Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

history based on the idea of unity of Russia and Eu-

rope. At the opposite pole, national conservative iso-

lationism found its expression in the works of Pyotr

Alexeyev, Pyotr Bicilli, Nikolai Trubetskoy, Pyotr

Savitsky, Lev Karsavin, and other representatives of

the Eurasian movement. The liberal and conserva-

tive nationalist visions of Russian history are still

present in contemporary thought. The liberal para-

digm coined by Andrei Sakharov was preserved in

the writings of Yegor Gaidar, Boris Fyodorov, Grig-

ory Yavlinsky, and others. Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s

vision of Russian history based on Berdyayev’s

legacy is moderately conservative, while Alexander

Dugin and other neo–Eurasians form the extreme

right wing, advocating an isolationist nationalist ap-

proach to Russia’s past and present.

See also: BERDYAYEV, NIKOLAI ALEXANDROVICH; CHAA-

DAYEV, PETER YAKOVLEVICH; DECEMBRIST MOVE-

MENT AND REBELLION; ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT

OF; HEGEL, GEORG WILHELM FRIEDRICH; KARAMZIN,

NIKOLAI MIKHAILOVICH; LOVERS OF WISDOM, THE;

SLAVOPHILES; TOLSTOY, LEO NIKOLAYEVICH; WEST-

ERNIZERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berlin, Isaiah. (1978). Russian Thinkers. London: Hoga-

rth.

Florovsky, Georges. (1979–1987). Ways of Russian The-

ology. 2 vols., tr. Robert L. Nichols. Belmont, MA:

Nordland.

Glatzer-Rosenthal, Bernice, ed. (1986). Nietzsche in Rus-

sia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kline, George. (1968). Religious and Anti-Religious Thought

in Russia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lossky, Nicholas. (1951). History of Russian Philosophy.

New York: International Universities Press.

Pipes, Richard, ed. (1961). The Russian Intelligentsia. New

York: Columbia University Press.

Raeff, Marc. (1966). The Origins of the Russian Intelli-

gentsia: The Eighteenth-Century Nobility. New York:

Harcourt, Brace & World.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas. (1952). Russia and the West in the

Teaching of the Slavophiles: A Study of Romantic Ide-

ology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walicki, Andrzej. (1979). A History of Russian Thought

from the Enlightenment to Marxism, tr. Helen An-

drews-Rusiecka. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press.

Zenkovsky, Vasilii. (1953). A History of Russian Philoso-

phy, 2 vols., tr. George L. Kline. New York: Colum-

bia University Press.

B

ORIS

G

UBMAN

IGOR

(d. 945), second grand prince of Kiev, who, like his

predecessor Oleg, negotiated treaties with Constan-

tinople.

Igor, the alleged son of Ryurik, succeeded Oleg

around 912. Soon after, the Primary Chronicle re-

ports, the Derevlyane attempted to regain their in-

dependence from the prince of Kiev. Igor crushed the

revolt and imposed an even heavier tribute on the

tribe. In 915, when the Pechenegs first arrived in Rus,

Igor concluded peace with them, but in 920 he was

forced to wage war. After that, nothing is known

of his activities until 941 when, for unexplained rea-

sons, he attacked Byzantium with 10,000 boats and

40,000 men. His troops ravaged the Greek lands for

several months. However, when the Byzantine army

returned from Armenia and from fighting the Sara-

cens, it destroyed Igor’s boats with Greek fire. In 944

Igor sought revenge by allegedly launching a second

attack. When the Greeks sued for peace, he conceded,

sending envoys to Emperor Romanus Lecapenus to

confirm the agreements that Oleg had concluded in

907 and 911. The treaty reveals that Igor had Chris-

tians in his entourage. They swore their oaths on

the Holy Cross in the Church of St. Elias in Kiev,

while the pagans swore their oaths on their weapons

in front of the idol of Perun. In 945 the Derevlyane

once again revolted against Igor’s heavy-handed

measures; when he came to Iskorosten to collect trib-

ute from them, they killed him. His wife, the es-

teemed Princess Olga from Pskov, then became

regent for their minor son Svyatoslav.

See also: GRAND PRINCE; KIEVAN RUS; PECHENEGS; PRI-

MARY CHRONICLE; RURIKID DYNASTY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Vernadsky, George. (1948). Kievan Russia. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

ILMINSKY, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

(1822–1891), professor of Turkic Languages at

Kazan University and lay Russian Orthodox mis-

sionary, known as “Enlightener of Natives.”

Nikolai Ilminsky gave up a brilliant academic

career to devote himself to missionary work among

ILMINSKY, NIKOLAI IVANOVICH

653

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the non-Russians. He was convinced that only

through the mother tongue and native teachers and

clergy could the nominally baptized and animists

become true Russian Orthodox believers and thus

resist conversion to Islam. This conviction was at

the heart of what became known as the “Ilminsky

System.”

In 1863, while still holding the chair of Turkic

languages at both Kazan University and Kazan

Theological Academy, Ilminsky established the

Kazan Central Baptized-Tatar School, which served

as his showcase and model for non-Russian schools

and whose thousands of graduates spawned nu-

merous village schools. In 1867 Ilminsky founded

the Gurri Brotherhood, which supported the grow-

ing network of native schools, and set up the Kazan

Translating Commission. By 1891 the Commission

had produced 177 titles in over a dozen languages;

by 1904 the Commission had produced titles in

twenty-three languages. For most of the lan-

guages, this required the creation of alphabets,

grammars, primers, and dictionaries. Starting with

the baptized Tatars of the Kazan region, Ilminsky’s

activities extended to the multinational Volga-Ural

area, to Siberia, and to Central Asia. But disciples

carried his system further: Ivan Kasatkin, for ex-

ample, founded the Orthodox Church of Japan.

Ilminsky’s system encountered strong opposi-

tion from Russian nationalists who saw in the

Russian language the “cement of the Empire” and

feared that his approach encouraged national self-

esteem among the minorities. Yet by demonstrat-

ing the fervent piety of his students and above all

stressing that the alternative was defection to Is-

lam, he was able to obtain the backing of power-

ful figures in the government and the Church,

including Konstantin Pobedonostev. Ilminsky even

became a quasi-official advisor on nationality af-

fairs and as such promoted strict censorship, un-

favorable appointments, and restrictive laws for

Muslims and Buddhists.

The impact of Ilminsky’s system on preliterate

nationalities was revolutionary, as these peoples,

equipped with a written language and the begin-

nings of a national intelligentsia, experienced a na-

tional awakening. Such national leaders as the

Chuvash Ivan Yakovlev and the Kazakh Ibrai Al-

tynsarin were Ilminsky’s disciples and protégés,

while Lenin’s father worked closely with Ilminsky

in promoting non-Russian education in Simbirsk

Province. This may explain why Lenin’s national-

ity policy, summarized as “national in form, so-

cialist in content” was remarkably similar to

Ilminsky’s system, which was defended by his sup-

porters as “national in form, Orthodox in content.”

See also: EDUCATION; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST;

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH; TATARSTAN AND

TATARS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dowler, Wayne. (2001). Classroom and Empire: The Poli-

tics of Schooling Russia’s Eastern Nationalities,

1860–1917. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University

Press.

Kreindler, Isabelle. (1977). “A Neglected Source of Lenin’s

Nationality Policy.” Slavic Review 36:86–100.

I

SABELLE

K

REINDLER

IMMIGRATION AND EMIGRATION

To paraphrase the nineteenth-century historian of

Russia, Vasily Klyuchevsky, the history of Russia

is the history of migration. The Kievan polity itself

was founded by Varangian traders in the ninth cen-

tury, then populated by the steady migration and

population growth of Slavic agriculturalists. By the

sixteenth century the attempt to control popula-

tion movement became one of the most important

tasks of the Muscovite state. Serfdom (i.e., elimi-

nation of the right of peasants to move from one

lord to another) was entrenched in the late sixteenth

and early seventeenth centuries by the tsars of

Muscovy in order to ensure that their servitors could

feed their horses and buy sufficient weaponry. Serf-

dom’s logic led to an elaborate system of controls

over movement within the country and of course

precluded any possibility of legal emigration for the

vast majority of the population. The Muscovite

polity also developed mechanisms to prevent the

departure of its servitors and elites. Peasant flight—

often to join the Cossacks in border regions—was

not a negligible phenomenon, and there were sev-

eral exceptional mass emigrations. Most notable

was the departure of an estimated 400,000

Crimean Tatars, Nogai, and Kalmyks in the late

eighteenth century after the annexation of their

lands by the Russian Empire, and another mass em-

igration in the 1850s and 1860s of Adygs,

Cherkess, Nogai, and others after the completion of

the conquest of the Caucasus. But regular yearly

emigration did not occur on a significant scale un-

til the 1860s.

IMMIGRATION AND EMIGRATION

654

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Thus it would be logical to link the first ap-

pearance of steady yearly emigration with the

emancipation of the serfs in 1861. But this rela-

tionship is not so clear. Of the four million emi-

grants from the Russian Empire from 1861 to

1914, less than 3 percent were Russians. The vast

majority were Jews and Germans, neither of which

had been under serfdom. It was probably not serf-

dom so much as the commune, with its systems

of collective responsibility and partible inheritance,

that kept emigration figures so low for Russians.

A massive emigration of Germans began in the

1870s in reaction to the abolition of their exemp-

tion from military conscription and continued due

to the increasingly serious shortage of fertile lands

in the Russian Empire as a result of population

growth. Nearly 1.5 million Jews emigrated from

1861 to 1914, both in reaction to ongoing gov-

ernment repression and pogroms and in order to

take advantage of civic equality and economic

opportunities available in the United States and

elsewhere. The sudden and massive increase in em-

igration also had a great deal to do with the trans-

portation revolution, which brought cheap railroad

and steamship tickets, making intercontinental

travel possible for those of modest means.

While the tsar selectively recruited and encour-

aged immigrants from Europe to serve as soldiers,

technicians, architects, and engineers on a fairly ex-

tensive scale by the sixteenth and seventeenth cen-

turies, the second half of the eighteenth century

was the heyday of immigration to the Russian Em-

pire. Inspired by physiocratic notions that the pop-

ulation is the fundamental source of wealth, and

eager to populate the vast, fertile, untilled south-

ern steppe that they had conquered, empresses

Elizabeth and Catherine created very favorable

conditions for immigrants in the mid-eighteenth

century. These included free grants of land, perma-

nent exemption from military service, temporary

IMMIGRATION AND EMIGRATION

655

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

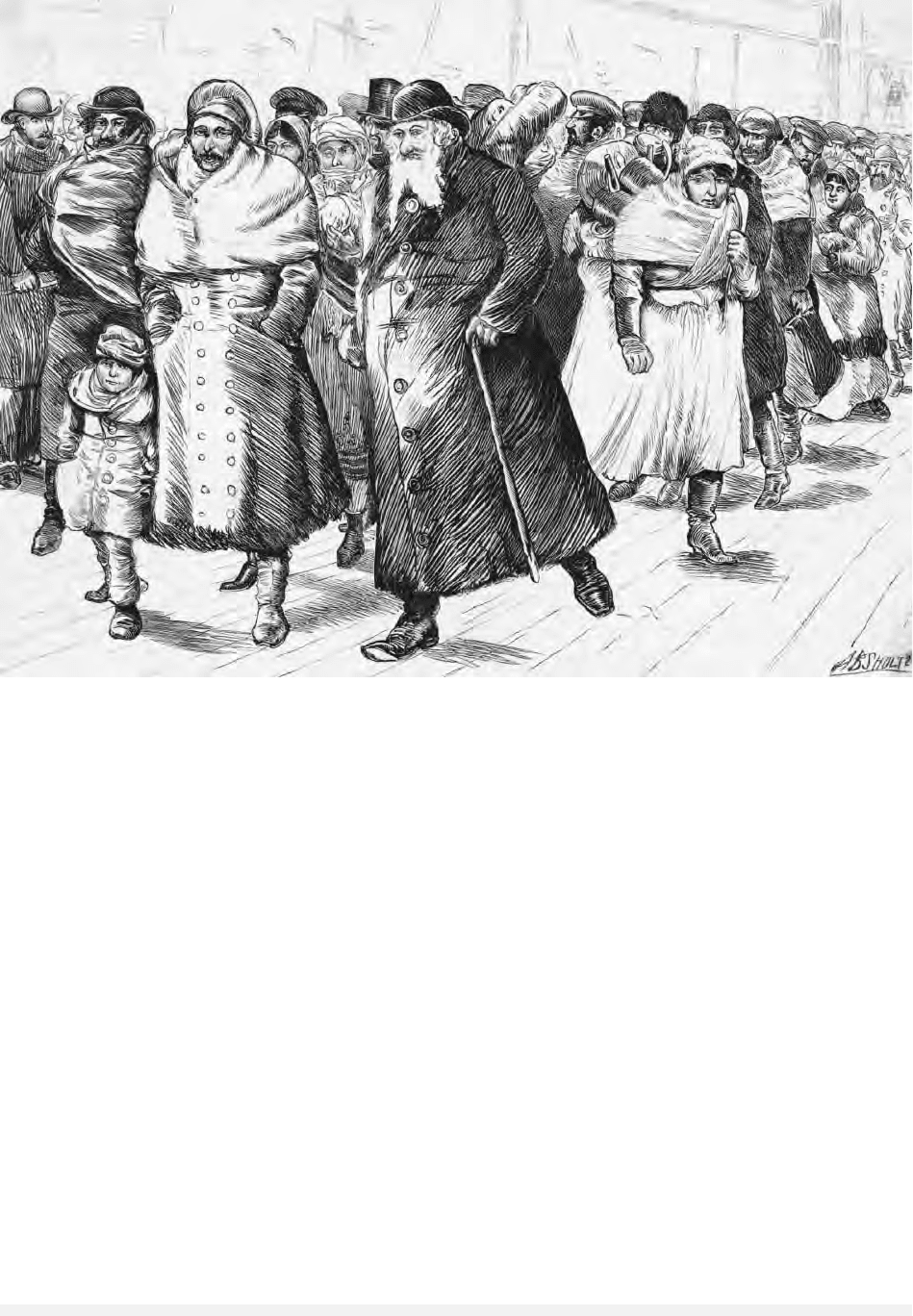

Russian Jewish exiles arrive in New York City. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

exemption from taxes, and even a degree of reli-

gious freedom. The result was a rapid and massive

immigration that slowed only in the mid- to late

nineteenth century as the amount of free land de-

clined. By the late nineteenth century, as a result

of rapid population growth after the emancipation

of the serfs, a shortage of land led the regime to

reverse its encouragement of immigration and im-

pose some serious restrictions upon it.

Immigration did not take place on a major scale

at any period under Soviet rule. While technical ex-

perts were recruited from the West in the 1930s,

and workers came to the Soviet Union in relatively

small numbers in the 1920s, and then again in the

1950s, on the whole, immigration was remarkably

small in scale throughout the entire Soviet period.

Likewise, emigration was illegal throughout

the Soviet era, and it occurred on a significant scale

only on an exceptional basis. During the Civil War,

before the Bolsheviks established firm control over

the entire territory of the state, a major emigration

of political opponents of the regime and others oc-

curred. By some estimates roughly 2 million peo-

ple left from 1918 to 1922. The next major exodus

occurred as a result of World War II, which left

millions of Soviet civilians and soldiers as displaced

peoples in areas occupied by Russia’s allies. Millions

were returned after the war—often against their

will—as a result of allied agreements. But at least

a half million were able to emigrate permanently.

The next major wave of emigration came in the

1970s when Soviet Jews were allowed to leave in

relatively substantial numbers. While only about

10,000 Soviet Jews emigrated from the Soviet

Union from 1954 to 1970, an average of 22,800

emigrated per year from 1971 to 1980. Soviet Jew-

ish emigration was sharply curtailed in the 1980s,

but when restrictions were first eased in 1988 and

then effectively removed in 1990, a mass emigra-

tion of roughly a million Jews occurred. Soviet

German emigration followed a similar pattern,

though fewer Germans were allowed to emigrate

prior to 1988. A mass emigration of nearly 1.5 mil-

lion Soviet Germans, encouraged by the German

policy of automatically granting citizenship (and

generous access to welfare and public services), oc-

curred from 1988 to 1996. In the 1990s economic

difficulties led to large emigrations of Russians and

other groups as well. This wave of emigration be-

gan to slow by the end of the 1990s, but it re-

mained important and a matter of concern at the

beginning of the twenty-first century, especially

considering the continuing high rates of emigra-

tion among well-educated and highly trained young

people.

See also: DEMOGRAPHY; GERMAN SETTLERS; JEWS; NA-

TIONALITIES POLICY, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICY,

TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bartlett, Roger P. (1979). Human Capital: The Settlement

of Foreigners in Russia, 1762–1804. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

E

RIC

L

OHR

IMPERIAL RUSSIAN

GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

Legend holds that the idea for the Russian Geo-

graphical Society (RGS) arose at a dinner party

thrown by A. F. Middendorf in St. Petersburg in

1845. Middendorf had just returned from his fa-

mous expedition to Eastern Siberia. He, along with

Fyodr Litke, Karl Ber, and Ferdinand Wrangel, con-

ceived the society, which ultimately attracted

seventeen charter members, including the most

prominent Russian explorers, scientists, and public

officials of their day. The goal was systematically

to expand and quantify the understanding of their

country, which was still relatively unknown. Geo-

graphical societies elsewhere in the world (England,

France, Prussia, and so on) were mainly concerned

with general geography, whereas homeland geog-

raphy (domashnyaya geografiya) was for them sec-

ondary. The early founders of the RGS thus were

leading proponents of the nationalist reform-

minded movement that perfused Russia in the mid-

1800s. The emphasis would be upon Russia’s special

place in the world: its diversity of climates, lan-

guages, customs, peoples, and so forth.

Although, early on, members wished to call it

the “Russian Geographical-Statistical Society,” on

August 18, 1845, Tsar Nicholas I declared that it

would be named the “Russian Geographical Soci-

ety”; this remained the official name for the next

five years. In October 1845, the majority of the

charter members held their first meeting and se-

lected 51 active members from throughout Russia.

After 1850 the society was renamed the Imperial

Russian Geographical Society (Imperatorskoye russkoye

geograficheskoye obshchestvo [IRGS]), an appellation

that would persist until 1917.

IMPERIAL RUSSIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

656

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Almost immediately after its founding, the RGS

became a polestar for opponents of Nicholas I. It be-

came one of the ideological centers of the struggle

against serfdom and had direct links to Russian

utopian socialists, such as the Petrashevsky Circle.

Its titular leader was the tsar’s second son, Grand

Prince Constantine, who represented the most

“progressive” (i. e., nationalistic) ideas of that time.

Within the society, conflict arose between the

largely non-Russian founders (the Baltic Germans)

and the ethnically pure Russian contingent.

Throughout the rest of the nineteenth century, the

IRGS stressed Russia’s messianic mission in Asia,

and most of the society’s sponsored expeditions, in-

cluding the famous Amur expedition of 1855–1863,

were indeed carried out in Asia. By 1917 the IRGS

had compiled a legacy of 1,500 volumes of schol-

arly literature.

See also: GEOGRAPHY; RUSSIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bassin, Mark. (1983). “The Russian Geographical Soci-

ety, the ‘Amur Epoch,’ and the Great Siberian Expe-

dition, 1855–1863.” Annals of the Association of

American Geographers 73:240–256.

Harris, Chauncey D., ed. (1962). Soviet Geography: Ac-

complishments and Tasks, tr. Lawrence Ecker. New

York: American Geographical Society.

V

ICTOR

L. M

OTE

IMPERIAL RUSSIAN

TECHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY

In the era before the revolution, the Imperial Russ-

ian Technical Society (IRTS) was the most impor-

tant and oldest technical organization in Russia.

Founded in 1866 in St. Petersburg on the model of

similar societies across Europe, it brought together

scientists, engineers, and other people interested in

promoting technological development. Subsidized

by the Ministry of Public Education, the Ministry

of Finances, and other government agencies, and

by industry, it focused on inventions and the ap-

plication of technology in order to further the

development of Russia’s manufacturing and pro-

duction industries and foster the country’s overall

industrial and economic growth. Headed by scien-

tists such as chemist Dmitry I. Mendeleyev and mil-

itary engineer and chemist Count Kochubei, IRTS

encouraged greater cooperation between govern-

ment and the world of science, technology, and in-

dustry.

The members of IRTS were concerned about the

output of Russia’s weak private sector and felt that

the technology policy of the tsarist state was in-

adequate, especially in the military sphere. This

view was confirmed by the Russo-Japanese War

(1904–1905), and in fact it was not until then that

the government began to encourage IRTS in its sup-

port of aviation. World War I provided IRTS with

another opportunity to demand greater state sup-

port for scientific and technological research.

From the outset IRTS was strongly committed

to the dissemination of technical education, favor-

ing the polytechnic model at the university level

rather than specialized institutes, because students

in schools of the former type would be more cre-

ative and flexible in their future jobs. In addition

to technical schools and special classes, it conducted

night schools for adults. It also tried to popularize

technological development by organizing a techni-

cal library, a technical museum, and an itinerant

museum, and by publishing science books for tech-

nical schools. As early as 1867 IRTS started pub-

lishing a magazine, Notes from the Imperial Russian

Technical Society (Zapiski IRTO), and organizing

meetings on technical subjects and on technical and

professional training. Finally, it distributed awards

and medals in support and reward of inventions

and research and applications in the field of tech-

nology.

IRTS was a national organization and had a

network of correspondents throughout Russia.

Starting in the 1860s it had offices in many

provinces. By 1896 there were twenty-three of

these, some of which published their own maga-

zines. In 1914 IRTS had two thousand members,

four times as many as when it began. The Russ-

ian Technical Society continued its activities until

1929, when it was eliminated on the grounds that

it was an organization of bourgeois specialists.

See also: ACADEMY OF SCIENCES; MENDELEYEV, DMITRY

IVANOVICH; MOSCOW AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY; SCI-

ENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POLICY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bailes, Kendall E. (1978). Technology and Society under

Lenin and Stalin. Origins of the Soviet Technical Intel-

ligentsia, 1917-1941. Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

IMPERIAL RUSSIAN TECHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY

657

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Balzer, Harley D. (1980). “Educating Engineers: Eco-

nomic Politics and Technical Training in Tsarist Rus-

sia.” Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Balzer, Harley D. (1983). “The Imperial Russian Techni-

cal Society.” In The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian

and Soviet History, edited by Joseph L. Wieczynski,

Vol. 32, 176-180. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic Inter-

national Press.

Balzer, Harley D. (1996). “The Engineering Profession in

Tsarist Russia.” In Russia’s Missing Middle Class: The

Professions in Russian History, edited by Harley D.

Balzer, 55-88. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Blackwell, William. (1968). The Beginning of Russian In-

dustrialization. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

M

ARTINE

M

ESPOULET

INDEX NUMBER RELATIVITY

The period of the first Five-Year Plans and the rapid

collectivization of Soviet agriculture, 1929–1937,

witnessed rapid economic growth accompanied

by radical changes in the structure of the Soviet

economy—first, from a predominantly agricultural

towards an industrial one, and second, within in-

dustry, from a predominantly smaller-scale econ-

omy of light and consumer industries, to heavy

industry, machinery, construction, and transporta-

tion. The vast expansion and mass production of

heavy manufacturing goods reduced their cost of

production, relative to those of light industry and

of agricultural products. This phenomenon of si-

multaneous changes in the structure of production

and relative prices during periods of rapid economic

growth in the Soviet context was discovered and

analyzed by Alexander Gerschenkron when he es-

timated the rate of economic growth of Soviet man-

ufacturing during this period. Growth of the

national product (GNP) of a country is estimated

by a quantity index, aggregating the growth of pro-

duction of individual sectors by assigning to each

sector a “weight” corresponding to the average price

of the products of this sector at a certain point of

time during the period under investigation. It has

been demonstrated that when the relative prices of

the expanding sector are declining, as in the Soviet

Union during the 1930s, the index produces a

much higher rate of growth when prices of the ini-

tial period are used as weights than the index

that uses prices at the end of the period. The first

is called a Laspeyres index and the second a Paasche

index, both named after their developers. Under the

Laspeyres index, relatively higher prices, and hence

larger weights, are assigned to faster growing sec-

tors, thus producing a higher aggregate rate of

growth, and vice versa. Hence the term “index num-

ber relativity.”

One commonly quoted calculation of the two

indexes for the period 1928 to 1937 is Abram Berg-

son’s: According to his estimates Soviet GNP grew

over that period by 2.65 times according to the

Laspeyres variant but only by 1.54 times accord-

ing to the Paasche index (1961, Table 18, p. 93).

The two measures apparently present two very dif-

ferent views on the achievements of the Soviet

economy during this crucial period, as well as on

the estimates of economic growth over the longer

run. However, since both are “true,” they must be

telling the same story. One commonly used “solu-

tion” to dealing with this relativity was to use the

(geometric) average of the two estimates. An alter-

native was to replace both measures by a Divisia

index (also named after its developer) that calcu-

lates growth for every year separately using prices

of that year as weights, and then add up all growth

rates for the entire period. The outcome is usually

not far away from the average of the Laspeyres

and Paasche indexes. Subsequent estimates of So-

viet GDP growth over this period offered a variety

of amendments to the original ones; some among

them narrowed the gap between the two indices.

During the rest of the Soviet period, the second half

of the twentieth century, index number relativity

did not play an important role, mostly because the

major structural changes were accomplished al-

ready before World War II.

See also: COLLECTIVIZATION OF AGRICULTURE; ECONOMIC

GROWTH, SOVIET; FIVE-YEAR PLANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergson, Abram. (1961). The Real National Income of So-

viet Russia since 1937. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

Gerschenkron, Alexander. (1947). “The Soviet Indexes of

Industrial Production.” Review of Economics and Sta-

tistics 29:217–226.

G

UR

O

FER

INDICATIVE PLANNING

As distinct from directive planning, as practiced in

the Soviet Union from 1928 onward, indicative

planning is a set of consistent numerical projections

INDEX NUMBER RELATIVITY

658

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

of the economic future without specific incentives

for their fulfillment. Rather, the indicative plan is

conceived as coordinated information that guides

the choices of separate entities in the market econ-

omy.

The first indicative plans were those made up

by Gosplan in the USSR during the mid-1920s.

These were soon integrated into mandatory in-

structions issued by the Supreme Council of the

National Economy (VSNKh), later by Gosplan it-

self. The output plans were supplemented by ma-

terial balances, inspired by German experience

during World War I and generalized as input-

output analysis in the work of Wassily Leontief

and others.

During and immediately after World War II

economists in Continental Europe developed the

idea of indicative planning as a guide to recovery

and to ongoing short-term economic policy mak-

ing. Notable were the Central Planning Bureau in

the Netherlands, led by Jan Tinbergen, the French

Commissariat Général du Plan, inspired by Jean

Monnet, and the Japanese Economic Planning

Agency. In all of these, government agencies play

a role in collecting and developing the information

necessary to build a multi-sectoral econometric

model. Such a model allows alternative policy in-

struments to be tested for their effects on such tar-

gets as inflation, the growth rate, and the balance

of payments. While indicative planning assumes a

primarily private market economy with competi-

tion from outside the country, the concertation (un-

official collusion) of private investment plans—as

practiced in France and Japan—is supposed to avoid

duplication of effort, increase investment volumes,

and perhaps reduce cyclical instability. Japanese

and French bureaucrats have also guided invest-

ment funds from state-controlled sources into fa-

vored projects. In practice, however, it is doubtful

that indicative planning has had much positive in-

fluence on the economic performance of these

economies, particularly as they opened themselves

up to international trade and capital flows.

Communist Yugoslavia adopted a kind of in-

dicative planning in the 1950s. The main purpose

was to guide the distribution of capital to self-

managed enterprises throughout the republics of

that country. After the fall of Communism, in-

dicative planning was also adopted in Poland. The

theoretical basis for indicative planning in a social-

ist context was developed by Janos Kornai and his

coauthors, but practice never conformed to such

rational schemes.

Indicative planning should be distinguished from

so-called “indirect planning,” embodied in the New

Economic Mechanism in Hungary in 1968 and con-

templated by Soviet reformers of the late 1980s.

Instead of establishing a mixed or regulated mar-

ket economy, as in Western Europe, the Commu-

nist authorities continued to dominate the economy

through investment and supply planning, as well

as subsidies. In both Hungary and Gorbachev’s

Russia, a weak budget constraint on wages and

other costs led to inflationary pressure and short-

ages, along with rising external debts. These prob-

lems contributed to the collapse of indirect planning.

See also: GOSPLAN; INPUT-OUTPUT ANALYSIS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ellman, Michael. (1990). “Socialist Planning.” In Prob-

lems of the Planned Economy, edited by John Eatwell,

Murray Milgate, and Peter Newman. New York:

Norton.

Kornai, Janos. (1980). Economics of Shortage. Amsterdam:

North-Holland.

M

ARTIN

C. S

PECHLER

INDUSTRIALIZATION

The concept of industrialization implies the move-

ment of an economy from a primarily agricultural

basis to a mixed or industrial/service basis with an

accompanying increase in output and output per

capita. Although the early stages of industrializa-

tion require systemic and policy measures to steer

resources into the productive process, eventually

the growth of output must be generated through

the growth of productivity. During the process of

successful industrialization, measurement of the

importance of the agricultural and industrial sec-

tors, characterized for example by output shares in

GDP, will indicate a relative shift away from agri-

cultural production towards industrial production

along with the sustained growth of total output.

The analysis of these changes differs if cast within

the framework of neoclassical economics (and its

variations) as opposed to the Marxist-Leninist

framework. Much of our analysis of the Russian

economy during the Tsarist era and the subsequent

events of the Soviet era have focused on the process

of industrialization under varying institutional

arrangements, policy imperatives, and especially

changing ideological strictures.

INDUSTRIALIZATION

659

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

To the extent that Lenin and the Bolshevik

Party wished to pursue the development of a so-

cialist and ultimately a communist economic sys-

tem after the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, the

relevant issue for the Bolshevik leadership was the

degree to which capitalism had emerged in pre-

revolutionary Russia. Fundamental to industrial-

ization in the Marxist-Leninist framework is the

development of capitalism as the engine of progress,

capable of building the economic base from which

socialism is to emerge. Only upon this base can in-

dustrial socialism, and then communism, be built.

From the perspective of classical and neoclassical

economic theory, by contrast, the prerequisites for

industrialization are the emergence of a modern

agriculture capable of supporting capital accumu-

lation, the growth of industry, the transformation

of population dynamics, and the structural trans-

formation of the Russian economy placing it on a

path of sustained economic growth.

While there is considerable controversy sur-

rounding the events of the prerevolutionary era

when cast in these differing models, the level of eco-

nomic development at the time of the Bolshevik

revolution was at best modest, and industrializa-

tion was at best in early stages. From the stand-

point of neoclassical economic theory, structural

changes taking place were consistent with a path

of industrialization. However, from a Marxist-

Leninist perspective, capitalism had not emerged.

The relevance of disagreements over these issues

can be observed if we examine the abortive period,

just after the Revolution of 1917, of War Com-

munism. While indeed an attempt was made dur-

ing this period to move towards the development

of a socialist economy, these efforts contributed lit-

tle, if anything, to the long-term process of indus-

trialization.

Although during the New Economic Policy

(NEP) a number of approaches to industrialization

were discussed at length, the outcome of these dis-

cussions confirmed that ideology would prevail.

The Marxist-Leninist framework would be used,

even in a distorted manner, as a frame of reference

for industrialization, albeit with many institutional

arrangements and policies not originally part of

the ideology. While the institutional arrangements

based upon nationalization and national economic

planning facilitated the development and imple-

mentation of socialist arrangements and policies,

priority was placed nonetheless on the rapid accu-

mulation of capital, a part of the process of indus-

trialization that should have occurred during the

development of capitalism, according to Marx.

Thus, while an understanding of the elements of

Marxism-Leninism is useful for the analysis of this

era, most Western observers have used the stan-

dard tools of neoclassical economic theory to as-

sess the outcome.

During the command era (after 1929), indus-

trialization was initially rapid, pursued through a

combination of command (nonmarket) institutions

and policies within a socialist framework. The

replacement of private property with state owner-

ship facilitated the development of state institu-

tions, which, in combination with command

planning and centralized policy-making, ensured a

high rate of accumulation and rapid expansion of

the capital stock. In effect, the basic components of

industrialization traditionally emerging though

market forces were, in the Soviet case, implemented

at a very rapid pace in a command setting, effec-

tively replacing consumer influence with plan pre-

rogatives. The pace and structural dimensions of

industrialization could, with force, therefore be

largely dictated by the state, at least for a limited

period of time. Private property was eliminated, na-

tional economic planning replaced market arrange-

ments, and agriculture was collectivized.

For some, the emergence of Soviet economic

power and its ultimate collapse presents a major

contradiction. While there is little doubt that a ma-

jor industrial base was built in the Soviet Union, it

was built without respect for basic economic prin-

ciples. Specifically, because the command economy

lacked the flexibility of market arrangements and

price messages, resources could be and were allo-

cated largely without regard to long-term produc-

tivity growth. The command system lacked the

flexibility to ensure the widespread implementation

of technological change that would contribute to

essential productivity growth. Finally, and signif-

icantly, the socialization of incentives failed, and

the consumer was largely not a part of the indus-

trial achievements. Even the dramatic changes of

perestroika during the late 1980s were unable to

shift the Soviet economy to a new growth path

that favored rational and consumer-oriented pro-

duction.

Industrialization in the post-1990 transition

era was fundamentally different from that of ear-

lier times. First, the ideological strictures of the past

were largely abandoned, though vestiges may have

remained. Second, to the extent that the command

era led to the development of an industrial base in-

INDUSTRIALIZATION

660

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

appropriate for sustaining long term economic

growth and economic development, the task at

hand became the modification of that industrial

base. Third, the modification of the industrial base

required the development of new institutions and

new policies capable of implementing necessary

changes that would place the contemporary Russ-

ian economy on a long-term sustainable growth

path. It is this challenge that separated the early

stages of industrialization from the process of in-

dustrialization during transition, since the latter

implies changes to an existing structure rather than

the initial development of that structure.

The process of industrialization is necessarily

modified and constrained by a variety of environ-

mental factors. In the case of Russia, those envi-

ronmental factors should be largely positive insofar

as Russia is a country of significant natural wealth

and human capital.

See also: ECONOMIC GROWTH, SOVIET; INDUSTRIALIZA-

TION, RAPID; INDUSTRIALIZATION, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gregory, Paul R., and Stuart, Robert C. (2001). Russian

and Soviet Economic Performance and Structure, 7th ed.

New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Millar, James R. (1981). The ABCs of Soviet Socialism. Ur-

bana: University of Illinois Press, 1981.

Nove, Alec. (1981). The Soviet Economic System. London:

Unwin Hyman.

R

OBERT

C. S

TUART

INDUSTRIALIZATION, RAPID

Soviet growth strategy was focused on fast growth

through intensive industrialization. It involved the

self-development of an industrial base, concen-

trated in capital goods or “means of production,”

also dubbed “Sector A” according to Marxian jar-

gon. It became the official strategy of the Soviet

leadership as a resolution of the Soviet Industrial-

ization debate that occupied communist thinkers

and politicians during the mid-1920s. The indus-

trialization debate considered two growth strate-

gies. One, supported by moderates and led by

Nikolai Bukharin, advocated an extension of the

New Economic Policy (NEP), centered on industri-

alization but based on the initial development of

agriculture, mostly by individual and independent

farmers. A prospering agricultural sector would

create demand on the part of both consumers and

producers for industrial goods, as well as surplus

resources in terms of savings, to finance this in-

dustrialization. While all sectors of manufacturing

would be developed, surplus agricultural products

would be used as exports in order to import ma-

chinery and technology from the West. Advocates

of the alternative strategy, including leaders of the

left such as Leon Trotsky, preferred a more rapid

state-led industrialization drive, concentrated in

large state-owned heavy industrial enterprises

financed by forced savings, extracted from collec-

tivized (thus supposedly more productive) agricul-

ture and from the population. While machinery

and technology would be imported, the main

thrust would be to build an indigenous heavy in-

dustrial base and early self-sufficiency in all in-

dustrial goods, and more autarky. The high level

of forced savings would minimize consumption

and hence provide for higher rate of investment,

faster growth, and a relatively smaller “Sector B”

of consumer goods and light industry; in contrast

with a normal path of early development of light

and consumer goods industries, followed by grad-

ual move toward the production of machinery

and capital goods. The more radical variant was

also more consistent with Marxian doctrine and

teaching.

Josef Stalin used the industrialization debate as

a leverage to gain control, first by siding with the

moderates to oust Trotsky and his followers, and

then by ousting the moderates and adopting an

even more extreme variant of forced industrializa-

tion. Other motivations for his choice of the heavy

industrialization route were the Soviet Union’s rich

endowment of natural resources (coal, iron ores,

oil, and gas), and the need (facing external threats),

or desire, to develop a strong military capability.

This strategy guided the industrialization drive

throughout, with only some easing off toward the

end of the Soviet period. The 1930s were charac-

terized by the construction of a large number of

giant industrial, power, and transportation projects

that involved moving millions of people to new and

old cities and regions. This was also the period

when collectivized agriculture was expected to pro-

vide surplus products and resources to feed the

growing industrial labor force and to export in ex-

change for modern technology. Students of the pe-

riod differ on the extent to which this really

happened, and some claim that most of the ex-

tracted surplus through food procurements had to

INDUSTRIALIZATION, RAPID

661

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

be reinvested in machinery and other inputs needed

to make the new collective and state farms work.

With the increasing threat of war toward the end

of the 1930s, manufacturing became more oriented

toward military production. Much of the indus-

trial effort during the war years was directed to-

ward the production of arms, but it was also

characterized by a gigantic transfer of many hun-

dreds of enterprises from the western parts of the

USSR eastward to Siberia and the Far East in order

to protect them from the advancing German army.

This transfer happened to be consistent with an ex-

plicit goal of the regime to develop the east and

northeast, the main concentration of natural re-

sources, an effort that was facilitated over the years

through the exploitation of millions of forced la-

bor workers.

The rate of industrial growth in the Soviet

Union was higher than that of agriculture and ser-

vices, and the share of industry in total output and

in the labor force increased over time as in any de-

veloping country. Except that in the Soviet Union

these trends were stronger: The gaps in favor of in-

dustry were wider, also due to the deliberate con-

straint on the development of the service sector,

considered nonproductive according to Marxian

doctrine. Thus the share of industrial output in

GNP climbed to more than 40 percent in the 1980s,

significantly above the share in other countries of

similar levels of economic development. The share

of industrial labor was not exceptionally high due

to the concentration of capital and of labor-saving

technology. This over-industrialization, including

noncompetitive industries, even some creating neg-

ative value, was recognized in the 1990s as a drag

on the ability of former Communist states to ad-

just to a normal market structure and an open

economy during the transition. The autarkic pol-

icy of industrialization pursued over most of the

Soviet period contributed to a technological non-

compatibility with the West, which further hurt

the competitiveness of Soviet industry.

The bias of Soviet industrialization toward Sec-

tor A of investment and capital, as well as military

goods, is apparent in the internal structure of in-

dustry. The share of Sector A industry grew fast

to almost half of total industry and stayed at

approximately that level throughout the entire pe-

riod. It was also estimated that during the 1970s

and 1980s military-related production occupied a

substantial share of the output of the machine-

building and metalworking sector as well as more

than half the entire activities of research and de-

velopment. The development of consumer and light

industry (“Sector B,” under Marxian parlance) was

not only limited in volume; it also suffered from a

low priority in the planning process and thus from

low quality and technological level. “Sector A” in-

dustries, including the major military sector, en-

joyed preferential treatment in the allocation of

capital and technology, of high-quality labor re-

sources and materials, and of more orderly and

timely supplies. Hence some of the technological

achievements in the spheres of defense and space.

Hence also the very high costs of these achieve-

ments to the economy at large and to Sector B

consumer industries in particular, which were

characterized by low-quality and lagging tech-

nology, limited assortment, and perennial short-

ages. This policy of priorities also explains the

very limited construction resources allocated to

housing and to urban development, causing hous-

ing shortages, as well as the very low production

of private cars and (to a lesser extent) household

appliances. The biased structure of industry became

also a serious barrier for restructuring under the

transition.

See also: COLLECTIVIZATION OF AGRICULTURE; ECONOMIC

GROWTH, SOVIET; INDUSTRIALIZATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bergson, Abram. (1961). The Real National Income of So-

viet Russia since 1928. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

De Melo, Martha; Denizer, Cevdet; Gelb, Alan; and Tenev,

Stoyan. (1997). “Circumstance and Choice: the Role

of Initial Conditions and Policies in Transition

Economies.” World Bank, Policy Research Working Pa-

per no. 1866.

Domar, Evsey. (1953). “A Soviet Model of Growth.” In

his Essays in the Theory of Economic Growth. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Easterly, William, and Fischer, Stanley. (1995). “The So-

viet Economic Decline: Historical and Republican

Data.” World Bank Economic Review, 9(3):341–371.

Erlich, Alexander. (1960). The Soviet Industrialization De-

bate, 1924–1928. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-

sity Press.

Millar, James R. (1990) The Soviet Economic Experience.

Urbana, University of Illinois Press.

Ofer, Gur. (1987). “Soviet Economic Growth, 1928–1985.”

Journal of Economic Literature 25(4):1767–1833.

G

UR

O

FER

INDUSTRIALIZATION, RAPID

662

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY