Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

form than with making films “accessible to the

masses.” Political attacks on the director culminated

in 1937, at the height of the Great Terror, as Eisen-

stein was nearing completion of Bezhin Meadow, his

first film since returning from abroad. Boris

Shumyatsky, chief of the Soviet film industry, had

the production halted; he proceeded to denounce

Eisenstein to the Central Committee and then di-

rectly to Stalin, inviting a death sentence on the

filmmaker. After barely surviving this attack, and

after ten years of blocked film projects, Eisenstein

wrote the required self-criticism and was given the

opportunity to make a historical film. Alexander

Nevsky, a medieval military encounter between

Russians and Germans, would become his most

popular film; however, Eisenstein was ashamed of

it, and except for its “battle on the ice,” it is gen-

erally considered to be his least interesting in tech-

nical and intellectual terms. The success of

Alexander Nevsky catapulted him to the highest of

inner circles; he won both the Order of Lenin and,

in 1941, the newly created Stalin Prize. Then, in a

restructuring of the film industry, Eisenstein was

made Artistic Director of Mosfilm, a prestigious

and powerful position.

In 1941, just months before World War II be-

gan in Russia, Eisenstein accepted a state commis-

sion to make a film about the sixteenth-century

tsar, Ivan the Terrible. He worked on Ivan the Ter-

rible for the next six years, eventually completing

only two parts of the planned trilogy. Eisenstein’s

masterpiece, Ivan the Terrible is a complex film con-

taining a number of coordinated and conflicting

narratives and networks of imagery that portray

Ivan as a great leader, historically destined to found

the Russian state but personally doomed by the

murderous means he had used. Part I (1945) re-

ceived a Stalin Prize, Part II (1946, released 1958)

did not please Stalin and was banned.

Eisenstein was one of few practicing film di-

rectors to develop an important body of theoreti-

cal writing about cinema. In the 1920s he wrote

about the psychological effect of montage on the

viewer; the technique was intended to both startle

the viewer into an awareness of the constructed na-

ture of the work and to shape the viewing experi-

ence. During the 1930s, when he was barred from

filmmaking, Eisenstein wrote and taught. A gifted

teacher, he relied on his wide reading and sense of

humor to draw students into the creative process.

Work on Ivan the Terrible in the 1940s stimulated

his most productive period of writing. He produced

several volumes of theoretical works in Method and

Nonindifferent Nature, as well as a large volume of

memoirs. This work developed his earlier concept

of montage by broadening its scope to include

sound and color as well as imagery within the shot.

By nature Eisenstein was a private and cau-

tious man. He could be charming and charismatic

as well as serious and demanding, but these were

public masks; he guarded his private life. It seems

clear that he had sexual relationships with both

men and women but also that these affairs were

rare and short-lived; he consulted with psychoan-

alysts on several occasions about his bisexuality in

the 1920s and 1930s. In 1934, just after a law was

passed making male homosexuality illegal in the

Soviet Union, Eisenstein married his good friend

and assistant, Pera Atasheva. It is fair to say that

Eisenstein’s sexuality was a source of some dissat-

isfaction for him and that his private life in gen-

eral brought him considerable pain. He suffered

from periodic bouts of serious depression and from

the 1930s onward his health was also threatened

by heart disease and influenza.

Eisenstein suffered a serious heart attack just

hours after finishing Part II of Ivan the Terrible. He

never recovered the strength to return to film pro-

duction, but he wrote extensively until the night

of February 11, 1948, when he suffered a fatal heart

attack.

See also: CENSORSHIP; MOTION PICTURES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bordwell, David. (1994). The Cinema of Eisenstein. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bulgakowa, Oksana. (2001). Sergei Eisenstein: A Biogra-

phy. San Francisco: PotemkinPress.

Neuberger, Joan. (2003). Ivan the Terrible: The Film Com-

panion. London: I. B. Tauris.

Taylor, Richard. (2002). The Battleship Potemkin: The Film

Companion. London: I. B. Tauris.

Taylor, Richard. (2002). October. London: British Film In-

stitute.

J

OAN

N

EUBERGER

ELECTORAL COMMISSION

Electoral commissions play a large role in the or-

ganization and holding of elections under Russia’s

so-called guided democracy. They exist at four fun-

damental levels: precincts (approximately 95,000),

ELECTORAL COMMISSION

443

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

territorial (TIK, 2,700), regional (RIK), and central

(TsIK). There are also municipal commissions in

some of the large cities, and there are district com-

missions for elections to the State Duma (around

190 to 225 districts according to Duma elections,

minus those falling on a region’s borders).

The central, regional, and territorial commis-

sions are permanent bodies with four-year terms.

The district and precinct commissions are organized

one to three months before elections, and curtail

their activity ten days after the publication of re-

sults.

The electoral commissions have from three to

fifteen voting members, at least half of whom are

appointed based on nominations by electoral asso-

ciations with fractions in the Duma and by the re-

gional legislatures. Half of the members of the

regional electoral commissions are appointed by the

regional executive, the other half by the legislative

assembly. This means that for all practical matters

the electoral commissions are under the control of

the executive power. Parties, blocs, and candidates

participating in elections may appoint one member

of the electoral commission with consultative

rights in the commission at their level and the

levels below them. The precinct and territorial com-

missions are organized by the regional commis-

sions with the participation of local government.

A new form of central electoral commission

arose in 1993, when it was necessary to hold par-

liamentary elections and vote on a constitution in

a short time. Officials considered the election dead-

lines unrealistic. At that time the president named

all members of the commission and its chair. The

central electoral commission has fifteen members

and is organized on an equal footing by the Duma,

the Federation Council, and the president. The cen-

tral commission is essentially a Soviet institution,

with the actual power, including control over the

numerous apparatuses, concentrated in the hands

of the chair. Between 2001 and 2003, an electoral

vertical was established whereby the central com-

mission can directly influence the lower-level com-

missions. The central commission names at least

two members of the regional commission and nom-

inates candidates for its head. Moreover, in the fu-

ture the regional electoral commissions may be

disbanded in favor of central commission represen-

tation (this mechanism was tested in 2003 with the

Krasnoyarsk Krai electoral commission). The role of

the central commission, and also of the Kremlin, in

regional and local elections has grown significantly.

The central commission’s authority to interpret am-

biguous legal clauses enables it to punish and par-

don candidates, parties, electoral associations, and

mass media organizations. As a bureaucratic struc-

ture, the central electoral commission has turned

into a highly influential election ministry with an

enormous budget and powerful leverage in relation

to other federal and regional power structures and

the entire political life of the country.

See also: DUMA; PRESIDENCY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

McFaul, Michael. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution:

Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Ithaca, NY:

Cornell University Press.

McFaul, Michael, and Markov, Sergi. (1993). The Trou-

bled Birth of Russian Democracy: Parties, Personalities,

and Programs. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution

Press.

McFaul, Michael; Petrov, Nikolai; and Ryabov, Andrei,

eds. (1999). Primer on Russia’s 1999 Duma Elections.

Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for Interna-

tional Peace.

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). The Tragedy

of Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism against Democ-

racy. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

N

IKOLAI

P

ETROV

ELECTRICITY GRID

In 1920, Lenin famously said, “Communism equals

Soviet power plus electrification of the whole coun-

try.” He created the State Commission for Electri-

fication of Russia (GOELRO) to achieve this, and the

expansion of electricity generation and transmis-

sion became a core element in Soviet moderniza-

tion. Total output rose from 8.4 billion kilowatt

hours in 1930, to 49 billion in 1940 and 290 bil-

lion in 1960. After World War II the Soviet Union

became the second largest electricity generator in

the world, with the United States occupying first

place. The soviets built the world’s largest hydro-

electric plant, in Krasnoyarsk in 1954, and the

world’s first nuclear power reactor, in Obninsk.

Electrification had reached 80 percent of all vil-

lages by the 1960s, and half of the rail track was

electrified. Power stations also provided steam heat-

ing for neighboring districts, accounting for one-

third of the nation’s heating. This may have been

efficient from the power-generation point of view,

but there was no effort to meter customers or

ELECTRICITY GRID

444

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

conserve energy. By 1960 the Soviet Union had

167,000 kilometers of high transmission lines (35

kilovolts and higher). This grew to 600,000 kilo-

meters by 1975. Initially, there were ten regional

grids, which by the 1970s were gradually com-

bined into a unified national grid that handled 75

percent of total electricity output. In 1976 the So-

viet grid was connected to that of East Europe (the

members of Comecon).

The Soviet power supply continued to expand

steadily, even as economic growth slowed. Output

increased from 741 billion kilowatt hours in 1970

to 1,728 billion in 1990, with the USSR account-

ing for 17 percent of global electricity output. Still,

capacity failed to keep pace with the gargantuan

appetites of Soviet industry, and regional coverage

was uneven, since most of the fossil fuels were lo-

cated in the north and east, whereas the major pop-

ulation centers and industry were in the west.

Twenty percent of the energy was consumed in

transporting the coal, gas, and fuel-oil to thermal

power stations located near industrial zones. In the

early 1970s, when nuclear plants accounted for

just two percent of total electricity output, the gov-

ernment launched an ambitious program to expand

nuclear power. This plan was halted for more than

a decade by the 1986 Chernobyl accident. In 1990

the Russia Federation generated 1,082 billion kilo-

watt hours, a figure that had fallen to 835 billion

by 2000. Of that total, 15 percent was from nu-

clear plants and 18 percent from hydro stations,

the rest was from thermal plants using half coal

and half natural gas for fuel.

In 1992 the electricity system was turned into

a joint stock company, the Unified Energy Systems

of Russia (RAO EES). Blocks of shares in RAO EES

were sold to its workers and the public for vouch-

ers in 1994, and subsequently were sold to do-

mestic and foreign investors, but the government

held onto a controlling 53 percent stake in EES.

Some regional producers were separated from EES,

but the latter still accounted for 73 percent of Russ-

ian generating capacity and 85 percent of electric-

ity distribution in 2000.

Electricity prices were held down by the gov-

ernment in order to subsidize industrial and do-

mestic consumers. This meant most of the regional

energy companies that made up EES ran at a loss,

and could not invest in new capacity or energy con-

servation. By 1999, the situation was critical: EES

was losing $1 billion on annual revenues of $7 bil-

lion. Former privatization chief Anatoly Chubais

was appointed head of EES, and he proposed pri-

vatizing some of EES’s more lucrative regional pro-

ducers to the highest bidder. The remaining oper-

ations would be restructured into five to seven

generation companies, which would be spun off as

independent companies. A wholesale market in elec-

tricity would be introduced, and retail prices would

be allowed to rise by 100 percent by 2005. The grid

and dispatcher service would be returned to state

ownership. Amid objections from consumers, who

objected to higher prices, and from foreign in-

vestors in EES, who feared their shares would be

diluted, the plan was adopted in 2002.

See also: CHERNOBYL; CHUBAIS, ANATOLY BORISOVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ebel, Robert. (1994). Energy Choices in Russia. Washing-

ton, DC: Center for Strategic and International Stud-

ies.

EES web site: <http://www.rao-ees.ru/en>.

P

ETER

R

UTLAND

ELIZABETH

(1709–1762), empress of Russia, 1741–1762, one

of the “Russian matriarchate” or “Amazon auto-

cratrixes,” that is, women rulers from Catherine I

through Catherine II, 1725–1796.

Daughter of Peter I and Catherine I, grand

princess and crown princess from 1709 to 1741,

Elizabeth (Elizaveta Petrovna) was the second of ten

offspring to reach maturity. She was born in the

Moscow suburb of Kolomenskoye on December 29,

1709, the same day a Moscow parade celebrated

the Poltava victory. Elizabeth grew up carefree with

her sister Anna (1708–1728). Doted on by both par-

ents, the girls received training in European lan-

guages, social skills, and Russian traditions of

singing, religious instruction, and dancing. Anna

married Duke Karl Friedrich of Holstein-Gottorp in

1727 and died in Holstein giving birth to Karl Pe-

ter Ulrich (the future Peter III). Elizabeth never mar-

ried officially or traveled abroad, her illegitimate

birth obstructing royal matches. Because she wrote

little and left no diary, her inner thoughts are not

well-known.

Hints of a political role came after her mother’s

short reign when Elizabeth was named to the joint

regency for young Peter II, whose favor she briefly

enjoyed. But when he died childless in 1730 she

ELIZABETH

445

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

was overlooked in the surprise selection of Anna

Ivanovna. Under Anna she was kept under sur-

veillance, her yearly allowance cut to 30,000

rubles, and only Biron’s influence prevented com-

mitment to a convent. At Aleksandrovka near

Moscow she indulged in amorous relationships

with Alexander Buturlin, Alexei Shubin, and the

Ukrainian chorister Alexei Razumovsky. During

Elizabeth’s reign male favoritism flourished; some

of her preferred men assumed broad cultural

and artistic functions—for instance, Ivan Shuvalov

(1717–1797), a well-read Francophile who co-

founded Moscow University and the Imperial Rus-

sian Academy of Fine Arts in the 1750s.

Anna Ivanovna was succeeded in October 1740

by infant Ivan VI of the Brunswick branch of

Romanovs who reigned under several fragile

regencies, the last headed by his mother, Anna

Leopoldovna (1718–1746). This Anna represented

the Miloslavsky/Brunswick branch, whereas Eliz-

abeth personified the Naryshkin/Petrine branch.

Elizabeth naturally worried the inept regency

regime, which she led her partisans in the guards

to overthrow on December 5–6, 1741, with aid

from the French and Swedish ambassadors (Swe-

den had declared war on Russia in July 1741 os-

tensibly in support of Elizabeth). The bloodless

coup was deftly accomplished, the regent and her

family arrested and banished, and Elizabeth’s

claims explicated on the basis of legitimacy and

blood kinship. Though Elizabeth’s accession un-

leashed public condemnation of both Annas as

agents of foreign domination, it also reaffirmed the

primacy of Petrine traditions and conquests,

promising to restore Petrine glory and to counter

Swedish invasion, which brought Russian gains in

Finland by the Peace of Åbo in August 1743.

Elizabeth was crowned in Moscow in spring

1742 amid huge celebrations spanning several

months; she demonstratively crowned herself.

With Petrine, classical feminine, and “restora-

tionist” rhetoric, Elizabeth’s regime resembled Anna

Ivanovna’s in that it pursued an active foreign pol-

icy, witnessed complicated court rivalries and fur-

ther attempts to resolve the succession issue, and

made the imperial court a center of European cul-

tural activities. In 1742 the empress, lacking off-

spring, brought her nephew from Holstein to be

converted to Orthodoxy, renamed, and designated

crown prince Peter Fyodorovich. In 1744 she found

him a German bride, Sophia of Anhalt-Zerbst, the

future Catherine II. The teenage consorts married

in August 1745, and hopes for a male heir came

true only in 1754. Elizabeth took charge of Grand

Prince Pavel Petrovich. Nevertheless, the “Young

Court” rivaled Elizabeth’s in competition over dy-

nastic and succession concerns.

While retaining ultimate authority, Elizabeth

restored the primacy of the Senate in policymak-

ing, exercised a consultative style of administra-

tion, and assembled a government comprising

veteran statesmen, such as cosmopolitan Chancel-

lor Alexei Bestuzhev-Ryumin and newly elevated

aristocrats like the brothers Petr and Alexander

Shuvalov (and their younger cousin Ivan Shu-

valov), Mikhail and Roman Vorontsov, Alexei and

Kirill Razumovsky, and court surgeon Armand

Lestocq. Her reign generally avoided political re-

pression, but she took revenge on the Lopukhin

family, descendents of Peter I’s first wife, by hav-

ELIZABETH

446

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Portrait of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna by Pierre Duflos.

© S

TAPLETON

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

ing them tortured and exiled in 1743 for loose talk

about the Brunswick family and its superior rights.

Later she abolished the death penalty in practice.

Lestocq and Bestuzhev-Ryumin, who was suc-

ceeded as chancellor by Mikhail Vorontsov, fell into

disgrace for alleged intrigues, although Catherine II

later pardoned both.

In cultural policy Elizabeth patronized many,

including Mikhail Lomonosov, Alexander Sumaro-

kov, Vasily Tredyakovsky, and the Volkov broth-

ers, all active in literature and the arts. Foreign

architects, composers, and literary figures such as

Bartolomeo Rastrelli, Francesco Araja, and Jakob

von Stählin also enjoyed Elizabeth’s support. Her

love of pageantry resulted in Petersburg’s first pro-

fessional public theater in 1756. Indeed, the em-

press set a personal example by frequently at-

tending the theater, and her court became famous

for elaborate festivities amid luxurious settings,

such as Rastrelli’s new Winter Palace and the

Catherine Palace at Tsarskoye Selo. Elizabeth loved

fancy dress and followed European fashion, al-

though she was criticized by Grand Princess

Catherine for quixotic transvestite balls and crudely

dictating other ladies’style and attire. Other covert

critics such as Prince Mikhail Shcherbatov accused

Elizabeth of accelerating the “corruption of man-

ners” by pandering to a culture of corrupt excess,

an inevitable accusation from disgruntled aristo-

crats amid the costly ongoing Europeanization of

a cosmopolitan high society. The Shuvalov broth-

ers introduced significant innovations in financial

policy that fueled economic and fiscal growth and

reinstituted recodification of law.

Elizabeth followed Petrine precedent in foreign

policy, a field she took special interest in, although

critics alleged her geographical ignorance and lazi-

ness. Without firing a shot, Russia helped conclude

the war of the Austrian succession (1740–1748),

but during this conflict Elizabeth and Chancellor

Bestuzhev-Ryumin became convinced that Pruss-

ian aggression threatened Russia’s security. Hence

alliance with Austria became the fulcrum of Eliza-

bethan foreign policy, inevitably entangling Russia

in the reversal of alliances in 1756 that exploded in

the worldwide Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). This

complex conflict pitted Russia, Austria, and France

against Prussia and Britain, but Russia did not fight

longtime trading partner Britain. Russia held its

own against Prussia, conquered East Prussia, and

even briefly occupied Berlin in 1760. The war was

directed by a new institution, the Conference at the

Imperial Court, for Elizabeth’s declining health lim-

ited her personal attention to state affairs. The war

dragged on too long, and the belligerents began

looking for a way out when Elizabeth’s sudden

death on Christmas Day (December 25, 1761)

brought her nephew Peter III to power. He was de-

termined to break ranks and to ally with Prussia,

despite Elizabeth’s antagonism to King Frederick II.

So just as Elizabeth’s reign started with a perversely

declared war, so it ended abruptly with Russia’s

early withdrawal from a European-wide conflict

and Peter III’s declaration of war on longtime

ally Denmark. Elizabeth personified Russia’s post-

Petrine eminence and further emergence as a

European power with aspirations for cultural

achievement.

See also: ANNA IVANOVNA; BESTUZHEV-RYUMIN, ALEXEI

PETROVICH; PETER I; SEVEN YEARS’ WAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, John T. (1989). Catherine the Great: Life and

Legend. New York: Oxford University Press.

Anisimov, Evgeny. (1995). Empress Elizabeth: Her Reign

and Her Russia, ed. and tr. John T. Alexander. Gulf

Breeze, FL: Academic International.

Hughes, Lindsey. (2002). Peter the Great: A Biography.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Naumov, Viktor Petrovich. (1996). “Empress Elizabeth I,

1741–1762.” In The Emperors and Empresses of Rus-

sia: Rediscovering the Romanovs, ed. and comp. Don-

ald J. Raleigh and A. A. Iskenderov. Armonk, NY:

M. E. Sharpe.

Shcherbatov, M. M. (1969). On the Corruption of Morals

in Russia, ed. and tr. Anthony Lentin. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wortman, Richard. (1995). Scenarios of Power: Myth and

Ceremony in Russian Monarchy, vol. 1. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

J

OHN

T. A

LEXANDER

EMANCIPATION ACT

The Emancipation Act was issued by the Russian

Emperor Alexander II on March 3, 1861. By this

act all peasants, or serfs, were set free from per-

sonal dependence on their landlords, acquired civil

rights, and were granted participation in social and

economic activities as free citizens.

EMANCIPATION ACT

447

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The importance of emancipation cannot be

overestimated. However, emancipation can be un-

derstood only by taking into consideration the his-

tory of serfdom in Russia. If in early modern

Europe different institutions successfully emerged

to represent the interests of different classes (e.g.,

universities, guilds, and corporations) against the

state’s absolutist tendencies, in Russia the state won

over its competitors and took the form of autoc-

racy. Despite the absolutist state’s takeover in early

modern Europe, it never encroached on the indi-

vidual rights of its subjects to the extent that the

Russian autocracy did. Indeed, autocracy presup-

posed that no right existed until it was granted and

thus all subjects were slaves until the tsar decided

otherwise.

As the process of state centralization proceeded

in Russia, external sources of income (for instance,

wars and territorial growth) were more or less ex-

hausted by the seventeenth century, and the state

switched its attention to its internal resources.

Hence the continuous attempts to immobilize peas-

ants and make them easily accessible as taxpayers.

The Law Code of 1649 completed the process of im-

mobilization declaring “eternal and hereditary at-

tachment” of peasants to the land. Thus the Russian

term for “serf” goes back to this attachment to the

land more than to personal dependence on the mas-

ter. Later in the eighteenth century it became pos-

sible to sell serfs without the land. Afterwards the

only difference between the serf and the slave was

that the serf had a household on the land of his

master.

At the time of emancipation, serfdom consti-

tuted the core of Russian economic and social life.

Its abolition undermined the basis of the autocratic

state in the eyes of the vast majority of nobles as

well as peasants. Those few in favor of the reform

were not numerous: landlords running modernized

enterprises and hindered by the absence of a free

labor force and competition, together with liberal

and radical thinkers (often landless). For peasants,

the interpretation of emancipation ranged from a

call for total anarchy, arbitrary redistribution of

land, and revenge on their masters, to disbelief and

disregard of the emancipation as impossible.

Thus Alexander II had to strike a balance be-

tween contradictory interests of different groups of

nobility and the threat of peasant riots. The text of

the act makes this balancing visible. The emperor

openly acknowledged the inequality among his

subjects and said that traditional relations between

the nobility and the peasantry based on the “benev-

olence of the noblemen” and “affectionate submis-

sion on the part of the peasants” had become

degraded. Under these circumstances, acting as a

promoter of the good of all his subjects, Alexander

II made an effort to introduce a “new organization

of peasant life.”

To pay homage to the class of his main sup-

porters, in the document Alexander stresses the de-

votion and goodwill of his nobility, their readiness

“to make sacrifices for the welfare of the country,”

and his hope for their future cooperation. In return

he promises to help them in the form of loans and

transfer of debts. On the other hand, serfs should

be warned and reminded of their obligations to-

ward those in power. “Some were concerned about

the freedom and unconcerned about obligations”

reads the document. The Emperor cites the Bible

that “every individual is subject to a higher au-

thority” and concludes that “what legally belongs

to nobles cannot be taken from them without ad-

equate compensation,” or punishment will surely

follow.

The state initiative for emancipation indicates

that the state planned to be the first to benefit from

it. Though several of Alexander’s predecessors

touched upon the question of peasant reform, none

of them was in such a desperate situation domes-

tically or internationally as to pursue unprece-

dented measures and push the reform ahead. The

Crimean War (1853–1856) became the point of

revelation because Russia faced the threat not only

of financial collapse but of losing its position as a

great power among European countries. The re-

form should have become a source of economic and

military mobilization and thus kept the state equal

among equals in Europe as well as eliminate the

remnants of postwar chaos in its social life. How-

ever, the emancipation changed the structure of

society in a way that demanded its total recon-

struction. A series of liberal reforms followed, and

the question of whether the Emperor ever planned

to go that far remains open for historians.

The emancipation meant that all peasants be-

came “free rural inhabitants” with full rights. The

nobles retained their property rights on land while

granting the peasants “perpetual use of their domi-

cile in return of specified obligations,” that is, peas-

ants should work for their landlords as they used

to work before. These temporal arrangements

would last for two years, during which redemp-

tion fees for land would be paid and the peasant

EMANCIPATION ACT

448

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

would become an owner of his plot. In general the

Emancipation Act was followed by Regulations on

Peasants Set Free in seventeen articles that explained

the procedure of land redistribution and new or-

ganization of peasant life in detail.

Because peasants became free citizens, emanci-

pation had far-reaching economic consequences.

The organization of rural life changed when the

peasant community—not the landlord—was re-

sponsible for taxation and administrative and po-

lice order. The community became a self-governing

entity when rural property-holders were able to

elect their representatives for participation in ad-

ministrative bodies at the higher level as well as for

the local court. To resolve conflicts arising between

the nobles and the peasants, community justices

were introduced locally, and special officials medi-

ated these conflicts.

Emancipation destroyed class boundaries and

opened the way for further development of capi-

talist relations and a market economy. Those who

were not able to pay the redemption fee and buy

their land entered the market as a free labor force

promoting further industrialization. Moreover, it

had a great psychological impact on the general

public, because, in principle at least, there remained

no underprivileged classes, and formal civil equal-

ity was established. A new generation was to fol-

low—not slaves but citizens.

See also: ALEXANDER II; LAW CODE OF 1649; PEASANTRY;

SERFDOM; SLAVERY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“The Emancipation Manifesto, March 3 1861.” (2003).

<http://www.dur.ac.uk/~dml0www/emancipn

.html>

Emmons, Terrence. (1968). The Russian Landed Gentry

and the Peasant Emancipation of 1861. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press..

Emmons Terrence, ed. (1970). Emancipation of the Russ-

ian Serfs. New York: International Thomson Pub-

lishing.

Field, Daniel. (1976). The End of Serfdom: Nobility and Bu-

reaucracy in Russia, 1855–1861. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Hellie, Richard. (1982). Slavery in Russia, 1450–1725.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Seton-Watson, Hugh. (1967). The Russian Empire,

1801–1917. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

J

ULIA

U

LYANNIKOVA

EMPIRE, USSR AS

The understanding of the concept of empire depends

on time and space. During the nineteenth century

the terms empire and imperialism were associated

with the spread of progress by countries claiming

to represent civilized forms of existence. By the end

of World War II the emergent superpowers, the

United States and the USSR, adhered to an anti-

imperialist, anti-empire ideology and thereby ended

the colonial empires of countries such as Britain

and France.

According to Leninist thought, empire and im-

perialism represented the highest and last stages of

capitalist development after which socialism would

emerge. Therefore the Soviet leadership never con-

sidered the multinational USSR, the leader of so-

cialist revolution, to be an empire. This Leninist

ideological definition of empire, while providing a

framework for comprehending the Soviet leader-

ship’s approach to governing, fails to describe the

dynamics of the USSR as an empire. As shown by

Dominic Lieven (2000), a country must fulfill sev-

eral criteria to be considered an empire. It must be

continental in scale, governing a range of different

peoples, represent a great culture or ideology with

more than local hegemony, exercise great economic

and military might on more than a regional level,

and arguably govern without the consent of the

people. According to these criteria the USSR was

indeed an empire, however not without certain

characteristics distinguishing it from other empires,

such as the British, Ottoman, or Hapsburg.

The USSR was the world’s largest country, ex-

tending from Europe in the west to China and the

Pacific in the east, its southern borders touching

the boundaries of the Middle East. Given this geo-

graphic position, Moscow was a player in three of

the world’s most important regions. The Soviet

Union’s population consisted of hundreds of dif-

ferent peoples speaking a myriad of languages and

practicing different religions, including Judaism,

Orthodoxy, Catholicism, Protestantism, and Sunni

and Shia Islam. Such diversity was reminiscent of

the great British and French maritime empires.

Josef Stalin’s brutal industrialization policies

and victory in World War II paved the way for the

Soviet Union’s emergence as a superpower with

global reach and influence. The Soviet economy

was the second largest in the world despite its many

deficiencies and supported a huge military indus-

trial complex, which by the 1960s had enabled the

EMPIRE, USSR AS

449

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

USSR to attain nuclear parity with the United

States while maintaining the largest armed forces

in the world.

Ideological power accompanied this military

and economic might. The Cold War between the

USSR and the United States was rooted in alterna-

tive visions of modernity. Whereas the United States

held that liberal democracy and capitalism ulti-

mately represented the end of history, the Soviet

Union believed that an additional stage, that of com-

munism, represented the true end of history. Many

across the globe found Soviet communism’s claims

of representing a truly egalitarian and therefore

more humane society attractive. In other words, the

ideological and cultural power of the USSR exercised

global influence.

In the midst of war and revolution many ar-

eas of the former tsarist empire became indepen-

dent. With the exception of Finland, Estonia,

Lithuania, Latvia, and parts of Poland, the Bolshe-

viks, through the effective and brutal use of force

and coercion and under the banner of progressive

Soviet communism, resurrected the empire they

once called “Prison of the Peoples.” In 1940 Stalin

invaded and occupied the Baltic States, which sub-

sequently, according to Soviet propaganda, volun-

tarily became part of the USSR. Until the late 1980s

during the reform process of Mikhail Gorbachev,

the Soviet leadership governed without the direct

consent of the people.

LAND-BASED EMPIRE

The Soviet Union was a land-based empire encom-

passing all the territories of its tsarist predecessor—

except Poland and Finland—while adding other ar-

eas such as western Ukraine and Bessarabia. The

dynamics of a land-based empire differ greatly

from those of maritime empires, such as the British

and French. Before embarking on maritime empire

building, countries such as Britain, France, and

Spain already had a relatively solidified national

identity. In tsarist Russia, empire and nation build-

ing commenced at roughly the same time, thereby

blurring empire and nation. To determine where

Russia the nation ended and where the empire be-

gan was difficult. This theme would continue in

the Soviet era.

Given the geographical distance between the

metropole and its maritime empire, a clear division

remained between colonized, most of whom were

of different races and cultures, and colonizer, and

therefore the question of assimilation of different

peoples under a single supranational ideology or

symbol never arose. The metropolitan British iden-

tity was neither created nor adjusted to include the

peoples of the vast empire ruled by London. In

tsarist Russia the emperor and the crown repre-

sented the supranational entity to which the vari-

ous peoples of the empire were to pledge their

loyalty. Here, terminology is important. Two words

for the English equivalent of “Russian” exist. When

discussing anything related to Russian ethnicity,

such as a person or the language, the word russky

is used. However the empire, its institutions and

the dynasty, were called rossysky, which carried a

civil meaning designed to include everyone from

Baltic German to Tatar. The emperor himself was

known not as the “russky” tsar, but vserossysky

(All-Russian).

The Soviet leadership faced the same problems

of governing and assimilation associated with a

multiethnic land empire. While Soviet nationality

policy, in other words how Soviet leaders ap-

proached governing this large and diverse empire,

varied over time, its goals never did. They were (a)

to maintain the country’s territorial integrity and

domestic security; (b) to support the monopolistic

hold on power of the Communist Party of the So-

viet Union (CPSU); and (c) create a supranational

Soviet identity, reminiscent of the civil rossysky.

On one hand the Soviet leadership in line with

Marxist–Leninist thought believed that national-

ism, the death knell for any multinational empire,

was a phenomenon inherent to capitalism and the

bourgeois classes. Therefore, with the advent of so-

cialism, broadly defined working class interests

would triumph over national loyalties. In short,

socialism makes nationalism redundant. On the

other hand, the reality of governing a multiethnic

empire required the Soviet leadership to pursue sev-

eral policies reminiscent of a traditional imperial

polity, such as deportations of whole peoples, play-

ing one ethnic group against another, and draw-

ing boundaries designed to maintain the supremacy

of the central power.

Unlike previous empires, the USSR was a fed-

eration that had fifteen republics at the time of its

dissolution in 1991. Confident in the relatively

speedy victory of socialism and communism over

capitalism, in the 1920s the Soviet leadership fol-

lowed a very accommodating policy in regard to

nationalities. Along with the creation of a federa-

tion that institutionalized national identities, the

new Soviet authorities supported the spread and

strengthening of non-Russian cultures, languages,

EMPIRE, USSR AS

450

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and identities. In areas where a national identity al-

ready existed, such as Ukraine, Georgia, and Ar-

menia, great ethnic cultural autonomy was

allowed. In areas where no national identity yet ex-

isted, as in Central Asia, Soviet ethnographers

worked to create peoples and national borders,

based on cultural and economic considerations. The

Soviet drawing of borders is comparable to the cre-

ation of states by European imperial powers in

Africa and the Middle East. Each created republic

had identical state, bureaucratic, and educational

structures, an Academy of Sciences, and other in-

stitutions whose responsibility was the mainte-

nance and strengthening of the national identity as

well as propagation of Marxist–Leninist teachings.

Therefore the Soviet Union supported and gave

birth to national identities, whereas other land-

based empires, such as the Ottoman and Habsburg,

fought against them. At the same time the central

Soviet authorities recruited indigenous people in the

non-Russian republics to serve in local, republican,

and even all-union institutions.

Alongside nation building went social and eco-

nomic modernization, and a requirement for the

emergence of socialism, which would bring an end

to strong national feelings. Unlike French and

British colonial rule, the Soviets made dramatic

changes of the societies and peoples of the USSR—

one of the main thrusts of their nationality policy.

While Central Asia and the Caucasus were the most

economically and socially “backward,” through

rapid industrialization and collectivization of peas-

ant land all societies of the USSR endured dramatic

change, surpassing the extent to which France and

Britain had affected their colonial possessions. Im-

portantly, the Soviets strove to modernize Russia,

which many regarded to be the imperial power.

There is no such analogy in regard to the maritime

European empires, whose metropole was consid-

ered to be at the forefront of modernization and

civilization.

The rule of Josef Stalin brought changes to this

policy. Regarding cultural autonomy a threat to the

EMPIRE, USSR AS

451

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

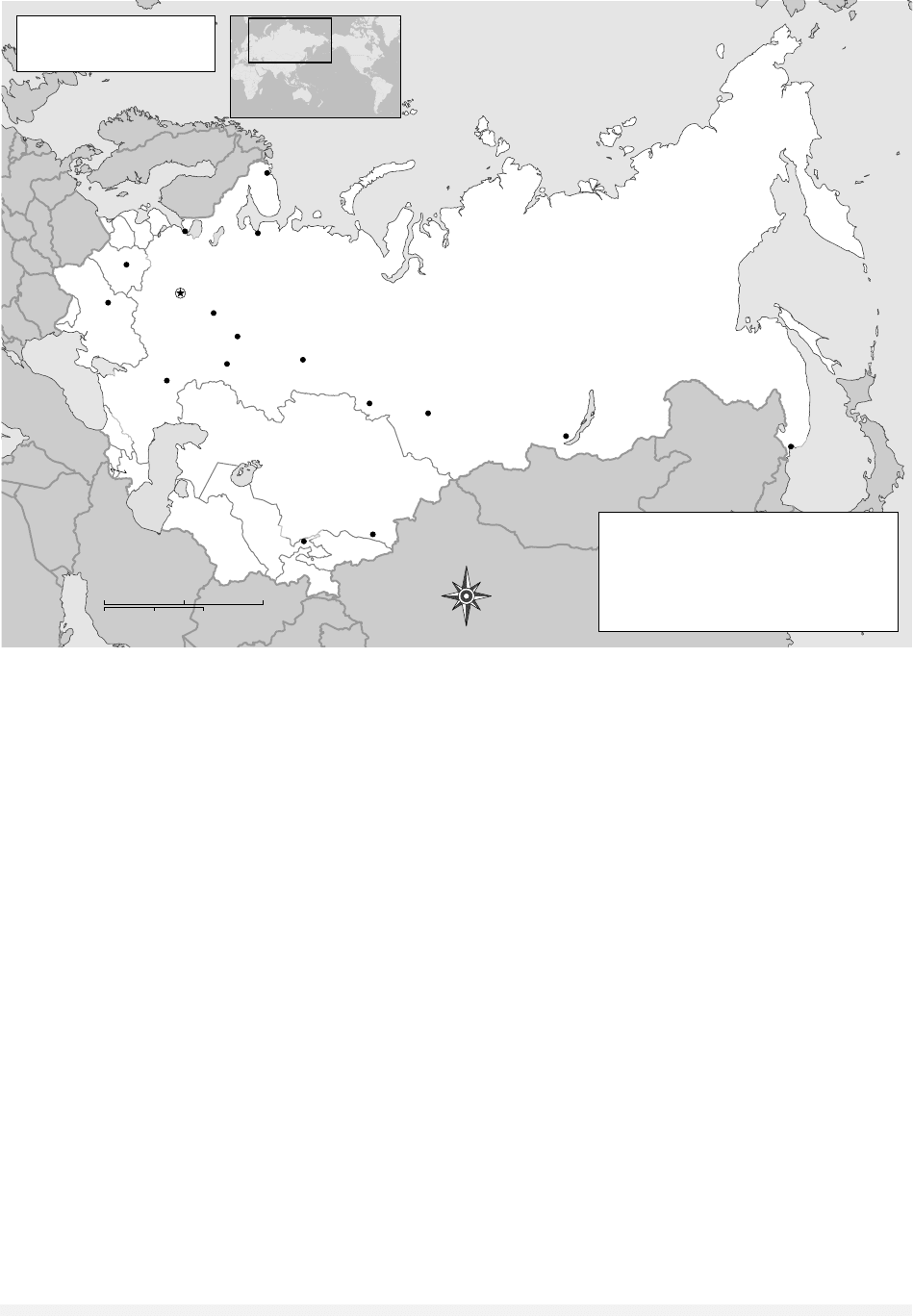

Lake

Baikal

Aral

Sea

C

a

s

p

i

a

n

S

e

a

B

l

a

c

k

S

e

a

Bering

Sea

Sea of

Okhotsk

ARCTIC OCEAN

C

A

U

C

A

S

U

S

M

T

S

.

U

R

A

L

M

O

U

N

T

A

I

N

S

SIBERIA

Novaya

Zemlya

Severnaya

Zemlya

New Siberian

Islands

Sakhalin

Arkhangel’sk

Vladivostok

Murmansk

Kuybyshev

Sverdlovsk

Kazan’

Omsk

Alma-Ata

Tashkent

Novosibirsk

Irkutsk

Moscow

Leningrad

Minsk

Gorkiy

Kiev

Volgograd

Kazakh

S.S.R.

Russian S.S.R.

Kyrgyz

S.S.R.

U

z

b

e

k

S

.

S

.

R

.

U

k

r

a

i

n

i

a

n

S

.

S

.

R

.

T

u

r

k

m

e

n

S

.

S

.

R

.

9

8

7

6

4

5

1

2

3

N

0 250 500 mi.

0 250 500 km

The Soviet Union

in 1985

1. Armenian S.S.R.

2. Azerbaijan S.S.R.

3. Belorussian S.S.R.

4. Estonian S.S.R.

5. Georgian S.S.R.

6. Latvian S.S.R.

7. Lithuanian S.S.R.

8. Moldavian S.S.R.

9. Tajik S.S.R.

SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1985. XNR P

RODUCTIONS

.

THE

G

ALE

G

ROUP

integrity of the Soviet state, Stalin imposed very

strong central control over the constituent republics

and appointed Russians to many of the high posts

in the non-Russian republics. The biggest change,

however, was in regard to the position of the Russ-

ian people within Soviet ideology. The Russians

were now portrayed as the elder brother of the So-

viet peoples whose culture and language provided

the means for achieving communist modernity. Ap-

preciation and love of Russian culture and language

was no longer regarded as a threat to Soviet iden-

tity, but rather a reflection of loyalty to it.

From Stalin’s death to the collapse of the USSR,

Soviet nationality policy was an amalgamation of

the policies followed during the first thirty-five years

of Soviet power. The peoples of the non-Russian re-

publics again filled positions in republican institu-

tions. Through access to higher education, privilege,

and the opportunity to exercise power within their

republican or local domain, the central leadership

created a sizeable and reliable body of non-Russian

cadres who, with their knowledge of the local lan-

guages and cultures, ruled the non-Russian parts of

the empire under the umbrella of the CPSU. How-

ever, Great Russians, meaning Russians, Ukrainians,

or Belarusians, usually occupied military and intel-

ligence service positions.

The Soviet command economy centered in

Moscow limited the power of the local and repub-

lican authorities. Through allocation of economic

resources, goods, and infrastructure, the central So-

viet authorities wielded a great degree of real power

throughout the USSR. Moreover, in traditional im-

perial style, Moscow exploited the natural resources

of all republics, such as Russian oil and natural gas

and Uzbek cotton, to fulfill all-union policies even

to the detriment of the individual republic.

The problem of assimilation of varied peoples

and the creation of a supranational identity re-

mained. After the death of Stalin, the Soviet leader-

ship realized that ethnic national feelings in the USSR

were not dissipating and in some cases were

strengthening. The Soviet leadership’s response was

essentially the promotion of a two-tiered identity.

On one level it spoke of the flourishing of national

identities and cultures. The leadership stressed, how-

ever, that this flourishing took place within a Soviet

framework in which the people’s primary loyalty

was to the Soviet identity and homeland. In other

words, enjoyment of one’s national culture and lan-

guage was not a barrier to having supreme loyalty

to the progressive supranational Soviet identity.

Nevertheless the existence of national feelings

continued to worry the Soviet leadership. During

the late 1950s it adopted a new language policy, at

the heart of which was expansion of Russian lan-

guage teaching. The hope was that acquisition of

Russian language and therefore culture would

bring with it the spread and strengthening of a So-

viet identity. The issue of language is always sen-

sitive in the imperial framework. Attempts by a

land-based empire to impose a single language fre-

quently results in enflaming national feelings

among the people whose native tongue is not the

imperial one. Yet every land-based empire, espe-

cially one the size of the USSR, needs a lingua franca

in order to govern and ease the challenges of ad-

ministration.

RUSSIA AND THE SOVIET EMPIRE

One of the more contentious issues concerns the

extent to which the Soviet Union was a Russian

empire. The USSR did exist in the space of the for-

mer tsarist empire. The Russian language was the

lingua franca. From Stalin onwards the Russians

and their high culture were portrayed as progres-

sive and therefore the starting point on the path

toward the modern Soviet identity. Great Russians

held the vast majority of powerful positions in the

center, as well as sensitive posts in the non-

Russian republics. Many people in the non-Russian

republics regarded the USSR and Soviet identity to

be only a different form of Russian imperialism dat-

ing from the tsarist period.

On the other hand the Soviets destroyed two

symbols of Russian identity—the tsar and the peas-

antry—while emasculating the other, the Russian

Orthodox Church. During the 1920s Lenin and

other Bolsheviks, seeing Russian nationalism as the

biggest internal threat to the Soviet state, worked

to contain it. The Russian Soviet Federated Social-

ist Republic, by far the largest of the republics of

the USSR whose population equaled all of the oth-

ers combined, had no separate Communist Party

and appropriate institutions in contrast to all of the

other republics. The Soviet regime used Russian

high culture and symbols, but in a sanitized form

designed to construct and strengthen a Soviet iden-

tity. The Russian people suffered just as much as

the other peoples from the crimes of the Soviet

regime, especially under Stalin. Already by the

1950s Russian nationalism was on the rise. The

Soviet regime was blamed for destroying Russian

culture and Russia itself through its reckless ex-

ploitation of land and natural resources in pursuit

EMPIRE, USSR AS

452

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY