Markovchick Vincent J., Pons Peter T., Bakes Katherine M.(ed.) Emergency medicine secrets. 5th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chapter 91 MUSCULOSKELETAL TRAUMA AND CONDITIONS OF THE EXTREMITY628

40. What is a locked knee? What are the most common causes?

The patient is unable to extend the knee actively or passively beyond 10- to 45-degree flexion.

True locking and unlocking occur suddenly. The most common causes are a tear of the medial

meniscus, a loose body or joint mouse (osteochondral fragment) in the knee, or a dislocated

patella.

41. What injuries are associated with a calcaneal fracture?

Depending on the exact mechanism of injury and the type of calcaneal fracture, 10% to 50%

of patients have an associated compression fracture of the lumbar or lower thoracic spine. Of

calcaneal injuries, 10% are bilateral, and about 25% are associated with other lower extremity

injuries; 10% can result in a compartment syndrome of the foot, requiring fasciotomy.

42. What is the most common direction of a tibiofemoral knee dislocation?

Anterior (the tibia’s relationship to the femur). The mechanism of an anterior knee dislocation

is hyperextension of the knee. There is a 30% to 50% chance of a popliteal artery injury

following this type of dislocation.

43. What direction is considered the irreducible knee dislocation?

Posterolateral (the tibia is posterolateral to the femur). The medial femoral condyle produces a

dimple sign as it buttonholes through the anteromedial joint capsule becoming entrapped. An

open reduction in the operating room is required.

44. What vascular injury must be considered with a tibiofemoral knee

dislocation?

Injury or compression of the popliteal artery. Cadaver studies showed that anterior

dislocations tend to cause intimal flaps and occlusion, whereas posterior dislocations are

more likely to cause a rupture of the popliteal artery. Injuries also occur at the trifurcation just

distal to the popliteal fossa. Postreduction angiography should be considered for all patients

with abnormal distal pulses or ankle-brachial index.

45. How is the ankle-brachial index (ABI) calculated?

ABI 5 Doppler systolic arterial pressure in the injured limb (ankle)

Doppler systolic arterial pressure in uninjured limb (brachial)

An ABI value of 0.9 is considered normal. The ABI measurement may be inaccurate in

patients with risk factors for peripheral arterial disease, such as diabetes and hypertension.

Vessel calcification in the elderly can also increase the risk of a false-positive result.

PEDIATRIC ORTHOPEDICS

46. What is a torus or buckle fracture?

This fracture is typically seen in the metaphysis of the radius but is not limited to this

bone. Torus means a round swelling or protuberance. In children, the cortical bone and

metaphyseal bone fail in compression (buckling), while the opposite cortex remains

intact. The area of bone that fails in compression forms a torus. Because the opposite

cortex remains intact, these fractures are stable and require splint or cast immobilization

for 4 weeks.

47. What is a greenstick fracture?

Children’s bones have increased elasticity. An angular force applied to a long bone of a child

causes a greenstick fracture. One cortex fails in tension, while the opposite cortex bows but

does not fail or fracture in compression. The fracture is similar to what occurs when one

attempts to break a green branch of a tree. This fracture pattern is common in the radius and

ulna. These fractures require reduction, and often the fracture must be completed to achieve

an adequate reduction. Immobilization in a cast is required for 6 weeks.

Chapter 91 MUSCULOSKELETAL TRAUMA AND CONDITIONS OF THE EXTREMITY 629

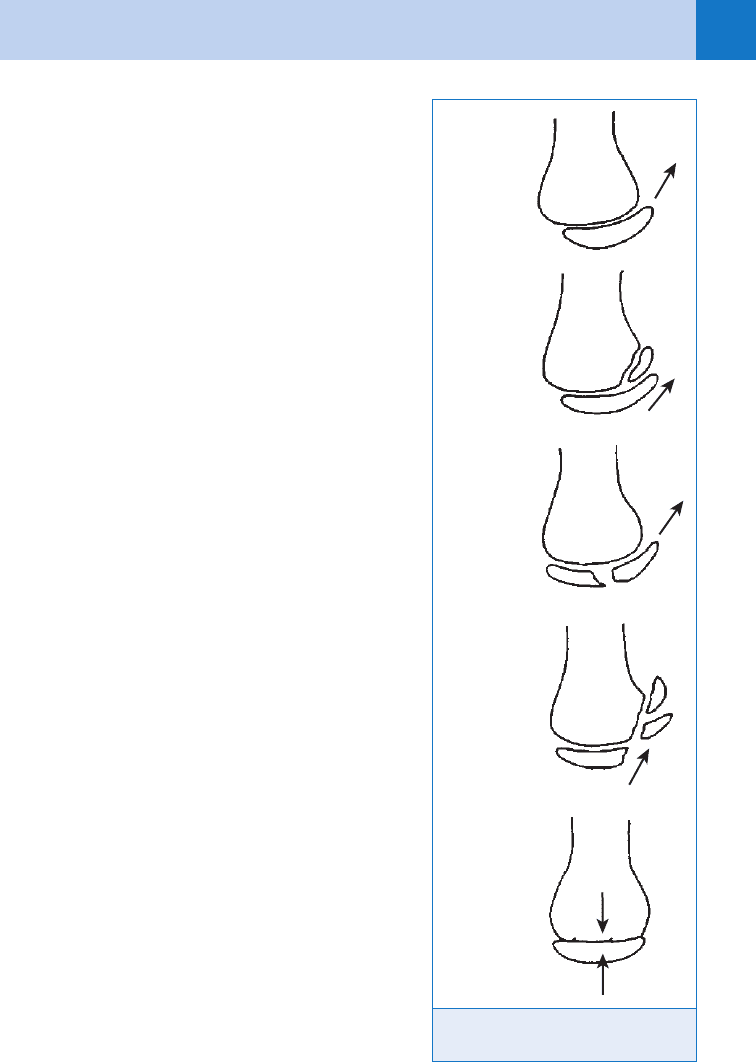

48. What is the Salter-Harris classification?

What is its clinical significance?

A method of classifying epiphyseal injuries

(Fig. 91-1). Fractures involving the epiphysis

may result in growth disturbance, and parents

must be informed of this potential. About 80%

of these injuries are Salter-Harris types I and

II, both of which have a low complication rate.

Salter-Harris types III, IV, and V injuries have a

more variable prognosis. Displaced Salter-

Harris types III and IV fractures may require

open reduction to restore the normal

relationship of the epiphysis and articular

surface. The five types are summarized as

follows:

n

Type I: Fracture extends through the

epiphyseal plate, resulting in displacement of

the epiphysis (this may appear merely as

widening of the radiolucent area representing

the growth plate).

n

Type II: Fracture is as above, with an

additional fracture of a triangular segment of

metaphysis.

n

Type III: Fracture line runs from the joint

surface through the epiphyseal plate and

epiphysis.

n

Type IV: Fracture line also occurs in type III

but also passes through adjacent metaphysis.

n

Type V: A crush injury of the epiphysis

occurs, which may be difficult to determine

by x-ray examination.

49. Describe the vascular complications

associated with pediatric supracondylar

humerus fractures.

Displaced supracondylar humerus fractures in

children have a 5% incidence of vascular

compromise. The brachial artery typically is

compressed or lacerated by the anteriorly

displaced humeral shaft. Posterior lateral

displacement of the supracondylar fracture is

the fracture pattern most likely to result in

vascular injury. The child with a viable hand

and absent pulse should undergo prompt

reduction and fracture fixation in the operating

room, with re-evaluation of the vascular status

after the procedure. In the patient with an

absent pulse and a devascularized hand,

longitudinal traction and splinting should be

done in the ED in an attempt to reconstitute

flow to the distal extremity. Prompt

consultation with orthopedic and vascular

surgeons is required.

Type I

Type II

Type III

Type IV

Type V

Figure 91-1. Salter-Harris classification

of epiphyseal injuries.

Chapter 91 MUSCULOSKELETAL TRAUMA AND CONDITIONS OF THE EXTREMITY630

50. Describe the neurologic complications associated with pediatric

supracondylar humerus fractures.

The anterior interosseous nerve (branch of the median nerve) is potentially the most

commonly injured nerve. This nerve innervates the deep compartment of the forearm, which

consists of the flexor digitorum profundus to the index, the pronator quadratus, and the flexor

pollicis longus. The nerve can be checked by evaluating flexor pollicis longus function at the

interphalangeal joint of the thumb. The radial nerve is the next most commonly injured nerve,

followed by the ulnar nerve. A thorough physical examination must be done to identify these

injuries, a difficult task in the small child.

KEY POINTS: MUSCULOSKELETAL TRAUMA AND CONDITIONS

OF THE EXTREMITY

1. Never place an amputated part directly on ice or immerse in water.

2. Bleeding from a wound is best controlled with direct pressure

3. Multidisciplinary approach is paramount in the treatment of pelvic hemorrhage.

4. Knee dislocations require a thorough vascular examination.

5. Always rule out infection in a child presenting with atraumatic hip pain.

6. In nonambulating children with humeral or femoral fractures, be suspicious of child abuse.

51. What is a nursemaid’s or pulled elbow? What is its management?

A longitudinal pull on the outstretched arm of a 1- to 5-year-old child may result in a

subluxation of the annular ligament over cartilaginous radial head. The child typically presents

with pseudoparalysis of the injured extremity. Radiographs are negative for fracture or radial

head dislocation. Reduction involves simultaneous supination of the forearm and flexion of the

elbow. A distinct click over the radial head signifies reduction. The child often begins to use

the extremity within minutes of reduction. The parent or caregiver should be educated to avoid

longitudinal traction on the arm to prevent this from occurring in the future.

52. Describe the potential implications of a humeral or femoral fracture in a small

child.

In the nonambulating child with these fractures, the suspicion of child abuse should be high.

An unwitnessed event or a history that does not correspond to the injuries is another potential

sign of abuse. Careful examination of the child should be done, looking specifically for skin

bruises or burns, retinal hemorrhage, and evidence of previous fracture. A skeletal survey

should be considered because the presence of fractures at different stages of healing is a

sign of abuse. All cases of suspected abuse need to be reported to the local authorities.

(See Chapter 65.)

53. What is Waddell’s triad?

The constellation of injuries in a child struck by a car:

n

Femoral fracture

n

Intrathoracic or intra-abdominal injury

n

Head injury

54. Which nontraumatic hip disorders cause a limp in a child?

n

Septic arthritis

n

Transient synovitis (ages 2–12 years)

n

Idiopathic avascular necrosis (boys, ages 5–9 years)

n

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) (boys, ages 10–16 years)

Chapter 91 MUSCULOSKELETAL TRAUMA AND CONDITIONS OF THE EXTREMITY 631

n

Perthes’ disease

n

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

All are uncommon. Transient synovitis is probably the most common cause of nontraumatic

limp in a child but is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Symptomatic treatment is prescribed for transient synovitis, including nonsteroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs and non-weight bearing or bed rest. Untreated or delayed treatment of

septic arthritis can lead to irreversible and catastrophic sequelae from permanent damage and

deformation of the articular cartilage. Infection in a child presenting with atraumatic hip pain

must be convincingly ruled out. The white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate,

and body temperature frequently are elevated in cases of infection. If doubt persists, the gold

standard is hip aspiration, usually done in the operating room. Standard anteroposterior and

lateral radiographs of the hip differentiate between Perthes’ disease and a slipped capital

femoral epiphysis.

55. What are the early radiographic findings of an SCFE?

Any asymmetry of the relationship of the femoral head to the femoral neck should raise the

suspicion of SCFE, even if evident on only one X-ray view. If anteroposterior and lateral

radiographs are normal, frog-leg views should be obtained. Comparison of the two hips may

not be helpful in discerning subtle changes because SCFE is bilateral in 20% of cases.

56. What is the ED management of a child with injury and tenderness over an

open epiphysis but a normal radiograph?

It is best to assume the child has sustained an undeterminable fracture of the physis

(Salter-Harris type I or V). Immobilize the joint in a posterior splint, and keep the child

non-weight bearing if the lower extremity is involved. Parents should be notified of the

possibility of this type of injury and the potential for growth disturbance. The need for

prompt follow-up must be emphasized and is best arranged before discharging the child

from the ED. A nondisplaced physeal fracture that becomes displaced because of lack of

immobilization can have significant long-term consequences. Short-term extremity

immobilization in an appropriately applied splint or cast is well tolerated. When in

doubt, immobilize.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Browner BD, Trafton PG, Green NE, et al, editors: Skeletal trauma: basic science, management, and

reconstruction, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2002, W.B. Saunders.

2. Burkhead WZ Jr, Rockwood CA Jr: Treatment of instability of the shoulder with an exercise program. J Bone

Joint Surg Am 68:724–731, 1986.

3. Green OP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC: Green’s operative hand surgery, ed 4, New York, 1999, Churchill

Livingstone.

4. Grotz MRW, Allami MK, Harwood P, et al: Open pelvic fractures: epidemiology, current concepts of

management outcome. Injury 1:1–13, 2005.

5. Lovell WW, Winter RB, Morrissy RT, et al: Lovell and Winter’s pediatric orthopaedics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2001,

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

6. Mills WJ, Barei DP, McNair P: The value of the ankle-brachial index for diagnosing arterial injury after knee

dislocation: a prospective study. J Trauma 56:1261–1265, 2004.

7. Pagnani MJ, Galinat BJ, Warren RF: Glenohumeral instability. In DeLee JC, Drez D Jr, editors: Orthopaedics

sports medicine: principles and practice. Philadelphia, 1994, WB Saunders, vol 1, pp 580–622.

8. Pollock RG, Bigliani LU: Recurrent posterior shoulder instability: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Orthop

291:85–96, 1993.

9. Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholz RW, et al: Rockwood and Green’s fractures in adults, ed 5, Philadelphia,

2001, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

10. Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholz RW, et al: Rockwood and Green’s fractures in children, ed 5, Philadelphia,

2001, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

632

HAND INJURIES AND INFECTIONS

CHAPTER 92

Michael A. Kohn, MD, MPP

1. Are hand problems important in emergency medicine?

Yes. Our hands are our interface to the mechanical world, so they are frequently injured or

exposed to infection. There are 4.8 million ED visits per year for hand/wrist injuries. At least

one of every eight injury-related ED visits is for a hand/wrist injury.

2. List the essential elements of the history.

n

Age

n

Dominant hand

n

Occupation

n

How, where, and when injury occurred

n

Posture of hand when injured

n

Tetanus status

n

Prior injury or disability of the hand

3. List the elements of a complete hand examination.

n

Initial inspection of skin and soft tissue

n

Vascular examination

n

Evaluation of tendon function

n

Nerve examination (motor and sensory)

n

Determination of joint capsule integrity

n

Skeletal examination

4. What is topographical anticipation?

Looking at the skin wound and thinking about which underlying structure (vessel, tendon,

nerve, bone, ligament, or joint) could be injured. Know the anatomy. Do not hesitate to consult

an atlas.

5. What is the normal posture of the hand at rest?

With the wrist in slight extension, the resting fingers normally assume a cascade, progressively

more flexed from index to small. (See this by relaxing your own hand with the wrist in slight

extension.) An alteration in the normal posture can lead to immediate diagnosis of major

tendon and joint injuries.

6. Does dorsal swelling always signify an injury or infection in the dorsum of the

hand?

No. Most of the palmar lymphatics drain to lymph channels and lacunae located in the loose

areolar layer on the dorsum of the hand. Always check for a palmar pathology when a patient

presents with dorsal swelling.

7. What is the Allen test? How is it performed?

The Allen test verifies patency of the radial and ulnar arteries as follows: Occlude radial

and ulnar arteries. Have patient open and close hand five or six times. Hand should blanch.

Release ulnar artery; blanching should resolve within 3 to 5 seconds. Repeat test, releasing

Chapter 92 HAND INJURIES AND INFECTIONS 633

radial artery instead of ulnar artery Blanching should resolve within 3 to 5 seconds. The most

accurate form of the Allen test uses digital blood pressures rather than return of color to monitor

reperfusion.

8. How is function of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendon tested?

The FDS inserts on the middle phalanx and flexes the proximal interphalangeal (PIP)

joint. The flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) inserts on the distal phalanx and flexes the

PIP and the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. The FDS muscle-tendon units should be

independent of one another, whereas the FDP tendons arise from a common muscle belly.

Testing the FDS of a finger entails flexing it at the PIP joint, while stabilizing the other

three fingers in full extension, thereby taking the FDP out of action as a potential flexor of

the PIP joint.

9. In which finger is the test of FDS function unreliable?

Because the FDP to the index finger can be independent of the other profundi, the FDS test

is unreliable in the index finger. Flexion at the PIP joint may be due to the FDP, even with

the other fingers stabilized in extension. Suspected index finger FDS injuries must be

explored.

10. Why is the flexor or palmar aspect of the hand called the OR side, whereas

the extensor or dorsal aspect is the ED side?

In contrast to the extensors, the flexor tendons run through delicate sheaths. Because of these

sheaths, repairing flexor tendons requires more expertise and a more controlled environment

in the operating room than repairing extensor tendons does.

11. How is a partial tendon laceration diagnosed?

If the location of the skin laceration is suspicious, rule out an underlying partial tendon

laceration by exploration and direct visualization under tourniquet hemostasis. Because a

flexor tendon runs through its sheath like a piston through a cylinder, a sheath laceration

implies a partial tendon laceration, which is visible only when the hand is in the same posture

as when injured. A bloodless field and direct visualization of the tendon during full range of

motion must occur to rule out a partial tendon laceration. All wounds over tendons must be

explored for partial tendon lacerations since range of motion test can still be normal. Never

test for tendon integrity against resistance since a partial tendon laceration can be converted

to a complete (100%) laceration.

12. How do I test the extrinsic extensor tendons?

The extrinsic extensors alone extend the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, whereas they

combine with tendons from the interossei and lumbricals to form the extensor mechanism

that extends the interphalangeal joints. To test the extrinsic extensor, ensure that the patient

can extend at the MCP joint (but see below).

13. Can extensor function to a finger be intact despite complete laceration of the

extensor digitorum communis (EDC) to that finger?

Yes. The juncturae tendinum interlink the EDC tendons at the midmetacarpal level. Even if the

EDC to a finger is completely lacerated in the dorsum of the hand, extension at the MCP still

may be possible because of the junctura.

14. How do I test sensory nerve function?

Assess nerve function before the use of anesthesia. Test digital nerves by checking two-point

discrimination on the volar pad. The two points should be 5 mm apart and aligned

longitudinally.

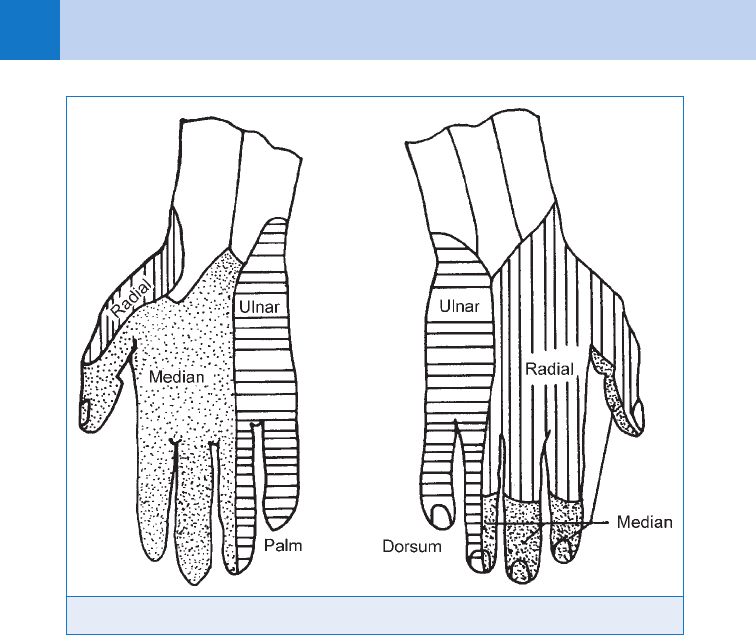

15. What are the sensory distributions of the median, ulnar, and radial nerves?

See Fig. 92-1.

Chapter 92 HAND INJURIES AND INFECTIONS634

Figure. 92-1. Sensory distributions of the median, ulnar, and radial nerves.

16. How is motor function of the median, ulnar, and radial nerves tested?

n

Median: Abductor pollicis brevis (APB)—abducts the thumb against resistance while

palpating the APB muscle belly.

n

Ulnar: First dorsal interosseous—abducts the index finger against resistance.

n

Radial (no intrinsics): Extensor pollicis longus (EPL)—extends the thumb interphalangeal

joint against resistance.

17. Which is the most frequently dislocated carpal bone?

The carpal bones from radial to ulnar side are as follows:

n

Proximal row—scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, pisiform

n

Distal row—trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, hamate

The lunate is most frequently dislocated. Its blood supply comes through the volar and dorsal

ligaments from the radius. If both ligaments are ruptured, avascular necrosis results.

18. Which is the most frequently fractured carpal bone?

The scaphoid. Its distal blood supply increases the likelihood of avascular necrosis in the

proximal segment after fracture.

19. What is the classic sign of a scaphoid fracture?

Snuffbox tenderness. Even without radiographic evidence of a fracture, the patient with

tenderness to palpation of the anatomic snuffbox gets a thumb spica splint and must have a

repeat radiograph in 2 weeks.

20. How do I control hemorrhage from a hand injury?

Direct pressure and elevation. This will work 99.9% of the time. Elevate and hold pressure for 10

minutes by the clock. Very rarely, an incomplete arterial laceration requires a proximal tourniquet

Chapter 92 HAND INJURIES AND INFECTIONS 635

for temporary control, followed by sensory examination, anesthesia, irrigation, and exploration

under good light and magnification to tie off the bleeding vessel. Never blindly clamp a bleeder.

21. Why the rule, no blind clamping of bleeders?

In the hand, the arteries run in close approximation to the nerves. Blindly clamping an artery

may irreparably damage the associated nerve. Also, the clamp may damage a section of vessel

vital to successful reanastomosis. All hand bleeding can be controlled by direct pressure or a

tourniquet.

22. What should be done with an amputated digit?

Gently clean the digit with sterile saline, wrap it in moist gauze, place it in a sterile container,

and float the container in ice water. (Avoid direct contact between ice and tissue to prevent

freezing.)

23. What should be done with a devascularized but still partially attached digit?

Leave part attached (preserves veins for reimplantation), gently wrap in moist gauze, and

apply a bulky dressing.

24. What are the indications and contraindications for reimplantation?

n

Indications: Multiple finger injury; thumb amputations (especially proximal to

interphalangeal joint); single finger injury in children; clean amputation at hand, wrist,

or distal forearm.

n

Contraindications: Severe crush or avulsion, heavy contamination, single-finger

amputations in adults, severe associated medical problems or injuries, severe multilevel

injury of amputated part, willful self-amputation. Bottom line: Give the hand surgeon the

opportunity to decide.

25. Which are the most deceptive of all serious hand injuries?

High-pressure injection injuries (from paint guns, grease guns, or hydraulic lines) initially

may seem innocuous, often involving just the fingertip. In one published case series, 6 out of

15 high-pressure injection injuries resulted in some form of amputation, and only one patient

regained normal sensation, despite aggressive early surgical treatment.

26. List Kanavel’s four cardinal signs of flexor tenosynovitis.

n

Slightly flexed posture of the digit

n

Fusiform swelling of the digit

n

Pain on passive extension

n

Tenderness along the flexor tendon sheath

Flexor tenosynovitis requires admission and surgery.

27. What is a paronychia? How is it treated?

A common bacterial infection involving the folds of skin that hold the fingernail in place. In the

absence of visible pus, treatment should consist of warm moist compresses, elevation, and

antistaphylococcal antibiotics. If pus is present, do the minimum necessary to drain and

maintain drainage. This usually consists of simply elevating the eponychial fold or making a

small incision. Sometimes removal of a longitudinal section of the nail plate is necessary.

28. How is whitlow different from a paronychia?

Whitlow is infection of the tissue around the nail plate with herpes simplex virus (rather than

bacteria). The discharge is serous and crusting rather than purulent. The patient also may

have perioral cold sores. Do not incise and drain herpetic whitlow.

29. What is a felon? How is it treated?

A painful and potentially disabling infection of the fingertip pulp. Treatment is controversial.

Some clinicians argue for immediate drainage of the tensely swollen and painful fingertip pad.

Others argue that early treatment with antibiotics, elevation, and immobilization may prevent

Chapter 92 HAND INJURIES AND INFECTIONS636

the need for surgical drainage. Even if drainage is necessary, the best method is also a matter

of controversy. The full fishmouth incision has fallen out of favor, but the three-quarter

fishmouth incision and the simple lateral incision are both acceptable.

30. What is a football jersey finger? How is it treated?

Rupture of the FDP occurs commonly when a football player catches his finger in an

opponent’s jersey. The tendon is avulsed from its insertion at the palmar base of the distal

phalanx, often taking a bone fragment along. Surgical repair within the next several days is

indicated.

31. What is a mallet finger? How is it treated?

A mallet finger is the opposite of a football jersey finger; the insertion of the extensor tendon,

rather than the flexor tendon, is avulsed from the dorsum of the distal phalanx, often pulling

off a bone fragment. Appropriate treatment is to splint the DIP joint in extension (not

hyperextension) for 6 weeks.

32. Describe a subungual hematoma. How is it treated?

A collection of blood under the nail plate can be painful. Classically, this occurs when a

weekend carpenter strikes his or her thumb with a hammer. Relieving the pressure by nail

trephination (poking a hole in the nail) will make you a hero to the patient. Use electrocautery,

a red-hot paperclip, or an 18-gauge needle (twisting it between your fingers like a drill bit).

Removal of an intact nail plate is almost never indicated.

33. What is a gamekeeper’s thumb? How is it diagnosed?

A torn ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb MCP joint resulting from forceful abduction of

the thumb. In 1955, the injury was reported in 24 Scottish game wardens, arising from

their technique for breaking the necks of wounded rabbits. The injury is more properly

called skier’s thumb because it most commonly occurs when a skier either catches the

thumb on a planted ski pole or falls while holding a pole in the outstretched hand. The

injury is potentially severely disabling. Complete rupture of the ligament always requires

surgery. ED treatment consists of a thumb spica splint and referral. One way to test for

injury to the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb MCP is to hand the patient a heavy can

(e.g., of soda) or bottle (e.g., of hydrogen peroxide). If the injury is present, the patient

will be unable to hold the object in the usual way, either supinating to balance the object in

the palm or dropping it.

34. What is a boxer’s fracture?

Fracture of the fifth (small finger) metacarpal is common in barefisted pugilists. Because

the small finger metacarpal is second only to the thumb metacarpal in mobility, large

angles of angulation are tolerated without functional deficit. Nevertheless, attempts to

correct significant angulation of an acute boxer’s fracture are warranted. Any rotational

deformity must be corrected. A laceration accompanying a boxer’s fracture is assumed to

be a fight bite.

35. What is a fight bite?

The most notorious of all nonvenomous bite wounds is the fight bite. As the name implies,

the injury occurs when the soon-to-be-patient punches his or her adversary in the teeth,

lacerating the dorsum of one or more MCP joints. Other names for this injury such as

morsus humanus or closed fist injury have been proposed. Fight bite is more compact,

descriptive, and poetic. All such wounds require formal exploration, including extension of

the skin laceration if necessary. They should be débrided, irrigated, dressed open (no

sutures), and splinted. If the wound penetrates the extensor hood, the MCP joint requires

thorough washout, and strong consideration should be given to hospitalization for

intravenous (IV) antibiotics and meticulous wound care. If the wound is already infected,

hospitalization is mandatory.

Chapter 92 HAND INJURIES AND INFECTIONS 637

KEY POINTS: HAND INJURIES AND INFECTIONS

1. Because scaphoid fractures are frequently radiographically occult, even without X-ray

evidence of a fracture, the patient with tenderness to palpation of the anatomic snuffbox

should be treated with a thumb spica splint and repeat evaluation in 1 to 2 weeks.

2. The most deceptive of serious hand injuries is the high-pressure injection injury sustained

while testing a hydraulic paint or oil gun because, despite seeming innocuous on initial

presentation, these injuries require aggressive, surgical management.

3. Any laceration over the dorsal MCP joint is suspicious for a fight bite. Fight bites require

meticulous exploration and wound care. If the wound penetrates the extensor hood,

thorough joint washout and IV antibiotics are required.

36. Are human bites more dangerous than other animal bites?

No. The fight bite gave human bites their reputation for being more prone to infection than

other animal bites. This probably has more to do with the location of the bite and the typical

delay in treatment than with the mix of organisms in the human mouth. True human bites

(occlusive bites rather than fight bites) have no higher infection rates than animal bites.

If humans punched animals in the teeth, these animal fight bites would have high infection

rates also.

37. Name six true hand emergencies.

n

Amputation or other devascularization injury

n

Compartment syndrome

n

Third-degree and circumferential burns

n

High-pressure injection injury

n

Flexor tenosynovitis

n

Septic joint

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. American Society for Surgery of the Hand: The hand: examination and diagnosis. Blue book, ed 3, New York,

1990, Churchill Livingstone.

2. American Society for Surgery of the Hand: The hand: primary care of common problems. Red book, ed 2,

New York, 1985, Churchill Livingstone.

3. Cambell CS: Gamekeeper’s thumb. J Bone Joint Surg 37B:148–149, 1955.

4. Carter PR: Common hand injuries and infections: a practical approach to early treatment. Philadelphia, 1983,

W.B. Saunders.

5. Christodoulou L, Melikyan EY, Woodbridge S, et al: Functional outcome of high-pressure injection injuries of

the hand. J Trauma 50:717–720, 2001.

6. Daniels JM II, Zook EG, Lynch JM: Hand and wrist injuries. Part II: Emergent evaluation. Am Fam Physician

69:1949–1956, 2004.

7. Kanavel AB: Infection of the hand. Philadelphia, 1925, Lea & Febiger.

8. Lampe EW (with illustrations by F. Netter): Surgical anatomy of the hand. Clin Symp 403, 1988.

9. Perron AD, Miller MD, Brady WJ: Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: fight bite. Am J Emerg Med 20:114–117, 2002.