Li S.Z., Jain A.K. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Biometrics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

adhere. It can be done of different materials, but it is

mainly done with glass. In a hand-geometry device, it

means the flat surface of the hand geometry reader on

which the person presented to the device places his or

her hand. The platen is usually equipped with a num-

ber of pegs (or pins) to guide the placement of the

person’s hand and to ensure the accurate measuring of

the hand’s geometric structure.

▶ Fingerprint, Palmprint, Handprint and Soleprint

Sensor

▶ Hand-Geometry Device

Point-Light Display

The motion of a living thing depicted by just the motion

of specific points on the body. Originally generated by

filming actors in darkened rooms, wearing dark clothes

with lights attached to the joints. By adjusting the con-

trast of these films only the motion of the lights was

visible. Modern day point-light displays are generally

created by movement data obtained by three-dimen-

sional motion capture equipment such as the one used

for computer animation. The point-light display shows

the motion of the actor with the majority of other

person information subtracted from the display.

▶ Psychology of Gait and Action Recognition

Polar

Polar images are recorded as a matrix in which each

element of the matrix is an intensity value whose

location is expressed in polar coordinates. The origin

of the coordinate system is defined as the center of the

image, and the location of each intensity sample is

expressed as a radial distance r from the center along

a particular angular direction y. Typically, each row in

the image matrix contains all of the angular samples

for a particular radial distance, and each column of the

image matrix contains all of the radial samples for a

particular angular direction.

▶ Iris Image Data Interchange Formats, Standardization

Polarized

Of or relating to one or more poles (as of a

spherical body).

▶ Iris Standards Progression

Police Law Enforcement

▶ Law Enforcement

Portal

▶ Iris on the Move

Pose

The angle of the head relative to the camera-to-subject

line.

▶ Photography for Face Image Data

Pose and Motion Models

Models that describe what combinations of joint angles

are plausible and how they can vary over time in

typical human motions. They are often expressed

probabilistically and specify the probability of a single

3D pose or of a set of consecutive poses.

▶ Markerless 3D Human Motion Capture from

Images

1090

P

Point-Light Display

Poststratification

Poststratification is a statistical technique that forms

strata of observations after the data has been collected

to better inform statistical inference.

▶ Test Sample and Size

Potential Energy Transform

An invertible linear transform which transforms an

image into an energy field by treating the pixels as an

array of particles that act as the source of a Gaussian

potential energy field. It is assumed that there is a

spherically symmetrical potential energ y field gener-

ated by each pixel, so that Eðr

j

Þ is the total potential

energy imparted to a pixel of unit intensity at the pixel

location with position vector r

j

by the energy fields of

remote pixels with position vectors r

i

and pixel inten-

sities Pðr

i

Þ, and is given by the scalar summation,

Eðr

j

Þ¼

X

i

Pðr

i

Þ

r

i

r

j

8i 6¼ j

08i ¼ j

8

>

<

>

:

9

>

=

>

;

: ð1Þ

To calculate the energy field for the entire image, Eq. 10

should be applied at every pixel position. For efficiency

this is calculated in the frequency domain using Eq. 11

where ℑ stands for FFT and ℑ

1

stands for inverse FFT.

energyfield ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

M N

p

ℑ

1

ℑ unit energy fieldðÞ½

ℑ imageðÞ:

ð2Þ

▶ Physical Analogies for Ear Recognition

Preemployment Screening

▶ Background Checks

Pre-Processing

Palmprint pre-processing refers generally to the extrac-

tion of the region of inte rest and its normalization. A

coordinate system is defined to align different palm-

print images for matching. Normally, the central part

of a palmprint is extracted from the image boundaries

for reliable feature measurements. The extracted cen-

tral part is furt her subjected to histogram equalization.

▶ Palmprint Features

Pretty Good Privacy (PGP)

Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) is a computer program that

provides cryptographic privacy and authentication. It

was originally created by Philip Zimmermann in 1991.

▶ Fingerprints Hashing

Primary Biometric Identifier

Anatomical and behavioral characteristics such as fin-

gerprint, palmprint, face, iris, hand-geometry, voice,

signature, and gait can be used to reliably determine or

verify a person’s identity. These biometric traits consti-

tute a strong and permanent ‘‘link’’ between a person

and his identity and these traits cannot be easily lost or

forgotten or shared or forged. Hence, they are known

as primary biometric identifiers and the systems that

recognize people based on such traits are referred to as

primary biometric systems.

▶ Soft Biometrics

Principal Component Analysis

See PCA (Principal Component Analysis)

Principal Component Analysis

P

1091

P

Principal Curvatures

The maximum and minimum values of the normal

curvature at a point on the surface are called the

principal curvatures. At any given point on the surface,

intersection of the surface with a plane containing the

normal vector and a particular tangent direction forms

a curve. Curvature of this curve is called the normal

curvature. Curvature values in all tangent directions

form the normal curvatures at that point.

▶ Palmprint Features

Principal Lines

Human palmprints show a number of well defined

lines. These include major palmlines, often called the

principal lines, and wrinkles. Principal lines and wrin-

kles on palm are distinguis hed by their position and

thickness. Most palmprints show three principal lines:

heart line , head line and life line. Properties of the

principal lines can be summarized as follows:

1. Each principal line meets the side of the palm at

approximate right angle, when it flows out

2. The life line is located at the inside par t of the palm,

which gradually inclines to the inside of the palm

3. In most cases, the life line and head line flow out of

the palm at the same point

▶ Palmprint Features

Privacy

Privacy is the ability or right of an individual to control

how information pertaining to that person is collected,

distributed, and used. Surveillance, by its premise vio-

lates or at the least infringes on the privacy of an

individual. Hence, in that regard, it is extremely im-

portant to ensure that the information collected (with

or without consent) does not violate the legal rights of

the individual.

▶ Surveillance

Privacy Issues

TERENCE M. SIM

School of Computing, National University of

Singapore, Singapore

Synonym

Data protection

Definition

Privacy is a multidimensional and evolving concept,

whose definition varies according to country and

culture. It is thus difficult to agree on a precise defini-

tion that is universally accepted. Nevertheless, certain

notions of privacy have become fairly standard, espe-

cially among industrialized nations. These include:

informational, bodily, territorial, and communications

privacy. Of these, biometrics not only impacts infor-

mational privacy, but also affects bodily and territorial

privacy as well. However, contrary to the claims of civil

libertarians and to Hollywood hype, biometrics need

not be antithetical to privacy. Indeed, by understand-

ing the relevant issues, it is possible to design into a

biometrics system measures that will safeguard, and

even enhance, privacy. Doing so will increase user

acceptance of biometric systems, or at least, render

such deployments more tolerable.

Introduction

Losing one’s privacy often entails consequences. At

best, the consequence is fortuitous, as when receiving

an unsolicited discount on a product that one was

about to purchase. At worst, loss of privacy could result

in harassment, marital discord, or even termination of

employment. Biometrics, by its very nature, impac ts

privacy. Civil liberty advocates routinely decry its use,

1092

P

Principal Curvatures

and Hollywood movies often por tray it negatively. Yet

biometrics, when judiciously used, can in fact enhance

privacy by improving security to sensitive data. This

chapter examines the privacy issues arising from the

deployment of biometric systems, and suggests ways in

which careful system design, along with government

policies, industry best practices, research and educa-

tion, can ameliorate privacy concerns, leading to grea-

ter user acceptance of such systems.

Privacy is a relatively new concept, dating back to

around 1900

A.D. Although some authors have tried to

argue that privacy notions may be found in ancient

religious texts such as the Christian Bible and the

Islamic Koran, most would agree that privacy appe ared

in public consciousness and began influencing public

policy only at the turn of the last century. In Europe,

privacy notions came about largely in response to

rapid urbanization and the horrors of two World

Wars, leading to its formal articulation in the 1950

European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

In the U.S., the 1890 journal article by Warren and

Brandeis [1] may be considered a defining moment.

In other parts of the world, the development of

privacy often mirrors economic and political progress.

Privacy laws are most developed in nations that have

achieved high economic output, and where democratic

principles have been established for some time. Privacy

issues are by no means static; new technologies often

reveal subtle nuances in prevailing notions, and expose

inadequacies in existing laws, leading to new regula-

tions or amendments being proposed. Changing user

perceptions, brought about by increasing technolog-

ical savvy, also play a role in shaping public policy on

privacy. An historical account of privacy developments

in different countries, no doubt an interesting study, is

outside the scope of this chapter. For general privacy

issues, please see [2–5].

Privacy Notions

Although actual definitions vary depending on culture

and country, four notions of privacy are almost uni-

versally accepted:

Informational privacy: This pertains to the collec-

tion and subsequent usage of

▶ personal data.

Bodily privacy: This concerns protecting the physi-

cal body from invasive procedures.

Territorial privacy: This relates to the observation of

one’s activities in a physical space, esp ecially one’s

home or bedroom, but also in public places where

anonymity is to be expected.

Communications privacy: This addresses the protec-

tion of one’s communications, such as emails, let-

ters, and telephone conversations.

Informational privacy can in turn be understood in

terms of four concepts:

▶ unnecessary data collection,

unauthorized data collection,

▶ unauthorized data dis-

closure, and

▶ function creep.

By definition, biometrics is personal data: a biomet-

ric sample is a measurement of a human body for the

purpose of identifying that person. Moreover, in ty pical

usage, other personal data, e.g. date of birth or address,

are also retrieved along with the identifica tion. Clearly

then, biometrics impacts informational privacy. But

there are other concerns as well. For some biometrics,

notably DNA samples and retina scans, the very act of

acquiring the biometric may be considered an invasion

into one’s body. These types of biometrics, thus, affect

bodily privacy. Likewise, for end-users who regard phys-

ical contact as unhygienic, placing one’s finger on a

fingerprint sensor may constitute a violation of bodily

privacy. Such an aversion to physical contact will be

especially acute during an epidemic, as when SARS

broke out in 2003

A.D. Finally, there may be issues with

territorial privacy as well. Whenever face recognition is

coupled with surveillance cameras to monitor a public

space, one’s anonymity is lost when traveling through

that space. Biometrics that can be remotely acquired

without the user’s cooperation, such as face images, and

to a lesser extent voice patterns, potentially increase

territorial privacy risks. Unfortunately, with expected

improvements in sensor technology, more types of

biometrics will be amenable to remote acquisition,

even for those that currently require physical contact.

Biometrics is inherently privacy-neutral: it neither

enhances nor enervates privacy. It is no different from

a database record of a person’s particulars. The real

concern is how biometrics is used, or more precisely,

misused. The misuse of biometrics is more potentially

more damaging than the misuse of a database record

because one cannot lie about biometrics the way

one can falsify one’s name or address. For example,

one cannot give a fake photograph when pressured by

a salesperson to sign up for some dubious product

offer. Moreover, biometrics is generally permanent

Privacy Issues

P

1093

P

throughout a person’s lifetime, and thus cannot be

revoked once compromised (unlike changing a pass-

word, PIN, or even one’s name). This immunity from

falsification and revocation makes biometrics a good

choice as an universal identifier. For example, banks,

government agencies, and supermarkets may use the

thumb print for verification. The convenience of using

a single fingerprint to access one’s bank account, to

obtain government services, and to pay for groceries is

extremely compelling for end-users and organizations

alike. But so are the risks correspondingly magnified.

The linking of the bank’s database with those of the

government and the supermarket to monitor one’s

intimate details would, in most places, be considered

an egregious invasion of privacy. Even if such moni-

toring were sanctioned by the appropriate authority,

the victim is unlikely to derive much comfort.

Privacy is not the same as security. Privacy is

concerned with people (their intimate details, personal

space), whereas security has to do with systems. A good

privacy policy protects people, whereas a secure system

is one that is effective at preventing unauthorized

access to the resource being protected. Identity theft

(the use of someone else’s identity for personal gain) is

primarily a security breach, but also a privacy viola-

tion. Thus, privacy begins with securing the biometric

system itself. An insecure biometric system affords

little privacy protection.

Effectively addressing the privacy issues arising from

the deployment of biometric systems require a holistic

and multipronged approach. This chapter highlights

five ways, as described in the following sections.

System Issues

Privacy should not be an afterthought; rather, mea-

sures to safeguard privac y should be designed into

a biometric system right from the beginning. Good

strategies for doing this may be found in [6, 7].

In additi on, [8] has two chapters on the privacy aspects

of biometrics in relation to U.S. and European laws.

The following highlights the main issues.

1. Alternative technologies. Consider nonbiometric alter-

natives. Biometrics is not the only technology for

verifying identity or controlling access to a protected

resourc e. Other technologies may be more appropri-

ate, and less privacy invasiv e. For instance, the humble

lock-and-key works very well for gymnasium lockers,

and replaci ng it with a fingerprint access control

system seems excessive . Besides the obvious privacy

concerns, the fingerprint system does not permit the

ad hoc transfer of authorization, as when asking a

friend to retrieve one’ s belongings from the locker.

The low-tech lock-and-key has no such problem.

2. Choice of biometrics. Choose a biometric appropri-

ate for the applica tion, taking into account cultural

and religious sensitivities. As mentioned before,

DNA and retina scans may be regarded as invading

one’s bod ily privacy because of the way these sam-

ples are collected. Since DNA can reveal genetic

defects and retina scans can reveal diabetes, their

usage can lead to function creep (also see below).

Likewise, avoid choosing biometrics that requires

physical contact for acquisition w hen doing so

would alarm end-users who consider such contact

unhygienic. Finally, using face recognition may

offend the modesty and privacy of end-users who

veil their faces for religious reasons.

3. Template storage. To enhance privacy, templates

must be securely stored, preferably with a strong

encryption method. Moreover, distributed storage

is preferred over a centralized database. Where

possible, delete the template as soon as it is no

longer required. This is preferable to storing it

indefinitely. Finally, allowing the end-user to decide

when and how the template can be used reduces

privacy risks. This could be achieved by permitting

the end-user to opt in or out (of using the biomet-

ric system) at the end-user’s discretion, or to speci-

fy the encryption method, or the duration and

location of template storage. In this regard, the

▶ Match-on-Card technology for fingerprint veri-

fication, in which all the steps in the biometrics

architecture are implemented on the smart card

itself, comes closest to fulfilling this privacy ideal.

4. Function creep. Once a biometric system is opera-

tional, it is often convenient to use it for other

purposes. From a privacy perspective, this must be

resisted, even if the secondary purpose is a noble

one. At the very least, consent must be obtained

from the end-user for the expanded scope of bio-

metric usage. This is especially true for biometrics

that reveals more than just identity, e.g., DNA and

retina scans that reveal medical conditions, finger

vein patterns that reveal blood oxygen level, and

face images that reveal gender, ethnicity, and

1094

P

Privacy Issues

approximate age. The potential for medical, sexual,

racial, and age-related discrimination arising from

using such nonidentity information is clear. At

times, function creep can be subtle, as the next

example illustrates: To improve security, a secondary

school (name suppressed to avoid embarrassment)

implemented a fingerprint system to control access

to its science and computer laboratories. It soon

discovered a serendipitous way to reduce its electric-

ity bill: by identifying persons leaving the labs with-

out switching off the air conditioner.

Government

Governments play three important roles in ensuring

that biometric usage protects privacy: by enacting

appropriate laws, by self-regulation, and by cooperat-

ing with other governments. Privacy requires legal

backing to be effective. Yet laws are notoriously

difficult to get passed. A quick survey of the state of

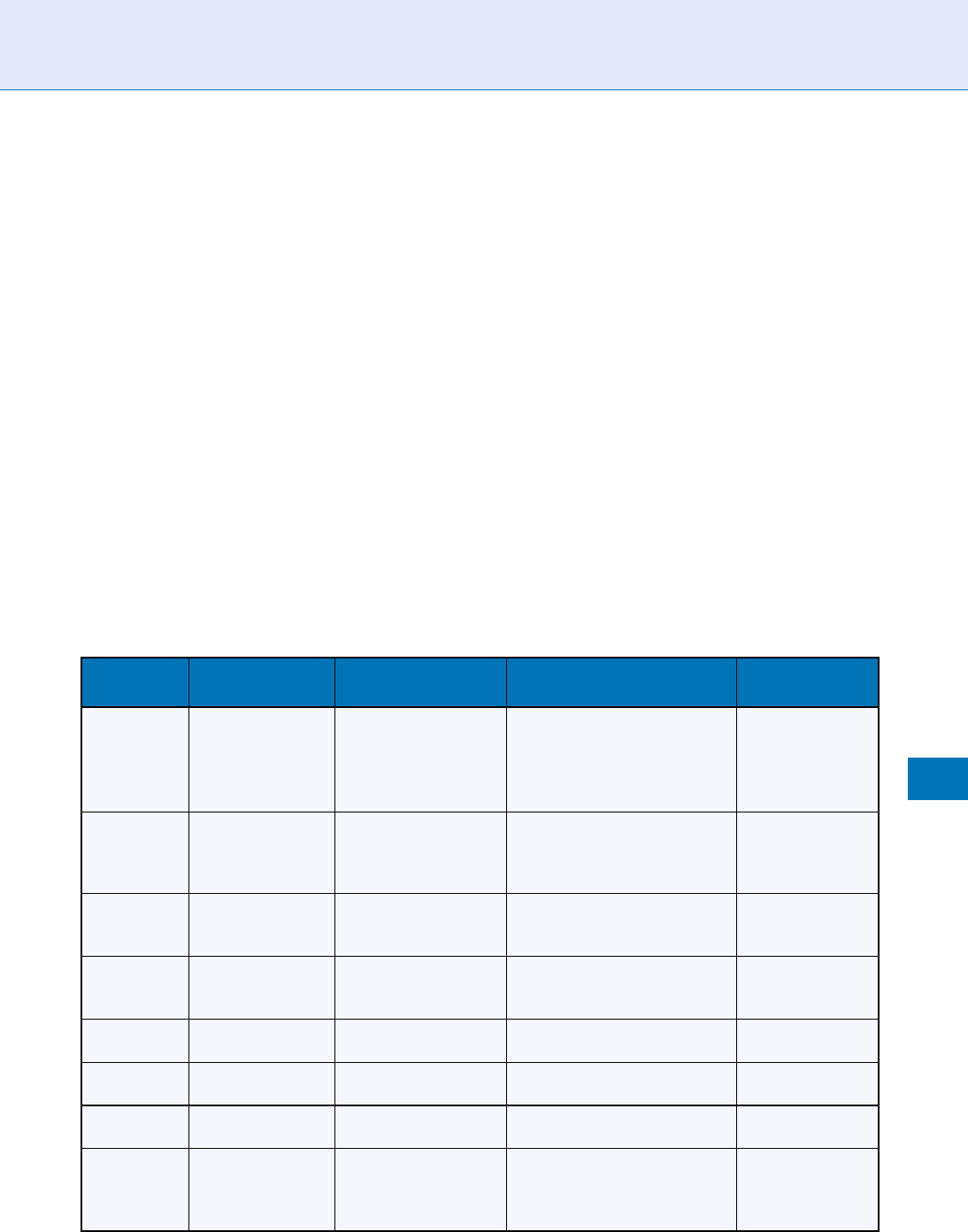

privacy laws in selected countries is shown in Table 1.It

is clear from the table that constitutional provision

for privacy does not automatically guarante e stronger

privacy laws. For example , both Canada and Australia

do not provide for privacy rights in their Consti-

tutions, yet both have enacted a Privacy Act and a

Privacy Commissioner to oversee and prosecute priva-

cy violations. China and the U.S. are opposite exam-

ples, having some form of privacy rights in their

Constitutions but no specific Privacy Act. Instead,

both rely on a hodgepodge of sectoral laws to regulate

privacy. Besides having the right laws, it is also neces-

sary to review them periodi cally as biometrics may

engender unanticipated privacy issues. Nevertheless,

countries having an explicit Privacy Act and appoint-

ing a Privacy Commissioner are expressing a strong

commitment to protect privacy. The experience of

Australia, Canada, and Hong Kong are thus worth

learning from.

Privacy Issues. Table 1 Privacy laws in selected countries, excerpted from [2, 3]

Country/

region

Privacy in

constitution? Related laws Privacy act?

Privacy

commissioner?

Australia Crimes Act,

Telecommunications

Act,

Data-Matching Program

Act

Privacy Act 1988 ü

Canada PIPEDA,

Telecommunications

Act,

Bank Act

Privacy Act 1983 ü

China Limited rights Civil Law,

Practice Physician Law,

Law on Lawyers

European

Union

1950 European

Convention on

Human Rights

Telecommunications

Privacy Directive

Personal Data

Directive 1995

Hong Kong

S.A.R.

in Basic Law — Personal Data (Privacy)

Ordinance 1996

ü

Japan Article 13 — Protection of Personal

Information Act 2003

various Ministers

Singapore Banking Act,

Computer Misuse Act

United States Not explicit Video Privacy Protection

Act,

Right to Financial

Privacy Act

Privacy Act 1974

(limited to govt)

Privacy Issues

P

1095

P

In most countries, the Government is also the larg-

est deployer of biometric systems. Thus, governments

can strongly influence how biometrics is used by

practicing self-regulation, and maintaining transpar-

ency and accountability. Governments should not, for

example, covertly deploy surveillance systems, nor

share sensitive data between agencies across different

jurisdictions. Federal and local authorities should

also respect each other’s boundaries. These prescrip-

tions are self-e vident, perhaps even naı

¨

ve. Alas, they

are usually circumvented in the name of national secu-

rity and expediency. Most nations have emergency

laws that can be invoked when confronting terrorism

threats or disease epidemics. Such laws usually give

the government carte blanche power, to the detriment

of privacy concerns. While citizens are generally will-

ing to give up some privacy in exchange for personal

safety during times of threat, governments are less

willing to relinquish their power once the crisis sub-

sides. This asymmetry ought not to exist, and should

be corrected.

The third important role of the government

is international cooperation. In this digital age of trans-

border data flows, privacy is only as strong as the weak-

est jurisdiction. Already, regional and international

standards have been drawn up to address common

privacy issues. Examples include the OECD Guidelines

on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows

of Personal Data, the European Union Personal Data

Directive, and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

Privacy Framework. Arguably, more can be done to

ratify and implement these guidelines in a timely man-

ner across member countries.

Industry

Privacy is too important to be left in the hands of

governments. Complementing government legislation,

and often faster to enact, is a necessary set of industry

regulations developed and updated by a nonpartisan

biometrics association. Such an association should ide-

ally consist of vendors, end-users, legal counselors, and

academics. Its role is to promote best practices, certify

compliance of vendor products with international

biometrics standards, educate the public, and otherwise

regulate the industry.

An example of this is the nonprofit Biometrics

Institute in Australia [9], which recently drafted a

Privacy Code and obtained the approval of the coun-

try’s Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC). The

Code, essentially an industry-specific realization of

Australia’s National Privacy Principles, recommends

guidelines for how biometrics data should be collected,

used, and disclosed, among other things, to safeguard

privacy. Members of the Institute voluntarily subscribe

to the Code, thereby agreeing to be bound by it.

In return, the subscriber establishes itself as a trust-

worthy party, and gains exclusive rights to bid for

government projects that require privacy certification.

Code violations are handled directly by the OPC,

which, unlike the Institute, has the legal teeth to pros-

ecute. This symbiotic relationship between the Insti-

tute and the OPC is admirable, and greatly enhances

public trust. Independent of the Code, the Institute

also conducts privacy impact assessments and educa-

tional talks for members.

Another essential role of the industry is to track

and participate in international standards, usually in

partnership with a government standards body. The

ISO JTC 1/SC 37 is the Biometrics Technical Sub-

committee under the ISO umbrella [10]. Its biannual

meetings divide into several workgroups, the sixth of

which concerns the ‘‘Cross-Jurisdictional and Societal

Aspects of Biometrics,’’ thus encompassing privacy

issues. Of interest is the still under development tech-

nical reference ISO/IEC DTR 24714 parts 1 and 2,

which lists 15 privacy principles for biometric sys-

tems. Although not yet publicly available, these docu-

ments are useful for reference and for adapting to suit

country-specific norms.

Research

Since biometrics is a technology, it seems plausible to

combat its ‘‘evils’’ with more technology. So-called

Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PET) aim at protect-

ing privacy while enabling their benefits to be enjoyed.

One possibility centers around the problem of autho-

rization without identification.

For many applications, it is not the identity of

the end-user that matters, but only whether the

end-user is duly authorized. That is, what needs to

be established is a proof of authorization (or proof

of credentials) rather than a proof of identity. This is

the case for all access control systems (Is the end-user

authorized to gain access to the protected resource?),

1096

P

Privacy Issues

and subscription systems (Does the end-user have

the necessary credentials for this service?). Proof

of authorization is a weaker notion than proof of

identity, and can in fact be achieved using a crypto-

graphic technique called zero-knowledge proof. Related

research includes group signatures and k-anonymit y,

both of which permit identification only of a group

of people, but not the individual within it. This

coarser form of identification is like protecting a

room with a traditional lock-and-key, and giving

the keys only to the group of aut horized people .

In effect, the key authorizes the group while preserv-

ing individual anonymity. For more details, please

see [11, 12].

A slight generalization of this concept is the proof

of authorized role. Here, the same person may assume

different roles when interacting with a system. For

example, it is common practice for a person to login

to a computer system either as an administrator, or as a

normal user, depending on the purpose of usage. The

required proof is not so much identity, but which role

the person wishes to assume. Different biometrics may

be associated with each authorized role to facilitate

interaction with the system.

There is yet another notion of identity: for certain

applications, not only is the identity required, but the

physical presence of the end-user must be guaranteed.

This proof of presence is clearly a stronger requirement.

An example of this is during wedding ceremonies

(be they religious or civil), where additional witnesses

are usually called upon to prove the identities and

presence of the marrying couple. Another example is

at the polling station, where it is necessary to establish

that the voter is physically present to cast his or her

vote, instead of relying on a proxy.

Distinguishing between these subtle notions of

identity is important. An authentication based on

biometrics is really a proof of presence, because the

biometric sample is collected ‘‘live’’ from the person.

Thus, using biometrics in situations that require only a

proof of authorization may be an overkill, and can lead

to privacy abuse. Research in PET is still in its early

stages, but should be encouraged and funded.

Education

The cliche

´

, ‘‘perception is reality,’’ is especially true

for biometrics, where misconceptions and hyper bole

abound. Hollywood movies such as Minority Report

(2002) and Gattaca (1997) tend to negatively portray

biometrics as powerful tools used by Big Brother

regimes to track individuals. Media reports of high

profile abuses involving biometrics further fuel public

mistrust. Occasionally, even well-meaning privacy advo-

cates unwittingly deride biometrics more than the tech-

nology deserves. Such poor perceptions can lead to

public resistance, and even sabotage, of biometric

systems.

It is, therefore, important to increase public aware-

ness through educational talks and open dialog among

vendors, deployers, end-users, and privacy advocates.

Besides the technological issues, privacy issues have

to be realistically addressed, including assuring the

end-user on what recourse is available should he or

she feel victimized. Such educational talks can be

organized by anyone, although it is better received

if it comes from a neutral party, such as the non-

partisan biometrics association (see above). Dialog

should also be on-going, because new issues are

constantly thrown up.

Future Concerns

Many advocates believe that privacy is increasingly

under attack from two main fronts. New technologies

that permit more efficient data sharing, or that facili-

tate covert surveillance or identification of individuals,

pose real threats. Also, the rise of terrorism and the

imminence of epidemics (such as avian flu) necessitate

governments to more closely monitor the movements

and activities of their citizens in a bid to, ironically,

protect the same citizens.

Biometrics technology will also be further devel-

oped. Besides providing proof of authorization or

identity, biometrics may soon be able to reveal emo-

tional states. It is already possible to detect anxiety in

the voice, adding a new level of privacy concern to

voice (speaker) recognition. Other emotion s may yet

be detectable throug h current or novel biometrics, and

could lead to a revolutionary type of lie detector.

The emerging field of neuroeconomics [13] attempts

to understand brain a ctivity (measured through func -

tional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI) and eco-

nomic decisions such as buying a product. Researchers

are able to predict, from fMRI patterns, whether or not

a person is about to make a purchase. Other research in

Privacy Issues

P

1097

P

the field of cognitive science have demonstrated that

fMRI scans can detect cognitive states in the brain.

From such developments, it is but a small step to

imagine the day that biometrics (in the broader sense

of ‘‘bodily measurements’’) will offer proof of intention,

i.e. a kind of mind reading. The privacy abuses arising

from such a clarivoyant technology are too frightening

to even contemplate.

In light of all these, what can be said about the

future of privacy? One line of argument, proffered by

James Rule [5], is that privacy goals are still eminently

feasible. To quote:

"

The issues involved are ultimately ethical and politi-

cal, not technological. If we determine to do so, we

can readily implement systems that place the burden

of justification on those who would create personal

data systems in the first place, ..., that limit the

amount and variety of personal data allowed to

bear on determinations of how organizations will

treat individuals.

However, doing this requires accepting the social

cost that information systems will necessarily be less

efficient because of increased privacy checks. Current

systems are predicated on providing better services or

making better decisions through gathering more per-

sonal data. Only by abandoning this avarice for effi-

ciency can society hope to restore privacy.

The other school of thought takes the opposite view:

that privacy is merely a passing ideal of the previous

century, increasingly irrelevant for the twenty-first

century. There will be no privacy in the future, and the

sooner we get used to it, the better. Among such

proponents is Scott McNealy, Chairman of Sun Micro-

systems, who famously quipped that ‘‘privacy is dead.’’

Increasingly, young people today act as if this is true

[14]. They are not afraid to reveal intimate details in

social networking sites, or post in their blogs videos of

themselves in situations deemed highly embarrassing

just one generation ago. They do this despite knowing

the privacy risks. They accept that their daily activities,

social habits, and personal data can be viewed by

anyone. Yet life goes on. To be sure, much private

data have only temporary value. For instance, one’s

soda and sartorial tastes are ephemeral, valid only

until the next fashion wind blows. For these young

people, losing one’s privacy in such matters is hardly

worth losing sleep over.

Related Entries

▶ Biometrics Architecture

▶ Match-on-Card

▶ Security

References

1. Warren, S., Brandeis, L.: The right to privacy. Harvard Law Rev.

IV(5) (1890)

2. Electronic Privacy Information Center: (1994). http://www.epic.

org

3. Privacy International: (1990). http://www.privacyinternational.

org

4. Staples, W.G. (ed.): Encyclopedia of Privacy. Greenwood,

Connecticut (2007)

5. Rule, J.B.: Privacy in Peril. Oxford University Press, New York

(2007)

6. National Science and Technology Council: Privacy and

Biometrics, Building a Conceptual Foundation (2006). http://

www.biometrics.gov/docs/privacy.pdf

7. Nanavati, S., Thieme, M., Nanavati, R.: Biometrics – Identity

Verification in a Networked World. Wiley, New York (2002)

8. Wayman, J.L., Jain, A.K., Maltoni, D., Maio, D. (eds.): Biometric

Systems: Technology, Design and Performance Evaluation.

Springer, New York (2005)

9. Biometrics Institute Ltd.: (2001). http://www.biometricsinstitute.

org

10. ISO JTC 1/SC 37: International Organization for Standardiza-

tion Biometrics Technical Subcommittee (2002). http://www.iso.

org/iso/home.htm

11. Camenisch, J., Lysyanskaya, A.: An efficient system for non-

transferable anonymous credentials with optional anonymity

revocation. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on

the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques,

pp. 93–118. Innsburck, Austria (2001)

12. Chaum, D., van Heyst, E.: Group signatures. In: Advances in

Cryptology, pp. 257–265. Brighton, UK (1991)

13. George Loewenstein and Scott Rick and Jonathan D. Cohen:

Neuroeconomics. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 59 (2008)

14. Nussbaum, E.: Say Everything (2007). http://nymag.com/news/

features/27341/

PrivateID™

PrivateID™ is an image processing protocol and data

standard that enables a Proof Positive-certified iris

1098

P

PrivateID™

camera to capture an image, process it and prepare it

for transport in the most secure way possible.

▶ Iris Acquisition Device

Privium

▶ Iris Recognition at Airports and Border-Crossings

▶ Simplifying Passenger Travel Program

Probabilty Density Function (PDF)

The statistical function that shows how the density of

possible obser vations in a population is distributed.

▶ Gaussian Mixture Models

Process Artifacts

When footwear outsole patterns are created either

through pressing or molding, certain defect in the

pressing tools and mould will contribute to artifacts

being left on the final product. A common artifact

formed in conjunction with the molding process is

due to tiny air bubbles being trapped within the

mould, leaving gaps in the outsole pattern.

▶ Footwear Recognition

Procrustes Shape Distance

The Procrustes shape distance is a metric that captures

the shape of an object independent of the set of Eu-

clidian transformations (translation, rotation, and

scale). The Procrustes distance computation assumes

that all objects can be represented by a set of landmark

points, each object has the same number of points, and

exact correspondence between the points is known

from one object to the next.

▶ Hand Shape

Proposal Descriptive and Decision

Making Model

P.J. van Koppen (University of Leiden and University

of Antwerp), and H.F.M. Crombag, (University of

Maastricht) analyzed all types of forensic evidence

and formulated the common, basic requirements in

an article published in the Dutch Journal for Lawyers

in January 2000. These are as follows:

1. The expert has a descriptive model at his disposal

that describes the relevant characteristics for com-

parison and identification of the mark found at the

crime scene, with the characteristics of the defendant.

2. There is sufficient variation between different per-

sons regarding these relevant characteristics.

3. The relevant characteristics change ver y little

over time that even after some time comparison is

feasible.

4. The expert has a method with which the relevant

characteristics can be established unequivocally/

unmistakably.

5. The expert has rules of decision-making at his

disposal with the help of which he can decide

about identification, based upon the comparison.

▶ Fingerprint Matching, Manual

Prosody

Prosody concerns the ‘‘melody’’ of an utterance. As such,

prosodic aspects of a sentence are rhythm, intonation,

and stress/emphasis. Acoustical expressions of prosody

are duration (of syllables/phonemes), loudness, pitch

and even formant structure (which might be different

in stressed vowels than in unstressed vowels).

▶ Voice Sample Synthesis

Prosody

P

1099

P