Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

rounding territories. It is likely that there were Ar-

menian Christians from early times, such that Saint

Gregory the Illuminator, in the fourth century,

who worked among people who had previous con-

tact with Christianity. The Armenian Church cel-

ebrates the year 301 as the time when Gregory

converted King Trdat. The king, in turn, made

Christianity the state religion. There is disagree-

ment among scholars about this date. It should also

be remembered that the idea of Christianity as state

religion was an innovation at that time.

Events of the fifth century were critical to the

making of a distinctively Armenian Christian cul-

ture and identity. The foremost of these was the

invention of the Armenian alphabet by the monk

Mesrob Mashtots and his community. Translations

of scripture, commentaries, liturgy, theology, and

histories were made. Greek and Syriac literature

were important sources. In addition, the fifth cen-

tury witnessed the first flowering of original Ar-

menian literature. An example is Eznik Koghbatsi’s

doctrinal work, Refutation of the Sects. The Battle of

Avarayr in 451 against Persia, although a defeat

for the Armenians under Vartan, has been re-

membered as critical for winning the Armenians

the right to practice their Christian belief.

The fact that the Armenians eventually rejected

the Christology of the Council of Chalcedon (451)

has defined their communion with the Oriental Or-

thodox churches and their schism from the Or-

thodox churches that grew out of Constantinople

(that is, the Orthodox churches of the Greeks, Geor-

gians, and Russians, among others). The dispute

concerned the way in which the natures of Christ

were properly described. The Armenian Church be-

lieved that the language of Chalcedon, defining the

person of Jesus Christ as “in two natures,” de-

stroyed the unity of divinity and humanity in

Christ.

Throughout much of its history, the Armen-

ian Orthodox Church has been an instrument of

the Armenian nation’s survival. The head of the

church, called catholicos, has been located in vari-

ous Armenian cities, often in the center of political

power. In the early twenty-first century the

supreme catholicos is located in the city of Echmi-

adzin, near the Armenian capital, Yerevan. Another

catholicos, descended from the leaders of Sis in Cili-

cia, is located in Lebanon. During the existence of

Cilician Armenia (from the eleventh to fourteenth

centuries), when Crusaders were present in the

Middle East, the Armenian Church had close ties

with Rome. Nerses Shnorhali, known as “the

Graceful” (1102–1173), was an important catholi-

cos of this period.

The Armenian Church played a significant role

in the succession of Muslim empires in which its

faithful were located. Because some of these were

divided according to religious affiliation, the lead-

ers of the Armenian were, in fact, also politically

responsible for their communities. The Armenian

Church was greatly affected by two phenomenon

in the twentieth century: the genocide in Turkey,

in which 1.5 million died, and the Sovietization of

eastern Armenia, which ushered in seven decades

of official atheism. The genocide essentially de-

stroyed the church in Turkey, where only a rem-

nant remains. It has also profoundly affected the

way in which the Armenian Church approaches the

idea of suffering in this world.

The church thrived in many parts of the Ar-

menian diaspora, and is regaining its strength in

newly independent Armenia. In the post-Soviet pe-

riod, the church has struggled to define itself in

society, having to overcome the decades of perse-

cution and neglect, as well as making adjustments

in a political culture in which it is favored but must

still coexist in an officially pluralistic society.

The liturgy of the Armenian Church (the eu-

charistic service is called patarag) with Syriac

and Greek roots, has been vastly enriched by the

hymnody of Armenian writers. Contact with

Rome has also been important in this context. Ar-

menians, preserving an ancient Eastern tradition,

celebrate Christmas and Epiphany together on Jan-

uary 6.

See also: ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS; ORTHODOXY; RELI-

GION; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Maksoudian, Krikor (1995). Chosen of God: The Election of

the Catholicos of All Armenians. New York: St. Var-

tan’s Press.

Ormanian, Malachia. (1988). The Church of Armenia: Her

History, Doctrine, Rule, Discipline, Liturgy, Literature,

and Existing Conditions. New York: St. Vartan’s

Press.

P

AUL

C

REGO

ARMENIAN REVOLUTIONARY FEDERATION

See DASHNAKTSUTIUN.

