Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Rehabilitation

Executive Order 12866 became the basis for the estab-

lishment of two online databases maintained by OMB for

purposes of regulatory review and communication with the

public. OIRA has a Regulation Tracking System, or REGS,

to monitor the regulatory review process. When a proposed

regulation is submitted to OIRA, the REGS system verifies

the information contained in the document and assigns each

submission a unique OMB tracking number. It then prints

out a worksheet for review. After the worksheet has been

reviewed, its contents are entered into the REGS system

and maintained in its database. REGS also provides a listing,

updated daily, of all pending and recently approved regula-

tions on the OMB home page. The OIRA Docket Library

maintains certain records related to proposed Federal regula-

tory actions reviewed by OIRA under Executive Order

12866. Telephone logs and materials from public meetings

attended by the OIRA Administrator are also available in the

Docket Library. A major upgrading of OIRAs information

system is scheduled for the second half of 2002.

Though administrations and policy priorities change,

the regulatory review process will most likely remain central-

ized in the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. This

office allows the president to ensure that agencies implement

legislation through regulations that reflect the central priori-

ties of the administration. For example, Executive Order

13211, signed by President George W. Bush on May 22,

2001, requires federal agencies to submit a formal Statement

of Energy Effects to OIRA along with their submissions of

proposed regulations. The Statement of Energy Effects must

include a description of any negative effects on the supply,

distribution, or use of energy that are likely to result from a

proposed regulation. These negative effects could include

lowered production of

coal

, oil, gas, or electricity; increased

costs; or harm to the environment. The order does not, how-

ever, change the basic process of regulatory review.

One structural modification that may be made within

the next few years, however, is related to the computerization

of government information. As of 2002, the federal govern-

ment does not have a “seamless” system of data collection,

analysis, and use. For the past several decades, government

agencies have purchased computers and software systems on

their own, without any attempt to coordinate their systems

with those of other agencies. The lack of a unified computer

language complicates the process of regulatory review as well

as contributing to overall inefficiency and higher costs. In

the summer of 2002, the Senate passed a bill called the E-

Government Act, intended to help government agencies

communicate more effectively with one another as well as

make government information more accessible to citizens.

The E-Government Act would allocate $345 million over

a four-year period to help federal agencies upgrade their

online services, and to establish an Office of Electronic Gov-

1187

ernment alongside OIRA under the Office of Management

and Budget.

[Alair MacLean and Rebecca J. Frey, Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Coleman, B. Through the Corridors of Power: A Citizen’s Guide to Federal

Rulemaking. Washington, DC: OMB Watch, 1987.

P

ERIODICALS

Raney, Rebecca Fairley. “Changing Federal Buying Habits.” New York

Times, July 8, 2002.

O

THER

Dudley, Susan, and Melinda Warren. Regulatory Response: An Analysis of

the Shifting Priorities of the U.S. Budget for Fiscal Years 2002 and 2003.

Regulatory Report 24, Weidenbaum Center, Washington University, St.

Louis, MO.

Federal Register, volume 58, Presidential Documents. Executive Order

12866 of September 30, 1993— Regulatory Planning and Review. Washing-

ton, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1993.

Federal Register, volume 66, Presidential Documents. Executive Order

13211 of May 22, 2001— Actions Concerning Regulations That Significantly

Affect Energy Supply, Distribution, or Use. Washington, DC: U.S. Govern-

ment Printing Office, 2001.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), The Office of

Management and Budget, 725 17th Street, NW, Washington, DC USA

20503 (202) 395-4852, Fax: (202) 395-3888, <http://www.whitehouse.gov/

omb/inforeg>

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is a process which is being applied more fre-

quently to the

environment

. It aims to reverse the deteriora-

tion of a national resource, even if it cannot be restored to

its original state.

Attempts to rehabilitate deteriorated areas have a long

history. In England, for example, gardener and architect

Lancelot “Capability” Brown devoted his life to restoring

vast stretches of the English countryside that had been dra-

matically modified by human activities.

Reforestation was one of the common forms of reha-

bilitation used by Brown, and this method continues to be

used throughout the world. The demand for wood both as

a building material and a source of fuel has resulted in the

devastation of forests on every continent. Sometimes the

objective of reforestation is to ensure a new supply of lumber

for human needs, and in other cases the motivation is to

protect the environment by reducing land

erosion

. Aesthetic

concerns have also been the basis for reforestation programs.

Recently, the role of trees in managing atmospheric

carbon

dioxide

and global climate has created yet another motiva-

tion for the planting of trees.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

William Kane Reilly

Another activity in which rehabilitation has become

important is

surface mining

. The process by which

coal

and other minerals are mined using this method results in

massive disruption of the environment. For decades, the

policy of mining companies was to abandon damaged land

after all minerals had been removed. Increasing environmen-

tal awareness in the 1960s and 1970s led to a change in that

policy, however. In 1977, the United States Congress passed

the

Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act

(SMCRA), requiring companies to rehabilitate land dam-

aged by these activities. The act worked well at first and

mining companies began to take a more serious view of their

responsibilities for restoring the land they had damaged, but

by the mid-1980s that trend had been reversed to some

extent. The Reagan and Bush administrations were both

committed to reducing the regulatory pressure on American

businesses, and tended to be less aggressive about the en-

forcement of environmental laws such as SMCRA.

Rehabilitation is also widely used in the area of human

resources. For example, the spread of urban blight in Ameri-

can cities has led to an interest in the rehabilitation of public

and private buildings. After World War II, many people

moved out of central cities into the suburbs. Untold numbers

of houses were abandoned and fell into disrepair. In the

last decade, municipal, state, and federal governments have

shown an interest in rehabilitating such dwellings and the

areas where they are located. Many cities now have urban

homesteading laws under which buildings in depressed areas

are sold at low prices, and often with tax breaks, to buyers

who agree to rehabilitate and live in them. See also Environ-

mental degradation; Environmental engineering; Forest

management; Greenhouse effect; Strip mining; Restoration

ecology; Wildlife rehabilitation

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Moran, J. M., M. D. Morgan, and J. H. Wiersma. Introduction to Environ-

mental Science. 2nd ed. New York: W. H. Freeman, 1986.

Newton, D. E. Land Use, A–Z. Hillside, NJ: Enslow Publishers, 1989.

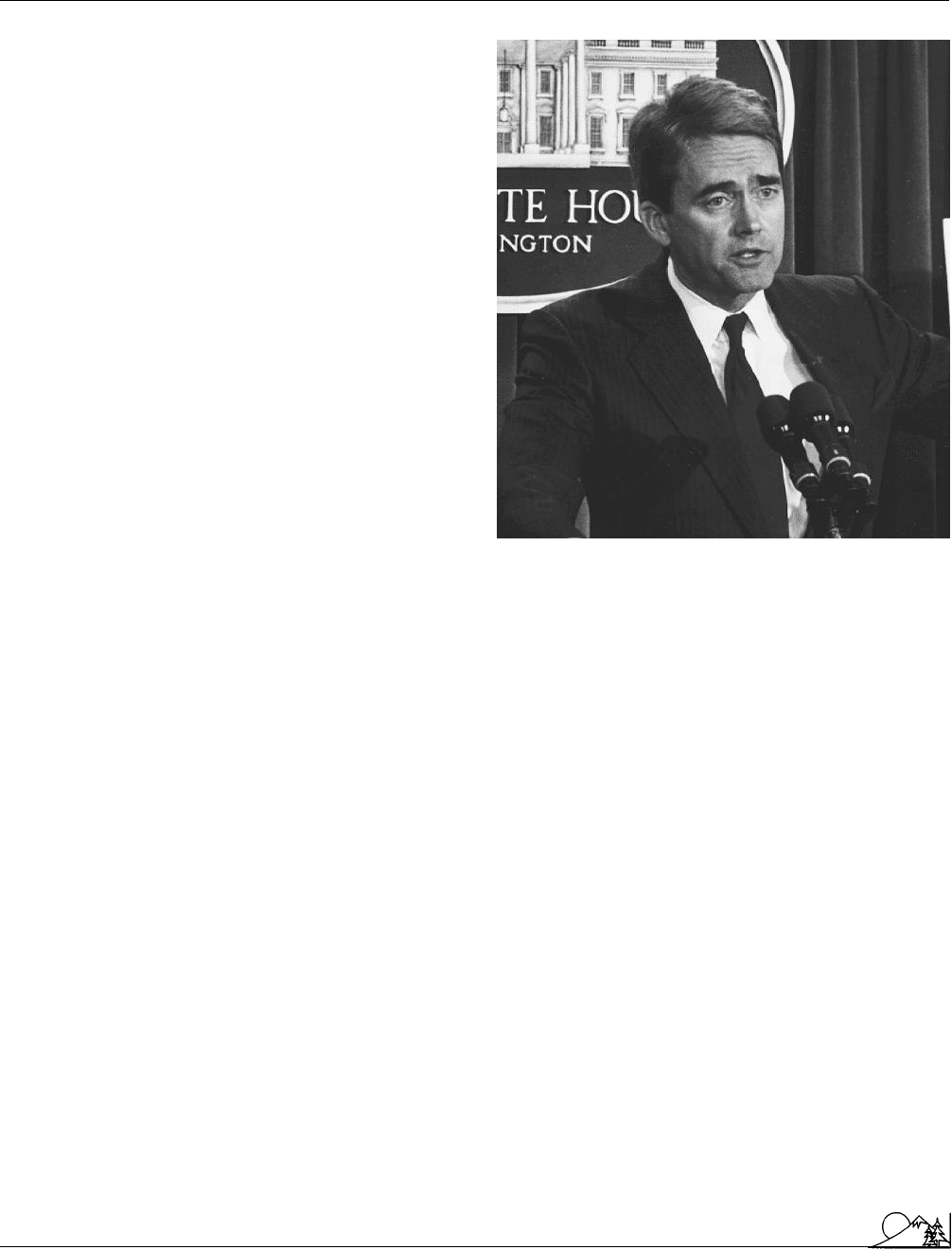

William Kane Reilly (1940 – )

American conservationist and Environmental Protection

Agency administrator

Called the “first professional environmentalist” to head the

Environmental Protection Agency

since its founding in

1970, Reilly came to the agency in 1989 with a background in

law and urban planning. He had been appointed to President

Richard Nixon’s

Council on Environmental Quality

in

1188

William K. Reilly describing the Bush adminis-

tration’s clean air proposals in 1989. (Corbis-

Bettmann. Reproduced by permission.)

1970, and was named executive director of the Task Force

on

Land Use

and Urban Growth two years later. In 1973,

Reilly became president of the Conservation Foundation, a

non-profit environmental research group based in Washing-

ton, D.C., which he is credited with transforming into a

considerable force for environmental protection around the

world. In 1985, the Conservation Foundation merged with

the

World Wildlife Fund

; Reilly was named as president,

and under his direction, membership grew to 600,000 with

an annual budget of $35 million.

Reilly began to cautiously criticize White House

envi-

ronmental policy

during Ronald Reagan’s administration,

objecting to the appointments of

James G. Watt

, and his

successor William P. Clark, as secretary of the interior. He

published articles and spoke publicly about

pollution

,

spe-

cies

diversification,

rain forest

destruction, and

wet-

lands

loss.

After his confirmation as EPA administrator, Reilly

laid out an agenda that was clearly different from his prede-

cessor, Lee Thomas. Reilly promised “vigorous and aggres-

sive enforcement of the environmental laws,” a tough new

Clean Air Act

, and an international agreement to reduce

chlorofluorocarbons

(CFCs) in the

atmosphere

. Calling

toxic waste cleanup a top priority, Reilly also promised action

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Religion and the environment

to decrease urban

smog

, remove dangerous

chemicals

from

the market more quickly, encourage strict fuel efficiency

standards, increase

recycling

efforts, protect wetlands, and

encourage international cooperation on global warming and

ozone layer depletion

.

In March 1989, Reilly overruled a recommendation

of a regional EPA director and suspended plans to build the

Two Forks Dam on the South Platte River in Colorado.

The decision relieved environmentalists who had feared con-

struction of the dam would foul a prime trout stream, flood

a scenic canyon, and disrupt

wildlife migration

patterns.

That same year, Reilly criticized the federal government’s

response to the grounding of the

Exxon Valdez

and the

oil spill in

Prince William Sound

, Alaska.

At Reilly’s urging, President George Bush proposed

major revisions of the Clean Air Act of 1970. The new act

required public utilities to reduce emissions of

sulfur diox-

ide

by nearly half. It also contained measures that reduced

emissions of toxic chemicals by industry and lowered the

levels of urban smog.

Under Reilly’s direction, the EPA also enacted a grad-

ual ban on the production and importation of most products

made of

asbestos

. He left the agency in 1992, and in

1993 became President and Chief Executive Officer of Aqua

International Partners, L. P.

[Linda Rehkopf]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Williams, T. “It’s Lonely Being Green: In an Environmentally Unfriendly

Administration, William K. Reilly and John Turner Have Stood Alone as

Conservationists.” Audubon 94 (September–October 1993): 52–6.

Relict species

A

species

surviving from an ancient time in isolated popula-

tions that represent the localized remains of a distribution

which was originally much wider. These populations become

isolated through disruptive geophysical events such as

glaci-

ation

, or immigration to outlying islands, which is not fol-

lowed by reunification of the fragmented populations. The

origins and relationships of several relict species are well

documented, and these include local Central American avian

populations which are remnants of the North American

avifauna left after the last glacial retreat. The origins of other

relict species are unknown because all related species are

extinct. This group includes lungfishes, rhynchocephalian

reptiles (genus Sphenodon), and the duck-billed platypus (Or-

1189

nithorhynchus anatinus). See also California condor; Endan-

gered species; Extinction; Rare Species

Religion and the environment

All of the world’s major faiths have, as integral parts of their

laws and traditions, teachings requiring protection of the

environment

, respect for

nature

and

wildlife

, and kindness

to animals. While such tenets are well-known in such East-

ern religions as Buddhism and Hinduism, there is also a

largely-forgotten but strong tradition of such teachings in

Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. All of these faiths recog-

nize a doctrine of their deity’s love for creation and for all

of the living creatures of the world. The obligation of humans

to respect and protect the natural environment and other

life forms appears throughout the sacred writings of the

prophets and leaders of the world’s great religions.

These tenets of “environmental theology” contained

in the world’s religions are infrequently observed or prac-

ticed, but many theologians feel that they are more relevant

today than ever. At a time when the earth faces a potentially

fatal ecological crisis, these leaders say, traditional religion

shows us a way to preserve our planet and the interdependent

life forms living on it. Efforts are under way by representa-

tives of virtually all the major faiths to make people more

aware of the strong

conservation

and humane teachings

that are an integral part of the religions of most cultures

around the globe. This movement holds tremendous poten-

tial to stimulate a spiritually-based ecological ethic through-

out the world to improve and protect the natural environ-

ment and the welfare of humans who rely upon it.

The Bible’s ecological message

The early founders and followers of monotheism were

filled with a sense of wonder, delight, and awe of the great-

ness of God’s creation. Indeed, nature and wildlife were

sources of inspiration for many of the prophets of the Bible.

The Bible contains a strong message of conservation, respect

for nature, and kindness to animals. It promotes a reverence

for life, for “God’s Creation,” over which humans were given

stewardship responsibilities to care for and protect. The

Bible clearly teaches that in despoiling nature, the Lord’s

handiwork is being destroyed and the sacred trust as caretak-

ers of the land over which humans were given stewardship

is violated.

Modern-day policies and programs that despoil the

land, desecrate the environment, and destroy entire

species

of wildlife are not justified by the Bible. Such actions clearly

violate biblical commands to humans to “replenish the earth,”

conserve

natural resources

, and treat animals with kind-

ness, and to animals to “be fruitful and multiply” and fill

the earth. For example, various laws requiring the protection

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Religion and the environment

of natural resources are found in the Mosaic law, including

passages mandating the preservation of fruit trees (Deuter-

onomy 20:19, Genesis 19:23–25); agricultural lands (Leviti-

cus 25:2–4); and wildlife (Deuteronomy 22:6–7; Genesis 9).

Numerous other biblical passages extol the wonders of nature

(Psalms 19, 24, and 104) and teach kindness to animals,

including the Ten Commandments, which require that farm

animals be allowed to rest on the Sabbath.

Christianity: Jesus’ nature teachings

The New Testament contains many references by Jesus

and his disciples that teach people to protect nature and its

life forms. Throughout the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus

used nature and pastoral imagery to illustrate his points and

uphold the creatures of nature as worthy of being emulated.

In stressing the lack of importance of material possessions

such as fancy clothes, Jesus observed that “God so clothes

the grass of the field” and cited wildflowers as possessing

more beauty than any human garments ever could: “Consider

the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither

do they spin. And yet I say unto you, that even Solomon

in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these” (Matthew

6:28–30; Luke 12:27). In Luke 12:6 and Matthew 10:29,

Jesus stresses that even the lowliest of creatures is loved by

God: “Are not five sparrows sold for two pennies? And not

one of them is forgotten before God.”

Judaism: a tradition of reverence for nature

The teachings and laws of Judaism, going back thou-

sands of years, strongly emphasize kindness to animals and

respect for nature. Indeed, an entire code of laws relates to

preventing “the suffering of living creatures.” Also important

are the concepts of protecting the elements of nature, and

tikkun olam, or “repairing the world.” Jewish prayers, tradi-

tions, and literature contain countless stories and admoni-

tions stressing the importance of the natural world and ani-

mals as manifestations of God’s greatness and love for His

creation.

Many examples of practices based on Judaism’s respect

for nature can be cited. Early Jewish law prevented

pollution

of waterways by mandating that sewage be buried in the

ground, not dumped into rivers. In ancient Jerusalem, dung

heaps and

garbage

piles were banned, and refuse could not

be disposed of near water systems. The Israelites wisely

protected their drinking water supply and avoided creating

hazardous and unhealthy waste dumps. The rabbis of old

Jerusalem also dealt with the problem of

air pollution

from

wheat chaff by requiring that threshing houses for grain be

built no closer than 2 miles (3.2 km) from the city. In order

to prevent foul odors, a similar ordinance existed for graves,

carrion, and tanneries, with tanneries sometimes required

to be constructed on the edge of the city downwind from

prevailing air currents. Wood from certain types of rare trees

could not be burned at all, and the Talmud cautioned that

1190

lamps should be set to burn slowly so as not to use up too

much naphtha. The biblical injunction to allow land to lie

fallow every seven years (Lev. 25:3–7) permitted the

soil

to

replenish itself.

Islam and ecology

In the Qur’an (Koran), the holy book of the Islamic

faith, scholars have estimated that as many as 750 out of

the book’s 6,000 verses (about one-eighth of the entire text)

have to do with nature. In Islamic doctrine there are three

central principles that relate to an environmental ethic, in-

cluding tawhid (unity), khilafa (trusteeship), and akhirah

(accountability). Nature is considered sacred because it is

God’s work, and a unity and interconnectedness of living

things is implied in certain scriptures, such as: “There is no

God but He, the Creator of all things” (Q.6: 102). The

balance of the natural world is also described in some verses:

“And the earth we have spread out like a carpet; set thereon

mountains firm and immobile; and produced therein all

kinds of things in due balance” (Q.15:1 9). On the earth,

humans are given the role of stewards (called “vicegerents"),

when the Qur’anic scripture states, “Behold, the Lord said

to the angels: ’I will create a vicegerent on earth...’” (Q.2:

30). In the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, humans

are told to cultivate and care for the earth. ("Whoever brings

dead land to life, that is, cultivates wasteland, for him is a

reward therein"), and humans are cautioned in the Qur’an

against abusing the creation: “Do no mischief on the earth

after it hath been set in order, but call on Him with fear

and longing in your hearts: for the Mercy of God is always

near to those who do good” (Q.7: 56). Interestingly, the

Qur’an also contains scriptures that caution humankind

about the use of metals, perhaps foreshadowing the machine

age of the future: “We bestowed on you from on high the

ability to make use of iron, in which there is awesome power

as well as a source of benefits for man” (Q.57.25).

Other faiths

The religions of the East have also recognized and

stressed the importance of protecting natural resources and

living creatures. Buddhism and Hinduism have doctrines of

non-violence to living beings and have teachings that stress

the unity and sacredness of all of life. Some Hindu gods

and goddesses are embodiments of the natural processes of

the world. Taoists, who practice a philosophy and worldview

that originated in ancient China, strive not to attempt to

dominate but to live in harmony with the tao, or the natural

way of the universe. Many other religions, including the

Baha’is and those of Native Americans, Amazon Indian

tribes, and other indigenous and tribal peoples, stress the

sanctity of nature and the need to conserve wildlife, forests,

plants, water, fertile land, and other natural resources.

[Lewis G. Regenstein and Douglas Dupler]

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Remediation

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Barnhill, David L., and Roger S. Gottlieb. Deep Ecology and World Religions.

Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001.

Berry, T. The Dream of the Earth. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1988.

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, 1962.

Cobb, J. Is It Too Late? A Theology of Ecology. Environmental Ethics

Books, 1995.

Fox, M. W. The Boundless Circle: Caring for Creatures and Creation.

Wheaton, IL: Quest Books, 1996.

Gore, Al. Earth in the Balance: Ecology and the Human Spirit. New York:

Houghton Mifflin, 1992.

Hoyt J. Animals in Peril. Garden City-Park, NY: Avery, 1994.

Leopold, A. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1949.

Regenstein, L. G. Replenish the Earth: The Teachings of the World’s Religions

on Protecting Animals and Nature. New York: Crossroads, 1991.

Wilson, E. O. Biophilia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Harvard Center for the Study of World Religions: Religions of the World

and Ecology, 42 Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA USA 02138 (617) 495-

4495, Fax: (617) 496-5411, Email: cswrinfo@hds.harvard.edu, <http://

www.hds.harvard.edu/cswr/ecology/index.htm>

Remediation

The treatment of hazardous wastes in most industrialized

countries is now controlled through regulations, policies,

incentive programs, and voluntary efforts. However, until the

1980s, society knew little of the harmful effects of inadequate

management of hazardous wastes, which resulted in many

contaminated sites and polluted

natural resources

. Even

in the 1970s, when environmental legislation required dis-

posal of hazardous wastes to landfills and other systems,

contamination of soils and

groundwater

continued, be-

cause these systems were often not leak proof. To meet the

environmental and public health standards of the twenty-

first century, these contaminated sites must continue to be

rehabilitated, or remediated, so they no longer pose a threat

to the public or the

ecosystem

. However, the price will be

high; total costs for cleaning up the U.S. Department of

Energy’s (DOE)

nuclear weapons

sites alone will cost

$147 billion from 1997 to 2070. Cleaning America’s con-

taminated groundwater will cost even more: $750 billion

over the next 30 years.

The Superfund program for remediation of contami-

nated sites was created in 1980 by the

Comprehensive

Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability

Act

(CERCLA) and was amended by the Superfund

Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA) of 1984.

The Superfund program is designed to provide an immediate

response to emergency situations that pose an imminent

hazard, known as removal or emergency response-actions, and

1191

to provide permanent remedies for environmental problems

resulting from past practices (i.e., abandoned or inactive

waste sites), know as remedial-response actions. Under the

Superfund program, the remedial action process is imple-

mented in structured stages: (1) Preliminary assessment; (2)

Site inspection; (3) Listing on the

National Priorities List

(NPL), a rank ordering of sites representing the greatest

threats; (4) Remedial investigation/ feasibility study (RI/

FS); (5) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s

Record

of Decision

(ROD); (6) Negotiation of a consent decree

and remedial action plan between the U.S.

Environmental

Protection Agency

and the responsible parties; and (7) Final

design and construction.

Money for the Superfund came from special taxes on

chemical and

petroleum

companies, which expired in 1995

and were not renewed. These taxes contributed about $1.3

billion a year prior to 1996. Since 1995, the fund has dwin-

dled from a high of $3.6 billion to a projected $28 million

in 2003. Currently, debate continues on where additional

funds will come from, which may eventually be the taxpayer

if special taxes are not reestablished. The Bush administra-

tion had proposed that the Superfund pay $593 million

of 2002’s projected $1.3 billion in cleanup costs, with the

remaining $700 million coming from the Treasury. After

this, the Superfund will be depleted. Money will have to

come from somewhere because according to

Resources for

the Future

, Superfund programs will cost $14–$16.4 billion

between 2000 and 2009, with annual costs of between $1.3

billion and $1.7 billion.

In addition to the Superfund program, site remedia-

tion projects may be required for: the

Resource Conserva-

tion and Recovery Act

(RCRA) Corrective Action Program

for operating treatment, storage, and disposal facilities; the

underground storage tanks program established by RCRA;

Federal Facility cleanup of sites operated primarily by DOE

and the Department of Defense (regulated under both CER-

CLA and RCRA); and state-regulated, private, and volun-

tary programs. The cleanup of federal facilities is expected

to be the most expensive, followed by the RCRA Corrective

Action Program, and then Superfund. DOE must character-

ize, treat, and dispose of hazardous and

radioactive waste

at more than 120 sites in 36 states and territories, which is

expected to cost more than $60 billion over the next 10 years.

The costs of remediation are determined by the degree

of remediation required. Superfund cleanup standards re-

quire that contaminated waters be remediated to concentra-

tions at least as clean at the Maximum Contaminant Levels

(MCLs) of the

Safe Drinking Water Act

and the

water

quality

criteria of the

Clean Water Act

.

Carcinogen

risks

from exposures to a Superfund site should be less than one

excess

cancer

in a population of one million people. Some

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Remediation

states require that remediation projects restore the site to

an equivalent of its original condition.

Remedial techniques are divided into two basic types:

on-site methods and removal methods. Most remedial tech-

niques are used in combination (e.g., pump and treat sys-

tems) rather than singly. Generally remediation techniques

that significantly reduce the volume, toxicity, or mobility of

hazardous wastes are preferred for use. Off-site transport

and disposal is usually the least favored option. On-site

methods include containment, extraction, treatment, and

destruction, while removal methods consist of excavation

and

dredging

. Containment is used to contain liquid wastes

or contaminated ground waters within a site; or to divert

ground or surface waters away from the site. Containment

is achieved by the construction of low-permeability or imper-

meable cutoff walls or diversions. On-site groundwater ex-

traction is accomplished by pumping, which is usually fol-

lowed by aboveground treatment (referred to as pump and

treat). Pumping is used to control water tables so as to

contain or remove contaminated groundwater plumes or to

prevent

plume

formation.

Soil

vapor extraction, by either

passive or forced ventilation collection systems, is used to

remove hazardous gases from the soil. Gases are collected

in PVC perforated pipe

wells

or trenches and transported

above ground to treatment or

combustion

units.

On-site treatment of hazardous wastes can be con-

ducted above ground, following extraction or excavation, or

below ground (in situ). Above ground treatment methods

include the use of conventional

environmental engi-

neering

unit processes. Below ground treatment can be non-

biological or biological. Non-biological in situ treatment

involves the delivery of a treatment fluid through injection

wells into the contaminated zone to achieve immobilization

and/or

detoxification

of the contaminants. This treatment

is accomplished by processes such as oxidation, reduction,

neutralization, hydrolysis, precipitation, chelation, and stabi-

lization/solidification. Biological in situ treatment (

bior-

emediation

) is accomplished by modifying site conditions

to promote microbial degradation of organic compounds by

naturally occurring

microorganisms

. Exogenous microor-

ganisms that have been adapted to degrade specific com-

pounds or classes of compounds are also sometimes pumped

into ground water or applied to

contaminated soil

. Certain

types of bacteria and plants containing

peptides

are also

being developed for treating radioactive materials and

heavy

metals

.

Finally, on-site destruction of organic hazardous

wastes can be accomplished by the use of high-temperature

incineration

. Inorganic materials are not destroyed, so resi-

dues from the incineration process must be disposed of in

a secure

landfill

. In situ vitrification (ISV), or thermal de-

struction, involves the heating of buried wastes to melting

1192

temperatures (by applying electric current to the soil) so that

a chemically inert, stable glass block is produced. Nonvolatile

materials are immobilized in the vitrified mass, and organic

materials are pyrolyzed. Combustion off-gases are collected

and treated.

Removal methods of remediation include extraction

and dredging. Excavation of contaminated solid or semisolid

hazardous wastes may be required if the wastes are not

amenable to in situ treatment. Excavated materials may be

treated and replaced or transported off-site. Dredging is used

to remove contaminated sediments from streams, estuaries,

or surface impoundments. Removal of well-consolidated

sediments in shallow waters requires the use of a clamshell,

dragline, or backhoe. Sediments with a high liquid content

or that are located in deeper waters are removed by hydraulic

dredging. Dredged materials are pumped or barged to treat-

ment facilities.

Although not every remediation project has been a

complete success, many Superfund sites have been cleaned

up significantly. Of the 1,310 sites on the list, 773 sites had

been cleaned up by 2001, with the remainder in various

stages of cleanup. However, the rate of cleanups is slowing;

about half as many will be completed during the current

administration compared to the previous one. As better pro-

cedures for remediation continue to be developed and re-

fined, perhaps this rate will increase. Nanoparticle technol-

ogy is one method that shows promise for cleaning

groundwater sites, since it can reduce 96% of contaminants

compared to 25% with conventional methods.

[Laurel M. Sheppard]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Blackman Jr., W. L. Basic Hazardous Waste Management. Boca Raton, FL:

Lewis Publishers, 1993.

Freeman, H. M., ed. Standard Handbook of Hazardous Waste Treatment

and Disposal. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989.

Henry, J. G., and G. W. Heinke. Environmental Science and Engineering.

2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1996.

Probst, Katherine N., David M. Konishky, et al.Superfund’s Future: What

Will It Cost? Resources for the Future, 2001.

P

ERIODICALS

“Administration Accused of Slowing Superfund.” Chemical Market Report,

April 15, 2002, 4.

“DOE: Nuclear Weapon Cleanup Will Cost $147B.” USAToday.com, Au-

gust 23, 2001.

Hellprin, John. “EPA Chief Defends Halving Toxic Waste Cleanups as

Superfund Money Nears Depletion.” Associated Press, March 13, 2002.

Morgan, Dan. “Hazardous Waste Site Cleanup Delayed, EPA Inspector

Reports.” Washington Post, July 2, 2002, A02.

“New Technology Revolutionizing Ground Water Clean-Up.” PR Newsw-

ire, March 13, 2002.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Renewable energy

Remote sensing

see

Measurement and sensing

Renew America

Renew America serves as a clearinghouse for information on

the

environment

. Renew America distributes reports, pam-

phlets, and books to educators, organizations, and the general

public in an attempt to fulfill its primary goal of “renewing

America’s community spirit through environmental success.”

One of Renew America’s major projects is the annual Envi-

ronmental Success Index, a compilation of over 1,400 successful

environmental programs throughout the United States. The

index lists organizations involvedin a variety of environmental

issues, including

air pollution control

, drinking water and

groundwater

protection, hazardous and solid

waste reduc-

tion

and

recycling

,

renewable energy

, and forest protec-

tionand urban forestry. The purpose ofthe index is to dissemi-

nate information on organizations that can function as

prototypes for other programs. Renew America also publishes

an annual report entitled State of the States, which serves as a

report card on environmental policies in all 50 states. State of

the States is compiled in cooperation with over 100 state and

local environmental organizations.

In addition to disseminating published information,

Renew America distributes the Renew America National

Awards each year. The awards are the result of a national

search conducted by the Renew America Advisory Council,

which is composed of 28 environmental groups. Renew

America also selects a recipient for the Robert Rodale Envi-

ronmental Achievement Award. Rodale served as chair of

Renew America and the Rodale Press and administered the

Rodale Institute

, a scientific and educational foundation

focusing on food, health, and natural resource issues. The

awards are presented at the Environmental Leadership Con-

ference, which also features several environmentally-oriented

workshops and panel discussions. Like the Environmental

Success Index, the advisory council selects recipients from a

broad range of environmental programs. Past winners have

included a group that assists area residents in creating com-

munity food gardens, surfers who won a lawsuit under the

federal

Clean Water Act

, an adopt-a-manatee program, and

an asphalt recycling project.

Renew America also offers educational tools such as a

community resource kit called Sharing Success, which features

articles on ways to approach environmental problems and

highlights special environmental groups. It was developed

to meet the needs of local environmental groups and other

interested activists who wanted to share successful ap-

proaches to environmental problems.

1193

Renew America does not utilize volunteers or engage

in grassroots projects itself but provides information on orga-

nizations that do. Members receive the State of the States

report and a quarterly newsletter highlighting significant

environmental issues. Board members include former con-

gress member Claudine Schneider and actor Eddie Albert

as well as officials from several prominent environmental

organizations.

[Kristin Palm]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Renew America, 1200 18th Street, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, D.C.

USA 20036 (202) 721-1545, Fax: (202) 467-5780, Email:

renewamerica@counterpart.org, <http://sol.crest.org/environment/

renew_america>

Renewable energy

The earth’s resources are commonly divided into renewable

and

nonrenewable resources

. Some renewable resources

are perpetual, meaning that they are not affected by human

use, such as

solar energy

or

wind energy

. Other renewable

resources are organic and inorganic materials that are replen-

ished by physical and biogeochemical cycles. Examples of

organic renewable resources are all plant and animal

species

that people use for food, building materials, drugs, leisure,

and so on. Examples of inorganic renewable resources are

water and oxygen, which are replenished in the hydrological

and oxygen cycles, respectively. The main sources of renew-

able energy in the United States are

biomass

(wood and

waste burned for fuel), hydroelectric power (energy produced

from flowing water), geothermal sources (energy from heat

sources in the earth’s surface), solar (energy from the sun),

and wind energy. Nonrenewable resources are those materi-

als that are present in the earth in limited amounts (minerals)

or are produced only over many millions of years (

fossil

fuels

). Nonrenewable resources may be recyclable so that

their usefulness to human beings can be extended, but often

they are transformed during use into useless matter such as

waste gas.

Taking advantage of renewable energy sources became

important in the United States after the OPEC (

Organiza-

tion of Petroleum Exporting Countries

)

oil embargo

dur-

ing the 1970s. Until that time,

coal

and oil easily supplied

nearly 90% of energy to the United States, but sudden short-

ages and huge price increases prompted the United States

government to invest in researching alternative and renew-

able energy sources. The 1990s were a decade of cheap and

readily available fossil fuel, and United States development

of renewable energy grew relatively slowly. In the early

twenty-first century renewable energy became important

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Renewable energy

again, with an energy crisis in California, the nation’s most

populous state, and with increasing concern over

pollution

and global warming. Political issues related to energy pro-

duction, such as growing United States dependence on Mid-

dle Eastern oil reserves and the protection of

wildlife

and

offshore areas that contain United States oil reserves, also

brought attention and hope to renewable energy.

According to figures released by the Energy Informa-

tion Administration (EIA) of the

U.S. Department of En-

ergy

(DOE), renewable energy sources accounted for about

7% of all United States energy used in 2000. Biomass con-

tributed about 48% of that renewable energy total. Biomass

includes wood used to heat homes, as well as the waste

burned in municipal waste recovery plants and converted to

electricity. Other biomass sources of energy include

ethanol

and

methanol

, which are alternative fuels made from fer-

mented plant material. Ethanol is made from corn and often

added to

gasoline

for use in internal

combustion

engines.

Methanol is an alternative fuel made from wood, and like

ethanol, is expensive to produce and thus at a disadvantage

when compared to fossil fuels and to other renewables. An-

other biomass energy source is

landfill

gas, which is

meth-

ane

that is captured and used for fuel as waste landfills

decompose.

Hydropower accounted for 46% of United States re-

newable energy in 2000, and was the world’s largest renew-

able energy source. Hydropower uses the force of dammed

water to turn turbines, which produce electricity. Future

United States development of hydropower is not projected

to increase, as the most productive sites have already been

used. Several

Third World

countries have viewed hy-

dropower as a cheap source of future energy and are devel-

oping new projects, while environmentalists have strongly

protested the damming of more rivers and the

habitat

de-

struction associated with large hydropower facilities.

Geothermal sources produced 5% of United States

renewable energy in 2000.

Geothermal energy

is produced

by converting the heat of the earth into electricity, using

steam-powered turbines, or by using the heat directly for

buildings and industrial purposes. The United States was

the world’s largest producer of geothermal power, accounting

for about 44% of the world total. Like hydropower, U.S.

geothermal power is not projected to grow in the future, as

the most advantageous sites are already taken. Other coun-

tries including the Philippines, New Zealand, and Iceland

are developing significant thermal energy resources.

Solar power accounted for 1% of United States renew-

able energy consumption in 2000, although the solar power

industry grew by 20% for five straight years in the late

1990s. Solar energy systems include passive ones, such as

greenhouses or building designs utilizing the sun’s heat and

light, and active systems, which use mechanical methods

1194

to convey the sun’s energy. Photovoltaic conversion (PV)

systems use chemical cells that convert the sun’s energy to

electricity. The solar energy industry illustrates how technol-

ogy affects renewable energy development and use. Between

1975 and 1999, the cost of electricity produced by PV sys-

tems declined from a prohibitively expensive $100 per watt

to less than $4 per watt, making the costly technology more

accessible to consumers.

Wind energy accounted for less 1% of United States

renewable energy consumption in 2000. Wind energy is

produced when wind forces the movement of turbines on

windmills, and generators convert that movement into elec-

tricity. Technology improvements helped wind energy to

become the world’s fastest growing alternative energy source

by 2001, lowering its price and making it more competitive

with other energy sources. During the 1990s, the United

States lost its edge in wind energy technology, as countries

such as Germany, Denmark, Spain, and Japan significantly

invested in wind energy production. Global wind electric

production capacity doubled between 1995 and 1998, and

doubled again by 2001, reaching 23,300 megawatts in 2001.

Scientists are busy researching other renewable energy

sources. Some countries are attempting to develop means to

capture the energy in the ocean’s waves (

tidal power

)or

the energy in warm ocean water (

ocean thermal energy

conversion

). Some scientists believe that

hydrogen

may

be the energy source of the future, as hydrogen gas can be

made from water and other compounds. However, no cheap

or efficient method has yet been discovered for taking advan-

tage of highly combustible hydrogen, the most plentiful

chemical element in the universe.

Fossil fuel prices and environmental laws are predicted

to affect the development and use of renewable energy in

the future. Furthermore, technology improvements may

make the cost of producing renewable energy competitive

with fossil fuel energy. Research and development of alterna-

tive energy technology in the future may depend upon gov-

ernment-sponsored initiatives, as they have in the past.

[Douglas Dupler]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Asmus, Peter. Reaping the Wind: How Mechanical Wizards, Visionaries,

and Profiteers Helped Shape Our Energy Future. Washington, DC: Island

Press, 2001.

Dupler, Douglas. Energy: Shortage, Glut, or Enough? Farmington Hills,

MI: Gale, 2001.

Hazen, Mark E., and Michael Hauben. Alternative Energy. Clifton Park,

NY: Delmar Learning, 2001.

Schaeffer, John, and Doug Pratt, eds. Real Goods Solar Living Source Book:

The Complete Guide to Renewable Energy Technologies and Sustainable Living.

Broomfield, CO: Real Goods, 2001.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Reserve Mining Corporation

P

ERIODICALS

Gelbspan, Ross. “A Modest Proposal to Stop Global Warming.” Sierra

(May/June 2001): 63.

O

THER

Energy Information Administration. Renewable Energy Consumption by

Source, 1989–2000. May 7, 2002 [cited July 6, 2002]. <http://www.eia.doe.-

gov/emeu/aer/renew.html>.

O

RGANIZATIONS

Energy Information Administration, 1000 Independence Avenue, SW,

Washington, DC USA 20585 (202) 586-8800, Email: infoctr@eia.doe.gov,

<http://www.eia.doe.gov>

National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 1617 Cole Blvd., Golden, CO

USA 80401-3393 (303) 275-3000, Email: client_services@nrel.gov,

<http://www.nrel.gov>

Renewable Natural Resources

Foundation

The Renewable Natural Resources Foundation (RNRF) was

founded in 1972 to further education regarding renewable

resources in the scientific and public sectors. According to

the organization, it seeks to “promote the application of

sound scientific practices in managing and conserving renew-

able natural resources; foster coordination and cooperation

among professional, scientific, and educational organizations

having leadership responsibilities for renewable resources;

and develop a Renewable Natural Resources Center.”

The Foundation is composed of organizations that

are actively involved with renewable natural resources and

related public policy, including the American Fisheries Soci-

ety, the American

Water Resources

Association, the Asso-

ciation of American Geographers,

Resources for the Fu-

ture

, the

Soil and Water Conservation Society

,

the

Nature Conservancy

, and the

Wildlife

Society. Programs

sponsored by the Foundation include conferences, work-

shops, summits of elected and appointed leaders of RNRF

member organizations, the RNRF Round Table on Public

Policy, publication of the Renewable Resources Journal, joint

human resources development of member organizations, and

annual awards to recognize outstanding contributions to the

field of renewable resources.

In 1992, the RNRF organized the “Congress on Re-

newable Natural Resources: Critical Issues and Concepts for

the Twenty-First Century.” At the Congress, held in Vail,

Colorado, 135 of America’s leading scientists and resource

professionals gathered to discuss critical natural resource

issues that this nation will be facing as the twenty-first

century approaches. According to the Renewable Resources

Journal, the “synergy created by bringing together a diverse

group—resource managers, policymakers, and physical, bio-

1195

logical, and social scientists—resulted in scores of recom-

mendations for innovative policies.”

[Linda Ross]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Renewable Natural Resources Foundation, 5430 Grosvenor Lane,

Bethesda, MD USA 20814-2193 (301) 493-9101, Fax: (301) 493-6148,

Email: info@rnrf.org, <http://www.rnrf.org>

Reserve Mining Corporation

In 1947, the beginnings of one of the first classic cases of

environmental conflict emerged when the Reserve Mining

Corporation received permits to dump up to 67,000 tons per

day of asbestos-like fiber

tailings

from its taconite mining

operations in

Silver Bay

, Minnesota, into western Lake

Superior. The Reserve case typifies the conflict that occurs

when the complex problems of

pollution

, economics, poli-

tics, and law collide. After decades of investigation and law-

suits, the corporation stopped the dumping in spring 1980,

but the change did not come easily for any of the participants.

Taconite is a low-grade iron ore, which can be crushed,

concentrated, and pelletized to provide a good source of iron

ore. Silver Bay, Minnesota, was created as a result of the

mine’s development by Reserve, and approximately 80% of

the local labor force of 3,500 residents worked at the $350

million facility in 1980. The first permits were given to the

company in 1947, on the condition that it would strictly

comply with all provisions, including providing continued

assurances that the discharges posed no harm to the lake or

surrounding inhabitants. In 1956 and 1960, Reserve was

allowed to increase its use of Lake Superior water, thus

increasing its dumping of waste taconite tailings. This con-

tinued until the late 1960s, when two major signs emerged

that the lake—and potentially local residents—were being

harmed by the waste discharges.

The first sign was the obvious discoloration of the

water on the northwest shores of Lake Superior. Up to

67,000 tons of tiny fibers resembling

asbestos

,a

carcino-

gen

, were dumped into the lake each day, turning the water

into a green slime from Silver Bay to Duluth, Minnesota,

and nearby Superior, Wisconsin. Second, several local citi-

zens made the link between the company’s

discharge

and

possible harmful effects on humans when they read about a

discovered connection between

cancer

and asbestos used to

polish rice in Japan in the 1960s.

By June 1973, after completing several studies at the

request of these local citizens, the U.S.

Environmental Pro-

tection Agency

concluded that the drinking water of Duluth

and other northshore communities was contaminated with

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Reservoir

asbestos-like fibers, which might cause cancer. The Minne-

sota

Pollution Control

Agency followed with the finding

that a suspected source of the fibers was the Reserve Mining

Corporation discharge. Duluth and other affected communi-

ties installed

filtration

systems to prevent further contamina-

tion of local drinking water supplies, and convinced state

and federal agencies to join citizen groups in legal action

against the company.

In a series of subsequent court appearances, Reserve

continually argued that the company would be forced to

close its operations if Lake Superior discharges were stopped,

presumably resulting in the demise of the town of Silver

Bay as well. Five years of lawsuits seemingly ended on April

20, 1974, when federal District Judge Miles Lord completed

a nine-month trial and ordered the plant to cease discharges

of taconite tailings into the air and water within 24 hours.

Less than 48 hours later, however, the plant was ordered

reopened by three judges from the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court

of Appeals. While concluding that the original permits is-

sued to Reserve Mining were a “monumental environmental

mistake,” they allowed the company to remain open while

it altered its production process to create alternative disposal

methods. In June 1974, the governors of Minnesota and

Wisconsin filed an appeal of this ruling to the Supreme

Court, but were rebuffed when the court refused to reinstate

Judge Lord’s order. Justice William Douglas’ written dissent

to the court’s ruling stated, “I am not aware of a constitutional

principle that allows either private or public enterprises to

despoil any part of the domain that belongs to all of the

people. Our guiding principle should be Mr. Justice Holmes’

dictum that our waterways, great and small, are treasures

not

garbage

dumps or cesspools.”

Six years later, Reserve Mining Company and its parent

owners Armco and Republic Steel were fined more than one

million dollars for their permit violations and intransigence

in completing disposal upgrades. Reserve switched to onland

disposal, via rail and pipeline, to a 6-mi

2

(9.7-km

2

) basin 40

mi (64.4 km) inland, which kept tailings covered under 10 ft

(3 m) of water to prevent fiber dust from escaping. The basin

operated efficiently until a production cut resulted in more

water and plant

effluent

being sent to the disposal basin than

was used in the plant to concentrate the crushed taconite rock

into iron ore. Reserve sought a permit in October 1985 from

the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency to pump water out

of the disposal basin to a filtration plant on the Beaver River,

which flows into Lake Superior. After several arguments from

environmental groups and others, the permit was eventually

issued at a lowered level from 15 to 1 million fibers per liter.

Operations ultimately closed in the summer of 1986, due to

reduced demand for the taconite pellets.

The mine was purchased and reopened in 1990 by

Cyprus Mining of Colorado, and operated at 30% of capac-

1196

ity. The one-million-fiber-per-liter limit has generally been

met, and thus asbestos-like fibers continue to be discharged

into Lake Superior, albeit at a drastically reduced rate from

those discharged for decades directly into the largest fresh-

water lake in the world.

[Sally Cole-Misch]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Rousmaniere, J., ed. The Enduring Great Lakes, A Natural History Book.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1979.

P

ERIODICALS

Merritt, Grant. “The Reserve Mining Case: Promises, Promises.” Great

Lakes Focus on Water Quality 1, no. 1 (Fall 1974): 1–3.

———. “The Reserve Mining Case—20 Years Later.” Focus on International

Joint Commission Activities 19, no. 3 (November/December 1994): 1–4.

“Tailings’ End.” Time, March 31, 1980, 45.

Reservoir

A reservoir is a body of water held by a dam on a river or

stream, usually for use in

irrigation

, electricity generation,

or urban consumption. By catching and holding floods in

spring or in a rainy season, reservoirs also prevent

flooding

downstream. Most reservoirs fill a few miles of river basin,

but large reservoirs on major rivers can cover thousands of

square miles. Lake Nasser, located behind Egypt’s

Aswan

High Dam

, stretches 310 miles (500 km), with an average

width of 6 miles (10 km). Utah’s Lake Powell, on the

Colo-

rado River

, fills almost 93 miles (150 km) of canyon.

Because of their size and their role in altering water

flow in large ecosystems, reservoirs have a great number of

environmental effects, positive and negative. Reservoirs

allow more settlement on flat, arable flood plains near the

river’s edge because the threat of flooding is greatly dimin-

ished. Water storage benefits farms and cities by allowing

a gradual release of water through the year. Without a dam

and reservoir, much of a river’s annual

discharge

may pass

in a few days of flooding, leaving the river low and muddy

the rest of the year. Once a reservoir is built, water remains

available for irrigation, domestic use, and industry even in

the dry season.

At the same time, the negative effects of reservoirs

abound. Foremost is the destruction of instream and stream

side vegetation and

habitat

caused by flooding hundreds of

miles of river basin behind reservoirs. Because reservoirs

often stretch several miles across, as well as far upstream,

they can drown habitat essential to aquatic and terrestrial

plants, as well as extensive tracts of forest. Humans also

frequently lose agricultural land and river-side cities to reser-

voir flooding. China’s proposed

Three Gorges Dam

on the