Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BIG LITTLE BOOKSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

249

consisted of piano, string bass, drums, and sometimes guitar. In most

big band arrangements, sections played rhythmically unified and

harmonically diverse parts. While one section played the melody,

other sections would provide accented ‘‘riffs,’’ short musical motifs

repeated by one section. Arrangements often introduced riffs, high-

lighting one after another, culminating in all the riffs being played

simultaneously in a polyphonic climax. These arrangements mimic

the form of dixieland jazz, but since sections instead of soloists were

involved, the music had to be highly arranged and written and not

improvised. White bands, such as Goodman, Miller, and Herman’s,

became known for their elaborate arrangements in songs like ‘‘Sing,

Sing, Sing,’’ ‘‘In The Mood,’’ and ‘‘Woodchoppers Ball.’’ Black

Bands, such as Ellington, Cab Calloway, and Count Basie, became

known for a more driving beat and greater use of improvisation in

songs like, ‘‘Take the ’A’ Train,’’ ‘‘Minnie the Moocher,’’ and ‘‘Taxi

War Dance.’’

In addition to bringing more jazz influences into mainstream

American music, the big bands also developed some new techniques.

Duke Ellington trumpeter Bubber Miley was the first horn player to

place the working end of a plumber’s helper over his trumpet’s bell to

create a ‘‘wah-wah’’ effect. Swing music also favored a ‘‘four-beat’’

style in which emphasis was placed on all four beats per bar, while

older styles of jazz favored a ‘‘two-beat’’ style. By combining

elements of theatrical Tin Pan Alley style music, dance music, and

jazz, the big bands developed a music which was acceptable to a

widespread audience, while integrating elements of African Ameri-

can culture into the American mainstream. Many jazz purists see the

big band era as a time of jazzmen ‘‘selling out’’ to commercialism and

a period of creative stagnation, especially in light of the development

of bebop, cool jazz, and fusion music in the late 1940s, 1950s,

and 1960s.

The swing era ended as a result of the effects of World War II on

American society. The human toll of war dwindled the ranks of the

big bands, with notable losses like the death of Glenn Miller during a

concert tour for the troops. The end of wartime restrictions on

recorded music, and new developments in recording technology,

electric guitars, and radio led to the development of smaller groups

and a greater emphasis on singers over musicians. The growth of the

postwar baby boom generation created a market for music which, like

the swing music of their parents, was reinvigorated with elements of

African American music. Swing music, with the use of electric guitars

and infused with a blues tonality, became rock and roll music.

Big band music has continued to attract an audience, not only in

the United States, but around the world. Throughout the 1960s and

1970s, bands such as the Toshiko Akihoshi-Lew Tabackin continued

to further the big band sound, while Stan Kenton integrated third-

stream influences into his arrangements by adding strings, french

horns, and various percussion instruments, and Maynard Ferguson

incorporated jazz/rock fusion elements into his compositions. Big

band swing music has enjoyed its greatest resurgence in the late 1990s

with the newer, and mainly smaller, bands such as Big Bad VooDoo

Daddy, Royal Crown Revue (‘‘Hey Pachuco’’), Cherry Poppin’

Daddies (‘‘Zoot Suit Riot’’), and Squirrel Nut Zippers. Former

rockabilly guitarist Brian Setzer, of the Stray Cats, formed his own

big band using the same instrumentation as the most popular big

bands of the swing era, and scored a hit with Louis Prima’s ‘‘Jump,

Jive, and Wail.’’

—Charles J. Shindo

F

URTHER READING:

Berendt, Joachim E. The Jazz Book: From Ragtime to Fusion and

Beyond. Westport, Connecticut, Lawrence Hill & Company, 1982.

Erenberg, Lewis A. Swingin’ the Dream: Big Band Jazz and the

Rebirth of American Culture. Chicago, University of Chicago

Press, 1998.

Megill, Donald D., and Richard S. Demory. Introduction to Jazz

History. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 1984.

Stowe, David W. Swing Changes: Big-Band Jazz in New Deal

America. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1994.

Big Bopper (1930-1959)

Moderately famous during his lifetime, recording artist J. P.

(Jiles Perry) Richardson, better known as the Big Bopper, gained

lasting notoriety through his death in the airplane crash that killed

Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens near Mason City, Iowa.

Richardson was a successful disc jockey in Beaumont, Texas,

and a locally known songwriter and performer when he was discov-

ered by a Mercury Records producer. Half-spoken, half-sung record-

ings of ‘‘Chantilly Lace’’ and ‘‘The Big Bopper’s Wedding’’ made it

to the Top 40 during 1958 (the former to the Top Ten), while other

songs written by Richardson were recorded by more established artists.

He became a familiar fixture on rock and roll tours. It was during

a midwestern tour that a chartered airplane carrying three of the

headliners crashed shortly after takeoff on February 3, 1959, subse-

quently called ‘‘the day the music died’’ in Don McLean’s song

‘‘American Pie.’’

—David Lonergan

F

URTHER READING:

Nite, Norm N. Rock On Almanac. 2nd edition. New York,

HarperPerennial, 1992.

Stambler, Irwin. The Encyclopedia of Pop, Rock and Soul, revised

edition. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

Big Little Books

The 1932 debut of Big Little Books was an important harbinger

of the direction marketing to children would take in the future. The

first inexpensive books available for children, Big Little Books were a

precursor to the comics and such series as the Golden Books. The

books were sold in dimestores such as Kresge and Woolworth where

children could purchase them with their own spending money.

The Whitman Company, a subsidiary of the Western Publishing

Company of Racine, Wisconsin, published the books. The first of the

Big Little Books was The Adventures of Dick Tracy Detective, which

was published in 1932. Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Orphan Annie,

Popeye, Buck Rogers, Don Winslow, and Tarzan were among the

many additional heroes. The popularity of the books had other

publishers, such as Saalfield Publishing, Engel Van Wiseman, and

BIG SLEEP ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

250

Lynn Publishing, soon producing their own similar series. Approxi-

mately 508 Big Little Books were published between 1932 and 1949,

but in the late 1930s the name changed to Better Little Books.

In pre-television days, Big Little Books provided the popular

‘‘action hero’’ and ‘‘girl’’ stories for school age children. Eventually

the line was expanded to include retellings of classical literature such

as Little Women and The Three Musketeers, cartoon characters from

the popular funny papers, and even heroes and heroines taken from

radio and movies, such as two books about Mickey Rooney. The

books continued to be published into the 1970s, but, once comic

books and other children’s book series had come onto the market,

were never as popular as they had been in the 1930s and 1940s.

In the 1990s Big Little Books were considered a collector’s item.

Because the printing sizes varied with individual titles, some are

scarcer than others and therefore, more valuable. Another factor

affecting their value is their condition. Among the most sought after

are The Big Little Mother Goose and the Whitman-produced premi-

ums from cereal boxes and other products.

—Robin Lent

F

URTHER READING:

Jacobs, Larry. Big Little Books: A Collector’s Reference & Value

Guide. Padukah, Kentucky, Collector Books, 1996.

L-W Books, Price Guide to Big Little Books & Better Little, Jumbo,

Tiny Tales, A Fast-Action Story, etc. Gas City, Indiana, L-W Book

Sales, 1995.

Tefertillar, Robert L. ‘‘From Betty Boop to Alley Oop: A Big

Bonanza of Big Little Books.’’ Antiques & Collecting. Vol. 99,

No. 5, 1994, 47-49.

The Big Sleep

In The Simple Act of Murder (1935) Raymond Chandler (1888-

1959), one of America’s premier hard-boiled novelists, wrote of his

detective hero, Philip Marlowe, ‘‘ . . . down these mean streets a man

must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.

The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero;

he is everything.’’ Unlike James M. Cain and other hard-boiled

novelists of his time, Chandler was a romantic whose famous detec-

tive was a knight in slightly battered armor. Marlowe appears in

Chandler’s four most famous novels, The Big Sleep (1939), Farewell

My Lovely (1940), The Lady in the Lake (1943), and The Long

Goodbye (1953) as well as several lesser known works. Philip

Marlowe was a character made for Hollywood: street smart, wise

cracking but ultimately an honorable man—a prototype for the

American detective hero ever since. Several of Chandler’s stories,

including The Big Sleep, were made into Hollywood movies, some

more than once.

In The Big Sleep Marlowe is hired by wealthy General Sternwood

to track down a blackmailer who is trying to extort money out of him

with nude pictures of his daughter Carmen. From this rather simple

beginning, Marlowe is led into a tangled world of sexual perversion,

drug addiction, murder, and deceit. The plot of The Big Sleep is

complex, leading Howard Hawks, the first and most successful of the

filmmakers to adapt it for the movies, to say that he never did

understand who killed one of the characters—and when he tele-

graphed Chandler for clarification, Chandler himself was unable to

provide a definitive answer.

The world of The Big Sleep has much in common with the world

in other hard-boiled novels and films noir. It is a dark world full of

violent and twisted men and women—often the most beautiful and

charming are the most savage of all. Chandler’s description of

Carmen Sternwood is instructive: ‘‘She came over near me and

smiled with her mouth and she had little sharp predatory teeth.’’ Even

Carmen’s father describes her as ‘‘a child who likes to pull the wings

off flies.’’

What sets Chandler apart from other hard-boiled writers is that

his work has a moral center in the honorable Marlowe who always

prevails in the end—beaten up, disappointed, and cynical, but at the

heart of a universe which has a moral standard no matter how

threatened it is. Other novels in this genre, like Double Indemnity, are

less reassuring on this score.

Howard Hawks cast Humphrey Bogart, one of Hollywood’s

most famous tough guys, as Marlowe. No one has played Marlowe as

successfully as Bogart, who had a world weary face and a suitably

sarcastic delivery on such classic Chandler lines as ‘‘I’m thirty-three

years old, went to college once, and can still speak English if there’s

any demand for it. There isn’t much in my trade.’’

Hawks’ The Big Sleep (1946) is better realized than the Michael

Winner version in 1978 which starred Robert Mitchum and is set not

in California (where many hard-boiled novels and films are set, and

from which they take their flavor), but in London of the 1970s.

However, the main problem with Hawks’ version, which has generat-

ed a good deal of critical interest on its own, is that it ends with

Marlowe and Vivian Sternwood falling in love; in the novel Marlowe

is the archetypal loner—he must stand apart from the world and its

corruption. In true Hollywood fashion this change was made to

capitalize on the real world relationship between Bogart and Lauren

Bacall, who was cast as Vivian (Bogart left his wife for the very

young Bacall during this time, causing a mild Hollywood scandal).

This fiscally motivated plot change, however, weakens the noir

aspect of the film, and along with the changes which the censorship

laws of the era demanded, makes it a far less disturbing experience

than the novel.

In some ways The Big Sleep seems to be unpromising material

for Hawks, who tended to make either action films or comedies.

Unlike Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder, who came to film noir from the

downbeat German Expressionist cinema of the 1920s, Hawks’ cine-

ma is an optimistic one, filled with action, charm, sly humor, and

characters who value professionalism and who are ‘‘good enough’’ to

get a job done. Analyses of the adaptation of novels to films, however,

often founder on arguments about the faithfulness of the adaptation.

The film is a new work with virtues of its own and as David Thomson

writes, Hawks’ version is vastly different than Chandler’s original in

that it ‘‘inaugurates a post-modern, camp, satirical view of movies

being about other movies that extends to the New Wave and

Pulp Fiction.’’

—Jeannette Sloniowski

F

URTHER READING:

Chandler, Raymond. The Big Sleep. New York, Vintage Books, 1976.

———. The Simple Art of Murder. New York, Pocket Books, 1964.

BIGFOOTENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

251

Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart in a scene from the film The Big Sleep.

Kuhn, Annette. ‘‘The Big Sleep: Censorship, Film Text, and Sexuali-

ty.’’ The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and

Sexuality. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985.

Mast, Gerald. Howard Hawks, Storyteller. New York, Oxford Uni-

versity Press, 1982.

Speir, Jerry. Raymond Chandler. New York, Frederick Ungar Pub-

lishing Co., 1981.

Thompson, David. The Big Sleep. London, British Film Institute

Press, 1997.

Walker, Michael. ‘‘The Big Sleep: Howard Hawks and Film Noir.’’

The Book of Film Noir. Edited by Ian Cameron. New York,

Continuum, 1993.

Bigfoot

The North American equivalent of the legendary ‘‘Abominable

Snowman’’ or Yeti of the Himalayas, ‘‘Bigfoot,’’ whether he exists

or not, has been a part of American popular culture since the late

1950s, with isolated reports stretching back even earlier. Bigfoot, also

known as ‘‘Sasquatch’’ in Canada, is the generic name for an

unknown species of giant, hair-covered hominids that may or may not

roam the forests and mountains of the American Northwest and the

Alberta and British Columbia regions of Canada. According to a

synthesis of hundreds of eyewitness sightings over the years, the

creatures are bipedal, anywhere between seven to nine feet tall (with a

few specimens reportedly even taller), and completely covered in

black or reddish hair. They appear to be a hybrid of human and

ape characteristics. Also, they are omnivorous and usually solitary.

On occasion, they leave behind enormous footprints (hence the

name ‘‘Bigfoot’’), measuring roughly between 16 and 20 inches.

Cryptozoologists (those who study animals still unknown to science)

hold out at least some hope that Bigfoot, hidden away in the last really

undeveloped wilderness areas of North America, may yet prove to be

a reality and not merely a folk legend.

Hairy hominids have been reported in nearly every state in the

nation. However, classic American Bigfoot sightings are typically

confined to northern California, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

Additionally, sightings outside of this region often involve some

paranormal or supernatural overtones; by contrast, the Pacific North-

west Bigfoot seems decidedly flesh and blood, if elusive. Advocates

of Bigfoot’s existence often begin by pointing back to Native Ameri-

can legends of human-like giants, such as the Wendigo of the

Algonkians, in the forests of these regions. The alleged capture of a

BILINGUAL EDUCATION ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

252

small Sasquatch (or escaped chimpanzee) named ‘‘Jacko’’ as report-

ed in the British Columbia newspaper the Daily British Colonist in

1884 marks the introduction of Bigfoot to the modern mass media

age. In the first few years of the 1900s, a spate of published

eyewitness reports of Sasquatches in Canada grabbed attention through-

out the Northwest. During the 1930s, the popular British Columbian

writer J.W. Burns wrote about a Sasquatch who was a giant, atavistic

Indian. However, it was not until 1958 that newspaper accounts of

large, human-like footprints discovered by a bulldozer operator

named Jerry Crew near a construction site in Willow Creek, Califor-

nia, popularized the term ‘‘Bigfoot’’ for the rest of America. At

approximately the same time, a man from British Columbia named

Albert Ostman made public his story of being kidnapped and held

captive for six days by a group of Sasquatches back in 1924. Ostman

only managed to escape, he claimed, when the Sasquatches became

sick on his chewing tobacco. Over the years, in spite of skeptical

questioning by a number of renowned cryptozoologists, Ostman

stuck to his seemingly incredible story.

With the explosion of Bigfoot into public awareness, a number

of investigators took to the American northwest to find anecdotal or

physical evidence of the existence of the unknown hominid species.

Some of the most famous of these investigators were Rene Dahinden,

John Green, and Ivan T. Sanderson. The decade of the 1960s was

somewhat of a ‘‘golden era’’ in the hunt for Bigfoot, when the

mystery was new enough to most Americans to capture widespread

interest and just plausible enough for many minds to remain open on

the subject. Literally hundreds of eyewitness reports were collected

and published in the many popular books written by these investiga-

tors. One of the most dramatic of the reports described a terrifying

nocturnal attack by ‘‘apemen’’ upon miners in a remote cabin near

Mt. St. Helens back in 1924. (The story has since been discredited.)

But by far the most sensational—and hotly disputed—physical

evidence of that period is the 28-second, 16-millimeter film taken in

1967 by Roger Patterson in the Bluff Creek area of the Six Rivers

National Forest in California. The film shows what appears to be a

female Bigfoot striding away from Patterson’s camera. Patterson,

accompanied by Bob Gimlin, had taken to the woods in a specific

attempt to find and photograph the elusive Bigfoot—a fact which was

not lost upon the film’s numerous skeptics. However, if the film is a

hoax, no one has ever confessed or turned up with a female Bigfoot

suit. Frame-by-frame analysis and extensive investigation of the site

and the backgrounds of the men involved has so far failed to provide

conclusive evidence of deception. Patterson died in 1972, still insist-

ing that he had filmed the real thing. Other Bigfoot films have

surfaced from time to time, but unlike Patterson’s, most of them have

been clearly bogus.

In the early 1970s, a series of popular books and documentaries

about Bigfoot appeared and further ensured the cultural longevity of

the phenomenon. Inevitably, Bigfoot became a tourist draw for some

areas in the Pacific Northwest, and towns and businesses were quick

to capitalize upon the name. A few highly publicized expeditions to

find and/or capture Bigfoot met with no success. Since that time, the

media furor over Bigfoot has subsided, but occasional reports still

gain widespread publicity. For example, a sighting in the Umatilla

National Forest in Washington in 1982 led to the collection of

numerous plaster casts of alleged Bigfoot tracks. A respected anthro-

pologist from Washington State University named Grover Krantz

argued for the tracks’ authenticity, although other scientists remained

unconvinced. The skepticism of the scientific community notwith-

standing, Krantz and primatologist John Napier still remain open to

the possibility that Bigfoot is more than a legend and mass delusion.

For the most part, however, the case for Bigfoot’s existence has

departed from the front pages and now remains in the keeping of a

small number of dedicated investigators prowling through the North-

west woods with plaster and cameras and in some cases tranquilizer

darts, ready to make cryptozoological history by presenting the

scientific and journalistic world with irrefutable proof of America’s

mysterious apeman.

—Philip L. Simpson

F

URTHER READING:

Coleman, Loren. The Field Guide to Bigfoot, Yeti, and other Mystery

Primates Worldwide. New York, Avon, 1999.

Green, John. Encounters with Bigfoot. Surrey, British Columbia,

Hancock House, 1994.

Hunter, Don. Sasquatch/Bigfoot: The Search for North America’s

Incredible Creature. Buffalo, New York, Firefly Books, 1993.

Napier, John. Bigfoot. New York, Berkley, 1974.

Sanderson, Ivan T. Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life.

Philadelphia, Chilton, 1961.

Sprague, Roderick, and Grover S. Krantz, editors. The Scientist Looks

at the Sasquatch. Moscow, Idaho, University Press of Idaho, 1979.

Bilingual Education

Bilingual education developed into a particularly contentious

topic for defining American identity in the twentieth century. While

federal legislation since the 1960s has recognized the United States as

a multilingual nation, the professed long-range goal of institutional-

ized bilingual education was not that students should achieve

BILLBOARDSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

253

bilingualism but proficiency in English. The vast majority of bilin-

gual education programs were considered ‘‘transitional,’’ function-

ing to introduce younger students with limited English-speaking

ability into the general education curriculum where English served

historically as the language of instruction. Many bilingual programs

were taught principally either in English or in the primary language of

the student. However, by the end of the twentieth century, federally

funded programs had begun to favor instruction in both English and

the primary language, an apparent departure from the goal of achiev-

ing proficiency in a single language.

The country’s continued difficulty through the late twentieth

century in educating immigrant children, mostly from Spanish-

speaking countries, forced the federal legislature to institutionalize

bilingual education. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act

(1964), Congress passed the Bilingual Education Act (1968), provid-

ing the first federal funds for bilingual education. The federal govern-

ment elaborated its guidelines in the amended Bilingual Education

Act of 1974, the same year the Supreme Court rendered its landmark

Lau vs. Nichols decision, ruling that instructing students in a language

they do not understand violates the Fourteenth Amendment of

the Constitution.

‘‘Bilingual’’ was often interpreted as ‘‘bicultural,’’ suggesting

that the question of bilingual education belonged to a broader debate

over the efficacy of a polyglot society. The discussion in the United

States focused on the progress of social mobility and the development

of a unique American culture. For many, proficiency in English

appeared to facilitate social advancement and incorporation into a

mainstream culture despite that culture’s multifaceted character. The

letters of J. Hector St. Jean de Crèvecoeur in the late eighteenth

century and Alexis de Tocqueville’s published travels Democracy in

America in 1835 contributed to an understanding of American culture

as a ‘‘melting pot’’ of ethnicity. This identity became increasingly

complex with the country’s continued expansion through the nine-

teenth century and increasingly vexed with the rise of nationalism in

the post bellum era. The nationalist urgency to homogenize the nation

after the Civil War, accompanied by notions of Anglo-Saxon su-

premacy and the advent of eugenics, forced further eruptions of

nationalist sentiment, including loud, jingoist cries for a single

national language after the first World War. However, by the middle

of the twentieth century, efforts to empower underrepresented com-

munities contributed to an increased public interest in multiculturalism

and ethnocentric agendas. A dramatic increase in immigration from

Spanish-speaking countries during the second half of the twentieth

century finally motivated the United States to institutionalize

bilingual education.

But the strong opposition to the bilingual education legislation

of the early 1970s, expressed in the influential editorial pages of the

Washington Post and the New York Times between 1975 and 1976,

suggested that bilingual programs never enjoyed overwhelming pub-

lic support. The articulate arguments of Richard Rodriguez, an editor

at the Pacific News Service and author of Hunger for Memory

(1982), contributed to this opposition by distinguishing between

private (primary language) and public (English) language while

influential figures like Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Arthur M.

Schlesinger, Jr., author of The Disuniting of America (1992), docu-

mented an increased national disenchantment with multiculturalism

and bilingual education.

Discussions of bilingual education more often centered on

Latino communities in metropolitan areas such as Miami, Los Ange-

les, and New York. But the debate was not exclusively Latino. The

Lau vs. Nichols verdict, which involved a Chinese-speaking student,

along with the advent of post-Vietnam War Asian immigration,

suggested that the debate was relevant to other communities in the

country. Similar interests were present in localized but nationally

observed efforts to incorporate the language of a surrounding com-

munity into a school’s curriculum. A particularly contentious and

widely publicized debate arose over ‘‘Ebonics’’ in Oakland, Califor-

nia, in the early 1990s. Due in part to increasing black nationalism

among African American intellectuals, prominent national political

figures such as Reverend Jesse Jackson endorsed the incorporation of

the local dialect and vernacular variations of language into the

curriculum, while figures such as Harvard sociologist Cornel West

and Harvard literary and social critic Henry Louis Gates, Jr., suggest-

ed that such programs lead to black ghettoization.

California showcased a national concern about bilingual educa-

tion at the end of the twentieth century. Bilingual education became

increasingly contentious in the state in the late 1990s with the passage

of a proposition eliminating bilingual instruction. Approval of the

initiative occurred in the shadow of two earlier state propositions and

a vote by the regents of University of California to effectively

terminate Affirmative Action, acts widely perceived in some

underrepresented communities as attacks directed at Latino and

immigrant communities. Bilingual programs enjoyed public support

in cities with wide and long established minority political bases, such

as Miami, where they where viewed as beneficial to developing

international economies, but California continued to focus the debate

primarily on social and cultural concerns.

—Roberto Alvarez

F

URTHER READING:

Lau vs. Nichols. United States Supreme Court, 1974.

Porter, Rosalie Pedalino. Forked Tongue: The Politics of Bilingual

Education. New York, Basic, 1990.

Rodriguez, Richard. Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard

Rodriguez. Boston, David R. Godine, 1982.

Schlesinger, Arthur, Jr. The Disuniting of America. New York,

Norton, 1992.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. Democracy in America. 1835.

Billboards

From simple barnside advertisements and other billboarding

techniques of the early 1900s, to today’s huge high-tech creations on

Los Angeles’ Sunset Strip, billboards and outdoor advertising have

been an integral part of both the landscape and the consciousness of

America since the evolution of the American car culture of the early

twentieth century.

Like many twentieth-century phenomena, the modern advertis-

ing spectacle, which the French have termed gigantisme, actually

dates back to ancient times and the great obelisks of Egypt. By the late

1400s billboarding, or the mounting of promotional posters in con-

spicuous public places, had become an accepted practice in Europe.

Wide-scale visual advertising came into its own with the invention of

lithography in 1796, and by 1870 was further advanced by the

technological progress of the Industrial Revolution.

BILLBOARDS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

254

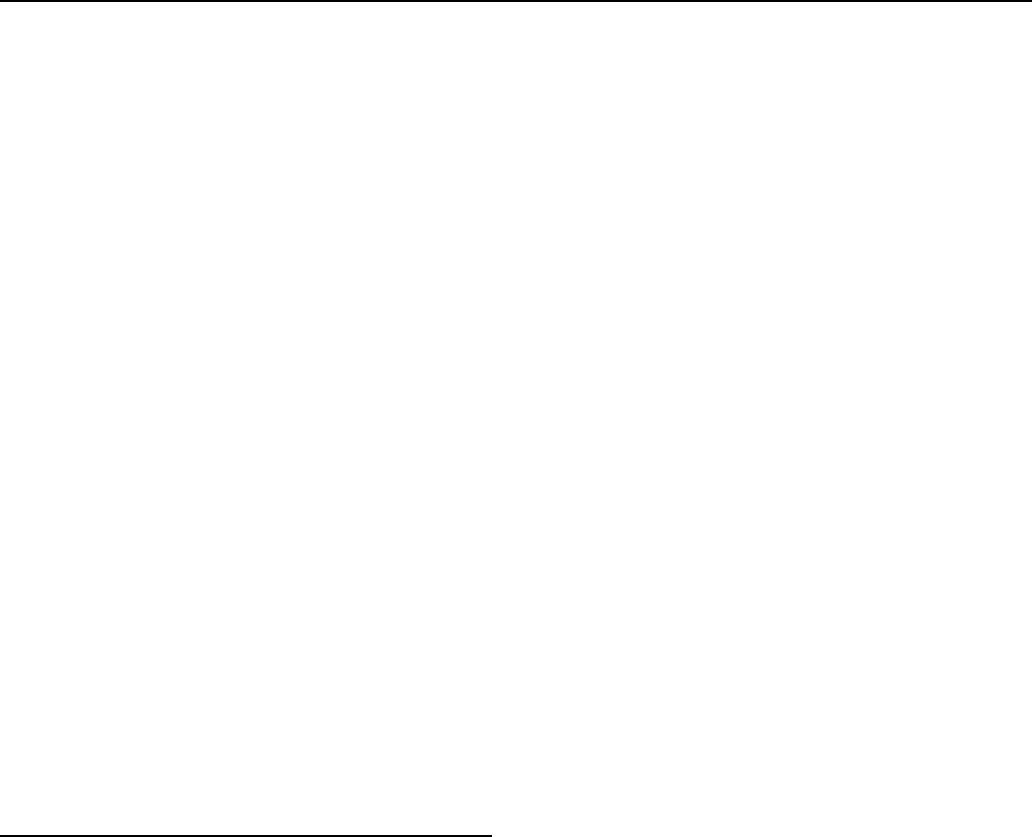

A billboard in Birmingham, Alabama, 1937.

In America early advertising techniques were relatively naive,

involving melodramatic situations, body ills, hygiene, and testimoni-

als. Even so, the impact of subliminal suggestion was not unknown,

and merchandising through association, with glamour, prestige, sex,

and celebrities being the most popular ploys, was discovered early on.

Thus, with few variations, the tenets of modern advertising were

firmly in place by the twentieth century.

Predecessors of the modern billboard were posters for medicine

shows, theatrical troupes, and spots events, and especially famous

were those showing exaggerated versions of Barnum and Bailey’s

circus and Wild West acts. Initially no legal restrictions were placed

on the posting of signs, and billboarding became part of the early

entertainment world, with representatives traveling ahead of compa-

nies and competitively selecting choice locations which were then

rented or leased. Thus these poster salesmen became the first pioneers

of the outdoor advertising industry.

By the turn of the twentieth century, economic growth peaked in

both Europe and America, creating new markets for both products

and information. With the development of the automobile in the early

1900s, the stage was set for the rise of the roadside billboard. Sally

Henderson notes: ‘‘An intense connection between the automobile,

auto travel, and the outdoor poster (or billboard) was the natural

outcome of a society in which individuals were becoming increasing-

ly mobile. The outdoor ad had been waiting all along for the one

product to come along that would change the world’s habits, styles of

living, and advertising modes: the automobile.’’

Early billboards were fairly austere, really posters with some

kind of framing effect, but with the 1920s both design and the

billboard setting (or frame) developed along more aesthetic lines. The

focus of a deluxe 1920s billboard was colorful and ornate illustration,

in a stylized but usually realistic (if idealized) mode. Product names

were emphasized; and messages, if any, were understated and con-

cise. Frames were wooden, mostly painted white, and often mounted

on a base of lattice-work panels. Elaborate set-ups included end

supports in the form of female figures. These were similar to the

caryatid figures found in Greek architecture and were called lizzies.

Billboards in the 1920s might also be highly accessorized, including

shaded electric light fixtures and illuminated globes, picket fences,

and a plot of flowers.

While the first fully electrical billboards appeared in New York

in 1891, standard billboard style did not really change a great deal

until the 1950s, though with World War II advertisers promoted war

bonds along with products, not only out of patriotism, but because

they were also given tax breaks to do so. Propagandistic visions of

battleships, explosive war scenes, along with promises for a brighter,

better tomorrow (to be provided, of course, by the products of the

companies sponsoring the billboards) shared space with familiar

commercial trademarks during World War II.

In the affluent post war 1950s, an age of cultural paradox when

social values were being both embraced and questioned, outdoor

advertising finally entered the modern age. A burgeoning youth

market also first emerged during this decade, and all these mixed

trends were reflected in mass advertising that was both more innova-

tive and less realistic. The 1950s were the ‘‘Golden Age of Paint.’’

Painting made possible bigger, glossier presentations, enabling bill-

boards (like the 3-D movies of the early 1950s) to transcend their flat

surfaces, as TWA (Trans World Airlines) planes and Greyhound

buses suddenly seemed to emerge from the previously circumscribed

space of the traditional billboard.

Youth culture in the 1950s exploded into the mid-1960s psyche-

delic era, and was reflected in the color-drenched surrealism and Op

Art effects of billboards now aimed at the under 30 generation, whose

ruling passions were fashion, sexuality, and entertainment. Billboards

increasingly suggested gigantic recreations of rock LP jackets, and

(like certain album covers) sometimes did not even mention the name

of the group or product. The Pop Art movement, an ironic, but wry

comment on an increasingly materialistic society, blurred the distinc-

tion between the fine and commercial arts, and billboards, along with

Campbell’s soup cans, were considered worthy of critical appraisal.

Evolving out of the youth mania was the young adult singles market,

and images of the wholesome American family gave way to solo

visions of the ruggedly independent Marlboro man and the sexy Black

Velvet woman.

As 1970s consumerism replaced 1960s idealism another art

movement, Photorealism, became an important element of outdoor

advertising, as billboards came to resemble huge, meticulously de-

tailed Photorealist paintings. In the 1980s and 1990s, the failure of

any influential art movement to emerge after Photorealism, or indeed

the absence of any discernible cultural movements comparable to

those of the 1950s or 1960s, contributed to the increasingly generic, if

admittedly grandiose high-tech quality of much mainstream advertis-

ing. Cued by rapid changes in signage laws and property ownership, a

movable billboard was developed in the 1980s. Inflatables, both

attached to signs (such as a killer whale crashing through a Marineland

billboard) and free-standing like huge Claes Oldenburg soft sculp-

tures, have heightened the surreality of modern life with advertising

in three-dimensions.

BIRDENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

255

While some critics view billboards as outdoor art and socio/

cultural barometers, concern over the environment and anti-billboard

lobbying commenced in the late 1950s, and a 1963 study drew the

first connection between the prominent placement of billboards along

the New York State Thruway and traffic accidents. Certain minimal

standards were established, and today’s most grandiose billboards are

confined to urban districts such as New York’s Times Square, and the

Las Vegas and Los Angeles strips, modern meccas whose identities

have been virtually defined by the blatant flaunting of their flashy

commercial accouterments. But Sally Henderson has also called Los

Angeles’ famed Sunset Strip ‘‘a drive-through gallery, a lesson in

contemporary art . . . a twentieth-century art experience, quick and to

the point.’’ In the entertainment capital of the world, however, a

billboard on the Strip remains as much a gigantic status symbol as an

advertising tool or Pop Art artifact.

Pop Art or visual pollution, the outcry against billboards of

previous decades has subsided into stoic acceptance of an inescapable

tool of capitalism, and one which relentlessly both tells and shows the

public that the best things in life are emphatically not free (though

actual prices remain conspicuously absent from most billboards). In a

unique instance of one pervasive visual medium being used as an

effective signifying device within another, however, critical comment

on billboards has been immortalized in the movies. Billboards in

films are often seen as characteristic signifiers of the ills and ironies of

both the American landscape, and the American Dream itself.

In a more optimistic mode, older film musicals used electrical

billboards to symbolize the glamour of the big city and stardom.

Singin’ in the Rain (1952) climaxes with a ballet in which a vast set

composed of towering Broadway electric signs suddenly blazes to life

to illuminate Gene Kelly, who had previously been isolated in

darkness. While a visually spectacular moment, the shot also signifies

that aspiring dancer Kelly has finally ‘‘arrived’’ at the apex of his

dreams. The same message is reenforced at the film’s end when Kelly

and Debbie Reynolds are seen standing in front of a billboard that

mirrors the couple in an advertisement for their first starring roles in a

big movie musical. In a more satirical vein, It Should Happen To

You’s (1954) Judy Holliday makes a name for herself by plastering

her moniker on a Columbus Circle billboard. The concept of the film

was allegedly based on a real publicity stunt by Mamie Van Doren’s

agent, and similar billboards promoting Angelyne, a ‘‘personality’’

with no discernible talent or occupation, are still fixtures of modern

day Los Angeles.

In later films, billboards were employed as an instantly recogniz-

able symbol of a materialistic culture that constantly dangles visions

of affluence in front of characters (and thus a public) who are then

programmed for a struggle to achieve it. No Down Payment (1957), an

exposé of suburban life, opens with shots of billboards hawking real

Los Angeles housing developments, while glamorous but Musak-like

music plays on the soundtrack. No Down Payment was among the

first spate of 1950s films shot in CinemaScope, and the opening

images of huge California billboards draw a perhaps unintentional

parallel between the shape and scale of the American billboard, and

the huge new wide-screen projection process that Hollywood hoped

would lure patrons away from their new television sets and back into

movie theaters.

Billboards are used to even more cynical effect in Midnight

Cowboy (1969). With an outsider’s sharp eye for the visual clutter of

the American landscape, British director John Schlesinger (who had

already shown keen awareness of the ironies of modern advertising in

Darling, 1965) uses American billboards throughout the film as an

ironic counterpoint to a depressing saga of a naive Texan who aspires

to make it as a hustler in the big city. Billboards cue flashbacks to Joe

Buck’s troubled past life on his bus journey to New York, taunt him

with images of affluence as he later wanders destitute through the

mean streets of the city, and finally, on their bus journey south at the

end of the film, cruelly tantalize both Joe and his ailing companion,

Ratso Rizzo, with glossy images of a paradisal Florida which one of

them will not live to see.

One of the more bizarre uses of billboard gigantisme in modern

cinema is Boccaccio ’70 (1962), which also offers a wickedly sly

comment on the obsessive use of larger-than-life sexual symbolism in

modern outdoor advertising. In the Fellini ‘‘Temptation of Dr.

Antonio’’ episode a gigantic figure of Anita Ekberg comes to life and

steps down from a billboard on which the puritanical doctor has been

obsessing to erotically torment him to the strains of an inane jingle

imploring the public to ‘‘drink more milk!’’

—Ross Care

F

URTHER READING:

Blake, Peter. God’s Own Junkyard The Planned Deterioration of

America’s Landscape. New York/Chicago/San Francisco, Holt,

Rinehart, and Winston. 1964.

Fraser, James Howard. The American Billboard: 100 Years. New

York, Harry Abrams, 1991.

Henderson, Sally, and Robert Landau. Billboard Art. San Francisco,

Chronicle Books, 1980.

The Bionic Woman

One of the first female superheroes on prime-time television, the

Bionic Woman originated as a character on the popular show The Six

Million Dollar Man. The Bionic Woman was created on that show

when Steve Austin’s fiancée suffered a near-fatal parachute accident

and was rebuilt with a bionic arm, legs, and ear. Her nuclear-powered

prostheses gave her super strength, speed, and hearing, which compli-

mented Steve Austin’s bionic powers as they solved crimes and

wrongdoings together. Lindsey Wagner starred as the bionic Jamie

Sommers and parlayed the Bionic Woman’s guest spots on The Six

Million Dollar Man into a two-year run in her own series, which ran

from 1976 to 1978, and later, years of syndication. The Bionic Woman

could be seen on cable television in the late 1990s.

—P. Andrew Miller

F

URTHER READING:

Douglas, Susan J., Where the Girls Are: Growing Up Female with the

Mass Media. New York, Times Books, 1994.

Bird, Larry (1956—)

Born in 1956 and raised in rural Indiana—a place where basket-

ball has been popular as a spectator sport since the 1910s and 1920s,

well before the establishment of successful professional leagues in the

1940s—Larry Bird emerged as one of the premiere sports superstars

BIRD ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

256

Lindsey Wagner in a scene from The Bionic Woman.

of the 1980s, as well as one of the most marketable athletes in the

National Basketball Association (NBA). Often credited with helping

to revive a then-troubled league—along with Earvin ‘‘Magic’’ John-

son—Bird’s discipline, unselfish playing style, and enthusiasm for

the game made him a hero to basketball fans around the world and a

driving force in the NBA’s growth.

Bird attained celebrity early in his career; four thousand people,

twice the population of his hometown of French Lick, Indiana,

attended his final high school game there in 1974. After a short stint at

Indiana University, Bird left to play for the Indiana State Sycamores

in 1975. During his college career, season ticket sales for the

formerly-lagging Sycamores tripled. His college years culminated in

a host of honors for Bird, who finished college as the fifth highest

scorer in college basketball history. He was named the College Player

of the Year (1978-1979), and led his team to a number one ranking

and the national championship game. This game, which the Sycamores

lost to Earvin ‘‘Magic’’ Johnson’s Michigan State team, marked the

beginning of the Bird-Johnson rivalry that would electrify profession-

al basketball for the next 12 years.

Originally drafted by the Boston Celtics while he was still in

college, Bird joined the team in the 1979-1980 season and proceeded

to lead it to one of the most dramatic single-season turnarounds in

league history. The year before his NBA debut, the Celtics had won

only 29 games and did not qualify for the league playoffs; the 1979-

1980 team won 61 games and finished at the top of the Atlantic

Division. Bird’s accomplishments as a player are remarkable: he was

named the NBA’s Most Valuable Player in 1984, 1985, and 1986; he

played on the Eastern Conference All-Star team for 12 of his 13 pro

seasons; he led his team to NBA Championships in 1981, 1984, and

1986; and he won a gold medal in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics as a

member of the ‘‘Dream Team’’ (an elite group that also featured his

rival, Johnson, as well as Michael Jordan and other superstar players).

Hobbled by back injuries and absent from many games in his last two

seasons, Bird retired from basketball in 1992. He was inducted into

the NBA Hall of Fame on October 2, 1998.

Contributing to the growing prosperity of the NBA in the 1980s

and to its emergence as a popular and profitable segment of the

entertainment industry were several factors, not least of which were

the marketing efforts of league commissioner David Stern. The

league used the appeal of its top stars—especially Bird, Johnson, and

Jordan—to market itself to fans. Another factor in the league’s

growth was the fan interest triggered by the intense rivalry between

the league’s top two teams, the Celtics and the Los Angeles Lakers,

which happened to be led by the league’s top two players, Bird and

Johnson. The Celtics and Lakers met in the NBA Finals three times in

the mid-1980s, the excitement of their rivalry being amplified by the

charisma of Bird and Johnson; the historic competition between the

two teams in the 1960s; and the contrast between their two fundamen-

tally different styles of basketball—East Coast fundamentals vs. West

Coast razzle-dazzle.

As Bird and Johnson became the league’s brightest stars and as

their teams won championships, they helped the NBA to embark on a

new era of soaring attendance, sold-out games, escalating salaries,

and lucrative television and sponsorship deals in which the players

themselves became heavily marketed international celebrities. In-

creasing both his own income and his stake with fans, Bird appeared

in television commercials for several companies, most prominently

McDonalds and Converse Shoes.

In order to allow the Celtics and Lakers to keep Bird and Johnson

on their teams, the NBA restructured itself economically in 1984,

passing an exception to its salary-cap rules that would become known

as the ‘‘Larry Bird Exception.’’ This move allowed teams to re-sign

their star players at exorbitant costs, regardless of the team’s salary

limit, and led to skyrocketing player salaries in the late 1980s

and 1990s.

In 1997, Bird was hired as head coach of the Indiana Pacers. In

his first year of coaching, Bird had an effect on his team that recalled

his impact as a player nearly two decades earlier. Whereas in 1996 the

Pacers had won only 39 games, in 1997 they won 58 and competed in

the Eastern Conference championship series against Michael Jor-

dan’s Chicago Bulls. At the season’s conclusion, Bird was named

NBA Coach of the Year.

In the sometimes racially-charged world of professional athlet-

ics, Bird’s position as a prominent white player garnered much

commentary. ‘‘[Bird is] a white superstar,’’ Johnson said of his rival

in a 1979 interview in Sports Illustrated. ‘‘Basketball sure needs

him.’’ Early in its history, professional basketball had attracted few

African American players (due both to societal racism and the success

BIRKENSTOCKSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

257

Larry Bird (right)

of the all-black Harlem Globetrotters), but by 1980, 75 percent of

NBA players were African American. Thus, Bird entered a scene in

which white stars were indeed rare. Critics labeled his Celtics a

‘‘white boy’s team,’’ and sportswriters still debated whether African

Americans might be somehow inherently more adept at sports than

whites. Bird himself referred to this stereotype when he said that he

had ‘‘proven that a white boy who can’t run and jump can play

this game.’’

Bird’s impact—both as a player and as a coach—is unparalleled;

he helped to change losing teams into champions and a declining

professional league into a vibrant and profitable sports and entertain-

ment giant. From a humble high school gymnasium in rural Indiana,

Bird came to international attention as one of the best known and most

successful athletes in the history of professional sports.

—Rebecca Blustein

F

URTHER READING:

Bird, Larry, with Bob Ryan. Drive: The Story of My Life. New York,

Bantam, 1990.

George, Nelson. Elevating the Game: Black Men and Basketball.

New York, Harper Collins, 1992.

Hoose, Phillip M. Hoosiers: The Fabulous Basketball Life of Indiana.

New York, Vintage Books, 1986.

Rader, Benjamin G. American Sports: From the Age of Folk Games to

the Age of Spectators. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice

Hall, 1983.

Birkenstocks

Birkenstocks—the name commonly used for sandals made by

the Birkenstock Company—are the parent of ‘‘comfort shoes’’ in the

United States. Called hari krishna shoes, monk shoes, Jesus sandals,

and nicknamed granolas, Jerusalem cruisers, tree huggers, Flintstone

feet, hippie shoes, and beatniks, they have carried numerous social

connotations. Nevertheless, the influence that Birkenstocks have had

on what Americans wear on their feet goes beyond alternative

trappings. Not only have they become a household word in the 1980s,

but they have also joined the likes of Nikes in gaining name-

brand recognition.

Birkenstocks were created by a family of German shoemakers.

Emphasizing comfort rather than fashion, the original Birkenstocks

were open-toed, leather-strapped, flat-heeled, slip-ons. In 1964, Karl

Birkenstock combined a flexible arch support and a contoured sole—

inventions his grandfather Konrad had engineered at the turn of the

twentieth century—into an orthopedic shoe. The ergonomically de-

signed sole is shaped like a footprint in wet sand, with cupped heel

and raised bar where the toes meet the ball of the foot. The pliable

insole is a cork/latex matrix sandwiched between layers of jute and

covered in suede leather.

Margot Fraser introduced Birkenstocks to the United States in

1966. While visiting her native Germany she bought a pair to alleviate

her foot pain. Back in northern California, she sold a few pairs to

friends, never intending to start a business. Quickly convinced that

everyone would benefit from such comfortable shoes, she began

importing them. Retail shoe store owners, however, balked at selling

an unconventional ‘‘ugly’’ shoe. Undaunted, Fraser took Birkenstocks

to health fairs and found buyers among owners of health food stores

and alternative shops. Having carved out a niche by 1971, she

convinced the German parent company to give her sole United States

distribution rights and she incorporated the company. The most

recognizable and popular Birkenstock style, the Arizona, developed

for the American market, was introduced the same year.

By the late 1970s the shoes had become a favorite of hippies, the

back-to-the-earth crowd, and the health-conscious, especially women

looking for alternatives to the popular narrow-toed, high-heels gener-

ally available. Still, the shoes were anti-fashion—they were cited as a

fashion ‘‘don’t’’ in a women’s magazine in 1976. In 1979, the

Boston, a closed toe style, was introduced.

The company grew gradually until the late 1980s when it finally

got a foothold in the athletic/comfort shoe market. Americans’ desire

for more comfortable clothing and a nostalgia for the trappings of the

1970s, coupled with Birkenstock’s aggressive marketing, set off the

shoe’s phenomenal rise in popularity and sales in the 1990s. Counter-

ing a perceived association with Dead Heads, hippies, and grunge

rockers, Birkenstock catalogs featured hip young urbans. Between

1989 and 1992 the company expanded 500 percent and, according to

the New York Times, between 1992 and 1994 sold more shoes than it

had in the previous 20 years. The popularity bred knock-offs by high-

end shoemakers such as Rockport, Scholl, Ralph Lauren, and Reebok,

and discount copies appeared in stores such as Fayva and Kmart in the

1990s. In 1992, shoemakers Susan Bennis and Warren Edwards

created a formal imitation with rhinestone buckles for Marc Jacobs’

runway show. Competition from other ‘‘comfort shoe’’ companies

such as Teva and Naot began. Birkenstock eventually opened its own

stores and the shoes were made available in shops geared toward

comfortable footwear and through mail order giants such as L.L.

BIRTH OF A NATION ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

258

Bean; mainstream retailers like Macy’s and Nordstrom also began to

carry Birkenstocks.

Originally Fraser sold four styles, but by the early 1980s the

company offered over 20 different models with an expanded color

selection. The company also introduced a completely non-leather

shoe, the Alternative, for ethical vegetarians. Smaller sizes of the

classic styles, made to fit children, were offered around the same time.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the color selection moved out from

neutral and earthy tones like tan, black, white, brown, crimson, and

gold to include bright and neon colors like orange and turquoise.

During the same time, closed shoes made specifically for profession-

als who spend most of their workday on their feet, such as restaurant

and health care workers, showed up in shops and catalogs.

Birkenstocks, once the ugly duckling, moved to the center of

fashion. Vogue, GQ, Sassy, and Details magazines all featured sandal

and clog styles in fashion layouts throughout the 1990s. Birkenstocks

were seen on the feet of stars such as Madonna, Tanya Tucker,

Harrison Ford, Wesley Snipes, and Yvette Freeman; politicos Nor-

man Schwarzkopf, Donna Shalala, and John F. Kennedy Jr.; sports

greats Shaquille O’Neal, Dennis Rodman, and Dan O’Brien and the

maven of taste, Martha Stewart, among others. Menswear designer

John Scher had custom Birkenstocks made in gold leather, gray

corduroy, and wine pinstripe for his fall 1998 collection. Perry Ellis,

Sportmax, and Narcisco Rodriguez have also featured Birkenstocks

in their runway shows.

By the late 1990s Birkenstock had over 50 styles including

rubber clogs, trekking shoes, women’s wedge heels, multi-colored

sandals, anti-static models, as well as mainstays like the Zurich, a

style similar to the shoes Margot Fraser brought from Germany in

1966. Fraser is chief executive officer and 60 percent owner of the

Novato, California, based company, called Birkenstock Footprint

Sandals, Inc., with employees owning the balance. Fraser’s corpora-

tion has over 3,600 retail accounts, 125 licensed shops, and four

company-owned stores in the United States, including the San Fran-

cisco flagship store opened in 1997. Birkenstock’s sales for fiscal

1997 were an estimated $82 million.

—ViBrina Coronado

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Birkenstock Braces to Fight the Competition.’’ Personnel Journal.

August 1994, 68.

Brokaw, Leslie. ‘‘Feet Don’t Fail Me Now.’’ Inc. May 1994, 70.

McGarvey, Robert. ‘‘Q & A: Margot Fraser.’’ Entrepreneur. Febru-

ary 1995.

O’Keefe, Linda. Shoes: A Celebration of Pumps, Sandals, Slippers

and More. New York, Workman Publishing, 1996.

Patterson, Cecily. ‘‘From Woodstock to Wall Street.’’ Forbes. No-

vember 11, 1991, 214.

The Birth of a Nation

D. W. Griffith’s 1915 silent-film epic The Birth of a Nation

remained as controversial at the end of the twentieth century as at the

beginning, largely because of its sympathetic portrayal of the Ku

Klux Klan and of white ascendancy in the defeated South during the

Reconstruction period following the American Civil War. Galva-

nized by the film’s depiction of the newly freed slaves as brutal and

ignorant, civil-rights groups like the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) picketed the film in many

cities when it was released and protested again when the Library of

Congress added the classic to the National Film Registry in 1992

(though a year later the Library excluded the film from an exhibit of

54 early film works). Still, The Birth of a Nation is highly regarded as

a cinematographic triumph, a benchmark that helped define film

syntax for future directors in a newly emerging genre. The ambiguous

legacy of this film was capsulized by a New York Times reporter who

wrote (Apr. 27, 1994): ‘‘Like an orator who says all the wrong things

brilliantly . . . [it] manages to thrill and appall at the same time.’’ Few

of its most ardent critics deny credit to Griffith for having achieved a

work of technical brilliance. Film historian Lewis Jacobs argued in

The Rise of the American Film: A Critical History, that The Birth of a

Nation and Intolerance, a sequel, released by Griffith in 1916, are

‘‘high points in the history of the American movie’’ that ‘‘far

surpassed other native films in structure, imaginative power, and

depth of content . . . They foreshadowed the best that was to come in

cinema technique, earned for the screen its right to the status of an art,

and demonstrated with finality that the movie was one of the most

potent social agencies in America.’’

The iconic status of The Birth of a Nation is based on several

factors. It was heavily promoted and advertised nationwide, making it

the prototype of the modern ‘‘blockbuster.’’ In a nickelodeon era, it

was the first to break the $2-per-ticket barrier, proving that mass

audiences could be attracted to serious films that were more than

novelty entertainments or melodramas. It was the first film shown in

the White House, after which President Woodrow Wilson reputedly

said, ‘‘It is like writing history with lightning.’’ In addition to

establishing D. W. Griffith as America’s most important filmmaker,

The Birth of a Nation also helped to propel the career of Lillian Gish, a

21-year-old actress who, with her sister Dorothy, had appeared

in some of Griffith’s earlier films. Most importantly, it was a

groundbreaking production that set the standard for cinematography

and the basic syntax of feature films. Although, in the 1960s,

revisionist critics like Andrew Sarris speculated that Griffith’s techni-

cal sophistication had been overrated, The Birth of a Nation is still

revered for its pioneering use of creative camera angles and move-

ment to create a sense of dramatic intensity, and the innovative use of

closeups, transitions, and panoramic shots, ‘‘all fused by brilliant

cutting,’’ in the words of Lewis Jacobs. Even the protests engendered

by the film helped Americans find their bearings in the first signifi-

cant cultural wars involving artistic creativity, censorship, and identi-

ty politics in the age of the new mass media.

The Birth of a Nation was based on Thomas Dixon, Jr.,’s 1905

drama The Clansman, which had already been adapted into a popular

play that had toured American theaters. Screenwriter Frank Woods,

who had prepared the scenario for Kinemacolor’s earlier, abortive

attempt to bring Dixon’s work to the screen, convinced Griffith to

take on the project. ‘‘I hoped at once it could be done,’’ Griffith said,

‘‘for the story of the South had been absorbed into the very fiber of my

being.’’ Griffith also added material from The Leopard’s Spots,

another of Dixon’s books that painted a negative picture of Southern

blacks during the Reconstruction era. In a 1969 memoir, Lillian Gish

recalled that Griffith had optioned The Clansman for $2500 and

offered the author a 25 percent interest in the picture, which made

Dixon a multimillionaire. She quoted Griffith as telling the cast that

‘‘I’m going to use [The Clansman] to tell the truth about the War