Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

country villas. Fire and rot have destroyed most

wooden structures from the distant past, and there

is no extensive evidence that wooden structures ap-

peared before the late sixteenth century. Yet the ba-

sic forms of wooden architecture are presumably

rooted in age-old traditions. Remarkable for their

construction logic, wooden churches also display

elaborate configurations. One example is the Church

of the Transfiguration at Kizhi (1714), whose pyra-

mid of recessed levels supports twenty-two cupo-

las. Although such structures achieved great

height, the church interior was usually limited by

a much lower ceiling. Log houses also ranged from

simple dwellings to large three-story structures pe-

culiar to the far north, with space for the family

as well as shelter for livestock during the winter.

Wooden housing is still used extensively, not only

in the Russian countryside, but also in provincial

cities (particularly in Siberia and the Far East),

where the houses often have plank siding and

carved decorative elements.

See also: KIEVAN RUS; MOSCOW; NOVGOROD THE GREAT;

ST. PETERSBURG

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brumfield, William Craft. (1991). The Origins of Mod-

ernism in Russian Architecture. Berkeley: University

of California Press.

Brumfield, William Craft. (1993). A History of Russian

Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cracraft, James. (1988). The Petrine Revolution in Russian

Architecture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hamilton, George Heard. (1983). The Art and Architecture

of Russia. New York: Penguin Books.

Khan-Magomedov, Selim O. (1987). Pioneers of Soviet Ar-

chitecture. New York: Rizzoli.

W

ILLIAM

C

RAFT

B

RUMFIELD

ARCHIVES

Research access to and knowledge about archives

in the Russian Federation since 1991 have been key

factors in the opening of historical and cultural in-

quiry in what had previously been a predominantly

closed society. Yet the opening of archives would

have had much less impact on society and history

had in not been for the central attention given to

archives under Soviet rule. And Russian archives

would hardly be so rich in the early twenty-first

century had it not been for the early manuscript

repositories in the church and the long tradition of

preserving the records of government and society

in Russian lands. For example, the “Tsar’s Archive”

of the sixteenth century paralleled archives of

the government boards (prikazy) of the Muscovite

state. Peter the Great’s General Regulation of

1720 decreed systematic management of state

records. During the late nineteenth century, the

Moscow Archive of the Ministry of Justice became

the most important historical archive. Before the

revolutions of 1917, however, most recent and cur-

rent records were maintained by state agencies

themselves, such as the various ministries, paral-

leled, for example, by the archive of the Holy

Synod, the governing body of the Orthodox Church.

The Imperial Archeographic Commission, provin-

cial archival commissions, the Academy of Sciences,

major libraries, and museums likewise contributed

to the growth of archives and rich manuscript col-

lections.

The Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917

had as revolutionary an impact on archives as it

did on most other aspects of society and culture,

and stands as the single most important turning

point in the history of Russian archives. To be sure,

the turmoil of the revolution and civil war years

brought considerable disruption, and indeed de-

struction, to the archival and manuscript legacy.

Yet it brought with it the most highly centralized

state archival system and the most highly state-

directed principles of preservation and management

of documentary records that the world had ever

seen. Deeply grounded in historical theory and

committed to its own orthodoxy of historical in-

terpretation, Marxism-Leninism as an ideology

gave both extensive philosophical justification and

crucial political importance to documentary con-

trol. As the highly centralized political system es-

tablished firm rule over of state and society, the

now famous archival decree of Vladimr Lenin (June

1, 1918) initiated total reorganization and state

control of the entire archival legacy of the Russian

Empire.

One of the most significant Soviet innovations

was the formation of the so-called State Archival

Fond (Gosudarstvennyi arkhivnyi fond—GAF), a le-

gal entity extending state proprietorship to all

archival records regardless of their institutional or

private origin. With nationalization, this theoreti-

cal and legal structure also extended state custody

and control to all current records produced by cur-

ARCHIVES

73

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

rent agencies of state and society. Subsequently a

parallel Archival Fond of the Communist Party

emerged with proprietorship and custody of Party

records.

A second innovation was the establishment of

a centralized state agency charged with the man-

agement of the State Archival Fond, enabling the

centralization, standardization, and planning that

characterized Soviet archival development. Indica-

tive of the importance that Stalin attributed to con-

trol of archives and their utilization, from 1938

through 1960 the Main Archival Administration of

the USSR (Glavarkhiv SSSR) was under the Com-

missariat and later (after 1946), Ministry of Inter-

nal Affairs (NKVD, MVD). Subsequently it was

responsible directly to the Council of Ministers of

the USSR.

A third innovation saw the organization of a

network of archival repositories, although with

substantial reorganizations during the decades of

Soviet rule. A series of central state archives of the

USSR paralleled central state archives for the union

republics, with a hierarchical network of regional

archives, all controlled and adopting standardized

organizational and methodological guidelines dic-

tated by Glavarkhiv in Moscow. Strict disposal and

retention schedules regulated what went into the

archives. A parallel network of Communist Party

archives emerged. Records of the Ministry of For-

eign Affairs remained separate, as did those of the

security services and other specialized repositories

ranging from geological data to Gosfilmofond for

feature films. The Academy of Sciences maintained

its own archival network, and archival materials

in libraries and museums remained under their

own controlling agencies.

Public research availability of the nation’s doc-

umentary legacy was severely restricted during the

Soviet era, although there was a brief thaw after

1956, and more significant research possibilities

starting in the Gorbachev era of glasnost after the

mid-1980s. But while limited public access to

archives was a hallmark of the regime, so was the

preservation and control of the nation’s documen-

tary legacy in all spheres.

In many ways, those three Soviet innovations

continue to characterize the archival system in the

Russian Federation, with the most notable innova-

tion of more openness and public accessibility. Al-

ready in the summer of 1991, a presidential decree

nationalized the archival legacy of the Communist

Party, to the extent that the newly reorganized state

archival system was actually broader than its So-

viet predecessor. The Soviet-era Glavarkhiv was re-

placed by the Archival Service of the Russian

Federation (Rosarkhiv, initially Roskomarkhiv). Rus-

sia’s first archival law, the Basic Legislature of the

Russian Federation on the Archival Fond of the Russ-

ian Federation and Archives, enacted in July 1993,

extended the concept of a state “Archival Fond.” Al-

though it also provided for a “non-State” compo-

nent to comprise records of non-governmental,

commercial, religious, and other societal agencies, it

did not permit re-privatization of holdings nation-

alized during the Soviet period. Nor did it provide

for the apportionment of archival records and man-

uscript materials gathered in central Soviet reposi-

tories from the union republics that after 1991

emerged as independent countries. The latter all re-

mained legally part of the new Russian “Archival

Fond.”

In most cases, the actual archival repositories

that developed during the Soviet era continue to ex-

ist, although almost all of their names have

changed, with some combined or reorganized. As

heir to Soviet-period predecessors, fourteen central

state archives constitute the main repositories for

governmental (and former Communist Party)

records in different historical, military, and eco-

nomic categories, along with separate repositories

for literature and art, sound recordings, documen-

tary films, and photographs, as well as technical

and engineering documentation. As a second cate-

gory of central archives, a number of federal agen-

cies still have the right to retain their own records,

including the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Defense,

Internal Affairs, and the security services. Munici-

pal archives in Moscow and St. Peteresburg com-

prise a third category. As there were in the Soviet

period, there are also many archival repositories in

institutes and libraries under the Russian Academy

of Sciences, and libraries and museums under the

Ministry of Culture and other agencies. The exten-

sive network of regional state (including former

Communist Party) archives for each and every sub-

ject administrative-territorial unit of the Russian

Federation, all of which have considerable more au-

tonomy from Moscow than had been the case be-

fore 1991.

The most important distinction between Russ-

ian archives in the early twenty-first century and

those under Soviet rule is the principle of openness

and general public accessibility. Significantly, such

openness extends to the information sphere, whereby

ARCHIVES

74

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

published directories now identify all major repos-

itories and their reference systems. New archival

guides and specialized finding aids reveal the hold-

ings of many important archives (many with for-

eign subsidies). And since 1997, information about

an increasing number of archives is publicly avail-

able in both Russian and English-language versions

on the Internet.

Complaints abound about continued restric-

tions in sensitive areas, such as the contemporary

archives of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, De-

fense, and the security services. Declassification has

been all to slow in many areas, including more

recent Communist Party records, and new laws

governing state secrets often limit the otherwise

proclaimed openness. Yet often the most serious re-

search complaints stem from economic causes—

closures due to leaking roofs or lack of heat, slow

delivery time, and high copying fees. While Russia

has opened its archives to the world, there have

been more dangers of loss due to inadequate sup-

port for physical facilities and professional staff,

leading to commercialization and higher service

charges, because the new federal government has

had less ideological and political cause than its So-

viet predecessors to subsidize new buildings, phys-

ical preservation, and information resources

adequately for the archival heritage of the nation.

See also: CENSORSHIP; NATIONAL LIBRARY OF RUSSIA;

RUSSIAN STATE LIBRARY; SMOLENSK ARCHIVE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy. (1989). A Handbook for

Archival Research in the USSR. Washington, DC,: Ken-

nan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies and the

International Research & Exchanges Board.

Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy. (1998). Archives of Russia

Seven Years After: “Purveyors of Sensations” or “Shad-

ows Cast out to the Past.” Washington, DC: Cold War

International History Project, Working Paper, no.

20, parts 1 and 2. Electronic version: <http://cwihp

.si.edu/topics/pubs>.

Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy, ed. (2000). Archives of Rus-

sia: A Directory and Bibliographic Guide to Holdings in

Moscow and St. Petersburg. 2 vols. Armonk, NY: M.

E. Sharpe.

Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy. (2003). “Archives of Rus-

sia—ArcheoBiblioBase on Line.” <http://www.iisg

.nl/~abb>.

P

ATRICIA

K

ENNEDY

G

RIMSTED

ARMAND, INESSA

(1874–1920), née Elisabeth Stefan, revolutionary

and feminist, first head of the zhenotdel, the women’s

section of the Communist Party.

Born in France, Inessa Armand came to Russia

as a child when her parents died and her aunt took

a job as governess in the wealthy Armand mer-

chant family. At age nineteen she married Alexan-

der Armand, who was to support her and her

numerous Bolshevik undertakings throughout his

life. In 1899 she became involved in the Moscow

Society for Improving the Lot of Women, a phil-

anthropic organization devoted to assisting prosti-

tutes and other poor women. By 1900 she was

president of the society and working hard to cre-

ate a Sunday school for working women.

In 1903, disillusioned with philanthropic work,

she joined the Social Democratic Party and became

active in revolutionary propaganda work. In exile

in Europe from 1909 to 1917, with a brief illegal

return to Russia, she helped Vladimir Lenin estab-

lish a party school at Longjumeau, France, in 1911;

she taught there herself. When Russian women

workers gained the right to vote and be elected to

factory committees in 1912, Armand, Nadezhda

Krupskaya, and others persuaded Lenin to create a

special journal Rabotnitsa (Woman Worker). Al-

though Armand and other editors insisted that

women workers were not making special demands

separate from those of men, they did recognize the

importance of writing about women’s health and

safety issues in the factories.

During World War I Armand was one of

Lenin’s and the party’s principal delegates to inter-

national socialist conferences, especially those of

women protesting the war. In April 1917 Armand

returned to Petrograd with Lenin and Krupskaya.

Soon she was made a member of the Executive

Committee of the Moscow Provincial Soviet and

of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee

(VtsIK), as well as chair of the Moscow Provincial

economic council. Her crowning achievement,

however, was her role in founding the women’s

section of the Communist Party, the zhenotdel.

In that role she worked on problems as diverse

as supporting legislation legalizing abortion, com-

bating prostitution, creating special sections for the

protection of mothers and infants in the Health

Commissariat, working with the trade unions, and

developing agitation methods for peasant women.

