Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Ukraine (CPU) under Volodymyr Shcherbytsky

(1918–1989). In early 1980, following the Soviet

invasion of Afghanistan, Ivashko was sent tem-

porarily to Kabul, where he played the role of ad-

visor to Soviet puppet ruler Babrak Karmal.

Subsequently, however, he remained in Ukraine.

After the resignation of Shcherbytsky in Septem-

ber 1989, Ivashko was elected first secretary of the

Central Committee (CC) of the CPU. During the

summer of 1990, he resigned suddenly after

Mikhail Gorbachev requested that he take up a

newly created position in Moscow as deputy gen-

eral secretary of the CC of the Communist Party

of the Soviet Union on July 11, 1990. At the

Twenty-Eighth Party Congress of the same month,

he defeated Yegor Ligachev in an election to take

on this role. Analysts continue to debate Ivashko’s

role in the failed putsch of August 1991 in Moscow,

in which he appeared to have adopted a middle role

between the plotters and Gorbachev.

See also: UKRAINE AND UKRAINIANS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kuzio, Taras. (2000). Ukraine: Perestroika to Independence.

New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Solchanyk, Roman. (2001). Ukraine and Russia: The Post-

Soviet Transition. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Little-

field.

Wilson, Andrew. (1997). Ukrainian Nationalism in the

1990s: A Minority Faith. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

D

AVID

R. M

ARPLES

IZBA

Izba is the Russian word for “peasant hut.”

The East Slavic (Russian, Ukrainian) izba re-

mained fundamentally unchanged as the Slavs mi-

grated into Ukraine sometime after 500 C.E., then

moved north to Novgorod and the Finnish Gulf by

the end of the ninth century, and finally migrated

east into the Volga-Oka mesopotamia between

1000 and 1300. Primarily the Slavs settled in

forested areas because predatory nomads kept them

north of the steppes. In forested regions the izba

typically was a log structure with a pitched,

thatched roof. The dimensions of the huts depended

on the height of the trees out of which they were

constructed. In the few non-forested areas where

East Slavs lived prior to the construction of forti-

fied lines (especially the Belgorod Line in 1637–1653),

which walled the steppe off from areas to the north

of it, people inhabited houses constructed of staves,

wattle, and mud. From time to time people also

lived in semi-pit dwellings, dugouts in the ground

covered over with branches and other materials to

keep out the rain and snow.

The interiors of the izba were fundamentally

the same everywhere, though the precise layouts

depended on locale. In the North and in central Rus-

sia, when one entered through the door, the stove

(either immediately adjacent to the wall or with a

space between the stove and the wall) was imme-

diately to the right, and the stove’s orifice was fac-

ing the wall opposite the entrance. In southeastern

Russia the stove was along the wall opposite the

entrance, with the orifice facing the entrance. Other

variations could be found in western and south-

western Russia. Because the fundamental problem

of the izba was heating it, conservation of heat

during the six months of the heating season (pri-

marily October through March) was the major

structural issue. There were several solutions. One

was to chink the spaces between the logs with moss

and mud. The second was the so-called “Russian

stove,” typically a large, three-chambered object

made of various combinations of stone, mud, brick,

and cement. Its three chambers extracted most of

the heat before it reached the smoke hole and ra-

diated it out into the room. The third solution for

saving heat was not to have any form of chimney

(and only a few small windows), because typically

eighty percent of the heat generated by a stove or

an open hearth in the middle of the room will be

lost if there is a chimney venting the stove or a

hole in the roof to exhaust the smoke. Such a large

percentage of heat is lost because of the require-

ment of a “draw” to pull the smoke upward and

out of the izba.

The consequences of this third form of izba

heating were numerous. For one, there was soot

scattered throughout the izba, typically with a line

around the walls, about waist-high, marking

where the bottom of the smoke typically was. The

smoke had two basic harmful constituents: carbon

monoxide gas and more than two hundred vari-

eties of particulate matter. The harm this did to

peasant health and the amount by which it reduced

residents’ energy have not been calculated. Gov-

ernment officials beginning at least as early as the

reign of Nicholas I were concerned about the health

impact of the smoky hut, and by 1900 most were

gone, though some lingered on into the 1930s. That

IZBA

693

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

peasants thereafter were able to afford the fuel to

compensate for the heat lost through chimneys in-

dicates that peasant incomes were rising.

The other features of the izba were benches

around the room, on which the peasants sat dur-

ing the day and on which many of them slept at

night. The most honored sleeping places were on

top of the stove. These places were reserved for the

old people, an especially relevant issue after the in-

troduction of the household tax in 1678, which

forced the creation of the extended Russian family

household and increased the mean household size

from four to ten. This packing of so many people

into the izba must have increased the communica-

tion of diseases significantly, another consequence

of the izba that remains to be calculated.

The Russian word for “table” (stol) is old, go-

ing back to Common Slavic, whereas the word for

chair (stul) only dates from the sixteenth century.

These facts correspond with historians’ general un-

derstandings: most peasant izby had tables, but

many probably did not have chairs. Ceilings were

introduced in some huts around 1800, pushing the

smoke all the way down to the floor. Before 1800

the huts all had pitched roofs and the smoke would

rise up under the roof and fill the space from the

underside of the roof down to where the smoke line

was. With the introduction of the ceiling, that cav-

ity was lost and the smoke went down to the floor.

Goods were stored in trunks.

See also: PEASANTRY; SERFDOM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hellie, Richard. (2001). “The Russian Smoky Hut and Its

Probable Health Consequences.” Russian History

28(1–4):171–184.

R

ICHARD

H

ELLIE

IZVESTIYA

The newspaper Izvestiya was first published on Feb-

ruary 28, 1917, by the Petrograd Soviet of Work-

ers and Soldiers’ Deputies formed during the

February Revolution. The paper’s name in Russian

means “Bulletin,” and it first appeared under the

complete title “Bulletin of the Petrograd Soviet of

Workers’ Deputies.” Immediately upon seizing

power in October 1917, the Bolsheviks appointed

their own man, Yuri Steklov, editor-in-chief. In

March 1918 the newspaper’s operations were

transferred to Moscow along with the Bolshevik

government. From an official standpoint the news-

paper became the organ of the Central Executive

Committee of the Soviets-the leading organ of the

Soviet government, as opposed to the Communist

Party.

For the first ten years of its existence, the pa-

per relied heavily on the equipment and personnel

from the prerevolutionary commercial press. In

Petrograd, Izvestiya was first printed at the former

printshop of the penny newspaper Copeck (Kopeyka),

and until late 1926 many of its reporters were vet-

erans of the old Russian Word (Russkoye slovo).

Throughout the Soviet era Izvestiya, together

with the big urban evening newspapers such as

Evening Moscow (Vechernaya Moskva) was known as

a less strident, less political organ than the official

party papers such as Pravda. Particularly in the

1920s but also later, the paper carried miscella-

neous news of cultural events, sports, natural dis-

asters, and even crime. These topics were almost

entirely missing from the major party organs by

the late 1920s. In the late 1920s head editor Ivan

Gronsky pioneered coverage of “man-against-

nature” adventure stories such as the Soviet rescue

of the crew of an Italian dirigible downed in the

Arctic. Later dubbed “Soviet sensations” by journal-

ists, such ideologically correct yet thrilling stories

spread throughout the Soviet press in the 1930s.

In part as a result of its less political role in the

Soviet press network, Josef Stalin and other Cen-

tral Committee secretaries tended to be suspicious

of Izvestiya. The editorial staff was subjected to a

series of purges, beginning with the firing of “Trot-

skyite” journalists in 1925, and continuing in 1926

with the firing of veteran non-Communist jour-

nalists from Russkoye slovo. In 1934 the Party Cen-

tral Committee appointed Stalin’s former rightist

political opponent Nikolai Bukharin to the head ed-

itorship. However in 1936 and 1937, Bukharin,

former editor Gronsky, and many other senior ed-

itors were purged in the Great Terror. Bukharin

was executed; Gronsky and others survived the

Stalinist prison camps.

During the Thaw of the late 1950s and early

1960s, the editor-in-chief of Izvestiya was Alexei

Adzhubei, Nikita Khrushchev’s son-in-law, who

used the paper to advocate de-Stalinization and

Khrushchev’s reforms. Under Adzhubei, Izvestiya

writers practiced a “journalism of the person,”

which presented “heroes of daily life” and exposed

IZVESTIYA

694

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the problems of ordinary Soviet subjects. Adzhubei

was removed from the editorship in 1964 when

Khrushchev fell, but Thomas Cox Wolfe has argued

that the “journalism of the person” laid important

ideological groundwork for Mikhail Gorbachev’s

perestroika reform program in the second half of

the 1980s.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Izvestiya

made a successful transition to operation as a pri-

vate corporation.

See also: ADZHUBEI, ALEXEI IVANOVICH; JOURNALISM;

UNIVERSITIES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kenez, Peter. (1985). The Birth of the Propaganda State:

Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917–1929.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lenoe, Matthew. (1997). “Stalinist Mass Journalism

and the Transformation of Soviet Newspapers,

1926–1932.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of

Chicago.

Wolfe, Thomas Cox. (1997). “Imagining Journalism:

Politics, Government, and the Person in the Press in

the Soviet Union and Russia, 1953–1993.” Ph.D.

diss., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

M

ATTHEW

E. L

ENOE

IZYASLAV I

(1024–1078), grand prince of Kiev and progenitor

of the Turov dynasty.

Before Yaroslav Vladimirovich “the Wise” died

in 1054, he designated his eldest living son, Izyaslav,

as grand prince of Kiev. Izyaslav and his younger

brothers Svyatoslav and Vsevolod ruled as a tri-

umvirate for some twenty years. During that time

they asserted their authority over all the other

princes and defended Rus against the nomadic

Polovtsy (Cumans). However, Izyaslav’s rule in

Kiev was insecure. In 1068, after he was defeated

by the Polovtsy and refused to arm the Kievans,

the latter rebelled, and he fled to the Poles. Because

his brother Svyatoslav refused to occupy the

throne, Izyaslav returned to Kiev in 1069 with the

help of Polish troops. Two noteworthy events oc-

curred during his second term of rule. In 1072 he

and his brothers transported the relics of Saints

Boris and Gleb into a new church that he had

built in Vyshgorod. They also compiled the so-

called “Law Code of Yaroslav’s Sons” (Pravda

Yaroslavichey). In 1073, however, Izyaslav quar-

reled with his brothers. They drove him out of Kiev

and forced him to flee once again to Boleslaw II of

the Poles. Failing to obtain help there, he traveled

to Western Europe, where he sought aid unsuc-

cessfully from the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV

and from Pope Gregory VII. He finally returned to

Kiev after his brother Svyatoslav died there in 1076.

His last sojourn in Kiev was also short: on Octo-

ber 3, 1078, he was killed in battle fighting his

nephew Oleg, Svyatoslav’s son.

See also: GRAND PRINCE; KIEVAN RUS; YAROSLAV

VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dimnik, Martin. (1994). The Dynasty of Chernigov

1054–1146. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediae-

val Studies.

Franklin, Simon, and Shepard, Jonathan. (1996). The

Emergence of Rus 750–1200. London: Longman.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

IZYASLAV MSTISLAVICH

(c. 1096–1154), grandson of Vladimir Vsevolodo-

vich “Monomakh” and grand prince of Kiev.

Between 1127 and 1139, when his father

Mstislav and his uncle Yaropolk ruled Kiev, Izyaslav

received, at different times, Kursk, Polotsk, south-

ern Pereyaslavl, Turov, Pinsk, Minsk, Novgorod,

and Vladimir in Volyn. In 1143 Vsevolod Olgovich,

grand prince of Kiev, gave him southern Pereyaslavl

again, but his uncle Yuri Vladimirovich “Dolgo-

ruky” of Suzdalia objected, fearing that he would

use the town as a stepping-stone to Kiev. After

Vsevolod died in 1146, the Kievans, despite having

pledged to accept his brother Igor as prince, invited

Izyaslav to rule Kiev because he belonged to their

favorite family, the Mstislavichi. But his reign was

insecure, because the Davidovichi of Chernigov and

Yuri challenged him. In 1147, in response to a plot

by the Davidovichi to kill Izyaslav and reinstate

Igor, whom Izyaslav was holding captive, the

Kievans murdered Igor. Meanwhile Yuri argued that

Monomakh’s younger sons, Izyaslav’s uncles, had

prior claims to Izyaslav, in keeping with the lateral

system of succession to Kiev that Yaroslav

Vladimirovich “the Wise” had allegedly instituted in

his so-called testament. Yuri and his allies waged

war on Izyaslav and expelled him on two occasions.

Finally, in 1151, Izyaslav invited Vyacheslav, Yuri’s

IZYASLAV MSTISLAVICH

695

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

elder brother, to rule Kiev with him. Yuri ac-

knowledged the legitimacy of Vyacheslav’s reign

and allowed Izyaslav to remain co-ruler of Kiev un-

til his death on November 13, 1154. Izyaslav’s reign

was exceptional in that, in 1147, he ordered a synod

of bishops to install Klim (Kliment) Smolyatich as

the second native metropolitan of Kiev.

See also: KIEVAN RUS; YAROSLAV VLADIMIROVICH.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hanak, Walter K. (1980). “Iziaslav Mstislavich.” The

Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History, ed.

Joseph L. Wieczynski, 15:88–89. Gulf Breeze, FL:

Academic International Press.

Martin, Janet. (1995). Medieval Russia 980–1584. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

M

ARTIN

D

IMNIK

IZYASLAV MSTISLAVICH

696

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

JACKSON-VANIK AGREEMENT

The Jackson-Vanik Amendment to the U.S.-Soviet

Trade Bill, which became law in 1974, was to play

a major role in Soviet-American relations until the

collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Jack-

son-Vanik Amendment had its origins in 1972. In

response to the sharp increase in the number of

Soviet Jews seeking to leave the Soviet Union, pri-

marily because of rising Soviet anti-Semitism, the

Brezhnev regime imposed a prohibitively expen-

sive exit tax on educated Jews who wanted to

leave. In response, Senator Henry Jackson of the

State of Washington introduced an amendment to

the Soviet-American Trade Bill, linking the trade

benefits Moscow wanted (most favored nation

treatment for Soviet exports and U.S. credits) to

the exodus of Soviet Jews. Jackson’s amendment

quickly got support in Congress, as Representa-

tive Charles Vanik of Ohio introduced a similar

amendment in the U.S. House of Representatives.

The Soviet leadership, which might have thought

that a trade agreement with the Nixon Adminis-

tration would conclude the process, belatedly

woke up to the growing Congressional opposition.

After initially trying to derail the Jackson-Vanik

amendment by threatening that it would lead to

an increase in anti-Semitism both in the Soviet

Union and the United States, the Soviet leaders be-

gan to make concessions. At first they said there

would be exemptions to the head tax, and then

they put the tax aside as the Soviet-American

Trade Bill neared passage in Congress in 1974. At

the last minute, however, Senator Adlai Steven-

son III, angry at Soviet behavior during the Yom

Kippur War of 1973 when Moscow had cheered

the Arab oil embargo against the United States,

introduced an amendment limiting U.S. credits to

the Soviet Union to only $300 million over four

years, and prohibiting U.S. credits for developing

Soviet oil and natural gas deposits. The Soviet

leadership, which had been hoping for up to $40

billion in U.S. credits, then repudiated the trade

agreement. However, the impact of the Jackson-

Vanik Amendment remained. Thus whenever

Moscow sought trade and other benefits from the

United States, whether in the 1978–1979 period

under Brezhnev, or in the 1989–1991 period un-

der Gorbachev, Jewish emigration from the Soviet

Union soared, reaching a total of 213,042 in 1990

and 179,720 in 1991.

See also: JEWS; UNITED STATES, RELATIONS WITH

J

697

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Freedman, Robert O., ed. (1984). Soviet Jewry in the De-

cisive Decade, 1971–1980. Durham: Duke University

Press.

Freedman, Robert O., ed. (1989). Soviet Jewry in the 1980s.

Durham: Duke University Press.

Korey, William. (1975). “The Story of the Jackson

Amendment.” Midstream 21(3):7–36.

Orbach, William. (1979). The American Movement to Aid

Soviet Jews. Amherst: University of Massachusetts

Press.

Stern, Paula. (1979). Water’s Edge: Domestic Politics and

the Making of American Foreign Policy. Westport, CT:

Greenwood Press.

R

OBERT

O. F

REEDMAN

JADIDISM

The term jadidism is used to describe a late-

nineteenth and early-twentieth-century project to

modernize Turkic Islamic cultures within or indi-

rectly influenced by the Russian Empire. Emerging

between the 1840s and 1870s among a small num-

ber of intellectuals as a fragmented but spirited call

for educational reform and wider dissemination of

practical knowledge by means of the modern press,

jadidism became by the early twentieth century a

socially totalizing movement that was epistemo-

logically rationalist and ultimately revolutionary

in its expectations and consequences.

The successes of European and Russian ad-

vances into all of the historic centers of world

civilization, beginning with the Portuguese explo-

rations of the fifteenth century and lasting through

the final stage of the Russian conquest of Central

Asia in the 1880s, instigated reactions abroad that

ranged from indifference to multiple forms of re-

sistance and accommodation.

In those regions with historically deep literate

cultures (China, India, and the Islamic lands from

Andalusia to Central Eurasia and beyond), interac-

tion with the West encouraged some intellectuals

to question the efficacy for the unfolding modern

age of arguably timeless cultural canons, centuries

of commentaries, and classical forms of education,

as well as political, economic, and social norms and

practices. They concluded that modernity, as de-

fined by what Europeans were capable of accom-

plishing and how they made their lives, was a goal

toward which all peoples had to strive, and that its

pursuit required reform of indigenous cultures, if

not their abandonment, with at least a degree of

imitation of Western ways.

Within the Turkic communities of the Russian

Empire, beginning with groups inhabiting the

Volga-Ural region, Crimea, the Caucasus, and the

Kazakh Steppe, the lures of modernity stimulated

such reformist sentiments. The early advocates, all

Russophiles, included Mirza Muhammad Ali Kazem

Beg (1802–1870), Abbas Quli Aga Bakikhanli

(1794–1847), Mirza Fath-Ali Akhundzade (1812–

1878), Hasan Bey Melikov Zardobi (1837–1907),

Qokan Valikhanov (1835–1865), Ibrai Altynsarin

(1841–1889), Abdul Qayyum al-Nasyri (1824–

1904), and Ismail Bey Gaspirali (1851–1914). These

men, for the most part isolated from one another

temporally and geographically, articulated critiques

of the Islamic tradition that held intellectual and in-

stitutional sway over their separate societies. This

critique did not decry Islamic ethics, nor did it deny

historic achievements wherever Islam had taken

root. Rather, it approached Islam from a rational-

ist perspective that reflected the influence of West-

ern intellectual tendencies, through a Russian prism,

emanating from the seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries. This perspective viewed religion as so-

cially constructed and not divinely ordained, as one

more aspect of human experience that could and

should be subjected to scientific inquiry and reex-

amination, and as a private, personal matter rather

than a public one. For these men, who represent the

first jadidists, the properly functioning, productive,

competitive, and modern society was secular,

guided but not trumped at every turn by religion.

The popular appeal of jadidism remained lim-

ited and diffused prior to the turn of the twentieth

century. Projects for educational reform and pub-

lishing ventures were either short-lived or unful-

filled. The persistence of Ismail Bey Gaspirali in both

areas proved a turning point, with his new-method

schools (the first opened in 1884) establishing a

model and his newspaper Perevodchik/Tercuman

(The Interpreter, 1883-1918) becoming the first

Turkic-language periodical in the Russian Empire

to survive more than two years. These successes

and the effects of social, economic, and political tur-

moil, which gained momentum across the empire

between 1901 and 1907, helped expand the social

base and influence of jadidism, leading to a prolif-

eration of publications, regional and imperial-wide

gatherings, and involvement in the newly created

State Duma.

JADIDISM

698

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

For a brief period, jadidism seemed to have come

of age, but its apparent triumph disguised underly-

ing confusion over its long-term goals and mean-

ing. First, growing participation in the movement

by Islamic clerics, some remarkably educated and at-

tuned to early-twentieth-century realities, seemed

fortuitous, but their attempts to reconcile Islam with

the modern age, to draw analogies with the Chris-

tian Reformation and raise the specter of Martin

Luther, and to persist in the goal of keeping Islam

at the center of society ran against the fundamen-

tally secular spirit of jadidism. Second, the jadidist

founding fathers had accepted, for practical reasons

if not genuine sympathy, Russian political author-

ity and the need for close cooperation with the dom-

inant Russian population. After 1905, such political

accommodation seemed less persuasive to a new

generation enervated by the patent weaknesses of

the monarchy and the equally visible power of the

people to influence imperial affairs. Finally, jadidism

always spoke to a universal way of life that tran-

scended the limitations of any particular religion, in-

tellectual tradition, culture, or time. In post-1905

Russia, the appeal of local and regional ethnic iden-

tities overwhelmed this universalism and its moder-

ating spirit, replacing it with romantic notions of

primordial ethnicity, nationalism, and the nation-

state. Against such forces, jadidism, as conceived by

its putative founders, proved inadequate; by 1917,

it had all but disappeared from the public discourse

of Central Eurasia.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jersild, Austin. (1999). “Rethinking from Zardob: Hasan

Melikov Zardabi and the ‘Native’ Intelligentsia.” Na-

tionalities Papers 27:503–517.

Khalid, Adeeb. (1998). The Politics of Muslim Cultural Re-

form: Jadidism in Central Asia. Berkeley: University

of California Press.

Lazzerini, Edward J. (1992). “Beyond Renewal: The Ja-

did Response to Pressure for Change in the Modern

Age.” In Muslims in Central Asia: Expressions of Iden-

tity and Change, ed. Jo Ann Gross. Durham, NC:

Duke University Press.

E

DWARD

J. L

AZZERINI

JAPAN, RELATIONS WITH

Russian-Japanese relations throughout the twenti-

eth century were characterized by hostility, mu-

tual suspicion, and military conflict. Foreign pol-

icy perceptions, policies, and behaviors shaped the

relationship, as did personalities, issues, and dis-

putes—most notably the dispute over the four Kuril

islands, or northern territories, in Japanese par-

lance. Japan and the USSR emerged from World

War II with radically different views of security:

the former inward-looking and defensive, with

constrained military capabilities; the latter out-

ward-looking, offensive, and militaristic. The

Japanese were convinced that internal law and jus-

tice dictated the return of the southern Kurils, while

the Soviets asserted that territory acquired by war

could not be relinquished. Post-Soviet Russia has

been more amenable to discussing the territorial is-

sue, but progress has been glacial.

Russian explorers first pushed southward from

Kamchatka into the Kuril island chain, encounter-

ing Japanese settlers in the late seventeenth and

early eighteenth centuries. The two countries even-

tually agreed on a border, with the 1855 Treaty of

Shimoda granting Etorofu and the islands south of

it to Japan. Russia’s push into Manchuria and con-

struction of the Chinese Eastern Railway late in the

nineteenth century threatened Japan’s growing

JAPAN, RELATIONS WITH

699

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

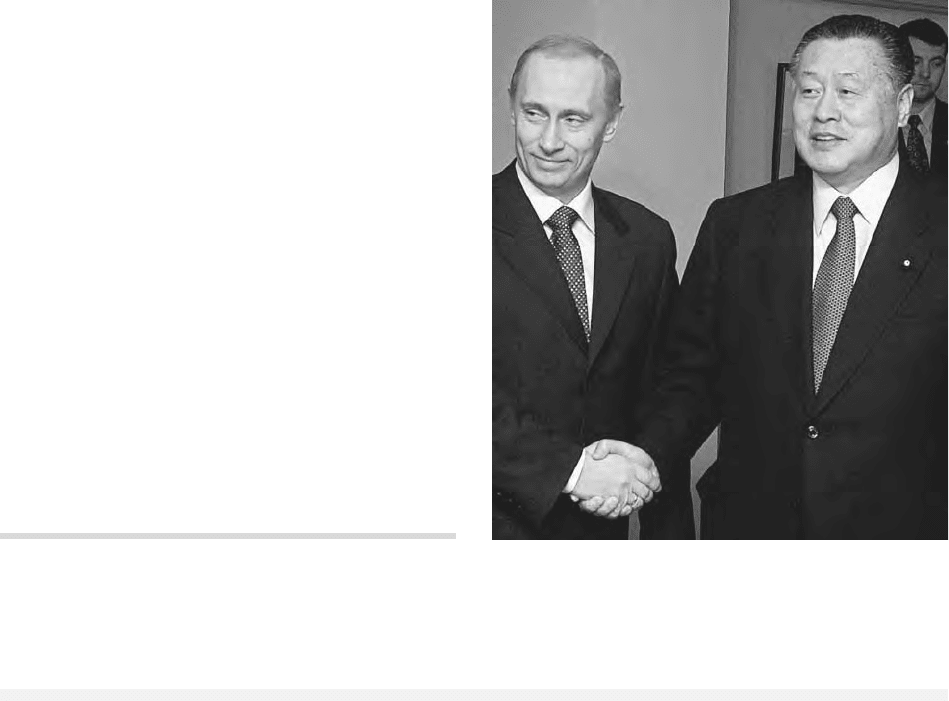

Russian president Vladimir Putin and Japanese prime minister

Yoshiro Mori confer in Irkutsk, Russia, March 25, 2001. © AFP/

CORBIS

imperial interests in China and led to the Russo-

Japanese War of 1904–1905. The 1905 Treaty of

Portsmouth, brokered by U.S. president Theodore

Roosevelt, ended the war and gave Japan control

of coal-rich Sakhalin south of the fiftieth parallel

along with the adjacent islands.

Formally Russia’s ally during World War I,

Japan became alarmed at the Bolshevik coup in

1917 and subsequently deployed some 73,000

troops to protect its interests in the Russian Far

East. Japan withdrew from Russia in 1922 but ne-

gotiated concessions for natural resources in north-

ern Sakhalin. Tensions remained high during most

of the interwar period, and there were armed

clashes along the Soviet border with Japanese-

occupied Manchuria between 1937 and 1939.

Moscow and Tokyo negotiated a neutrality pact in

April 1941. The two armies clashed only during

the final days of the war, as the Red Army swept

through Manchuria and occupied all of Sakhalin

and the Kurils. Nearly 600,000 Japanese soldiers

and civilians were captured and interned in Soviet

labor camps; roughly one-third of them perished

in Siberia.

Relations between Japan and the USSR during

the Cold War were tense and distant. The Soviet

government refused to sign the Japanese Peace

Treaty at the 1951 San Francisco Conference, which

in any event failed to specify ownership of Sakhalin

and the Kurils. Differing interpretations over sov-

ereignty of the islands would preclude a Russo-

Japanese peace treaty well into the twenty-first

century. The Soviet-Japanese Joint Declaration of

1956 normalized relations and proposed the return

of Shikotan and the Habomais (an idea quashed by

U.S. secretary of state John Foster Dulles), but it

failed to solve the territorial issue. Moscow objected

to the U.S.-Japan security relationship, and from

the 1960s through the 1980s targeted part of its

substantial military force deployed in the Russian

Far East toward Japan.

For much of the postwar era Russo-Japanese

relations reflected the competition between the So-

viet Union and the United States. For Washington,

Japan was the key ally against Communist ex-

pansion in the western Pacific. The Soviet leader-

ship in the Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev

eras seems to have regarded Japan as merely an ex-

tension of the United States, and consistently

blamed Japan for the poor state of Russo-Japanese

relations. Stalemate on the territorial issue served

American interests by maintaining confrontation

between Japan and Russia, ensuring the Soviets

would need to commit resources to protect their

sparsely populated eastern borders.

Moscow’s leadership refused to acknowledge

Japan as a significant international actor in its own

right, even as the country developed into an export

powerhouse with the world’s second largest econ-

omy. Moscow’s approach to Japan must be viewed

in the context of Soviet global and regional con-

siderations, especially the Cold War competition

with America and, after 1961, the deterioration of

ties with Communist China. The Kremlin’s foreign

policy architects generally viewed Japan with dis-

dain. They seldom relied on the considerable ex-

pertise of the USSR’s Japan specialists and

frequently pursued contradictory goals with regard

to Japan.

Cultural distance also may explain part of the

antipathy between Russia and Japan. Public opin-

ion surveys indicate that Russia consistently ranks

at the top of countries most disliked by Japanese.

Russians are considerably more favorably inclined

to Japan, but in many respects their two civiliza-

tions are very different. Tellingly, the collapse of

the Soviet Union was not enough to provoke a sud-

den upsurge of pro-Russian sentiment, as it did in

much of Europe and the United States.

Not until Mikhail Gorbachev’s “new thinking”

did Soviet foreign policy show much flexibility to-

ward Japan. Gorbachev and his foreign minister

Eduard Shevardnadze were more attentive to their

Asia specialists, but they ranked Japan relatively

low on the list of foreign policy priorities, after ties

with the United States, Europe, and China. By the

time Gorbachev visited Tokyo in April 1991, his

freedom to maneuver was constrained by a back-

lash from conservatives in Moscow that, combined

with growing nationalist and regional opposition,

made any progress on the territorial issue virtually

impossible.

Russo-Japanese relations did not improve

markedly after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Russian president Boris Yeltsin’s 1993 meeting with

Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa produced the Tokyo

Declaration, in which the two sides pledged to ne-

gotiate the territorial issue on the basis of histori-

cal facts and the principles of law and justice. But

the two sides interpreted these terms differently.

Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto (1996–1998)

tried a package approach to relations, bundling a

wide range of issues including trade, energy, secu-

rity, and cultural exchanges, and he came closer to

reaching an accord than had any previous Japan-

JAPAN, RELATIONS WITH

700

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ese leader. But the flurry of informal summits and

intensified diplomatic activity in the late 1990s

failed either to deliver a peace treaty or to enhance

economic cooperation.

Prospects for trade and investment improved

early in the twenty-first century as Tokyo urged

Moscow to approve a Siberian oil pipeline to the

eastern coast, competing with a Chinese bid for a

route to Daqing. Relations were said to be entering

a new, businesslike phase following the January

2003 summit between President Vladimir Putin

and Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. But as in

the latter half of the twentieth century, the terri-

torial dispute remained the touchstone for Russo-

Japanese relations.

See also: KURIL ISLANDS; RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ivanov, Vladimir I., and Smith, Karla S., eds. (1999).

Japan and Russia in Northeast Asia: Partners in the

21st Century. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Kimura, Hiroshi. (2000). Distant Neighbors, Vol. 1: Japan-

ese-Russian Relations under Brezhnev and Andropov;

Vol. 2: Japanese-Russian Relations under Gorbachev

and Yeltsin. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Nimmo, William F. (1994). Japan and Russia: A Reeval-

uation in the Post-Soviet Era. Westport, CT: Green-

wood.

Rozman, Gilbert, ed. (2000). Japan and Russia: The Tor-

tuous Path to Normalization, 1949-1999. New York:

St. Martin’s Press.

C

HARLES

E. Z

IEGLER

JASSY, TREATY OF

During the eighteenth century, Russia and Turkey

fought repeatedly for hegemony on the Black Sea

and in adjacent lands, including the Pontic steppe.

Russia’s growing power became truly dominant

during Catherine II’s Second Turkish War, when

the military-administrative talents of Grigory

Alexandrovich Potemkin and the generalship of

Alexander Vasilievich Suvorov and Nikolay Vasi-

lyevich Repnin finally brought Turkey to its knees.

In a treaty negotiated successively by Potemkin and

Aleksandr Andreyevich Bezborodko at Jassy in

modern Romania, Sultan Selim III’s representative,

Yusof Pasha, agreed with terms that essentially ac-

knowledged Russia’s stature as a Black Sea power.

Potemkin died before the treaty was signed on

January 9, 1792, but his absence did not affect the

outcome. Russia agreed to withdraw its troops

from south of the Danube, and Turkey recognized

Russian annexation of the Crimea and lands be-

tween the Bug and Dniester rivers. Both parties rec-

ognized the Kuban River as their mutual boundary

in the foothills of the Caucasus, while Turkey

agreed to restrain raids on Georgia and Russia’s

Kuban territories. The southern steppe now came

under full Russian control, with a subsequent blos-

soming of settlement and commercial activities. The

Russians now also had both naval bases on the

Black Sea and a territorial springboard for further

military action, either in the Caucasus or in the

Balkans. The Treaty of Jassy thus marked a major

milestone in the titanic struggle between Russia and

Turkey for empire in the Black Sea basin.

See also: POTEMKIN, GRIGORY ALEXANDROVICH; RUSSO-

TURKISH WARS; TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, John T. (1989). Catherine the Great: Life and

Legend. New York: Oxford University Press.

Menning, Bruce W. (2002). “Paul I and Catherine II’s

Military Legacy, 1762–1801.” In The Military His-

tory of Tsarist Russia, eds. Frederick W. Kagan and

Robin Higham. New York: Palgrave.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

JEWS

The Russian Empire acquired a Jewish population

through the partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793,

and 1795. By 1800 Russia’s Jewish population

numbered more than 800,000 persons. During the

nineteenth century the Jews of the Russian Empire

underwent a demographic explosion, with their

population rising to more than five million in 1897

(a number that does not include the approximately

one million persons who emigrated from the em-

pire prior to 1914). Legislation in 1791, 1804, and

1835 required most Jews to live in the provinces

acquired from Poland and the Ottoman Empire in

the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the

so-called Pale of Jewish Settlement. There were also

some residence restrictions within the Pale, such as

a ban on settlement in most districts of the city of

Kiev, and restrictions on settlement within fifty

kilometers of the foreign borders. The Temporary

JEWS

701

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Laws of May 1882 forbade new Jewish settlement

in rural areas of the Pale. Before 1882 the Russian

state progressively permitted privileged categories

of Jews (guild merchants, professionals, some

army veterans, students, and master-craftsmen) to

reside outside the Pale. Larger in size than France,

the Pale included areas of dynamic economic

growth, and its restrictions were widely evaded,

JEWS

702

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Jewish bystanders are attacked by an angry mob after someone throws a bomb during the Christian Corpus Domini procession in

Bielostok, June 1906. © M

ARY

E

VANS

P

ICTURE

L

IBRARY