Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Finland, like the other Scandinavian states, devel-

oped a social-democratic welfare state, and Finns

enjoyed one of the highest standards of living in

the world.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, Finland and

Russia signed a new treaty in 1992, which ended

the “special relationship” between the two states.

Trade ties have suffered because of Russia’s eco-

nomic collapse, and Finns increasingly have looked

to the West for economic relationships. Finland

joined the European Union in 1995, and enjoys close

ties with the Baltic states, particularly Estonia.

See also: ESTONIA AND ESTONIANS; FINNS AND KARE-

LIANS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST; NYSTADT,

TREATY OF; SOVIET-FINNISH WAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allison, Roy. (1985). Finland’s Relations with the Soviet

Union, 1944–1984. London: Macmillan.

Kirby, David G., ed. (1975). Finland and Russia,

1808–1920: From Independence to Autonomy. London:

Macmillan.

Kirby, David G. (1979). Finland in the Twentieth Century.

London: Hurst.

Singleton, Fred, and Upton, Anthony F. (1998). A Short

History of Finland. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Tanner, Vaino. (1957). The Winter War: Finland Against

Russia, 1939–1940. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univer-

sity Press.

P

AUL

J. K

UBICEK

FINNS AND KARELIANS

Finns, Karelians (in Karelian Republic and eastern

Finland), Izhorians (Ingrians) and Ingrian Finns

(around St. Petersburg), Vepsians (southeast of St.

Petersburg), near-extinct Votians (southwest of St.

Petersburg), and Estonians speak mutually semi-

intelligible Finnic languages. Novgorod absorbed

many of them during the thirteenth century, with-

out formal treaties. After defeating the Swedes and

taking territory that included the present St. Pe-

tersburg, tsarist Russia subjugated all these peo-

ples. Finns, Ingrian Finns, and most Estonians were

Lutheran, while Karelians, Vepsians, Izhorians, and

Votians were Greek Orthodox. Livelihood has ex-

tended from traditional forest agriculture to urban

endeavors.

Finland and Estonia emerged as independent

countries by 1920, while Karelia became an au-

tonomous oblast (1920) and soon an Autonomous

Soviet Socialist Republic (1923). Deportations, im-

migration, and other means of russification have

almost obliterated the Izhorians, while reducing

the Karelians, Finns, and Vepsians to 13 percent of

Karelia’s population (103,000 out of 791,000, in

1989). Altogether, the Soviet 1989 census recorded

131,000 Karelians (23,000 in Tver oblast), 18,000

Finns, and 6,000 Vepsians (straddling Karelia and

the Leningrad and Vologda oblasts).

Karelia occupies a strategic location on the rail-

road to Russia’s ice-free port of Murmansk on the

Arctic Ocean. Much of the crucial American aid to

the Soviet Union during World War II used this

route. The Karelian Isthmus, seized by Moscow

from Finland during that war, is not part of the

Karelian republic, which briefly (1940 to 1956) was

upgraded to a Karelo-Finnish union republic so as

to put pressure on Finland.

The earliest surviving written document in any

Finnic language is a Karelian thunder spell written

on birch bark with Cyrillic characters. Karelia con-

tributed decisively to the world-famous Finnish

epic Kalevala. Finnish dialects gradually mutate to

northern and western Karelian, to Aunus and Lu-

dic in southern Karelia, and on to Vepsian. Given

such a continuum, a common Karelian literary lan-

guage has not taken root, and standard Latin-script

Finnish is used by the newspaper Karjalan Sanomat

(Karelian News) and the monthly Karjala (Karelia).

A Vepsian periodical, Kodima (Homeland), uses

both Vepsian (with Latin script) and Russian. Only

40,000 Karelians in Karelia and 22,000 elsewhere

in the former Soviet Union consider Karelian or

Finnish their main language. Among the young,

russification prevails.

Karelia is an “urbanized forest republic” where

agriculture is limited and industry ranges from

lumber and paper to iron ore and aluminum. The

capital, Petrozavodsk (Petroskoi in Karelian), in-

cludes 34 percent of Karelia’s entire population.

Ethnic Karelians have little say in political and eco-

nomic management. Hardly any of the republic

government leaders or parliament members speak

Karelian or Finnish. The cultural interests of the in-

digenous minority are voiced by Karjalan Rahva-

han Liitto (Union of the Karelian People), the

FINNS AND KARELIANS

503

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Vepsian Cultural Society, and the Ingrian Union

for Finns in Karelia.

Economic and cultural interactions with Fin-

land, blocked under the Soviet rule, have revived.

Karelia’s future success depends largely on how far

a symbiosis with this more developed neighboring

country can reach.

See also: FINLAND; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET; NA-

TIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST; NORTHERN PEOPLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Eskelinen, Heikki; Oksa, Jukka; and Austin, Daniel.

(1994). Russian Karelia in Search of a New Role. Joen-

suu, Finland: Karelian Institute.

Kurs, Ott. (1994). “Indigenous Finnic Population of

North-west Russia.” GeoJournal 34(4):443–456.

Taagepera, Rein. (1999). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the

Russian State. London: Hurst.

R

EIN

T

AAGEPERA

FIREBIRD

The Firebird (Zhar–ptitsa) is one of the most color-

ful legendary animal figures of Russian magical

tales (fairy tales). With golden feathers and eyes

like crystals, she is a powerful source of light, and

even one of her feathers can illuminate a whole

room. Sometimes she functions as little more than

a magical helper who flies the hero out of danger;

in other tales her feather and she herself are highly

desired prizes to be captured. “Prince Ivan, the Fire-

bird, and the Gray Wolf” depicts her coming at

night to steal golden apples from a king’s garden

and becoming one object of a heroic quest by the

youngest prince, Ivan. Helped by a gray wolf, he

ends up with the Firebird as well as a noble steed

with golden mane and golden bridle and Princess

Yelena the Fair.

The tales became the narrative source for the

first of two famous folklore ballets composed by

Igor Stravinsky under commission from Sergei Di-

aghilev and his Ballets Russes. L’Oiseau de feu, with

choreography by the noted Russian Michel Fokine,

premiered at the Paris Opera on June 25, 1910,

with great success and quickly secured the young

Stravinsky’s international reputation. Like his

Petrushka that followed it, The Firebird impressed

audiences with the colorfulness of both story and

music and with its bold harmonic innovations. The

two ballets also helped spread awareness of Rus-

sia’s rich folk culture beyond its borders.

See also: BALLET, FOLKLORE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Guterman, Norbert, tr. (1973). Russian Fairy Tales, 2d

ed. New York: Pantheon Books.

Taruskin, Richard. (1996). Stravinsky and the Russian

Traditions: A Biography of the Works through Mavra.

2 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press.

N

ORMAN

W. I

NGHAM

FIRST SECRETARY, CPSU See GENERAL SECRETARY.

FIVE-HUNDRED-DAY PLAN

Proposals for reform of the Soviet economic sys-

tem began to emerge during the 1960s, and some

concrete reforms were introduced. All of these ef-

forts, such as Alexei Kosygin’s reforms in 1965,

the new law on state enterprises in 1987, and the

encouragement of cooperatives in 1988, basically

involved tinkering with details. They did not touch

the main pillars of the Soviet economy: hierarchi-

cal command structures controlling enterprise ac-

tivity, detailed central decision-making about

resource allocation and production activity, and

fixed prices set by the government. The need for

reform became ever more obvious in the “years of

stagnation” under Leonid Brezhnev. When Mikhail

Gorbachev came to power in 1985, reform pro-

posals became more radical, culminating in the

formulation of the Five-Hundred-Day Plan, put to-

gether at the request of Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin

by a group of able and progressive reform econo-

mists headed by Academician Stanislav Shatalin

and presented to the government in September

1990.

The plan fully accepted the idea of a shift to a

market economy, as indicated by its subtitle “tran-

sition to the market,” and laid out a timetable of

institutional and policy changes to achieve the tran-

sition. It described and forthrightly accepted the

institutions of private property, market pricing, en-

terprise independence, competition as regulator,

transformation of the banking system, macroeco-

nomic stabilization, and the need to open the econ-

omy to the world market. It specified a timetable

FIREBIRD

504

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of steps to be taken and provided draft legislation

to undergird the changes. One of its more radical

elements was its acceptance of the desire of the re-

publics for devolution of central power, and it en-

dorsed their right to economic independence. This

feature of the plan was fatal upon its acceptance,

as Gorbachev was not ready to accept a diminu-

tion of central power.

Parallel with the Five-Hundred-Day Plan, a

group in the government worked up an alterna-

tive, much less ambitious, proposal. Gorbachev

asked the economist Abel Aganbegyan to meld the

two into a compromise plan. Aganbegyan’s plan

accepted most of the features of the Five-Hundred-

Day Plan, but without timetables. By then, how-

ever, it was too late. Yeltsin had been elected pres-

ident of the Russian republic and had already

started to move the RSFSR along the path of re-

form envisioned in the Shatalin plan. This was fol-

lowed in August 1991 by the abortive coup to

remove Gorbachev, and in December 1991 by the

breakup of the Union, ending the relevance of the

Five-Hundred-Day Plan to a unified USSR. But its

spirit and much of its content were taken as the

basis for the reform in the Russian republic, and

many of the reformers involved in its formulation

became officials in the new Russian government.

The other republics went their own way and, ex-

cept for the Baltic republics, generally rejected rad-

ical reform.

See also: AGANBEGYAN, ABEL GEZEVICH; COMMAND

ADMINISTRATIVE ECONOMY; KOSYGIN REFORMS;

SHATALIN, STANISLAV SERGEYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aslund, Anders. (1995). How Russia Became a Market

Economy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Yavlinsky, G. (1991). 500 Days: Transition to the Market.

Trans. David Kushner. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

R

OBERT

W. C

AMPBELL

FIVE-YEAR PLANS

Russian economic planning had its roots in the late

nineteenth century when tsarist explorers and en-

gineers systematically found and evaluated the rich

resources scattered all around the empire. Major de-

posits of iron and coal, as well as other minerals,

were well documented when the Bolsheviks turned

their attention to economic development. Initial at-

tention focused on several centers in south Russia

and eastern Ukraine, which were to be rapidly en-

larged. Electric power was the glamorous new in-

dustry, and both Vladimir Lenin and Josef Stalin

stressed it as a symbol of progress.

By 1927 the planners had prepared a huge

three-volume Five-Year Plan, consisting of some

seventeen hundred pages of description and opti-

mistic projection. By 1928 Stalin had won control

of the Communist Party from Leon Trotsky and

other rivals, enabling him to launch Russia on a

fateful new path.

The First Five-Year Plan (FYP) laid out hundreds

of projects for construction, but the Party concen-

trated on heavy industry and national defense. In

Germany Adolf Hitler was already calling for more

“living room.” In a famous 1931 speech Stalin

warned that the USSR only had ten years in which

to prepare against invasion (and he was right).

FIVE-YEAR PLANS

505

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

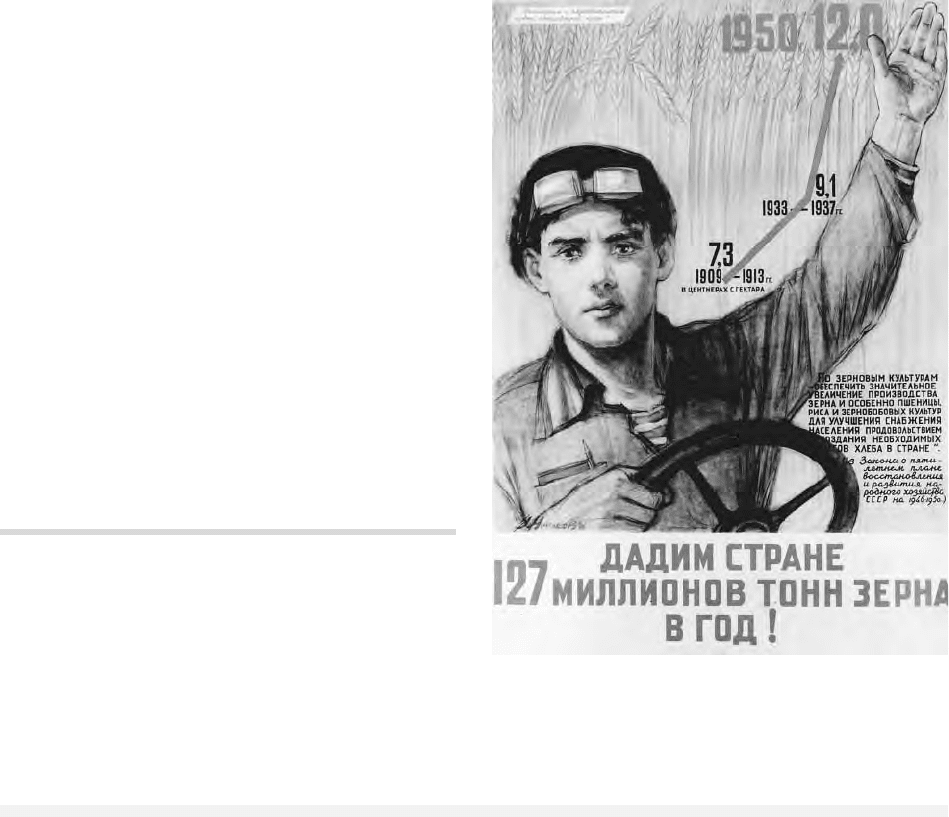

A 1950 propaganda poster urging farmers to fulfill the Five-

Year Plan. The slogan reads, “Let us give to the country 127

million tons of grain per year.” © H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

The First Five-Year Plan was cut short as plan-

ning gave way to confusion. A Second Five-Year

Plan was issued in one volume in 1934, already be-

hind schedule. The planners were learning that one-

year plans were more effective for managing the

economy, leaving the five-year plans to serve as

propaganda documents, especially effective abroad

where the Great Depression seemed to signal the

collapse of capitalism.

The Third Five-Year Plan had limited circula-

tion, and the Fourth was only a pamphlet, issued

as a special edition of the party newspaper, Pravda.

The Nazi invasion, starting June 22, 1941, re-

quired hasty improvisation, using previously pre-

pared central and eastern bases to replace those

quickly overrun by well-equipped German forces.

The Nazis almost captured Moscow in December

1941.

After Soviet forces rallied, wartime planners or-

ganized hasty output increases, drawing on newly

trained survivors of Stalin’s drastic purges. Russian

planners worked uneasily with U.S. and British of-

ficials as the long-delayed second front was opened,

and abundant Lend-Lease supplies arrived.

After the war, improvisation gave way to

Stalin’s grim 1946 Five-Year Plan, which held the

Soviet people to semi-starvation rations while he

rebuilt heavy industry and challenged the United

States in building an atomic bomb.

Fortunately for the Soviet people and the world,

Stalin died in March 1953, and by 1957 Nikita

Khrushchev was able to give Soviet planners a more

humane agenda. The next Five-Year Plan was ac-

tually a seven-year plan with ambitious targets for

higher living standards. Soviet welfare did improve

markedly. However, Khrushchev was diverted by

his efforts to control Berlin and by his ill-fated

Cuban missile adventure. The Party leadership was

furious, but instead of having him executed, they

allowed him to retire.

This brilliant leader’s successors were a dull lot.

The planners returned to previous five-year plan

procedures, which mainly cranked up previous tar-

gets by applying a range of percentage increases.

Growth rates steadily declined.

In 1985 the energetic Mikhail Gorbachev looked

for help from Soviet planners, but the planners

were outweighed by the great bureaucracies run-

ning the system. In a final spasm, the last Five-

Year Plan set overambitious targets like those of

the first such endeavor.

Other Russians contributed greatly by creating

new tools for economic management, especially

Leonid Kontorovich, who invented linear program-

ming; Wassily Leontief, who invented input-

output analysis; and Tigran Khachaturov, who

provided skillful political protection for several

hundred talented economists as they improved

Russian economics. These men rose above the bar-

riers of the Russian planning system and thus de-

serve worldwide respect.

See also: ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; INDUSTRIALIZA-

TION, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergson, Abram. (1964). The Economics of Soviet Planning.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (1990). Soviet Eco-

nomic Structure and Performance, 4th ed. New York:

Harper & Row.

Hunter, Holland, and Szyrmer, Janusz M. (1992). Faulty

Foundations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

H

OLLAND

H

UNTER

FLORENCE, COUNCIL OF

In 1438 Pope Eugenius IV called a church council

to consider reunion of the eastern and western

churches. The Latin and Greek churches had been

drifting apart for centuries and from the year 1054

onward had rarely been in communion with each

other. The sack of the Byzantine capital of Con-

stantinople by the western crusaders made it clear

that they no longer considered the Greeks their co-

religionists and proved to the Greeks of Byzantium

that the Latins were not their brothers in faith. But

by the fifteenth century, with the Ottoman Turks

already in control of most of the territory of the

Byzantine Empire and moving on its capital of Con-

stantinople, reunion of the churches seemed to be

a necessity if the Christian world were to respond

with a united front to the Muslim threat to Eu-

rope.

The council convened in 1439 in the Italian city

of Ferrara and then moved to Florence. Present were

not only the Pope, the cardinals, and many west-

ern bishops and theologians, but also the Byzantine

Emperor John VIII, the Patriarch of Constantino-

ple, Joseph II, the foremost cleric of the eastern

FLORENCE, COUNCIL OF

506

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Christian world, and a number of leading officials

and clergy of the Byzantine world (including a

Russian delegation). The main points of dispute be-

tween the two churches were the legitimacy of a

western addition to the creed (the “filioque”) and

the nature of the church: whether it should be ruled

by the Pope or by all the bishops jointly. After

much discussion and debate, the delegates of the

eastern church, under political pressure, accepted

the western positions on the “filioque” and Papal

supremacy, and reunion of the churches was

solemnly proclaimed.

When the Greek representatives returned home,

however, their decision was greeted with derision.

Church union was never accepted by the masses of

the Eastern Christian faithful. In any case, it be-

came a dead letter with the 1453 Turkish conquest

of Constantinople, renamed Istanbul by the Turks.

When the Greek Isidore, Metropolitan of Kiev and

presiding bishop of the Russian church, returned to

Moscow where he normally resided and proclaimed

the Pope as the head of the church, he was arrested

on the orders of Grand Prince Basil II (“The Dark”)

and then diplomatically allowed to escape to

Poland. In 1448 he was replaced as metropolitan

by a Russian bishop, Jonah, without the consent

of the mother church in Constantinople, which was

deemed to have given up its faith by submitting to

the Pope. From now on, the church of Russia would

be an independent (autocephalous) Orthodox church.

The ramifications of the Council of Florence

were significant. The rejection of its decisions in the

East made it clear that the Roman Catholic and Or-

thodox churches were to be separate institutions,

as they are today. Yet the concept of incorporating

eastern ritual into Catholicism in certain places, a

compromise that evolved at the council, became the

model for the so-called uniate church created in

Polish-governed Ukraine and Belarus in 1596,

whereby the Orthodox church in those lands be-

came part of the Catholic church while retaining

its traditional eastern rites.

See also: BASIL II; METROPOLITAN; UNIATE CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cherniavsky, Michael M. (1955). “The Reception of the

Council of Florence in Moscow.” Church History

24:347–359.

Gill, Joseph. (1961). The Council of Florence. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

G

EORGE

P. M

AJESKA

FOLKLORE

Folklore has played a vital role in the lives of the

Russian people and has exerted a considerable in-

fluence on the literature, music, dance, and other

arts of Russia, including such major nineteenth-

and twentieth-century writers and composers as

Alexander Pushkin, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tol-

stoy, Peter Tchaikovsky, and Igor Stravinsky.

A folklore tradition has existed and flourished

in Russia for many centuries, has been collected and

studied for well more than two hundred years, and

is represented by a variety of large and small gen-

res, including oral epic songs, folktales, laments,

ritual and lyric songs, incantations, riddles, and

proverbs.

A simple explanation for the survival of folk-

lore over such a long period of time is difficult to

find. Some possible reasons can be found in the fact

that the population was predominately rural and

unable to read and write prior to the Soviet era;

that the secular, nonspiritual literature of the folk-

lore tradition was for the most part a primary

source of entertainment for Russians from all

classes and levels of society; or that the Orthodox

Church was unsuccessful in its efforts to repress

the Russian peasant’s pagan, pre-Christian folk be-

liefs and rituals, which over time had absorbed

many Christian elements, a phenomenon com-

monly referred to as “double belief.” The fact that

the Russian peasant was both geographically and

culturally far removed from urban centers and

events that influenced the country’s development

and direction also played a role in folklore’s sur-

vival. And Russia’s geographical location itself was

a significant factor, making possible close contact

with the rich folklore traditions of neighboring

peoples, including the Finns, the nomadic Turkic

tribes, and the non-Russian peoples of the vast

Siberian region.

Evidence of a folklore tradition appeared in

Russian medieval religious and secular works of the

eleventh through the fourteenth centuries, and con-

flicting attitudes toward its existence prior to the

eighteenth century are well documented. The

church considered it as evil, as the work of the devil.

But memoirs and historical literature of the six-

teenth and seventeenth centuries indicate that folk-

lore, folktales in particular, was quite favorably

regarded by many. Ivan the Terrible (1533–1584),

for example, hired blind men to tell stories at his

bedside until he fell asleep. Less than one hundred

FOLKLORE

507

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

years later, however, Tsar Alexis (1645–1676), son

of Peter the Great (1696–1725), ordered the mas-

sacre of practitioners of this and other secular arts.

Royal edict notwithstanding, tellers of tales con-

tinued to bring pleasure to people, and on the rural

estates of noblemen and in high social circles of sev-

enteenth- and eighteenth-century Moscow, skillful

narrators were well rewarded.

The earliest collection of Russian folklore, con-

sisting of some songs and tales, was made during

the seventeenth century by two Oxford-educated

Englishmen: Richard James, chaplain to an English

diplomatic mission in Moscow (1619–1620), and

Samuel Collins, physician to Tsar Alexei (during the

1660s).

The first important collection of Russian folk-

lore by Russians was that of folksongs from the

Ural region, made during the middle of the eigh-

teenth century and published early during the nine-

teenth century. At about the same time a real

foundation was laid for folklore research and schol-

arship in Russia, due largely to the influence of

Western romanticism and widespread increase in

national self-awareness. This movement, repre-

sented in particular by German romantic philoso-

phers and folklorists such as Johann Herder

(1744–1803) and the brothers Grimm (Jacob,

1785–1863; Wilhelm, 1786–1859), was mirrored

in Russia during the early years of the nineteenth

century among the Slavophiles, a group of Rus-

sian intellectuals of the 1830s, who believed in Rus-

sia’s spiritual greatness and who showed an intense

interest in Russia’s folklore, folk customs, and the

role of the folk in the development of Russian cul-

ture. Folklore now began to be seriously collected,

and among the significant works published were

large collections of Russian proverbs by V. I. Dal

(1801-1872) and Russian folktales by A. N. Afana-

sev (1826-1871).

But the latter part of the nineteenth century

signaled the most significant event in Russian folk-

lore scholarship, when P.N. Rybnikov (1831–1885)

and A.F. Hilferding (Gilferding, 1831–1872) un-

covered a treasury of folklore in the Lake Onega re-

gion of northwestern Russia during the 1860s and

1870s, including a flourishing tradition of oral epic

songs, which up to that time was believed to be al-

most extinct as a living folklore form. This dis-

covery led to a systematic search for folklore that

is still being conducted during the early twenty-

first century.

During the Soviet period folklore was criticized

for depicting the reality of the past and was even

considered harmful to the people. Until the death

of Stalin in 1953 folklore scholarship was under

constant Party supervision and limited in scope, fo-

cusing on social problems and ideological matters.

But folklore itself was recognized as a powerful

means to promote patriotism and advance Com-

munist ideas and ideals, and it became a potent in-

strument in the formation of Socialist culture. New

Soviet versions of folklore were created and made

public through a variety of media—concert hall,

radio, film, television, and tapes and phonograph

records. These new works included contemporary

subject matter: for example, an airplane instead of

the wooden eagle on whose back the hero often

traveled, a rifle for slaying a modern dragon in mil-

itary uniform, or marriage to the daughter of a

factory manager rather than a princess.

FOLKLORE

508

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

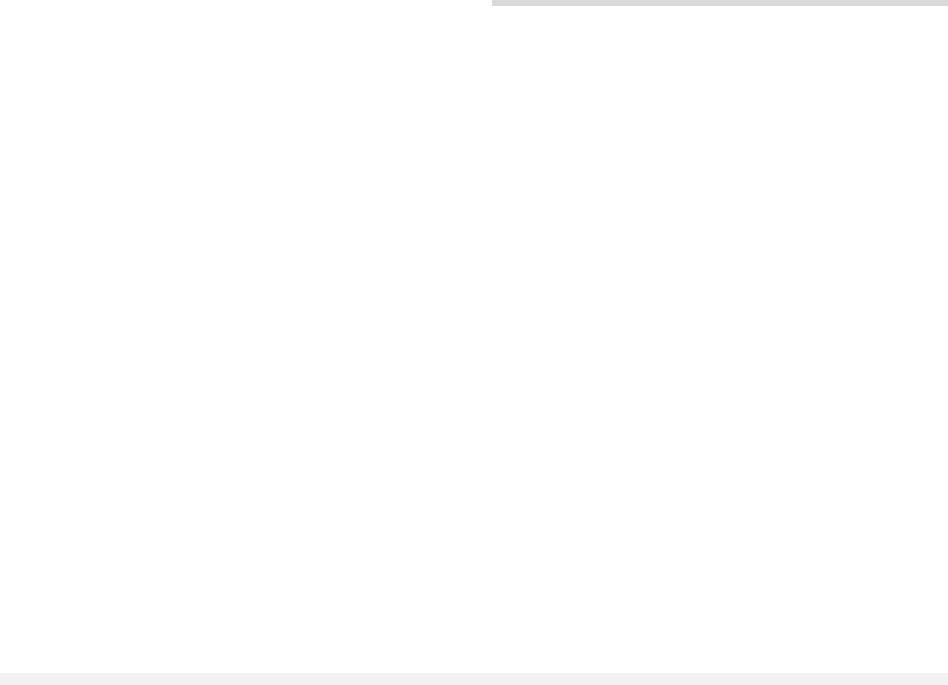

Prince Ivan and the Grey Wolf,

nineteenth-century engraving

after a watercolor by Boris Zvorykin. T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/B

IBLIOTHÈQUE DES

A

RTS

D

ÉCORATIFS

P

ARIS

/D

AGLI

O

RTI

Since the 1970s, Russian folklore has become

free from government control, and the sphere of

study has expanded. During the early twenty-first

century, folklore of the far-flung regions of the for-

mer Soviet Union is being collected in the field.

Many of the older, classic collections of Russian

folklore are being republished, old cylinder record-

ings restored, and bibliographies published, mainly

under the direction of the Folklore Committee of

the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House)

of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in St. Pe-

tersburg and the Folklore Section of the Gorky In-

stitute of World Literature in Moscow.

Among the most important narrative folklore

genres are Russian oral epic songs and folktales,

which provide a rich diversity of thematic and story

material. The oral epic songs are the major genre

in verse. Many of them concern the adventures of

heroes associated with Prince Vladimir’s court in

Kiev in southern Russia; the action in a second

group of epic songs occurs on the “open plain,”

where Russians fight the Tatar invaders; and the

events of a third group of songs take place near the

medieval city of Novgorod in northern Russia. The

stories are made up of themes of feasting, journeys,

and combats; acts of insubordination and punish-

ment; trials of skill in arms, sports, and horse-

manship; and themes of courtship, marriage,

infidelity, and reconciliation. Some popular songs

are about the giant Svyatogor, the Old Cossack Ilya

Muromets, the dragon-slayer Dobrynya Nikitich,

Alyosha Popovich the priest’s son, and the rich

merchant Sadko.

The leading genre in prose, one that is well

known beyond Russia, is the folktale, which in-

cludes tales of various kinds, such as animal and

moral tales, as well as magic or so-called fairy tales,

similar to the Western European fairy tales. Rus-

sian magic or fairy tales often tell a story about a

hero who leaves home for some reason, must carry

out one or several different tasks, encounters many

obstacles along the way, accomplishes all of the

tasks, and gains wealth or a fair maiden in the end.

Among the popular heroes and villains of Russian

folktales are Ivan the King’s son, the witch Baba

Yaga, Ivan the fool, the immortal Kashchey, Grand-

father Frost, and the Firebird.

See also: FIREBIRD; FOLK MUSIC; PUSHKIN HOUSE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Afanasev, Alexander. (1975). Russian Fairy Tales. New

York: Random House.

Bailey, James, and Ivanova, Tatyana. (1998). Russian

Folk Epics. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Beliefs. Armonk,

NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Miller, Frank J. (1990). Folklore for Stalin: Russian Folk-

lore and Pseudofolklore of the Stalin Era. Armonk, NY:

M.E. Sharpe.

Oinas, Felix J. (1985). Essays on Russian Folklore and

Mythology. Columbus, OH: Slavica.

Oinas, Felix J., and Soudakoff, Stephen, eds. (1975). The

Study of Russian Folklore. The Hague: Mouton.

Sokolov, Y.M. (1971). Russian Folklore, tr. Catherine Ruth

Smith. Detroit, MI: Folklore Associates.

P

ATRICIA

A

RANT

FOLK MUSIC

Russian folk music is the indigenous vocal (ac-

companied and unaccompanied) and instrumental

music of the Russian peasantry, consisting of songs

and dances for work, entertainment, and religious

and ritual occasions. Its origins lie in customary

practice; until the industrial era it was an oral tra-

dition, performed and learned without written no-

tation. Common instruments include the domra

(three- or four-stringed round-bodied lute), bal-

alaika (three-stringed triangular-bodied lute), gusli

(psaltery), bayan (accordion), svirel (pennywhistle),

and zhaleyka (hornpipe). Russian folk music in-

cludes songs marking seasonal and ritual events,

and music for figure or circle dances (korovody) and

the faster chastye or plyasovye dances. A related

form, chastushki (bright tunes accompanying hu-

morous or satirical four-line verses), gained rural

and urban popularity during the late nineteenth

century. The sung epic bylina declined during the

nineteenth century, but protyazhnye—protracted

lyric songs, slow in tempo and frequently sorrow-

ful in content and tone—remain popular. Signifi-

cant stylistic and repertoire differences exist among

various regions of Russia.

Russian educated society’s interest in folk mu-

sic began during the late eighteenth century. Nu-

merous collections of Russian folk songs were

published over the next two centuries (notably

N. L. Lvov and J. B. Prác

, Collection of Russian Folk

Songs with Their Tunes, St. Petersburg, 1790). From

the nineteenth century onward, Russian composers

used these as an important source of musical ma-

FOLKLORE

509

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

terial. During the nineteenth century, German

philosopher Johann Herder’s ideas of romantic na-

tionalism and the importance of the folk in deter-

mining national culture inspired interest in and

appreciation of native Russian musical sources, es-

pecially as they reflected notions of national pride.

Mikhail Glinka, for his purposeful use of Russian

folk themes in his 1836 opera A Life for the Tsar, is

considered the founder of the “national” school of

Russian music composition, most famously em-

braced by Mili Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, César

Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-

Korsakov. This designation had more political than

musical significance, as composers not associated

with the national school, such as Peter Tchaikovsky

and Igor Stravinsky, also made use of folk music

in their compositions.

Russian ethnographers of the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries made efforts to record

native folk music in the face of increasing urban-

ization. In 1896 Vasily Andreyev (1861–1918) or-

ganized an orchestra of folk instruments, and in

1911 Mitrofan Piatnitsky (1864–1927) founded a

Russian folk choir. Originally consisting of peasant

and amateur performers, both became well-known

professional ensembles, providing folk music as en-

tertainment for urban audiences.

During the Soviet era folk music had important

symbolic importance as a form genuinely “of the

people.” During the 1930s, state support for so-

cialist realism encouraged study and performance

of folk music. Composers and amateur performers

developed a new “Soviet folk song” that wedded tra-

ditional forms and styles with lyrics praising so-

cialism and the Soviet state. Official support was

demonstrated in the establishment of the Pyatnit-

sky choir and the Russian folk orchestra directed by

Nikolai Osipov (1901–1945) as State ensembles.

Russian folk music became a state-sanctioned per-

formance genre characterized by organized amateur

activities, notated music, academic study, and large

professional performing ensembles that toured in-

ternationally. During the 1970s, Dmitry Pokrovsky

(d. 1996) began a new effort to collect and perform

Russian folk songs and tunes in authentic peasant

village style, with local variations. This revival of

Russian folk music received international attention

as part of the world music movement.

See also: BALALAIKA; FOLKLORE; GLINKA, MIKHAIL; MUSIC;

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV, NIKOLAI ANDREYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, Malcolm Hamrick. (1983). “Native Song and Na-

tional Consciousness in Nineteenth-Century Russian

Music.” In Art and Culture in Nineteenth-Century Rus-

sia, ed. Theofanis George Stavrou. Bloomington: In-

diana University Press.

Miller, Frank J. (1990). Folklore for Stalin: Russian Folk-

lore and Pseudofolklore in the Stalin Era. Armonk, NY:

M.E. Sharpe.

Rothstein, Robert A. (1994). “Death of the Folk Song?”

In Cultures in Flux: Lower-Class Values, Practices, and

Resistance in Late Imperial Russia, ed. Stephen P.

Frank and Mark D. Steinberg. Princeton, NJ: Prince-

ton University Press.

Taruskin, Richard. (1997). Defining Russia Musically.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

S

USANNAH

L

OCKWOOD

S

MITH

FOLKLORE

510

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian peasants playing folk music, early-twentieth-century

postcard. T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/B

IBLIOTHÈQUE DES

A

RTS

D

ÉCORATIFS

P

ARIS

/D

AGLI

O

RTI

FONDODERZHATELI

Literal translation: “fund holders.”

In the Soviet economy, various organizations

were holders and managers of inputs (fondo-

derzhateli). The principal fund holders were min-

istries and regional and local governments. In some

instances, the state executive committees that di-

rected construction organizations and local industry

had fund-holding authority as well. Only fund hold-

ers were legally entitled to allocate funded resources,

the most important of which were allocated by the

State Planning Committee (Gosplan) and the State

Committee for Material Technical Supply (Gossnab).

Fund holders had to estimate input needs and their

distribution among subordinate enterprises. They

were obliged to allocate funds among direct con-

sumers, such as enterprises, plants, and construc-

tion organizations within their jurisdiction. Fund

holders also monitored the use of allocated funds.

Funding (fondirovanie) was the typical form of cen-

tralized distribution of resources for important and

highly “deficit” products. Such centrally allocated

materials were called “funded” (fondiruyumye) com-

modities and were typically distributed among the

enterprises by ministries. Enterprises were not al-

lowed to exchange funded inputs legally. Material

balances and distribution plans among fund holders

were developed by Gosplan and then approved by

the Council of Ministries. The ministries had their

own supply departments that worked with central

supply organizations. The enterprises related input

requirements to their superiors through orders (za-

yavki), which were aggregated by the fund holder.

At each stage of economic planning, requested in-

puts were compared to estimated input needs, and

imbalances were corrected administratively without

the use of prices. The process of allocating funded

resources was characterized by constant bargaining

between fund holders and consumers, where the lat-

ter were required to “defend” their needs.

See also: FUNDED COMMODITIES

P

AUL

R. G

REGORY

FONVIZIN, DENIS IVANOVICH

(1744–1792), dramatist.

Denis Fonvizin, the first truly original Russian

dramatist in the eighteenth century, is best known

for two satirical plays written in prose: The Brigadier-

General (Brigadir) and The Minor (Nedorosl). Brigadir,

written in 1766, was not published until 1786. Ne-

dorosl was first staged in 1783 and published the

following year. Both are considered masterpieces

combining Russian and French comedy.

Like all writers at the time, Fonvizin was born

into a well-to-do family. His father, a strict disci-

plinarian, trained him to become a real “gentleman,”

and became the model for one of the characters—

the father of Mr. Oldwise (Starodum)—in Fonvizin’s

play The Minor. Although thoroughly Russianized,

the family’s ancestor was a German or Swedish

prisoner captured in the Livonian campaigns of Ivan

the Terrible. At Moscow University Fonvizin par-

ticipated actively in theatrical productions. Upon

graduation in 1762 (when Catherine II became em-

press), Fonvizin entered the civil service. In St.

Petersburg, he befriended Ivan Dmitrievsky, a

prominent actor, and began to translate and adapt

foreign plays for him. He wrote minor works, such

as Alzire, or the Americans (1762) and Korion (1764),

but tasted his first real success when Catherine

summoned him to the Hermitage to read his com-

edy The Brigadier to her. In 1769 she then appointed

him secretary to Vice-Chancellor Nikita Panin,

Catherine’s top diplomatic advisor.

Although faithful to the French genre in writ-

ing The Brigadier, Fonvizin was less inspired by

Molière than by the Danish playwright Barin Lud-

vig Holberg, from whose play Jean de France Fon-

vizin’s play was derived. A salon comedy, The

Brigadier attacks the nobility’s corruption and ig-

norance. After reading the play, Panin wrote to

Fonvizin: “I see that you know our customs well,

because the wife of your general is completely fa-

miliar to us. No one among us can deny having a

grandmother or an aunt of the sort. You have writ-

ten our first comedy of manners.” The play also

mocks the Russian gentry’s “gallomania”; without

French rules for behavior “we wouldn’t know how

to dance, how to enter a room, how to bow, how

to perfume ourselves, how to put a hat on, and,

when excited, how to express our passions and the

state of our heart.”

In 1782 Fonvizin finished The Minor. Since it was

unthinkable that these lines could be read aloud to

Catherine, he arranged a performance at Kniper’s

Theater in St. Petersburg with Dmitrievsky as the

character, Mr. Oldwise. The audience, recognizing

the play as original and uniquely Russian, signaled

its appreciation by flinging purses onto the stage.

The play condemns domestic tyranny and false

FONVIZIN, DENIS IVANOVICH

511

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

education, while touching also on larger social ques-

tions, such as serfdom. The play concerns the stu-

pid son in a noble family, the Prostakovs (a play on

the word prostoi or “simple”), who refuses to study

properly but still expects to receive privileges. The

lad’s name—Mitrofan (or Mitrofanushka in the

diminutive)—is now a synonym in Russia for a dolt

or fool. The composition of the family is telling. The

mother, a bully, is obsessed with her son (that he

get enough to eat and marry an heiress). Her brother

resembles a pig more than a man (as his name,

Skotina, suggests). Her husband acts sheepishly; the

nurse spoils the boy; and the boy—wildly selfish and

stupid—beats her. The play’s basic action revolves

around the conflict between the Prostakovs on the

one hand and Starodum and his associates on the

other. The formers’ “coarse bestiality” (as Gogol

termed it) contrasts sharply with the lofty moral-

ity that Starodum and his friends exhibit.

In 1782 Fonvizin’s boss, Count Panin, had a

stroke and summoned Fonvizin to write his Polit-

ical Testament. He instructed the dramatist to

deliver the testament, containing a blunt denunci-

ation of absolute power, to Catherine after Panin’s

death. However, when Panin died the next year,

Catherine impounded all his papers (not to be re-

leased from archives until 1905) and dismissed Fon-

vizin. Pushkin later wrote that Catherine probably

feared him. The playwright’s health declined after

a seizure in 1785, and he died in 1792.

See also: THEATER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fonvizin, Denis Ivanovich, and Gleason, Walter J. (1985).

The Political and Legal Writings of Denis Fonvizin. Ann

Arbor, MI: Ardis.

Levitt, Marcus C. (1995). Early Modern Russian Writers:

Late Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Detroit:

Gale Research.

Moser, Charles A. (1979). Denis Fonvizin. Boston: Twayne.

Raeff, Marc, ed. (1966). Russian Intellectual History: An

Anthology. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

FOOD

Russian food is typically hearty in taste, with mus-

tard, horseradish, and dill among the predominant

condiments. The cuisine is distinguished by the

many fermented and preserved foods necessitated

by the short growing season of the Russian North.

Foraged foods, especially mushrooms, are impor-

tant to Russian diet and culture. The Russians ex-

cel in the preparation of a wide range of fresh and

cultured dairy products; honey is the traditional

sweetener.

Russian cuisine is known for its extensive

repertoire of soups and pies. The national soup

(shchi) is made from cabbage, either salted or fresh.

Soup is traditionally served at the midday meal, ac-

companied by an assortment of small pies, crou-

tons, or dumplings. The pies are filled with myriad

combinations of meat, fish, or vegetables, and are

prepared in all shapes and sizes. The Russian diet

tends to be high in carbohydrates, with a vast ar-

ray of breads, notably dark sour rye, and grains,

especially buckwheat.

Many of Russia’s most typical dishes reflect the

properties of the traditional Russian masonry

stove, which blazes hot after firing and then grad-

ually diminishes in the intensity of its heat. Breads

and pies were traditionally baked when the oven

was still very hot. Once the temperature began to

fall, porridges could cook in the diminishing heat.

As the oven’s heat continued to subside, the stove

was ideal for the braised vegetables and slow-

cooked dishes that represent the best of Russian

cooking.

The Orthodox Church had a profound influ-

ence on the Russian diet, dividing the year into feast

days and fast days. The latter accounted for ap-

proximately 180 days of the year. Most Russians

took fasting seriously, strictly following the pro-

scriptions against meat and dairy products.

From the earliest times the Russians enjoyed al-

coholic beverages, especially mead, a fermented

honey wine flavored with berries and herbs, and

kvas, a mildly alcoholic beverage made from fer-

mented bread or grain. Distilled spirits, in the form

of vodka, appeared only during the fifteenth cen-

tury, introduced from Poland and the Baltic region.

The reforms carried out by Peter I greatly af-

fected Russian cuisine. The most significant devel-

opment was the introduction of the Dutch range,

which relied on a cooktop more than oven cham-

bers and resulted in more labor-intensive cooking

methods. The vocabulary introduced into Russian

over the course of the eighteenth century reveals

influences from the Dutch, German, English, and

ultimately French cuisines. By the close of the eigh-

teenth century, Russia’s most affluent families em-

FOOD

512

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY