Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Cancer

tional Trade in

Endangered Species

of Fauna and Flora

(CITES), and the Ramsar

Convention on Wetlands of

International Importance

. Furthermore, it has increased

responsibility on federal lands, north of 60°N latitude, al-

though in recent years much responsibility has been dele-

gated to the territorial wildlife services and local co-manage-

ment agreements with aboriginal peoples.

Within those statutes and agreements CWS is respon-

sible for policy and strategy development, enforcement, re-

search, public relations, education and interpretation,

habi-

tat

classification, and the management of about 98

sanctuaries and 49 wildlife areas. The combination of a

national and international mandates and diverse landscapes

of Canada make CWS the pivotal

wildlife management

institution in Canada. However, CWS’s increasing reliance

on cooperative measures with provincial governments and

nongovernmental organizations, including

Ducks Unlimited

Canada and

World Wildlife Fund

Canada, has led the orga-

nization to less direct management and more coordination

activities. Critics of Canada’s wildlife management direction

have suggested that the once world-renowned repository of

research expertise in CWS has suffered in recent years.

[David A. Duffus]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Ottawa, Ontario Canada

K1A 0H3 (819) 997-1095, Fax: (819) 997-2756 , Email: cws-scf@ec.gc.ca,

<http://www.cws-scf.ec.gc.ca>

Cancer

A malignant tumor, cancer comprises a broad spectrum of

malignant neoplasms classified as either carcinomas or sarco-

mas. Carcinomas originate in the epithelial tissues, while sar-

comas originate from connective tissues and structures that

have their origin in mesodermal tissue. Cancer is an invasive

disease that spreads to various parts of the body. It spreads

directly to those tissues immediately surrounding the primary

site of the cancer and may spread to remote parts of the body

through the lymphatic and circulatory systems.

Cancer occurs in most, if not all, multicellular animals.

Evidence from fossil records reveal bone cancer in dinosaurs,

and sarcomas have been found in the bones of Egyptian

mummies. Hippocrates is credited with coining the term

carcinoma, the Greek word for crab. Why the word for crab

was chosen enjoys much speculation, but may have had to

do with the sharp, biting pain and invasive, spreading nature

of the disease.

A

carcinogen

is any substance or agent that produces

or induces the development of cancer. Carcinogens are

207

known to affect and initiate metabolic processes at the level

of DNA (the information-storing molecules in cells). DNA

damage (

mutation

) is the development of cancer after expo-

sure to a carcinogen. This kind of mutation is actually revers-

ible; our bodies continually experience DNA damage, which

is continually being corrected. It is only when promoter

cells intervene during cell proliferation that tumors begin to

develop. Although several agents can induce cell division,

only promoters induce tumor development.

An example of this process would be what happens

in an epidermal cell, when its DNA undergoes rapid, irre-

versible alteration or mutation after exposure to a carcinogen.

The cell undergoes proliferation, producing altered progeny,

and it is at this point that the cell may proceed on one of

two pathways. The cell may undergo interrupted exposure

to promoters and experience early reversible precancerous

lesions. Or it may experience continuous exposure to the

promoters, thereby causing malignant cell changes. During

the late phase of promotion, the primary epidermal cell

becomes tumorous and begins to invade normal cells; then

it begins to spread. It is at this stage that tumors are identified

as malignant.

The spread of tumors throughout the body is believed

to be governed by several processes. One possible mechanism

is direct invasion of contiguous organs. This mechanism is

poorly understood, but it involves multiplication, mechanical

pressure, release of lytic enzymes, and increased motility of

individual tumor cells. A second process is metastasis. This

is the spread of cancer cells from a primary site of origin to

a distant site, and it is the life-threatening aspect of malig-

nancy. At present there are many procedures available to

surgeons for successfully eradicating primary tumors; how-

ever, the real challenge in reducing cancer

mortality

is find-

ing ways to control metastasis.

Clinical manifestations of cancer take on many forms.

Usually little or no pain is associated with the early stages

of malignant disease, but pain does affect 60–80% of those

terminally ill with cancer. General mechanisms causing pain

associated with cancer include pressure, obstruction, invasion

of a sensitive structure, stretching of visceral surfaces, tissue

destruction, and inflammation. Abdominal pain is often

caused by severe stretching from the tumor invasion of the

hollow viscus, as well as tumors that obstruct and distend

the bowel. Tumor compression of nerve endings against a

firm surface also creates pain. Brain tumors have very little

space to grow without compressing blood vessels and nerve

endings between the tumor and the skull. Tissue destruction

from infection and necrosis can also cause pain. Frequently

infection occurs in the oral area, in which a common cause

of pain is ulcerative lesions of the mouth and esophagus.

Cancer treatments involve chemotherapy, radiother-

apy, surgery, immunotherapy, and combinations of these

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Captive propagation and reintroduction

Frequency of Cancer-Related Death

Number of Deaths

Cancer Site Per Year

Lung 160,100

Colon and rectum 56,500

Breast 43,900

Prostate 39,200

Pancreas 28,900

Lymphoma 26,300

Leukemia 21,600

Brain 17,400

Stomach 13,700

Liver 13,000

Esophagus 11,900

Bladder 12,500

Kidney 11,600

Multiple myeloma 11,300

modalities. Chemotherapy and its efficacy is related to how

the drug enters the cell cycle; the design of the therapy is

to destroy enough malignant cells so that the body’s own

immune system can destroy the remaining cells naturally.

Smaller tumors with rapid growth rates seem to be most

responsive to chemotherapy. Radiation therapy is commonly

used to eradicate tumors without excessive damage to sur-

rounding tissues. Radiation therapy attacks the malignant

cell at the DNA level, disrupting its ability to reproduce.

Surgery is the treatment of choice when it has been deter-

mined that the tumor is intact and has not metastasized

beyond the limits of surgical excision. Surgery is also indi-

cated for benign tumors that could progress into malignant

tumors. Premalignant and in situ tumors of epithelial tissues,

such as skin, mouth, and cervix, can be removed.

Chemotherapy and radiation treatments are the most

commonly used therapies for cancer. Unfortunately, both

methods produce unpleasant side effects; they often suppress

the immune system, making it difficult for the body to

destroy the remaining cancer even after the treatment has

been successful. In this regard, immunotherapy holds great

promise as an alternative treatment, because it makes use of

the unique properties of the immune system.

Immunotherapies for the treatment of cancer are gen-

erally referred to as biological response modifiers (BRMs).

BRMs are defined as mammalian gene products, agents,

and clinical protocols that affect biologic responses in host-

tumor interactions. Immunotherapies have a direct cytotoxic

effect on cancer cells, initiation or augmentation of the host’s

208

tumor-immune rejection response, and modification of can-

cer cell susceptibility to the lytic or tumor static effects of

the immune system. As with other cancer therapies immuno-

therapies are not without their own side effects. Most com-

mon are flu-like symptoms, skin rashes, and vascular-leak

syndrome. At their worst, these symptoms are usually less

severe than those of current chemotherapy and radiation

treatments. See also Hazardous material; Hazardous waste;

Leukemia; Radiation sickness

[Brian R. Barthel]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Aldrich, T., and J. Griffith. Environmental Epidemiology. New York: Van

Nostrad Reinhold, 1993.

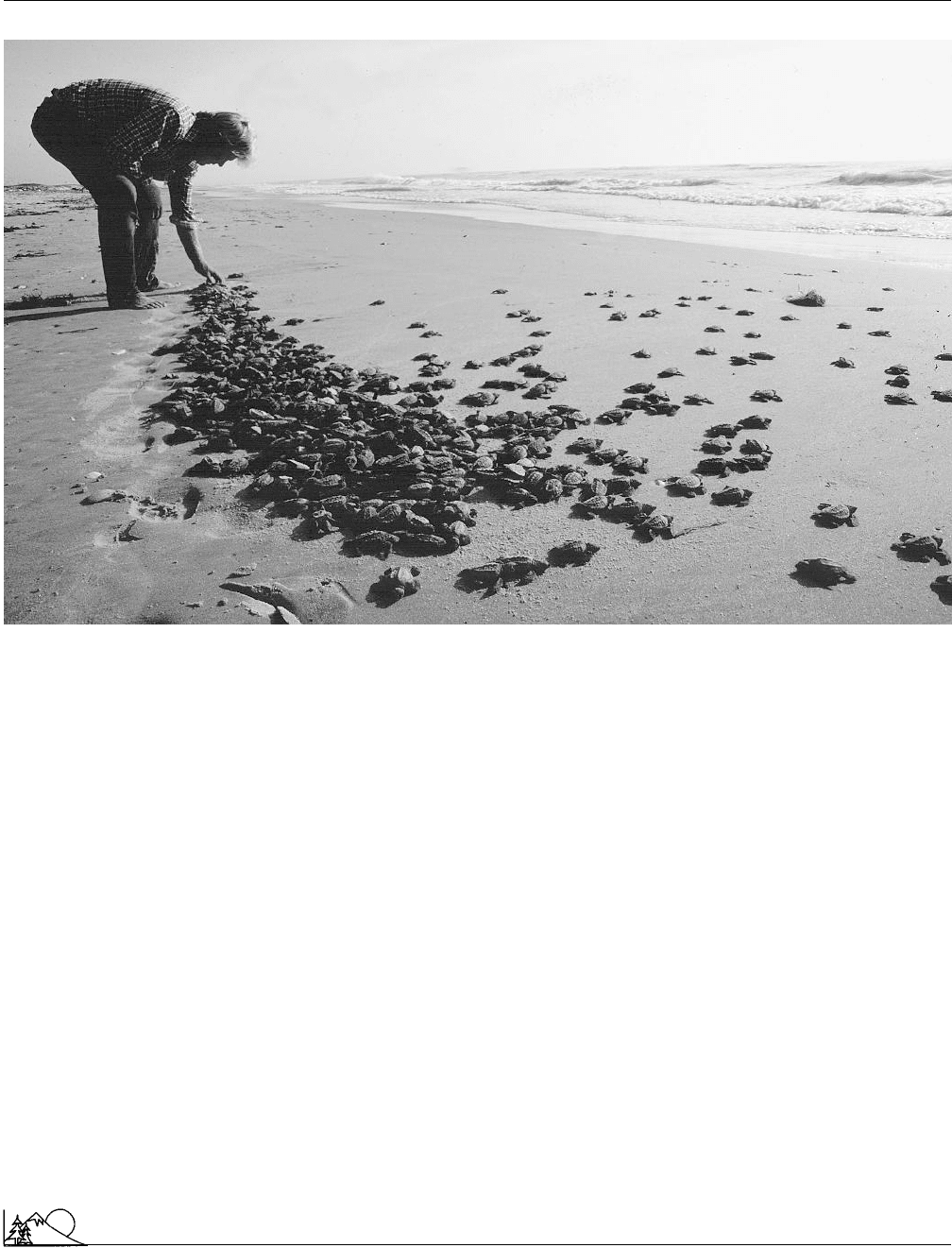

Captive propagation and

reintroduction

Captive propagation is the deliberate breeding of wild ani-

mals in captivity in order to increase their numbers. Reintro-

duction is the deliberate release of these

species

into their

native

habitat

. The Mongolian wild horse, Pere David’s

deer, and the American

bison

would probably have become

extinct without captive propagation. Nearly all cases of cap-

tive propagation and reintroduction involve threatened or

endangered species

. Zoos are increasingly involved in cap-

tive propagation, sometimes using new technologies. One

of these, allows a relatively common species of antelope to

act as a surrogate mother and give birth to a

rare species

.

Once suitable sites are selected, a reintroduction can

take one of three forms. Reestablishment reintroductions take

place in areas where the species once occurred but is now

entirely absent. Recent examples include the red wolf, the

black-footed ferret

, and the

peregrine falcon

east of the

Mississippi River. Biologists use augmentation reintroduction

to release captive-born wild animals into areas in which the

species still occurs but only in low numbers. These new

animals can help increase the size of the population and

enhance genetic diversity. Examples include a small Brazilian

monkey called the golden lion tamarin and the peregrine

falcon in the western United States. A third type, experimen-

tal reintroduction, acts as a test case to acquire essential infor-

mation for use on larger-scale permanent reintroductions.

The red wolf was first released as an experimental reintroduc-

tion. A 1982 amendment to the

Endangered Species Act

facilitates experimental reintroductions, offering specific ex-

emptions from the Act’s protection, allowing managers

greater flexibility should reintroduced animals cause unex-

pected problems.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Captive propagation and reintroduction

The release of baby Kemp’s ridley sea turtles on a beach in Mexico. (Photograph by C. Allan Morgan. Peter Arnold Inc.

Reproduced by permission.)

Yet captive propagation and reintroduction programs

have their drawbacks, the chief one being their high cost.

Capture from the wild, food, veterinary care, facility use and

maintenance all contribute significant costs to maintaining

an animal in captivity. Other costs are incurred locating

suitable reintroduction sites, preparing animals for release,

and monitoring the results. Some conservationists have ar-

gued that the money would be better spent acquiring and

protecting habitat in which remnant populations already live.

There are also other risks associated with captive pro-

pogation programs such as disease, but perhaps the greatest

biological concern is that captive populations of endangered

species might lose learned or genetic traits essential to their

survival in the wild. Animals fed from birth, for example,

might never pick up food-gathering or prey-hunting skills

from their parents as they would in the wild. Consequently,

when reintroduced such animals may lack the skill to feed

themselves effectively. Furthermore, captive breeding of ani-

mals over a number of generations could affect their

evolu-

tion

. Animals that thrive in captivity might have a selective

advantage over their “wilder” cohorts in a

zoo

, but might

209

be disadvantaged upon reintroduction by the very traits that

aided them while in captivity.

Despite these shortcomings, the use of captive propa-

gation and reintroduction will continue to increase in the

decades to come. Biologists learned a painful lesson about

the fragility of endangered species in 1986 when a sudden

outbreak of canine distemper decimated the only known

group of black-footed ferrets. The last few ferrets were taken

into captivity where they successfully bred. Even as new

ferret populations become established through reintroduc-

tion, some ferrets will remain as captive breeders for insur-

ance against future catastrophes. Biologists are also steadily

improving their methods for successful reintroduction. They

have learned how to select the combinations of sexes and

ages that offer the best chance of success and have developed

systematic ways to choose the best reintroduction sites.

Captive propagation and reintroduction will never be-

come the principal means of restoring threatened and endan-

gered species, but it has been proven effective and will con-

tinue to act as insurance against sudden or catastrophic losses

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Carbon

in the wild. See also Biodiversity; Extinction; Wildlife man-

agement; Wildlife rehabilitation

[James H. Shaw]

R

ESOURCES

P

ERIODICALS

Jones, Suzanne R., ed. “Captive Propagation and Reintroduction: A Strategy

for Preserving Endangered Species?” Endangered Species Update 8 (1) (1990):

1-88.

Lindburg, Donald G. “Are Wildlife Reintroductions Worth the Cost?”

Zoo Biology 11 (1992): 1-2.

Carbamates

see

Pesticide

Carbon

The seventeenth most abundant element on earth, carbon

occurs in at least six different allotropic forms, the best

known of which are diamond and graphite. It is a major

component of all biochemical compounds that occur in living

organisms: carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.

Carbon-rich rocks and minerals such as limestone, gypsum,

and marble often are created by accumulated bodies of

aquatic organisms. Plants, animals, and

microorganisms

cycle carbon through the

environment

, converting it from

simple compounds like

carbon dioxide

and

methane

to

more complex compounds like sugars and starches, and then,

by the action of

decomposers

, back again to simpler com-

pounds. One of the most important

fossil fuels

,

coal

,is

composed chiefly of carbon.

Carbon cycle

Carbon

makes up no more than 0.27% of the mass of all

elements in the universe and only 0.0018% by weight of the

elements in the earth’s crust. Yet, its importance to living

organisms is far out of proportion to these figures. In contrast

to its relative

scarcity

in the

environment

, it makes up

19.4% by weight of the human body. Along with

hydrogen

,

carbon is the only element to appear in every organic mole-

cule in every living organism on earth.

The series of chemical, physical, geological, and bio-

logical changes by which carbon moves through the earth’s

air, land, water, and living organisms is called the carbon

cycle.

In the

atmosphere

, carbon exists almost entirely as

gaseous

carbon dioxide

. The best estimates are that the

earth’s atmosphere contains 740 billion tons of this gas. Its

210

global concentration is about 350

parts per million

(ppm),

or 0.035% by volume. That makes carbon dioxide the fourth

most abundant gas in the atmosphere after

nitrogen

, oxygen

and argon. Some carbon is also released as

carbon monox-

ide

to the atmosphere by natural and human mechanisms.

This gas reacts readily with oxygen in the atmosphere, how-

ever, converting it to carbon dioxide.

Carbon returns to the hydrosphere when carbon diox-

ide dissolves in the oceans, as well as in lakes and other

bodies of water. The solubility of carbon dioxide in water

is not especially high, 88 milliliters of gas in 100 milliliters

of water. Still, the earth’s oceans are such a vast

reservoir

that experts estimate that approximately 36,000 billion tons

of carbon are stored there. They also estimate that about 93

billion tons of carbon flows from the atmosphere into the

hydrosphere each year.

Carbon moves out of the oceans in two ways. Some

escapes as carbon dioxide from water solutions and returns

to the atmosphere. That amount is estimated to be very

nearly equal (90 billion tons) to the amount entering the

oceans each year. A smaller quantity of carbon dioxide (about

40 billion tons) is incorporated into aquatic plants.

On land, green plants remove carbon dioxide from the

air through the process of photosynthesis—a complex series

of chemical reactions in which carbon dioxide is eventually

converted to starch, cellulose, and other carbohydrates.

About 100 billion tons of carbon are transferred to green

plants each year, and a total of 560 billion tons of the element

is thought to be stored in land plants alone.

The carbon in green plants is eventually converted into

a large variety of organic (carbon-containing) compounds.

When green plants are eaten by animals, carbohydrates and

other organic compounds are used as raw materials for the

manufacture of thousands of new organic substances. The

total collection of complex organic compounds stored in all

kinds of living organisms represents the reservoir of carbon

in the earth’s

biosphere

.

The cycling of carbon through the biosphere involves

three major kinds of organisms. Producers are organisms

with the ability to manufacture organic compounds such as

sugars and starches from inorganic raw materials such as

carbon dioxide and water. Green plants are the primary

example of producing organisms. Consumers are organisms

that obtain their carbon (that is, their food) from producers:

all animals are consumers. Finally,

decomposers

are organ-

isms such as bacteria and

fungi

that feed on the remains of

dead plants and animals. They convert carbon compounds

in these organisms to carbon dioxide and other products.

The carbon dioxide is then returned to the atmosphere to

continue its path through the carbon cycle.

Land plants return carbon dioxide to the atmosphere

during the process of

respiration

. In addition, animals that

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Carbon emissions trading

eat green plants exhale carbon dioxide, contributing to the

50 billion tons of carbon released to the atmosphere by

all forms of living organisms each year. Respiration and

decomposition

both represent, in the most general sense,

a reverse of the process of

photosynthesis

. Complex organic

compounds are oxidized with the release of carbon dioxide

and water—the raw materials from which they were origi-

nally produced.

At some point, land and aquatic plants and animals

die and decompose. When they do so, some carbon (about

50 billion tons) returns to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

The rest remains buried in the earth (up to 1,500 billion

tons) or on the ocean bottoms (about 3,000 billion tons).

Several hundred million years ago, conditions of burial were

such that organisms decayed to form products consisting

almost entirely of carbon and

hydrocarbons

. Those materi-

als exist today as pockets of the fossil fuels—coal, oil, and

natural gas

. Estimates of the carbon stored in

fossil fuels

range from 5,000 to 10,000 billion tons.

The processes that make up the carbon cycle have

been occurring for millions of years, and for most of this

time, the systems involved have been in equilibrium. The

total amount of carbon dioxide entering the atmosphere

from all sources has been approximately equal to the total

amount dissolved in the oceans and removed by photosyn-

thesis. However, a hundred years ago changes in human

society began to unbalance the carbon cycle. The Industrial

Revolution initiated an era in which the burning of fossil

fuels became widespread. In a short amount of time, large

amounts of carbon previously stored in the earth as

coal

,

oil, and natural gas were burned up, releasing vast quantities

of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Between 1900 and 1992, measured concentrations of

carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increased from about 296

ppm to over 350 ppm. Scientists estimate that fossil fuel

combustion

now released about five billion tons of carbon

dioxide into the atmosphere each year. In an equilibrium

situation, that additional five billion tons would be absorbed

by the oceans or used by green plants in photosynthesis. Yet

this appears not to be happening: measurements indicate

that about 60% of the carbon dioxide generated by fossil

fuel combustion remains in the atmosphere.

The problem is made even more complex because of

deforestation

. As large tracts of forest are cut down and

burned, two effects result: carbon dioxide from forest fires

is added to that from other sources, and the loss of trees

decreases the worldwide rate of photosynthesis. Overall, it

appears that these two factors have resulted in an additional

one to two billion tons of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere

each year.

No one can be certain about the environmental effects

of this disruption of equilibria in the carbon cycle. Some

211

authorities believe that the additional carbon dioxide will

augment the earth’s natural

greenhouse effect

, resulting

in long-term global warming and

climate

change. Other

argue that we still do not know enough about the way

oceans, clouds, and other factors affect climate to allow such

predictions.

This controversy involves a difficult choice. Should

actions that could potentially cost billions of dollars be taken

to reduce the

emission

of carbon dioxide when evidence

for climate change is still uncertain? Or should governments

wait until that evidence becomes more clear, with the risk

that needed actions may then come too late.

[David E. Newton]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology. 7th ed. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 1992.

Carbon dating

see

Radiocarbon dating

Carbon dioxide

The fourth most abundant gas in the earth’s

atmosphere

,

carbon

dioxide occurs in an abundance of about 350

parts

per million

. The gas is released by volcanoes and during

respiration

,

combustion

, and decay. Plants convert carbon

dioxide into carbohydrates by the process of

photosynthe-

sis

. Carbon dioxide normally poses no health hazard to

humans. An important factor in maintaining the earth’s

climate

, molecules of carbon dioxide capture heat radiated

from the earth’s surface, raising the planet’s temperature to

a level at which life can be sustained, a phenomenon known

as the

greenhouse effect

. Some scientists believe that in-

creasing levels of carbon dioxide resulting from human activi-

ties are now contributing to a potentially dangerous global

warming.

Carbon emissions trading

Carbon

emissions trading (CET) is a practice allowing coun-

tries—and corporations—to trade their harmful carbon emis-

sions for credit to meet their designated carbon

emission

lim-

its. Most developed countries approved this system in 1992

whenthe United Nations FrameworkConvention on Climate

Change (UNFCCC) was presented. The document provided

for limits on greenhouse gas emissions in an attempt to stem

the determination of climate change around the world. The

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Carbon emissions trading

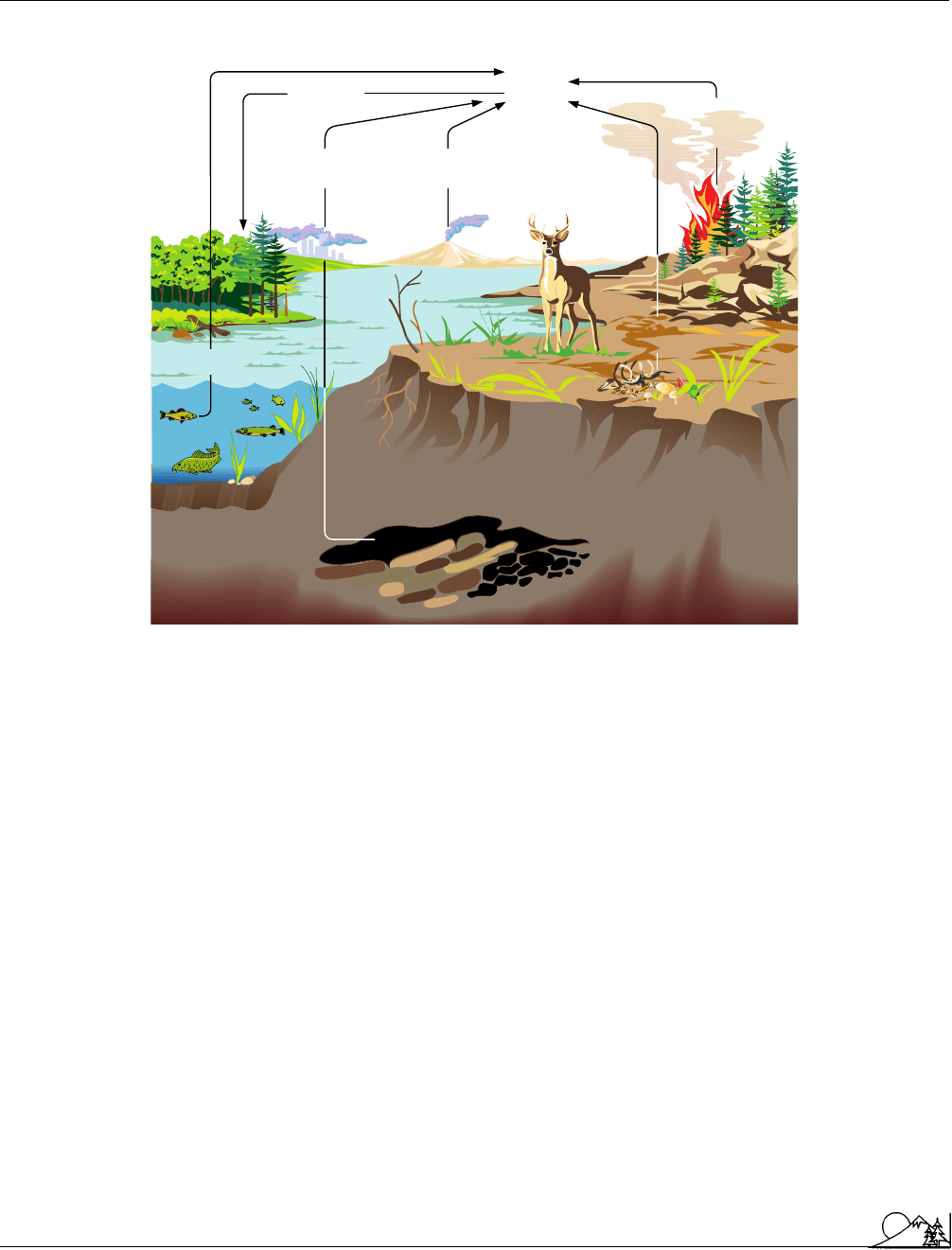

Carbon

dioxide in

atmosphere

Photosynthesis

Fires from use of

fuel wood and

conversion of

forest to agriculture

Aerobic respiration and

decay (plants, animals,

and decomposers)

Carbon

released from

volcanoes

Combustion, and

the manufacturing

of cement

Fossil fuels

Aerobic respiration

and decay

Stored in sediments

Carbon cycle. (Illustration by Hans & Cassidy.)

United States as of 2001 had backed away from the Kyoto

Treaty stating similar restriction but would remain obligated

in some regard to the UNFCCC. At least in theory, CET

allows one country who might not be maintaining their target

to trade credits with others that are well under theirs.

According to information from the Australian Acad-

emy of Science, in Nova: Science in the news,

carbon dioxide

(CO2) is known as a “greenhouse gas” ones that came out

of the Earth’s crust before life was known to begin, helping

to stabilize the earth’s temperatures in order to sustain life.

The “greenhouse effect” occurs when the sun’s heat energy

passes through the

atmosphere

and warms up the earth

with no interference. The Earth then radiates that same

energy back into space. Other

greenhouse gases

include,

water vapor (the primary greenhouse gas),

methane

,

ozone

,

carbon monoxide

, and

nitrous oxide

. All of these absorb

part of this energy and send it in all directions—including the

Earth. By the twenty-first century however, the emissions of

greenhouse gases were not in the balance they had been for

ages due to human activity, particularly that of burning

fossil

fuels

such as

coal

, oil, and

natural gas

. Due to that, and

to industrial development as well as residential development

212

in the developed countries, forests were cleared at such a

rate that inclined some scientists to wonder whether these

practices were harmful in the significantly increased emis-

sions of greenhouse gases.

The

Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA)

launched a method of emissions trading known as, Online

Allowance Transfer System (OATS). It is an online system

that allows companies engaged in the

sulfur dioxide

and

nitrogen

oxide to record trades directly through the internet

without having to file papers with the EPA. No such method

yet exists for CET. In view of possible future issues regarding

the trades in the United States in February 2002, Senators

John McCain (R.-Ariz) and Sam Brownback(R.-Kan.)

jointly introduced legislation that propsed establishing a na-

tional voluntary registry for companies to register carbon

emission reductions. According to Coal Age “The propsal is

a step toward developing a ’cap-and-trade’ carbon emissions

control program.” Senators McCain and Leiberman (D.-

CT) are also working on legislation that supports carbon

emissions trading. McCain, noted Coal Age said that, “The

registry would support current voluntary trading practices in

private industry and other nongovernmental organizations.”

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Carbon emissions trading

The real issue that has resulted from CET is the

trading market that has emerged. Opinions are varied re-

garding the advisability, and inherent dangers of CET. The

International Carbon Bank & Exchange offered insight on

CET through its web site. “Emissions trading reduces costs

by allowing a field of players to achieve emissions redutions

using market mechanisms. Over time, these mechanisms

will drive emissions down and finance the shift to clean

energy.”

In August 2001, the Joyce Foundation granted

$760,100 to fund the design phase of the Chicago Climate

Exchange (CCX). The grant was actually directed to the J. L.

Kellogg Graduate School of Management at Northwestern

University in support of the work being done by Dr. Richard

Sandor, an internationally-known trader. With the presiden-

tial administration of George W. Bush hesitant to apply a

“cap-and-trade” system, the direction of the CCX and open

market trading is viewed as providing a desirable alterna-

tive—particularly in light of the United States withdrawal

from the Kyoto Treaty. According the Environmental News

Network (ENN) in an article on the new design program,

“The CCX’s stated goal is to reduce participants’ greenhouse

gas emissions by five percent below 1999 levels over five

years. By comparison, the countries that ratified the Kyoto

Protocol must reduce emissions of carbon dioxide to an

average of 5.2% below 1990 levels during the five-year period

2008 to 2012.” By November 2001, the cities of Chicago

and Mexico City announced their participation in CET by

joining the CCX, with Chicago becoming the first American

city to do so. Chicago’s Mayor Richard Daley became honor-

ary chair of the exchange, still in the design phase. He noted

that, “For years our financial exchanges have been a vital

parto f the local and naitonal economy. This is a good

example of the kind of innovation that will help us solve

our energy and environmental problems,” according to the

Environment News Service. Other businesses and agencies

participating in the design phase of the CCX including,

Agrilance, a partnership of agricultural producer-owners,

local cooperatives and regional cooperatives; BP; Cinergy;

Ducks Unlimited

; DuPont; the energy company, Exeton;

International Paper; the Iowa Farm Bureau Federation;

Manitoba (CA) Hydro; National Council of Farmer Coop-

eratives; PG&E National Energy Group; Suncor Energy;

Swiss Re, a reinsurance firm;

The Nature Conservancy

;

and, Waste Energy.

On a broader scope of international trading, however,

the United States’ withdrawal from Kyoto was posing a

possible problem. Due to the lack of participation, U.S.

companies were seeing a possible short-term advantage in

international business competition due to lower costs with-

out the emissions trading—but those same companies, such

as DuPont, already cutting emissions, might face the long-

213

term shortchange depending on which way the international

climate change policy could effect trading those emissions.

In March 2002, Julie Vorman writing on the CET market

for Reuters quoted Eileen Claussen, president of the Pew

Center on Global Climate Change, noting that, “Despite

the United States inaction, it is abundantly clear that we are

beginning to see the outlines of a genuine greenhouse gas

market.” Also, according to Vorman, “The Pew Center re-

port said more than 65 trades of greenhouse gas emissions

totaling 55 million to 77 million tons have occurred over

the past five years [since the 1997 Kyoto Protocol was intro-

duced] but that those gifures probably underestimate the

market activity. The emissions reductions traded for between

60 cents and $3.50 (U.S. dollars) per ton of carbon dioxide

equivalent. (The date did not include trades within BP Pic

and Royal Dutch Shell, which launched their own internal

cap-and-trade programs in 1998 to cut emissions.)

The role of the agricultural industry in CET was being

explored along with its options with the CCX. According

to the American Farm Bureau, one of the plans under consid-

eration was a plan to pay farmers for agricultural practices

reducing carbon emissions into the atmosphere. “Farmers

would be compensated for implementing or continuing prac-

tices that reduce carbon emissions from the soils. Such prac-

tices include reducing tillage, conserving tillage, retiring

cropland, fertilizing with livestock manure, decreasing meth-

ane and reducing energy use. The compensation could po-

tentially come from the government or companies that are

interested in “trading” carbon credits.” The Kyoto Protocol

does not provide that option; but the Untied States wanted

to consider it as a part of the UNFCCC. Jon Doggett, a

senior director of governmental relations for the American

Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) added the caveat that such

a practice of carbon sequestration in the soil—a practice

some Americans support in opposition to European leaders

who do not have the amount of land for such a program to

succeed as does the United States—could be harmful to

farmers in the long-term. Doggett noted that, “The indus-

tries that will be required to purchase the carbon credits

supply farmers with vital operating materials, including fuel

and

fertilizer

. As regulatory costs for companies rise, farmers

will pay for that as fuel and fertilizer costs go up. The

AFBF also pointed out that such storage might disrupt other

environmetally beneficial practices—such as that employed

by California producers after harvest when they flood their

land and provide a

habitat

for geese and ducks. The issues

of trading the benefits of one environmental concern for

that of another would remain a matter of debate well into

the century, no doubt.

Environmentalists continued to express concern that

CET practices, particularly ones that were regulated volunta-

rily on the open market, would not reduce the greenhouse

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Carbon monoxide

gases to the extent that some scientists thought crucial to

the planet’s optimum survival. The ongoing debate on the

theory of global warming raged on in the United States

particularly. Business and industrial interests questioned the

soundness of the theory, and worried that it would create

serious obstacles to profits that might be translated into

the research necessary for better energy alternatives. Those

supporting the theory were concerned with declining stan-

dards for

pollution

controls that might enhance the

green-

house effect

. The voluntary controls industry and countries

would place on themselves were nonetheless considered the

first step to creating a cleaner

environment

.

[Jane E. Spear]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

International Carbon Bank & Exchange. About Emissions Trading. “Emis-

sion Reduction Credits & Trading.” (June 2002). <http://www.icbe.com/>.

O

THER

Australian Academy of Science. Nova: Science in the News. “Carbon cur-

rency—the credits and debits of carbon emissions trading.” (June 2002).

<http://www.science.org.au/>

Chicago Climatex. Emissions Trading. (June 2002). <http://www.chica-

goclimatex.com/>

Coal Age. Primedia Business Magazines. “McCain, Brownback Move on

Emissions.” Feb. 1, 2002. <http://www.industrycli.../>

DMOZ. Open Directory.“Emissions Trading.” April 16, 2002. <http://

www.dmoz.org/Science/Environment/>

Earth Council. Carbon Trading: A Market Approach to the Environmental

Crisis. July 1997; (June 2002). <http://www.igc.apc.org/globalpolicy/>

Environmental News Network. Trading for clean air just got easier. December

5, 2001. <http://www.enn.com/>

Environmental News Network. First U.S. Carbon Trading Market Enters

Design Phase. August 8, 2001. <http://www.enn.com/>

Environment News Service. Environment. “Carbon Trading Market Ex-

pands to Chicago, Mexico City.” November 13, 2001. <http://www.ens.

lycos.com/ens/>

Eye for Energy. CO2 Trading: The North American Market. “Opportunities,

compliance and profit in domestic and international greenhouse gas emis-

sions trading.” June 2002. <http://www.eyeforenergy.com/>

Farm Bureau. Global Climate Change. “Agriculture’s role discussed in carbon

trading.” June 22, 2000; (June 2002). <http://www.fb.com/>

Houlder, Vanessa. FT (Financial Times). “US opposition to Kyota may

sink carbon trading.” August 13, 2001. <http://news.ft.com/>

Vorman, Julie. Reuters. “Greenhouse trading takes off, U.S. on sidelines.”

March 20, 2002). <http://www.enn.com/news/wire-stories/>

O

RGANIZATIONS

U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W.,

Washington, D.C. United States 20460 (202)260-2090, www.epa.gov

Carbon monoxide

A colorless, odorless, tasteless gas that is produced in only

very small amounts by natural processes. By far the most

214

important source of the gas is the incomplete

combustion

of

coal

, oil, and

natural gas

. In terms of volume,

carbon

monoxide is the most important single component of

air

pollution

. Environmental scientists rank it behind sulfur

oxides,

particulate

matter,

nitrogen oxides

, and volatile

organic compounds, however, in terms of its relative hazard

to human health. In low doses, carbon monoxide causes

headaches, nausea, fatigue, and impairment of judgment. In

larger amounts, it causes unconsciousness and death.

Carbon offsets (CO

2

-emission offsets)

Many human activities result in large emissions of

carbon

dioxide

(CO

2

) and other so-called

greenhouse gases

into

the

atmosphere

. Especially important in this regard are the

use of

fossil fuels

such as

coal

, oil, and

natural gas

to

generate electricity, to heat spaces, and as a fuel for vehicles.

In addition, the disturbance of forests results in large emis-

sions of CO

2

into the atmosphere. This can be caused by

the conversion of forests into agricultural or urbanized land

uses, and also by the harvesting of timber.

During the past several centuries, human activities

have resulted in large emissions of CO

2

into the atmosphere,

causing substantial increases in the concentrations of that

gas. Prior to 1850 the atmospheric concentration of CO

2

was about 280 ppm, while in 1997 it was about 360 ppm.

Other greenhouse gases (these are also known as radiatively

active gases) have also increased in concentration during that

same period:

methane

(CH

4

) from about 0.7 ppm to 1.7

ppm,

nitrous oxide

(N

2

O) from 0.285 ppm to 0.304 ppm,

and

chlorofluorocarbons

(CFCs) from zero to 0.7 ppb.

Many climatologists and environmental scientists be-

lieve that the increased concentrations of radiatively active

gases are causing an increase in the intensity of Earth’s

greenhouse effect

. The resulting climatic warming could

result in important stresses for both natural ecosystems and

those that humans depend on for food and other purposes

(agriculture, forestry, and fisheries). Overall, CO

2

is esti-

mated to account for about 60% of the potential enhance-

ment of the greenhouse effect, while CH

4

accounts for 15%,

CFCs for 12%,

ozone

(O

3

) for 8%, and N

2

O for 5%.

Because an intensification of Earth’s greenhouse effect

is considered to represent a potentially important environ-

mental problem, planning and other actions are being under-

taken to reduce the emissions of radiatively active gases. The

most important strategy for reducing CO

2

emissions is to

lessen the use of fossil fuels. This will mostly be accomplished

by reducing energy needs through a variety of

conservation

measures, and by switching to non-fossil fuel sources. An-

other important means of decreasing CO

2

emissions is to

prevent or slow the rates of

deforestation

, particularly in

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Carbon offsets (CO2-emission offsets)

tropical countries. This strategy would help to maintain

organic

carbon

within ecosystems, by avoiding the emis-

sions of CO

2

through burning and

decomposition

that

occur when forests are disturbed or converted into other

land uses.

Unfortunately, fossil-fuel use and deforestation are

economically important activities in the modern world. This

circumstance makes it extremely difficult for society to rap-

idly achieve large reductions in the emissions of CO

2

.An

additional tactic that can contribute to net reductions of

CO

2

emissions involves so-called CO

2

offsets. This involves

the management of ecosystems to increase both the rate at

which they are fixing CO

2

into plant

biomass

and the total

quantity stored as organic carbon. This biological fixation

can offset some of the emissions of CO

2

and other green-

house gases through other activities.

Offsetting CO

2

emissions by planting trees

As plants grow, their rate of uptake of atmospheric

CO

2

through

photosynthesis

exceeds their release of that

gas by

respiration

. The net effect of these two physiological

processes is a reduction of CO

2

in the atmosphere. The

biological fixation of atmospheric CO

2

by growing plants

can be considered to offset emissions of CO

2

occurring

elsewhere—for example, as a result of deforestation or the

combustion

of fossil fuels.

The best way to offset CO

2

emissions in this way is

to manage ecosystems to increase the biomass of trees in

places where their density and productivity are suboptimal.

The carbon-storage benefits would be especially great if a

forest is established onto poorer-quality farmlands that are

no longer profitable to manage for agriculture (this process

is known as afforestation, or conversion into a forest). How-

ever, substantial increases in carbon storage can also be ob-

tained whenever the abundance and productivity of trees is

increased in “low-carbon ecosystems,” including urban and

residential areas.

Over the longer term, it is much better to increase

the amounts of organic carbon that are stored in terrestrial

ecosystems, especially in forests, than to just enhance the

rate of CO

2

fixation by plants. The distinction between the

amount stored and the rate of fixation is important. Fertile

ecosystems, such as marshes and most agroecosystems,

achieve high rates of net productivity, but they usually store

little biomass and therefore over the longer term cannot

sequester much atmospheric CO

2

. A less extreme example

involves second-growth forests and plantations, which have

higher rates of net productivity than do older-growth forests.

Averaged over the entire cycle of harvest and regeneration,

however, these more-productive forests store smaller quanti-

ties of organic carbon than do older-growth forests, particu-

larly in trees and large-dimension woody debris.

215

Both the greenhouse effect and emissions of CO

2

(and

other radiatively active gases) are global in their scale and

effects. For this reason, projects to gain CO

2

offsets can

potentially be undertaken anywhere on the planet, but tallied

as carbon credits for specific utilities or industrial sectors

elsewhere. For example, a fossil-fueled electrical utility in

the United States might choose to develop an afforestation

offset in a less-developed, tropical country. This might allow

the utility to realize significant economic advantages, mostly

because the costs of labor and land would be less and the

trees would grow quickly due to a relatively benign

climate

and long growing season. This strategy is known as a joint-

implementation project, and such projects are already under-

way. These involve United States or European electrical

utilities supporting afforestation in tropical countries as a

means of gaining carbon credits, along with other environ-

mental benefits associated with planting trees. Although this

is a valid approach to obtaining carbon offsets, it can be

controversial because some people would prefer to see indus-

tries develop forest-carbon offsets within the same country

where the CO

2

is being emitted.

Afforestation in rural areas

An estimated 5–8 billion acres (2–3 billion ha) of

deforested and degraded agricultural lands may be available

world-wide to be afforested. This change in

land use

would

allow enormous quantities of organic carbon to be stored,

while also achieving other environmental and economic ben-

efits. In North America, millions of acres of former agricul-

tural land have reverted to forest since about the 1930s,

particularly in the eastern states and provinces. There are

still extensive areas of economically marginal agricultural

lands that could be afforested in parts of North America

where the climate and soils are suitable for supporting forests.

Agricultural lands typically maintain about one-tenth

or less of the plant biomass of forests, while agricultural soils

typically contain 60–80% as much organic carbon as forest

soils. Because agricultural sites contain a relatively small

amount of organic carbon, reforestation of those lands has

a great potential for providing CO

2

offsets.

It is also possible to increase the amounts of carbon

stored in existing forests. This can be done by allowing

forests to develop into an old-growth condition, in which

carbon storage is relatively great because the trees are typi-

cally big, and there are large amounts of dead biomass present

in the surface litter, dead standing trees, and dead logs lying

on the forest floor. Once the old-growth condition is

reached, however, the

ecosystem

has little capability for

accumulating “additional” carbon. Nevertheless, old-growth

forests provide an important ecological service by tying up

so much carbon in their living and dead biomass. In this

sense, maintaining old-growth forests represents a strategy

of CO

2

-emissions deferral, because if those “high-carbon”

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Carbon offsets (CO2-emission offsets)

ecosystems were disturbed by timber harvesting or conver-

sion into another kind of land use, a result would be an

enormous

emission

of CO

2

into the atmosphere.

Dixon et al. (1993) examined carbon-offset projects

in various parts of the world, most of which involved affores-

tation of rural lands. The typical costs of the afforestation

projects were $1–10 per ton of carbon fixed. These are only

the costs associated with planting and initial tending of the

growing trees; there might also be additional expenses for

land acquisition and stand management and protection.

Of course, even while rural afforestation provides large

CO

2

-emission offsets, other important benefits are also pro-

vided. In some cases, the forests might be used to provide

economic benefits through the harvesting of timber (al-

though the resulting disturbance would lessen the carbon-

storage capability). Even if trees are not harvested from the

CO

2

-offset forests, it would be possible to hunt animals

such as deer, and to engage in other sorts of economically

valuable outdoor

recreation

. Increasing the area of forests

also provides many non-economic benefits, such as providing

additional

habitat

for native

species

, and enhancing ecolog-

ical services related to clean water and air,

erosion

control,

and climate moderation.

Urban forests

Urban forests consist of trees growing in the vicinity

of homes and other buildings, in areas where the dominant

character of land use is urban or suburban. Urban forests

may originate as trees that are spared when a forested area

is developed for residential land use, or they may develop

from saplings that are planted after homes are constructed.

Urban forests in older residential neighborhoods generally

have a relatively high density and extensive canopy cover of

trees. These characters are less well developed in younger

neighbourhoods and where land use involves larger buildings

used by institutions, business, or industry.

There are about 70 million acres (28-million ha) of

urban land in the United States. Its urban forest supports

an average density of 20 trees/acre (52 trees/ha), and has a

canopy cover of 28%. Nowak et al. (1994) estimated that

urban areas of the United States contain about 225 million

tree-planting opportunities, in which suboptimal tree densi-

ties could be subjected to fill-planting.

Urban forests achieve carbon offsets in two major ways.

First, as urban trees grow they sequester atmospheric CO

2

into their increasing biomass. The average carbon storage

in urban trees in the United States is about 13 tons per acre

(33 tonnes per ha). On a national basis that amounts to 0.8

billion tonnes of organic carbon, and an annual rate of uptake

of six million tonnes.

In addition, urban trees can offset some of seasonal

use of energy for cooling and heating the interior spaces of

buildings. Large, well-positioned trees provide a substantial

216

cooling influence through shading. Trees also cool the

ambi-

ent air

by evaporating water from their foliage (a process

known as

transpiration

). Trees also decrease wind speeds

near buildings. This results in decreased heating needs dur-

ing winter, because less indoor warmth is lost by the

infiltra-

tion

of outdoor air into buildings. Over most of North

America larger energy offsets associated with urban trees are

due to decreased costs of cooling than with decreased heating

costs. In both cases, however, much of the energy conserved

represents decreased CO

2

emissions through the combustion

of fossil fuels.

It is considerably more expensive to obtain CO

2

-offset

credits using urban trees than with rural trees. This difference

is mostly due to urban trees being much larger than rural

trees when planted, while also having larger maintenance

expenses. In the survey of Dixon et al. (1993), the typical

costs of rural CO

2

-offset projects were $1–10 per ton of

carbon fixed, compared with $15–30 per ton for urban trees.

Another study estimated the carbon savings associated

with planting 100-million trees in urban areas in the United

States (Nowak et al., 1994). In this case, the total CO

2

-

emission offsets were estimated to be 58.2 kg C per tree per

year (for trees at least ten years old). About 90% of the total

CO

2

offsets was associated with indirect savings of energy

for cooling and heating buildings, and 10% with carbon

sequestration into the growing biomass of the trees. The

estimated costs of the carbon offsets were $6.6–27.5 per ton

of carbon, but these costs would decrease considerably as

the trees grew larger. This study estimated that planting

trees in urban areas of the United States could potentially

offset as much as 2% of this country’s emissions of CO

2

.

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Nowak, D.J., E.G. McPherson, and R.A. Rowntree, eds. Chicago’s Urban

Forest Ecosystem. Results of The Chicago Urban Forest Climate Project. General

Technical Report NE-186, U.S.D.A. Forestry Service, Northeastern Forest

Experiment Station, Radnor, PA, 1994.

Trexler, M.C., and C. Haugen. Keeping It Green: Tropical Forestry Opportu-

nities for Mitigating Climate Change. Washington, D.C.: World Resources

Institute, 1995.

P

ERIODICALS

Dixon, R.K., et al. “Forest Sector Carbon Offset Projects: Near-term Op-

portunities To Mitigate Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” Water, Air, & Soil

Pollution 70 (1993): 561-577.

Freedman, B., and T. Keith “Planting Trees For Carbon Credits. A Discus-

sion Of Context, Issues, Feasibility, and Environmental Benefits, With

Particular Attention To Canada.” Environmental Review 4 (1996): 100-111.

Heisler, G.M. “Energy Savings With Trees.” Journal of Arboric 12 (1986):

113-125.

Kinsman, J.D., and M.C. Trexler. “Terrestrial Carbon Management And

Electric Utilities.” Water, Air, Soil Pollution 70 (1993): 545-560.