Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

scribes in one of his later editions as the antago-

nism of narrow-minded people, and he moved to

Zabludovo in Belarus together with his son (also

named Ivan) and Petr Mstislavets. Here he opened

a new print shop under the sponsorship of Hetman

G. A. Khodkevich and produced several more edi-

tions, including the Evangelie uchitelnoe (1569, In-

structive Evangelary) and a psalter (1570). Advised

by his aging sponsor to retire to farming on land

provided him, he declined, saying he was suited to

sowing not seeds but the printed word. Instead, he

moved to the city of Lviv (now in Ukraine), where

with his son he printed more editions, including a

reprint of his Moscow Apostol (1573–1574), and

the Bukvar (1574, Primer).

Federov subsequently established one more

print shop, on the estate of Prince Kostiantyn (Con-

stantine) of Ostroh, participating in the latter’s de-

fense of Eastern Orthodoxy against increasing

pressure from Western denominations. The major

publication among the several issued there was the

famous Ostroh Bible, which remains of prime his-

torical, textual, and confessional importance. The

first complete printed Church Slavonic Bible, it was

issued in a large print-run and widely distributed

among East Slavic lands and abroad, surviving in

the early twenty-first century in some 300 copies.

In 1581 Ivan left Ostroh to return to Lviv, where

he died on December 15, 1583. He was buried in

the Onufriev Monastery; his gravestone read, in

part, “printer of books not seen before.” The liter-

ature devoted to Ivan Fyodorov is vast, well ex-

ceeding two thousand titles, mostly in Russian and

other Slavic languages.

See also: EDUCATION; IVAN IV

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Ivan Fedorov’s Primer of 1574: Facsimile Edition,” with

commentary by Roman Jakobson; appendix by

William A. Jackson. (1955). Harvard Library Bulletin

IX-1:1–44.

Mathiesen, Robert. (1981). “The Making of the Ostrih

Bible.” Harvard Library Bulletin 29(1): 71–110.

Thomas, Christine. (1984). “Two East Slavonic primers:

Lvov 1574 and Moscow 1637.” British Library Jour-

nal 10(1): 60–67.

H

UGH

M. O

LMSTED

FYODOROV, IVAN

533

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

This page intentionally left blank

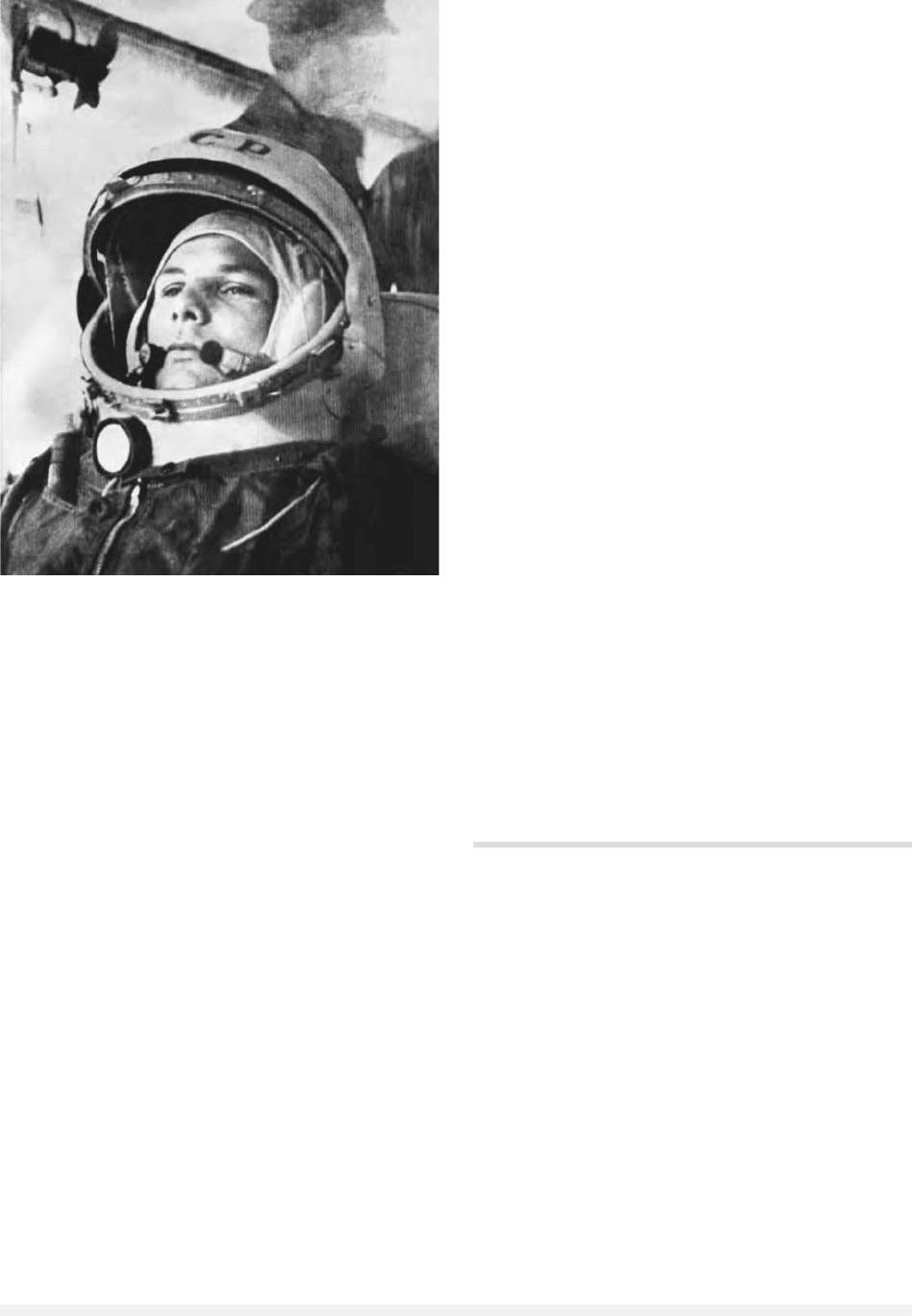

GAGARIN, YURI ALEXEYEVICH

(1934–1968), cosmonaut; first human to orbit

Earth in a spacecraft.

The son of a carpenter on a collective farm,

Yury Gagarin was born in the village of Klushino,

Smolensk Province. During World War II, facing

the German invasion, his family evacuated to Gzi-

atsk (now called Gagarin City). Gagarin briefly at-

tended a trade school to learn foundry work, then

entered a technical school. He joined the Saratov

Flying Club in 1955 and learned to fly the Yak-18.

Later that year, he was drafted and sent to the

Orenburg Flying School, where he trained in the

MIG jet. Gagarin graduated November 7, 1957,

four days after Sputnik 2 was launched. He mar-

ried Valentina Goryacheva, a nursing student, the

day he graduated.

Gagarin flew for two years as a fighter pilot

above the Arctic Circle. In 1958 space officials re-

cruited air force pilots to train as cosmonauts.

Gagarin applied and was selected to train in the first

group of sixty men. Only twelve men were taken

for further training at Zvezdograd (Star City), a

training field outside Moscow. The men trained for

nine months in space navigation, physiology, and

astronomy, and practiced in a mockup of the space-

craft Vostok. Space officials closely observed the

trainees, subjecting them to varied physical and

mental stress tests. They finally selected Gagarin

for the first spaceflight. Capable, strong, and even-

tempered, Gagarin represented the ideal Soviet man,

a peasant farmer who became a highly trained cos-

monaut in a few short years. Sergei Korolev, the

chief designer of spacecraft, may have consulted

with Nikita Khrushchev, Russia’s premier, to make

the final selection.

Gagarin was launched in Vostok 1 on April 12,

1961, from the Baikonur Cosmodrome near Tyu-

ratam, Kazakhstan. The Vostok spacecraft included

a small spherical module on top of an instrument

module containing the engine system, with a three-

stage rocket underneath. Gagarin was strapped into

an ejection seat. He did not control the spacecraft,

due to uncertainty about how spaceflight would

affect his physical and mental reactions. He orbited

the earth a single time at an altitude of 188 miles,

flying for one hour and forty-eight minutes. He

then ejected from the spacecraft at an altitude of

seven kilometers, parachuting into a field near

Saratov. His mission proved that humans could

survive in space and return safely to earth.

G

535

Gagarin was sent on a world tour to represent

the strength of Soviet technology. A member of the

Communist Party since 1960, he was appointed a

deputy of the Supreme Soviet and named a Hero

of the Soviet Union. He became the commander of

the cosmonaut corps and began coursework at the

Zhukovsky Institute of Aeronautical Engineering.

An active young man, Gagarin often felt frustrated

in his new life as an essentially ceremonial figure.

There were many reports of Gagarin’s resulting de-

pression and hard drinking. In 1967, however, he

decided to train as a backup cosmonaut in antici-

pation of a lunar landing.

On March 27, 1968, Gagarin conducted a test

flight with a senior flight instructor near Moscow.

The plane crashed, killing both men instantly.

Gagarin’s tragic death shocked the public in the

USSR and abroad. A special investigation was con-

ducted amid rumors that Gagarin’s drinking caused

the crash. Since then, investigators have indicated

other possible causes, such as poor organization

and faulty equipment at ground level.

Gagarin received a state funeral and was buried

in the Kremlin Wall. American astronauts Neil

Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin left one of Gagarin’s

medals on the moon as a tribute. The cosmonaut

training center where he had first trained was

named after him. A crater on the moon bears his

name, as does Gagarin Square in Moscow with its

soaring monument, along with a number of mon-

uments and streets in cities throughout Russia. At

Baikonur, a reproduction of his training room is

traditionally visited by space crews before a launch.

Russians celebrate Cosmonaut Day on April 12

every year in honor of Gagarin’s historic flight.

See also: SPACE PROGRAM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gagarin, Yuri. (1962). Road to the Stars, told to Nikolay

Denisov and Serhy Borzenko, ed. N. Kamanin, tr. G.

Hanna and D. Myshnei. Moscow: Foreign Languages

Publishing House.

Gurney, Clare, and Gurney, Gene. (1972). Cosmonauts in

Orbit: The Story of the Soviet Manned Space Program.

New York: Franklin Watts.

Johnson, Nicholas L. (1980). Handbook of Soviet Manned

Space Flight. San Diego, CA: Univelt.

Riabchikov, Evgeny. (1971). Russians in Space, tr. Guy

Daniels. New York: Doubleday.

Shelton, William. (1969). Soviet Space Exploration: The

First Decade, intro. by Gherman Titov. London:

Barker.

P

HYLLIS

C

ONN

GAGAUZ

More than ten hypotheses exist about the origins

of the Gagauz, although none of them has been

proven decisively. In Bulgarian and Greek scholar-

ship, the Gagauz are considered, respectively, to be

Bulgarians or Greeks who adopted the Turkish lan-

guage. The Seljuk theory is popular in Turkey. It

argues that the Gagauz are the heirs of the Seljuk

Turks who in the thirteenth century resettled in

Dobrudja under the leadership of Sultan Izeddina

Keikavus, and together with the Turkish-speaking

Polovetsians of the southern Russian steppes

(Kipchaks in Arabic, Kumans in European histori-

ography) established the Oghuz state (Uzieialet).

In Russia scholars believe that the base of

the Gagauz was laid by Turkish-speaking nomads

GAGAUZ

536

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin prepares to be the first man to orbit

the Earth. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS. R

EPRODUCED BY PERMISSION

.

(Oghuz, Pechenegs, and Polovetsians) who settled

in the Balkan Peninsula from Russia in the twelfth

and thirteenth centuries, and there turned from no-

madism into a settled population and adopted

Christianity.

During the Russian-Turkish wars at the end of

the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth cen-

turies, the Gagauz resettled in the Bujak Steppe of

southern Bessarabia, which had been emptied of the

Nogai and annexed by the Russian Empire. From

1861 to 1862 a group of Gagauz settled in the Tau-

ride province, a region that is today part of Ukraine.

During the Stolypin agrarian reforms of 1906 to

1911, some of the Gagauz resettled in Kazakhstan,

and in the 1930s, in protest against the collec-

tivization imposed by Josef Stalin, they moved to

Uzbekistan. There they stayed until the end of the

1980s under the name of Bulgars. At the end of

the 1920s a few dozen families, in order to save

themselves from the discriminatory policies of ru-

manization, migrated to Brazil and Canada.

The short-lived migration of some families to

southern Moldavia, at the time of the Khrushchev

Thaw at the end of the 1950s, was unsuccessful.

According to the census of 1989, there were

198,000 Gagauz in the former Soviet Union, of

whom 153,000 lived in Moldavia, 32,000 in

Ukraine, and 10,000 in the Russian Federation.

One-third of the Gagauz lived in cities.

Those Gagauz who are religious are Orthodox.

The Gagauz language belongs to the southwestern

(Oghuz) subgroup of the Turkish group of the Al-

taic language family. At the beginning of the nine-

teenth century, folklore texts were published in the

Gagauz language, using the Cyrillic alphabet. In

1957 a literary language was established on the ba-

sis of the Russian alphabet. On January 26, 1996,

by order of the People’s Assembly of Gagauzia,

writing switched to the Latin alphabet. The official

languages in Gagauzia are Moldavian, Gagauz, and

Russian.

The majority of the Gagauz are bilingual. In

1959, 94.3 percent of Gagauz spoke the language

of their nationality; in 1989, 87.4 percent. The

Gagauz speak fluent Russian. In 2000 the Gagauz

language was taught in forty-nine schools, in

Komrat State University, and in teachers’ colleges

and high schools.

The contemporary culture of the Gagauz is rep-

resented by the State Dramatic Theater (in the city

of Chadyr-Lunga), the Kadynzha Ensemble, and

musical and folklore groups.

On January 24, 1994, the parliament of the

Republic of Moldova passed the law On the Special

Legal Status of Gagauzia (Gagauz Eri), which es-

tablished the autonomous region of Gagauzia. This

new form of self-determination for the Gagauz was

based on the two principles of ethnicity and terri-

tory and won great approval in Europe.

At the turn of the twentieth century cattle-

raising and livestock husbandry dominated, this

has been replaced by agriculture, viniculture, to-

bacco farming, and industrial production.

See also: MOLDOVA AND MOLDOVANS; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

M

IKHAIL

G

UBOGLO

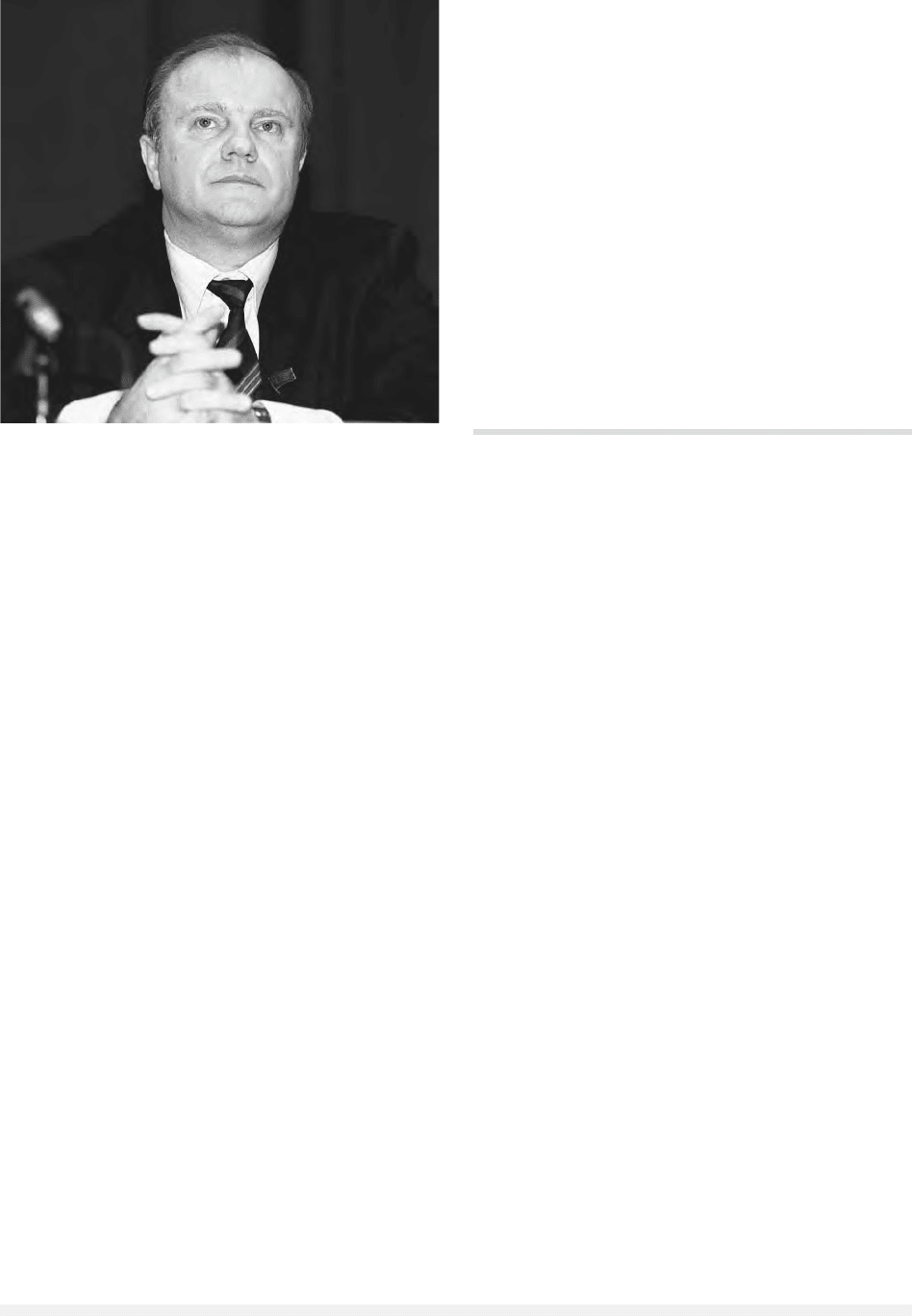

GAIDAR, YEGOR TIMUROVICH

(b. 1956), economist, prime minister.

The public face of shock therapy, Yegor Timu-

rovich Gaidar was a soft-spoken economist who,

at the age of thirty-six, became prime minister in

the turbulent first year of Boris Yeltsin’s adminis-

tration. He came from a prominent family: his fa-

ther was Pravda’s military correspondent, and his

grandfather a war hero and author beloved by gen-

erations of Soviet children. Gaidar graduated from

Moscow State University in 1980 with a thesis on

the price mechanism, supervised by reform econo-

mist Stanislav Shatalin. He then worked as a re-

searcher at the Academy of Sciences Institute of

Systems Analysis. In 1983 he joined a commission

on economic reform that advised General Secretary

Yuri Andropov. In 1986, he formed an informal

group, Economists for Reform, and from 1987 to

1990 he was an editor at the Communist Party

journal Kommunism, under the reformist editor

Otto Latsis. In 1990, he became a department head

at Pravda and headed a new Institute of Economic

Policy. Gaidar walked into the White House dur-

ing the August coup and offered his services to

Yeltsin aide Gennady Burbulis. With the support of

the young democratic activists, Gaidar became a

key player in Yeltsin’s team, drafting his economic

program and even the Belovezh accords, which

broke up the Soviet Union. He later described him-

self as on a kamikaze mission to turn Russia into

a market economy. As deputy prime minister (with

Yeltsin serving as prime minister) and minister of

finance and economics from November 1991,

Gaidar oversaw the introduction of price liberal-

GAIDAR, YEGOR TIMUROVICH

537

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ization in January 1992. Russia experienced a burst

of hyper-inflation, but formerly empty store

shelves filled with goods. Communist and nation-

alist opposition leaders unfairly blamed the col-

lapsing economy on Yeltsin’s policies and Gaidar’s

ideas. Gaidar was appointed acting prime minister

in June 1992, but the Congress of People’s Deputies

refused to approve his appointment in December.

He left the government, returning as economics

minister and first deputy prime minister in Sep-

tember 1993, in the midst of Yeltsin’s confronta-

tion with the parliament. At one point in the crisis

Gaidar appealed to people over television to take to

the streets to defend the government. Gaidar took

part in the creation of a liberal, progovernment

electoral bloc, Russia’s Choice, but it lost to red-

brown forces in the December 1993 parliamentary

elections, winning just 15.5 percent of the party

list vote. Gaidar left the government in January

1994, although he stayed on as leader of Russia’s

Choice in Parliament. At the same time, Gaidar be-

came head of his own think tank, the Institute of

Transition Economies. In the December 1995 elec-

tions he led the renamed Russia’s Democratic

Choice, which failed to clear the five percent thresh-

old. He spoke out against the war in Chechnya, but

supported Yeltsin in the 1996 election. During the

later 1990s Gaidar served more as an author and

commentator than as a front-rank politician. He

defended his record, advocated more liberal reform,

and pursued business and academic interests. He

was again elected to the Duma in December 1999

as head of the Union of Right Forces, an umbrella

group uniting most of the fractured liberal leaders.

The bloc went on to offer conditional support to

President Vladimir Putin.

See also: GORBACHEV, MIKHAIL SERGEYEVICH; PERE-

STROIKA; PRIME MINISTER; PRIVATIZATION; SHOCK

THERAPY; YELTSIN, BORIS NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gaidar, Yegor. (2000). Days of Defeat and Victory. Seat-

tle, WA: University of Washington Press.

P

ETER

R

UTLAND

GAMSAKHURDIA, ZVIAD

(1931–1999), human rights activist and writer.

Born the son of Konstantin Gamsakhurdia, a

famous Georgian writer and patriot, Zviad Gam-

sakhurdia became a leading Georgian dissident and

human rights activist in the Soviet Union. In 1974,

along with a number of fellow Georgian dissidents,

he formed the Initiative Group for the Defense of

Human Rights and in 1976, the Georgian Helsinki

Group (later renamed the Helsinki Union). Active in

the Georgian Orthodox church, during the 1970s

he wrote and published a number of illegal samiz-

dat (self-published) journals. The best-known were

The Golden Fleece (Okros sats’misi) and The Georgian

Messenger (Sakartvelos moambe). Arrested in 1977

for the second time (he was first imprisoned in

1957), after a public confession he was released in

1979 and resumed his dissident activities. After the

arrival of perestroika, he participated in the found-

ing of one of the first Georgian informal organiza-

tions in 1988, the Ilya Chavchavadze the Righteous

Society. An active leader in major demonstrations

and protests in 1988–1989, he became the most

popular anticommunist national figure in Georgia

and swept to power in October 1990 as leader of

a coalition of nationalist parties called the Round

Table-Free Georgia Bloc. Elected Chairman of the

Georgian Supreme Soviet, after amendments to the

constitution, he was elected the first president of

the Georgian Republic in May 1991.

His period in office was brief and unsuccessful.

Unable to make the transition from dissident ac-

tivist to political mediator and statesman, his in-

GAMSAKHURDIA, ZVIAD

538

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Yegor Gaidar directed Russia’s 1992 shock-therapy program.

© K

EERLE

G

EORGES

D

E

/CORBIS SYGMA

creasing authoritarianism alienated almost every

interest group in Georgian society. A coalition of

paramilitary groups, his own government’s Na-

tional Guard, intellectuals, and students joined to

overthrow him in a fierce battle in the city center

in January 1992. He made his base in neighboring

Chechnya and in 1993 attempted to reestablish his

power in Georgia, leading the country into civil

war. Quickly defeated after his forces captured a

number of major towns in west Georgia, he was

killed, or committed suicide in December 1993 in

the Zugdidi region, Georgia.

See also: GEORGIA AND GEORGIANS; NATIONALISM IN THE

SOVIET UNION; PERESTROIKA

S

TEPHEN

J

ONES

GAPON, GEORGY APOLLONOVICH

(1870–1906), Russian Orthodox priest led a peace-

ful demonstration of workers to the Winter Palace

on Bloody Sunday, 1905; the event began the 1905

revolution.

Father Georgy Apollonovich Gapon was a

Ukrainian priest who became involved with mis-

sionary activity among the homeless in St. Peters-

burg, where he was a student at the St. Petersburg

Theological Academy. His work attracted the at-

tention of police authorities, and when Sergei Zu-

batov began organizing workers in police-sponsored

labor groups, Gapon was brought to his attention.

Zubatov’s efforts in Moscow ran into the opposi-

tion of industrialists who objected to police inter-

ference in business matters. In St. Petersburg

Zubatov tried to tone down police involvement by

recruiting clergy to provide direction to his work-

ers. Gapon was reluctant to become involved, sens-

ing opposition to Zubatov among the officials and

the distrust of workers, but he began attending

meetings and established contacts with the more in-

fluential workers. He also argued with Zubatov that

workers should be allowed to decide for themselves

what was good for them.

During the summer of 1903, Zubatov was dis-

missed and given twenty-four hours to leave the

city. In this manner Gapon inherited an organiza-

tion created and patronized by the police. On the

surface Gapon seemed to justify the trust of the

authorities. A clubroom was opened where meet-

ings began with prayers and the national anthem.

Portraits of the tsars hung on the wall. Ostensibly

there were no reasons for the authorities to be con-

cerned about the Assembly, as the organization was

named, but beneath the surface, Gapon’s ambitious

plans began to unfold. Gathering a small group of

the more active workers, he unveiled to them his

“secret program,” which advocated the winning of

labor concessions through the strength of orga-

nized labor. His advocacy of trade unionism met

with the enthusiastic support of the conferees, and

he gained loyal supporters who would provide the

leadership of the Assembly.

During the turbulent year of 1904, the As-

sembly grew rapidly. By the end of the year it had

opened eleven branches. However, its rapid growth

was causing concern among the factory owners,

who feared the growing militancy of the workers

and resented police interference on their behalf.

Shortly before Christmas, four workers, all active

members of the Assembly, were fired at the giant

Putilov Works. Rumors spread that all members of

the Assembly would be fired. When Gapon and po-

lice authorities tried to intercede, they were told

that labor organizations were illegal and that the

Assembly had no right to speak for its members.

Faced with a question of survival, Gapon called a

large meeting of his followers, at which it was de-

cided to strike the Putilov Works—a desperate mea-

sure, since strikes were illegal.

The strike began on January 16, and by Jan-

uary 17 the entire working force in the capital had

joined the strike. Branches turned into perpetual

gatherings and rallies of workers. At one of the

meetings, Gapon threw out an idea of a peaceful

mass demonstration to present a workers’ petition

to the tsar himself. The idea caught on like fire.

Gapon began preparing the petition. It essentially

contained the more specific demands of his secret

program and a vague compilation of the most pop-

ular demands of the opposition groups. Copies of

the petition, “Most Humble and Loyal Address to

be presented to the Tsar at 2 P.M. on the Winter

Palace Square,” were sent to various officials.

Meanwhile the march was prohibited, and re-

inforcements were brought to St. Petersburg. Po-

lice tried to arrest Gapon, but he could not be found.

By then the workers were too agitated to abandon

their hope to see the tsar; moreover, they did not

think soldiers would fire on a peaceful procession

that in some places was presented as a religious

procession. But the soldiers opened fire in several

locations, resulting in more than 130 casualties.

GAPON, GEORGY APOLLONOVICH

539

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

These events, known as Bloody Sunday, began the

revolution of 1905.

Gapon called for a revolution, then escaped

abroad. Becoming disillusioned with the revolu-

tionary parties, he attempted to reconcile with the

post-1905 regime of Sergei Witte. Upon his return

to St. Petersburg, he tried to revive his organiza-

tion but was killed by a terrorist squad acting on

the orders of the notorious double agent, Evno Azef.

To explain Gapon’s murder, the perpetrators con-

cocted a story of a workers’ trial and execution.

See also: BLOODY SUNDAY; REVOLUTION OF 1905;

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH; ZUBATOV, SERGEI

VASILIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ascher, Abraham. (1988). “Gapon and Bloody Sunday.”

Revolution of 1905, vol. 1. Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press.

Gapon, Georgy A. (1905). The Story of My Life. London:

Chapman & Hall.

Sablinsky, Walter. (1976). The Road to Bloody Sunday: Fa-

ther Gapon and the St. Petersburg Massacre of 1905.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

W

ALTER

S

ABLINSKY

GASPIRALI, ISMAIL BEY

(1851–1914), Crimean Tatar intellectual, social re-

former, publisher, and key figure in the emergence

of the modernist, or jadid, movement among Rus-

sian Turkic peoples.

Ismail Bey Gaspirali was born March 8, 1851,

in the Crimean village of Avci, but he spent most

of his first decade in Bakhchisarai, the nearby town

to which his family had moved during the Crimean

War (1853–1856). Reared in the Islamic faith, his

education began with tutoring in Arabic recitation

by a local Muslim teacher (hoca), but then contin-

ued in the Russian-administered Simferopol gym-

nasium and Russian military academies in Voronezh

and Moscow. In 1872 he embarked on a foreign

tour that took him through Austria and Germany

to France, where he remained for two years. A year

followed in Istanbul, capital of the Ottoman Em-

pire, before Gaspirali returned home during the

winter of 1875. His observations abroad became

the basis for one of his earliest and most impor-

tant essays, A Critical Look at European Civilization

(Avrupa Medeniyetine bir Nazar-i Muvazene, 1885),

and inspired the urban improvement projects dur-

ing the four years (1878–1882) that he served as

mayor of Bakhchisarai.

By then, the importance of education and the

modern press had become for Gaspirali the keys to

improving the quality of life for Crimean Tatars

and other Turkic peoples, who were mostly ad-

herents of Islam. Nineteenth-century European

military might, economic development, scientific

advances, increased social mobility, political exper-

imentation, and global expansion impressed upon

him the need for reconsideration of Turkic cultural

norms, perspectives, and aspirations. The narrow

focus of education, inspired by centuries of Islamic

pedagogy whose purpose was the provision of suf-

ficient literacy in Arabic for reading and reciting the

Qur’an, struck Gaspirali as unsuited for the chal-

lenges of modern life as defined by European

experience. A new teaching method (usul-i jadid),

emphasizing literacy in the child’s native lan-

guage, and a reformed curriculum that included

study of mathematics, natural sciences, geography,

history, and the Russian language, should be in-

stituted in new-style primary schools where chil-

dren would be educated in preparation for enrolling

in more advanced, modern, and Russian-supported

institutions. The survival of non-European societies

such as his own, many already the victims of Eu-

ropean hegemony and their own adherence to time-

honored practices, depended upon a willingness to

accept change and new information, open up pub-

lic opportunities for women, mobilize resources

and talents, and become involved with worldly af-

fairs.

The medium by which Gaspirali propagandized

his new method, both as pedagogue and social

transformer, was the modern press. Beginning in

April 1883, he published a dual-language newspa-

per in both Turkic and Russian entitled The Inter-

preter (Tercüman in Turkic, Perevodchik in Russian).

It appeared without interruption until early 1918,

becoming the longest surviving and most influen-

tial Turkic periodical within the Russian Empire. In

later years, Gaspirali published other newspapers—

The World of Women (Alem-i Nisvan), The World of

Children (Alem-i Sibyan), and Ha, Ha, Ha! (Kha, Kha,

Kha!), a satirical review—and numerous essays and

didactic manuals on subjects ranging from Turkic

relations with Russia to pedagogy, geography, hy-

giene, history, and literature.

Gaspirali’s espousal of substantive social change

raised opposition from both Russian and Turkic

GASPIRALI, ISMAIL BEY

540

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

sources, but his moderate and reasoned tone won

him important allies within local and national of-

ficial circles, allowing him to continue his work

with little interference. The intensification of eth-

nic controversy by the early twentieth century,

however, increasingly marginalized him in relation

to advocates of more strident nationalist sentiments

and the politicization of Russian-Turkic relations.

He died September 11, 1914 after a long illness.

See also: CRIMEAN TATARS; ISLAM; JADIDISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fisher, Alan W. (1988). “Ismail Gaspirali, Model Leader

for Asia.” In Tatars of the Crimea: Their Struggle for

Survival, ed. Edward Allworth. Durham: Duke Uni-

versity Press.

Kuttner, Thomas. (1975). “Russian Jadidism and the Is-

lamic World: Ismail Gasprinskii in Cairo—1908. A

Call to the Arabs for the Rejuvenation of the Islamic

World.” Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique

16:383–424.

Lazzerini, Edward J. (1988). “Ismail Bey Gasprinskii, the

Discourse of Modernism, and the Russians.” In Tatars

of the Crimea: Their Struggle for Survival, ed. by Ed-

ward Allworth. Durham: Duke University Press.

Lazzerini, Edward J. (1992). “Ismail Bey Gasprinskii’s

Perevodchik/Tercüman: A Clarion of Modernism.” In

Central Asian Monuments, ed. by H.B. Paksoy. Istan-

bul: Isis Press.

E

DWARD

J. L

AZZERINI

GATCHINA

One of the great imperial country palaces to the

south of St. Petersburg, Gatchina was located near

the site of a village known since 1499 as Khotchino.

In 1708 Peter I granted the land to his beloved sis-

ter Natalia Alexeyevna, after whose death in 1717

the property belonged to a series of favored court

servitors. In 1765 Catherine II purchased the estate

from the family of Prince Alexander Kurakin and

presented it to Grigory Orlov. She commissioned

the Italian architect Antonio Rinaldi to design for

Orlov a lavish palace-castle in a severe and monu-

mental neoclassical style. Rinaldi, who had worked

with the Neapolitan court architect Luigi Vanvitelli,

created not only a grandiose palace ensemble but

also a refined park.

The palace, begun in 1766 but not completed

until 1781, was conceived as a three-story block

with square, one-story service wings—designated

the Kitchen and Stables—attached to either side of

the main structure by curved colonnades. In order

to project the appearance of a fortified castle, Rinaldi

departed from the usual practice of stuccoed brick

and surfaced the building in a type of limestone

found along the banks of the nearby Pudost River.

The flanking towers of the main palace and its re-

strained architectural detail further convey the ap-

pearance of a forbidding structure. On the interior,

however, the palace contained a display of luxuri-

ous furnishings and decorative details, including lav-

ish plaster work and superb parquetry designed by

Rinaldi. Rinaldi also contributed to the development

of the Gatchina park with an obelisk celebrating the

victory of the Russian fleet at Chesme. The exact

date of the obelisk is unknown, but presumably it

was commissioned by Orlov no later than the mid-

1770s in honor of his brother Alexei Orlov, general

commander of the Russian forces at Chesme.

Following the death of Orlov in 1783, Cather-

ine bought the estate and presented it to her son

and heir to the throne, Paul. He in turn commis-

sioned another Italian architect, Vincenzo Brenna,

to expand the flanking wings of the palace. Brenna,

with the participation of the brilliant young Rus-

sian architect Adrian Zakharov, added another floor

to the service wings and enclosed the second level

of a colonnade that connected them to the main

palace. Unfortunately, these changes lessened the

magisterial Roman quality of the main palace

structure. Brenna also modified and redecorated a

number of the main rooms, although he continued

the stylistic patterns created by Rinaldi.

Grand Duke Paul was particularly fond of the

Gatchina estate, whose castle allowed him to in-

dulge his zeal for a military order based, so he

thought, on Prussian traditions. The palace became

notorious for military drills on the parade grounds

in front of its grand facade. With the accession

of Paul to the throne after the death of Catherine

(November 1796), the Gatchina regime extended

throughout much of Russia, with tragic results not

only for the emperor’s victims but also for Paul

himself. After his assassination, in 1801, the palace

reverted to the crown.

Among the many pavilions of the Gatchina

park, the most distinctive is the Priory, the prod-

uct of another of emperor Paul’s fantasies. After

their expulsion from the island of Malta, Paul ex-

tended to the Maltese Order protection and refuge,

including the design of a small pseudo-medieval

palace known as the Priory, intended for the prior

GATCHINA

541

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of this monastic military order. In his construction

of the Priory, the architect Nikolai Lvov made in-

novative use of pressed earth panels, a technique

that Paul had observed during a trip to France. The

relatively isolated location of the Priory made it a

place of refuge in 1881–1883 for the new emperor,

Alexander III, concerned about security in the wake

of his father’s assassination.

For most of the nineteenth century the palace

drifted into obscurity, although it was renovated

from 1845 to 1852 by Roman Kuzmin. After the

building of a railway through Gatchina in 1853,

the town, like nearby Pavlovsk, witnessed the de-

velopment of dacha communities. Gatchina briefly

returned to prominence following the Bolshevik

coup on November 7, 1917. The deposed head of

the Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky,

attempted to stage a return from Gatchina, but by

November 14 these efforts had been thwarted. In

the fall of 1919 the army of General Nikolai Yu-

denich also occupied Gatchina for a few weeks be-

fore the collapse of his offensive on Petrograd.

After the Civil War, the palace was national-

ized as a museum, and in 1923 the town’s name

was changed to Trotsk. Following Trotsky’s fall

from power, the name was changed again, in 1929,

to Krasnogvardeysk. With the liberation of the

town from German occupation in January 1944,

the imperial name was restored. Notwithstanding

the efforts of museum workers to evacuate artis-

tic treasures, the palace ensemble and park suffered

catastrophic damage between September 1941 and

1944. Major restoration work did not begin until

the 1970s, and in 1985 the first rooms of the palace

museum were reopened.

See also: ARCHITECTURE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brumfield, William Craft. (1993). A History of Russian

Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Orloff, Alexander, and Shvidovsky, Dmitri. (1996). St.

Petersburg: Architecture of the Tsars. New York:

Abbeville Press.

W

ILLIAM

C

RAFT

B

RUMFIELD

GENERAL SECRETARY

Top position in the Communist Party

Prior to the revolution, Vladimir I. Lenin, the

head of the Bolshevik faction, had a secretary,

Elena Stasova. After the Bolsheviks came to power

in 1917, Lenin gave the position of secretary in the

ruling Communist Party of Russia to Yakov Sverd-

lov, a man with a phenomenal memory. After

Sverdlov’s death in 1919, three people shared the

position of secretary. In 1922, in recognition of the

expanding party organization and the complexity

of the newly formed USSR, a general secretary was

appointed. Josef Stalin, who had several other ad-

ministrative assignments, became general secre-

tary, and used it to build a power base within the

party. Lenin, before his death, realized Stalin had

become too powerful and issued a warning in his

Last Testament that Stalin be removed. However,

skillful use of the patronage powers of the general

secretary solidified Stalin’s position. After Stalin’s

death in 1953, the position was renamed first

secretary of the Communist Party (CPSU) in an

attempt to reduce its significance. Nonetheless,

Nikita S. Khrushchev (1953–1964) succeeded in

using the position of first secretary to become the

single most powerful leader in the USSR. Khrush-

chev’s successor, Leonid I. Brezhnev (1964–1982)

restored the title of general secretary and emerged

as the most important political figure in the post-

Khrushchev era. Mikhail S. Gorbachev, working as

unofficial second secretary under general secre-

taries Yuri V. Andropov (1982–84) and Konstan-

tin U. Chernenko (1984–85), solidified his position

as their successor in 1985. Gorbachev subse-

quently reorganized the presidency in 1988–89,

and transferred his attention to that post. After the

1991 coup, Gorbachev resigned as general secre-

tary, one of several steps signaling the end of the

CPSU.

The position of general secretary was the

most influential role in leadership for most of the

Soviet period. Its role was closely associated with

the rise of Stalin and the end of the position was

also a signal of the end of the Soviet system.

See also: COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE SOVIET UNION; SUC-

CESSION OF LEADERSHIP, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hough, Jerry F. and Fainsod, Merle. (1979). How the So-

viet Union Is Governed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

Smith, Gordon B. (1988). Soviet Politics: Continuity and

Contradiction. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

N

ORMA

C. N

OONAN

GENERAL SECRETARY

542

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY