Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

but it was nonetheless considered the single great-

est legal liability on Russian Jews. The regulations

of the Pale, including the May Laws, did not apply

to Jews in the Kingdom of Poland, although they

too were barred from settlement in the Great Russ-

ian provinces.

ECONOMIC LIFE

Jews were primarily a trade-commercial class,

serving in the feudal economy as the link between

the peasants and the market, and as agents of the

noble landowners and leasees of the numerous mo-

nopolies on private estates. They were particularly

active in the production and sale of spirits, as agents

of noble and state monopolies on this trade. Indi-

vidual Jewish families lived in peasant villages,

while larger communities were found in market

towns, the shtetl of Jewish lore.

The Jewish population increase and internal

migration contributed to the growth of urban cen-

ters such as Odessa, Kiev, Vilna, Warsaw, and Lodz.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Jews

moved into occupations in urban-based factory

work. A small elite gained prominence as tax farm-

ers, bankers, railway contractors, and industrial

entrepreneurs. A number of Jews had successful

careers in the professions, chiefly law, medicine,

and journalism. Most Jews, however, lived lives of

relative poverty.

RELIGION AND CULTURE

The vernacular of Jews in the empire comprised

various dialects of Yiddish, a Germanic language

with a substantial admixture of Hebrew and Slavic

languages. Hebrew and Aramaic were languages of

prayer and study. In the all-Russian census of 1897

more than 97 percent of Jews declared Yiddish their

native language, although this figure obscures the

high level of multi-lingualism among East Euro-

pean Jewry.

The empire’s Jews were, with very few excep-

tions, Ashkenazi-a Yiddish-speaking cultural com-

munity that shared common rituals and traditions.

It was a highly literate culture that valorized

learning and the study of legal and homiletic texts,

the Talmud. Ashkenazi culture also included ele-

ments of the Jewish mystical tradition, the Kab-

balah. The main division between adherents to

religious traditionalism in Eastern Europe was be-

tween the so-called Mitnagedim, (The Opponents)

and the Hasidim (The Pious Ones). The latter con-

tained many strands, each grouped around a

charismatic leader, or tzaddik (righteous man).

There was also a small band of maskilim, the ad-

herents of Haskalah, which was the Jewish version

of the European Enlightenment movement. They

advocated religious reform and intellectual and lin-

guistic acculturation.

In an effort to reach the non-acculturated

masses, followers of the Russian Haskalah wrote

literary works in Yiddish and Hebrew, helping to

create standardized and modernized versions of

both languages. The most notable of these writers

were Abraham Mapu, Perez Smolenskin, and

Reuven Braudes in modern Hebrew; Sholem Yakov

Abramovich (pen name, Mendele Moykher-Sforim)

in Hebrew and Yiddish; and Sholem Rabinovich

(Sholem Aleichem) and Yitsak Leybush Perets in

Yiddish. Avraam Goldfaden was the foremost cre-

ator of a Yiddish-language theater, although its

growth was stunted by a governmental ban in

1883. The turn of the century saw the emergence

of a number of outstanding Hebrew poets, most

notably Khaim Nakhman Bialik and Shaul

Chernikhovsky. There was a vigorous Jewish press

in Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian, and Polish.

In response to the challenges of modernity, re-

ligious movements such as Israel Lipkin Salanter’s

Musar Movement, which penetrated traditional

study centers (yeshivas), sought ways to preserve

a vigorous traditional style of life. While women

were not expected to be scholars, many were liter-

ate. Both religious and secular literature aimed at

a female audience was published in Yiddish.

All young males were expected to study in re-

ligious schools known as the cheder. A state initia-

tive of 1844 created a state-sponsored Jewish

school system with primary and secondary levels,

offering a more modern curriculum. Total enroll-

ment was low, but the schools served Jews as a

point of entry into Russian culture and higher ed-

ucation. Most maskilim and acculturated Jews in

the mid-nineteenth century had some connection

with this school system. By the 1870s Jews in ur-

ban areas began to enter Russian schools in large

numbers. Concerned that the Jews were swamp-

ing the schools, the state imposed quotas on the

admission of Jews to secondary and higher educa-

tion. A number of Jews became prominent artists

in Russia, most notably the painter Isaac Levitan

and the sculptor Mark Antokolsky.

INTERNAL GOVERNMENT

Until 1844 the internal government of the Jews

comprised the kahal (kagal in Russian), a system

of autonomous local government inherited from

JEWS

703

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The kahal,

dominated by local elites, exercised social control,

selected the religious leadership (rabbis), and as-

sessed and collected taxes under a system of col-

lective responsibility. After 1827 the kahal also

oversaw the selection of recruits for the army. A

number of taxes were unique to the Jews, most

notably a tax on kosher meat (korobochka) and a

tax on sabbath candles. Jews in Poland and Lithua-

nia created a number of national bodies, the va’adim

(the singular form is va’ad), which assessed taxes

on communities, negotiated with the secular au-

thorities, and attempted to set social standards. Al-

though similar bodies were abolished in Poland in

1764, the Russian state allowed Jews to create them

on a regional basis. These included provincial ka-

hals, and the institution of Deputies of the Jewish

People, which lasted until 1825. Seen as an obsta-

cle to Jewish integration, the kahal system was

technically abolished in 1844, but virtually all of

its functions endured unchanged.

Within each community existed a wide vari-

ety of societies (hevrah, plural: hevrot) that over-

saw an extensive range of devotional, educational,

and charitable functions. The most important of

these was the burial brotherhood, the hevrah kad-

disha.

LEGAL STATUS

The defining characteristic of a Jew in Russian law

was religious confession; a convert from Judaism

to any other faith ceased legally to be a Jew. In

other respects Russian law possessed numerous and

contradictory provisions that applied only to Jews.

In Russia’s social-estate based system, almost all

Jews were classed as townspeople (meshchane) or

merchants (kuptsy), and the general regulations for

these groups applied to them, but with many ex-

ceptions. Confusingly, all Jews were also placed in

the social category of aliens (inorodtsy), which in-

cluded groups such as Siberian nomads, who were

under the special protection of the state. A huge

body of exceptional law existed for all aspects

of Jewish life, including tax assessment, military

recruitment, residence, and religious life. Jewish

JEWS

704

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

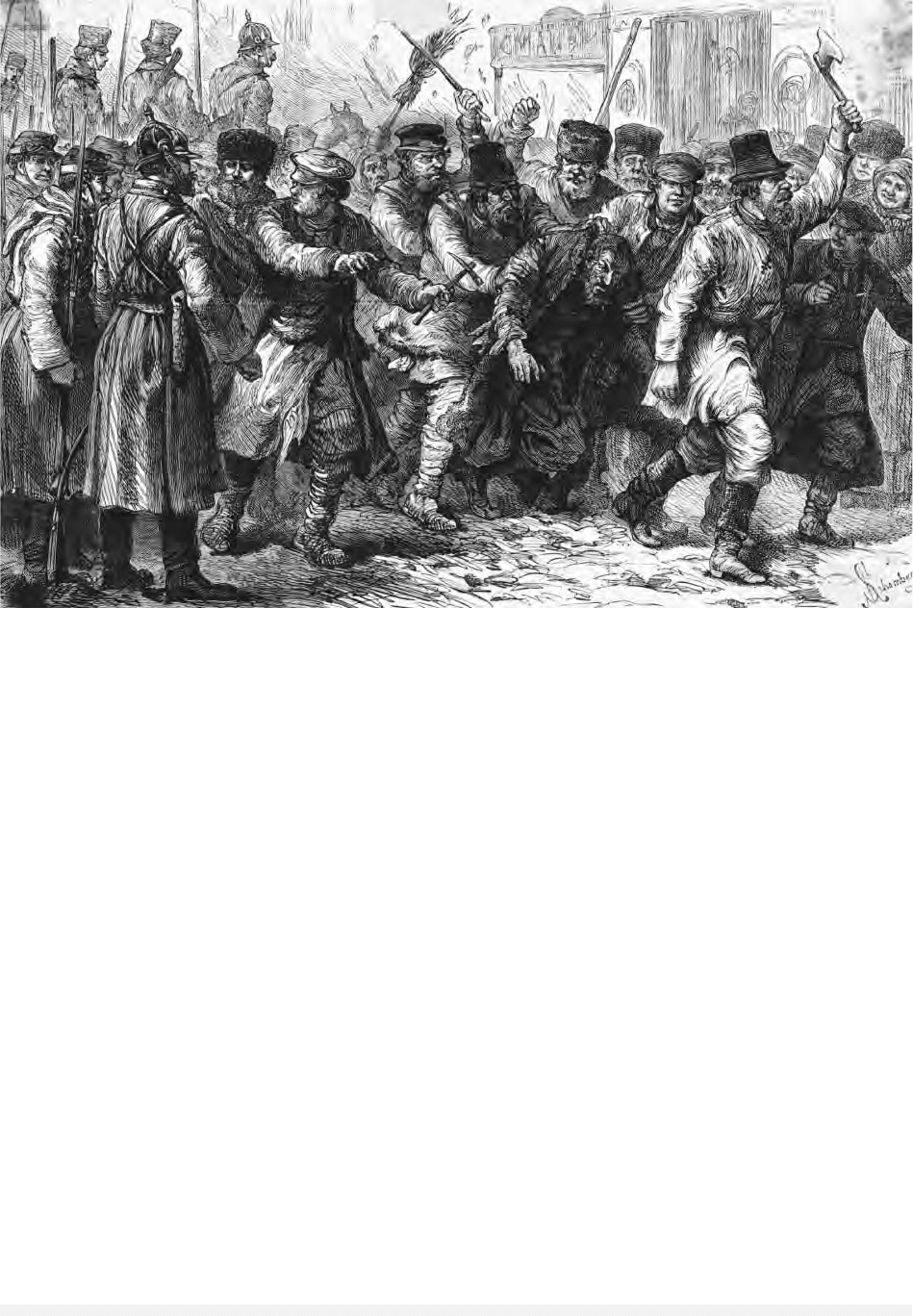

Russian Jews under assault while police look on with indifference, 1880s. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

emancipation in Russia would have had to encom-

pass the removal of all such special legislation.

THE “JEWISH QUESTION” IN RUSSIA

The guiding principles of Russia’s Jewish policy were

not based on traditional Russian, Orthodox Christ-

ian anti-Semitism, nor was there ever a sustained

and coordinated effort to convert all Jews to Rus-

sian Orthodoxy, with the exception of conversion-

ary pressures on Russian army recruits. Russian

policy was influenced by the Enlightenment-era cri-

tique of the Jews and Judaism that saw them as a

persecuted minority, but also isolated and backward,

economically unproductive, and religious fanatics

prone to exploit their Christian neighbors. In 1881

Russian policy was broadly aimed at the accultura-

tion and integration of the Jews into the broader so-

ciety. The anti-Jewish riots (pogroms) of 1881 and

1882 led to a reversal of this policy, inspiring efforts

to segregate Jews from non-Jews through residence

restrictions (the May Laws of 1882) and restricted

access to secondary and higher education. Much of

Russian legislation towards the Jews after 1889

lacked a firm ideological basis, and was ad hoc, re-

sponding to the political concerns of the moment.

Following the emancipation of the serfs in

1861, Russian public opinion, fearful of Jewish

exploitation of the peasantry, grew increasing

critical of the Jews. These critical attitudes were

characterized as Judeophobia. Originally based on

concrete, albeit exaggerated, socioeconomic com-

plaints (exploitation, intoxication of the peasantry),

Russian Judeophobia acquired fantastic elements

by the end of the century, exemplified by forgeries

like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which claimed

to expose a Jewish plot bent on world domination.

The presence of Jews in the revolutionary move-

ment led the state to attribute political disloyalty

to Jews in general. Right-wing political parties were

invariably anti-Semitic, exemplified by their rally-

ing cry, “Beat the Yids and Save Russia!”

Jews made significant contributions to all

branches of the Russian revolutionary movement,

including Populism, the Social Revolutionaries, and

Marxist Social Democracy, which included a Jew-

ish branch, the Bund, that concentrated on propa-

ganda among the Jewish working class. Lev Pinsker,

author of the 1882 pamphlet Auto-Emancipation!,

and Ahad Ha’am were major ideologues of the early

Zionist movement. East European Jews were the

mainstay of Theodor Herzl’s movement of politi-

cal Zionism.

See also: BUND, JEWISH; JUDAIZERS; NATIONALITIES POLI-

CIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST PALE

OF SETTLEMENT; POGROMS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aronson, I. Michael. (1990). Troubled Waters: The Origins

of the 1881 Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia. Pittsburgh,

PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Dubnow, S. M. (1916–1920). History of the Jews in Rus-

sia and Poland, 3 vols. Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Pub-

lication Society of America.

Frankel, Jonathan. (1981). Prophecy and Politics: Social-

ism, Nationalism, and the Russian Jews, 1862–1917.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Klier, John D. (1985). Russia Gathers Her Jews: The Ori-

gins of the Jewish Question in Russia. DeKalb, IL:

Northern Illinois University Press.

Klier, John D. (1995). Imperial Russia’s Jewish Question,

1885–1881. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Klier, John D., and Lambroza, Shlomo, eds. (1991).

Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian His-

tory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mendelsohn, Ezra. (1970). Class Struggle in the Pale. Cam-

bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Miron, Dan. (1996). A Traveler Disguised: The Rise of Mod-

ern Yiddish Fiction in the Nineteenth Century. Syracuse,

NY: Syracuse University Press.

Nathans, Benjamin. (2002). Beyond the Pale: The Jewish

Encounter with Late Imperial Russia. Berkeley and Los

Angeles: University of California Press.

Rogger, Hans. (1986). Jewish Policies and Right-Wing Pol-

itics in Imperial Russia. London and New York:

Macmillan.

Stanislawski, Michael. (1983). Tsar Nicholas I and the

Jews: The Transformation of Jewish Society in Russia,

1825–1855. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society

of America.

Tobias, Henry J. (1972). The Jewish Bund in Russia. Stan-

ford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Zipperstein, Steven J. (1986). The Jews of Odessa: A Cul-

tural History. Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press.

J

OHN

D. K

LIER

JOAKIM, PATRIARCH

(1620–1690), Ivan “Bolshoy” Petrovich Savelov (as

a monk, Joakim) was consecrated Patriarch Joakim

of Moscow and All Russia on July 26, 1674.

JOAKIM, PATRIARCH

705

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

When Patriarch Joakim assumed the post, the

Russian Church was experiencing increasing oppo-

sition. Joakim moved firmly but tactfully to ra-

tionalize the administrative structure of the church,

to bolster patriarchal finances, and to bring the in-

stitution under his control. Joakim’s administrative

reforms were complemented by efforts to revital-

ize the reform program begun at mid-century,

which included both liturgical and spiritual reform.

During Joakim’s tenure, liturgical reform contin-

ued, and sermons and other simple religious tracts

were composed, printed, and distributed in in-

creasing numbers. Joakim was also committed to

a program of education, under the control of the

church. Joakim’s ardent conviction that the church

alone could define doctrine and should control ed-

ucation generated opposition. Individuals and

groups, ranging from the original opponents of Pa-

triarch Nikon and their followers to disparate dis-

senters who did not conform to new practices,

vocally and sometimes violently opposed the litur-

gical and administrative changes effected by Patri-

arch Joakim and the church he led. When teaching,

preaching, and persuasion failed to convince oppo-

nents, the state stepped in to persecute and repress.

In the 1680s Joakim’s determination that a pro-

posed academy of higher learning be under patri-

archal control led to a clash with the monk

Sylvester Medvedev and a faction that enjoyed the

sympathy of the regent, Sophia Alexeyevna. This

conflict ripened into a dispute about the Eucharist

that drew in learned members of the clerical elite

in Ukraine. The debate threatened plans to subor-

dinate the Kievan see to the Moscow patriarchate.

Quickly it degenerated into polemics. The palace

coup of 1689 that brought Peter to the throne

ended the dispute. Patriarch Joakim’s support of

Peter assured his victory in this affair. Sylvester

Medvedev was arrested, then, almost a year after

Patriarch Joakim’s death, tried and executed. This

was a crude political resolution to what had begun

as a learned debate. As such, it undermined the le-

gitimacy of the church in the eyes of the educated.

Joakim died on March 17, 1690, shortly after the

coup, leaving a testament that manifested profound

anxiety for the future of both church and state.

Joakim has attracted little scholarly attention.

Discussions that relate to his patriarchate focus on

the increasing influence of Ukrainian churchmen

in Moscow, the struggle over the opening of an

academy in Moscow, the Eucharistic controversy

of the late 1680s, and the subordination of the

Kievan church to the Russian patriarch. Until re-

cently, the dominant theme in this literature was

the growing tension in Moscow as Old Muscovite

culture confronted Ukrainian Culture and as sup-

porters of a Greek direction for the Russian Church

came into conflict with those favoring an allegedly

Latin direction. Joakim traditionally was placed on

the side of the conservative, Old Muscovite, Greek

faction opposed to a progressive, Ukrainian, Latin

faction. An emerging body of related scholarship

questions this binary analysis, suggesting the need

for a more complex approach to the period and the

man.

See also: MEDVEDEV, SYLVESTER AGAFONIKOVICH; NIKON,

PATRIARCH; PATRIARCHATE; PETER I; RUSSIAN OR-

THODOX CHURCH; SOPHIA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Potter, Cathy Jean. (1993). “The Russian Church and the

Politics of Reform in the Second Half of the Seven-

teenth Century.” Ph.D. diss. Yale University, New

Haven, CT.

Vernadsky, George, ed. and tr. (1972). “Testament of Pa-

triarch Ioakim.” In A Source Book for Russian History.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

C

ATHY

J. P

OTTER

JOB, PATRIARCH

(d. 1607), first patriarch of the Russian Orthodox

Church.

Tonsured in the Staritsky Monastery around

1553, Job was appointed archimandrite by Tsar

Ivan IV in 1569. In 1571 he was transferred to

Moscow as prior of the Simonov Monastery, then

as head of the Novospassky Monastery

(1575–1580). Job was consecrated Bishop of

Kolomensk in April 1581, Archbishop of Rostov in

1586, and Metropolitan of Moscow in December

1586. On January 26, 1589, he was raised to the

position of Patriarch of All Russia by Patriarch Je-

remiah of Constantinople.

Job’s consecration as Russia’s first patriarch

was an event of national significance. The Russian

Church had formerly been under the jurisdiction of

Constantinople with the status of a metropoli-

tanate, but by the sixteenth century many Rus-

sians believed that Moscow was the last bastion of

true faith, a “Third Rome.” Hence the establishment

of an autocephalous church was considered neces-

sary for national prestige. During Russia’s civil war

JOB, PATRIARCH

706

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

in 1605, Job played a leading role by declaring the

Pretender “False Dmitry” a heretic and calling on

the people to swear allegiance to Tsar Boris Go-

dunov and his son Fyodor. Consequently, when

Dmitry became tsar in June 1605 Job was deposed

and exiled to Staritsky monastery. He died in 1607.

Although sometimes criticized by contempo-

raries and historians for his support of the Go-

dunovs, Job was known as a humble man of

impeccable morals, learned for his times, who

worked for the good of the church and the pro-

motion of Orthodox Christianity. In 1652 Job was

canonized as a saint by Patriarch Nikon, with the

approval of Tsar Alexei Mikhaylovich.

See also: DMITRY, FALSE; FYODOR IVANOVICH; GODUNOV,

BORIS FYODOROVICH; IVAN IV; METROPOLITAN;

NIKON, PATRIARCH; ORTHODOXY; PATRIARCHATE; SI-

MONOV MONASTERY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dunning, Chester. (2001). Russia’s First Civil War. Uni-

versity Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Vernadsky, George. (1969). The Tsardom of Moscow

1547–1682. 2 vols. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press.

D

EBRA

A. C

OULTER

JOSEPH OF VOLOTSK, ST.

(c. 1439–1515), coenobiarch and militant defender

of Orthodoxy.

Of provincial servitor origin, Ivan Sanin became

the monk Joseph (Iosif) around 1460 under the

charismatic Pafnuty of Borovsk. Having a robust

body, superb voice, powerful will, clear mind, ex-

cellent memory, and lucid pen, Joseph was forced

by Ivan III to succeed as abbot in 1477. They soon

quarreled over peasants, and in 1479 Joseph re-

turned with six seasoned colleagues to Volotsk to

start his own cloister under the protection of Ivan’s

brother Boris. Joseph attracted additional talent and

quickly developed his foundation into a center of

learning rivaling its model, Kirillov-Beloozersk.

Dionisy, the leading iconographer of the day,

painted Iosif’s Dormition Church gratis.

Joseph joined Archbishop Gennady’s campaign

against the Novgorod Heretics in the late 1480s. Mas-

terminding the literary defense of Orthodoxy, Joseph

personally persuaded Ivan III to sanction the synod

(1504), which condemned a handful of dissidents to

death and others to monastery prisons. The cele-

brated quarrel with Nil Sorsky’s disciple Vassian Pa-

trikeyev and the “Kirillov and Trans-Volgan Elders”

erupted soon after these executions, which, the lat-

ter argued, were not canonically justifiable.

In 1507, claiming oppression by his new local

prince, Joseph placed his monastery under royal pro-

tection. He was then excommunicated by his new

spiritual superior, Archbishop Serapion of Novgorod

(r. 1505–1509), for failing to consult him. Basil

III, Metropolitan Simon (r. 1495–1511), and the

Moscow synod of bishops backed Joseph and deposed

Serapion, but Joseph was tainted as the courtier of

the grand prince and as a slanderer, while Vassian’s

star rose. Nevertheless, the monastery continued to

flourish. As Joseph physically weakened, he formally

instituted the cogoverning council, which ensured

continuity under his successors.

Joseph’s chief legacies were the Iosifov-Voloko-

lamsk Monastery and his Enlightener (Prosvetitel) or

Book Against the Novgorod Heretics. Under his lead-

ership the cloister innovated and rationalized the

lucrative commemoration services for the dead, pa-

tronized religious art, initiated one of the country’s

great libraries and scriptoria, and became a quasi-

academy, nurturing prelates for half a century.

Among his disciples and collaborators were the out-

standing ascetic Kassian Bosoi (d. 1531), who had

taught Ivan III archery and lived to help baptize

Ivan IV; a nephew, Dosifey Toporkov, who com-

posed the Russian Chronograph in 1512; the book-

copyist Nil Polev, who donated to Iosifov the

earliest extant copies of both Nil Sorsky’s and

Joseph’s writings; and Joseph’s enterprising suc-

cessor, the future Metropolitan Daniel.

The Enlightener, produced before 1490 and re-

vised through the year of Joseph’s death, was his

most authoritative and copied work. It served si-

multaneously as the foundation of Orthodoxy for

militant churchman and as a doctrinal and ethical

handbook for laity and clergy. Its dramatic and dis-

torted introductory “Account of the New Heresy of

the Novgorod Heretics” sets the tone of diabolic Ju-

daizers confronted by heroic defenders of the faith.

The eleven polemical-didactic discourses that fol-

low justify Orthodoxy’s Trinitarian and redemp-

tive doctrines (1–4), the veneration of icons and

other holy objects (5–7), the unfathomability of

the Second Coming and the authority of Scripture

JOSEPH OF VOLOTSK, ST.

707

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

and patristics (8–10), and monasticism (11). The

standard concluding part, either appended epistles

composed before the 1504 synod in the brief redac-

tion, or the four or five extra discourses of the post-

1511 extended redaction, defend the repression and

execution of heretics. Joseph’s conscious rhetorical

strategy of lumping all dissidence together allows

him to impute to the heretics the objections by fel-

low Orthodox to inquisitorial measures. Among his

notable assertions are that one should resist unto

death the blasphemous commands of a tyrant; that

killing a heretic by prayer or hands is equivalent;

that one should entrap heretics with divinely wise

tricks; and, most famous, that the Orthodox Tsar

is like God in his authority.

Joseph’s extended, fourteenth-discourse and

nine-tradition Monastic Rule, adumbrated in a brief,

eleven-sermon redaction, was Russia’s most de-

tailed and preaching work of its kind, but chiefly

an in-house work for his cloister. The blueprint for

the monastery’s success is contained in his polem-

ical claim to represent native traditions and his in-

sistence on attentiveness to rituals, modesty,

temperance, total obedience, labor, responsibility of

office, precise execution of commemorations, pro-

tection of community property, pastoral care, and

the council’s authority. In addition, ten of his ex-

tant epistles defend the monastery’s property in

concrete ways. Questionable sources from the

1540s and 1550s, connected with his followers’

struggles, also link him to the generic defense of

monastic property, supposedly at a church coun-

cil in 1503. He composed a variety of other admo-

nitions, including a call for price-fixing during a

local famine.

Canonized in 1591, Joseph was venerated also

by the Old Believers. The Russian Church today in-

vokes him as the “Russian star,” but some ob-

servers since the 1860s have considered his

ritualism and inquisitorial intolerance an unfortu-

nate phenomenon and legacy.

See also: BASIL III; CHURCH COUNCIL; DANIEL, METRO-

POLITAN; DIONISY; IVAN III; JUDAIZERS; ORTHODOXY;

POSSESSORS AND NON-POSSESSORS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goldfrank, David. (2000). The Monastic Rule of Iosif Volot-

sky, rev. ed. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications.

Luria, Jakov S. (1984). “Unresolved Issues in the History

of the Ideological Movements of the Late Fifteenth

Century.” In Medieval Slavic Culture, eds. Henrik

Birnbaum and Michael S. Flier, vol. 1 of 2. Califor-

nia Slavic Studies 12:150–171.

D

AVID

M. G

OLDFRANK

JOURNALISM

Russian journalism, both under the tsars and since,

has more often responded to state requirements

than it has exemplified the freedom of the press.

Moreover, not until a decade or so before the 1917

Revolution did a number of newspapers win mass

readerships by lively and extensive daily reporting

of domestic and foreign news.

Peter I (r. 1682–1725) started the first news-

paper in a small format, the St. Petersburg Bulletin,

and wrote for it himself to advance his reform pro-

gram. Later in the eighteenth century journals ap-

peared as outlets for literary and didactic works,

but they could not escape the influence of the state.

As part of her effort to enlighten Russia, Cather-

ine II (r. 1762–1796) launched All Sorts of Things

in 1769. This was a weekly publication modeled

on English satirical journals. Nicholas Novikov, a

dedicated Freemason, published his well-known

Drone on the presses of the Academy of Sciences,

providing outlet for pointedly critical comments

about conditions in Russia, including serfdom, but

he went too far, and the Empress closed down his

publishing activities.

In the early, reformist years of the reign of

Alexander I (1801–1825), a number of writers pro-

moted constitutional ideas in periodicals controlled

or subsidized by the government. Between 1804

and 1805, an education official named I. I. Mar-

tynov edited one such newspaper, Northern Mes-

senger, and promoted Western ideas. He portrayed

Great Britain as an advanced and truly free soci-

ety. Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin, the tsar’s

unofficial historian, founded Messenger of Europe

(1802–1820) to introduce Russian readers to Euro-

pean developments.

Among the reign’s new monthlies, those is-

sued by the Ministries of War, Public Education,

Justice, the Interior, and the Navy continued un-

til the 1917 Revolution. The Ministry of Foreign

Affairs published a newspaper in French. After the

Napoleonic wars, Alexander I backed a small news-

paper, Messenger of Zion, its main message being

that the promoters of Western European Enlight-

JOURNALISM

708

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

enment were plotting to subvert the Russian

church and state.

The reign of Nicholas I (1825–1855) saw com-

mercial successes by privately owned but pro-

government periodicals. For example, the Library for

Readers, founded by Alexander Filippovich Smirdin,

reached a peak circulation of seven thousand sub-

scribers in 1837. As the first of the so-called thick

journals that dominated journalism for about three

decades, each issue ran about three hundred pages

and was divided into sections on Russian literature,

foreign literature, science, art, and the like. Its size

and content made it especially appealing in the

countryside, where it provided a month’s reading

for landlord families. Works by virtually all of Rus-

sia’s prominent writers appeared in serial form in

such journals.

Smirdin also acquired Russia’s first popular,

privately owned daily newspaper, Northern Bee,

which was essentially a loyalist publication that

had permission to publish both foreign and do-

mestic political information. The Bee also had the

exclusive right to publish news of the Crimean

War, but only by excerpting it from the Ministry

of War’s official newspaper, Russian War Veteran.

During the war, the Bee achieved the unprecedented

readership of ten thousand subscribers.

Another major development was the growing

success in the 1840s of two privately owned jour-

nals, Notes of the Fatherland and The Contemporary.

Each drew readers largely by publishing the liter-

ary reviews of a formidable critic, Vissarion Belin-

sky, who managed to express his moral outrage at

human wrongs, despite the efforts of censors.

However, journalism turned from a literary em-

phasis to a more political one during the reign of

the tsar-reformer Alexander II (r. 1855–1881), who

emancipated some 50 million serfs and effected re-

forms in education, local government, the judi-

ciary, and the military, and relaxed the practice of

preliminary, or pre-publication, censorship. One of

his first steps in this regard was, in 1857, to per-

mit journalists to publicize the peasant emancipa-

tion question, a topic previously forbidden. The

next was allowing journalists to comment on how

best to reform the courts and local government.

JOURNALISM

709

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

A student browses through newspapers for sale at a St. Petersburg University kiosk, 1992. © S

TEVE

R

AYMER

/CORBIS

Journalists seized what was, on the whole, a

genuine expansion of free speech about public af-

fairs. They had as their ideal Alexander Herzen, the

emigre whose banned words they read in The Bell,

a Russian-language paper he produced in London

and smuggled into Russia. By keeping informed on

developments in Russia through correspondence

and visitors, Herzen published authoritative infor-

mation and liberal arguments, especially on the

emancipation of the serfs, and influenced many

who served under Alexander II. Meanwhile, Niko-

lai Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky, an erudite man

who read several languages, became Russia’s lead-

ing political journalist through the pages of The

Contemporary; and he, like Herzen, wove in relevant

events from Western Europe to shape public and

government opinion on reform issues. Another

such journalist, Dmitry Pisarev, wrote many of his

major pieces in prison, and published them in the

other major radical journal within the Empire,

Russian Word; however, he espoused the nihilist po-

sition of accepting nothing on faith but, rather,

testing all accepted truths and practices by the crit-

ical tools of reason and science. In line with the

view of a liberal censor at that time, Alexander

Vasilevich Nikitenko, higher censorship officials

suspended both journals for eight months in 1862

and later permanently closed them.

Through his new censorship statute of 1865,

widely hailed as a reform, Alexander II unleashed

a major expansion of the commercial daily press,

which was concentrated in Moscow and the capi-

tal, St. Petersburg. During the last decade of the

previous reign, only six new dailies (all in the

special-interest category) had been allowed, but of-

ficials now approved sixty new dailies in the first

decade under Alexander II, and many of these were

granted permission to publish not just general news

but also a political section. In 1862, private dailies

received permission to sell space to advertisers, a

right that allowed lower subscription fees. The new

income source prompted the publisher of Son of the

Fatherland to change it from a weekly to a daily,

and it soon acquired twenty thousand subscribers,

well over half of them in the provinces.

By Western standards, however, overall circu-

lation levels remained modest, even as more and

more newspapers became commercially successful

in the 1860s. Andrei Alexandrovich Kraevsky’s

moderate daily, Voice, saw profits grow as readers

increased to ten thousand by the close of the 1860s.

Moscow Bulletin, edited by Michael Katkov, who

leased it in 1863 and changed it from a weekly to

a daily, doubled its circulation to twelve thousand

in two years’ time, in part because of its ardently

nationalistic leaders, which were front-page opin-

ion pieces modeled on French feuilletons and writ-

ten by Mikhail Nikiforovich Katkov, known as the

editorial “thunderer.” Just as outspoken and pop-

ular were the leaders written in the capital for the

daily, St. Petersburg Bulletin, by Alexei Sergeyevich

Suvorin, who kept that conservative paper’s circu-

lation high. Readers preferring nationalistic and

slavophile journalism critical of the government

bought Ivan Aksakov’s Day (1865–1866) and then

his Moscow (1867–1869), its end coming when the

State Council banned his daily and barred him from

publishing, citing his unrelenting defiance of cen-

sorship law.

Another boon for newspapers under Alexander

II was their new right, granted in the early 1860s,

to buy foreign news reports received in Russia by

the Russian Telegraph Agency (RTA, run by the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs), after such dispatches

had been officially approved. In this period, too,

publishers improved printing production by buy-

ing advanced equipment from Germany and else-

where in Europe, including typesetting machines

and rotary presses that that permitted press runs

in the tens of thousands. Publishers also imported

photographic and engraving tools that made pos-

sible the pictorial magazines and Sunday supple-

ments.

Following the politically-motivated murder of

Alexander II, his son and heir Alexander III (r. 1881-

1894) gave governors full right to close publica-

tions judged to be inciting a condition of alarm in

their provinces, without the approval of the courts.

But there were still possibilities for critical journal-

ists even at a time of conservative government poli-

cies. Nicholas K. Mikhailovsky, who espoused a

radical populist viewpoint, published in Notes of the

Fatherland until the government closed it in 1884.

Most of the staff moved to Northern Messenger,

which began publishing in 1885. After spending a

period in exile, Mikhailovsky joined the Messenger

staff and wrote later for two other populist jour-

nals, Russian Wealth and Russian Thought. He was

one of the outstanding examples of the legal pop-

ulist journalists and led the journalistic critique of

the legal Marxists.

During the early years of Nicholas II (r.

1894–1917), some Russian journalists promoted

anti-government political and social views in the

papers printed abroad by such illegal political par-

JOURNALISM

710

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

ties as the Social Democrats, the Socialist Revolu-

tionaries, and the Union of Liberation. The Social

Democrats, led by Vladimir Ilich Lenin, began Spark

in 1902 in London, its declared purpose being to

unseat the tsar and start a social revolution. Those

who backed Spark in Russia had to accept Spark’s

editorial board as their party’s leaders. When the

various anti-autocracy factions cohered as legal

parties in Russia following the Revolution of 1905,

each published its own legal newspaper. The Men-

sheviks launched Ray in 1912 and Lenin’s Bolshe-

viks started Pravda (Truth) in 1912, but the

government closed the latter in 1914. (Pravda

emerged again after the Revolution of 1917 as the

main outlet for the views of the ruling Commu-

nist Party). Another type of journalism was that

of Prince V. P. Meshchersky, editor of the St. Pe-

tersburg daily, The Citizen. Meshchersky accepted

money from a secret government “reptile” fund.

His publishing activities were completely venal, but

both Alexander II and Nicholas II supported him

because of his pro-autocracy, nationalistic views.

With mass publishing commonplace in the big

cities of Russia by 1900, publishers in those cen-

ters continued to increase readerships, some with

papers that primarily shocked or entertained. In the

first category was Rumor of St. Petersburg; in the

second, St. Petersburg Gazette, for which Anton

Chekhov wrote short stories pseudonymously. The

copeck newspapers of Moscow and St. Petersburg

provided broad coverage at little cost for urban

readers. Making a selling point of pictures and fic-

tion, by 1870 Adolf Fyodorovich Marks lined up nine

thousand paid subscriptions to meet the initial costs

of his illustrated magazine, The Cornfield, which

was the first of the so-called thin journals, and in-

creased readership to 235,000 by century’s turn.

The government itself entered into mass produc-

tion of its inexpensive newspaper for peasants, Vil-

lage Messenger, and achieved a press run of 150,000.

High reporting standards set by long-time pub-

lisher Alexei Sergeyevich Suvorin, on the other

hand, won a large readership for the conservative

New Times, the daily he had acquired in 1876. Re-

putedly the one paper read by members of the Im-

perial family, New Times merited respect for

publishing reporters such as Vasily Vasilevich

Rozanov, one of the best practitioners of the cryp-

tic news style typical in modern journalism. Impe-

rial funding to friendly publishers like Suvorin,

regardless of need, continued to 1917 through sub-

sidies and subscription purchases. (Other recipients

of lesser stature were Russian Will, Contemporary

Word, Voice of Moscow, and Morning of Russia.) An-

other paper receiving help from the government

was Russian Banner, the organ of the party of the

extreme right wing in Russia after 1905, the Union

of the Russian People. On the other end of the po-

litical spectrum, satirical publications targeting

high officials and Tsar Nicholas II flourished in the

years 1905 through 1908, though many were

short-lived. One count shows 429 different titles of

satirical publications during these years.

One outstanding newspaper, Russian Word of

Moscow, became Russia’s largest daily. Credit goes

to the publisher of peasant origins, Ivan D. Sytin,

who followed the journalistic road urged on him

by Chekhov by founding a conservative daily in

1894 and transforming it into a liberal daily out-

side party or government affiliations. Sytin was

no writer himself, but in 1901 he hired an excel-

lent liberal editor, Vlas Doroshevich, who became

one of Russia’s most imitated journalists and a

prose stylist whom Leo Tolstoy ranked as second

only to Chekhov. Doroshevich gained the title king

of feuilletonists by dealing with important issues

in an engaging, chatty style. As editor of Word, he

ordered each reporter to make sense of breaking

events by writing as if he were the reader’s infor-

mative and entertaining friend. At the same time

he barred intrusion by the business office into the

newsroom, and kept Sytin to his promise not to

interfere in any editorial matters whatsoever.

Through these journalistic standards, Doroshevich

built Russian Word into the only million-copy daily

published in Russia prior to the Revolution of

1917.

Pravda, not Russian Word, however, would be

the paper that dominated the new order established

by Lenin’s Bolsheviks. In the early twenty-first

century, the front section of the building that

housed Word abuts the building of Izvestiia, an-

other Bolshevik paper from 1917 that has, in its

post-communist incarnation, become one of Rus-

sia’s great newspapers. Pravda, the huge Soviet-

era daily with a press-run of more than six million,

was first and foremost the organ of the Central

Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR

and it perpetuated Lenin’s idea that the press in a

socialist society must be a collectivist propagan-

dist, agitator, and organizer. Other newspapers

during the Soviet era were bound to follow

Pravda’s political line, expressed in the form of long

articles and the printing of speeches of high offi-

cials, and to promote the achievements of Soviet

life. Regional and local papers, little distinguishable

JOURNALISM

711

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

from Pravda in format, had leeway to cover local

news, and specialized papers had scope to intro-

duce somewhat different coverage, as well. In any

event, the agitational purpose of Soviet papers

meant that Western concepts of independent re-

porting and confidentiality of sources had no place

in journalism in the USSR.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991,

the new Constitution of the Russian Federation, ap-

proved by popular referendum on December 12,

1993, recognized freedom of thought and speech,

forbade censorship, and guaranteed “the right to

freely seek, obtain, transmit, produce, and dissemi-

nate information by any legal method.” The Con-

stitution prohibited the creation of a state ideology

that could limit the functioning of the mass media.

Within months, in June of 1994, the Congress of

Russian Journalists insisted that journalists resist

pressure on the reporting of news from any source.

Russian journalists, working to these high

standards, have sometimes paid a price for their

commitment to objective reporting. Journalist

Anna Politkovskaya, for writing critical dispatches

from Chechnya for the small, biweekly newspaper

New Gazette, was detained for a period by the FSB,

the federal security service, and received numerous

threats to her personal security. When Gregory

Pasco, the naval officer turned journalist, exposed

nuclear waste dumping in the Pacific Ocean by the

Russian fleet, a court convicted him of treason.

Other Russian journalists who engaged in forth-

right reporting have been killed under mysterious

circumstances.

Major Russian newspapers have not managed

to establish their own financial independence, be-

cause they are owned by wealthy banks and re-

source companies closely connected to the federal

government. Most newspapers outside of Moscow

and St. Petersburg (from 95 to 97% of them, ac-

cording to the Glasnost Foundation) are owned or

controlled by governments at the provincial or re-

gional level. One of their tasks is to assist in the re-

election of local officials. Overall, only a handful of

newspapers in Russia are independent journalistic

voices in the early twenty-first century. On the

other hand, controls on journalism in Russia are

no longer monolithic, as in the Soviet era, and cit-

izens of the Russian Federation had access to var-

ied sources of news reports in the print and

electronic media. The Internet newspaper lenta.ru,

for instance, offers coverage comparable to a West-

ern paper.

See also: BELINSKY, VISSARION GRIGORIEVICH; CENSOR-

SHIP; CHERNYSHEVSKY, NIKOLAI GAVRILOVICH; HERZEN,

ALEXANDER IVANOVICH INTELLIGENTSIA; KATKOV,

MIKHAIL NIKIFOROVICH; MIKHAILOVSKY, NIKOLAI

KONSTANTINOVICH; NEWSPAPERS; SUVORIN, ALEXEI

SERGEYEVICH; SYTIN, IVAN DMITRIEVICH; THICK

JOURNALS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ambler, Effie. (1972). Russian Journalism and Politics: The

Career of Aleksei S. Suvorin, 1861–1881. Detroit:

Wayne State University Press.

McReynolds, Louise. (1991). The News under Russia’s Old

Regime: The Development of a Mass Circulation Press.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Norton, Barbara T., and Gheith, Jehanne M., eds. (2001).

An Improper Profession: Women, Gender, and Journal-

ism in Late Imperial Russia. Durham, NC: Duke Uni-

versity Press.

Ruud, Charles A. (1982). Fighting Words: Imperial Cen-

sorship and the Russian Press, 1804–1906. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press.

C

HARLES

A. R

UUD

JUDAIZERS

A diverse group of heretics in Novgorod (c. 1470–

1515), sometimes referred to as the Novgorod-

Moscow heretics.

The Judaizing “heresy” arose in Novgorod in

the years 1470 and 1471, after a Kievan Jew named

Zechariah (Skhary) proselytized the priest Alexei,

who in turn enticed the priest Denis and many oth-

ers, including the archpriest Gavril, into Judaism.

Around 1478, Ivan III, who had just subjugated

Novgorod, installed them in the chief cathedrals of

the Moscow Kremlin. In 1484 or 1485, the influ-

ential state secretary and diplomat Fyodor Kurit-

syn and the Hungarian “Martin” joined with Alexei

and Denis and eventually attracted, among others,

Metropolitan Zosima (r. 1490–1494), as well as

Ivan III’s daughter-in-law Elena of Moldavia,

Meanwhile, Archbishop Gennady of Novgorod (r.

1484–1504) discovered the Novgorod heretics and

started a campaign against them, which was later

taken up by Joseph of Volotsk. Synods were held

in Moscow in 1488 and 1490, leading to an auto-

da-fé in Novgorod and to the imprisonment of De-

nis and several others. Alexei had already died,

however, and several others, like the historiographer-

copyist Ivan Cherny, fled. Joseph’s faction forced

JUDAIZERS

712

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY