Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

In the sixteenth century full slavery came to be

replaced by what is best translated as limited ser-

vice contract slavery (kabalnoye kholopstvo), known

elsewhere (in Parthia) as antichresis. It worked as

follows: A person in need or who did not desire to

control his own life found a person who would buy

him. (Two-thirds of the cases involved primarily

young males, the other third females.) They agreed

on a price; the slave took the money from his buyer

and agreed to work for him for a year in lieu of

paying the interest on the money. If he did not re-

pay the loan (or a third person—presumably an-

other buyer—did not repay it for him), he defaulted

and became a full slave. By the 1590s there were

many such slaves. Serfdom was in full develop-

ment, and the slave had the advantage that he had

to pay no taxes, whereas the serf did. Slavery was

becoming so popular that the powerful govern-

ment unilaterally changed the terms of limited ser-

vice contract slavery: The limitation was changed

from the one year of the loan to the life of the per-

son giving the loan. There was a dual expropria-

tion here: The person taking the loan (i.e., selling

himself) could no longer pay it off, and the person

granting the loan (i.e., buying the slave) could not

pass the slave to his heirs. This became the premier

form of slavery until the demise of the institution

in the 1720s. Two changes were introduced: in the

1620s a maximum price of two rubles, and in the

1630s an increase of the maximum to three rubles.

This meant that some would-be slaves could find

no buyer because their price was too high, whereas

others were forced to sell themselves for less than

their “market price” would have been without the

price controls. Regardless, slavery introduced a

form of dependency such that those who were

manumitted almost always resold themselves upon

the death of the owner, often to the deceased

owner’s heirs. About 10 percent of the entire pop-

ulation were slaves.

Russia was the sole country in the world with

a central office (the Slavery Chancellery) in the cap-

ital controlling the institution of slavery. All slaves

had to be registered. In the 1590s a reregistration

of all slaves was required, in which about half of

all slaves were limited service contract slaves and

the others were of half a dozen other varieties.

There were military captives, subject to return

SLAVERY

1403

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

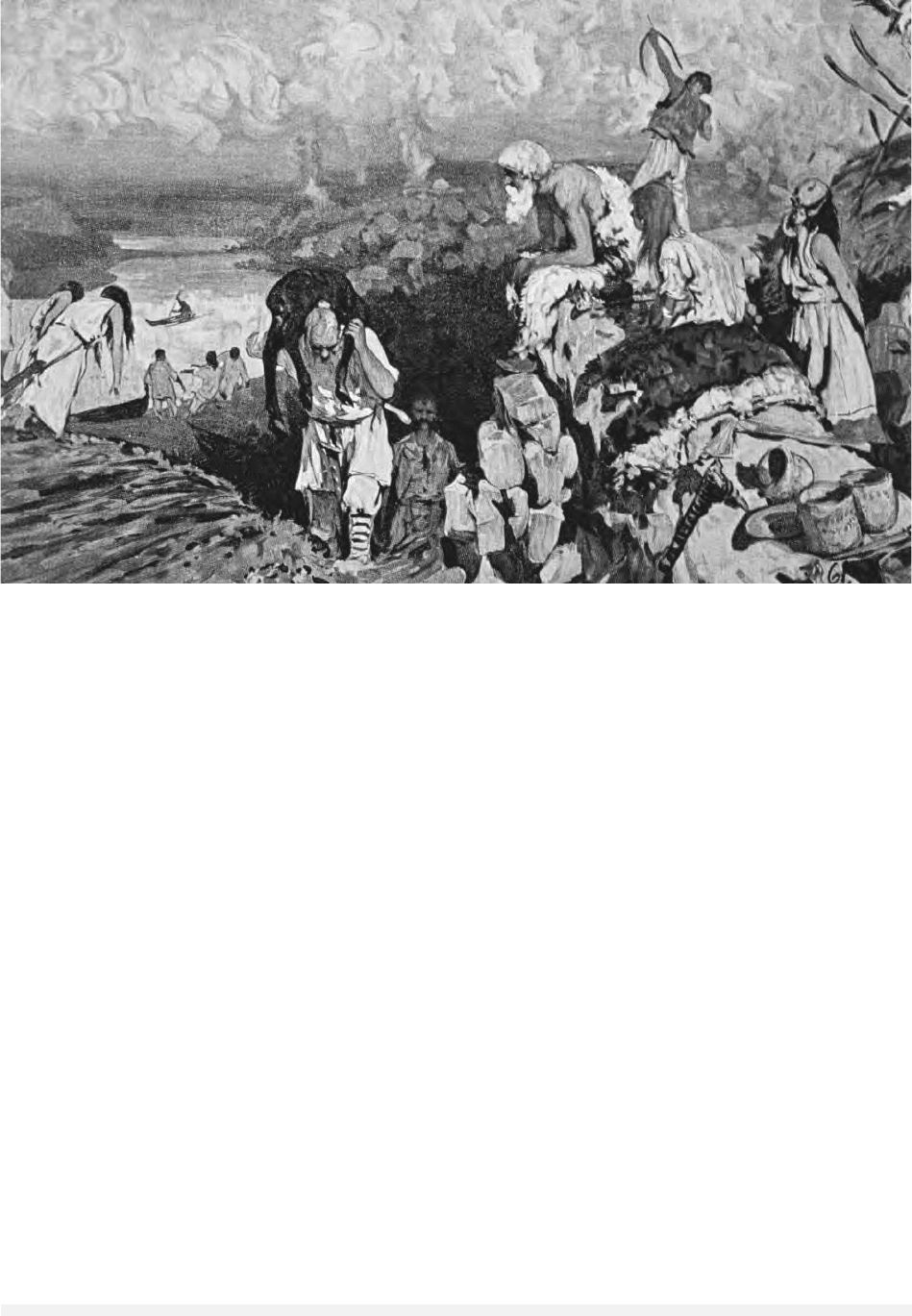

Russian Slave Life

by Sergei Vladimirovich Ivanov. © S

UPER

S

TOCK

home upon the signing of a peace treaty with the

enemy belligerent. There were debt slaves, who had

defaulted on a loan which could be “worked off”

at the rate of 5 rubles per year by an adult male,

2.50 rubles per year by an adult female, and 2

rubles per year by a child over ten. There were in-

dentured slaves, who agreed to work for a term in

exchange for cash, training, and often a promise

that the owner would marry them off before the

end of the term. Those who married slaves were

themselves enslaved, as were those who worked for

someone else for over three months. There were

hereditary slaves, those born to slaves and their off-

spring. The very complex practices of the Slavery

Chancellery were codified into chapter 20 (119 ar-

ticles) of the Law Code of 1649.

Slavery had a profound impact on the institu-

tion of serfdom which borrowed norms from slav-

ery. Farming slaves were converted into taxpaying

serfs in 1679. Household slaves (the vast majority

of all slaves) were converted into house serfs by the

poll tax in 1721. After 1721 serfdom increasingly

took on the appearance of slavery until 1861.

See also: BIRCHBARK CHARTERS; EMANCIPATION ACT; EN-

SERFMENT; FEUDALISM; GOLDEN HORDE; KIEVAN RUS;

LABOR; LAW CODE OF 1649; MUSCOVY SERFDOM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1982). Slavery in Russia, 1450–1725.

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Hellie, Richard, ed. and tr. (1988). The Muscovite Law Code

(Ulozhenie) of 1649. Irvine, CA: Charles Schlacks.

Patterson, Orlando. (1982). Slavery and Social Death.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

SLAVO-GRECO-LATIN ACADEMY

Titled in its first fifty years variously as “Greek

School,” “Ancient and Modern Greek School,”

“Greco-Slavic School,” “Slavo-Latin School,” and

“Greco-Latin School,” the Slavo-Greco-Latin Acad-

emy was the first formal educational institution in

Russian history. Established in 1685, the Academy

became the breeding ground for many secular and

ecclesiastical collaborators of Tsar Peter I. Its

founders and first teachers were the Greek brothers

Ioannikios and Sophronios Leichoudes. From its in-

ception, the Academy followed the well-established

lines of the curriculum and formal structure of

contemporary Jesuit colleges. The Leichoudes di-

vided the curriculum into two parts: The first part

included grammar, poetics and rhetoric; the second

comprised philosophy (including logic) and theol-

ogy. The grammar classes were divided into three

levels: elementary, middle, and higher. The middle

and higher levels were themselves divided into sub-

levels. Instruction was in Greek and Latin, with an

attached school that provided basic literacy in

Church Slavonic. The Leichoudes authored their

own textbooks, largely adapted from contempo-

rary Jesuit manuals. As in Jesuit colleges, the

method of instruction included direct exposure to

ancient Greek and Latin literary and philosophical

texts, as well as an abundance of practical exer-

cises. Student work included memorization, com-

petitive exercises, declamations, and disputations,

as well as parsing and theme writing. On impor-

tant feast days, students exhibited their skills and

knowledge in orations before the Patriarch of

Moscow or royal and aristocratic individuals.

Students were both clergy and laymen, and

came from various social and ethnic backgrounds,

from some of Russia’s top princely scions and

members of the Patriarch’s court, down to children

of lowly servants in monasteries, and included

Greeks and even a baptized Tatar. Several of these

students made their careers in important diplo-

matic, administrative, and ecclesiastical positions

during Peter I’s reign.

In 1701 the Academy was reorganized by de-

cree of Tsar Peter I and staffed with Ukrainian and

Belorussian teachers educated at the Kiev Mohylan

Academy. Until the end of Peter’s reign, the stu-

dent body betrays a slight “plebeianization”: Fewer

members of the top aristocratic families attended

classes there. In addition, many more of the stu-

dents were clergymen. The curriculum retained the

same scholastic content, but the language of in-

struction now was exclusively Latin.

Reorganized in 1775 under the supervision

of Metropolitan Platon of Moscow (in office,

1775–1812), the Academy expanded its curriculum

to offer classes in church history, canon law, Greek,

and Hebrew. Finally, in 1814, the Academy was

transferred to the Trinity St. Sergius Monastery

and was restructured into the Moscow Theological

Seminary.

See also: EDUCATION; LEICHOUDES, IOANNIKIOS AND

SOPHRONIOS; PETER I; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

SLAVO-GRECO-LATIN ACADEMY

1404

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chrissidis, Nikolaos A. (2000). “Creating the New Educated

Elite: Learning and Faith in Moscow’s Slavo-Greco-

Latin Academy, 1685–1694.” Ph.D. dissertation, Yale

University, New Haven, CT.

N

IKOLAOS

A. C

HRISSIDIS

SLAVOPHILES

The origins of Slavophilism can be traced back to

the ideas of thinkers such as Prince Mikhail

Shcherbatov, Alexander Radishchev, Poshkov, Niko-

lai Novikov, and Nikolai Karamzin, all of whom

contrasted ancient pre-Petrine Russia with the

modern post-Petrine embodiment, stressing the

uniqueness of Russian traditions, norms, and ideas.

Most exponents of this school of thought were of

noble birth, and many held government posts, so

they were quite familiar with the workings of the

tsarist autocracy. They were prominent during the

reign of Nicholas I (1825–1855) and emerged after

the Decembrist uprising of 1825 and the Revolu-

tions of 1848 in Europe.

Peter Chaadayev’s (1794–1856) ideas in the

Philosophical Letter (1836) and other works acted

as a catalyst for the emergence of Slavophile ideol-

ogy. Chaadayev gave special emphasis to the need

for Russia to link up with Europe and the Roman

Catholic Church. His views on religion, national-

ity, tradition, and culture stimulated the famous

Slavophile-Westerner debate.

Building on Chaadayev’s legacy, the Slavophiles

developed three main beliefs: samobytnost (origi-

nality), the importance of the Orthodox Church,

and a rejection of the ideas of Peter the Great and

his followers. In addition, they promoted respect

for the rule of law, opposed any restriction on the

powers of the tsar, and advocated freedom of the

individual in terms of speech, thought, and con-

duct.

The Slavophiles believed that Russian civiliza-

tion was unique and superior to Western culture

because it was based on such institutions as the Or-

thodox Church, the village community, or mir, and

the ancient popular assembly, the zemsky sobor.

They supported the idea of autocracy and opposed

political participation, but some also favored the

emancipation of serfs and freedom of speech and

press. Alexander II’s reforms achieved some of these

goals. Over time, however, some Slavophiles became

increasingly nationalistic, many ardently support-

ing Panslavism after Russia’s defeat in the Crimean

War (1854–1856). However, these thinkers were not

united, except insofar as they were radically opposed

to the Westerners, and individually their ideas dif-

fered.

CLASSICAL SLAVOPHILISM

The Slavophiles, by and large, can be grouped into

three categories: classical, moderate, and radical.

Like their opponents, the Westerners, they had a

particular view of Russia’s history, language, and

culture and hence a certain vision of Russia’s fu-

ture, especially its relations with the West. Perhaps

their greatest concern, from the 1830s onwards,

was that Russia might follow the Western road of

development. They were vehemently opposed to

this, arguing that Russia must return to its own

roots and draw upon its own strengths.

Most Slavophiles opposed the reforms intro-

duced by Peter the Great on the grounds that they

had destroyed Russian tradition by allowing alien

Western ideas (such as the French and German lan-

guages) to be imported into Russia. They also main-

tained that Russia had paid too high a price to

become a major European power, namely, moral

degradation. Furthermore, the bureaucracy estab-

lished by Peter the Great was a source of moral

corruption, because the Table of Ranks stimulated

personal ambition and subordinated the nobility

to the bureaucracy. These views were in many

ways shaped by the social and political conditions

that prevailed during the reign of Nicholas I

(1825–1855).

In general, the Slavophiles saw the Westward

swing as a threat to the church, the peasant and

village community, and other Russian institutions.

Many classical Slavophiles were initially influenced

by Nicholas I’s Official Nationality slogan: “Ortho-

doxy, Autocracy, Nationality.” The most important

proponent of classical Slavophilism was Ivan Kir-

eyevsky (1806–1856), who could read French and

German, had traveled in Russia,. and understood the

importance of Tocqueville’s Democracy in America

(1835). Kireyevsky rejected the main intellectual de-

velopments of the time (rationalism, secularism, the

industrial revolution, liberalism) and argued that

Russia, as a backward young nation, was not in a

position to imitate a civilized Europe. He pointed,

for example, to the differences in religion (Catholi-

cism versus Orthodox Christianity) and to the fact

that Russian society consisted of small peasant com-

munes founded upon common land tenure. Like

SLAVOPHILES

1405

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Kireyevsky, Alexei Khomiakov (1804–1860) also

warned against blindly following the West and crit-

icized the impending emancipation of the serfs

(1861). He emphasized spiritual freedom (sobornost)

and Russia’s unique historical mission. Whereas the

West was built upon coercion and slavery, he said,

Russia was founded and maintained by consent,

freedom, and peace. Yuri A. Samarin (1819–1879)

supported Khomiakov’s view, arguing that society,

if left to its own devices, would be torn apart by

division and conflict because individualism only

promoted selfishness and isolation, and thus a

strong centralized state and leader were needed to

maintain order. This was a clear reference to the

danger that Russia would see a rerun of the Revo-

lutions of 1848. As he saw it, chaos would ensue

if Russia followed the example of Western liberal-

ism by introducing constitutionalism and a system

of checks and balances. Other proponents included

the Aksakov brothers, Ivan and Konstantin. Ivan,

at the height of his influence in the late 1870s, fa-

vored the liberation of the Balkan Slavs, whereas

Konstantin advocated the emancipation of the serfs

and was a proponent of the village commune (mir).

Both wanted to preserve Russian traditions and

maintain the ties between the Slavic peoples. In Ivan

Aksakov in particular, one sees clear evidence of the

emergence of Panslavism, which advocated the po-

litical and cultural unity of the Slavic peoples.

MODERATE AND

RADICAL SLAVOPHILISM

Classical Slavophilism eventually gave way to two

other variants of the doctrine. The moderate wing

of the Slavophile movement is associated with

Mikhail P. Pogodin (1800–1875) and Fyodor I.

Tyutchev (1808–1873). Pogodin, a historian and

publisher whose conservative journal The Muscovite

(1841–1856) defended the policies of Nicholas I,

was professor of Russian history at Moscow Uni-

versity (1835–1844) and wrote a history of Russia

(7 vols., 1846–1857) and a study of the origins of

Russia (3 vols., 1871). Tyutchev was a lyric poet

and essayist who spent most of his life (1822–1844)

abroad in the diplomatic service and later wrote po-

etry of a nationalist and Panslavist orientation.

The radical wing of slavophilism was epitomized

by Nikolai Y. Danilevsky (1828–1855). As outlined

in his Russia and Europe (1869), Danilevsky’s aim

was to unite all the countries and peoples who

spoke Slavic languages on the grounds that they

possessed common cultural, economic, and politi-

cal goals. Whereas in the seventeenth century such

aims only received limited government support,

Panslavism became stronger than ever in the post-

Napoleonic period and especially after Russia’s de-

feat in the Crimean War. From the mid-nineteenth

century onward, as Prussia tried to assimilate the

Slavs, the Slavophiles called for solidarity against

foreign oppression, and with this goal in mind

many advocated the establishment of a federation.

This was necessary, in Danilevsky’s view, in order

to protect all Slavs from European expansion in the

east. The Russian government in the 1870s used

these ideas to justify russification and an increas-

ingly expansionist policy. All in all, with the ad-

vance of Russian liberalism and constitutionalism

at the end of the nineteenth century, the Panslav-

ists tried to distance themselves from the classical

and moderate Slavophiles.

THE SLAVOPHILE LEGACY

The demise of Slavophilism in the nineteenth cen-

tury was primarily due to the widespread divisions

between those favoring conservative reform and

those advocating a more extremist Panslavism. Like

the populists, many Slavophiles argued that Nicholas

I was incapable of reform, as shown by his re-

pressive reign, and thus a more nationalist stance

was needed.

Between the Russian Revolution and the rise of

Josef Stalin, this ideology was largely rejected by

the Soviet regime, but following the rise of National

Socialism in Germany, Panslavism was revived, and

it became very prominent during World War II. In

the late Soviet period and especially in the post-

communist era, the Slavophile ideology was once

again promoted by Vladimir Zhirinovsky and other

nationalists who sought to put Russia first and

to protect it against a hostile West. Many neo-

Slavophiles wished to see the restoration of the USSR

and the Soviet Empire, and a return to Orthodoxy.

Thus the legacy of the Slavophiles remains impor-

tant and influential in contemporary Russia.

See also: MIR; NATIONALISM IN TSARIST EMPIRE; NATION

AND NATIONALITY; PANSLAVISM; NICHOLAS I; PETER

I; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH; RUSSIFICATION;

TABLE OF RANKS; WESTERNIZERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Devlin, Judith. (1999). Slavophiles and Commissars: Ene-

mies of Democracy in Modern Russia. London: Macmil-

lan.

Walicki, Andrei. (1975). The Slavophile Controversy: His-

tory of a Conservative Utopia in Nineteenth-Century

SLAVOPHILES

1406

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian Thought, tr. Hilda Andrews-Rusiecka. Ox-

ford: Clarendon Press.

Williams, Christopher, and Hanson, Stephen E. (1999).

“National Socialism, Left Patriotism or Superimpe-

rialism? The Radical Right in Russia.” In The Radical

Right in East-Central Europe, ed. Sabrina P. Ramet.

University Park: Penn State University Press.

C

HRISTOPHER

W

ILLIAMS

SLUTSKY, BORIS ABROMOVICH

(1919–1986), Russian poet and memoirist.

Brought up in Kharkov, Boris Abramovich

Slutsky moved to Moscow in 1937 to study law

and soon began a simultaneous literature course.

On the outbreak of World War II he volunteered

and went into battle as an infantry officer. Soon

wounded in action, he spent the remainder of the

war as a political officer, joining the Party in 1943.

He ended up as a highly decorated Guards major,

having campaigned all the way to Austria.

In 1945 he returned to Moscow and after con-

valescence made a living writing radio scripts, but

in 1948 he was deprived of this work because of his

Jewish origin. Sponsored by Ilya Erenburg, he was

accepted in the Union of Writers in 1957 and there-

after was a professional poet. He made a lasting rep-

utation with unprecedentedly unheroic poems

about the war, but he was soon upstaged by the

more flamboyant younger poets of the Thaw un-

der Nikita Khrushchev, poets more concerned with

the future than with the past. Slutsky steadily con-

tinued publishing original poetry and also transla-

tions, until on the death of his wife in 1977 at which

point he suffered a mental collapse, which was un-

derlain by the lingering effects of his wounds.

Thereafter he was silent. From the beginning of his

career Slutsky acquiesced in the censoring of his

work, never moving into dissidence; notoriously, in

1958 he spoke and voted for the expulsion of Paster-

nak from the Union of Writers, an action for which

he privately never forgave himself.

After Slutsky’s death, it was found that well

over half of his poetry had never been published. The

appearance of this suppressed work in the decade af-

ter he died revealed that Slutsky had been by far the

most important poet of his generation. In hundreds

of short lyrics he had chronicled his life and times,

paying attention to everything from high politics to

the routines of everyday life and tracing the evolu-

tion of his society from youthful idealism through

terrible trials to decline and imminent fall. He cre-

ated a distinctive poetic language, purged of con-

ventional poetic ornament, that has been highly

influential. His prose memoirs about his military

service, equally plain and unconventional, were only

published fifty years after the end of the war.

See also: THAW, THE; UNION OF SOVIET WRITERS; WORLD

WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Slutsky, Boris. (1999). Things That Happened, ed. and tr.

G. S. Smith. Glas (Moscow, Russia), English; v. 19.

Moscow, GLAS; Chicago: Ivan Dee.

G

ERALD

S

MITH

SLUTSKY, YEVGENY YEVGENIEVICH

(1880–1948), mathematical statistician and econ-

omist.

The most profoundly original of all Russian

contributors to economic theory, Yevgeny Slutsky

was born in Yaroslavl and studied mathematics in

Ukraine. His first major publications were in the

field of statistics and on the importance of cooper-

atives. In 1915 he published a seminal article on

the theory of consumer behavior. This demon-

strated how the consequence of a price change on

the quantity of a good demanded could lead to a

residual variation in demand, even with a com-

pensating increase in income. John Hicks rediscov-

ered this work in the West in the 1930s, naming

the Slutsky equation the “Fundamental Equation

of Value Theory.” After 1917 Slutsky worked on

analyzing the effects of paper currency emission,

on the axiomatic foundations of probability the-

ory, and on the theory of stochastic processes. This

yielded a new conception of the stochastic limit.

As a consequence, in 1925 Nikolai Kondratiev

asked Slutsky to join the Conjuncture Institute in

Moscow, for which he wrote his groundbreaking

paper on the random generation of business cycles.

This opened up a new avenue of cycle research by

hypothesizing that the summation of mutually in-

dependent chance factors could generate the ap-

pearance of periodicity in a random series. In the

1920s Slutsky also worked on the praxeological

foundations of economics, but with the closure of

the Conjuncture Institute in 1930, he turned back

to statistics. He subsequently worked in the Central

SLUTSKY, YEVGENY YEVGENIEVICH

1407

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Institute of Meteorology, in Moscow University,

and in the Steklov Mathematical Institute. Here

Slutsky computed the functions of variables, which

led to the posthumous publication of tables for the

incomplete Gamma-function and the chi-squared

probability distribution. He died of natural causes

in 1948.

See also: KONDRATIEV, NIKOLAI DMITRIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, R. G. D. (1950). “The Work of Eugen Slutsky.”

Econometrica 18:209–216.

Slutsky, E. E. (1937). “The Summation of Random

Causes as the Source of Cyclic Processes.” Economet-

rica 5:105–146.

Slutsky, E. E. (1953). “On the Theory of the Budget of

the Consumer.” In American Economic Association,

Readings in Price Theory. London: Allen & Unwin.

V

INCENT

B

ARNETT

SMOLENSK ARCHIVE

The Smolensk Archive comprises the Smolensk re-

gional records of the All-Union Communist Party

from the October Revolution in 1917 to the Ger-

man invasion of the USSR in 1941. The German

Army captured the Smolensk Archive when it in-

vaded Russia in 1941 and in 1943 moved the con-

tents to Vilnius. They were subsequently recovered

by the Soviet authorities in Silesia in March 1946.

American intelligence officers removed the files to

a restitution center near Frankfurt am Main in

1946.

The archive contains the incomplete and frag-

mentary records of the Smolensk and Western

Oblast (regional) committees (obkom). These include

the minutes of meetings, resolutions, decisions, and

directives made by Communist Party officials, as

well as details on Party work relating to agricul-

ture, especially collectivization policy, machine trac-

tor stations, trade unions, industry, armed forces,

censorship, education, women, the control com-

mission, and the purges. The archive also contains

secret police, procuracy, court, and militia reports

as well as private and personal files and the mis-

cellaneous records of the city (gorkom) and district

(raikom) committees. Between 5 and 10 percent of

the archive does not pertain to Smolensk, but com-

prises material seized by the Germans in other parts

of the USSR. The originals of these documents were

presented to the National Archives in Washington,

D.C. Pursuant to an agreement made at the 1998

Washington Conference on Holocaust Era assets,

the United States returned most of the archive to

Russia on in December 2002. The archives were es-

pecially important to Western scholars because

they provided an insider’s perspective on many his-

torical developments that would otherwise have

been unavailable in the era before Mikhail Gor-

bachev raised the restrictions on access to Soviet

archival materials.

See also: ARCHIVES; COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET

UNION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fainsod, Merle. (1958). Smolensk under Soviet Rule. Lon-

don: Macmillan.

Getty, J. Arch. (1999). Origins of the Great Purges: The So-

viet Communist Party Reconsidered, 1933–38. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy. (1995). “The Odyssey of the

‘Smolensk Archive’: Plundered Communist Records

for the Service of Communism.” In Carl Beck Occa-

sional Papers in Russian and East European Studies,

No. 1201. Pittsburgh: Center for Russian and East

European Studies, University of Pittsburgh.

National Archives and Records Service. (1980). Guide to

the Records of the Smolensk Oblast of the All-Union

Communist Party of the Soviet Union, 1917–41. Wash-

ington, DC: Author.

C

HRISTOPHER

W

ILLIAMS

SMOLENSK WAR

This unsuccessful campaign to recover the western

border regions lost to the Polish-Lithuanian Com-

monwealth at the end of the Time Of Troubles

marked Muscovy’s first major experiment with the

new Western European infantry organization and

line tactics.

The Treaty of Deulino (1618) ended the Polish

military intervention exploiting Muscovy’s Time Of

Troubles and established a fourteen-year armistice

between Muscovy and the Polish-Lithuanian Com-

monwealth. But it came at a high price for the

Muscovites: the cession to the Commonwealth of

most of the western border regions of Smolensk,

Chernigov, and Seversk. This was a vast territory,

running from the southeastern border of Livonia

to just beyond the Desna River in northeastern

SMOLENSK ARCHIVE

1408

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Ukraine. It held more than thirty fortress towns,

the most strategic of which was Smolensk, the

largest and most formidable of all Muscovite

fortresses and guardian of the principal western

roads to Moscow. Upon his return from Polish

captivity in 1619, Patriarch Filaret, father of Tsar

Mikhail, made a new campaign to recover Smolensk,

Chernigov, and Seversk from the Poles the primary

objective of Muscovite foreign policy.

Most of the diplomatic preconditions for such

a revanche appeared to be in place by 1630, and by

this point the Muscovite government had succeeded

in restoring its central chancellery apparatus and

fiscal system. It was now able to undertake a mas-

sive reorganization and modernization of its army

for the approaching war with the Commonwealth.

It imported Swedish, Dutch, and English arms to

the cost of at least 50,000 rubles; it offered large

bounties to recruit Western European mercenary

officers experienced in the new infantry organization

and line tactics; and it set these mercenary officers

to work forming and training New-Formation Reg-

iments—six regiments of Western style infantry-

men (soldaty), a regiment of heavy cavalry (reitary),

and a regiment of dragoons (draguny). These regi-

ments were drilled in the new European tactics and

outfitted and salaried at treasury expense, unlike

the old Pomestie-based cavalry army. The New

Formation infantry and cavalry would comprise a

little more than half of the 33,000-man expedi-

tionary army on the upcoming Smolensk cam-

paign. Muscovy had never before experimented

with New Formation units on such a scale.

The death of Polish King Sigismund III in April

1632 led to an interregnum in the Commonwealth

and factional struggle in the Diet. Patriarch Filaret

took advantage of this confusion to send generals

M. B. Shein and A. V. Izmailov against Smolensk

with the main corps of the Muscovite field army.

By October, Shein and Izmailov had captured more

than twenty towns and had placed the fortress of

Smolensk under siege. The Polish-Lithuanian gar-

rison holding Smolensk numbered only about two

thousand men, and the nearest Commonwealth

forces in the region (those of Radziwill and Gon-

siewski) did not exceed six thousand. But the

besieging Muscovite army suffered logistical prob-

lems and desertions; their earthworks did not com-

pletely encircle Smolensk and did not offer enough

protection from attack from the rear. Meanwhile

the international coalition against the Common-

wealth began to unravel, with the result that in

August 1633, Wladyslaw IV, newly elected King

of Poland, arrived in Shein’s and Izmailov’s rear

with a Polish relief army of 23,000 and placed the

Muscovite besiegers under his own siege. In Janu-

ary 1634 Shein and Izmailov were forced to sue for

armistice in order to evacuate what was left of their

army. They had to leave their artillery and stores

behind.

On their return to Moscow, Shein and Izmailov

were charged with treason and executed. By the

terms of the Treaty of Polianovka (May 1634) the

Poles received an indemnity of twenty thousand

rubles and were given back all the captured towns

save Serpeisk. The next opportunity for Muscovy

to regain Smolensk, Seversk, and Chernigov came

a full twenty years later when Bogdan Khmelnit-

sky and the Ukrainian cossacks sought Tsar Alexei’s

support for their war for independence from the

Commonwealth.

See also: FILARET ROMANOV, METROPOLITAN; NEW-

FORMATION REGIMENTS; POLAND; THIRTEEN YEARS’

WAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fuller, William C., Jr. (1992). Strategy and Power in Rus-

sia, 1600–1914. New York: Free Press.

B

RIAN

D

AVIES

SMOLNY INSTITUTE

Catherine II (the Great) founded the Smolny Insti-

tute for Girls, officially the Society for the Up-

bringing of Noble Girls, in 1764. Its popular name

comes from its site in the Smolny Monastery on

the left bank of the Neva River in St. Petersburg.

Inspired by Saint-Cyr, a boarding school for girls

in France, Smolny was part of Catherine’s educa-

tional plan to raise cultured, industrious, and loyal

subjects.

Ivan Betskoy, the head of this reform effort, was

heavily influenced by Enlightenment theorists.

Drawing on the ideas of John Locke and Jean-

Jacques Rousseau, Betskoy’s pedagogical plan for

Smolny emphasized moral education and the im-

portance of environment. Girls lived at Smolny con-

tinuously from age five to eighteen without visits

home, which were deemed corrupting. As at all-male

schools such as the Corps of Cadets and the Acad-

emy of Arts, Smolny stressed training in the fine

arts, especially dance and drama. The curriculum

also included reading, writing, foreign languages,

SMOLNY INSTITUTE

1409

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

physics, chemistry, geography, mathematics, his-

tory, Orthodoxy, needlepoint, and home economics.

The range of subjects led Voltaire to declare Smolny

superior to Saint-Cyr. In 1765, a division with a less

extensive curriculum was added for the daughters

of merchants and soldiers.

Catherine held public exams and performances

of plays at Smolny, and took her favorite pupils

on promenades in the Summer Gardens. Portraits

of these favorites were commissioned from the

painter Dmitry Levitsky. Smolny also became a

stop for visiting foreign dignitaries. Its graduates

were known for their manners and talents and were

considered highly desirable brides. Some became

teachers at the school, and a few were promoted to

ladies-in-waiting at court.

Peter Zavadovsky, who directed Catherine’s

commission to establish a national school system,

succeeded Betskoy as de facto head of Smolny in

1783. He replaced French with Russian as the

school’s primary language and altered the curricu-

lum to emphasize the girls’ future roles as wives

and mothers.

After Catherine’s death in 1796, Maria Fe-

dorovna took over the institute and made changes

that set Smolny’s course for the rest of its exis-

tence. The school’s administration became less per-

sonal and more bureaucratic. The age of admittance

was changed from five to eight, in recognition of

the importance of mothering during the early years

of a child’s life, and the rules forbidding visits home

were relaxed.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Smolny

maintained its reputation as the most elite educa-

tional institution for girls. Its name was regarded

as synonymous with high cultural standards,

manners, and poise, although sometimes its grad-

uates were considered naive and ill-prepared for life

outside of Smolny. The many references to Smolny

in the Russian literature of the eighteenth and nine-

teenth centuries attest to the school’s cultural sig-

nificance.

In October 1917, Vladimir Lenin and the Bol-

sheviks appropriated the Smolny Institute and made

it their headquarters until March 1918. Since then,

the Smolny campus has continued to be used for

governmental purposes, eventually becoming home

to the St. Petersburg Duma. Several rooms have

been preserved as a museum of the institute’s past.

See also: CATHERINE II; EDUCATION; ENLIGHTENMENT, IM-

PACT OF; ST. PETERSBURG

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Black, Joseph L. (1979). Citizens for the Fatherland: Edu-

cation, Educators, and Pedagogical Ideals in Eighteenth

Century Russia. New York: Columbia University

Press.

Nash, Carol. (1981). “Educating New Mothers: Women

and the Enlightenment in Russia.” History of Educa-

tion Quarterly 21:305–306.

A

NNA

K

UXHAUSEN

SMYCHKA

Smychka, meaning “alliance” or “union” in Rus-

sian, was used during the New Economic Policy

(NEP), particularly by those Bolsheviks who sup-

ported a moderate policy toward the peasantry, to

describe a cooperative relationship between work-

ers and peasants.

In 1917 the revolutionary alliance of proletariat

and peasantry against the tsarist ruling classes led

to victory, but by the end of the Civil War the smy-

chka had been severely weakened by harsh War

Communism policies of forcible confiscation of

grain. Vladimir Lenin introduced the NEP in 1921

to restore the smychka, ending confiscatory poli-

cies toward the peasantry and allowing limited pri-

vate enterprise.

The Bolsheviks were in the awkward position

of claiming to represent the proletariat but actu-

ally ruling over a peasant population that they re-

garded as potentially bourgeois. In the 1920s they

debated what policies should be applied to the peas-

antry, that is, what the smychka should mean. In

his last writings, particularly “On Cooperation”

and “Better Fewer, But Better” (both 1923), Lenin

argued that the smychka meant gaining the peas-

ants’ trust by recognizing and meeting their needs.

Through cooperatives, he said, the vast majority of

peasants could be gradually won over to socialism.

Nikolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, and others mem-

bers of the right built their program of gradual evo-

lution to socialism on Lenin’s last writings, seeing

the smychka as a permanent feature of Soviet life

and calling for concessions to the peasantry. The

left feared that the peasant majority could swallow

the revolution and resisted concessions, hoping that

rapid industrialization would end the need for al-

liance with the peasantry.

The inherent tensions between Bolshevik goals

and peasant needs threatened to rupture the smy-

chka. In the 1923 Scissors Crisis, prices for agri-

SMYCHKA

1410

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

cultural products plummeted at the same time that

those of state-produced manufactured goods rose

sharply, opening a price gap that discouraged peas-

ants from marketing agricultural products. Ad-

justments kept the smychka in place, and 1925 was

the high point of pro-peasant policies. The Grain

Crisis of 1928 and subsequent defeat of the right

weakened the smychka, and the massive collec-

tivization drive of 1929–1930 ended it completely.

See also: COLLECTIVIZATION OF AGRICULTURE; GRAIN CRI-

SIS OF 1928; NEW ECONOMIC POLICY; SCISSORS CRISIS;

WAR COMMUNISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cohen, Stephen F. (1971). Bukharin and the Bolshevik Rev-

olution. New York: Random House.

Lewin, Moshe. (1968). Russian Peasants and Soviet Power.

Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

C

AROL

G

AYLE

W

ILLIAM

M

OSKOFF

SOBCHAK, ANATOLY ALEXANDROVICH

(1937–2000), law professor; mayor of St. Peters-

burg.

Anatoly Sobchak was one of the leading liberal

politicians of the perestroika era. Born in Chita, he

completed a law degree at Leningrad State Univer-

sity in 1959. He settled permanently in Leningrad

in1962 and joined the faculty of Leningrad State

University in 1973, heading the economic law in-

stitute and rising to be dean. Unusually for so se-

nior an academic, Sobchak was for many years not

a member of the Communist Party. He only joined

during the presidency of Mikhail Gorbachev, be-

coming a candidate member in May 1987, and a

full member in June 1988. The next year he was

elected to the Congress of People’s Deputies, where

he became a leader of the Inter-Regional Deputies

group and chaired the committee investigating the

massacre of demonstrators by Soviet troops in Ti-

flis in April 1989.

A loyal supporter of Boris Yeltsin, Sobchak was

elected mayor of Leningrad in June 1991, the same

day that a referendum approved changing the city’s

name to St. Petersburg. He opposed the August

1991 coup attempt and persuaded the army not to

deploy troops in the city. Sobchak presided over the

liberalization of the city’s economy, whose many

defense plants had suffered greatly from the Soviet

economic collapse. On the recommendation of the

rector of Leningrad State University, Stanislav

Merkouriev, Sobchak hired a young ex-KGB offi-

cer, Vladimir Putin, to handle relations with for-

eign investors. Putin had been a student in one of

Sobchak’s classes but they were not personally ac-

quainted. Putin became Sobchak’s deputy in 1993

and ran his re-election campaign in July 1996.

Sobchak, surprisingly, lost to a challenge from his

former deputy, Vladimir Yakovlev.

The next year Yakovlev (known as governor

rather than mayor) filed a libel suit against Sobchak

after the latter accused him of ties to organized

crime in a newspaper interview. In October 1997

Sobchak suffered a heart attack while being ques-

tioned by police about corruption allegations,

mainly pertaining to the distribution of city-owned

apartments. Sobchak went to France for medical

treatment and remained there in voluntary exile—

beyond the reach of investigators.

The rise of Putin (who became head of the Fed-

eral Security Service in July 1998) and the dismissal

of Procurator Yuri Skuratov in April 1999 enabled

SOBCHAK, ANATOLY ALEXANDROVICH

1411

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian politician Anatoly Sobchak was a mentor to President

Vladimir Putin. © V

ITTORIANO

R

ASTELLI

/CORBIS

Sobchak to return to Russia in July 1999. The

charges against him were dropped, but his public

image was tarnished, and he failed to win a seat in

the State Duma in the December 1999 elections.

Sobchak died of a heart attack in February 2000

while on a trip to Kaliningrad as Putin’s envoy. An

emotional Putin attended his funeral and pledged

revenge on his enemies, blaming them for his death.

Observers took this as referring to Vladimir

Yakovlev, but Putin failed to prevent Yakovlev’s re-

election as St. Petersburg governor in May 2000.

Sobchak’s career, in which he evolved from a

principled liberal to a defender of Russian capitalism

and backer of Vladimir Putin, reflected the broader

hopes and disappointments of the Russian transition

from communism. Sobchak himself was aware of

the contradictions, commenting just before his death

that “We have not achieved a democratic, but rather

a police state over the past ten years.”

See also: PERESTROIKA; PUTIN, VLADIMIR VLADIMIROVICH;

ST. PETERSBURG; YAKOVLEV, ALEXANDER NIKO-

LAYEVICH; YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Holiman, Alan. (2000). “Remembering Anatoly Sobchak.”

Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democra-

tization 8(3):324–329.

P

ETER

R

UTLAND

SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC WORKERS PARTY

Social democracy was a product of capitalism in

Imperial Russia around 1900. Until the 1890s,

Russian socialism meant agrarian Populism, an il-

legal, conspiratorial, and terrorist movement of the

educated intelligentsia that placed its faith in the

peasant village commune. After state-funded rail-

road building inspired rapid industrial growth in

Russia, many intellectuals became Marxist Social

Democrats.

Social Democrats believed that they could com-

bine socialism with democracy, without any cen-

tralized state nationalization of property. Karl Marx

had criticized capitalism as both inefficient and un-

just, a cause of violent class struggle that would

lead inevitably to a proletarian class seizure of

power from the property-owning bourgeoisie, or

capitalist class. Industrial capitalism would cause

its own demise.

The Russian Social Democratic Workers’ Party

(RSDWP) originated in 1898 in Minsk. The party’s

central organizer and later source of internal divi-

sion was Vladimir Ilich Lenin (V. I. Ulyanov). The

RSDWP modeled itself after the Socialist Party of

Germany (SPD), whose Marxist orthodoxy was

then challenged by revisionism. Revisionists argued

that reform, not revolution, would best serve

worker interests, and favored elections over strikes.

The RSDWP split into Menshevik (minority)

and Bolshevik (majority) factions in 1903. The

Mensheviks believed that workers should lead the

party and constitute its membership. The Bolshe-

viks, led by Lenin, believed that well-organized pro-

fessional revolutionaries could better organize the

party against the imperial police. Such revolution-

aries would force revolutionary consciousness

upon workers, who might otherwise turn to revi-

sionism and reform.

The RSDWP played a minimal role in the 1905

Russian Revolution. Tsar Nicholas II legalized labor

unions and allowed a new freely elected parliament,

or Duma. But as police cracked down on radical

peasants, workers, and non-Russian nationalities

seeking independence, party members went under-

ground. Many emigrated to Europe. The Menshe-

viks broadened their base among factory workers

inside Russia. The Bolsheviks robbed banks, fled to

Europe, and disagreed over whether or not to par-

ticipate in elections to the bourgeois Duma. The po-

lice succeeded in penetrating the party, arresting

many members (including Josef Stalin) and re-

cruiting police agents. By 1914 the RSDWP was di-

vided and weak, competing for support with rival

liberal (Constitutional Democrat), agrarian social-

ist (Social Revolutionaries), and national (Jewish

Bund) parties.

In February 1917, Imperial Russia collapsed

under the pressures of World War I. A Provisional

Government tried to continue the war and carry

out democratic and agrarian reforms. But the army

began to disintegrate, and the urban and rural

masses, organized in soviets (councils), moved in-

creasingly leftward, seizing factories and land. The

Bolsheviks slowly developed into a mass party.

In April 1917, Lenin returned to Petrograd (St.

Petersburg) from Swiss exile. He immediately de-

clared war on the bourgeois Provisional Govern-

ment. In November, the Bolsheviks seized power in

Petrograd, Moscow, and other towns. Lenin headed

a new socialist government advocating workers

SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC WORKERS PARTY

1412

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY