Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CRIMEAN WAR

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was Europe’s great-

est war between 1815 and 1914, pitting first Tur-

key, then France and England, and finally

Piedmont–Sardinia against Russia.

The incautious and miscalculated decision by

Nicholas I to activate his southern army corps and

Black Sea fleet in late December 1852 can be at-

tributed to several general misperceptions: the of-

ficial myth that Russia legally protected the

Ottoman Orthodox; disinformative claims of Ot-

toman perfidy regarding the Orthodox–Catholic

dispute over Christian Holy Places; and illusions of

Austrian loyalty and British friendship. Attempts

to interest the British in a partition of the Ottoman

Empire failed. Britain followed France in sending a

fleet to the Aegean to back Turkey, after Russia’s

extraordinary ambassador to Istanbul, Alexander

Menshikov, acted peremptorily, following the

tsar’s instructions, in March 1852. Blaming Turk-

ish obstinacy on the British ambassador Stratford

de Redcliffe, the Russians refused to accept the Ot-

toman compromise proposal on the Holy Places on

the grounds that it skirted the protection issue.

Russia broke relations with Turkey in May and oc-

cupied Moldavia and Wallachia in July.

While the Ottomans mobilized, European states-

men sought an exit. Russia’s outright rejection in

September of another Ottoman compromise fi-

nessing the protection issue, one which the British

found reasonable, emboldened the Turks to declare

war and attack Russian positions in Wallachia and

the eastern Black Sea (October). Admiral Pavel

CRIMEAN WAR

343

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

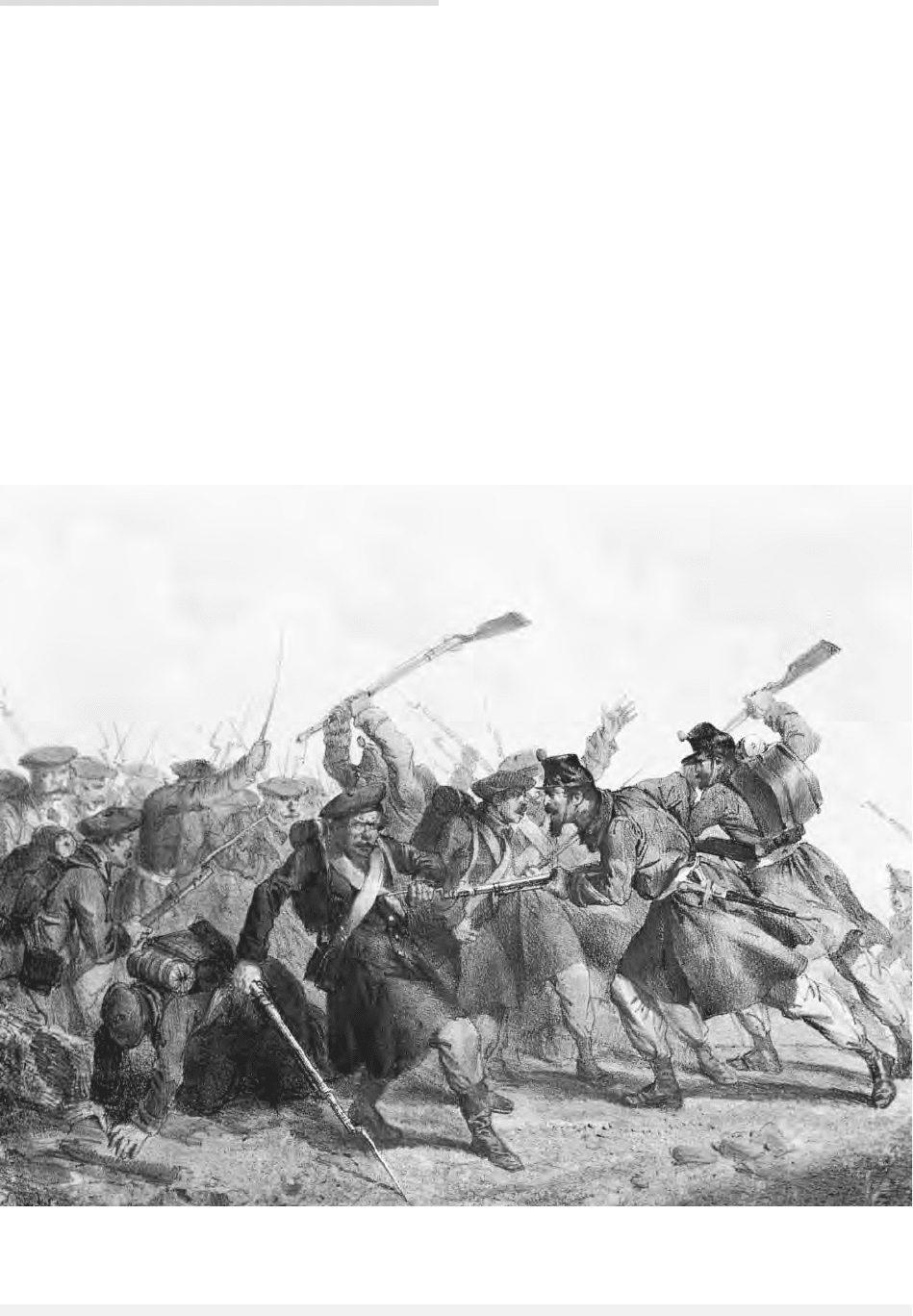

Encounter between Russians, nineteenth-century engraving. T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/M

USEO DEL

R

ISORGIMENTO

R

OME

/D

AGLI

O

RTI

Nakhimov’s Black Sea squadron destroyed a Turk-

ish supply convoy off Sinope (November 30), and

the combined Anglo–French–Turkish fleet entered

the Black Sea on January 1, 1854. Russia refused

the humiliating allied demand to keep to port, and

by early April, Britain and France were at war with

Russia.

Russia’s million–man army was larger than

that of the allies, but had fewer rifles and deployed

600,000 troops from Finland to Bessarabia as in-

surance against attacks from the west. Anglo–

French fleets and logistics far outclassed Russia’s.

The war operated on several fronts. The Rus-

sians crossed the Danube in March and besieged

Silistra, only to retreat and evacuate Wallachia and

Moldavia in June in the face of Austro–German

threats. Anglo–French naval squadrons entered the

Baltic and destroyed Russia’s fortifications at Bo-

marsund and Sveaborg, but did not harm Kron-

stadt. In Transcaucasia, Russian counterattacks and

superior tactics led to advances into Eastern Ana-

tolia and the eventual investment of Kars in Sep-

tember 1855.

The key theater was Crimea, where the capture

of Sevastopol was the chief Allied goal. Both sides

made mistakes. The Russians could have mounted

a more energetic defense against Allied landings,

while the Allies might have taken Sevastopol be-

fore the Russians fortified their defenses with

sunken ships and naval ordnance under Admiral

Vladimir Kornilov and army engineer Adjutant Ed-

uard Totleben. The Allies landed at Evpatoria, de-

feated the Russians at the Alma River (September

20, 1854), and redeployed south of Sevastopol. The

Russian attempt to drive the Allies from Balaklava

failed even before the British Light Brigade made its

celebrated, ill–fated charge (October 25, 1854). The

well–outnumbered allies then tried to besiege Sev-

astopol and thus exposed themselves to a counter-

attack at Inkerman on November 5, 1854, which

the Russians completely mishandled with their out-

moded tactics, negligible staff work, and command

rivalries.

Despite a terrible winter, the Allies reinforced

and renewed their siege in February 1855. Allied

reoccupation of Evpatoria, where the Turks held off

a Russian counterattack, and a summer descent on

Kerch disrupted the flow of Russian supplies. The

death of Nicholas I and accession of Alexander II

(March 2) meant little at first. As per imperial

wishes, the Russians mounted a hopeless attack on

the besiegers’ positions on the Chernaya River (Au-

gust 16). The constant Allied bombardment and

French-led assaults on Sevastopol’s outer defenses

led to an orderly evacuation (September 8–9). The

Russians in turn captured Kars in Eastern Anatolia

(November 26), thereby gaining a bargaining chip.

Hostilities soon abated.

Russia lost the war in the Baltic, Crimea, and

lower Danube, with the demilitarization of the

Åland Islands and the Black Sea and retrocession of

southern Bessarabia, but, at the cost of 400,000-

500,000 casualties, defended the empire’s integrity

from maximal Anglo–Ottoman rollback goals and

won the war in the Caucasus and Transcaucasia.

The evidence of Russia’s technological and struc-

tural inferiority to the West, as well as the massive

turnout of peasant serfs expecting emancipation in

return for volunteer service, were major catalysts

of the Great Reforms under Alexander II. Russia be-

came more like the other great powers, adhering to

the demands of cynical self-interest.

See also: GREAT BRITAIN, RELATIONS WITH; MILITARY, IM-

PERIAL ERA; NESSELRODE, KARL ROBERT; SEVASTOPOL;

TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baumgart, Winfried. (1999). The Crimean War, 1853-

1856. London: Arnold.

Goldfrank, David. (1994). The Origins of the Crimean War.

London: Longman.

D

AVID

M. G

OLDFRANK

CRONY CAPITALISM

Crony capitalism is a term that describes an eco-

nomic system where people with good connections

to the center of power—the “cronies” of the gov-

ernment—manage to place themselves in positions

of undue influence over economic policy, thus de-

riving great personal gains.

In the case of Russia, the term implies that be-

tween the president and the country’s business

leaders—known as the “oligarchs”—there emerged

a tacit understanding. If the oligarchs used their

economic power to supply political and financial

support for the president, in return they would be

allowed to influence for their own benefit the for-

mulation of laws and restrictions on a range of im-

portant matters.

CRONY CAPITALISM

344

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A prominent example is that of insider dealings

in the process of privatization, which, for exam-

ple, allowed the transfer of major oil companies

into private hands at extremely low prices. Another

is the introduction of a system of “authorized

banks,” whereby a few select commercial banks

were allowed to handle the government’s accounts.

Such rights could be abused: for example, by de-

laying the processing of payments received. Under

conditions of high inflation, the real value eventu-

ally passed on to the final destination would be

greatly diminished. There have also been serious al-

legations of insider dealings by the cronies in Russ-

ian government securities.

The overall consequences for the Russian econ-

omy were negative in the extreme. The influence

of the so-called crony capitalists over the process

of privatization led to such a warped system of

property rights that some analysts seriously ar-

gued in favor of selective renationalization, to be

followed by a second round of “honest” privatiza-

tion.

Even more important, by allowing the crony

capitalists to take over the oil industry for a pit-

tance, the Russian government freely gave up the

right to extract rent from the country’s natural re-

source base. This represented a massive shift of

future income streams out of the government’s

coffers and into private pockets, with severe impli-

cations for the future ability of the state to main-

tain the provision of public goods.

See also: ECONOMY, POST-SOVIET; MAFIA CAPITALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hedlund, Stefan. (1999). Russia’s “Market” Economy. Lon-

don: UCL Press.

S

TEFAN

H

EDLUND

CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS

The Cuban Missile Crisis was one of the most se-

rious incidents of the Cold War. Many believed that

war might break out between the United States and

the Soviet Union over the latter’s basing of nuclear-

armed missiles in Cuba.

Fidel Castro came to power in Cuba promising

to restore the liberal 1940 constitution but imme-

diately took more radical steps, including an eco-

nomic agreement in 1960 with the Soviet Union.

In turn, the Soviet premier, Nikita Khrushchev,

promised in June to defend Cuba with Soviet nu-

clear arms. In early 1961, the United States broke

relations with Havana, and in April it helped thou-

sands of Cuban exiles stage an abortive uprising at

the Bay of Pigs.

Khrushchev was convinced that the United

States would strike again, this time with American

soldiers; and he believed that Castro’s defeat would

be a fatal blow to his own leadership. He decided

that basing Soviet missiles in Cuba would deter the

United States from a strike against the Castro

regime. Moreover, so he reasoned, the Cuba-based

medium-range missiles would compensate for the

USSR’s marked inferiority to America’s ICBM ca-

pabilities. Finally, a successful showdown with

Washington might improve Moscow’s deteriorat-

ing relations with China.

In April 1962, Khrushchev raised the possibil-

ity of basing Soviet missiles in Cuba with his de-

fense minister, Rodion Malinovsky. He hoped to

deploy the missiles by October and then inform

Kennedy after the congressional elections in No-

vember. He apparently expected the Americans to

accept the deployment of the Soviet missiles as

calmly as the Kremlin had accepted the basing of

U.S. missiles in Turkey. Foreign minister Andrei

Gromyko, when finally consulted, flatly told

Khrushchev that Soviet missiles in Cuba would

“cause a political explosion” (Taubman) in the

United States, but the premier was unmoved. In

late April, a Soviet delegation met with Khrushchev

before departing for Cuba. They were told to “ex-

plain the plan” to install missiles “to Castro”

(Taubman). In fact, their mission was more one of

“telling than asking.” Castro was hardly enthusi-

astic, but was ready to yield to a policy that would

strengthen the “entire socialist camp” (Taubman).

Later the Presidium voted unanimously to approve

the move.

Perhaps most remarkably, Khrushchev believed

that the deployment of sixty missiles with forty

launchers, not to mention the support personnel

and equipment, could be done secretly. General

Anatoly Gribkov warned that the installation

process in Cuba could not be concealed. And Amer-

ican U-2 spy planes flew over the sites unhindered.

The Cubans, too, doubted that the plan could be

kept secret; Khrushchev responded that if the

weapons were discovered the United States would

not overreact, but if trouble arose, the Soviets

would “send the Baltic Fleet.”

CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS

345

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

In July 1962, the American government learned

that the USSR had started missile deliveries to Cuba.

By the end of August, American intelligence re-

ported that Soviet technicians were in Cuba, su-

pervising new military construction. In September,

Kennedy warned that if any Soviet ground-to-

ground missiles were deployed in Cuba, “the gravest

issues would arise.” Rather than calling a halt to

the operation, Khrushchev ordered it accelerated,

while repeatedly assuring Washington that no

build-up was taking place.

On October 14, U.S. aerial reconnaissance dis-

covered a medium-range ballistic missile mounted

on a launching site. Such a missile could hit the

eastern United States in a matter of minutes. On

October 16, Kennedy and his closest advisers met

to discuss the crisis and immediately agreed that

the missile must be removed. On October 22,

Kennedy announced a “quarantine” around Cuba,

much to Khrushchev’s delight. The premier thought

the word sufficiently vague to allow for negotia-

tion and exulted, “We’ve saved Cuba!” Despite his

apparent satisfaction, Khrushchev fired off a letter

to Kennedy accusing him of interfering in Cuban

affairs and threatening world peace. He then went

to the opera.

The turning point came on October 24, when

Attorney General Robert Kennedy told the Soviet

ambassador that the United States would stop the

Soviet ships, strongly implying that it would do so

even if it meant war. Khrushchev reacted angrily,

but a letter from President Kennedy on October 25

pushed the premier toward compromise. Kennedy

wrote that he regretted the deterioration in rela-

tions and hoped Khrushchev would take steps to

restore the “earlier situation.” With this letter,

Khrushchev finally realized that the crisis was not

worth the gamble and began to back down. An-

other war scare occurred on the twenty-seventh

with the downing of a U-2 over Cuba, but by this

CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS

346

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

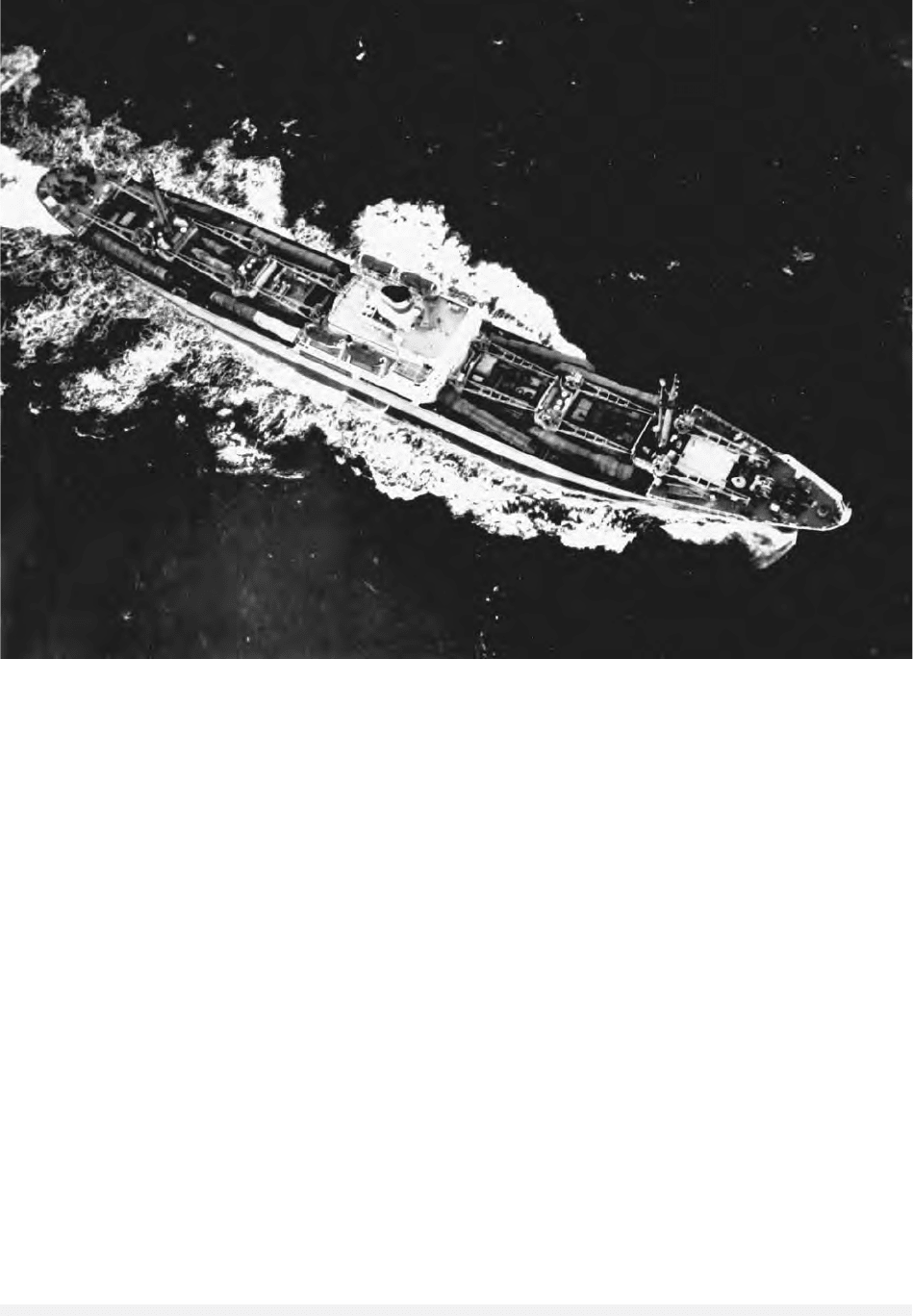

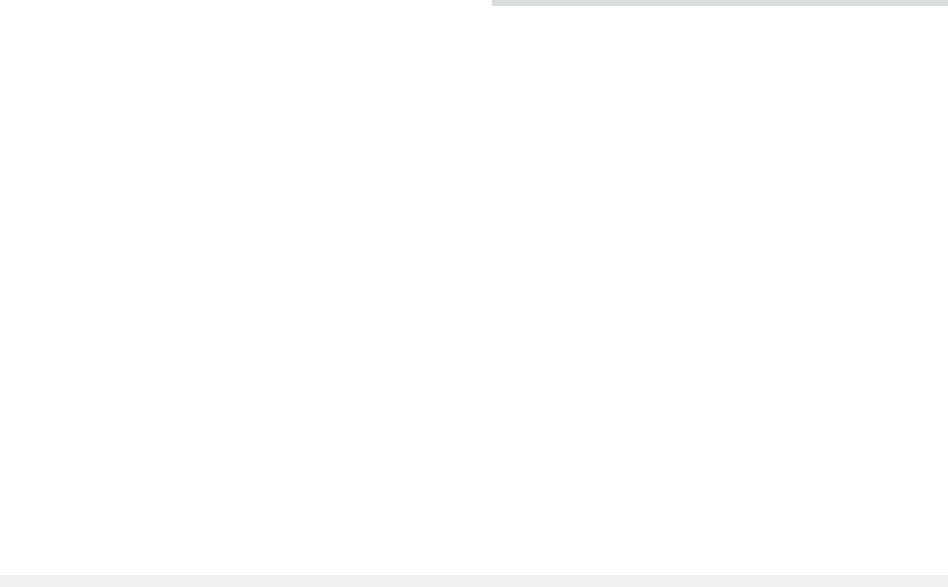

A U.S. reconnaissance photo reveals a Soviet cargo ship with eight missile transporters and canvas-covered missiles lashed on deck

during its return voyage from Cuba to the Soviet Union. © H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

point both leaders were ready and even anxious to

end the crisis. On October 29, the premier informed

Kennedy that the missiles and offensive weapons in

Cuba would be removed. Kennedy promised there

would be no invasion and secretly agreed to remove

America’s Jupiter missiles from Turkey.

Khrushchev’s Cuban gamble helped convince

the Soviet leadership that he was unfit to lead the

USSR. This humiliation, combined with failures in

domestic policies, cost him his job in 1964.

See also: COLD WAR; CUBA, RELATIONS WITH; KHRUSH-

CHEV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH; UNITED STATES, RELA-

TIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fursenko, Aleksander, and Naftali, Timothy. (1997).

“One Hell of a Gamble”: Khrushchev, Castro and

Kennedy, 1958–1964. New York: Norton.

Nathan, James A. (2001). Anatomy of the Cuban Missile

Crisis. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Taubman, William. (2003). Khrushchev: The Man and His

Era. New York: Norton.

Thomson, William. (1995). Khrushchev: A Political Life.

Oxford, UK: Macmillan.

H

UGH

P

HILLIPS

CUBA, RELATIONS WITH

The Cuban Communist Party began its frequently

interrupted existence in 1925. Classically aligned

with Moscow, the Cuban communists were among

the most active communist parties in Latin Amer-

ica, placing one of their members in the President

Batista’s cabinet during World War II. The Soviet

Union had diplomatic relations with Cuba during

the war and for a few years afterward, and re-

opened them in 1960.

In the mid-1950s Fidel Castro, the leader of a

radical nationalist revolutionary movement, orga-

nized an armed revolt against Batista’s increasingly

dictatorial rule. Castro was not a member of the

Communist Party; the communists provided little

or no support to his movement and openly criti-

cized his tactics and strategies. After Castro seized

power in 1959, communists, with a few excep-

tions, did not staff his new government and fell

into obscurity.

In 1960 President Eisenhower concluded that

Castro threatened U.S. private and public interests

and was not amenable to U.S. direction. Castro was

seizing American-owned properties and moving to-

ward one-man rule. In order to protect U.S. pub-

lic and private interests and to reassert traditional

bilateral relationships, the U.S. government em-

bargoed sugar, Cuba’s main export, cut off access

to oil, and continued an embargo of arms and mu-

nitions begun against Batista. These measures, un-

opposed, would have terminated Castro’s rule.

U.S. actions had unexpected results. The USSR

seized this chance to establish a toehold in Cuba.

Countering U.S. sanctions, the USSR bought Cuba’s

sugar, sold its oil, and provided arms. U.S. efforts

to overthrow Castro at the Bay of Pigs failed, and

Cuba’s ties with the USSR were strengthened. Cas-

tro, his party, and the Cuban state adopted com-

munist models.

The resolve of the three governments in the

new triangular relationship was tested in the Cuban

Missile Crisis of October 1963. Emboldened by his

toehold near Florida and reassured by Castro’s anti-

Americanism and revolutionary intentions, Khru-

shchev ordered Soviet missiles to Cuba. President

Kennedy, risking war, ordered the Navy to block

missile deliveries. In subsequent negotiations Khru-

shchev agreed to remove the missiles, and Kennedy

agreed not to use force against Cuba.

The Cuban Missile Crisis settlement set the

framework for the relationships between the three

countries. Castro became even more dependent on

Soviet largess, as he was deprived of political and

economic ties with the United States, previously

Cuba’s most important economic partner. The

United States continued its anti-Castro campaigns

short of invasion. The USSR replaced the United

States as the hegemonic power over Cuba with all

the advantages, costs, and risks involved.

Castro’s dependence on the Soviet Union for

trade, military equipment, and foreign aid grew

steadily over the years. In return for Soviet aid,

Castro copied the ideology, political structure, and

economic system of the USSR. In 1976 the consti-

tution formalized a communist structure in Cuba

that harmonized with communist structures else-

where, with party control of agriculture, industry,

and commerce. Cuba’s ties with the USSR facili-

tated Castro’s iron one-man rule for more than

thirty years. Castro reciprocated ongoing Soviet as-

sistance through his support of pro-Soviet revolu-

tionary movements in Latin America, including

CUBA, RELATIONS WITH

347

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Nicaragua and El Salvador, and elsewhere, includ-

ing Angola and Ethiopia. These movements sup-

ported the USSR and copied Soviet models.

The Soviet Union’s ties with Cuba had global

implications. Soviet armed forces had access to the

Western Hemisphere, and Cuba could serve as a

point of contact for regional revolutionary move-

ments. This alliance, taken together with Commu-

nist governments in Eastern Europe and Asia,

provided Moscow with an arguable claim to world-

wide influence. Moscow also took satisfaction in

having a presence in Cuba matching that of the

U.S. in Berlin.

Castro proved independent and unruly, not an

ideal client by Soviet standards. The leaders of other

Communist parties in the hemisphere were under

Soviet control through the Foreign Department of

the Soviet Communist Party. Unlike most other

Communist leaders, Castro manipulated Moscow

as much as or more than Moscow manipulated

him.

The Soviet Union’s ties with Cuba proved very

costly over the years. The USSR paid high prices

for Cuban sugar, and Cuba paid low prices for So-

viet oil. Moscow equipped Cuba with one of the

strongest military forces in Latin America. Foreign

economic assistance probably far exceeded $70 bil-

lion during the relationship. Cuba became the So-

viet Union’s largest debtor along with Vietnam.

The Soviet leadership kept these huge expenditures

secret until the USSR began to collapse.

Soviet economic and military investments in

Cuba, including the establishment of a military

brigade near Havana, were both a strategic advan-

tage and a vulnerability, the latter because of the

preponderance of U.S. power in the region. Soviet

leaders were careful to make clear that they did not

guarantee Cuba against a US attack. Nor was Cuba

admitted to the Warsaw Pact. In that military sense

their relationship was more a partnership than an

alliance. After the Nicaraguan revolution of 1979,

Moscow was even more careful, learning from

lessons in Cuba, not to guarantee the Sandinistas

economic viability or military security.

General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev’s com-

mitment to glasnost led to public knowledge in

Russia of the costly nature of Soviet subsidies to

Cuba; perestroika led to a reexamination of the

Cuban regime and its relationship to Soviet inter-

ests. In his efforts to put the USSR on a more solid

footing, particularly with respect to Germany, Gor-

bachev sought support from the United States. For

their part, President George Bush and Secretary of

State James Baker sought Gorbachev’s collabora-

tion in ending the Cold War in Latin America. In

response to U.S. pressure among other factors,

Gorbachev withdrew the Soviet military brigade

from Cuba and ended lavish economic aid to Cuba.

His actions led to the termination of Soviet and

Cuban involvement in revolutionary movements in

Central America. To Moscow’s advantage, and to

the huge impoverishment of Cuba, the Soviet

Union and Cuba were set free of their mutual en-

tanglements.

See also: COLD WAR; CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS; KHRUSHCHEV,

NIKITA SERGEYEVICH; UNITED STATES, RELATIONS

WITH.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blasier, Cole. (1989). The Giant’s Rival: The USSR and Latin

America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Mesa-Lago, Carmelo, ed. (1993). Cuba after the Cold War.

Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Pavlov, Yuri. (1994). Soviet Cuban Alliance, 1959–1991.

Miami: University of Miami North South Center.

Smith, Wayne S., ed. (1992). The Russians Aren’t Coming:

New Soviet Policy in Latin America. Boulder, CO:

Lynne Rienner.

C

OLE

B

LASIER

CULT OF PERSONALITY

At the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party

in 1956, Nikita Khrushchev denounced Josef

Stalin’s “Cult of Personality” in the so-called “Se-

cret Speech.” He declared, “It is impermissible and

foreign to the spirit of Marxism-Leninism to ele-

vate one person, to transform him into a super-

man possessing supernatural characteristics akin to

those of a god.” In addition to enumerating Stalin’s

repression of the Communist Party during the

purges, Khrushchev recounted how in films, liter-

ature, his Short Biography, and the Short Course of

the History of the Communist Party, Stalin displaced

Vladimir Lenin, the Party, and the people and

claimed responsibility for all of the successes of the

Revolution, the civil war, and World War II.

Khrushchev’s speech praised Lenin as a modest “ge-

nius,” and demanded that “history, literature and

the fine arts properly reflect Lenin’s role and the

great deeds of our Communist Party and of the

CULT OF PERSONALITY

348

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Soviet people.” Khrushchev’s formulation reveals

the paradox of the “cult of personality.” While den-

igrating the cult of Stalin, Khrushchev reinvigo-

rated the cult of Lenin.

Analysts have traced the leader cult back to the

earliest days of the Soviet Union, when a person-

ality cult spontaneously grew up around Lenin.

The cult grew among Bolsheviks because of Lenin’s

stature as Party leader and among the population

due to Russian traditions of the personification of

political power in the tsar (Tucker, 1973, pp.

59–60). Lenin himself was appalled by the tendency

to turn him into a mythic hero and fought against

it. After the leader’s death in 1924, however, ven-

eration of Lenin became an integral part of the

Communist Party’s quest for legitimacy. Party

leaders drew on both political and religious tradi-

tions in their decision to place a mausoleum con-

taining the embalmed body of Lenin at the

geographic and political center of Soviet power in

Moscow’s Red Square. Once Lenin was enshrined

as a sacred figure, his potential successors scram-

bled to position themselves as his true heirs.

After Stalin consolidated his power and em-

barked on the drive for socialist construction, he

began to build his own cult of personality. Stalin’s

efforts were facilitated by the previously existing

leader cult, and he trumpeted his special relation-

ship with Lenin. Early evidence of the Stalin cult

can be found in the press coverage of his fiftieth

birthday in 1929, which extolled “the beloved

leader, the truest pupil and comrade-in-arms of

Vladimir Ilich Lenin” (Brooks, 2000, p. 61). In the

early 1930s, Stalin shaped his image as leader by

establishing himself as the ultimate expert in fields

other than politics. He became “the premier living

Marxist philosopher” and an authoritative historian

of the Party (Tucker, 1992, pp. 150–151). Stalin

shamelessly rewrote Party history to make himself

Lenin’s chief assistant and adviser in 1917. Soviet

public culture of the 1930s and 1940s attributed all

of the achievements of the Soviet state to Stalin di-

rectly and lauded his military genius in crafting vic-

tory in World War II. Stalin’s brutal repressions

went hand in hand with a near-deification of his

person. The outpouring of grief at his death in 1953

revealed the power of Stalin’s image as wise father

and leader of the people.

Once he had consolidated power, Nikita

Khrushchev focused on destroying Stalin’s cult.

Many consider Khrushchev’s 1956 attack on the

Stalin cult to be his finest political moment. Al-

though Khrushchev criticized Stalin, he reaffirmed

the institution of the leader cult by invoking Lenin

and promoting his own achievements. Khrush-

chev’s condemnation of the Stalin cult was also

limited by his desire to preserve the legitimacy of

the socialist construction that Stalin had under-

taken. After Khrushchev’s fall, Leonid Brezhnev

criticized Khrushchev’s personal style of leadership

but ceased the assault on Stalin’s cult of personal-

ity. He then employed the institution of the leader

cult to enhance his own legitimacy.

Like Stalin’s cult, Brezhnev’s cult emphasized

“the link with Lenin, [his] . . . role in the achieve-

ment of successes . . . and his relationship with the

people” (Gill). The Brezhnev-era party also perpet-

uated the Lenin cult and emphasized its own links

to Lenin by organizing a lavish commemoration of

the centennial of Lenin’s birth in 1970. The asso-

ciation of Soviet achievements with Brezhnev paled

in comparison to the Stalin cult and praise of Brezh-

nev’s accomplishments often linked them to the

Communist Party as well. Both Khrushchev and

Brezhnev sought to raise the status of the Com-

munist Party in relation to its leader. Yet Stalin,

Khrushchev, and Brezhnev all conceived of the role

of the people as consistently subordinate to leader

and Party.

It was not until Gorbachev instituted the pol-

icy of glasnost, or openness, in the mid-1980s that

the institution of the cult of personality came un-

der sustained attack. The Soviet press revealed

Stalin’s crimes and then began to scrutinize the

actions of all of the Soviet leaders, eventually in-

cluding Lenin. The press under Gorbachev effec-

tively demolished the institution of the Soviet leader

cult by revealing the grotesque falsifications re-

quired to perpetuate it and the violent repression

of the population hidden behind its facade. These

attacks on the cult of personality undermined the

legitimacy of the Soviet Union and contributed to

its downfall.

In the post-Soviet period, analysts have begun

to see signs of a cult of personality growing around

Vladimir Putin. Other observers, however, are

skeptical of how successful such a leader cult could

be in the absence of a Party structure to promote

it and given the broad access to information that

contemporary Russians enjoy. The cult of person-

ality played a critical role in the development of the

Soviet state and in its dissolution. The discrediting

of the cult of the leader as an institution in the late

Soviet period makes its post-Soviet future uncer-

tain at best.

CULT OF PERSONALITY

349

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

See also: KHRUSHCHEV, NIKITA SERGEYEVICH; LENIN’S

TOMB; LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; PUTIN, VLADIMIR

VLADIMIROVICH; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brooks, Jeffrey. (2000). Thank You, Comrade Stalin!

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gill, Graeme. (1980). “The Soviet Leader Cult: Reflections

on the Structure of Leadership in the Soviet Union.”

British Journal of Political Science 10(2):167–186.

“How Likely Is a Putin Cult of Personality?” (2001).

[Panel Discussion] Current Digest of the Post-Soviet

Press 53(21):4–6.

Khrushchev, Nikita. (1956). “On the Cult of Personality

and Its Harmful Consequences” Congressional Pro-

ceedings and Debates of the 84th Congress, 2nd Session

(May 22–June 11), C11, Part 7 (June 4), pp.

9,389–9,403.

Tucker, Robert C. (1973). Stalin as Revolutionary,

1879–1929. New York: Norton.

Tucker, Robert C. (1992). Stalin in Power: The Revolution

from Above, 1928–1941. New York: Norton.

Tumarkin, Nina. (1983). Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in

Russia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

K

AREN

P

ETRONE

CULTURAL REVOLUTION

“Cultural revolution” (kulturnaya revolyutsiya) was

a concept used by Lenin in his late writings (e.g.,

his 1923 article “On Cooperation”) to refer to gen-

eral cultural development of the country under so-

cialism, with emphasis on such matters as

inculcation of literacy and hygiene, implying grad-

ual transformation out of the backwardness that

Lenin saw as the legacy of tsarism.

In the late 1920s, the term was taken up and

transformed by young communist cultural mili-

tants who sought the party leaders’ approval for

an assault on “bourgeois hegemony” in culture;

that is, on the cultural establishment, including

Anatoly Lunacharsky and other leaders of the Peo-

ple’s Commissariat of Enlightenment, and the val-

ues of the old Russian intelligentsia. For the

militants, the essence of cultural revolution was

“class war”—an assault against the “bourgeois” in-

telligentsia in the name of the proletariat—and they

meant the “revolution” part of the term literally.

In the years 1928 through 1931, the militants suc-

ceeded in gaining the party leaders’ support, but

lost it again in 1932 when the Central Committee

dissolved the main militant organization, the Rus-

sian Association of Proletarian Writers (RAPP), and

promoted reconciliation with the intelligentsia.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, the concept of cul-

tural revolution received a new lease of life in the

Soviet Union. The inspiration came from Lenin’s

writings, not from the militant episode of 1928

through 1931, which was largely forgotten or sup-

pressed as discreditable. Cultural revolution was

now seen as a unique process associated with so-

cialist revolution, which, for the first time, made

culture the property of the whole people. The em-

phasis was on the civilizing mission of Soviet

power, particularly in the country’s own “back-

ward,” non-Slavic republics and regions. Rebutting

suggestions from East European scholars that cul-

tural revolution was not a necessary step in the

evolution of countries that were not backward

when they came to socialism, Soviet writers such

as Maxim Kim described cultural revolution as one

of the general laws (zakonomernosti) of socialism

first realized in the Soviet Union but applicable to

all nations.

In Western Soviet historiography since the late

1970s, the term has often connoted the militant

episode of the Cultural Revolution (in some respects

foreshadowing the Chinese Cultural Revolution of

the 1960s) described in the 1978 volume edited by

Sheila Fitzpatrick. It has also been used in a sense

different from any of the above to describe a Bol-

shevik (or, more broadly, Russian revolutionary)

transformationist mentality endemic in the first

quarter of the twentieth century (Joravsky; Clark;

David-Fox).

Along with collectivization and the First Five-

Year Plan, the Cultural Revolution was one of the

great upheavals of the late 1920s and 1930s some-

times known as the “Great Break” (veliky perelom)

or Stalin’s “revolution from above.” There were

two important differences between the Cultural

Revolution and other “Great Break” policies, how-

ever. The first was that whereas the turn to col-

lectivization, elimination of kulaks, and forced-pace

industrialization proved to be permanent, the Cul-

tural Revolution was relatively short-lived. The sec-

ond was that, in contrast to the collectivization and

industrialization drives, Stalin’s personal involve-

ment and commitment was limited to a few areas,

notably the show trials of “wrecker” engineers and

the formation of a new proletarian intelligentsia

through worker promotion (vydvizhenie), and he

CULTURAL REVOLUTION

350

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

was doubtful of or positively hostile to a number

of the militants’ initiatives (e.g., in educational pol-

icy, literature, and architecture) when they came

to his attention. The fact that the Cultural Revolu-

tion was followed by what Nicholas S. Timasheff

called a “Great Retreat” in cultural and social pol-

icy in the mid-1930s strongly suggests that Stalin,

like Lenin before him, lacked enthusiasm for the

utopianism and iconoclasm that inspired many of

the young cultural militants.

The most influential of the militant organiza-

tions in culture, RAPP, had been agitating since the

mid-1920s for an abandonment of the relatively

tolerant and pluralist cultural policies associated

with Lunacharsky and his People’s Commissariat

of Enlightenment, and the establishment of un-

compromising “proletarian” (which, in the arts, of-

ten meant communist-militant) rule in literature.

RAPP’s pretensions were rebuffed in 1925, but in

1928 the atmosphere in the party leadership

abruptly changed with the staging of the Shakhty

trial, in which “bourgeois” engineers—serving as a

synecdoche for the noncommunist Russian intelli-

gentsia as a whole—were accused of sabotage and

conspiracy with foreign powers. At the same time,

Stalin launched a campaign for intensified recruit-

ment and promotion of workers and young com-

munists to higher education, especially engineering

schools, and administrative positions, with the pur-

pose of creating a “worker-peasant intelligentsia”

to replace the old bourgeois one. The obverse of this

policy was purging of “socially undesirable” stu-

dents and employees from schools, universities, and

government departments.

Stalin used the drive against the bourgeois in-

telligentsia to discredit political opponents, whom

he took pains to link with noncommunist intellec-

tuals accused of treason in the series of show tri-

als that began in 1928. “Rightists” like Nikolai

Bukharin and Alexei Rykov, who opposed Stalin’s

maximalist plans for forcible collectivization and

forced-pace industrialization, became targets of a

smear campaign that linked them with the class

enemy, implying that they were sympathetic to,

perhaps even in league with, kulaks as well as

“wreckers” from the bourgeois intelligentsia.

As an “unleashing” of militants in all fields of

culture and scholarship, as well as in the commu-

nist youth movement (the Komsomol), the Cul-

tural Revolution generated a host of spontaneous

as well as centrally directed radical initiatives. As

occurred later in the Chinese Cultural Revolution,

young radicals from the Komsomol launched raids

on “bureaucracy” that severely disrupted the work

of government institutions. Endemic purging of all

kinds of institutions, from schools and hospitals to

local government departments, often initiated by

local activists without explicit instructions from

the center, was equally disruptive.

Among the main loci of Cultural Revolution ac-

tivism, along with RAPP, were the Communist

Academy and the Institute of Red Professors, schol-

arly institutions whose specific purpose was to

train and advance a communist intelligentsia. Al-

though Stalin had contact with some of these ac-

tivists, and perhaps even toyed with the idea of

establishing his own “school” of young commu-

nist intellectuals, he was also suspicious of them

as a group because of their involvement in party

infighting and their admiration for the party’s two

most renowned intellectuals and theorists, Trotsky

and Bukharin. The young communist professors

and graduate students did their best to shake up

their disciplines, which were almost exclusively in

the humanities and social sciences rather than the

natural sciences, and to challenge their “bourgeois”

teachers. In the social sciences, this challenge was

usually mounted in the name of Marxism, but in

remote areas such as music theory the challenge

might come from an outsider group whose ideas

had no Marxist underpinning.

Long-standing disagreements over theory and

research took on new urgency, and many vision-

ary schemes that challenged accepted ideas found

institutional support for the first time. In architec-

ture, utopian planning flourished. Legal theorists

speculated about the imminent dissolution of law,

while a similar movement in education for the dis-

solution of the school did considerable practical

damage to the school system. Under the impact of

the Cultural Revolution, Russian cultural officials

dealing with the reindeer-herding small peoples of

the north switched to an interventionist policy of

active transformation of the native culture and

lifestyle. In ecology, the Cultural Revolution ex-

posed conservationists to attack by militants in-

spired by the ideology of transforming nature.

In 1931 and 1932, official support for class-

war Cultural Revolution came to an end. Profes-

sional institutions were in shambles, and little work

was being produced. In industry, with so many

workers being promoted and sent to university,

there was a shortage of skilled workers left in the

factories. In June 1931 Stalin officially rehabilitated

CULTURAL REVOLUTION

351

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the bourgeois engineers; in April 1932, RAPP and

other proletarian cultural organizations were dis-

solved. Many of the radicals who had been instru-

mental in attacking established authority during

the Cultural Revolution were accused of deviation

and removed from positions of influence. Bourgeois

specialists who had been fired or arrested were al-

lowed to return to work. In education, radical the-

ories were repudiated and traditional norms

reestablished, and policies of aggressive proletarian

recruitment were quietly dropped.

But although this was the end of the radical

antibourgeois Cultural Revolution, it was hardly a

return to the way things had been before. Acade-

mic freedom had been seriously curtailed, and party

control over cultural and scholarly institutions

tightened. Thousands of young workers, peasants,

and communists (vydvizhentsy) had been sent to

higher education or promoted into administrative

jobs. During the Great Purges of 1937–1938, many

activists of the Cultural Revolution perished (often

denounced by resentful colleagues), though others

survived in influential positions in cultural and aca-

demic administration. But the cohort of vyd-

vizhentsy, particularly those trained in engineering

who graduated in the first half of the 1930s, were

prime, albeit unwitting, beneficiaries of the Great

Purges. Members of this cohort, sometimes known

as “the Brezhnev generation,” entered top party,

government, and professional positions at the end

of the 1930s and continued to dominate the polit-

ical elite for close to half a century.

See also: COLLECTIVIZATION; CONSTRUCTIVISM; FELLOW

TRAVELERS; INDUSTRIALIZATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clark, Katerina. (1995). Petersburg: Crucible of Cultural

Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

David-Fox, Michael. (1999). “What Is Cultural Revolu-

tion?” Russian Review 58(2):181–201.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1974). “Cultural Revolution in Rus-

sia, 1928–1932.” Journal of Contemporary History

9(1):33–52.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila, ed. (1978). Cultural Revolution in Rus-

sia, 1928–1931. Bloomington: Indiana University

Press.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1999). “Cultural Revolution Revis-

ited.” Russian Review 58(2):202–209.

Gorbunov, V. I. (1969). Lenin on the Cultural Revolution.

Moscow: Novosti.

Joravsky, David. (1985). “Cultural Revolution and the

Fortress Mentality.” In Bolshevik Culture: Experiment

and Order in the Russian Revolution, ed. Abbott Glea-

son; Peter Kenez; and Richard Stites. Bloomington:

Indiana University Press.

Kim, Maksim Pavlovich. (1984). Socialism and Culture.

Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences.

Lewis, Robert. (1986). “Science, Nonscience, and the Cul-

tural Revolution.” Slavic Review 45(2):286–292.

Meisner, Maurice. (1985). “Iconoclasm and Cultural Rev-

olution in China and Russia.” In Bolshevik Culture:

Experiment and Order in the Russian Revolution, ed.

Abbott Gleason; Peter Kenez; and Richard Stites.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Slezkine, Yuri. (1992). “From Savages to Citizens: The

Cultural Revolution in the Soviet Far North,

1928–1938.” Slavic Review 51(1):52–76.

Weiner, Douglas R. (1988). Models of Nature: Ecology,

Conservation, and Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

S

HEILA

F

ITZPATRICK

B

EN

Z

AJICEK

CUMANS See POLOVTSY.

CURRENCY See ALTYN; DENGA; GRIVNA; KOPECK;

MONETARY SYSTEM, SOVIET; RUBLE.

CUSTINE, ASTOLPHE LOUIS LEONOR

(1790–1857), French writer and publicist.

Astolphe de Custine’s fame rests upon his book

Russia in 1839, a voluminous travelogue depicting

the empire of Nicholas I in an unfavorable light; it

became an oft-quoted precursor to numerous sub-

sequent works of professional “Sovietologists” and

“Kremlinologists.” Custine was born into an old

aristocratic family; both his father and grandfather

were executed during the French Revolution. Orig-

inally a staunch political conservative, Custine

traveled to Russia determined to provide French

readers with the positive image of a functioning

monarchy. However, the three months spent in the

empire of Tsar Nicholas I—whom he met in per-

son—turned Custine into a constitutionalist. Rus-

sia’s despotic, incurably corrupt order that entitled

the state to any intrusions into its citizens’ lives

shocked the European observer with its innate vi-

olence and hypocrisy. Custine particularly faulted

CUSTINE, ASTOLPHE LOUIS LEONOR

352

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY