Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ployed French chefs. With so much foreign influ-

ence, Russian cuisine lost its simple national char-

acter. The eighteenth-century refinements broadened

Russian cuisine, ushering in an era of extravagant

dining among the wealthy.

The sophistication of the table was lost during

the Soviet period, when much of the populace sub-

sisted on a monotonous diet low in fresh fruits and

vegetables. Shopping during the Soviet era was es-

pecially difficult, with long lines even for basic

foodstuffs. Hospitality remained culturally impor-

tant, however, and the Soviet-era kitchen table was

the site of the most important social exchanges.

The collapse of the Soviet state brought nu-

merous Western fast-food chains, such as McDon-

ald’s, to Russia. With the appearance of self-service

grocery stores, shopping was simplified, and food

lines disappeared. However, food in post-Soviet

Russia, while plentiful and widely available, was

expensive during the early twenty-first century.

See also: AGRICULTURE; CAVIAR; PETER I; RUSSIAN OR-

THODOX CHURCH; VODKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Glants, Musya, and Toomre, Joyce, eds. (1997). Food in

Russian History and Culture. Bloomington: Indiana

University Press.

Goldstein, Darra. (1999). A Taste of Russia: A Cookbook of

Russian Hospitality, 2d ed. Montpelier, VT: Russian

Life Books.

Herlihy, Patricia. (2002). The Alcoholic Empire: Vodka and

Politics in Late Imperial Russia. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Molokhovets, Elena. (1992). Classic Russian Cooking: Elena

Molokhovets’ A Gift to Young Housewives, tr. Joyce

Toomre. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

D

ARRA

G

OLDSTEIN

FOREIGN DEBT

The first stage in Russia’s involvement with inter-

national capital markets was associated with the

great drive for industrialization that marked the fi-

nal decades of the nineteenth century. The back-

wardness of the country’s largely rural economy

implied substantial needs for imports, which in

turn meant foreign borrowing. The epic railway

construction projects in particular would not have

been possible without such financing.

With growing volumes of Russian debt float-

ing abroad, the country became increasingly vul-

nerable to speculative attacks, which could have

proven highly damaging. The skillful policies of fi-

nance ministers Ivan Vyshnegradsky and Sergei

Witte averted such dangers. By imposing harsh

taxes on the rural economy, they also managed to

promote exports from that sector, which made for

a healthy trade surplus. As a result of the latter,

by the end of the century the currency qualified

for conversion to the gold standard.

Russia thus entered the twentieth century with

a stable currency and in good standing on foreign

capital markets. The Bolsheviks put an end to that.

By deciding to default on all foreign debt of Impe-

rial Russia, Vladimir Lenin effectively deprived the

Soviet Union of all further access to foreign credit.

Since the economy remained backward, all subse-

quent ambitions of achieving industrialization thus

would have to be undertaken with domestic re-

sources, or with the goodwill of foreign govern-

ments offering loan guarantees.

An early illustration of problems resulting

from the latter scenario was provided during World

War II, when the Soviet Union received substantial

military assistance from its western allies, shipped

via the famed Murmansk convoys. Known as

“Lend-Lease,” the program was not originally in-

tended as a free gift, but during the subsequent Cold

War the Soviet Union refused to make repayments.

In 1972 the United States followed a previous

British example in forgiving ninety percent of the

debt. When Vladimir Putin became president in

2000, about $600 million of the remainder was

still outstanding—and more had been added.

Toward the end of the Soviet era, much-needed

modernization of the economy produced growing

demands for imports of foreign technology, which

in turn required foreign credits. Eager to have good

relations with Mikhail Gorbachev, many Western

governments gladly offered guarantees for such

loans. By the end of 1991, with the Soviet Union

in full collapse, those loans went into effective de-

fault. The total of all outstanding Soviet foreign

debt came to almost $100 billion.

The first decade of Russia’s post-Soviet exis-

tence was heavily marked by problems surround-

ing the handling of that debt. While foreign creditor

governments remained insistent that it be repaid,

they were also willing to offer substantial new

credits in support of Russia’s economic transition.

The Russian government responded by evolving a

FOREIGN DEBT

513

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

strategy for debt management that rested on ag-

gressively threatening default on old debt in order to

obtain forgiveness, rescheduling, and fresh credits.

Much of the subsequent political wrangling

would revolve around Russia’s increasingly con-

troversial relations with the International Mone-

tary Fund (IMF). An initial credit of $1 billion was

granted in July 1992, when Russia became a mem-

ber of the Fund. In 1993, a further $1.5 billion was

paid out, under a special “Systemic Transformation

Facility” (STF). As Moscow failed to live up even to

the soft rules of the STF, the IMF withheld dis-

bursement of an agreed second $1.5 billion tranche.

Following severe criticism for having failed to

offer proper support, in April 1994 the Fund de-

cided to release the second tranche of the STF. The

essentially political nature of the relation was now

becoming evident. Despite Russia’s continued prob-

lems in honoring its commitments, in April 1995

the IMF granted Russia a $6.5 billion twelve-month

credit, and in March 1996 it agreed to a three-year

$10.1 billion “Extended Fund Facility.”

The latter was the second-largest commitment

ever made by the Fund, and there was little effort

made to hide its essentially political purpose. The

objective was to secure the reelection of Boris

Yeltsin to a second term as president, and the IMF

was not alone in offering support. On a parallel

track, France and Germany offered bilateral credits

of $2.4 billion, and the “Paris Club” of foreign cred-

itor governments agreed to a rescheduling of $38

billion in Soviet-era debt.

The latter was of particular importance, in that

it opened the doors for Russia to the market for

Eurobonds. Receiving its first sovereign credit rat-

ing in October 1996, in November the Russian gov-

ernment placed a first issue of $1 billion, which

was to be followed, in March and June of the fol-

lowing year, by two further issues of DM2 billion

and $2 billion, respectively. Up until the crash in

August 1998, Russia succeeded in issuing a total of

$16 billion in Eurobonds.

As the Russian government was gaining cred-

ibility as a debtor in good standing, other Russian

actors, ranging from city governments to private

enterprises, also began to venture into the market.

Russian commercial banks in particular began se-

curing substantial loans from their partners in the

West.

Compounding the exposure, the Russian gov-

ernment was simultaneously saturating the mar-

ket with ruble-denominated government securities,

known as GKO and OFZ. While these instruments

technically represented domestic debt, they became

highly popular among foreign investors and there-

fore essential to the issue of foreign debt.

The final stage of Russia’s financial bubble was

heralded with the onset of the financial crisis in

Asia, during the summer of 1997. At first believed

to be immune to contagion by this “Asian flu,” in

the spring of 1998 Russia was becoming seriously

ill. In May, the Moscow markets were in free fall,

and by June the IMF was under substantial polit-

ical pressure to take action. Some even warned of

pending civil war in a country with nuclear ca-

pacities.

Following protracted negotiations, on July 13

the Fund announced a bailout package of $22.6 bil-

lion through December 1999, which was supported

both by the World Bank and by Japan. A first dis-

bursement of $4.8 billion was made on July 20,

and the financial markets began to recover confi-

dence. On August 17, however, the Russian gov-

ernment decided to devalue the ruble anyway and

to declare a ninety-day moratorium on short-term

debt service.

The potential losses were massive. The volume

of GKO debt alone was worth about $40 billion.

To this could be added $26 billion owed to multi-

lateral creditors, and the $16 billion in Eurobonds.

There also were additional billions in commercial

bank credits, including about $6 billion in ruble fu-

tures contracts. And there still remained $95 bil-

lion in Soviet-era debt, some of which had been

recently rescheduled.

In the spring of 1999, few believed that Russia

would be able to stage a comeback within the fore-

seeable future. One foreign banker even stated that

he would rather eat nuclear waste than lend any

more money to Russia. The situation was aggra-

vated by suspicions that the Russian Central Bank

was clandestinely bailing out well-connected do-

mestic actors, at the expense of foreign investors.

It was also hard for many to accept the Russian

government’s unilateral decision to ignore its So-

viet-era debt and to honor only purely “Russian”

debt.

A year later, fuelled by the ruble devaluation

and by rapidly rising oil prices, the Russian econ-

omy was making a spectacular recovery. In 2000,

the first year of the Putin presidency, GDP grew by

nine percent. The federal budget was finally in the

FOREIGN DEBT

514

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

black, with a good margin, and foreign trade gen-

erated a massive surplus of $61 billion. Despite this

drastic improvement in economic performance, the

Russian government nevertheless appeared bent on

continuing its policy of threatening default in or-

der to secure further restructuring and forgiveness

of its old debts.

For the German government in particular, this

finally proved to be too much. When the Russian

prime minister Mikhail Kasyanov hinted that Rus-

sia might not be able to meet its full obligations

in 2001, Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder informed

Moscow that in case of any further trouble with

Russian debt service, he would personally do all he

could to isolate Russia. The effect was immediate

and positive. From 2001 onward Russia has been

current on all sovereign foreign debt (excluding the

defaulted GKOs).

In support of its decision to fully honor its

credit obligations, the Russian government made

prudent use of its budget surplus. By accelerating

repayments of debt to the IMF, it drew down the

principal, and by introducing a strategic budget re-

serve to act as a cushion against future debt prob-

lems, it strengthened its credibility. The reward has

been a series of upgrades in Russia’s sovereign credit

rating, and a calming of previous fears about fur-

ther rounds of default.

While this has been positive indeed for Russia’s

international standing, it has not come without a

price. Every billion that is paid out in foreign debt

service effectively means one billion less in desper-

ately needed domestic investment. In that sense, it

will be a long time indeed before the Russian econ-

omy has finally overcome the damage that was

done by foreign debt mismanagement during the

Yeltsin years.

See also: BANKING SYSTEM, SOVIET; BANKING SYSTEM,

TSARIST; ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; ECONOMY,

CURRENT; INDUSTRIALIZATION; LEND LEASE.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hedlund, Stefan. (1999). Russia’s “Market” Economy: A

Bad Case of Predatory Capitalism. London: UCL Press.

Mosse, W.E. (1992). Perestroika under the Tsars. London:

I.B. Taurus.

Stone, Randall W. (2002). Lending Credibility: The Inter-

national Monetary Fund and the Post-Communist

Transition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

S

TEFAN

H

EDLUND

FOREIGN TRADE

Owing to its geographic size and diversity, Russia’s

foreign trade has always been relatively small, as

compared to countries of Western Europe with

whom it traded. Nevertheless, foreign trade has

provided contacts with western technologies, ideas,

and practices that have had considerable impact on

the Russian economy, even during periods when

foreign trade was particularly reduced. From ear-

liest times Russia has typically traded the products

of its forests, fields, and mines for the sophisticated

consumer goods and advanced capital goods of

Western Europe and elsewhere. Trade with Persia,

China, and the Middle East, as well as more remote

areas, has also been significant in certain times.

The first recorded Russian foreign trade contact

was a treaty concluded in 911 by Prince Oleg of

Kiev with the Byzantine emperor. During the me-

dieval period most of the trade was conducted

by gostiny dvor (merchant colonies), such as the

Hanseatic League, resident in Moscow or at fairs at

Novgorod or elsewhere. This practice was quite

typical of the European Middle Ages because of the

expense of travel and communication and the need

to assure honest exchanges and payment.

During the early modern period Russian iron

ore was very attractive to the British, but until the

coking coal of Ukraine became available during the

nineteenth century, Russia had to import much of

its smelted iron and steel. Up to about 1891, when

Finance Minister Ivan Vyshnegradsky raised the

tariff, exports of grain and textiles did not suffice

to cover imports, interest on previous loans, and

the expenses of Russians abroad. Hence Russia had

to depend on more foreign capital. Although Rus-

sia was known in this period as the “granary of

Europe,” prices were falling because of new sup-

plies from North America. Nonetheless, Vyshne-

gradsky insisted, “Let them eat less, and export!”

One aspect of the state-promoted industrial-

ization of 1880–1913 was an effort by the state

bureaucracy to increase exports in support of the

gold-backed ruble, introduced in 1897. To develop

outlets for Russian manufactures, the next minis-

ter of finances, Count Sergei Witte, encouraged

Russians consular officials to cultivate markets in

China, Persia, and Turkey, where prior trade had

been mostly in high-value goods such as furs.

Witte’s new railways, built for military purposes,

made exchange of bulkier items economical for

the first time. Subsidized sugar and cotton textiles

FOREIGN TRADE

515

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

would be sent to Persia and the East, with foreign

competition foreclosed by prohibition on transit

routes. Nonetheless, in 1913 fully sixty percent of

Russian exports were foodstuffs and animals, an-

other third lumber, petroleum, and other materi-

als. Scarcely six percent were textiles, much of it

from tsarist Poland. Russian imports were luxury

consumer goods (including coffee and tea), equip-

ment, and cotton fiber. Spurred by railroads, in-

dustrialization, and a convertible currency, foreign

trade during the tsarist period reached a peak just

before World War I with a turnover of $1.5 billion

in prices of the time. This total was not matched

after the Communist Revolution until the wartime

imports of 1943, paid for largely by loans. Exports

were approximately one-tenth of gross domestic

product in 1913, a proportion hardly approached

since. They were only four percent of GDP in 1977,

for example.

Under the Bolsheviks, Russia conducted an off-

and-on policy of self-sufficiency or autarky. Ac-

cording to Michael Kaser’s figures, export volumes

rose steadily from five percent of the 1913 level in

1922 to sixty-one percent by 1931. When Britain

signed a trade agreement in 1922 and others fol-

lowed, the Soviet government began to buy con-

sumer goods to provide incentives for the workers.

They also bought locomotives, farm machinery,

and other equipment to replace those lost in the

long war years. Exports also rose smartly.

With the beginnings of planning at the end of

the 1920s, however, trade fell off throughout the

1930s and the first half of the 1940s, reflecting ex-

treme trade aversion and suspicions of western in-

tentions on Josef Stalin’s part, as well as the general

world depression, which adversely affected Russia’s

terms of trade. Russia wanted to be as self-suffi-

cient as possible in case war cut off its supplies, as

indeed occurred from 1939 to 1945. Imports of

consumer goods fell precipitously, but so did some

important industrial materials that were now pro-

duced domestically. Since 1928, Russian exports

have averaged only about one to two percent of its

national income, as compared with six to seven per-

cent of that of the United States in a comparable

period. Imports showed a similarly mixed pattern,

with imports much exceeding exports during the

long war years.

After World War II, Russia no longer pursued

such an extreme policy of autarky. Export volumes

rose every year, reaching 4.6 times the 1913 level

by 1967. But they were still less than four percent

of output. The statistical breakdown of Soviet trade

was often censored. Its deficits on merchandise

trade account and invisibles were financed in un-

known part by sales of gold and by borrowings in

hard currency. The latter resulted in a growing

hard-currency debt to western creditors from 1970

onward, amounting to an estimated $11.2 billion

by 1978. Neglect of comparative advantage and in-

ternational specialization has probably been nega-

tive for economic growth and consumer welfare.

During the post–World War II period, most So-

viet merchandise imports and exports were traded

with the other Communist countries in bilateral

deals concluded under the auspices of the Council

of Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). Even

though trade with the developed capitalist coun-

tries of the West and with less developed countries

increased throughout this era, USSR trade with

other “socialist” states still exceeded fifty percent of

the total in 1979, while the share of the West was

about one-third. Trade with COMECON members

was nearly balanced year by year, but when it was

not, the difference was credited in “transferable

rubles,” a book entry that hardly committed either

side to future shipments. Franklyn Holzman

termed this feature of Soviet trade “commodity in-

convertibility,” as distinct from currency incon-

vertibility, which also characterized intra-bloc trade

and finance.

Trade with the developed western capitalist

countries was always impeded by the deficient

quality of Soviet manufactured goods, including

poor merchandising and after-sales service. Fur-

thermore, western countries also discriminated

against Soviet exports by their tariff and strategic

goods policies. Even so, some Russian-produced ar-

ticles, like watches produced in military factories

and tractors, entered a few markets. More signifi-

cantly, the USSR was able to export tremendous

quantities of oil, gas, timber, and nonferrous met-

als such as platinum and manganese, as well as

some heavy chemicals. Notable imports included

whole plants for the production of automobiles,

tropical foodstuffs, and grain during periods of

harvest failure.

Foreign trade was always a state monopoly in

the USSR, even during the New Economic Policy

(NEP). Under the control of the Minister of Foreign

Trade, foreign-trade “corporations” conducted the

buying and selling, though industrial ministries

and even republic authorities could be involved in

the negotiations. Barter deals at the frontiers and

FOREIGN TRADE

516

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tourist traffic provide trivial exceptions to the rule.

The object of the monopoly was to fit imports and

exports into the overall plan regardless of changes

in world prices and availabilities. Foreign trade cor-

porations are not responsible for profits or losses

caused by the difference between the prices they ne-

gotiate and the corresponding ruble price, given the

arbitrary exchange rate. Exports must be planned

to cover the cost of necessary imports—notably pe-

troleum, timber, and natural gas during the last

decades in exchange for materials, equipment, and

foodstuffs during poor harvest years. Hence enter-

prise managers were told what to produce for ex-

port and what may be available from foreign

sources. Thus, they had little or no knowledge of

foreign conditions, nor interest in adjusting their

activities to suit the international situation of the

USSR. With internal prices unrelated to interna-

tional scarcities, the planning agencies could not al-

low ministries or chief administration, still less

enterprises, to decide on their own what to buy or

sell abroad. Tariffs were strictly for revenue pur-

poses. For instance, when the world market price

of oil quadrupled in 1973–1974, the internal So-

viet price did not change for nearly a decade. But

trade with the outside world is conducted in con-

vertible currencies, their volumes then translated

into valyuta rubles at an arbitrary, overvalued rate

for the statistics. Prices charged to or by COMECON

partners were determined in many different ways,

all subject to negotiation and dispute. Some effort

was made during the 1970s to calculate a more ef-

ficient pattern of foreign trade for investment pur-

poses, but in practice these calculations were little

applied.

Given the shortage of foreign currency and un-

derdeveloped trading facilities, Soviet trade corpo-

rations often engaged in “counterpart-trade,” a

kind of barter, where would-be western sellers were

asked to take Soviet goods in return for possible re-

sale. For instance, the sale of large-diameter gas

pipes for West European customers would be re-

paid in gas over time. Obviously, these practices

were awkward, and Soviet leaders tried a number

of organizational measures to interest producers in

increased exports, with little success.

One of the changes instituted under Mikhail

Gorbachev’s leadership was permission for Soviet

enterprises to deal directly with foreign suppliers

and customers. Given the short time perestroika

had to work, it is impossible to tell whether these

direct ties alone would have improved Soviet pen-

etration of choosy markets in the developed world.

After all, Soviet manufactures suffered from poor

design, unreliability, and insufficient incentives, as

well as substandard distribution and service.

During the years immediately after the disso-

lution of the Soviet Union, the Russian ruble be-

came convertible for trade and tourist purposes, but

exporters were required to rebate part of their earn-

ings to the state for repayment of foreign debts.

Further handicapping Russian exporters was the

appreciating real rate of exchange, owing to con-

tinued inflation. The IMF also supported the over-

valued ruble. By 1996 the ruble became fully

convertible. All this made dollars cheap for Rus-

sians to accumulate and stimulated capital flight

estimated at around $20 billion per year through-

out the 1990s. It also made imports of food and

luxuries unusually inexpensive, while making

Russian exports uncompetitive. What is more, the

former East European CMEA partner countries and

most Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

members now preferred to trade with the advanced

western countries, rather than Russia. When in

mid-1998 the government could no longer defend

the overvalued ruble, it accepted a sixty percent de-

preciation to eliminate the large current account

deficit in the balance of payments. This stimulated

a recovery of Russian industry, particularly those

firms producing import substitutes. Russian ex-

ports of oil and gas (which furnish about one-third

of tax revenues) also recovered during the late

1990s. Rising energy prices likewise allowed the

government to accumulate foreign exchange re-

serves, pay off much of its foreign debt, and fi-

nance still quite extensive central government

operations. However, absent private investment,

prospects for diversifying Russian exports beyond

raw materials and arms were still unclear in the

early twenty-first century.

See also: COUNCIL FOR MUTUAL ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE;

ECONOMIC GROWTH, IMPERIAL; ECONOMIC GROWTH,

SOVIET; FOREIGN DEBT; TRADE ROUTES; TRADE

STATUTES OF 1653 AND 1667

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Erickson, P.G., and Miller, R.S. (1979). “Soviet Foreign

Economic Behavior: A Balance of Payments Perspec-

tive.” In Soviet Economy in a Time of Change: A Com-

pendium of Papers, U.S. Congress, Joint Economic

Committee, 3 vols. Washington, DC: U.S. Govern-

ment Printing Office. 2:208-243.

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert. (1999). Compara-

tive Economic Systems, 6th ed. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin.

FOREIGN TRADE

517

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Holzman, Franklyn D. (1974). Foreign Trade under Cen-

tral Planning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Kaser, Michael. (1969). “A Volume Index of Soviet For-

eign Trade.” Soviet Studies 20(4):523–526.

Nove, Alec. (1986). The Soviet Economic System, 3d ed.

Boston: Allen & Unwin.

Wiles, Peter. (1968). Communist International Economics.

Oxford: Blackwell.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

FRANCE, RELATIONS WITH

If the first official contact between France and Rus-

sia was established in 1049, when the daughter of

Yaroslav, prince of Kiev, married Henri, King of

France, bilateral relations were established with the

treaty of friendship signed in 1613 by King Louis

XIII and Tsar Mikhail Fyodorovich. Since then, cul-

tural exchanges regularly expanded, most notably

during the reigns of Peter the Great and Elizabeth.

However, on political and economic grounds, the

exchanges remained thus: England retained pri-

macy in Russian foreign trade throughout the sev-

enteenth and eighteenth centuries; and on the

diplomatic scene, despite common geopolitical in-

terests, France and Russia were quite often the vic-

tims of mutual hostile stereotypes. In 1793,

embittered by France’s radical revolution, Cather-

ine II broke all diplomatic relations with the revo-

lutionary state; and in 1804, despite the treaty of

nonaggression concluded in 1801 with Napoleon,

Alexander I joined the Third Coalition to defeat the

“usurper,” his political ambitions, and his expan-

sionism. The war against Napoleon (1805–1813)

was a national disaster, marked by several cruel de-

feats and by the fire of Moscow in 1812, but

Alexander’s victory, marked by his entrance into

Paris in March 1814, gave him a decisive role dur-

ing the Congress of Vienna.

The second half of the nineteenth century

brought a major change in Russian-French rela-

tions. If France took part in the humiliating Crimean

War in 1854–1856, during the late 1860s recon-

ciliation began to take place and, in 1867 and 1868,

the Russian Empire participated in the universal ex-

hibitions organized in Paris. Political and military

concerns motivated a decisive rapprochement dur-

ing the last third of the century: France, trauma-

tized by the loss of the provinces of Alsace and

Lorraine, desperately needed an ally against Bis-

marck’s Prussia, while for Alexander III’s Russia,

the goal was to gain an ally against the Austro-

Hungarian Empire, which opposed the Russian

pan-Slavic ambitions in the Balkans. In December

1888, the first Russian loan was raised in Paris and

three years later, in August 1891, the two coun-

tries concluded a political alliance, followed by a

military convention in December 1893. To sanctify

the rapprochement, Tsar Nicholas II visited France

three times, in October 1896, September 1901, and

July 1909; and in July 1914, President Poincaré

visited Russia to reinforce the alliance on the eve of

World War I.

The October 1917 Revolution killed these priv-

ileged links. The Bolsheviks opted for a peace with

no annexing and no indemnity—and refused to rec-

ognize the tsarist loans. As a result, the French

state felt deceived, and in December 1917, it broke

relations with Russia and engaged instead in a

struggle against it. In the spring of 1918, France

organized the unloading of forces to support the

White Guard and took part in the Polish war

against Russia (May–October 1920). However,

these interventions failed to overthrow the Soviet

regime and, by the end of 1919, French diplomacy

opted for a policy of containment against the ex-

pansion of communism. By that time, French-

Soviet contacts were reduced: the French presence

in the USSR was limited to the settlement of a small

group of radical intellectuals and to the visits of

French Communists; similarly, there was no offi-

cial Soviet presence in France, although communist

intellectuals and artists continued actively promot-

ing Soviet interests and values.

In 1924 Edouard Herriot, chief of the French

government, decided to recognize the USSR. While

he had no illusion about the authoritarian nature

of the Soviet regime, he thought that France could

no longer afford to ignore such an important coun-

try politically and that the signing of the Treaty of

Rapallo in 1922 could be dangerous. Therefore, for

geopolitical reasons, he chose to reestablish diplo-

matic relations.

This decision gave rise to a rapid growth of eco-

nomic, commercial, and cultural exchanges. In par-

ticular, Soviet artists became increasingly present

in France: Maxim Gorky and Ilya Ehrenburg, for

example, became brilliant spokesmen for the So-

cialist literature. However, this improvement was

a fragile one and remained subject to diplomatic

turbulences, due to Fascism and Nazism. Foreign

FRANCE, RELATIONS WITH

518

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Commissar Maxim Litvinov tried to bring the USSR

closer to France and England, but French hesitation,

demonstrated by the ambivalent French-Soviet

treaty concluded in May 1935 and the lack of

strong reaction to the Spanish Civil War, led Josef

Stalin to conclude an alliance with Adolf Hitler in-

stead. And on August 23, 1939, the conclusion of

the Soviet-German Pact sanctified the collapse of

the Soviet-French entente.

Bilateral relations were reestablished during

World War II. In September 1941, three months

after the beginning of the German invasion of the

Soviet Union, Stalin decided to recognize General

Charles de Gaulle officially as the “Chief of Free

France”; in December 1944 in Moscow, de Gaulle

and Stalin signed a treaty of alliance and mutual

assistance. However, the Cold War, which began

to spread over Europe in 1946, had deep conse-

quences for Soviet-French relations, and in 1955

the Soviet state denounced the treaty of 1944.

In 1956 Nikita Khrushchev’s proclaimed de-

Stalinization was favorably received by French

diplomacy, and in the same year the head of the

French government, Guy Mollet, made a trip to the

USSR. This trip reestablished contacts and led to a

protocol on cultural exchanges. But from 1958 on,

de Gaulle’s return to power brought a new dynamic

to relations with Moscow. De Gaulle wished to en-

courage “détente.” In his view, this would restore

France’s international significance. In June 1966,

he signed several important bilateral agreements

with the USSR. Two committees were designed to

improve economic cooperation; cooperation was

also planned for space, civil nuclear, and television

programs; and an original form of cooperation

took place in the movie industry.

FRANCE, RELATIONS WITH

519

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

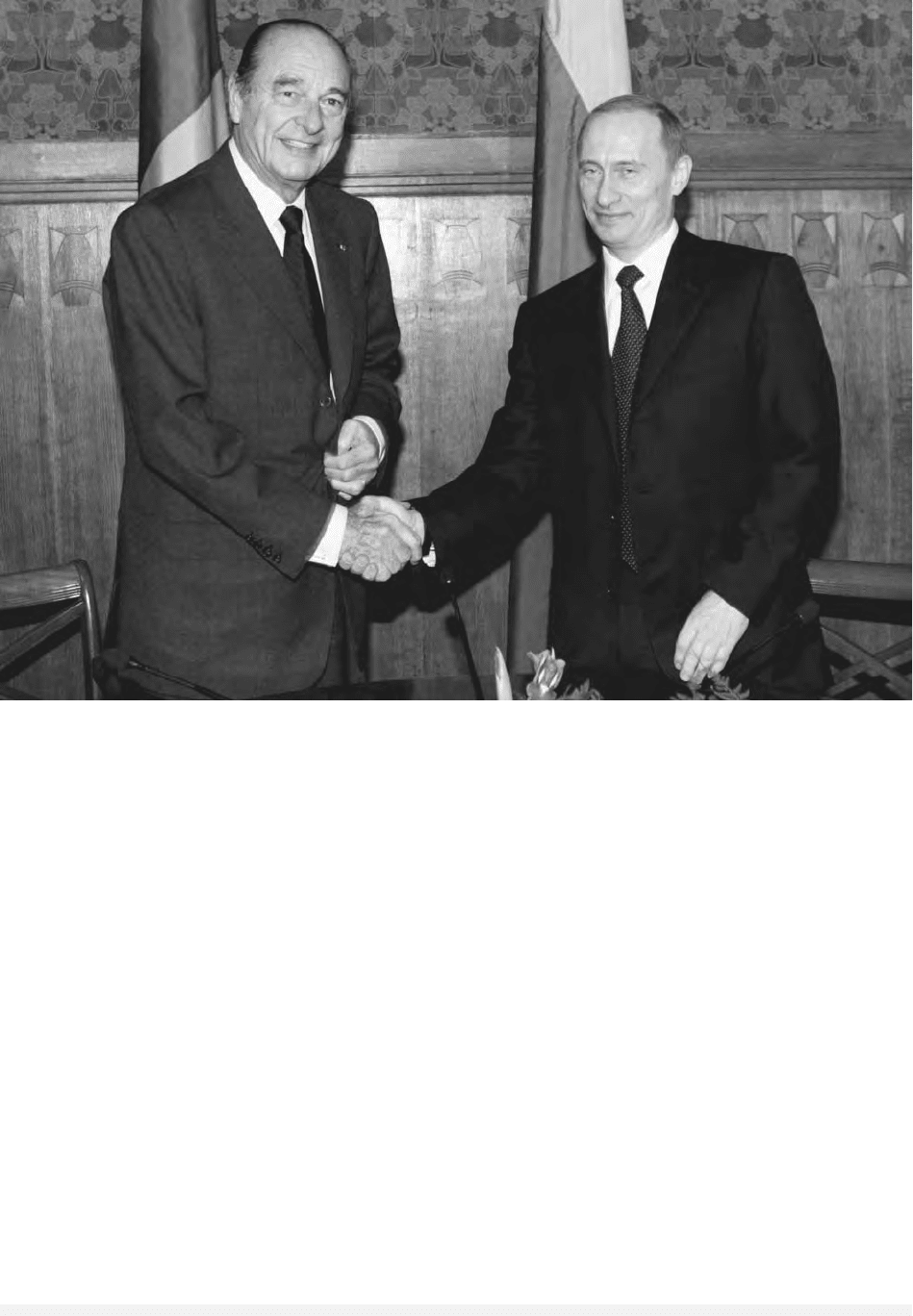

French president Jacques Chirac shakes hands with Russian president Vladimir Putin as they meet in April 2003 to discuss the

situation in Iraq. © AFP/CORBIS

These agreements conferred a distinct flavor on

bilateral relations: in contrast to the American-So-

viet dialogue, which remained limited to strategic

issues, the French-Soviet détente was in essence

more global and covered a wide variety of areas of

mutual interest. Political cooperation, economic and

scientific exchanges, cultural exhibits, performers’

tours, and movie festivals all contributed to build

a bridge between the two countries.

Perestroika brought a new impulse to these re-

lations. When Mikhail Gorbachev introduced dras-

tic changes in March 1985, François Mitterrand’s

diplomacy first hesitated but, after a few months,

provided strong support for the new leader; and in

October 1990, a bilateral treaty of friendship—the

first since 1944—was signed.

The collapse of the USSR imposed another yet

another series of geopolitical and cultural changes

on the new leaders. But these changes had little im-

pact on the long-lasting structural bonds forged

with France through the centuries.

See also: FRENCH INFLUENCE IN RUSSIA; FRENCH WAR OF

1812; NAPOLEON I; POLISH-SOVIET WAR; TILSIT, TREATY

OF; WORLD WAR I; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Shlapentokh, Dmitry. (1996). The French Revolution in

Russian Intellectual Life, 1865–1905. Westport, CT:

Prager.

M

ARIE

-P

IERRE

R

EY

FREE ECONOMIC SOCIETY

The Free Economic Society for the Encouragement

of Agriculture and Husbandry, established in 1765

to consider ways to improve the rural economy of

the Russian Empire, became a center of scientific re-

search and practical activities designed to improve

agriculture and, after the emancipation of the serfs

in 1861, the life of the peasantry. “Free” in the sense

that it was not subordinated to any government

department or the Academy of Sciences, the soci-

ety served as a bridge between science, agriculture,

and reform until shut down during World War I.

It sponsored a wide variety of research in the nat-

ural and social sciences as well as essay competi-

tions, publishing reports and essays in Transactions

of the Free Economic Society (comprising 280 volumes

by 1915), and nine other periodicals.

Founded under the sponsorship of Catherine

the Great, who provided funds for a building and

library, as well as a reformist agenda influenced by

physiocratic ideas, the society brought together no-

ble landowners, government officials, and scholars

to study and disseminate information on advanced

methods of agriculture and estate management,

particularly as practiced abroad. Papers were pre-

sented on rural economic activities, new technolo-

gies, and economic ideas that could be applied to

Russia. Young men were sent abroad to study

agronomy. At the initiative of Catherine, the soci-

ety’s first essay competition examined the utility

of serfdom for the commonweal, but the winning

essay, which opposed serfdom, was ignored.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the

society’s membership came to include more sci-

entists, professionals, and officials, and fewer

landowners. Its work focused on discussion of ad-

vanced ideas in agronomy, medicine, and the devel-

oping sciences of chemistry and biology. After 1830

the society concentrated on practical applications of

technology to agriculture. Among its most impor-

tant projects were research on the best varieties of

plants to grow on Russian soil, efforts to improve

crop yields and sanitary measures, and the intro-

duction of smallpox vaccination into rural areas.

After the accession of Alexander II in 1855, the

society threw itself into reform efforts and greatly

expanded its activities. It offered popular lectures

on physics, chemistry, and forestry. It entered the

fight against illiteracy and in 1861 established a

committee to study popular education. It supported

research on soil science, agricultural economics,

demography, and rural sociology, and carried out

systematic geographic studies. To educate the

newly freed peasantry, the society initiated a wide

range of activities, mounting agricultural exhibits,

establishing experimental farms, encouraging the

use of chemical fertilizer and industrial crops, pro-

moting scientific animal husbandry and beekeep-

ing, and expanding its efforts to vaccinate the

peasantry against smallpox. As part of its educa-

tional mission, the society published popular works

on agriculture and distributed millions of pam-

phlets and books free of charge.

Increasingly, as the society became a forum for

progressive economic thought critical of govern-

ment policy toward the peasantry, its work took

on political dimensions. The government revoked

its charter in 1899, ordering it to confine its activ-

ities to agricultural research. Nonetheless, in 1905

the society supported the election of a constitu-

FREE ECONOMIC SOCIETY

520

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tional assembly and after 1907 published surveys

of peasant opinion on the land reforms proposed

by Interior Minister Peter Stolypin that were im-

plicitly critical of government policy. During World

War I the tsarist government closed down the so-

ciety because of its oppositional stance, and the new

Soviet government formally abolished it in 1919.

See also: AGRARIAN REFORMS; AGRICULTURE; MOSCOW

AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY; STOLYPIN, PETER ARKADIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Pratt, Joan Klobe. (1983). “The Russian Free Economic

Society, 1765–1915.” Ph.D. diss., University of Mis-

souri.

Pratt, Joan Klobe. (2002). “The Free Economic Society

and the Battle Against Smallpox: A ‘Public Sphere’

in Action.” Russian Review 61:560–578.

Vucinich, Alexander. (1963). Science in Russian Culture.

Vol. 1: A History to 1860. Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press.

Vucinich, Alexander. (1970). Science in Russian Culture.

Vol. 2: 1861–1970. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univer-

sity Press.

C

AROL

G

AYLE

W

ILLIAM

M

OSKOFF

FREEMASONRY

Freemasonry came to Russia as part of the eigh-

teenth–century expansion that made the craft a

global phenomenon. Although at first it was one

of several social institutions, including salons, so-

cieties, and clubs, that made their way to Russia in

the course of Westernization, Freemasonry soon

acquired considerable importance, evolving into a

widespread, variegated, and much vilified social

movement.

Despite the legends that attributed the origins

of Russian Freemasonry to Peter the Great (who

purportedly received his degree from Christopher

Wren), the first reliable evidence places the begin-

nings of the craft in Russia in the 1730s and early

1740s. The movement expanded in the latter half

of the eighteenth century, especially between 1770

and 1790, when more than a hundred lodges were

created in St. Petersburg, Moscow, and the provinces.

Freemasonry was an important element of the

Russian Enlightenment and played a central role in

the evolution of Russia’s public sphere and civil

society. The lodges were self-governed and open

to free men (but not women) of almost every

nationality, rank, and walk of life, with the no-

table exception of serfs. While many lodges were

nothing but glorified social clubs, there were nu-

merous brethren who saw themselves as on a mis-

sion to reform humankind and battle Russia’s

perceived “barbarity” by means of charity and self-

improvement. They regarded the lodges as havens

of righteousness and nurseries of virtue in a de-

praved world.

The history of Russian Freemasonry followed

a tortuous path. Most of the lodges, especially

in the provinces, were short–lived, and Russian

Freemasonry was very fragmented. Some lodges

were subordinated to the Grand Lodge of England;

others belonged to the Swedish Rite, the Strict Ob-

servance, or some other jurisdiction. Contempo-

raries made a distinction between Freemasonry

proper and Martinism, a mystical strand in the

movement that claimed the famous mystic Claude

Saint–Martin as its founder. A group of Moscow

Rosicrucians headed by Johann–Georg Schwarz

and Nikolai Ivanovich Novikov were the most im-

portant Martinists. Often referred to as “Novikov’s

circle,” they enjoyed close ties with the university,

the government, and even the local diocese and ini-

tiated numerous educational and charitable initia-

tives, such as the Friendly Learned Society, the

Typographical Company, and the Philological Sem-

inary. Novikov’s circle was an important episode

in the history of the Russian Enlightenment. Its ac-

tivities, however, came to an end in 1792, when

Novikov was arrested, interrogated, and sentenced

to life in prison.

Many aspects of the so-called Novikov affair

are still unclear. The government of Catherine II

may have had political motives for arresting

Novikov, given the Rosicrucians’ ties to foreign

powers as well as to the future Emperor Paul I and

his entourage. The affair may also, in large part,

have been caused by the fear of occult secret soci-

eties and anti–Masonic sentiment that was spread-

ing through Europe. Anti–Masonry later became

an important political factor in imperial and post-

Soviet Russia.

Russian Freemasonry enjoyed a brief period of

relatively unhampered existence in the eighteenth

and early nineteenth centuries. The craft counted

among its members practically every politician,

military leader, and intellectual of note, including

Mikhail Kutuzov and Alexander Pushkin; many of

the Decembrists belonged to the Astrea lodge in St.

Petersburg. After 1822, when Alexander I imposed

FREEMASONRY

521

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

a ban on all secret societies, the situation changed.

The ban, confirmed by Nicholas I in 1826, signi-

fied the official end of Freemasonry, although some

clandestine lodges continued to operate, particu-

larly during a brief revival on the eve of World War

I. Freemasonry was again outlawed in Soviet Rus-

sia in the early 1920s. The ban ended in the 1990s,

when the French National Grand Lodge established

lodges in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Voronezh,

and chapters of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish

Rite were also organized.

See also: CATHERINE II; ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT OF;

NOVIKOV, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH; PAUL I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Smith, Douglas. (1999). Working the Rough Stone: Freema-

sonry and Society in Eighteenth-Century Russia.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

O

LGA

T

SAPINA

FRENCH INFLUENCE IN RUSSIA

The first real manifestations of the influence of

France in Russia date from Russia’s first political

opening toward Europe, undertaken by Peter the

Great (r. 1682–1725) and further advanced by

Catherine II (r. 1762–1796). In the first instance,

this influence was cultural. The adoption of the

French language as the language of conversation

and correspondence by the nobility encouraged ac-

cess to French literature. The nobility’s preference

for French governesses and tutors contributed to

the spread of French culture and educational meth-

ods among the aristocracy. At the beginning of the

nineteenth century, the Russian nobility still pre-

ferred French to Russian for everyday use, and were

familiar with French authors such as Jean de la

Fontaine, George Sand, Eugene Sue, Victor Hugo,

and Honoré de Balzac.

The influence of France was equally strong in

the area of social and political ideas. Catherine II’s

interest in the writings of the philosophers of

the Enlightenment—Baron Montesquieu, Jean Le

Rond d’Alembert, Voltaire, and Denis Diderot—

contributed to the spread of their ideas in Russia

during the eighteenth century. The empress con-

ducted regular correspondence with Voltaire, and

received Diderot at her court. Convinced that it was

her duty to civilize Russia, she encouraged the

growth of a critical outlook and, as an extension

of this, of thought regarding Russian society and

a repudiation of serfdom, which had consequences

following her own reign.

The support of Catherine II for the spirit of the

Enlightenment was nonetheless shaken by the

French Revolution of 1789. It ceased entirely with

the execution of King Louis XVI (January 1793).

The empress was unable to accept such a radical

challenge to the very foundations of autocratic rule.

From the close of her reign onward, restrictions on

foreign travel increased, and contacts were severely

curtailed. Despite this change, however, liberal ideas

that had spread during the eighteenth century con-

tinued to circulate throughout Russia during the

nineteenth, and the French Revolution continued to

have a persistent influence on the political ideas of

Russians. When travel resumed under Alexander I

(ruled 1801–1825), Russians once again began to

travel abroad for pleasure or study. This stimulated

liberal ideas that pervaded progressive and radical

political thought in Russia during the nineteenth

century. The welcome that France extended to po-

litical exiles strengthened its image as a land of lib-

erty and of revolution.

During the nineteenth century, travel in France

was considered a form of cultural and intellectual

apprenticeship. Study travel abroad by Russians, as

well as trips to Russia by the French, shared a com-

mon cultural space, encouraging exchanges most

notably in the areas of fine arts, sciences, and teach-

ing. Because they shared geopolitical interests vis à

vis Germany and Austria-Hungary, France and

Russia were drawn together diplomatically and eco-

nomically after 1887. This resulted, in December

1893, in the ratification of a defensive alliance, the

French-Russian military pact. At the same time,

French investment capital helped finance the mod-

ernization of the Russian economy. Between 1890

and 1914, numerous French industrial and bank-

ing houses established themselves in Russia. French

and Belgian capital supplied the larger part of the

flow of investment funds, the largest share of

which went into mining, metallurgy, chemicals,

and especially railroads. The largest French banks,

notably the Crédit Lyonnais, made loans to or in-

vested in Russian companies. Public borrowing by

the Russian state, totaling between eleven and

twelve billion gold francs, was six times greater

than direct investment on the part of the French.

On the eve of 1914, there were twelve thou-

sand French nationals in Russia. Forty consuls were

in the country looking out for French interests.

French newspapers had permanent correspondents

FRENCH INFLUENCE IN RUSSIA

522

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY