Fowler A. Mathematical Geoscience

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

520 8 Mantle Convection

strain are proportional to increments of stress, with the factor of proportionality

being such that the yield stress is not exceeded. What this means is that the plastic

deformation is also effectively viscous, but with an effective viscosity which must

be computed as part of the solution.

At the plastic–viscous transition boundary, the viscosity is denoted by η

q

, and is

given by the viscous formula, in terms of the stress and temperature there. What we

then find is that the effective viscosity throughout the plastic lid is approximately

equal to η

q

. For example, if we consider the Newtonian rheology with n =1, so that

(8.176) gives the dimensionless viscosity

η =exp

1 −T

εT

, (8.290)

then, using the linear temperature (8.198), we have

η

q

≈exp

(1 −T

0

)

1 −

q

s

ε

T

0

+(1 −T

0

)

q

s

. (8.291)

This gives the dimensionless viscosity in the plastic lid, and is also the ratio of the

dimensional viscosity to that in the asthenosphere. The effective plastic viscosity

of the lid is very large, but drops abruptly to values near one when the ratio q/s

approaches one. Thus if q reaches s, the lithospheric column at that point has an

effective reduced viscosity equal to that of the underlying asthenosphere. Conse-

quently, the heavy lithosphere will convectively sink into the underlying mantle.

This initiates the process of subduction.

It is possible to calculate the variation of s and q with distance x. We calculate s

using (8.243). With n =1, and supposing that s =0atx =0, we find

s =k(1 −T

0

)

4/5

x

2/5

, (8.292)

where

k =

25B

1

6

1/5

≈0.82. (8.293)

Calculation of q requires solution for the plastic stresses in the lid, but a simple

approximation which is quite accurate is

q ≈

(1 −T

0

)

13/5

k

2

12c

x

4/5

, (8.294)

where

c =

ε

2

d

2

τ

c

η

0

κRa

3/5

, (8.295)

and τ

c

is the yield stress.

We can see from this that q/s is an increasing function of x, so that failure will

occur at the right hand side of the convecting cell x = 1ifq ≥ s there, and thus

8.7 Tectonics on Venus 521

if c<c

∗

, where the approximation (8.294) would suggest c

∗

≈ 0.046. Accurate

numerical determination of q in fact shows that c

∗

≈0.056. The failure criterion is

thus

τ

c

<

∼

τ

∗

=

c

∗

η

0

κRa

3/5

ε

2

d

2

. (8.296)

If we use the values c

∗

= 0.056, η

0

= 1.4 × 10

20

Pa s, κ = 10

−6

m

2

s

−1

, Ra =

3 × 10

8

, ε = 0.023, d = 3000 km, then we find τ

∗

≈ 2 kbar. Although this esti-

mate would change for a more realistic value of n =3.5, it indicates that for appar-

ent yield stresses of the order of 300 bar, lithospheric failure will indeed occur. In

principle, this provides a satisfactory dynamical explanation for the occurrence of

subduction, and thus active plate tectonics, on the Earth.

8.7 Tectonics on Venus

Venus is a planet which is very similar to the Earth in many respects. Its sulphurous,

carbon rich atmosphere is very different of course, causing the hot surface tempera-

ture of 750 K, but the planet is of a similar size, and is generally presumed to have a

similar structure, with a silicate mantle sheathing an iron core. It is a tectonically ac-

tive planet, with many different kinds of large scale surface features: tesserae, wrin-

kle ridges, chasmatae, coronae. There is much evidence of past volcanism. From this

we can infer that there is (unsurprisingly) active mantle convection on Venus. But

there is no active plate tectonics. There is no system of linear ridges and subduction

zones which indicates that the lithosphere takes part in mantle convection.

This might seem perplexing at first, but armed with our new understanding of

how convection works in temperature-dependent viscous fluids, the explanation is

apparently simple. Mantle convection on Venus operates below a stagnant lid, in

just the same way as it presumably does on Mars (another volcanic planet with no

plate tectonics), and the stresses generated are simply not large enough to cause

lithospheric failure and hence subduction. One contributing factor in the difference

between the planets might be the absence of water, which has a weakening effect on

the rheology.

There is, however, another twist to this story. The surface of Venus, if it is stag-

nant, should be as old as the planet, presumably some 4 billion years. However,

counts of meteor craters indicate that in fact the planetary surface is of a uniform

age of some 500 million years. Old, but significantly younger than might be ex-

pected. How can this be?

The most obvious answer is that the planet was resurfaced 500 million years ago

in a global resurfacing event, caused by a transient major plate tectonic subduc-

tion event on a planetary scale. Such a hypothetical event is not inconsistent with

what we know about convection at high Rayleigh number. In fact, as the Rayleigh

number increases, convection becomes oscillatory and increasingly intermittent. In

a vivid picture developed by Lou Howard, convection in such oscillatory régimes

consists alternatively of long tranquil periods, where stagnant conductive boundary

522 8 Mantle Convection

layers grow at the base and the surface, and violent overturning events, where these

unstable boundary layers rapidly detach and mix the flow.

Could this happen in a planetary mantle? To imagine how, suppose that an over-

turning event occurs, in which the lithosphere fails, leading to massive subduction

and the resurfacing of the entire planetary mantle. The previous cold lithosphere

sinks to the base of the mantle, where it forms a cold dense layer. Without any

convectively induced stresses to make it plastic, it is stagnant. At the core–mantle

boundary, a hot, low viscosity thermal boundary layer grows, but is unable to pen-

etrate the stagnant slab above. This will continue, either until the thermal boundary

layer penetrates through the slab, or until the buoyant stresses it generates cause

plastic failure of the cold barrier above it. But eventually the thermal boundary layer

will break through, causing massive thermal plumes to rise through the mantle to the

surface, where they will impinge at the base of the newly forming lithosphere, which

in the meantime has been growing conductively downwards from the surface of the

planet.

It should be noted that the plastic failure of the lithosphere which we have dis-

cussed above relies on an underlying convective flow, which causes the variation in

lid thickness, which in turn causes the horizontal temperature variations which are

the origin of the stresses in the lid. After an overturn, however, interior convection

is weak, and horizontal lid thickness variation will not be induced until the massive

plumes arrive at the base of the lid.

The arrival of one of these plumes beneath the newly formed lithosphere will

cause uplift and thermal erosion at its centre, and a radial outflow. Thus the situ-

ation is similar to that analysed in Sect. 8.6, with the difference that the flow in

the delamination layer is radial, and there is essentially no flow in the interior. This

latter feature makes little difference, since our analysis of the developing lid and

delamination layer is essentially uncoupled from the underlying mantle flow.

The analysis of the model thus proceeds similarly to that already presented, ex-

cept that the temperature in the lid depends on time. In the same dimensionless

variables as before, T in the lid satisfies

T

t

=T

zz

,

T =T

0

on z =0,

T =1,T

z

=Γ on z =s.

(8.297)

The temperature gradient at the base of the lid Γ is now unknown, but it serves to

determine the position of the base s through the equation

ω

3

rs

Γ

3

s

Γ

n−1

=B

n

rΓ, (8.298)

where s

=

∂s

∂r

; this is the equivalent in polar coordinates of (8.238); note that we

allow n =1 in this analysis. The coefficient ω

3

is introduced here because a slightly

different choice of viscosity scale has been used; see Question 8.9, which indicates

the connection between the two choices. Essentially, the choice of ν in the steady

8.7 Tectonics on Venus 523

state is dictated by interior flow driven by the plume stress; in the present case, this

is less relevant.

Solution of (8.297) and (8.298) provides T and s, and then it can be shown that

the plastic lid base q satisfies

2

r

1/2

q

=−

r

1/2

C

s

0

zT

r

dz, (8.299)

where q

=

∂q

∂r

and

C =

τ

c

αρ

a

gT

a

νd

. (8.300)

As before, failure occurs if q reaches s. In fact, this is a little glib when n =1, since

the effective viscosity at the lid base depends also on the stress. Taking this into

account suggests that failure will occur when

q

s

≈

1 −T

0

T

c

−T

0

, (8.301)

where

T

c

≈

1

1 +2(n −1)ε ln(1/ε)

. (8.302)

Values appropriate to Venus suggest failure then occurs when

q

s

≈0.41.

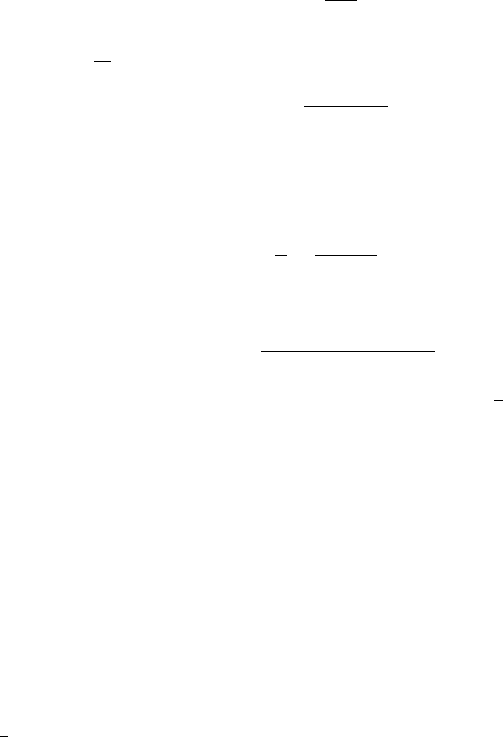

Numerical solution of the complicated free boundary problem (8.297) and

(8.298) indicates that failure first occurs at a time t

f

at a radial distance r

f

, where

these values depend explicitly but complicatedly on the parameters of the problem,

which are, however, essentially known. The two main uncertainties are the value

of the yield stress τ

c

and the asthenospheric temperature T

a

. Figure 8.9 shows the

result of the calculation yielding the time of failure t

f

and radial position of failure

r

f

as functions of τ

c

for two plausible values T

a

= 1500 K and T

a

= 1700 K. We

see that for a failure time of 500 Ma (million years), the shear stress would be about

160 bars, and the corresponding failure distance is between 200 and 800 km. This

value of the yield stress is about half what one might expect on the Earth.

A notable feature of the solutions is the variation of the plastic effective viscosity

η

q

with radial distance. Computation of this shows that at the point of failure, η

q

drops precipitately to the asthenospheric value when the radial distance is about

1

2

r

f

, and remains close to this (within a factor of ten) thereafter. This suggests that

at the time of failure, there will be a central lithospheric plug of essentially rigid

material, surrounded by a uniformly failing concentric exterior.

Coronae on Venus are quasi-circular uplift features having typical radii in the

range 100–300 km. They consist of a central domed plateau bounded by an escarp-

ment which descends into a trench. These trenches have the topographic and gravity

signatures of oceanic subduction trenches on the Earth, while it is thought that the

coronae themselves are the consequence of the impingement of mantle plumes on

the Venusian lithosphere. We thus see that the inferred nature of coronae is exactly

524 8 Mantle Convection

Fig. 8.9 Variation of (a) time of yield t

f

and (b) radial location of failure r

f

with yield stress,

for values of T

a

= 1500 K and T

a

= 1700 K, with other parameters as appropriate for Venus; in

particular, the rheological exponent is n =3.5 and the surface temperature is 750 K

that associated with the beginning of subduction via the mechanism described here.

Moreover, the time scale and failure radius are what one would expect, provided the

long term effective yield stress for Venusian mantle rocks is of the order of 150 bars.

8.8 Notes and References

Mantle convection is described in a number of books, such as those by Davies

(1999), Schubert et al. (2001) and Bercovici (2009a). The first of these tells the

story, and treads lightly through the mush of equations which besets the presenta-

tion here. The second is much more theoretically inclined, while the third (part of

the series known as the Treatise on geophysics) is a recent and up-to-date compre-

hensive summary of the current state of the art.

Low Rayleigh Number Convection Rayleigh–Bénard convection was described

experimentally by Bénard in 1900 and 1901, although it later transpired that his ex-

perimental results were actually due to Marangoni convection (Pearson 1958), and

the phenomenon of convection had been described earlier by Thomson in 1882 and

Count Rumford in 1797 (see Chandrasekhar 1981, which, apart from its description

of the theory, also contains a useful historical summary; a more thorough historical

review is given by Bercovici 2009b). The mechanism of instability was described by

Rayleigh (1916). The nonlinear amplitude equation was first described by Malkus

and Veronis (1958), thus ushering in one of the major areas of exploration for ap-

plied mathematicians in the 1960s and 1970s, the study of nonlinear stability, Hopf

bifurcations, and their progeny of phase chaos, weak turbulence, and the like. The

Ginzburg–Landau equation was derived in the context of convection by Newell and

8.8 Notes and References 525

Whitehead (1969) and Segel (1969). Later expositions are given by Balmforth et al.

(2001) and Ribe (2009); Eq. (8.130) takes the same form (A is defined slightly dif-

ferently), but differing versions of the diffusion coefficient are reported. The value

here (4) is the same as that given by Newell and Whitehead (at infinite Prandtl num-

ber).

The leading figure in the analysis of finite amplitude convection and its bifurca-

tion in the vicinity of its onset is Fritz Busse; a summary of his results dating back

to 1965 is in his review (Busse 1985).

The Theory of Continental Drift Wegener’s book on continental drift, The ori-

gin of continents and oceans, was published in German in 1915, and went through

four editions, the last published in 1929, a year before his premature death during an

expedition on the Greenland ice sheet (McCoy 2006). The third edition was trans-

lated into French, English, Russian, Swedish and Spanish, and the fourth edition was

translated into English and published by Dover in 1966, and for English-speaking

audiences this is the most accessible version (Wegener 1966). Wegener was not the

only scientist who proposed continental drift, for example the American scientist

F.B. Taylor also proposed a version.

Wegener propounded his thesis by weight of observations, but lacked a credible

mechanism. The hypothesis that convection could be this mechanism was largely

due to Arthur Holmes, who proposed it as an explanation in a series of papers in the

1920s and 1930s. His thesis is summarised in his book, Principles of physical geol-

ogy, whose first edition appeared in 1944, in the midst of the period of geological

unbelief; the second edition appeared in 1965, when the plate tectonic revolution

had occurred. The third edition, edited and revised by his widow Doris Reynolds,

was published in 1978 (Holmes 1978). As mentioned in the preface, this book sur-

veys almost the whole field of geoscience.

The mystery remains, why did Wegener’s hypothesis and Holmes’s theory not

gain acceptance until the 1960s, and even then (and now), geophysicists still draw

a screen over their predecessors’ failings, suggesting that proper geophysical evi-

dence did not appear until the sea floor palaeomagnetism studies of the 1960s, as

if all the evidence that Wegener had accumulated was not good enough. The study

of this denial is an interesting subject in itself for the history and philosophy of sci-

ence, similar in many ways to the Copernican revolution (Koestler 1964), the tran-

sition from scriptural science to geology at the beginning of the nineteenth century

(Winchester 2001; Cadbury 2000), and many other past and ongoing controversies,

mentioned elsewhere in these pages. Two particular books detailing the acceptance

of plate tectonics in a historical context are those by Le Grand (1988) and Oreskes

(1999). Sub-controversies within the study of mantle convection include the impor-

tance of radioactive heating, the nature of the plate-driving forces, and the plume

hypothesis. At least some of the disagreements concerning these latter topics arise

implicitly through misunderstanding of the way in which mathematical models of

the processes should be interpreted.

526 8 Mantle Convection

High Rayleigh Number Convection The study of boundary layer convection as

R →∞was initiated by Pillow (1952), and in the geophysical context in a semi-

nal paper by Turcotte and Oxburgh (1967). Other early analyses were by Robinson

(1967) and Wesseling (1969). There was some disagreement between these various

results, and it awaited the comprehensive papers of Roberts (1977, 1979) to essen-

tially resolve the differences. Roberts’s 1979 paper is analytically correct, except in

one point which we mentioned before, but his work has been criticised for numerical

inaccuracy by Jimenez and Zufiria (1987). Olson and Corcos (1980) adapted Tur-

cotte and Oxburgh’s analysis to the case where the surface (plate) moves at constant

velocity.

Much of the confusion in the different analyses may be considered to lie with the

fact that the approaches have been more or less heuristic, and have not used explicit

asymptotic expansions. The exception is the work of Jimenez and Zufiria (1987).

Various numerical results confirm the trends of these analyses, for example

Moore and Weiss (1973) and Jarvis and McKenzie (1982). It is worth emphasiz-

ing that the estimated error in Nu/R

1/3

may not be that small, however, and that

it is unlikely that numerical computations have been done at sufficiently high R to

deliver adequate quantitative agreement. Nor have such computations ever been car-

ried out in a way that would indicate numerical agreement, for example by plotting

Nu/R

1/3

versus R.

Variable Viscosity The analytic study of strongly temperature-dependent viscos-

ity at high Rayleigh number was done by Morris and Canright (1984) and Fowler

(1985a). The two studies are essentially similar, but differ in detail. Morris and Can-

right assume the base of the stagnant lid is flat, and thus do not encounter the large

stresses which occur in the lid. Fowler considered this case, but thought it less likely

than the case where the lid base is sloped, and this latter case seems to be more like

the numerically computed results.

The development of numerical methods for strongly temperature-dependent vis-

cous convection owes its inspiration to Christensen and co-workers (see, e.g., Chris-

tensen 1984a, 1984b, 1985; Christensen and Harder 1991), but these early results

were limited to viscosity variations of 10

6

or so. It is not until the later computa-

tions of Solomatov and co-workers (Moresi and Solomatov 1995; Solomatov 1996;

Reese et al. 1999; Reese and Solomatov 2002) that larger viscosity variations were

obtained, which are more appropriate for inferring mantle behaviour, and for mak-

ing comparisons with the asymptotic results. Nataf and Richter (1982) conducted

laboratory experiments.

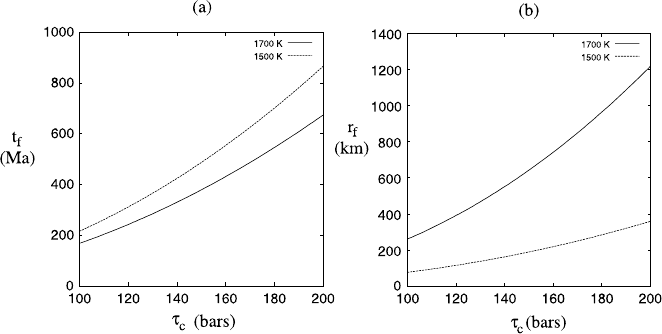

If strong pressure dependence is included as well, there is little to indicate what

the appropriate limiting behaviour is. Figure 8.10 shows the results of a computa-

tion which shows the stagnant lid clearly enough, but there is no clear asymptotic

structure visible. Apparently, there have been no clear computational results which

suggest an appropriate limiting behaviour, and there has been no asymptotic analysis

able to treat the situation where the temperature and pressure dependence are equally

strong. The viscosity, when scaled, takes the approximate form (from (8.174))

η =

Λ

τ

n−1

exp

1 −T +μ(1 −z)

εT

, (8.303)

8.8 Notes and References 527

Fig. 8.10 Stream function

contours of a temperature-

and pressure-dependent

viscosity convection

calculation at Rayleigh

number 10

6

, the viscosity

scaled to that at the basal

temperature. The rheology is

that of (8.303), with Λ =1,

n =1, ε =0.077 and

μ =0.5. Basal and surface

dimensionless temperatures

are 1 and 0.1, respectively.

The absence of contours

towards the top indicates the

stagnant lid. Figure courtesy

Mike Vynnycky

where z is scaled height above the core–mantle boundary, and representative values

are ε ∼0.023, μ ∼2.8.

Conventional wisdom has it that the vigorous, high Rayleigh number flow in the

mantle is adiabatic; by analogy with the atmosphere (see Chap. 3) we balance the

advective terms in (8.8)

6

:

ρ

dT

dt

−DT

dp

dt

≈0, (8.304)

which gives below the lithosphere (even allowing that C>0)

T =T

ad

≈exp[DZ], (8.305)

where Z =1−z is the dimensionless depth; thus the adiabatic temperature increases

roughly exponentially with depth. Earlier we found D ≈0.9, but this value probably

decreases with increasing depth because of the decreasing value of α. In contrast,

we may define an isoviscous profile in which (from (8.303), and ignoring stress

dependence),

T =T

iso

≈1 +μZ. (8.306)

(8.306) tacitly assumes C =0in(8.8)

5

.IfwetakeC>0, then

T =T

iso

≈1 +

μ

C

e

cZ

−1

Z. (8.307)

The isoviscous and adiabatic profiles are quite different in general, and T

iso

>T

ad

,

even if one allows for the decrease of both D and μ with increasing depth. Since, if

T ≈T

ad

,

η ∼exp

T

iso

−T

ad

εT

ad

, (8.308)

528 8 Mantle Convection

we see that a sub-asthenospheric adiabatic temperature will cause the mantle vis-

cosity to increase dramatically and exponentially, and this must have the effect of

reducing the velocity, thus removing the reason why the temperature was adiabatic

in the first place.

What this suggests is that the sub-asthenospheric temperature is close to isovis-

cous,

T ≈T

iso

+O(ε), (8.309)

with the small correction providing both the unknown viscosity and the buoyancy

term, while the energy equation determines the vertical velocity, and mass conser-

vation then gives the horizontal velocity. Various shear and thermal boundary lay-

ers would be necessary to complete the description of the flow, but determining

these seems to be quite a hard problem, and has not yet been done. See also Fowler

(1993a) and Quareni et al. (1985).

An isoviscous mantle temperature provides a nice explanation of why indepen-

dent post-glacial rebound studies invariably indicate relatively constant estimates

of mantle viscosity below the lithosphere (Cathles 1975), and it explains how the

mantle temperature can reach a value of some 4,000 K at the core–mantle bound-

ary (Jaupart et al. 2009), despite a relatively low adiabatic temperature there, and

the impossibility of basal thermal boundary layer jumps of more than a few hun-

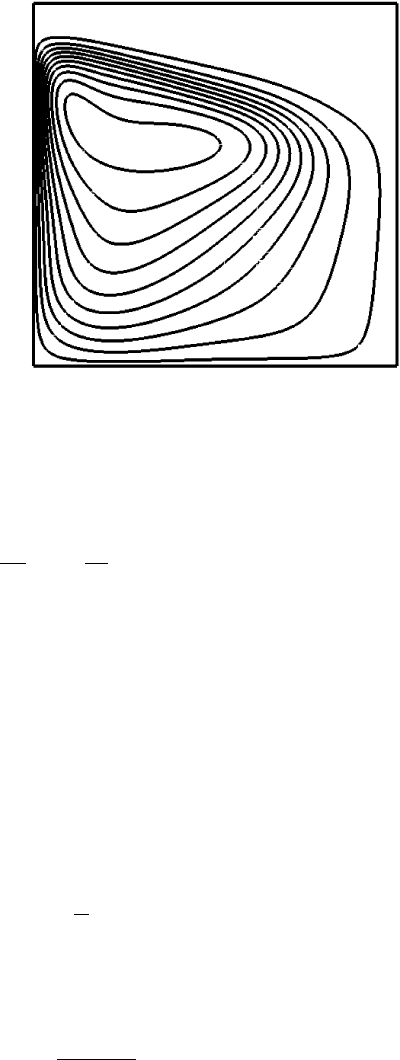

dred degrees (because of the strongly variable viscosity) (Fowler 1983). Figure 8.11

shows a temperature- and pressure-dependent viscous computation, corresponding

to Fig. 8.10, wherein only the viscosity variation in the convecting core is indicated.

As is the typical case, the parameters are not extreme enough to indicate what the

appropriate asymptotic régime is.

The Issue of Subduction It was realised fairly early on that variable viscosity

convection caused a stagnant lid to occur, and that subduction would only occur if

some form of weakening was made. Initially in numerical models, artificial weak

zones were introduced, but more sophisticated strain-weakening rheologies were

later introduced, and shown to produce self-consistent subduction-like behaviour

(Bercovici 1993; Tackley 1998, 2000a, 2000b: see also the review by Bercovici

2003). These authors sometimes use a rheology in which stress τ is a function of

strain rate ˙ε which first increases to a maximum and then decreases (a ‘pseudo-

plastic’ rheology), or a ‘visco-plastic’ rheology with a specific yield stress, similar

to that used here. The present discussion follows Fowler (1993b) and Fowler and

O’Brien (1996, 2003); illuminating further insight on the transition between stag-

nant and mobile lids is given by Moresi and Solomatov (1998), who show that the

inclusion of a yield stress in a numerical model of strongly temperature-dependent

viscous convection can lead either to a fixed lid, a mobile lid, or a cycling between

the two, depending on the value of the yield stress. This resembles the putative be-

haviour apparently observed on Venus.

A hallmark of most of these failure theories is the relatively low value of yield

stress which is necessary to initiate subduction. The values here, about 100–200

bars (10–20 MPa) for Venus, and somewhat higher for Earth, are much lower than

8.8 Notes and References 529

Fig. 8.11 Viscosity contours of a temperature- and pressure-dependent viscosity convection cal-

culation at Rayleigh number 10

6

, the viscosity scaled to that at the basal temperature. The rheology

is that of (8.303), with Λ =1, n =1, ε = 0.077 and μ =0.5. Basal and surface dimensionless tem-

peratures are 1 and 0.1, respectively. The viscosity variation from top to bottom is of order 10

20

,

so that the upper part of this range (in the lid) is excised. The resulting colour indicates a variation

from (dimensionless) viscosity 10

−2

(blue)to10

4

(red). Figure courtesy Mike Vynnycky

the brittle strength of near-surface crustal rocks. However, it is not thought that

brittle failure is relevant in the lower parts of the lithosphere, but rather that various

mechanisms, such as dynamic recrystallisation and void formation (Tackley 1998),

may promote the formation of weak shear zones. Once these exist, analogously to

faults such as the San Andreas fault, it is easy to suppose that they remain weak and

promote slip. It is less easy to imagine the process whereby they form initially, at

the onset of subduction.

Sub-continental Convection The success of mantle convection theory is most

obvious for sub-oceanic convection. The plates move away from mid-ocean ridges,

causing a square root of age decrease in heat flux, essentially as observed (Par-

sons and Sclater 1977), because of the similarity solution of the thermal boundary

layer equation. There is no such comparable law for continents, which do not fit

the concept of active plate convection. Continental lithosphere is often supposed

thicker, reflecting the lower value of heat flux despite the concentration of heat-

producing elements (Davies and Davies 2010). In fact, the simplest interpretation

of sub-continental convection is to suppose that it is of the stagnant lid type. If that

is the case, then the Earth’s mantle consists of adjoining convective cells of very

different types.

Phase Changes and Geochemistry There is a good deal concerning mantle con-

vection which we have simply passed over. Perhaps the most serious omission is