Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BIRTH OF A NATIONENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

259

Scene from the film The Birth of a Nation.

between the States. It hasn’t been told accurately in history books.’’

When the film was being shot at a lot on Sunset Boulevard in Los

Angeles, the first-time-ever use of artificial lighting to illuminate

battle scenes shot at night led to public fears that southern California

was under enemy attack from the sea.

Although some scenes depicted the early arrival of slaves in

America, the decades of the 1860s and 1870s—Civil War and

Reconstruction—constitute the historical timeframe of The Birth of a

Nation. The film includes enactments of several historical scenes,

such as Sherman’s march to the sea, the surrender at Appomattox, and

the assassination of Lincoln, but the narrative focuses almost exclu-

sively on the saga of two white dynasties, the Stonemans from the

North and the Camerons from the South, interlinked by romantic

attachments between the younger generations of the two families. An

early scene depicts the Cameron plantation in South Carolina as an

idyllic estate with benevolent white masters and happy slaves coexisting

in mutual harmony until undermined by abolitionists, Union troops,

and Yankee carpetbaggers. After the war, Austin Stoneman, the

family patriarch, dispatches a friend of mixed-race, Silas Lynch, to

abet the empowerment of ex-slaves by encouraging them to vote and

run for public office in the former Confederacy. A horrified Ben

Cameron organizes the Ku Klux Klan as an engine of white resist-

ance. The film’s unflattering depiction of uncouth African American

legislators and of Lynch’s attempt to coax Elsie Stoneman into a

mixed-race marriage fueled much controversy over the years for

reinforcing stereotypes about Negro men vis-à-vis the ‘‘flower of

Southern womanhood.’’ To create dramatic tension, Griffith juxta-

posed images of domestic bliss with unruly black mobs and used

alternating close-up and panoramic scenes to give a sense of move-

ment and to facilitate the emotional unfolding of the narrative. During

a climactic scene in which the Ku Klux Klan rides to the rescue of the

Cameron patriarch from his militant black captors, a title reads: ‘‘The

former enemies of North and South are united again in common

defense of their Aryan birthright.’’ Bowing to protests, Griffith

excised some of the more graphic scenes of anti-white violence before

the film’s premiere, and also added an epilogue, now lost, favorably

portraying the Hampton Institute, a prominent black school in Virgin-

ia. Interviewed by his biographer, Barnet Bravermann in 1941, D. W.

Griffith thought that The Birth of a Nation should, ‘‘in its present form

be withheld from public exhibition’’ and shown only to film profes-

sionals and students. Griffith said ‘‘If The Birth of a Nation were done

again, it would have to be made much clearer.’’

BIRTHING PRACTICES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

260

The title of the film remained The Clansman until a month

before its premiere, and was altered to its familiar title upon Dixon’s

own enthusiastic recommendation. Both Griffith and Dixon defended

their work against an avalanche of censorship threats, as in a letter by

Dixon to the Boston Journal (April 26, 1915), in which he wrote

‘‘This play was not written to stir race hatred. It is the faithful record

of the life of fifty years ago. It is no reflection on the cultured, decent

negro of today. In it are sketched good negroes and bad negroes, good

whites and bad whites.’’ Griffith also ardently defended his view-

point, as in a letter to the New York Globe (April 10, 1915) in which he

criticized ‘‘pro-intermarriage’’ groups like the NAACP for trying ‘‘to

suppress a production which was brought forth to reveal the beautiful

possibilities of the art of motion pictures and to tell a story which is

based upon truth in every vital detail.’’

The Birth of a Nation had its premiere at New York City’s

Liberty Theater on March 3, 1915, to critical and popular acclaim,

though the NAACP and other groups organized major protests and

violence broke out in Boston and other cities. Booker T. Washington

refused to let Griffith make a film about his Tuskegee Institute

because he did not want to be associated with the makers of a

‘‘hurtful, vicious play.’’ W. E. B. Du Bois adopted a more proactive

stance, urging members of his race to create films and works of art

that would depict its own history in a positive light. But response in

the mainstream press was generally favorable. Critic Mark Vance

boasted in the March 12 issue of Variety how a film ‘‘laid, played, and

made in America’’ marked ‘‘a great epoch in picturemaking’’ that

would have universal appeal. Reviews in the southern papers were

predictably partisan. A critic for the Atlanta Journal, Ward Greene,

obviously inspired by scenes of triumphant Klan riders, crowed that

Griffith’s film ‘‘is the awakener of every feeling . . . Loathing,

disgust, hate envelope you, hot blood cries for vengeance . . . [you

are] mellowed into a deeper and purer understanding of the fires

through which your forefathers battled to make this South of yours a

nation reborn!’’ Over the years, The Birth of a Nation was used as a

propaganda film both by the film’s supporters and detractors. Film

historian John Hope Franklin remarked to a 1994 Library of Congress

panel discussion that the film was used by a resurgent Ku Klux Klan

as a recruiting device from the 1920s onward, a point supported by

other historians, though disputed by Thomas Cripps, author of several

scholarly works on black cinema.

Despite the continuing controversy over the depiction of interra-

cial conflict, The Birth of a Nation remains a landmark film in the

history of world cinema and its director an important pioneer in the

film medium. Writer James Agee, in a rhapsodic defense of Griffith,

wrote of him in a 1971 essay: ‘‘He achieved what no other known man

has ever achieved. To watch his work is like being witness to the

beginning of melody, or the first conscious use of the lever or the

wheel. . . .’’ The Birth of a Nation, continued Agee, was a collection

of ‘‘tremendous magical images’’ that equaled ‘‘Brady’s photo-

graphs, Lincoln’s speeches, and Whitman’s war poems’’ in evoking a

true and dramatic representation of the Civil War era.

—Edward Moran

F

URTHER READING:

Barry, Iris. D.W. Griffith: American Film Master. New York, Muse-

um of Modern Art, 1965.

Gish, Lillian, with Ann Pinchot. The Movies, Mr. Griffith, and Me.

Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1969.

Grimes, William. ‘‘An Effort to Classify a Racist Classic.’’ New York

Times. April 27, 1994.

Phillips, Mike. ‘‘White Lies.’’ Sight & Sound. June 1994.

Silva, Fred, editor. Focus on ‘‘The Birth of a Nation.’’ Englewood

Cliffs, Prentice Hall, 1971.

Sarris, Andrew. ‘‘Birth of a Nation or White Power Back When.’’

Village Voice. July 17 and July 24, 1969.

Stanhope, Selwyn. ‘‘The World’s Master Picture Producer.’’ The

Photoplay Magazine. January 1915, 57-62.

Birthing Practices

Historically speaking, an overview of changing practices of

childbirth offers an overview of the changing dynamics of gender and

the increasing authority of professional medicine, particularly in the

United States and Western Europe. As midwives began to be ‘‘phased

out’’ in the late eighteenth century, they were replaced by male

doctors, and birthing practices changed as a result. Increasing medi-

cal knowledge and experience reinforced this shift, eventually

pathologizing pregnancy and childbirth and tying childbirth to a

hospital environment. In the late twentieth century, however, many

women began calling for a return to the earlier, less medicalized,

models of childbirth, and the debate about the costs and benefits of

various birthing practices continues to develop today.

In colonial America, deliveries were attended by midwives as a

matter of course. These women drew upon years of experience, often

passing their knowledge from one generation to the next, and general-

ly attending hundreds of childbirths during their careers. In some

cases, a midwife might call a ‘‘barber-surgeon’’ to assist with a

particularly difficult case (though often the surgeon’s skills were no

better than the midwife’s, and the patient and child were lost), but for

the most part women (mothers and midwives) controlled the birthing

process. With the rise in medical schools, however, and the teaching

of obstetrics as the first specialty in eighteenth-century Ameri-

can medical schools, medical doctors began to assume control

over childbirth.

Beginning in the 1830s, having a medical doctor in attendance at

a birth became a sign of social prestige—middle- and upper-class

women could afford to call in a doctor and did so more out of a desire

to display their economic and political clout than out of medical

necessity. Class pressures ensured that women would choose child-

birth assistance from someone of their own class (that is, a medical

doctor for the middle and upper classes, a midwife for working

classes). These pressures also meant that crusades to persuade mid-

dle- and upper-class women that they ‘‘deserved’’ physicians, that no

precaution was too great, and so on, were enormously effective in

shifting public opinion toward the presumed superiority of medical

doctors. As this kind of social pressure continued to spread through-

out the Victorian era, lay practitioners lost more and more status, and

medical doctors gained more and more control. Furthermore, the

systematic exclusion of women from the medical profession, particu-

larly during the nineteenth century, ensured that women themselves

began losing control of childbirth, giving it up to the increasing

authority of the male medical community.

Throughout the 1800s, doctors employed medical privilege to

protect their professional status from the economic and social threat

BIRTHING PRACTICESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

261

of midwives who lacked formal training. The Boston Women’s

Health Collective asserts that nineteenth-century physicians ‘‘waged

a virulent campaign against midwives, stereotyping them as ignorant,

dirty, and irresponsible. Physicians deliberately lied about midwifery

outcomes to convince legislators that states should outlaw it.’’ These

strategies, coupled with the significant risks of childbirth (infant and

maternal mortality rates remained high throughout the nineteenth

century), helped to create a climate of fear surrounding pregnancy and

birth. Rather than seeing childbirth as a natural practice, people began

to see it as a medical emergency, one that should be relinquished to a

physician’s control.

Once childbirth had been pathologized, the door was opened to

begin moving women in labor out of their homes and into hospitals

where, according to the medical community, the ‘‘disease of child-

birth’’ could best be battled. Until the beginning of the twentieth

century, it was actually a stigma to have to give birth in a maternity

ward, which had generally been reserved for the poor, immigrants,

and unmarried girls. As better strategies were developed to prevent

disease (especially deadly outbreaks of puerperal fever that had

flourished in hospitals throughout the nineteenth century), the hospi-

tal birth, with its concomitant costs, was recast as a status symbol.

Eventually, however, having babies in hospitals became a matter of

course. According to Jessica Mitford, while only 5 percent of babies

were born in hospitals in 1900, 75 percent were born in hospitals in

1935, and by the late 1960s, 95 percent of babies were born in

hospitals. Eakins’ American Way of Birth notes, ‘‘the relocation of

obstetric care to the hospital provided the degree of control over both

reproduction and women that would-be obstetricians needed in their

ascent to professionalized power.’’ This power was consolidated

through non-medical channels, with advice columns, media attention,

popular books, and community pressure working to reinforce the

primacy of the professional medical community in managing wom-

en’s childbirth experiences.

In the twentieth century, giving birth in a hospital environment

has meant a loss of control for the mother as she becomes subject to

numerous, standardized medical protocols; throughout her pregnan-

cy, in fact, she will have been measured against statistics and fit into

frameworks (low-risk vs. high-risk pregnancy; normal vs. abnormal

pregnancy, and so on). As a result, the modern childbirth experience

seems to depersonalize the mother, fitting her instead into a set of

patient ‘‘guidelines.’’ Women in labor enter alongside the ill, the

injured, and the dying. Throughout most of the twentieth century,

women were anesthetized as well, essentially being absent from their

own birthing experience; fathers were forced to be absent as well,

waiting for the announcement of his child’s arrival in a hospital

waiting room. If a woman’s labor is judged to be progressing ‘‘too

slowly’’ (a decision the doctor, rather than the mother, usually

makes), she will find herself under the influence of artificial practices

designed to speed up the process. More often than not, her pubic area

will be shaved (a procedure that is essentially pointless) and some-

times cut (in an episiotomy) by medical personnel anxious to control

the labor process. Further advances in medical technology, including

usage of various technological devices and the rise in caesarian

sections (Mitford cites rates as high as 30 percent in some hospitals),

have also contributed to a climate of medicalization and fear for many

women giving birth. This is not to say, of course, that many of these

medical changes, including improved anesthetics (such as epidurals)

and improved strategies for difficult birthing situations (breech births,

fetal distress, etc.) have not been significant advances for women and

their babies. But others argue that many of these changes have been

for the doctors’ convenience: delivering a baby while lying on one’s

back with one’s feet in stirrups is surely designed for the obstetri-

cian’s convenience, and the rise in caesarian sections has often been

linked to doctors’ preferences rather than the mothers’.

In the 1960s and 1970s, as a result of their dissatisfaction with

the medical establishment and with the rising cost of medical care,

various groups began encouraging a return to older attitudes toward

childbirth, a renewal of approaches that treat birthing as a natural

process requiring minimal (if any) medical intervention. One of the

first steps toward shifting the birthing experience away from the

control of the medical establishment involved the introduction of

childbirth classes for expectant parents. These courses often stress

strategies for dealing with the medical community, for taking control

of the birthing process, and for maintaining a ‘‘natural childbirth’’

experience through education; the most famous methods of natural

childbirth are based on work by Grantly Dick-Read (Childbirth

Without Fear), Fernand Lamaze, and Robert Bradley.

Also significant were various feminist critiques of the standard

birth practices. The publication of the Boston Women’s Health

Collective’s Our Bodies, Ourselves in 1984 offered a resource to

women who wanted to investigate what had been essentially ‘‘under-

ground’’ alternatives to the medicalized childbirth experience. Through

this work (and others), women learned how to question their doctors

more assertively about the doctors’ practices, to file ‘‘birth plans’’

(which set out the mother’s wishes for the birth), and to find networks

of like-minded parents, midwives, and doctors who can assist in

homebirths, underwater births, and other childbirth techniques. In

some states, midwives not attached to hospitals are still outlaws, and

groups continue to campaign to change that fact.

Finally, many hospitals are recognizing women’s desire to move

away from the dehumanizing and pathological approaches to child-

birth associated with the professional medical community. In defer-

ence to these desires (or, more cynically, in deference to their

financial bottom lines), some hospitals have built ‘‘Birthing Cen-

ters,’’ semi-detached facilities dedicated specifically to treating child-

birth as a natural process. Women enter the Birthing Center, rather

than the hospital. There they are encouraged to remain mobile, to have

family and friends in attendance, and to maintain some measure of

control over their bodies. Often patient rooms are designed to look

‘‘homey,’’ and women (without complications) give birth in their

own room, rather than in an operating theater. Many of these facilities

employ Nurse Midwives, women and men who have been trained as

nurses in the traditional medical establishment but who are dedicated

to demedicalizing the childbirth practice while still offering the

security of a hospital environment.

As women and men continue to demand that childbirth be

recognized as a natural, rather than unnatural, process, the dominant

birthing practices will continue to shift. Additionally, rising pressures

from the insurance industry to decrease costs are also likely to

contribute to a decrease in the medical surveillance of childbirth—

already new mothers’ hospital stays have been drastically reduced in

length as a cost-cutting measure. Clearly the move in recent years has

meant a gradual return to earlier models of childbirth with a return of

control to the mother and child at the center of the process.

—Deborah M. Mix

F

URTHER READING:

Boston Women’s Health Collective. The New Our Bodies, Ourselves,

Updated for the 90s. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1992.

BLACK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

262

Eakins, Pamela S., editor. The American Way of Birth. Philadelphia,

Temple University Press, 1986.

Mitford, Jessica. The American Way of Birth. New York, Dutton, 1992.

Black, Clint (1962—)

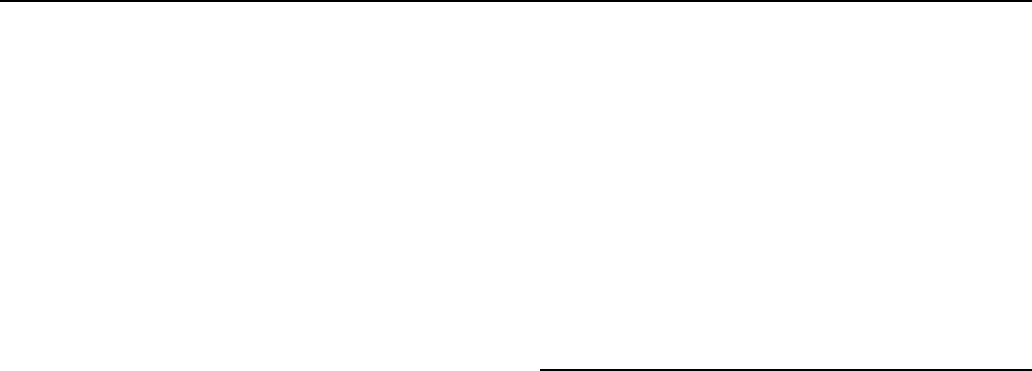

Since the release of his first album in 1989, Clint Black has

become one of country music’s biggest stars. He is also one of the

most prominent symbols of country’s revival in the 1980s and 1990s.

It was in the mid-1980s that country music had been written off as

dead. In 1985, The New York Times reported that this once mighty

genre had fallen off the edge of the American entertainment table and

it would never regain such stature with its audience. A year later, the

same newspaper reversed itself in an article hailing the new creative

and commercial vitality of country music, as traditionalists like

Randy Travis and young iconoclasts like Steve Earle brought new life

into old forms. That, however, was nothing compared to what was just

around the corner. Country was about to be taken over by a new

Clint Black

generation of heartthrobs in cowboy hats who were going to capture

the imagination of the American public to a degree hitherto unimagined.

Part of country music’s revival was due to the creative ground-

work that was laid for newcomers in the adventurous creativity of the

mid-1980s. Angry song-writing geniuses like Earle, quirky originals

like Lyle Lovett, and musical innovators like the O’Kanes all played a

part in paving the way for young new artists. Interestingly, the

aggressive urban anger of black music in the 1980s also influenced

the country scene. Rap drove a lot of middle class whites to a music

they could understand, and country radio was playing it. The audience

for pop music was also growing older and, in the 1980s, for the first

time, a generation over thirty-five continued to buy pop music.

Although the children of these suburban middle-class consumers

were buying rap, their parents were looking for the singer-songwriters

of their youth—the new Dan Fogelbergs and James Taylors—and

they found them wearing cowboy hats.

The country superheroes of the 1980s and 1990s were a new

breed indeed. They did not have the down-home background of Lefty

Frizzell, Porter Wagoner, or Johnny Cash, but they did have their own

skills that would help them succeed in the music industry. Garth

Brooks was a marketing major in college, and he knew how to market

himself; Dwight Yoakam was a theater major, and he knew how to

invent himself onstage; and Lyle Lovett’s day job at the time he

signed his first recording contract was helping his mother run high-

level business management training seminars.

Clint Black, who arrived on the scene in 1989, was a ‘‘folkie’’

from the suburbs of Houston. His father advised him against going

into country music precisely because he did not think he was country

enough. ‘‘Stick to doing other folks’ songs,’’ he advised. ‘‘Real

country songwriters, like Harlan Howard. Don’t try to write your

own. You haven’t done enough living—shooting pool, drinking beer,

getting into fights—to write a real country song.’’ Black’s ‘‘Noth-

ing’s News,’’ which graced his first album, was an answer to his

father and to all those other good old boys who ‘‘Spent a lifetime . . .

Down at Ernie’s icehouse liftin’ longnecks to that good old country

sound,’’ only to discover ultimately that they had ‘‘worn out the same

old lines, and now it seems that nothin’s news ....’’

The 1980s were a time when the rock influence hit country with a

vengeance. Rock acts like Exile and Sawyer Brown became country

acts. Country radio adopted the tight playlists of pop radio. Record

company executives from Los Angeles and New York started moving

into the little frame houses that served as office buildings on Nash-

ville’s Music Row. And even among the neo-traditional acts, rock

music management techniques became the norm. Clint Black’s career

blossomed under the managerial guidance of Bill Ham, who had

made his reputation guiding ZZ Top’s fortunes. Black’s first album,

Killin’ Time, became the first debut album ever, in any genre, to place

five singles at number one on the charts.

For many country artists, country superstardom seems to almost

automatically raise the question, ‘‘Now what?’’ For Black, marriage

was the answer to that question. He married Hollywood television star

Lisa Hartman (Knots Landing) in 1991 and their marriage has lasted.

It has also garnered him a certain amount of gossip column celebrity

beyond the country circuit. Although Black also has a movie role in

Maverick to his credit, his reputation rests solidly on what he does

best: writing and singing country songs. Black seems to have settled

in for the long haul.

—Tad Richards

BLACK MASKENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

263

FURTHER READING:

Brown, C. D. Clint Black: A Better Man. New York, Simon &

Schuster, 1993.

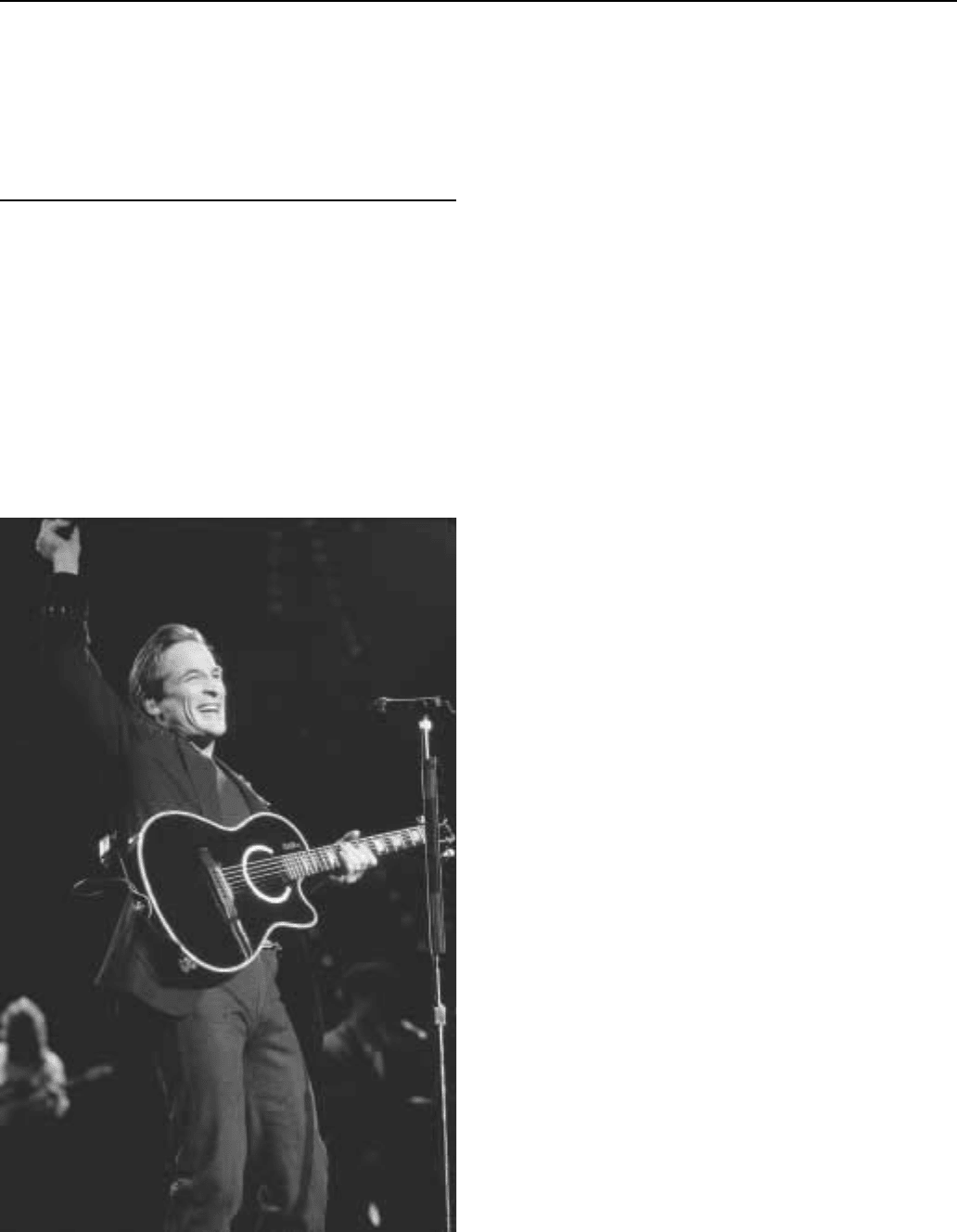

Black Mask

One of the most important detective fiction magazines of the

twentieth century, Black Mask began early in 1920 and introduced

and developed the concept of the tough private eye. It also promoted,

and in some cases introduced, the work of such writers as Dashiell

Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Erle Stanley Gardner, and John D.

MacDonald. Hammett’s The Dain Curse, Red Harvest, The Glass

Key, and The Maltese Falcon all appeared originally as serials in the

magazine and Chandler sold his first detective story to Black Mask. In

its over 300 issues the pulp showcased the work of dozens of other

writers. Though many are forgotten today, such contributors as

Frederick Nebel, Norbert Davis, W.T. Ballard, John K. Butler, Raoul

Whitfield, Carroll John Daly, Horace McCoy, Lester Dent, and

William Campbell Gault all helped shape and define the hardboiled

school of mystery writing.

Early in 1919, H. L. Mencken, literary man and dedicated

iconoclast, wrote a letter to a friend. ‘‘I am thinking of venturing into a

new cheap magazine,’’ he explained. ‘‘The opportunity is good and I

need the money.’’ Mencken and his partner, theater critic George Jean

Nathan, required funds to keep their magazine The Smart Set afloat.

He considered that a quality publication, but in his view the new one

that he and Nathan launched early in 1920 was ‘‘a lousy magazine’’

that would cause them nothing but ‘‘disagreeable work.’’ Their new

publication was christened The Black Mask and featured mystery

stories. Pretty much in the vein of Street & Smith’s pioneering

Detective Story pulp, the early issues offered very sedate, and often

British, detective yarns. Nathan and Mencken soon sold out, leaving

the magazine in other hands.

Then in 1923 two beginning writers started submitting stories

about a new kind of detective. Carroll John Daly, a onetime motion

picture projectionist and theater manager from New Jersey, intro-

duced a series about a tough, gun-toting private investigator named

Race Williams. Written in a clumsy, slangy first person, they recount-

ed Williams’ adventures in a nightmare urban world full of gangsters,

crooked cops, and dames you could not trust. Williams explained

himself and his mission this way—‘‘The papers are either roasting me

for shooting down some minor criminals or praising me for gunning

out the big shots. But when you’re hunting the top guy, you have to

kick aside—or shoot aside—the gunmen he hires. You can’t make

hamburger without grinding up a little meat.’’ This tough, humorless

metropolitan cowboy became extremely popular with the magazine’s

readers, who were obviously tired of the cozy crime stories that the

early Black Mask had depended on. For all his flaws, Race Williams is

acknowledged by most critics and historians to be the first hardboiled

detective, and the prototype for others to follow.

Unlike Daly, Dashiell Hammett knew what he was talking

about. He had been a private investigator himself, having put in

several years with the Pinkerton Agency. Exactly four months after

the advent of Race Williams, Hammett sold his first story about the

‘‘Continental Op(erative)’’ to the magazine. Titled ‘‘Arson Plus,’’ it

introduced the plump middle-aged operative who worked out of the

San Francisco office of the Continental Detective Agency. Although

also in the first person, the Op stories were written in a terse and

Various covers of Black Mask.

believable vernacular style that made them sound real. Hammett’s

private detective never had to brag about being tough and good with a

gun; readers could see that he was. His nameless operative soon

became Race Williams’ chief rival and after he had written nearly two

dozen stories and novellas about him, Hammett put him into a novel.

The first installment of Red Harvest appeared in the November 1927

issue of Black Mask. In November of the next year came the second

Op serial, The Dain Curse. Then in 1929 Hammett introduced a new

San Francisco private eye, a pragmatic tough guy he described as

resembling a blond Satan. The Maltese Falcon, told in the third

person, introduced Sam Spade and the quest for the jewel-encrusted

bird. The story quickly moved into hardcovers, movies, and interna-

tional renown. Hammett’s The Glass Key ran in the magazine in 1930

and his final Op story in the November issue of that year. With the

exception of The Thin Man, written initially for Redbook in the early

1930s, everything that Hammett is remembered for was published in

Black Mask over a period of less than ten years.

Joseph Shaw was usually called Cap Shaw, because of his Army

rank during World War I. Not at all familiar with pulp fiction or Black

Mask when he took over as editor in 1926, he soon educated himself

on the field. Shaw never much liked Daly’s work, but kept him in the

magazine because of his appeal to readers. Hammett, however, was

an exceptional writer and Shaw used him to build the magazine into

an important and influential one. ‘‘Hammett was the leader in the

thought that finally brought the magazine its distinctive form,’’ Shaw

explained some years later. ‘‘Without that it was and would still have

been just another magazine. Hammett began to set character before

situation, and led some others along that path.’’ In addition to

BLACK PANTHERS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

264

concentrating on character, one of the goals of the best Black Mask

authors was to develop prose that sounded the way people talked and

not the way writers wrote. In addition to Hammett, Cap Shaw

encouraged other writers who had already been contributors when he

joined as editor. Among them were Erle Stanley Gardner, Raoul

Whitfield, and Frederick Nebel. He asked Nebel to create a new

hardboiled private eye and the result was, as a blurb called him, ‘‘an

iron-nerved private dick’’ named Donahue. One of the things he got

from Whitfield was a serial titled ‘‘Death in a Bowl,’’ which

introduced Ben Jardinn, the very first Hollywood private eye. In

1933, Shaw bought ‘‘Blackmailers Don’t Shoot’’ from Raymond

Chandler, a failed middle-aged business man who was hoping he

could add to his income by writing pulpwood fiction. The tough and

articulate private eye Chandler wrote about for Black Mask, and later

for its rival Dime Detective, was called Mallory and then John

Dalmas. When he finally showed up in the novel The Big Sleep in

1939, he had changed his name to Philip Marlowe. Among the many

other writers Shaw introduced to Black Mask were Horace McCoy,

Paul Cain, Lester Dent, and George Harmon Coxe.

After Shaw quit the magazine in 1936 over a salary dispute, it

changed somewhat. Chandler moved over to Dime Detective, where

Nebel had already been lured, and the stories were not quite as

‘‘hardboiled’’ anymore. New writers were recruited by a succession

of editors. Max Brand, Steve Fisher, Cornell Woolrich, and Frank

Gruber became cover names in the later 1930s. Black Mask was

bought out by Popular Publications in 1940 and started looking

exactly like Popular’s Dime Detective. Kenneth S. White became the

editor of both and put even more emphasis on series characters.

Oldtime contributors such as H.H. Stinson and Norbert Davis provide

recurring detectives, as did newcomers like Merle Constiner, D.L.

Champion, and Robert Reeves. Later on John D. MacDonald, Richard

Demming, and William Campbell Gault made frequent appearances.

The decade of the 1950s saw the decline and fall of all the pulp

fiction magazines. Black Mask ceased to be after its July 1951 issue.

By then, it was a smaller-sized magazine that included reprints from

earlier years with few new detective tales. Attempts to revive it in the

1970s and the 1980s were unsuccessful.

—Ron Goulart

F

URTHER READING:

Cook, Michael L., editor. Mystery, Detective, and Espionage Maga-

zines. Westport, Greenwood Press, 1983.

Goulart, Ron. The Dime Detective. New York, Mysterious Press, 1988.

Sampson, Robert. Yesterday’s Faces. Bowling Green, Ohio, Bowling

Green State University Popular Press, 1987.

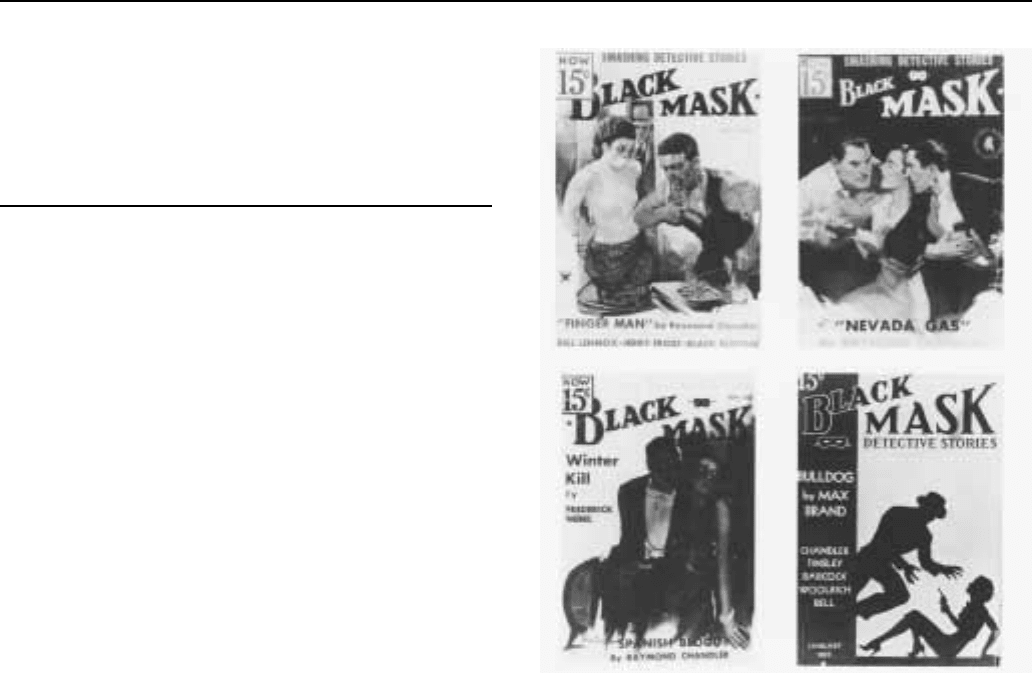

Black Panthers

The Black Panther Party (BPP) came to represent the West Coast

manifestation of Black Power as well as the angry mood within urban

African American communities in the 1960s. The groups main

influences were Malcolm X, especially after his 1964 break from the

Nation of Islam, and Robert F. Williams, the then Cuban-based civil

rights leader and advocate of armed self-defense. Philosophically, the

Black Panthers (from left): 2nd Lt. James Pelser, Capt. Jerry James, 1st

Lt. Greg Criner and 1st Lt. Robert Reynolds.

organization was rooted in an eclectic blend of Marxist-Leninism,

black nationalism, and in the revolutionary movements of Africa

and Asia.

The BPP was founded in October 1966 by Huey Newton and

Bobby Seale, two young black college students in Oakland, Califor-

nia. The name of the organization was taken from the Lowndes

County Freedom Organization, which had used the symbol and name

for organizing in the rural black belt of Alabama in 1965. The BPP

was initially created to expand Newton and Seale’s political activity,

particularly ‘‘patrolling the pigs’’—that is, monitoring police activi-

ties in black communities to ensure that civil rights were respected.

Tactically, the BPP advocated ‘‘picking up the gun’’ as a means

to achieve liberation for African Americans. Early on, Newton and

Seale earned money to purchase guns by selling copies of Mao Tse-

tung’s ‘‘Little Red Book’’ to white radicals on the University of

California-Berkeley campus. The group’s ‘‘Ten Point Program’’

demanded self-determination for black communities, full employ-

ment, decent housing, better education, and an end to police brutality.

In addition, the program included more radical goals: exemption from

military service for black men, all-black juries for African Americans

on trial and ‘‘an end to the robbery by the capitalists of our Black

Community.’’ Newton, the intellectual leader of the group, was

appointed its first Minister of Defense and Eldridge Cleaver, a prison

activist and writer for the New Left journal Ramparts, became

Minister of Information. Sporting paramilitary uniforms of black

leather jackets, black berets, dark sunglasses, and conspicuously

displayed firearms, the Panthers quickly won local celebrity.

BLACK SABBATHENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

265

A series of dramatic events earned the Black Panthers national

notoriety in 1967. That spring, as a result of the Panthers’ initial police

surveillance efforts, members of the California state legislature

introduced a bill banning the carrying of loaded guns in public. In

response, a group of Black Panthers marched into the capitol building

in Sacramento toting loaded weapons. Then, on October 28 of the

same year, Newton was arrested on murder charges following an

altercation with Oakland police which left one officer dead and

Newton and another patrolman wounded. The arrest prompted the

BPP to start a ‘‘Free Huey!’’ campaign which attracted national

attention through the support of Hollywood celebrities and noted

writers and spurred the formation of Black Panther chapters in major

cities across the nation. In addition, Newton’s arrest forced Seale and

Cleaver into greater leadership roles in the organization. Cleaver, in

particular, with his inflammatory rhetoric and powerful speaking

skills, increasingly shaped public perceptions of the Panthers with

incendiary calls for black retribution and scathing verbal attacks

against African American ‘‘counter-revolutionaries.’’ He claimed the

choice before the United States was ‘‘total liberty for black people or

total destruction for America.’’

In February 1968, former Student Non-Violent Coordinating

Committee (SNCC) leader, Stokely Carmichael, who had been invit-

ed by Cleaver and Seale to speak at ‘‘Free Huey!’’ rallies, challenged

Cleaver as the primary spokesman for the party. Carmichael’s Pan-

Africanism, emphasizing racial unity, contrasted sharply with other

Panther leaders’ emphasis on class struggle and their desire to attract

white leftist support in the campaign to free Newton. The ideological

tension underlying this conflict resulted in Carmichael’s resignation

as Prime Minister of the BPP in the summer of 1969 and signaled the

beginning of a period of vicious infighting within the black militant

community. In one incident, after the Panthers branded head of the

Los Angeles-based black nationalist group US, Ron Karenga, a ‘‘pork

chop nationalist,’’ an escalating series of disputes between the groups

culminated in the death of two Panthers during a shoot-out on the

UCLA campus in January 1969.

At the same time, the federal government stepped up its efforts to

infiltrate and undermine the BPP. In August 1967, the FBI targeted

the Panthers and other radical groups in a covert counter-intelligence

program, COINTELPRO, designed to prevent ‘‘a coalition of militant

black nationalist groups’’ and the emergence of a ‘‘black messiah’’

who might ‘‘unify and electrify these violence-prone elements.’’ FBI

misinformation, infiltration by informers, wiretapping, harassment,

and numerous police assaults contributed to the growing tendency

among BPP leaders to suspect the motives of black militants who

disagreed with the party’s program. On April 6, 1968, police descend-

ed on a house containing several Panthers, killing the party’s 17-year-

old treasurer, Bobby Hutton, and wounding Cleaver, who was then

returned to prison for a parole violation. In September, authorities

convicted Newton of voluntary manslaughter. In December, two

Chicago party leaders, Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, were killed in

a police raid. By the end of the decade, 27 members of the BPP had

been killed, Newton was in jail (although he was released after a

successful appeal in 1970), Cleaver had fled to Algeria to avoid

prison, and many other Panthers faced lengthy prison terms or

continued repression. In 1970, the state of Connecticut unsuccessfully

tried to convict Seale of murder in the death of another Panther in

that state.

By the early 1970s, the BPP was severely weakened by external

attack, internal division, and legal problems and declined rapidly.

After his release from prison in 1970, Newton attempted to wrest

control of the party away from Cleaver and to revive the organiza-

tion’s popular base. In place of Cleaver’s fiery rhetoric and support

for immediate armed struggle, Newton stressed community organiz-

ing, set up free-breakfast programs for children and, ultimately,

supported participation in electoral politics. These efforts, though,

were undermined by widely published reports that the Panthers

engaged in extortion and assault against other African Americans. By

the mid-1970s, most veteran leaders, including Seale and Cleaver,

had deserted the party and Newton, faced with a variety of criminal

charges, fled to Cuba. After his return from exile, Newton earned a

doctorate, but was also involved with the drug trade. In 1989, he was

shot to death in a drug-related incident in Oakland. Eldridge Cleaver

drifted rightward in the 1980s, supporting conservative political

candidates in several races. He died on May 1, 1998, as a result of

injuries he received in a mysterious mugging. Bobby Seale continued

to do local organizing in California. In 1995, Mario Van Pebbles

directed the feature film, Panther, which attempted to bring the story

of the BPP to another generation. The Panthers are remembered today

as much for their cultural style and racial posturing as for their

political program or ideology.

—Patrick D. Jones

F

URTHER READING:

Brown, Elaine. A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story. New York,

Pantheon, 1992.

Chruchill, Ward. Agents of Repression: The FBI’s Secret Wars

Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Move-

ment. Boston, South End, 1988.

Cleaver, Eldridge. Soul On Ice. New York, Laurel/Dell, 1992.

Hilliard, David. This Side of Glory: The Autobiography of David

Hilliard and the Story of the Black Panther Party. Boston, Little

Brown, 1993.

Keating, Edward. Free Huey! Berkeley, California, Ramparts, 1970.

Moore, Gilbert. Rage. New York, Carroll & Graf, 1971.

Newton, Huey. To Die for the People: The Writings of Huey P.

Newton. New York, Random House, 1972.

Pearson, Hugh. The Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the

Price of Black Power In America. Reading, Massachusetts, Addi-

son-Wesley, 1994.

Seale, Bobby. Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party

and Huey P. Newton. New York, Random House, 1970.

Black Sabbath

Formed in Birmingham, England in 1968, Black Sabbath was

one of the most important influences on hard rock and grunge music.

While the term ‘‘heavy metal’’ was taken from a Steppenwolf lyric

and had already been applied to bands such as Cream and Led

Zeppelin, in many ways Black Sabbath invented the genre. They were

perhaps the first band to include occult references in their music, and

they began to distance themselves from the blues-based music which

was the norm, although they had started their career as a blues band.

Originally calling themselves Earth, they discovered another

band with the same name. After renaming themselves Black Sabbath

BLACK SOX SCANDAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

266

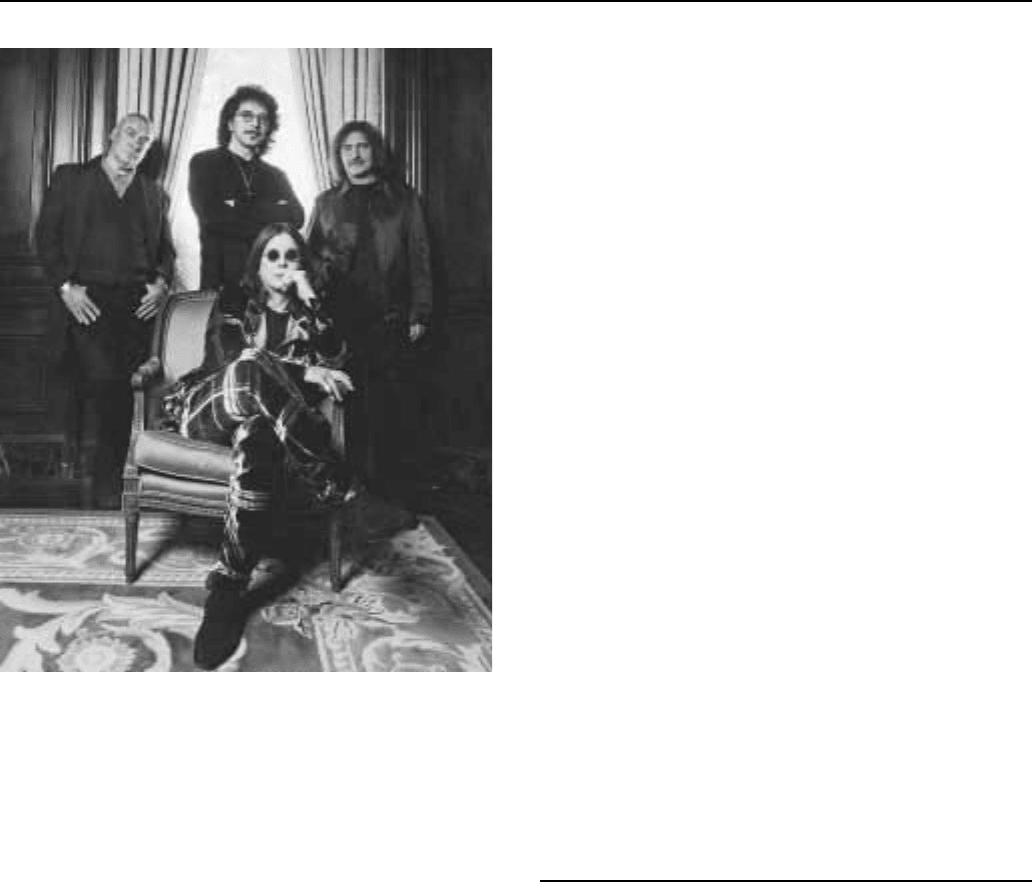

Black Sabbath in 1998: Ozzy Osbourne (seated), (standing from left) Bill

Ward, Tony Iommi, and Geezer Butler.

the group released their self-titled first album in 1970. Black Sabbath

was recorded both quickly and inexpensively—it took only two days

and cost six hundred pounds. In spite of that, the album reached

number 23 on the American charts and would eventually sell over a

million copies. Paranoid was released later the same year and cracked

the top ten in the United States while topping the charts in Britain.

Their third album, Master of Reality, was equally successful and

remained on the Billboard charts in America for almost a year.

Those releases introduced themes which would become staples

for future metal bands: madness, death, and the supernatural. Al-

though some considered the band’s lyrics satanic, there was often an

element of camp present. The group got its name from the title of a

Boris Karloff film, and songs such as ‘‘Fairies Wear Boots’’ are at

least partly tongue-in-cheek. But vocalist John ‘‘Ozzy’’ Osbourne’s

haunting falsetto and Tony Iommi’s simultaneously spare and thun-

dering guitar work would become touchstones for scores of hard

rock bands.

Sabbath released three more albums as well as a greatest hits

collection before Osbourne left the group in 1977, reportedly because

of drug and alcohol problems. He returned in 1978, then left perma-

nently the following year to start his own solo career. Initially, both

Osbourne and the new version of Black Sabbath enjoyed some degree

of commercial success, although many of the Sabbath faithful insisted

the whole greatly exceeded the sum of its parts. During the 1980s the

band would go through an astonishing array of lineup changes and

their popularity plummeted.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Soundgarden, Helmet, Nirva-

na, and others in the grunge and resurgent hard rock movements

demonstrated that they had been heavily influenced by the early Black

Sabbath, and this effectively rehabilitated the band’s reputation.

While Sabbath had often been viewed as a dated version of the arena

rock of the 1970s, grunge indicated not only that their music remained

vibrant, but also that it bore many surprising similarities to the Sex

Pistols, Stooges, and other punk and proto-punk bands. Sabbath

became heroes to a new generation of independent and alternative

bands, and the group’s first albums enjoyed an enormous resurgence

in popularity. Their music returned to many radio stations and was

even featured in television commercials. Osbourne organized Ozzfest,

an annual and very successful tour which featured many of the most

prominent heavy metal and hard rock acts, as well as his own band.

Iommi continued to record and tour with Black Sabbath into the late

1990s, although he was the only original member, and listeners and

audiences remained largely unimpressed.

—Bill Freind

F

URTHER READING:

Bashe, Philip. Heavy Metal Thunder: The Music, Its History, Its

Heroes. Garden City, New York, Doubleday, 1985.

Walser, Robert. Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Mad-

ness in Heavy Metal Music. Hanover, New Hampshire, University

Press of New England, 1993.

Black, Shirley Temple

See Temple, Shirley

Black Sox Scandal

Although gambling scandals have been a part of professional

baseball since the sport’s beginning, no scandal threatened the game’s

stature as ‘‘the national pastime’’ more than the revelations that eight

members of the Chicago White Sox had conspired to throw the 1919

World Series. Termed the ‘‘Black Sox Scandal,’’ the event will go

down in history as one of the twentieth century’s most notorious

sports debacles.

The Chicago White Sox of the World War I period were one of

the most popular teams in the major leagues. They were led on the

field by ‘‘Shoeless’’ Joe Jackson, an illiterate South Carolinian whose

.356 career batting average is the third highest ever, and pitchers

Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams. The Sox were owned by Charles

A. Comiskey, a nineteenth-century ballplayer notorious for paying

his star players as little as possible; Cicotte, who led the American

League with 29 wins in 1919, earned just $5,500 that season.

Comiskey’s stinginess included not paying for the team’s laundry in

1918—the team continued to play in their dirty uniforms, which is

when the sobriquet ‘‘Black Sox’’ originated.

During the 1919 season, the White Sox dominated the American

League standings. Several players on the team demanded that Comiskey

BLACK SOX SCANDALENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

267

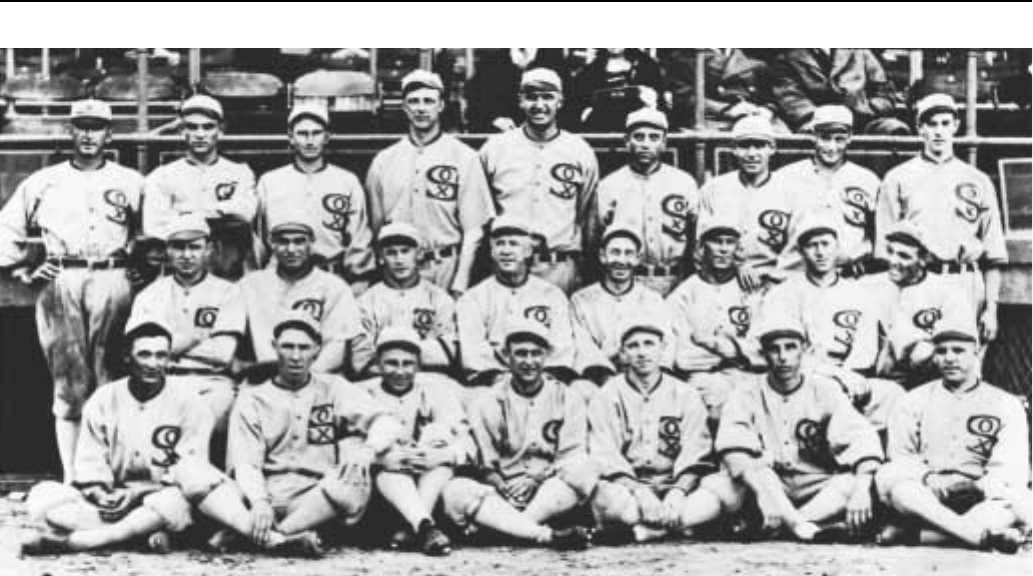

The 1919 Chicago White Sox.

give them raises. He refused. First baseman Chick Gandil began

discussing throwing the World Series with his fellow players. The

eight Sox players who attended meetings on throwing the Series were

Cicotte, Gandil, Williams, Jackson, shortstop Swede Risberg, third

basemen Fred McMullin and Buck Weaver, and outfielder Happy

Felsch. In mid-September, Gandil met with small-time Boston gam-

bler ‘‘Sport’’ Sullivan in New York, telling him his teammates were

interested in throwing the upcoming World Series if Sullivan could

deliver them $80,000. Two more gamblers, ex-major league pitcher

Bill Burns and former boxer Billy Maharg, agreed to contribute

money. These three gamblers contacted New York kingpin Arnold

Rothstein, who agreed to put up the full $80,000.

Cicotte pitched the Series opener against the Reds. As a sign to

the gamblers that the fix was on, he hit the first batter with a pitch.

Almost instantly, the gambling odds across the country shifted from

the White Sox to the Reds. The Sox fumbled their way to a 9-1 loss in

Game One.

Throughout the Series, the White Sox made glaring mistakes on

the field—fielders threw to the wrong cutoff men, baserunners were

thrown out trying to get an extra base, reliable bunters could not make

sacrifices, and control pitchers such as Williams began walking

batters. Most contemporary sportswriters were convinced something

was corrupt. Chicago sportswriter Hugh Fullerton marked dubious

plays on his scorecard and later discussed them with Hall of Fame

pitcher Christy Mathewson.

The 1919 Series was a best-of-nine affair, and the underdog

Reds led four games to one after five games. When the gamblers’

money had not yet arrived, the frustrated Sox began playing to win,

beating Cincinnati in the sixth and seventh games. Before Williams

started in the eighth game, gamblers approached him and warned him

his wife would be harmed if he made it through the first inning.

Williams was knocked out of the box after allowing three runs in the

first inning. The Cincinnati Reds won the Series with a command-

ing 10-5 win.

After the Series, Gandil, who had pocketed $35,000 of the

$80,000, retired to California. Fullerton wrote columns during the

following year, insisting that gamblers had reached the White Sox; he

was roundly criticized by the baseball establishment and branded

a malcontent.

The fixing of the 1919 Series became public in September 1920,

when Billy Maharg announced that several of the World Series games

had been thrown. Eddie Cicotte broke down and confessed his

involvement in the fixing; he claimed he took part in taking money

‘‘for the wife and kiddies.’’ Joe Jackson, who during the Series batted

a robust .375, signed a confession acknowledging wrongdoing. Upon

leaving the courthouse, legend has it that a tearful boy looked up to

him and pleaded, ‘‘Say it ain’t so, Joe.’’ ‘‘I’m afraid it is,’’ Jackson

allegedly replied.

On September 28, 1920 a Chicago grand jury indicted the eight

players. They were arraigned in early 1921. That summer they were

tried on charges of defrauding the public. The accused were repre-

sented by a team of expensive lawyers paid for by Comiskey. At the

trial it was revealed that the signed confessions of Jackson, Cicotte,

and Williams had been stolen. The defense lawyers maintained that

there were no laws on the books against fixing sporting events.

Following a brief deliberation, the eight were found not guilty on

August 2, 1921. The impact of the allegation, however, was undeni-

able. Kennesaw Mountain Landis, a former Federal judge elected as

organized baseball’s first commissioner in November 1920, declared,

‘‘No player who throws a ball game, no player who undertakes or

promises to throw a ball game, no player who sits in a conference with

a bunch of crooked players and gamblers, where the ways and means

BLACKBOARD JUNGLE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

268

of throwing a ball game are planned and discussed and does not

promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball.’’

The eight Black Sox players spent the rest of their lives in exile.

Jackson played semi-pro baseball under assumed names. Several

appealed to be reinstated, but Landis and his successors invariably

rejected them. Perhaps the saddest story of all was Buck Weaver’s.

While he had attended meetings to fix the Series, he had never

accepted money from the gamblers and had never been accused of

fixing games by the prosecution (in fact, Weaver batted .324 during

the Series). But for not having told Comiskey or baseball officials

about the fix, he was tried with his seven teammates and thrown out of

baseball with them. The last surviving member of the Black Sox,

Swede Risberg, died in October 1975.

Most historians credit baseball’s subsequent survival to two

figures. From on high, Landis ruled major league baseball with an

iron fist until his death in 1944 and gambling scandals decreased

substantially throughout organized baseball. On the field of play,

Babe Ruth’s mythic personality and home run hitting ability brought

back fans disillusioned by the 1919 scandal, while winning the game

millions of new fans.

—Andrew Milner

F

URTHER READING:

Asinof, Eliot. Eight Men Out. New York, Holt, 1963.

Light, Jonathan Frase. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball. Jeffer-

son, North Carolina, McFarland, 1997.

Wallop, Douglass. Baseball: An Informal History. New York, W.W.

Norton, 1969.

The Blackboard Jungle

Ten years after the end of World War II, writer-director Richard

Brooks’ film, The Blackboard Jungle (1955) was released. The film

remains as a moody, entertaining potboiler and an early formula for

treating a theme—the rehabilitating education of delinquents and the

inner-city underprivileged—that was still being explored in the

cinema of the 1980s and 1990s. Films as diverse as the serious and

specific Stand and Deliver (1988, Edward James Olmos played the

beleaguered teacher), the comedic Renaissance Man (1994, Danny de

Vito), and the sentimental Dangerous Minds (1995, Michelle Pfeiffer),

can all find their origins in The Blackboard Jungle, which, although

not a particularly masterful film, was unique in its time, and became a

cultural marker in a number of respects. It is popularly remembered as

the first movie ever to feature a rock ’n’ roll song (Bill Haley and the

Comets, ‘‘Rock around the Clock’’), and critically respected for its

then frank treatment of juvenile delinquency and a powerful perform-

ance by actor Glenn Ford. It is notable, too, for establishing the hero

image of African American Sidney Poitier, making him Hollywood’s

first black box-office star, and for its polyglot cast that accurately

reflected the social nature of inner-city ghetto communities.

The Blackboard Jungle, however, accrues greater significance

when set against the cultural climate that produced it. Despite the post

war position of the United States as the world’s leading superpower,

the country still believed itself under the threat of hostile forces.

Public debate was couched exclusively in adversarial terms; under the

constant onslaught, the nation succumbed to the general paranoia that

detected menace in all things from music to motorcyclists, from

people of color and the poor to intellectuals and poets. Even the young

were a menace, a pernicious presence to be controlled, and protected

from the rock ’n’ roll music they listened and danced to, which was

rumored as part of a Communist plot designed to corrupt their morals.

From the mid-1940s on, a stream of novels, articles, sociological

studies and, finally, movies, sought to explain, sensationalize, vilify,

or idealize juvenile delinquency. It was precisely for the dual purpose

of informing and sensationalizing that The Blackboard Jungle was

made, but, like Marlon Brando’s The Wild One (1954), it served to

inflame youthful sentiment, adding tinder to a fire that was already

burning strong.

Adapted from a 1954 novel by Evan Hunter, Brooks’ film tells

the story of Richard Dadier (Ford), a war veteran facing his first

teaching assignment at a tough inner-city high school in an unspeci-

fied northern city. ‘‘This is the garbage can of the educational

system,’’ a veteran teacher tells Dadier. ‘‘Don’t be a hero and never

turn your back on the class.’’ Dadier’s class is the melting pot

incarnate, a mixture of Puerto Ricans, Blacks, Irish, and Italians

controlled by two students—Miller (Poitier) and West (Vic Morrow),

an Irish youth. West is portrayed as an embryo criminal, beyond

redemption, but Miller provides the emotional focus for the movie.

He is intelligent, honest, and diligent, and it becomes Dadier’s

mission to encourage him and develop his potential. However, in its

antagonism to Dadier, the class presents a unified front. They are

hostile to education in general and the teacher’s overtures in particu-

lar, and when he rescues a female teacher from a sexual attack by a

student the hostility becomes a vendetta to force him into quitting.

However, despite being physically attacked, witnessing the victimi-

zation of his colleagues, and withstanding wrongful accusations of

bigotry while worrying about his wife’s difficult pregnancy, Dadier

triumphs over the rebellious students and, by extension, the educa-

tional system. He retains his idealism, and in winning over his

students overcomes his own prejudices.

In setting the film against the background of Dadier’s middle-

class life and its attendant domestic dramas, it was assumed that

audiences would identify with him, the embattled hero, rather than

with the delinquent ghetto kids, but the film’s essentially moral tone is

subverted by the style, the inflections, and exuberance of those kids.

Following an assault by West and his cohorts, Dadier’s faith begins to

waver. He visits a principal at a suburban high school. Over a

soundtrack of students singing the ‘‘Star Spangled Banner’’ Dadier

tours the classrooms filled with clean-cut white students, tractable

and eager to learn. He may yearn for this safe environment, but to the

teenage audiences that flocked to The Blackboard Jungle, it is

Dadier’s inner city charges that seem vital and alive, while the

suburban high school appears as lively as a morgue. The teen

response to The Blackboard Jungle was overwhelming. ‘‘Suddenly,

the festering connections between rock and roll, teenage rebellion,

juvenile delinquency, and other assorted horrors were made explic-

it,’’ writes Greil Marcus. ‘‘Kids poured into the theaters, slashed the

seats, rocked the balcony; they liked it.’’

The instigation of teen rebellion was precisely the opposite

reaction to what the filmmakers had intended. From the opening title