McKinney M. History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

84

Bart Beaty

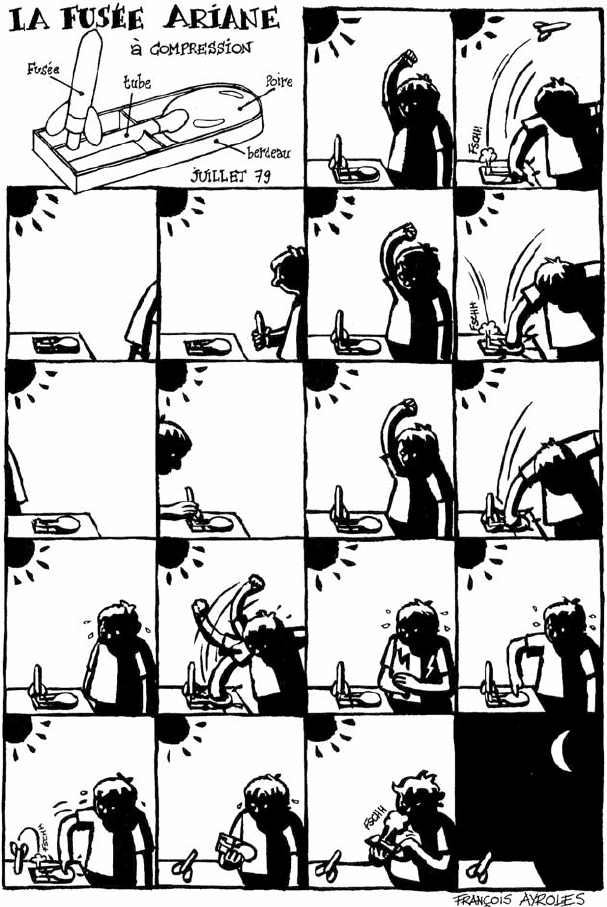

fig. 4. François Ayroles wears out the “gadget” from the July 1979 issue of Pif. From François Ayroles,

“La fusée Ariane,” Lapin,

no. 15, April 1997, p. 57. © François Ayroles / L’Association, paris / 1997.

85

“Patrimoine” in Franco-Belgian Comics

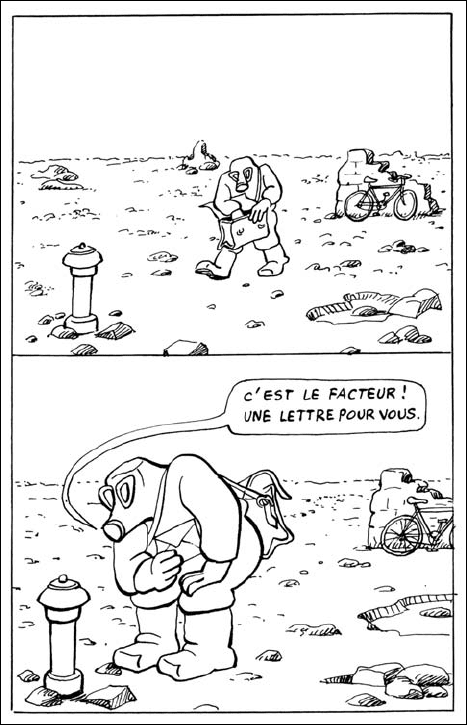

fig. 5. even in a postapocalyptic world, the mail must get through. From Gébé,

Lettre aux survivants,

paris: L’Association, 2002, p. 3. © Gébé / L’Association,

paris / 2002.

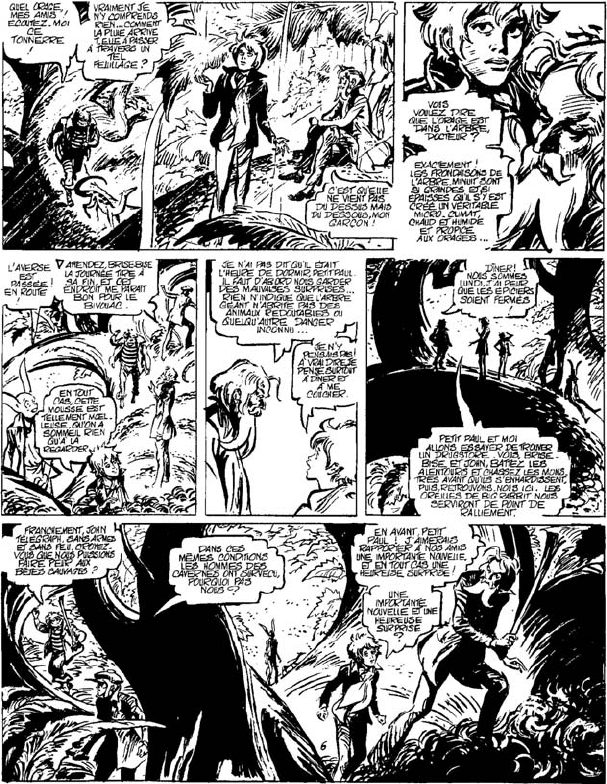

(Forest 2005), was originally published in Pilote in 1972 and 1973. Mystérieuse:

Matin, midi et soir (Forest 2004) collects work that originally appeared in

the Italian magazine Linus, and which was partially published in French by

Pif gadget, also beginning in 1971 (figure 6). In 2006, L’Association released a

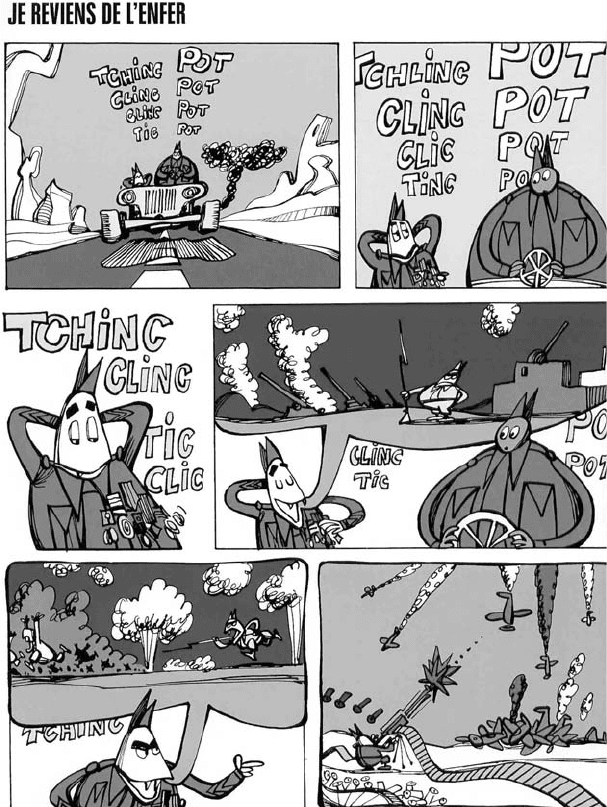

complete collection of Touïs and Frydman’s starkly antimilitarist humor strip

Sergent Laterreur, originally published in Pilote from 1971 to 1973 (figure 7).

86

Bart Beaty

fig. 6. Lost in an exotic land. From Jean-Claude Forest, Mystérieuse: Matin, midi et soir, paris:

L’Association, 2004, p. 6. © Jean-Claude Forest / L’Association, paris / 2004.

So, it is evident that recent republications from L’Association focus on the

historical era addressed by the artists in the Pif tribute found in Lapin no. 15

(e.g., Ayroles 1997). That period coincides with the changes in sensibility that

marked French cartooning following the student uprising and general strikes

of May 1968, but predates the arrival of the key modern adult-targeted comics

87

“Patrimoine” in Franco-Belgian Comics

fig. 7. A boastful sergeant recounts his wartime heroics. From Touïs and Frydman, Sergent Laterreur,

paris: L’Association, 2006, p. 6. © Touïs and Frydman / L’Association, paris / 2006.

magazines that began with the 1972 founding of L’écho des savanes. Through

their republication of work by Gébé, Forest, and Mattioli, L’Association es-

tablishes itself as a bridge to a proto-adult comics sensibility of the late-1960s.

This connection to proto-adult works serves to preempt the entire history of

88

Bart Beaty

science-fiction and fantasy-derived experimental comics (such as Moebius’s

Arzach [1976]) that dominates discussion of the 1970s in traditional histories

of the comic book in France.

Another republishing project by L’Association similarly reframes the

1980s. If Alex Barbier, with his difficult painting-based work, serves as the

aesthetic forefather of the Fréon group, the artistic tradition that inspires

L’Association is largely rooted in the work of Edmond Baudoin. This car-

toonist, whose 1980s publications were mostly issued by Futuropolis, is one of

the central early figures in the autobiographical comics movement. Working

in a loose visual style and with narratives that highlight the poetic aspects of

memory, Baudoin was a crucial figure for Futuropolis in the 1980s, a lead-

ing artist for the least traditional publisher of the period. When Futuropolis

ceased publishing comics in the early 1990s, Baudoin moved much of his

production to L’Association. In 1995 and 1996 the latter released three new

works by the artist: Eloge de la poussière (1995a), Made in U.S. (1995b), and

Terrains vagues (1996). Since that time, L’Association has been Baudoin’s pri-

mary artistic home, although he has also published with Seuil, Viviane Hamy,

and Dupuis, among others.

In 1997 L’Association republished one of Baudoin’s most celebrated Fu-

turopolis works, Le portrait. The story of a painter and his model, the book is

a rumination on the intersection of love and art. As the first work by Baudoin

to have been reprinted (first published by Futuropolis, in 1990), Le portrait

draws an explicit link between Futuropolis in the 1980s and L’Association in

the 1990s. An even stronger connection appeared in January 2006 with Les

sentiers cimentés (figure 8). This large book collected, in one volume, six of

Baudoin’s books that had been originally published by Futuropolis between

1981 and 1987, as well as one book from Zenda. In this way, L’Association—an

organization that is itself a partial offshoot of Futuropolis, having grown out

of that publisher’s abortive young-cartoonist anthology, LABO—is able to

lay claim to the aesthetic heritage of Robial and Cestac’s defunct publishing

house as a space for nonconventional comics. This appropriation, coupled

with the particular and peculiar connection that L’Association makes to

the proto-adult comics sensibilities of the late 1960s, defines comics history

through a series of aesthetic leaps. Essentially, the republication activities of

L’Association jump from 1973 to the late 1980s, from a proto-mature comics

sensibility, to its rejection of adventure-bound comic-book genres, and avoids

the era of “standardization” in the comics marketplace that Menu (2005b: 18)

criticizes in Plates-bandes.

89

“Patrimoine” in Franco-Belgian Comics

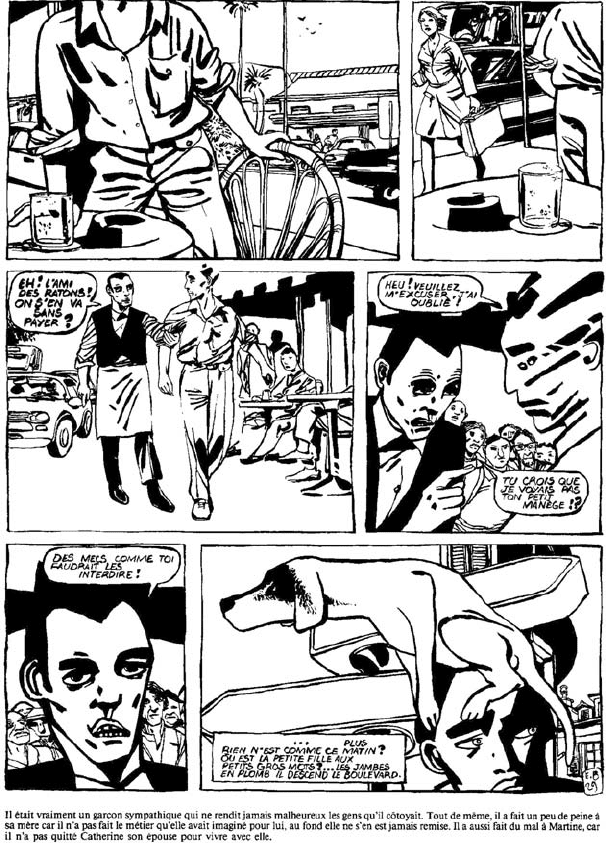

fig. 8. A confrontation with a waiter. From Baudoin’s Le premier voyage, reprinted in edmond

Baudoin, Les sentiers cimentés,

paris: L’Association, 2006, n.p. © edmond Baudoin / L’Association,

paris / 2006.

90

Bart Beaty

The history implied by L’Association’s republications effaces nearly the

entirety of the 1970s and much of the 1980s. Specifically, what is written out

of comics history by L’Association are those works that have a strong connec-

tion to science fiction and fantasy—precisely the work that would come to

dominate the field by the early 1990s. By bracketing this historical moment,

L’Association more clearly defines itself as a rejection of the mass market

traditions of the comics field, while at the same time resurrecting overlooked

or forgotten works by some of the most commercially successful and critically

acclaimed artists of the previous generation. In this way, L’Association self-

identifies with the previous generation through connoisseurship, by celebrat-

ing only the least known works of the consecrated cartoonists who preceded

them on the stage. This tendency is summed up by the unsigned introduction

of L’Association’s edition of Jean-Claude Forest’s Mystérieuse: Matin, midi et

soir, which concludes by noting that “L’Association is happy to republish this

masterpiece by one of the most inventive cartoonists, and a precursor of the

modern comic book” (Anonymous 2004: i). L’Association signals two inter-

ests here: a concern with the consecration of the past because it deserves to be

remembered on its own merits, as well as the utility that the past has for the

present in terms of justifying contemporary cultural practices.

ConClusion

The use of the past is, of course, central to Menu’s previously cited concerns

about the appropriation of the Futuropolis trademark by Gallimard and So-

leil. One significant reason for this is the fact that in the 1970s and 1980s

Futuropolis itself was very much caught up in the same sorts of reclamation

projects with regard to the history of comics, as are the publishers that I have

discussed here at greater length. Significantly, Futuropolis was the publisher

who republished several noteworthy, neglected classics of the Franco-Belgian

school, including Calvo’s 1944 Second World War allegory, La bête est morte!

and Saint-Ogan’s “Zig et Puce” series, and whose “Collection Copyright” of-

fered translations of many canonical American comic strips from the early

twentieth century, including Popeye, Krazy Kat, and Terry and the Pirates.

Thus, it is possible to conceptualize L’Association’s interest in “patrimoine” as

an extension of a project that was initiated by Futuropolis, and which is now

perceived to have been lost with the adoption of that trademark by Soleil.

Similarly, Jean-Louis Gauthey of Cornélius has suggested that the desire to

create his own publishing house was inspired by his interaction with Menu,

91

“Patrimoine” in Franco-Belgian Comics

but also by the hole left in French comics publishing by the disappearance of

publishers like Futuropolis and Artefact (in Bellefroid 2005: 34). These small-

press publishers, intent on replicating the Futuropolis model at the current

historical moment, make a forceful connection between the publishing ep-

ochs of the 1970s and the 1990s–2000s, to the notable exclusion of the 1980s,

a period which both disdain.

Significantly, of course, these publishers have sought to create an equiv-

alence between the radical politics of the past and the present day. While

Cornélius’s repackaging of Gus Bofa’s anguished and existential work from

the interwar period only vaguely recalls the politics of the Popular Front, a

more direct connection is made by Fréon and L’Association to more contem-

porary political upheavals. If, following the logic of Moliterni, Mellot, and

Denni, the events of May 1968 profoundly transformed the Franco-Belgian

comic-book publishing industry by creating an opportunity for artists to be

more self-expressive and politically engaged, little of that political sense has

survived in a market intent primarily on creating a perpetual back catalog

filled with “timeless” adventure classics. By resurrecting politically engaged

and aesthetically charged works from this period, therefore, L’Association

and Fréon create a bridge between the politics of the past and the contempo-

rary social concerns of the present.

Writing about the state of the field of comic-book production in France

in 1975, Luc Boltanski (44), a colleague of Bourdieu, argued that cultural

capital was being accrued in this domain for the first time. What had begun

to elevate comics from their perception as the mindlessly juvenile products

of mass culture were “the republication of older series that had disappeared

from the market” and the “establishment of specialized bookstores,” notably

the Futuropolis store, run by Robial and Cestac. I would argue that more

than thirty years later the historical excavation project begun by Futuropo-

lis and continued by the contemporary small press is a central facet in the

struggle for cultural capital and the creation of aesthetic legitimacy within

the field of comics. Even in 1975, Boltanski could diagnose an emerging

polarization of the comics field, a development that the small presses of

the 1990s pushed even further. Conceptions of connoisseurship have been

central to the establishment of distinction, and the recognition of the ne-

glected elements of a comic book heritage has become an important ele-

ment of discourses about comics. The establishment of a “bande dessinée

d’auteur,” to borrow Groensteen’s term, has been dependent, at least in part,

on the possibility of identifying overlooked artists from the past who serve

as important forebears in revisionist histories. The intellectualization of this

92

Bart Beaty

tendency has been considerably bolstered by the presence of a “Patrimoine”

section in each issue of the annual comics journal, 9e art, long edited by

Groensteen. Further, the commercialization of this tendency, through pro-

cesses of republication, has recently been recognized at the Festival Interna-

tional de la Bande Dessinée in Angoulême with the creation, in 2004, of a

Prix du Patrimoine. Significantly, nominees for this prize have included two

of L’Association’s Jean-Claude Forest books, their reprint of M le magicien,

and Barbier’s Lycaons from Fréon. It is therefore possible to affirm once

again that the process of recuperating lost or abandoned works is oriented,

at least in part, toward the accumulation of prestige.

The prestige generated by these publishing efforts is not an end in it-

self, but a piece in the larger struggle to legitimate the contemporary small-

press publishers as the most important in the field, at least critically if not

financially. Of course, the idea of consecrating forgotten cultural artifacts,

producers, and forms in order to rewrite history from a new perspective is

nothing new. Indeed, it plays out in all fields of cultural production where

the past is taken up in a new context and provided with new meanings, often

for strictly mercantile ends. For example, Casterman, one of the largest and

most traditional of the Franco-Belgian publishing houses, has recently be-

gun to repackage out-of-print works from their back catalog, by artists such

as Baru, Ted Benoît, Jacques Ferrandez, and even Jean-Claude Forest, for a

new generation of readers, in a line called “Classiques.” Nonetheless, publish-

ers such as Cornélius, Fréon, and L’Association employ a distinct strategy of

canon formation, whose primary purpose is explicitly reconceptualizing the

criteria of value within the field. On the one hand, this may not seem to be

tremendously different from the reissuing of so-called classic works that is a

standard part of catalog maintenance as practiced at the largest publishing

houses. Yet what sets this practice apart is the curious relationship that these

small-press publishers have with the canon, wherein they express an opposi-

tion to established notions of canonicity but fail to truly undermine notions

of exemplary works of art. In the recirculation of forgotten works, the pro-

duction of the canon remains a primary concern, as it does in all forms of

art history. Yet at the same time, the process of relegitimation, which carries

with it a constant threat or promise of delegitimation, draws our attention

to the specific power relations that structure notions of cultural value within

the comics field. For the cartoonists involved in the process of redefining

the nature of the comic book over the past fifteen years or so, this shift away

from the best-selling series revolving around a beloved character has been of

primary importance, and forms the logical basis upon which notions of con-

93

“Patrimoine” in Franco-Belgian Comics

secration and legitimation might be transformed. Central to this notion is the

importance of recreating history not as the story of the great artists defined

by fame and commercial success, but as a story of artists and works that were

so great that no one but the true connoisseur knew how great they were. This

shift in emphasis serves the needs of the contemporary small press, defined

by small print-runs, at the expense of the established publishing houses and

their large-scale production methods. The key to rewriting this history is the

tendency to champion the economic failures of the large presses as morally

and aesthetically superior to their successes, thereby shifting the understand-

ing of historical trajectories and challenging the economic logic of the field.

Note

1. All translations from the French are mine.