ARMENIAN REVOLUTIONARY FEDERATION

83

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ARMORY

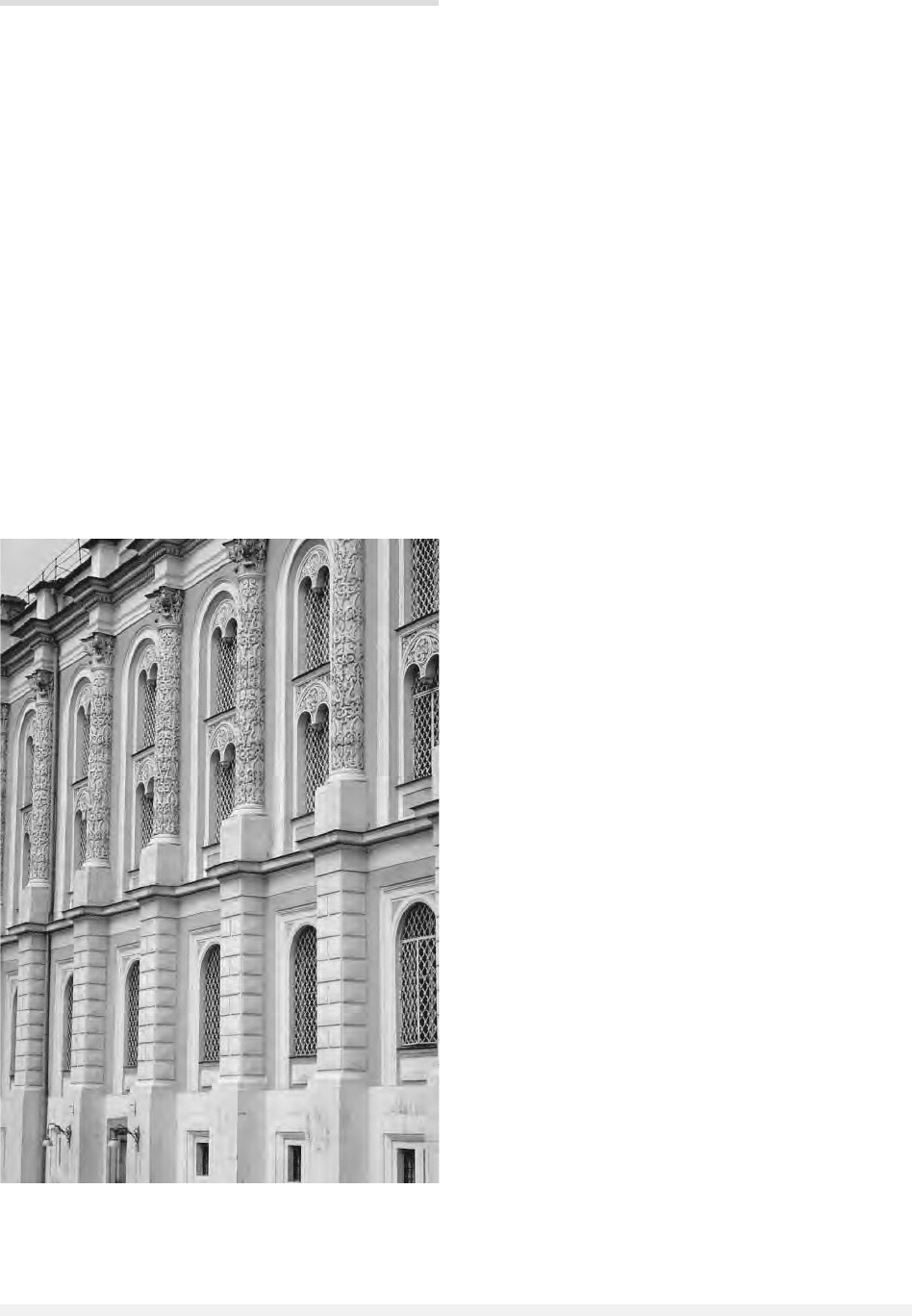

The Armory (Oruzheinaia palata) was a Muscovite

state department that organized the production of

arms, icons, and other objects for the tsars and their

household; later it became a museum.

An Armory chancery (prikaz) was established

in the Moscow Kremlin at the beginning of the six-

teenth century to supervise the production and

storage of the tsars’ personal weapons and other

objects, such as saddles and banners. By the mid-

dle of the seventeenth century, it encompassed a

complex of studios, including the Gold and Silver

Workshops and the Armory Chamber itself, which

employed teams of craftsmen to produce a wide

variety of artwork and artifacts and also stored and

maintained items for the palace’s ceremonial and

liturgical use and for distribution as gifts. The

chancery commanded considerable funds and a

large administrative staff, presided over by such

leading boyars as Bogdan Khitrovo, who was di-

rector of the Armory from 1654 to 1680, during

which time it emerged as a virtual academy of arts.

From the 1640s onward, the Armory had ded-

icated studios for icon painting and, beginning in

1683, for nonreligious painting. Its most influen-

tial artist was Simon Ushakov (1626–1686), whose

images demonstrate a mixture of traditional com-

positions and more naturalistic use of light, shade,

and perspective. Characteristic examples include his

icons “The Planting of the Tree of the Muscovite

Realm” (1668) and “Old Testament Trinity” (1671).

He also made charts and engravings and painted

portraits. The development of portrait painting

from life by artists such as Ivan Bezmin and Bog-

dan Saltanov was one of the Armory’s most strik-

ing innovations, although surviving works show

the influence of older conventions of Byzantine im-

perial portraits and Polish “parsuna” portraits,

rather than contemporary Western trends. Teams

of Armory artists also restored and painted fres-

coes in the Kremlin cathedrals and the royal

residences: for example, in the cathedrals of the

Dormition (1632–1643) and Archangel (1652).

Russian Armory artists worked alongside for-

eign personnel, including many from the Grand

Duchy of Lithuania, who specialized in woodcarv-

ing, carpentry, and ceramics. Other foreigners

worked as gunsmiths and clock- and instrument-

makers. A handful of painters from western

Europe encouraged the development of oil painting

on canvas and introduced new Biblical and histor-

ical subjects into the artistic repertoire. By the late

1680s secular painters began to predominate: Ar-

mory employment rolls for 1687–1688 record

twenty-seven icon painters and forty secular

painters. Nonreligious painting assignments in-

cluded making maps, charts, prints and banners,

and decorating all manner of objects, from painted

Easter eggs and chess sets to children’s toys. Un-

der the influence of Peter I (r. 1682–1725) and his

circle, in the 1690s artists were called upon to un-

dertake new projects, such as decorating the ships

of Peter’s new navy and constructing triumphal

arches. In the early eighteenth century Peter trans-

ferred many Armory craftsmen to St. Petersburg,

and by 1711 the institution was virtually dissolved,

surviving only as a museum and treasury. From

1844 to 1851 the architect Karl Ton designed the

present classical building, which houses and dis-

plays Muscovite and Imperial Russian regalia and

treasures, vestments, carriages, gifts from foreign

delegations, saddles, and other items.

ARMORY

84

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Partial view of the Kremlin Armory in Moscow. © W

OLFGANG

K

AEHLER

/CORBIS

See also: CATHEDRAL OF THE ARCHANGEL; CATHEDRAL OF

THE DORMITION; ICONS; KREMLIN; PETER I; USHAKOV,

SIMON FYODOROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cracraft, James. (1997). The Petrine Revolution in Russian

Imagery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1979). “The Moscow Armoury and

Innovations in Seventeenth-Century Muscovite Art.”

Canadian-American Slavic Studies 13:204–223.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

ARMS CONTROL

Russia’s governments—tsarist, Soviet, and post-

Soviet—have often championed arms limitation.

Power and propaganda considerations as well as

ideals lay behind Russian and Soviet proposals. Be-

cause Russia and the USSR usually lagged behind

its Western adversaries in military technology and

economic strength, Russian leaders often called for

banning new weapons or abolishing those they

did not yet possess. Russia sought to bring the

weapons of all countries to the same qualitative

level. If that happened, Russia’s large size would

permit it to field larger armies than its rivals. By

contrast, the United States often led the world in

military technology and economic strength. Ac-

cordingly, U.S. diplomats often called for freezing

the existing military balance of power so that the

United States could maintain its advantages. Such

measures, if implemented, would often have put

Russia at a disadvantage.

FUNDAMENTAL BARRIERS

TO DISARMAMENT

Besides its large size, Russia had the advantage of

secrecy. Both tsars and commissars exploited the

closed nature of their society to hide weaknesses

and assets. With its open society, the United States

had fewer secrets to protect, so it advocated arms

treaties that permitted onsite inspection. The usual

pattern was that the United States wanted inspec-

tion first; disarmament later. The Soviets wanted

disarmament first; inspection later, if ever.

Language differences magnified these difficul-

ties. While English has just one word for disarma-

ment, Russian has two, and thus distinguishes

between voluntary and coerced disarmament. Vol-

untary disarmament, as the outcome of self-

restraint or negotiation, is razoruzhenie, whereas

disarmament by force is obezoruzhit. Vladimir Ilich

Lenin, however, believed that razoruzhenie was a

pacifist illusion. The task of revolutionaries, he ar-

gued, was to disarm its enemies by force. Soviet

diplomats began calling for wide-scale disarma-

ment in 1922. They said that Western calls for

“arms limitation”—not full razoruzhenie—masked

the impossibility for capitalist regimes to disarm

voluntarily. Soviet ideologists averred that capital-

ists needed arms to repress their proletariat, to fight

each other, and to attack the socialist fatherland.

Seeking a more neutral term, Western diplo-

mats in the 1950s and 1960s called for “arms con-

trol,” a term that included limits, reductions, and

increases, as well as the abolition of arms. But kon-

trol in Russian means only verification, counting,

or checking. Soviet diplomats said “arms control”

signified a Western quest to inspect (and count)

arms, but not a willingness actually to disarm. Af-

ter years of debate, Soviet negotiators came to

accept the term as meaning “control over arma-

ments,” rather than simply a “count of arma-

ments.” In 1987, when the USSR and United States

finally signed a major disarmament agreement,

President Ronald Reagan put the then-prevailing

philosophy into words, saying: “Veriat no proveriat”

(trust, but verify).

THE MAKING OF ARMS POLICY

A variety of ideals shaped tsarist and Soviet policy.

Alexander I wanted a Holy Alliance to maintain

peace after the Napoleonic wars. Like Alexander I,

Nicholas II wanted to be seen as a great pacifist,

and summoned two peace conferences at The

Hague in an effort to achieve that end. Lenin, how-

ever, believed that “disarmament” was a mere slo-

gan, meant only to deceive the masses into believing

that peace was attainable without the overthrow

of capitalism. When Lenin’s regime proposed dis-

armament in 1922, its deep aim was to expose cap-

italist hypocrisy and demonstrate the need for

revolution. From the late 1920s until his death in

1953, Stalin also used disarmament mainly as a

propaganda tool.

Nuclear weapons changed everything. The Krem-

lin, under Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, recognized

that nuclear war could wipe out communist as well

as noncommunist countries. Whereas Lenin and

Stalin derided “bourgeois pacifists” in the West, the

Soviet government under Khrushchev believed it must

avoid nuclear war at all costs. Sobered by the 1962

Cuban missile confrontation, Khrushchev’s regime

ARMS CONTROL

85

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

admonished the Chinese Communists in 1963: “The

atomic bomb does not respect the class principle.”

Nuclear weapons also gave Moscow confidence

that it could deter an attack. The USSR tested a nu-

clear bomb in 1953, and a thermonuclear device in

1953. By 1954, the Kremlin had planes capable of

delivering Soviet bombs to America. In 1957 the

USSR tested the world’s first intercontinental bal-

listic missile (ICBM), leading Khrushchev to claim

the Soviet factories were producing ICBMs “like

sausages.” He tried to exploit the apparent Soviet

lead in missiles to extract Western concessions in

Germany.

By 1962, increased production in the United

States had reversed the so-called missile gap. By

1972 the United States had also produced a war-

head gap, as it placed multiple warheads on ICBMs

and submarine missiles. Still, by 1972 each nuclear

superpower had overkill capability: more than

enough weapons to absorb a first-strike and still

destroy the attacker. Having ousted Khrushchev in

1964, Soviet Communist Party leader Leonid

Brezhnev signed the first strategic arms limitation

treaty (SALT I) with President Richard Nixon in

1972 and a second accord (SALT II) with President

Jimmy Carter in 1979. Each treaty essentially

sought to freeze the Soviet-U.S. competition in

strategic weapons—meaning weapons that could

reach the other country. SALT I was ratified by

both sides, but SALT II was not. The United States

balked because the treaty enshrined some Soviet ad-

vantages in “heavy” missiles and because the USSR

had just invaded Afghanistan.

The 1972 accords included severe limits on an-

tiballistic missile (ABM) defenses. Both Moscow and

Washington recognized that each was hostage to

the other’s restraint. Displeased by this situation,

President Ronald Reagan sponsored a Strategic De-

fensive Initiative (SDI, also called Star Wars) re-

search program meant to give the United States a

shield against incoming missiles. If the United

States had such a shield, however, this would

weaken the deterrent value of Soviet armaments.

The Soviets protested Reagan’s program, but at the

same time it secretly tried to expand the small ABM

system it was allowed by the 1972 treaty.

NEW TIMES, NEW THINKING

When Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev succeeded

Konstantin Chernenko as top Soviet leader in 1985,

he advocated “new thinking” premised on the need

for mutual security in an interdependent world. Be-

tween the two great powers, he said, security could

only be “mutual.” Gorbachev said Soviet policy

should proceed not from a class perspective, but

from an “all-human” one.

Gorbachev’s commitments to arms control

were less tactical and more strategic than his pre-

decessors—more dedicated to balanced solutions

that accommodated the interests of both sides of

the debate. In contrast, Khrushchev often portrayed

his “peaceful coexistence” policy as a tool in the

struggle to defeat capitalist imperialism, and Brezh-

nev demanded “coequal security” with the United

States. Gorbachev, on the other hand, initiated or

agreed to a series of moves to slow or reverse the

arms competition:

• a unilateral moratorium on underground nu-

clear testing from 1985 to 1987, with accep-

tance of U.S. scientists and seismic equipment

near Soviet nuclear test sites in Kazakhstan

• agreement in 1987 to the INF treaty, requiring

the USSR to remove more warheads and to de-

stroy more intermediate-range and shorter-

range missiles than the United States (after

which Reagan reiterated “veriat no proveriat”)

• opening to U.S. visitors in September 1987 a

partially completed Soviet radar station that,

had it become operational, would probably

have violated the 1972 limitations on ABM de-

fenses

• a pledge in December 1988 to cut unilaterally

Soviet armed forces by 500,000 men, 10,000

tanks, and 800 aircraft

• withdrawing Soviet forces from Afghanistan

by February 15, 1989

• supporting arrangements to end regional con-

flicts in Cambodia, southern Africa, the Persian

Gulf, and the Middle East

• acceptance in 1990 of a Final Settlement with

Respect to Germany setting 1994 as the dead-

line for Soviet troop withdrawal from Ger-

many

• in 1990 a Soviet-U.S. agreement to reduce their

chemical weapons stocks to no more than

5,000 tons each.

All members of NATO and the Warsaw Treaty

Organization signed the Conventional Forces in Eu-

rope (CFE) treaty in 1990. It limited each alliance

to 20,000 battle tanks and artillery pieces, 30,000

armored combat vehicles, 6,800 combat aircraft,

and 2,000 attack helicopters. In 1991, however,

members of the Warsaw Pact agreed to abolish their

alliance. Soon, Soviet troops withdrew from Poland,

ARMS CONTROL

86

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. Trying to compen-

sate for unexpected weaknesses, the USSR tried to

reclassify some military units to exempt them from

the CFE limits. NATO objected, but Soviet power

was shrinking and minor exemptions such as these

mattered little.

In 1991 Gorbachev and U.S. president George

Herbert Walker Bush signed the first Strategic Arms

Reduction Treaty (START I). It obliged Washington

and Moscow within seven years to cut their forces

by more than one-third to sixteen hundred strate-

gic delivery vehicles (ICBMs, submarine missiles,

heavy bombers) and six thousand warheads. When

the USSR dissolved later that year, the Russian Fed-

eration (RF) took the Soviet Union’s place in START

and other arms control regimes. START I became

legally binding in 1994, and each party began steps

to meet the ceilings set for seven years hence, in

2001.

In September 1991, after an attempted coup

against Gorbachev in the previous August, Presi-

dent Bush announced the unilateral elimination of

some 24,000 U.S. nuclear warheads and asked the

USSR to respond in kind. Gorbachev announced

unilateral cuts in Soviet weapons that matched or

exceeded the U.S. initiative. He also took Soviet

strategic bombers off alert, announced the deac-

tivization of 503 ICBMs covered by START, and

made preparations to remove all short-range nu-

clear weapons from Soviet ships, submarines, and

land-based naval aircraft.

POST-SOVIET COMPLICATIONS

In November 1990 the U.S. Senate had voted $500

million of the Pentagon budget to help the USSR

dismantle its nuclear weapons. In December 1991,

however, the USSR ceased to exist. Its treaty rights

and duties were then inherited by the Russian Fed-

eration (RF). However, Soviet-era weapons re-

mained not just in Russia but also in Ukraine,

Belarus, and Kazakhstan. These three governments

agreed, however, to return the nuclear warheads

to Russia. The United States helped fund and re-

ward disarmament in all four republics.

President Bush and RF President Boris Yeltsin

in 1993 signed another treaty, START II, requiring

each side to cut its arsenal by 2003 to no more

than 3,500 strategic nuclear warheads. The parties

also agreed that ICBMs could have only one war-

head each, and that no more than half the allowed

warheads could be deployed on submarines. START

II was approved by the U.S. Senate in 1996, but

ARMS CONTROL

87

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

U.S. president Richard Nixon and Soviet general secretary Leonid Brezhnev sign the SALT I Treaty in Moscow, 1972. © W

ALLY

M

C

N

AMEE

/CORBIS

the RF legislature ratified it only on condition that

the United States stand by the ABM treaty. As a

results, START II never became law. Confronted by

the expansion of NATO eastward and by deterio-

rating Russian conventional forces, Russian mili-

tary doctrine changed in the mid-1990s to allow

Moscow “first use of nuclear arms” even against a

conventional attack.

Ignoring RF objections, NATO invited three for-

mer Soviet allies to join NATO in 1999 and three

more in 2002, plus three former Soviet republics,

plus Slovenia. The Western governments argued

that this expansion was aimed at promoting

democracy and posed no threat to Russia. The RF

received a consultative voice in NATO. Following

the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on Amer-

ica, Presidents Vladimir Putin and George W. Bush

found themselves aligned against terrorism. Putin

focused on improving Russia’s ties with the West

and said little about NATO.

The RF and U.S. presidents signed the Strategic

Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT) in May 2002.

Bush wanted to reduce U.S. strategic weapons to

the level needed for a “credible deterrent,” but pre-

ferred to do so without a binding treaty. Putin also

wanted to cut these forces but demanded a formal

contract. Bush agreed to sign a treaty, but it was

just three pages long, with extremely flexible com-

mitments. START I, by contrast, ran to more than

seven hundred pages.

SORT required each side to reduce its opera-

tionally deployed strategic nuclear warheads to be-

tween 1,700 and 2,200 over the next decade, with

a target date of December 31, 2012. At the insis-

tence of the United States, the warheads did not

have to be destroyed and could be stored for pos-

sible reassembly. Nor did SORT ban multiple war-

heads—an option that had been left open because

START II had never become law. SORT established

no verification procedures, but could piggyback on

the START I verification regime until December

2009, when the START inspection system would

shut down. Putin signed SORT even though Moscow

objected to Bush’s decision, announced in 2001, to

abrogate the ABM treaty. Bush wanted to build a

national defense system, and Putin could not stop

him.

See also: COLD WAR; REYKJAVIK SUMMIT; STRATEGIC

ARMS LIMITATION TREATIES; STRATEGIC ARMS RE-

DUCTION TALKS; STRATEGIC DEFENSE INITIATIVE;

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berman, Harold J., and Maggs, Peter B. (1967). Disar-

mament Inspection and Soviet Law. Dobbs Ferry, NY:

Oceana.

Bloomfield, Lincoln P., et al. (1966). Khrushchev and the

Arms Race: Soviet Interests in Arms Control and Disar-

mamen The Soviet Union and Disarmament,1954–1964.

Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press.

Clemens, Walter C., Jr. (1968). The Arms Race and Sino-

Soviet Relations. Stanford, CA: The Hoover Institu-

tion.

Clemens, Walter C., Jr. (1973). The Superpowers and Arms

Control: From Cold War to Interdependence. Lexington,

MA: Lexington Books.

Dallin, Alexander. (1965). The Soviet Union and Disarma-

ment. New York: Praeger.

Garthoff, Raymond L. (1994). Detente and Confrontation:

American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan.

Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Kolkowicz, Roman. (1970). The Soviet Union and Arms

Control: A Superpower Dilemma. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press.

Spanier, John W., and Nogee, Joseph L. (1962). The Pol-

itics of Disarmament: A Study in Soviet-American

Gamesmanship. New York: Praeger.

W

ALTER

C. C

LEMENS

J

R

.

ARTEK

The first, largest, and most prestigious Soviet

Young Pioneer camp, Artek began life in 1925 as

a children’s sanatorium, created on the Black Sea’s

Crimean shore near Suuk-Su on the initiative of

Old Bolshevik Zinovy Soloviev, vice-commissar for

public health. Most of the early campers came for

medical treatment. Soon, however, a trip to Artek

became a reward for Pioneers who played an ex-

emplary role in various Stalinist campaigns. In

1930 the camp became a year-round facility; in

1936 the government gave it the buildings of a

nearby tsarist-era sanatorium. During World War

II, the camp was evacuated to the Altai. In 1952

Artek instituted an international session each sum-

mer, in which children from socialist countries, as

well as “democratic children’s movements” else-

where, mingled with Soviet campers. In 1958, dur-

ing Khrushchev’s campaign to rationalize the

bureaucracy, Artek was transferred from the health

ministry to the Komsomol and officially became a

school of Pioneering. The next year, architects and

ARTEK

88

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

engineers began redesigning the camp, replacing the

old buildings with prefabricated structures based

on an innovative combinatory system. The largest

resort complex ever built exclusively for children,

this New Artek, nearly the size of New York City’s

Central Park and with a staff of about 3,000, hosted

tens of thousands of children annually. It was a

workshop for teachers and adult Pioneer leaders, a

training ground for the country’s future elite, and

a font of propaganda about the USSR’s solicitous-

ness for children. After 1991, Artek, now in

Ukraine, became a private facility.

See also: COMMUNIST YOUTH ORGANIZATIONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Thorez, Paul. (1991). Model Children: Inside the Republic

of Red Scarves, tr. Nancy Cadet. New York: Autono-

media.

Weaver, Kitty. (1981). Russia’s Future: The Communist Ed-

ucation of Soviet Youth. New York: Praeger.

J

ONATHAN

D. W

ALLACE

ARTICLE 6 OF 1977 CONSTITUTION

Article 6 of the 1977 Brezhnev Constitution estab-

lished the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as

the sole legitimate political party in the country.

The Party was declared to be the “leading and guid-

ing force of Soviet society and the nucleus of its

political system, of all state organizations and pub-

lic organizations,” and it imparted a “planned, sys-

tematic, and theoretically substantiated character”

to the struggle for the victory of communism.

As Gorbachev’s reforms of glasnost, pere-

stroika, and demokratizatsiya unfolded in the late

1980s and early 1990s, interest groups became in-

creasing active, and proto-political parties began to

organize. Pressures built to revoke Article 6. Bow-

ing to these pressures and with Gorbachev’s ac-

quiescence, the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies

voted in February 1990 to amend Article 6 to re-

move the reference to the Party’s “leading role” and

prohibitions against forming competing parties.

The amended Article 6 read: “The Communist Party

of the Soviet Union [and] other political parties, as

well as trade union, youth, and other public orga-

nizations and mass movements, participate in

shaping the policies of the Soviet state and in run-

ning state and public affairs through their repre-

sentatives elected to the soviets of people’s deputies

and in other ways.” Article 7 was also amended to

specify that all parties must operate according to

the law, while Article 51 was altered to insure all

citizens the right to unite in political parties and

public organizations.

Within months of the Congress’s action amend-

ing Article 6, fledgling political parties began to reg-

ister themselves. Within one year, more than one

hundred political parties had gained official recog-

nition. The proliferation of political parties itself be-

came problematic as reformers sought to establish

stable democratic governing institutions and vot-

ers were presented with a bewildering array of

choices of parties and candidates in national, re-

gional, and local elections.

See also: CONSTITUTION OF 1977; DEMOCRATIZATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sakwa, Richard. (2001). “Parties and Organised Inter-

ests.” In Developments in Russian Politics 5, eds.

Stephen White, Alex Pravda, and Avi Gitelman. Bas-

ingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

White, Stephen. (2000). Russia’s New Politics. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

G

ORDON

B. S

MITH

ASSEMBLY OF THE LAND

Assembly of the Land is the usual translation of

the Russian Zemsky sobor, a nineteenth-century

term for a proto-parliamentary institution that

was summoned irregularly between 1564 and

1653. One of the problems of studying the As-

sembly of the Land is defining it. The contempo-

rary definition was sobor, which means “assembly”

and could refer to any group of people anywhere,

such as a church council or even an assembly of

military people. Loosely defined, sobor could include

almost any street-corner gathering in Muscovy in

the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but it will

be defined more strictly here as an assemblage called

by the tsar and having both an upper and a lower

chamber.

Some Soviet scholars, such as Lev Cherepnin,

advocated the loose definition of sobor, by which he

discussed fifty-seven assemblies between 1549 and

1683, thereby supporting the claim that Muscovy

ASSEMBLY OF THE LAND

89

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

was an “estate-representative monarchy” not much

different from contemporary central and western

European states.

The great Russian historian Vasily Klyuchevsky

initiated the view that the Assembly of the Land

should be seen in terms of a sixteenth-century and

seventeenth-century reality. In the former period

the Assembly of the Land was definitely a consul-

tative body called by the tsar when he needed ad-

vice. Delegates were rounded up from men who

happened to be in Moscow for some reason, such

as the start of a military campaign. After the col-

lapse of the country in the Time of Troubles, the

Assembly of the Land retained its former advisory

functions, but delegates (especially to the lower

chamber) sometimes were directly elected to voice

the concerns of their constituents.

The earliest ancestor of the Assembly of the

Land was an assemblage (sobor) of military figures

convoked on the eve of Moscow’s invasion of Nov-

gorod in 1471. The purpose was presumably to ad-

vise Grand Prince Ivan III about tactics for the

campaign. No one claims that this was a real As-

sembly of the Land, but it was a sobor and had mil-

itary linkages, as did many of the later real

Assemblies of the Land.

Advice was one of the major functions of the

Assembly of the Land. This role became critical af-

ter the abolition of the feeding system of provincial

administration in 1556. The feeding system’s gov-

ernors (namestniki, kormlenshchiki) served on rota-

tion in the provinces for terms of three years. While

in the provinces, they represented Moscow in mat-

ters such as tax collection and the holding of trials.

