Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

TUVA AND TUVINIANS

The Tuva Republic in southern Siberia is one of the

twenty-one nationality-based republics within the

Russian Federation that was recognized in the Rus-

sian constitution of 1993. Previously called the

Tuva Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR),

the constitution recognized it as Tyva, the regional

form of the name. With an area of 65,810 square

miles (170,448 square miles), Tuva lies northwest

of Mongolia and directly east of Gorno-Altai.

Tuva’s capital is Kizyl, and its other key cities are

Turan, Chadan, and Shagonar. Drained by the

headstreams of the Yenisey River, the western part

of Tuva lies in a mountain basin, walled off by the

Sayan and Tannu Olga ranges, which rise to

10,000 feet. The eastern portion is dominated by a

wooded plateau. The climate is extreme, with sum-

mer temperatures reaching 43º C (110º F) and win-

ter temperatures dropping to –61ºC (–78ºF).

However, the region’s three hundred sunny, arid

days per year help the people withstand the sum-

mers and winters.

Tuva is inhabited by a majority of Tuvinians

(more than 64%); the remainder are primarily eth-

nic Russians (32%). More than 200,000 Tuvinians

live in the Russian Federation, and smaller com-

munities live in Mongolia and China. The Tuvini-

ans are hardy Mongol natives, related to the

Kyrgyz ethnic branch. Because it is difficult to spec-

ify physical features that are common to all the

Turkic peoples, it is the shared cultural feature of

language that identifies members of a particular

group. The Turkic languages strongly resemble one

another, most of them being to some extent mu-

tually intelligible. The peoples of Siberia fall into

three major ethno-linguistic groups: Altaic, Uralic,

and Paleo-Siberian. The Tuvinians are one of the

Altaic peoples, and the Tuvin language belongs to

the Uighur-Oguz group of the Altaic language

family. Together with the ancient Uighur and Oguz

languages, these linguistic groups form the sub-

group of Uighur-Tüküi. Even if a special Decree on

Languages in the Tuva ASSR had not been ratified

in 1991 stipulating that all academic subjects be

taught in Tuvinian, the Tuvinian language would

TUVA AND TUVINIANS

1593

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

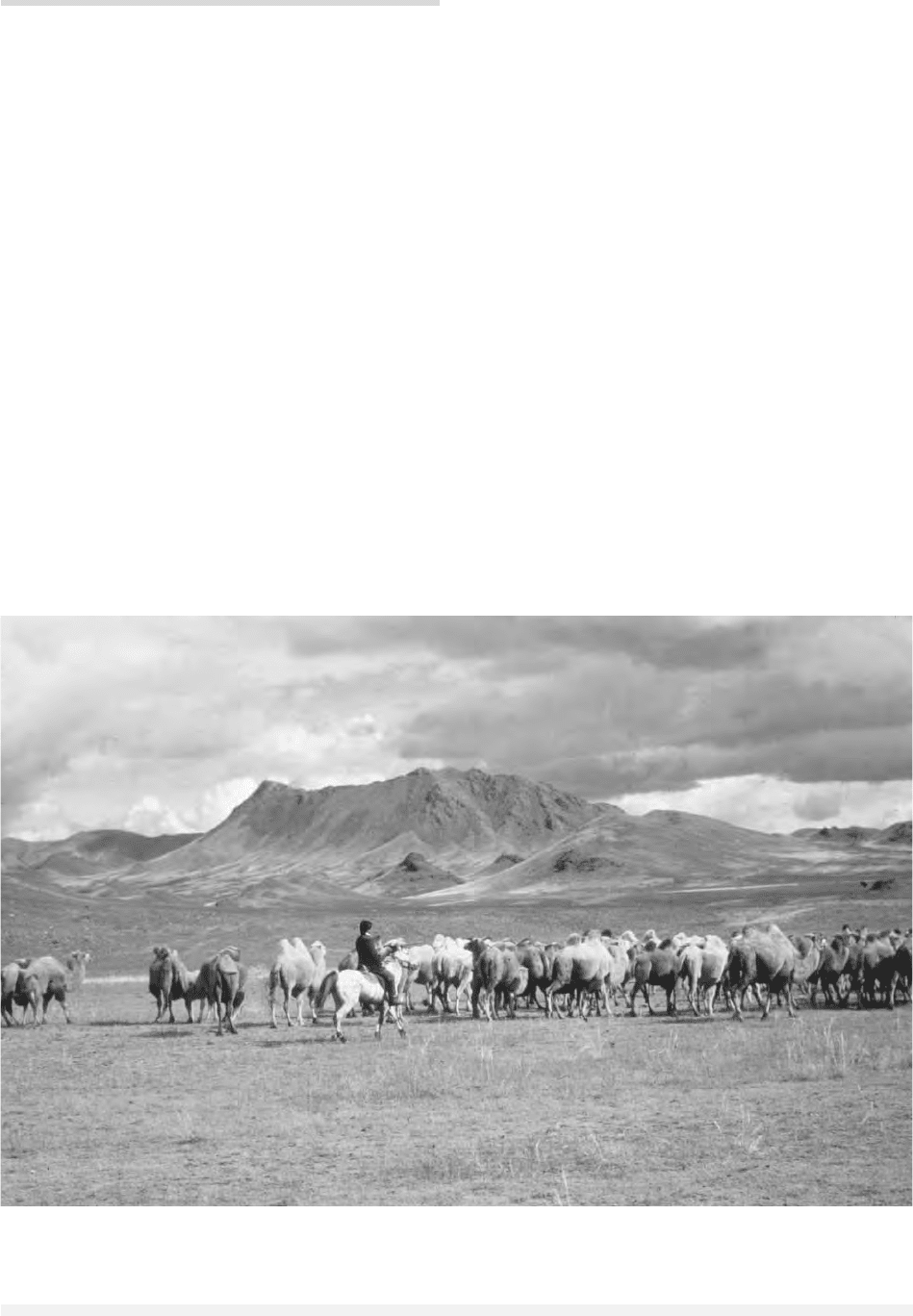

Camel herd and herder. © N

OVOSTI

/S

OVFOTO

not be forgotten. The indigenous language is most

widely spoken in rural areas, where 67–70 percent

of Tuvinians live. The official lingua franca (Rus-

sian) is spoken mainly in Tuva’s four major towns.

For roughly 150 years Tuva formed part of the

Chinese Empire, and later was subject to Mongol

rule. An independent state, called Tannu Tuva, was

established on August 14, 1921. Tuva nevertheless

voluntarily joined the USSR in 1944 as an au-

tonomous oblast. In 1961 Tuva became an au-

tonomous republic.

Tuvinians are mostly engaged in agricultural

activities, such as cattle raising and fur farming.

Oats, barley, wheat, and millet are the principal

crops raised. Recently, farmers from northern

China have introduced the Tuvinians to vegetable

farming. Many Tuvinians still live as nomadic

shepherds, migrating seasonally with their herds.

Those who inhabit the plains traditionally live in

large round tents, called gers (yurts), made from

bark. The main industrial activity in the Tuvinian

Republic is mining, especially for asbestos, cobalt,

coal, gold, and uranium. Other Tuvinians are en-

gaged in processing food, manufacturing building

materials, and crafting leather and wooden items.

Most Tuvinians were illiterate until the advent

of the Russians. Thus, the Tuvinian culture is noted

for its rich, oral epic poetry and its music (throat

singing). The Tuvinian use more than fifty differ-

ent musical instruments, and traveling ensembles

often perform outdoors. The Tuvinians in East Asia

have never been affected by Islam. In the early

twenty-first century, one-third of the Tuvinians are

Buddhists, one-third are shamanists (believing in an

unseen world of gods, demons, and ancestral spir-

its), and the remaining one-third are non-religious.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; KYRGYZSTAN AND KYRGYZ; NA-

TIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLI-

CIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Balzer, Marjorie Mandelstam. (1995). Culture Incarnate:

Native Anthropology from Russia. Armonk, NY: M.E.

Sharpe.

Diószegi, Vilmos, and Hoppál, Mihály. (1998). Shaman-

ism: Selected Writings of Vilmos Diószegi. Budapest:

Akadémiai Kiadó.

Drobizheva , L. M. (1996). Ethnic Conflict in the Post-So-

viet World: Case Studies and Analysis. Armonk, NY:

M. E. Sharpe.

Leighton, Ralph. (1991). Tuva or Bust! Richard Feynman’s

Last Journey. New York: W. W. Norton.

Vainshtein, S. I. (1980). Nomads of South Siberia: the Pas-

toral Economies of Tuva. New York: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Wangyal, Tenzin, and Dahlby, Mark. (2002). Healing

with Form, Energy and Light: The Five Elements in Ti-

betan Shamanism, Tantra, and Dzogchen. Ithaca, NY:

Snow Lion Publications.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

TWENTY-FIVE THOUSANDERS

At the November 1929 plenum of the Central Com-

mittee of the Communist Party, it was decided to

mobilize 25,000 industrial workers to help with

collectivization and provide the countryside with

thousands of loyal cadres.

Over 70,000 workers volunteered to serve as

Twenty-Five Thousanders (Dvadsatipiatitysiach-

niki). The All-Union Central Council of Trade

Unions (VTsSPS) directed and organized the mobi-

lization campaign, set selection criteria, and estab-

lished regional quotas. Of the 27,519 workers

selected, nearly 70 percent were members or can-

didate-members of the party, and over half were

under thirty years old.

Following short preparatory courses, the

Twenty-Five Thousanders arrived in the country-

side during the first phase of forced collectivization

in early 1930. Most were assigned to work as chair-

men of large collective farms. Others were to work

in state farms, machine tractor stations (MTS), vil-

lage soviets, or various local Party organizations.

However, owing to the hostility of local officials,

a great many Twenty-Five Thousanders were put

to other tasks or ignored, and often not given ad-

equate food or housing. Some were assaulted or

murdered by angry peasants. Despite the obstacles,

many farms headed by Twenty-Five Thousanders

earned awards from party and collective-farm or-

gans for being model collective farms.

The Twenty-Five Thousanders were expected to

remain in the countryside until the end of the First

Five-Year Plan in 1932. However, only 40 percent

finished out their terms. Nonetheless, the Twenty-

Five Thousanders were hailed as heroes of socialist

construction. Many were promoted into rural

party and government work, and several earned the

distinguished honor of Heroes of Socialist Labor.

See also: COLLECTIVE FARM; COLLECTIVIZATION; COLLEC-

TIVIZATION OF AGRICULTURE

TWENTY-FIVE THOUSANDERS

1594

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Viola, Lynn. (1987). The Best Sons of the Fatherland: Work-

ers in the Vanguard of Soviet Collectivization. New

York: Oxford University Press.

K

ATE

T

RANSCHEL

TYUTCHEV, FYODOR IVANOVICH

(1803–1873), Russian poet.

Widely considered one of the greatest poets in

world literature, Tyutchev can be classified as a late

romantic, but, like other persons of surpassing

genius, he was strikingly unique. Tyutchev’s liter-

ary legacy consists of some three hundred poems

(about fifty of them translations), usually brief,

and several articles. Although recognition came

slow to Tyutchev, in fact, he never had a regular

literary career, eventually books of his poetry came

to be the treasured possessions of every educated

Russian.

Many of Tyutchev’s poems deal with nature.

Some of them offer luminous images of a thun-

derstorm early in May or of warm days at the be-

ginning of autumn. Others express the pantheistic

beliefs of romanticism (“Thought after thought /

Wave after wave / Two manifestations / Of one

element”), particularly its preoccupation with

chaos. Indeed, the philosopher Vladimir Soloviev

considered Tyutchev’s treatment of chaos, which

he represented as the dark foundation of all exis-

tence, whether of nature or human beings, to be

the central motif of the poet’s creativity, more

powerfully expressed than by anyone else in all lit-

erature. Tyutchev’s poem Silentium can be cited as

the ultimate culmination of the desperate roman-

tic effort to, in the words of William Wordsworth,

“evoke the inexpressible.” A somewhat different,

small, but unforgettable group of Tyutchev’s po-

ems deals with the hopelessness of late love (“thou

art both blessedness and hopelessness”), reflecting

the poet’s tragic liaison with a woman named

Mademoiselle Denisova.

An aristocrat who received an excellent educa-

tion at home and at Moscow University, Tyutchev

was a prime example of cosmopolitan, especially

French, culture in Russia. Choosing diplomatic ser-

vice, he spent some twenty-two years in central

and western Europe, particularly in Munich. The

service operated in French, and Tyutchev’s French

was so perfect that, allegedly, other diplomats, in-

cluding French diplomats, were advised to use Tyut-

chev’s reports as models. Tyutchev was prominent

in Munich society and came to know Friedrich

Schelling and other luminaries. He married in suc-

cession two German women, neither of whom

spoke Russian.

Politically, Tyutchev belonged to the Right. Not

really a Slavophile in the precise meaning of that

term, he stood with the Petrine imperial govern-

ment, where he served as a censor (a tolerant one,

to be sure) as well as a diplomat. He may be best

described as a member of the romantic wing of sup-

porters of the state doctrine of Official Nationality

and, later, as a Panslav. Tyutchev’s most promi-

nent articles, as well as a number of his poems,

were written in support of the patriotic, national-

ist, or Panslav causes. They lacked originality and

even high quality, at least by the poet’s own stan-

dards. Yet Tyutchev’s power of expression was so

great that occasionally these items became indeli-

ble parts of Russian consciousness and culture:

One cannot understand Russia by reason,

Cannot measure her by a common measure:

She is under a special dispensation—

One can only believe in Russia.

See also: GOLDEN AGE OF RUSSIAN LITERATURE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mirsky, D. S. (1949). A History of Russian Literature. New

York: Knopf.

Nabokov, Vladimir. (1944). Three Russian Poets: Selections

from Pushkin, Lermontov and Tyutchev in New Trans-

lations by Vladimir Nabokov. Norfolk, CT: New Di-

rections.

Pratt, Sarah. (1984). Russian Metaphysical Romanticism:

The Poetry of Tiutchev and Boratynskii. Stanford: Stan-

ford University Press.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (1992). The Emergence of Ro-

manticism. New York and Oxford: Oxford Univer-

sity Press.

N

ICHOLAS

V. R

IASANOVSKY

TYUTCHEV, FYODOR IVANOVICH

1595

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

U-2 SPY PLANE INCIDENT

On May 1, 1960, an American high-altitude U-2 spy

plane departed from Pakistan on a flight that was

supposed to take it across the USSR to Norway. Shot

down near Sverdlovsk, with its pilot, Francis Gary

Powers, captured, the flight triggered a Cold War cri-

sis, aborted a scheduled four-power summit meet-

ing, and poisoned Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s

relations with U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Aware that U-2 spy flights constituted a grave

violation of Soviet sovereignty, Eisenhower reluc-

tantly approved them beginning in 1956 to check

on the Soviet missile program. Even after the May

Day 1960 flight was shot down, Khrushchev hoped

to proceed with the summit scheduled for May 16

in Paris. But by not revealing he had shot down

the plane and captured its pilot, and by waiting for

Washington to invent a cover story and then un-

masking it, Khrushchev provoked Eisenhower to

take personal responsibility for the flight. After

that, Khrushchev felt he had no choice but to wreck

the summit, cut off relations with Eisenhower, and

await the election of Eisenhower’s successor.

It is highly uncertain whether the Paris sum-

mit could have produced progress on Berlin and a

nuclear test ban. Russian observers such as Fyodor

Burlatsky and Georgy Arbatov contend that

Khrushchev used the U-2 incident as an excuse to

scuttle what he anticipated would be an unpro-

ductive summit. More likely, Khrushchev was

lured by the flight and its fate into a sequence of

unintended consequences that undermined not only

his foreign policy but his position at home.

See also: COLD WAR; KHRUSHCHEV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beschloss, Michael R. (1986). Mayday: Eisenhower, Khrush-

chev, and the U-2 Affair. New York: Harper and Row.

Taubman, William. (2003). Khrushchev: The Man and His

Era. New York: W. W. Norton.

W

ILLIAM

T

AUBMAN

UDMURTS

Of the 747,000 Udmurts (1989 census), formerly

called Votiaks, approximately 497,000 live in the

Udmurt Republic, north of Tatarstan, but many

live in Bashkortostan. Their language belongs to

U

1597

the Finno-Ugric family and is mutually semi-

intelligible with Komi, further north. Most are Cau-

casian, with a remarkable number of redheads, but

Asian features also occur.

Southern Udmurts were subjected to the Bol-

gar Empire from 1000

C

.

E

. on, and later to the

Kazan Khanate. After annexing the multinational

Viatka Republic (1489), Moscow laid formal claim

to all Udmurt lands but controlled only the north.

The south was occupied after the destruction of

Kazan (1552), yet massive uprisings continued up

to 1615. Most Udmurts were forcibly baptized in

the mid-1700s, but spectacular anti-animist trials

flared as late as 1894–1896, and 7 percent of Ud-

murts declared themselves animist in the 1897 cen-

sus. An Udmurt-language calendar started in 1904

and the first newspaper in 1913.

An Udmurt national congress convened in

1918. A Votiak Autonomous Oblast was formed

in 1920 and upgraded to Udmurt Autonomous Re-

public in 1934. Native-language schooling devel-

oped rapidly, but as early as 1931 a trumped-up

anti-Soviet “Finno-Ugric plot” decimated the elites.

Udmurtia itself became the site of numerous slave

labor camps. All Udmurt textbooks were ordered

destroyed around 1970.

Udmurtia (population 1.6 million), on the bor-

derline of forest and steppe, is dominated by its

capital, Izhkar (Izhevsk in Russian; population

600,000), a major center of Soviet military indus-

try. Russian immigration reduced the Udmurts

from 52 percent of the Republic population in 1926

to 31 percent in 1989. Russian passersby chastised

those few who dared to speak Udmurt in city streets.

Within the Republic 76 percent of Udmurts con-

sider the ancestral language their main one. Liber-

alization enabled an Udmurt cultural society to

form in 1989. Later called Demen (Together), it

spawned an activist youth organization, Shundy

(The sun). Udmurtia’s Russian-dominated Supreme

Soviet proclaimed Russian and Udmurt coequal state

languages, but implementation has been limited. In

1991 an Udmurt National Congress established

a permanent Udmurt Kenesh (Council). Udmurt-

language schooling began to develop slowly.

See also: FINNS AND KARELIANS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lallukka, Seppo. (1982). The East Finnic Minorities in the

Soviet Union: An Appraisal of Erosive Trends. Helsinki:

Annales Academiae Scientarum Fennicae.

Taagepera, Rein. (1999). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the

Russian State. London: Hurst.

R

EIN

T

AAGEPERA

UEZD

The uezd is an administrative-territorial unit that

was used in pre-Soviet Russia and the early Soviet

Union. During the formation of the Moscow state

during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it des-

ignated an area that included both a town and its

hinterland, and which came under the jurisdiction

of a namestnik (governor). From the late sixteenth

century, the uezd was under the jurisdiction of

a voyevod (military governor). Under Peter I, the

uezd became a subdivision of governments and

provinces. Between 1775 and 1780, Catherine II’s

reform of the Russian Empire’s territorial adminis-

tration recreated the uezd as the primary subdivi-

sion of a guberbiya (government), based on a (male)

population of between twenty and thirty thousand.

Each uezd, which was itself subdivided into

volosti (boroughs), came under the jurisdiction of

an ispravnik (district captain) who was elected every

three years by the district assembly of the nobil-

ity. The district captain held responsibility for the

maintenance of law and order and for fiscal ad-

ministration. In European Russia, the 1864 zemstvo

reform created assemblies at the uezd level, elected

on a restrictive property-based franchise. Every

three years, the uezd assembly elected an executive

board responsible for district administration. It also

elected delegates to an assembly at the guberniya

level. Provincial governors had to ratify the ap-

pointment of the president of each uezd board and,

from 1890, of all its members (at the same time

the assembly franchise was further narrowed). Af-

ter the February Revolution in 1917, the Provi-

sional Government introduced the office of district

commissar to represent the central state in the lo-

calities; after the Bolshevik revolution authority

passed to the executive committee of the uezd so-

viet. At the end of the 1920s, the Soviet govern-

ment dissolved both the uezd and volost levels of

territorial administration, subdividing the new

oblasti (regions) directly into raiony.

See also: LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION

N

ICK

B

ARON

UEZD

1598

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

UGRA RIVER, BATTLE OF

The decisive moment of the defensive campaign led

by Ivan III against the horde of Khan Ahmad, in

October-November 1480.

Relations between the Great Horde and Moscow

entered a crisis in the 1470s. Ivan III refused to ac-

knowledge the sovereignty of Akhmad or to pay

him tribute. Entering into an anti-Muscovite al-

liance with the grand prince of Lithuania and the

Polish King Casimir, Ahmad started to campaign in

the late spring of 1480. Ivan III adopted defensive

tactics: In July he marched to the town of Kolomna

and ordered his troops to guard the bank of the

Oka River, but Ahmad made no attempt to force

the Oka; instead he moved westward to the Ugra

River where he hoped to meet his ally, King Casimir.

The latter, however, never came.

For several months both sides temporized, and

only in October did fighting break out. Muscovite

troops, led by Ivan’s III son Ivan and brother An-

drew, repulsed several Tatar attempts to cross the

Ugra. Clashes alternated with negotiations which,

however, met with no success. Finally, on No-

vember 11, 1480, the khan withdrew, thus ac-

knowledging the failure of his attempt to restore

his lordship over Rus.

In Russian historical tradition this event is cel-

ebrated as the end of the Mongol yoke. The roots

of this tradition date back to the 1560s, when

anonymous author of the so-called Kazan History

wrote of the dissolution of the Horde after the death

of Ahmad (1481) and hailed the liberation of the

Russian lands from the Moslem yoke and slavery.

In modern historiography, Nikolai Karamzin was

the first to link the liberation with the events of

1480. Later, Soviet publications echoed this view.

Another judgment of the same events was pro-

nounced by the famous nineteenth-century Russ-

ian historian, Sergei Soloviev, who ascribed the

downfall of the yoke not to the heroic deeds of Ivan

III but to the growing weakness of the Horde it-

self. The same argument was put forward by

George Vernadsky (1959), who maintained that

Rus freed itself from dependence on the Horde not

in 1480 but much earlier, in the 1450s. In Anton

Anatolevich Gorskii’s view, the liberation should be

dated not to 1480 but to 1472, when Ivan III

stopped paying tribute to the khan.

Military aspects of the 1480 event also remain

controversial. Some scholars consider the battle a

large-scale military operation and honor the strate-

gic talent of Ivan III; but others stress his hesita-

tions or even deny that any battle took place,

referring to the events of 1480 as merely the “Stand

on the Ugra River” (Halperin, 1985).

See also: GOLDEN HORDE; IVAN III

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Halperin, Charles. (1985). Russia and the Golden Horde: The

Mongol Impact on Medieval Russian History. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

Vernadsky, George. (1959). Russia at the Dawn of the Mod-

ern Age. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

M

IKHAIL

M. K

ROM

UKAZ

A decree, edict, or order issued by higher author-

ity and carrying the weight of law. In English,

ukase.

The Dictionary of the Imperial Russian Academy

(1822) defined ukaz (plural ukazy) as “a written

order issued by the Sovereign or other higher

body.” Senior churchmen and the Senate, for ex-

ample, could issue an ukaz, but no one had power

independent of the ruler. An edict or order signed

personally by the ruler was known as imennoi

ukaz. Up to the end of the seventeenth century,

the tsar’s ukazy were recorded by scribes, but from

the 1710s onwards the more important ones were

printed, either as individual sheets or in collections.

In 1722 Peter I issued an ukaz on the orderly col-

lection, printing, and observance of existing laws.

It ended: “Let this ukaz be printed, incorporated

into the regulations, and published. Also set up dis-

play boards, according to the model supplied in the

Senate, to which this printed ukaz should be glued,

and let it always be displayed in all places, right

down to the lowest courts, like a mirror before the

eyes of judges. . . . This ukaz of His Imperial

Majesty was signed in the Senate in His Majesty’s

own hand.” The very sheets of paper bearing the

ruler’s printed command were imbued with his

authority.

Given the significance attached to the Russian

sovereign’s written command and signature, the

anglicized term “ukase” has connotations of abso-

lutism. It is often coupled with other instruments

UKAZ

1599

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of autocratic rule, such as the knout and exile to

hard labor, as a symbol of despotic government.

See also: PETER I

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

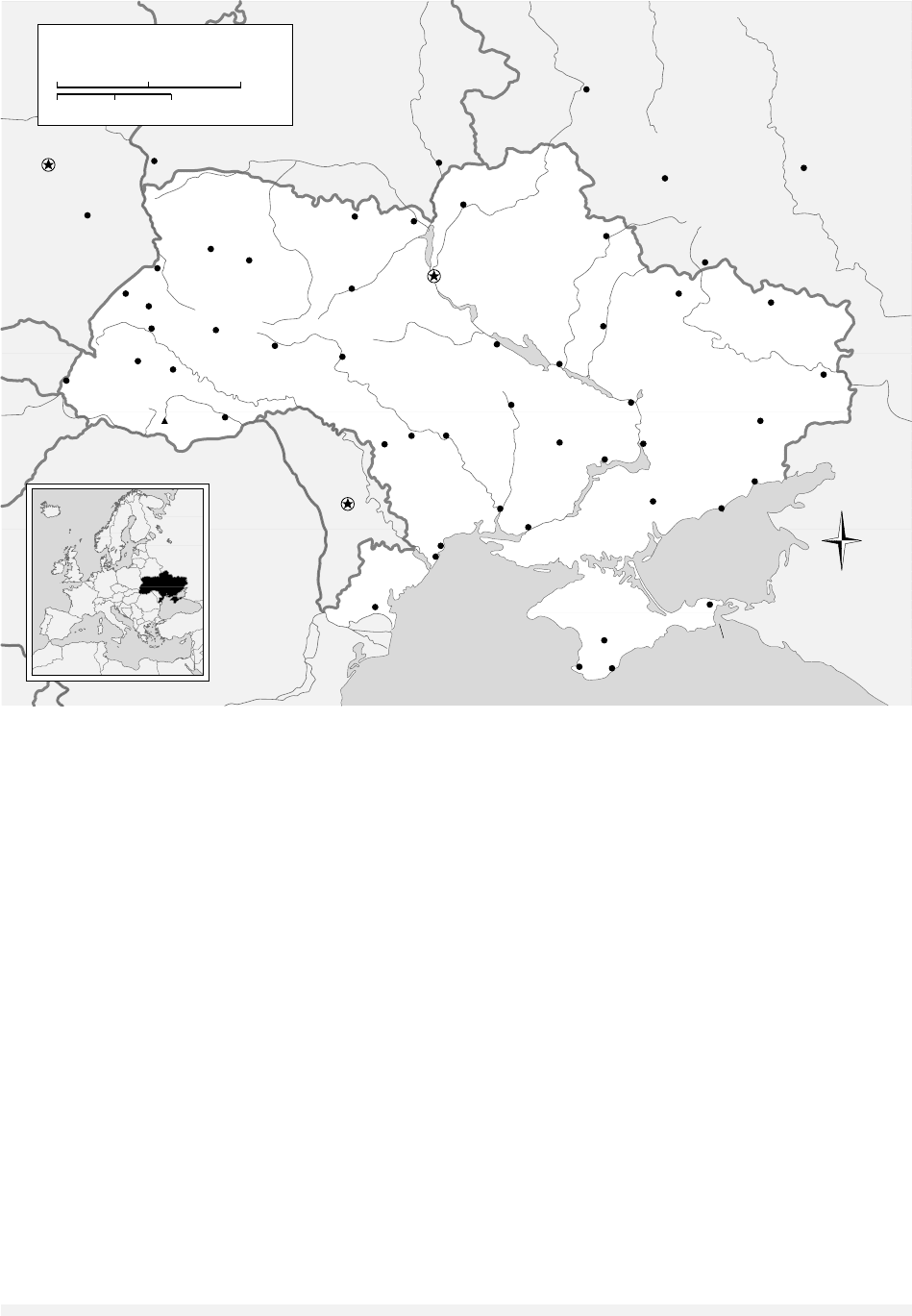

UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe, the second

most populous among the Soviet successor states

and Europe’s second largest country after Russia.

Its population in 2001 was 48,457,100, with eth-

nic Ukrainians comprising 77.8 percent of the to-

tal. Russians constitute by far the largest ethnic

minority in the country (17.3%). Ukrainians are an

Eastern Slavic people who speak the Ukrainian lan-

guage, which is closely related to Russian and uses

the Ukrainian version of the Cyrillic alphabet. The

capital of Ukraine is Kiev (Kyiv). Geographically,

Ukraine consists largely of fertile level plains that

are ideal for agriculture. The country’s main river

is the Dnieper (Dnipro).

EARLY HISTORY

Ukraine did not exist in its current territorial form

until the twentieth century. In ancient times, dif-

ferent parts of Ukraine were inhabited by the

Scythians and Sarmatians, but Slavic tribes moved

into the area during the fifth and sixth centuries.

During the ninth century, the Varangians, who

had controlled trade on the Dnieper, united the East

Slavic tribal confederations into the state known as

Kievan Rus. During the late tenth century, the Rus

princes accepted Christianity and began developing

a high culture in Church Slavonic. Scholars, how-

ever, believe that modern Ukrainian is a lineal de-

scendent of the colloquial language that was

spoken in Kievan Rus. The power of Kievan Rus be-

gan declining during the twelfth century, and dur-

ing the thirteenth it was conquered by the Mongols.

After the fall of Kiev, linguistic divergences between

the languages spoken by Eastern Slavs in the

Ukrainian and Russian lands began to harden.

Indigenous state tradition in the Ukrainian

territories was extinguished during the early four-

teenth century with the decline of the Galician-

Volhynian Principality in the west. During the sec-

ond half of this century, the Grand Duchy of

Lithuania, a rising Eastern European empire at the

time, annexed virtually all the Ukrainian lands ex-

cept Galicia, which was claimed by Poland. But the

East Slavic lands preserved considerable autonomy,

and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania even adopted

the local Ruthenian language as its state language.

This changed in 1569, when the dynastic union be-

tween Lithuania and Poland evolved into a consti-

tutional union. The indigenous nobility gradually

became Polonized, cities came to be dominated by

Poles and Jews, and the local peasantry was en-

serfed and exploited. In 1596 a crisis in the Ortho-

dox Church and pressure from Polish Catholics

prompted the majority of Ukrainian Orthodox

bishops in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

to sign an act of union with Rome, resulting in the

creation of the Uniate Church and a religious rift

between the Orthodox and Uniate churches. From

that time, social grievances of the Ukrainian lower

classes coalesced with religious and national anxi-

eties.

These growing tensions found their expression

in the Cossack rebellions. The Cossacks were a class

of free warriors that emerged during the sixteenth

century on Ukraine’s southern steppe frontier. Al-

though originally employed by Polish governors to

defend steppe settlements against the Crimean

Tatars, the Cossacks, many of whom had been

peasants fleeing serfdom, identified with the reli-

gious and social concerns of lower-class Ukraini-

ans. In 1648 a large Cossack revolt turned into a

peasant war. Led by a disgruntled Cossack officer

named Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the rebels, who had

secured Tatar support and had seen their ranks

swelled with peasant recruits, inflicted several

crushing defeats on the Poles. Khmelnytsky, who

had been elected the Cossack leader, or hetman, and

calling himself a defender of Orthodoxy and the

Ruthenian people, soon began building a de facto

independent Cossack state. Looking for allies

against Poland, in 1654 Khmelnytsky concluded

the Pereiaslav Treaty with Muscovy; the signifi-

cance of this treaty remains a subject of contro-

versy.

Whether it was intended as a temporary diplo-

matic maneuver or a unification of two states, ac-

cording to the treaty, the Cossack polity accepted

the tsar’s suzerainty while preserving its wide-

ranging autonomy. In the long run, however, the

Russian authorities gradually curtailed the Cos-

sacks’ self-rule and, by the late eighteenth century,

had established their direct control of Ukraine. The

last serious attempt to break with Russia took place

under Hetman Ivan Mazepa, who joined Charles

XII of Sweden in his war against Tsar Peter I, but

UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

1600

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the Russian army and the loyalist Cossacks defeated

the united Swedish-Ukrainian forces in the Battle

of Poltava (1709). The last hetman, a largely sym-

bolic figure, was forced to resign in 1764, and in

1775 the Russian army destroyed the Zaporozhian

Host, the principal bastion of the Ukrainian Cos-

sacks.

IMPERIAL RULE

Poland remained the master of Galicia, Volhynia,

and other Ukrainian lands west of the Dnieper un-

til its partitions in the years from 1772 to 1795.

Following the disappearance of the Polish state,

Galicia became part of the Austrian Empire, while

other Ukrainian territories were incorporated into

the Russian Empire, ruled by the Romanov Dy-

nasty. The Ukrainian people’s experience within the

two empires was markedly different.

The Romanovs abolished the administrative

distinctiveness of Ukrainian territories and promoted

the assimilation of Ukrainians. The apogee of this

policy was the 1863 official ban on Ukrainian-

language publications, which was reinforced in

1876. Yet, the Russian conquest of the Crimea in

1783 opened up the southern steppes for coloniza-

tion, thus greatly expanding Ukrainian ethnic ter-

ritory. Following the abolition of serfdom in 1861,

industrial development began in earnest in south-

eastern Ukraine, resulting in the creation of large

coal and metallurgical centers in the Donbas and

Kryvyi Rih regions. The Russian cultural physiog-

nomy of cities and industrial settlements produced

an assimilated working class, which would iden-

tify politically with all-Russian parties.

Like elsewhere in Eastern Europe, the Ukrain-

ian national revival began with the discovery of a

UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

1601

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Mt. Hoverla

6,762 ft.

2061 m.

D

o

n

e

t

s

'

K

r

y

a

z

h

Crimean

Peninsula

K

R

I

M

S

'

K

E

H

O

R

Y

P

o

d

i

l

s

k

a

V

y

s

o

c

h

y

n

a

C

A

R

P

A

T

H

I

A

N

M

T

S

.

Sea of Azov

Black

Sea

D

o

n

e

t

s

'

D

n

i

p

r

o

(

D

n

i

e

p

e

r

)

P

i

v

d

B

u

h

D

n

i

s

t

e

r

P

r

u

t

T

i

s

z

a

B

u

g

P

r

y

p

'

y

a

t

'

D

n

i

p

r

o

(

D

n

i

e

p

e

r

)

D

e

s

n

a

P

s

e

l

Kremenchugskaye

Vodokhranilishche

Kerchenskiy

Proliv

Kakhovskoye

Vodokhranilishche

D

u

n

a

r

e

a

(

D

a

n

u

b

e

)

ù

Kirovohrad

Uzhhorod

Chemivtsi

Ivano-

Frankivs'k

L'vin

Rozdol

Kalush

Chervonograd

Luts'k

Yavoriv

Rivne

Ovruch

Ternopol'

Khmel'nysts'kyy

Vinnytsya

Pervomays'k

Pobuz'ke

Nikopol'

Zhytomyr

Chernobyl'

Chernihiv

Sumy

Shebekino

Svatove

Poltava

Cherkasy

Kremenchuk

Kryvyy Rih

Berdyans'k

Mykolayiv

Illichivs'k

Kherson

Sevastopol'

Yalta

Simferopol'

Mariupol'

Tokmak

Zaporizhzhya

Luhans'k

Donetsk

Kharkiv

Odesa

Dnipropetrovs'k

Kiev

Kerch

Balta

Chisinau

Warsaw

Lublin

Kiliya

Bryansk

Homyel'

Brest

Kursk

Vorenezh

¸

ROMANIA

MOLDOVA

POLAND

BELARUS

RUSSIA

SLOVAKIA

HUNGARY

W

S

N

E

Ukraine

UKRAINE

200 Miles

0

0

200 Kilometers

100

100

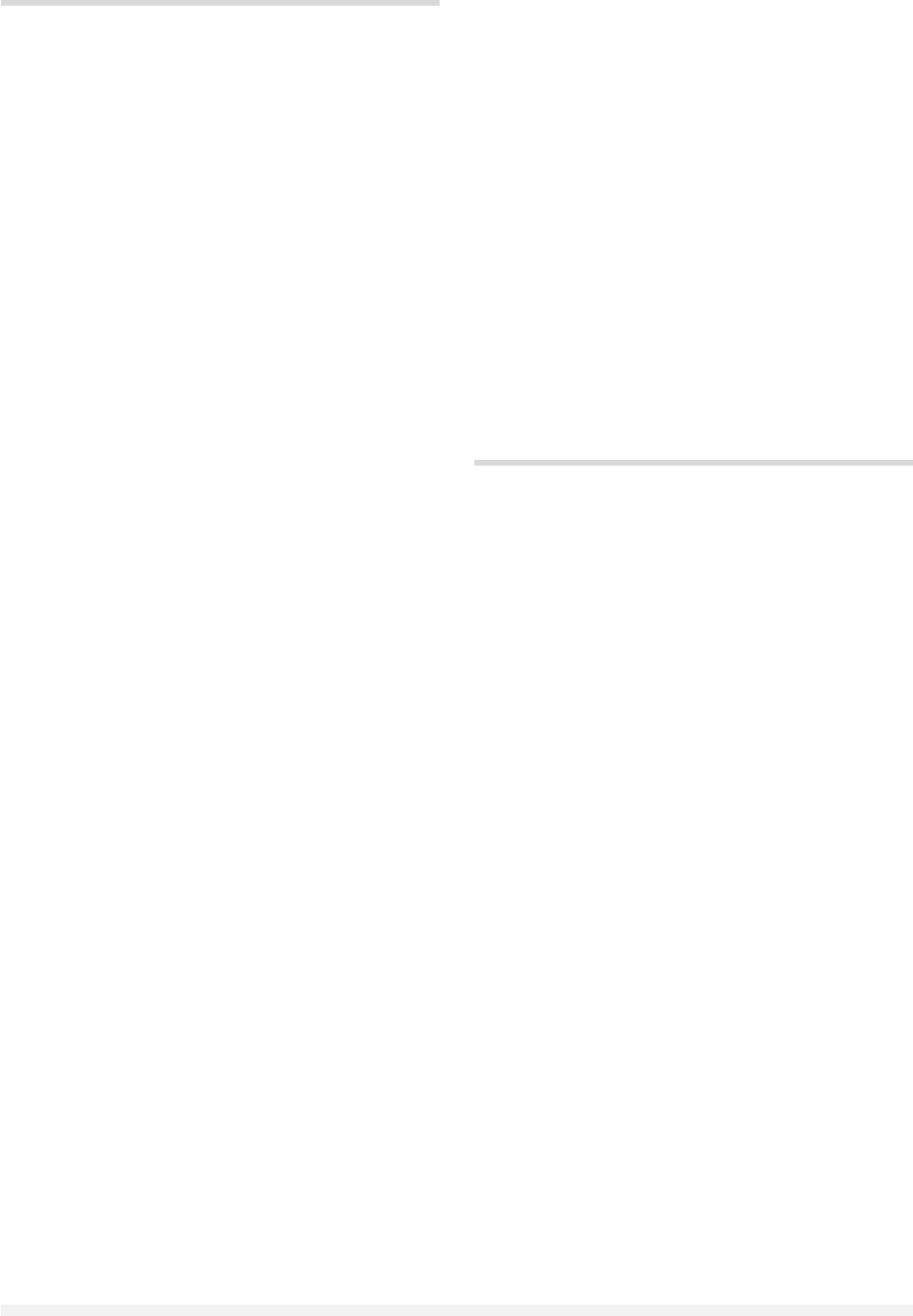

Ukraine, 1992. © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

new notion of nationality as a cultural and lin-

guistic community. Literature soon emerged as the

primary vehicle of cultural nationalism, and the

great poet Taras Shevchenko came to be seen as

its high priest. Together with other members of

the Cyril and Methodius Society (1845–1847),

Shevchenko also laid the foundations of Ukrainian

political thought, which revolved around the idea

of transforming the Russian Empire into a demo-

cratic federation. Such was the reasoning of the hro-

mady (communities), secret clubs of the Ukrainian

intelligentsia, which spearheaded the Ukrainian na-

tional movement during the second half of the cen-

tury. Ukrainian political parties began emerging at

the turn of the twentieth century, yet could not

built a mass support base during the short period

of legal existence between the Revolution of 1905

and the beginning of World War I.

The Habsburg Empire, in contrast, was based

simultaneously on accommodating its major na-

tionalities and pitting them against each other. In

addition to Transcarpathia, which for centuries had

been part of the Hungarian crown, during the late

eighteenth century the Habsburgs acquired two

other ethnic Ukrainian regions: Eastern Galicia and

Northern Bukovyna. In Galicia the landlord class

was overwhelmingly Polish, whereas in Bukovyna

Ukrainians competed with Romanians for influ-

ence. Although they were never Vienna’s favorites,

the Ruthenians of the Habsburg Empire did not

experience the repressions against their national

development that were suffered by the Little Rus-

sians (Ukrainians) in the Russian Empire. Ukrainians

benefited from educational reforms that established

instruction in their native language, and by the of-

ficial recognition of the Uniate Church, which would

become their national institution.

Ukrainians emerged as a political nationality

during the Revolution of 1848, when they estab-

lished the Supreme Ruthenian Council in Lviv and

put forward a demand to divide Galicia into

Ukrainian and Polish parts. The abolition of serf-

dom in 1848, however, did not lead to the indus-

trial transformation of Ukrainian territories, which

remained an agrarian backwater. Land hunger and

rural overpopulation resulted in mass emigration

of Ukrainians to North America, beginning in the

1880s. Modern political parties began emerging

during the 1890s, and the introduction in 1907 of

a universal suffrage provided Ukrainians with in-

creasing political representation. However, the

Ukrainian-Polish ethnic conflict in Galicia deepened

during the early twentieth century. Developments

in Bukovyna largely paralleled those in Galicia,

while Transcarpathia remained politically and cul-

turally dormant.

WORLD WAR I AND THE REVOLUTION

Galicia and Bukovyna were a military theater dur-

ing much of World War I. The annexation of these

lands and the suppression of Ukrainian nationalism

there was one of Russia’s war aims, but Russian

control of Lviv proved short-lived. In the Russian

Empire, the February Revolution of 1917 triggered

an impressive revival of Ukrainian political and cul-

tural life. In March of that year representatives of

Ukrainian parties and civic organizations formed

the Central Rada (Council) in Kiev, which elected the

distinguished historian Mykhail Sergeyevich Hru-

shevsky as its president. Instead of a dual power,

the situation in the Ukrainian provinces resembled

a triple power, with the Russian Provisional Gov-

ernment, the Soviets, and the Rada all claiming au-

thority.

With the Rada’s influence steadily increasing,

the Provisional Government was forced to recog-

nize it and, in July 1917, grant Ukraine auton-

omy. Following the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd on

November 7, the Rada refused to recognize the new

Soviet government and proclaimed the creation of

the Ukrainian People’s Republic, in federation with

a future, democratic Russia. Meanwhile, at the first

All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets (Kharkiv, De-

cember 1917), the Bolsheviks proclaimed Ukraine

a Soviet republic. In January 1918 Bolshevik troops

from Russia began advancing on Kiev, prompting

the proclamation by the Central Rada of full inde-

pendence on January 22.

Following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Bol-

sheviks were forced to evacuate their troops from

Ukraine. The Rada government returned with the

German and Austro-Hungarian armies, but it was

too left-leaning for the Central Powers. In April

1918 a German-supported coup installed General

Pavlo Skoropadsky as Hetman of Ukraine. This

conservative monarchy lasted in Ukraine until De-

cember, when the defeated Central Powers with-

drew their troops, and was replaced by the

Directory of the Ukrainian People’s Republic. The

new government was at first a dictatorship of sev-

eral Ukrainian socialists and nationalists, who had

previously been associated with the Rada, but later

all power became concentrated in the hands of

Symon Petliura.

As the Austro-Hungarian Empire began disin-

tegrating in October 1918, the Ukrainian political

UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

1602

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

leaders there declared the creation of the Western

Ukrainian People’s Republic. On January 22, 1919,

the two Ukrainian republics proclaimed their uni-

fication, which, however, was never carried through.

The Western Republic found itself fighting a civil

war against the Poles, who claimed all of Galicia for

their new state and eventually defeated the Ukrain-

ian forces in July 1919. In the meantime, the East-

ern Republic was being torn apart in an even more

confusing and brutal civil war fought among the

Directory, the Reds, the Whites, and various anar-

chist armies. The collapse of civic order in 1919 re-

sulted in Jewish pogroms, which were committed

by all the participating armies, but especially by

unruly peasant rebels. By early 1920 Soviet forces

controlled all Ukrainian territories of the former

Russian Empire except Volhynia and Western

Podolia, which were occupied by Poland. A Polish-

Soviet war in the spring and summer of 1920

briefly restored the Petliura government in Kiev, but

ultimately resulted in the affirmation of Ukraine’s

division between the USSR and Poland. Northern

Bukovyna became part of the Kingdom of Roma-

nia, while Transcarpathia found itself within a

newly created Czechoslovak republic.

INTERWAR UKRAINE

The Ukrainian territories under Bolshevik control

had been constituted as the Ukrainian Soviet So-

cialist Republic, which in 1922 became a founding

member of the Soviet Union. Although it possessed

all the structures and symbols of an independent

state, Soviet Ukraine was effectively governed from

Moscow. During the early years of Bolshevik rule,

the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine, or

CP(b)U, was predominantly Russian and Jewish in

its ethnic composition. The proportion of Ukraini-

ans increased to some 20 percent only in 1920,

after the absorption of the Borotbisty, a non-

Bolshevik communist party in Ukraine. Still, the

CP(b)U always remained an integral part of the All-

Union Communist Party.

During the 1920s, in order to reach out to the

overwhelmingly peasant population and disarm

the appeal of Ukrainian nationalism, the Bolshe-

viks pursued the policy of Ukrainization. This af-

firmative action program fostered education,

publishing, and official communication in the

Ukrainian language, and sponsored the recruit-

ment of Ukrainians to party and government

structures. By the late 1920s the proportion of eth-

nic Ukrainians in the CP(b)U exceeded 50 percent.

The Ukrainization drive eventually caused resis-

tance among Russian bureaucrats in Ukraine and

uneasiness in Moscow. Yet, some Ukrainian Bol-

sheviks, led by the vocal Mykola Skrypnyk,

defended the policy of Ukrainization. Peasant re-

sistance to the forcible collectivization of agricul-

ture during the First Five-Year Plan (1928–1932)

led to Moscow’s denunciation of Ukrainization and

its defenders. Skrypnyk killed himself in 1933, the

same year that millions of Ukrainian peasants

died in a catastrophic famine, which was caused

by state policies. Ukrainian cultural figures suf-

fered disproportionately during the Great Terror.

Stalinist-era industrialization, however, turned the

Ukrainian republic into a developed industrial re-

gion.

In interwar Poland and Romania, Ukrainians ex-

perienced discrimination and assimilationist pressure.

By the mid-1930s, popular discontent with the in-

ability of mainstream Ukrainian political parties,

such as the National Democrats, to counter Polish

oppression, propelled Ukrainian radical nationalists

to prominence. The conspiratorial Organization of

Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN, founded in 1929)

became increasingly influential among Ukrainian

youth. The situation was different in Czechoslova-

kia, where the government promoted multicultural-

ism and modernized the economy in Transcarpathia.

When Hitler began dismembering Czechoslovakia in

1938, this region was granted autonomy and briefly

enjoyed independence as Carpatho-Ukraine before be-

ing occupied by Hungary.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (August 1939)

transferred Poland’s Ukrainian territories and Ro-

mania’s Northern Bukovyna to the Soviet sphere

of influence. The USSR occupied these regions in

September 1939 and June 1940, respectively, un-

der the guise of reuniting the Ukrainian nation

within a single state structure. The OUN had just

split into a more moderate wing led by Andrii Mel-

nyk and a more radical one under the leadership

of Stepan Bandera. The infighting between the

OUN(M) and OUN(B) effectively prevented radical

nationalists from putting up any resistance.

WORLD WAR II AND THE LATE

SOVIET PERIOD

The surprise Nazi attack on the USSR in June 1941

turned the Ukrainian republic into a battlefield. The

Germans scored one of the war’s biggest victories

when they took Kiev in September at a cost of

600,000 Soviet fatalities and an equal number of

soldiers who were taken prisoner. By the end of

1941 the German armies controlled practically all

UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

1603

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY