Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BLACKBOARD JUNGLEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

269

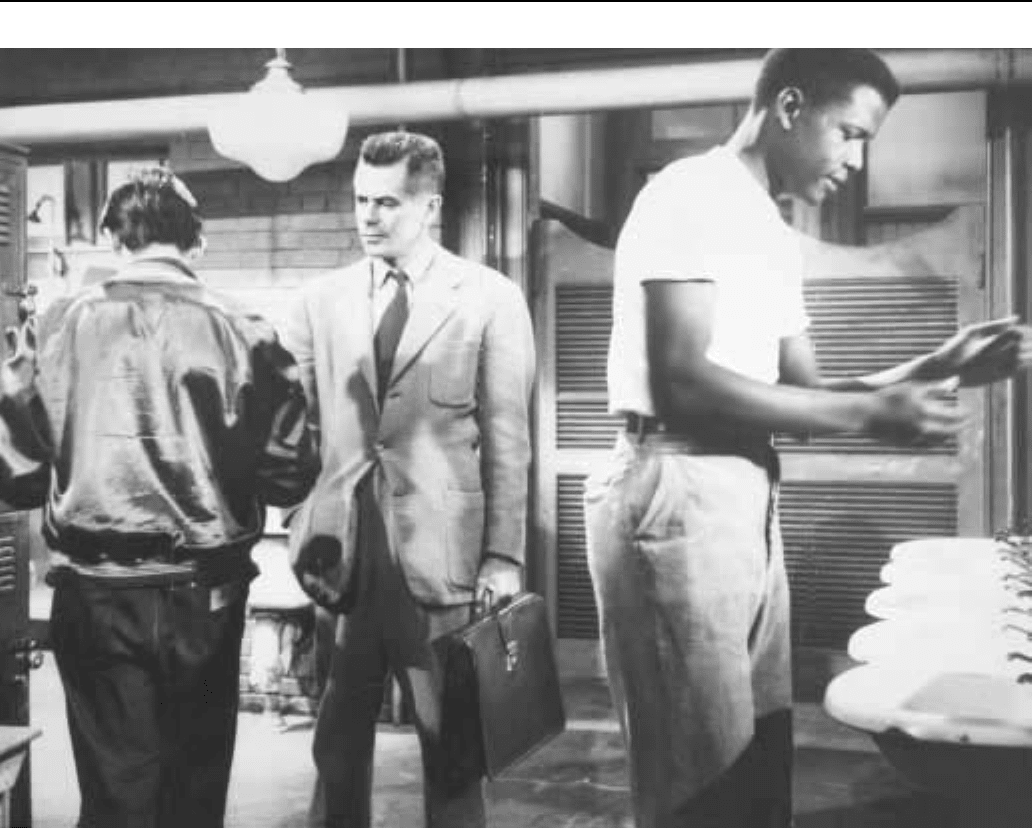

Sidney Poitier (far right) and Glenn Ford in a scene from the film The Blackboard Jungle.

sequence, with ‘‘Rock Around the Clock’’ blaring from the sound

track as Glenn Ford makes his way through the school yard crowded

with boys dancing, sullenly shaking their heads in time to the music,

the tone was set. This massed gathering appeared at once threatening

and appealing, something with which teenagers could identify, and

the image of exuberant, youthful rebellion stayed with teen audiences.

The film’s moral, somewhat hectoring message, was more

calculated to appeal to parents, while Brooks himself veiled his own

sympathies in subtlety. ‘‘These kids were five and six years old in the

last war,’’ a cynical police detective tells Dadier. ‘‘Father in the army,

mother in the defense plant; no home life, no church life. Gang leaders

have taken the place of parents.’’ Indeed, the specter of war pervades

the film. In one scene, Dadier derides a fellow teacher for using his

war injuries to gain the sympathy of his class; in another, he counsels

the recalcitrant West, who responds that if his crime lands him in jail

for a year, it will at least keep him out of the army, and hence, from

becoming another nameless casualty on foreign soil.

One cannot say, however, that Richard Brooks offers a profound

critique, or even a very good film. (‘‘[It] it will be remembered for its

timely production and release,’’ wrote film critic G.N. Fenin in

summation.) It was not so much the message or the quality of

filmmaking that was of import, but the indelible image it left behind

of the greasy-haired delinquent snapping his fingers to the beat of Bill

Haley and the Comets. This is the nature, the calculus if you will, of

exploitation films; that under the rubric of inoculation, they spread the

very contagion they are ostensibly striving to contain.

—Michael Baers

F

URTHER READING:

Cowie, Peter, editor. Aspects of American Cinema. Paris, Edition le

Terrain Vague, 1964.

Hunter, Evan. The Blackboard Jungle. London, Constable, 1955.

Lewis, Jon. The Road to Romance and Ruin: Teen Films and Youth

Culture. New York, Routledge, 1992.

Marill, Alvin H. The Films of Sidney Poitier. Secaucus, Citadel

Press, 1978.

Miller, Jim, editor. The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock &

Roll. New York, Rolling Stone Press, 1980.

BLACKFACE MINSTRELSY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

270

Pettigrew, Terence. Raising Hell: The Rebel in the Movies. New

York, St. Martin’s Press, 1986.

Raffman, Peter, and Jim Purdy. The Hollywood Social Problem Film:

Madness, Despair, and Politics from the Depression to the Fifties.

Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1981.

Blackface Minstrelsy

Taboo since the early 1950s, blackface minstrelsy developed in

the late 1820s just as the young United States was attempting to assert

a national identity distinct from Britain’s. Many scholars have identi-

fied it as the first uniquely American form of popular entertainment.

Blackface minstrelsy was a performance style that usually consisted

of several white male performers parodying the songs, dances, and

speech patterns of Southern blacks. Performers blackened their faces

with burnt cork and dressed in rags as they played the banjo, the bone

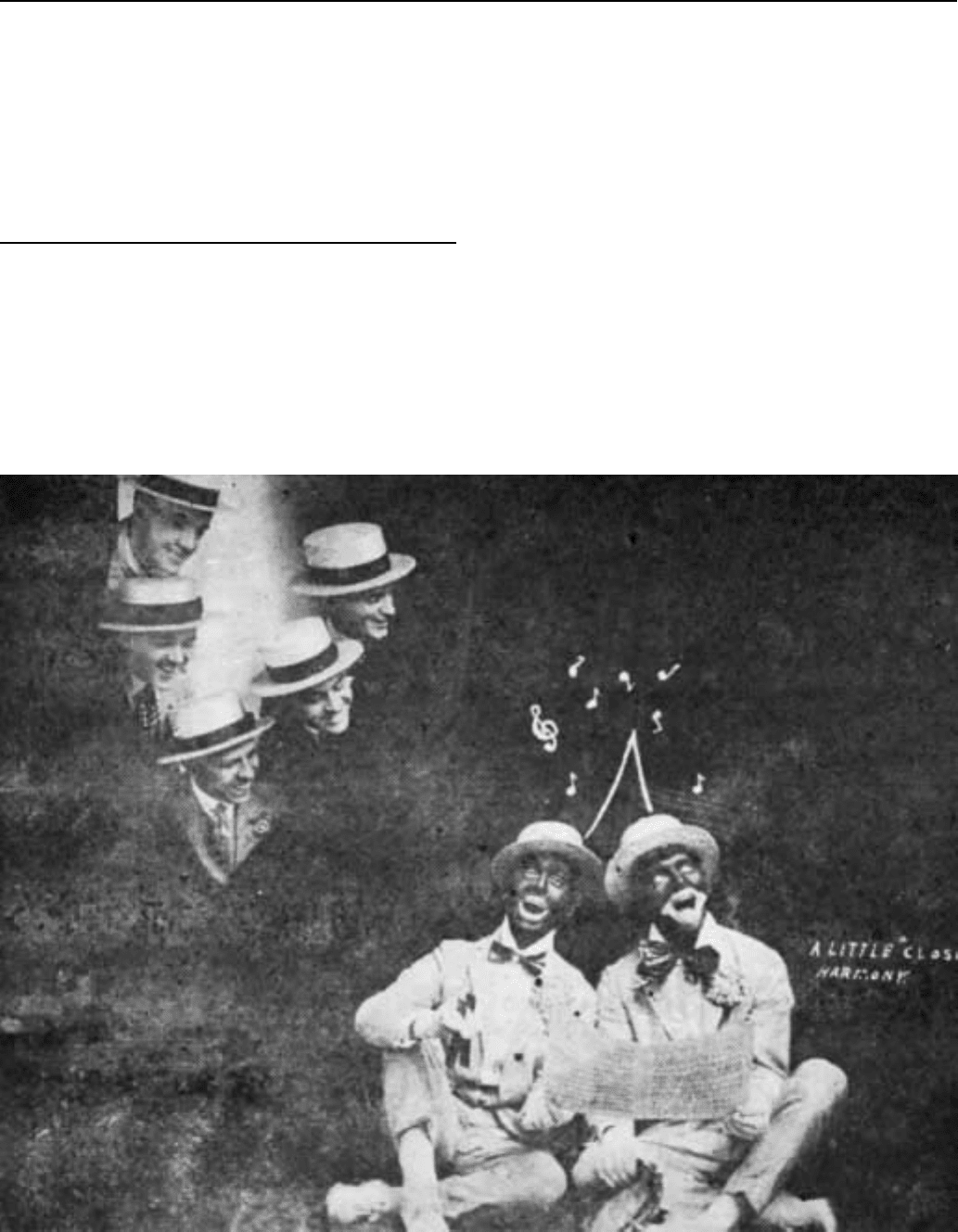

An example of blackface minstrelsy.

castanets, the fiddle, and the tambourine. They sang, danced, told

malapropistic jokes, cross-dressed for ‘‘wench’’ routines, and gave

comical stump speeches. From the late 1820s on, blackface minstrelsy

dominated American popular entertainment. Americans saw it on the

stages of theaters and circuses, read about it in the popular novels of

the nineteenth century, heard it over the radio, and viewed it on film

and television. Blackface minstrelsy can certainly be viewed as the

commodification of racist stereotypes, but it can also be seen as the

white fascination with and appropriation of African American cultur-

al traditions that culminated in the popularization of jazz, the blues,

rock ’n’ roll, and rap music.

While there are accounts of blackface minstrel performances

before the American Revolution, the performance style gained wide-

spread appeal in the 1820s with the ‘‘Jump Jim Crow’’ routine of

Thomas Dartmouth Rice. Rice is frequently referred to as ‘‘the father

of blackface minstrelsy.’’ In 1828 Rice, a white man, watched a black

Louisville man with a deformed right shoulder and an arthritic left

knee as he performed a song and dance called ‘‘Jump Jim Crow.’’

Rice taught himself the foot-dragging dance steps, mimicked the

BLACKFACE MINSTRELSYENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

271

disfigurement of the old man, copied his motley dress, and trained

himself to imitate his diction. When Rice first performed ‘‘Jump Jim

Crow’’ in blackface during an 1828 performance of The Rifle in

Louisville, Kentucky, the audience roared with delight. White audi-

ence members stopped the performance and demanded that Rice

repeat the routine over 20 times. It is impossible to overstate the

sensational popularity which Rice’s routine enjoyed throughout the

1830s and 1840s. Gary D. Engle has aptly described Rice as ‘‘Ameri-

ca’s first entertainment superstar.’’ When Rice brought his routine to

New York City’s Bowery Theater in 1832, the audience again

stopped the show and called him back on stage to repeat the routine

multiple times. He took his routine to England in 1836 where it was

enthusiastically received, and he spawned a bevy of imitators who

styled themselves ‘‘Ethiopian Delineators.’’

In 1843 four of these ‘‘Ethiopian Delineators’’ decided to create

a blackface minstrel troupe. They were the first group to call them-

selves ‘‘Minstrels’’ instead of ‘‘Delineators,’’ and their group The

Virginia Minstrels made entertainment history when it served as the

main attraction for an evening’s performance. Previous blackface

shows had been performed in circuses or between the acts of plays.

The troupe advertised its Boston debut as a ‘‘Negro Concert’’ in

which it would exhibit the ‘‘Oddities, peculiarities, eccentricities, and

comicalities of that Sable Genus of Humanity.’’ Dan Emmett played

the violin, Frank Brower clacked the ‘‘bones’’ (a percussion instru-

ment similar to castanets), Billy Whitlock strummed the banjo, and

Dick Pelham beat the tambourine. Their show consisted of comedy

skits and musical numbers, and it enjoyed a six week run in Boston

before traveling to England. Dozens of imitators attempted to trade on

its success. One of the most famous was Christy’s Minstrels, which

opened in New York City in 1846 and enjoyed an unprecedented

seven year run. During the 1840s blackface minstrelsy became the

most popular form of entertainment in the nation. Americans who saw

performances were captivated by them. ‘‘Everywhere it played,’’

writes Robert Toll, ‘‘minstrelsy seemed to have a magnetic, almost

hypnotic impact on its audiences.’’

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published

serially between 1851 and 1852, sold over 300,000 copies in its first

year in part because it traded on the popularity of blackface minstrelsy.

The book opens with a ‘‘Jump Jim Crow’’ routine, incorporates

blackface malapropistic humor, gives its readers a blackface minstrel

dancer in Topsy, and its hero Uncle Tom sings doleful hymns drawn

from the blackface minstrel tradition. Indeed, Stowe’s entire novel

can be read as a blackface minstrel performance in which a white New

England woman ‘‘blacks up’’ to impersonate Southern slaves.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was immediately adapted for the stage. It not

only became the greatest dramatic success in the history of American

theater, but it also quickly became what Harry Birdoff called ‘‘The

World’s Greatest Hit.’’ ‘‘Tom shows’’ were traveling musical revues

of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that continued the traditions of blackface

minstrelsy. One historian has described them as ‘‘part circus and part

minstrel show.’’ They featured bloodhounds chasing Eliza across the

ice (a stage addition not present in Stowe’s novel), trick alligators,

performing donkeys, and even live snakes. One 1880 performance

included 50 actors, 12 dogs, a mule, and an elephant. The ‘‘Tom

shows’’ competed directly with the traveling circuses of Barnum

and Bailey.

After Thomas Edison’s invention of moving picture technology

in 1889, film versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin with whites in blackface

were some of the very first films ever made. In 1903 Sigmund Lubin

produced a film version of the play, and on July 30 of that same year

Edison himself released a 1-reel version directed by Edwin S. Porter.

Edison’s film included 14 scenes and a closing tableaux with Abra-

ham Lincoln promising to free the slaves. In 1914 Sam Lucas was the

first black man to play Uncle Tom on screen.

Blackface minstrelsy remained on the leading edge of film

technology with the advent of ‘‘talkies.’’ The first ‘‘talkie’’ ever

made was The Jazz Singer in 1927, starring Al Jolson as a blackface

‘‘Mammy’’ singer. The movie’s debut marked the beginning of

Jolson’s successful film career. A list of other film stars of the 1930s

and 1940s who sang and danced in blackface is a Who’s Who of the

period. Fred Astaire played a blackface minstrel man in RKO’s movie

Swing Time (1936). Martha Raye put on blackface for Paramount

Pictures’ Artists and Models (1937). Metro Goldwyn Mayer’s 1939

movie Babes in Arms closed with a minstrel jubilee in which Mickey

Rooney blacked up to sing ‘‘My Daddy was a Minstrel Man,’’ and

Judy Garland of Wizard of Oz fame blacked up with Rooney in the

1941 sequel Babes on Broadway. Bing Crosby blacked up to play

Uncle Tom in Irving Berlin’s film Holiday Inn (1942), and Betty

Grable, June Haver Leonard, and George M. Cohan were just a few of

the other distinguished actors of the period who sang and danced

in blackface.

The most successful blackface minstrel show of the twentieth

century was not on the silver screen but over the radio waves. The

Amos ’n Andy Show began as a vaudeville blackface act called Sam ’n

Henry, performed by Freeman Fisher Gosden and Charles James

Correll. In 1925 the Sam ’n Henry radio show was first broadcast over

Chicago radio. In 1928 the duo signed with Chicago radio station

WMAQ and in March of that year they introduced the characters

Amos and Andy. The show quickly became the most popular radio

show in the country. In 1930 Gosden and Correll made the film Check

and Double Check, in which they appeared in blackface, and in 1936

they returned to the silver screen for an encore.

The 15 minute version of The Amos ’n’ Andy Show ran from

1928 until 1943, and it was by far the most listened to show during the

Great Depression. Historian William Leonard writes that ‘‘America

came virtually to a standstill six nights a week (reduced to five nights

weekly in 1931) at 7:00 pm as fans listened to the 15-minute

broadcast.’’ In 1943 the radio show became a 30 minute program, and

in 1948 Gosden and Correll received $2.5 million to take the show

from NBC to CBS. In the late 1940s popular opinion began to shift

against blackface performances, and Gosden and Correll bristled

under criticism that they were propagating negative stereotypes of

African Americans.

In 1951 The Amos and Andy Show first appeared on television,

but with an all-black cast—it made television history as the first

drama to have an all-black cast. The NAACP (National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People) opposed the show, however,

claiming that it demeaned blacks and hindered the Civil Rights

Movement. It was canceled on June 11, 1953, but it remained in

syndication until 1966.

African Americans have long objected to the stereotypes of the

‘‘plantation darky’’ presented in blackface minstrel routines. Freder-

ick Douglass expressed African American frustration with the phe-

nomenon as early as 1848 when he wrote in the North Star that whites

who put on blackface to perform in minstrel shows were ‘‘the filthy

scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied

to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt

taste of their white fellow citizens.’’ Douglass was incensed that

whites enslaved blacks in the South, discriminated against them in the

North, and then had the temerity to pirate African American culture

BLACKLISTING ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

272

for commercial purposes. While blackface minstrelsy has long been

condemned as racist, it is historically significant as an early example

of the ways in which whites appropriated and manipulated black

cultural traditions.

—Adam Max Cohen

F

URTHER READING:

Engle, Gary D. This Grotesque Essence: Plays from the Ameri-

can Minstrel Stage. Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University

Press, 1978.

Leonard, William Torbert. Masquerade in Black. Metuchen, New

Jersey, Scarecrow Press, 1986.

Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American

Working Class. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993.

Nathan, Hans. Dan Emmet and the Rise of Early Negro Minstrelsy.

Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1962.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-

Century America. London, Oxford University Press, 1974.

Wittke, Carl. Tambo and Bones: A History of the American Minstrel

Stage. Durham, North Carolina, Duke University Press, 1930.

Blacklisting

In 1947, the House Committee on Un-American Activities

(HUAC), chaired by J. Parnell Thomas, held a series of hearings on

alleged communist infiltration into the Hollywood motion picture

industry. Twenty-four ‘‘friendly’’ witnesses—including Gary Coop-

er, Ronald Reagan, and Walt Disney—testified that Hollywood was

infiltrated with communists, and identified a number of supposed

subversives by name. Ten ‘‘unfriendly’’ witnesses—including Dal-

ton Trumbo, Lester Cole, and Ring Lardner, Jr.—refused to cooperate

with the Committee, contending that the investigations themselves

were unconstitutional. The ‘‘Hollywood Ten,’’ as they came to be

known, were convicted of contempt of Congress and eventually

served sentences of six months to one year in jail.

Shortly after the hearings, more than 50 studio executives met

secretly at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York. They emerged

with the now infamous ‘‘Waldorf Statement,’’ with which they

agreed to suspend the Hollywood Ten without pay, deny employment

to anyone who did not cooperate with the HUAC investigations, and

refuse to hire communists. When a second round of hearings con-

vened in 1951, the Committee’s first witness, actor Larry Parks,

pleaded: ‘‘Don’t present me with the choice of either being in

contempt of this Committee and going to jail or forcing me to really

crawl through the mud to be an informer.’’ But the choice was

presented, the witness opted for the latter, and the ground rules for the

decade were set.

From that day forward, it was not enough to answer the question

‘‘Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist

Party?’’ Rather, those called to testify were advised by their attorneys

that they had three choices: to invoke the First Amendment, with its

guarantee of free speech and association, and risk going to prison like

the Hollywood Ten; to invoke the Fifth Amendment, with its privi-

lege against self-incrimination, and lose their jobs; or to cooperate

with the Committee—to ‘‘purge’’ themselves of guilt by providing

the names of others thought to be communists—in the hope of

continuing to work in the industry. By the mid-1950s, more than 200

suspected communists had been blacklisted by the major studios.

The Hollywood blacklist quickly spread to the entertainment

industries on both coasts, and took on a new scope with the formation

of free enterprise blacklisters such as American Business Consultants

and Aware, Inc., which went into the business of peddling accusations

and clearances; and the publication of the manual Red Channels and

newsletter Counterattack, which listed entertainment workers with

allegedly subversive associations. Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-

Wisconsin), who built his political career on red-baiting and finally

lent his name to the movement, was censured by the U.S. Senate in

1954. But the blacklist went virtually unchallenged until 1960, when

screenwriter Dalton Trumbo worked openly for the first time since

1947. And it affected others, like actor Lionel Stander, well into the

1960s. The House Committee on Un-American Activities remained

in existence until 1975.

That the HUAC investigations were meant to be punitive and

threatening rather than fact-finding is evidenced by the Committee’s

own eventual admission that it already had the information it was

allegedly seeking. According to Victor Navasky, witnesses such as

Larry Parks were called upon not to provide information that would

lead to any conviction or acquittal, but rather to play a symbolic role

in a surrealistic morality play. ‘‘The Committee was in essence

serving as a kind of national parole board, whose job was to determine

whether the ‘‘criminals’’ had truly repented of their evil ways. Only

by a witness’s naming names and giving details, it was said, could the

Committee be certain that his break with the past was genuine. The

demand for names was not a quest for evidence; it was a test of

character. The naming of names had shifted from a means to an end.’’

The effects of the blacklist on the Hollywood community were

devastating. In addition to shattered careers, there were broken

marriages, exiles, and suicides. According to Navasky, Larry Parks’

tortured testimony and consequent controversiality resulted in the end

of a career that had been on the brink of superstardom: ‘‘His

memorable line, ’Do not make me crawl through the mud like an

informer,’ was remembered, and the names he named were forgotten

by those in the blacklisting business.’’ Actress Dorothy Comingore,

upon hearing her husband on the radio testifying before the Commit-

tee, was so ashamed that she had her head shaved. She lost a bitter

custody battle over their child and never worked again. Director

Joseph Losey’s last memory was of hiding in a darkened home to

avoid service of a subpoena. He fled to England. Philip Loeb, who

played Papa on The Goldbergs, checked into a room at the Hotel Taft

and swallowed a fatal dose of sleeping pills.

There was also resilience, courage, and humor. Blacklisted

writers hired ‘‘fronts’’ to pose as the authors of their scripts, and

occasionally won Academy Awards under assumed names. Sam

Ornitz urged his comrades in the Hollywood Ten to be ‘‘at least be as

brave as the people we write about’’ as they faced prison. Dalton

Trumbo sardonically proclaimed his conviction a ‘‘completely just

verdict’’ in that ‘‘I did have contempt for that Congress, and have had

contempt for several since.’’ Ring Lardner, Jr., recalled becoming

‘‘reacquainted’’ with J. Parnell Thomas at the Federal Correctional

Institution in Danbury, Connecticut, where Thomas was already an

inmate, having been convicted of misappropriating government funds

while Lardner exhausted his appeals.

Many years later, in an acceptance speech for the highest honor

bestowed by the Screenwriters Guild, the Laurel Award, Dalton

Trumbo tried to bring the bitterness surrounding the blacklist to an

end. ‘‘When you [. . . ] look back with curiosity on that dark time, as I

BLADE RUNNERENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

273

think occasionally you should, it will do no good to search for villains

or heroes or saints or devils because there were none,’’ he said, ‘‘there

were only victims. Some suffered less than others, some grew and

some diminished, but in the final tally we were all victims because

almost without exception each of us felt compelled to say things he

did not want to say, to do things he did not want to do, to deliver and

receive wounds he truly did not want to exchange. That is why none of

us—right, left, or center—emerged from that long nightmare without

sin. None without sin.’’

Trumbo’s ‘‘Only Victims’’ speech, delivered in 1970, was

clearly meant to be healing. Instead, it rekindled a controversy that

smoldered for years, with other members of the Hollywood Ten

bristling at his sweeping conviction and implied pardon of everyone

involved. The social, psychological, legal, and moral ramifications of

the Hollywood blacklist have haunted American popular memory for

more than half a century. The blacklist has been the subject of

numerous books, plays, documentaries, and feature films, the titles of

which speak for themselves: Thirty Years of Treason, Scoundrel

Time, Hollywood on Trial, Fear on Trial, Are You Now Or Have You

Ever Been, Hollywood’s Darkest Days, Naming Names, Tender

Comrades, Fellow Traveler, and Guilty By Suspicion, to name a few.

In 1997, the New York Times reported that ‘‘The blacklist still

torments Hollywood.’’ On the 50th anniversary of the 1947 hearings,

the Writers Guild of America, one of several Hollywood unions that

failed to support members blacklisted in the 1950s, announced that it

was restoring the credits on nearly 50 films written by blacklisted

screenwriters. There was talk of ‘‘putting closure to all of this’’ and

feeling ‘‘forgiveness in the air.’’ At the same time, however, a debate

raged in the arts and editorial pages of the nation’s newspapers over

whether the Los Angeles Film Critics Association and the American

Film Institute were guilty of ‘‘blacklisting’’ director Elia Kazan.

Kazan appeared before the Committee in 1952 and informed on eight

friends who had been fellow members of the Communist Party. His

On the Waterfront is widely seen as a defense of those who named

names. As Peter Biskind remarks, the film ‘‘presents a situation in

which informing on criminal associates is the only honorable course

of action for a just man.’’

Variety advocated a lifetime achievement award for Kazan,

describing him as ‘‘an artist without honor in his own country, a

celebrated filmmaker whose name cannot be mentioned for fear of

knee-jerk reactions of scorn and disgust, a two-time Oscar winner not

only politically incorrect but also politically unacceptable according

to fashion and the dominant liberal-left Hollywood establishment.’’

But as the New York Times pointed out, ‘‘Not only did [Kazan] name

names, causing lasting damage to individual careers, but he lent his

prestige and moral authority to what was essentially an immoral

process, a brief but nevertheless damaging period of officially spon-

sored hysteria that exacted a huge toll on individual lives, on free

speech, and on democracy.’’ Kazan accepted his lifetime achieve-

ment award at the Academy Awards in 1999.

—Jeanne Hall

F

URTHER READING:

Benson, Thomas. ‘‘Thinking through Film: Hollywood Remembers

the Blacklist.’’ In Rhetoric and Community: Studies in Unity and

Fragmentation, edited by J. Michael Hogan. Columbia, Universi-

ty of South Carolina Press, 1998.

Bernstein, Walter. Inside Out: A Memoir of the Blacklist. New York,

Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Biskind, Peter. ‘‘The Politics of Power in On The Waterfront.’’ In

American Media and Mass Culture: Left Perspectives, edited by

Donald Lezere. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1985.

Ceplair, Larry, and Steven Englund. The Inquisition in Hollywood:

Politics in the Film Community 1930-1960. Garden City, Anchor

Press/Doubleday, 1980.

McGilligan, Patrick, and Paul Buhle. Tender Comrades: A Backstory

of the Blacklist. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Navasky, Victor S. Naming Names. New York, Viking Press, 1980.

Blade Runner

Ridley Scott’s 1982 film adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s science

fiction novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) received

poor reviews when it opened. It did not take long, however, for Blade

Runner to become known as one of the greatest science fiction films

ever made. The film’s depiction of Los Angeles in the year 2019

combines extrapolated social trends with technology and the darkness

of film noir to create the movie that gave Cyberpunk literature its

visual representation.

In true film noir style, the story follows Rick Deckard (Harrison

Ford), who is a ‘‘Blade Runner,’’ a hired gun whose job is to retire

(kill) renegade ‘‘replicants’’ (androids who are genetically designed

as slaves for off-world work). The story revolves around a group of

replicants who escape from an off-world colony and come to earth to

try to override their built in four-year life span. Deckard hunts the

replicants, but he falls in love with Rachael (Sean Young)—an

experimental replicant. Deckard finally faces the lead replicant (Rutger

Hauer) in a struggle that ends with him questioning his own humanity

and the ethics of his blade running.

The production of Blade Runner was not without problems.

Hampton Fancher had written the screenplay that offered a much

darker vision than Dick’s novel and only drew on its basic concepts.

After the success of Alien (1979), Ridley Scott showed interest in

directing the film. Scott replaced Fancher with David Peoples after

eight drafts of the script. Scott’s goal was to rework the script to be

less action-oriented with a plot involving ‘‘clues’’ and more human-

like adversaries. He worked closely with Douglas Trumbull—2001:

A Space Odyssey—to design an original visual concept. Although

some of the actors flourished under Scott’s directing style, many were

frustrated with his excessive attention to the set design and lighting.

Eventually, the production company that was supporting the film

pulled out after spending two million dollars. New funding was

provided by three interests—a subsidiary of Warner Brothers, Run

Run Shaw, and Tandem Productions (which gained rights to control

the final version).

Preview audiences were befuddled by the film’s ambiguous

resolution and frustrated by the lack of light-hearted action they

expected from Harrison Ford. The response was so weak that Tandem

Productions decided to change the film. Scott was forced to include

voice-overs, and to add a ‘‘feel good’’ ending in which Deckard and

Rachael drive off into Blade Runner’s equivalent of a sunset.

The film opened strong at the box office, but critics railed against

the voice-overs and the happy ending. The release of Steven Spielberg’s

E.T.: The Extra Terrestrial, within two weeks of Blade Runner,

eclipsed the film and ended its theater run. Blade Runner has,

BLADE RUNNER ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

274

Harrison Ford in a scene from the film Blade Runner.

however, endured. In 1993, the National Film Preservation Board

selected to preserve Blade Runner as one of its annual 25 films

deemed ‘‘culturally, historically, or aesthetically important.’’ The

British Film Institute also included Blade Runner in its Modern

Classics series.

Part of Blade Runner’s success is due to its serious treatment of

important philosophical and ethical questions. Some look at Blade

Runner as a rehashing of Frankenstein. In true Cyberpunk style,

though, the monsters have already escaped and there is an explicit

question about whether humans are the real monsters. Blade Runner

goes beyond that, asking hard questions about religion, the ethics of

genetic manipulation, racism and sexism, and human interaction with

technology. The film also presents two other major questions: ‘‘What

is it to be human?’’; and ‘‘How should our society handle its

’kipple?’’’—the accumulating garbage (especially human ‘‘kipple’’).

These issues are so thought provoking that Blade Runner has become

one of the most examined films in academic circles.

Blade Runner is often touted as the primary visual manifestation

of the Cyberpunk movement and the first Cyberpunk film. The film

predated the beginning of the Cyberpunk movement (William Gib-

son’s Neuromancer), however, by two years. Hallmark themes of

Cyberpunk fiction are the merging of man with machine and a dark,

morbid view of the near future mixed with the delight of new

technology. With dark and bleak imagery and androids that are

‘‘more human than human,’’ it is not surprising that Blade Runner

became a Cyberpunk watershed, offering a hopeful vision of what

technology can do and be.

In 1989, Warner Brothers uncovered a 70mm print of Blade

Runner and showed it to an eager audience at a film festival. The

studio showed this version in two theaters in 1991, setting house

attendance records and quickly making them two of the top-grossing

theaters in the country. Warner Brothers agreed to fund Scott’s

creation of a ‘‘director’s cut’’ of the film. Scott reworked the film and

re-released it in 1992 as Blade Runner: The Director’s Cut. The

voice-overs were taken out, the happy ending was cut, and Scott’s

‘‘unicorn’’ scene was reintegrated.

Because this film was initially so poorly received, no film or

television sequels resulted. Blade Runner did, however, vault Dick’s

BLADESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

275

books past their previous recognition. It also spawned two book

sequels by K.W. Jeter both of which received marginal reviews. In

1997, Westwood Studios released the long-awaited CD-ROM game.

The Internet bustles with dozens of pages dedicated to the film and

discussion groups, which never tire of examining the movie.

Blade Runner’s most important contribution has been to the film

and television industries, creating a vision of the future that has

continued to resonate in the media. Scott’s dystopian images are

reflected in films and television shows such as Robocop, Brazil, Total

Recall, Max Headroom, Strange Days, and Dark City. Blade Runner

has become one of the standards for science fiction imagery, standing

right beside Star Wars and 2001: A Space Odyssey. Many reviewers

still use Blade Runner as the visual standard for science fiction

comparisons. It has survived as a modern cult classic and it will

certainly impact our culture for a long time to come.

—Adam Wathen

F

URTHER READING:

Albrecht, Donald. ‘‘’Blade Runner’ Cuts Deep into American Cul-

ture.’’ The New York Times. September 20, 1992, sec. 2, p. 19.

‘‘’Blade Runner’ and Cyberpunk Visions of Humanity.’’ Film Criti-

cism. Vol. 21, No. 1, 1996, pp. 1-12.

Bukatman, Scott. Blade Runner. London, British Film Institute, 1997.

Clute, John, and Peter Nicholls, editors. ‘‘Blade Runner.’’ The

Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York, St. Martin’s

Press, 1993.

Kerman, Judith B., editor. Retrofitting Blade Runner: Issues in Ridley

Scott’s Blade Runner and Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of

Electric Sheep? Bowling Green, Ohio, Bowling Green State

University Popular Press, 1991.

McCarty, John. ‘‘Blade Runner.’’ International Dictionary of Films

and Filmmakers. Vol. 1, Detroit, St. James Press, 1997.

Romney, Jonathan. ‘‘Replicants Reshaped.’’ New Statesman & So-

ciety. Vol. 5, No. 230, 1992, pp. 33-34.

Sammon, Paul M. Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner. New

York, HarperPrism, 1996.

Turan, Kenneth. ‘‘Blade Runner 2.’’ Los Angeles Times Magazine.

September 13, 1992, 19.

Blades, Ruben (1948—)

Musician, actor, and social activist Ruben Blades grew up in

Panama and grew to international fame in the United States, becom-

ing in the process a perfect example of the multiculturalism of the

Americas. Accepting as correct both the Spanish and English

pronunciations of his last name, Blades likewise accepts the different

facets of himself and demands no less of the greater culture that

surrounds him. Overcoming enormous odds, Blades managed to

juggle simultaneous careers as a lawyer, a salsa musician, a Holly-

wood actor, and finally a presidential candidate while maintaining his

principles of social justice and pan-culturalism.

Blades was born in Panama City into a musical family; his

father, a police detective, played bongos, and his Cuban-born mother

sang and played piano. Along with the Afro-Cuban rhythms he grew

up with, Blades was heavily influenced by the rock music of the

Beatles, Frankie Lyman, and others. After studying law at the

University of Panama (‘‘to please my parents’’), he began playing

music with a band. In 1974, disenchanted with the political oppres-

sion of the military dictatorship in Panama and seeking new horizons

in his music career, Blades left his native land and went to New

York City.

He arrived in New York with only one hundred dollars in his

pocket, but it wasn’t long before he had found a job in a band playing

salsa music. Salsa, a pan-American music which had been formed

when the music of Cuban immigrants married American jazz, was

just the kind of flexible Latin sound to absorb the rock and rhythm and

blues influences that Blades loved. By the late 1970s, he was

recording with salsa musician Willie Colon, and together they pro-

duced an album appropriately named Siembre (Seed), which became

one of the seminal works of salsa music.

Blades also comes by his political activism naturally; his grand-

mother worked for women’s rights in Panama in the 1940s and 1950s.

Though Blades loved music, he never let it become an escape; rather

he used it in his attempt to change the world, writing more than one

hundred fifty songs, most of them political. He became one of the

leading creators of the Nuova Cancion (New Song) movement , a

Latin music movement that combined political message with poetic

imagery and Latin rhythms. His songs, while embraced by those on

the left, were often controversial in more conservative circles. His

1980 song ‘‘Tiberon’’ (Shark) about the intervention and imperialism

of the superpowers, was banned on radio stations in Miami, and

Blades received death threats when he performed there.

After taking a year off to earn a master’s degree in international

law from Harvard Law School, Blades moved from New York to Los

Angeles in 1986. He starred in the low budget film Crossover Dreams

(1985) about a young Latin American man trying to succeed as a

musician in the United States. Blades proved to be a talented actor and

continues to appear in major films, some, like Robert Redford’s The

Milagro Beanfield War (1988), with social significance and some,

like Fatal Beauty (1987) with Whoopi Goldberg, pure Hollywood.

Perhaps Blades’s most surprising role began when he returned to

Panama in 1992. As the country was struggling to recover from the

repressive politics of Manuel Noriega and invasion by the United

States, Blades helped in the formation of a new populist political party

to combat the dominant corporation-driven politics of Panama. The

party, Papa Egoro (Mother Earth in the indigenous language), eventu-

ally asked Blades to be its candidate for president. Blades accepted

reluctantly but ran enthusiastically, writing his own campaign song

and encouraging his constituents to believe that change was possible.

‘‘I’m going to walk with the people who are the subjects of my

songs,’’ he said, ‘‘And I’m going to try to change their lives.’’ One

significant change he suggested was a requirement that a percentage

of the corporate money that passed through Panama be invested back

into the infrastructure of the country to benefit ordinary citizens.

Blades lost his bid for the presidency, partly because of lack of

campaign funds and a political machine, and partly because he had

not lived in Panama for many years and was not taken seriously as a

candidate by some voters. However, he came in third out of seven

BLANC ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

276

Ruben Blades

candidates, which many saw as a hopeful sign of a growing

populist movement.

Ruben Blades’s life and career is an eclectic jumble of impossi-

ble feats and improbable juxtapositions. In the superficial world of

commercial music and Hollywood film he has succeeded without

neutralizing his politics. In the endless freeway that is Los Angeles he

has never learned to drive or owned a car (‘‘If I need something, it’s

only an hour-and-a-half walk to town’’). His many releases include an

album with Anglo singers singing with him in Spanish, an English

album with rock rebels Lou Reed and Elvis Costello, and an album of

contemporary Panamanian singers. Blades is proudly pan-American

and wants to inspire all Americans to explore our connections. ‘‘I will

always be viewed with suspicion by some, though not by all,’’ he

admits, ‘‘because I move against the current.’’

—Tina Gianoulis

F

URTHER READING:

Batstone, David. ‘‘Panama’s Big Chance to Escape the Past: Politics,

Promises Take Center Stage as Election Draws Near.’’ National

Catholic Reporter. Vol. 30, No. 27, May 6, 1994, 8.

Blades, Ruben. Yo, Ruben Blades: Confesiones de un Relator de

Barrio. Panama City, Medellin, Ediciones Salsa y Cultura, 1997.

Cruz, Barbara. Ruben Blades: Salsa Singer and Social Activist.

Springfield, New Jersey, Enslow Publishing, 1997.

Marton, Betty A. Ruben Blades. New York, Chelsea House, 1992.

Blanc, Mel (1908-1989)

Mel Blanc, the ‘‘Man of a thousand voices,’’ helped to develop

animated cartoons into a new comedic art form by creating and

performing the voices of hundreds of characters for cartoons, radio,

and television.

Melvin Jerome Blanc was born on May 30, 1908 in San

Francisco, California, to Frederick and Eva Blank, managers of a

women’s retail clothing business. A poor student and class cut-up,

Blanc was popular with his peers but often annoyed his teachers and

principals. At age 16, goaded by an insult from a teacher, Blanc

changed the spelling of his last name from ‘‘Blank’’ to ‘‘Blanc.’’

Blanc had made his class laugh by giving a response in four different

voices, and the incensed teacher said, ‘‘You’ll never amount to

anything. You’re just like your last name: blank.’’ Nonetheless, high

school gave Blanc some opportunity to practice future material. For

example, he took advantage of the great acoustics of the school’s

cavernous hallways to develop the raucous laugh that eventually

became Woody Woodpecker’s signature.

After graduating from high school in 1927, Blanc started work-

ing part-time in radio, on a Friday evening program called The Hoot

Owls, and playing tuba with two orchestras. He then went on to play in

the NBC Trocaderans radio orchestra. By age 22 he was the youngest

musical director in the country, working as the pit conductor for

Oregon’s Orpheum Theatre. In 1931, Blanc returned to San Francisco

to emcee a Tuesday night radio variety show called ‘‘The Road

Show.’’ The next year, he set out for Hollywood, hoping to make it

big. Although his first foray into Tinseltown did not bring him much

professional success, it did wonders for his personal life. In 1933,

Blanc eloped with Estelle Rosenbaum, whom he had met while

swing-dancing at the Ocean Park Ballroom in Santa Monica. The

couple moved to Portland, Oregon, where Blanc (with help from

Estelle) wrote, produced, and acted in a live, hour-long radio show,

Cobwebs and Nuts.

In 1935, Blanc and his wife returned to Hollywood to try again.

By 1941, Blanc’s career as a voice actor had sky-rocketed. In 1936, he

joined Warner Brothers, brought on to create a voice for an animated

drunken bull for an upcoming production called Picador Porky, and

starring Porky Pig. But soon afterward, Blanc was asked to replace the

actor who provided Porky Pig’s voice. In his first demonstration of his

new creation, Blanc ad-libbed the famous ‘‘Th-uh-th-uh-th-that’s all,

folks!’’ Released in 1937, Picador Porky was Blanc’s first cartoon for

Warner Brothers. That same year, Blanc created his second lead

character for Warner, Daffy Duck. Around this time, he also changed

the way cartoons were recorded by suggesting that each character’s

lines be recorded separately and then reassembled in sequence. In

1940, Blanc helped create the character with whom he is most closely

associated, Bugs Bunny. Bugs had been around in different forms for

several years as ‘‘Happy Rabbit,’’ but Blanc re-christened him after

his animator, Ben ‘‘Bugs’’ Hardaway, and gave him a tough-edged

Brooklyn accent. Bugs also provided the inspiration for the most

famous ad-lib of his career, ‘‘Eh, what’s up Doc?’’ Blanc completed

the character by chewing on raw carrots, a vegetable which he

detested. Unfortunately, other fruits and vegetables did not produce

the right sound. In addition, Blanc found it impossible to chew,

swallow, and say his next line. The solution? They stopped recording

so that Blanc could spit the carrot into the wastebasket before

continuing with the script.

BLANCENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

277

Mel Blanc

In 1945, the studio introduced a romantic lead for Blanc, the

skunk Pepe Le Pew. Blanc modeled the character on French matinee

idol Charles Boyer, and received amorous fan mail from women who

loved the character’s accent. The final leading character that Blanc

created for Warner Brothers was Speedy Gonzales, the Mexican

mouse, the studio’s most prolific character in its final years. Of the

Warner Brothers characters, Blanc has described the voice of Yo-

semite Sam as the most difficult to perform, saying that it was like

‘‘screaming at the top of your lungs for an hour and a half.’’ Another

voice that required a lot of volume was Foghorn Leghorn. His easiest

character, and one of his favorites, was Sylvester the Cat. According

to Blanc, this voice is closest to his natural speaking voice, but

‘‘without the thspray.’’ In his autobiography, Blanc revealed one of

the little known tricks used by engineers to manipulate the voices for

characters such as Daffy Duck, Henery Hawk, Speedy Gonzales, and

Tweety. Using a variable-speed oscillator, lines were recorded below

normal speed and then played back conventionally, which raised the

pitch of the voices while retaining their clarity.

While at Warner Brothers Blanc worked with a talented group of

animators, producers, and directors that included Friz Freleng, Milt

Avery, Chuck Jones, and Leon Schlessinger. The studio’s work

earned five Oscars for cartoons. The first award came in 1947 for

Tweety Pie, starring Sylvester and Tweety. Blanc calls the 1957 Oscar

winner Birds Anonymous his all-time favorite cartoon, and producer

Eddie Selzer bequeathed its Oscar to Blanc upon his death (cartoon

Oscars are only awarded to producers). By the time Warner Brothers

closed its animation shop in 1969, Blanc had performed around 700

human and animal characters, and created voices for 848 of the

studio’s 1,003 cartoons. He also negotiated an unprecedented screen

credit that enabled him to get freelance work with other studios and

programs. In addition, Blanc occasionally acted as a dialect coach to

film stars such as Clark Gable.

During World War II, Blanc appeared on several Armed Forces

Radio Service programs, such as G.I. Journal, featuring his popular

character Private Sad Sack. Hollywood legends who appeared on the

show with Blanc included Lucille Ball, Groucho Marx, Frank Sinatra,

and Orson Welles. Warner Brothers also produced several war-

related cartoons such as Wacky Blackouts and Tokyo Jokio. In 1946,

CBS and Colgate-Palmolive offered Blanc his own show, but it lasted

only one season, due, in Blanc’s opinion, to ‘‘lackluster scripts.’’

After leaving Warner Brothers, Blanc returned to broadcast full-

time. One of his most well-known roles was a dour, forlorn character

comically misnamed ‘‘The Happy Postman’’ who appeared on The

George Burns and Gracie Allen Show. In 1939, Blanc joined the cast

of Jack Benny’s popular radio show on NBC. Blanc came to regard

Benny as his ‘‘closest friend in all of Hollywood.’’ On The Jack

Benny Program many jokes featured Blanc’s Union Depot train caller

who would call, ‘‘Train leaving on track five for Anaheim, Azusa,

and Cuc-amonga!’’ In one series of skits the pause between ‘‘Cuc’’

and ‘‘amonga’’ kept getting longer and longer until in one show a

completely different skit was inserted between the first and second

part of the phrase. In 1950, The Jack Benny Program made a

successful transition to television, ranking in the top 20 shows for ten

of the fifteen years it was on the air. Television provided even more

voice work for Blanc, who began to perform characters for cartoons

specifically produced for television. In 1960, Blanc received an offer

from the Hanna-Barbera studio to play the voice role of Barney

Rubble on a new animated series for adults called The Flintstones.

In 1961, Blanc and former Warner Brothers executive producer

John Burton started a commercial production company called Mel

Blanc Associates. Three days later, while driving to a radio taping,

Blanc was hit head-on by a car that lost control on the S-shaped bend

of Sunset Boulevard known as ‘‘Dead Man’s Curve.’’ Although the

other driver sustained only minor injuries, Blanc broke nearly every

bone in his body, lost nine pints of blood, and was in a coma for three

weeks. After regaining consciousness, he stayed an additional two

months in a full body cast. While in the hospital, he recorded several

tracks for Warner Brothers, and then had a mini-studio installed in his

home so that he could continue working while convalescing.

The Blanc’s only child, a son Noel was born in 1938. Blanc has

joked that he and his wife later realized that in French their son’s name

translated into ‘‘white Christmas,’’ which Blanc noted was ‘‘a hell of

a name for a Jewish boy.’’ At age 22, Blanc’s son Noel joined Mel

Blanc Associates, eventually becoming company president. Later,

Blanc taught his son the voices of the Warner Brothers characters, so

that he could carry on his legacy.

Mel Blanc Associates quickly became known for its humorous

commercials. Its client roster included Kool-Aid, Volkswagen, Ford,

and Avis Rent-a-car. They also began producing syndicated radio

programs. In conjunction with the company’s thirtieth anniversary,

the renamed Blanc Communications Corporation became a full-

service advertising agency. In 1972, Blanc established the Mel Blanc

School of Commercials, which offered six courses such as radio and

television voiceovers and commercial acting principles. Proving too

costly, however, the school only existed for two years. Meanwhile

Blanc continued to do voice-work for commercials and programs. In

1988, he had a bit part as Daffy Duck in the film Who Framed

Roger Rabbit.

BLAND ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

278

Both Blanc and Bugs Bunny have their own stars on the

Hollywood Walk of Fame (Blanc’s resides at 6385 Hollywood

Boulevard). Blanc has said that the honor of which he is most proud is

his inclusion in the United States entertainment history collection of

the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

Active in many philanthropic organizations, Blanc received a pletho-

ra of civic awards, including the United Jewish Welfare Fund Man

of the Year and the First Show Business Shrine Club’s Life

Achievement Award.

Although Blanc was a pack-a-day smoker, who started when he

was eight, a doctor who x-rayed Blanc’s throat compared it to the

musculature of Italian tenor Enrico Caruso. Blanc quit smoking later

in life when he developed severe emphysema and required portable

oxygen to breathe. In 1989, Blanc died at the age of 81 from heart

disease. The epitaph on his headstone in Hollywood Memorial Park

Cemetery reads, ‘‘That’s All Folks.’’

—Courtney Bennett

F

URTHER READING:

Blanc, M., and P. Bashe. That’s Not All Folks! New York, Warner

Books, Inc., 1988.

Feldman, P. ‘‘Mel Blanc Dies; Gave Voice to Cartoon World.’’ Los

Angeles Times. July 11, 1989, 1.

Bland, Bobby Blue (1930—)

Bobby Blue Bland played a significant role in the development

of the blues ballad. Generally ranked by blues fans in the highest

echelon of the genre, he specializes in slower, prettier tunes, while

remaining within the blues tradition. Bland, along with B. B. King,

emerged from the Memphis blues scene. Born in Rosemark, Tennes-

see, he moved to Memphis at seventeen, and began recording shortly

thereafter. During the 1950s, he developed his unique blues ballad

sound: in his performances, he walks a thin line between self-control

and ecstasy. In the 1960s, he had twelve major hits, including ‘‘I Pity

the Fool,’’ and the now standard ‘‘Turn on Your Love Light.’’

Overall, he has had 51 top ten singles. Bland has never become a

major crossover star, but still draws solid audiences on the blues

concert circuit.

—Frank A. Salamone

Blass, Bill (1922—)

Bill Blass was the first American designer to emerge from the

shadow of manufacturers and establish his name with authority. From

a base in womenswear design, Blass achieved a collateral success in

menswear with ‘‘Bill Blass for PBM’’ in 1968, another first for an

American. Blass then used licensing to expand his brand name

globally in a range of products from menswear to automobiles and

even to chocolates at one point. A shrewd observer of European style,

Blass used his talent to define American fashion, creating separates

for day and evening; sportswear with active sports as inspiration; and

the mix and match that allows customers to compose an individual

and chic style on their own. Blass was one of the first designers to

come out of the backroom of design, mingle with clients, and become

famous in his own right. To many, Blass is known as the ‘‘dean of

American fashion.’’

—Richard Martin

F

URTHER READING:

Daria, Irene. The Fashion Cycle. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1990.

Milbank, Caroline Rennolds. New York Fashion: The Evolution of

American Style. New York, Abrams, 1989.

Morris, Bernadine, and Barbara Walz. The Fashion Makers. New

York, Random House, 1978.

Blaxploitation Films

Blaxploitation films were a phenomenon of the 1970s. Low-

budget action movies aimed at African American audiences,

blaxploitation films enjoyed great financial success for several years.

Some blaxploitation pictures, such as Shaft and Superfly launched

music and fashion trends as well. Eventually the controversy sur-

rounding these movies brought an end to the genre, but not before

nearly one hundred blaxploitation films had been released.

Even during the silent movie period, producers had been making

films with all-black casts. An African American entrepreneur named

Pam Grier in a scene from Foxy Brown.