While in the countryside “feeding,” these officials

were expected to skim enough off from their re-

ceipts to support them when they returned to

Moscow. When they were not on duty in the

provinces, they were in the capital Moscow and

could be summoned by the tsar and his officials to

gain relatively fresh information about the condi-

tion of the provinces: for instance, whether the

country could afford to go to war, whether the

army was willing to fight, and so forth. With the

abolition of the feeding system, this source of in-

formation was lost. Thus it is not accidental that

in 1566 (June 25–July 5), during the period of the

Livonian War (1558–1583) when the fighting had

begun to go badly for the Muscovites, the govern-

ment rounded up and sought the advice of people

who happened to be in Moscow. They were grouped

into two chambers: The upper chamber typically

consisted of members of the upper service class (the

Moscow military elite cavalrymen) and the top

members of the church, while the lower chamber

consisted of members of the middle service class

(the provincial cavalry) and the townsmen. The

government presumed that these people understood

the fundamentals of the country: whether suffi-

cient wealth and income existed to continue the

war and whether the cavalry was able to continue

fighting.

Summary records of the first Assembly of the

Land still exist and have been published. Its mem-

bers advised the government that the country was

able to continue the war, that there was no need

to pursue peace with the Rzeczpospolita. They also

gratuitously criticized Ivan the Terrible’s paranoid

Oprichnina (1565–1572), Ivan’s mad debauch that

divided Muscovy into two parts, the Oprichnina

(run by Ivan himself) and the Zemshchina (run by

the seven leading boyars). Ivan’s servitors in the

Oprichnina, called oprichniki, looted and otherwise

destroyed nearly all the possessions they were

given. The criticism aroused Ivan to fury and led

him to launch a second, ferocious hunt for “ene-

mies.” Thus the first Assembly of the Land con-

veyed the two basic messages to the government

that were to be constants throughout the institu-

tion’s history: First, the Assembly was a quick and

relatively inexpensive way to determine the coun-

try’s condition; second, the assembled Russians

might well do things that the government would

have preferred not be done. When the consequences

of the latter outweighed the value of the former,

the institution was doomed.

The next real Assembly of the Land occurred in

1598 (February and March, July and August) for

the purpose of electing Boris Godunov as tsar on

the expiration of the seven-century-old Rurikid

dynasty. This election was probably rigged by

Boris, who had been ruling during the reign of Fy-

odor Ivanovich (1584–1598); nevertheless, the

members of the Assembly, all government agents

in one way or another, properly advised the gov-

ernment (Boris) that he (Boris, again) should be the

new tsar.

During the Time of Troubles sundry meetings

were held in 1605–1606 and in 1610, 1611, and

1612; these, by loose definitions, have been called

Assemblies of the Land, but they really were not.

In 1613, however, a real Assembly of the Land was

convoked to choose Mikhail Fyodorovich as the

new tsar, the first tsar of the Romanov dynasty,

ASSEMBLY OF THE LAND

90

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

which lasted until the February Revolution of 1917.

The cossacks constituted a new element in the lower

chamber.

Some scholars, holding to a loose definition, al-

lege that, after the election of Mikhail, Assemblies

of the Land met annually from 1614 to 1617 to

deal with taxes (especially so-called fifth taxes, 20%

levies of all wealth) needed to pay military forces

to drive out the Poles and Swedes. The tsar’s fa-

ther, Patriarch Filaret, returned to Moscow from

Polish captivity in 1619 and began to take com-

mand of the Muscovite government and to restore

the Muscovite state. Delegates were elected in Sep-

tember 1619 to attend to the restoration of the

Muscovite state, especially the revitalization of the

tax system and the issue of getting tax-exempt in-

dividuals back on the tax rolls. A Petitions Chan-

cellery was established to receive complaints from

the populace.

The Smolensk War (1632–1634) provoked the

assembling of people to discuss both the beginning

of the war and its ending, as well as taxes to pay

for it. On neither occasion were delegates elected;

the 1634 session was called on January 28 and met

the next day. Cossacks seized Azov (Azak) at the

mouth of the Don River from the Crimean Tatars

in 1637, and there may have been meetings about

that in 1637 and again in 1639 (on July 19). Un-

questionably unelected men, in Moscow for court

sessions, were convoked for several days in Janu-

ary 1642 to discuss Azov, whence the cossacks

were ordered to withdraw out of fear of provok-

ing Turkey, with whom the Russians were unable

and unwilling to go to war. Some historians allege

that there was an Assembly in 1645 after the death

of Mikhail, but others point out that contempo-

raries alleged that his successor Alexei was illegit-

imate because he had not been elected. The latter

perspective seems correct because there was no As-

sembly of the Land in 1645.

The most significant Assembly of the Land was

the one taking place from October 1, 1648, to Jan-

uary 29, 1649, convoked to discuss the Odoyevsky

Commission’s draft of the new Law Code of 1649,

the Sobornoe ulozhenie. This Assembly, organized

following riots in Moscow and a dozen other towns

in June 1648 demanding governmental reforms,

was a true two-chambered assembly with delegates

in the lower chamber from 120 towns or more.

Evidence survives about contested elections in sev-

eral places. Although the records of the meetings

were probably deliberately destroyed because the

government did not like what eventuated, the iden-

tity of most of the delegates is known. Most of

them signed the Ulozhenie, and most of them sub-

mitted petitions for compensation afterward. The

demands of the delegates were met in the new law

code: the enserfment of the peasantry; the grant-

ing of monopolies on trade, manufacturing, and

the ownership of urban property to the legally

stratified townsmen; and a reigning in and further

secularization of the church. This marked the be-

ginning of the end of a proto-parliamentary insti-

tution in Russia. The government saw firsthand

what could happen when the delegates got their

way, which occasionally ran contrary to what the

ruling elite desired. In 1653 the government con-

voked another assembly, about which very little is

known, on the issue of going to war to annex

Ukraine. That was the last such meeting.

For about ninety years, Assemblies of the Land

dealt with issues of war and peace, taxation, suc-

cession to the throne, and law. When the 1648–1649

session got out of hand, the government resolved

to do without the Assemblies, having realized that

its new system of central chancelleries could pro-

vide all the information it needed to make rational

decisions.

See also: GODUNOV, BORIS FYODOROVICH; LAW CODE OF

1649; LIVONIAN WAR; OPRICHNINA; SMOLENSK WAR;

TIME OF TROUBLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Peter Bowman. (1983). “The Zemskii Sobor in Re-

cent Soviet Historiography.” Russian History 10(1):

77–90.

Hulbert, Ellerd. (1970). “Sixteenth Century Russian As-

semblies of the Land: Their Composition, Organiza-

tion, and Competence.” Ph.D. diss., University of

Chicago.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

ASSORTMENT PLANS

Assortment plans were state-generated documents

that specified the composition of output to be pro-

duced by Soviet enterprises. Each year a compre-

hensive plan document, the techpromfinplan (the

technical, industrial, and financial plan) was issued,

containing approximately one hundred targets that

ASSORTMENT PLANS

91

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet businesses were legally required to achieve.

This annual enterprise plan was part of a five-year

plan that established the long-term objectives of

central planners.

The most important component of the annual

plan sent to enterprises involved the production

plan, which disaggregated annual production tar-

gets into their component parts, breaking them out

in terms of both volume and value goals. The as-

sortment plans also incorporated demand condi-

tions set by consumers or firms, as identified by

planners. For example, a shoe factory would be

given an aggregate output target—the total num-

ber of units of footwear to produce in a given year.

The assortment plan then specified the type of

footwear to be produced: the number of children’s

and adults’ shoes, the number of men’s and women’s

shoes, the number of shoes with buckles and ties,

the number of brown and black leather shoes, and

so forth. Planners constructed the assortment plan

to capture demographic characteristics as well as

to reflect the tastes and preferences of Soviet con-

sumers. Similarly, the assortment plan component

of the techpromfinplan sent to a steel-pipe manu-

facturing plant would identify the quantities of

pipes of different dimensions and types, based on

the needs of firms which would ultimately use the

pipe.

Typically, Soviet managers gave less priority to

fulfilling the assortment plan than to the overall

quantity of production, because fulfilling the ag-

gregate output plan targets formed the basis for

the bonus payment. Adjustments made within the

assortment plan enabled managers to fulfill quan-

tity targets even when materials did not arrive in

a timely fashion or in sufficient quantity. For ex-

ample, managers could “overproduce” children’s

shoes relative to adults’ shoes, if leather was in short

supply, thereby generating a shortage in adult

footwear relative to the needs of the population.

This practice of adjusting quantities within the as-

sortment plan imposed higher costs when steel

pipes and other producer goods were involved, be-

cause producing three-inch pipe instead of the req-

uisite six-inch pipe obliged recipient firms to

reconfigure or adapt their equipment to fit the

wrong-sized pipe.

See also: ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; FIVE-YEAR PLANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ellman, Michael. (1979). Socialist Planning. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

Krueger, Gary. (1991). “Aggregation in Planning.” Jour-

nal of Comparative Economics 15(4): 627–645.

S

USAN

J. L

INZ

ASTRAKHAN, KHANATE OF

The Khanate of Astrakhan was a tribal union of

Sunni Muslim pastoral nomadic Turkic-speaking

peoples, located in the lower Volga region, with the

capital of Astrakhan (Citracan) situated at the con-

fluence of the river into the Caspian Sea. Tradi-

tionally, it is believed that the khanate of Astrakhan

was formed sometime in the mid-1400s (certainly

by 1466), when the tribe seceded from the Golden

(or Great) Horde, probably under Mahmud Khan

(died c. 1466). Many scholars attribute the foun-

dation of the khanate to Qasim I (1466–1490), per-

haps Mahmud Khan’s son. However, a recent study

argues that the khanate was formed only after

1502. Specifically, from the 1450s to the 1470s,

Astrakhan was one of the centers of the Great

Horde and after the destruction of Saray (the old

capital), not earlier than the 1480s, became its new

capital. Astrakhan continued to be the capital of the

Great Horde until its collapse in 1502 at the hands

of the Crimean Khanate and, thereafter, remained

its political heir in the form of the Astrakhan

Khanate. There was no change of dynasty, nor was

there any internal structural transformation to the

state. The only major difference with its predeces-

sor is that its borders were probably smaller.

The peoples of the Astrakhan Khanate mostly

retained their nomadic lifestyles as they seasonally

migrated in north–south directions in search of

grasslands for their livestock, reaching as far north

as the southern borders of Muscovy. Due to the

small territory it occupied, the khanate did not have

sufficient lands for grazing large numbers of ani-

mals and sustaining large human resources. For

these reasons, the khanate was relatively weak mil-

itarily and prone to political interference in its af-

fairs from its more powerful neighbors, including

the successor Mongol khanates and Muscovy. The

khanate also offered little by way of natural re-

sources, aside from salt, fish, and hides.

Astrakhan, while a busy, wealthy, and large

port city in the early Mongol era, fell into relative

neglect after its destruction by Tamerlane in around

1391, as noted by Barbaro (d. 1494). Other West-

ern visitors to Astrakhan, such as Contarini (1473)

and Jenkinson (1558), noted the paucity of trade

ASTRAKHAN, KHANATE OF

92

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY