Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

vention and provoked opposition among the troops

there and at home.

The opening of a Second Russian Front in

Siberia was rather different, since it involved a more

substantial American expeditionary force (around

9,000) under its own command and a much larger

Japanese army of approximately 70,000, along

with 4,000 Canadians and token “colonial” units

of French, Italian, Chinese, and British. Their ill-

defined mission was to assist the transfer to the

Western Front of a Czecho-Slovak Legion consist-

ing of 60,000 former prisoners-of-war who sup-

ported the Allies, to protect munitions in and

around Vladivostok, and to guard against one an-

other’s imperialist ambitions. On the long way to

the Western Front, the Czech Legion managed to

seize most of the Trans-Siberian Railroad to pre-

vent released German and Austro-Hungarian pris-

oners-of-war in the area from forming a “German

front” in Siberia; and to provide aid to what at first

seemed a viable anti-Bolshevik government cen-

tered in Omsk under the leadership of Admiral

Alexander Kolchak. For the United States, limiting

Japanese ambitions for a more permanent occupa-

tion was a major factor. In any event, the Ameri-

can commander, General William S. Graves, was

under strict orders from Washington not only to

avoid coming under the control of the larger Japan-

ese army, but also to desist from direct hostility

with any Russian military units, of which there

were several of various political orientations. Most

of the Allied expeditionary force remained in the

vicinity of Vladivostok and at a few points along

the Chinese Eastern and Trans-Siberian railroads

until the decision to withdraw in May–June 1919.

Another commitment of men, supplies, and fi-

nancial assistance came to the south of Russia but

only late in 1918, when the end of war allowed

passage through the Straits into the Black Sea. The

catalyst here was the existence of substantial White

armies under Anton Denikin and his successor,

General Peter Wrangel. In the spring and summer

campaigns of 1919, these forces won control of ex-

tensive territory from the Bolsheviks with the sup-

port of about 60,000 French troops (mostly

Senegalese and Algerians), smaller detachments of

British soldiers with naval support, and an Amer-

ican destroyer squadron on the Black Sea. Divided

command, low morale, vague political objectives,

the skill and superiority of the Red Army, and, fi-

nally, Allied reluctance to provide major aid

doomed their efforts. This “crusade” came to a dis-

mal end in late 1920. Besides a direct but limited

military presence in Russia, the interventionist

powers provided financing, a misleading sense of

permanent political and economic commitment to

the White opposition, but also medical and food re-

lief for large areas of the former Russian Empire.

Allied intervention in Russia was doomed from

the beginning by the small forces committed, their

unclear mission and divided command, the low

morale of the Allied soldiers and their Russian

clients, the end of the war of which it was a part,

and the superiority of Soviet military forces and

management. Throughout, it seemed to many that

the Allied interventionists were on the wrong side,

defending those who wanted either to restore the

old order or break up Russia into dependent states.

To many Americans, for instance, the Japanese

posed more of a threat to Siberia than did the Bol-

sheviks. In the aftermath, genuinely anti-Bolshevik

Russians felt betrayed by the failure of the Allies to

destroy their enemy, while the new Soviet power

was born with an ingrained sense of hostility to

the interventionist states, marking what could be

claimed as the beginnings of the Cold War. An im-

mediate tragedy was the exodus of desperate

refuges from the former Russian Empire through

the Black Sea and into Manchuria and China, seek-

ing assistance from erstwhile allies who had failed

to save the world for democracy.

See also: BREST-LITOVSK PEACE; SIBERIA; UNITED STATES,

RELATIONS WITH; WHITE ARMY; WORLD WAR I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carley, Michael J. (1983). Revolution and Intervention: The

French Government and the Russian Civil War,

1917–1919. Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University

Press.

Foglesong, David S. (1995). America’s Secret War Against

Bolshevism: U. S. Intervention in the Russian Civil War,

1917–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Car-

olina Press.

Goldhurst, Richard. (1978). The Midnight War: The Amer-

ican Intervention in Russia, 1918–1920. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Graves, William S. (1932). America’s Siberian Adventure,

1918–1920. New York: Jonathan Cape & Harrison

Smith.

Kennan, George F. (1958). The Decision to Intervene: The

Prelude to Allied Intervention in the Bolshevik Revolu-

tion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Saul, Norman E. (2001). War and Revolution: The United

States and Russia, 1914–1921. Lawrence: University

Press of Kansas.

ALLIED INTERVENTION

53

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Ullman, Richard H. (1961–73). Anglo-Soviet Relations,

1917–1921. 3 vols. Princeton. NJ: Princeton Uni-

versity Press.

Unterberger, Betty. (1956). America’s Siberian Expedition,

1918–1920. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Unterberger, Betty, ed. (2002). The United States and the

Russian Civil War: The Betty Miller Unterberger Collec-

tion of Documents. Washington, DC: Scholarly Re-

sources.

N

ORMAN

E. S

AUL

ALLILUYEVA, SVETLANA IOSIFOVNA

(b. 1926), daughter of Soviet general secretary Josef

Stalin and his second wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva.

The daughter of an old Georgian revolutionary

friend, Sergo Alliluyev, Nadezhda Alliuyeva was

sixteen when Stalin married her on March 24,

1919. In addition to Svetlana Iosifovna, she had one

son in 1919, Vasily. Svetlana also had an older

half-brother Yakov (Jacob), the son of Stalin’s first

wife, Yekaterina Svanidze, a simple peasant girl,

whom he married in June 1904 at the age of 25,

but who died on April 10, 1907.

Nadezhda Alliluyeva’s death in 1932, appar-

ently a suicide following a quarrel with Stalin,

deeply affected both her husband and her daugh-

ter. Morose, Stalin withdrew from Party comrades

with whom he had socialized with his wife. Some

believe her suicide contributed to his paranoid dis-

trust of others.

Svetlana was twenty-seven when Georgy

Malenkov summoned her to Blizhny, the nickname

for Stalin’s dacha at Kuntsevo, just outside of

Moscow. In her first book, Twenty Letters to a Friend

(1967), she poignantly described Stalin’s three-day

death from a brain hemorrhage. “The last hours

were nothing but a slow strangulation. The death

agony was horrible. He literally choked to death as

we watched.” Although she had lived apart from

Stalin, who had always been “very remote” from

her, she nevertheless experienced a “welling up of

strong, contradictory emotions” and a “release

from a burden that had been weighing on [her]

heart and mind.” After her father’s death, Svetlana

taught and translated texts in the Soviet Union. In

late 1966, while in India to deposit the ashes of her

late husband Brajesh Singh, she asked Ambassador

Chester Bowles in the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi,

India, for permission to defect to the United States.

She left a grown son (Josef) and daughter (Katie)

from two earlier marriages in the Soviet Union.

Svetlana’s defection caused an international sensa-

tion. “I could not continue the same useless life

which I had for fourteen years,” she told reporters

on March 9, 1967. Settling in Locust Valley, New

York, she wrote the abovementioned memoir de-

scribing the deaths of her two parents, and a sec-

ond one two years later (Only One Year), in which

she described her decision to defect. Upon becom-

ing a U.S. citizen, she married an American archi-

tect, William Peters, in 1970 and had a daughter

by him. After separating from Peters, she returned

to the Soviet Union in 1984 and settled in Tbilisi.

She again left the USSR in 1986 and returned to

the United States, but then settled in England dur-

ing the 1990s.

See also: STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alliluyeva, Anna Sergeevna, and Alliluyev, Sergei

Yakovlich. (1968). The Alliluyev Memoirs: Recollec-

tions of Svetlana Stalina’s Maternal Aunt Anna

Alliluyeva and her Grandfather Sergei Alliluyev, comp.

David Tutaev. New York: Putnam.

Clements, Barbara E. (1994). Daughters of Revolution: A

History of Women in the USSR. Arlington Heights, IL:

Harlan Davidson.

Radzinskii, Edvard. (1996). Stalin: The First In-Depth Bi-

ography Based on Explosive New Documents from Rus-

sia’s Secret Archives. New York: Doubleday.

Richardson, Rosamond. (1994). Stalin’s Shadow: Inside

the Family of One of the Greatest Tyrants. New York:

St. Martin’s.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

ALMANAC See FEMINISM.

ALTAI

The Altai people comprise an amalgamation of Tur-

kic tribes who reside in the Altai Mountains and

the Kuznetsk Alatau. Their origins lie with the ear-

liest Turkic tribes (Uighurs, Kypchak-Kimaks,

Yenisey Kyrgyz, Oguz, and others). In 550

C

.

E

., the

Tugyu Turks settled in the Altai Mountains along

the headwaters of the Ob River and in the foothills

of the Kuznetsk Alatau, where around 900

C

.

E

. they

formed the Kimak Tribal Union with the Kypchak

ALLILUYEVA, SVETLANA IOSIFOVNA

54

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Turks. From this union sprang the ethnonyms

Kumanda, Teleut, and Telengit.

In the seventh century, the Telengit lived with

another would-be Altai tribe, the Telesy, on the

Tunlo River in Mongolia, whence they both mi-

grated to Tyva. By the eighth century they had

gravitated to the Altai Mountains and eastern Ka-

zakhstan. The Russians arrived in the 1700s and

proceeded to sedentarize many of the nomadic Al-

tai. The Soviet government gave the Altai nominal

recognition with the establishment of the Gorno-

Altai (Oirot) Autonomous Oblast in 1922. In 1991

it became the Altai Republic.

In 1989 there were 70,800 Altai worldwide,

69,400 in Russia alone, and 59,100 in the Altai Re-

public. A few lived in Central Asia. The internal

divisions among the Altai are distinguished ethno-

graphically and dialectically. The northern group

comprises the Tubulars who live on the left-bank

of the Biya River and on the shores of Lake Telet-

skoye, the Chelkans who live along the Lebed River,

and the Kumandas who live along the middle course

of the Biya. Each of these tribes speaks an Altai di-

alect that belongs to the Eastern division of the

Ural-Altaic language family. The southern groups,

including the Altai-Kizhi, Telengits, Telesy, and

Teleuts, live in the Katun River Basin and speak an

Altai dialect closely related to the Kyrgyz language.

Although the ethnogenesis of the southern

Altai took place among the Oirot Mongols, con-

solidation of the northern groups and overall con-

solidation between the northern and southern Altai

has been difficult. The Teleuts, for example, have

long considered themselves distinctive and have

sought separate recognition. In 1868 the Altai

Church Mission tried, but failed, to establish an Al-

tai written language based on Teleut, using the

Cyrillic alphabet. In 1922, the Soviets succeeded in

creating an Altai literary language, and, since 1930,

the Altais have had their own publishing house.

In spite of internal differences, Altai societies

share certain general traits. They are highly patri-

archal, for example: Women do domestic work,

whereas men herd horses and dairy cows. Since the

1750s, most Altai have been Russian Orthodox, but

a minority practices Lamaism and some practice

shamanism.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ETHNOGRAPHY, RUSSIAN AND SO-

VIET; KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZAKHS; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mote, Victor L. (1998). Siberia: Worlds Apart. Boulder,

CO: Westview.

Wixman, Ronald. (1984). The Peoples of the USSR: An

Ethnographic Handbook. Arkmonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

V

ICTOR

L. M

OTE

ALTYN

Monetary unit used in Russia from the last quar-

ter of the fourteenth century until the eighteenth

century.

The altyn’s first use was directly connected

with the appearance of the denga, another mone-

tary unit and coin that came into existence at the

same time. Six dengi (pl.) equaled one altyn. The

word altyn was a lexicological borrowing into

Russian from Mongol, meaning “six.” From its ori-

gins, the altyn was mainly used in the central and

eastern lands of Russia (Moscow, Ryazan, Tver),

but spread to the lands of Novgorod and Pskov by

the early sixteenth century. In the early eighteenth

century, the altyn became synonymous with a sil-

ver coin that equaled about three kopeks.

See also: DENGA; GRIVNA; KOPECK; RUBLE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Spassky, Ivan Georgievich. (1967). The Russian Monetary

System: A Historico-Numismatic Survey, tr. Z. I. Gor-

ishina and rev. L. S. Forrer. Amsterdam: Jacques

Schulman.

R

OMAN

K. K

OVALEV

AMALRIK, ANDREI ALEXEYEVICH

(1938–1980), Russian political activist, dissident,

publicist, playwright, exiled to Siberia from 1965

to 1966 and imprisoned in labor camps from 1970

to 1976.

Born in Moscow, Amalrik studied history at

Moscow University; he was expelled in 1963 for a

paper featuring unorthodox views on Kievan Rus.

Amalrik wrote several absurdist plays such as Moya

tetya zhivet v Volokolamske (My Aunt Lives in

Volokolamsk), Vostok-Zapad (East-West), and Nos!

Nos? No-s! (The Nose! The Nose? The No-se!), the

AMALRIK, ANDREI ALEXEYEVICH

55

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

latter referring to Gogol’s famous short story. In

1965, Amalrik was arrested for lacking official em-

ployment (“parasitism”) and charges that his—yet

unpublished—plays were “anti-Soviet and porno-

graphic.”

Exiled to Siberia for two and a half years, he

was released in 1966 and subsequently described

his experiences in Nezhelannoye puteshestvie v Sibir

(Involuntary Journey to Siberia, 1970). Amalrik’s

essay Prosushchestvuyet li Sovetsky Soyuz do 1984

goda? (Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?),

an astute and prophetic analysis of Soviet society’s

dim prospects for the future, brought him world-

wide fame. It was completed in 1969, published the

same year by the Herzen Foundation in Amster-

dam, and translated into many languages. As a re-

sult, Amalrik was put on trial and sentenced to

three years in Siberian camps, with another three

years added in 1973. Protests in the West led to a

commutation of the sentence from hard labor to

exile and ultimately to permission to leave the So-

viet Union in 1976. In the West, Amalrik was in-

volved in numerous human rights initiatives.

In 1980, Amalrik died in a car crash in Guadala-

jara, Spain. He was legally rehabilitated in 1991.

See also: DISSIDENT MOVEMENT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Keep, John. (1971). “Andrei Amalrik and 1984.” Russian

Review 30:335–345.

Svirski, Grigori. (1981). A History of Post-War Soviet Writ-

ing: The Literature of Moral Opposition. Ann Arbor:

Ardis.

P

ETER

R

OLLBERG

AMERICAN RELIEF ADMINISTRATION

As World War I ended, the United States helped

many countries around the world recover from the

effects of war through the American Relief Ad-

ministration (ARA). Herbert Hoover headed the

ARA and had opened numerous missions in Europe

by 1919. The primary goal of the ARA was to pro-

vide food relief, but it also provided medical aid,

relocation services, and much else. The ARA at-

tempted to open a mission in Russia in 1919 and

1920, but they were unsuccessful because the Bol-

sheviks suspected that the Americans had inter-

vened in the Russian Civil War. However, after the

horrible famine of the winter of 1920 and 1921,

and after writer Maxim Gorky petitioned Vladimir

Lenin to provide relief, the new Soviet government

recognized the need for the ARA in Russia. By the

summer of 1921, the ARA director for Europe,

Walter Lyman Brown, and Soviet assistant com-

missar of foreign affairs Maxim Litvinov reached

an agreement for an ARA mission in Russia. One

of the primary concerns for the Soviets was the po-

tential for American political activity in Russia.

Brown assured Litvinov that their mission was

solely to save as many lives as possible, and he ap-

pointed Colonel William N. Haskell to head the ARA

in Russia.

The ARA opened kitchens in Petrograd and

Moscow by September 1921, serving tens of thou-

sands of children. The ARA spread into smaller cities

and rural areas over the next several months, but

in several places faced opposition from local village

leaders and Communist Party officials. Most rural

local committees consisted of a teacher and two or

three other members who would serve the food to

the children from the local schools. This fed the

children, paid and fed the teacher, and continued

some measure of education. In addition to feeding

programs, the ARA employed thousands of starv-

ing and unemployed Russians to unload, transport,

and distribute food to the most famine-stricken ar-

eas. The ARA also established a medical division that

furnished medical supplies for hospitals, provided

treatments to tens of thousands of people, and con-

ducted sanitation inspections. It was estimated that

the ARA provided about eight million vaccinations

between 1921 and 1923.

By the summer of 1922, disputes within the

ARA administration in the United States and be-

tween the ARA and the Soviet government placed

the mission’s future in doubt. Hoover and Haskell

disagreed about the duration and tactics of the mis-

sion in Russia. In September 1922, the chairman of

the All-Russian Famine Relief Committee, Lev

Kamenev, announced that the ARA was no longer

needed, despite the reports that showed many ar-

eas in worse condition than before. Over the next

few months, the Soviet government urged the ARA

to limit its operations, even though about two mil-

lion children were added to those eligible for relief

in 1922. Several leading Bolsheviks had taken a

stronger anti-American stance during the course of

the ARA operations, and Lenin was less integrally

involved because of illness. The ARA was gradually

marginalized and officially disbanded in July 1923,

after nearly two years of work. The Soviet gov-

AMERICAN RELIEF ADMINISTRATION

56

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ernment took over feeding its own starving and

undernourished population, while also trying to

dispel the positive impression the ARA had left

among the Russian population.

See also: CIVIL WAR OF 1917–1922; FAMINE OF 1921–1922;

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fisher, H. H. (1927). The Famine in Soviet Russia 1919–1923:

The Operations of the American Relief Administration.

New York: Macmillan.

Patenaude, Bertrand M. (2002). The Big Show in Bololand:

The American Relief Expedition to Soviet Russia in the

Famine of 1921. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press.

Weissman, Benjamin M. (1974). Herbert Hoover and

Famine Relief to Soviet Russia: 1921–1923. Stanford,

CA: Hoover Institution Press.

W

ILLIAM

B

ENTON

W

HISENHUNT

ANARCHISM

Anarchism, derived from the Greek word meaning

“without rule,” rose to prominence in the nine-

teenth century and reached well into the twentieth

century as a significant political force in Europe and

Russia. Anarchists sought the overthrow of all forms

of political rule in the name of a new society of

voluntary federations of cooperative associations or

syndicates. Anarchism also fought Marxism for

revolutionary leadership.

Russian anarchism, in particular, inspired an-

archist movements in Russia and Europe. Three

Russians were progenitors of modern anarchism:

Mikhail Alexsandrovich Bakunin (1814–1876),

Petr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (1842–1921), and Leo

Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828–1910). The three,

however, were contrasting personalities, each tak-

ing different slants on anarchist doctrine. Bakunin

ANARCHISM

57

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Villagers in Vaselienka, Samara, kneel in thanks to American Relief Administration inspector George N. McClintock.

© U

NDERWOOD

&U

NDERWOOD

/CORBIS

was ever the firebrand of revolutionary violence in

word and deed; Kropotkin the philosophical and sci-

entific propounder of a society based on coopera-

tion and mutual aid; and Tolstoy the proponent of

a Christ-inspired anarchism of nonviolence and

nonresistance to evil in the sense of not answering

another’s evil with evil.

Despite the wide intellectual influence of Kropot-

kin and Tolstoy, Bakunin epitomized the strategy

of violence to end all political power. Bakunin put

the brand on anarchism as a doctrine of violence.

Kropotkin’s followers objected to anarchist fac-

tions in Russia that turned to violence and terror-

ism as their characteristic mode of operation.

Among the names they assumed were the Black

Banner Bearers, Anarchist Underground, Syndical-

ists, Makhayevists (followers of Makhaysky), and

the Makhnovists (followers of Makhno in the

Ukraine).

In the wake of the 1917 revolution, Kropotkin

returned to Russia from exile in Europe with high

hopes for an anarchist future. Vladimir Lenin’s Bol-

sheviks soon dashed them. His funeral in 1921 was

the last occasion in which the black flag of anar-

chism was raised in public in Sovietized Russia. The

new regime executed anarchist leaders and de-

stroyed their organizations.

See also: BAKUNIN, MIKHAIL ALEXANDROVICH; KROPOTKIN,

PETR ALEXEYEVICH; TOLSTOY, LEO NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Avrich, Paul. (1967). The Russian Anarchists. Princeton,

NJ.: Princeton University Press.

C

ARL

A. L

INDEN

ANDREI ALEXANDROVICH

(d. 1304), prince of Gorodets and grand prince of

Vladimir (1294–1304).

Andrei Alexandrovich’s father, Alexander

Yaroslavich “Nevsky,” gave him Gorodets; after his

uncle, Grand Prince Vasily Yaroslavich, died, he

also received Kostroma. In 1277, when Andrei’s el-

der brother, Grand Prince Dmitry, went to Nov-

gorod, Andrei ingratiated himself to Khan Mangu

Temir by campaigning with him in the Caucasus.

In 1281 Andrei visited the Golden Horde, and Khan

Tuda Mangu gave him troops to evict Dmitry from

Vladimir. Andrei deposed his brother, but in 1282,

after learning that Dmitry had returned from

abroad and was assembling an army in his town

of Pereyaslavl Zalessky, he was forced to ask the

khan in Saray for reinforcements. Dmitry, mean-

while, solicited auxiliaries from Nogay, a rival

khan, and defeated Andrei. The latter remained hos-

tile. In 1293 he visited the Golden Horde again, and

the khan despatched an army, which invaded Suz-

dalia and forced Dmitry to abdicate. After Dmitry

died in 1294, Andrei became the grand prince of

Vladimir. Soon afterward, a coalition of princes

challenged his claim to Dmitry’s Pereyaslavl. In

1296 all the princes met in Vladimir and, after re-

fusing to give Pereyaslavl to Andrei, concluded a

fragile agreement. Thus, in 1299, when the Ger-

mans intensified their attacks against the Nov-

gorodians, Andrei refused to send them help

because he feared that if he did, the other princes

would attack him. In 1300 they rejected his claim

to Pereyaslavl at another meeting. Three years later,

after appealing to the khan and failing yet again

to get the town, he capitulated. Andrei died in

Gorodets on July 27, 1304.

See also: ALEXANDER YAROSLAVICH; GOLDEN HORDE;

NOVGOROD THE GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fennell, John. (1983). The Crisis of Medieval Russia

1200–1304. London: Longman.

Martin, Janet. (1995). Medieval Russia 980–1584. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

ANDREI YAROSLAVICH

(d. 1264), grand prince of Vladimir (1249–1252)

and progenitor of the princes of Suzdal.

The third son of Yaroslav Vsevolodovich and

grandson of Vsevolod Yurevich “Big Nest,” Andrei

Yaroslavich survived the Tatar invasion of Suzdalia

in 1238. Three years later the Novgorodians re-

jected him as their prince, but on April 5, 1242, he

assisted his elder brother Alexander Yar “Nevsky”

in defeating the Teutonic Knights at the famous

“battle on the ice” on Lake Chud (Lake Peypus).

There is no clear information about Andrei’s activ-

ities after their father died and their uncle Svy-

atoslav occupied Vladimir in 1247. Andrei may

ANDREI ALEXANDROVICH

58

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

have usurped Vladimir. In any case, he and Alexan-

der went to Saray separately, evidently to settle the

question of succession to Vladimir. But Khan Baty

sent them to Mongolia, to the Great Khan in

Karakorum. They returned in 1249, Alexander as

the grand prince of Kiev and of all Rus, and Andrei

as the grand prince of their patrimonial domain of

Vladimir. In 1252 Andrei defiantly refused to visit

Saray to renew his patent for Vladimir with the

new great khan, Mongke, but Alexander went, ev-

idently to obtain that patent for himself. The khan

sent troops against Andrei, and they defeated him

at Pereyaslavl Zalessky. After he fled to the Swedes,

Alexander occupied Vladimir. Later, in 1255, An-

drei returned to Suzdalia and was reconciled with

Alexander, who gave him Suzdal and other towns.

In 1258 he submissively accompanied Alexander to

Saray, and in 1259 helped him enforce Tatar tax

collecting in Novgorod. Andrei died in Suzdal in

1264.

See also: ALEXANDER YAROSLAVICH; BATU; GOLDEN HORDE;

VSEVOLOD III

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fennell, John. (1973). “Andrej Yaroslavic and the Strug-

gle for Power in 1252: An Investigation of the

Sources.” Russia Mediaevalis 1:49–62.

Fennell, John. (1983). The Crisis of Medieval Russia

1200–1304. London: Longman.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

ANDREI YUREVICH

(c. 1112–1174), known as Andrei Yurevich “Bo-

golyubsky,” prince of Suzdalia (Rostov, Suzdal, and

Vladimir).

Although historians disagree on Andrei Yure-

vich’s objectives, it is established that he defended

the traditional order of succession to Kiev but chose

to live in his patrimony of Vladimir, whose polit-

ical, economic, cultural, and ecclesiastical impor-

tance he attempted to raise above that of Kiev.

In 1149 Andrei’s father, Yuri Vladimirovich

“Dolgoruky,” gave him Vyshgorod, located north

of Kiev, and then transferred him to Turov, Pinsk,

and Peresopnitsa. Two years later Andrei returned

to Suzdalia. In 1155 Yuri gave him Vyshgorod once

again, but Andrei returned soon afterward to

Vladimir on the Klyazma. After Yuri died in Kiev

in 1157, the citizens of Rostov, Suzdal, and Vladimir

chose Andrei as their prince. He had autocratic am-

bitions for Suzdalia and, according to some, for all

of Rus. He weakened the power of the veche (pop-

ular assembly), treated boyars like vassals, and, in

1161, evicted his brothers and two nephews from

Suzdalia. Moreover, he spurned the powerful bo-

yars of Rostov and Suzdal by making the smaller

town of Vladimir his capital. He lived at nearby Bo-

golyubovo, after which he obtained his sobriquet

“Bogolyubsky.” He beautified Vladimir by building

its Assumption Cathedral, its Golden Gates mod-

eled on those of Kiev, his palace at Bogolyubovo,

and the Church of the Intercession of Our Lady on

the river Nerl. He successfully expanded his do-

mains into the lands of the Volga Bulgars and as-

serted his influence over Murom and Ryazan.

However, Andrei failed to create an independent

metropolitanate in Vladimir.

In 1167 Rostislav Mstislavich of Kiev died, and

Andrei became the senior and most eligible of the

Monomashichi (descendants of Vladimir Mono-

makh, reign 1113–1125) to rule Kiev. Mstislav

Izyaslavich of Volyn preempted Andrei’s bid for

Kiev and appointed his son to Novgorod. Andrei

saw Mstislav’s actions as a violation of the tradi-

tional order of succession to Kiev and as a challenge

to his own interests in Novgorod. Thus in 1169 he

sent a large coalition of princes to evict Mstislav.

They fulfilled their mission and plundered Kiev in

the process. Some historians argue that this event

marked a turning point in the history of Rus; Kiev’s

capture signaled its decline and Andrei’s attempt to

subordinate it to Vladimir. Others argue that An-

drei sought to recover the Kievan throne for the

rightful Monomashich claimants because Kiev was

the capital of the land, thereby affirming its im-

portance even after it was plundered.

Andrei broke tradition by not occupying Kiev

in person. He appointed his brother, Gleb, to rule

it in his stead. Even though Andrei was able to sum-

mon troops from Suzdalia, Novgorod, Murom,

Ryazan, Polotsk, and Smolensk, he failed to assert

his control over Kiev. Its citizens evidently poisoned

Gleb. In 1173 Andrei ordered the Rostislavichi (de-

scendants of Rostislav Mstislavich of Smolensk) to

vacate Kiev, but later they succeeded in evicting

his lieutenants and taking them captive. Andrei

organized a second campaign with Svyatoslav

Vsevolodovich of Chernigov, to whom he agreed

to cede control of Kiev, but the coalition failed to

take the city. While Andrei was waiting to receive

approval from Svyatoslav to hand over Kiev to the

ANDREI YUREVICH

59

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Rostislavichi, his boyars murdered him on June 29,

1174.

See also: BOYAR; KIEVAN RUS; NOVGOROD THE GREAT

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Franklin, Simon, and Shepard, Jonathan. (1996). The

Emergence of Rus 750–1200. London: Longman.

Hurwitz, Ellen. (1980). Prince Andrej Bogoljubskij: The

Man and the Myth. Florence: Licosa Editrice.

Martin, Janet. (1995). Medieval Russia 980–1584. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Pelenski, Jaroslaw. (1998). The Contest for the Legacy of

Kievan Rus’ (East European Monographs 377). New

York: Columbia University Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

ANDREYEV, LEONID NIKOLAYEVICH

(1871–1919), Russian prose writer, playwright, and

publicist whose works, internationally acclaimed in

his lifetime, are infused with humanistic protest

against social oppression and humiliation.

Born on August 21, 1871, in the town of Oryol

(Orel), Leonid Nikolayevich Andreyev studied law

at St. Petersburg University and briefly practiced

as a lawyer. A volume of stories, published in 1901

by Maxim Gorky’s “Znanie” enterprise, made him

famous. After the death of his first wife in 1906

and the violent oppression of the anti-autocratic

mutinies that occurred between 1905 and 1907,

Andreyev entered a period of deep resignation,

abandoning radical leftist ideas but failing to de-

velop viable alternatives. His political confusion res-

onated with the liberal intelligentsia, for whose he

became the most fashionable of authors in the

1910s.

In Andreyev’s narratives, crass images of irra-

tionality and hysteria are often blended with crude

melodrama, yet they also reveal persistent social

sensitivities. Thus, the short story “Krasnyi smekh”

(“Red Laughter,” 1904) depicts the horror of war,

whereas “Rasskaz o semi poveshennykh” (“The Seven

Who Were Hanged,” 1908) attacks capital punish-

ment while idealizing political terrorism. An-

dreyev’s plays, closely associated with Symbolism,

caused scandals and enjoyed huge popularity. His

unfinished novel Dnevnik Satany (Satan’s Diary,

1918) was inspired by the death of U.S. million-

aire Alfred Vanderbilt on the Lusitania in 1915, and

seeks to convey the doom of bourgeois society.

In addition to his writing, Andreyev was also

an accomplished color photographer and painter.

He displayed pro-Russian patriotism in World War

I, but welcomed the February Revolution of 1917.

Later that year, he radically opposed the Bolshevik

coup and emigrated to Finland. In his last essay,

“S.O.S.” (1919), he called upon the president of the

United States to intervene in Russia militarily. An-

dreyev died on September 12th of that same year.

See also: GORKY, MAXIM; SILVER AGE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Newcombe, Josephine. (1972). Leonid Andreyev. Letch-

worth, UK: Bradda Books.

Woodward, James. (1969). Leonid Andreyev: A Study. Ox-

ford, UK: Clarendon Press.

P

ETER

R

OLLBERG

ANDREYEVA, NINA ALEXANDROVNA

(b. 1938), teacher, author, political activist, and so-

cial critic.

Born on October 12, 1938, in Leningrad, Nina

Alexandrovna Andreyeva joined the Communist

Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1966, and be-

came a teacher of chemistry at the Leningrad Tech-

nical Institute in 1973. A self styled Stalinist and

devotee of political order, she wrote an essay that

defended many aspects of the Stalinist system, as-

sailed reformists’ efforts to provide a more accu-

rate picture of the history of the USSR, and implied

that General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and his

closest supporters were not real communists. Her

essay “I Cannot Forsake My Principles” was pub-

lished in the orthodox newspaper Sovetskaia Rossiya

at a time when Gorbachev and Alexander Niko-

layevich Yakovlev were abroad, and cited (without

attribution) an orthodox report by the secretary of

the Party’s Central Committee, Yegor Kuzmich Lig-

achev, in February 1988. Officials in the ideologi-

cal department of the Central Committee evidently

edited her original letter, and Ligachev reportedly

ordered its dissemination throughout the party.

Ligachev repeatedly denied responsibility for its

publication.

Orthodox party officials applauded the essay,

whereas members of the liberal intelligentsia feared

ANDREYEV, LEONID NIKOLAYEVICH

60

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

that it represented a major defeat for the intellec-

tual freedom supported by the general secretary.

Gorbachev subsequently revealed that many mem-

bers of the Politburo seemed to share Andreyeva’s

views, and that he had to browbeat them into ap-

proving the publication of an official rejoinder. The

published response appeared in Pravda on April 5,

1988, and was not nearly as forceful as its authors

have claimed. In the aftermath of this discussion,

the General Secretary at least temporarily tightened

his own control over the Secretariat of the Central

Committee. The entire episode may have con-

tributed to his decision to reform the Secretariat in

the fall of 1988.

Andreyeva subsequently played a leadership

role in the formation of orthodox communist or-

ganizations. She headed the organizing committee

of the Bolshevik Platform of the CPSU that “ex-

pelled” Gorbachev from the party in September

1991. In November 1991, she became the general

secretary of the small but militant All-Union Com-

munist Party of Bolsheviks. In October 1993, the

party was temporarily suspended along with fif-

teen other organizations after President Yeltsin’s re-

pression of the attempted coup against his regime.

In May 1995 she was stripped of her post as the

head of the St. Petersburg Central Committee of the

party for “lack of revolutionary activity.”

See also: CENTRAL COMMITTEE; COMMUNIST PARTY OF

THE SOVIET UNION; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYE-

VICH; LIGACHEV, YEGOR KUZMICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Archie. (1997). The Gorbachev Factor. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

McCauley, Martin. (1997). Who’s Who in Russia since

1990. New York: Routledge.

Remnick, David. (1994). Lenin’s Tomb. New York: Ran-

dom House.

J

ONATHAN

H

ARRIS

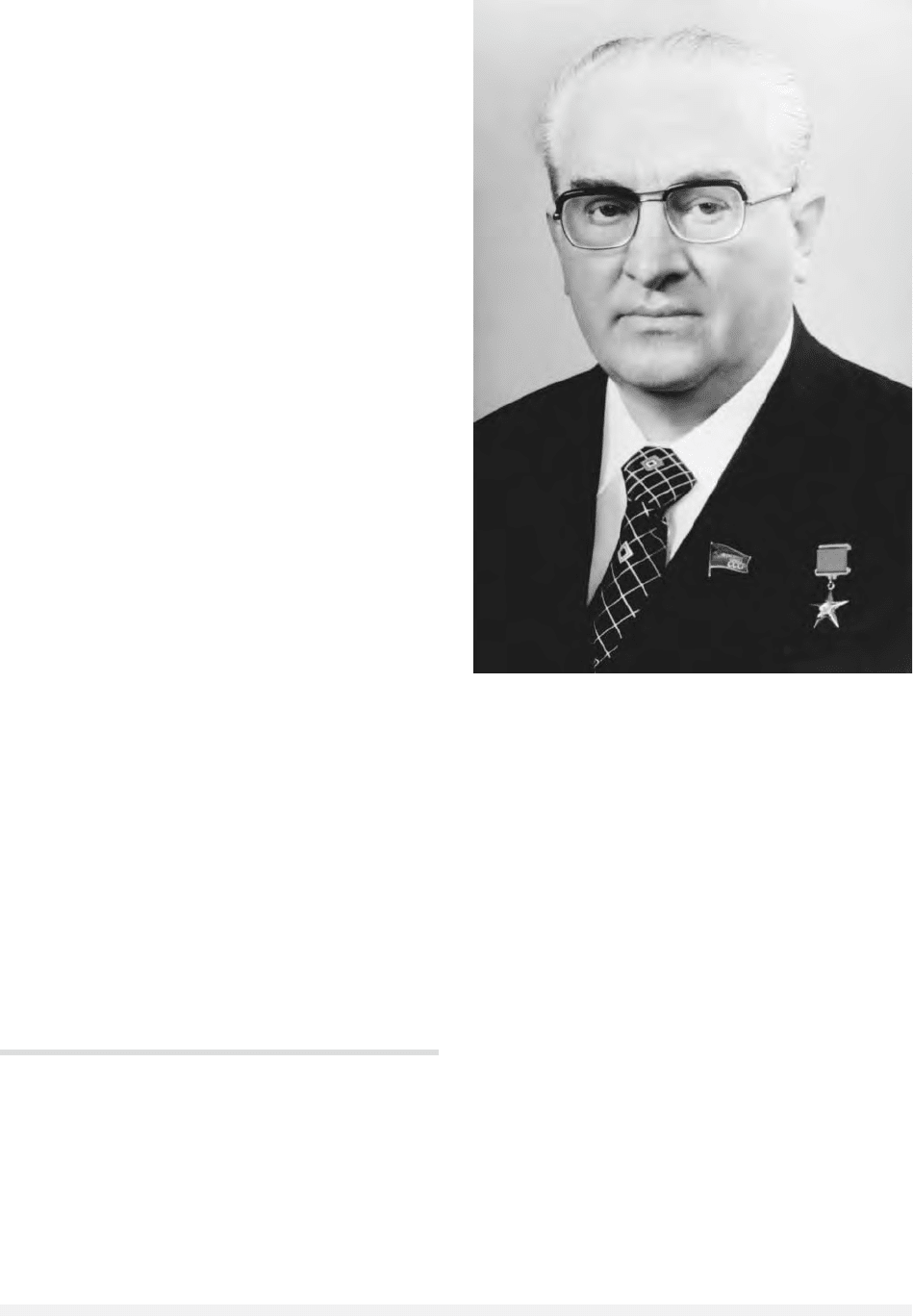

ANDROPOV, YURI VLADIMIROVICH

(1914–1984), general secretary of the Communist

Party of the Soviet Union (1982–1984).

Yuri Andropov was born on June 15, 1914, in

the southern Russian region of Stavropol. He rose

rapidly through the ranks of the Young Commu-

nist League (Komsomol). During World War II he

worked with the partisan movement in Karelia, and

after the war he became second secretary of the re-

gional Party organization. He was transferred to

the Party apparatus in Moscow in 1951 and was

the ambassador to Hungary at the time of the So-

viet invasion in 1956. He played a key role in en-

couraging the invasion.

In 1957 Andropov returned to Moscow to be-

come head of the Central Committee’s Bloc Rela-

tions Department. There he inherited a group of

some of the most progressive thinkers of the Brezh-

nev era, many of the leading advocates for change

who were working within the system. This con-

tributed later to Andropov’s reputation as a pro-

gressive thinker. He continued to oversee relations

with other communist countries after he was pro-

moted to Central Committee secretary in 1962. In

1967 he was appointed the head of the Committee

on State Security (KGB) and a candidate member of

ANDROPOV, YURI VLADIMIROVICH

61

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Official portrait of Yuri Andropov, CPSU general secretary,

1982–1984. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

the ruling Politburo. He was promoted to the rank

of full Politburo member in 1971. As the head of

the KGB, Andropov led active efforts against dissi-

dents at home and enhanced the KGB collection ef-

forts abroad. To be in a better position to succeed

Leonid Brezhnev, Andropov gave up the chair-

manship of the KGB in May 1982 and returned to

the Central Committee as a senior member of the

Secretariat. His chief rival in the succession strug-

gle was Konstantin Chernenko, who was being ac-

tively promoted by Brezhnev. However, Chernenko

lacked Andropov’s broad experience, and when

Brezhnev died in November 1982, Andropov was

elected general secretary by a plenum of the Com-

munist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). In June

1983 he was elected chairman of the Presidium of

the USSR Supreme Soviet—the head of state.

When Andropov was elevated to the head of the

Party, there were great hopes that he would end

the stagnation that had characterized the Brezhnev

years and that he would reinvigorate the Party and

its policies. From his years as head of the KGB, An-

dropov had an excellent perspective on the depth of

the problems facing the Soviet Union. There was

also an active effort to promote his image as a pro-

gressive thinker. During his very brief tenure as

Party leader, Andropov was able to begin diverging

from the norms of the Brezhnev era. This was a

time of rapid personnel turnover. In addition to

making key changes in the top Party leadership, he

replaced a large number of ministers and regional

party leaders with younger leaders. Most impor-

tant, Andropov actively advanced the career of the

youngest member of the Politburo, Agriculture Sec-

retary Mikhail Gorbachev, giving him broad au-

thority and experience in the Party that helped pave

the way for his ascent to Party leadership. All signs

indicate that Andropov was hoping to make Gor-

bachev his successor.

Andropov’s brief tenure was not sufficient to

make a similar impact on policy. While he was

much more open than Brezhnev in recognizing the

country’s problems, particularly in the economic

sphere, Andropov was cautious by nature and did

not come to office with any plan for tackling them.

He did, however, begin a serious discussion of the

need for economic reform, spoke positively about

economic innovation in Eastern Europe, and began

to take some cautious steps to improve the situa-

tion. His regime is best remembered for the disci-

pline campaign: an effort to enforce worker

discipline, punishing workers who did not report

for duty on time or were drinking on the job. He

also introduced other minor reforms aimed at im-

proving productivity. Andropov began to tackle the

problem of corruption at higher levels and expelled

two members of the Central Committee who had

been close associates of Brezhnev. He also intro-

duced somewhat greater openness in Party affairs,

publishing accounts of the weekly Politburo meet-

ings and deliberations of the CPSU plenum. These

measures, together with his personnel moves, cre-

ated a positive sense of cautious change, as well as

a hope that the Soviet leadership would start to ad-

dress the problems facing the country, now that it

was aware of them. Probably the most notable

event of Andropov’s tenure was the accidental

shooting down by the Soviet military of a Korean

Airlines plane that strayed into Soviet airspace in

the Far East in September 1983.

The contest to succeed Andropov appears to

have been the main preoccupation of the party lead-

ership following his election. Only three months

into his tenure, Andropov’s health began to dete-

riorate sharply as a result of serious kidney prob-

lems, and he was regularly on dialysis for the rest

of his life. He dropped out of sight in August 1983

and did not appear again in public. He died in Feb-

ruary 1984. Andropov was not in office long enough

for his protégé, Gorbachev, to gain the upper hand

in the succession struggle, and he was succeeded

by seventy-two-year-old Konstantin Chernenko,

who was closely associated with the status quo of

the Brezhnev era.

See also: CHERNENKO, KONSTANTIN USTINOVICH; GEN-

ERAL SECRETARY; GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH;

STATE SECURITY, ORGANS OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Archie. (1983). “Andropov: Discipline and Re-

form.” Problems of Communism 33(1):18–31.

Medvedev, Zhores A. (1983). Andropov. New York: Nor-

ton.

M

ARC

D. Z

LOTNIK

ANDRUSOVO, PEACE OF

The Peace of Andrusovo (1667) concluded a thirteen-

year period of conflict between Muscovy, Poland-

Lithuania, and Sweden, known as the Thirteen

Year’s War (1654–1667). It marked the end of

Poland-Lithuania’s attempts at eastward expan-

sion, and divided the Ukraine into Polish (right

ANDRUSOVO, PEACE OF

62

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY