Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Moscow refused, the United States deployed in Eu-

rope two kinds of INF: cruise missiles that could

fly in under Soviet radar, and ballistic missiles with

warheads able to reach Kremlin bomb shelters.

Seeking better relations with the West, Gor-

bachev put aside his objections to the U.S. quest

for antimissile defenses. Gorbachev and Reagan in

1987 signed a treaty that obliged both countries to

destroy all their ground-based missiles, both bal-

listic and cruise, with a range of 500 to 5,500 kilo-

meters. To reach zero, the Kremlin had to remove

more than three times as many warheads and de-

stroy more than twice as many missiles as Wash-

ington, a process both sides completed in 1991.

Skeptics noted that each side retained other missiles

able to do the same work as those destroyed and

that INF warheads and guidance systems could be

recycled.

See also: COLD WAR; STRATEGIC ARMS LIMITATION

TREATIES; STRATEGIC DEFENSE INITIATIVE; ZERO-

OPTION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clemens, Walter C., Jr. (1990). Can Russia Change? The

USSR Confronts Global Interdependence. New York:

Routledge.

FitzGerald, Frances. (2000). Way Out There in the Blue:

Reagan, Star Wars, and the End of the Cold War. New

York: Simon & Schuster.

Herf, Jeffrey. (1991). War by Other Means: Soviet Power,

West German Resistance, and the Battle of Euromissiles.

New York: Free Press.

Talbott, Strobe. (1985). Deadly Gambits. New York: Vin-

tage/Random House.

Wieczynski, Joseph L., ed. (1994). The Gorbachev Ency-

clopedia: Gorbachev, the Man and His Times. Los An-

geles: Center for Multiethnic and Transnational

Studies.

Wieczynski, Joseph L., ed. (1994). The Gorbachev Reader.

Los Angeles: Center for Multiethnic and Transna-

tional Studies.

W

ALTER

C. C

LEMENS

J

R

.

INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION

The United States in 1984 initiated a program to

build a space station—a place to live and work in

space—and invited its allies in Europe, Japan, and

Canada to participate in the project, which came to

be called “Freedom.” In 1993 the new presidential

administration of Bill Clinton seriously considered

canceling the station program, which had fallen be-

hind schedule and was over budget. Space officials

in Russia suggested as an alternative that the United

States merge its space station program with the

planned Russian Mir-2 program.

The United States accepted this suggestion and

made it a key element of the redesign of what came

to be called the International Space Station (ISS).

The existing partners in the Freedom program

issued a formal invitation to Russia to join the sta-

tion partnership, which Russia accepted in Decem-

ber 1993.

There were both political and technical reasons

for welcoming Russia into the station program. The

Clinton administration saw station cooperation as

a way of providing continuing employment for

Russian space engineers who otherwise might have

been willing to work on improving the military ca-

pabilities of countries hostile to the United States.

Cooperation provided a means to transfer funds

into the struggling Soviet economy. It was also in-

tended as a signal of support by the White House

for the administration of President Boris Yeltsin.

In addition, Russia brought extensive experi-

ence in long-duration space flight to the ISS pro-

gram and agreed to contribute key hardware

elements to the redesigned space station. The U.S.

hope was that the Russian hardware contributions

would accelerate the schedule for the ISS, while also

lowering total program costs.

Planned Russian contributions to the ISS pro-

gram include a U.S.-funded propulsion and stor-

age module, known as the Functional Cargo Block,

built by the Russian firm Energia under contract

to the U.S. company Boeing. Russia agreed to pay

for a core control and habitation unit, known as

the service module; Soyuz crew transfer capsules

to serve as emergency escape vehicles docked to the

ISS; unmanned Progress vehicles to carry supplies

to the ISS; two Russian research laboratories; and

a power platform to supply power to these labo-

ratories.

The Functional Cargo Block (called Zarya) was

launched in November 1998, and Russia continued

to provide a number of Soyuz and Progress vehi-

cles to the ISS program. However, Russia’s eco-

nomic problems delayed work on the service

module (called Zvezda), and it was not launched

until July 2000, two years behind schedule. As of

INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION

673

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

January 2002, it was unclear whether Russia

would actually be able to fund the construction of

its two promised science laboratories and the asso-

ciated power platform.

With the launch of Zvezda, the ISS was ready

for permanent occupancy, and a three-person crew

with a U.S. astronaut as commander and two Russ-

ian cosmonauts began a 4.5 month stay aboard in

November 2000. Subsequent three-person crews

are rotating between a Russian and a U.S. com-

mander, with the other two crew members being

from the other country. The crew size aboard ISS

is planned to grow to six or seven after the Euro-

pean and Japanese laboratory contributions are at-

tached to ISS sometime after 2005.

The sixteen-nation partnership in the ISS is the

largest ever experiment in technological coopera-

tion and provided a way for Russia to maintain its

involvement in human space flight, which dates

back to 1961, the year of the first person in space,

Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin.

See also: MIR SPACE STATION, SPACE PROGRAM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (2002).

“International Space Station.” http://spaceflight

.nasa.gov/station.

Progressive Management. (2001). “2001—The Interna-

tional Space Station Odyssey Begins: The Complete

Guide to the ISS with NASA and Russian Space

Agency Documents.” CD-ROM. Mount Laurel, New

Jersey: Progressive Management.

J

OHN

M. L

OGSDON

INTOURIST See TOURIST.

INTER-REGIONAL DEPUTIES’ GROUP

The Inter-Regional Deputies’ Group (IRDG) took

shape in June 1989 as a loose democratic group-

ing in the first USSR Congress of People’s Deputies.

But its main historical achievements were the prop-

agation of democratic ideas to the Soviet public, and

its catalytic role as a focus and example for demo-

cratic groups. Its period of intense activity lasted

less than a year. Its functions were soon super-

seded, primarily by the rise of the Democratic Rus-

sia movement.

At the time of IRDG’s spontaneous emergence,

its spokespersons took pains to deny that it was a

faction that might divide the congress. However,

by the time it held its founding conference on July

29–30, 1989, Soviet miners had launched a strike

that put forward political as well as economic de-

mands and radicalized political thinking among So-

viet democrats. The IRDG realized that its original

goal of merely pressuring the Communist Party

into conducting reforms no longer fit the mood of

those elements in a society that favored change.

Now it needed to campaign for what the former

dissident Andrei Sakharov had demanded at the

congress: the repeal of Article Six of the Soviet Con-

stitution, which legitimized the political monopoly

of the Communists. Only such repeal would allow

the emergence of a variety of constitutionally le-

gitimate parties, and thus open the door to radical

change.

This principle, coupled with the IRDG’s insis-

tence on the right of the union republics to exer-

cise the sovereignty to which they were already

entitled on paper, became the two main planks of

the IRDG’s initial program. Later, principles such

as support for a market economy and private prop-

erty were added.

The founding conference, attended by 316 of

the congress’s 2,250 deputies, saw much debate on

whether the IRDG should constitute itself as a fac-

tion, and whether it should define itself as an op-

position. The majority, convinced by historian Yuri

Afanasiev’s proposition that Marxism-Leninism

was unreformable, was inclined to answer these

questions in the affirmative. Organizationally, 269

of those present joined the new group and elected

as their leaders five co-chairmen and a coordinat-

ing council of twenty. The co-chairmen comprised

Afanasiev; Sakharov; the politically reascendant

Boris Yeltsin; the economist and future mayor of

Moscow, Gavriil Popov; and—to symbolize the

IRDG’s commitment to the sovereignty of the

union republics—the Estonian Viktor Palm.

Over the next months the IRDG held meetings

at which numerous speeches were made and many

draft laws proposed. However, partly because its

most ambitious politician, Yeltsin, usually chose to

act independently of the IRDG, the group proved

unable to channel all this activity into practical ac-

tion. Soon it realized that factional activity in the

congress was not feasible for a small group that

never numbered more than four hundred. Some of

its members, notably Yeltsin, saw that the up-

coming elections to the fifteen new republican con-

INTOURIST

674

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

gresses, scheduled for early 1990, held out more

promise of real political change than did the USSR

congress. Others, such as Sakharov and Afanasiev,

rejected this approach, which was inevitably tinged

with ethnic nationalism, in favor of uniting de-

mocrats and promoting democratization through-

out the whole of the USSR.

In sum, the IRDG’s brief but bold example of

self-organization in the often hostile environment

of the USSR congress, and the enormous publicity

generated by the televised speeches of IRDG mem-

bers at the first two congresses and other public

meetings, had major repercussions for the democ-

ratic groups and candidates who organized them-

selves for the 1990 elections, and thus, also, for the

development of Russian democracy.

See also: ARTICLE 6 OF 1977 CONSTITUTION; CONGRESS OF

PEOPLE’S DEPUTIES; POPOV, GAVRIIL KHARITONOVICH;

SAKHAROV, ANDREI DMITRIEVICH; YELTSIN, BORIS

NIKOLAYEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. (2001). The Tragedy

of Russia’s Reforms: Market Bolshevism Against Democ-

racy. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press.

Urban, Michael; Igrunov, Vyacheslav; and Mitrokhin,

Sergei. (1997). The Rebirth of Politics in Russia. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

P

ETER

R

EDDAWAY

IRAN, RELATIONS WITH

During the period of the Shah, Soviet-Iranian rela-

tions were cool, if not hostile. Memories of the 1946

Soviet occupation of Northern Iran, the activities

of the Iranian Communist Party, and the increas-

ingly close U.S.-Iranian alliance kept Moscow and

Tehran diplomatically far apart, although there

was a considerable amount of trade between the

two countries. Following the overthrow of the

Shah, Moscow initially hoped the Khomeini regime

would gravitate toward the Soviet Union. How-

ever, the renewed activities of the Iranian commu-

nist party, together with Tehran’s anger at Moscow

for its support of Baghdad during the Iran-Iraq

war, kept the two countries apart until 1987, when

Moscow increased its support for Iran. By 1989

Moscow had signed a major arms agreement with

Tehran, and the military cooperation between the

two countries continued into the post-Soviet pe-

riod.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Iran

emerged as Russia’s primary ally in the Middle East.

Moscow became Iran’s most important supplier of

sophisticated military equipment, including com-

bat aircraft, tanks, and submarines, and began

building a nuclear reactor for Tehran. For its part,

Iran provided Moscow with important diplomatic

assistance in combating the Taliban in Afghanistan

and in achieving and maintaining the ceasefire in

Tajikistan, and both countries sought to limit U.S.

influence in Transcaucasia and Central Asia.

The close relations between Russia and Iran,

which had begun in the last years of the Soviet

Union under Gorbachev, developed steadily under

both Yeltsin and Putin, with Putin even willing to

abrogate the Gore-Chernomyrdin agreement, ne-

gotiated between the United States and Russia in

1995, which would have ended Russian arms sales

to Iran by 2000.

Moscow was also willing, despite U.S. objec-

tions, to aid Iran in the development of the Shihab

III intermediate-range ballistic missile and to sup-

ply Iran with nuclear reactors. However, there were

areas of conflict in the Russian-Iranian relationship.

First, the two countries were in competition over

the transportation routes for the oil and natural gas

of Central Asia and Transcaucasia. Iran claimed it

provided the shortest and safest route for these en-

ergy resources to the outside world, while Russia

wished to control the energy export routes of the

states of the former Soviet Union, believing that

these routes lay in the Russian sphere of influence.

Second, by early 2001 Russia and Iran had come

into conflict over the development of the energy

resources of the Caspian Sea. Russia sided with

Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan in their call for the de-

velopment of their national sectors of the Caspian

Sea, while Iran demanded either joint development

of the Caspian Sea or a full 20 percent of the Caspian

for itself. A third problem lay on the Russian side.

Throughout the 1990s the conservative clerical

regime in Iran became increasingly unpopular, and

while it held the levers of power (army, police, and

judiciary), the election of the Reformist Mohammed

Khatami as Iran’s President in 1997 (and his over-

whelming reelection in 2001), along with the elec-

tion in 2000 of a reformist Parliament (albeit one

with limited power), led some in the Russian lead-

ership to fear a possible Iranian-American rap-

prochement, which would have limited Russian

IRAN, RELATIONS WITH

675

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

influence in Iran. The possibilities of economic co-

operation between the United States and Iran

dwarfed those of Russia and Iran, particularly be-

cause both Russia and Iran throughout the 1990s

encountered severe economic problems. Fortunately

for Moscow, the conservative counterattack against

both Khatami and the reformist Parliament at least

temporarily prevented the rapprochement, as did

President George W. Bush’s labeling of Iran as part

of the “axis of evil” in January 2002. On the other

hand, Russian-Iranian relations were challenged by

the new focus of cooperation between Russia and

the United States after the terrorist attacks of Sep-

tember 11, 2001, and by Russia’s acquiescence in

the establishment of U.S. bases in central Asia.

In sum, throughout the 1990s and into the

early twenty-first century, Russia and Iran were

close economic, military, and diplomatic allies.

However, it was unclear how long that alliance

would remain strong.

See also: IRAQ, RELATIONS WITH; UNITED STATES, RELA-

TIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Freedman, Robert O. (2001). Russian Policy Toward the

Middle East Since the Collapse of the Soviet Union: The

Yeltsin Legacy and the Challenge for Putin (The Donald

W. Treadgold Papers in Russian, East European, and

Central Asian Studies, no. 33). Seattle: Henry M.

Jackson School of International Studies, University

of Washington.

Nizamedden, Talal. (1999). Russia and the Middle East.

New York: St. Martin’s.

Rumer, Eugene. (2000). Dangerous Drift: Russia’s Middle

East Policy. Washington, DC: Washington Institute

for Near East Policy.

Shaffer, Brenda. (2001). Partners in Need: The Strategic

Relationship of Russia and Iran. Washington, DC:

Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Vassiliev, Alexei. (1993). Russian Policy in the Middle East:

From Messiasism to Pragmatism. Reading, UK: Ithaca

Press.

R

OBERT

O. F

REEDMAN

IRAQ, RELATIONS WITH

Following the signing of its Treaty of Friendship

and Cooperation with the Soviet Union in 1972,

Iraq became Moscow’s primary ally in the Arab

world. The warm Soviet-Iraqi relationship came to

an end, however, in 1980, when Iraq invaded Iran,

thereby splitting the Arab world and creating seri-

ous problems for Moscow’s efforts to create anti-

imperialist Arab unity. During the Iran-Iraq war

Moscow switched back and forth between Iran and

Iraq, but by the end of the war, in 1988, Gor-

bachev’s new thinking in world affairs had come

into effect, and the United States and USSR had be-

gun to cooperate in the Middle East. That cooper-

ation reached its peak when the United States and

USSR cooperated against the Iraqi invasion of

Kuwait in 1990.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Yeltsin’s Rus-

sia inherited a very mixed relationship with the

Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein. Although Iraq had

been a major purchaser of Soviet arms, Saddam’s

invasion of Iran in 1980 and Kuwait in 1990 had

greatly complicated Soviet foreign policy in the

Middle East and led to the erosion of Moscow’s in-

fluence in the region. At the beginning of his pe-

riod of rule as Russia’s President, Boris Yeltsin

adopted an anti-Iraqi position and even contributed

several ships to aid the United States in enforcing

the anti-Iraqi naval blockade to prevent contraband

from reaching Iraq.

However, beginning in 1993 when Yeltsin

came under attack from the increasingly powerful

parliamentary opposition, he began to improve re-

lations with Iraq, both to gain popularity in par-

liament and to demonstrate he was not a lackey of

the United States. Thus Yeltsin began to criticize

the periodic U.S. bombings of Iraq, even when it

was in retaliation for the assassination attempt

against former President George Bush.

By 1996, when Yevgeny Primakov became

Russia’s Foreign Minister, Russia had three major

objectives in Iraq. The first was to regain the more

than seven billion dollars in debts that Iraq owed

the former Soviet Union. The second was to acquire

business for Russian companies, especially its oil

companies. The third objective by 1996 was to en-

hance Russia’s international prestige by opposing

what Moscow claimed was Washington’s efforts

to create an American-dominated unipolar world.

Moscow, however, ran into problems with its

Iraqi policy in 1997 and 1998 when U.S.-Iraqi ten-

sion escalated over Saddam Hussein’s efforts to in-

terfere with U.N. weapons inspections. While

Russian diplomacy helped avert U.S. attacks in No-

vember 1997, February 1998, and November 1998,

Moscow, despite a great deal of bluster, was un-

IRAQ, RELATIONS WITH

676

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

able to prevent a joint U.S.–British attack against

suspected weapons sites in December 1998.

Following the attack, Moscow sought a new

U.N. weapons inspection system, and when Putin

became Prime Minister in 1999, Russia succeeded

in pushing through the U.N. Security Council

the UNMOVIC inspection system to replace the

UNSCOP inspection system. Unfortunately for

Moscow, which, under Iraqi pressure, abstained on

the vote, Iraq refused to accept the new system,

which linked Iraqi compliance with the inspectors

with the temporary (120-day) lifting of U.N. sanc-

tions on civilian goods. This meant that most of

the Russian oil production agreements that had

been signed with the Iraqi government remained

in limbo, although Moscow did profit from the

agreements made under the U.N.–approved “oil-

for-food” program.

When the George W. Bush administration came

to office, it initially sought to toughen sanctions

against Iraq, especially on “dual-use” items with

military capability, such as heavy trucks (which

could carry missiles). Russia opposed the U.S. pol-

icy, seeking instead to weaken the sanctions. The

situation changed, however, after September 11,

2001, when there was a marked increase in

U.S.-Russian cooperation, and the two countries

worked together to work out a mutually accept-

able list of goods to be sanctioned. Russia, how-

ever, ran into problems when the U.S. attacked Iraq

in March 2003. Russia condemned the attack, and

U.S.-Russian relations deteriorated as a result, al-

though there was a rapprochement at the end of

the war when Russia supported the U.S.–sponsored

UN Security Council resolution 1483 that con-

firmed U.S. control of Iraq.

See also: IRAN, RELATIONS WITH; PERSIAN GULF WAR;

UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Freedman, Robert O. (2001). Russian Policy Toward the

Middle East Since the Collapse of the Soviet Union: The

Yeltsin Legacy and the Challenge for Putin (The Donald

W. Treadgold Papers in Russian, East European, and

Central Asian Studies, no. 33). Seattle: Henry M.

Jackson School of International Studies, University

of Washington.

Nizamedden, Talal. (1999). Russia and the Middle East.

New York: St. Martin’s.

Rumer, Eugene. (2000). Dangerous Drift: Russia’s Middle

East Policy. Washington, DC: Washington Institute

for Near East Policy.

Shaffer, Brenda. (2001). Partners in Need: The Strategic Re-

lationship of Russia and Iran. Washington, DC:

Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Vassiliev, Alexei. (1993). Russian Policy in the Middle East:

From Messiasism to Pragmatism. Reading, UK: Ithaca

Press.

R

OBERT

O. F

REEDMAN

IRON CURTAIN

“From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic,

an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.”

With these words on March 5, 1946, former British

Prime Minister Winston Churchill marked out the

beginning of the Cold War and a division of Europe

that would last nearly forty-five years. Churchill’s

metaphorical iron curtain brought an end to the un-

comfortable Soviet-Anglo-American alliance against

Nazi Germany and began the process of physically

dividing Europe into two spheres of influence. In his

speech Churchill recognized the “valiant Russian

people” and Josef Stalin’s role in the destruction of

Hitler’s military, but then asserted that Soviet in-

fluence and control had descended across Eastern

Europe, thereby threatening the safety and security

of the entire continent through “fifth columns”

and “indefinite expansion of [Soviet] power and doc-

trines.” In even more provocative language Churchill

equated Stalin with Adolph Hitler by telling his

American audience that the Anglo-American alliance

must act swiftly to prevent another catastrophe, this

time communist instead of fascist, from befalling

Europe.

In response, Stalin also equated Churchill with

Hitler. Stalin rebuked Churchill for using odious

Nazi racial theory in his suggestion that the na-

tions of the English-speaking world must unite

against this new threat. For Stalin this smacked of

racial domination of the rest of the world. He noted

that Soviet casualties (which he grossly under-

counted) far outweighed the deaths of the other al-

lies combined and that therefore Europe owed a debt

to the USSR, not to the United States as Churchill

claimed, for saving the continent from Hitler. Stalin

explained his intentions in occupying what would

become known as the Eastern Bloc: After such

devastating losses, was it not logical, he asked, to

try to find peaceful governments on the Soviet bor-

der? Stalin conceded Churchill’s point that com-

munist parties were growing, but argued that this

IRON CURTAIN

677

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

was due to the failures of the West, not Soviet oc-

cupation. The people for whom Churchill had such

disdain, according to Stalin, were moving toward

leftist parties because the communists throughout

Europe were some of the first and fiercest foes of

fascism. Moreover, he noted that this was precisely

why British citizens voted Churchill out of power

in favor of the Labor Party.

By linking the other to Hitler, both men sought

to demonize their one-time ally and convince their

audiences that a new war against an equal evil was

on the horizon. This set the tone for the rest of the

Cold War as the western powers established the

Truman Doctrine, Marshall Plan, and NATO, to

which the USSR responded in quick succession. The

chief battleground was divided Germany and

Berlin. Any escalation by one side was quickly met

by the other, as both sides operated on mistaken

assumptions that a war for world dominance (or

at least regional dominance) was at hand. In short,

the “Iron Curtain” speech, the real title of which

was “Sinews of Peace,” created a metaphorical di-

vision of Europe that soon became a reality. This

division only began to erode in 1989 with the de-

struction of the Berlin Wall and the 1991 dissolu-

tion of the Soviet Union.

See also: COLD WAR; GERMANY, RELATIONS WITH; STALIN,

JOSEF VISSARIONOVICH; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alperovitz, Gar. (1965). Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and

Potsdam; The Use of the Atomic Bomb and the Ameri-

can Confrontation with Soviet Power. New York: Si-

mon and Schuster.

Gaddis, John Lewis. (1997). We Now Know: Rethinking

Cold War History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kort, Michael. (1998). The Columbia Guide to the Cold War.

New York: Columbia University Press.

McCauley, Martin. (1995). The Origins of the Cold War,

1941–1949. New York: Longman.

K

ARL

D. Q

UALLS

ISLAM

From the beginning, Rus and its successors have

interacted with Muslims as neighbors, rulers, and

subjects. Long-distance trade in silver from Mus-

lim lands provided the impetus for the establish-

ment of the first Rus principalities, and Islam

arrived in the lands of Rus before Christianity. The

rulers of the Volga Bulghar state converted to Is-

lam at the turn of the tenth century, several decades

before Vladimir’s conversion to Christianity in 988

C

.

E

. The Bulghar state was destroyed between 1236

and 1237 by the Mongols, who then went on to

subjugate the principalities of Rus. The conversion

to Islam in 1327 of Özbek Khan, the ruler of the

Golden Horde, meant that political overlordship of

the lands of Rus was in the hands of Muslims for

over a century. As the power relationship between

Muscovy and the Golden Horde began to shift,

Muscovite princes found themselves actively in-

volved in its succession struggles. In 1552 Ivan IV

conquered Kazan, the most prominent of the suc-

cessor states of the Golden Horde, and began a long

process of territorial expansion, which brought a

diverse group of Muslims under Russian rule by

the end of the nineteenth century.

THE TSARIST STATE AND ITS

MUSLIM POPULATION

Muscovy acquired its first Muslim subjects as early

as 1392, when the so-called Mishar Tatars, who

inhabited what is now Nizhny Novgorod province,

entered the service of Muscovite princes. The khans

of Kasymov, a dynasty that lost out in the suc-

cession struggles of the Golden Horde, came under

Muscovite protection in the mid-fifteenth century

and became a privileged service elite. Nevertheless,

the conquest of Kazan was a turning point, for it

opened up the steppe to gradual Muscovite expan-

sion. Over the next two centuries Muscovy ac-

quired numerous Muslim subjects as it asserted

suzerainty over the Bashkir and Kazakh steppes. In

1783 Catherine II annexed Crimea, the last of the

successors of the Golden Horde, and late-eigh-

teenth-century expansion brought Russia to the

Caucasus. While the annexation of the Transcau-

casian principalities (including present-day Azer-

baijan) was accomplished with relative ease, the

conquest of the Caucasus consumed Russian ener-

gies for the first half of the nineteenth century. The

final subjugation of Caucasian tribes was complete

only with the capture of their military and spiri-

tual leader, Shamil, in 1859. Finally, in the last ma-

jor territorial expansion of its history, Russia

subjugated the Central Asian khanates of Khiva,

Bukhara, and Kokand in a series of military cam-

paigns between 1864 and 1876. Kokand was abol-

ished entirely, and large parts of the territory of

Khiva and Bukhara were also annexed to form the

province of Turkestan. The remaining territories of

Khiva and Bukhara were turned into Russian pro-

ISLAM

678

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

tectorates in which traditional rulers enjoyed wide-

ranging autonomy in internal affairs, but where

external economic and political relations were un-

der the control of Russia. The conquest of Central

Asia dramatically increased the size of the empire’s

Muslim population, which stood at more than

fourteen million at the time of the census of 1897.

The Russian state’s interaction with Islam and

Muslims varied greatly over time and place, and it

is fair to say that no single policy toward Islam

may be discerned. In the immediate aftermath of

the conquest of Kazan, the state followed a policy

of harsh repression. Repression was renewed in the

early eighteenth century, when Peter and his suc-

cessors began to see religious uniformity as a de-

sirable goal. In 1730 the Church opened its Office

of New Converts and initiated a campaign of con-

version in the Volga region. While its primary tar-

get were the animists inhabiting the region, the

Office also destroyed many mosques. As many as

7,000 Tatars may have converted to Orthodoxy,

thus laying the foundation of the Kräshen com-

munity of Christian Tatars. For much of the rest

of the imperial period, however, the state’s attitude

is best characterized as one of “pragmatic flexibil-

ity” (Kappeler). Service to the state was the ulti-

mate measure of loyalty and the source of privilege.

Those Tatar landlords who survived the disposses-

sion of the sixteenth century were allowed to keep

their land and were even able to own Orthodox

serfs.

The reign of Catherine II (1762–1796) marks a

turning point in the state’s relationship with its

Muslim subjects. She made religious tolerance an

official policy and set about creating a basis for loy-

alty to the Russian state in the Tatar lands. She af-

firmed the rights of Muslim nobles and even sought

to induct the Muslim clerisy in this endeavor. In

1788, she established a “spiritual assembly” at

Orenburg. The Orenburg Muslim Spiritual Assem-

bly was an attempt, unique in the Muslim world,

by the state to impose an organizational structure

ISLAM

679

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Muslims pray at Moscow’s principal mosque, March 5, 2001. © R

EUTERS

N

EW

M

EDIA

I

NC

./CORBIS

on Islam. Islam was for Catherine a higher form

of religion than shamanism, and she hoped that

the Kazakhs would gradually be brought into the

fold of Islam through the efforts of the Tatars. This

was of course intertwined with the goal of bring-

ing the Kazakh steppe under closer Russian control

and outflanking Ottoman diplomacy there. Headed

by a mufti appointed by the state, the assembly

was responsible for appointing and licensing imams

as teachers throughout the territory under its

purview, and overseeing the operation of mosques.

While the policies enacted by Catherine sur-

vived until 1917 in their broad outline, her enthu-

siasm for Islam did not. The Enlightenment had

also brought to Russia the concept of fanaticism,

and it tended to dominate Russian thinking about

Islam in the nineteenth century. Islam was now

deemed to be inherently fanatical, and the question

now became one of curbing or containing this

fanaticism. If Catherine had hoped for the Islamiza-

tion of the Kazakhs as a mode of progress, nine-

teenth century administrators sought to protect the

“natural” religion of the Kazakhs from the “fanat-

ical” Islam of the Tatars or the Central Asians.

Conquered in the second half of the nineteenth

century and having a relatively dense population,

Central Asia came closer than any other part of the

Russian empire to being a colony. The Russian pres-

ence was thinner, and the local population not in-

corporated into empire-wide social classifications.

Not only was there was no Central Asian nobility,

but the vast majority (99.8%) of the local popu-

lation were defined solely as inorodtsy (alien, i.e.,

non-Russian, peoples). The region was ruled by a

governor-general possessing wide-ranging powers

and answerable directly to the tsar. The first gov-

ernor-general, Konstantin Kaufman (in office

1867–1881), laid the foundations of Russian poli-

cies in the region. For Kaufman, Islam was irre-

deemably connected with fanaticism, which could

be provoked by thoughtless policies. Such fanati-

cism could be lessened by ignoring Islam and de-

priving it of all state support, while the long-term

goal of assimilating the region into the Russian em-

pire was to be achieved through a policy of en-

couraging trade and enlightenment. Kaufman

therefore did not allow the Orenburg Muslim As-

sembly to extend its jurisdiction into Turkestan.

The policy of ignoring Islam completely was mod-

ified after Kaufman’s death, but the Russian pres-

ence was much more lightly felt in Central Asia

than in other Muslim areas of the empire.

ISLAM UNDER RUSSIAN RULE

Islam is an internally diverse religious system in

which many traditions and ways of belonging to

the community of Muslims coexist. As Devin De-

Weese has shown, Islam became a central aspect of

the communal identities of Muslims in the Golden

Horde. Conversion was remembered in sacralized

narratives that defined conversion as the moment

that the community was constituted. Shrines of

saints served to Islamize the very territory on

which Muslims lived. Until the articulation in

the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

of modern national identities among the various

Muslim communities of the Russian empire, com-

munal identities were a composite of ethnic, ge-

nealogical, and religious identities, inextricably

intertwined.

The practice of Islam, its reproduction, and its

transmission to future generations took place in

largely autonomous local communities. Each

community was centered around a mosque and

(especially in Central Asia) a shrine. The servants

of the mosques were selected by the community,

and the funding provided by local notables or

through endowed property (waqf). Each commu-

nity also maintained a maktab, an elementary

school in which children acquired basic knowledge

of Islamic ritual and belief. Higher religious edu-

cation took place in madrasas, both locally and in

neighboring Muslim countries. Unlike the Chris-

tian clergy, Muslim scholars, the ulama, were a

self-regulating group. Entry into the ranks of the

ulama was contingent upon education and inser-

tion into chains of discipleship. Islamic religious

practice required neither the institutional frame-

work nor the property of a church. This loose

structure meant that the fortunes of Islam and its

carriers were not directly tied to the vicissitudes

of Muslim states.

The process of Islamization continued after the

Russian conquest of the steppe and was at times

even supported by the Russian state. The state set-

tled Muslim peasants in the trans-Volga region in

the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but the

main agent of the Islamization of the steppe was

the Tatar mercantile diaspora. As communities of

Tatar merchants appeared throughout the steppe

beginning in the late eighteenth century, Tobolsk,

Orenburg, and Troitsk became major centers of Is-

lamic learning. Tatar merchants began sending

their sons to study in Central Asia, and Sufi link-

ages with Central Asia and the lands beyond were

strengthened.

ISLAM

680

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

VARIETIES OF REFORM

In the early nineteenth century, reform began to

emerge as a major issue among Tatar ulama. The

initial issues, as articulated by figures such as

Abdunnasir al-Qursavi (1776–1812) and Qayyum

Nasiri (1825–1902), related to the value of the tra-

dition of interpretation of texts as it had been prac-

ticed in Central Asia and in the Tatar lands since

Mongol times. Qursavi, Nasiri, and their followers

questioned the authority of traditional Islamic the-

ology and argued for creative reinterpretation

through recourse to the original scriptural sources

of Islam. This religious conception of reform was

connected to developments in the wider Muslim

world through networks of education and travel.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Tatar schol-

ars such as Musa Jarullah Bigi, Alimjan Barudi,

and Rizaetdin Fakhretdin were prominent well be-

yond the boundaries of the Russian empire.

A different form of reform arose around the re-

form of Muslim education. Its initial constituency

was the urban mercantile population of the Volga

region and the Crimea, and its origins are connected

with the tireless efforts of the Crimean Tatar no-

ble Ismail Bey Gaspirali (1851–1914). Gaspirali had

been educated at a military academy but became

involved in education early on in his career. Mus-

lims, he felt, lacked many skills important to full

participation in the mainstream of imperial life. The

fault lay with the maktab, which not only did not

inculcate useful knowledge, such as arithmetic, ge-

ography, or Russian, but failed, moreover, in the

task of equipping students with basic literacy or

even a proper understanding of Islam itself. Gaspi-

rali articulated a modernist critique of the maktab,

emanating from a new understanding of the pur-

poses of elementary education. The solution was a

new method (usul-i jadid) of education, in which

children were taught the Arabic alphabet using

the phonetic method of instruction and the ele-

mentary school was to have a standardized cur-

riculum encompassing composition, arithmetic,

history, hygiene, and Russian. Gaspirali’s method

found acceptance among the Muslim communities

of the Crimea, the Volga, and Siberia, and eventu-

ally appeared in all parts of the Russian empire in-

habited by Muslims. New-method schools quickly

became the flagship of a multifaceted movement of

cultural reform, which came to be called “Jadidism”

after them.

Jadidism was an unabashedly modernist dis-

course of cultural reform directed at Muslim soci-

ety itself. Its basic themes were enlightenment,

progress, and the awakening of the nation, so that

the latter could take its own place in the modern,

civilized world. Given the lack of political sover-

eignty, however, it was up to society to lift itself

up by its bootstraps through education and disci-

plined effort. Jadid rhetoric was usually sharply

critical of the present state of Muslim society,

which the Jadids contrasted unfavorably to a glo-

rious past of their own society and the present of

the civilized countries of Europe. The single most

important term in the Jadid lexicon was taraqqi,

progress. Progress and civilization were universal

phenomena for the Jadids, accessible to all societies

on the sole condition of disciplined effort and en-

lightenment. There was nothing in Islam that pre-

vented Muslims from joining the modern world;

indeed, the Jadids argued that only a modern per-

ISLAM

681

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

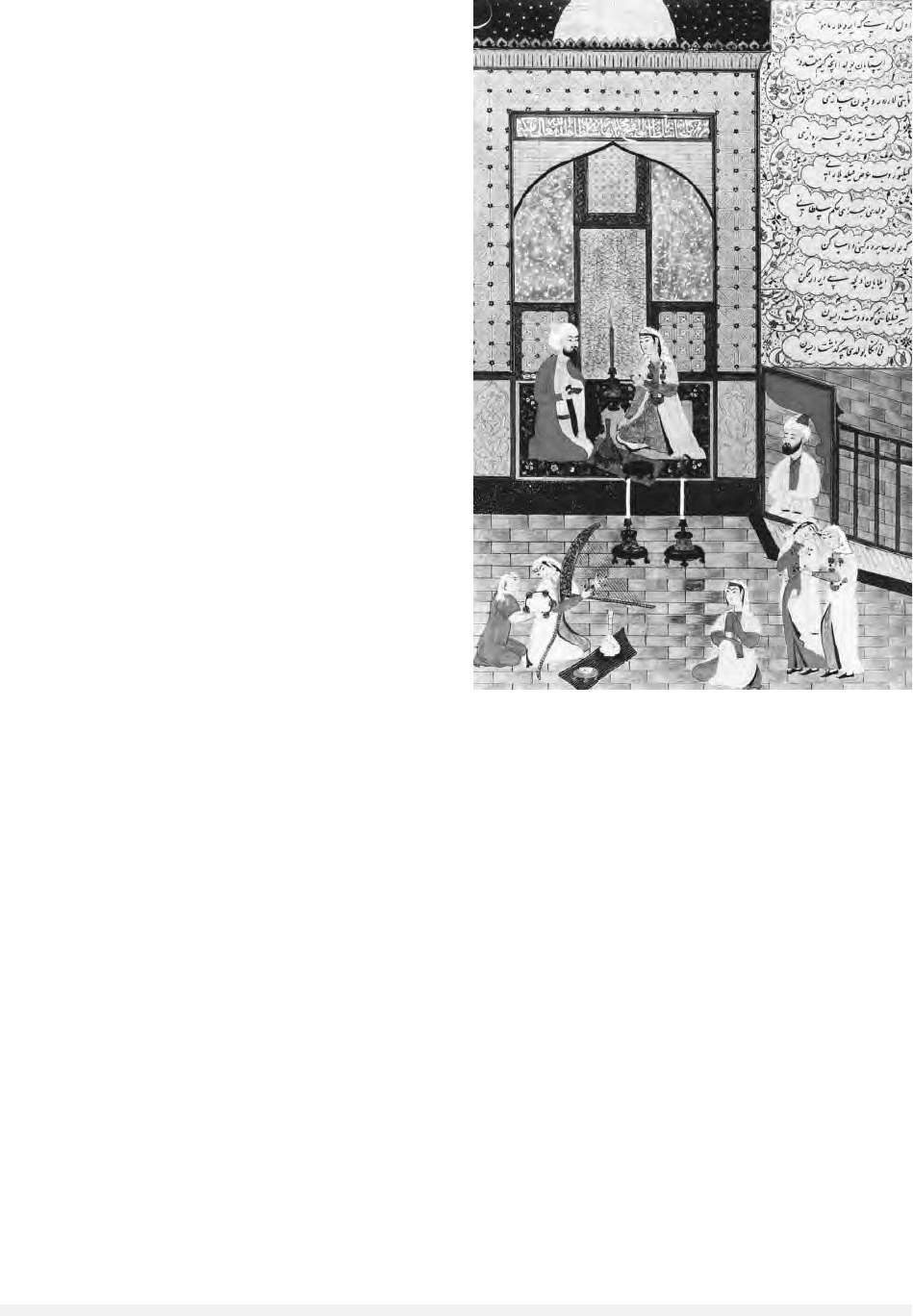

Sixteenth-century manuscript illustration showing Bahram Gur,

legendary Sassanian king in Persian mythology, and the Russian

princes in the Red Pavilion. © T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/B

ODLEIAN

L

IBRARY

O

XFORD

/T

HE

B

ODLEIAN

L

IBRARY

son equipped with knowledge “according to the

needs of the age” could be a good Muslim. In this,

Jadidism differed sharply from other currents of

reform among the ulama. The debate between the

Jadids and their traditionalist opponents was the

defining feature of the last decades of the Tsarist

period.

In Central Asia, the distinct social and political

context imparted Jadidism a distinct flavor. The

ulama retained much greater influence in Central

Asia, while the new mercantile class was weaker.

Central Asian Jadids, therefore, tended to be more

strongly rooted in Islamic education than their

counterparts elsewhere. Nevertheless, they faced

resolute opposition from within their own society,

as well as from a Russian state always suspicious

of unofficial initiatives.

THE “MUSLIM QUESTION” IN LATE

IMPERIAL POLITICS

For the Jadids, the nation was an integral part of

modernity, and they set out to define the parame-

ters of their nation. The new identity was not fore-

ordained, however, for the nation could be defined

along any of several different axes of solidarity. For

some, all Muslims of the Russian empire consti-

tuted a single national community. Gaspirali ar-

gued that the Muslims needed “unity in language,

thought, and deeds,” and his newspaper sought to

show this through example. In 1905 a number of

Tatar and Azerbaijani activists organized an All-

Russian conference for Muslim representatives to

work out a common plan of action. The conference

established the Ittifaq-i Müslimin (Union of Mus-

lims) as a quasi-political organization. Delegates re-

solved to work for greater political, religious, and

cultural rights for their constituency. During the

elections to the Duma, the Ittifaq aligned itself with

the Kadets. Two further conferences were held in

1905 and 1906, but Muslim political activity was

curbed after the Stolypin coup of 1907, which re-

duced the representation of Muslims and denied the

Ittifaq permission to register a political party.

Muslim unity was threatened by regional and

ethnic solidarities. The discovery of romantic no-

tions of identity by the Jadids led them to articulate

the identity of their community along ethnona-

tional lines. Here too, visions of a broad Turkic

unity coexisted with narrower forms of identity,

such as Tatar or Kazakh. The appeal of local eth-

nic identities proved too strong for broader Islamic

or Turkic identities to surmount. This was the case

in 1917, when the All-Russian Muslim movement

was briefly resurrected and Tatar leaders organized

a conference in Moscow to discuss a common po-

litical strategy for Muslims. Divisions between

representatives from different regions quickly ap-

peared, and the various groups of Muslims went

their separate ways.

Although Muslim activists continually pro-

fessed their loyalty to the state, their activity

aroused suspicion both in the state and among the

Russian public, which construed it as pan-Islamism

and connected it with alleged Ottoman intrigues to

destabilize the Russian state. The rise of ethnic self-

awareness was likewise seen as pan-Turkism and

also connected to outside influences. Russian ad-

ministrators had hoped that enlightenment would

be the antidote to fanaticism. Now the fear of pan-

Islamism and pan-Turkism, both articulated by

modern-educated Muslims, led to a reappraisal. The

fanaticism of modernist Islam was deemed much

more dangerous than that of the traditional Islam,

since it led to political demands. This perception

led the state to intensify its support for traditional

Islam.

THE SOVIET PERIOD

The Russian revolution utterly transformed the po-

litical and social landscape in which Islam existed

in the Russian empire. The new regime was radi-

cally different from its predecessor in that it ac-

tively sought to intervene in society and to reshape

not just the economy, but also the cultures of its

citizens. It was hostile to religion, perceiving it as

both an alternate source of loyalty and a form of

cultural backwardness. As policies regarding Soviet

nationalities emerged in the 1920s, the struggle

for progress acquired a prominent role, especially

among nationalities deemed backward (and all

Muslim groups were so classified). Campaigns for

cultural revolution began with the reform of edu-

cation, language, and the position of women, but

quickly extended to religion. The antireligious cam-

paign eventually led to the closure of large num-

bers of mosques (many were destroyed, others

given over to “more socially productive” uses,

such as youth clubs, museums of atheism, or

warehouses). Waqf properties were confiscated,

madrasas closed, and large numbers of ulama ar-

rested and deported to labor camps or executed. The

only Muslim institution to survive was the spiri-

tual assembly, now stationed in Ufa.

The campaign was effective in its destruc-

tiveness. Islam did not disappear, but the infra-

structure which reproduced Islamic religious and

ISLAM

682

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY