Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

warks against invasion from the south and east,

they were also sensitive to infringements of their

rights and privileges as free men. From the time of

Stepan Razin’s revolt in 1670–1671 until the ris-

ing of Yemelian Pugachev in 1772–1775, they pe-

riodically reacted explosively to encroachments

against their status and freebooting lifestyle.

The service and free Cossack traditions gradually

merged during the eighteenth and early nineteenth

centuries, when the former free Cossack groupings

were either abolished (e.g., the Zaporozhian Sich in

1775) or brought under the complete control (e.g.,

the Don Host also in 1775) of imperial St. Peters-

burg. A series of imperial military administrators

from Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin through

Alexander Ivanovich Chernyshev imposed measures

that regularized Cossack military service, subordi-

nated local governing institutions to imperial control

and supervision, and integrated local elites into the

ranks of the Russian nobility. Regardless of origin,

by the time of the Crimean War in 1854–1856, all

Cossacks had been transformed into a closed military

estate (sosloviye) subject to mandatory mounted mil-

itary service in exchange for collective title to their

lands and superficial reaffirmation of traditional

rights and privileges. During the Great Reform Era,

War Minister Dmitry Alexeyevich Milyutin toyed

briefly with the idea of abolishing the Cossacks, then

imposed measures to further regularize their gover-

nance and military service. The blunt fact was that

the Russian army needed cavalry, and the Cossack

population base of 2.5 million enabled them to sat-

isfy approximately 50 percent of the empire’s cav-

alry requirements. Consequently, the Cossacks

became an anachronism in an age of smokeless pow-

der weaponry and mass cadre and conscript armies.

Reforms notwithstanding, by the beginning of

the twentieth century, many traditional Cossack

groupings hovered on the verge of crisis, thanks to

a heavy burden of military service, overcrowding in

communal holdings, alienation of land by the Cos-

sack nobility, and an influx of non-Cossack popu-

lation. The revolutions of 1917 and the ensuing

Russian Civil War seriously divided the Cossacks,

COSSACKS

333

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

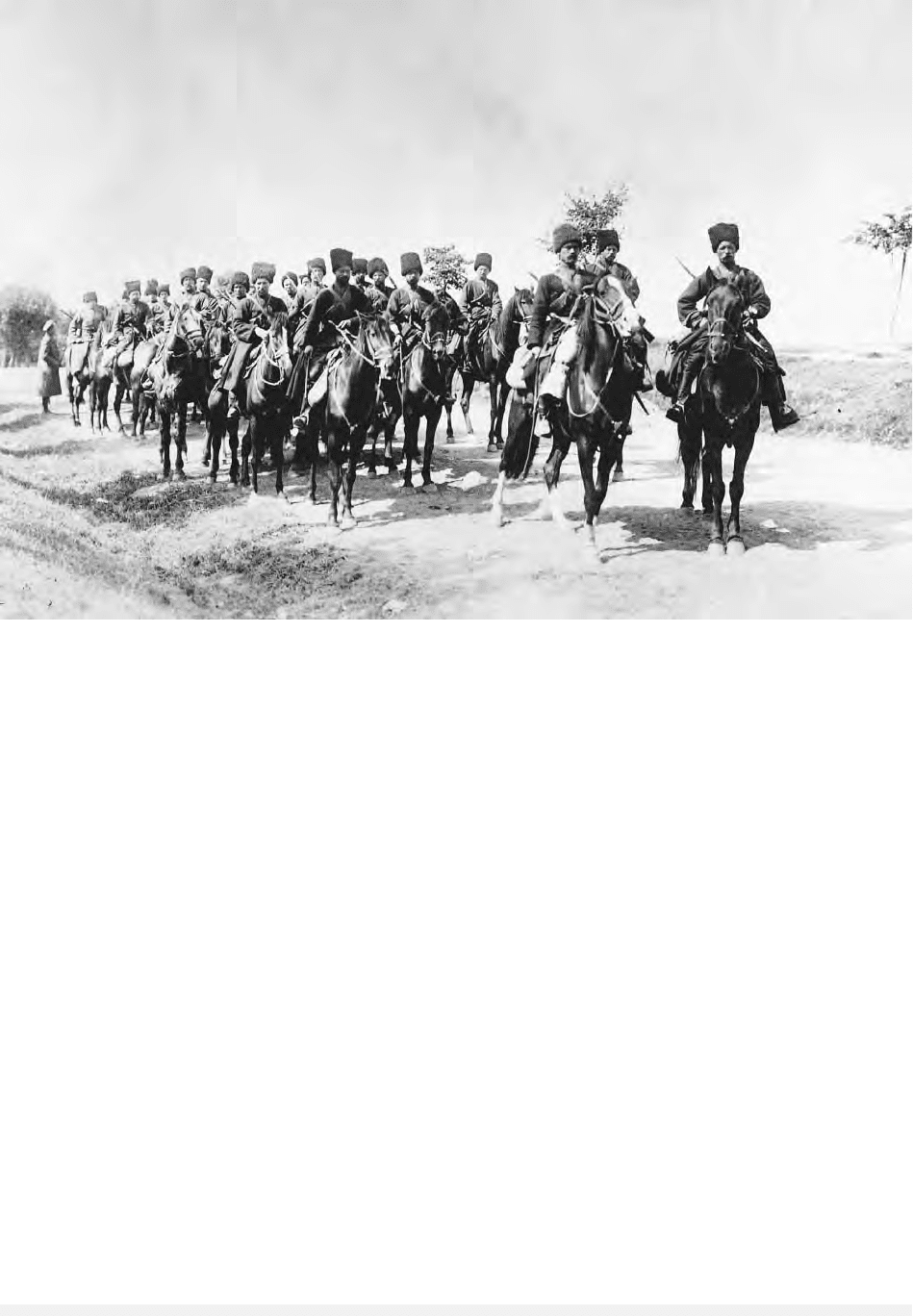

Cossacks on the march, 1914. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

with a majority supporting the White movement,

while a stubborn minority espoused revolutionary

causes. Following Bolshevik victory, many Cossacks

fled abroad, while those who stayed were persecuted,

gradually disappearing during collectivization as an

identifiable group. During World War II, the Red

Army resurrected Cossack formations, while the

Wehrmacht, operating under the fiction that Cos-

sacks were non-Slavic peoples, recruited its own

Cossack formations from prisoners of war and dis-

sidents of various stripes. Neither variety had much

in common with their earlier namesakes, save per-

haps either remote parentage or territorial affinity.

The same assertion held true for various Cossack-

like groupings that sprang up in trouble spots

around the periphery of the Russian Federation fol-

lowing the disintegration of the Soviet Union in

1991.

See also: CAUCASUS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET;

NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST; UKRAINE AND

UKRAINIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barrett, Thomas M. (1999). At the Edge of Empire: The

Terek Cossacks and the North Caucasus Frontier,

1700–1860. Boulder: Westview Press.

Khodarkovsky, Michael. (2002). Russia’s Steppe Frontier:

The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500–1800. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

McNeal, Robert H. (1987). Tsar and Cossack, 1855–1914.

London: The Macmillan Press.

McNeill, William H. (1964). Europe’s Steppe Frontier

1500–1800. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Menning, Bruce W. (2003). “G. A. Potemkin and A. I.

Chernyshev: Two Dimensions of Reform and Rus-

sia’s Military Frontier.” In Reforming the Tsar’s Army:

Military Innovation in Imperial Russia from Peter the

Great to the Revolution, eds. David Schimmelpenninck

van der Oye and Bruce W. Menning. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Subtelny, Orest. (2000). Ukraine: A History, 3rd ed.

Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

COUNCIL FOR MUTUAL

ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE

The decision to establish the Council for Mutual

Economic Assistance, also known as COMECON

and the CMEA, was announced in a joint commu-

niqué issued by Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hun-

gary, Poland, Romania, and the Soviet Union in

January 1949. Albania joined in February 1949;

East Germany in 1950; Mongolia in 1962; Cuba in

1972, and Vietnam in 1978. Albania ceased par-

ticipation in 1961.

COMECON members were united by their com-

mitment to Marxism–Leninism, Soviet–style central

planning, and economic development. COMECON

served as an organizational counterweight first to

the Marshall Plan and then to the European Iron

and Steel Community and its successor, the Euro-

pean Economic Community.

COMECON was effectively directed by a group

outside its formal organization, the Conference

of First Secretaries of Communist and Workers’

Parties and of the Heads of Government of COME-

CON Member Countries. The Soviet Union domi-

nated COMECON. From 1949 to 1953, Stalin used

COMECON primarily to redirect member trade

from outside COMECON to within COMECON and

to promote substitution of domestic production for

imports from outside COMECON. The COMECON

economic integration function was stepped up in

1956, the year of the Soviet invasion of Hungary,

with the establishment of eight standing commis-

sions, each planning for a different economic sec-

tor across the member countries. Notable real

achievements included partial unification of electric

power grids across East European members, coor-

dination of rail and river transport in Eastern Eu-

rope, and the construction of the Friendship pipeline

to deliver Siberian oil to Eastern Europe. In 1971

COMECON initiated a compromise Comprehensive

Program for Socialist Economic Integration as a

counterweight to integration within the European

Economic Community. COMECON continued plan-

ning various integration and coordination efforts

through the 1970s and 1980s. In 1985-1986 these

efforts culminated in the Comprehensive Program

for Scientific and Technical Progress to the Year

2000. With the loss of Soviet control over its East

European trading partners, COMECON tried to sur-

vive as a purely coordinating body but was finally

formally disbanded in June 1991.

COMECON’s impact on Russia was largely eco-

nomic. Russia was the largest republic among the

Soviet Union’s fifteen republics. The Soviet Union

was the dominant member of COMECON. The

strategic purpose of COMECON was to tie Eastern

Europe economically to the Soviet Union. COME-

CON trade became largely bilateral with the Soviet

Union, mostly Russia, supplying raw materials, no-

COUNCIL FOR MUTUAL ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE

334

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tably oil, to Eastern Europe in return for manufac-

tured goods, notably machinery and equipment.

This is the opposite of the trade flow between his-

torically dominant countries and their colonies and

dependents. The historical norm is for raw materi-

als to flow from the colonies and dependents to the

dominant center, which exports advanced manu-

factures and services in return. The comparative ad-

vantage for Russia within COMECON was,

however, as a raw material and fuel exporter. Rus-

sia’s loss was that it received in return shoddy and

obsolescent COMECON machinery and equipment

rather than Western machinery with Western tech-

nology embedded in it. The Comprehensive Program

for Scientific and Technical Progress to the Year

2000 was only one effort to remedy this problem.

Russia also lost out on its potential gains from

OPEC’s increase in the price of oil beginning in 1973.

COMECON trade was conducted in “transfer-

able rubles,” basically a bookkeeping unit good only

to buy imports from other COMECON partners.

However, most purchases and their prices were bi-

laterally negotiated between the COMECON trade

partners. So, the real value of a country’s trans-

ferable ruble balance was indeterminate. Russian oil

was sold by the Soviet Union to COMECON part-

ners for transferable rubles. OPEC dramatically in-

creased the dollar value of oil exports beginning in

1973. In 1975 COMECON agreed that the trans-

ferable ruble price of oil be indexed to the global

dollar price, specifically the moving average for the

past three years in 1975 and the past five years for

every year thereafter. Thus, the prices of Soviet oil

exports to COMECON lagged the global price rises

through the late 1970s. Only when global oil prices

dropped in the early 1980s did the transferable ru-

ble price of Soviet oil catch up. Overall, the Soviet

Union paid for its East European “empire” by sell-

ing its raw inputs, especially oil, for less than world

market prices and by receiving less technologically

advanced manufactured goods in return. Much of

this cost was borne by Russia.

See also: ELECTRICITY GRID; EMPIRE, USSR AS; FOREIGN

TRADE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brabant, Jozef M. van. (1980). Socialist Economic Inte-

gration: Aspects of Contemporary Economic Problems in

Eastern Europe. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

Marrese, Michael, and Vanous, Jan. (1983). Soviet Sub-

sidization of Trade with Eastern Europe: A Soviet Per-

spective. Berkeley, CA: Institute of International

Studies, University of California.

Metcalf, Lee Kendall. (1997). The Council of Mutual Eco-

nomic Assistance: The Failure of Reform. New York:

Columbia University Press.

Zwass, Adam. (1989). The Council for Mutual Economic

Assistance: The Thorny Path from Political to Economic

Integration. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

D

ANIEL

R. K

AZMER

COUNCIL OF MINISTERS, IMPERIAL See CAB-

INET OF MINISTERS, IMPERIAL.

COUNCIL OF MINISTERS, SOVIET

In 1946, Sovnarkom—Sovet Ministrov, the gov-

ernment of the USSR—was renamed the Council of

Ministers to bring the USSR into line with practice

in other great powers. Josef Stalin remained as

chairperson until 1953. He was followed by Georgy

Malenkov until 1955; then Nikolai Bulganin until

1958; Nikita Khrushchev, from 1958 to 1964;

Alexei Kosygin, 1964–1980; Nikolai Tikhonov,

1980–1985; and Nikolai Ryzhkov, 1985–1990.

Membership of the Council of Ministers consisted

of the chairperson, first deputy chairperson, deputy

chairpersons, ministers of the USSR and chairper-

sons of State Committees of the USSR. Chairper-

sons of Councils of Ministers of Union republics

were ex officio members of the Council of Minis-

ters of the USSR. Under the 1977 constitution

membership could also include “the heads of other

organs and organizations of the USSR.” This al-

lowed the chairperson of the Central Council of

Trade Unions or the first secretary of the Com-

munist Youth League (Komsomol) to serve on the

Council of Ministers. The first Council of Ministers

formed under this constitution comprised 109

members.

Ministries and State Committees, as with the

commissariats in Sovnarkom, were of two varieties:

“union-republican,” which functioned through par-

allel apparatuses in identically named republican

ministries, and “all-union,” which worked by direct

control of institutions in the republics or through

organs in the republics directly subordinate to the

USSR minister. Groups of related ministries were

supervised by senior Party leaders serving as deputy

chairpersons of the Council of Ministers. In the early

postwar years the tendency toward subdivision of

COUNCIL OF MINISTERS, SOVIET

335

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ministries, apparent in Sovnarkom during the

1930s, continued until 1948, but it was then fol-

lowed by a period of amalgamation until 1949, and

more modest expansion until 1953. Immediately af-

ter Stalin’s death membership of the Council of Min-

isters was reduced from eighty-six to fifty-five,

groups of economic ministries being amalgamated,

but this was only temporary, and by the end of

1954 membership had increased again to seventy-

six and continued to increase more slowly from that

time.

Theoretically responsible and accountable to the

Supreme Soviet of the USSR, with membership sup-

posedly decided by that institution, but in reality

by the Politburo, the Council of Ministers was em-

powered to deal with all matters of state adminis-

tration of the USSR outside the competence of the

Supreme Soviet, issuing decrees and ordinances and

verifying their execution. According to the 1936 and

1977 Constitutions, the Council of Ministers was

responsible for direction of the national economy

and economic development; social and cultural de-

velopment, including science and technology; the

state budget; planning; defense, state security; gen-

eral direction of the armed forces; foreign policy;

foreign trade and economic; and cultural and sci-

entific cooperation with foreign countries.

By a law of 1978, meetings of the Council of

Ministers were to be convened every three months

and sessions of its Presidium “regularly (when the

need arises).” This institution, created in 1953, con-

sisting of the chairperson, first deputy chairperson

and deputy chairpersons of the Council of Minis-

ters, functioned only intermittently until 1978. Of-

ten described in Western literature as an “inner

cabinet,” it then became primarily responsible for

the directions of economic affairs.

See also: BULGANIN, NIKOLAI ALEXANDROVICH; BUREAU-

CRACY, ECONOMIC; KHRUSHCHEV, NIKITA SERGEY-

VICH; KOSYGIN, ALEXEI NIKOLAYEVICH; SOVNARKOM;

STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH; STATE COMMITTEES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Unger, Aryeh. (1981). Constitutional Development in the

USSR: A Guide to the Soviet Constitutions. London:

Methuen.

D

EREK

W

ATSON

COUNCIL OF PEOPLE’S COMMISSARS See

SOVNARKOM.

COUNTERREFORMS

The Counterreforms of the 1880s and 1890s refer

to the body of domestic policies adopted under Tsar

Alexander III as an ideological response and reac-

tion to the transformations of the earlier Great Re-

forms undertaken by so-called “enlightened”

bureaucrats with the tacit approval of the assassi-

nated Tsar Alexander II. They were also a response

to radicalism growing out of the reform milieu.

The conservatives believed the Empire was threat-

ened. Whereas the Great Reforms of the period

1855–1881 in the broadest sense intended to ren-

ovate the body politic and instill new principles of

self-government, rule of law, citizenship, and even

to introduce at the very end a veiled form of elite

representation in the legislative process, the coun-

terreforms of the new Tsar and his conservative ad-

visers within and outside the bureaucracy aimed to

reverse such changes and to reassert traditional au-

tocracy and nationhood and the more manageable

and corporatist society organized by legal estates.

Immediately after Alexander II’s assassination in

March 1881, the new government moved quickly

to remove Loris-Melikov and remaining reformers

from the government. On April 29, 1881, the Tsar

declared that Russia would always remain an au-

tocracy. The reform era was over.

The counterreforms were ushered in by the

laws on state order and the pacification of society

of August 14, 1881. These laws, sponsored by Min-

ister of Internal Affairs, N. P. Ignat’ev, provided for

two types of martial law (condition of safeguard

and extraordinary safeguard) that gave the police

and administration enhanced powers above and be-

yond those residing in the new judicial system.

These decrees remained in force until just days be-

fore the February Revolution of 1917. On August

27, 1882, the government introduced “temporary

rules on the press,” which gave more censorship

power to the administration. Minister of Internal

Affairs D. A. Tolstoy then introduced a new Uni-

versity Statute on August 23, 1884. This effectively

repealed university corporate autonomy and bu-

reaucratized the administration of higher educa-

tion. It also placed limits on higher education for

women. Finally a cluster of three major acts placed

new administrative restrictions on the institutions

of self-government, the zemstvos and town dumas.

These laws of June 12, 1890 (zemstvo) and June

11, 1892 (town duma) changed the electoral laws

to favor the gentry in the case of the zemstvos and

large property owners in the cities. Many recent

COUNTERREFORMS

336

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

voters in town and countryside alike were disen-

franchised. In addition new bureaucratic instances

were established to shore up administrative control

over self-government. This would call forth oppo-

sition in the form of a zemstvo movement that

would be instrumental in the 1905 Revolution. Per-

haps most symbolic of all the counterreforms was

the notorious act of July 12, 1889 that created the

Land Captains (zemskie nachal’niki). These were ap-

pointed government officials in the countryside

who combined administrative, police, and judicial

authority. The aim was once again administrative

control, this time over the relatively new peasant

institutions and indeed over peasant life in the

broadest sense. Control rather than building a new

society from the grassroots was the central point

of these counterreforms. The counterreforms and

their supporting ideology extended into the reign

of Nicholas II, making it that much more difficult

for the regime to solve its social and political prob-

lems. They in fact made revolution more likely. The

counterreforms co-existed uneasily with more for-

ward-looking economic policies even during the

reign of Alexander III.

See also: ALEXANDER III, NICHOLAS II

D

ANIEL

O

RLOVSKY

COUNTRY ESTATES

Country estates, some dating back to the fifteenth

century, originated as land grants from the crown

to trusted servitors. The Russian empire expanded

rapidly, particularly in the eighteenth century, and

along with it the estate network, which ultimately

stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Crimean Penin-

sula, and from the Duchy of Warsaw to the Ural

Mountains. During the estate’s golden age from the

reign of Catherine II to the War of 1812, wealthy

nobles who had retired from state service built

thousands of magnificent houses, most in neoclas-

sical style, surrounded by elegant formal gardens

and expansive landscape parks.

Until the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, es-

tates were private princedoms (owned exclusively

by nobles) supported by involuntary labor. Thus

in some respects the pre-emancipation estate was

comparable to the plantation of the American

south. Its uniqueness lay in its scores of highly

trained serf craftsmen and artists, some of whom

founded dynasties of acclaimed artists. Very

wealthy landowners took pride in having at hand

accomplished architects and painters, musicians,

actors, and dancers for entertainment, and cabi-

netmakers, gilders, embroiderers, lace-makers and

other skilled craftsmen who produced all the lux-

ury items they needed. Hence the greatest estates,

in addition to being economic centers, were also

culturally self-contained worlds that facilitated the

rapid development of Russian culture.

Estates also served as important places of in-

spiration and creativity for Russia’s most renowned

authors, painters, and composers. For the intellec-

tual and artistic elite, country estates were Arca-

dian retreats, places of refuge from the constraints

of city life. Alexander Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, Ivan

Turgenev’s A Sportsman’s Sketches and Fathers and

Sons, Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Anna Karen-

ina, and Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture are

among the many Russian masterpieces composed

on a country estate.

After 1861 many small estate owners, unable

to survive the loss of their unpaid labor, sold their

holdings (a situation memorialized in Anton

Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard). On larger estates a

system similar to sharecropping was devised; these

estates retained their economic strength until the

revolution. Up to World War I Russia exported

tons of grains and other agricultural products pro-

duced on thousands of country estates. In non-

black-earth (non-chernozem) regions, enterprises

on estates such as Khmelita (Smolensk guberniya),

exporting prize-winning cheeses, Glubokoye (Pskov

guberniya), producing wooden lanterns sold in

England, and Polotnyany Zavod (Kaluga gu-

berniya), which manufactured the linen paper used

for Russian currency, also contributed to the econ-

omy.

The Bolshevik revolution destroyed the coun-

try estate, and with it much of the provincial eco-

nomic and cultural infrastructure. Some estate

houses have survived as orphanages, sanitariums,

institutes, or spas. In the 1970s certain demolished

estates associated with famous cultural figures

(such as Pushkin’s Mikhailovskoye and Turgenev’s

Spasskoye-Lutovinovo) were rebuilt. A few mu-

seum estates such as Kuskovo and Ostankino in

Moscow and the battered manor houses of the

Crimea still offer tourists a glimpse of Russia’s pre-

Revolutionary estate splendor.

See also: PEASANTRY; SERFDOM; SLAVERY

COUNTRY ESTATES

337

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blum, Jerome. (1961). Lord and Peasant in Russia. Prince-

ton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Roosevelt, Priscilla. (1995). Life on the Russian Country Es-

tate: A Social and Cultural History. New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press.

P

RISCILLA

R

OOSEVELT

COURT, HIGH ARBITRATION

The High Arbitration Court is at the top of the sys-

tem of arbitration courts. These courts were orig-

inally created in the Soviet period as informal

tribunals to resolve problems in implementing eco-

nomic plans. In the post-communist era they have

been reorganized into a system of courts with ex-

clusive jurisdiction over lawsuits among businesses

and between businesses and government agencies.

While for historical reasons they are called “arbi-

tration” courts, in fact they are formal state courts

with compulsory jurisdiction and have nothing to

do with private arbitration of disputes.

The structure of the courts is governed by the

1995 Constitutional Law on Arbitration Courts.

Beneath the High Arbitration Court there are ten

appellate courts, each with jurisdiction over a sep-

arate large area of the country, and numerous trial

courts. The High Arbitration Court is responsible

for the management of the entire arbitration court

system. Procedural rules are provided by the 2002

Arbitration Procedure Code. Cases are heard in the

first instance in the trial court. Either party may

then appeal to an appellate instance within the trial

court, and may further appeal to the appropriate

appellate court. There is no right to appeal to the

High Arbitration Court; rather, review by the High

Arbitration Court is discretionary with the Court.

The High Arbitration Court has original jurisdic-

tion over two types of cases: (1) those concerning

the legality of acts of the Federation Council, the

State Duma, the president, or the government; and

(2) economic disputes between the Russian Federa-

tion and one of its eighty–nine subjects. The High

Arbitration Court also has, and frequently exer-

cises, the power to issue explanations on matters

of judicial practice, for the guidance of the lower

courts, lawyers, and the public. The Court also

publishes many of its decisions in individual cases

on the Internet.

See also: COURT, SUPREME; LEGAL SYSTEMS.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hendley, Kathryn. (1998). “Remaking an Institution: The

Transition in Russia from State Arbitrazh to Arbi-

trazh Courts.” American Journal of Comparative Law

46:93-127.

Hendley, Kathryn; Murrell, Peter; and Ryterman, Randi.

(2001). “Law Works in Russia: The Role of Law in

Interenterprise Transactions.” In Assessing the Value

of Law in Transition Economies, ed. Peter Murrell. Ann

Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Oda, Hiroshi. (2002). Russian Commercial Law. The

Hague, Netherlands: Kluwer Law International.

P

ETER

B. M

AGGS

COURT, SUPREME

The Supreme Court is “the highest judicial body for

civil, criminal, administrative and other cases

falling within the jurisdiction of courts of general

jurisdiction” under Article 126 of the Russian Con-

stitution. The courts of general jurisdiction hear all

cases except: (1) lawsuits among businesses and be-

tween businesses and government agencies, which

are heard by the Arbitration Court system; and (2)

certain Constitutional issues, which are heard by

the Constitutional Court. Beneath the Supreme

Court are the highest courts of each of the

eighty–nine subjects of the Russian Federation and

the military courts. Beneath the courts of the sub-

jects of the Russian Federation are a large number

of district courts. Still lower in the hierarchy are

Justice of the Peace Courts, which deal with rela-

tively unimportant cases. The court structure and

the relations between the courts are governed by

the 1996 Constitutional Law on the Judicial Sys-

tem of the Russian Federation. Procedural rules are

provided by the 2001 Criminal Procedure Code and

the 2002 Civil Procedure Code.

The Supreme Court has separate divisions for

civil cases, criminal cases, and military cases. It has

a President and a Presidium consisting of several

high officers of the court. It also has a plenary ses-

sion in which all the judges meet together. The Ju-

dicial Department of the Supreme Court handles

the administration of all the courts of general ju-

risdiction. Most cases are heard by the Supreme

Court on appeal from or petition for review of

lower court decisions. Because the court sits in sep-

arate divisions and has a large number of judges,

it is able to review a very large number of lower

court cases. However, a few very important cases

COURT, HIGH ARBITRATION

338

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

are heard by the Court in first instance. There is a

mechanism for an appeal of these decisions to a

higher level of the Supreme Court itself. The ple-

nary session of the Court also has the power to is-

sue interpretations of the law for the guidance of

the lower courts. The interpretations and many

other Court decisions are published at its web site.

As the result of easy availability of these interpre-

tations and decisions, lawyers are increasingly

studying and citing Supreme Court rulings.

The Supreme Court has in some cases refused

to apply statute laws on the basis that they con-

tradicted the Constitution. Gradually, however, its

policy changed. When in doubt on the constitu-

tionality of a law, the Supreme Court has typically

referred the question to the Constitutional Court.

However, the Supreme Court frequently hears cases

concerning the conformity of administrative regu-

lations to the Constitution and laws, and fre-

quently invalidates such regulations. The Supreme

Court of the twenty–first century is very different

from the Supreme Court of the Soviet period, even

though the court structure is little changed. In the

Soviet period the Court was subservient to the

Party authorities. The court did not control judi-

cial administration, which was managed by the

Ministry of Justice. It did cite the Constitution, but

never refused to apply a law on the basis of the

Constitution alone.

See also: COURT, HIGH ARBITRATION; LEGAL SYSTEMS.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Burnham, William, and Danilenko, Gennady M. (2000).

Law and Legal System of the Russian Federation, 2nd

ed. Huntington, NY: Juris.

Krug, Peter. (1997). “Departure from the Centralized

Model: the Russian Supreme Court and Constitu-

tional Control of Legislation.” Virginia Journal of

International Law 37:725-786.

Maggs, Peter B. (1997) “The Russian Courts and the

Russian Constitution.” Indiana International and

Comparative Law Review 8:99-117.

P

ETER

B. M

AGGS

CRIMEA

Russian hegemony was established over the Crimea

region in 1783 when the Tsarist empire destroyed

the Crimean Tatar state. By the second half of the

nineteenth century the Crimean population had de-

clined to 200,000, of which half were Tatars. This

proportion continued to decline as Slav migration

to the region continued in the next century through

industrialization, the building of the Black Sea Fleet,

and tourism. By the 1897 and 1926 censuses the

Tatar share of the population had declined to 34

and 26 percent respectively.

During the civil war of 1917–1922, Crimea

was claimed by the independent Ukrainian state,

which obtained it under the terms of the 1918

Brest-Litovsk Treaty. But Crimea was also the scene

of conflict between the Whites and Bolsheviks. In

October 1921 Crimea was included within the

Russian Federation (RSFSR) as an autonomous re-

public with two cities (Sevastopol and Evpatoria)

under all-union jurisdiction.

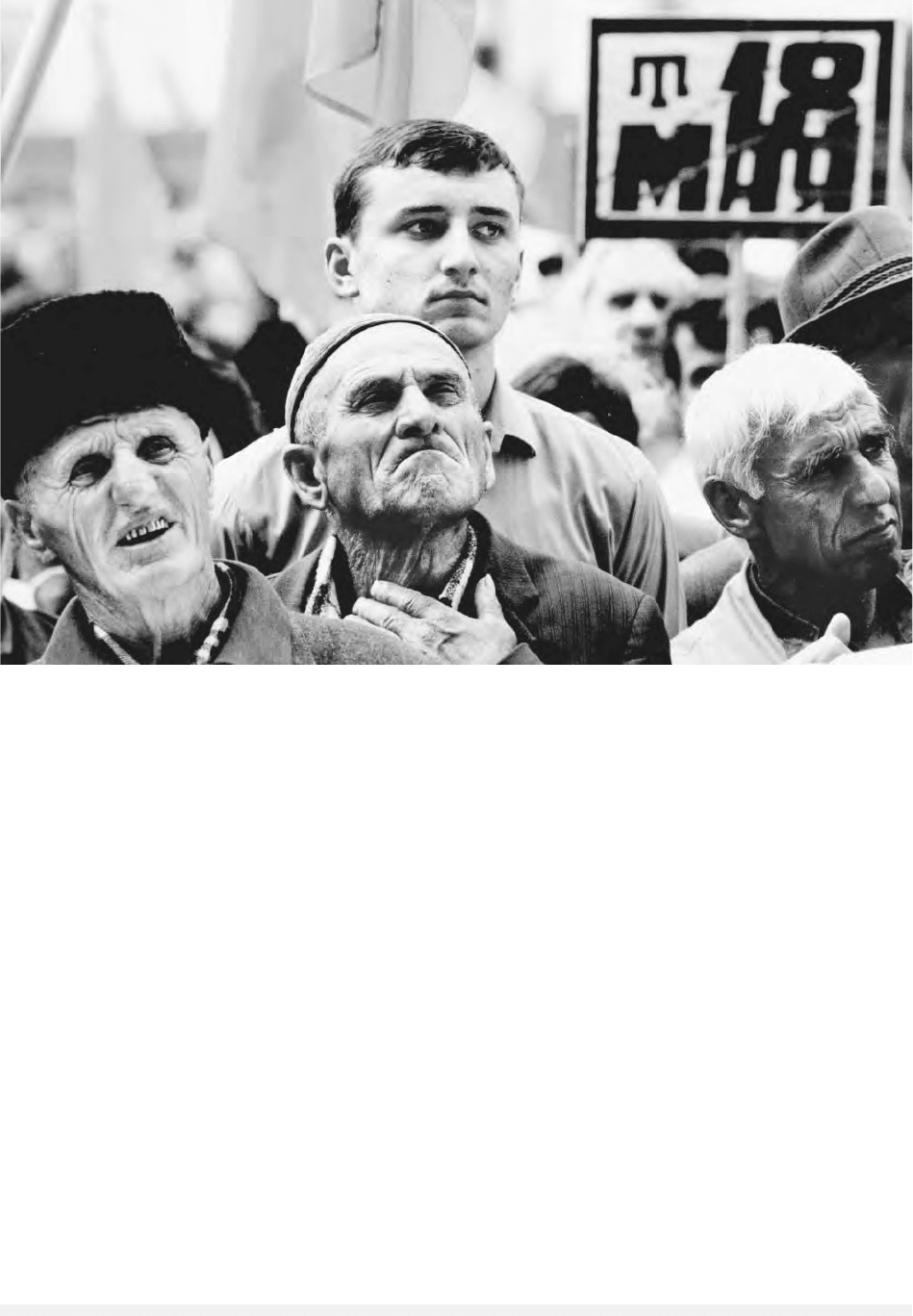

Crimea’s ethnic composition changed in May

1944 when nearly 200,000 Tatars and 60,000

other minorities were deported to Central Asia. It

is estimated that up to 40 percent of the Tatars died

during the deportation. A year later Crimean au-

tonomy was formally abolished, and the peninsula

was downgraded to the status of oblast (region) of

the Russian Federation. All vestiges of Tatar influ-

ence were eradicated.

Crimea’s status was again changed in 1954

when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev transferred

it to the Ukrainian SSR. It remained an oblast un-

til 1991, when a popularly supported referendum

restored its status to an autonomous republic

within Ukraine. Tatars began to return to Crimea

in the Gorbachev era, but they still only accounted

for 15 percent of the population, with the remain-

der of the population divided between Russians

(two-thirds) and russified Ukrainians.

The status of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol,

and the division of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet sta-

tioned on the peninsula, were the object of acri-

monious dispute between Ukraine and Russia in the

post-Soviet era. The Russian parliament repeatedly

voted to demand that Ukraine return both Crimea

and Sevastopol. Furthermore, the parliament ar-

gued that legally they were Russian territory and

that Russia, as the successor state to the USSR, had

the right to inherit Sevastopol and the Black Sea

Fleet.

This dispute was not resolved until May 1997,

when Ukraine and Russia signed a treaty that rec-

ognized each other’s borders. The treaty was

quickly ratified by the Ukrainian parliament

(Rada), but both houses of the Russian parliament

CRIMEA

339

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

only ratified it after intense lobbying from Ukraine

in October 1998 and February 1999.

The resolution of the question of the owner-

ship of Crimea and Sevastopol between 1997 and

1999 also assisted in the division of the Black Sea

Fleet. Russia inherited 80 percent of the fleet and

obtained basing rights scheduled to expire in 2017.

The situation was also stabilized by Crimea’s adop-

tion in October 1998 of a constitution that for the

first time recognized Ukraine’s sovereignty.

Within Crimea the Tatars have been able to mo-

bilize large demonstrations, but their small size has

prevented them from having any significant influ-

ence on the peninsula’s politics. Between 1991 and

1993 the former communist leadership of Crimea,

led by Mykola Bagrov, attempted to obtain signif-

icant concessions from Kiev in an attempt to max-

imize Crimea’s autonomy. This autonomist line

was replaced by a pro-Russian secessionist move-

ment that was the most influential political force

between 1993 and 1994; its leader Yuri Meshkov

was elected Crimean president in January 1994. The

secessionist movement collapsed between 1994 and

1995 due to internal quarrels, lack of substantial

Russian assistance, and Ukrainian economic, polit-

ical, and military pressure. The institution of a

Crimean presidency was abolished in March 1995.

From 1998 to 2002 the peninsula was led by Com-

munists, who controlled the local parliament, and

pro-Ukrainian presidential centrists in the regional

government. In the 2002 elections the Communists

lost their majority in the local parliament, and it,

like the regional government, came under the con-

trol of pro-Ukrainian presidential centrists.

See also: BLACK SEA FLEET; CRIMEAN KHANATE; CRIMEAN

TATARS; CRIMEAN WAR; SEVASTOPOL; TATARSTAN

AND TATARS; UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allworth, Edward, ed. (1988). Tatars of the Crimea: Their

Struggle for Survival. Durham, NC: Duke University

Press.

Kuzio, Taras. (1994). “The Crimea and European Secu-

rity.” European Security 3(4): 734–774.

Kuzio, Taras. (1998). Ukraine: State and Nation Building

(Routledge Studies of Societies in Transition, 9). Lon-

don: Routledge.

Lazzerini, Edward. (1996). “Crimean Tatars.” In The Na-

tionalities Question in the Post-Soviet States, ed. Gra-

ham Smith. London: Longman.

T

ARAS

K

UZIO

CRIMEAN KHANATE

One of the surviving political elements of the

Golden Horde, the Crimean Khanate comprised all

of the Crimean peninsula, except for the southern

and western coast, which was a province of the Ot-

toman Empire after 1475 (Kefe Eyalet), and sur-

vived until 1783 when it was annexed by the

Russian Empire. The Khanate’s ruling dynasty, the

Girays, established its residence and “capital” in the

valley of Bahçe Saray, from which it ruled most of

the peninsula, and conducted relations with the Ot-

tomans in the south.

Among the early Crimean khans, most impor-

tant were Mengli Giray I (1467–1476 and

1478–1515), who is considered the “founder” of

the Khanate; Sahib Giray I (1532–1551), who com-

peted with Ivan IV for control of Kazan and As-

trakhan, and lost; and Devlet Giray I (1551–1577),

who led a campaign against Moscow. It was Mengli

Giray who used Italian architects to build the large

khan’s palace and the important Zincirli Medrese

in Bahçe Saray and, through patronizing artists

and writers, establishing the khanate as a Sunni

Muslim cultural center.

The khanate had a special relationship with the

Ottoman Empire. Never Ottoman subjects, the

Khanate’s Giray dynasty was considered the cru-

cial link between the Ottomans and the Mongols,

particularly Ghenghis Khan. Had the Ottoman dy-

nasty died out, the next Ottoman sultan would

have been selected from the Giray family. Through-

out the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Gi-

rays often provided military support for Ottoman

campaigns, in Hungary and in Iran. Crimean

mounted archers were considered by the Ottomans

to be among the most reliable and effective elements

of their armies.

So far as the Russians were concerned, the most

important feature of the khanate was the latter’s

dependence on raiding Muscovite lands for eco-

nomic benefit. Crimean Tatars frequently “har-

vested the steppe” and brought Russian, Ukrainian,

and Polish peasants to Crimea for sale. Slave mar-

kets operated in Kefe and Gozleve, where merchants

from the Ottoman Empire, Iran, and Egypt pur-

chased Slavic slaves for export. Several raids reached

as far as Moscow itself. Slave market tax records

indicate that more than a million were sold in

Crimea in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

CRIMEAN KHANATE

340

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Eighteenth-century Russian governments tried

to bring an end to these raids. An invasion of

Crimea in 1736 succeeded in destroying much of

the khanate’s capital Bahçesaray, including the

palace, though the Russian army soon abandoned

that effort. The Girays were able to rebuild much

of the city over the next ten years.

It was left to Catherine II to bring an end the

khanate, in 1783. Russian victories over the Ot-

tomans resulted in, first, the Treaty of Karasu

Bazaar between Russia and the Khanate in No-

vember 1772, followed by the Treaty of Küçük

Kaynarca between Russia and the Ottoman Empire

in 1774. Karasu Bazaar established an “alliance and

eternal friendship” between the khanate and Rus-

sia; the second cut all ties between the khanate and

the Ottoman Empire.

For nine years, Catherine II worked with the

last Crimean Khan, Šahin Giray, in an experiment

in “independence,” implementing some of her “en-

lightened” political ideas in a Muslim, Tatar soci-

ety. Recognizing failure in this venture, Catherine

annexed the khanate and the rest of the Crimean

peninsula to the empire in 1783.

See also: CATHERINE II; CRIMEAN TATARS; GOLDEN HORDE;

NATIONALISM IN TSARIST EMPIRE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fisher, Alan. (1970). The Russian Annexation of the Crimea,

1772–1783. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Fisher, Alan. (1999). A Precarious Balance: Conflict, Trade,

and Diplomacy on the Russian-Ottoman Frontier. Is-

tanbul: Isis Press.

A

LAN

F

ISHER

CRIMEAN TATARS

A Turkic people who settled the Crimean peninsula

over the two hundred years after Batu Khan’s con-

quest, the Tatars of the Crimea came from Central

Asia and Anatolia. By 1450, almost the whole of

the peninsula north of the coastal mountains was

Tatar land. The Tartat language was a combina-

tion of the Turkish of the Anatolian Seljuks and the

Chagatay Turkic of the Tatar rulers of the Volga

region, though by the end of the fifteenth century,

Crimean Tatar was a dialect different from both.

In the fifteenth century, the Crimean Tatars es-

tablished a state (khanate) and a ruling dynasty

(Giray) with its political center first in Solhat and

later in Bahçesaray. This khanate was closely as-

sociated with the Ottoman Empire to the south,

though it retained its sovereignty. No Ottoman of-

ficials exercised authority within the lands of these

Tatars. Crimean Tatar authors wrote histories and

chronicles that emphasized distinctions between

Tatars and other Turkic peoples, including the Ot-

tomans.

As the Crimean Tatar economy depended on the

slave trade and raids into Russian and other Slavic

lands, it was inevitable that Russia would strive to

gain dominance over the peninsula. But it was only

in the eighteenth century that Russia had sufficient

power to defeat, and, ultimately, annex the penin-

sula and incorporate the remaining Tatars into their

empire. The annexation took place in 1783.

Russian domination put enormous pressures

on the Tatars—causing many to emigrate to the

Balkans and Ottoman Empire during the nine-

teenth century. One of the Tatar intellectuals, Is-

mail Bey Gaspirali, tried to establish an educational

system for the Tatars that would allow them to

survive, as Tatars and as Muslims, within the

Russian Empire. He had substantial influence over

other Turkic Muslims within the empire, an in-

fluence that spread also to Turkish intellectuals in

Istanbul.

Throughout the nineteenth century the Rus-

sian government encouraged Russian and Ukrain-

ian peasants to settle on the peninsula, placing ever

greater pressures on the Tatar population. Al-

though the Revolution of 1917 promised some re-

lief to the Tatars, with the emergence of “national

communism” in non-Russian lands, the Tatar in-

tellectual and political elites were destroyed during

the Stalinist purges.

The German occupation of Crimea after 1941

produced some Crimean Tatar collaboration,

though no greater proportion of Tatars fought

against the USSR than did Ukrainians or Belorus-

sians. Nevertheless, the entire Crimean Tatar na-

tionality was collectively punished in 1944, and

deported en masse to Central Asia, primarily

Uzbekistan. In the 1950s, Crimea was assigned to

the Ukrainian SSR, at the three hundredth an-

niversary of Ukraine’s annexation to the Russian

Empire. Ukrainians and Russians resettled Tatar

homes and villages.

CRIMEAN TATARS

341

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Many Tatars fled to Turkey, where they joined

descendants of Tatars who had emigrated from

Crimea in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In the early 2000s it was estimated that there were

more than 5 million Crimean Tatar descendants

who were citizens of the Republic of Turkey. They

have been thoroughly assimilated as Turks, though

they continue Tatar cultural and literary activities.

During the next thirty-five years, Tatars in

Central Asian exile continued to maintain their na-

tional identity, through cultural and political

means. They published, in Tatar, a newspaper in

Tashkent, Lenin Bayragï, and united their efforts

with various Soviet dissident groups. Some at-

tempted to return to the Crimean peninsula, with

modest success.

With the collapse of the USSR, and the new in-

dependence of the Ukraine, continued efforts have

been made by Tatars to reestablish some of their

communities on the peninsula. Crimean Tatars,

however, remain one of the many “nationalities”

of the former USSR that have not been able to es-

tablish a new nation.

See also: DEPORTATIONS; GASPIRALI, ISMAIL BEY; ISLAM;

NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allworth, Edward A., ed. (1998). The Tatars of Crimea :

Return to the Homeland: Studies and Documents.

Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Fisher, Alan. (1978). Crimean Tatars. Stanford, CA:

Hoover Institution Press.

Fisher, Alan. (1998). Between Russians, Ottomans and

Turks: Crimea and Crimean Tatars. Istanbul: Isis Press.

A

LAN

F

ISHER

CRIMEAN TATARS

342

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Crimean Tatars mark the fifty-fourth anniversary of Stalin’s order to deport their ancestors from the Crimean peninsula, May 18,

1998. P

HOTOGRAPH BY

S

ERGEI

S

VETLITSKY

/A

SSOCIATED

P

RESS

. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.