Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BETTY BOOPENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

239

Americans in the later 1800s to create traditions for civility, taste, and

permanence—literally, to construct cultural ideals. One of the earliest

‘‘taste makers,’’ Andrew Jackson Downing, introduced many Ameri-

cans to landscape architecture and gardening through his writings.

The periodical that he edited, The Horticulturalist, helped to initiate

an American tradition of popular magazines and journals helping to

perfect designs of the prototypical American home.

Similarly, an entire genre of magazines would appeal directly to

women of privilege, most of whom were not employed. From 1840

through the end of the nineteenth century, Godey’s Lady’s Book

defined the habits, ideals, and aspirations of many Victorian women.

Such general interest magazines helped to define the era, but had

more to do with constructing femininity than with the American

home. Magazines such as Better Homes and Gardens helped to merge

the women’s magazine with practical publications specifically con-

cerned with home design. This bond, of course, would shape the role

of the modern ‘‘housewife’’ into that of the domestic manager. The

ideal that emerges from this union is referred to by many scholars as

the ‘‘Cult of Domesticity,’’ which helps make BH&G one of the most

popular magazines in America throughout the twentieth century.

BH&G helped define a national dialogue on home life through a

combination of informative articles, basic cooking techniques, and

contests that helped to rally the interest of readers. The first home plan

design contest was first published in 1923 and, most importantly, the

‘‘Cook’s Round Table’’ that began in 1926 would become the

longest-running reader-driven contest in publishing history. This

would later become part of BH&G’s test kitchen and what became

known as ‘‘Prize Tested Recipes.’’ BH&G experimentation is attrib-

uted with introducing the American palate to tossed salad (1938) and

barbecue cooking (1941) among many innovations. Published through-

out World War II, the magazine even altered its recipes to cope with

shortages of eggs, butter, and other foods.

These contests and recipes, however, were only a portion of the

new domestic stress that BH&G fostered in the American public. The

ideal of home ownership that can be found in the ideas of Thomas

Jefferson and others began in the pages of the magazine in 1932 with

the introduction of the BH&G building plan service. The marketing of

building plans had taken place since the late 1800s; however, BH&G’s

service grew out of new governmental initiatives. Following data that

revealed that only 46 percent of Americans owned homes in the

1920s, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover’s ‘‘Own Your Home’’

campaign combined with efforts by the Bureau of Standards to

stimulate home building while also modernizing American building

practices. Better Homes in America, Inc. fulfilled Hoover’s goal of

voluntary cooperation between government and private enterprise for

the public good. Formed in 1922, the organization soon had branches

in over 500 communities.

Such groups worked with BH&G to permanently alter American

ideas of domesticity. By 1930 there were 7,279 Better Homes

committees across the country. During national Better Homes Week

(usually the last week in April), each local committee sponsored

home-improvement contests, prizes for the most convenient kitchen,

demonstrations of construction and remodeling techniques, and lec-

tures on how good homes build character. The demonstration house

was the highlight of the week. Most communities built a single model

residence, with donated materials and labor. Obviously, a national

institution had been created and the private sector, through Better

Homes and Gardens, would be responsible for perpetuating the jump

start that the federal government had offered to systematizing and

organizing American home design and construction.

BH&G and the Better Homes movement in general provided the

essential conduit through which the dynamic changes in building

could be channeled. While much of this movement was intended for

the homeowner who was building his own house, the organization

would also be instrumental in the evolving business organization of

home development. Specifically, land developers who were con-

structing vast housing tracts would work with Better Homes to

establish the guidelines that would form the standard suburban home.

Each constituency had a stake in establishing ‘‘Safe Guards Against

Incongruity.’’ At times the Better Homes forum would also be

complicit in discussing the social organization of the evolving hous-

ing development, which would often restrict race and ethnicity

through restrictive covenants and deed restrictions. BH&G would not

be complicit in such restrictions, however, it would become active in

the sales end of housing. After first considering a line of related

restaurants, hotels, and insurance companies in 1965, Meredith

launched Better Homes and Gardens Real Estate Service in 1975. It

has grown to be one of the nation’s largest real estate services.

In order to make certain of this continued popularity, the

magazine’s logo was lent to popular instructional books for many

home improvement tasks as well as to cookbooks as early as 1930.

This, however, was only the beginning of the better home informa-

tional empire: by the late 1990s a television network and many hours

of programming and videos would offer techniques and pointers on

home design, repair, as well as on cooking and personal relations. The

magazine’s involvement in homemaking reminds one of aggressive,

corporate expansion that attempts to dominate every facet of an

endeavor. In this case, homemaking truly has become an industry of

such massive scale and scope. BH&G continued to influence Ameri-

can home life from finding a home, redecorating it, maintaining it,

and, finally, to selling it at the end of the twentieth century.

—Brian Black

F

URTHER READING:

Hayden, Dolores. Redesigning the American Dream: The Future of

Housing, Work, and Family Life. New York, W.W. Norton, 1984.

Schuyler, David. Apostle of Taste: Andrew Jackson Downing, 1815-

1852. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream: A Social History of Hous-

ing in America. Cambridge, MIT Press, 1992.

Betty Boop

Betty Boop, the first major female animated screen star, epito-

mized the irresistible flapper in a series of more than one hundred

highly successful cartoons in the 1930s. From her debut as a minor

character in the 1930 Talkartoons short feature ‘‘Dizzy Dishes,’’ she

quickly became the most popular character created for the Fleischer

Studio, a serious animation rival to Walt Disney. Unlike Disney’s

Silly Symphonies, which emphasized fine, life-like drawings and

innocent themes, the Fleischer films featuring Betty Boop were

characterized by their loose, metamorphic style and more adult

situations designed to appeal to the grown members of the movie-

going audience. According to animation historian Charles Solomon,

Betty Boop ‘‘was the archetypal flapper, the speakeasy Girl Scout

BETTY BOOP ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

240

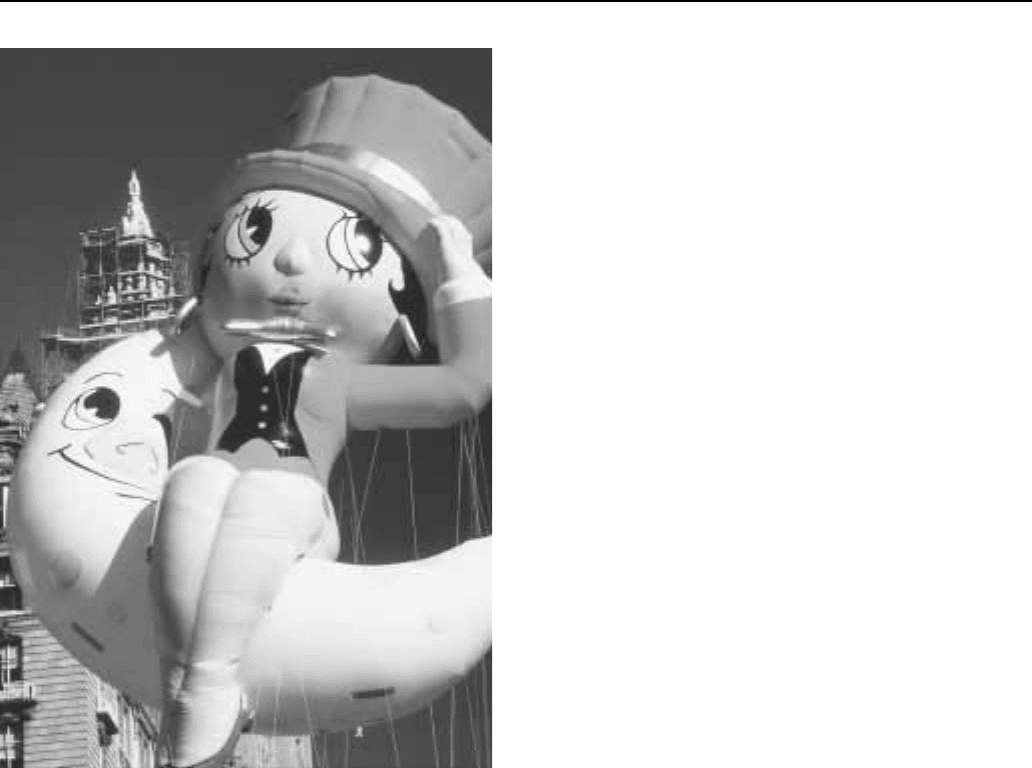

Betty Boop’s depiction in balloon form in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day

Parade in New York City.

with a heart of gold—already something of an anachronism in 1930.’’

Although her appearance rooted her to the Jazz Age, Betty Boop’s

popularity remained high throughout the decade of the Great Depres-

sion, as she was animation’s first fully developed and liberated

female character.

For a character that would come to personify overt female

sexuality, the original version of Betty Boop created by animator

Grim Natwick was a somewhat grotesque amalgamation of human

and dog features. In her first screen appearance she was cast as a

nightclub singer attempting to win the affection of then-Fleischer star,

Bimbo, an anthropomorphized dog. Subsequent appearances reveal

her gradual evolution into a fully human form. Her ‘‘French doll’’

figure was modeled after Mae West’s, and she featured a distinctive

spit curl hairdo and a singing style inspired by popular chanteuse

Helen Kane (‘‘the Boop Boop a-Doop Girl’’). Miss Kane, however,

was outraged by the animated character and claimed in a 1934 lawsuit

that the Fleischers had limited her earning potential by stealing her

distinctive singing style. Although Betty Boop certainly is a carica-

ture of Kane, the singer lost in her claim against the Fleischers after it

was proven that a black entertainer named Baby Esther had first

popularized the phrase ‘‘boop-oop-a-doop’’ years earlier. Actress

Mae Questel provided Betty’s high-pitched New York twang for all

of the character’s screen appearances, beginning in 1931.

Betty’s growing popularity prompted the Fleischers to promote

their new female sensation to main character status and relegate the

formerly top-billed Bimbo to the supporting role of Betty’s constant

admirer. Betty’s femininity was repeatedly highlighted throughout

her cartoon adventures, as her legs, busty frame, and frilly undies

were displayed for the audience. Her personality was that of an

innocent vamp who was not above lifting her skirt, standing in

provocative poses, and batting her long eyelashes to achieve her

goals. The series was also filled with humorous double entendres for

adults that would generally pass over the heads of Betty’s younger

fans. For all the sexual antics, however, Betty often displayed proto-

feminist qualities. She was generally portrayed as a career girl, who

had to fight off the advances of lecherous male characters. The issue

of sexual harassment in the workplace is most strongly presented in

1932’s ‘‘Boop-Oop-A-Doop,’’ where she confronts a lewd ringmas-

ter who demands her affection so that she may return to her job at a

circus. By the cartoon’s end she firmly proclaims, ‘‘He couldn’t take

my boop-oop-a-doop away!’’ The Fleischers even had Betty enter the

male-dominated world of politics in Betty Boop for President (1932).

One of the most popular features of the Betty Boop cartoon

series were her encounters with many of the most popular entertain-

ment figures of the 1930s. At various times Cab Calloway, Lillian

Roth, Ethel Merman, and Rudy Vallee all found themselves singing

and dancing with the cartoon star. These appearances were designed

to promote the recordings of the stars on the Paramount label, which

also distributed the Betty Boop series. To further capitalize on the

animated star’s success, Betty Boop soon appeared on hundreds of

products and toys. In 1935 King Features syndicated Betty Boop as a

Sunday comic strip, which toned down the character’s sexuality.

Betty Boop remained a popular character until the mid-1930s,

when she fell victim to Will Hays and the Hollywood Production

Code. The censor demanded Betty no longer be presented in her

trademark short skirts and low tops. There were even claims that her

‘‘romantic relationship’’ with the dog Bimbo was immoral. The

Fleischers responded by placing Betty in a more domestic setting and

surrounding her with a more wholesome cast, including an eccentric

inventor named Grampy and a little puppy called Pudgy. In several of

these later cartoons Pudgy, not Betty, is the primary character.

Ironically, a dog character reduced Betty’s role in the same manner

she had replaced Bimbo years earlier. The final Betty Boop cartoon,

Yip, Yip, Yippy!, appeared in 1939. However, Betty’s racy flapper

persona had vanished sometime earlier and had been replaced by a

long-skirted homemaker.

Betty Boop sat dormant until the mid-1970s when her cartoons

began playing on television and in revival houses. Her increased

visibility led to a resurgence of Betty merchandise in the 1980s and

1990s. In 1988, Betty made a brief appearance in the feature film Who

Framed Roger Rabbit?, where she complained of her lack of acting

jobs since cartoons went to color. Today, Betty Boop, remains a

potent symbol of the Jazz Age and is considered a pioneer achieve-

ment in the development of female animated characters.

—Charles Coletta

F

URTHER READING:

Callan, Kathleen. Betty Boop: Queen of Cartoons. New York, A&E

Television Networks, 1995.

Solomon, Charles. The History of Animation. New York, Knopf, 1989.

BEVERLY HILLBILLIESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

241

Betty Crocker

Betty Crocker, an invented identity whose face adorns the

packaging of more than 200 food products manufactured by General

Mills, is one of the most recognized icons in American brand-name

marketing. Together with the trademarked red spoon logo, the Betty

Crocker brand name is found on many cake mixes and dessert

products, main courses like Hamburger Helper and scalloped pota-

toes, and snacks like microwave popcorn and chewy fruit items. The

Betty Crocker brand name accounts for over $1.5 billion each year,

which is nearly thirty percent of annual sales for General Mills.

The name originated in 1921 when Washburn Crosby Company,

as General Mills was then known, sponsored a jigsaw-puzzle contest

and found that the entrants, mostly women, wanted more information

about baking. The two most significant factors behind the creation of

the Betty Crocker name, according to a General Mills document,

‘‘were the philosophy and doctrine of sincere, helpful, home service

and the belief that the company’s Home Service contract with

homemakers should be personalized and feminized.’’

The choice of ‘‘Betty Crocker’’ as a name for General Mills

Home Services Activities is attributable to then advertising manager,

James A. Quint. ‘‘Betty’’ was considered a friendly nickname while

‘‘Crocker’’ was used as a tribute to retired company director and

secretary, William Crocker. The name suggests a particular lifestyle

involving a woman who is a traditional, suburban, all-American

mother and who takes special care in her cooking and of her family.

Although the face was altered slightly over the years from a more

matronly to a younger image, the familiar face still reinforces a strong

visual image over several generations. To many, Betty Crocker

reminds them of childhood memories of Mom baking in the kitchen

or an idealized childhood including that nurturing image.

Betty Crocker has over the years created a trustworthy reputation

as the First Lady of Food. She receives millions of letters and phone

calls and is listed as the author of several bestselling cook books. Her

weekly advice column appears in more than 700 newspapers through-

out the United States, and in the 1990s she acquired her own website,

which includes recipes from ingredients provided by users as well as

personalized weekly menu plans and household tips.

The Betty Crocker name has been affiliated with food products

since 1947. Her pioneering cake mix was called Ginger Cake, which

has now evolved into Gingerbread Cake and Cookie Mix. Since then,

the name has been licensed to several types of food products as well as

to a line of cooking utensils, small appliances, and kitchen clocks. In

the 1990s, General Mills leveraged this brand in the cereal market by

introducing Betty Crocker Cinnamon Streusel and Dutch Apple

cereals, with packaging primarily designed to attract dessert lovers.

Even as Betty Crocker strides into the new millennium, she

continues to leverage her past history by successfully practicing the

art of retro-marketing. Betty’s Baby Boomer constituents have lately

inquired about ‘‘nostalgia foods’’ such as ‘‘Snickerdoodles,’’ ‘‘Pink

Azalea cake,’’ and ‘‘Chicken A la King,’’ to name a few. In 1998,

General Mills published a facsimile edition of the original Betty

Crocker’s Picture Cook Book, first published in 1950.

—Abhijit Roy

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Betty Crocker.’’ http:www/betty-crocker.com. May 1999.

Salter, Susan. ‘‘Betty Crocker.’’ In Encyclopedia of Consumer Brands,

Volume 1. Detroit, St. James Press, 1998.

Shapiro, Laura. ‘‘Betty Goes Back to the Future.’’ Newsweek, Octo-

ber 19, 1998.

Beulah

The first television network series to star an African American,

Beulah ran on ABC from October 3, 1950 until September 22, 1953.

The comic black maid had her beginnings on the 1940s radio series

Fibber McGee and Molly where she was originally played by a white

male actor. The African American Oscar winner, Hattie McDaniel,

took over the role when Beulah was spun off onto her own radio show.

The popular series then moved to the fledgling television medium

with a new black actress playing Beulah, the noted singer, stage, and

screen performer Ethel Waters. Waters left the series after two years

and was briefly replaced by McDaniel. Illness forced her to leave the

series, and another black actress famous for playing maids, Louise

Beavers, took the role in the show’s last season. The series followed

the gently comic adventures of Beulah, her marriage-resistant male

friend, Bill, the Henderson family whom Beulah served, and Beulah’s

feather-brained friend, also a black maid, Oriole (played first by

Butterfly McQueen, then Ruby Dandridge). Debuting a year before

the more famous black comedy Amos ’n’ Andy, Beulah did not

generate the other series’ enormous controversy, despite the stereo-

typed representations of black servants whose lives revolve around

their white superiors. In 1951, however, when the NAACP (National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People) launched a

highly publicized protest against the Amos ’n’ Andy television show,

the civil rights lobby group included Beulah in its condemnation. The

series left the air the same time as Amos ’n’ Andy.

—Aniko Bodroghkozy

The Beverly Hillbillies

One of the most durable television sitcoms and one of the most

successful of the popular rural comedies at CBS during the 1960s, The

Beverly Hillbillies (1962-71) has withstood critical disdain and

become a favorite with viewers in reruns. The Beverly Hillbillies is

the old story of city slicker versus country bumpkin, of education

versus wisdom; and though the laughs are at the Hillbillies’ expense,

in the end they almost always come out on top despite their lack of

sophistication. This simple account of simple country folk at odds

with city folk hit a nerve in the country and was reflected in a number

of other shows of the era, including fellow Paul Henning productions

Petticoat Junction and Green Acres. The Beverly Hillbillies pre-

miered to a critical blasting and yet within a few weeks was at the top

of the ratings and remained popular for the length of its run.

In the theme song we learn the story of Jed Clampett (Buddy

Ebsen), a mountain widower. One day, while hunting for food, Jed

comes across some ‘‘bubbling crude’’ on his land: ‘‘Oil, that is, black

gold, Texas tea.’’ Jed sells the rights to his oil to the OK Oil Company

BEVERLY HILLS 90210 ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

242

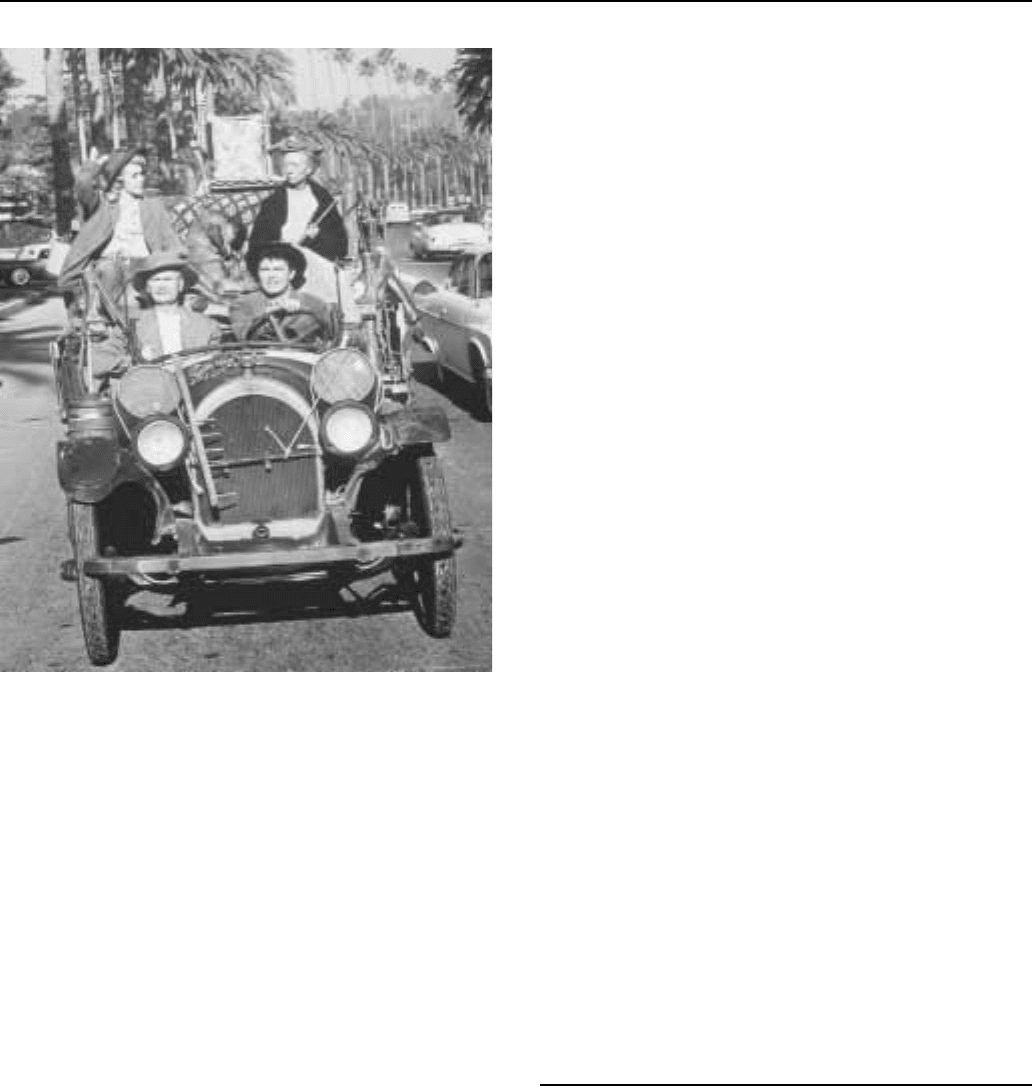

The Beverly Hillbillies (clockwise from bottom left): Buddy Ebsen, Donna

Douglas, Irene Ryan, and Max Baer, Jr.

and becomes a millionaire. He is advised to move from the hills and

go to California. Along with him he takes his mother-in-law, Granny

(Irene Ryan); his daughter, Elly May (Donna Douglas); and his

nephew, Jethro Bodine (Max Baer, Jr.). In California Jed’s money is

kept at the Commerce Bank, and along with the bank comes its

president, Milburne Drysdale (Raymond Bailey), and his plain but

smart assistant, Jane Hathaway (Nancy Kulp). Most of the interac-

tions involve the Clampetts and the Drysdale/Hathaway team and

occasionally Drysdale’s snobby wife.

To keep a closer eye on his largest depositor, Drysdale arranges

for the Clampetts to move into the mansion next to his house in

Beverly Hills. Drysdale is obsessed with the fear that the family will

move back to the hills along with their money, and he will do

practically anything to assuage them and help them feel comfortable

in their new home. This simple premise remains essentially un-

changed through the bulk of the show’s run. City life is not difficult

for the rube man-child Jethro, who fancies himself a playboy or secret

agent or movie producer and wants to keep his ‘‘hick’’ family from

making him look bad. Elly May is the pretty tomboy who seems

content to live in the city as long as she has her ‘‘critters.’’ But crusty

old Granny is not happy here, where she has lost her stature in society

and she can no longer be the doctor, matchmaker, and keeper of

wisdom. Most of the characters in The Beverly Hillbillies are carica-

tures and stereotypes of rich and poor. The only real exception is Jed

Clampett, who alone seems to appreciate both sides.

The humor in this show comes from many sources. Initially, the

jokes and obvious humor come at the expense of the Hillbillies. The

ragged clothes, the fascination with even the most ordinary aspects of

everyday life (they assume the billiard table is for formal dining and

that the cues are for reaching across the table), and odd customs and

ideas about high society based on silent movies that reached their

hometown. But just as funny are the city folk, like Mr. Drysdale and

his transparent efforts to get them to stay, or Miss Jane and her proper

and humorous look. The Beverly Hillbillies is at its best in showing

how foolish modern-day life looks through the eyes of the transplant-

ed country folk. Jed is the center and the speaker, pointing out those

things that seem to not make sense, and upon reflection we can often

agree. While this show is no work of high art or philosophy, and the

story lines and situations are often ludicrous and sometimes down-

right foolish, it does an excellent job of entertaining with a basic

backdrop and characters for thirty minutes. In the weeks following the

assassination of President Kennedy, this show had four of its highest

rated shows, and some of the highest rated shows of all time. It is

likely not a coincidence that people would turn to a simple comedy in

a time of crisis.

The Beverly Hillbillies was finally dropped in 1971 as part of the

deruralification at CBS. Several members returned in the 1980s for a

reunion television movie, and in the 1990s, this was one of many old

television shows to be made into a theatrical movie with an all-new

cast reprising the old familiar roles. Hipper, more urban, with less

focus on caricature, we see an updating of the premise again in the

early 1990s on the hit show The Fresh Prince of Bel Air—this time

with a nephew from the ghetto streets of the east sent to live in the sun

and opulence of Bel Air and again pointing out the foolishness of the

so-called better life.

—Frank Clark

F

URTHER READING:

Castleman, Harry, and Walter J. Podrazik. Harry and Wally’s Favor-

ite Shows: A Fact-Filled Opinionated Guide to the Best and Worst

on TV. New York, Prentice Hall Press, 1989.

Ebsen, Buddy. The Other Side of Oz. Newport Beach, Calif., Donavan

Publishing, 1993.

McNeal, Alex. Total Television: A Comprehensive Guide to Pro-

gramming from 1948 to the Present. New York, Penguin

Books, 1991.

Putterman, Barry. On Television and Comedy: Essays on Style,

Theme, Performer and Writer. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFar-

land, 1995.

Beverly Hills 90210

Premiering in October 1990, television teen drama Beverly Hills

90210 became a cultural phenomenon, both in the United States and

abroad, and was the precursor to the deluge of teen-based dramas that

were to dominate prime-time television in the late 1990s. The show

helped to establish the new Fox Television Network, and was the first

network to challenge the traditional big three—ABC, CBS, and

NBC—for the youth audience.

The title of the program refers to the location of its setting, the

posh city of Beverly Hills, California (zip code 90210). Produced by

Aaron Spelling, the program focused on a group of high school

students. The ensemble cast, featured Jason Priestly (twice nominated

for a Golden Globe for Best Actor in a TV Series—Drama in 1993 and

BEWITCHEDENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

243

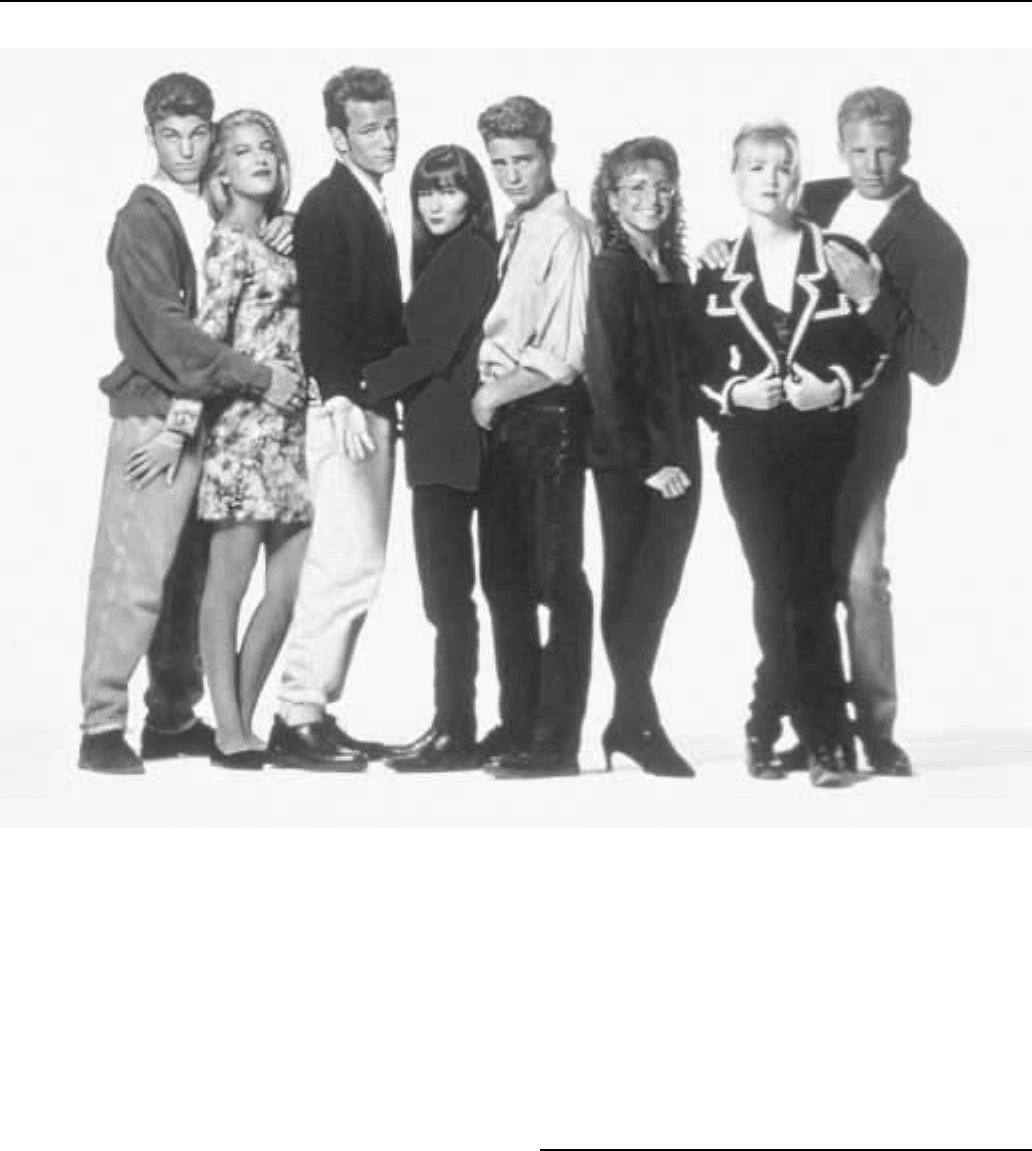

The cast of Beverly Hills 90210.

1995), Shannon Doherty, Jennie Garth, Luke Perry, Tori Spelling, Ian

Ziering, and Gabrielle Carteris. They were catapulted into the realm

of teen idols (despite the fact that most were in their twenties), and

their images graced publications and commercial products. Because

of the setting, the program presented glamorous lifestyles and paid

great attention to fashion, an aspect which was not lost on its

audience, who followed clothing, music, and hairstyle trends.

Much of the show’s appeal has been attributed to the story lines,

which presented issues and concerns relevant to its teenage audience:

parental divorce, eating disorders, learning disabilities, sexuality,

substance abuse, and date rape. As the actors aged, so did their

characters, and by the sixth season several were attending the ficti-

tious California University, encountering more adult problems and

issues. Although the show was praised for tackling such important,

and often controversial, teen issues in a serious manner, many found

the program problematic because it upheld narrowly defined concepts

of physical beauty, presented a luxurious world of upper-class materi-

alism, rarely included people of color, and constructed the problems

presented in unrealistic terms.

—Frances Gateward

F

URTHER READING:

McKinley, E. Graham. Beverly Hills 90210: Television, Gender, and

Identity. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, 1997.

Simonetti, Marie-Claire. ‘‘Teenage Truths and Tribulations across

Cultures: Degrassi Junior High and Beverly Hills 90210.’’ Jour-

nal of Popular Film and Television. Vol. 22, Spring 1994, 38-42.

Bewitched

In this innovative and immensely popular sitcom—it ranked in

TV’s top twenty-five all but two of its eight years on the air and was

nominated for twenty-two Emmy awards—suburbia meets the super-

natural in the guise of Samantha, television’s most loveable witch.

Played by the talented and genial Elizabeth Montgomery, Samantha

is the all-American wife of Darrin Stephens, a hapless advertising

executive who asks his wife to curb her witchery in the interest of

having a normal life together. Originally broadcast from 1964 to

1972, on the surface Bewitched seemed like simply another suburban

BEWITCHED ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

244

The stars of Bewitched, (l-r) Elizabeth Montgomery, Dick Sargent, and Agnes Moorehead.

sitcom, but in fact it captured the mood of the nation in dealing with a

‘‘mixed marriage’’ between a witch and a mortal, as well as the

difficulties faced by a strong woman forced to subdue her powers for

the sake of her marriage. A quarter of a century later, Bewitched

remains a pop culture favorite, a nostalgic take on the 1960s that has

remained surprisingly hip.

Bewitched was borne of the marriage of actress Elizabeth

Montgomery and award-winning television director William Asher.

The couple met and fell in love in 1963, when Elizabeth starred in

Asher’s film, Johnny Cool, and they were married shortly thereafter.

Suddenly, Montgomery—an Emmy nominee and a veteran of more

than 200 television programs—began talking about retiring in order

to raise a family. But Asher felt his wife was too talented to bow out of

show business and suggested that they work together on a television

series. When Elizabeth enthusiastically agreed, their search for the

right property began.

Asher, an Emmy-award-winning director of I Love Lucy, forged

an agreement with ABC, who forwarded him a script which had been

written for Tammy Grimes. The Witch of Westport took as its premise

a marriage between a witch and a mortal. Asher and Montgomery

both liked the script and, with Grimes committed to a Broadway play,

the couple worked to transform the series into a show suited to

Montgomery’s talents and sensibilities, by increasing the comedic

elements and losing a lot of what they felt was stereotypical witchery

and hocus pocus.

The Ashers shot the pilot for their new series, which they called

Bewitched, in November, 1963. But when ABC saw the show, the

network feared that in airing a show about the supernatural they risked

losing both their sponsors and their audiences in the Bible Belt. But

after Asher personally flew to Detroit to secure Chevrolet’s backing,

ABC greenlighted Bewitched for their 1964 fall lineup.

From the start, Bewitched was a huge hit, climbing to number

two in the ratings in its very first season. Much of the show’s success

was due to the superb ensemble cast of top-notch actors delivering

superb comic acting. With Elizabeth Montgomery as Samantha, Dick

York (later Dick Sargent) as Darrin, and veteran actress Agnes

Moorehead as Samantha’s meddling mother, Endora, at its core, the

cast also featured David White as Darrin’s troublesome boss, Larry

Tate; George Tobias and Alice Pearce (later Sandra Gould) as the

nosy-next-door-neighbor Kravitzes; the inimitable Paul Lynde as

Uncle Arthur; the hysterical Marian Lorne as bumbling Aunt Clara;

and the great English actor, Maurice Evans, as Samantha’s father.

As Herbie J. Pilato writes in The Bewitched Book, ‘‘Each

episode . . . is a new misadventure as Sam (as she’s affectionately

known to Darrin) tries to adapt her unique ways to the life of the

average suburban woman. Learning to live with witchcraft is one

BICYCLINGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

245

thing, but Endora’s petulant dislike of her son-in-law (due to his

eagerness to succeed without witchcraft) is the story conflict that

carried the sitcom through its extensive run. This dissension, coupled

with the fact that Samantha and Darrin love each other in spite of their

differences, is the core of the show’s appeal.’’

Unquestionably, the star of the show was Elizabeth Montgom-

ery, a gifted actress whose dramatic and comedic acting abilities

made her immensely attractive to TV audiences of both sexes and all

ages. The daughter of movie star Robert Montgomery, Elizabeth had

been a professional actress since her teens, with many credits to her

name. But Bewitched made her both a television star and a pop culture

icon. Capitalizing on his wife’s unconscious habit of twitching her

upper lip, William Asher created a magical nose twitch by which

Samantha, with a mischievous glint in her eye, cast her spells. Though

fans loved the show’s magic, Samantha’s supernatural powers were

never overused. As Montgomery herself would later remark, ‘‘If you

have a weapon, be it a gun, witchcraft, or sharp-tongued wit, you

recognize it as something you rely on. But your principles are such

that you do not pull out the big guns unless you really have to. There’s

a certain dignity to Samantha’s decision to hold back on her pow-

er.... It had to do with Samantha’s promise to herself and to Darrin

of not using witchcraft . . . her own self-expectations and living up

to them.’’

Audiences quickly came to adore Samantha and to eagerly await

the use of her powers. And they identified with the character, seeing

her as an outsider in mainstream society, trying to do her best to fit in.

The appeal of Montgomery, as a beautiful and talented woman who

wasn’t afraid to be funny, carried the show, and Montgomery attract-

ed a large and loyal fan following.

Although most episodes centered around the Stephens’ house-

hold and Darrin’s advertising office, among the most popular shows

were those featuring magical incarnations in the form of animals or

famous people from history, such as Leonardo da Vinci or Julius

Caesar. Other popular episodes included Darrin and Samantha’s baby

daughter, Tabitha, a little witch played by twins Erin and Diane Murphy.

A television fixture throughout the Sixties, Bewitched finally

dropped out of TV’s top twenty-five in 1970 when Dick York left the

show, forced into early retirement because of a chronic back injury.

Although the chemistry between Montgomery and York’s replace-

ment, Dick Sargent, was superb, audiences didn’t warm to the casting

change. As more cutting-edge sitcoms like All in the Family hit the

airwaves in the early 1970s, Bewitched no longer seemed so innova-

tive, and Montgomery decided to call it quits.

Although Bewitched went off the air in 1972, it soon found its

way into syndication, where it became a perennial favorite, until

moving to the immensely popular Nick at Nite cable lineup, where it

is a permanent feature of their prime-time lineup. Now, more than

twenty-five years since the last episode was filmed, Bewitched

continues to enchant audiences with its winning blend of award-

winning sitcom humor and its wry look at suburban American culture.

—Victoria Price

F

URTHER READING:

Pilato, Herbie J. The Bewitched Book: The Cosmic Companion to

TV’s Most Magical Supernatural Situation Comedy. New York,

Delta, 1992.

BH&G

See Better Homes and Gardens

Bicycling

Although most Americans in the twentieth century associate

bicycles and bicycling with children, Europeans, or fitness buffs, a

bicycle craze among adults swept the United States in the late 1880s

and 1890s that stimulated much excitement and new ways of thinking

about transportation. Capitalists created a thriving and valuable

bicycle manufacturing industry and a well-developed trade press, as

leaders of substantial influence emerged and the industry made rapid

advances in design and technology. Major pioneers in aviation (the

Wright brothers) and the automobile industry (Henry Ford) got their

start as bicycle designers and mechanics, applying their expertise to

new motorized forms of transportation.

The early industry gained its footing in the late 1870s when

Colonel Albert Pope, a successful Boston industrialist, converted an

old sewing machine factory into a bicycle plant. Pope set about

building an empire, hiring skilled machinists and die makers to craft

interchangeable parts, enabling him to make his high-wheel bicycles

for a mass market. Pope also founded the leading bicycle publication,

Outing, in 1882. The industry became embroiled in a series of bitter

legal battles over patent rights in the mid-1880s, but in 1886 every-

thing changed with a major innovation in bicycle design from Europe:

the ‘‘safety’’ bicycle. The new style introduced chain-driven gearing,

allowing inventors to replace the dangerous high-wheel design with

two equally sized wheels and the now-standard diamond frame.

These changes significantly increased the safety of bicycles without

sacrificing speed, thus creating a much larger market for bicycles.

After 1886 prices fell, democratizing what had once been an elite

sport. Bicycle clubs sprouted, and the nation developed bicycle fever.

Sales soared as comfort and speed improved, reaching a peak in 1897

when about three thousand American manufacturers sold an estimat-

ed two million bicycles.

The popularity of bicycles in the 1890s engendered heated

debates over the decency of the fashionable machines. Advocates

catalogued their benefits: economic growth, the freedom of the open

road, a push for improved roads, increased contact with the outdoors,

and the leveling influence of providing cheap transportation for the

workingman. Critics, however, attacked bicycles as dangerous (be-

cause they upset horses), detrimental to the nervous system (because

riding required concentration), and antithetical to religion (because so

many people rode on Sundays). In addition, many critics questioned

the propriety of women riding bicycles. Particularly scandalous to the

skeptics was the tendency of women cyclists to discard their corsets

and don bloomers in place of long skirts, but censors also reprimand-

ed courting couples for using bicycles to get away from parental

supervision and criticized women’s rights advocates for emphasizing

the emancipatory qualities of their machines.

By the turn of the century the bicycle craze abated and, despite

an urban indoor track racing subculture that persisted until World War

II using European imports, bicycles survived for a number of decades

primarily as children’s toys. The quality of bicycles, which found

their major retail outlets between 1900 and 1930 in department stores,

deteriorated substantially. Then, in 1931, the Schwinn bicycle com-

pany sparked a minor revolution in the industry by introducing the

balloon tire, an innovation from motorcycle technology that replaced

BIG APPLE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

246

one-piece inflatable tires with an outside tire coupled with a separate

inner tube. The strength and comfort of these new tires could

accommodate much heavier, sturdier frames, which could better

withstand the use (and abuse) of children riders. Taking a cue from the

1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, a showcase for Art

Deco styling, Schwinn inspired more than a decade of streamlined

bicycles—and innumerable suburban childhood dreams of freedom

and exhilaration—with its 1934 Aerocycle. Bicycle design changed

again slightly in the mid-1940s when manufacturers began to capital-

ize on the baby boom market. Following the practice of the automo-

bile industry, bicycle designers created their own version of planned

obsolescence by styling bicycles differently to appeal to different

age groups.

Beginning in the mid-1950s and early 1960s, bicycles again

became popular among adults, this time as a healthy form of exercise

and recreation. A turning point came in September of 1955, when

President Dwight Eisenhower suffered a heart attack. His personal

physician, Dr. Paul Dudley White, happened to be an avid cyclist who

believed that bicycling provided significant cardiovascular benefits.

When he prescribed an exercise regimen featuring a stationary

bicycle for the president, the ensuing publicity generated a real, if

small, increase in bicycling among adults. Small local racing clubs in

California kept the idea of cycling as adult recreation alive through

the 1950s, but not until the exercise chic of the 1960s spread from the

West Coast to other parts of the country did adult bicycles become a

significant proportion of all sales. Bicycle manufacturers responded

by introducing European-style ten-speed gearing, focusing on racing,

touring, and fitness in their marketing. The popularity of bicycling

made modest gains through the 1970s and 1980s as racing and touring

clubs gained membership and local bicycle competitions became

more common around the country, including races called triathlons

that mixed running, bicycling, and swimming.

Beginning in the early 1980s, a new breed of bicycles called

‘‘mountain bikes’’—sturdy bicycles designed with fat, knobby tires

and greater ground clearance for off-road riding—overtook the adult

market with astonishing rapidity. The new breed of bicycles first

reached a mass market in 1981, and by 1993 sales approached 8.5

million bicycles, capturing the large majority of the United States

market. Earning substantial profits from booming sales, designers

made rapid improvements in frame design and components that made

new bicycles appreciably lighter and more reliable than older designs.

Off-road races grew in number to rival the popularity of road racing,

and professional races gained corporate sponsorship through the

1980s and 1990s. Somewhat ironically, however, only a small per-

centage of mountain bike owners take their bicycles off-road. Buyers

seem to prefer their more comfortable, upright style compared to road

racing machines, but use them almost exclusively on paved roads for

exercise and eco-friendly short-distance transportation.

—Christopher W. Wells

F

URTHER READING:

Pridmore, Jay, and Jim Hurd. The American Bicycle. Osceola, Wis-

consin, Motorbooks International Publishers, 1995.

Smith, Robert A. A Social History of the Bicycle: Its Early Life and

Times in America. New York, American Heritage Press, 1972.

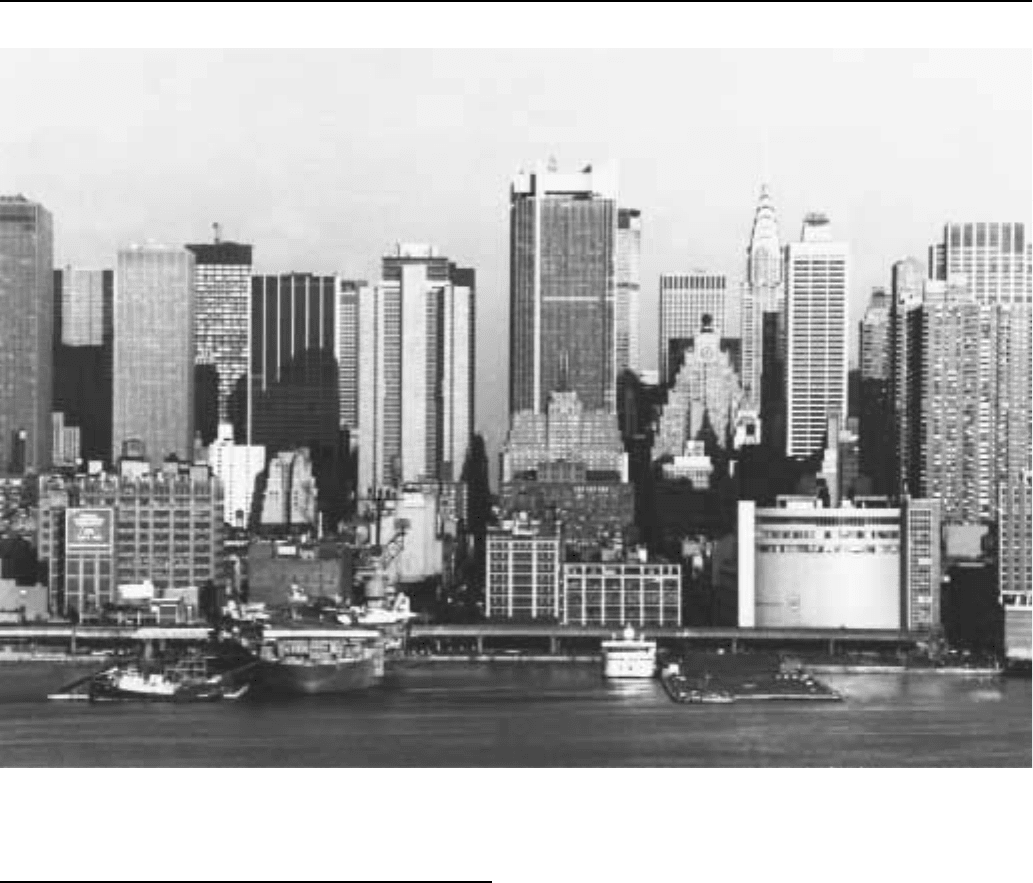

The Big Apple

Among the great cities in the world—Paris, Chicago, or New

Orleans, for example—none is better known by its nickname than

New York City, ‘‘The Big Apple.’’ Paris may be ‘‘The City of

Lights,’’ Chicago ‘‘The Windy City,’’ and New Orleans ‘‘The Big

Easy,’’ but just mention ‘‘The Big Apple’’ and America’s metropolis

immediately comes to mind. New York is the nation’s financial

center, an entertainment, theater, and news capital, and the heart of the

fashion and publishing industries. ‘‘The Big Apple,’’ meaning the

biggest, best, and brightest, seems to fit quite nicely.

A number of theories exist regarding the origin of New York’s

nickname. Some say it began as a term used in Harlem in the 1930s,

meaning the biggest and best. Others have traced it to a dance craze

called The Big Apple. The Museum of the City of New York found

evidence in The City in Slang, a book published in 1995, of an earlier

appearance. According to that book, a writer, Martin Wayfarer, used

the term in 1909 as a metaphor to explain the vast wealth of New York

compared to the rest of the nation. Wayfarer is cited as saying: ‘‘New

York [was] merely one of the fruits of that great tree whose roots go

down in the Mississippi Valley, and whose branches spread from one

ocean to the other . . . [But] the big apple [New York City] gets a

disproportionate share of the national sap.’’

The term gained popularity in the 1920s after John J. FitzGerald,

a newspaperman who wrote about horse racing, heard stable hands at

a New Orleans track refer to the big-time racetracks in New York state

as the Big Apple. FitzGerald called his racing column ‘‘Around the

Big Apple,’’ which appeared in the New York Morning Telegraph.

According to the Museum of the City of New York, FitzGerald’s

February 18, 1924 column began: ‘‘The Big Apple. The dream of

every lad that ever threw a leg over a thoroughbred and the goal of all

horsemen. There’s only one Big Apple. That’s New York.’’

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, musicians used the term to

make the point that when they played in New York, they were playing

in the big time, not small-town musical dates. Later, the term fell

somewhat out of favor. In the 1970s, however, when the city was

suffering financial problems, in an act of boosterism the New York

Convention and Visitor’s Bureau revived the term. Charles Gillett,

the president of the convention bureau, started a promotional cam-

paign by getting comedians and sports stars to hand out little red ‘‘Big

Apple’’ lapel pins. The symbol caught on and The Big Apple theme

was established.

As for racing writer FitzGerald, his recognition for contributing

to The Big Apple legend came in 1997 when New York City’s

Historic Landmarks Preservation Center placed a plaque on the

corner where FitzGerald had lived, West 54th Street and Broadway.

The plaque bore the name ‘‘Big Apple Corner.’’

—Michael L. Posner

F

URTHER READING:

Allen, Irving Lewis. The City in Slang: New York Life and Popular

Speech. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993.

Barie, Susan Paula. The Bookworms’s Big Apple: A Guide to Manhat-

tan’s Booksellers. New York, Columbia University Press, 1994.

BIG BANDSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

247

A view of the Big Apple from the New Jersey side of the Hudson River.

Big Bands

The Big Band Era (roughly 1935 to 1945) witnessed the emer-

gence of jazz music into the American mainstream at a time, accord-

ing to Metronome magazine in 1943, ‘‘as important to American

music as the time of Emerson and Thoreau and Whitman and

Hawthorne and Melville was to American literature.’’ Big band

music evolved from the various forms of African American music—

blues, ragtime, and dixieland jazz—performed by black and white

musicians such as Bessie Smith, Buddy Bolden, Jelly Roll Morton,

Scott Joplin, W.C. Handy, and the Original Dixieland Jazz Band

(ODJB). The frenetic, chaotic, and spontaneous nature of 1920s jazz

influenced the large orchestras, like Paul Whiteman’s, that special-

ized in dance music. Four- and five-piece Dixieland bands became

ten-piece bands such as Fletcher Henderson’s, and eventually the

twenty piece bands of Benny Goodman and Duke Ellington. The

music not only marked a synthesis of rural African American music

and European light classical music, but its widespread acceptance

expressed the larger national search for a uniquely American culture

during the Great Depression and World War II.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, popular music was

dominated by theatrical music, minstrel shows, and vaudeville,

produced primarily in New York City’s Tin Pan Alley. The music

followed typical European conventions of melody, harmony, tone,

and rhythm, with melody receiving priority over all else. Even

minstrel shows conformed to these conventions of western music

despite their claims to represent African American culture. Emphasis

on the melody was reinforced by the preferential status of lyrics in Tin

Pan Alley music. Both elements lent themselves well to the fact that

this music was primarily sold as sheet music for individual home use.

Simple melodies and arrangements with clever and timely lyrics did

not depend on a specific type or quality of performance for their

appreciation or consumption. As recorded music and radio broadcasts

became more widespread and available, emphasis shifted to the

specific character and quality of musical performance and to the

greater use of popular music in social dancing, which had previously

been relegated to the elite realm of ballroom dancing or the folk realm

of square dancing and other folk dancing forms.

At the same time that the central characteristic of popular music

shifted from composition to performance, African American music

gained in exposure and influence on popular music. The first adapta-

tions of black music to European instrumentation and form occurred

in New Orleans as black musicians began playing a version of

spirituals and field hollers on European band instruments such as

trumpets and clarinets. Integrating marches into black music, and

emphasizing improvisation over arrangement, jazz music developed

BIG BANDS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

248

into three distinct forms, the blues (the form most closely aligned with

traditional African American music), dixieland (marching band in-

struments performing polyphonic, improvisational music), and rag-

time (a more structured version of dixieland for piano). Each of these

musical styles did enjoy a measure of popularity, but mainly in

watered-down form such as the Tin Pan Alley practice of ‘‘ragging’’ a

song, best exemplified by Irving Berlin’s ‘‘Alexander’s Ragtime

Band’’ (1911).

With World War I, and the military’s forced closure of Storyville,

the official red light district of New Orleans where many jazz

musicians found employment, jazz music moved to other urban areas

such as Kansas City, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. As jazz

music spread, the audience for jazz increased, encompassing a young

white audience searching for music more dynamic than theatrical

music, in addition to a larger black audience. This younger audience

also favored music for dancing over home performances or staged

performances and therefore appreciated the largely instrumental and

rhythmic nature of jazz. With this growing audience, bands grew to

include sections of instruments instead of the traditional dixieland

arrangement of four or five soloists. Louis Armstrong and Fletcher

Henderson pioneered the larger band format by creating multiple

trumpet and trombone parts, as well as multiple reeds (clarinet, alto,

and tenor saxophones) and rhythm parts. In 1924, Henderson’s

pathbreaking Roseland Ballroom Orchestra consisted of eleven play-

ers, including Coleman Hawkins, Don Redman, and Louis Arm-

strong. In 1927, the upscale Harlem nightclub, the Cotton Club, hired

Duke Ellington and his band; Ellington created an orchestra and jazz

style with his own compositions, arrangements, and direction.

Ellington’s Cotton Club Orchestra reached an avant-garde white

audience and sparked the careers of other black bands as well as the

creation of white bands playing jazz music, such as Benny Goodman’s.

In August of 1935, Benny Goodman ushered in the ‘‘Swing

Era’’ when he ended a national tour with his band at the Palomar

Ballroom in Los Angeles. After receiving only lukewarm responses

from audiences across the country, Goodman filled the final show of

the tour with ‘‘hot’’ arrangements by Fletcher Henderson, as opposed

to the more ‘‘acceptable’’ dance tunes of other orchestras. The young

L.A. audience went crazy over the music and by the time Goodman

returned to New York in 1936 he had been named ‘‘The King of

Swing.’’ The early 1930s had been hard times for jazz musicians

since many civic leaders, music critics, and clergy cited the ‘‘primi-

tive’’ nature of jazz music as part of the cultural decline responsible

for the Great Depression. Selective use of jazz idioms, such as George

Gershwin’s symphonic piece ‘‘Rhapsody in Blue’’ (1924) and opera

‘‘Porgy and Bess’’ (1935), did gain respectability and praise for

creating a uniquely American musical language, but ‘‘pure’’ jazz,

even played by white musicians, was unacceptable. This thinking

changed with the success of Benny Goodman and several other newly

formed bands such as the Dorsey Brothers (with Glenn Miller as

trombonist and arranger), Charlie Barnet, Jimmy Lunceford, Chick

Webb, and Bob Crosby.

While live performances were the mainstay of big bands, many

were able to increase their audiences through radio shows sponsored

by companies eager to tap the youth market. Camel Cigarettes

sponsored Benny Goodman and Bob Crosby; Chesterfield sponsored

Hal Kemp, Glenn Miller, and Harry James. Philip Morris sponsored

Horace Heidt; Raleigh sponsored Tommy Dorsey; Wildroot Cream

Oil presented Woody Herman; and Coca-Cola sponsored a spotlight

show featuring a variety of bands. Juke boxes also provided a way for

young people to access the music of the big bands, in many cases

outside of parental control. Even movie theaters, searching for ways

to increase declining depression audiences, booked bands which

usually played after several ‘‘B’’ movies. In both dance halls and

auditoriums, big bands attracted screaming, writhing crowds, who not

only danced differently than their parents, but started dressing differ-

ently, most notably with the emergence of the Zoot suit. As big band

music became more popular and lucrative, organized resistance to it

declined, although it never disappeared. Respectability came in 1938

with the first appearance of a swing band at Carnegie Hall in New

York, the bastion of respectable classical music. Benny Goodman and

orchestra appeared in tuxedos and performed, among other songs, the

lengthy and elaborate, ‘‘Sing, Sing, Sing,’’ which included drum

solos by Gene Krupa.

The success of these bands, which usually featured about a

dozen or more players along with vocalists, allowed band leaders to

experiment with more jazz-influenced arrangements and longer sec-

tions of improvised solos between the highly arranged ‘‘riffs’’ and

melodies. The music was still primarily for dancing, and the youthful

audience demanded a more upbeat music to accompany its newer,

more athletic style of jitterbug dancing, like the ‘‘Lindy Hop,’’ named

for record-breaking pilot Charles Lindbergh. The New York Times, in

1939, recognized this new music as a form of music specifically

representative of a youth culture. ‘‘Swing is the voice of youth

striving to be heard in this fast-moving world of ours. Swing is the

tempo of our time. Swing is real. Swing is alive.’’ Lewis A. Erenberg

in Swingin’ the Dream: Big Band Jazz and the Rebirth of American

Culture, sees swing music as an expression of youth culture which

connects the youth culture of the 1920s to that of the 1950s. Not only

did swing music and the big bands reinforce a new expressiveness

among American youth, but big bands also crossed the color line by

bringing black and white audiences together and through integrating

the bands themselves, as Benny Goodman did in 1936 when he hired

Teddy Wilson as his pianist. Even though most sponsored radio was

segregated, audiences listening to Goodman’s broadcast would often

hear black musicians such as Lionel Hampton, Ella Fitzgerald, Count

Basie, and Billie Holiday. In addition, remote broadcasts from

Harlem’s Cotton Club, Savoy Ballroom, and the Apollo Theater,

while not national, found syndication to a primarily young, white,

late-night audience. Big band swing music was, according to histori-

an David W. Stowe in Swing Changes: Big-Band Jazz in New Deal

America, ‘‘the preeminent musical expression of the New Deal: a

cultural form of ’the people,’ accessible, inclusive, distinctly demo-

cratic, and thus distinctly American.’’ He further states that ‘‘swing

served to bridge polarities of race, of ideology, and of high and low

culture.’’ As the most popular form of music during the Depression

and World War II, swing music took advantage of newly developed

and fast-spreading technologies such as radio, records, and film

(many bands filmed performances which were shown, along with

newsreels and serials, as part of a motion picture bill). Much of its

appeal to young people was its newness—new arrangements of

instruments, new musical elements, new rhythm and tempo, all using

the newest media.

The big bands consisted of four sections: saxophones, trumpets,

trombones, and rhythm section, in addition to vocalists (soloists,

groups, or both). The saxophone section usually consisted of three to

five players on soprano, alto, tenor, and baritone saxophones and

doubling on clarinet and flute. The trumpet and trombones sections

each consisted of three or four members, and the rhythm section