In all of these, Armand advocated the creation of

ARMAND, INESSA

75

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

special methods for work among women, given

women’s historical backwardness and the preju-

dices of many men towards women’s increased

participation in the workforce and in society.

However, Armand’s tenure as director of the

zhenotdel was short-lived. On September 24, 1920,

while on leave in the Caucasus, she succumbed to

cholera and died.

See also: FEMINISM; KRUPSKAYA, NADEZHDA KONSTAN-

TINOVNA; LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; ZHENOTDEL

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clements, Barbara Evans. (1997). Bolshevik Women. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Elwood, Ralph C. (1992). Inessa Armand: Revolutionary

and Feminist. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

McNeal, Robert H. (1972). Bride of the Revolution: Krup-

skaya and Lenin. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan

Press.

Stites, Richard. (1975). “Kollontai, Inessa, and Krupskaia:

A Review of Recent Literature.” Canadian-American

Slavic Studies 9(1):84–92.

Stites, Richard. (1978). The Women’s Liberation Movement

in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism,

1860–1930. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wood, Elizabeth A. (1997). The Baba and the Comrade:

Gender and Politics in Revolutionary Russia. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

E

LIZABETH

A. W

OOD

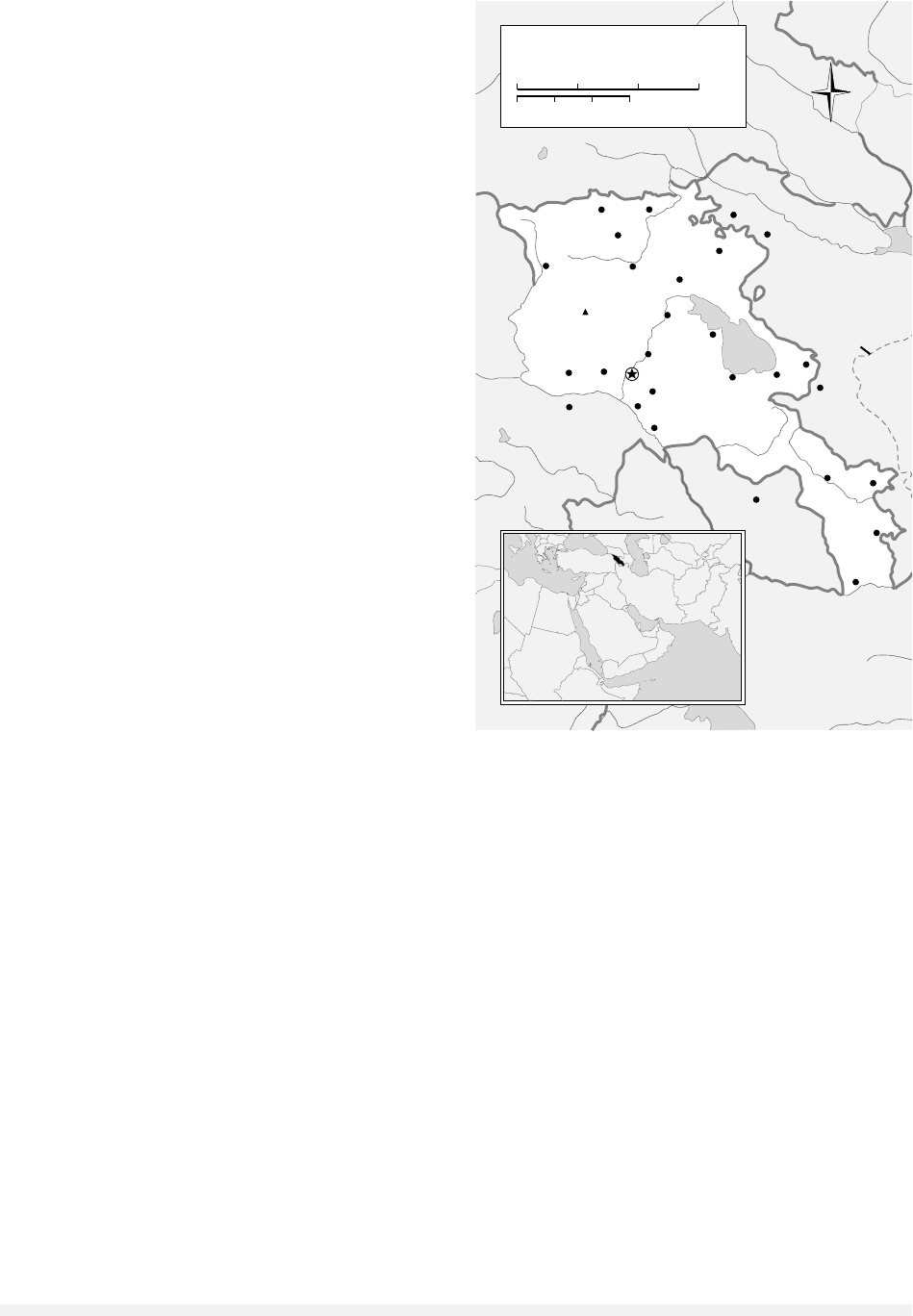

ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS

Armenia is a landlocked, mountainous plateau that

rises to an average of 3,000 to 7,000 feet (914 to

2,134 meters) above sea level. It extends to the Ana-

tolian plateau in the west, the Iranian plateau in

the southwest, the plains of the South Caucasus in

the north, and the Karadagh Mountains and the

Moghan Steppe in the south and southeast. The Ar-

menian highlands stretch roughly between longi-

tudes 37° and 48.5° east, and 38° and 41° north

latitudes, with a total area of some 150,000 square

miles (388,500 square kilometers). In present-day

terms, historic Armenia comprises most of eastern

Turkey, the northeastern corner of Iran, parts of

the Azerbaijan and Georgian Republics, as well as

the entire territory of the Armenian Republic.

GEOLOGY, GEOGRAPHY,

AND CLIMATE

The Kur (Kura) and Arax (Araxes) Rivers separate

the Armenian highlands in the east from the low-

lands that adjoin the Caspian Sea. The Pontus

Mountains, which connect to the Lesser Caucasus

mountain chain, separate Armenia from the Black

Sea and Georgia and form the region’s northern

boundary. The Taurus Mountains, which join the

upper Zagros Mountains and the Iranian Plateau,

form the southern boundary of Armenia and sep-

arate it from Syria, Kurdistan, and Iran. The west-

ern boundary of Armenia has generally been

between the western Euphrates River and the

northern stretch of the Anti-Taurus Mountains.

Armenians also established communities east of the

Kur as far as the Caspian Sea, and states west of

the Euphrates as far as Cilicia on the Mediterranean

Sea.

Lying on the Anatolian fault, the Armenian

plateau is subject to seismic tremors. Major earth-

quakes have been recorded there since the ninth

century, some of which have destroyed entire cities.

The most recent earthquake in the region, occur-

ring on December 7, 1988, killed some 25,000 peo-

ple and leveled numerous communities.

Some fifty million years ago, the geological

structure of Armenia underwent many changes,

creating great mountains and high, now-inactive,

volcanic peaks throughout the plateau. The larger

peaks of Mount Ararat (16,946 feet; 5,279 meters),

Mount Sipan (14,540 feet; 4,432 meters), and

Mount Aragats (13,410 feet; 4,087 meters), and

the smaller peaks of Mount Ararat (12,839 feet;

3,913 meters), and Mount Bingol (10,770 feet;

3,283 meters), from which the Arax and the Eu-

phrates Rivers originate, are some examples. Tufa,

limestone, basalt, quartz, and obsidian form the

main composition of the terrain. The mountains

also contain abundant deposits of mineral ores, in-

cluding copper, iron, zinc, lead, silver, and gold.

There are also large deposits of salt, borax, and ob-

sidian, as well as volcanic tufa stone, which is used

for construction.

Armenia’s mountains give rise to numerous

rivers, practically all unnavigable, which have cre-

ated deep gorges, ravines, and waterfalls. The

longest is the Arax River, which starts in the moun-

tains of western Armenia, joins the Kur River, then

empties into the Caspian Sea. The Arax flows

through the plain of Ararat, which is the site of

the major Armenian cities. Another important river

is the Euphrates, which splits into western and

ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS

76

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

eastern branches. Both branches flow westward,

then turn south toward Mesopotamia. The Eu-

phrates was the ancient boundary dividing what

became Lesser and Greater Armenia. The Kur and

the Tigris and their tributaries flow briefly through

Armenia. Two other rivers, the Akhurian, a tribu-

tary of the Arax, and the Hrazdan, which flows

from Lake Sevan, provide water to an otherwise

parched and rocky landscape devoid of forests.

A number of lakes are situated in the Armen-

ian highlands, the deepest and most important of

which is Lake Van in present-day Turkey. Van’s

waters are charged with borax, and hence un-

drinkable. Lake Sevan is the highest in elevation,

lying some 6,300 feet (1,917 meters) above sea

level. It is found in the present-day Armenian Re-

public.

Armenia lies in the temperate zone and has a

variety of climates. In general, winters are long and

can be severe, while summers are usually short and

very hot. Some of the plains, because of their lower

altitudes, are better suited for agriculture, and have

fostered population centers throughout the cen-

turies. The variety of temperatures has enabled the

land to support a great diversity of flora and fauna

common to western Asia and Transcaucasia. The

generally dry Armenian climate has necessitated ar-

tificial irrigation throughout history. The soil,

which is volcanic, is quite fertile and, with suffi-

cient water, is capable of intensive farming. Farm-

ing is prevalent in the lower altitudes, while sheep

and goat herding dominates the highlands.

Although Armenians have been known as ar-

tisans and merchants, the majority of Armenians,

until modern times, were engaged primarily in

agriculture. In addition to cereal crops, Armenia

grew vegetables, various oil seeds, and especially

fruit. Armenian fruit has been famous from an-

cient times, with the pomegranate and apricot, re-

ferred to by the Romans as the Armenian plum,

being the most renowned.

THE EARLIEST ARMENIANS

According to legend, the Armenians are the de-

scendants of Japeth, a son of Noah, who settled in

the Ararat valley. This legend places the Armeni-

ans in a prominent position within the Biblical tra-

dition. In this tradition, the Armenians, as the

descendants of Noah (the “second Adam”) are like

the Jews, chosen and blessed by God. Greek histo-

rians, writing centuries after the appearance of the

Armenians in their homeland, have left other ex-

planations of the origins of the Armenian people.

Two of the most quoted versions are provided by

Herodotus, the fifth century

B

.

C

.

E

. historian, and

Strabo, the geographer and historian writing at the

end of the first century

B

.

C

.

E

. According to

Herodotus, the Armenians had originally lived in

Thrace, from where they crossed into Phrygia, in

Asia Minor. They first settled in Phrygia, and then

gradually moved west of the Euphrates River to

what became Armenia. Their language resembled

that of the Phrygians, while their names and dress

was close to the Medes.

According to Strabo, the Armenians came from

two directions: one group from the west, or Phry-

gia; and the other from the south, or the Zagros

region. In other words, according to the ancient

Greeks, the Armenians were not the original in-

ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS

77

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Mt. Aragats

13,419 ft.

4090 m.

S

E

R

C

A

U

C

A

S

U

S

M

T

S

.

V

o

r

o

t

a

n

A

r

p

a

A

r

a

s

A

r

p

a

H

r

a

z

d

a

n

A

r

a

s

Sevana

Lich

Kirovakan

Kumayri

Yerevan

Alaverdi

Dilijan

Akhta

Martuni

Hoktemberyan

Igdir

Artashat

Garni

Ararat

Sisian

Kälbäjär

Basargech'ar

Khovy

Goris

Shakhbus

Ghap'an

Meghri

Kamo

Zod

Arzni

Ejmiatsin

Kalinino

Step'anavan

Ijevan

Tovuz

Akstafa

AZERBAIJAN

GEORGIA

IRAN

TURKEY

AZERBAIJAN

Armenia

W

S

N

E

ARMENIA

75 Miles

0

0

75 Kilometers

25 50

25 50

Nagorno-Karabakh

boundary

Armenia, 1992 © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH

PERMISSION

habitants of the region. They appear to have ar-

rived sometime between the Phrygian migration to

Asia Minor that followed the collapse of the Hittite

Empire in the thirteenth century

B

.

C

.

E

., and the

Cimmerian invasion of the Kingdom of Urartu (ex-

isted ca. 900–590

B

.

C

.

E

.) in the eighth century

B

.

C

.

E

.

In 782

B

.

C

.

E

., the Urartian king, Argishti I, built

the fortress-city of Erebuni (present-day Erevan,

capital of Armenia). The decline of Urartu enabled

the Armenians to establish themselves as the pri-

mary occupants of the region. Xenophon, who

passed through Armenia in 401

B

.

C

.

E

., recorded

that, by his time, the Armenians had absorbed most

of the local inhabitants.

THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE

Modem archeological finds in the Caucasus and

Anatolia have presented sketchy and incomplete ev-

idence of the possible origins of the Armenians. Un-

til the 1980s, scholars unanimously agreed that the

Armenians were an Indo-European group who ei-

ther came into the area with the proto-Iranians

from the Aral Sea region, or arrived from the

Balkans with the Phrygians after the fall of the Hit-

tites. Some scholars maintain that Hay or Hai (pro-

nounced high), the Armenian word for “Armenian,”

is derived from Hai-yos (Hattian). Hence, it is ar-

gued, the Armenians adopted the name of that em-

pire as their own during their migration over Hittite

lands. Others maintain that the Armeno-Phrygians

crossed into Asia Minor, took the name Muskhi,

and concentrated in the Arme-Shupria region east

of the Euphrates River, where non-Indo-European

words became part of their vocabulary. They

stayed in the region until the Cimmero-Scythian

invasions altered the power structure. The Arme-

nians then managed to consolidate their rule over

Urartu and, in time, assimilated most of its origi-

nal inhabitants to form the Armenian nation. Ac-

cording to this theory, the names designating

Armenia and Armenians derive from the Perso-

Greek: Arme-Shupria.

More recent scholarship offers yet another

possibility—that the Armenians were not later im-

migrants, but were among the original inhabitants

of the region. Although this notion gained some

credibility since the mid-1980s, there remain a

number of unresolved questions: What was the

spoken language of the early Armenians? Are the

Armenians members of a non-Indo-European, Cau-

casian-speaking group who later adopted an Indo-

European dialect, or are they, as many believe, one

of the native Indo-European speaking groups? A

number of linguists maintain that the Armenians,

whom they identify with the Hayasa, together

with the Hurrians, Kassites, and others, were in-

digenous Anatolian or Caucasian people who lived

in the region until the arrival of the Indo-Europeans.

The Armenians adopted some of the vocabulary of

these Indo-European arrivals. This theory explains

why Armenian is a unique branch of the Indo-

European language tree and may well explain the

origin of the word Hayastan (“Armenia” in the Ar-

menian language). As evidence, these scholars point

to Hurrian suffixes, the absence of gender, and

other linguistic data. Archeologists add that the im-

ages of Armenians on a number of sixth-century

Persian monuments depict physical features simi-

lar to those of other people of the Caucasus.

Other scholars, also relying on linguistic evi-

dence, believe that Indo-European languages may

have originated in the Caucasus and that the Ar-

menians, as a result of pressure from large empires

such as the Hittite and Assyrian, merged with

neighboring tribes and adopted some of the Semitic

and Kartvelian vocabulary and legends. They even-

tually formed a federation called Nairi, which be-

came part of the united state of Urartu. The decline

and fall of Urartu enabled the Armenian compo-

nent to achieve predominance and, by the sixth cen-

tury

B

.

C

.

E

., establish a separate entity, which the

Greeks and Persians, the new major powers of the

ancient world, called Armenia.

Further linguistic and archeological studies

may one day explain the exact origins of the Indo-

Europeans and that of the Armenian people. As of

the early twenty-first century, Western historians

maintain that Armenians arrived from Thrace and

Phrygia, while academics from Armenia argue in

favor of the more nationalistic explanation; that is,

Armenians are the native inhabitants of historic

Armenia.

CENTURIES OF CONQUERORS

Located between East and West, Armenians from

the very beginning were frequently subject to inva-

sions and conquest. The Armenians adopted features

of other civilizations, but managed to maintain

their own unique culture. Following the demise of

Urartu, Armenia was controlled by the Medes, and

soon after became part of the Achaemenid Empire

of Persia. The word Armenia is first mentioned as

Armina on the Behistun Rock, in the Zagros Moun-

tains of Iran, which was inscribed by Darius I in

about 520

B

.

C

.

E

. Armenia formed one of the Per-

ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS

78

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

sian satrapies governed by the Ervandids (Oron-

tids). Alexander the Great’s conquest of Persia en-

abled the Ervandids to become autonomous and to

resist the Seleucids. The Roman defeat of the Se-

leucids in 190

B

.

C

.

E

. encouraged Artahses, a gen-

eral of the Ervandids, to take over the land and

establish the first Armenian dynasty, the Artash-

esid (Artaxiad). in 189

B

.

C

.

E

.

The Artashesids faced Rome to the west and

Parthia to the east. During the first century

B

.

C

.

E

.,

when both powers were otherwise engaged, Arme-

nia, with the help of Pontus, managed to extend its

territory and for a short time, under Tigranes the

Great, had an empire stretching from the Caspian to

the Mediterranean. By the first century of the com-

mon era, however, the first Armenian dynasty came

to an end, and Armenia fell under successive Roman

and Parthian rule. The struggle between Rome and

Parthia to install their own government in Armenia

was finally settled by the peace of Rhandeia, in 64

C

.

E

. The brother of the Persian king became king of

Armenia, but had to travel to Rome and receive his

crown from Nero. Originally Parthian, the Ar-

shakids (Arsacids) became a distinctly Armenian dy-

nasty. During their four-century rule, Armenia

became the first state to adopt Christianity and de-

veloped its own, unique alphabet.

The accession of the Sasanids in Persia posed

new problems for Armenia. The Sasanids sought a

revival of the first Persian Empire. They eradicated

Hellenism and established Zoroastrianism as a state

religion. The Sasanids not only attacked Armenia,

but also fought Rome. By 387, the two powers par-

titioned Armenia. Four decades later, the second Ar-

menian dynasty came to an end. Another partition

occurred between Persia and the eastern Roman

Byzantine empire (Byzantium) in 591. Armenia

was ruled by local magnates who answered to Per-

sian or Byzantine governors. Despite all this, Ar-

menians not only maintained their national

character, but also produced major historical and

religious works and translations. Their church sep-

arated itself from Rome and Constantinople and as-

sumed a national character under its supreme

patriarch, the catholicos.

The advent of Islam and the arrival of the Arabs

had a major impact on Armenia. The Arabs soon

accepted a new Armenian dynasty, the Bagratids,

who ruled parts of Armenia from 885 to 1045.

Cities, trade, and architecture revived, and a branch

of the Bagratids established the Georgian Bagratid

house, which ruled parts of Georgia until the nine-

teenth century. The Bagratids, the last Armenian

kingdom in historic Armenia, finally succumbed to

the Byzantines, who under the Macedonian dy-

nasty had experienced a revival and incorporated

Armenia into their empire. By destroying the Ar-

menian buffer zone, however, the Byzantines had

to face the Seljuk Turks. In 1071, the Turks de-

feated the Byzantines in the battle of Manzikert and

entered Armenia.

The Turkish invasion differed in one significant

respect from all other previous invasions of Arme-

nia: The Turkish nomads remained in Armenia and

settled on the land. During the next four centuries,

the Seljuk and the Ottoman Turks started the Turk-

ification of Anatolia. The Armenians and Greeks

slowly lost their dominance and became a minority.

Emigration, war, and forced conversions depleted the

Anatolian and Transcaucasian Christian population.

Mountainous Karabagh, Siunik (Zangezur), Zeitun,

and Sasun peoples, and a few other pockets of set-

tlement were the only regions where an Armenian

nobility and military leaders kept a semblance of

autonomy. The rest of the Armenian population,

mostly peasants, lived under Turkish or Kurdish

rule. A number of Armenian military leaders who

had left for Byzantium settled in Cilicia. The arrival

of the Crusaders enabled these Armenians to estab-

lish a kingdom in 1199. This kingdom became a cen-

ter of east-west trade and, thanks to the Mongol

campaigns against the Muslims, lasted until 1375,

when the Egyptian Mamluks overrun the region.

From then until 1918, historic Armenia was first di-

vided between the Persians and Ottomans, and then

between the Ottomans and Russians. Although Ar-

menian diasporas were established in western Eu-

rope, South Asia, and Africa, the largest and most

influential communities rose in the major cities of

the Ottoman, Persian, and Russian empires.

ARMENIANS IN TURKEY AND RUSSIA

Following the Russian conquest of Transcaucasia,

the Armenians in Russia adopted Western ideas and

began their national and political revival. Soon af-

ter, the Armenians in Turkey also began a cultural

renaissance. Armenians in Baku and Tiflis (Tbilisi)

wielded economic power, and Armenians in Moscow

and St. Petersburg associated with government of-

ficials. Armenian political parties emerged in the last

two decades of the nineteenth century. Beginning as

reformist groups in Van (Turkey), the Armenians

soon began to copy the programs of the Russian

Social Democratic Labor Party and the Russian Pop-

ulists (Narodniks), the Hnchakian Social Democratic

ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS

79

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Party, and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

(Dashnaktsutiun).

Armenian political activities angered both the

Russians and the Turks. The Russians issued a de-

cree in 1903 which confiscated the property of the

Armenian Church. They arrested and executed

some leaders and began a general Russification pro-

gram. The Armenian armed response and the 1905

revolution abrogated the decree. Meanwhile, the

Turkish sultan Abdul-Hamid II ordered Armenian

massacres from 1895 to 1896. Armenian hopes

were raised when, in 1908, the Young Turks over-

threw the sultan and promised a state where all

citizens would be equal. Unfortunately, the Young

Turks became increasingly nationalistic. Pan-

Islamism and Pan-Turkism, combined with

chauvinism and social Darwinism, eroded the

Armeno-Turkish cooperation. The defeat of the

Turkish army in the winter campaign of 1914 and

1915 gave them the excuse to rid Turkish Arme-

nia of its Armenian population. Some 1.5 million

Armenians perished in the first genocide of the

twentieth century. The small number of survivors,

mostly women and children, managed to reach

Syria or Russia.

The Russian revolution and civil war initially

established a Transcaucasian Federated Republic in

1918. On May 26 of that year, however, Georgia,

under German protection, pulled out of the feder-

ation. Azerbaijan, under Turkish protection, fol-

lowed the next day. On May 28, Armenia was

forced to declare its independence. The small, back-

ward, and mountainous territory of Yerevan Gu-

bernya housed the new nation. Yerevan, with a

population of thirty thousand, was one-tenth the

size of Tiflis or Baku. It had no administrative, eco-

nomic, or political structure. The affluent Armeni-

ans all lived outside the borders of the new republic.

A government composed of Dashnak party mem-

bers controlled the new state.

Armenia was immediately attacked by Turkey,

but resisted long enough for World War I to end.

The republic also had border disputes over historic

Armenian enclaves that had ended up as parts of

Georgian and Azerbaijani republics. Despite a block-

ade, terrible economic and public health problems,

and starvation, the Armenians hoped that the Al-

lied promises for the restoration of historic Arme-

nia would be carried out. The Allies, however, had

their own agenda, embodied in the Sykes-Picot

Agreement. Armenia was forgotten in the peace

conferences that divided parts of the Ottoman Em-

pire between the French and the British. Although

the United States, led by President Woodrow Wil-

son, tried its best to help Armenia, the American

mandate did not materialize. Armenia was invaded

by both republican Turkey, under the leadership of

Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk), and by the Bolsheviks.

In December 1920, it became a Soviet state.

ARMENIA UNDER THE SOVIETS

Bolshevik rule began harshly for Armenia. Ar-

menian political leaders were either arrested or fled

to Iran. Not only did Karabagh and Ganja remain

part of Azerbaijan, but Nakhichevan, which had al-

ways been part of Persian and Russian Armenia,

together with the adjoining district of Sharur, was

handed over to Azerbaijan as well. The Armenian

regions of Akhalkalaki remained part of Georgia.

Armenian regions of Kars and Ardahan, captured

by Russia in 1878, were returned to Turkey. As a

final slap, Mt. Ararat, which had never been part

of Turkish Armenia, was given to Turkey. Arme-

nia thus became the junior member of the Soviet

Transcaucasian Federation.

The history of Soviet Armenia paralleled that

of the Soviet Union. Armenians experienced the

harshness of war communism, and breathed a sigh

of relief during the years of New Economic Policy

(NEP). Mountainous Karabakh, with its predomi-

nantly Armenian population, was accorded auton-

omy within Azerbaijan. Nakhichevan, separated

from Azerbaijan by Zangezur, remained part of the

constituent republic of Azerbaijan, but as an au-

tonomous republic.

The task of the Armenian communists was to

build a new Armenia that would attract immi-

grants from Tiflis, Baku, and Russia and thus

compete with the large Armenian diaspora. Mod-

ernization meant urbanization. The small, dusty

town of Yerevan was transformed into a large city

that, by 1990, had more than one million inhabi-

tants. Armenia, which had had primarily an agri-

cultural economy, was transformed into an

industrial region. Antireligious propaganda was

strong, and women were encouraged to break the

male domination of society. Ancient traditions were

ignored and the new order praised. The idea of ko-

renizatsiia (indigenization) enabled Armenian com-

munists to defend Armenian national aspirations

within the communist mold. Like their counter-

parts in other national republics, Armenian leaders

were purged by Josef Stalin and Lavrenti Pavlovich

Beria between 1936 and 1938. Beria installed his

protege, Grigor Arutiunov, who ruled Armenia un-

til 1953.

ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS

80

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The so-called Thaw begun under Nikita Khrush-

chev (1953–1964) benefited Armenia. Anastas

Mikoyan came to Armenia to rehabilitate a number

of Armenian authors and to signal the end of the

Stalin era. After 1956, therefore, Armenians built

new cadre of national leaders and were empowered

to run their local ministries. For the next thirty-five

years, Armenia was ruled by only four heads of

state. Armenian industrial output surpassed that of

Georgia and Azerbaijan. Seventy percent of Armeni-

ans lived in urban centers, and more than 80 per-

cent had a secondary education or higher, making

them one of the best educated groups in the USSR,

along with the Jews and ethnic Russians.

Armenians vastly outnumbered all other eth-

nic groups living in their republic, comprising 98

percent of the population. Ironically, however, Ar-

menians also had the largest numbers living out-

side their republic. More than 1.5 million lived in

the other Soviet republics, and more than 2.5 mil-

lion had participated in the diaspora. After the Jews,

Armenians were the most dispersed people in the

USSR. A million lived in Georgia and Azerbaijan

alone.

The two decades of the Leonid Brezhnev era were

years of benign neglect that enabled the Armenian

elite to become more independent and nationalistic

in character. Removed from the governing elite, Ar-

menian dissident factions emerged to demand ma-

jor changes. They even managed to remove the

Armenian Communist chief, Anton Kochinian, on

charges of corruption, and replaced him with a new

leader, Karen Demirjian. Ironically, much of the dis-

sent was not directed against the Russians, but

against the Turks and the Azeris. Russia was viewed

as a traditional friend, the one power that could re-

dress the wrongs of the past and reinstate Arme-

nia’s lost lands. Since Armenian nationalism did not

threaten the USSR, the Armenians were permitted,

within reason, to flourish. The fiftieth anniversary

of the Armenian genocide (1965) was commemo-

rated in Armenia and a monument to the victims

was erected. The status of Karabakh was openly dis-

cussed. Armenian protests shelved the idea, proposed

during the 1978 revision of the Constitution of the

USSR, of making Russian the official language of all

republics.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika

had a major impact on Armenia. Russia anticipated

problems in the Ukraine and the Baltic states, but

no one predicted the great eruption of Armenian

nationalism, primarily over Karabakh. On Febru-

ary 28, 1988, the Karabakh Soviet passed a reso-

lution for the transference of Karabakh to Arme-

nia. Gigantic peaceful demonstrations followed in

Yerevan. The Azeris reacted by carrying out

pogroms against the Armenians in Azerbaijan. Gor-

bachev’s inaction soured Russo-Armenian rela-

tions, and dissident leaders, known as the Karabakh

Committee, gained credibility with the public.

In May 1988, Demirjian was replaced by Suren

Harutiunian, who promised to take the Karabakh

issue to the Supreme Soviet. Moscow rejected the

transfer, and a crackdown began in Karabakh and

Yerevan. The terrible earthquake of December 7,

1988, Moscow’s inept handling of the crisis, and

Azeri attacks upon Karabakh resulted in something

extraordinary. Armenians, the most pro-Russian of

all ethnic groups, demanded independence. Haru-

tiunian resigned, and after declaring its intent to

separate from the USSR, the Armenian National

Movement, under the leadership of Levon Ter-

Petrossian, a member of the Karabakh Committee,

assumed power in Armenia. On September 21,

1991, the Armenian parliament unanimously de-

clared a sovereign state outside the Soviet Union

and two days later, on September 23, Armenia de-

clared its independence.

INDEPENDENT, POST-SOVIET ARMENIA

On October 16, 1991, barely a month after inde-

pendence, Armenians went to the polls. Levon Ter-

Petrossian, representing the Armenian National

Movement (ANM), won 83 percent of the vote. Nei-

ther the Dashnaks nor the Communists could ac-

cept their defeat and, ironically, they found common

cause against Levon Ter-Petrossian’s government.

Receiving a clear mandate did not mean that

the government of Levon Ter-Petrossian would be

free from internal or external pressures. The ma-

jor internal problem was the virtual blockade of Ar-

menia by Azerbaijan, exacerbated by the plight of

the hundreds of thousands of Armenian refugees

from Azerbaijan and the earthquake zone. Other

domestic issues involved the implementation of

free-market reforms, the establishment of democ-

ratic governmental structures, and the privatiza-

tion of land. The external concerns involved future

relations with Russia, Turkey, Georgia, and Iran.

The immediate concern, however, was the conflict

with Azerbaijan over mountainous Karabakh and

the political uncertainties in Georgia, which con-

tained 400,000 Armenians.

Ter-Petrossian attempted to assure Turkey that

Armenia had no territorial claims against it and

ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS

81

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

that it desired neighborly diplomatic and economic

relations. Rather than espousing an ideologically

dogmatic and biased outlook, Armenia was to have

a pragmatic and flexible foreign policy. In the long

run, however, Armenian efforts to establish polit-

ical and economic relations with Turkey did not

materialize. The Turks not only maintained their

blockade of Armenia, but also insisted that the is-

sue of Karabakh had to be resolved before anything

else could be discussed. The Azeri blockade had re-

sulted in food and fuel shortages and, since 1989,

had virtually halted supplies for earthquake recon-

struction. The closing down of the Medzamor Nu-

clear Energy Plant in 1989 meant that Armenian

citizens, including the many refugees, would have

to face many difficult winters.

The presidential election of 1996 was marred by

accusations of fraud. A broad coalition supported

Vazgen Manoukian, the candidate of the National

Democratic Union, but the election results gave Ter-

Petrossian a victory with 51 percent of the vote. The

opposition accused the ruling party of massive frauds

in the counting of the ballots. Foreign observers cited

some irregularities, but concluded that these did not

significantly affect the outcome. Continued rallies,

riots, and some shootings resulted in arrests and the

ban on all public gatherings for a short time. By early

1998, a major split over Karabakh had occurred be-

tween Levon Ter-Petrossian and members of his own

cabinet. Prime Minister Robert Kocharian, Defense

Minister Vazgen Sargisian, and the Interior and Na-

tional Security Minister Serge Sargisian joined forces

against the president, who was forced to resign.

Kocharian succeeded him.

The parliamentary elections of May 1999 re-

shaped the balance of power. The Unity Coalition,

led by Vazgen Sargisian, and the People’s Party of

Armenia, led by Karen Demirjian, won the elections

and left Kocharian without any control over the

parliamentary majority. Sargisian became prime

minister, and Demirjian became the speaker of Par-

liament. They removed Serge Sargisian, a Karabakhi

and Kocharian’s closest ally, from his post of min-

ister of the interior. Karen Demirjian, meanwhile,

became the speaker of Parliament. But on October

27, five assassins entered the building of the Na-

tional Assembly of Armenia and killed Sargisian and

Demirjian, as well as two deputy speakers, two

ministers, and four deputies. With the government

in the hands of Kocharian, the economy at a stand-

still, and the Karabakh conflict unresolved, Arme-

nians by the tens of thousands voted with their feet

and emigrated from the country.

See also: ARMENIAN APOSTOLIC CHURCH; AZERBAIJAN

AND AZERIS; CAUCASUS; DASHNAKTSUTIUN; NATION-

ALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

TSARIST; NAGORNO-KARABAKH; TER-PETROSSIAN,

LEVON

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bournoutian, George A. (1992). The Khanate of Erevan

under Qajar Rule, 1795–1828. Costa Mesa, CA:

Mazda Press.

Bournoutian, George A. (1994). A History of Qarabagh.

Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Press.

Bournoutian, George A. (1998). Russia and the Armeni-

ans of Transcaucasia: 1797–1889. Costa Mesa, CA:

Mazda Press.

Bournoutian, George A. (1999). The Chronicle of Abraham

of Crete. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Press.

Bournoutian, George A. (1999). History of the Wars:

1721–1738. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Press.

Bournoutian, George A. (2001). Armenians and Russia:

1626–1796. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Press.

Bournoutian, George A. (2002). A Concise History of the

Armenian People. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Press.

Bournoutian, George A. (2002). The Journal of Zak’aria

of Agulis. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Press.

Hovannisian, Richard. G. (1967). Armenia on the Road to

Independence, 1918. Berkeley: University of Califor-

nia Press.

Hovannisian, Richard. G. (1971–1996). The Armenian Re-

public. 4 vols. Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Libaridian, Gerard. (1991). Armenia at the Crossroads. Wa-

tertown, MA: Blue Crane Publishing.

Libaridian, Gerard. (1999). The Challenge of Statehood.

Watertown, MA: Blue Crane Publishing.

Matossian, Mary Allerton Kilbourne. (1962). The Impact

of Soviet Policies in Armenia. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Nalbandian, Louise. (1963). The Armenian Revolutionary

Movement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Suny, Ronald Grigor. (1993). Looking toward Ararat.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

G

EORGE

A. B

OURNOUTIAN

ARMENIAN APOSTOLIC CHURCH

The Armenian Apostolic Church has a long and an-

cient history. Its received tradition remembers the

apostolic preaching of Saint Bartholomew and Saint

Thaddeus among the Armenians of Edessa and sur-

ARMENIAN APOSTOLIC CHURCH

82

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY