Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

See also: CATHERINE II; GREAT NORTHERN WAR; PEAS-

ANTRY; PETER I; TAXES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kahan, Arcadius. (1985). The Plow, the Hammer, and the

Knout: An Economic History of Eighteenth-Century Rus-

sia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lyashchenko, Peter I. (1949). History of the National

Economy of Russia to the 1917 Revolution, tr. Leon M.

Herman. New York: Macmillan.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

SOVIET

Soviet (sovet) is the Russian word for “council” or

“advice.”

Its political usage began during the Revolution

of 1905 when it was applied to the councils of

deputies elected by workers in factories throughout

Russia. Although suppressed in 1905, the soviets

reappeared in nearly every possible setting immedi-

ately following the February Revolution of 1917.

With the soviet in Petrograd setting the tone, they

very quickly became the organs of power that the

majority of the population saw as legitimate. Al-

though the moderate socialists who initially led the

soviets were reluctant to take executive power from

the Provisional Government, most Russians seem to

have favored rule by the soviets alone; the Bolshe-

viks’ call for “All Power to the Soviets” may well

have been their most successful slogan. The Octo-

ber Revolution was timed to coincide with the Sec-

ond All-Russian Congress of Soviets, both to

forestall its taking power without Bolshevik initia-

tive and to gain legitimacy from its approval. The

new Bolshevik-led government was thus initially

based on soviets, and the state structure formally

remained so until Mikhail Gorbachev. For most of

the Soviet era, the Supreme Soviet was theoretically

the highest legislative organ, although the Com-

munist Party held practical power. Throughout

their history, soviets generally proved too large for

day-to-day governance, a role filled by a permanent

executive committee elected by the full soviet. Some

scholars have suggested that the soviet became so

popular an institution because it was an urban

counterpart to the village commune assembly, a

governing system with which most Russians, even

in the cities, were familiar.

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION; FEB-

RUARY REVOLUTION; OCTOBER REVOLUTION; PROVI-

SIONAL GOVERNMENT; REVOLUTION OF 1905

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anweiler, Oskar. (1974). The Soviets: The Russian Work-

ers, Peasants, and Soldiers Councils, 1905–1921, tr.

Ruth Hein. New York: Pantheon Books.

D

AVID

P

RETTY

SOVIET-AFGHAN WAR See AFGHANISTAN, RELA-

TIONS WITH.

SOVIET-FINNISH WAR

The Soviet-Finnish War of 1939–1940, which

lasted 103 days and is commonly known as the

“Winter War,” had its origins in the Nazi-Soviet

Pact of August 23, 1939. The secret protocols of

that non-aggression accord divided Eastern Europe

into German and Soviet security zones. Finland,

which had been part of the Russian Empire for more

than a century prior to gaining its independence

during the Russian Revolution, was included by

that agreement within the Soviet sphere. Shortly

after the dismemberment of Poland by Germany

and the USSR, the Soviet government in October

demanded from Finland most of the Karelian Isth-

mus north of Leningrad, a naval base at the mouth

of the Gulf of Finland, and additional land west of

Murmansk along the Barents Sea. The USSR of-

fered other, less strategically important, borderland

as compensation. After Finnish President Kiosti

Kallio rejected the proposal, the Red Army, on No-

vember 30, invaded along the extent of their bor-

der as the Soviet Air Force bombed the Finnish

capital, Helsinki.

Finland’s most formidable defenses were a line

of hundreds of concrete pillboxes, bunkers, and un-

derground shelters, protected by anti-tank obsta-

cles and barbed wire, which stretched across the

Karelian Isthmus. General (and later Field Marshal)

Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, a former tsarist officer,

had organized these defenses, and he commanded

Finland’s armed forces during the war. During the

first two months of conflict, Finland astonished the

rest of the world by defeating the much larger and

more heavily armed Soviet forces, especially along

the Mannerheim Line. In snow—at times five to six

feet deep—with temperatures plunging to -49° F,

SOVIET-FINNISH WAR

1433

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the Finnish defenders were clad in white-padded

uniforms, and some attacked on skis. The Red

Army troops were entirely unprepared for winter

combat. In early February, the USSR enlarged its

forces to 1.2 million men (against a Finnish army

of 200,000) and increased the number of tanks and

aircraft to 1,500 and 3,000, respectively. In March

the Red Army broke through the Mannerheim Line

and advanced toward Helsinki. Finland was com-

pelled to accept peace terms, which were signed in

Moscow on March 12, 1940. The USSR acquired

more territory than it had demanded before the

war, including the entire northern coastline of Lake

Ladoga and parts of southwestern and western Fin-

land. Approximately 420,000 Finns fled from the

25,000 square miles of annexed territories.

Soviet victory, however, came at a very high

cost. Whereas Finland lost about 25,000 killed in

the war, Soviet Commissar of Foreign Affairs Vy-

acheslav Molotov acknowledged that immediately

after the war almost 49,000 Soviet troops had per-

ished. In 1993 declassified Soviet military archives

revealed that 127,000 Soviet combatants had been

killed or gone missing in action. The Red Army

overwhelmed Finnish defenses with massive for-

mations. For example, to take one particular hill,

the USSR attacked its thirty-two Finnish defenders

with four thousand men; more than four hundred

of the Soviet assault troops were killed. Material

losses were similarly lopsided in the war. Alto-

gether, the Soviet Air Force lost about one thou-

sand aircraft; Finland around one hundred.

The world’s attention was focused on the Soviet-

Finnish War, because at that time despite British

and French declarations of war against Germany

in September 1939 over Germany’s invasion of

Poland, there was no other fighting taking place in

Europe. Finland was much admired in the democ-

ratic West for its courageous stand against a much

larger foe, but to Finland’s disappointment, that

admiration did not translate into significant out-

side assistance. By contrast, Soviet aggression was

widely condemned, and the USSR was expelled

from the League of Nations. More importantly, So-

SOVIET-FINNISH WAR

1434

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A Finnish village burns after a February 1940 air raid by Soviet planes. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

viet military weakness was exposed, which served

to embolden Hitler and confirm his belief that Ger-

many could easily defeat the USSR.

Defeated Finland became increasingly worried

when in the summer of 1940 the USSR occupied

Estonia, which lay just forty miles across the Baltic

Sea. Finland found a champion for its defense and

a means to regain the lost territories when Ger-

many attacked the Soviet Union in Operation Bar-

barossa on June 22, 1941. The USSR provided a

convenient pretext for the start of the “Continua-

tion War” (as the resumed hostilities are known in

Finland), when it bombed several Finnish cities, in-

cluding Helsinki, on June 25. While the Red Army

retreated before the Nazi blitz to within three miles

of Leningrad and twenty of Moscow, Finland in-

vaded southward along both sides of Lake Ladoga

down to the 1939 boundary. During the nearly

nine hundred day siege of Leningrad, Finnish forces

sealed off access to the city from the north. Close

to one million Leningraders perished in the ordeal,

primarily from hunger and cold in the winter of

1941–1942. Finland, which relied heavily on Ger-

man imports during the war, rebuffed a Soviet at-

tempt through neutral Sweden in December 1941

to secure a separate peace and relief for Leningrad.

At the same time, the Finnish government refused

German requests to attempt to cross the Svir River

in force to link up with the Wehrmacht along the

southeastern side of Ladoga. The lake remained

Leningrad’s only surface link with the rest of the

USSR during the siege.

Finland’s position in southern Karelia became

increasingly vulnerable as its ally Germany began

to lose the war in the USSR in 1943. In late Feb-

ruary 1944, a month after the Red Army smashed

the German blockade south of Leningrad, the So-

viet Air Force flew hundreds of sorties against

Helsinki and published an ultimatum for peace,

which included, among other things, internment of

German troops in northern Finland and demobi-

lization of the Finnish Army. After Finland refused

the harsh terms, the Red Army launched a massive

offensive north of Leningrad on June 9. In early

August Mannerheim managed to shore up Finnish

defenses near the 1940 border at the same time that

the Finnish parliament appointed him the country’s

president. However, continued German defeats and

Soviet reoccupation of Estonia convinced President

Mannerheim to agree to an armistice on Septem-

ber 19. The agreement restored the 1940 bound-

ary, forced German troops out of Finland, leased to

the USSR territory for a military base a few miles

from Helsinki (which was later returned), and sad-

dled Finland with heavy reparations. Although the

Soviet Union basically controlled Finnish foreign

policy until the Soviet collapse in 1991, of all of

Nazi Germany’s wartime European allies, only Fin-

land avoided Soviet occupation after the war and

preserved its own elected government and market

economy.

See also: FINLAND; FINNS AND KARELIANS; NAZI-SOVIET

PACT OF 1939; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mannerheim, Carl. (1954). Memoirs. New York: Dutton.

Trotter, William R. (1991). A Frozen Hell: The Russo-

Finnish Winter War of 1939–1940. Chapel Hill, NC:

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

R

ICHARD

H. B

IDLACK

SOVIET-GERMAN TRADE

AGREEMENT OF 1939

After declining relations throughout the 1930s and

then a flurry of negotiations in the summer of

1939, Germany (represented by Karl Schnurre) and

the Soviet Union (represented by Yevgeny Babarin)

signed a major economic agreement in Berlin in the

early morning hours of August 20. The treaty

called for 200 million Reichsmark in new orders

and 240 million Reichsmark in new and current

exports from both sides over the next two years.

This agreement served two purposes. First, it

brought two complementary economies closer to-

gether. To support its war economy, Germany

needed raw materials—oil, manganese, grains, and

wood. The Soviet Union needed manufactured

products—machines, tools, optical equipment, and

weapons. Although the USSR had slightly more

room to maneuver and a somewhat superior bar-

gaining position, neither country had many options

for receiving such materials elsewhere. Subsequent

economic agreements in 1940 and 1941, therefore,

focused on the same types of items.

Second, the economic negotiations provided a

venue for these otherwise hostile powers to discuss

political and military issues. Hitler and Stalin sig-

naled each other throughout 1939 by means of

these economic talks. Not surprisingly, therefore,

the Nazi-Soviet Pact was signed a mere four days

after the economic agreement.

SOVIET-GERMAN TRADE AGREEMENT OF 1939

1435

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Because raw materials took less time to pro-

duce, Soviet shipments initially outpaced German

exports and provided an important prop to the

German war economy in late 1940 and 1941. Be-

fore the Germans could fully live up to their end

of the bargain, Hitler invaded.

See also: FOREIGN TRADE; GERMANY, RELATIONS WITH;

NAZI-SOVIET PACT OF 1939; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ericson, Edward E. (1999). Feeding the German Eagle: So-

viet Economic Aid to Nazi Germany, 1933–1941. West-

port, CT: Praeger.

E

DWARD

E. E

RICSON

III

SOVIET MAN

For many years, the term novy sovetsky chelovek in

Soviet Marxism-Leninism was usually translated

into English as “the new Soviet man.” A transla-

tion that would be more faithful to the meaning

of the original Russian would be “the new Soviet

person,” because the word chelovek is completely

neutral with regard to gender.

The hope of remaking the values of each mem-

ber of society was implicit in Karl Marx’s expecta-

tions for the progression of society from capitalism

through proletarian revolution to communism.

Marx reasoned that fundamental economic and so-

cial restructuring would generate radical attitudi-

nal change, but Vladimir Lenin and Josef Stalin

insisted that the political regime had to play an ac-

tive role in the transformation of people’s values,

even in a socialist society. It remained for the Pro-

gram of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union,

adopted at the party’s Twenty-Second Congress in

1961 in accordance with the demands of Nikita

Khrushchev, to spell out the “moral code of the

builder of communism,” which subsequently was

elaborated at length by a wide variety of publica-

tions. The builder of communism was expected to

be educated, hard working, collectivistic, patriotic,

and unfailingly loyal to the Communist Party of

the Soviet Union. During the transition to a fully

communist society, as predicted by Khrushchev,

such vestiges of past culture as religion, corrup-

tion, and drunkenness would be eradicated. The

thinking associated with the Party Program of

1961 represented the last burst of revolutionary

optimism in the Soviet Union.

Over time, it became increasingly difficult to

ascribe “deviations from socialist morality” to the

influence of pre-1917 or pre-1936 social struc-

tures. Indeed, testimony from a variety of sources

suggested that reliance on connections, exchanges

of favors, and bribery (which had by no means dis-

appeared in the Stalin years) were steadily grow-

ing in importance during the post-Stalin decades.

In the mid-1970s Hedrick Smith’s book The Rus-

sians described the members of the largest nation-

ality in the USSR as impulsive, generous, mystical,

emotional, and essentially irrational, behind the fa-

cade of a monochromatic ideology imposed by an

authoritarian political regime. Though the Brezh-

nev leadership still insisted that the socialist way

of life (sotsialistichesky obraz zhizni) in the Soviet

Union was morally superior to that in the West

with its unbridled individualism and moral decay,

the sense of optimism concerning the future was

slipping away. Ideologists complained ever more

about amoral behavior by citizens, and the politi-

cal leaders seemed to become more tolerant of ille-

gal economic activity and corruption. Despite those

general trends, problematic as they were, some So-

viet citizens did strive actively to serve their fellow

human beings, including the most vulnerable

members of society.

See also: KRUSCHEV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH; LENIN, VLADI-

MIR ILLICH; MARXISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DeGeorge, Richard T. (1969). Soviet Ethics and Morality.

Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Evans, Alfred B., Jr. (1993). Soviet Marxism-Leninism: The

Decline of an Ideology. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Mehnert, Klaus. (1962). Soviet Man and His World, tr.

Maurice Rosenbaum. New York: Praeger.

Smith, Hedrick. (1983). The Russians, updated edition.

New York: Times Books.

A

LFRED

B. E

VANS

J

R

.

SOVIET-POLISH WAR

The Soviet-Polish War was the most important of

the armed conflicts among the East European states

emerging from World War I. The Versailles settle-

ments failed to delineate Poland’s eastern border.

The Entente powers hoped that the Bolshevik Rev-

olution was temporary, and that a Polish-Russian

SOVIET MAN

1436

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

border would be established after the victory of

White Russian forces. As the eastern command of

the German Army withdrew after the armistice of

November 11, 1918, Vladimir Lenin in Moscow

and Józef Pilsudski in Warsaw planned to fill the

vacuum. Lenin hoped to export revolution, Pilsud-

ski to lead an East European federation.

In early 1919, Lenin’s main concern was the

White Russian forces of Anton Denikin. Pilsudski

did not support Denikin, a Russian nationalist who

treated eastern Galicia as part of a future Russian

state. In late 1918, Pilsudski watched as the Red

Army moved on Vilnius and Minsk. Pilsudski’s of-

fensive began in April 1919, his forces taking Vil-

nius on April 21 and Minsk on August 8. In

collaboration with Latvian troops, Poland took

Daugavpils on January 3, 1920, returning the city

to Latvia. By then Denikin was in retreat, and the

Red Army could turn to an offensive against the

remnants of independent Ukrainian forces.

The Ukrainian National Republic of Symon

Petliura allied with Poland in April 1920. With

Ukrainian help, Pilsudski took Kiev on May 7,

1920, only to find his troops overwhelmed by

the forces of Soviet commanders Mikhail Tukha-

chevsky and Semen Budenny. On July 11 Great

Britain proposed an armistice based upon the

Curzon Line, which left Ukraine and Belarus to

Moscow. These terms displeased Pilsudski, but Pol-

ish prime minister Stanislaw Grabski had agreed to

similar ones in negotiations with British prime

minister David Lloyd George. Moscow’s replies

questioned the future of independent Poland, and

the Red Army encircled Warsaw in August.

With the exception of its Ukrainian ally, Poland

faced this attack alone. The French sent a military

legation, but its counsel was unheeded. Pilsudski

himself planned and executed a daring counterat-

tack against the Bolshevik center, shattering

Tukhachevsky’s command. He then drove the Red

Army to central Belarus. The Battle of Warsaw of

August 16–25, 1920, was called by D’Abernon “the

eighteenth decisive battle of the world.” It set the

westward boundary of the Bolshevik Revolution,

saved independent Poland, and ended Lenin’s hopes

of spreading the Bolshevik Revolution by force of

arms to Germany.

The Soviet-Polish frontier, agreed at Riga on

March 18, 1921, was itself consequential. Poland

abandoned its Ukrainian ally, as most of Ukraine

was still under Soviet control. Yet the war forced

the Soviets to reconsider nationality questions, and

led to the establishment of the Soviet Union as a

nominal federation in December 1922. During the

1930s, Josef Stalin blamed Polish agents for short-

falls in Ukrainian food production, and he ethni-

cally cleansed Poles from the Soviet west. These

preoccupations flowed from earlier defeat.

Riga divided Belarus and Ukraine between Poland

and the Soviet Union. The Red Army seized west-

ern Belarus and western Ukraine from Poland in

September 1939 thanks to the Molotov-Ribbentrop

Treaty, undoing the consequences of Riga and

encouraging forgetfulness of the Polish-Bolshevik

War. Yet more than any other event, the Polish-

Bolshevik War defined the political and intellectual

frontiers of the interwar period in eastern Europe.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; POLAND; WORLD

WAR I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

D’Abernon, Edgar Vincent. (1931). The Eighteenth Decisive

Battle of the World. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Davies, Norman. (1972). White Eagle, Red Star. New

York: St. Martin’s.

Gervais, Céline, ed. (1975). La Guerre polono-soviétique,

1919–1920. Lausanne: L’Age de l’Homme.

Palij, Michael (1995). The Ukrainian-Polish Defensive Al-

liance. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Institute of Ukrain-

ian Studies.

Ullman, Richard H. (1972). The Anglo-Soviet Accord.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wandycz, Piotr. (1969). Soviet-Polish Relations, 1917–1921.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

T

IMOTHY

S

NYDER

SOVKHOZ

The sovkhoz, or state farm, the collective farm

(kolkhoz), and the private subsidiary sector, were the

three major organizational forms used in Soviet agri-

cultural production after the collectivization of So-

viet agriculture, a process begun by Josef Stalin in

1929. Although the concept of the state farm origi-

nated earlier under Vladimir Lenin during the period

of war communism, the serious development of state

farms began during the 1930s as the Soviet state

exercised full control over the agricultural sector.

The state farm might be described as a factory in

the field in the sense that it was full state property,

SOVKHOZ

1437

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

financed by state budget (revenues flowed into and

expenses were paid by the state budget), and sub-

ject to the state planning system, and workers

(rabochy) on state farms were paid a contractual

wage. All of these major characteristics of the state

farm distinguished it from the collective farm.

The sovkhoz was organized in a fashion simi-

lar to an industrial enterprise. The farm was headed

by a state-appointed director, and the connection

between labor force and sovkhoz resembled the

structure of the industrial enterprise. Most impor-

tant, capital investment for the sovkhoz was

funded by the state budget. Thus, although prices

paid by the state for sovkhoz produce were lower

than for compulsory deliveries from collective

farms, state farms were in a financially much bet-

ter position. This was a major reason for the sub-

sequent conversion of weak collective farms into

state farms in the post–World War II years, a

process enhanced by the Soviet policy of agro-

industrial integration and the ultimate development

of the agroindustrial complex comprising collective

and state farms and industrial processing capacity.

The role of state farms in Soviet agriculture

grew steadily during the Soviet era. The number of

state farms grew from less than 1,500 in 1929 to

just over 23,000 by the end of the Gorbachev era

in the late 1980s. This expansion resulted partly

from state policy—the amalgamation and conver-

sion of collective farms to state farms—and partly

from the use of state farms in special programs ex-

panding the area under cultivation, such as the Vir-

gin Lands Program. State farms were large. During

the 1930s, for example, state farms were on aver-

age roughly 6,000 acres of sown area. By the

1980s, they averaged more than 11,000 acres of

sown area per farm.

There were considerable differences in the out-

put patterns between collective and state farms, and

state farms were viewed as more productive and

more profitable than collective farms. Generally

speaking, the role of the state farms increased over

time from modest proportions in the early 1930s.

The sovkhoz came to be important in the produc-

tion of grain, vegetables and eggs, less important

for meat products. During the transition era of the

1990s, state farms were reorganized using joint

stock arrangements, although the development of

land markets remained constrained by opposition

to private ownership of land.

See also: AGRICULTURE; COLLECTIVE FARM; COLLECTIVI-

ZATION OF AGRICULTURE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Davies, R. W.; Harrison, Mark; and Wheatcroft, S. G.,

eds. (1994). The Economic Transformation of the Soviet

Union, 1913–1945. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (2001). Russian

and Soviet Economic Performance and Structure, 7th ed.

New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Volin, Lazar. (1970). A Century of Russian Agriculture.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

R

OBERT

C. S

TUART

SOVNARKHOZY

Regional bodies that administered industry and

construction in the USSR.

The Sovnarkhozy (acronym for Sovety Narod-

nogo Khozyaistva, or Councils of the National

Economy) were state bodies for the regional ad-

ministration of industry and construction in Rus-

sia and the USSR that existed from 1917 to 1932

and again from1957 to 1965.

The first Sovnarkhozy were created in Decem-

ber 1917 by the Supreme Council of the National

Economy. Each of them had power over areas rang-

ing in size from small districts up to several

provinces. They were associated with local institu-

tions such as soviets and were responsible to the

Supreme Council for restoring the economy of their

area after World War I and then the civil war. As

the Soviet economy developed during the 1920s,

control of industry was divided between the

Supreme Council of the National Economy (which

retained control of important strategic industries)

and the Sovnarkhozy. The Sovnarkhozy were abol-

ished in 1932 when the Supreme Council was di-

vided into three separate industrial commissariats.

Sovnarkhozy were reintroduced during Nikita

Khrushchev’s 1957 effort to decentralize the econ-

omy. The USSR was divided into 105 Sovnarkhozy

responsible to republican Councils of Ministers for

the industry in the regions, except armaments,

chemicals, and electricity, which at first remained

under central control. The system had a funda-

mental weakness due to the lack of centralized di-

rection and coordination, and Sovnarkhozy often

pursued local interests and considered only the

needs of their own region. In 1962 and 1963 at-

tempts were made to reform the system, such as

amalgamating the Sovnarkhozy and reviving the

SOVNARKHOZY

1438

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Supreme Council of the National Economy, but in

1965 Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin abolished

the Sovnarkhozy and reestablished the central in-

dustrial ministries.

See also: ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; KOSYGIN RE-

FORMS; REGIONALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nove, Alec. (1982). An Economic History of the U.S.S.R.

Basingstoke, UK: Penguin.

Prokhorev, Aleksandr M., ed. (1975). Great Soviet Ency-

clopedia: A Translation of the Third Edition. New York:

Macmillan.

D

EREK

W

ATSON

SOVNARKOM

Acronym for Sovet Narodnykh Komissarov (Coun-

cil of People’s Commissars), the government of the

early Soviet republic.

Sovnarkom was formed by Vladimir Lenin in

October 1917 as the government of the new revo-

lutionary regime. The word commissars was used

to distinguish the new institution from bourgeois

governments and indicate that administration was

being entrusted to commissions (commissariats),

not to individuals. Initially membership included

Lenin (chairperson), eleven departmental heads

(commissars), and a committee of three responsi-

ble for military and naval affairs. Until 1921, un-

der Lenin, Sovnarkom was the real government of

the new Soviet republic—the key political as well

as administrative body—but after 1921 political

power passed increasingly to Party bodies.

With the creation of the USSR in 1924, Lenin’s

Sovnarkom became a union (national) body. Alexei

Rykov was chairperson of the Union Sovnarkom

from 1924 to 1930, then Vyacheslav Molotov from

1930 to 1941, and Josef Stalin from 1941 to 1946,

when the body was renamed the Council of Min-

isters. There were two types of commissariats: six

unified (renamed “union-republican” under the

1936 constitution), which functioned through par-

allel apparatuses in identically named republican

commissariats, and five all-union with plenipoten-

tiaries in the republics directly subordinate to their

commissar.

In 1930 Gosplan was upgraded to a standing

commission of Sovnarkom and its chairperson

given membership. By 1936 the number of com-

missariats had risen to twenty-three, and by 1941

to forty-three. A major trend was the replacement

of an overall industrial commissariat by industry-

specific bodies.

The 1936 constitution granted Sovnarkom

membership to chairpersons of certain state com-

mittees. It also formally recognized Sovnarkom as

the government of the USSR, but deprived it of its

legislative powers. By this time the institution was

and remained a high-level administrative commit-

tee specializing in economic affairs.

See also: COMMISSAR; COUNCIL OF MINISTERS, SOVIET;

LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; MOLOTOV, VYACHESLAV

MIKHAILOVICH; RYKOV, ALEXEI IVANOVICH; STALIN,

JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Rigby, Thomas Henry. (1979). Lenin’s Government: Sov-

narkom, 1917–1922. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Watson, Derek. (1996). Molotov and Soviet Government: Sov-

narkom, 1930-41. Basingstoke, UK: CREES-Macmillan.

D

EREK

W

ATSON

SOYUZ FACTION

The Soyuz faction was a group of hardliners in

USSR Congress of People’s Deputies at the end of

the Soviet era. Its leaders, Viktor Alksnis and Niko-

lai Petrushenko, had been elected as deputies from

Latvia and Kazakhstan respectively, regions with

large ethnic Russian populations that conservatives

were trying to mobilize (in organizations called “in-

terfronts”) to counter the independence movements

that had sprung up under perestroika. While na-

tionalists and communists dominated the USSR

Congress of People’s Deputies elected in March

1989, democratic forces won the upper hand in the

Russian Federation Congress of People’s Deputies,

elected in the spring of 1990, which chose Boris

Yeltsin as its leader.

Alksinis came up with the idea of the Soyuz

faction in October 1989. It was launched on Feb-

ruary 14, 1990, but only became highly visible to-

ward the end of the year, when conservatives

mobilized to deter Soviet President Mikhail Gor-

bachev from adopting the Five-Hundred Day eco-

nomic reform program. Soyuz had close ties to the

SOYUZ FACTION

1439

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

army and security services, and its goal was to pre-

serve the USSR. At its formal founding congress on

December 1, 1990, Soyuz claimed the support of

up to one quarter of the deputies in the USSR Con-

gress. Its sister organization in the Russian Feder-

ation Supreme Soviet was Sergei Baburin’s Rossiya

faction. Soyuz put increasing pressure on Gor-

bachev to end democratization by introducing pres-

idential rule, suppressing disloyal political parties,

and cracking down on nationalist movements in

the non-Russian republics. It reportedly persuaded

Gorbachev to fire Soviet Interior Minister Vadim

Bakatin, who had agreed to the creation of sepa-

rate interior ministries in each of the union re-

publics. On November 11, 1990, Alksnis persuaded

Gorbachev to address a meeting of one thousand

military personnel elected as deputies to various so-

viets; he got a hostile reception. A week later, speak-

ing in the USSR Supreme Soviet on November 17,

Alksinis effectively called for Gorbachev’s over-

throw. Still, no one could be sure whether Gor-

bachev would stick with democratization or opt for

an authoritarian crackdown.

In January 1991 KGB teams tried to overthrow

the independent-minded governments in Latvia and

Lithuania. This drew fierce international criticism,

and Gorbachev disowned it. Apparently he had

given up the idea of using force to hold the USSR

together, for he now began pursuing a new union

treaty with the heads of the republics that made

up the USSR. In response, a Soyuz conference in

April 1991 called for power to be transferred from

Gorbachev to Prime Minister Valentin Pavlov or

Anatoly Lukyanov, chairman of the USSR Supreme

Soviet. Clearly the Soyuz group was laying the po-

litical and organizational groundwork for the coup

attempt of August 1991, but the failure of the

putsch sealed the fate of the USSR and of Soyuz,

its most loyal defender. Alksnis was later one of

the defenders of the anti-Yeltsin parliament in the

violent confrontation of October 1993. Interviewed

in 2002, he insisted that the USSR could have been

saved if Gorbachev had acted more resolutely and

not been “afraid of his own shadow.”

See also: AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH; DEMOCRATIZATION;

GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dunlop, John B. (1995). The Rise of Russia and the Fall

of the Soviet Empire. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Uni-

versity Press.

Rees, E. A. (1992). “Party Relations with the Military and

the KGB.” In The Soviet Communist Party in Disarray:

The XXVIII Congress of the Communist Party of the So-

viet Union, ed. E. A. Rees. New York: St. Martin’s.

Teague, Elizabeth. (1991). “The ‘Soyuz’ Group.” Report

on the USSR 3(20):16–21.

P

ETER

R

UTLAND

SPACE PROGRAM

The Russian space program has a long history. The

first person in any country to study the use of

rockets for space flight was the Russian school-

teacher and mathematician Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

His work greatly influenced later space and rocket

research in the Soviet Union, where, as early as

1921, the government founded a military facility

devoted to rocket research. During the 1930s,

Sergei Korolev emerged as a leader in this effort and

eventually became the “chief designer” responsible

for many of the early Soviet successes in space in

the 1950s and 1960s.

Under Korolev’s direction, the Soviet Union in

the 1950s developed an intercontinental ballistic

missile (ICBM), with engines designed by Valentin

Glushko, which was capable of delivering a heavy

nuclear warhead to American targets. That ICBM,

called the R-7 or Semyorka (“Number 7”), was first

successfully tested on August 21, 1957. Its success

cleared the way for the rocket’s use to launch a

satellite.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union

had announced their intent to launch an earth

satellite in 1957 during the International Geophys-

ical Year (IGY). Fearing that delayed completion of

the elaborate scientific satellite, intended as the So-

viet IGY contribution, would allow the United

States to be first into space, Korolev and his asso-

ciates designed a much simpler spherical spacecraft.

After the success of the R-7 in August, that satel-

lite was rushed into production and became Sput-

nik 1, the first object put into orbit, on October 4,

1957. A second, larger satellite carrying scientific

instruments and the dog Laika, the first living crea-

ture in orbit, was launched November 3, 1957.

Three Soviet missions, Luna 1–3, explored the

vicinity of the moon in 1959, sending back the first

images of its far side. Luna 1 was the first space-

craft to fly past the moon; Luna 2, in making a

hard landing on the lunar suface, was the first

spacecraft to strike another celestial object.

Soon after the success of the first Sputniks, Ko-

rolev began work on an orbital spacecraft that

SPACE PROGRAM

1440

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

SPACE PROGRAM

1441

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

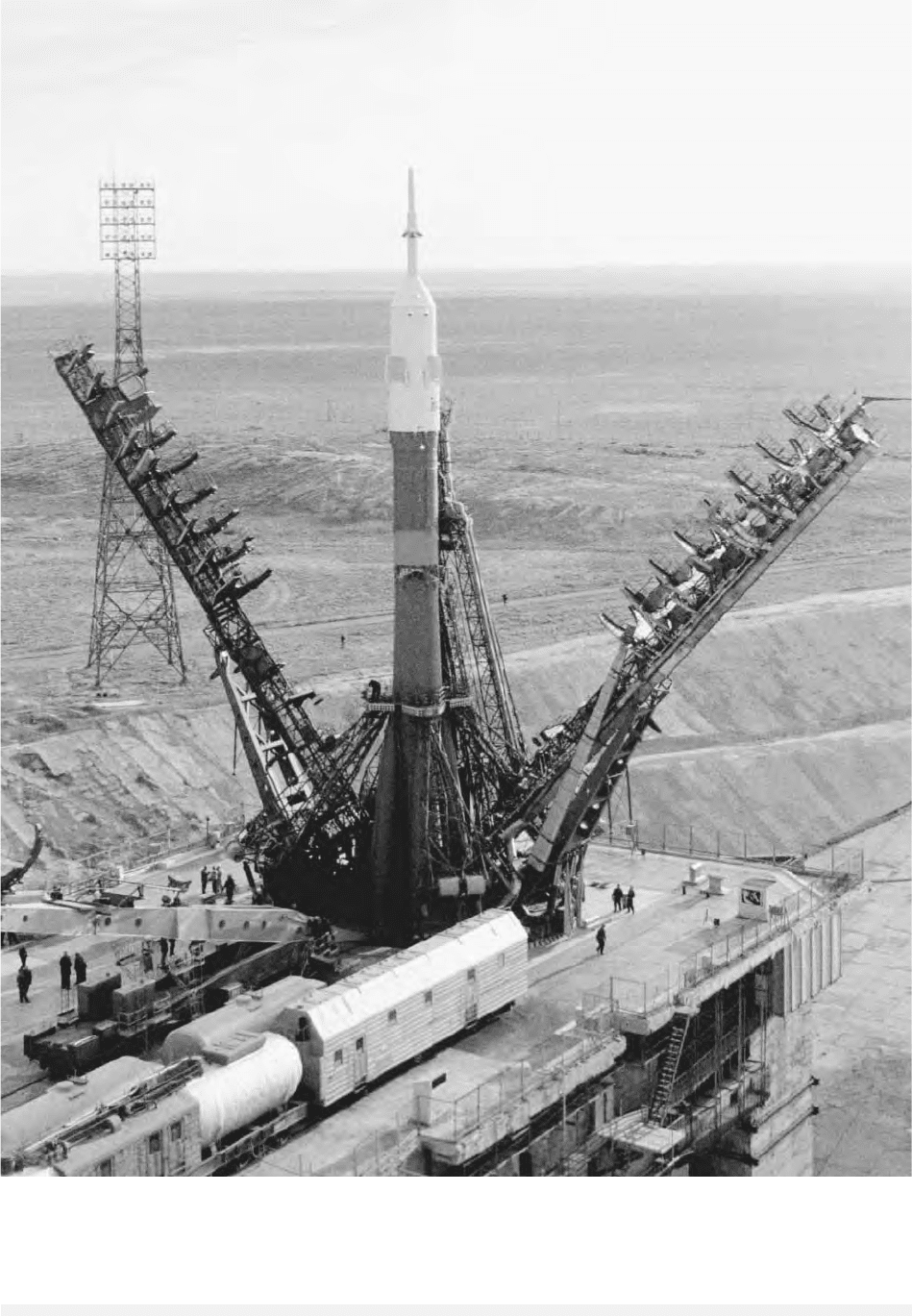

A Soyuz-TM rocket sitting on its launch pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on April 2, 2000. © R

EUTERS

N

EW

M

EDIA

I

NC

./CORBIS. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

could be used both to conduct reconnaissance mis-

sions and to serve as a vehicle for the first human

space flight missions. The spacecraft was called

Vostok when it was used to carry a human into

space. The first human was lifted into space in Vos-

tok 1 atop a modified R-7 rocket on April 12, 1961,

from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

The passenger, Yuri Gagarin, was a twenty-seven-

year-old Russian test pilot.

There were five additional one-person Vostok

missions. In August 1961, Gherman Titov at age

twenty-five (still the youngest person ever to fly

in space) completed seventeen orbits of Earth in

Vostok 2. He became ill during the flight, an inci-

dent that caused a one-year delay while Soviet

physicians investigated the possibility that humans

could not survive for extended times in space. In

August 1962, two Vostoks, 3 and 4, were orbited

at the same time and came within four miles of

one another. This dual mission was repeated in

June 1963; aboard the Vostok 6 spacecraft was

Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman to fly in

space.

As U.S. plans for missions carrying more than

one astronaut became known, the Soviet Union

worked to maintain its lead in the space race by

modifying the Vostok spacecraft to carry as many

as three persons. The redesigned spacecraft was

known as Voskhod. There were two Voskhod mis-

sions. On the second mission in March 1965, cos-

monaut Alexei Leonov became the first human to

carry out a spacewalk.

Korolev began work in 1962 on a second-

generation spacecraft, called Soyuz, holding as

many as three people in an orbital crew compart-

ment, with a separate module for reentry back to

Earth. The first launch of Soyuz, with a single cos-

monaut, Vladimir Komarov, aboard, took place on

April 23, 1967. The spacecraft suffered a number

of problems, and Komarov became the first person

to perish during a space flight. The accident dealt

a major blow to Soviet hopes of orbiting or land-

ing on the moon before the United States.

After the problems with the Soyuz design were

remedied, various models of the spacecraft served

the Soviet, and then Russian, program of human

space flight for more than thirty years. At the start

of the twenty-first century, an updated version of

Soyuz was being used as the crew rescue vehicle—

the lifeboat—for the early phase of construction

and occupancy of the International Space Station.

While committing the United States in 1961 to

winning the moon race, President John F. Kennedy

also made several attempts to convince the Soviet

leadership that a cooperative lunar landing pro-

gram would be a better alternative. But no positive

reply came from the Soviet Union, which contin-

ued to debate the wisdom of undertaking a lunar

program. Meanwhile, separate design bureaus

headed by Korolev and Vladimir Chelomei com-

peted fiercely for a lunar mission assignment. In

August 1964, Korolev received the lunar landing

assignment. The very large rocket that Korolev de-

signed for the lunar landing effort was called the

N1.

Indecision, inefficiencies, inadequate budgets,

and personal and organizational rivalries in the So-

viet system posed major obstacles to success in the

race to the moon. To this was added the unexpected

death of the charismatic leader and organizer Ko-

rolev, at age fifty-nine, on January 14, 1966.

The Soviet lunar landing program went for-

ward fitfully after 1964. The missions were in-

tended to employ the N1 launch vehicle and a

variation of the Soyuz spacecraft, designated L3,

that included a lunar landing module designed for

one cosmonaut. Although an L3 spacecraft was

constructed, the N1 rocket was never successfully

launched. After four failed attempts between 1969

and 1972, the N1 program was cancelled in May

1974, thus ending Soviet hopes for human mis-

sions to the moon. On July 20, 1969, U.S. astro-

naut Neil Armstrong stepped from Apollo II Lunar

Module onto the surface of the moon.

By 1969, the USSR began to shift its emphasis

in human space flight to the development of Earth-

orbiting stations in which cosmonaut crews could

carry out observations and experiments on mis-

sions that lasted weeks or months. The first Soviet

space station, called Salyut 1, was launched April

19, 1971. Its initial crew spent twenty-three days

aboard the station carrying out scientific studies

but perished when their Soyuz spacecraft depres-

surized during reentry. The Soviet Union success-

fully orbited five more Salyut stations through the

mid-1980s. Two of these stations had a military

reconnaissance mission, and three were devoted to

scientific studies. The Soviet Union also launched

guest cosmonauts from allied countries for short

stays aboard Salyuts 6 and 7.

The Soviet Union followed its Salyut station se-

ries with the February 20, 1986, launch of the Mir

space station. In 1994–1995, Valery Polyakov spent

438 continuous days aboard the station. More than

one hundred people from twelve countries visited

SPACE PROGRAM

1442

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY