in 843 that condemned the iconoclasts. By

the twelfth century, the term also came to mean

“memorial book.”

The sinodik pravoslaviya contains the decisions

of the seven ecumenical councils, the names of

those under anathema, and a list of important per-

sons who deserve “many years of life,” that is, to

be remembered eternally. The text was read only

once per year in the Orthodox rite, on the first Sun-

day of Lent. In addition to the Greek version, there

are also more recent Georgian, Serbian, and Bul-

garian versions. The Russian Primary Chronicle men-

tions a sinodik under the year 1108, but the Greek

form was probably not replaced by a Russian trans-

lation until 1274. Starting around the end of the

fourteenth century, the names of fallen warriors

were also entered in the sinodik pravoslaviya. In

1763, the metropolitan of Rostov, Arseny Matsey-

vich, read aloud the anathema in the sinodik pra-

voslaviya on those who touch church property as

a protest against Catherine II’s planned seculariza-

tion of church landholdings.

The word sinodik took on a second meaning in

twelfth-century Novgorod and later in Muscovite

Russia. In this second sense it refers to a memorial

book, corresponding to the Greek Orthodox dip-

tych, containing the names of dead persons who

are to be commemorated in the daily liturgical cy-

cle. Around the end of the fifteenth century, when

the number of donors began to grow rapidly, Mus-

covite monasteries developed a system not found

in other Orthodox countries: Donors’ names were

entered in books organized around the size of the

donation. So-called eternal sinodiki listed the names

of donors who had given relatively modest gifts

and were read throughout the day. “Daily lists”

SIMONOV MONASTERY

1398

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

(the names vary) commemorated the donors of

more substantial gifts and were read only at cer-

tain fixed points in the liturgical cycle. This seg-

mented system flourished until the beginning of

the seventeenth century. Beginning in the late fif-

teenth century, and quite often in the seventeenth,

sinodiki included “introductions” that detailed the

importance and value of care for the deceased.

Many Russian monasteries and churches still main-

tain sinodiki.

See also: DONATION BOOKS; ORTHODOXY; PRIMARY

CHRONICLE; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

L

UDWIG

S

TEINDORFF

SINOPE, BATTLE OF

The battle of Sinope, fought on November 30,

1853, was the last major naval action between sail-

ing ship fleets. The battle resulted from worsening

relations between the Ottoman and Russian em-

pires. For naval historians, the battle is notable for

the first broad use of shell guns, marking the end

of the use of smooth bore cannon that had previ-

ously been the primary naval weapon for nearly

three centuries. In the spring of 1853 Tsar Nich-

olas’s emissary Admiral Alexander Menshikov

broke off negotiations with the Ottoman Empire.

Menshikov opposed plans for a preemptive strike

against the Bosporus, and the Russian Black Sea

Fleet subsequently prepared for a defensive war

within the Black Sea. The Ottoman government or-

dered a squadron of Vice Admiral Osman Pasha to

the Caucasus coast in early November 1853 in sup-

port of Ottoman ground forces, but bad weather

forced the ships to seek shelter at Sinope. A Rus-

sian squadron under Vice Admiral Pavel Stepanovich

Nakhimov on his flagship Imperatritsa Maria-60

decided to attack. Following a war council, Nakhi-

mov ordered his officers in an evocation of Nelson

at Trafalgar: “I grant you the authority to act ac-

cording to your own best judgment, but I enjoin

each to do his duty.” With six ships of the line and

two frigates with 720 guns, Nakhimov attacked an

Ottoman squadron of seven frigates, three corvettes,

two steamers, two brigs, and two transports

mounting 510 guns under shore defenses with 38

pieces of artillery. The shell guns proved lethal in

Nakhimov’s two-columned assault; the only Ot-

toman vessel that managed to escape the carnage

was the steam frigate Taif-20 carrying the British

officer Slade, who brought news of the defeat to

Constantinople. Ottoman losses totaled 15 ships

and 3,000 men with the Russians taking 200 pris-

oners; on the Russian side, 37 were killed and 235

wounded. Osman Pasha, wounded in the engage-

ment, was taken prisoner.

See also: MENSHIKOV, ALEXANDER DANILOVICH; MILITARY,

IMPERIAL ERA; NAKHIMOV, PAVEL STEPANOVICH;

RUSSO-TURKISH WARS; TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Daly, Robert Welter. (1958). “Russia’s Maritime Past,”

In The Soviet Navy, ed. Malcolm George Saunders.

London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

J

OHN

C. K. D

ALY

SINO-SOVIET SPLIT See CHINA, RELATIONS WITH.

SINYAVSKY-DANIEL TRIAL

In September 1965, Soviet authorities arrested a

well-known literary critic, Andrei Sinyavsky, and

a relatively obscure translator, Yuly Daniel, and

charged them with slandering the Soviet system in

works published abroad pseudonymously. The

works in question were often satirical but in no

sense anti-Soviet; in his essay On Socialist Realism,

for example, Sinyavsky (or “Abram Tertz”) advo-

cated nothing more radical than a return to the

adventurous style of Vladimir Mayakovsky. None-

theless, following a January 1966 press campaign

of vicious denunciations, the pair was convicted at

a show trial in February. Sinyavsky received seven

years, and Daniel five, in a strict-regime labor camp.

Conservative elements in the Leonid Brezhnev–

Alexei Kosygin regime, determined to crack down

on the intellectual experimentation of the Nikita

Khrushchev years, presumably intended the affair

as the signal of a stricter cultural line and as a

warning to intellectuals to keep quiet. But the sig-

nal was ambiguous—the conservatives were not

yet firmly in control—and the warning ineffectual.

Sinyavsky and Daniel refused to play their assigned

roles, pleading not guilty and defending themselves

in court vigorously. A public Moscow protest

against the arrests in December 1965 was followed

by a petition campaign, an increase in open protest

and samizdat, and, ultimately, the appearance of

the Chronicle of Current Events in April 1968. In fact,

the Sinyavsky-Daniel case is widely viewed as a

SINYAVSKY-DANIEL TRIAL

1399

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

spark that galvanized the dissident movement by

raising the specter of a return to Stalinism and by

convincing many intellectuals that it was futile to

work within the system.

See also: DISSIDENT MOVEMENT; MAYAKOVSKY, VLADIMIR

VLADIMIROVICH; SHOW TRIALS; THAW, THE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hayward, Max, ed. and tr. (1967). On Trial: The Soviet

State versus “Abram Tertz” and “Nikolai Arzhak,” re-

vised and enlarged edition. New York and Evanston,

IL: Harper & Row.

J

ONATHAN

D. W

ALLACE

SIXTH PARTY CONGRESS See OCTOBER REVOLU-

TION.

SKAZ

A literary term originally defined as “orientation

toward oral speech” in prose fiction, can also indi-

cate a type of oral folk narrative.

Boris Eikhenbaum first described skaz, derived

from the verb skazat (“to tell”), in a pair of 1918

articles as a kind of “oral” narration that included

unmediated or improvisational aspects. Formalists

and other critics developed this analytical tool dur-

ing the 1920s, including Yuri Tynianov (1921),

Viktor Vinogradov (1926), and Mikhail Bakhtin

(1929). Tynianov analyzed the effect of skaz, ar-

guing that it enabled the reader to enter the text,

but did not really clarify the mechanism through

which it worked.

Vinogradov and Bakhtin helped refine the con-

cept of skaz as a stylistic device. Vinogradov de-

veloped the idea that skaz comprised a series of

signals that aroused in the reader a sense of speech

produced by utterance, not writing. Bakhtin placed

skaz within his own larger theory of narration,

defining it as one kind of “double-voiced utterance”

(the others being stylization and parody) in which

two distinct voices—the author’s speech and an-

other’s speech—were oriented toward one another

within the same level of conceptual authority. The

effect of oral speech is, therefore, not the primary

characteristic of skaz for Bakhtin.

Since the 1920s skaz has been identified both

as a distinctive characteristic of Russian literature

(in the work of Gogol, Zamiatin, Zoshchenko, and

others) and as a narrative device present in most

world literatures. Since the beginning of the 1980s

and the rediscovery of Bakhtin’s work, his concept

of skaz has served as a starting point for further

debate: for instance, over whether the relationship

between author and narrator is mutual and inter-

active.

See also: BYLINA; LESKOV, NIKOLAI SEMENOVICH; BAKH-

TIN, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH; GOGOL, NIKOLAI VASI-

LIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hodgson, Peter. (1983). “More on the Matter of Skaz:

The Formalist Model.” In From Los Angeles to Kiev:

Papers on the Occasion of the Ninth International Con-

gress of Slavists, Kiev, September, 1983, ed. Vladimir

Markov and Dean S. Worth. Columbus, OH: Slav-

ica Publishers.

Terras, Victor, ed. (1985). Handbook of Russian Literature.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Titunik, I. R. (1977). “The Problem of Skaz (Critique and

Theory).” In Papers in Slavic Philology, ed. Benjamin

A. Stolz. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

E

LIZABETH

J

ONES

H

EMENWAY

SKOBELEV, MIKHAIL DMITRIYEVICH

(1843–1882), famous officer in the Russian impe-

rial army active in the conquest of Turkestan and

in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1888.

Born to a Russian noble family, Mikhail Sko-

belev became a member of the officer corps of the

Russian army. In 1869, having received an educa-

tion in military schools, he joined Russian forces

completing the conquest of Central Asia.

He first distinguished himself in military oper-

ations in the Fergana Valley (now in Uzbekistan),

where in 1875 anti-Russian rebel forces had over-

thrown the khan of Kokand (allied with Russia).

He quickly formulated his own strategy of colo-

nial war, summed up in the guidelines “slaughter

the enemy until resistance ends,” then “cease

slaughter and be kind and humane to the defeated

enemy.” He destroyed several rebel towns during

his campaign, leaving thousands of dead among

the rebels and the civilian population. When lead-

ers of the revolt surrendered, he recommended to

the tsar that they be pardoned. As a reward for his

military triumph, he was promoted to the rank of

major general and, at the age of thirty, became the

military ruler of the Fergana Valley.

SIXTH PARTY CONGRESS

1400

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

When the Russian Empire declared war on the

Ottoman Empire in 1877, Skobelev joined the Rus-

sian armies moving against the Turks. His bravery

and military skill earned him the command of one

of the Russian armies in the campaign. He led his

troops in the capture of the key Ottoman-fortified

city along the western Black Sea coast protecting

Constantinople. His desire for rapid victory resulted

in heavy losses among his troops, but his exploits

preserved his image in Russia as the triumphant

“White General.”

Skobelev’s final military triumph came in an-

other war in Central Asia. Faced with the revolt of

nomadic Turkmen tribes, the tsarist government

sent him in 1880 to force the nomads to submit to

imperial rule. He was successful, applying once

again his brutal strategy of colonial warfare. In

early 1881 his troops stormed the major Turkmen

fortress of Geok-Tepe (now in Turkmenistan),

slaughtering half of the defenders as well as many

civilians. His reputation among Russian imperial-

ists was at its peak. However, the new tsar, Alexan-

der III, was suspicious of his desire for fame and

his political ambitions. Following Skobelev’s tri-

umph in Turkestan, the government sent him to a

remote military post in western Russia. There he

began a public campaign to restore his reputation,

but died shortly afterward of a heart attack.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; MILITARY, IMPERIAL ERA; RUSSO-

TURKISH WARS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Meyer, Karl, and Brysac, Shareen. (1999). Tournament of

Shadows: The Race for Empire and the Great Game in

Central Asia. New York: Counterpoint Press.

Rich, David. (1998). The Tsar’s Colonels: Professionalism,

Strategy, and Subversion in Late Imperial Russia. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

D

ANIEL

B

ROWER

SKRYPNYK, MYKOLA OLEKSYOVYCH

(1872–1933), Ukrainian Bolshevik leader and ad-

vocate of ukrainization.

Born in Ukraine, Mykola Skrypnyk joined the

revolutionary movement in 1901 as a student at

the St. Petersburg Technological Institute, from

which he never graduated. Until 1917 he lived the

life of a professional revolutionary, organizing the

Bolshevik underground in Saratov, Odessa, Kiev,

and Moscow. During this period, Skrypnyk was

arrested fifteen times and repeatedly exiled to

Siberia, and spent more than a year in voluntary

exile in Switzerland. During the October Revolu-

tion he was a prominent member of the Military

Revolutionary Committee in Petrograd. In 1918, on

the suggestion of Vladimir Lenin, Skrypnyk moved

to Ukraine to counterbalance the Russian chauvin-

ism of the local Bolshevik leadership. He served

there as people’s commissar of labor and later as

head of the People’s Secretariat, the first Soviet gov-

ernment in Ukraine, and in April 1918 he was in-

strumental in the creation of the Communist Party

(Bolshevik) of Ukraine. After the Bolsheviks were

forced to withdraw from Ukraine by the terms of

the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, Skrypnyk joined the

Cheka, but he returned to Ukraine when the Civil

War ended.

As people’s commissar of justice of the Ukrain-

ian Republic (1922–1927), Skrypnyk helped to build

a Soviet Ukrainian state and ensure its rights within

the Soviet Union. Starting in 1923, when the Krem-

lin introduced the policy of nativization, he actively

promoted the implementation of its Ukrainian in-

carnation or ukrainization. During his tenure as

people’s commissar of education (1927–1933), he

was active in ukrainizing the republic’s press, pub-

lishing, education, and culture. Although Skrypnyk

remained an orthodox Bolshevik and an enemy of

Ukrainian nationalism, he stood out as the Ukrain-

ian leader who was most vocal in his opposition to

Moscow’s centralism and great-power chauvinism.

He also distinguished himself by engineering the

standardization of Ukrainian orthography— the so-

called Skrypnykivka system (1927)—and founding

the Ukrainian Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1928).

In 1933, when Josef Stalin condemned his ukrainiza-

tion policies as nationalistic, Skrypnyk committed

suicide. He was rehabilitated in the mid-1950s, and

in post-Soviet Ukraine he is respected as a defender

of Ukrainian culture and sovereignty.

See also: BOLSHEVISM; NATIONALISM IN THE SOVIET

UNION; UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mace, James. (1983). Communism and the Dilemmas of

National Liberation: National Communism in Soviet

Ukraine, 1918–1933. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

Ukrainian Research Institute.

SKRYPNYK, MYKOLA OLEKSYOVYCH

1401

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Martin, Terry. (2001). The Affirmative Action Empire: Na-

tions and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

S

ERHY

Y

EKELCHYK

SLAVERY

Slavery in one form or another has been a central

feature of East Slavic and Russian history from at

least the very beginning almost to the present day.

Its presence and its offshoots have lent a particu-

lar coloration to Russian civilization that can be

found in few other places.

One common social science definition of slav-

ery is that the slave is an outsider; namely, that he

or she is of a different race, religion, caste, or tribe

than that of his or her owner. In cases where that

was not true, slaveholders resorted to fiction, which

made the slave (usually an infant abandoned by its

parents) appear to be an outsider. Or a slave might

be a lawbreaker who by his crime had placed him-

self outside of society: one who, in Orlando Patter-

son’s phrase, was “socially dead.” This could include

debtors, who were regarded as thieves because they

could not or would not repay borrowed money or

goods, or criminals who could not pay fines.

Russia included such outsiders as slaves, but

(along with Korea) also enslaved its own people.

This was unusual and made Russian slavery dis-

tinctive. Because of its atypical nature, some peo-

ple have questioned whether Russian rabstvo and

especially kholopstvo were in fact “really slavery.”

However, a thoughtful examination indicates that

all such individuals in fact were slaves. All varieties

of slaves were treated equally under the law.

From the dawn of Russian history, as every-

where else on Earth at the time, slaves were

typically products of warfare—East Slavic tribes

fighting with each other or with neighboring Tur-

kic, Iranian, Finnic, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Polish,

Germanic, and other peoples. Such victims were

true outsiders who could be either enslaved in Rus

itself or taken abroad into the international slave

trade. Slaves were mentioned in every Russian law

code. As the earliest such code, the Russkaia pravda,

grew in size from its earliest redaction compiled in

about 1016 to its full size, the so-called Expanded

Pravda a special section on slavery was added. It

enumerated some of the avenues into slavery, such

as sale of prior slaves, self-sale, becoming a stew-

ard, and marriage of a free person to a slave. An

indentured laborer could be sold into slavery as rec-

ompense for crimes. As in all slave systems, the

owner was responsible for a slave’s offenses, much

as an owner is responsible for his dog. The heyday

of medieval Russian slavery followed the collapse

of political unity after 1132, and each of the dozen

or so independent principalities waged civil war

against each other as well as the steppe nomads

and neighboring sedentary peoples to the west. As

always—until probably the 1880s—Russia was a

labor-short country, so those desiring extra hands

often enslaved them. Much of twelfth-century

farming was done by slaves living in barracks.

The Mongol invasion and conquest made the

situation worse. The Mongols enslaved skilled in-

dividuals and dispatched them to Karakorum, Sarai,

and other corners of the earth. The dozen or so

principalities of Rus in 1237 fragmented into fifty,

perhaps even one hundred—each enslaving the la-

bor of other principalities. Many of these slaves

were shipped to Novgorod, whose famous slave

market was at the busy intersection of Slave and

High Streets, where professional readers and writ-

ers set up their business composing and reading for

customers the famous birch-bark letters. Slaves

from Novgorod were shipped into the Baltic, to

England, to other Atlantic countries, and into the

Islamic lands of the Mediterranean.

While the unification of the East Slavic lands

by Moscow put an end to the capture of other East

Slavs into slavery, Russia was still short of labor,

and the appetite for slaves did not decline. In Kievan

Rus the Orthodox Church had provided charity, but

this diminished with the rise of Moscow. In order

for the impoverished to survive, the practice began

to develop of those in need selling themselves into

what was described as “full slavery.” This was a

form of perpetual, lifelong slavery in which off-

spring were described as hereditary slaves. Most so-

cieties could not withstand the tension inherent in

enslaving their own people, but this did not seem

to bother the Russians. From the outset Russian so-

ciety had consisted not only of East Slavs, but also

the ruling Varangian/Viking element, conquered

indigenous Iranians, Finns, and Balts, plus any

Turkic, Mongol, or other people who wanted to live

in Rus. There were no barriers to intermarriage

among these peoples, and the sole distinction came

to be (perhaps after 1350, or even the 1650s) those

who allegedly were Orthodox Christians and those

who were not. Thus the insider-outsider dichotomy

was weakly developed, and this perhaps permitted

Russians to enslave their own people.

SLAVERY

1402

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY