Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 84 TRAUMATIC OPHTHALMOLOGIC EMERGENCIES588

overlooked aspect of therapy is the instillation of a cycloplegic agent, usually cyclopentolate

(Cyclogyl), to relieve the ciliary spasm that commonly accompanies this injury. Patients also

need evaluation for tetanus prophylaxis. Most should receive topical antibiotics, drops, or

ointment. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory eye drops have also been proven to be useful.

9. What is the role of an eye patch in treatment of corneal abrasions?

A pressure patch previously was considered the most important aspect of management of a

corneal abrasion. Patches were thought to increase comfort and hasten healing. It is now

known that not only are eye patches uncomfortable but also they do not increase healing and

may promote infection. They do not prevent the involved eye from moving and should not be

used for most superficial corneal abrasions. If you do use a patch, be sure to instruct the

patient not to drive because depth perception depends on binocular vision.

10. How does a corneal abrasion from a contact lens differ from other causes of

corneal trauma?

Corneal abrasions secondary to overuse of contact lenses are much more likely to have a

bacterial process involved, often Pseudomonas. These patients should receive topical

antibiotics effective against Pseudomonas organisms (tobramycin or gentamicin) and should

never be patched. If the emergency physician is unable to do a slit-lamp examination, early

ophthalmologic referral to rule out ulcerative keratitis (corneal ulcer) is indicated.

11. What is the most common location of an ocular foreign body?

Foreign bodies are often lodged just beneath the upper eyelid along the palpebral conjunctiva.

The eyelid needs to be everted with a cotton swab to examine this area adequately. Conjunctival

foreign bodies should be suspected when many vertical linear streaks are noted on the cornea

with fluorescein examination.

12. What is the proper treatment for a corneal foreign body?

First, topical anesthesia is applied, usually proparacaine. Nonembedded foreign bodies should

be removed with a sterile, moist cotton swab. Embedded foreign bodies are removed with a

27-gauge needle or an eye spud. Most metallic foreign bodies leave a residual rust ring that

should be removed in approximately 24 hours, after the cornea has softened.

13. What is an anterior hyphema?

A collection of blood in the anterior chamber of the eye; it is seen as a layering of cells that

pool along the bottom of the eye when the patient is sitting upright. When the patient is lying

down, a hyphema is not recognized easily; it may appear as a diffuse haziness of the anterior

chamber. Small hyphemas, termed microhyphemas, may be identified only with a slit lamp.

14. How is an anterior hyphema treated?

The standard in the past was to admit all patients for bed rest; today the dominant tendency is

toward outpatient management. The patient should be kept upright, the eye patched, and

ophthalmologic consultation initiated, at least by phone. Complications include rebleeding,

glaucoma formation (particularly in patients with sickle-cell trait), and corneal staining.

15. What physical findings lead to the suspicion of a blow-out fracture?

Classic findings with a blow-out fracture (fracture of the inferior orbital wall with herniation of

the global contents into the maxillary sinus) are (1) decreased sensation over the inferior

orbital rim, extending to the edge of the nose and ipsilateral upper lip, secondary to

compromise of the inferior orbital nerve; (2) enophthalmos, or a sunken appearance of the

eye, which may be masked by edema; and (3) paralysis or limitation of upward gaze

(manifested as diplopia), resulting from entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle.

16. What is traumatic mydriasis?

An efferent pupillary defect manifested by a dilated (in most instances irregular) pupil that

does not react to direct or consensual light, usually as a result of minor trauma to the eye.

Chapter 84 TRAUMATIC OPHTHALMOLOGIC EMERGENCIES 589

Because such a patient is at risk for other more serious eye injuries, a careful eye examination

is mandatory. The possibility of uncal herniation secondary to intracranial injury should be

considered if level of consciousness is decreased in the presence of a perfectly round,

nonreactive, unilateral, dilated pupil. If level of consciousness is unaltered, this is most likely

an isolated ocular injury.

17. Why is a history of hammering metal on metal important in a patient

presenting with an eye complaint?

Often a small, high-velocity fragment penetrates the globe with minimal or no physical

findings. This injury, which can cause inflammation weeks later, is diagnosed with soft-tissue

radiographs of the orbit or a computed tomography (CT) scan of the globe.

18. Which eyelid lacerations should be repaired by an ophthalmologist or plastic

surgeon?

Those involving the:

n

Lid margin or gray line

n

Tear duct mechanism along the lower eyelid

n

Tarsal plate or levator muscle

19. When should penetration of the globe be suspected?

The pupil is usually misshapen, pointing in the direction of the penetration. The globe may

appear soft because of decreased intraocular pressure. Intraocular pressure should not be

tested if a penetrating injury is suspected because the pressure promotes extrusion of

aqueous humor.

20. List traumatic ophthalmologic injuries that require immediate ophthalmologic

consultation.

n

Chemical burns of the eye

n

Orbital hemorrhage with increased intraocular pressure

n

Perforation of the globe or cornea

n

Lacerations involving the lid margin, tarsal plate, or tear duct

n

Lens dislocation

21. Name two ophthalmologic injuries that require urgent ophthalmologic

consultation (within 12–24 hours).

Anterior hyphema and blow-out fracture.

22. What is solar keratitis?

Also known as flash burns or snow blindness, solar keratitis is a corneal injury secondary to

overexposure to ultraviolet light. Diagnosis is made with fluorescein staining, which shows

multiple punctate lesions of the cornea. Treatment consists of resting the eyes with adequate

narcotic analgesia. Spontaneous resolution can be expected in 12 to 24 hours.

23. What is the significance of a retro-orbital hematoma?

Bleeding behind the globe (retro-orbital hematoma) can lead to elevated orbital pressure,

which can be greater than the perfusion pressure of the retina and result in ischemia.

Treatment is a lateral canthotomy, which releases the canthus that holds the eye in its socket.

This allows for proptosis of the globe, which (temporarily) relieves the elevated retro-orbital

pressure, preserving blood flow to the retina.

24. What is the cause of a dilated pupil that fails to constrict with topical

pilocarpine?

A dilated pupil that fails to constrict with topical miotic agents is due to topical application of a

mydriatic agent often because of rubbing the eye after application of a scopolamine patch (for

motion sickness).

Chapter 84 TRAUMATIC OPHTHALMOLOGIC EMERGENCIES590

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. McInnes G, Howes D: Lateral canthotomy and cantholysis: a simple, vision-saving procedure. Can J Emerg

Med 4:54, 2002.

2. Quinn SM, Kwartz J: Emergency management of contact lens associated corneal abrasions. Emerg Med J

21(6):755, 2004.

3. Turner A, Rabiu M: Patching for corneal abrasion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2) 264–270, 2006.

4. Weaver CS, Terrell KM: Evidence-based emergency medicine. Update: do ophthalmic nonsteroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs reduce the pain associated with simple corneal abrasion without delaying healing? Ann

Emerg Med 41(1):134–140, 2003.

1. Preservation of vision in a chemical burn is directly related from time of exposure to time

initiating irrigation; do not wait for the patient to arrive at the hospital.

2. Never patch a patient with an eye injury related to contact lens; a patch provides a perfect

environment for bacterial proliferation. These patients should be treated with aminoglycoside

ointment.

3. Diplopia on upward gaze is the hallmark of a blow-out fracture of the orbital floor.

KEY POINTS: OPHTHALMOLOGIC EMERGENCIES

591

CHAPTER 85

NECK TRAUMA

Jeffrey J. Schaider, MD

1. Why is neck trauma a complicated topic?

The lack of bony protection makes the anterior neck especially vulnerable to severe, life-

threatening injuries. The exposed anatomic structure of the neck, which contains many vital

structures of the vascular, airway, and gastrointestinal systems, provides a fertile ground for

debate and myriad opinions about modality of treatment.

2. What are the most urgent concerns in the initial management of neck trauma?

Airway and hemorrhage control. Airway management comes before anything else discussed

in this chapter. Early endotracheal intubation is indicated for any patient with existing or

potential airway compromise. Delay in airway management increases the difficulty of

intubation because of swelling and compression of the anatomic structures. Bleeding should

be controlled with pressure rather than with blind clamping. The wound should be examined

to determine whether it has violated the platysma. Injudicious probing of the wound may be

dangerous, however, because a vascular structure that has ceased to bleed may resume with

disastrous consequences when its tamponade is released.

3. What is the preferred method to secure the airway?

Rapid-sequence induction (RSI) with oral tracheal intubation should be the initial airway

approach in patients with none to minimal distortion of their airway. Patients with airway

distortion with anticipated difficult bag-valve-mask ventilation should have their airway

managed with local airway anesthesia or sedative-assisted oral tracheal intubation. The

preferred sedative medications include versed and fentanyl because they are reversible or

ketamine because it does not depress spontaneous respirations. Although the risks of blind

nasal tracheal intubation include breaking away clots and damaging a distorted airway, a

recent study from Denver found that blind nasal tracheal intubation had a 90% success rate in

the prehospital phase. Surgical airway via cricothyrotomy should be employed if endotracheal

intubation is unsuccessful. Tracheostomy is preferred over cricothyrotomy if there is severe

damage to the larynx and cricoid cartilage.

4. What common findings indicate significant neck injury?

n

Injuries involving the vascular system result in hematomas, bleeding, pulse deficit, shock,

and neurologic deficit secondary to arterial interruption.

n

Laryngeal trauma causes voice alteration, airway compromise, subcutaneous emphysema,

crepitus, and hemoptysis.

n

Signs and symptoms of esophageal disruption include pain and tenderness in the neck,

resistance of the neck to passive motion, crepitus, subcutaneous emphysema, dysphagia,

and bleeding from the mouth or nasogastric tube. The diagnosis of esophageal disruption

is difficult because of injuries to other overlying structures. Ancillary testing must be used

to assist in the diagnosis of these injuries.

For more details, see Table 85-1.

5. What are the signs and symptoms of blunt carotid artery trauma?

Of patients with blunt carotid trauma, 25% to 50% have no external signs of trauma. Delayed

neurologic signs are the rule rather than the exception; only 10% of patients have symptoms

Chapter 85 NECK TRAUMA592

of transient ischemic attacks or strokes within 1 hour of injury. Most patients develop

symptoms within the first 24 hours, but 17% develop symptoms days or weeks after injury.

Carotid artery injuries may present with a hematoma of the lateral neck, bruit over carotid

circulation, Horner’s syndrome, transient ischemic attack, aphasia, or hemiparesis. The clinical

manifestations of vertebral artery injury include ataxia, vertigo, nystagmus, hemiparesis,

dysarthria, and diplopia.

6. Name the main controversy regarding management of penetrating neck

trauma.

The management of penetrating neck trauma that violates the platysma. In the 1990s,

physicians and surgeons changed from a mandatory exploration policy for penetrating neck

wounds to a selective management approach.

7. What is mandatory exploration for penetrating neck wounds?

All patients who have wounds that penetrate the platysma muscle in the neck are explored

surgically to determine the presence or absence of injury to the deeper structures in the neck.

Some ancillary diagnostic testing (i.e., angiography, esophagography, esophagoscopy, and

laryngoscopy) may be done preoperatively, depending on the location of the wound and the

stability of the patient.

8. What are the advantages and disadvantages of mandatory exploration for

penetrating neck wounds?

During the 1940s, mandatory exploration was instituted for all penetrating wounds that violate

the platysma. This policy reduced mortality significantly and remained the only mode of

therapy until the mid-1970s. Proponents of mandatory exploration warn of the catastrophic

complications from delayed treatment and missed injuries. Neck exploration is relatively

simple, and a negative exploration has low morbidity and mortality. However, because the

negative exploration rate (no injuries found at surgery) is 50%, the cost of the operation and

the added length of hospital stay are unwarranted. Many of these operations could be avoided

with the selective approach to neck exploration.

Vascular Aerodigestive

Hematoma Respiratory distress

Hemorrhage Stridor

Neurologic deficit Cyanosis

Pulse deficit Hemoptysis

Horner’s syndrome (carotid injury) Tracheal deviation

Hypovolemic shock Subcutaneous emphysema

Vascular bruit or thrill Pneumothorax

Altered sensorium Sucking wound

Harsh, machinery-like precordial

murmur (air embolism)

Dysphonia, aphonia, hoarseness

Dysphagia

Odynophagia

TABLE 85–1. SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF SYSTEM INJURIES

Chapter 85 NECK TRAUMA 593

9. Describe the theory behind the selective surgical management of penetrating

neck wounds.

With the improved sensitivity and specificity of ancillary diagnostic testing (angiography,

carotid duplex scanning, computed tomography [CT], esophagography, esophagoscopy,

laryngoscopy), a nonoperative approach to a select group of patients, based on physical

examination and results of ancillary tests, is safe. The selective approach has reduced the

negative exploration rate from 50% to 30%.

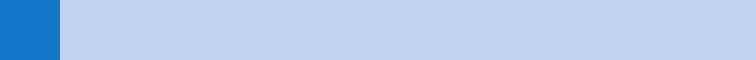

10. What are the three anatomic zones of the neck?

n

Zone I is the area below the cricoid cartilage.

n

Zone II extends from the cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible.

n

Zone III extends from the angle of the mandible to the base of the skull.

Figure 85-1 illustrates the zones of the neck.

11. Why is the neck divided into three zones?

The location of the injury plays a major role in assessing the need for angiography:

n

All zone I injuries require angiography to determine the integrity of the thoracic outlet

vessels. In stable but symptomatic patients needing surgery, angiography should be

done preoperatively because positive findings necessitate a thoracotomy before neck

exploration.

n

The familiar anatomy of zone II, coupled with relative ease of surgical exposure, minimizes

the need for angiography in symptomatic patients undergoing surgery. For patients without

clinical signs of significant injury, most recommend helical CT angiography of the neck or

carotid duplex scanning on asymptomatic patients to detect occult injuries and involvement

1. Manage airway early before airway distortion occurs.

2. Use oral tracheal intubation with RSI as initial airway management option.

3. Do not paralyze patients with significant airway distortion who cannot be ventilated.

4. Tracheostomy may be necessary as rescue airway if there is a hematoma over or damage to

cricoid cartilage.

KEY POINTS: EARLY AIRWAY MANAGEMENT FOR NECK

INJURIES

Figure 85-1. Zones of the neck.

Chapter 85 NECK TRAUMA594

of vertebral vessels before observation. Some clinicians observe asymptomatic patients

with penetrating injuries without any imaging.

n

The management of zone III injuries is controversial because of the complex anatomy of

the area and the difficulty in obtaining adequate exposure. Most clinicians agree that for

asymptomatic patients not undergoing surgery, angiography is necessary to assess the

status of the internal carotid artery and the intracerebral circulation. For symptomatic

patients, preoperative angiography is helpful because high internal carotid artery injuries

are difficult to visualize at operation and may require carotid artery ligation and concomitant

extracranial-intracranial bypass.

12. Can carotid duplex scanning or computed tomographic angiography (CTA)

replace angiography for detection of vascular injuries in penetrating neck

injuries?

With experienced operators, carotid duplex scanning approaches 100% sensitivity for

excluding zone II and III vascular injuries in stable, asymptomatic patients with penetrating

neck injuries. Because carotid duplex scanning has a lower specificity (85%–95%), positive

carotid duplex scanning should be followed by carotid angiography before making a decision

regarding surgical intervention.

In recent studies using multidetector helical CT scanners, CTA had sensitivities of 90% to

100%, a specificity of 100%, a positive predictive value of 100%, and a negative predictive

value of 98% in detecting carotid artery injuries. The limitations and pitfalls of the helical CTA

include artifacts produced by the shoulders of large patients or by bullet fragments and other

metallic foreign bodies. Streak artifacts can simulate an intimal tear. In cases with inadequate

studies or doubtful CTA results, the study should be considered nondiagnostic, and the

patients must undergo conventional angiography. CTA examinations have only a 1.1%

reported incidence of nondiagnostic results.

13. What diagnostic testing is preferred in detection of blunt vascular injuries?

n

Blunt vascular injuries were found in 27% of high-risk patients screened for blunt

vascular injury (combination of injury mechanism [cervical hyperextension or

hyperflexion, direct cervical blow, near-hanging] and injury pattern [carotid canal,

midface, and cervical spine fracture]). Angiography is the study of choice in acutely

injured and symptomatic patients. Of lesions, 90% occur at the bifurcation of carotids

or higher. Four-vessel angiography is recommended because multiple vessel injuries

occur in 40% to 80%. With the improved sensitivity of CT, angiography is shifting to a

therapeutic role.

n

The diagnostic accuracy of CTA has improved with the use of better CT technology. Using a

16 slice CT, Eastman found that CTA had a 97% sensitivity and 100% specificity. CTA has

been shown to decrease significantly the time to diagnose the injury.

n

Color flow Doppler ultrasound provides rapid identification and quantification of arterial

dissection, but it is unable to assess distal upper extracranial and intracranial internal

carotid artery and is operator dependent. With an experienced operator, ultrasound can be

used as a screening test in lower-risk patients.

n

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) accurately detects carotid and vertebral artery

injuries with a sensitivity and specificity greater than 95% for carotid artery dissection. It is

ideal for follow-up or for stable patients; MRA is difficult to perform in an acutely injured

unstable patient.

14. What is the appropriate management of blunt vascular injuries?

Carotid and vertebral artery dissections causing neurologic deficits should be treated with

endovascular stent-placement. Asymptomatic dissections are at risk for extension of the

dissection and thromboembolic events but often heal with observation and anticoagulation

therapy alone.

Chapter 85 NECK TRAUMA 595

15. Which diagnostic studies are important in suspected laryngeal injuries?

n

Soft-tissue cervical radiographs may show a fractured larynx, subcutaneous air, or

prevertebral air.

n

CT accurately identifies the location and extent of laryngeal fractures. CT should be done

when the diagnosis of a laryngeal fracture is still suspected despite a negative examination

of the endolarynx or when flexible laryngoscopy cannot be done (e.g., intubated patient).

n

Flexible laryngoscopy provides valuable information regarding the integrity of the

cartilaginous framework and the function of the vocal cords.

16. Are diagnostic studies necessary in suspected esophageal injuries?

Yes. Soft-tissue cervical radiographs may show subcutaneous emphysema or an increased

prevertebral shadow. Chest radiograph findings include pleural effusion, pneumothorax,

mediastinal air, and mediastinal widening. Esophageal contrast studies should be done initially

with radiopaque contrast medium (Gastrografin); if negative, studies should be repeated with

barium to increase diagnostic yield. Radiographic imaging is difficult because of the high

false-negative rate. Esophagography has a 30% to 50% false-negative rate and should be

followed by esophagoscopy in patients with suspected esophageal injury. Rigid endoscopy is

more sensitive than flexible endoscopy. No one study can exclude esophageal perforation; a

combination of physical signs, plain and contrast radiographs, and esophagoscopy should be

used to make the diagnosis. Isolated esophageal injuries after blunt injury are extremely rare.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Biffl WL, Moore EE: Identifying the asymptomatic patient with blunt carotid arterial injury. J Trauma

47:1163–1164, 1999.

2. Demetriades D, Theodorou D, Cornwell E, et al: Evaluation of penetrating injuries of the neck: prospective

study of 223 patients. World J Surg 21:47–48, 1997.

3. Deshaies EM, Nair AK, Boulos AS, et al: Blunt traumatic injuries to the carotid and vertebral arteries of the

neck and skull base. Contemp Neurosurg 30:1–6;2008.

4. Eastman AL, Chason DP, Perez CL, et al: Computed tomographic angiography for the diagnosis of blunt

cervical vascular injury: is it ready for prime time? J Trauma 60:925–9, 2006.

5. Fry WR, Dort JA, Smith RS, et al: Duplex scanning replaces arteriography and operative exploration in the

diagnosis of potential cervical vascular injury. Am J Surg 168:693–695, 1994.

6. Knaut AL, Kendall JL: Penetrating neck trauma. In Wolfson AB, Hendey GW, Hendry PL, et al, editors: Clinical

practice of emergency medicine, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2005, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, pp 956–962.

7. LeBlang SD, Nunez DB: Noninvasive imaging of cervical vascular injuries. Am J Roentgenol 175:1269–1278, 2002.

8. Múnera F, Cohn S, Rivas LA: Penetrating Injuries of the neck: use of helical computed tomographic

angiography. J Trauma 58:413–418, 2005.

9. Múnera F, Soto JA, Palacio D, et al: Diagnosis of arterial injuries caused by penetrating trauma to the neck:

comparison of helical CT angiography and conventional angiography. Radiology 216:356–362, 2000.

10. Schaider JJ, Bailitz J: Neck trauma: don’t put your neck on the line. Emerg Med Pract 5:1–23, 2003.

11. Tishman SA, Bokhari F, Collier B, et al: Clinical practice guideline: penetrating zone II neck trauma. J Trauma

64:1392–1405; 2008.

12. Weitzel N, Kendall JL, Pons P: Blind nasotracheal intubation for patients with penetrating neck trauma. J Trauma

56.1097–1101, 2004.

596

CHAPTER 86

CHEST TRAUMA

Susan Brion, MD, MS, and Justin C. Chang, MD

1. What is the initial approach to the patient with chest trauma?

Specific life-threatening conditions should be suspected based on mechanism of injury. Key

injuries that should be diagnosed and treated during the initial standard survey include airway

obstruction, tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, massive hemothorax, open

pneumothorax, and flail chest.

n

Inspection. Completely undress the patient and visually inspect the entire chest,

which necessitates rolling over a supine patient. Look for a flail chest (paradoxical

movement of the chest wall) and sucking chest wounds. Identify the exact location,

number, and type (i.e., penetrating or blunt) of wounds. Look for distended neck veins,

swollen face or neck (indicating damage to the mediastinum or underlying subcutaneous

emphysema).

n

Auscultation. Initial auscultation should focus on the axillae where breath sounds are

most readily heard. If breath sounds are equal bilaterally, the major bronchi are

probably intact. Listen for diminished or absent breath sounds and bowel sounds in the

chest. The presence of bowel sounds high in the chest may be the first indication of

diaphragmatic injury. Decreased breath sounds usually indicate pneumothorax or

hemothorax, although in an intubated patient this may also occur with the endotracheal

tube being in too deep. Bony crepitus indicates a rib or sternal fracture with the

potential for intrathoracic injury.

n

Palpation. It is important to palpate the chest wall gently at first to detect bony crepitus

and subcutaneous emphysema. Crepitus indicates a major blow to the chest with rib

fractures and the potential for underlying organ damage (e.g., pulmonary contusion), and

subcutaneous emphysema, depending on location, indicates pneumothorax or

pneumomediastinum.

2. What is the differential diagnosis for blunt versus penetrating chest

trauma?

n

Blunt injury: Simple pneumothorax, tension pneumothorax, hemothorax, rib fractures, flail

chest, sternal fracture, pulmonary contusion, pneumomediastinum, cardiac contusion/blunt

myocardial injury, and aortic injury.

n

Penetrating injury: Open pneumothorax, cardiac and great vessel injury

3. What is the best way to diagnose simple pneumothorax?

Recent literature supports the use of bedside transthoracic ultrasound in the hands of

experienced emergency medicine physicians as a superior modality for the diagnosis of

pneumothorax in comparison to plain chest X-ray, particularly in the supine patient. If plain

chest X-ray is used, a posterior-anterior (PA) film in full expiration should be used to detect a

small pneumothorax. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax remains the gold standard for

diagnosis.

4. When is a pneumothorax likely to cause severe symptoms?

Severe symptoms may be seen if the pneumothorax is greater than 40% of the hemithorax

(approximately 2.5 cm from the chest wall in an adult), in patients with shock or pre-existing

cardiopulmonary disease, or if it is a tension pneumothorax.

Chapter 86 CHEST TRAUMA 597

5. How is tension pneumothorax diagnosed?

Tension pneumothorax is a clinical rather than radiographic diagnosis. Clinical signs include

dyspnea, distended neck veins, diminished or absent breath sounds on the affected side,

tracheal deviation to the opposite side, hyperresonance to percussion, and hyperexpansion of

the chest wall on the affected side. If hypotension is present, jugular venous distention may

not be noted. Tachycardia, absent breath sounds, and hypotension are the most reliable and

easiest to appreciate signs of tension pneumothorax. If a chest X-ray is obtained, a

hyperlucent, overexpanded hemithorax with an evident pneumothorax and a mediastinal shift

to the opposite side would be observed.

6. What is the treatment for tension pneumothorax?

If tension pneumothorax is suspected, immediate reduction of the intrapleural pressure by

placement of a 14-gauge intravenous catheter over the fourth or fifth rib in the midaxillary

line, followed by aspiration with a 50-mL syringe, will convert the tension pneumothorax into

an open pneumothorax. This should be followed immediately by a tube thoracostomy after

vital signs improve. Lack of improvement following decompression indicates another cause of

hypoperfusion should be sought immediately.

1. Tension pneumothorax should be a clinical diagnosis.

2. Tachycardia, absent breath sounds, and hypotension are the most reliable means of diagnosis.

3. Immediately decompress the chest with a 14-gauge intravenous catheter whenever tension

pneumothorax is suspected.

4. Look for other sources of hypotension if there is no immediate improvement after

decompression.

KEY POINTS: TENSION PNEUMOTHORAX

7. What is the definition of massive hemothorax?

Massive hemothorax in an adult is defined as 1500 mL or more, about two thirds of the

available space in the hemithorax, occupied by blood. Patients with hemothorax will

occasionally continue to bleed. If there is evidence of ongoing hemorrhage after initial

drainage exceeding 600 mL over 6 hours, a massive hemothorax equivalent is diagnosed.

8. What is flail chest?

A flail chest occurs when a segment of the chest wall becomes unattached from the rest of the

chest. It occurs in one of three settings:

n

Two or more ribs are broken in two or more places.

n

More than one rib is fractured in association with costal cartilage disarticulation.

n

The costal cartilages on both sides of the sternum are disarticulated, resulting in a sternal

or central flail segment.

The significance of a flail chest lies in the tremendous force that caused it and the near

certainty of associated intrathoracic injuries.

9. What is the treatment for flail chest?

The primary treatment should be supportive, including analgesia, coughing, chest

physiotherapy, prevention of fluid overload, and subsequent pulmonary edema. If the patient

is in respiratory distress either clinically or as indicated by blood gas analysis or oxygen

saturation measurements, intubation and positive-pressure ventilation should be initiated.

Indications for early ventilatory support include shock, three or more associated injuries,

severe head injury, comorbid pulmonary disease, fracture of eight or more ribs, and age older

than 65 years.