Environmental Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

International Primate Protection League

sustainable development since the Earth Summit in 1992.

IISD has produced two publications, Trade and Sustainable

Development and Guidelines for the Practical Assessment of

Progress Toward Sustainable Development.

[Carol Steinfeld]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

International Institute for Sustainable Development, 161 Portage Avenue

East, 6th Floor, Winnipeg, ManitobaCanada R3B 0Y4 (204) 958-7700,

Fax: (204) 958-7710, Email: info@iisd.ca, <http://www.iisd.org>

International Joint Commission

The International Joint Commission (IJC) is a permanent,

independent organization of the United States and Canada

formed to resolve trans-boundary ecological concerns.

Founded in 1912 as a result of provisions under the Boundary

Waters Treaty of 1909, the IJC was patterned after an earlier

organization, the Joint Commission, which was formed by

the United States and Britain.

The IJC consists of six commissioners, with three

appointed by the President of the United States, and three by

the Governor-in-Council of Canada, plus support personnel.

The commissioners and their organizations generally operate

freed from direct influence or instruction from their national

governments. The IJC is frequently cited as an excellent

model for international dispute resolution because of its

history of successfully and objectively dealing with

natural

resources

and environmental disputes between friendly

countries.

The major activities of the IJC have dealt with appor-

tioning, developing, conserving, and protecting the bina-

tional

water resources

of the United States and Canada.

Some other issues, including transboundary

air pollution

,

have also been addressed by the Commission.

The power of the IJC comes from its authority to

initiate scientific and socio-economic investigations, conduct

quasi-judicial inquiries, and arbitrate disputes.

Of special concern to the IJC have been issues related

to the

Great Lakes

. Since the early 1970s, IJC activities

have been substantially guided by provisions under the 1972

and 1978

Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement

plus

updated protocols. For example, it is widely acknowledged,

and well documented, that environmental quality and

eco-

system health

have been substantially degraded in the Great

Lakes. In 1985, the

Water Quality

Board of the IJC recom-

mended that states and provinces with Great Lakes bound-

aries make a collective commitment to address this commu-

nal problem, especially with respect to

pollution

. These

governments agreed to develop and implement remedial ac-

767

tion plans (RAPs) towards the restoration of

environmental

health

within their political jurisdictions. Forty-three areas

of concern have been identified on the basis of environmental

pollution, and each of these will be the focus of a remedial

action plan.

An important aspect of the design and intent of the

overall program, and of the individual RAPs, will be devel-

oping a process of integrated

ecosystem management

.

Ecosystem

management involves systematic, comprehensive

approaches toward the restoration and protection of environ-

mental quality. The ecosystem approach involves consider-

ation of interrelationships among land, air, and water, as

well as those between the inorganic

environment

and the

biota, including humans. The ecosystem approach would

replace the separate, more linear approaches that have tradi-

tionally been used to manage environmental problems. These

conventional attempts have included directed programs to

deal with particular resources such as fisheries, migratory

birds,

land use

, or point sources and area sources of toxic

emissions. Although these non-integrated methods have

been useful, they have been limited because they have failed

to account for important inter-relationships among environ-

mental management programs, and among components of

the ecosystem.

[Bill Freedman Ph.D.]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

International Joint Commission, 1250 23rd Street, NW, Suite 100,

Washington, D.C. USA 20440 (202) 736-9000, Fax: (202) 735-9015, ,

<http://www.ijc.org>

International Primate Protection

League

Founded in 1974 by Shirley McGreal, International Primate

Protection League (IPPL) is a global

conservation

organi-

zation that works to protect nonhuman primates, especially

monkeys and apes (

chimpanzees

, orangutans,

gibbons

,

and gorillas).

IPPL has 30,000 members, branches in the United

Kingdom, Germany, and

Australia

, and field representa-

tives in 31 countries. Its advisory board consists of scientists,

conservationists, and experts on primates, including the

world-renowned primatologist

Jane Goodall

, whose fa-

mous studies and books are considered the authoritative texts

on chimpanzees. Her studies have also heightened public

interest and sympathy for chimpanzees and other nonhuman

primates.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

International Register of Potentially Toxic Chemicals

IPPL runs a sanctuary and

rehabilitation

center at

its Summerville, South Carolina headquarters, which houses

two dozen gibbons and other abandoned, injured, or trauma-

tized primates who are refugees from medical laboratories

or abusive pet owners. IPPL concentrates on investigating

and fighting the multi-million dollar commercial trafficking

in primates for medical laboratories, the

pet trade

, and zoos,

much of which is illegal trade and smuggling of

endangered

species

protected by international law. IPPL is considered

the most active and effective group working to stem the

cruel and often lethal trade in primates.

IPPL’s work has helped to save the lives of literally

tens of thousands of monkeys and apes, many of which are

threatened or endangered

species

. For example, the group

was instrumental in persuading the governments of India

and Thailand to ban or restrict the export of monkeys, which

were being shipped by the thousands to research laboratories

and pet stores across the world.

The trade in primates is especially cruel and wasteful,

since a common way of capturing them is by shooting the

mother, which then enables poachers to capture the infant.

Many captured monkeys and apes die enroute to their desti-

nations, often being transported in sacks, crates, or hidden

in other devices.

IPPL often undertakes actions and projects that are

dangerous and require a good deal of skill. In 1992, its

investigations have led to the conviction of a Miami, Florida,

animal dealer for conspiring to help smuggle six baby orang-

utans captured in the jungles of Borneo. The endangered

orangutan

is protected by the Convention on International

Trade in Endangered Species of

Fauna

and Flora (CITES),

as well as by the United States

Endangered Species Act

.

In retaliation, the dealer unsuccessfully sued McGreal, as

did a multi-national corporation she once criticized for its

plan to capture chimpanzees and use them for hepatitis

research in Sierra Leone.

A more recent victory for IPPL occurred in April

2002. In 1997, Chicago O’Hare airport received two ship-

ments from Indonesia, each of which contained more than

250 illegally imported monkeys. Included in the shipments

were dozens of unweaned baby monkeys. After several years

of pursuing the issue, the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service

and

the U.S. Federal prosecutors charged the LABS Company (a

breeder of monkeys for research based in the United States)

and several of its employees, including its former president,

on eight felonies and four misdemeanors.

IPPL publishes IPPL News several times a year and

sends out periodic letters alerting members of events and

issues that affect primates.

[Lewis G. Regenstein]

768

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

International Primate Protection League, P.O. Box 766, Summerville, SC

USA 29484 (843) 871-2280, Fax: (843) 871-7988, Email: ippl@awod.com,

<http://ippl.org>

International Register of Potentially

Toxic Chemicals (U. N. Environment

Programme)

The International Register of Potentially Toxic

Chemicals

is published by the

United Nations Environment Pro-

gramme

(UNEP). Part of UNEP’s three-pronged

Earth-

watch

program, the register is an international inventory of

chemicals that threaten the

environment

. Along with the

Global Environment Monitoring System

and

INFOT-

ERRA

, the register monitors and measures environmental

problems worldwide. Information from the register is rou-

tinely shared with agencies in developing countries.

Third

World

countries have long been the toxic dumping grounds

for the world, and they still use many chemicals that have

been banned elsewhere. Environmental groups regularly

send information from the register to toxic chemical users

in developing countries as part of their effort to stop the

export of toxic

pollution

.

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

International Register of Potentially Toxic Chemicals, Chemin des

Ane

´

mones 15, Gene

`

ve, Switzerland CH-1219 +41-22-979 91 11, Fax:

+41-22-979 91 70, Email: chemicals@unep.ch

International Society for

Environmental Ethics

The International Society for

Environmental Ethics

(ISEE)

is an organization that seeks to educate people about the

environmental ethics and philosophy concerning

nature

.

An environmental ethic is the philosophy that humans have

a moral duty to sustain the natural

environment

and at-

tempts to answer how humans should treat other

species

(plant and animal), use Earth’s

natural resources

, and place

value on the aesthetic experiences of nature.

The society is an auxiliary organization of the Ameri-

can Philosophical Association, with about 700 members in

over 20 countries. Many of ISEE’s current members are

philosophers, teachers, or environmentalists. The ISEE offi-

cers include president Mark Sagoff (Institute for Philosophy

and Public Policy, University of Maryland) and John Baird

Callicott, vice president, (professor of philosophy at the Uni-

versity of North Texas). Two other key members are editors

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

International trade in toxic waste

of the ISEE newsletter, Jack Weir and

Holmes Rolston

,

III (Professor of Philosophy, Colorado State University).

All have contributed to the ongoing ISEE Master Environ-

mental Ethics Bibliography.

ISEE publishes a quarterly newsletter available to

members in print form and maintains an Internet site of

back issues. Of special note is the ISEE Bibliography, an

ongoing project that contains over 5,000 records from jour-

nals such as Environmental Ethics, Environmental Values,

and the Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics.

Another work in progress, the ISEE Syllabus Project,

continues to be developed by Callicott and Robert Hood,

doctoral candidate at Bowling Green State University. They

maintain a database of course offerings in environmental

philosophy and ethics, based on information from two-year

community colleges and four-year state universities, private

institutions, and master’s- and doctorate-granting universi-

ties. ISEE supports the enviroethics program which has

spurred many Internet discussion groups and is constantly

expanding into new areas of communication.

[Nicole Beatty]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

International Society for Environmental Ethics, Environmental Philosophy

Inc., Department of Philosophy, University of North Texas, P.O. Box

310980, Denton, TX USA 76203-0980, <http://www.cep.unt.edu/

ISEE.html>

International trade in toxic waste

Just as VCRs, cars, and laundry soap are traded across bor-

ders, so too is the waste that accompanies their production.

In the United States alone, industrial production accounts

for at least 500 million lb (230 million kg) of

hazardous

waste

a year. The industries of other developed nations also

produce waste. While some of it is disposed within national

borders, a portion is sent to other countries where costs are

cheaper and regulations less stringent than in the waste’s

country of origin.

Unlike consumer products, internationally traded haz-

ardous waste has begun to meet local opposition. In some

recent high-profile cases, barges filled with waste have trav-

eled the world looking for final resting places. In at least

one case, a ship may have dumped about ten tons of toxic

municipal incinerator ash in the ocean after being turned

away from dozens of ports. In recent years national and

international bodies have begun to voice official opposition

to this dangerous trade through bans and regulations.

The international trade in toxic wastes is, at bottom,

waste disposal with a foreign-relations twist. Typically a

769

manufacturing facility generates waste during the production

process. The facility manager pays a waste-hauling firm to

dispose of the waste. If the landfills in the country of origin

cost too much, or if there are no landfills that will take the

waste, the disposal firm will find a cheaper option, perhaps

a

landfill

in another country. In the United States, the

shipper must then notify the

Environmental Protection

Agency

(EPA), which then notifies the State Department.

After ascertaining that the destination country will indeed

accept the waste, American regulators approve the sale.

Disposing of the waste overseas in a landfill is only

the most obvious example of this international trade. Waste

haulers also sell their cargo as raw materials for

recycling

.

For example, used lead-acid batteries discarded by American

consumers are sent to Brazil where factory workers extract

and resmelt the

lead

. Though the lead-acid alone would

classify as hazardous, whole batteries do not. Waste haulers

can ship these batteries overseas without notification to Mex-

ico, Japan, and Canada, among other countries. In other

cases, waste haulers sell products, like DDT, that have been

banned in one country to buyers in another country that has

no ban. Whatever the strategy for disposal, waste haulers are

most commonly small, independent operators who provide a

service to waste producers in industrialized countries.

These haulers bring waste to other countries to take

advantage of cheaper disposal options and less stringent

regulatory climates. Some countries forbid the disposal of

the certain kinds of waste. Countries without such prohibi-

tions will import more waste. Cheap landfills depend on

cheap labor and land. Countries with an abundance of both

can become attractive destinations. Entrepreneurs or govern-

ment officials in countries, like Haiti, or regions within

countries, such as Wales, that lack a strong manufacturing

base, view waste disposal as a viable, inexpensive business.

Inhabitants may view it as the best way to make money and

create jobs. Simply by storing hazardous waste, the country

of Guinea-Bissau could have made $120 million, more

money than its annual budget.

Though the

less developed countries

(LDC) pre-

dictably receive large amounts of toxic waste, the bulk of

the international trade occurs between industrialized nations.

Canada and the United Kingdom in particular import large

volumes of toxic waste. Canada imports almost 85% of the

waste sent abroad by American firms, approximately 150,000

lb (70,000 kg) per year. The bulk of the waste ends up at

an incinerator in Ontario or a landfill in Quebec. Because

Canada’s disposal regulations are less strict than United

States laws, the operators of the landfill and incinerator can

charge lower fees than similar disposal sites in the United

States.

A waste hauler’s life becomes complicated when the

receiving country’s government or local activists discover that

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

International trade in toxic waste

the waste may endanger health and the

environment

. Local

regulators may step in and forbid the sale. This happened

many times in the case of the Khian Sea, a ship that had

contracted to dispose of Philadelphia’s incinerator ash. The

ship was turned away from Haiti, from Guinea-Bissau, from

Panama, and from Sri Lanka. For two years, beginning in

1986, the ship carried the toxic ash from port to port looking

for a home for its cargo before finally mysteriously losing

the ash somewhere in the Indian Ocean.

This early

resistance

to toxic-waste dumping has

since led to the negotiation of international treaties forbid-

ding or regulating the trade in toxic waste. In 1989, the

African, Caribbean, and Pacific countries (ACP) and the

countries belonging to the European Economic Community

(EEC) negotiated the Lome IV Convention, which bans

shipments of nuclear and hazardous waste from the EEC

to the ACP countries. ACP countries further agreed not to

import such waste from non-EEC countries. Environmen-

talists have encouraged the EEC to broaden its commitment

to limiting waste trade.

In the same year, under the auspices of the

United

Nations Environment Programme

(UNEP), the

Basel

Convention

on the Control of Transboundary Movements

of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal was negotiated.

This requires shippers to obtain government permission

from the destination country before sending waste to foreign

landfills or incinerators. Critics contend that Basel merely

formalizes the trade.

In 1991, the nations of the Organization of African

Unity negotiated another treaty restricting the international

waste trade. The Bamako Convention on the Ban of the

Import into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Move-

ment and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa

criminalized the import of all hazardous waste. Bamako

further forbade waste traders from importing to Africa mate-

rials that had been banned in one country to a country

that has no such ban. Bamako also radically redefined the

assessment of what constitutes a health hazard. Under the

treaty, all

chemicals

are considered hazardous until proven

otherwise.

These international strategies find their echoes in na-

tional law. Less developed countries have tended to follow

the Lome and Bamako examples. At least eighty-three Afri-

can, Latin-Caribbean, and Asian-Pacific countries have

banned hazardous waste imports. And the United States, in

a policy similar to the Basel Convention, requires hazardous

waste shipments to be authorized by the importing country’s

government.

The efforts to restrict toxic waste trade reflect, in

part, a desire to curb environmental inequity. When waste

flows from a richer country to a poorer country or region,

the inhabitants living near the incinerator, landfill, or

770

recycling facility are exposed to the dangers of toxic

compounds. For example, tests of workers in the Brazilian

lead resmelting operation found blood-lead levels several

times the United States standard. Lead was also found

in the water supply of a nearby farm after five cows died.

The loose regulations that keep prices low and attract

waste haulers mean that there are fewer safeguards for

local health and the environment. For example, leachate

from unlined landfills can contaminate local

groundwater

.

Jobs in the disposal industry tend to be lower paying than

jobs in manufacturing. The inhabitants of the receiving

country receive the wastes of industrialization without the

benefits.

Stopping the waste trade is a way to force manufac-

turers to change production processes. As long as cheap

disposal options exist, there is little incentive to change.

A waste-trade ban makes hazardous waste expensive to

discard, and will force business to search for ways to

reduce this cost.

Companies that want to reduce their hazardous waste

may opt for source reduction, which limits the hazardous

components in the production process. This can both

reduce production costs and increase output. A Monsanto

facility in Ohio saved more than $3 million dollars a year

while eliminating more than 17 million lb (8 million kg)

of waste. According to officials at the plant, average yield

increased by 8%. Measures forced by a lack of disposal

options can therefore benefit the corporate bottom line,

while reducing risks to health and the environment. See also

Environmental law; Environmental policy; Groundwater

pollution; Hazardous waste siting; Incineration; Industrial

waste treatment; Leaching; Ocean dumping; Radioactive

waste; Radioactive waste management; Smelter; Solid

waste; Solid waste incineration; Solid waste recycling and

recovery; Solid waste volume reduction; Storage and trans-

port of hazardous materials; Toxic substance; Waste man-

agement; Waste reduction

[Alair MacLean]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Dorfman, M., W. Muir, and C. Miller. Environmental Dividends: Cutting

More Chemical Waste. New York: INFORM, 1992.

Moyers, B. D. Global Dumping Ground: The International Traffic in Hazard-

ous Waste. Cabin John, MD: Seven Locks Press, 1990.

Vallette, J., and H. Spalding. The International Trade in Wastes: A Greenpeace

Inventory. Washington, DC: Greenpeace, 1990.

P

ERIODICALS

Chepesiuk, R. “From Ash to Cash: The International Trade in Toxic

Waste.” E Magazine 2 (July-August 1991): 30–37.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Intrinsic value

International Union for the

Conservation of Nature and Natural

Resources

see

IUCN—The World Conservation Union

International Voluntary Standards

International Voluntary Standards are industry guidelines

or agreements that provide technical specifications so that

products, processes, and services can be used worldwide. The

need for development of a set of international standards to

be followed and used consistently for environmental man-

agement systems was recognized in response to an increased

desire by the global community to improve environmental

management practices. In the early 1990s, the International

Organization for Standardization or ISO, which is located

in Geneva, Switzerland, began development of a strategic

plan to promote a common international approach to envi-

ronmental management. ISO 14000 is the title of a series

of voluntary international environmental standards that is

under development by ISO and is 142 member nations,

including the United States. Some of the standards devel-

oped by ISO include standardized sampling, testing and

analytical methods for use in the monitoring of environmen-

tal variables such as the quality of air, water and

soil

.

[Marie H. Bundy]

International Whaling Commission

see

International Convention for the

Regulation of Whaling (1946)

International Wildlife Coalition

The International

Wildlife

Coalition (IWC) was established

by a small group of individuals who came from a variety of

environmental and

animal rights

organizations in 1984.

Like many NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) that

arose in the 1970s and 1980s their initial work involved the

protection of

whales

. The IWC raised money for whale

conservation

programs on endangered Atlantic humpback

whale populations. This was one of the first

species

where

researchers identified individual animals through tail photo-

graphs. Using this technique the IWC developed what is

now a common tool, a whale adoption program based on

individual animals with human names.

From that basis, the fledgling group established itself

in an advocacy role with three principles in their mandate:

to prevent cruelty to wildlife, to prevent killing of wildlife,

and to prevent destruction of wildlife

habitat

. In light of

771

those principles, the IWC can be characterized as an ex-

tended animal rights organization. They maintain the “pre-

vention of cruelty” aspect common to humane societies,

perhaps the oldest progenitor of animal rights groups. In

standing by an ethic of preventing killing, they stand with

animal rights groups, but by protecting habitat they take a

more significant step by acting in a broad way to achieve

their initial two principles.

The program thus works at both ends of the spectrum,

undertaking

wildlife rehabilitation

and other programs

dealing with the individual animals, as well as lobbying and

promoting letter writing campaigns to improve wildlife legis-

lation. For example, they have used their Brazilian office to

create pressure to combat the international trade in exotic

pets, and their Canadian office to oppose the harp seal hunt

and the deterioration of Canada’s impending

endangered

species

legislation. Their United States-based operation has

built a reputation in the research field working with govern-

ment agencies to ensure that whale-watching on the eastern

seaboard does not harm the whales. Offices in the United

Kingdom are a focus for the IWC concern over the European

Community policies, such as lifting their ban on importing

fur from animals killed in leg hold traps.

It has become evident that the diversity within the

varied groups that constitute the environmental community

is a positive force, however, most conservation NGOs do

not cross the gulf between animal rights and habitat conser-

vation. A clear distinction exists between single animal ap-

proaches and broader conservation ideals, as they appeal

to different protection strategies, and potentially different

donors. Although the emotional appeal of releasing por-

poises from fishing nets alive outranks backroom lobbying

for changes in fishing regulations, the lobbying effort protect

more porpoises. The IWC may be deemed more successful

by exploiting a range of targets, or less so than a dedicated

advocacy group applying all its focus to one issue. They can

point to a growth from a modest 3,000 supporters in the

beginning, to over 100,000 people supporting the Interna-

tional Wildlife Coalition today.

[David Duffus]

R

ESOURCES

O

RGANIZATIONS

International Wildlife Coalition, 70 East Falmouth Highway, East

Falmouth, MA USA 02536 (508) 548-8328, Fax: (508) 548-8542, Email:

iwchq@iwc.org, <http://www.iwc.org>

Intrinsic value

Saying that an object has intrinsic value means that, even

though it has no specific use, market, or monetary value, it

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Introduced species

nevertheless can be valuable in and of itself and for its own

sake. The

Northern spotted owl

(Strix occidentalis caurina)

for example, has no instrumental or market value; it is not

a means to any human end, nor is it sold or traded in any

market. But, environmentalists argue, utility and price are

not the only measures of worth. Indeed, they say, some of

the things humans value most—truth, love, respect—are not

for sale at any price, and to try to put a price on them

would only tend to cheapen them. Such things have “intrinsic

value.”

Similarly, environmentalists say, the natural

environ-

ment

and its myriad life-forms are valuable in their own

right.

Wilderness

, for instance, has intrinsic value and is

worthy of protecting for its own sake. To say that something

has intrinsic value is not necessarily to deny that it may also

have instrumental value for humans and non-human animals

alike. Deer, for example, have intrinsic value; but they also

have instrumental value as a food source for

wolves

and

other predator

species

. See also Shadow pricing

Introduced species

Introduced

species

(also called invasive species) are those

that have been released by humans into an area to which

they are not native. These releases can occur accidently, from

places such as the cargo holds of ships. They can also occur

intentionally, and species have been introduced for a range of

ornamental and recreational uses, as well as for agricultural,

medicinal, and

pest

control purposes.

Introduced species can have dramatically unpredictable

effects on the

environment

and native species. Such effects

can include overabundance of the introduced species, com-

petitive displacement, and disease-caused

mortality

of the

native species. Numerous examples of adverse consequences

associated with the accidental release of species or the long

term effects of deliberately introduced species exist in the

United States and around the world. Introduced species can

be beneficial as long as they are carefully regulated. Almost

all the major varieties of grain and vegetables used in the

United States originated in other parts of the world. This

includes corn, rice, wheat, tomatoes, and potatoes.

The

kudzu

vine, which is native to Japan, was deliber-

ately introduced into the southern United States for

erosion

control and to shade and feed livestock. It is, however, an

extremely aggressive and fast-growing species, and it can

form continuous blankets of foliage that cover forested hill-

sides, resulting in malformed and dead trees. Other species

introduced as ornamentals have spread into the wild, displac-

ing or outcompeting native species. Several varieties of culti-

vated roses, such as the multiflora rose, are serious pests and

nuisance shrubs in field and pastures. The

purple loos-

772

estrife

, with its beautiful purple flowers, was originally

brought from Europe as a garden ornamental. It has spread

rapidly in freshwater

wetlands

in the northern United

States, displacing other plants such as cattails. This is viewed

with concern by ecologists and

wildlife

biologists since the

food value of loosestrife is minimal, while the roots and

starchy tubes of cattails are an important food source to

muskrats. Common ragweed was accidently introduced to

North America, and it is now a major health irritant for

many people.

Introduced species are sometimes so successful because

human activity has changed the conditions of a particular

environment. The Pine Barrens of southern New Jersey form

an

ecosystem

that is naturally acidic and low in nutrients.

Bogs in this area support a number of slow-growing plant

species that are adapted to these conditions, including peat

moss, sundews, and pitcher plants. But

urban runoff

, which

contain fertilizers, and

wastewater effluent

, which is high

in both

nitrogen

and

phosphorus

, have enriched the bogs;

the waters there have become less acidic and shown a gradual

elevation in the concentration of nutrients. These changes

in

aquatic chemistry

have resulted in changes in plant

species, and the acidophilus mosses and herbs are being

replaced by fast-growing plants that are not native to the

Pine Barrens.

Zebra mussels were transported by accident from Eu-

rope to the United States, and they are causing severe prob-

lems in the

Great Lakes

. They proliferate at a prodigious

rate, crowding out native species and clogging industrial

and municipal water-intake pipes. Many ecologists fear that

shipping traffic will transport the

zebra mussel

to harbors

all over the country. Scattered observations of this tiny crus-

tacean have already been made in the lower

Hudson River

in New York.

Although introduced species are usually regarded with

concern, they can occasionally be used to some benefit. The

water hyacinth

is an aquatic plant of tropical origin that

has become a serious clogging nuisance in lakes, streams,

and waterways in the southern United States. Numerous

methods of physical and chemical removal have been at-

tempted to eradicate or control it, but research has also

established that the plant can improve

water quality

. The

water hyacinth has proved useful in the withdrawal of nutri-

ents from sewage and other wastewater. Many constructed

wetlands, polishing ponds, and waste lagoons in waste treat-

ment plants now take advantage of this fact by routing

wastewater through floating beds of water hyacinth.

The reintroduction of native species is extremely diffi-

cult, and it is an endeavor that has had low rates of success.

Efforts by the

Fish and Wildlife Service

to reintroduce the

endangered

whooping crane

into native

habitat

in the

southwestern United States were initially unsuccessful be-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Ionizing radiation

cause of the fragility of the eggs, as well as the poor parenting

skills of birds raised in captivity. The service then devised

a strategy of allowing the more common sandhill crane to

incubate the eggs of captive whooping cranes in

wilderness

nests, and the fledglings were then taught survival skills by

their surrogate parents. Such projects, however, are extremely

time and labor intensive; they are also costly and difficult

to implement for large numbers of most species.

Due to the difficulties and expense required to protect

native species and to eradicate introduced species, there are

not many international laws and policies that seek to prevent

these problems before they begin. Thus customs agents at

ports and airports routinely check luggage and cargo for

live plant and animal materials to prevent the accidental

or deliberate transport of non-native species. Quarantine

policies are also designed to reduce the

probability

of

spreading introduced species, particularly diseases, from one

country to another.

There are similar concerns about genetically engi-

neered organisms, and many have argued that their creation

and release could have the same devastating environmental

consequences as some introduced species. For this reason,

the use of bioengineered organisms is highly regulated; both

the

Food and Drug Administration

and the

Environmen-

tal Protection Agency

(EPA) impose strict controls on the

field testing of bioengineered products, as well as on their

cultivation and use.

Conservation

policies for the protection of native spe-

cies are now focused on habitats and ecosystems rather than

single species. It is easier to prevent the encroachment of

introduced species by protecting an entire ecosystem from

disturbance, and this is increasingly well recognized both

inside and outside the conservation community. See also

Bioremediation; Endangered species; Fire ants; Gypsy moth;

Rabbits in Australia; Wildlife management

[Usha Vedagiri and Douglas Smith]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Common Weeds of the United States. United States Department of Agricul-

ture. New York: Dover Publications, 1971.

Forman, R. T. T., ed. Pine Barrens: Ecology and Landscape. New York:

Academic Press, 1979.

Inversion

see

Atmospheric inversion

773

Iodine 131

A radioactive

isotope

of the element iodine. During the

1950s and early 1960s, iodine-131 was considered a major

health hazard to humans. Along with cesium-137 and stron-

tium-90, it was one of the three most abundant isotopes

found in the fallout from the atmospheric testing of

nuclear

weapons

. These three isotopes settled to the earth’s surface

and were ingested by cows, ultimately affecting humans by

way of dairy products. In the human body, iodine-131, like

all forms of that element, tends to concentrate in the thyroid,

where it may cause

cancer

and other health disorders. The

Chernobyl nuclear reactor explosion is known to have re-

leased large quantities of iodine-131 into the

atmosphere

.

See also Radioactivity

Ion

Forms of ordinary chemical elements that have gained or

lost electrons from their orbit around the atomic nucleus

and, thus, have become electrically charged. Positive ions

(those that have lost electrons) are called cations because

when charged electrodes are placed in a solution containing

ions the positive ions migrate to the cathode (negative elec-

trode). Negative ions (those that have gained extra electrons)

are called anions because they migrate toward the anode

(positive electrode). Environmentally important cations in-

clude the

hydrogen

ion (H

+

) and dissolved metals. Impor-

tant anions include the hydroxyl ion (OH

-

) as well as many

of the dissolved ions of nonmetallic elements. See also Ion

exchange; Ionizing radiation

Ion exchange

The process of replacing one

ion

that is attached to a charged

surface with another. A very important type of ion exchange

is the exchange of cations bound to

soil

particles. Soil

clay

minerals

and organic matter both have negative surface

charges that bind cations. In a fertile soil the predominant

exchangeable cations are Ca

2+

,Mg

2+

and K

+

.In

acid

soils

Al

3+

and H

+

are also important exchangeable ions. When

materials containing cations are added to soil, cations

leach-

ing

through the soil are retarded by cation exchange.

Ionizing radiation

High-energy radiation with penetrating competence such as

x rays and gamma rays which induces ionization in living

material. Molecules are bound together with covalent bonds,

and generally an even number of electrons binds the atoms

together. However, high-energy penetrating radiation can

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Iron minerals

fragment molecules resulting in atoms with unpaired elec-

trons known as “free radicals.” The ionized “free radicals”

are exceptionally reactive, and their interaction with the

macromolecules (DNA, RNA, and proteins) of living cells

can, with high dosage, lead to cell death. Cell damage (or

death) is a function of penetration ability, the kind of cell

exposed, the length of exposure, and the total dose of ioniz-

ing radiation. Cells that are mitotically active and have a high

oxygen content are most vulnerable to ionizing radiation. See

also Radiation exposure; Radiation sickness; Radioactivity

Iron minerals

The oxides and hydroxides of ferric iron (Fe(III)) are very

important minerals in many soils, and are important sus-

pended solids in some fresh water systems. Important oxides

and hydroxides of iron include goethite, hematite, lepido-

crocite, and ferrihydrite.

These minerals tend to be very finely divided and can

be found in the clay-sized fraction of soils, and like other

clay-sized minerals, are important adsorbers of ions. At high

pH

they adsorb hydroxide (OH

-

) ions creating negatively

charged surfaces that contribute to cation exchange surfaces.

At low pH they adsorb

hydrogen

(H

+

) ions, creating anion

exchange surfaces. In the pH range between 8 and 9 the

surfaces have little or no charge. Iron hydroxide and oxide

surfaces strongly adsorb some environmentally important

anions, such as phosphate, arsenate and selanite, and cations

like

copper

,

lead

, manganese and chromium. These ions

are not exchangeable, and in environments where iron oxides

and hydroxides are abundant, surface

adsorption

can con-

trol the mobility of these strongly adsorbed ions.

The hydroxides and oxides of iron are found in the

greatest abundance in older highly weathered landscapes.

These minerals are very insoluble and during

soil weather-

ing

they form from the iron that is released from the structure

of the soil-forming minerals. Thus, iron oxide and hydroxide

minerals tend to be most abundant in old landscapes that

have not been affected by

glaciation

, and in landscapes

where the rainfall is high and the rate of soil mineral weather-

ing is high. These minerals give the characteristic red (hema-

tite or ferrihydrite) or yellow-brown (goethite) colors to soils

that are common in the tropics and subtropics. See also

Arsenic; Erosion; Ion exchange; Phosphorus; Soil profile;

Soil texture

Irradiation of food

see

Food irradiation

774

Irrigation

Irrigation is the method of supplying water to land to support

plant growth. This technology has had a powerful role in

the history of civilization. In

arid

regions sunshine is plenti-

ful and

soil

is usually fertile, so irrigation supplies the critical

factor needed for plant growth. Yields have been high, but

not without costs. Historic problems include

salinization

and water

logging

; contemporary difficulties include im-

mense costs, spread of water-borne diseases, and degraded

aquatic environments.

One geographer described California’s Sierra Nevada

as the “mother nurse of the San Joaquin Valley.” Its heavy

winter snowpack provides abundant and extended

runoff

for the rich valley soils below. Numerous irrigation districts,

formed to build diversion and storage

dams

, supply water

through gravity-fed canals. The snow melt is low in

nutrients, so salinization problems are minimal. Wealth

from the lush fruit orchards has enriched the state.

By contrast, the

Colorado River

, like the Nile, flows

mainly through arid lands. Deeply incised in places, the

river is also limited for irrigation by the high salt content

of

desert

tributaries. Still, demand for water exceeds

supply. Water crossing the border into Mexico is so saline

that the federal government has built a

desalinization

plant at Yuma, Arizona. Colorado River water is imperative

to the Imperial Valley, which specializes in winter produce

in the rich, delta soils. To reduce salinization problems,

one-fifth of the water used must be drained off into the

growing Salton Sea.

Salinization and water logging have long plagued the

Tigris, Euphrates, and Indus River flood plains. Once fertile

areas of Iraq and Pakistan are covered with salt crystals. Half

of the irrigated land in our western states is threatened by

salt buildup.

Some of the worst problems are degraded aquatic envi-

ronments. The

Aswan High Dam

in Egypt has greatly

amplified surface evaporation, reduced nutrients to the land

and to fisheries in the delta, and has contributed to the spread

of

schistosomiasis

via water snails in irrigation ditches.

Diversion of

drainage

away from the

Aral Sea

for cotton

irrigation has severely lowered the shoreline, and threatens

this water body with ecological disaster.

Spray irrigation in the High Plains is lowering the

Ogallala Aquifer’s

water table

, raising pumping costs. Kes-

terson Marsh in the San Joaquin Valley has become a hazard

to

wildlife

because of selenium

poisoning

from irrigation

drainage. The federal

Bureau of Reclamation

has invested

huge sums in dams and reservoirs in western states. Some

question the wisdom of such investments, given the past

century of farm surpluses, and argue that water users are not

paying the true cost.

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Island biogeography

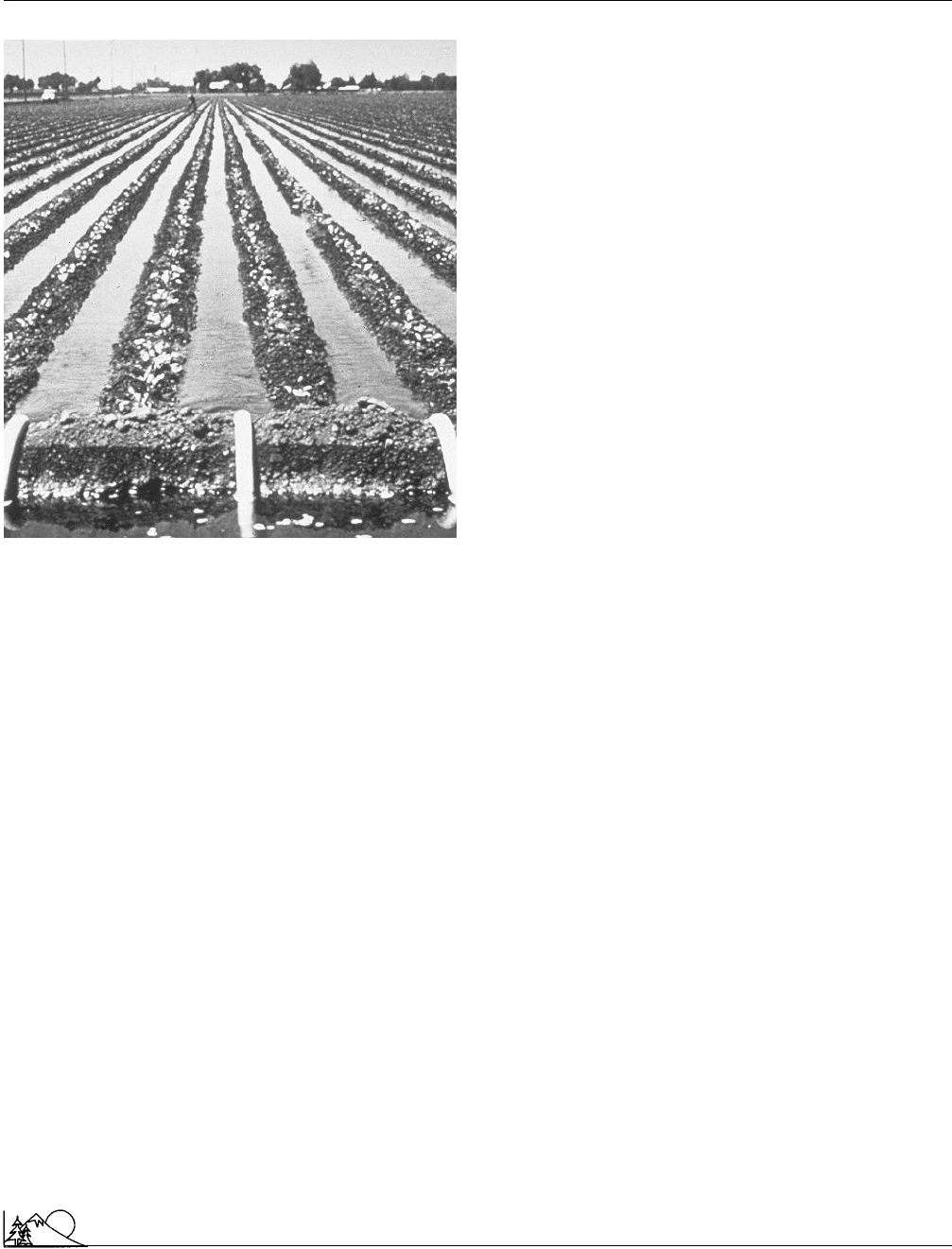

A farm irrigation system. (U. S. Geological Survey

Reproduced by permission.)

Irrigation still offers great potential, but only if used

with wisdom and understanding. New technologies may yet

contribute to the world’s ever-increasing need for food. See

also Climate; Commercial fishing; Reclamation

[Nathan H. Meleen]

R

ESOURCES

B

OOKS

Huffman, R. E. Irrigation Development and Public Water Policy. New York:

Ronald Press, 1953.

Powell, J. W. “The Reclamation Idea.” In American Environmentalism:

Readings in Conservation History. 3rd ed., edited by R. F. Nash. New York:

McGraw-Hill, 1990.

Wittfogel, K. A. “The Hydraulic Civilizations.” In Man’s Role in Changing

the Face of the Earth, edited by W. L. Thomas Jr. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1956.

Zimmerman, J. D. Irrigation. New York: Wiley, 1966.

O

THER

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Water: 1955 Yearbook of Agriculture. Wash-

ington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1955.

Island biogeography

Island

biogeography

is the study of past and present animal

and plant distribution patterns on islands and the processes

775

that created those distribution patterns. Historically, island

biogeographers mainly studied geographic islands—conti-

nental islands close to shore in shallow water and oceanic

islands of the deep sea. In the last several decades, however,

the study and principles of island biogeography have been

extended to ecological islands such as forests and

prairie

fragments isolated by human development. Biogeographic

“islands” may also include ecosystems isolated on mountain-

tops and landlocked bodies of water such as Lake Malawi

in the African Rift Valley. Geographic islands, however,

remain the main laboratories for developing and testing the

theories and methods of island biogeography.

Equilibrium theory

Until the 1960s, biogeographers thought of islands as

living museums—relict (persistent remnant of an otherwise

extinct

species

of plant or animal) scraps of mainland eco-

systems in which little changed—or closed systems mainly

driven by

evolution

. That view began to radically change

in 1967 when Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson

published The Theory of Island Biogeography.

In their book, MacArthur and Wilson detail the equi-

librium theory of island biogeography—a theory that became

the new paradigm of the field. The authors proposed that

island ecosystems exist in dynamic equilibrium, with a steady

turnover of species. Larger islands—as well as islands closest

to a source of immigrants—accommodate the most species

in the equilibrium condition, according to their theory. Mac-

Arthur and Wilson also worked out mathematical models

to demonstrate and predict how island area and isolation

dictate the number of species that exist in equilibrium.

Dispersion

The driving force behind species distribution is disper-

sion—the means by which plants and animals actively leave

or are passively transported from their source area. An island

ecosystem

can have more than one source of colonization,

but nearer sources dominate. How readily plants or animals

disperse is one of the main reasons equilibrium will vary

from species to species.

Birds and

bats

are obvious candidates for anemochory

(dispersal by air), but some species normally not associated

with flight are also thought to reach islands during storms

or even normal wind currents. Orchids, for example, have

hollow seeds that remain airborne for hundreds of kilome-

ters. Some small spiders, along with other insects like bark

lice, aphids, and ants (collectively knows as aerial

plankton

)

often are among the first pioneers of newly formed islands.

Whether actively swimming or passively floating on

logs or other debris, dispersal by sea is called thallasochory.

Crocodiles

have been found on Pacific islands 600 miles

(950 km) from their source areas, but most amphibians,

larger terrestrial reptiles, and, in particular, mammals, have

difficulty crossing even narrow bodies of water. Thus, thalla-

Environmental Encyclopedia 3

Island biogeography

sochory is the medium of dispersal primarily for fish, plants,

and insects. Only small vertebrates such as lizards and snakes

are thought to arrive at islands by sea on a regular basis.

Zoochory is transport either on or inside an animal.

This method is primarily a means of plant dispersal, mostly

by birds. Seeds ride along either stuck to feathers or survive

passage through a bird’s digestive tract and are deposited in

new territory.

Anthropochory is dispersal by human beings. Al-

though humans intentionally introduce domestic animals to

islands, they also bring unintended invaders, such as rats.

Getting to islands is just the first step, however. Plants

and animals often arrive to find harsh and alien conditions.

They may not find suitable habitats. Food chains they de-

pend on might be missing. Even if they manage to gain a

foothold, their limited numbers make them more susceptible

to

extinction

. Chances of success are better for highly adapt-

able species and those that are widely distributed beyond the

island. Wide distribution increases the likelihood a species on

the verge of extinction may be saved by the rescue effect,

the replenishing of a declining population by another wave

of immigration.

Challenging established theories

Many biogeographers point out that isolated ecosys-

tems are more than just collections of species that can make

it to islands and survive the conditions they encounter there.

Several other contemporary theories of island biogeography

build on MacArthur and Wilson’s theory; other theories

contradict it.

Equilibrium theory suggests that species turnover is

constant and regular. Evidence collected so far indicates

MacArthur and Wilson’s model works well in describing

communities of rapid dispersers who have a regular turnover,

such as insects, birds, and fish. However, this model may

not apply to species who disperse more slowly.

Proponents of historical legacy models argue that com-

munities of larger animals and plants (forest trees, for exam-

ple) take so long to colonize islands that changes in their

populations probably reflect sudden climactic or geological

upheaval rather than a steady turnover. Other theories sug-

gest that equilibrium may not be dynamic, that there is little

or no turnover. Through

competition

, established species

keep out new colonists; the newcomers might occupy the

same ecological niches as their predecessors. Established

species may also evolve and adapt to close off those niches.

Island resources and habitats may also be distinct enough

to limit immigration to only a few well-adapted species.

Thus, in these later models, dispersal and colonization

are not nearly as random as in MacArthur and Wilson’s

model. These less random, more deterministic theories of

island ecosystems conform to specific assembly rules—a

776

complex list of factors accounting for the species present

in the source areas, the niches available on islands, and

competition between species.

Some biogeographers suggest that every island—and

perhaps every

habitat

on an island—may require its own

unique model. Human disruption of island ecosystems fur-

ther clouds the theoretical picture. Not only are habitats

permanently altered or lost by human intrusion, but anthro-

pochory also reduces an island’s isolation. Thus, finding

relatively undisturbed islands to test different theories can

be difficult.

Since the time of naturalists Charles Darwin and his

colleague, Alfred Wallace, islands have been ideal “natural

laboratories” for studying evolution. Patterns of evolution

stand out on islands for two reasons: island ecosystems tend

to be simpler than other geographical regions, and they

contain greater numbers of

endemic species

, plant, and

animal species occurring only in a particular location.

Many island endemics are the result of adaptive radia-

tion—the evolution of new species from a single lineage for

thepurpose of filling unoccupied ecologicalniches. Many spe-

cies from mainland source areas simply never make it to

islands, so species that can immigrate find empty ecological

niches where once theyfaced competition. For example, mon-

itor lizards immigrating to several small islands in Indonesia

found the

niche

for large predators empty. Monitors on these

islands evolved into Komodo Dragons, filling the niche.

Conservation of biodiversity

Theories of island biogeography also have potential

applications in the field of

conservation

. Many conserva-

tionists argue that as human activity such as

logging

and

ranching encroach on wild lands, remaining parks and re-

serves begin to resemble small, isolated islands. According

to equilibrium theory, as those patches of wild land grow

smaller, they support fewer species of plants and animals.

Some conservationists fear that plant and animal populations

in those parks and reserves will sink below minimum viable

population levels—the smallest number of individuals neces-

sary to allow the species to continue reproducing. These

conservationists suggest that one way to bolster populations

is to set aside larger areas and to limit species isolation by

connecting parks and preserves with

wildlife

corridors.

Islands with greatest variety of habitats support the

most species; diverse habitats promotes successful dispersal,

survival, and reproduction. Thus, in attempting to preserve

island

biodiversity

, conservationists focus on several factors:

the size (the larger the island, the more habitats it contains),

climate

, geology (

soil

that promotes or restricts habitats),

and age of the island (sparse or rich habitats). All of these

factors must be addressed to ensure island biodiversity.

[Darrin Gunkel]