McKinney M. History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

114

Ann Miller

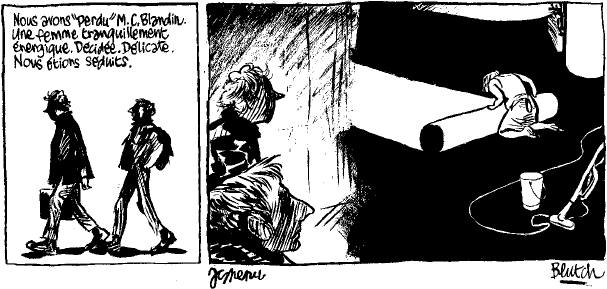

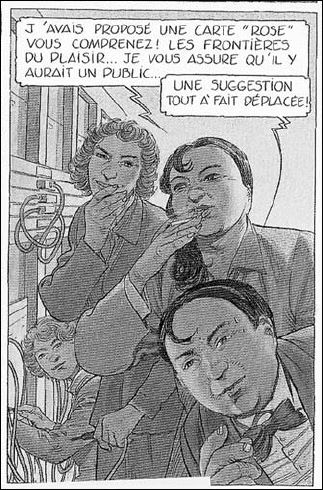

Fig. 8. the work of turning political fiction into political reality. from Blutch and menu (1996) “la

Présidente,” n.p.; © Blutch / JCmenu / l’association.

panel, while a recitative delivers their positive verdict on Blandin. The final

panel, apparently illogically, then shows them gazing from left to right toward

a woman on her knees rolling up a carpet, presumably red, with cleaning

implements in the foreground. However, the dark background against which

she is shown indicates that she does not occupy the same space as the artists,

and that the image of her is a subjective one on their part. The invasion of the

nonfictional space of the reportage by this make-believe element forces the

reader to assess its significance.

It may refer back to an exchange that takes place during the long interview

with Blandin. Here Menu had explained to her that they had at first set out

to write a fiction, “mais on ne le sentait vraiment pas” [we really weren’t get-

ting into it]. She had responded by saying that attempts to create a new kind

of politics also seem like “de la politique-fiction” [political fiction], a remark

interestingly echoed by Balibar a few years later. He asserts that the reinvention

of politics through an emphasis on the crossing rather than the reinforcing of

frontiers necessarily means venturing out into “les lieux de la fiction” [places of

fiction]: profound change has to be imagined before it can become real (Balibar

2002: 15). Blandin’s work, we may therefore understand, is to turn fiction into

reality. On this occasion, that has involved not only the public fronting of the

spectacle of international cooperation at the regional level but also, the artists

seem to imply, the kind of behind-the-scenes drudgery often performed by

women and often unacknowledged. This silent coda to the reportage would, in

this reading, be interpreted as a reflection upon the reality of politics as labori-

ous mise-en-scène, the precondition for making the impossible happen.

115

Bande dessinée as Reportage

ConCLusion

This chapter has investigated a recent tendency in bande dessinée, reportage,

focusing on a groundbreaking example of the genre. In so doing it has aimed

to demonstrate that, as a spatial medium, bande dessinée is well suited to the

rendering of a political project that depends on a particular conception of

regional citizenship, one that seeks to make connections across borders and to

reclaim city space as a public sphere. It is, furthermore, just as able to exploit

its resources to convey the slow grinding of democracy in action, and to sug-

gest the density of remembered time, as it is to speed up the action in political

fiction. The chapter has also argued that the reportage is made more effective

by the capacity of bande dessinée for plurivocality as well as for the plurality of

ways in which narratorial intervention can be made apparent. Ultimately, it is

the essence of a medium that does not solely depend on mechanical reproduc-

tion but is mediated by the artists’ hands and eyes that accounts for the impact

of this highly nuanced and personal portrayal of the political process.

Notes

1. For a definition of this term, please see above, p. xiii.

2. For a definition of this term, please see above, p. xiii.

3. Since the strip is unpaginated, no page references will be given.

4. The palatial residence and offices of the French president.

5. Spirou (1938–present) and Tintin (1946–93) magazines are classic children’s bande dessi-

née magazines, Belgian at their beginnings, but which were quickly distributed in France or

launched French editions.

6. Dupont and Dupond, the two look-alike Thomson detective characters from the classic

Tintin series by Belgian artist Hergé [pseud. Georges Remi; 1907–83]. In the French version, the

only things that (barely) distinguish them are the last letter of their surnames, and the slight

difference in the shape of their mustaches. The two are usually ridiculous and often serve to

provide comic relief.

7. A well-known line said by one of the Dupond/Dupont after a statement by the other

one: the humor of the line derives from the fact that the added commentary only ever restates

in other words what the first detective had already said, thereby adding nothing to the conver-

sation aside from a reformulation of something previously stated and obvious.

8. Claude Auclair (1943–90) was a French cartoonist whose best-known works focus on col-

onized cultural minorities (Caribbeans and Bretons). Patrick Cothias (1948–) is a scriptwriter.

9. Including Les Tuniques bleues [The Blue Tunics] (Cauvin and Salvé, from 1968), the

series which gave rise to Blutch’s sobriquet.

10. Blandin, a biology teacher by training and the first woman to be president of a regional

council in metropolitan France, is now a national senator from the Nord-Pas-de-Calais.

116

Ann Miller

11. Mitterrand (1916–96) was the Socialist Party president of France, 1981–95. He shared

power successively with two different right-wing prime ministers—Jacques Chirac and

Balladur—during separate periods of political cohabitation (1986–88; 1993–95), after the right

won the majority of seats in national legislative elections.

12. Paris Match is an illustrated French weekly that is a cross between Life magazine and a

tabloid (its famous slogan translates as “the weight of words, the shock of photos”). The Gare

du Nord is the Paris train station from which trains run to the northern part of France, includ-

ing the large metropolitan area of Lille and adjoining municipalities (Tourcoing, Roubaix,

etc.), to which the cartoonists travel in this bande dessinée. The hidden child that Paris Match

revealed to the public (no doubt with the blessing of the fatally ill Mitterrand) in 1994 is

Mazarine Pingeot (1974–), the daughter of Mitterrand and a mistress, Anne Pingeot, a curator

at the Musée d’Orsay, in Paris.

13. The northernmost of France’s modern-day regions, of which there are twenty-six total.

Lille is its capital city.

14. Just one year previously, Germinal had been filmed in the region, with something of a

nadir in postmodern irony being reached through the redeployment of unemployed ex-miners

as film extras portraying novelist Emile Zola’s strikers. The media attention arising out of the

film led to the opening of a mining museum, partly financed by the region, of which the recon-

struction of le Voreux, the mine of Zola’s novel, is still the main attraction. Blandin makes no

mention of this, clearly more concerned to deal with the real consequences of the past than to

recycle a mythologized past as heritage.

15. For a definition of this term, please see above, p. xiv.

16. Yourcenar [pseud. Crayencour, Marguerite de] (1903–87) was born in Belgium and

eventually settled in the United States. She was the first woman elected to the French Academy

(1980), a prestigious, old French state institution composed of forty authors.

17. An important administrative official at the level of the département, of which there

are one hundred in France today, and of the région (the préfet of the département where the

regional government is located also serves as a préfet for the région). The state-appointed préfet

represents the top-down authority of the national government, whereas the elected assembly

of the région or the département theoretically represents a more democratic, bottom-up form

of governance. The regional préfet has oversight of various aspects of the regional government,

including the budget voted by its assembly. Hence the potential for rivalry between Blandin

and the préfet.

Games Without Frontiers

The RepResenTaTion of poliTics

and The poliTics of RepResenTaTion

i

n schuiTen and peeTeRs’s

L

a frontière invisibLe

”ainsi fut construit jadis et se construit sans cesse le monument cartographique à jamais

présent—hors-temps , hors espace—de la représentation, le monument mémorial du roi et de

son géomètr

e.” [and thus was once built and is unceasingly built the forever present,

cartographic monument—outside of time, outside of space—of representation, the memorial

monument of the king and his surveyor]

—Louis Marin, Le Portrait du roi (1981: 220)

”when we make a map it is not only a metonymic substitution but also an ethical statement about

the world . . . [it] is a political issue.”

—J

. B. HarLey, “cartography, ethics, and social Theory” (1990: 6)

In a chapter of his essay Le portrait du roi [Portrait of the King], entitled

“Le roi et son géomètre” [The King and His Surveyor], Louis Marin reflects

on the hegemonic nature of mapping by analyzing Jacques Gomboust’s

1652 map of Paris, not only as an epistemological object characteristic of

scientific endeavor during the reign of Louis XIV, but also as a political

ch

apTeR six

—fabRice leRoy

117

118

Fabrice Leroy

project designed to assert and glorify Louis’s absolute monarchy (Marin 1981:

209–20). Although more recent studies on cartography have furthered the

analysis of the inherent linkage between politics and the production of spatial

knowledge and identity (Crampton 2002: 23), Marin’s essay remains a seminal

model in the field of political semiotics and discourse analysis, and clearly

shows how power relations are inscribed within representational systems, and

vice versa. Interestingly, Marin’s chapter also describes quite adequately the

codependency of a political leader and his official cartographer, which is at

play in La frontière invisible [The Invisible Frontier], the latest, two-volume

installment of Benoît Peeters’s and François Schuiten’s ambitious series of

graphic novels, “Les cités obscures” [Cities of the Fantastic]. This subject mat-

ter echoes a consistent network of meta-representational strategies and politi-

cal themes within Schuiten and Peeters’s body of work, which I will examine

in this essay.

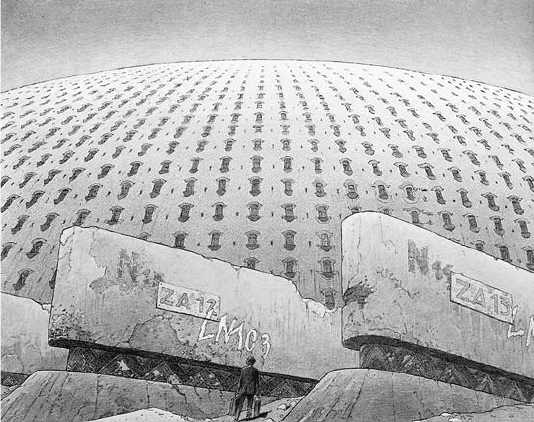

La frontière invisible tells the story of a young cartographer, Roland De

Cremer, who enters the professional world when he is appointed to the Car-

tography Center, a strange, dome- shaped structure in the middle of a desert,

in his home country of Sodrovno-Voldachia (figure 1). Although De Cremer’s

new surroundings constitute the archetype of the fantastique [fantastic] locus

Fig. 1. de cremer in front of the cartography center ( La frontière invisible, vol. 1, p. 10)

© schuiten-peeters / casterman.

119

Schuiten and Peeters’s La frontière invisible

(isolated, alienating, labyrinthine) and entail intertextual references to Dino

Buzzatti or Julien Gracq narratives of a young man assigned to the remote

outpost of a faceless power, the story is more Bildungsroman than fantastic

melancholia, as it focuses primarily on the professional and sentimental edu-

cation of the inexperienced cartographer. From the beginning, De Cremer is

confronted with conflicting methodologies and agendas. Yet uncritical of his

own cartographic training, he tends at first to simply objectify maps, does

not question their bias or authority, and remains generally in an undialecti-

cal relationship with the documents he is required to archive, analyze, and

produce. However, his understanding of mapping devices is quickly prob-

lematized, when he receives contradicting advice from two colleagues. I use

the word “problematized” here in the Foucauldian sense, meaning that “an

unproblematic field of experience, or a set of practices which were accepted

without question, which were familiar and ‘silent,’ out of discussion, becomes

a problem, raises discussion and debate, incites new reactions, and induces

a crisis in the previously silent behavior, habits, practices, and institutions”

(Foucault 2001: 74).

On one hand, De Cremer must adjust to a recent government mandate,

which requires new scientific methods of inquiry: the collection of “objec-

tive” data by a computer-assisted process, under the supervision of the mys-

terious and menacing Ismail Djunov, a néotechnologue [neo-technologist]

brought in to modernize the center’s methods of mapping. Djunov’s strange

and tentacular machines—full of tubes, wires, buttons, and displays of all

kinds (1: 31)

1

—are themselves consistent with a recurrent theme in “Les cités

obscures”: the early modern machine, retro-futuristic in its appearance, part

utopian technology, part monstrous device, which characterizes the alter-

nate, otherworldly modernity of Schuiten and Peeters’s parallel universe. La

frontière invisible contains other machines of this kind, for instance, some

decidedly Jules-Vernian modes of transportation which include a network

of suspended bicycles (1: 26–29), which provide city travelers an overhang-

ing perspective akin to that of cartography, and giant single-wheel vehicles

(2: 7–8, 39–43) that seem fantastic, yet technologically credible, like the world

of the “Cités obscures” itself. Although both modes of transportation appear

equally whimsical, they belong to different technological strata. The techno-

logical leap between the foot-powered bicycle and the new motorized vehicles

is akin to that between the hand-drawn map and the electronically traced

one, in that a new technology is making an old one obsolete.

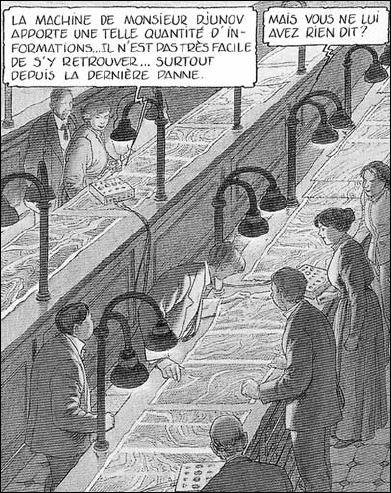

Djunov’s machines are, in essence, mere mimetic operators: they are de-

signed to produce a metonymic calque [traced image] of reality, to automatically

120

Fabrice Leroy

translate a geographic referent into its mirror cartographic image, without

any subjective interpretation (figure 2). Yet Djunov’s project, like Gom-

boust’s, masks a highly politicized one. His “perfect” representation, like

that of Louis XIV’s official engineer, disguises a political agenda under the

appearance of rigorous scientific methods and measurements (Marin 1981:

211). Operating under the authority of science, Djunov, like Gomboust, con-

structs a referential representation that presents itself as the exact equiva-

lent of its real-life counterpart, as validated and self-validating universal

truth. Both men of science work indeed for the raison d’état [reason of

state]: Gomboust for the Sun King and Djunov for Sodrovno-Voldachia’s

grim new totalitarian leader, Radisic, who demands an image of his nation-

state that mirrors and justifies—Roland Barthes [1972: 109–59] would say

“naturalizes,” or “mythologizes,” as it aims to present ideologically con-

structed culture as nature—his imperialistic agenda, particularly the con-

quest of the neighboring principality of Muhka. Djunov’s pseudoscientific

conclusions are therefore preestablished and guide his research from the

onset: he is to represent the state’s natural borders as they should be, or as

Fig. 2. djunov’s machines produce confusing data (La frontière

invisible,

vol. 1, p. 45) © schuiten-peeters / casterman.

121

Schuiten and Peeters’s La frontière invisible

the dominant political consensus requires them to be carved up. As Radisic

himself puts it: “Ce qui compte, ce ne sont pas les cartes mais ce qu’on veut

leur faire dire. J’attends de vous [les cartographes] que vous me fournissiez

des arguments irréfutables dans mon combat pour la grande Sodrovnie”

(1: 60). [What matters is not the maps, but what one wants them to signify. I

am expecting that you (the cartographers) provide me with irrefutable argu-

ments in my fight for the great Sodrovnia.] Of course, the concept of natu-

ral borders and its accompanying propaganda remind the reader of various

twentieth-century territory disputes and their ensuing conflicts—from Third

Reich expansionist justifications (Monmonier 199 1: 99 –107) to tensions in

Palestine, Yugoslavia, or Kashmir—yet of none in particular in the trans-

posed fictional setting, although the name Radisic undeniably evokes Serbian

connotations, and a dividing wall within a city conjures up images of Berlin

(Peeters 2005: 162).

As an agent of the state, mandated to visualize its body as the precon-

ceived image of its ruling power (“L’Etat, c’est moi;” “la Sodrovno-Voldachie,

c’est Radisic”), Djunov draws attention to both the power and the power-

lessness of political representation. As Marin reminds us, representation is a

transitive act: it supposes an equivalence or substitution between two objects,

one real but absent, the other symbolic but present (9–10). Representation

is also an assertive act: it authorizes and legitimates its own symbolic trans-

formation, in this case, the transformation of actual physical force into the

symbolic expression of the ability to produce force if needed (11). Force is

real, but power is symbolic: the latter is therefore a fragile construct, because

it hides a reluctance or inability to use force once again, to repeatedly use

force, and relies on the acceptance or consensus of the public. If representa-

tion “is nothing else but the fantastic image in which power contemplates

itself as absolute” (12), it is also de facto “the mourning of the absoluteness

of force,” the paradoxical expression of the impossibility of absolutism. It is

therefore understandable that political leaders would find attempts against

their image as dangerous as those against their person. This is the conundrum

in which young De Cremer will find himself in this story: an accidental and

unbeknownst thorn in the side of the political representational machine and

its controlling cartographic vision.

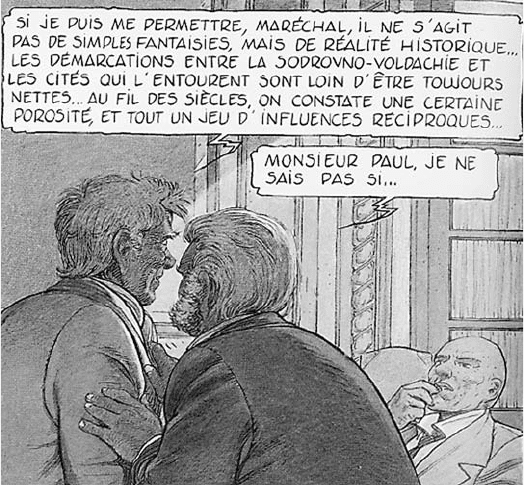

At the opposite end of Djunov, De Cremer encounters another concep-

tion of cartography under the training of his supervisor and mentor, Monsieur

Paul Cicéri, an aging cartographer, whose methods lag behind the center’s

new epistemological direction. A man of interpretation (always a dangerous

tendency under a totalitarian regime), Cicéri is more concerned with how

122

Fabrice Leroy

things are, with man’s Being-in-the-World, with capturing and understand-

ing the many changing aspects of experiential reality within the framework

of geographical knowledge. If, to quote Heidegger’s distinction, Djunov is a

man of ontic predisposition, whose scientific approach consciously distorts,

misrepresents, or simply ignores life’s real experiences or pleasures, Cicéri is,

by contrast, preoccupied with ontological inquiry. For him, borders construct

arbitrary lines within a continuum of human experiences (Frontière 1: 20, 60).

A reader of history, he is concerned that maps, because of their synchronic

bias, are fundamentally antihistorical and anti-biographical, and therefore

present a false, static representation incapable of capturing an ever-changing

territory and the reciprocal cultural exchanges that take place among its

people (1: 60). Instead, Cicéri creates counter-maps of human beliefs, values,

and cultures in order to highlight the porosity of borders and the absurdity

of nationalistic rhetoric, a subversive activity that causes his downfall when

Radisic takes control of the center (figure 3). The man who was once critical

of Evguénia Radisic’s overblown national romanticism (1: 25) is fired by her

ruthless descendant and exiled in the basement of the center, a relic living

Fig. 3. cicéri’s understanding of maps conflicts with Radisic’s political agenda (La

frontière invisible,

vol. 1, p. 60) © schuiten-peeters / casterman.

123

Schuiten and Peeters’s La frontière invisible

among strange Darwinian fossils of extinct species—an ironic subterranean

relegation of historical perspective by a political power intent on burying any

counter-knowledge provided by diachronic critical thinking under the sur-

face of pseudo-hegemonic legitimacy. Amusingly, Cicéri will eventually be re-

placed by a crew of ex-prostitutes (2: 14), clearly unqualified as cartographers,

but nevertheless inclined to continue Cicéri’s subversive counter-discourse,

as they offer to draft a map of pleasure, unknowingly echoing Foucault’s

(1985: 5 8 –65) advocacy of the “pleasure of mapping,” a strategy to critically

challenge the dominant representational paradigm by viewing mapping as a

practice of freedom and pleasure, reacting against the state’s normalization

of people and their individual desires (figure 4).

Caught between his sympathy for Cicéri and his devotion to his duties,

as defined by Djunov’s new methods, De Cremer grows increasingly confused

and weary of his function. On one hand, Radisic promotes him to the envi-

able position of director of the Cartography Center, and the young man ap-

pears to have a promising future in the political realm as one of the leader’s

Fig. 4. prostitutes suggest a “map of pleasures” (La

frontière invisible,

vol. 2, p. 14) © schuiten-peeters /

casterman.