Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ket economy. Although the process of privatiza-

tion was flawed, a vast shift of property rights

away from the state toward individuals and the

corporate sector occurred. The main success of eco-

nomic reforms were macroeconomic stabilization

(gaining control over the inflation, relative reduc-

tion of government deficit, and so forth) as well as

initial steps toward creating a modern financial

system for allocating funds according to market

criteria. The banking system was privatized, and

both debt and equity markets emerged. There was

an effort to use primarily domestic markets to fi-

nance the government debt.

In contrast to other ex-Soviet countries in Cen-

tral Europe, Russia could not quickly overcome the

initial output decline at the beginning of market re-

forms. Russia’s economy contracted for five years

as the reformers appointed by President Boris

Yeltsin hesitated over the implementation of the ba-

sic foundations of a market economy. Russia

achieved a slight recovery in 1997 (GDP growth of

1%), but stubborn budget deficits and the country’s

poor business climate made it vulnerable when the

global financial crisis began in 1997. The August

1998 financial crisis signaled the fragility of the

Russian market economy and the difficulties poli-

cymakers encountered under imperfect market

conditions.

The crisis sent the entire banking system into

chaos. Many banks became insolvent and shut

down. Others were taken over by the government

and heavily subsidized. The crisis culminated in

August 1998 with depreciation of the ruble, a debt

default by the government, and a sharp deteriora-

tion in living standards for most of the population.

For the year 1998, GDP experienced a 5 percent de-

cline. The economy rebounded in 1999 and 2000

(GDP grew by 5.4% in 1999 and 8.3% in 2000),

primarily due to the weak ruble and a surging trade

surplus fueled by rising world oil prices. This re-

covery, along with renewed government effort in

2000 to advance lagging structural reforms, raised

business and investor confidence concerning Rus-

sia’s future prospects. GDP is expected to grow by

over 5.5 percent in 2001 and average 3–4 percent

(depending on world oil prices) from 2002 through

2005. In 2003 Russia remained heavily dependent

on exports of commodities, particularly oil, nat-

ural gas, metals, and timber, which accounted for

over 80 percent of its exports, leaving the country

vulnerable to swings in world prices. Macroeco-

nomic stability and the improved business climate

can easily deteriorate with changes in export com-

modity prices and excessive ruble appreciation. Ad-

ditionally, inflation remained high according to in-

ternational standards: From 1992 to 2000, Russia’s

average annual rate of inflation was 38 percent.

Russia’s agricultural sector remained beset by un-

certainty over land ownership rights, which dis-

couraged needed investment and restructuring. The

industrial base was increasingly dilapidated and

needed to be replaced or modernized if the country

was to achieve sustainable economic growth.

Three basic factors caused Russia’s transition

difficulties, including the absence of broad-based

political support for reform, inability to close the

gap between available public resources and gov-

ernment spending, and inability to push forward

systematically with structural reforms. Russia’s

second president, Vladimir Putin, elected in March

2000, advocated a strong state and market econ-

omy, but the success of his agenda was challenged

by his reliance on security forces and ex-KGB as-

sociates, the lack of progress on legal reform, wide-

spread corruption, and the ongoing war in

Chechnya. Despite tax reform, the black market

continued to account for a substantial share of

GDP. In addition, Putin presented balanced budgets,

enacted a flat 13 percent personal income tax, re-

placed the head of the giant Gazprom natural gas

monopoly with a personally loyal executive, and

pushed through a reform plan for the natural elec-

tricity monopoly. The fiscal burden improved. The

cabinet enacted a new program for economic re-

form in July 2000, but progress was undermined

by the lack of banking reform and the large state

presence in the economy. After the 1998 crisis,

banking services once again became concentrated in

the state-owned banks, which lend mainly to the

business sector. In 2000 state banks strengthened

their dominant role in the sector, benefiting from

special privileges such as preferential funding

sources, capital injections, and implicit state guar-

antees. Cumulative foreign direct investment since

1991 amounted to $17.6 billion by July 2001,

compared with over $350 billion in China during

the same period. A new law on foreign investments

enacted in July 1999 granted national treatment to

foreign investors except in sectors involving na-

tional security. Foreigners were allowed to estab-

lish wholly owned companies (although the

registration process can be cumbersome) and take

part in the privatization process. An ongoing con-

cern of foreign investors was property rights pro-

tection: Government intervention increased in scope

as the enforcement agencies and officials in the at-

torney general’s office attempted to re-examine pri-

ECONOMY, POST-SOVIET

433

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

vatization outcomes. The most significant barriers

to foreign investment and sustainable economic

growth continued to be the weak rule of law, poor

infrastructure, legal uncertainty, widespread cor-

ruption and crime, capital flight, and brain drain

(skilled professionals emigrating from Russia).

See also: BLACK MARKET; FOREIGN DEBT; PUTIN, VLADIMIR

VLADIMIROVICH; RUSSIAN FEDERATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (2001). Russian

and Soviet Economic Performance and Structure.

Boston, MA: Addison Wesley.

Gustafson, Thane. (1999). Capitalism Russian-style.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

P

AUL

R. G

REGORY

ECONOMY, TSARIST

The economy of the Russian Empire in the early

twentieth century was a complicated hybrid of tra-

ditional peasant agriculture and modern industry.

The empire’s rapidly growing population (126 mil-

lion in 1897, nearly 170 million by 1914) was

overwhelmingly rural. Only about 15 percent of

the population lived in towns, and fewer than 10

percent worked in industry. Agriculture, the largest

sector of the economy, provided the livelihood

for 80 percent of the population and was domi-

nated by peasants, whose traditional household

economies were extremely inefficient compared to

agriculture in Western Europe or the United States.

But small islands of modern industrial capitalism,

brought into being by state policy, coexisted with

the primitive rural economy. Spurts of rapid in-

dustrialization in the 1890s and in the years before

World War I created high rates of economic growth

and increased national wealth but also set in mo-

tion destabilizing social changes. Despite its islands

of modernity, the Russian Empire lagged far behind

advanced capitalist countries like Great Britain and

Germany, and was unable to bear the economic

strains of World War I.

The country’s agricultural backwardness was

rooted in the economic and cultural consequences

of serfdom, and it was reinforced by the govern-

ment’s conservative policies before the Revolution

of 1905. The Emancipation Act of 1861, while

nominally freeing the peasantry from bondage,

sought to limit change by shoring up the village

communes. In most places the commune contin-

ued to control the amount of land allotted to each

household. Land allotments were divided into scat-

tered strips and subject to periodic redistribution

based on the number of workers in each house-

hold; and it was very difficult for individual peas-

ants to leave the commune entirely and move into

another area of the economy, although increasing

numbers worked as seasonal labor outside their vil-

lages (otkhodniki). Rapid population growth only

worsened the situation, for as the number of peas-

ants increased, the size of land allotments dimin-

ished, creating a sense of land hunger.

Most peasants lived as their ancestors had, at

or near the margin of subsistence. Agricultural pro-

ductivity was constrained by the peasantry’s lack

of capital and knowledge or inclination to use mod-

ern technology and equipment; most still sowed,

harvested, and threshed by hand, and half used a

primitive wooden plow. In 1901 a third of peas-

ant households did not have a horse. Poverty was

widespread in the countryside. Items such as meat

and vegetable oil were rarely seen on the table of a

typical peasant household.

After the 1905 revolution the government of

Peter Stolypin (minister of the interior, later pre-

mier) enacted a series of laws designed to reform

agriculture by decreasing the power of the village

communes: Individual peasant heads of households

were permitted to withdraw from the commune

and claim private ownership of their allotment

land; compulsory repartitioning of the land was

abolished and peasants could petition for consoli-

dation of their scattered strips of land into a single

holding. However, bureaucratic processes moved

slowly. When World War I began, only about one-

quarter of the peasants had secured individual

ownership of their allotment land and only 10 per-

cent had consolidated their strips. While these

changes allowed some peasants (the so-called ku-

laks) to adopt modern practices and become pros-

perous, Russian agriculture remained backward

and underemployment in the countryside remained

the rule. In increasing numbers peasants took out

passports for seasonal work, many performing un-

skilled jobs in industry.

Industrialization accelerated in the 1890s,

pushed forward by extensive state intervention un-

der the guidance of Finance Minister Sergei Witte.

He used subsidies and direct investment to stimu-

late expansion of heavy industry, imposed high

taxes and tariffs, and put Russia on the gold stan-

dard in order to win large-scale foreign investment.

ECONOMY, TSARIST

434

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Although the process slowed from 1900 through

the 1905 revolution, it soon picked up again and

was very strong from 1910 to the outbreak of the

war. The rate of growth in the 1890s is estimated

to have been an impressive 8 percent a year. While

the growth rate after 1910 was slightly lower

(about 6%), the process of economic development

was broader and the government’s role diminished.

Railroad construction, so critical to economic

development, increased greatly toward the end of

the nineteenth century with the construction of the

Trans-Siberian Railroad and then rose another 20

percent from 1903 to 1914. Although the number

of miles of track per square mile and per capita was

the lowest in Europe, the railroad-building boom

stimulated great expansion in the related industries

of iron and steel, coal, and machine building.

Industrial production came to be concentrated

in large plants constructed during the period of

rapid industrialization. In 1914, 56 percent of the

employees in manufacturing worked in enterprises

that employed five hundred or more workers, and

40 percent in plants employing one thousand or

more workers. Such large-scale production fre-

quently incorporated the most up-to-date technol-

ogy. In a number of key industries production was

concentrated in a few large oligopolies.

Starting in the later 1890s foreign investment

became an important factor in the economy. In

1914 it amounted to one-third of total capital in-

vestment in Russian industry, most of it in min-

ing, metallurgy, banking, and textiles. France,

England, and Germany were the primary sources

of foreign capital. Foreign trade policy was domi-

nated by protectionism. Tariffs just before the war

averaged an astonishing 30 to 38 percent of the ag-

gregate value of imports, two to six times higher

than in the world’s most developed economies. Pre-

dictably, this led to higher prices.

Russia was highly dependent on Western im-

ports of manufactured goods, largely from Ger-

many. Raw materials, such as cotton, wool, silk,

and nonferrous metals, comprised about 50 per-

cent of all imports. Exports were dominated by

grains and other foodstuffs (55% of the total). Rus-

sia was the world’s largest grain exporter, supply-

ing Western Europe with about one-third of its

wheat imports and about 50 percent of its other

grains.

The productivity of labor was extremely low

because of the deficient capital endowment per

worker. In 1913 horsepower per industrial worker

in Russia was about 60 percent of that per worker

in England and one-third the level per an Ameri-

can worker. In addition, many industrial workers

were still connected to their villages and spent part

of their time farming. Because of these factors the

costs of production were considerably higher in

Russian industry than in Western Europe.

Russian workers faced wretched working con-

ditions and long hours with little social protection.

Wages were so low that virtually the entire income

of a household went to pay for basic necessities.

Living space was meager and miserable, and there

were few if any educational opportunities. In the

face of these circumstances, some turned to self-

help, and the cooperative movement made rapid ad-

vances. Many workers began to organize despite

the restrictions on trade unions even after the Rev-

olution of 1905. The labor movement renewed its

efforts in the years before the war, combining po-

litical and economic demands. From 1912 strikes

rose dramatically until in the first half of 1914 al-

most 1.5 million workers went on strike.

The tsarist economy collapsed under the strain

of World War I, inhibited by political as well as

economic limitations from meeting the demands of

total economic mobilization and undermined by

bad fiscal policy that led to destructive inflation.

But part of the collapse must be traced to prewar

roots. Chief among these was the still unresolved

legacy of the old serf system: an agricultural sys-

tem that was inefficient and inflexible, lacking in

capital and technology, heavily taxed, and, as a re-

sult, unable to provide a reasonable standard of liv-

ing for a rapidly growing population. Of near equal

importance were the consequences of the rapid in-

dustrialization in the two decades before the war.

Industrialization created the possibility of escaping

the limits of the agricultural system, but the way

it was carried out imposed most of the costs on the

common people and uprooted peasants from the

old society before the institutions and policies of a

new society had been created.

See also: AGRICULTURE; GRAIN TRADE; KULAKS; INDUS-

TRIALIZATION, RAPID; PEASANTRY; STOLYPIN, PETER

ARKADIEVICH; TRADE UNIONS; WITTE, SERGEI

YULIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dobb, Maurice H. (1948). Soviet Economic Development

since 1917. New York: International Publishers.

ECONOMY, TSARIST

435

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Gerschenkron, Alexander. (1962). Economic Backwardness

in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Gregory, Paul R. (1994). Before Command: An Economic

History of Russia from Emancipation to the First Five-

Year Plan. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mosse, Werner E. (1996). An Economic History of Russia,

1856–1914. London: Tauris.

C

AROL

G

AYLE

W

ILLIAM

M

OSKOFF

EDINONACHALIE

The one-person management principle used in the

Soviet economy to assign responsibility for the op-

eration and performance of economic units, from

industrial enterprises and R&D institutes to min-

istries and state committees.

Under edinonachalie, the head (rukovoditel or edi-

nonachalnik) of each administrative unit issued all

directives and took full responsibility for the results

the organization achieved. Edinonachalie was a key

feature of the Soviet management system from the

beginning of central planning in the early 1930s. It

did not literally mean, however, that one person

made every decision. In industrial ministries, major

manufacturing plants, and other large organiza-

tions, deputies or other subordinates who special-

ized in one or another sphere of operations were

authorized to make decisions in their designated ar-

eas of expertise on behalf of the head of the organi-

zation. Moreover, although fully responsible for the

organization’s performance, the edinonachalnik was

obliged to work with a consultative group of

deputies, department heads, workers, and other

technical personnel. This group could make decisions

and give advice, but their decisions could only be im-

plemented by the edinonachalnik, who, in both prin-

ciple and practice, was free to ignore their advice.

Edinonachalie made enterprise managers re-

sponsible for the collective of workers and the out-

come of the production process because it gave

them the authority to direct the capital, material,

and labor resources of the firm within the con-

straints of the targets and norms in the annual en-

terprise plan (techpromfinplan). Since the plan was

law in the Soviet economy, this identified the man-

ager as the person to punish if the plan was not

fulfilled.

The concentration of decision-making author-

ity and responsibility in the hands of the head of

the administrative unit was based upon a strict hi-

erarchical order. Subordinates to the edinonachal-

nik could not deal directly with higher authorities,

although they could report to higher authorities

that their superior was violating laws or rules.

See also: ENTERPRISE, SOVIET; TECHPROMFINPLAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kuromiya, Hiroaki. (1984). “Edinonchalie and the Soviet

Industrial Manager, 1928–1937.” Soviet Studies

36:185–204.

Kushnirsky, Fyodor. (1982). Soviet Economic Planning,

1965–1980. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Malle, Silvana. (1985). The Economic Organization of War

Communism, 1918–1921. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

S

USAN

J. L

INZ

EDUCATION

Education and literacy were highly politicized is-

sues in both Imperial and Soviet Russia, tied closely

to issues of modernization and the social order. The

development of an industrialized society and mod-

ern state bureaucracy required large numbers of

literate and educated citizens. During the Imperial

period, state officials faced what one scholar has

dubbed “the dilemma of education”: how to utilize

education without undermining Russia’s autocratic

government. During the early Soviet period, on the

other hand, the Bolsheviks attempted to use the ed-

ucation system as a tool of social engineering, as

they attempted to invert the old social hierarchy.

In both cases, the questions of which citizens

should be educated and what type of education they

should receive were as important as the actual ma-

terial they were to be taught.

THE EDUCATION SYSTEM IN

IMPERIAL RUSSIA, 1700–1917

Before 1700, Russia had no secular educational sys-

tem. Literacy, defined here as the ability to com-

prehend unfamiliar texts, was generally taught in

the home. Although there was a considerable spike

upwards in literacy in seventeenth-century Mus-

covy, the overall percentage of literate Russians re-

mained low. In 1700 no more than 13 percent of

the urban male population could read—for male

peasants, the rate was between 2 and 4 percent.

EDINONACHALIE

436

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

This was well below Western European literacy

rates, which exceeded 50 percent among urban

men. The hostility of many Orthodox officials to-

wards education and the absence of a substantial

urban class of burghers and artisans were two fac-

tors that contributed to Russia’s comparatively low

literacy rates.

Like many aspects of Russian society, the edu-

cational system was introduced and developed by

the state. Peter I opened the first secular schools—

institutes for training specialists, such as naviga-

tors and doctors—as part of his plan to turn Rus-

sia into a modern state. A number of important

institutions, such as Moscow University (1755),

were created in the next decades, but it was not un-

til 1786 that a ruler (Catherine II) attempted to cre-

ate a regular system of primary and secondary

schools.

This was only the first of many such plans ini-

tiated by successive tsars. The frequent reorgani-

zation of the school system was disruptive, and

since new types of schools were opened in addition

to, rather than in place of, existing schools, the sit-

uation became quite chaotic over time. This con-

fusion was compounded by the fact that many

schools lay outside the jurisdiction of the Ministry

of Education, which was created in 1802. Other

state ministries regularly opened their own schools,

ranging from technical institutes to primary

schools, and the Holy Synod sponsored extensive

networks of parochial schools. As a result, there

were sixty-seven different types of primary schools

in Russia in 1914.

Most schools fell into one of three categories:

primary, secondary, or higher education. Primary

schools were intended to provide students with ba-

sic literacy, numeracy, and a smattering of general

knowledge. As late as 1911, less than 20 percent

of primary school students went on to further

study. Many secondary schools were also terminal,

often with a vocational emphasis. Other secondary

schools, such as gymnasia, prepared students for

higher education. Higher education encompassed a

variety of institutions, including universities and

professional institutes.

EDUCATION

437

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

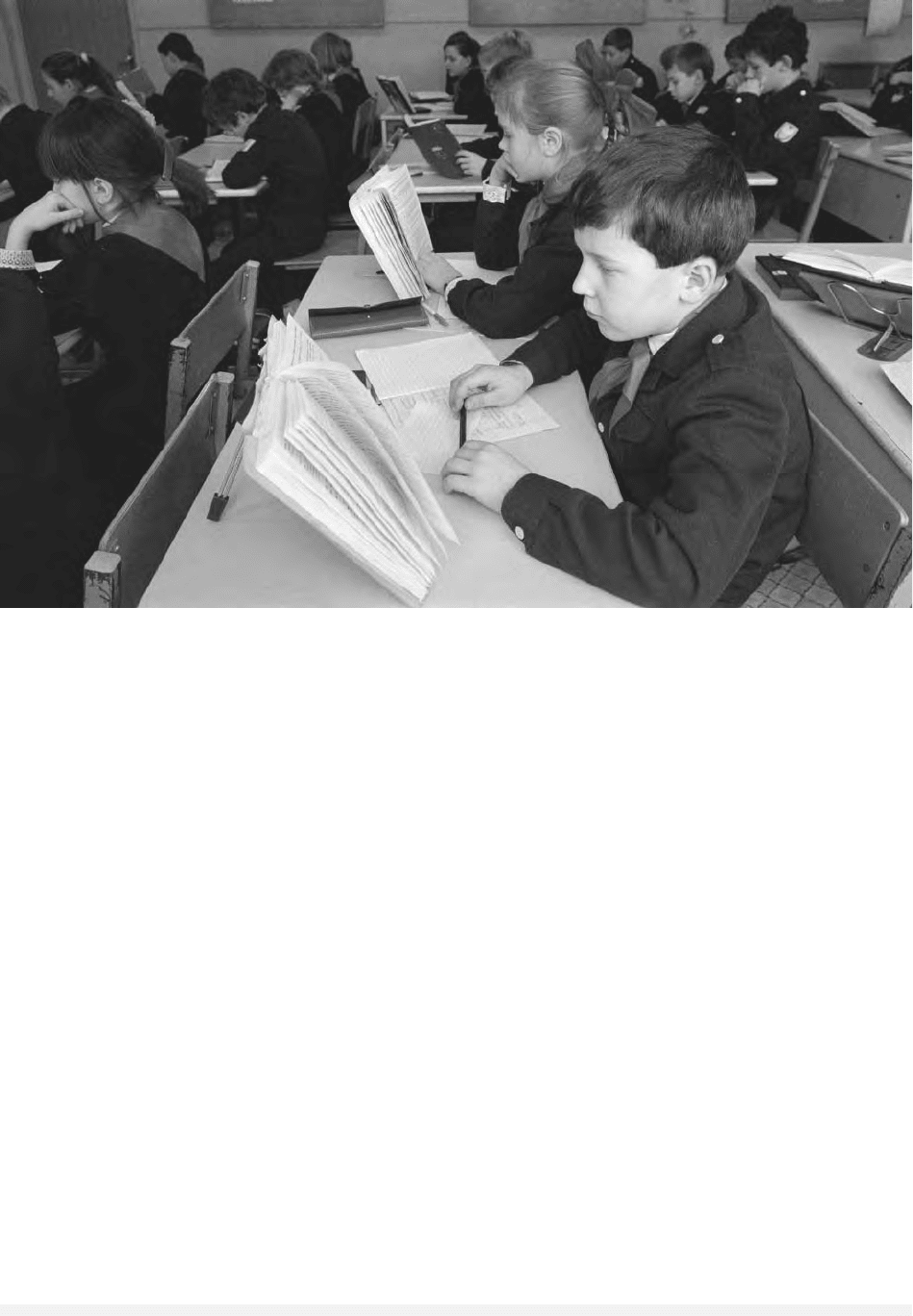

The Communist Party brought free education and mass literacy to the Soviet people. © D

AVID

T

URNLEY

/CORBIS

From Peter I onward, the Russian state devoted

a disproportionate amount of its educational

spending on higher education. This was partly due

to the pressing need for specialists, and partly be-

cause these institutions catered to social and eco-

nomic elites. Ambitious plans notwithstanding,

Russia developed a top-heavy educational system,

which produced a relatively small number of well-

educated individuals, but which failed to offer any

educational opportunities to most Russians until

the end of the nineteenth century. The number of

primary school students in Russia grew from

450,000 in 1856 to 1 million in 1878 to 6.6 mil-

lion in 1911; even then, there were still not enough

spaces for all who wanted to enroll.

Access to education was, as a rule, better in cities

and large towns than in rural areas, though it was

still limited in even the largest cities until the 1870s.

In 1911, 67 percent of urban youth aged eight to

eleven were enrolled in primary schools (75% of

boys, 59% of girls). In the countryside, the school

system developed more slowly. Many rural schools

opened before the 1870s were short-lived, and it

was only in the 1890s that a concerted effort be-

gan to establish an extensive network of permanent

rural schools. In 1911, 41 percent of rural children

aged eight to eleven were enrolled in primary school

(58% of boys, 24% of girls). Peasants in different ar-

eas had different attitudes about education, and

there has been some dispute about how useful lit-

eracy was considered by rural populations.

The better access to education in urban areas is

reflected in literacy statistics. The literacy rate

among the urban population (over age nine) was

roughly 21 percent in 1797 (29% of men, 12% of

women); 40 percent in 1847 (50% of men, 28% of

women); 58 percent in 1897; and 70 percent in

1917 (80% of men, 61% of women). In rural ar-

eas, the literacy rate was 6 percent in 1797 (6% of

men, 5% of women); 12 percent in 1847 (16% of

men, 9% of women); 26 percent in 1897; and 38

percent in 1917 (53% of men, 23% of women).

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ASPECTS OF

IMPERIAL EDUCATION POLICIES

While military and economic needs forced the Rus-

sian state to create an educational system, social

and political considerations also played a role in

shaping it. Tsars and their advisers carefully con-

sidered who should be educated, how long they

should study, and what they should be taught.

Above all, they were concerned about the educa-

tional policy’s impact on Russia’s political system

and social hierarchy, both of which they wanted

to preserve.

This was evident in the higher educational sys-

tem, which was shaped to a degree by the tsars’

desire to maintain social order and the nobility’s

support. Special institutes, such as the Corp of

Cadets (1731), were created exclusively for the sons

of hereditary nobles. While non-nobles were not

barred from higher education (with a few excep-

tions), the very nature of the Russian school sys-

tem made it difficult for such students to qualify

for advanced institutions. Escalating student fees at

gymnasia and universities in the nineteenth cen-

tury provided an additional barrier.

Just as the nobility’s position had to be de-

fended, the lower classes had to be protected from

“too much knowledge.” Nicholas I and his Educa-

tion Minister Sergei Uvarov (1831–1849) believed

that excessive education would only create dissat-

isfaction among the peasantry. Accordingly, they

placed strict limits on the curriculum and duration

of rural primary schools. But they also increased

the number of such schools, since they understood

that basic literacy was of social and economic value.

Uvarov, like many other Russian pedagogues, saw

education as an opportunity to instill in young

Russians loyalty to the tsar and proper moral val-

ues. A centrally controlled school inspectorate was

created to ensure that teachers were imparting the

right values to their students. All textbooks also re-

quired state approval.

Schools were used in other ways to maintain

or modify the social order. A separate school sys-

tem was created for Russia’s Jews, and strict lim-

its were placed on the number of Jewish students

admitted into higher educational institutions. In the

annexed Western provinces, schools were used as

a weapon in the aggressive Russification campaign

of the 1890s. And while most primary and sec-

ondary schools were coeducational, higher educa-

tional institutions were not. Separate women’s

institutes were only opened in 1876, and Russia’s

first coed university, the private Shaniavsky Uni-

versity, was established in 1908.

In order to prevent the circulation of subver-

sive ideas, the state placed strict limits on private

and philanthropic educational endeavors. In the

1830s all private educational institutions and tu-

tors were placed under state supervision. The ac-

tivities of volunteer movements trying to provide

adult education, such as the Sunday School Move-

EDUCATION

438

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ment (1859–1862), were severely constrained,

though zemstvos (local governmental bodies) were

later allowed more leeway in this area. Alarm over

the proliferation of unofficial (and illegal) peasant

schools helped motivate the state’s expansion of its

rural education system in the 1890s.

Ironically, it was the educated elite the state had

created that ultimately challenged the tsar’s au-

thority. Discontent became widespread in the 1840s,

as large segments of educated society came to see

state policies as retrograde and harmful to the peas-

antry. Frustrated by the conservative bureaucracy’s

disregard of their ideas, many educated Russians be-

gan to question the legitimacy of the autocratic

form of government, with a small number of them

becoming revolutionaries. This was one reason why

the tsarist government found itself with little sup-

port among educated Russians in February 1917.

EDUCATION

439

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Moscow State University—the Soviet Harvard—rises above the Lenin Hills. © P

AUL

A

LMASY

/CORBIS

Even as educated society was becoming es-

tranged from the autocracy, its members were

growing distant from the masses they wished to

help. As educated Russians adopted Western values

and ideas, a vast cultural and social divide devel-

oped between them and the mostly uneducated

peasantry, which largely retained traditional beliefs

and culture. The growth of the education system

in the last decades before 1917 was starting to

bridge this gap, but the inability of these groups to

understand one another contributed to the violence

and chaos of 1917. Scholars debate whether a more

rapid introduction of mass education into late Im-

perial Russia would have stabilized or further desta-

bilized the existing order.

EDUCATION IN THE SOVIET UNION

While the Bolsheviks shared their tsarist predeces-

sors’ belief in education’s potential social and po-

litical power, they had a different agenda: swift

industrialization, social change, and the dissemina-

tion of socialist values. Although they lacked an

educational policy upon seizing power, the Bolshe-

viks pledged to make education accessible to all, co-

educational at all levels, and to achieve full literacy.

The Russian Republic’s educational system was

placed under the control of the Russian Commis-

sariat of Enlightenment (Narodnyi kommisariat

prosveshcheniia, or Narkompros), a republic-level

institution created in October 1917. Its first leader

was Anatoly Lunacharsky (r. 1917–1929). Like all

Soviet institutions, Narkompros was controlled by

the Communist Party. Before 1920, however, it had

little authority. Many instructors had supported

the Provisional Government’s moderate reform

program, and they refused to cooperate with the

Bolsheviks. During the civil war (1918–1921), ed-

ucation was under the control of local authorities.

After 1920, Narkompros’ officials tried to im-

plement the ideas of progressive pedagogues, such

as John Dewey, in primary and secondary schools.

Their attempts were largely unsuccessful, ham-

pered by a lack of funds and teacher opposition.

Narkompros also faced challenges from the eco-

nomic commissariats, which eventually took con-

trol of vocational education. This was the first

round in a decades-long debate over the roles of

general and vocational education. Teachers were

frequently harassed by members of the Leninist

Youth League (Komsomol).

Bolshevik higher educational policies were even

more ambitious. Most members of educated soci-

ety did not support the communists. Bolshevik

leaders responded by creating a “red intelligentsia”

to replace them. The children of “socially alien”

groups were largely excluded from higher educa-

tion, their places taken by young, poorly educated

workers and peasants, known as vydvizhentsy. The

number of technical institutes was expanded to

accommodate the rapid growth of industry. A net-

work of communist higher educational institutions

was also opened. The influx of vydvizhentsy into

higher education, and the persecution of “socially

alien” teachers and students at all levels, climaxed

during the cultural revolution (1928–1932). It has

been argued that the vydvizhentsy, many of whom

rose to prominent positions, provided an important

base of support for Stalin’s regime.

After 1932, experimental approaches were

abandoned in favor of more practical teaching

methods. Primary schools were returned to a more

traditional curriculum, class-based preferences

ended, and the separate communist educational

system eliminated. The minimum duration of

schooling was raised from four to seven years.

Schools were now open to all students, though chil-

dren whose parents were arrested faced serious dis-

crimination until Stalin’s death in 1953. Most of

Narkompros’ functions were transferred to the new

Ministry of Education in 1946.

By the late 1950s, all children had access to a

free education. Social mobility was possible on the

basis of merit, although inequalities still existed.

Children of the emerging Soviet elites often had ac-

cess to superior secondary schools, which prepared

them for higher education. Members of some non-

Russian ethnic minorities had spaces reserved for

them at prestigious higher educational institutions,

as part of the Soviet Union’s unique affirmative ac-

tion program. After the 1950s, however, unofficial

quotas again limited Jewish students’ access to

higher education.

There were also numerous adult education pro-

grams in the Soviet Union. These ranged from

utopian attempts to train artists during the civil

war to ongoing literacy campaigns. Literacy rates

continued their steady rise after 1917 (88% in 1939,

and 98% in 1959). Adult education programs were

run by many groups, including the trade unions

and the Red Army.

Soviet schools were expected to teach students

loyalty to the state and instill them with socialist

values; teachers who did otherwise were liable to

arrest or dismissal. Political material was a con-

EDUCATION

440

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

stant part of Soviet curricula. In some periods, it

was restricted mainly to the social sciences and

obligatory study of Marxism-Leninism. During

Stalin’s rule, however, almost every subject was

politicized. Rote memorization was common and

student creativity discouraged.

Despite its flaws, the Soviet educational system

achieved some impressive successes. The heavily

subsidized system produced millions of well-

trained professionals and scientists in its last

decades. After 1984 the state began to loosen its

grip on education, allowing teachers some flexibil-

ity. These tentative steps were quickly overtaken

by events, however. Since 1991 the Russian school

system has faced serious funding problems and de-

clining facilities. Control of education has been

transferred to regional authorities.

See also: ACADEMY OF ARTS; ACADEMY OF SCIENCE;

HIGHER PARTY SCHOOL; LANGUAGE LAWS; LUNARCH-

SKY, ANATOLY VASILIEVICH; NATIONAL LIBRARY OF

RUSSIA; RUSSIAN STATE LIBRARY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Black, J. L. (1979). Citizens for the Fatherland: Education,

Educators, and Pedagogical Ideals in Eighteenth Cen-

tury Russia. Boulder, CO: East European Quarterly.

Brooks, Jeffrey. (1985). When Russia Learned to Read: Lit-

eracy and Popular Culture, 1861–1917. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

David-Fox, Michael. (1997). Revolution of the Mind: Higher

Learning Among the Bolsheviks, 1918–1929. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

Dunstan, John, ed. (1992). Soviet Education under Pere-

stroika. London: Routledge.

Eklof, Ben. (1986). Russian Peasant Schools: Officialdom,

Village Culture, and Popular Pedagogy, 1861–1914.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1979). Education and Social Mobility

in the Soviet Union, 1921–1934. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

Hans, Nicholas. (1964). History of Russian Educational

Policy, 1701–1917. New York: Russell & Russell, Inc.

Holmes, Larry E. (1991). The Kremlin and the Schoolhouse:

Reforming Education in Soviet Russia, 1917–1931.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Kassow, Samuel D. (1989). Students, Professors, and the

State in Tsarist Russia. Berkeley: University of Cali-

fornia Press.

Marker, Gary. (1990). “Literacy and Literacy Texts in

Muscovy: A Reconsideration.” Slavic Review 49(1):

74–84.

Matthews, Mervyn. (1982). Education in the Soviet Union:

Policies and Education Since Stalin. London: Allen &

Unwin.

McClelland, James C. (1979). Autocrats and Academics:

Education, Culture, and Society in Tsarist Russia.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mironov, Boris N. (1991). “The Development of Literacy

in Russia and the USSR from the Tenth to the Twen-

tieth Centuries.” History of Education Quarterly 31(2):

229–251.

Sinel, Allen. (1973). The Classroom and the Chancellery:

State Educational Reform in Russia under Count Dmitry

Tolstoi. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Webber, Stephen L. (2000). School, Reform, and Society in

the New Russia. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Whittaker, Cynthia H. (1984). The Origins of Modern Russ-

ian Education: An Intellectual Biography of Count Sergei

Uvarov. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

B

RIAN

K

ASSOF

EHRENBURG, ILYA GRIGOROVICH

(1891–1967), poet, journalist, novelist.

Ilya Grigorovich Ehrenburg was an enigma.

Essentially Western in taste, he was at times the

spokesman for the Soviet Union, the great anti-

Western power of his age. He involved himself with

Bolsheviks beginning in 1907, writing pamphlets

and doing some organizational work, and then, af-

ter his arrest, fled to Paris, where he would spend

most of the next thirty years. In the introduction

to his first major work, and probably his life’s best

work, the satirical novel Julio Jurentino (1922), his

good friend Nikolai Bukharin described Ehrenburg’s

liminal existence, saying that he was not a Bol-

shevik, but “a man of broad vision, with a deep in-

sight into the Western European way of life, a

sharp eye, and an acid tongue” (Goldberg, 1984, p.

5). These characteristics probably kept him alive

during the Josef Stalin years, along with his ser-

vice to the USSR as a war correspondent and

spokesman in the anticosmopolitan campaign. Ar-

guably, his most important service to the USSR

came in the period after Stalin’s death, when his

novel The Thaw (1956) deviated from the norms of

Socialist Realism. His activities in Writer’s Union

politics consistently pushed a kind of socialist lit-

erature (and life) “with a human face,” and his

memoirs, printed serially during the early 1960s,

were culled by thaw–generation youth for inspira-

tion. When Stalin was alive, Ehrenburg may well

EHRENBURG, ILYA GRIGOROVICH

441

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

have proven a coward. After his death, he proved

much more courageous than most.

See also: BUKHARIN, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH; JEWS; WORLD

WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goldberg, Anatol. (1984). Ilya Ehrenburg: Writing, Poli-

tics, and the Art of Survival. London: Weidenfeld and

Nicolson.

Johnson, Priscilla. (1965). Khrushchev and the Arts: The

Politics of Soviet Culture, 1962–1964. Cambridge, MA:

M.I.T. Press.

J

OHN

P

ATRICK

F

ARRELL

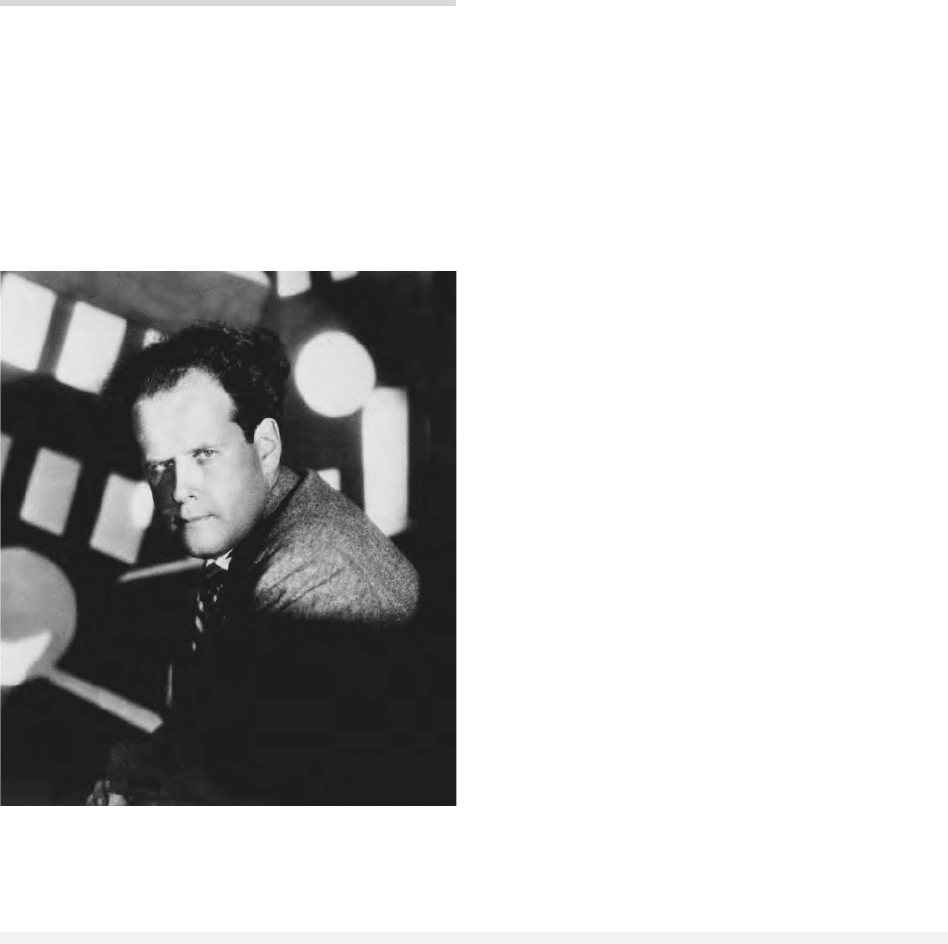

EISENSTEIN, SERGEI MIKHAILOVICH

(1898–1948), film director, film theorist, teacher,

arts administrator, and producer.

Sergei Eisenstein, born in Riga, was the most

accomplished of Russia’s first generation of Soviet

filmmakers. Eisenstein both benefited from the

communist system of state patronage and suffered

the frustrations and dangers all artists faced in

functioning under state control.

The October Revolution and the civil war al-

lowed Eisenstein to embark on a career in theater

and film. His first moving picture was Glumov’s Di-

ary, a short piece for a theatrical adaptation of an

Alexander Ostrovsky comedy. Between 1924 and

1929 he made four feature-length films on revo-

lutionary themes and with revolutionary cinematic

techniques: The Strike (1924), The Battleship Potemkin

(1926), October (1928), and The General Line (also

known as The Old and the New, 1929). In Potemkin

Eisenstein developed the rapid editing and dynamic

shot composition known as montage. Potemkin

made Eisenstein world-famous, but at the same

time he became embroiled in polemics with others

in the Soviet film community over the purpose of

cinema in “the building of socialism.” Eisenstein be-

lieved that film should educate rather than just

entertain, but he also believed that avant-garde

methods could be educational in socialist soc-

iety. This support for avant-garde experimentation

would be used against him during the far more

dangerous cultural politics of the 1930s. His last

two films of the 1920s, The General Line and Octo-

ber, were influenced by the increasing interference

of powerful political leaders. All of Eisenstein’s

Russian films were state commissions, but Eisen-

stein never joined the Communist Party, and he

continued to experiment even as he began to ac-

commodate himself to political reality.

From 1929 to 1932 Eisenstein traveled abroad

and had a stint in Hollywood. None of his three

projects for Paramount Pictures, however, was put

into production. The wealthy socialist writer Up-

ton Sinclair rescued him from the impasse by of-

fering to fund a film about Mexico, Qué Viva México!

Eisenstein thrived in Mexico, but Sinclair became

disgruntled when filming ran months over sched-

ule and rumors of sexual escapades reached him.

When Stalin threatened to banish Eisenstein per-

manently if he did not return to the Soviet Union,

Sinclair seized the opportunity to pull the plug on

Qué Viva México! Eisenstein never recovered the

year’s worth of footage and he was haunted by the

loss for the rest of his life.

The Moscow that Eisenstein found on his re-

turn in May 1932 was more constricted and im-

poverished than the city he had left. His polemics

of the 1920s were not forgotten, and Eisenstein was

criticized by party hacks and old friends alike for

being out of step and a formalist, which is to say

he cared more about experiments with cinematic

EISENSTEIN, SERGEI MIKHAILOVICH

442

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Acclaimed film director Sergei Eisenstein. A

RCHIVE

P

HOTOS

, I

NC

.

R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.