Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Party and little to do with the SRs. When Lenin was

wounded in August 1918, Kaplan’s nervous be-

havior at the scene led to her arrest, although it

subsequently emerged that no one had actually

witnessed her role in the shooting. She was exe-

cuted within days of being apprehended. Bolshevik

authorities labeled Kaplan an SR and the attempt

on Lenin’s life an SR terrorist conspiracy; SR lead-

ers strongly denied both accusations during their

show trial in 1922.

See also: ANARCHISM; LENIN, VLADIMIR ILICH; SHOW TRI-

ALS; SOCIALIST REVOLUTIONARIES; TERRORISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jansen, Marc. (1982). A Show Trial under Lenin: The Trial

of the Socialist Revolutionaries, Moscow 1922, tr. Jean

Sanders. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Lyandres, Semion. (1989). “The 1918 Attempt on the Life

of Lenin: A New Look at the Evidence.” Slavic Review

48(3):432–48.

S

ALLY

A. B

ONIECE

KARACHAI

The Karachai are a small Turkic nationality of the

central North Caucasus. They speak a language

from the Kypchak group of the Altaic language

family and are closely related to the Balkars. They

inhabit high-elevation mountain valleys of the up-

per Kuban and Teberda river basins, and their pas-

tures once stretched up to the peaks and glaciers of

the northern slope of the Great Caucasus moun-

tain range.

Their remote origins can be traced to Kypchak-

speaking pastoralist groups such as the Polovt-

sians, who may have been forced to take refuge

high in the mountains by the Mongol invasions in

thirteenth century. At some point before the six-

teenth century, the Karachai came under the dom-

ination of the princes in Kabarda. The Crimean

khanate claimed nominal jurisdiction over much

of the northwest Caucasus and, correspondingly,

Karachai territories, until its demise in 1782. Con-

version to Islam took place gradually, gaining mo-

mentum during the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries. A series of military incursions into their

territories motivated several Karachai elders to sign

a capitulation agreement and nonaggression pact

with Russian forces in 1828. Although they were

officially considered subjects of the tsar from that

moment, various forms of resistance to Russian

rule continued until 1864. A Karachai-Cherkess

autonomous region was established in 1922 and

in 1926 was divided into two distinct units.

Karachai territories were occupied by the forces of

Nazi Germany between July 1942 and January

1943. While many Karachai men served in the Red

Army, others joined bandit and anti-Soviet parti-

san groups. In the fall of 1943 the Supreme So-

viet of the USSR ordered the deportation of the

Karachai people for alleged cooperation with the

Germans and participation in organized resistance

to Soviet power. The Karachai autonomous region

was abolished in 1944 and virtually the entire

Karachai population was deported to Kyrgyzstan

and Kazakhstan. In 1956 party members and Red

Army veterans were allowed to return to their

homeland, and in 1957 others were legally given

the right to return. In 1957 the joint Karachai-

Cherkess autonomous region was reestablished

and the mass return of the Karachai was initiated.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Karachai-

Cherkess autonomous region became a republic of

the Russian Federation.

Traditionally, Karachais subsisted on a combi-

nation of agriculture and stock-raising. As late as

the first decades of the twentieth century, only one-

fourth of all Karachai had adopted a completely

stationary lifestyle. The rest of the population sea-

sonally relocated from summer to winter pastures

with their herds of horses, cattle, sheep, and goats.

During the Soviet period, the Karachai remained

one of the least urbanized groups: Less than 20 per-

cent lived in cities. Clans were a central component

of traditional Karachai social organization. Al-

though some clans and their elders could be recog-

nized as more prominent or senior than others, the

Karachai did not have a powerful princely elite or

nobility. In the twentieth century the Karachai pop-

ulation grew from about 30,000 to about 100,000.

A Karachai literary language was developed and

standardized in the 1920s.

See also: CAUCASUS; CHERKESS; ISLAM; NATIONALITIES

POLICIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Wixman, Ronald. (1980). Language Aspects of Ethnic Pat-

terns and Processes in the North Caucasus. Chicago:

University of Chicago.

B

RIAN

B

OECK

KARACHAI

723

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

KARAKALPAKS

Karakalpaks are a Turkic people who live in Cen-

tral Asia. Of the nearly 500,000 Karakalpaks, more

than 90 percent live in northwestern Uzbekistan,

in the Soviet-created Karakalpak Autonomous Re-

public (KAR). Other Karakalpaks live elsewhere

in Uzbekistan, as well as in Kazakhstan, Turk-

menistan, Russia, and Afghanistan. Most adhere to

Sunni Islam, although Sufi sects have also attracted

many followers. They speak a language that is

closely related to Kazakh and Kyrgyz.

Most historians trace the Karakalpaks’ origins

to Persian and Mongolian peoples living on the

steppes of Central Asia and Southern Russia. Their

name literally meets “black hatted,” and mention

of a tribe thought to be ancestral to today’s

Karakalpaks first appears in Russian chronicles (as

Chorniye Kolbuki) in 1146. Renowned for their

military prowess, this group allied themselves with

the Kievan princes in their battles with other Russ-

ian princes and tribes of the steppes. In the 1200s

some Karakalpaks joined the Mongol Golden Horde,

and by the 1500s they enjoyed a short-lived inde-

pendence. Over time, however, they became sub-

jects of other Central Asian peoples and eventually

the Russians, who pushed into Central Asia in the

1800s.

In 1918 they were included with other Central

Asian peoples in the Turkistan Autonomous Re-

public, and in 1925 a Karakalpak Autonomous

Oblast was created in the Kazakh Autonomous So-

viet Socialist Republic. This oblast eventually be-

came the KAR, and in 1936 it became part of the

Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. Under Soviet rule,

Karakalpaks were encouraged to move to the KAR,

their nominal homeland.

The post-Soviet period found most Karakalpaks

desperately poor, living in an environmentally dev-

astated area adjacent to the rapidly shrinking Aral

Sea. Serious health problems such as hepatitis, ty-

phoid, and cancer are widespread. Despite their no-

madic traditions, their economy is dominated by

agriculture, especially cotton production, which

has suffered due to water shortages, soil erosion,

and environmental damage. Because of lack of in-

vestment in the region, the KAR’s relations with the

central Uzbek government have been strained.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM; NATIONALITIES POLICIES,

SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST; UZBEK-

ISTAN AND UZBEKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hanks, Reuel. (2000). “A Separate Peace? Karakalpak Na-

tionalism and Devolution in Post-Soviet Uzbek-

istan.” Europe-Asia Studies 52: 939–53.

P

AUL

J. K

UBICEK

KARAKHAN DECLARATION

In the Karakhan Manifesto of 1919, the Soviet gov-

ernment offered to annul the unequal treaties im-

posed on China by Imperial Russia. The declaration,

signed by Deputy Commissar of Foreign Affairs Lev

M. Karakhan , included rights of extraterritoriality

for Russians in China, economic concessions, and

Russia’s share of the Boxer rebellion indemnity.

Though dated July 25, 1919, it was not actually

published for another month. Civil war prevented

its delivery to China, but the Beijing authorities

soon learned its substance.

Controversy arose because the document was

prepared in two versions. One variant contained the

statement that “the Soviet Government returns to

the Chinese people, without any compensation, the

Chinese Eastern Railway [CER]. . . .” The version

published in Moscow in August 1919 did not in-

clude this provision, but the copy that was deliv-

ered to Chinese diplomats in February 1920 did

incorporate the offer to return the CER. However,

a Soviet proposal on September 27, 1920, for a

Sino-Russian agreement made no mention of re-

turning the Chinese Eastern Railway, but requested

a new agreement for its joint administration by the

two nations. All subsequent Soviet reprintings of

the Karakhan Manifesto omit the offer to return

the CER, while a Chinese reprinting of the docu-

ment in 1924 included the offer. The existence of

two versions manifests the ambiguity in Soviet pol-

icy toward the Far East in 1919 and 1920, arising

from the unpredictable course of the civil war and

foreign intervention. Thereafter, the consolidation

of Bolshevik power in Siberia, combined with con-

tinuing instability in China, led Moscow to seek

some degree of control over the economically and

strategically important CER.

See also: CHINA, RELATIONS WITH; CIVIL WAR OF

1917–1922; RAILWAYS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Degras, Jane, ed. (1951). Soviet Documents on Foreign Pol-

icy, Vol. 1: 1917–1924. London: Oxford University

Press.

KARAKALPAKS

724

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Leong, Sow-theng. (1976). Sino-Soviet Diplomatic Rela-

tions, 1917–1926. Honolulu: University Press of

Hawaii.

T

EDDY

J. U

LDRICKS

KARAMZIN, NIKOLAI MIKHAILOVICH

(1766–1826), writer, historian, and journalist.

Born in the Simbirsk province and educated in

Moscow, Nikolai Karamzin served only briefly in

the military before retiring to devote himself to in-

tellectual pursuits. In 1789 he undertook a jour-

ney to western Europe, visiting several luminaries,

including Immanuel Kant, on his way. Reaching

Paris in the spring of 1790, he witnessed history

in the making. He described his trip in his Letters

of a Russian Traveler, published upon his return in

1790 in a series of journals he founded himself. The

Letters display an urbane, westernized individual in

command of several languages and behavioral

codes and are meant to signal Russia’s coming of

age. They demonstrate a keen interest in history,

but primarily as a collection of anecdotes.

The short stories Karamzin wrote in the 1790s

exerted tremendous influence on the development

of nineteenth-century fiction. Karamzin’s main

purpose in literature and journalism was to pro-

mote a culture of politeness. History became one

of the main themes of his works, which grappled

with the paradoxes of modernity: The systematic

debunking of myths, inspired by a commitment to

reason, clashed with a need to mythologize the past

to throw into relief the moral and intellectual

emancipation enabled by the Enlightenment.

Karamzin elaborated a new political stance

while editing the Messenger of Europe in 1802 and

1803. A professed realist, he argued for a strong

central government, whose legitimacy would lie in

balancing conflicting interests and preventing the

emergence of evil. Karamzin grew disenchanted

with Napoleon, who had first seemed to bring forth

peace and stability, but his infatuation with con-

solidated political power endured.

In October 1803, Karamzin became official his-

toriographer to Tsar Alexander I. He uncovered

many yet unknown sources on Russian history,

including some that subsequently perished in the

Moscow fire of 1812. In 1811 Karamzin submit-

ted his Memoir on Ancient and New Russia, which

contained a biting critique of the policies of Alexan-

der I, but vindicated autocracy and serfdom. The

Memoir signaled Karamzin’s turn away from an En-

lightenment-inspired universalist notion of history

and affirmed the distinctness of Russia’s historical

path.

In 1818 Karamzin published the first eight vol-

umes of his History of the Russian State, an instant

bestseller. The History consists of two parts: a naive-

sounding account of events, close in style to the

Chronicles, with minimal narratorial intrusions and

an apparent lack of overriding critical principle; and

extensive footnotes, which display considerable skep-

ticism in the handling of sources and sometimes con-

tradict the main narrative. The narrative rests on the

notion that the course of events is vindicated by their

outcome—the consolidation of the Russian auto-

cratic state—but it lets stories speak for themselves.

Due to this narrative and political stance, the

immediate reception of the History was mostly neg-

ative. Yet after the publication of three more volumes

from 1821 to 1824, which included a condemna-

tion of the reign of Ivan the Terrible, the reception

began to shift (the last volume was published

posthumously in 1829). Alexander Pushkin called

the History “the heroic deed of an honest man,” and

Karamzin’s stance of moral independence came to

the foreground. The History continued to be read in

the nineteenth century, primarily as a storehouse

of patriotic historical tales. It fell into disfavor dur-

ing Soviet times, yet met an intense period of re-

newed interest in the perestroika years as part of

an exhumation of national history.

See also: ENLIGHTENMENT, IMPACT OF; HISTORIOGRAPHY;

NATIONALISM IN THE ARTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Black, J.L., ed. (1975). Essays on Karamzin: Russian Man-

of-Letters, Political Thinker, Historian, 1766–1826.

The Hague: Mouton.

Wachtel, Andrew Baruch. (1994). An Obsession with His-

tory: Russian Writers Confront the Past. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press.

A

NDREAS

S

CHÖNLE

KASYANOV, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH

(b. 1957), prime minister of the Russian Federation.

Kasyanov graduated from the Moscow Auto-

mobile and Road Institute and worked for the State

KASYANOV, MIKHAIL MIKHAILOVICH

725

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Construction Committee and Gosplan, State Plan-

ning Committee, from 1981 to 1990. He moved to

the economics ministry, and in 1993 Boris Fyodorov

brought him to the Finance Ministry to take charge

of negotiations over Russia’s foreign debts. Fluent in

English, Kasyanov became deputy finance minister

in 1995 and finance minister in May 1999. In Jan-

uary 2000 he was appointed first deputy prime min-

ister under prime minister and acting president

Vladimir Putin. Katyanov, praised by Putin as a

“strong coordinator, ” was named prime minister of

the government in May 2000, winning easy con-

firmation from the State Duma in a vote of 325 to

55. The calm, gravel-voiced Kasyanov was seen as

a figure with close ties to Boris Yeltsin’s inner cir-

cle—the owners of large financial industrial groups.

Despite repeated rumors of his impending dis-

missal, Kasyanov was still in office in mid-2003.

He oversaw cautious but substantial reforms in

taxation and the legal system, but liberals criticized

him for failing to tackle the “natural monopolies”

of gas, electricity, and railways. This led to some

embarrassing criticism from members of his own

administration, such as economy minister German

Gref and presidential economic advisor Andrei Il-

larionov, not to mention public admonition from

President Putin in spring 2003 for failing to deliver

more rapid economic growth. In Russia’s super-

presidential system, the job of prime minister is a

notoriously difficult one. Although the prime min-

ister has to be approved by the State Duma, once

in office he answers only to the president, and has

no independent power beyond that which he can

accumulate through skillful administration and

discreet political maneuvering.

See also: GOSPLAN; PUTIN, VLADIMIR VLADIMIROVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Shevtsova, Lilia. (2003). Putin’s Russia. Washington, DC:

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

P

ETER

R

UTLAND

KATKOV, MIKHAIL NIKIFOROVICH

(1818–1887), Russian journalist and publicist.

The son of a minor civil servant, Mikhail Niki-

forovich Katkov graduated from Moscow University

in 1838 and attended lectures at Berlin University

in 1840–1841. From 1845 to 1850 Katkov was an

assistant professor of philosophy at Moscow Uni-

versity. In 1851 he became editor of the daily

Moskovskie Vedomosti (Moscow News), and in 1856

he also became editor of the journal Russky Vestnik

(Russian Messenger).

Katkov changed his political preferences several

times during his life. In the 1830s he shared the ideas

of the Russian liberal and radical intelligentsia and

was close to the Russian literary critic Vissarion Be-

linsky, radical thinker Alexander Herzen, and the an-

archist Mikhail Bakunin. In the early 1840s Katkov

broke his connections with the radical intelligentsia,

instead becoming an admirer of the British political

system. During his early journalistic career, he sup-

ported the liberal reforms of Tsar Alexander II and

wrote about the necessity of transforming the Russ-

ian autocracy into a constitutional monarchy.

The Polish uprising had a great impact on the

changing of Katkov’s political views from liberalism

to Russian nationalism and chauvinism. He pub-

lished a number of articles favoring reactionary do-

mestic policies and aggressive pan-Slavic foreign

policies for Russia. The historian Karel Durman

wrote, “Katkov claimed to be the watchdog of the

autocracy and this claim was widely recognized.”

As one of the closest advisors of Tsar Alexander III,

Katkov had a great impact on Russian policies. Ac-

cording to the Ober-Procurator of the Holy Synod

Constantine Pobedonostsev, “there were ministries

where not a single important action was undertaken

without Katkov’s participation.” Durman points out

that in no other country could a mere publicist

standing outside the official power structure exer-

cise such an influence as had Katkov in Russia.

See also: ALEXANDER II; ALEXANDER III; INTELLIGENTSIA;

JOURNALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Durman, Karel. (1988). The Time of the Thunderer. Mikhail

Katkov, Russian Nationalist Extremism and the Fail-

ure of the Bismarckian System, 1871–1887. New York:

Columbia University Press.

Katz, Martin. (1966). Mikhail N. Katkov. A Political Biog-

raphy 1818–1887. Paris: Mouton & Co.

V

ICTORIA

K

HITERER

KATYN FOREST MASSACRE

Katyn Forest, a wooded area near the village of

Gneizdovo outside the Russian city of Smolensk,

KATKOV, MIKHAIL NIKIFOROVICH

726

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

was the scene in early 1940 of a wholesale killing

by the Soviet NKVD (Narodny Komissariat Vnu-

trennykh Del), or secret police, of 4,143 Polish

servicemen, mostly Polish Army officers. These vic-

tims, who had been incarcerated in the Kozielsk So-

viet concentration camp, constituted only part of

the genocide perpetrated against Poles by the NKVD

in 1939 and 1940.

The Poles fell as POWs into Soviet hands just

after the Soviet Red Army occupied the eastern half

of Poland under the terms of two notorious Molo-

tov-Ribbentrop pacts: the Nazi-Soviet agreements

signed between the USSR and Nazi Germany in Au-

gust and September 1939. The crime, committed

on Stalin’s personal orders at the opening of World

War II, is often referred to as the Katyn Massacre

or the Katyn Forest Massacre.

The incident was not spoken of for sixty years.

Even such Western leaders as President Franklin D.

Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston

Churchill placed little or no credence in reports of

the crime at the time, despite the fact that informed

Poles had provided proof. For his part, Churchill

urged exiled Polish officials such as Vladislav Siko-

rski to keep the incident quiet lest the news upset

the East-West alliance of the Soviet and Western

powers fighting Nazi Germany.

These first deaths came after one of the most

notorious of several repressions by the Stalin

regime against Poles. In 1939, notes Robert Con-

quest, besides the 440,000 Polish civilians sent to

Soviet concentration camps as a result of the So-

viet occupation of eastern Poland beginning in Sep-

tember, the Soviets took 200,000 POWs during the

Red Army’s campaign in Poland. Most of these of-

ficers and enlisted men of the Polish Army wound

up in camps at Kozielsk, Starobelsk, and Os-

tachkov. Of these, only forty-eight were ever seen

alive again. Later Stalin promised Polish officials

that the Soviet government would “look into” the

disappearance of these men. But Soviet officials re-

fused to discuss the matter whenever it was again

raised.

With the coming of World War II, that is, the

war between Germany and the USSR after June 21,

1941, the German Army swept into eastern Poland.

In 1943 the Germans, as occupiers of Poland, came

across the Polish corpses at Katyn. They duly pub-

licized their grim discovery to a skeptical world

press, blamed the Soviets for the terror, and shared

their find with a neutral European medical com-

mission based in Switzerland. The members of this

commission were convinced that the mass graves

were the result of Soviet genocide, but they voiced

their findings discreetly, sometimes refusing even

to give an opinion.

In 1944, when the Red Army retook the Katyn

area from the Wehrmacht, Soviet forces exhumed

the Polish dead. Again they blamed the Nazis. Many

people throughout the world supported the Soviet

line.

It was not until near the end of communist rule

in Russia in 1989 with the unfurling of the new

policy of glasnost (openness) in the USSR, that par-

tial admission of the crime was acknowledged in

Russia and elsewhere. Later, after the demise of

communist rule in Russia, two further sites were

found where Poles, including Jews, were executed.

The number of victims of the killings at all three

sites totaled 25,700.

See also: SOVIET-POLISH WAR; STALIN, JOSEF VISSARI-

ONOVICH; WORLD WAR II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Conquest, Robert. (1990). The Great Terror: A Reassess-

ment. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crozier, Brian. (1999). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Em-

pire. Rocklin, CA: Prima Publishing.

Crozier, Brian. (2000). “Remembering Katyn.” <http://

www-hoover.stanford.edu/publications/digest/002/

crozier.html>.

A

LBERT

L. W

EEKS

KAUFMAN, KONSTANTIN PETROVICH

(1818–1882), Russian general (of Austrian ances-

try) who became governor–general (viceroy) of

Turkestan following its conquest.

Konstantin Petrovich Kaufman’s fame came as

the ruler of Russia’s new colony in Central Asia.

His previous military experience had scarcely pre-

pared him for his career as creator of colonial

Turkestan. He trained as a military engineer and

served for fifteen years in the Russian army fight-

ing the mountain tribes in the Caucasus. His

achievements during his service there called him to

the attention of a fellow officer, General Dimitri

Milyutin. When Milyutin became minister of war

in the 1860s, he needed a trustworthy, experienced

officer to govern Turkestan. Kaufman was his

choice.

KAUFMAN, KONSTANTIN PETROVICH

727

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

At the time Kaufman received his appointment

in 1867, the conquest of Turkestan had only be-

gun. He became commander of the Russian fron-

tier forces there and had authority to decide on

military action along the borders of his territory.

When neighboring Turkish principalities began

hostile military action against Russia, or when fur-

ther conquests appeared feasible, Kaufman assumed

command of his troops for war. By the end of his

rule, Russia’s borders enclosed much of Central Asia

to the borders of the Chinese Empire. Only Khiva

and Bukhara remained nominally independent

khanates under Russian control. Turkestan’s bor-

ders with Persia (Iran) and Afghanistan were for

many years a subject of dispute with Great Britain,

which claimed a sphere of domination there.

Kaufman had charge of a vast territory far re-

moved from European Russia. Its peoples practiced

the Muslim religion and spoke Turkic or Persian

languages. It so closely resembled a colony, like

those of the overseas possessions of European em-

pires, that he took example from their colonial poli-

cies to launch a Russian civilizing mission in

Turkestan. He ended slavery, introduced secular

(nonreligious) education, promoted the scientific

study of Turkestan’s various peoples (even sending

an artist, Vasily Vereshchagin, to paint their por-

traits), encouraged the cultivation of improved

agricultural crops, and even attempted to emanci-

pate women from Muslim patriarchal control.

Kaufman’s means to achieve these ambitious goals

were meager, because of the lack of sufficient funds

and the paucity of Russian colonial officials. Also,

he feared that radical reforms would stir up dis-

content among his subjects. His fourteen-year pe-

riod as governor-general brought few substantial

changes to social and economic conditions in

Turkestan. However, it ended the era of rule by

Turkish khans and left Russia firmly in control of

its new colony.

See also: TURKESTAN

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barooshian, Voohan. (1993). V. V. Vereshchagin: Artist at

War. Gainsville: University Press of Florida.

Brower, Daniel. (2002). Turkestan and the Fate of the Russ-

ian Empire. Richmond, UK: Curzon Press.

MacKenzie, David. (1967). “Kaufman of Turkestan: An

Assessment of His Administration (1867–1881).”

Slavic Review 25 (2): 265–285.

D

ANIEL

B

ROWER

KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZAKHS

Kazakhstan, a Eurasian region inhabited since the

mid-1400s by the Kazakh people, comprises an

immense stretch of steppe that runs for almost

3,200 kilometers (2,000 miles) from the Lower

Volga and Caspian Sea in the west to the Altai and

Tien Shan mountain ranges in the east and south-

east. In the early twenty-first century, the Kazakh

republic serves as a bridge between Russian Siberia

in the north and the Central Asian republics of

Kirghizia/Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkme-

nia/Turkmenistan in the south. To the east it is

bounded by the region of the People’s Republic of

China that is known as Xinjiang (Sinkiang) or Chi-

nese Turkestan. With an area of some 2,71,500

square kilometers (1,050,000 square miles), Kaza-

khstan is almost twice the size of Alaska. As the

Kazakh SSR it was the largest republic in the USSR

next to the Russian Federation and was sometimes

known as the Soviet Texas. The climate is severely

continental, with January’s mean temperatures

varying from –18 degrees Celsius (0 degrees

Fahrenheit) in the north to –3 degrees C (27 degrees

F) in the south, and July’s from 19 degrees C (66

degrees F) in the north to 28–30 degrees C (83–86

degrees F) in the south. Annual precipitation in the

north averages 300 millimeters (11.7 inches), in the

mountains 1,600 millimeters (62 inches), and in

the desert regions less than 100 millimeters (3.9

inches). Fortunately, the region is one of inland

drainage with a number of rivers, the Irtysh, Ili,

Chu, and Syr Darya included, that flow into the

Aral Sea and Lake Balkhash. This permits the ex-

tensive irrigation that now threatens the Aral Sea

with extinction.

Originally peopled by the Sacae or Scythians,

by the end of the first century

B

.

C

.

E

. the area of

Kazakhstan was populated by nomadic Turkic and

Mongol tribes. Known to the Chinese as the Usun,

they were the ancestors of the later Kazakhs. First,

however, these tribes formed a succession of loose,

tribal-based confederations known as khaganates

(later khanates). Of these the most powerful was

the Turgesh (or Tiurkic) of the sixth century

C

.

E

.

Other nomadic empires followed its collapse in the

700s, beginning with the Karakhanids who ruled

southern Kazakhstan or Semireche from the 900s

to the 1100s. They were replaced by the Karakitai

(Kara Khitai), who succumbed to the Mongols dur-

ing 1219–1221. Subsequently these tribes were in-

cluded in the semiautonomous White Horde, which

was established by Orda, the eldest son of Genghis

KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZAKHS

728

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Khan’s eldest son Dzhuchi, as a component of the

more extensive Mongol Golden Horde. Having es-

tablished itself between the Altai Mountains and Syr

Darya River, the White Horde quickly gained con-

trol of Semireche and East Turkestan as well. But

if its rulers were descendants of the Mongol royal

line, most of its populace were ethnically Turkic.

With the collapse of that empire, these tribes

at first were subject to the Nogai Tatars, formerly

of the Golden Horde, and then of the Uzbeks. By

1447 the latter had conquered the territory between

the Syr Darya and Irtysh Rivers, the inhabitants

of whom became known as the Uzbek Kazakhs.

Yet the White Horde lingered, civil strife and fights

for power were constant, and in 1465 two of

its princes, the brothers Janibek (Dzhanibek) and

Gerei, led a number of Turkic tribes in a migration

southeast to Mogulstan (Mogolistan), which once

was part of the domain of Genghis Khan’s second

son Chagatai, and which now was an independent

state. They were welcomed by its ruler and given

lands on the Chu and Talas Rivers, where they

formed a powerful Kazakh khanate. By the late

1400s this had extended its power over much of

the formerly Uzbek-controlled Desht-i Kipchak, or

Kipchak Steppe. Over the next few decades most of

the Kazakh tribes—the Kipchaks, Usuns, Dulats,

and Naimans included—were united briefly under

Kasym Khan (1511–1518). He extended their power

southward while giving his subjects a period of rel-

ative calm. Internal strife then reemerged after his

death, and the Kazakh state began disintegrating as

its components joined with other tribes arriving

from the collapsing Nogai Horde. Having merged

during the 1600s they formed themselves into three

nomadic confederations known as “hordes” or

zhuzy (dzhuzy): the Ulu (Large, Great, or Senior)

in Semireche, the Kishiu (Small, Lesser, or Junior)

between the Aral and Caspian Seas, and the Orta

(Middle) in the central steppe. But taken together,

they were now an ethnically distinct people, known

to the Russians since the latter 1500s as the Kir-

giz-Kazakhs, with a social system based on the

families and clans that continued to influence

Kazakh politics into the twenty-first century.

KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZAKHS

729

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

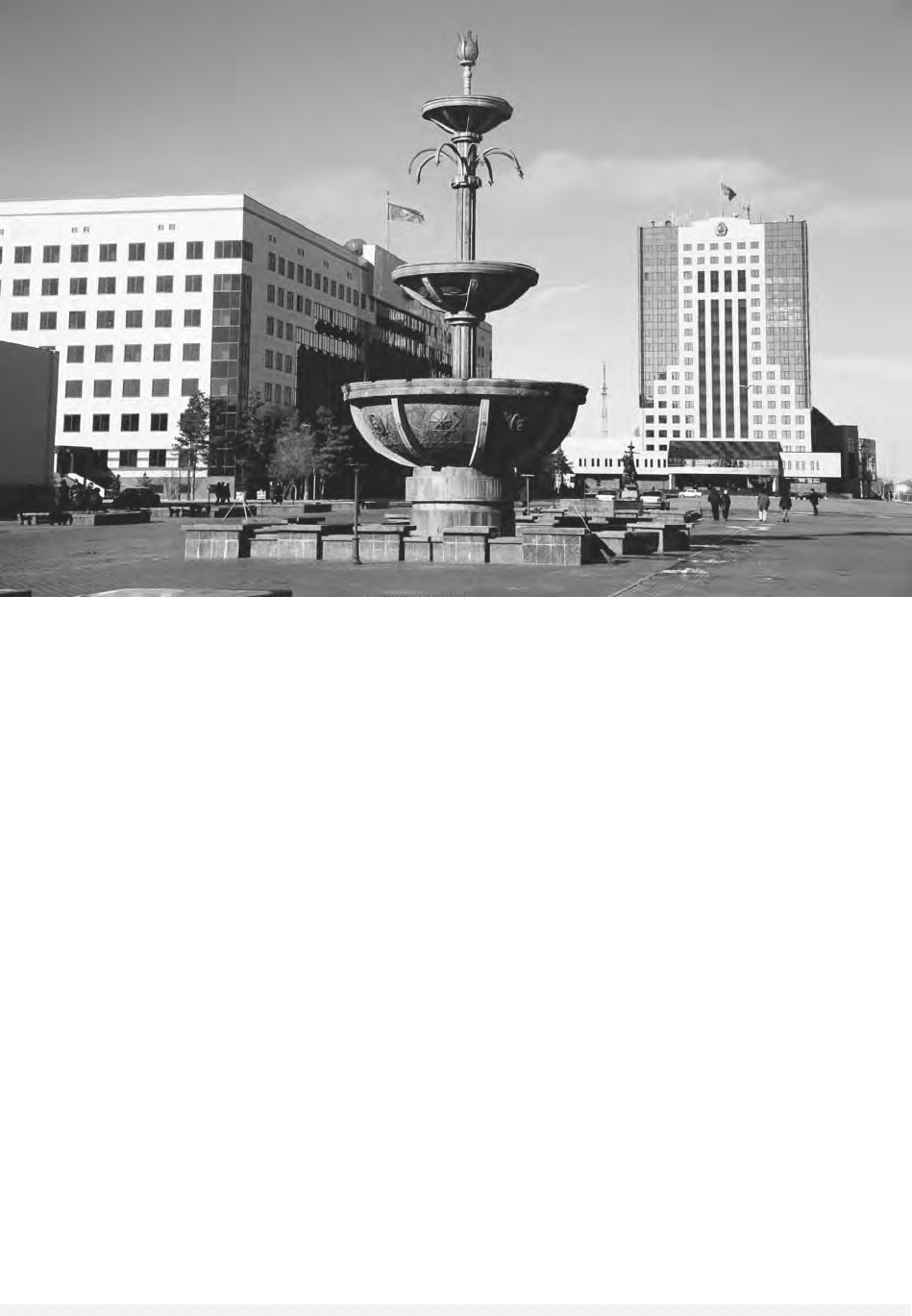

Public square in Astana, the new post-Soviet capital of Kazakhstan. © L

IBA

T

AYLOR

/CORBIS

By the mid-1600s the Kazakhs were again un-

der pressure, this time from the Jungarian (Dzhun-

garian) Oriots or Kalmyks who attacked westward

from Mongolia. Divided as they were, the Kazakhs

at first had difficulty in opposing the invaders, and

the conflict dragged on into the 1700s. Although

the Kazakhs then did unite briefly to win some ma-

jor victories, the menace only lifted after the

Manchus decisively vanquished the Oriot-Kalmyks

in 1758. In the interim, the Kazakhs had drifted

gradually but steadily into the orbit of Imperial

Russia. Consequently, some leaders began seeking

support from the Russians in their struggles. Thus

the khans and other leaders of the Small Horde in

1731, of the Middle Horde in 1740, and of part of

the Great Horde in 1742, agreed to accept Russian

suzerainty. But matters were not that straightfor-

ward, and while Russian scholars generally regard

such treaties as evidence of the Kazakhs’ “volun-

tary union” with their empire, subsequent Kazakh

historians disagree. They argue that this was a

mere tactic in a larger game of playing Russia off

against Manchu China, maintain that the khans

lacked the requisite authority to make such con-

cessions, and as evidence point to the frequent cases

of resistance to and uprisings against the Russian

colonizers. A textbook appearing in the new Re-

public of Kazakhstan charges that the tsarist au-

thorities even encouraged the Oriot-Kalmyk attacks

as a means of driving the Kazakhs into Russian

arms. So, as elsewhere, history has become a ma-

jor weapon in modern Kazakhstan’s bitter ethnic

and nationalist debates.

From 1730 to 1840 St. Petersburg’s rule was

exercised through the governor-general of Oren-

burg. As Russian expansion southward became

progressively more organized and effective, the au-

thorities were able to abolish the traditional Kazakh

KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZAKHS

730

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

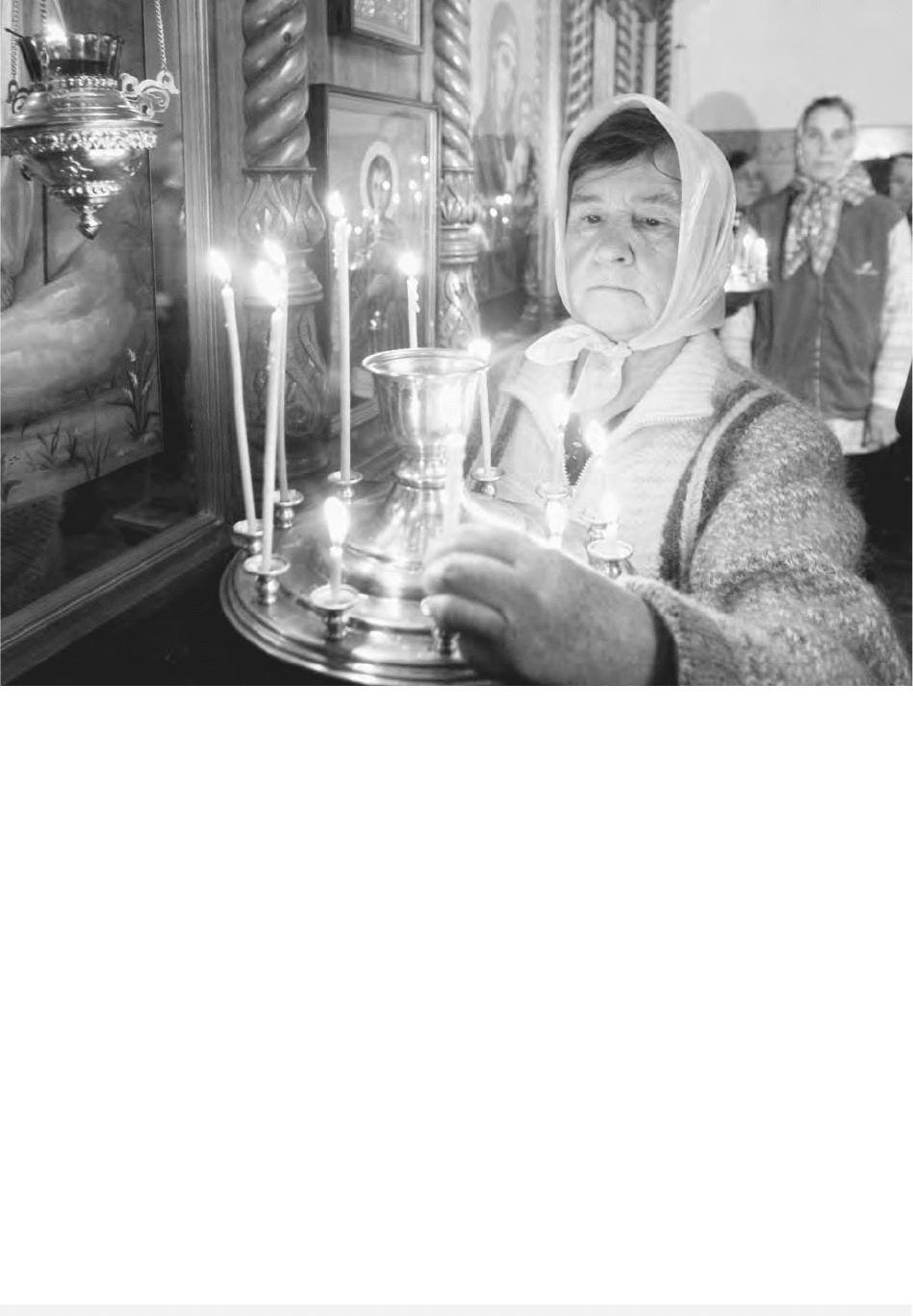

A woman lights candles during a Russian Orthodox ceremony in northern Kazakhstan, a region heavily populated by ethnic

Russians. © AFP/CORBIS

forms of leadership. They deposed the khan of the

Middle Horde in 1822, that of the Small Horde in

1824, and that of the Large Horde in 1848. Mean-

while, they also created the new Bukei (Bukej) or

Inner Horde in 1812. Then Bukei, younger son of

the Small Horde’s Khan Nurali, received permission

to move some 1,600 tents into lands between the

Urals and Volga, which had been abandoned by the

western Oriot-Kalmyks, who had fled to China.

These Kazakhs eventually settled in the Province of

Astrakhan and by the mid-1800s had some

150,000 tents. At this time the Large Horde mean-

while had some 100,000 tents, the Small Horde

800,000, and the Middle Horde 406,000 tents.

In the mid-1800s St. Petersburg organized the

governor-generalships of the Steppe and of Turke-

stan to manage the Kazakhs and Central Asians to

the south. During the late 1800s a growing wave

of Russian and other Slavic (largely Ukrainian)

peasant immigrants flowed into the region’s north-

ern sections and began settling on Kazakh lands.

The resulting discontent of the Kazakhs and other

Central Asians boiled over in the great revolt of

1916 and reemerged again during the civil strife

between 1917 and 1920.

During that conflict the intellectuals of the Alash

Orda sought to establish a Western-style Kazakh

state. Many eventually supported the Communists

in the creation of the Kirghiz (Kazakh) Autonomous

Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) as part of Soviet

Russia in 1920. Reorganized as the Kazakh ASSR in

1925, it became a constituent republic under Josef

KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZAKHS

731

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Ustyurt

Plateau

Kazak Uplands

Mt. Tengri

22,949 ft.

6995 m.

Torghay

Plateau

C

a

s

p

i

a

n

D

e

p

r

e

s

s

i

o

n

Betpak Dala

M

u

y

u

n

K

u

m

T

u

r

a

L

o

w

l

a

n

d

R

y

n

P

e

s

k

i

K

Y

R

G

Y

Z

S

K

I

Y

K

H

R

E

B

E

T

A

L

T

A

I

M

T

S

.

Aral

Sea

Ozero

Tengiz

Ozero

Zaysan

Ozero

Alakol'

Balqash Köl

Z

h

a

y

y

a

V

o

l

g

a

T

o

b

o

l

I

s

h

i

m

S

y

r

D

a

r

'

y

a

I

r

t

y

s

h

I

l

i

S

h

u

T

a

l

a

s

Caspian

Sea

¯

Almaty

(Alma-Ata)

Shymkent

(Chimkent)

Qaraghandy

(Karaganda)

Omsk

Oskemen

Semey

Pavlodar

Zhambyl

Oral

(Ural'sk)

Aqtöbe

Orenburg

Orsk

Qostanay

Qyzylorda

Novokazalinsk

Aral'sk

Zhezqazghan

(Dzhezkazgan)

Karsakpay

Taldyqorghan

Zaysan

Astana

Rubtsovsk

Köshetau

Ekibastuz

Atyrau (Guryev)

Furmanovo

Aksay

Alga

Chelkar

Leninsk

(Tyuratam)

Saryshagan

Ayaguz

Burylbaytal

Kul'sary

Emba

Khromtau

Novyy Uzen'

Ft. Shevchenko

Rudnyy

Petropavl

(Petropavlovsky)

¯

CHINA

RUSSIA

TURKMENISTAN

UZBEKISTAN

IRAN

AFGHANISTAN

TAJIKISTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

PAKISTAN

W

S

N

E

Kazakstan

KAZAKHSTAN

500 Miles

0

0

500 Kilometers

250 375125

250125 375

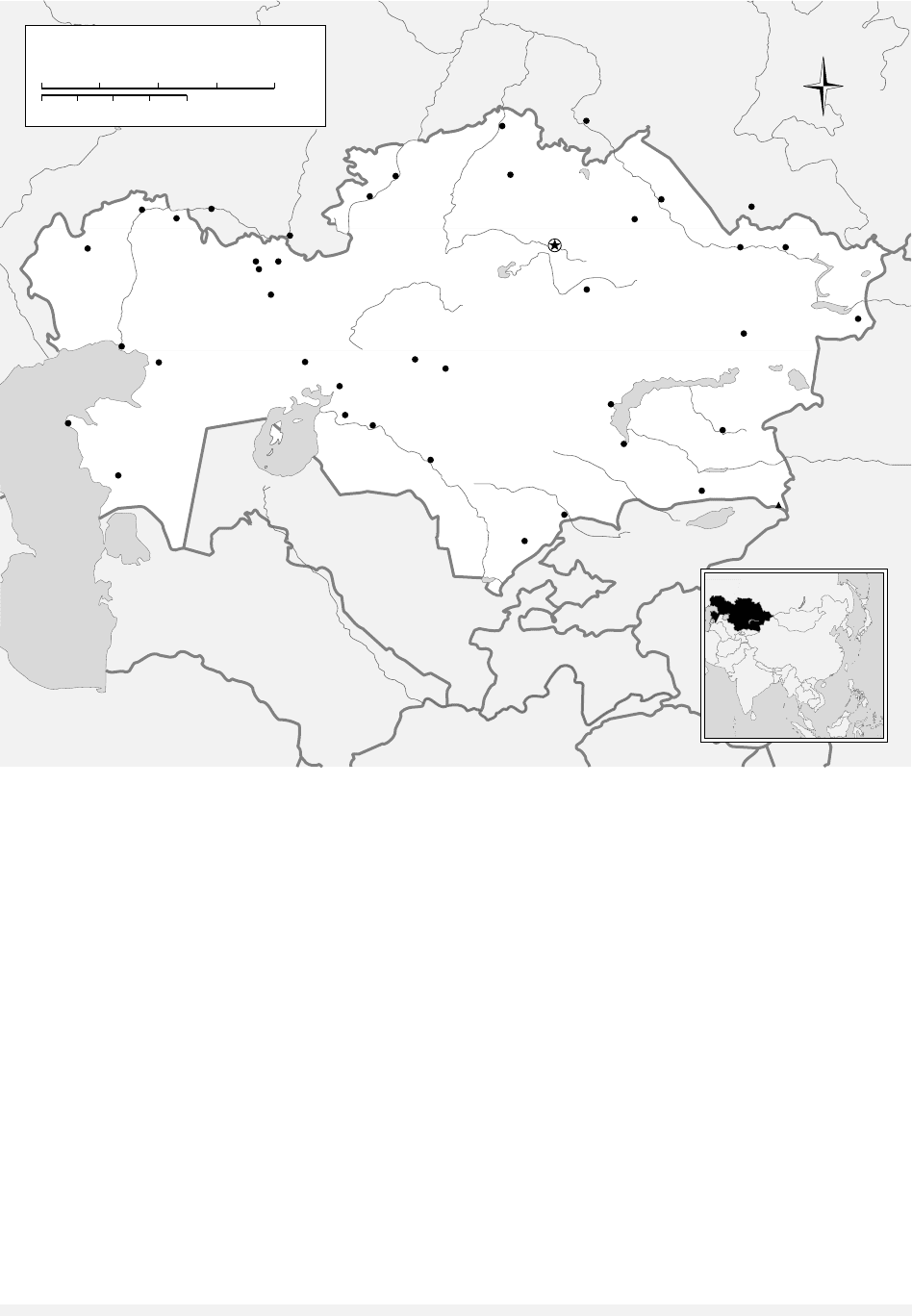

Kazakhstan, 1992 © M

ARYLAND

C

ARTOGRAPHICS

. R

EPRINTED WITH PERMISSION

Stalin in 1936 and remained so until December

1991. But despite its “democratic” constitution,

during the 1930s Kazakhstan underwent the hor-

rors of collectivization, of the forced settlement of

the nomadic stockbreeders, of the resulting famine

and epidemics, and of deportations and executions.

Meanwhile, the purges decimated the Kazakh in-

telligentsia and political leadership. The result was

a reported 2.2 million Kazakh deaths (a 49% loss),

so that there were fewer Kazakhs in the USSR in

1939 than in 1926. Equally disturbing, by the

decade’s end the republic was being flooded by de-

portees from elsewhere, converted into a basic ele-

ment of Stalin’s Gulag Archipelago, and from 1949

into a testing ground for nuclear weapons as well.

Although a new Soviet Kazakh educated elite

slowly emerged after 1938, their position in their

own nominal state was threatened further by the

new influx of hundreds of thousands of Russian,

Ukrainian, and German immigrants during Nikita

Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands agricultural program in

the 1950s. The mixed results of this effort, the

problems raised by nuclear testing on the repub-

lic’s territory, and the fact that by 1979 the Kaza-

khs reportedly were outnumbered by Russians

(41% to 36%), further fueled their ethnic resent-

ments. These exploded in riots that gripped the

capital of Alma-Ata in December 1986 when Din-

mukhammed Kunayev, the ethnic Kazakh long-

time head of the republican Communist Party, was

replaced by a Russian in December 1986. But in

April 1990 Nursultan Nazarbayev, another ethnic

Kazakh, assumed the post of Party chief. With the

collapse of the USSR in 1991, he charted the course

that established the Republic of Kazakhstan and

brought it into the new CIS. Emerging as virtual

president-for-life from the votes of 1995 and 1999,

and backed by his own and his wife’s families and

elements of his Large Horde clan, he has preserved

the unity of his ethnically, religiously, and cultur-

ally diverse state, which awaits the development of

the Caspian oil reserves as a means of alleviating

the crushing poverty that afflicts many of its cit-

izens, Kazakhs and others alike.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; ISLAM; KUNAYEV, DIN-

MUKHAMMED AKHMEDOVICH; NATIONALITIES POLI-

CIES, SOVIET; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, TSARIST;

NAZARBAYEV, NURSULTAN ABISHEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akiner, Shirin. (1986). Islamic Peoples of the Soviet Union,

2nd ed. London: KPI.

Bremmer, Ian, and Taras, Ray, eds. (1993). Nations and

Politics in the Soviet Successor States. Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press.

Grousset, Rene. (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A His-

tory of Central Asia. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers

University.

Hildinger, Erik. (1997). Warriors of the Steppe: A Military

History of Central Asia, 500 BC–1700 AD. New York:

Sarpedon.

Krader, Lawrence. (1963). Peoples of Central Asia. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

Olcott, Martha Brill. (1995). The Kazakhs, 2nd ed. Stan-

ford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Olcott, Martha Brill. (2002). Kazakhstan: Unfulfilled

Promise. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace.

Wixman, Ronald. (1984). The Peoples of the USSR: An

Ethnographic Handbook. London: Macmillan.

D

AVID

R. J

ONES

KAZAN

Kazan is the capital and major historic, cultural,

and economic center of the autonomous republic

of Tatarstan, Russia. It is located on the left bank

of the Volga River where the Kazanka River joins

it, eighty-five kilometers north of the Kama tribu-

tary. In 2002 it had an estimated population of

1,105,300.

The traditional understanding is that the name

comes from the Turkic and Volga Tatar word

qazan, meaning “kettle.” A rival theory has been

proposed that it derives from the Chuvash xusan/

xosan, meaning “bend” or “hook,” referring to the

bend of the Volga near which Kazan is located. The

Bulgars founded Iski Kazan in the thirteenth cen-

tury as one of the successors to their state, which

had been destroyed by the Mongols. At that time,

it was located forty-five kilometers up the Kazanka.

Around the year 1400, it was moved to its present

location. Ulu Muhammed, who had been ousted

from the Qipchaq Khanate in 1437, defeated the

last ruler of the principality of Kazan to establish

a khanate by 1445. It was an important trading

center, with an annual fair being held nearby.

During the first half of the sixteenth century,

the khanate of Kazan was involved in a three-

cornered struggle with Muscovy and the Crimean

khanate for influence in the western steppe area.

Ivan IV conquered the city in 1552, ending the

KAZAN

732

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY