McConnell Campbell R., Brue Stanley L., Barbiero Thomas P. Microeconomics. Ninth Edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

In the long run an industry and the individual firms it comprises can undertake all

desired resource adjustments. That is, they can change the amount of all inputs

used. The firm can alter its plant capacity; it can build a larger plant or revert to a

smaller plant than that assumed in Table 8-2. The industry also can change its plant

size; the long run allows sufficient time for new firms to enter or for existing firms

to leave an industry. We will discuss the impact of the entry and exit of firms to and

from an industry in the next chapter; here we are concerned only with changes in

plant capacity made by a single firm. Let’s couch our analysis in terms of average

total cost (ATC), making no distinction between fixed and variable costs because all

resources, and therefore all costs, are variable in the long run.

Firm Size and Costs

Suppose a single-plant manufacturer begins on a small scale and, as the result of

successful operations, expands to successively larger plant sizes with larger output

capacities. What happens to average total cost as this occurs? For a time, succes-

sively larger plants will lower average total cost. However, eventually the building

of a still larger plant may cause ATC to rise.

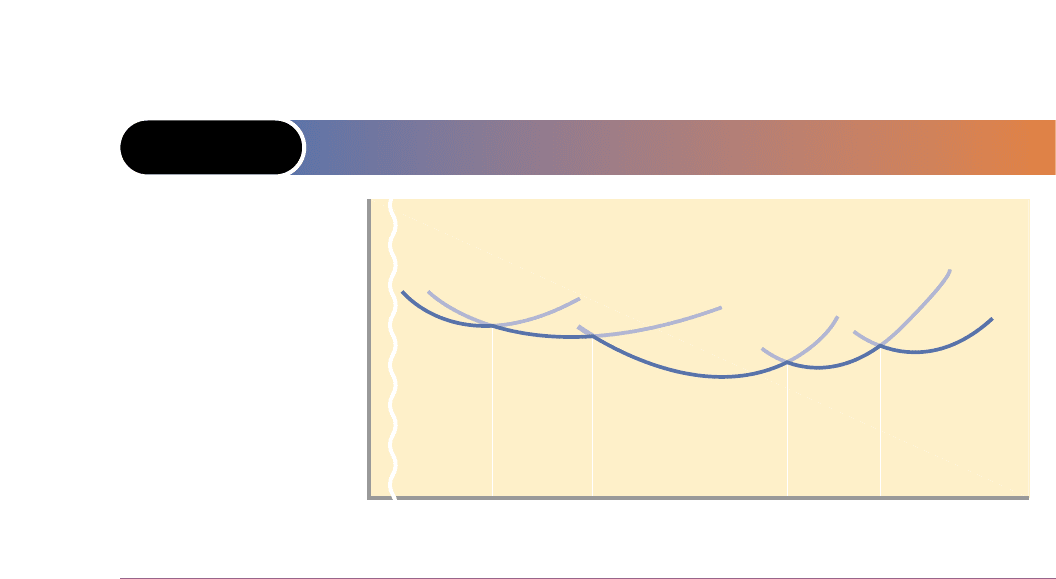

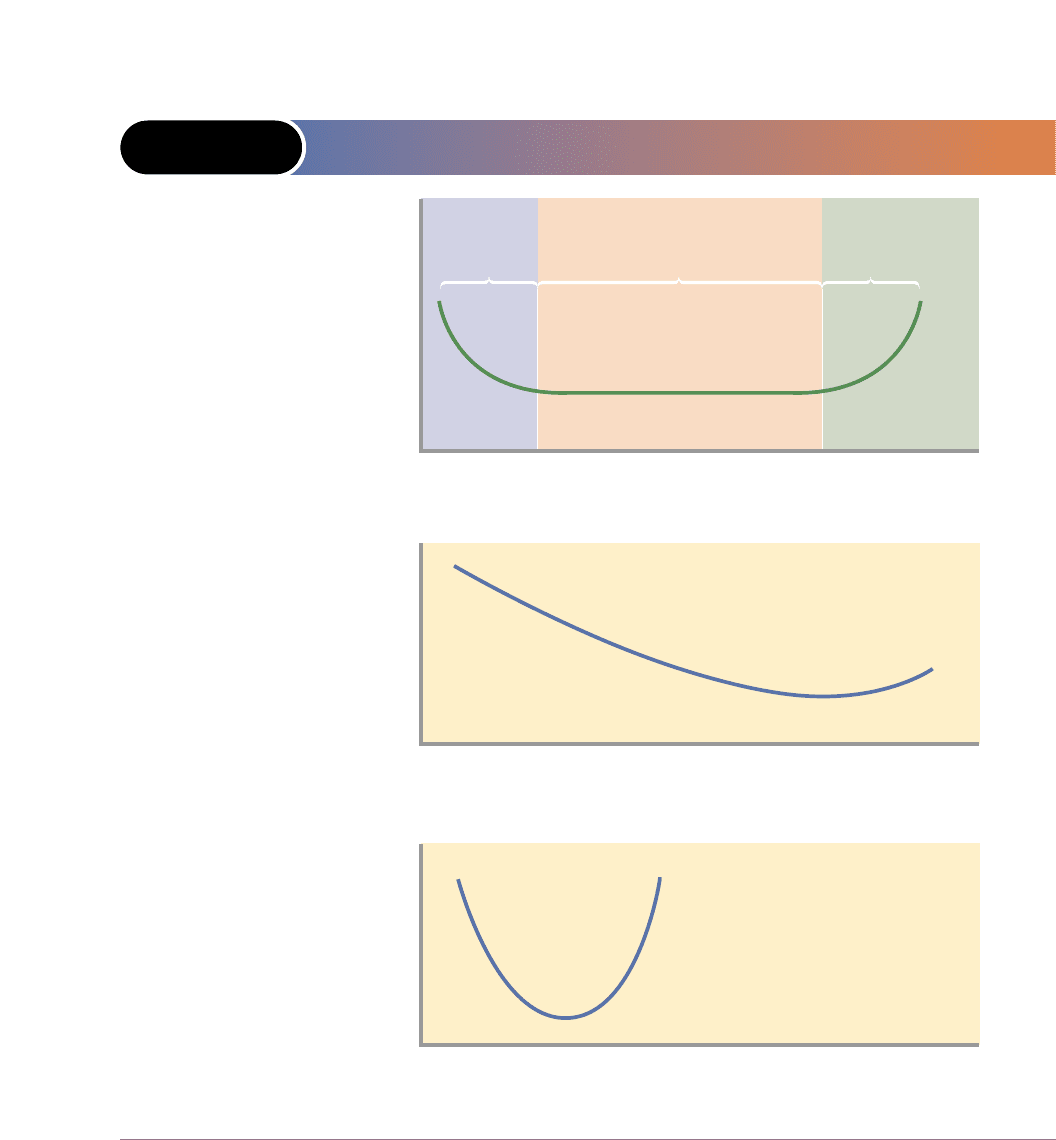

Figure 8-7 illustrates this situation for five possible plant sizes. ATC-1 is the short-

run average-total-cost curve for the smallest of the five plants, and ATC-5 the curve

for the largest. Constructing larger plants will lower the minimum average total

costs through plant size 3, but then larger plants will mean higher minimum aver-

age total costs.

The Long-Run Cost Curve

The vertical lines perpendicular to the output axis in Figure 8-7 indicate those out-

puts at which the firm should change plant size to realize the lowest attainable aver-

age total costs of production. These are the outputs at which the per-unit costs for a

larger plant drop below those for the current, smaller plant. For all outputs up to 20

units, the lowest average total costs are attainable with plant size 1. However, if the

firm’s volume of sales expands to between 20 and 30 units, it can achieve lower per-

unit costs by constructing larger plant size 2. Although total cost will be higher at

200 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

Long-Run Production Costs

● The law of diminishing returns indicates that,

beyond some point, output will increase by

diminishing amounts as more units of a variable

resource (labour) are added to a fixed resource

(capital).

● In the short run, the total cost of any level of

output is the sum of fixed and variable costs

(TC = TFC + TVC).

● Average fixed, average variable, and average

total costs are fixed, variable, and total costs

per unit of output; marginal cost is the extra

cost of producing one more unit of output.

● Average fixed cost declines continuously as out-

put increases; average-variable-cost and aver-

age-total-costs curves are U-shaped, reflecting

increasing and then diminishing returns; the

marginal-cost curve falls but then rises, inter-

secting both the average-variable-cost-curve

and the average-total-cost curve at their mini-

mum points.

<hadm.sph.sc.edu/

Courses/Econ/Cost/

Cost.html>

A tutorial on total

cost, fixed cost,

variable cost, and

marginal cost

the expanded levels of production, the cost per unit of output will be less. For any

output between 30 and 50 units, plant size 3 will yield the lowest average total costs.

From 50 to 60 units of output, the firm must build plant size 4 to achieve the lowest

unit costs. Lowest average total costs for any output over 60 units require construc-

tion of the still larger plant size 5.

Tracing these adjustments, we find that the long-run ATC curve for the enterprise

is made up of segments of the short-run ATC curves for the various plant sizes that

can be constructed. The long-run ATC curve shows the lowest average total cost at

which any output level can be produced after the firm has had time to make all appro-

priate adjustments in its plant size. In Figure 8-7 the dark blue, bumpy curve is the

firm’s long-run ATC curve or, as it is often called, the firm’s planning curve.

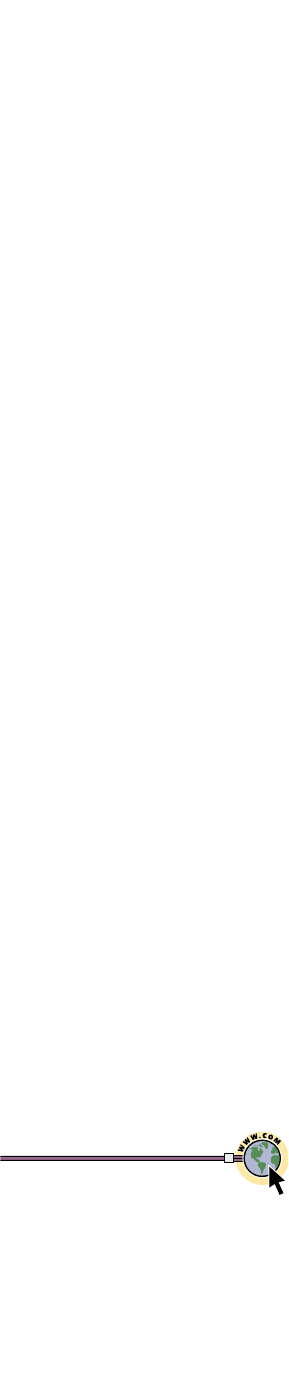

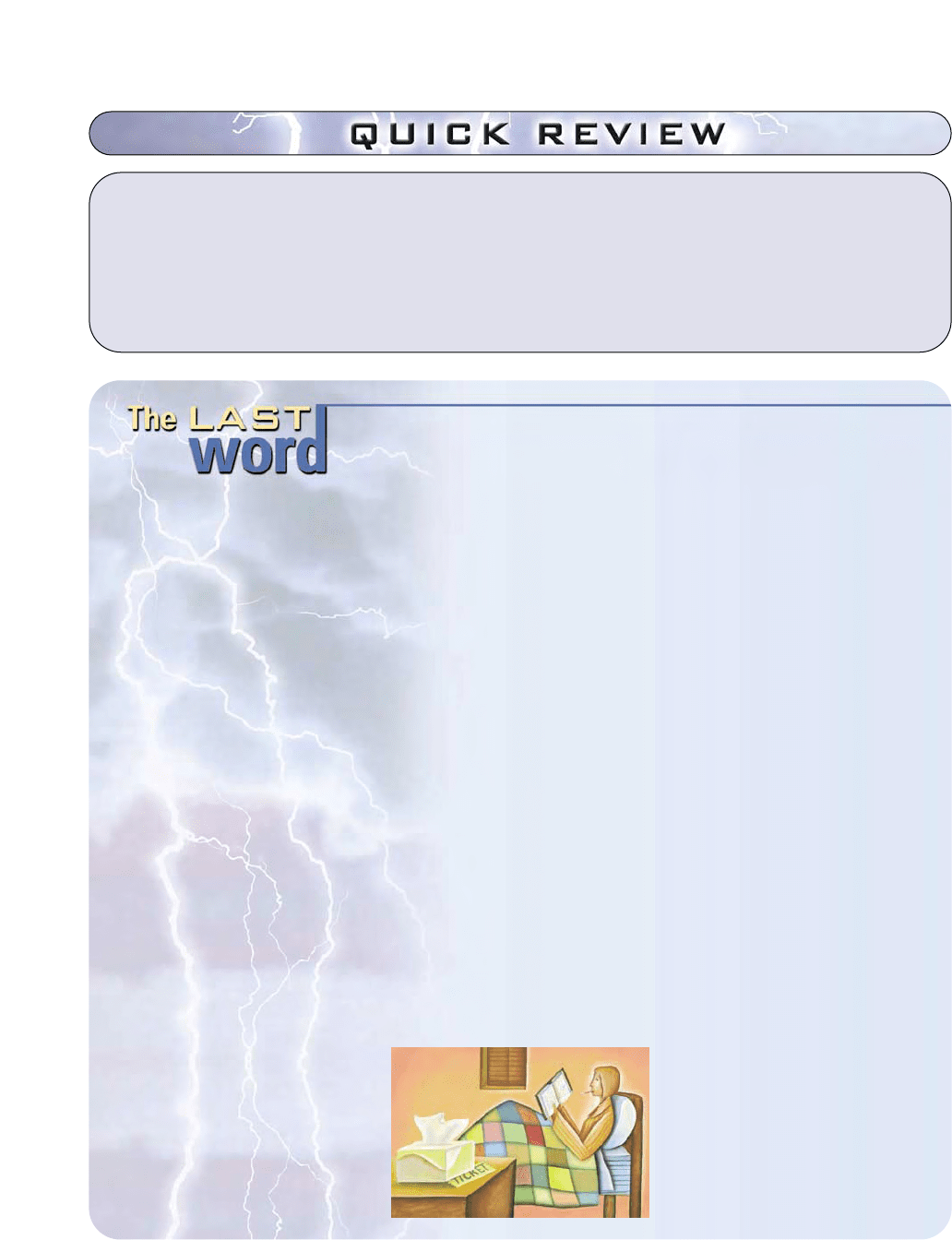

In most lines of production, the choice of plant size is much wider than in our

illustration. In many industries the number of possible plant sizes is virtually

unlimited, and in time quite small changes in the volume of output will lead to

changes in plant size. Graphically, this implies an unlimited number of short-run

ATC curves, one for each output level, as suggested by Figure 8-8 (Key Graph).

Then, rather than consisting of segments of short-run ATC curves as in Figure 8-7,

the long-run ATC curve is made up of all the points of tangency of the unlimited

number of short-run ATC curves from which the long-run ATC curve is derived.

Therefore, the planning curve is smooth rather than bumpy. Each point on it tells us

the minimum ATC of producing the corresponding level of output.

Economies and Diseconomies of Scale

We have assumed that for a time increasing plant sizes will lead to lower unit costs

but that beyond some point successively larger plants will mean higher average total

costs. That is, we have assumed that the long-run ATC curve is U-shaped. But why

should this be? Note, first, that the law of diminishing returns does not apply in the

long run because diminishing returns presumes one resource is fixed in supply, while

the long run means all resources are variable. Also, our discussion assumes resource

chapter eight • the organization and the costs of production 201

FIGURE 8-7 THE LONG-RUN AVERAGE-TOTAL-COST CURVE:

FIVE POSSIBLE PLANT SIZES

Average total costs

02030 5060

Q

Output

ATC-1

ATC-2

ATC-3

ATC-4

ATC-5

The long-run

average-total-cost

curve is made up of

segments of the

short-run cost curves

(ATC-1, ATC-2, etc.)

of the various-size

plants from which the

firm might choose.

Each point on the

planning curve shows

the least unit cost

attainable for any

output when the firm

has had time to make

all desired changes in

its plant size.

prices are constant. We can explain the U-shaped long-run average-total-cost curve

in terms of economies and diseconomies of large-scale production.

ECONOMIES OF SCALE

Economies of scale, or economies of mass production, explain the downsloping

part of the long-run ATC curve. As plant size increases, a number of factors will for

a time lead to lower average costs of production.

Labour Specialization Increased specialization in the use of labour becomes more

achievable as a plant increases in size. Hiring more workers means jobs can be

divided and subdivided. Each worker may now have just one task to perform

instead of five or six. Workers can work full time on those tasks for which they have

special skills. In a small plant, skilled machinists may spend half their time per-

forming unskilled tasks, leading to higher production costs.

Further, by working at fewer tasks, workers become proficient at those tasks. The

jack-of-all-trades doing five or six jobs is not likely to be efficient in any of them. By

concentrating on one task, the same worker may become highly efficient.

Finally, greater labour specialization eliminates the loss of time that accompanies

each shift of a worker from one task to another.

Managerial Specialization Large-scale production also means better use of, and

greater specialization in, management. A supervisor who can handle 20 workers is

underused in a small plant that employs only 10 people. The production staff could

be doubled with no increase in supervisory costs.

Small firms cannot use management specialists to best advantage. In a small plant

sales specialists may have to divide their time between several executive functions, for

example, marketing, personnel, and finance. A larger scale of operations means that

the marketing expert can supervise marketing full time, while specialists perform

other managerial functions. Greater efficiency and lower unit costs are the net result.

Efficient Capital Small firms often cannot afford the most efficient equipment. In

many lines of production such machinery is available only in very large and

extremely expensive units. Furthermore, effective use of the equipment demands a

high volume of production, and that again requires large-scale producers.

In the automobile industry the most efficient fabrication method in North Amer-

ica employs robotics and elaborate assembly line equipment. Effective use of this

equipment demands an annual output of perhaps 200,000 to 400,000 automobiles.

Only very large-scale producers can afford to purchase and use this equipment effi-

ciently. The small-scale producer is faced with a dilemma. To fabricate automobiles

using other equipment is inefficient and, therefore, more costly per unit. The alter-

native of purchasing the efficient equipment and underusing it at low levels of out-

put is also inefficient and costly.

Other Factors Many products entail design and development costs, as well as other

start-up costs, that must be incurred irrespective of projected sales. These costs

decline per unit as output is increased. Similarly, advertising costs decline per auto,

per computer, per stereo system, and per box of detergent as more units are produced

and sold. The firm’s production and marketing expertise usually rises as it produces

and sells more output. This learning by doing is a further source of economies of scale.

All these factors contribute to lower average total costs for the firm that is able to

expand its scale of operations. Where economies of scale are possible, an increase in

all resources of, say, 10 percent will cause a more-than-proportionate increase in out-

put of, say, 20 percent. The result will be a decline in ATC.

202 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

economies

of scale

Reductions in the

average total cost of

producing a product

as the firm expands

the size of plant (its

output) in the long

run; the economies

of mass production.

chapter eight • the organization and the costs of production 203

In many Canadian manufacturing industries, economies of scale have been of

great significance. Firms that have expanded their scale of operations to obtain

economies of mass production have survived and flourished. Those unable to

expand have become relatively high-cost producers, doomed to struggle to survive.

DISECONOMIES OF SCALE

In time the expansion of a firm may lead to diseconomies and, therefore, higher

average total costs.

The main factor causing diseconomies of scale is the difficulty of efficiently con-

trolling and coordinating a firm’s operations as it becomes a large-scale producer.

In a small plant a single key executive may make all the basic decisions for the

plant’s operation. Because of the firm’s small size, the executive is close to the pro-

duction line, understands the firm’s operations, and can digest information and

make efficient decisions.

This neat picture changes as a firm grows. Many management levels now come

between the executive suite and the assembly line; top management is far

removed from the actual production operations of the plant. One person cannot

assemble, digest, and understand all the information essential to decision making

on a large scale. Authority must be delegated to many vice-presidents, second

vice-presidents, and so forth. This expansion of the management hierarchy leads

to problems of communication and cooperation, bureaucratic red tape, and the

possibility that decisions will not be coordinated. Similarly, decision making may

be slowed down to the point that decisions fail to reflect changes in consumer

tastes or technology quickly enough. The result is impaired efficiency and rising

average total costs.

Also, in massive production facilities workers may feel alienated from their

employers and care little about working efficiently. Opportunities to shirk respon-

sibilities, by avoiding work in favour of on-the-job leisure, may be greater in large

plants than in small ones. Countering worker alienation and shirking may require

additional worker supervision, which increases costs.

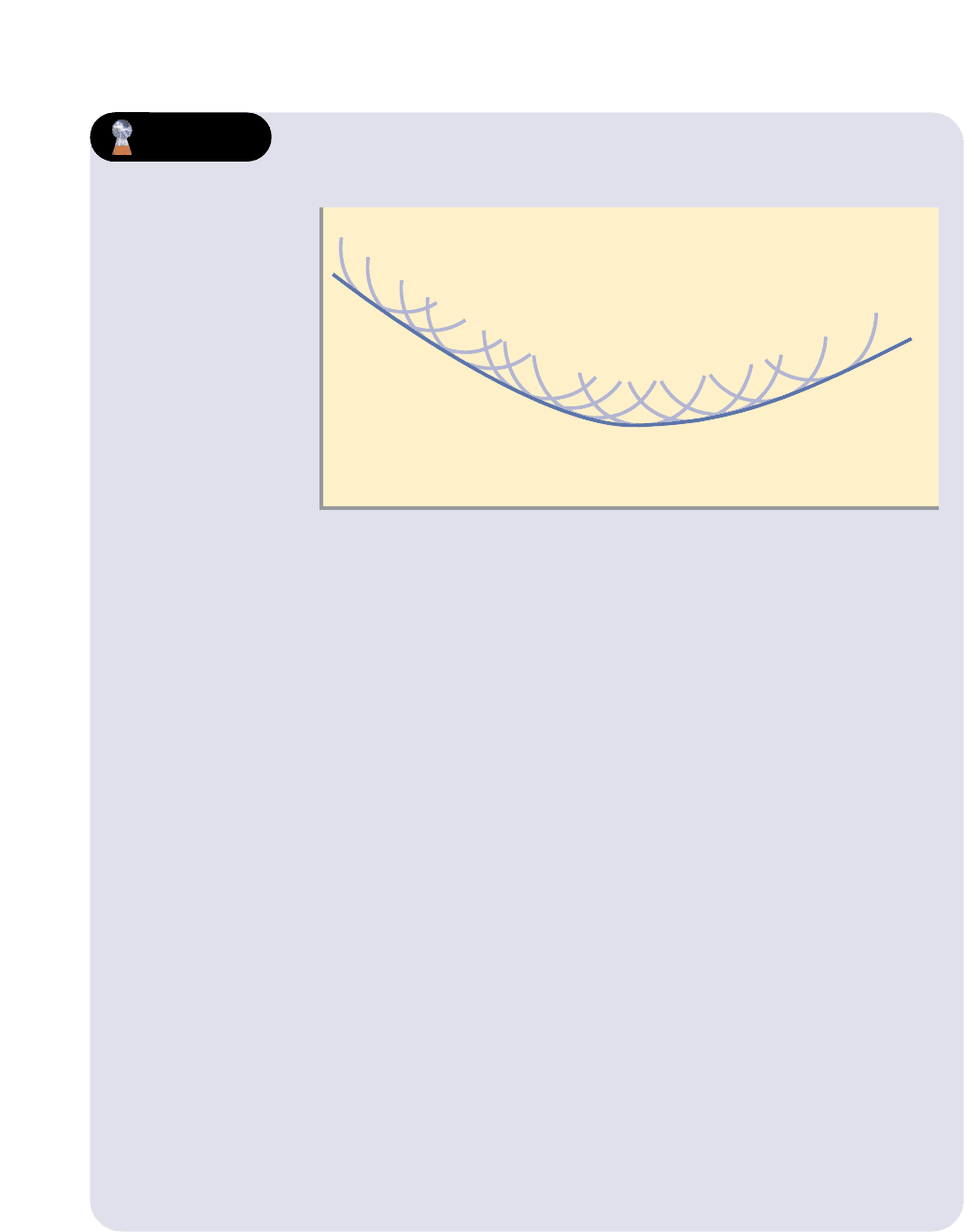

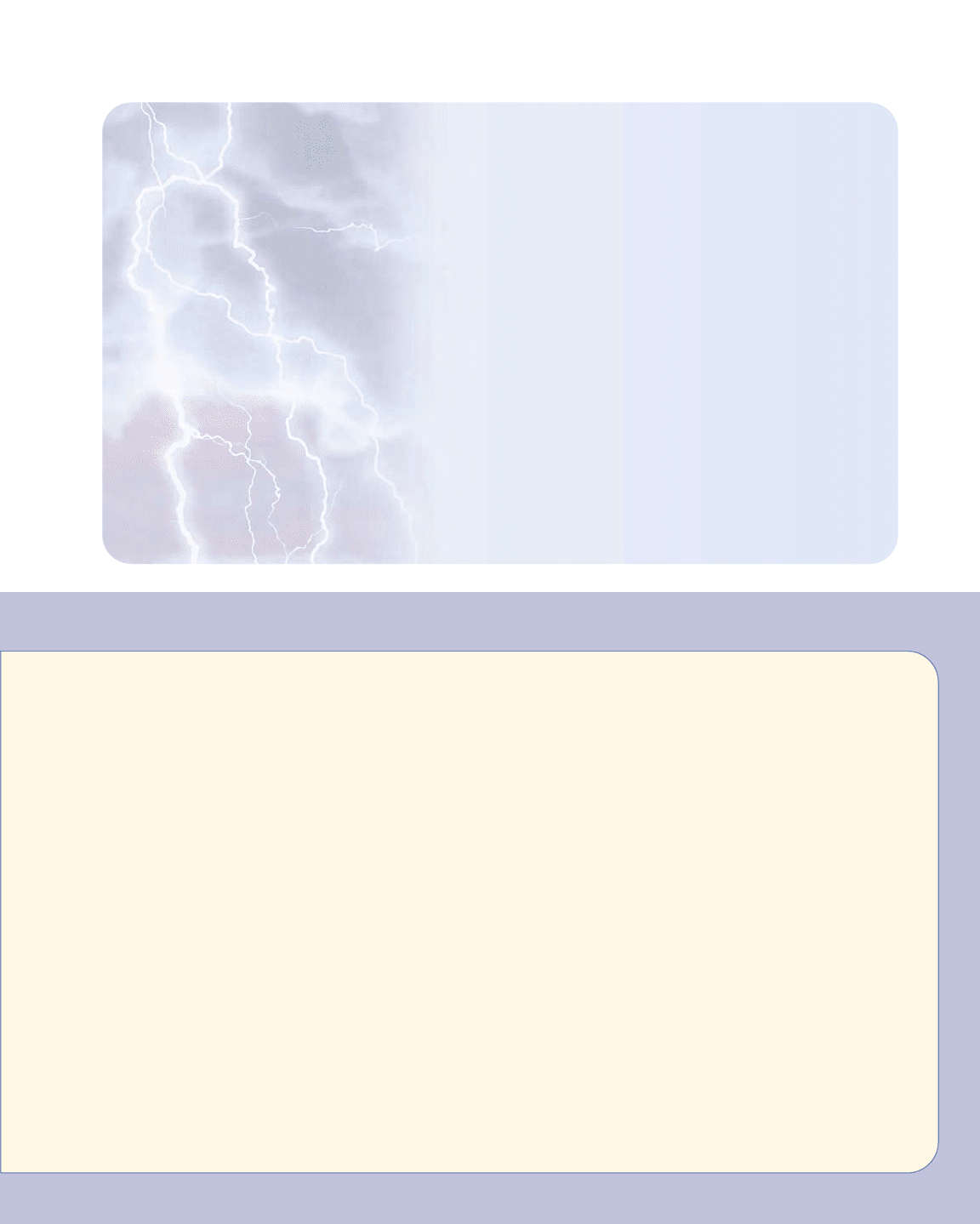

Where diseconomies of scale are operative, an increase in all inputs of, say, 10

percent will cause a less-than-proportionate increase in output of, say, 5 percent. As

a consequence, ATC will increase. The rising portion of the long-run cost curves in

Figure 8-9 illustrates diseconomies of scale.

CONSTANT RETURNS TO SCALE

In some industries a rather wide range of output may exist between the output at

which economies of scale end and the output at which diseconomies of scale begin.

That is, a range of constant returns to scale may exist over which long-run average

cost does not change. The q

1

q

2

output range of Figure 8-9(a) is an example. Here a

given percentage increase in all inputs of, say, 10 percent will cause a proportionate

10 percent increase in output. Thus, in this range ATC is constant.

Applications and Illustrations

The business world offers many examples of economies and diseconomies of scale.

Here are just a few.

SUCCESSFUL STARTUP FIRMS

The Canadian economy has greatly benefited over the past few decades by explo-

sive growth of new startup firms. Where economies of scale are significant, such

dis-

economies

of scale

Increases in the

average total cost of

producing a product

as the firm expands

the size of its plant

(its output) in the

long run.

constant

returns

to scale

The

range of output

between the output

at which economies

of scale end and

diseconomies of

scale begin.

<www.theshortrun.com/

classroom/glossary/

micro/costprofit.html>

Cost and profit

summarized,

including constant

returns to scale

204 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

Average total costs

Output

0

Q

Long-run

ATC

If the number of

possible plant sizes

is very large, the

long-run average-

total-cost curve

approximates a

smooth curve.

Economies of

scale, followed

by diseconomies

of scale, cause

the curve to be

U-shaped.

FIGURE 8-8 THE LONG-RUN AVERAGE-TOTAL-COST

CURVE: UNLIMITED NUMBER OF

PLANT SIZES

Key Graph

Quick Quiz

1. The unlabelled tinted curves in this figure illustrate the

a. long-run average-total-cost curves of various firms constituting the industry.

b. short-run average-total-cost curves of various firms constituting the industry.

c. short-run average-total-cost curves of various plant sizes available to a partic-

ular firm.

d. short-run marginal-cost curves of various plant sizes available to a particular

firm.

2. The unlabelled tinted curves in this figure derive their shapes from

a. decreasing, then increasing, short-run returns.

b. increasing, then decreasing, short-run returns.

c. economies, then diseconomies, of scale.

d. diseconomies, then economies, of scale.

3. The long-run ATC curve in this figure derives its shape from

a. decreasing, then increasing, short-run returns.

b. increasing, then decreasing, short-run returns.

c. economies, then diseconomies, of scale.

d. diseconomies, then economies, of scale.

4. The long-run ATC curve is often called the firm’s

a. planning curve.

b. capital-expansion path.

c. total-product curve.

d. production possibilities curve.

Answers

1. c; 2. b; 3. c; 4. a

firms can enjoy years or even decades of growth accompanied by lower average

total costs. That has been the case for such internationally recognized firms as Intel

(microchips), Starbucks (coffee), Ballard Power Systems (fuel cells), Microsoft (soft-

ware), Celestica (computer components), Dell (personal computers), Yahoo (Inter-

net search engine), Cisco Systems (Internet switching), Nortel Networks (fibre

optics), Federal Express (overnight delivery), and America Online (Internet access).

chapter eight • the organization and the costs of production 205

FIGURE 8-9 VARIOUS POSSIBLE LONG-RUN AVERAGE-TOTAL-

COST CURVES

Economies

of scale

Constant returns

to scale

Diseconomies

of scale

Long-run

ATC

Average total costs

Output

0

q

1

q

2

Average total costs

Output

0

(a)

(b)

(c)

Average total costs

Output

0

Long-run ATC

Long-run ATC

In panel (a),

economies of scale

are rather rapidly

obtained as plant

size rises, and disec-

onomies of scale are

not encountered until

a considerably large

scale of output has

been achieved. Thus,

long-run average

total cost is constant

over a wide range of

output. In panel (b),

economies of scale

are extensive, and

diseconomies of

scale occur only at

very large outputs.

Average total cost,

therefore, declines

over a broad range

of output. In panel (c),

economies of scale

are exhausted

quickly, followed

immediately by disec-

onomies of scale.

Minimum ATC thus

occurs at a relatively

low output.

206 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

A major source of these economies of scale is the ability to spread huge product

development and advertising costs over an increasing number of units of output.

These firms also benefit from the greater specialization of labour, management, and

capital equipment permitted by larger firm size. In some cases, the full exploitation

of economies of scale is still continuing. For example, Bell Canada’s cost of deliver-

ing Internet access to each additional user is very low. Thus, its average total cost

probably will continue to fall as it signs up more subscribers.

THE VERSON STAMPING MACHINE

In 1996 Verson (a U.S. firm located in Chicago) introduced a 15-metre-tall metal-

stamping machine that is the size of a house and weighs as much as 12 locomotives.

This $30 million machine, which cuts and sculpts raw sheets of steel into automo-

bile hoods and fenders, enables automakers to make new parts in just five minutes

compared with eight hours for older stamping presses. A single machine is designed

to make five million auto parts a year. So, to achieve the cost saving from this

machine, an auto manufacturer must have sufficient auto production to use all these

parts. By allowing the use of this cost-saving piece of equipment, large firm size

achieves economies of scale.

THE DAILY NEWSPAPER

The daily newspaper is undoubtedly one of the economy’s great bargains. Think of

all the resources that are combined to produce it: reporters, delivery people, pho-

tographers, editors, management, printing presses, pulp mills, pulp mill workers,

ink manufacturers, forest-product firms, loggers, logging truck drivers, and on and

on. Yet, for 50¢ you can buy a high-quality newspaper in major cities.

The fundamental reason that newspapers have such low prices are the low costs

resulting from economies of scale. If only 100 or 200 people bought the paper each

day, the average cost of each paper would be exceedingly high because the overhead

(fixed) costs of producing the paper would be spread over so few readers. But when

publishers sell thousands or hundreds of thousands of newspapers each day, they

spread their overhead cost very widely. They also can fully use expensive but

highly efficient printing presses. For both reasons, the average total cost of a paper

sinks to a few dimes. Moreover, the greater the number of readers, the more money

advertisers are willing to pay for ad space. That added revenue helps keep the price

of the newspaper low.

GENERAL MOTORS

Executives of General Motors, the world’s largest auto producer, are well aware

of the realities of diseconomies of scale. Experts on the auto industry say GM’s

large size may be a liability; it is substantially larger than Ford and Daimler-

Chrysler and is larger than Toyota and Honda combined. Compared with these

competitors, GM has a cost disadvantage that may help explain its substantial

decline in long-term market share. Despite billions of dollars of investment in

modern equipment, GM still has the lowest productivity and the highest cost per

car in the industry.

To try to reduce scale diseconomies, GM has taken several actions. It has estab-

lished joint ventures (combined projects) with smaller foreign rivals such as Toyota

to reduce its production costs. It has created Saturn, a separate, stand-alone auto

manufacturing company. It has given each of its five automotive divisions (Chevro-

let, Buick, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, and Cadillac) greater autonomy with respect to

styling, engineering, and marketing decisions to reduce the layers of managerial

approval required in decision making. Finally, GM has reorganized into a small-car

group and a midsize and luxury group to try to cut costs and bring new cars to the

market faster. Whether these actions will overcome GM’s diseconomies of scale

remains to be seen.

Minimum Efficient Scale and Industry Structure

Economies and diseconomies of scale are an important determinant of an industry’s

structure. Here we introduce the concept of minimum efficient scale (MES), which

is the lowest level of output at which a firm can minimize long-run average costs.

In Figure 8-9(a) that level occurs at q

1

units of output. Because of the extended range

of constant returns to scale, firms producing substantially greater outputs could also

realize the minimum attainable average costs. Specifically, firms within the q

1

to q

2

range would be equally efficient, so we would not be surprised to find an industry

with such cost conditions to be populated by firms of quite different sizes. The

apparel, food processing, furniture, wood products, snowboard, and small-

appliance industries are examples. With an extended range of constant returns to

scale, relatively large and relatively small firms can coexist in an industry and be

equally successful.

Compare this with Figure 8-9(b), where economies of scale prevail over a wide

range of output and diseconomies of scale appear only at very high levels of out-

put. This pattern of declining long-run average total cost may occur over an

extended range of output, as in the automobile, aluminum, steel, and other heavy

industries. The same pattern holds in several of the new industries related to infor-

mation technology, for example, computer microchips, operating system software,

and Internet service provision.

Given consumer demand, efficient production will be achieved with a few large-

scale producers. Small firms cannot realize the minimum efficient scale and will not

be able to compete. In the extreme, economies of scale might extend beyond the

market’s size, resulting in what is termed natural monopoly, a relatively rare mar-

ket situation in which average total cost is minimized when only one firm produces

the particular good or service.

Where economies of scale are few and diseconomies come into play quickly, the

minimum efficient size occurs at a low level of output, as shown in Figure 8-9(c). In

such industries a particular level of consumer demand will support a large number

of relatively small producers. Many retail trades and some types of farming fall into

this category. So do certain kinds of light manufacturing, such as the baking, cloth-

ing, and shoe industries. Fairly small firms are as efficient as, or more efficient than,

large-scale producers in such industries.

Our point here is that the shape of the long-run average-total-cost curve is deter-

mined by technology and the economies and diseconomies of scale that result. The

shape of the long-run ATC curve, in turn, can be significant in determining whether

an industry is populated by a relatively large number of small firms or is dominated

by a few large producers, or lies somewhere in between.

We must be cautious in our assessment, because industry structure does not

depend on cost conditions alone. Government policies, the geographic size of mar-

kets, managerial strategy and skill, and other factors must be considered in explain-

ing the structure of a particular industry. (Key Question 12)

chapter eight • the organization and the costs of production 207

minimum

efficient

scale (mes)

The lowest level of

output at which a

firm can minimize

long-run average

costs.

natural

monopoly

An

industry in which

economies of scale

are so great that a

single firm can

produce the product

at a lower average

total cost than if

more than one

firm produced the

product.

208 Part Two • Microeconomics of Product Markets

There is an old saying: Don’t cry

over spilt milk. The message is

that once you have spilled a glass

of milk, there is nothing you can

do to recover it, so you should

forget about it and move on from

there. This saying has great rele-

vance to what economists call

sunk costs. Such costs are like

sunken ships on the ocean floor:

once these costs are incurred,

they cannot be recovered.

Let’s gain an understanding of

this idea by applying it first to con-

sumers and then to businesses.

Suppose you buy an expensive

ticket to an upcoming football

game, but the morning of the

game you wake up with a bad case

of the flu. Feeling miserable, you

step outside to find that the wind

chill is about –20 degrees. You ab-

solutely do not want to go to the

game, buy you remind yourself

that you paid a steep price for the

ticket. You call several people to

try to sell the ticket, but you soon

discover that no one is interested

in it, even at a discounted price.

You conclude that everyone who

wants a ticket has one.

Should you go to the game?

Economic analysis says that you

should not take actions for which

marginal cost exceeds marginal

benefit. In this situation, the price

you paid for the ticket is irrele-

vant to the decision; both mar-

ginal or additional costs and

marginal or additional benefit

are forward-looking. If the mar-

ginal cost of going to the game is

greater than the marginal bene-

fit, the best decision is to go back

to bed. This decision should be

the same whether you paid $2,

$20, or $200 for the game ticket,

because the price that you pay

for something does not affect is

marginal benefit. Once the ticket

has been purchased and cannot

be resold, its cost is irrelevant to

the decision to attend the game.

Since you absolutely do not want

to go, clearly the marginal cost

exceeds the marginal benefit of

the game.

Here is a second consumer

example. Suppose a family is on

vacation and stops at a roadside

stand to buy some apples. The

kids get back into the car and

bite into their apples, immedi-

ately pronouncing them “totally

mushy” and unworthy of an-

other bite. Both parents agree

that the apples are “terrible,”

but the father continues to eat

his, because, as he says, “We

paid a premium price for them.”

One of the older children replies,

“Dad, that is irrelevant.” Al-

though not stated very diplomat-

ically, the child is exactly right.

In making a new decision, you

should ignore all costs that are

not affected by the decision. The

prior bad decision (in retrospect)

to buy the apples should not dic-

tate a second decision for which

marginal benefit is less than

marginal cost.

Now let’s apply the idea of

sunk costs to firms. Some of a

firm’s costs are not only fixed (re-

curring, but unrelated to the level

of output) but are sunk (unrecov-

erable). For example, a nonre-

fundable annual lease payment

for the use of a store cannot be

IRRELEVANCY OF SUNK COSTS

Sunk costs should be disregarded in decision making.

● Most firms have U-shaped long-run average-

total-cost curves, reflecting economies and then

diseconomies of scale.

● Economies of scale are the consequence of

greater specialization of labour and management,

more efficient capital equipment, and the spread-

ing of startup costs among more units of output.

● Diseconomies of scale are caused by the prob-

lems of coordination and communication that

arise in large firms.

● Minimum efficient scale is the lowest level of

output at which a firm’s long-run average total

cost is at a minimum.

chapter eight • the organization and the costs of production 209

chapter summary

1. The firm is the most efficient form of organ-

izing production and distribution. The main

goal of a firm is to maximize profit.

2. Sole proprietorships, partnerships, and cor-

porations are the major legal forms that busi-

ness enterprises may assume. Though

proprietorships dominate numerically, the

bulk of total output is produced by corpora-

tions. Corporations have grown to their posi-

tion of dominance in the business sector

primarily because they are characterized by

limited liability and can acquire money capi-

tal for expansion more easily than other

firms can.

3. Economic costs include all payments that

must be received by resource owners to

ensure a continued supply of needed re-

sources to a particular line of production.

Economic costs include explicit costs, which

flow to resources owned and supplied by

others, and implicit costs, which are pay-

ments for the use of self-owned and self-

employed resources. One implicit cost is a

normal profit to the entrepreneur. Economic

profit occurs when total revenue exceeds

total cost (= explicit costs + implicit costs,

including a normal profit).

4. In the short run a firm’s plant capacity is

fixed. The firm can use its plant more or less

intensively by adding or subtracting units of

various resources, but it does not have suffi-

cient time in the short run to alter plant size.

5. The law of diminishing returns describes

what happens to output as a fixed plant is

used more intensively. As successive units

of a variable resource such as labour are

added to a fixed plant, beyond some point

the marginal product associated with each

additional worker declines.

6. Because some resources are variable and

others are fixed, costs can be classified

as variable or fixed in the short run. Fixed

costs are independent of the level of output;

recouped once it has been paid.

A firm’s decision about whether

to move from the store to a more

profitable location does not de-

pend on the amount of time re-

maining on the lease. If moving

means greater profit, it makes

sense to move whether there are

300 days, 30 days, or 3 days left

on the lease.

Or, as another example, sup-

pose a firm spends $1 million on

R&D to bring out a new product,

only to discover that the product

sells very poorly. Should the firm

continue to produce the product

at a loss even when there is no

realistic hope for future success?

Obviously, it should not. In mak-

ing this decision, the firm real-

izes that the amount it has spent

in developing the product is irrel-

evant; it should stop production

of the product and cut its losses.

In fact, many firms have dropped

products after spending millions

of dollars on their development.

Examples are the quick decision

by Coca-Cola to drop its New

Coke and the eventual decision

by McDonald’s to drop its

McLean Burger.

Consider a final real-world ex-

ample. For decades, Boeing and

McDonnell Douglas were keen

rivals in the worldwide sale of

commercial airplanes. Each com-

pany spent billions of dollars on

R&D and marketing in an at-

tempt to gain competitive ad-

vantages over each other. Then,

in 1996 they suddenly merged.

Many observers wondered how

two fierce rivals who had spent

such huge amounts to compete

could suddenly forget the past

and agree to merge. But these

past efforts and expenditures

were irrelevant to the decision;

they were sunk costs. The for-

ward-looking decision led both

companies to conclude, each for

its own reasons, that the mar-

ginal benefit of a merger would

outweigh the marginal cost.

In short, if a cost has been in-

curred and cannot be partly or

fully recouped by some other

choice, a rational consumer or

firm should ignore it. Sunk costs

are irrelevant. Or, as the saying

goes, don’t cry over spilt milk.