Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

nongovernmental organizations. They ranged from

Russian Soldiers’ Mothers, who were against the

wide abuses of military recruits, to the anti-

Stalinist and pro-rights Memorial Society, to Mus-

lim cultural and aid societies.

Seventy years of Communist social and legal

cleansing are not overcome in a decade or two. In

Ken Jowitt’s words, “We must think of a ‘long

march’ rather than a simple transition to democ-

racy” (Jowitt, 1992, 189), with all sorts of human

rights to redeem.

See also: DISSIDENT MOVEMENT; GULAG; SAKHAROV, AN-

DREI DMITRIEVICH; SOLZHENITSYN, ALEXANDER

ISAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berdiaev, Nicolas. (1960). The Origin of Russian Commu-

nism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Henkin, Louis. (1996). The Age of Rights, 2nd ed. New

York: Columbia University Press.

Human Rights Watch World Report. (2003). <http://

www.hrw.org/wr2kr/europe11.html>.

Jowitt, Ken. (1992). New World Disorder: The Leninist Ex-

tinction. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Juviler, Peter. (1998). Freedoms Ordeal: The Struggle for

Human Rights and Democracy in Post-Soviet States.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Juviler, Peter. (2000). “Political Community and Human

Rights in Post-Communist Russia.” In Human Rights:

New Perspectives, New Realities, ed. Adamantia Pollis

and Peter Schwab. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner.

Steiner, Henry, and Alston, Philip. (2000). International

Human Rights in Context: Law, Politics, Morals, 2nd

ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

P

ETER

J

UVILER

HUNGARIAN REVOLUTION

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was the first

major anti-Soviet uprising in Eastern Europe and

the first shooting war to occur between socialist

states. In contrast to earlier uprisings after the

death of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in March 1953,

such as the workers’ revolt in East Berlin (1953)

and the Polish workers’ rebellion in Poznan, Poland

(October 1956), the incumbent Hungarian leader,

Imre Nagy, did not summon Soviet military troops

to squelch the revolution. Instead, he attempted to

withdraw Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Hence,

the Hungarian revolution symbolizes perhaps the

first major “domino” to fall in a process that ulti-

mately resulted in the Soviet Union’s loss of hege-

mony over Eastern Europe in 1989.

When Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev,

delivered his Secret Speech at the Twentieth Party

Congress in February 1956, he not only exposed

Stalin’s crimes, but also presented himself as a pro-

ponent of different paths to socialism, a claim that

would later prove hard to fulfill. All over Eastern

Europe, hardline Stalinist leaders wondered fear-

fully how far destalinization would go. Meanwhile,

their opponents, who criticized Stalinist policies,

suddenly gained in popularity. In Hungary, Nagy

was one such critic and reformer. He had served as

Hungary’s prime minister from July 4, 1953, to

April 18, 1955. In the spring of 1955, however,

Nagy was dislodged by a hard-line Stalinist leader,

Mátyás Rákosi, who had been forced to cede that

post to Nagy in mid-1953.

Social pressures continued to build in Hungary

under the leadership of Rákosi, called Stalin’s “best

disciple” by some. He had conducted the anti-

Yugoslav campaign in 1948 and 1949 more zealously

than other East European party leaders. Hundreds

of thousands of Hungarian communists had been

executed or imprisoned after 1949. By late October

1956 the popular unrest in Hungary eluded the

control of both the Hungarian government led by

Rákosi’s successor, Ernõ Gerõ, and the USSR.

On October 23, 1956, several hundred thou-

sand people demonstrated in Budapest, hoping to

publicize their sixteen-point resolution and to show

solidarity with Poland where, in June, an indus-

trial strike originating in Poznan turned into a na-

tional revolt. The Budapest protesters demanded

that Nagy replace Gerõ, the Hungarian Commu-

nist Party’s first secretary from July 18 to Octo-

ber 25, 1956. Fighting broke out in Budapest and

other Hungarian cities and continued throughout

the night.

It is now known that Soviet leaders decided on

October 23 to intervene militarily. Soviet troops ex-

ecuted Plan Volna (“Wave”) at 11:00

P

.

M

. that same

day. The next morning a radio broadcast an-

nounced that Nagy had replaced András Hegedüs

as prime minister. On October 25, János Kádár,

a younger, centrist official, replaced Gerõ as first

secretary. However, this first Soviet intervention

did not solve the original political problem in the

country. New documents have revealed that the

Kremlin initially decided on October 28 against a

HUNGARIAN REVOLUTION

643

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

second military intervention. But on October 31,

they reversed course and launched a more massive

intervention (Operation Vikhr, or “Whirlwind”).

During the night of November 3, sixteen Soviet di-

visions entered Hungary. Fighting continued until

mid-November, when Soviet forces suppressed the

resistance and installed a pro-Soviet government

under Kádár.

See also: HUNGARY, RELATIONS WITH; KHRUSHCHEV,

NIKITA SERGEYEVICH;

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Békés, Csaba; Rainer, János M.; and Byre, Malcolm.

(2003). The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: A History in

Documents. Budapest: Central European University

Press.

Cox, Terry, ed. (1997). Hungary 1956—Forty Years On.

London: Frank Cass.

Granville, Johanna. (2003). The First Domino: Interna-

tional Decision Making in the Hungarian Crisis of

1956. College Station: Texas A & M University

Press.

Györkei, Jenõ, and Horváth, Miklós. (1999). The Soviet

Military Intervention in Hungary, 1956. Budapest:

Central European University Press.

Litván, György, and Bak, János M. (1996). The Hungar-

ian Revolution of 1956: Reform, Revolt and Repression,

1953–1963. New York: Longman.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

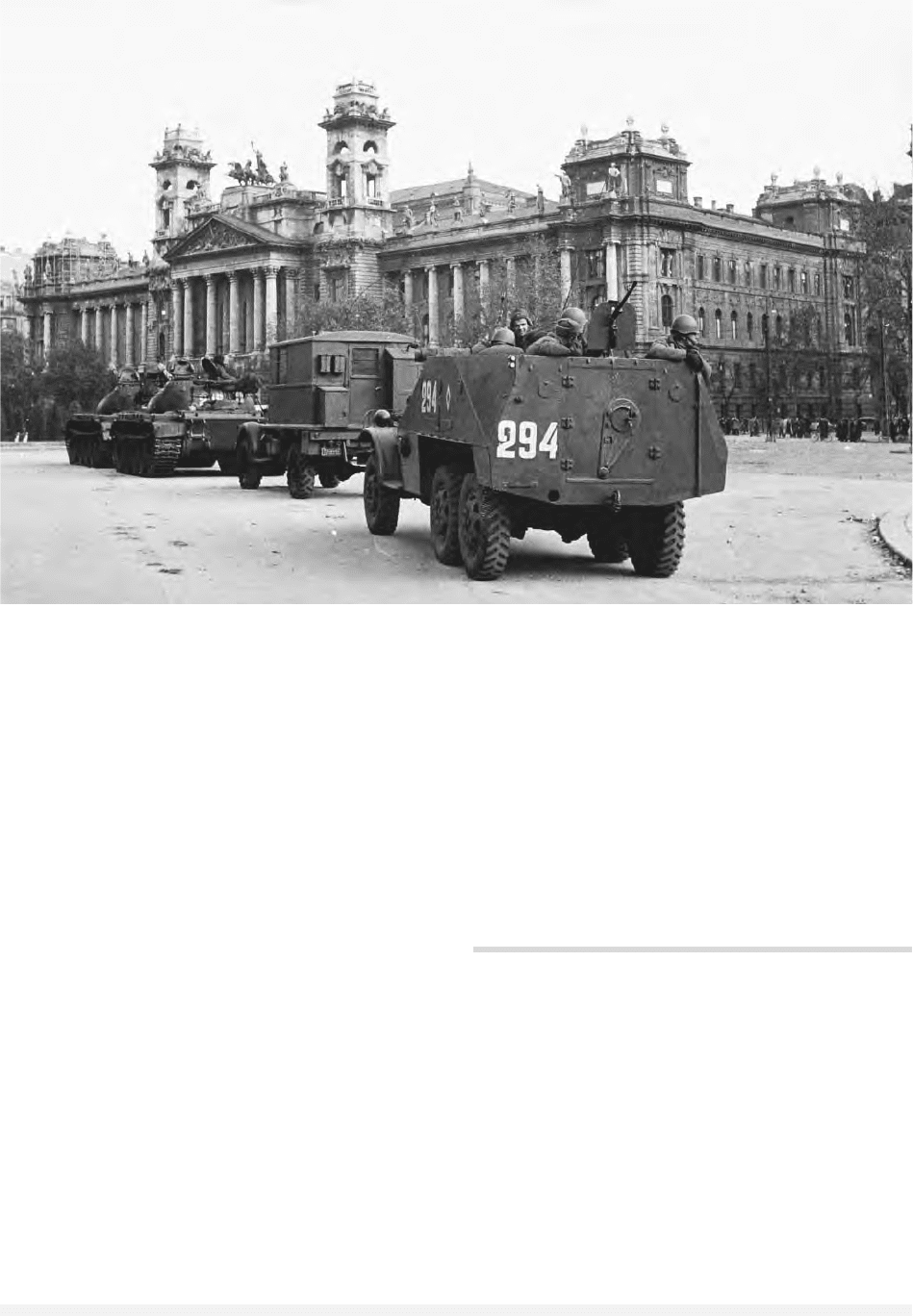

HUNGARY, RELATIONS WITH

Russian and Soviet relations with Hungary, in con-

trast to those with other east central European

countries, have been especially tense due to factors

such as Hungary’s monarchical past, historical ri-

valry with the Russians over the Balkans, Russia’s

invasion of Hungary in 1848, Hungary’s alliances

in both world wars against Russia or the USSR, the

belated influence of communism in the interwar

period, the Soviet invasion in 1956 to crush the na-

tionalist revolution, and Hungary’s vastly differ-

ent language and culture in general.

HUNGARY, RELATIONS WITH

644

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Russian tanks and armored vehicles surround the Hungarian parliament building in Budapest. © H

ULTON

A

RCHIVE

No part of Hungary had ever been under direct

Russian rule. Instead, Hungary formed part of the

Habsburg Empire, extending over more than

675,000 square kilometers in central Europe. Both

empires—the tsarist and Habsburg—fought for

hegemony over Balkan territories. The Habsburg

empire included what is now Austria, Hungary,

Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, as well as parts

of present-day Poland, Romania, Italy, Slovenia,

Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Federal

Republic of Yugoslavia. In July 1848 the Hungar-

ians, led by Lajos Kossuth, fought for liberation

from Austria. However, upon the Austrians’ re-

quest in 1849, Tsar Nicholas I sent Russian troops

to crush the rebellion. Nevertheless, Kossuth’s ini-

tiative paved the way for the compromise in March

1867 (known in German as the Ausgleich), which

granted both the Austrian and Hungarian king-

doms separate parliaments with which to govern

their respective internal affairs. It also established

a dual monarchy, whereby a single emperor (Fran-

cis Joseph I) conducted the financial, foreign, and

military affairs of the two kingdoms.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, ethnic

groups within the empire clamored for self-rule.

On June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a member of a

secret nationalist movement, Mlada Bosna (“Young

Bosnia”), shot Austrian Archduke Francis Ferdi-

nand and his wife in Sarajevo, thus precipitating

World War I. Austro-Hungary fought with Ger-

many against Great Britain, France, and Russia.

Throughout the fall of 1918 the Austro-Hungarian

Empire collapsed as its armies retreated before en-

emy forces.

On March 21, 1919, Béla Kun established a

communist regime in Hungary that lasted four

months. Given their monarchical past, Hungarians

resented communists, who seized their farms and

factories and sought to form a stateless society. Af-

ter a brief transition, Admiral Miklós Horthy be-

came Regent of Hungary, heading a new monarchy

that lasted twenty-five years.

Defeated in World War I, Hungary lost more

than two-thirds of its territory in the 1920 peace

settlement (“Treaty of Trianon”). In 1914 Hungary

had 21 million inhabitants; Trianon Hungary had

less than 8 million. German Nazi leader Adolf Hitler

was able to coax Hungary to fight on the Axis side

in World War II by promising the return of some

of the territory Hungary lost in 1920. Despite its

gradual alliance with Germany and Italy against

the Soviet Union in the war, the German army

(Wehrmacht) occupied Hungary on March 19,

1944. Hitler put Ferenc Szálasi (leader of the fas-

cist Arrow Cross Party) in charge as prime minis-

ter. By mid-April 1945, however, the Soviet Red

Army expelled the Germans from Hungary. The

Soviet troops remained in Hungary until 1990.

Another element of Hungary’s particularly

anti-Soviet history is the belated influence of com-

munism in the interwar period. While most other

East European countries turned authoritarian after

1935, Hungary remained relatively liberal until

1944. After a short democratic period, the Com-

munist Party took over in 1948. The Hungarian

Communist Party never did win an election, but

gained control due to the presence of Soviet troops

and their hold over government posts. Its first sec-

retary was Matyás Rákosi, a key figure in the in-

ternational communist movement who had

returned with other Hungarian communists from

exile in the Soviet Union. These include Imre Nagy

(later prime minister during the Hungarian Revo-

lution in 1956) and József Révai who became the

key ideologist in the 1950s. Other communists re-

mained in Hungary and organized the Communist

Party illegally during the war, such as János Kádár

(who became general secretary after 1956) and

László Rajk (the first key victim of the purges in

1949).

The Soviet Union also established its hegemony

over Eastern Europe in commercial and military

spheres. In 1949 Stalin had established the Coun-

cil for Mutual Economic Cooperation (CMEA or

Comecon) to counter President Truman’s Marshall

Plan, which Stalin prevented Hungary and other

East European countries from joining. In Comecon

the member states were expected to specialize in

particular industries; for example, Hungary fo-

cused on bus and truck production.

The East European satellites were expected to

copy the Stalinist model favoring heavy industry

at the expense of consumer goods. In doing so,

Rákosi’s economic plans contradicted Hungary’s

genuine interests, as they required the use of ob-

solete Soviet machinery and old-fashioned meth-

ods. Unrealizable targets resulted in a flagrant

waste of resources and the demoralization of

workers.

Meanwhile, fearing a World War III against its

former ally, the United States, the Soviet leadership

encouraged the Hungarian army to expand. Hav-

ing failed to prevent West Germany’s admission

into NATO, the USSR on May 14, 1955, established

HUNGARY, RELATIONS WITH

645

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the Warsaw Pact, which subordinated the satellites’

armies to a common military command. Austria

was granted neutrality in the same year. In 1956

the first major anti-Soviet uprising in Eastern

Europe—the Hungarian Revolution—took place. It

is not surprising that Hungary, given its history,

culture, and language (a non-Slavic tongue, Mag-

yar), was the first satellite to challenge Moscow di-

rectly by declaring neutrality and withdrawing

from the Warsaw Pact.

Despite the restlessness of the population after

the crushed revolution and the repression of 1957-

1958, Kádár’s regime after normalization differed

sharply from Rákosi’s style of governance. Kádár’s

brand of lenient (“goulash”) communism earned

grudging respect from the Hungarian people. Kádár

never trumpeted his moderate New Economic

Mechanism (NEM) of 1968 as a socioeconomic

model for other satellites, lest he irritate Moscow.

Hungary’s overthrow of its Communist regime

in 1989-1990 and independence today prove that

the nationalist spirit of the revolution was never

extinguished. The Soviet collapse in 1991 led to the

demise of the Warsaw Pact and Comecon. In March

1999 NATO admitted Hungary, Poland, and the

Czech Republic as members.

See also: HUNGARIAN REVOLUTION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Békés, Csaba; Rainer, János M.; and Byrne, Malcolm.

(2003). The 1956 Hungarian Revolution: A History in

Documents. Budapest: Central European University

Press.

Deák, István. (2001). Phoenix: Lawful Revolution: Louis

Kossuth and the Hungarians, 1848–1849. London:

Phoenix Press.

Felkay, Andrew. (1989). Hungary and the USSR,

1956–1988: Kadar’s Political Leadership. New York:

Greenwood Press.

Fenyo, Mario. (1972). Hitler, Horthy, and Hungary: German-

Hungarian Relations, 1941–1944. New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press.

Gerö, András. (1997). The Hungarian Parliament

(1867–1918): A Mirage of Power, tr. James Patterson.

New York: Columbia University Press.

Granville, Johanna. (2003). The First Domino: Interna-

tional Decision Making in the Hungarian Crisis of 1956.

College Station: Texas A & M University Press.

Györkei, Jeno, and Horváth, Miklos. (1999). The Soviet

Military Intervention in Hungary, 1956. Budapest:

Central European University Press.

Kann, Robert A. (1980). History of the Habsburg Empire,

1526–1918. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Litván, György, and Bak, János M. (1996). The Hungar-

ian Revolution of 1956: Reform, Revolt, and Repression,

1953–1963. New York: Longman.

O’Neill, Patrick H. (1998). Revolution from Within: The

Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party and the Collapse of

Communism. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

HUNS

The Huns (the word means “people” in Altaic) were

a confederation of steppe nomadic tribes, some of

whom may have been the descendants of the

Hsiung-nu, rulers of an empire by the same name

in Mongolia. After the collapse of the Hsiung-nu

state in the late first century

C

.

E

., the Huns mi-

grated westward to Central Asia and in the process

mixed with various Siberian, Ugric, Turkic, and

Iranian ethnic elements. Around 350, the Huns mi-

grated further west and entered the Ponto-Caspian

steppe, from where they launched raids into Tran-

scaucasia and the Near East in the 360s and 370s.

Around 375, they crossed the Volga River and en-

tered the western North Pontic region, where they

destroyed the Cherniakhova culture and absorbed

much of its Germanic (Gothic), Slavic, and Iranian

(Sarmatian) ethnic elements. Hun movement west-

ward initiated a massive chain reaction, touching

off the migration of peoples in western Eurasia,

mainly the Goths west and the Slavs west and

north-northeast. Some of the Goths who escaped

the Huns’ invasion crossed the Danube and entered

Roman territories in 376. In the process of their

migrations, the Huns also altered the linguistic

makeup of the Inner Eurasian steppe, transform-

ing it from being largely Indo-European-speaking

(mainly Iranian) to Turkic.

From 395 to 396, from the North Pontic the

Huns staged massive raids through Transcaucasia

into Roman and Sasanian territories in Anatolia,

Syria, and Cappadocia. By around 400, Pannonia

(Hungary) and areas north of the lower Danube

became the Huns’ staging grounds for attacks on

the East and West Roman territories. In the 430s

and 440s, they launched campaigns on the East

Roman Balkans and against Germanic tribes in

central Europe, reaching as far west as southern

France.

HUNS

646

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The Huns’ attacks on territories beyond the

North Pontic steppe and Pannonia were raids for

booty, campaigns to extract tribute, and mercenary

fighting for their clients, not conquests of their

wealthy sedentary agricultural neighbors and their

lands. Being pastoralists, they wielded great mili-

tary powers, but only for as long as they remained

in the steppe region of Inner Eurasia, which pro-

vided them with the open terrain necessary for their

mobility and grasslands for their horses. Conse-

quently, Hun attacks west of Pannonia were mi-

nor, unorganized, and not led by strong leaders

until Attila, who ruled from about 444 or 445 to

453. However, even he continued the earlier Hun

practice of viewing the Roman Empire primarily as

a source of booty and tribute.

Immediately after Attila’s sudden death in 453,

the diverse and loosely-knit Hun tribal confedera-

tion disintegrated, and their Germanic allies re-

volted and killed his eldest son, Ellac (d. 454). In

the aftermath, most of the Huns were driven from

Pannonia east to the North Pontic region, where

they merged with other pastoral peoples. The col-

lapse of Hun power can be attributed to their in-

ability to consolidate a true state. The Huns were

always and increasingly in the minority among the

peoples they ruled, and they relied on complex

tribal alliances but lacked a regular and permanent

state structure. Pannonia simply could not provide

sufficient grasslands for a larger nomadic popula-

tion. However, the Hun legacy persisted in later

centuries. Because of their fierce military reputa-

tion, the term “Hun” came to be applied to many

other Eurasian nomads by writers of medieval

sedentary societies of Outer Eurasia, while some

pastoralists adopted Hun heritage and lineage to

distinguish themselves politically.

See also: CAUCASUS; CENTRAL ASIA; UKRAINE AND

UKRAINIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Christian, David. (1998). A History of Russia, Central Asia

and Mongolia, Vol. 1: Inner Asia from Prehistory to the

Mongol Empire. Oxford: Blackwell.

Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of

the Turkic Peoples. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harras-

sowitz Verlag.

Maenchen-Helfen, O. J. (1973). The World of the Huns:

Studies in Their History and Culture. Berkeley: Uni-

versity of California Press.

Sinor, Denis. (1990). “The Hun Period.” In The Cambridge

History of Early Inner Asia, ed. Denis Sinor. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

R

OMAN

K. K

OVALEV

HUNS

647

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

This page intentionally left blank

ICONS

Icons are representations, usually on wood, of sa-

cred figures—Christ and the Virgin Mary, the apos-

tles, saints, and miraculous events. The Greek term

eikon (Russian, obraz) denotes “semblance,” indi-

cating that the icon does not incarnate but only

represents sacred objects. As such it serves to facil-

itate spiritual communion with the sacred; the dis-

tinctive two-dimensional flatness symbolizes an

immateriality and hence proximity to the other-

worldly. In rare cases this mediating role reaches

miraculous proportions when the faithful believe

that a “miracle-working” (chudotvornaya) icon has

interceded to save them from harm, such as the

depredations of war and disease.

The evolution of icons in Russia paralleled the

development of Eastern Orthodoxy itself. Initially,

after Grand Prince Vladimir embraced Eastern Or-

thodoxy in 988, icons were produced by Greek

masters in Byzantium; few in number, they were

restricted to the urban elites that actually practiced

the new faith. The most venerated icon in Russia,

the “Vladimir Mother of God,” was actually a

twelfth-century Greek icon imported from Con-

stantinople. Revered for its representation of the

Virgin’s tender relationship to Christ, it became the

model of the umilenie (tenderness) style that dom-

inated Marian representation in most Russian

iconography.

The Crusades from the West and the Mongol

invasion from the East suddenly disrupted the

Byzantine predominance in the mid-thirteenth cen-

tury. The new indigenous icons showed a marked

tendency toward not only simplification but also

regionalization. As Kiev Rus dissolved into separate

principalities under Mongol suzerainty, icon-paint-

ing acquired distinctive styles in Vladimir-Suzdal,

Novgorod, Pskov, Yaroslavl-Rostov, Tver, and

Moscow. Some icons also bore a distinctive local

theme, such as the “Battle between the Novgoro-

dians and Suzdalians,” a mid-fifteenth century icon

with unmistakable overtones for Novgorod’s life-

and-death struggle with Moscow.

The evolution of icon painting also derived

from external influences. One phase began with

the resumption of ties to Byzantium in the mid-

fourteenth century and culminated in the icons and

frescoes of Theophanes the Greek (c. 1340–after

1405). His indigenous co-workers included the

most venerated Russian icon-painter, Andrei Rublev

(c. 1360–1430), whose extant creations include the

I

649

celebrated “Trinity” icon. A second phase came in

the late fifteenth century, when Italian masters—

imported to construct an awe-inspiring Kremlin—

helped introduce some Western features (for

example, the clothing and gestures of the Virgin).

That was but a foreshadowing of the far greater

Western influence in the seventeenth century,

when the official icon-painting studios in the Krem-

lin Armory (under Simon Ushakov, 1626–1686)

used Western paints and techniques to produce

more naturalistic, monumental icons. Such inno-

vations elicited sharp criticism from traditionalists

such as Archpriest Avvakum, but they heralded

tendencies ever more pronounced in Imperial Rus-

sia.

Even as Moscow developed an official style, the

production of icons for popular consumption be-

came much more widespread. The Church Council

of 1551 complained about the inferior quality of

such images and admonished painters not to “fol-

low their own fancy” but to emulate the ancient

icons of “the Greek icon-painters, Andrei Rublev,

and other famous painters.” That appeal did noth-

ing to stem the brisk production of popular icons,

with some small towns (e.g., Palekh, Kholuy,

Shuya, and Mstera) gaining particular renown.

Popular icons were not only simpler (indulging

fewer details and fewer colors), but also incorpo-

rated folkish elements alien to both traditional

Byzantine and newer official styles. Although au-

thorities sought to suppress such icons (e.g., a 1668

edict restricting the craft to certified icon-painters),

such decrees had scant effect.

Indeed, both popular and elite icon-painting

continued to coexist in the eighteenth and nine-

teenth centuries. Popular icons flourished and pro-

liferated; while some centers (such as the specialized

producers in Vladimir province) exhibited artistic

professionalization, the expanding production of

amateur icons aroused the concern of both Church

and state. But attempts to regulate the craft (e.g.,

decrees of 1707 and 1759) did little to restrict pro-

duction or to dampen demand. A far greater threat

eventually came from commercialization—the

manufacture of brightly colored, cheap lithographs

that pushed artisanal icons from the marketplace

in the late nineteenth century. Seeking to protect

popular icon painting, Nicholas II established a

Committee for the Stewardship of Russian Icon

Painting in 1901, which proposed a broad set

of measures, such as the establishment of icon-

painting schools to train craftsmen and to promote

their work through special exhibitions.

Icon production for elites took a quite different

path. After Peter the Great closed the icon-painting

studio of the Armory in 1711, its masters scattered

to cities throughout the realm to ply their trade.

By the late eighteenth century, however, the Acad-

emy of Arts became the main source of icons

for the major cathedrals and elites. By the mid-

nineteenth century the Academy had not only de-

veloped a distinct style (increasingly naturalistic

and realistic) but also significantly expanded its for-

mal instruction in icon painting, including the es-

tablishment of a separate icon-painting class in

1856.

At the same time, believers and art connois-

seurs showed a growing taste for ancient icons. By

mid-century this interest began to inspire forgeries

as well as orders for icons in the old style. The

meaning of that old style underwent a revolu-

tionary change in the early twentieth century: As

art restorers peeled away the layers of paint and

varnish applied in later times, they were aston-

ished to discover that the ancient icons were not

dark and somber, but bright and clear. The All-

Russian Congress of Artists in 1911 held the first

exhibition of restored icons; the new Soviet regime

would devote much attention to the process of

restoration.

While placing a high priority on icon restora-

tion, the Soviet regime repressed production of new

icons: It closed traditional ecclesiastical producers

(above all, monasteries), and redirected popular

centers of icon production such as Palekh to

specialize in secular folk art. Although Church

workshops continued to produce icons (by the early

1980s more than three million per year—an im-

portant source of revenue), not until 1982 did the

Church establish an elite patriarchal icon-painting

studio. The subsequent breakup of the Soviet Union

not only generated a sharp surge in demand (from

believers and reopened churches), but enabled the

Church to establish a network of icon-painting

schools specifically devoted to the revival of tradi-

tional iconography.

See also: ACADEMY OF ARTS; BYZANTIUM, INFLUENCE OF;

DIONISY; ORTHODOXY; PALEKH PAINTING; RUBLEV,

ANDREI; THEOPHANES THE GREEK; USHAKOV, SIMON

FEDOROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Onasch, Konrad, and Schneiper, Annemarie. (1995).

Icons: The Fascination and the Reality. New York:

Riverside Book Company.

ICONS

650

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Ouspensky, Leonid, and Lossky, Vladimir. (1982). The

Meaning of Icons, 2nd. ed. Crestwood, NY: St.

Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

G

REGORY

L. F

REEZE

IDEALISM

The debates regarding Russia’s national identity

and historical destiny were always vital to the work

of the prominent Russian thinkers, who were also

preoccupied with moral issues and closely involved

with literature. Due to its location between Europe

and Asia, Russia belongs to both cultural worlds,

having inherited different and often contradictory

value standards that played a significant role in the

course of its history. This marginal cultural situ-

ation of the country resulted in two competing ap-

proaches to its role in world history: national

isolationism and openness to Europe, both trends

still present in the national consciousness. During

the Kievan Rus period, affiliation with Europe was

a strong feature of culture. The Tatar invasion and

the development of the Moscow Kingdom gener-

ated a strong tide of alienation from the West. Af-

ter the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the Moscow

Kingdom was the proclaimed “the third Rome” (by

monk Filotius)—the vanguard force in world his-

tory inheriting the grandeur of the Roman Empire

and at the same time opposed to the declining West.

Peter the Great made a radical attempt to bridge the

gap between Russia and the West by assimilating

European values and life standards on Russian soil.

However, his attempt to create a new cultural syn-

thesis brought about contradictory results: super-

ficial reception of the Western standards in

economic, social, political, and cultural spheres on

the one hand, and reinforcement of traditional non-

European Russian values on the other. As Nikolai

Berdyayev noted, Russia never knew the Renais-

sance and never accepted the humanism and indi-

vidualism produced within this cultural paradigm.

Although European civilization created the discipli-

nary society (Michel Foucault) in the modern pe-

riod, it preserved the sphere of individual rights and

liberties that was gradually expanding in parallel

with rational standards of social control and coer-

cion. Communal and authoritarian tendencies of

Russian culture had no real counterbalance in per-

sonal values such as those commonly accepted in

Europe. Even in the period of Russian Enlighten-

ment that started under Catherine II, the critical ef-

forts of such leading intellectuals as Nikolai Novikov,

Mikhail Shcherbatov, or Alexander Radishchev did

not bring radical change to tsarist rule and the pre-

vailing cultural climate of the country.

The understanding of national history through-

out the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

was considerably influenced by the Enlightenment,

German idealism, and the philosophy of Romanti-

cism. Whatever their value systems, Russian thinkers

of the first part of the nineteenth century inter-

preted history in view of the tragic events of the

French Revolution and Napoleon’s invasion of Rus-

sia. This is the reason why, as Vasily Zenkovsky

pointed out, Russian thinkers were highly critical

of the results of Western historical development.

The structure of Russian thought from the En-

lightenment to the beginning of the twenty–first

century was based on binary oppositions lacking

synthetic reconciling units. Oppositions deeply em-

bedded in Russian thought included communitari-

anism and democracy versus imperial autocracy;

egalitarianism versus social hierarchy; progress

versus traditionalism; and so forth. The deficiency

of synthesis of contradictions inherent in Russian

thought constitutes its difference from the West-

ern intellectual paradigm.

RUSSIA AND THE WEST: THE DILEMMA

OF NATIONAL SELF–IDENTITY

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, West-

ernized Russian thought found its expression in

two different trends: the moderate conservatism of

historian and writer Nikolai Karamzin, who de-

fended autocracy of the Catherine II variety against

the chaos of the French Revolution, and the De-

cembrist movement, which idealized the democra-

tic traditions of Novgorod and Pskov republics and

intended to put constitutional limits on the autoc-

racy of the tsar. Famous poet Alexander Pushkin

(according to Berdyayev, the only Russian man of

the Renaissance) vigorously supported the ideas of

the Decembrists. At the opposite pole, Vladimir

Odoyevsky, Dmitry Venevitinov, and other mem-

bers of the Wisdom–lovers society, who represented

the anti–Enlightenment trend and were convinced

followers of Schelling, believed in the leading role

of Russia and its mission to save European civi-

lization. Although Pyotr Chaadayev’s thought was

also nourished by Schelling and other representa-

tives of German idealism, he took a more critical

approach to Russia. According to Chaadayev, Rus-

sia lacked a true heritage of historical tradition and

should therefore assimilate the European cultural

IDEALISM

651

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

legacy before assuming a leadership role in tack-

ling humanity’s problems.

These discussions evolved into the debate of the

Slavophiles and the Westernizers. Despite their crit-

icism of serfdom and the existing political order,

Ivan Kireyevsky, Alexei Khomyakov, Konstantin

Aksakov, and other Slavophiles, highly disparag-

ing of Catholicism and Protestantism, European in-

dividualism, and the rationalist culture of the

Enlightenment, proclaimed the necessity of finding

a particularly Russian path of cultural and politi-

cal development. While critical of the West, Ger-

man idealism, and Hegelian doctrine as its utmost

expression, the Slavophiles were nevertheless nour-

ished conceptually by Schelling’s philosophy. They

believed in the superiority of Russian civilization

based on the Russian Orthodox vision of the unity

of human and God, the special harmonic order of

relations existing among the believers (sobornost),

and the peasant commune organization of social

life as a paradigm of organic relations that should

replace the external coercion of state power.

In contrast to the Slavophiles, the Westerniz-

ers believed in the productive role of humanity’s

rational development and progress, the positive sig-

nificance of the modernization process initiated by

Peter the Great, and the necessity to unify Russia

with the European West. Unlike the Slavophiles,

this movement had no homogeneous philosophy

and ideology, representing rather a loose alliance of

different trends of literary and philosophical

thought that were strongly influenced by German

idealism and, in particular, by Hegel. Radical de-

mocrats, such as Vissarion Belinsky, Alexander

Herzen, or Nikolai Ogarev, proposed ideas that dif-

fered from the liberal persuasions of Timofei Gra-

novsky, Konstantin Kavelin, and Boris Chicherin.

Moderate criticism of the European West and

nascent mass society, common to many Western-

izers, found its utmost expression in the peasant

socialism of Herzen and Ogarev, who, like the

Slavophiles, idealized the peasant commune as a

pattern of organic social life needed by Russia.

Nikolai Chernyshevsky and other revolution-

ary democratic enlighteners of the 1860s, who fur-

ther developed the Westernizers’ ideas while

upholding the value of the communal foundations

of Russian peasant society, paved the way for the

radical populist ideology of Pyotr Lavrov, Pyotr

Tkachev, and Mikhail Bakunin and the liberal pop-

ulism of Nikolai Mikhailovsky. Radical populist

ideology influenced the Russian version of Marx-

ism considerably. The “return to the soil” move-

ment, headed by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Nikolai

Strakhov, and Apollon Grigoriev, was a reaction to

this trend of thought. In the 1870s, Nikolai

Danilevsky developed his philosophical theory of

historical–cultural types inspired by the ideal of

Pan–Slavic unity with the leadership of Russia.

Skeptical of both the Pan–Slavic ideal and the con-

temporary stage of European liberal egalitarian so-

ciety, Konstantin Leontiev proposed, in his version

of the conservative theory of historical–cultural

types, the ideal of Byzantinism preserving the com-

munal and hierarchical traditional foundations of

Russian culture and society in isolation and oppo-

sition to the liberal–individualistic European West.

THE SEARCH FOR THE UNIVERSAL VISION OF HISTORY

AND THE CHALLENGE OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

The end of the nineteenth century and the begin-

ning of the twentieth century were marked by the

growing popularity of Friedrich Nietzsche, Karl

Marx, Leo Tolstoy, and Vladimir Soloviev in Russ-

ian intellectual circles. As one of the prophets of his

time, Tolstoy, in the tradition of Rousseau, put for-

ward a criticism of industrial civilization and state

power in the capitalist age and proposed his utopian

ideal of Christian anarchism glorifying the archaic

peasant way of life as a radical denial of the exist-

ing social order and alienation. Based on the ideas

of Plato and the neo–Platonists Leibniz and Schelling,

Soloviev’s doctrine of absolute idealism interpreted

history as a field of human creativity, a realization

of Godmanhood—that is, the permanent coopera-

tion of God and human. In his philosophy of his-

tory, Soloviev moved from the understanding of

Russia’s role as the intermediary link between the

East and West to the ideal of theocratic rule unify-

ing the Church power (the pope) with earthly rule

of the Russian tsar, and finally came to a profound

criticism of theocratic rule. On the final stage of his

philosophical career, he gave a very critical evalua-

tion of the autocratic tradition of the Moscow King-

dom and the Russian Empire that became the source

of inspiration for Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Nikolai

Berdyayev, Vyacheslav Ivanov, and other Silver Age

religious philosophers who revealed the negative

traits of the alliance between the Orthodox Church

and the State and called for the free creativity of re-

ligious laymen in order to bring about radical

change in Russian social and cultural life.

After the Bolshevik Revolution the majority of

prominent Russian thinkers had to migrate abroad.

Berdyayev, Georgy Fedotov, and Merezhkovsky

continued there the tradition of the philosophy of

IDEALISM

652

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY