Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the Russian establishment for its quasi-military

structure introduced by Peter I. Most astounding

among his conclusions was the prediction that Rus-

sia would face a revolution of unprecedented scope

within the next half century.

When Russia in 1839 was published in four

lengthy volumes in 1843, it became an immediate

bestseller and was translated into English, German,

and Danish. Russian diplomats and secret agents

tried their utmost to discredit the book and its au-

thor; the tsar himself reportedly had a fit of fury

while reading Custine’s elaborations. On the other

hand, Alexander Herzen and other dissidents

praised Russia in 1839 for its accuracy, and even

the chief of Russia’s Third Department conceded

that the ungrateful French guest merely said out

loud what many Russians secretly were thinking

in the first place.

Astolphe de Custine, who also wrote other

travelogues and fiction, died in 1857.

See also: AUTOCRACY; NICHOLAS I.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Custine, Marquis de. (1989). Empire of the Czar: A Jour-

ney through Eternal Russia. New York: Doubleday.

Grudzinska Gross, Irena. (1991). The Scar of Revolution:

Custine, Tocqueville, and the Romantic Imagination.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

P

ETER

R

OLLBERG

CUSTOMS BOOKS

Customs books (tamozhennye knigi) were official

registers of customs and other revenues collected at

customs offices between the sixteenth and the mid-

eighteenth centuries, and often a source of data on

expenditures by the customs administration.

Typical entries in a customs book list the quan-

tities and values of the commodities carried by a

given merchant. In addition, they usually give the

name, rank, origin, and destination of each mer-

chant. Customs records often include separate sec-

tions on particular “special” commodities, such as

liquor, horses, cattle, grain, or treasury goods.

All Russian towns, as well as many smaller

communities, kept records of all trade passing

through them. A total of some 190 seventeenth-

century customs books have survived to this day.

Although the collection has been repeatedly deci-

mated over time, varying numbers of customs

books still exist for fifty cities in European Russia

and for most of the Siberian fortress towns, virtu-

ally all of them dated between 1626 and 1686. The

best-preserved collections of early modern customs

data are for the Southern Frontier, the Northern

Dvina waterway, and the Siberian fortress towns.

In contrast, practically all the information of the

key commercial centers of Moscow, Yaroslavl’,

Arkhangel’sk, and Novgorod, among others, has

been lost.

For the early eighteenth century, customs data

pertaining to some 300 towns have survived. Dated

from 1714 to 1750, 142 books survive in the col-

lections of the Kamer-kollegia. The most important

collections are for Moscow, Northern Russia, and

the Southern Frontier. The practice of compiling

customs books was discontinued following the

abolition of internal customs points in 1754.

See also: FOREIGN TRADE; MERCHANTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (1999). The Economy and Material Culture

of Russia, 1600–1725. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

J

ARMO

T. K

OTILAINE

CYRIL AND METHODIUS SOCIETY

The first Ukrainian political organization in the

Russian Empire, the Cyril and Methodius Brother-

hood existed from late 1845 to early 1847. A se-

cret society with no clear membership criteria, the

brotherhood consisted of a core group of some

dozen members and a wider circle of an estimated

one hundred sympathizers. The society was led by

the historian Mykola (Nikolai) Kostomarov, the mi-

nor official Mykola Hulak, and the schoolteacher

Vasyl Bilozersky. Scholars continue to disagree as

to whether the great poet Taras Shevchenko, the

most celebrated affiliate of the group, was a formal

member. This organization of young Ukrainian pa-

triots was established in Kiev in December 1845

and, during the fourteen months of its existence,

its activity was limited to political discussions and

the formulation of a program. Kostomarov wrote

the society’s most important programmatic state-

ment, “The Books of the Genesis of the Ukrainian

CYRIL AND METHODIUS SOCIETY

353

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

People.” Strongly influenced by Polish Romanticism

and Pan-Slavism, this document spoke vaguely of

the Christian principles of justice and freedom, but

also proposed a number of radical reforms: the abo-

lition of serfdom, the introduction of universal ed-

ucation, and the creation of a democratic federation

of all the Slavic peoples with the capital in Kiev.

The members of the brotherhood disagreed about

priorities and ways of implementing their program.

Kostomarov, who stressed the Pan-Slavic ideal, ex-

pressed the majority opinion that change could be

achieved through education and moral example.

Hulak and Shevchenko advocated a violent revolu-

tion. Shevchenko, together with the writer Pan-

teleimon Kulish, saw the social and national

liberation of Ukrainians as the society’s priority. In

March 1847 a student informer denounced the so-

ciety to the authorities, leading to the arrest of all

active members. Most of them were subsequently

exiled to the Russian provinces, but Hulak received

a three-year prison term, while Shevchenko’s po-

ems earned him ten years of forced army service

in Central Asia. Soviet historians emphasized the

difference between radicals and liberals within the

brotherhood, while in post-Soviet Ukraine the

group is seen as marking the Ukrainian national

movement’s evolution from the cultural stage to a

political one.

See also: NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST; UKRAINE AND

UKRAINIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Luckyj, George S. N. (1991). Young Ukraine: The Brother-

hood of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Kiev, 1845–1847.

Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

S

ERHY

Y

EKELCHYK

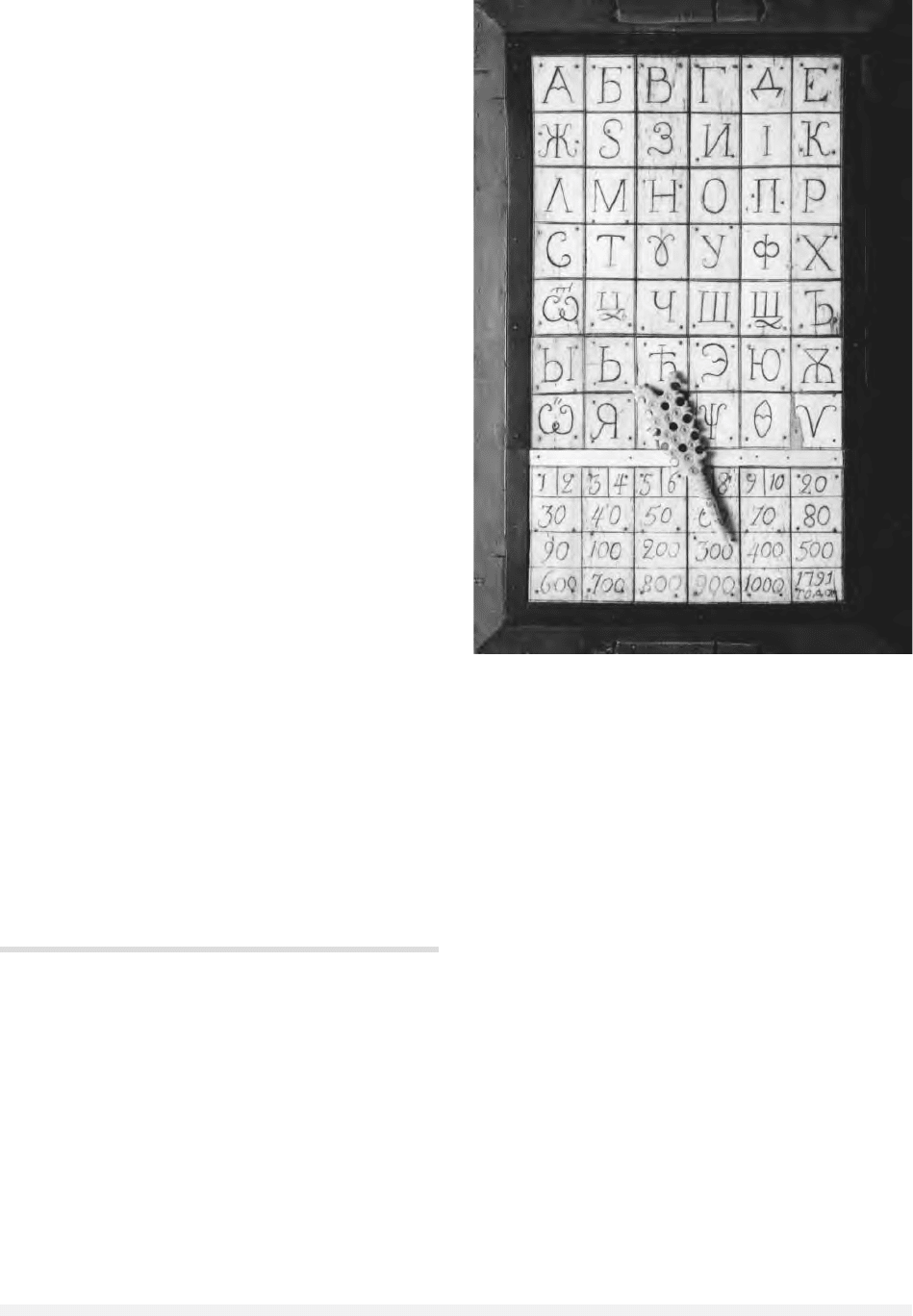

CYRILLIC ALPHABET

Russian and other Slavic languages are written us-

ing the Cyrillic alphabet. The letter system has been

attributed to Cyril and Methodius, two brothers

from Greek Macedonia working as Orthodox mis-

sionaries in the ninth century. Cyril invented the

Glagolitic (from the word glagoliti, “to speak”)

script to represent the sounds they heard spoken

among the Slavic peoples. By adapting church rit-

uals to the local tongue, the Orthodox Church be-

came nationalized and more accessible to the

masses. Visually, Glagolitic appears symbolic or

runic. Later St. Clement of Ohrid, a Bulgarian arch-

bishop who studied under Cyril and Methodius,

created a new system based on letters of the Greek

alphabet and named his system “Cyrillic,” in honor

of the early missionary.

Russian leaders have standardized and stream-

lined the alphabet on several occasions. In 1710,

Peter the Great created a “civil script,” a new type-

face that eliminated “redundant” letters. Part of Pe-

ter’s campaign to expand printing and literacy, the

civil script was designated for all non-church pub-

lications. The Bolsheviks made their own ortho-

graphic revisions, dropping four letters completely

to simplify spelling. As non-Russian lands were in-

corporated into the Soviet Union, the Communist

Party decreed that all non-Russian languages had

to be rendered using the Cyrillic alphabet. Follow-

ing the collapse of the USSR, most successor states

seized the opportunity to restore their traditional

Latin or Arabic script as a celebration of their na-

tional heritage.

CYRILLIC ALPHABET

354

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

An eighteenth-century carved bone and wood panel with the

Cyrillic alphabet. © M

ASSIMO

L

ISTRI

/CORBIS

Transliteration is the process of converting let-

ters from one alphabet to another alphabet system.

There are several widely used systems for translit-

erating Russian into English, including the Library

of Congress system, the U.S. Board of Geographic

Names system, and the informally named “lin-

guistic system.” Each system offers its own ad-

vantages and disadvantages in terms of ease of

pronunciation and linguistic accuracy.

This Encyclopedia uses the U.S. Board of Geo-

graphic Names system, which is more accessible for

non-Russian speakers. For example, it renders the

name of the first post-communist president as

“Boris Yeltsin,” not “Boris El’tsin.” The composer of

the Nutcracker Suite and the 1812 Overture becomes

“Peter Tchaikovsky,” not “Piotr Chaikovskii.”

See also: BYZANTIUM, INFLUENCE OF; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, SOVIET; PETER I

BIBLIOGRAPY

Gerhart, Genevra. (1974). The Russian’s World: Life and

Language. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1988). Russia in the Age of Peter the

Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

A

NN

E. R

OBERTSON

CYRIL OF TUROV

(c. 1130–1182), twelfth-century church writer,

bishop.

The facts of Cyril’s (Kirill’s) life and career are

disputable, since contemporary sources for both are

lacking. Customarily, it is asserted that he was

born to a wealthy family in Turov, northwest of

Kiev, about 1130 and died not later than 1182;

that he was a monk who rose to be bishop of Turov

in the late 1160s; and that he wrote letters to

Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky about a rival bishop.

Cyril’s brief Prolog (Synaxarion) life (translation

in Simon Franklin’s Sermons and Rhetoric of Kievan

Rus’), written probably long after his death, is the

only “authority” for most of these claims, al-

though it is vague and gives no dates. Whether all

of the works attributed to him were his, and

whether he was ever in fact a bishop (the texts

usually call him simply the “unworthy” or “sin-

ful monk Cyril”) are matters of speculation and

scholarly convention.

Tradition credits more extant writings to Cyril

of Turov than to any other named person thought

to have lived in the Kievan period. They include ser-

mons, parables, and edifying stories. The corpus of

texts attributed to Cyril was critically studied and

edited in the 1950s by the late philologist Igor

Petrovich Yeremin. Simon Franklin considers the

“stable core” of the oeuvre to consist of three sto-

ries and eight sermons, while various other writ-

ings have frequently been added.

The eight sermons, which no doubt are Cyril’s

most admired works today, form a cycle for the

Easter season stretching from Palm Sunday to the

Sunday before Pentecost. Like the famous Sermon

on Law and Grace of Hilarion, they are heavily de-

pendent on Byzantine Greek sources and, of course,

incorporate many Biblical quotations and para-

phrases. The original accomplishment of Cyril was

to express all this in a fluent and vigorous Church

Slavonic language that makes it fresh and living.

Cyril’s style is elaborate and rich in poetic tropes,

particularly metaphors. A familiar example is his

extended comparison of the resurrection with the

coming of spring in the world of nature, where (in

the manner of Hilarion) he quickly resolves the

metaphors and reveals explicitly the higher mean-

ing for salvation history.

Another typical feature of Cyril’s sermons is

the extensive use of dramatic dialogue, very wel-

come in a church literature otherwise devoid of

liturgical drama. Thus the speech of Joseph of Ari-

mathaea (with his repeated plea, “Give me body of

Christ”) and others in the Sermon for Low Sunday

both instruct and convey deep emotion.

See also: HILARION; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Franklin, Simon, tr. and intro. (1991). Sermons and

Rhetoric of Kievan Rus’. Harvard Library of Early

Ukrainian Literature, Vol. 5. Cambridge, MA: Dis-

tributed by the Harvard University Press for the

Ukrainian Research Institute of Harvard University.

N

ORMAN

W. I

NGHAM

CZARTORYSKI, ADAM JERZY

(1770–1861), Polish statesman, diplomat, and sol-

dier.

Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski was the scion of

an aristocratic Polish family, the son of Prince Adam

Kazimierz and Izabella (nee Fleming) Czartoryski.

CZARTORYSKI, ADAM JERZY

355

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

He fought in the Polish army during the war of the

second partition in 1793, after which his father’s

estates were confiscated by the Russians. In a last-

ditch attempt to salvage his property, Czartoryski’s

father sent Adam and his brother Constantine to the

Court of St. Petersburg. Summoning all his courage,

Czartoryski befriended the grandson of Empress

Catherine II, the Grand Duke Alexander, in the

spring of 1796. Hoping that Alexander would soon

be tsar, Czartoryski filled his friend’s head with ideas

about Polish freedom. When Alexander became em-

peror in 1801, after the murder of his father Paul,

he appointed Czartoryski as Russian Minister of For-

eign Affairs.

Now one of Tsar Alexander’s trusted advisors,

Czartoryski intervened on behalf of the Poles when-

ever he could, repeatedly advocating the restoration

of Poland to its 1772 boundaries, a Russian-

English alliance, and the diplomatic recognition of

Napoleonic France as a method of deterrence.

Deeming Austria and Prussia to be Russia’s main

enemies, Czartoryski resigned in protest when the

tsar formed an alliance with Prussia. He neverthe-

less continued to champion Polish independence af-

ter Napoleon’s unsuccessful war with Russia,

attending the Congress of Vienna (1814) and plead-

ing with British and French statesmen. On May 3,

1815, the Congress of Vienna did establish the so-

called Congress Kingdom of Poland, a small state

united with Russia but possessing its own army

and local self-government. Cruelly, however,

Alexander appointed Adam’s brother Constantine

as commander-in-chief of the Polish army and

shunted Adam aside, never to be called again to

government service.

Czartoryski participated in the Polish insurrec-

tion of 1830 and 1831, and briefly headed a pro-

visional Polish government. However, the Russians

crushed the rebellion, and Czartoryski was sen-

tenced to death. Fleeing to Paris, he set up a polit-

ical forum for Polish émigrés from the Hôtel

Lambert, where he resided. Only among the Hun-

garians, in armed revolt against the Habsburg em-

pire in 1848, did the Hôtel Lambert group find, and

give, support. Many Poles joined the Hungarian

army as officers and soldiers. Nevertheless, the Ho-

tel’s influence also faded, along with Czartoryski’s

dream of Polish independence in his lifetime.

See also: ALEXANDER I; POLAND

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Czartoryski, Adam Jerzy, and Alexander; Gielgud Adam.

(1968). Memoirs, Prince Adam Czartoryski and His

Correspondence with Alexander I, with Documents Rel-

ative to the Prince’s Negotiations with Pitt, Fox, and

Brougham, and an Account of his Conversations with

Lord Palmerston and Other English Statesmen in Lon-

don in 1832. Orono, ME: Academic International.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

CZECHOSLOVAK CORPS See CIVIL WAR OF

1917–1922.

CZECHOSLOVAKIA, INVASION OF

Late in the evening of August 20, 1968, Czecho-

slovakia was invaded by five of its Warsaw-Pact

allies: the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland,

Hungary, and Bulgaria. The invasion force, which

eventually totaled around half a million soldiers,

6,300 tanks, and 800 airplanes, targeted its entry

from the north, northwest, and south to quickly

neutralize the outnumbered Czechoslovak army.

The immediate objective of the invasion was to

prevent any resistance to the seizure of power by

collaborators in the Czechoslovak Communist

Party (KSC

), who had signaled their agreement

with Soviet disapproval of First Secretary Alexan-

der Dubc

ek’s reform program and leadership style.

Although it caused the deaths of around 100 civil-

ians and is often credited with putting an end to

the “Prague Spring,” the invasion failed in many

political and logistical respects, and its larger aims

were met only months later by other means.

The possibility of military intervention in

Czechoslovakia had been entertained in the Brezh-

nev Politburo from at least as early as March 1968,

only weeks after Dubc

ek had risen (with Soviet

blessing) to the top of the KSC

. At first, the ma-

jority of Soviet leaders preferred to pressure Dubc

ek

into reimposing censorship over the mass media,

silencing critical intellectuals, and removing the

bolder reformers within the party. His repeated

promises to restore control temporarily prevailed

over the demands of Polish, East German, and Bul-

garian leaders for Soviet-led military action. The

Politburo was also restrained by its lack of personal

contacts with, and trust in, other Czech and Slo-

vak functionaries, to whom power would have to

be entrusted.

By mid-July 1968, Soviet patience with Dubc

ek

had been exhausted, and alternative leaders had

CZECHOSLOVAKIA, INVASION OF

356

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

been identified. Under the cover of war games in

and around Czechoslovakia, twenty divisions

moved into striking position. After the failure of

several last attempts to persuade Dubc

ek to take

the initiative in reversing his reforms, the Politburo

concluded on August 17 that military intervention

was unavoidable. The Czech and Slovak collabora-

tors, however, botched their bid to seize power, and

the invading armies’ overextended supply lines

broke down, forcing soldiers to beg for food and

water from a hostile populace engaging in highly

effective, nonviolent resistance. In Moscow, the So-

viet powers decided to bring Dubc

ek and his clos-

est colleagues to the Kremlin. After three days of

talks, a secret protocol was signed that committed

the KSC

leadership to the restoration of censorship

and a purge of the party apparatus and govern-

ment ministries. Dubc

ek remained at the helm of

the KSC

until April 1969, when Moscow-fueled in-

trigue led to his replacement by the more amenable

Gustáv Husák.

See also: BREZHNEV DOCTRINE; CZECHOSLOVAKIA, RELA-

TIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dawisha, Karen. (1984). The Kremlin and the Prague

Spring. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kramer, Mark. (1992–1993). “New Sources on the 1968

Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia.” Cold War Inter-

national History Project Bulletin, 2–3.

Williams, Kieran. (1997). The Prague Spring and its After-

math: Czechoslovak Politics, 1968–1970. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

K

IERAN

W

ILLIAMS

CZECHOSLOVAKIA, RELATIONS WITH

Both the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia were

born from the collapse of European empires at the

CZECHOSLOVAKIA, RELATIONS WITH

357

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

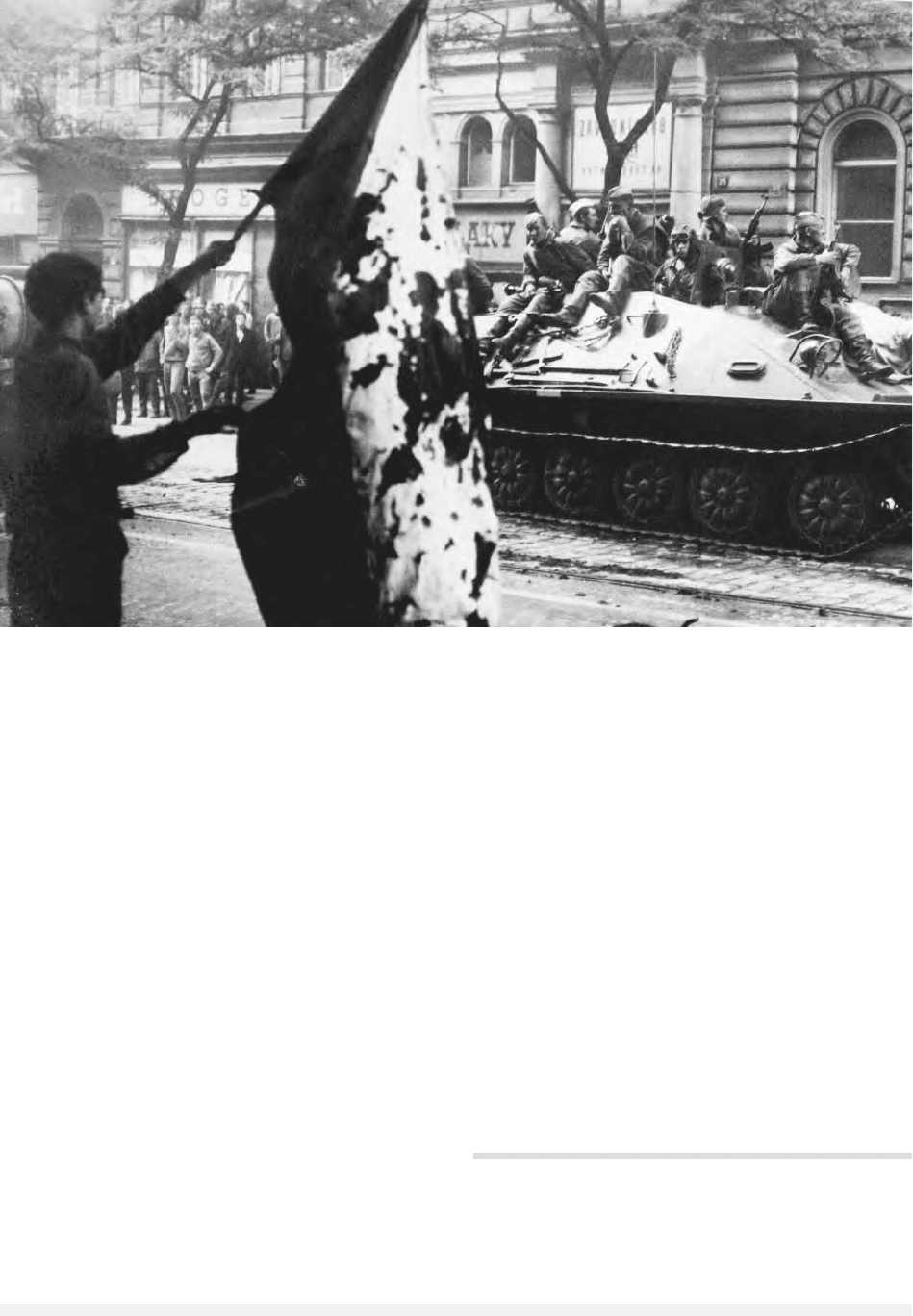

A Czech youth displays a bloodstained flag to Soviet troops sprawled atop a passing tank in Prague, August 21, 1968. © B

ETTMANN

/

CORBIS

close of World War I. While the USSR rose directly

from the rubble of the Russian Empire, the Paris

Peace Conference crafted Czechoslovakia from Aus-

tro-Hungarian lands. From the outset, the Czech

lands (Bohemia and Moravia) and Slovakia had as

many differences as similarities, and tensions be-

tween the two halves of the state would resurface

throughout its lifetime and eventually contribute

to its demise in 1992.

Under the leadership of President Tomas G.

Masaryk, Czechoslovakia was spared many of the

problems of the interwar period. Its higher levels

of industrialization helped it weather the financial

crises of the 1920s better than its more agrarian

neighbors. Czechoslovakia also remained a democ-

racy, ruled by the “Petka”—the five leading political

parties. Democracy ended only when Czechoslova-

kia was seized by Nazi Germany, first through the

Munich Agreement of 1938, and later through di-

rect occupation of Bohemia and Moravia in 1939.

A separate Slovak state was established under Nazi

protection in 1939. Ultimately, Soviet troops lib-

erated Czechoslovakia in 1945.

Following World War II, Stalin moved to first

install satellite regimes throughout Eastern Europe

and then mold them to emulate Soviet structures.

Unlike other future members of the Warsaw Pact,

however, Czechoslovakia’s communists were

homegrown, not installed by Moscow. A Commu-

nist Party of Czechoslovakia (CPCz) had been es-

tablished in 1921 and had a much broader support

base than the Soviet party. Communists served in

the first post-war government of President Eduard

Benes, taking a plurality (38 percent) of the vote

in May 1946. They controlled key ministries, in-

cluding the Interior, Education, Information, and

Agriculture. They also acceded to Soviet pressure

to not participate in the Marshall Plan reconstruc-

tion program. The CPCz seized power in February

1948, when non-Communist cabinet members re-

signed, hoping to force new elections. A handful of

other parties competed in the May 1948 election,

but the Communists were in charge. Benes resigned

the presidency in June and was replaced by Com-

munist Klement Gottwald.

Gottwald and CPCz First Secretary Rudolf Slan-

sky then began a program of restructuring Czecho-

slovakia in the Soviet image. Noncommunist

organizations were banned, economic planning

was introduced, agriculture was collectivized, and

media and educational institutions were subjected

to ideological controls. Again emulating Stalin, the

Czechoslovak communists used terror and purges

to consolidate their rule. Even Slansky succumbed

to the purges; he was replaced by Antonin Novotny.

Following Gottwald’s death in 1953, Antonin Za-

potocky became president.

The other major communist death of 1953,

Stalin’s, had little effect on Czechoslovakia. Like

hard-line communist leaders in East Germany, of-

ficials in Prague did not embrace Nikita Khrush-

chev’s efforts at liberalization and pluralism. They

kept tight control over the Czechoslovak citizenry

for the next fifteen years, using the secret police as

necessary to enforce their rule. Public protest was

minimal, in part due to the relative success—by

communist standards—of Czechoslovakia’s econ-

omy.

In January 1968 the CPCz removed Novotny

and replaced him with Alexander Dubcek, who fi-

nally brought destalinization to Czechoslovakia.

The CPCz now allowed broader political discussion,

eased censorship, and tried to address Slovak com-

plaints of discrimination. This new approach, called

“socialism with a human face” led to a resurgence

in the country’s social, political, and economic

life—an era that came to be called the Prague

Spring. Soon popular demands exceeded the Party’s

willingness to reform. The CPCz’s “Action Plan”

was countered by “2,000 Words,” an opposition

list of grievances and demands.

The Kremlin kept a close eye on all develop-

ments in Czechoslovakia. Khrushchev had dis-

patched tanks to Budapest in 1956 when

Hungarian Communists took reform too far. His

successor, Leonid Brezhnev, was even less inclined

to allow for experimentation. By summer, Moscow

worried that Dubcek had lost control. Moscow de-

clared its right to intervene in its sphere of influ-

ence by promulgating the Brezhnev Doctrine. On

August 21, 1968, Warsaw Pact troops invaded to

restore order. Dubcek was summoned to Moscow

but not immediately fired.

In 1969 “socialism with a human face” was re-

placed with a new policy: normalization. Gustav

Husak became the CPCz first secretary in April

1969, and Dubcek was dispatched to the forests of

Slovakia to chop wood. Husak took orders from

Moscow, turning Czechoslovakia into one of the

Soviet Union’s staunchest allies. The Party purged

itself of reformist elements, alternative organiza-

tions shut down, and censorship was reimposed.

In October 1969, Moscow and Prague issued a joint

statement, announcing that their economies would

be coordinated for the next six years.

CZECHOSLOVAKIA, RELATIONS WITH

358

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The populace fell in line, quietly accepting the

reversal of the Prague Spring. The communist lead-

ers tried to temper the political hard-line by main-

taining a high standard of living and plentiful

consumer goods. As the shock of the crackdown

faded, however, a handful of opposition move-

ments emerged trying to keep alive the spirit of

1968. The best-known of these groups was Char-

ter 77, named for the January 1977 declaration

signed by 250 dissidents, including playwright and

future president Vaclav Havel.

The rise of Gorbachev in 1985 alarmed the

CPCz. The hard-line communist leaders of Czecho-

slovakia did not embrace Gorbachev’s brand of new

thinking. They stubbornly held onto their austere

rule, while the economy began to skid. They had

come to power in 1969 to block reform; they could

hardly shift and embrace it now. Gorbachev’s first

official visit to Czechoslovakia, in 1987, raised

hopes—and fears—that he would call for a resur-

rection of the 1968 reforms, but instead he made

rather bland comments that relieved the Czech lead-

ers. They believed they now had Moscow’s bless-

ing to ignore perestroika. Husak retired as First

Secretary—but not President—in late 1987, appar-

ently for personal reasons rather than on Moscow’s

order. His replacement, Milos Jakes, was another

hard-line communist with no penchant for reform.

Czechoslovakia was one of the last states to ex-

perience popular demonstrations and strikes in the

cascading events of late 1989. The West German

embassy in Prague was overrun by thousands of

East Germans seeking to emigrate. When the other

hard-line holdout, East Germany, collapsed in

October, suddenly the end of communism in Czecho-

slovakia seemed possible. Unable to address popu-

lar demands, the Czechoslovak Politburo simply

resigned en masse, after barely a week of demon-

strations. Havel became president; Dubcek returned

from internal exile to lead parliament.

The Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991

and the Czech Republic and Slovakia divorced on

December 31, 1992. Initially, the new Czech state

tilted westward, whereas Slovakia leaned toward

Moscow, in part because its economy was still ori-

ented in that direction. As the 1990s unfolded, both

countries maintained proper ties with Moscow, but

also joined NATO: the Czech Republic in 1999, Slo-

vakia in 2002.

See also: CZECHOSLOVAKIA, INVASION OF; WARSAW

TREATY ORGANIZATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brzezinski, Zbigniew K. (1967). The Soviet Bloc: Unity and

Conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gati, Charles. (1990). The Bloc That Failed: Soviet-East Eu-

ropean Relations in Transition. Bloomington: Indiana

University Press.

Skilling, H. Gordon. (1976). Czechoslovakia’s Interrupted

Revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wolchik, Sharon L. (1991). Czechoslovakia in Transition:

Politics, Economics, and Society. London: Pinter.

A

NN

E. R

OBERTSON

CZECHOSLOVAKIA, RELATIONS WITH

359

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

This page intentionally left blank

DAGESTAN

Dagestan, part of the ethnically diverse Caucasus

region, is an especially rich area of ethnic and lin-

guistic variety. An Autonomous Soviet Socialist Re-

public of the RSFSR during the Soviet period, it has

continued to be an autonomous republic of the

Russian Federation since. There are twenty-six dis-

tinct languages in the Northeast Caucasian family.

The majority of these languages’ speakers live in

Dagestan. The largest of these are Avar, Dargin,

and Lezgin. The total population of the Dagestan

A.S.S.R. in 1989 was 1.77 million. Many other na-

tionalities, such as Russians, also live in Dagestan.

The capital of Dagestan is Makhachkala, lo-

cated on the Caspian Sea. The Terek River is the

most important river in Dagestan, flowing from

Chechnya and toward the Caspian Sea. There is a

small coastal plain that gives rise quickly to the

eastern portion of the main Caucasus range. The

most intense ethno-linguistic diversity is found in

the mountains as a result of the isolation that his-

torically separated groups of people. The northern

part of Dagestan connects with the Eurasian steppe.

Many of the people of Dagestan are descendents

of the residents of the ancient Caucasian Albanian

Kingdom. This kingdom was known for its multi-

plicity of languages and was Christian for many

centuries, having close relations with the Armen-

ian people and their Christian culture.

Dagestanis were traditionally Muslims peoples.

Attempts in the post-Soviet period to incite Islam-

based rebellion, however, have been generally un-

successful. These rebellions have come from the

direction of the troubled Republic of Chechnya,

which is located west of Dagestan. The Islam of

Dagestan was traditionally a Sufi-based Islam, one

that is inimical to the sort of puritanical Sunni sec-

tarianism that is exported from other parts of the

Islamic world. Sufism in this part of the world is

not without its militant expression; one of the most

famous leaders, Shamil, was an Avar of Dagestan.

His power base was mainly in the Central Cauca-

sus among the Chechens.

Unlike many of their other neighbors in the

Caucasus, the Dagestanis, for the most part, did not

experience the exile and deportation in the nineteenth

and twentieth centuries. This makes the narrative of

their people much less filled with the anger and

alienation that characterizes Chechen, Abkhazian,

and other histories. The ethnic fragmentation of

D

361

Dagestan has also prevented a unified Dagestani na-

tional identity from being formed.

The Russian Empire appeared in this area in two

different forms: by the Cossacks who lived at the

periphery of the empire in the semiautonomous

communities; and by means of the imperial army’s

movement down the Volga River and to the west-

ern shore of the Caspian. Peter the Great captured

territory in this area, but Dagestan was not fully

brought into the Russian Empire until the mid-

nineteenth century.

The Soviet period saw the creation of Cyrillic-

based alphabets for the various languages of Dages-

tan. This strengthened the existence of the larger

languages, and may have forestalled the extinction

of some of the smallest of the languages. It also

served to forestall the creation of a united Dages-

tani national identity.

In the post-Soviet period, in addition to Islamic

agitation from the west, there has also been a

certain amount of ethnic conflict. The conflict is

generally over who will control the politics and pa-

tronage of certain enclaves, while the larger groups

jockey for position in the republic’s government.

Some of the conflicts result from the ethnic mix-

ing that was encouraged and sometimes forced dur-

ing the Soviet period.

See also: AVARS; CAUCASUS; DARGINS; ISLAM; LEZGINS;

NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hill, Fiona. (1995). “Russia’s Tinderbox: Conflict in the

North Caucasus and Its Implication for the Future

of the Russian Federation.” Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University, Strengthening Democratic Institutions

Project.

Karny, Yo’av. (2000). Highlander: A Journey to the Cau-

casus in Quest of Memory. New York: Farrar, Straus

and Giroux.

P

AUL

C

REGO

DANIEL, METROPOLITAN

(d. 1547), Metropolitan of Moscow, 1522–1539;

leading Josephite and “Possessor.”

Daniel was a native of Ryazan with a powerful

frame, an encyclopedic turn of mind, a preacher’s

bent, and disciplined work habits. He was tonsured

by Joseph of Volokolamsk (also known as Iosif or

Joseph of Volotsk) around 1500 and designated to

succeed him before his death in 1515, when he and

his monastery were under virulent attack by Vass-

ian Patrikeyev and out of favor at court.

As abbot, Daniel demonstrably enforced the

rule of communal property, and the cloister con-

tinued its remarkable growth as a landowner and

center of learning, training future prelates, and

writing. He oversaw the completion of the extended

redactions of Joseph’s Enlightener and Monastic

Rule and masterminded the creation of the Nikon

Chronicle with its milestone grand narrative, sacral-

izing Rus history and granting Moscow the con-

tested succession to Kiev.

Selected metropolitan by Basil III, Daniel issued

a worthless writ of safe-conduct to a suspect ap-

panage prince (1523) and permitted Basil’s contro-

versial divorce and remarriage (1525), which

resulted in the birth of the future Ivan IV (1530).

In turn Daniel was able to organize synods against

Maxim Greek (1525, 1531) and Vassian (1531),

and canonize Joseph’s mentor Pafnuty of Borovsk.

Daniel also placed an enterprising ally, Macarius,

on the powerful, long vacant archepiscopal see of

Novgorod (1526) and Iosifov trainees as bishops of

Tver (1522), Kolomna (1525), and Smolensk

(1536). Presiding over Basil III’s pre-death tonsure

and the oaths to the three-year-old Ivan IV (1533),

Daniel remained on his throne through the dowa-

ger Helen Glinsky’s regency (1533–1538), but

could not exercise his designated supervisory role,

prevent murderous infighting at top, or keep his

post after she died.

Using his office to bolster church authority,

Daniel systematized canon law and the metropol-

itan’s chancery, built up its library, and tried to

impose Iosifov practices on some other monaster-

ies. He handled dissenting voices in a variety of

ways. The 1531 synodal sentences ended Vassian

Patrikeyev’s career with imprisonment in Iosifov,

but permitted the less bellicose and eminently use-

ful Maxim a milder house arrest in Tver. Fore-

grounding the Orthodox principle of patient

endurance in public life, Daniel contested the diplo-

mat Fyodor Karpov’s Aristotle-based insistence

upon justice, but did not prosecute him. Daniel also

utilized Basil III’s German Catholic physician

Nicholas Bülew and commissioned Russia’s first

translation of a Western medical work, but

obliquely opposed by pen Bülew’s astrology and

DANIEL, METROPOLITAN

362

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY