Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BROWNENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

369

popular song forms in a gospel style that are delivered, for that time, in

a raw supplicating manner. The second period, in the early to mid-

1960s, consists of songs based on a modification of the twelve-bar

blues form with gospel vocal styles and increasingly tight and

moderately complex horn arrangements used in a responsorial fash-

ion. Compositions from this period include ‘‘Night Train’’ (not an

original composition), ‘‘I Feel Good,’’ ‘‘Papa’s Got a Brand New

Bag,’’ and ‘‘I Got You.’’ The third period, from the late 1960s and

beyond, finds Brown as an innovator breaking away from standard

forms and a standard singing approach to embark on extensive vamps

in which the voice is used as a percussive instrument with frequent

rhythmic grunts, and with rhythm-section patterns that resemble West

African polyrhythms. Across these three periods, Brown moves on a

continuum from blues and gospel-based forms and styles to a pro-

foundly Africanized approach to music making. Most significantly,

Brown’s frenzied and rhythmically percussive vocal style, based on

black folk preaching and hollering, combine with his polyrhythmic

approach to generate movement and to recreate in a secular context

the ecstatic ambience of the black church. Brown’s innovations,

especially in his latter period, have reverberated throughout the

world, even influencing African pop. From the mid-1980s, as found

in his composition ‘‘The Funky Drummer,’’ Brown’s rhythms,

hollers, whoops, screams, and vocal grunts have informed and

supplied the core of the new hip-hop music. His influence on artists

such as Public Enemy and Candy Flip is evident.

In the midst of his travails during the 1970s, Brown turned to

religion and also sought the legal help of William Kunstler. He broke

with Polydor Records and began to play in rock clubs in New York.

He appeared in several films, including the role of a gospel-singing

preacher in The Blues Brothers (1980), a part in Dr. Detroit (1983),

and a cameo appearance in Rocky IV (1985), in which he sang

‘‘Living in America.’’ It reached number four on the pop charts, his

first hit in more than a decade.

Even after these triumphs, Brown again began encountering

trouble with the law. In December, 1988 he was dealt two concurrent

six-year prison sentences for resisting arrest and traffic violations

during an incident in Atlanta in September of that year, when he had

brandished a shotgun in a dispute over the use of his private bathroom

in his office. After a high-speed police chase and charges of driving

under the influence of drugs, he was arrested and convicted only

aggravated assault and failing to stop for a police car. As he explained

to Jesse Jackson, ‘‘I aggravated them and they assaulted me.’’ He was

paroled in 1991, after appeals by Jackson, Little Richard, Rev. Al

Sharpton, and others. Brown continued to tour and record in the

1990s. He appeared at New York’s Paramount Theater in March,

1992, with his new band, the Soul Generals and his female backup

group, the Bittersweets. In 1994, his name again appeared on the

crime-blotter pages in an incident involving the assault of his wife,

Adrienne. Four years later, in 1998, he was charged with possession

of marijuana and unlawful use of a firearm.

In the 1990s, Brown became a vocal supporter of the campaign

to suppress X-rated lyrics in rap songs by asking rap artists not to

include samples of his songs in such works. It was estimated by one

critic that 3,000 house and hip-hop records have made use of his

original music since the 1980s. In 1987, Brown was one of the first ten

charter members elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and in

1992, he was honored at the American Music Awards ceremonies

with an Award of Merit for his lifetime contribution to the genre.

—Willie Collins

F

URTHER READING:

Brown, James, with Bruce Tucker. The Godfather of Soul: James

Brown. New York, Macmillan, 1986.

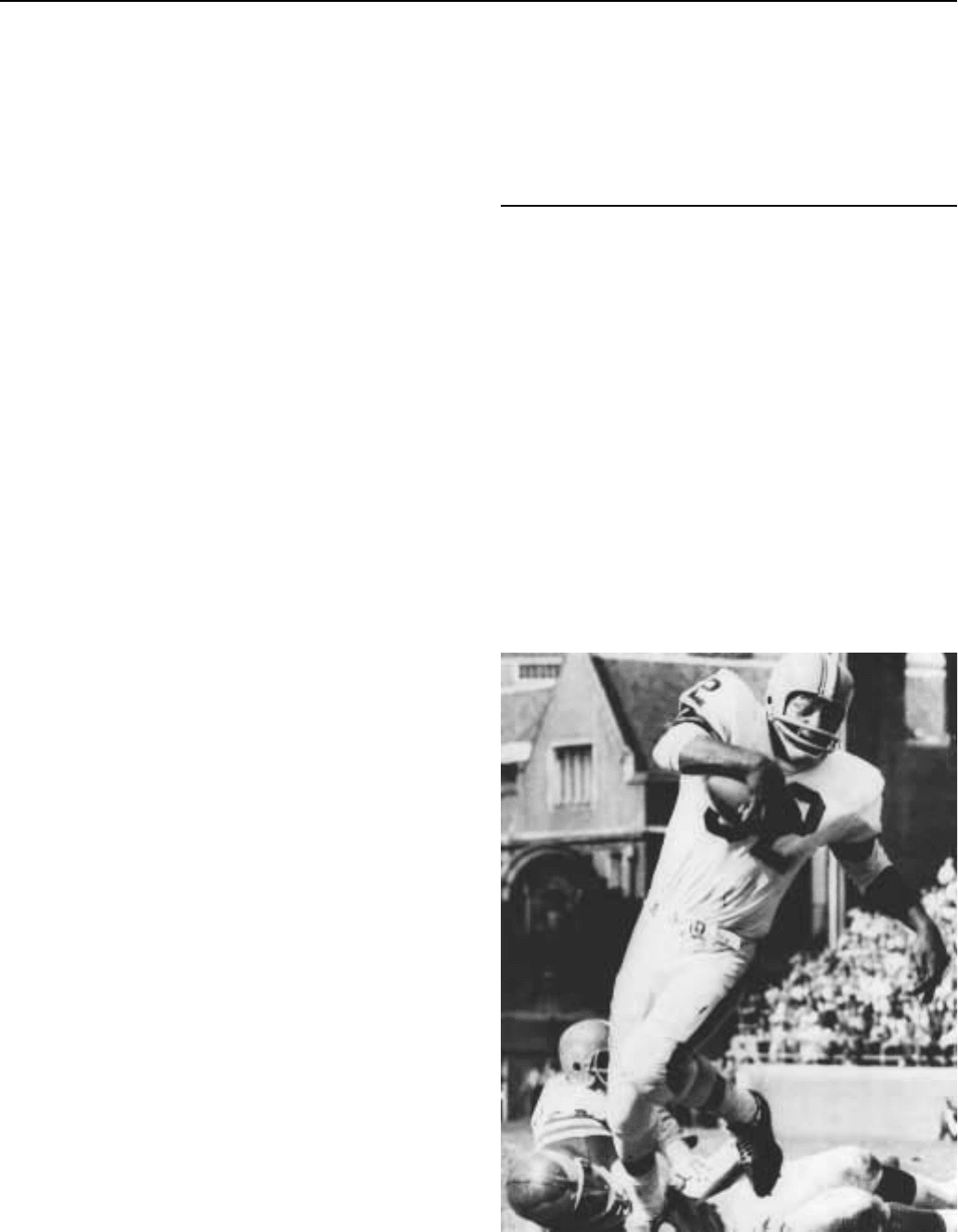

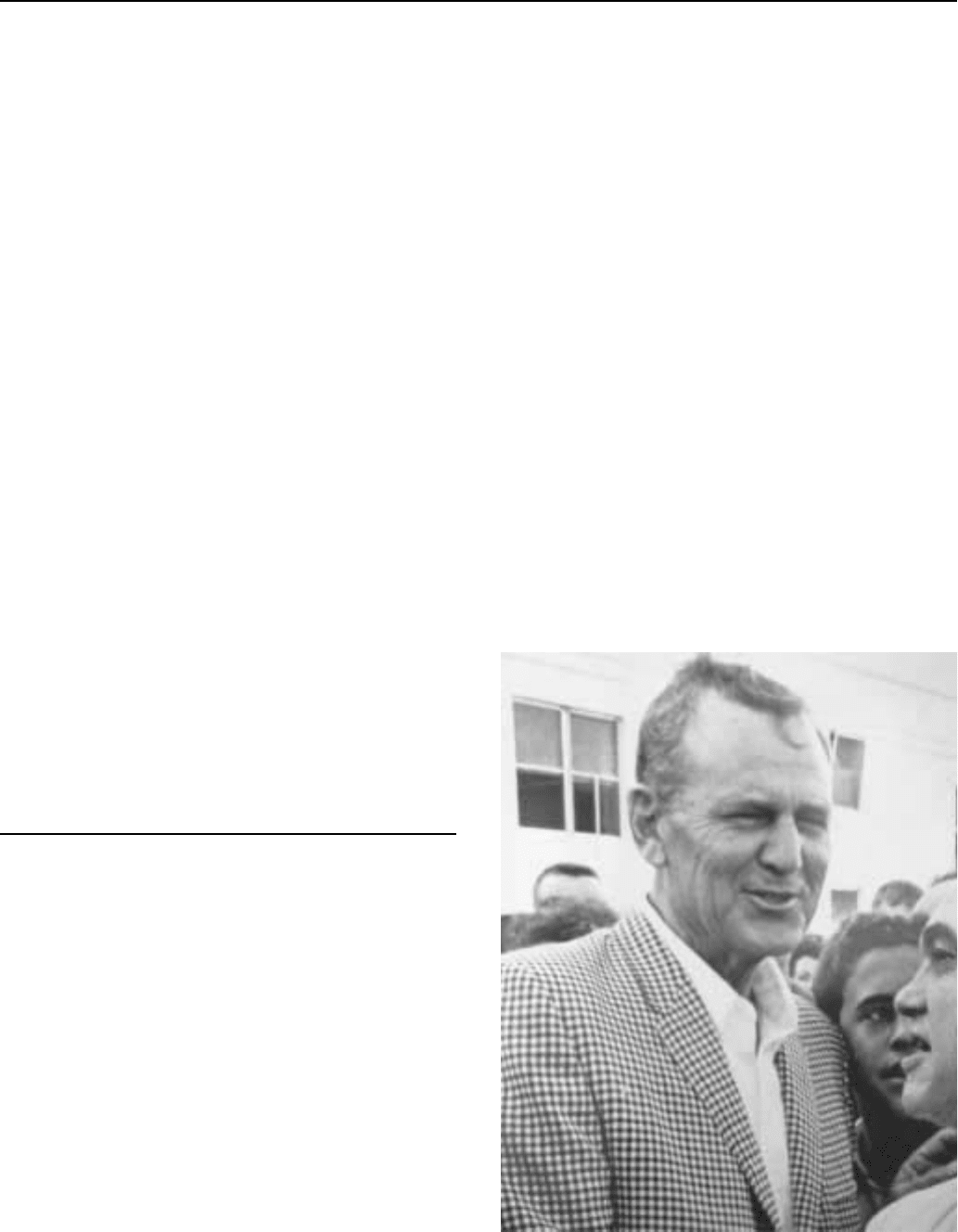

Brown, Jim (1936—)

Jim Brown was simply one of the best football players ever. In

just nine seasons in the National Football League, Brown collected

eight rushing titles en route to setting new records for most yards in a

season and most career rushing yards. A three-time MVP, Brown was

inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1971.

Born on the coastline of Georgia, Brown moved to Long Island,

New York, and attended Manhasset High School where he earned all-

state honors in basketball, track, and football. After high school

Brown declined a minor league contract with the New York Yankees,

opting to play football at Syracuse University instead. While playing

for the Orangemen he earned All-American honors in both football

and lacrosse.

In 1957 he was drafted by the Cleveland Browns of the National

Football League, and in his first season he led the Browns to the

Championship game. That year Brown also won the league rushing

title, which earned him the Rookie of the Year Award. But in his

opinion his freshman campaign was not ‘‘spectacular.’’ In spite of

Brown’s modesty, fans thought otherwise as he quickly became a

Jim Brown

BROWN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

370

crowd favorite because of his seemingly fearless and tireless

running style.

In 1963 Brown made history when he rushed for a league record

1883 yards. That season he had games of 162 (yards), 232, 175, 123,

144, 225, 154, 179, and 125. ‘‘I was twenty-seven years old. I never

ran better in my life,’’ said Brown. The following year Brown led his

team to the NFL Championship, but in 1965 he shocked football fans

by announcing his retirement in the prime of his career.

The popular Brown did not slip quietly into retirement however;

he capitalized on his fame by becoming Hollywood’s ‘‘first black

man of action’’ by starring in several movies such as Rio Conchos

(1964), the box office hit The Dirty Dozen (1967), and other films

including The Grasshopper (1970), Black Gunn (1972), and Tick. . .

Tick. . . Tick. . . (1970). In 1972 he starred in the world’s first

authentic blaxploitation movie, Slaughter, which was filmed in

Mexico on a $75,000 budget. This placed him into competition with

other black stars of that genre including Fred Williamson, Jim Kelly,

and Pam Grier. Brown’s most popular film and to some extent his

most controversial was One Hundred Rifles (1969), in which Raquel

Welch was his love interest. This was one of the first films involving a

love scene between a black man and a white woman. ‘‘We took a

publicity shot of me, with no shirt on, and Raquel, behind me, her

arms seductively across my chest. For American film it was revolu-

tionary stuff,’’ said Brown.

In addition to football and acting Brown also was devoted to

improving the conditions of the black community. In the late 1960s he

formed the Black Economic Union to assist black-owned business

and after leaving the silver screen he became a community activist.

In his day, Brown was one of the few athletes who could

transcend the playing field and become part of the broader American

culture. Even today, he is the standard by which all other NFL runners

are measured.

—Leonard N. Moore

F

URTHER READING:

Brown, Jim. Out of Bounds. New York, Zebra Books, 1989.

James, Darius. That’s Blaxploitation! New York, St. Martin’s Grif-

fin, 1995.

Toback, James. Jim: The Author’s Self-centered Memoir on the Great

Jim Brown. Garden City, New York, Doubleday, 1971.

Brown, Les (1912—)

A band leader for nearly 60 years, Les Brown and his ‘‘Band of

Renown’’ were best known as a first-class swing band operating

primarily in the pop-music field. Brown was a student at Duke

University from 1932-35, where he formed his first dance band, the

Duke Blue Devils. After that band folded in September, 1937, Brown

worked as a freelance arranger for Larry Clinton and Isham Jones. He

formed a new band in 1938, and throughout the 1940s became

increasingly well-known, featured on television touring with Bob

Hope to entertain service men at Christmas. The band reached its peak

when Doris Day was featured as vocalist in 1940 and again from

1943-46. The orchestra’s best-remembered arrangements were writ-

ten by Ben Homer, who also composed the band’s theme song,

‘‘Sentimental Journey.’’

—Benjamin Griffith

F

URTHER READING:

Balliett, Whitney. American Musicians. New York, Oxford, 1986.

Simon, George T. The Big Bands. New York, MacMillan, 1974.

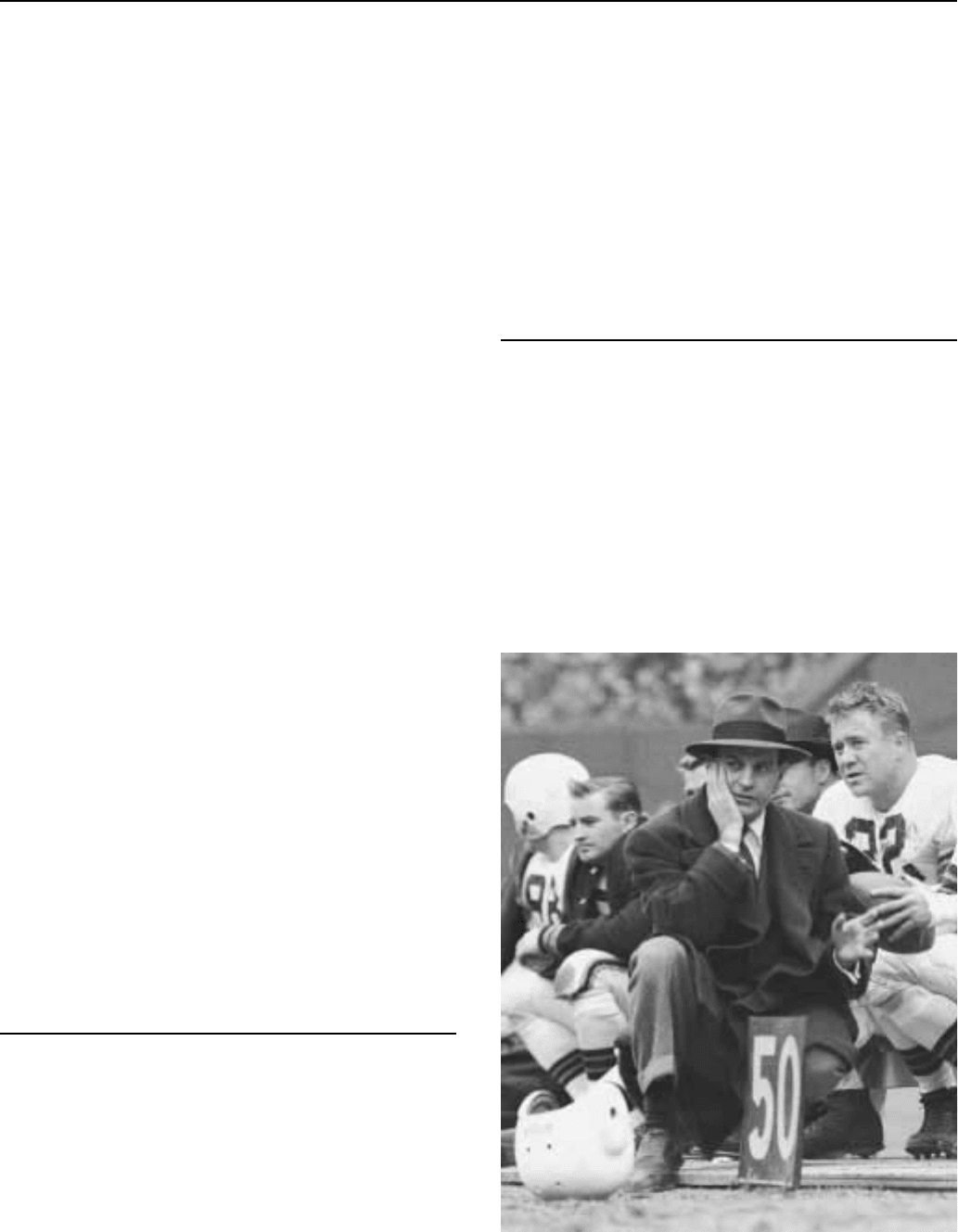

Brown, Paul (1908-1991)

Paul Brown, founder and first head coach of both the Cleveland

Browns and Cincinnati Bengals, played a major role in the evolution

of football. He was the first coach to use detailed game plans,

playbooks, and classroom learning techniques. He hired the first full-

time coaching staff. He also initiated the use of intelligence tests to

measure learning potential and film replays and physical tests such as

the 40-yard dash to evaluate players. Brown was also the first coach to

send plays in from the bench and to use facemasks on helmets. As a

professional coach with the Browns (1946-62) and Bengals (1968-

75), he compiled a 222-112-9 record including four AAFC (All-

American Football Conference) and three NFL titles. His coaching

proteges include Don Shula and Bill Walsh, coaches who led their

Coach Paul Brown and the Cleveland Browns.

BROWNIE CAMERASENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

371

respective clubs to Super Bowl championships. Brown was inducted

into the Professional Football Hall of Fame in 1967.

—G. Allen Finchum

FURTHER READING:

Brown, Paul and Jack T. Clary. PB: The Paul Brown Story. New

York, Atheneum, 1979.

Long, Tim. Browns Memories: The 338 Most Memorable Heroes,

Heartaches and Highlights from 50 Seasons of Cleveland Browns

Football. Cleveland, Ohio, Gray and Company, 1996.

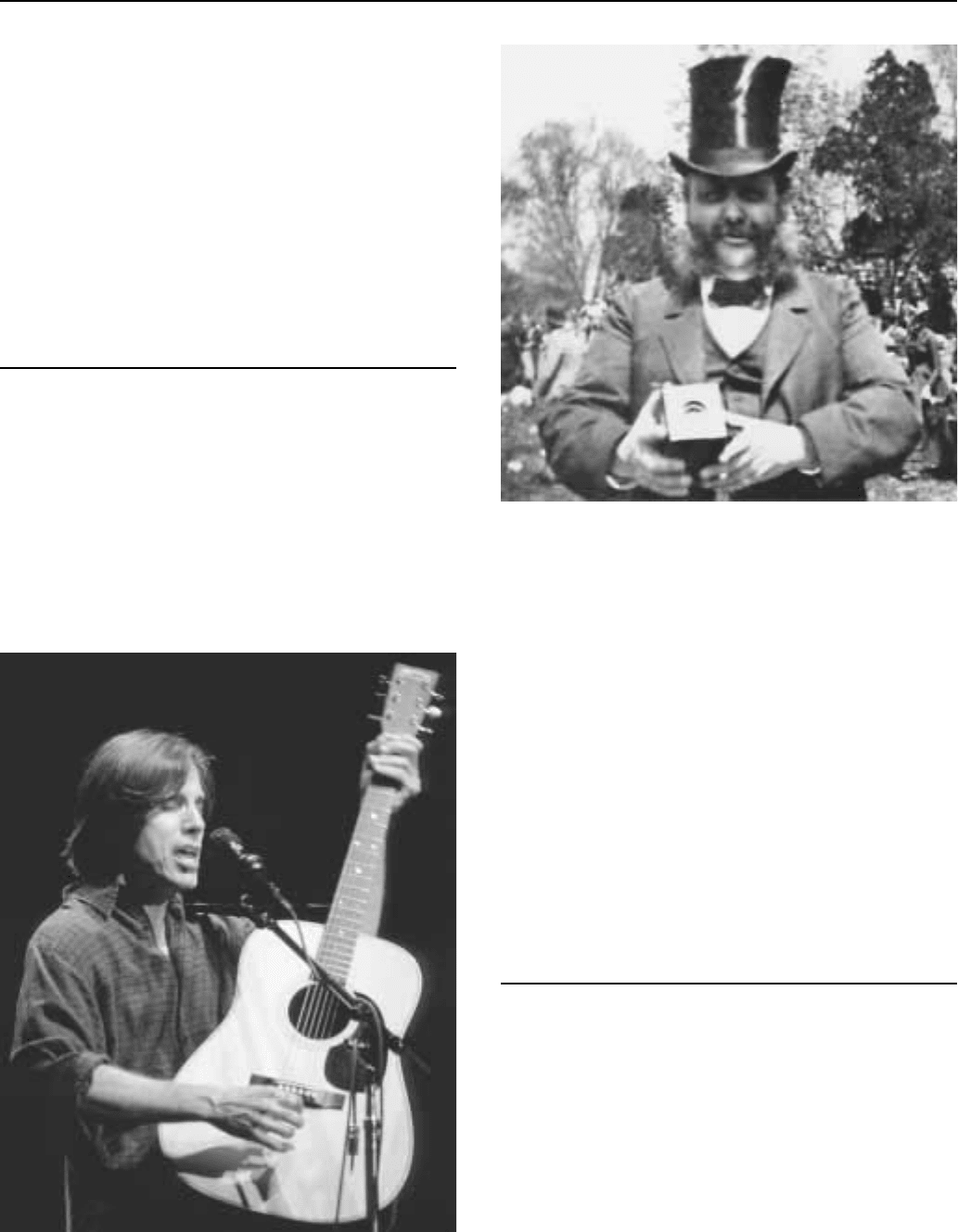

Browne, Jackson (1948—)

Romantic balladeer turned political activist, Jackson Browne is

one of America’s most enduring singer-songwriters. Raised in South-

ern California, Browne joined the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band while in high

school, but quit to pursue a solo career in New York, where he hung

out at Andy Warhol’s Factory and fell in love with singer Nico. After

signing with David Geffen, Browne came home and became part of

the L.A. music scene that included Joni Mitchell, the Eagles, and

Crosby, Stills and Nash. Browne’s first album was released to strong

reviews in 1972 and his first single, ‘‘Doctor My Eyes,’’ climbed to

number eight on Billboard’s Top 100. With his poetic songwriting

and boyish good looks, Browne’s next four albums won both critical

Jackson Browne

Man holding Kodak Brownie camera, 1900.

acclaim and commercial success. In the 1980s, Browne became an

outspoken liberal activist and his songwriting began to take on a

strongly political cast. After a very public split with actress Darryl

Hannah in 1991, Browne’s songs once again turned confessional.

Long regarded as one of the most important artists to come out of

Southern California, Jackson Browne remains one of the music

industry’s most complex and fascinating figures.

—Victoria Price

F

URTHER READING:

DeCurtis, Anthony. ‘‘Jackson Browne.’’ Rolling Stone. October 15,

1992. 138-139.

Santoro, Gene. ‘‘Jackson Browne.’’ Nation. Vol. 262, No. 19, May

13, 1996, 32-36.

Brownie Cameras

The Brownie Camera revolutionized popular photography world-

wide by bringing it within the reach of all amateurs, including

children. Commissioned by George Eastman and manufactured by

the Eastman Kodak Company, it was launched in February, 1900. A

small box camera that utilized removable roll-film and a simple rotary

shutter, the new Brownie sold for just one dollar, plus fifteen cents

extra for film. Its name was derived from Palmer Cox’s familiar and

beloved pixies, whose image Kodak incorporated into its brilliant and

concentrated advertising campaign; even the box in which the camer-

as were packaged featured Cox’s colorful characters. The Brownie

was an immediate success: 100,000 sold within a single year. Various

features were added over the next few decades, including color on the

Beau Brownie of the early 1930s, and flash contacts on the Brownie

BRUBECK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

372

Reflex introduced in 1946. Many special Brownies were also made,

such as the Boy Scout Brownie (1932, 1933-34) and the New York

World’s Fair Baby Brownie (1939). The last Brownie model, the

Brownie Fiesta, was discontinued in 1970.

—Barbara Tepa Lupack

FURTHER READING:

Coe, Brian. Cameras: From Daguerreotypes to Instant Pictures.

N.p.: Crown Publishers, 1978.

Kodak Homepage. http:\www.kodak.com.

Lothrop, Eaton S., Jr. A Century of Cameras: From The Collection of

the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman

House. Dobbs Ferry, Morgan & Morgan, 1973.

Brubeck, Dave (1920—)

Jazz legend Dave Brubeck is famous both as a composer and

pianist. As the leader of the Dave Brubeck Quartet with alto saxo-

phonist Paul Desmond, he achieved overwhelming popular success in

the 1950s and 1960s. The Quartet’s experimentation with unusual

time signatures produced works like ‘‘Blue Rondo a la Turk’’ and

‘‘Take Five’’ among others, and Brubeck introduced millions of

enthusiastic young listeners to jazz. In less than a decade, the Dave

Brubeck Quartet became one of the most commercially successful

jazz groups of all time.

Although some jazz traditionalists felt that Brubeck was playing

‘‘watered-down’’ bebop to sell records, his music brought jazz back

into the mainstream of popular music. ‘‘Take Five’’ became Brubeck’s

signature tune, and it remains one of the most widely recognized jazz

compositions in the world.

—Geoff Peterson

F

URTHER READING:

Hall, F.M. It’s about Time: The Dave Brubeck Story. Fayetteville,

University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

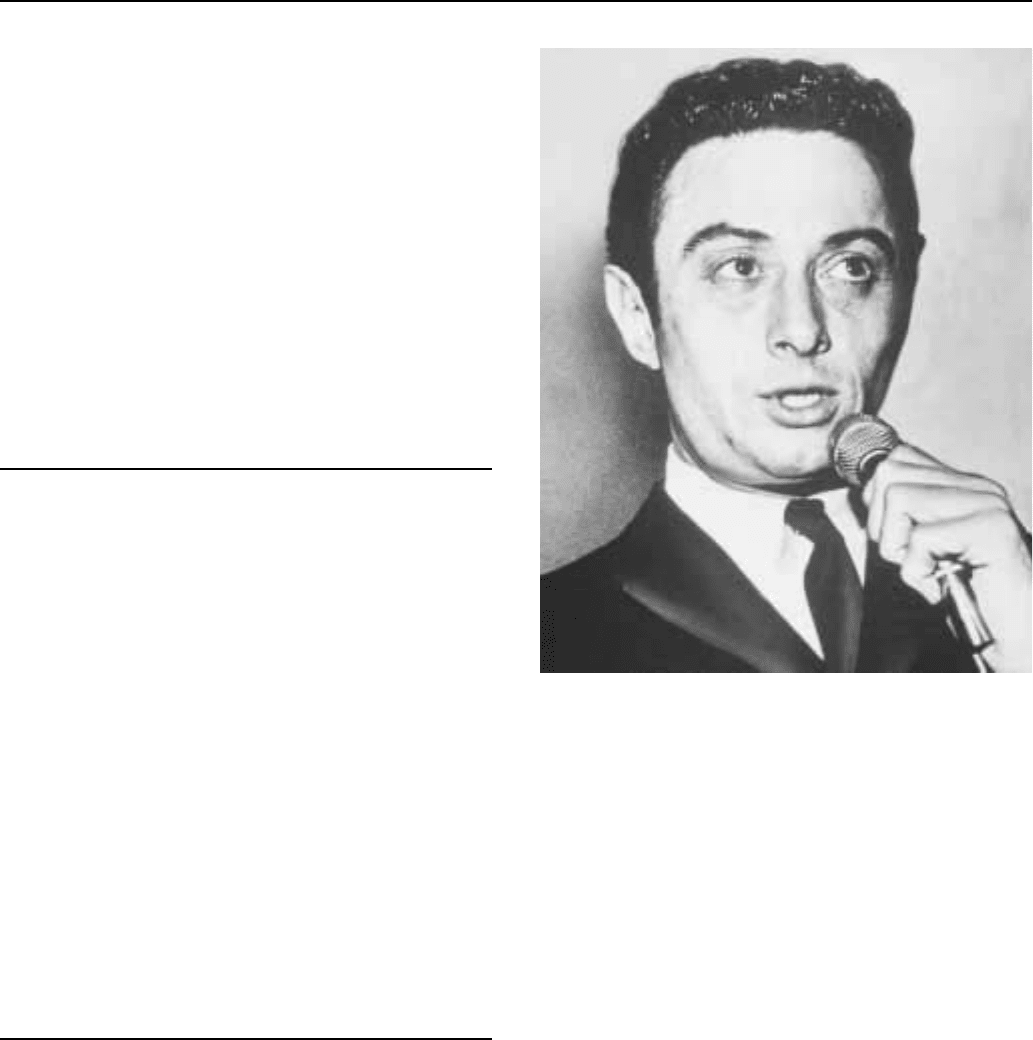

Bruce, Lenny (1925-1966)

From the late 1940s until his death in the 1960s, Lenny Bruce’s

unique comedy included social commentary, ‘‘lewd’’ material, and

pointed personal monologues. He addressed issues of sex, race, and

religion, and often did so using profanity. Many of his era called his

humor ‘‘sick,’’ and Journalist Walter Mitchell referred to him as

‘‘America’s #1 Vomic.’’ Police arrested Bruce numerous times for

obscenities, which helped him to become a champion of First Amend-

ment rights and of freedom of speech in general. His work on and off

stage permanently changed the face of comedy, particularly stand-up

comedy, and pushed the limits of what was considered ‘‘socially

acceptable’’ in many mediums. By 1990s standards his material was

quite tame and is commonly found on television or even in ‘‘PG’’

rated films, but during his time his work was radical. Many well-

known comedians, including Joan Rivers, Jonathan Winters, and

Lenny Bruce

Richard Pryor, have attested to Bruce’s profound influence on

their work.

From approximately the 1920s to the early 1950s, most comedi-

ans came out of vaudeville. Comedy, or more precisely jokes, were

interspersed in people’s vaudeville acts. Jack Benny, for instance,

was a vaudeville star who originally did jokes between his violin

playing; he eventually played some violin between his jokes or

comedy routines. Comedians did a series of ‘‘classic’’ joke-book type

jokes, or occasionally a variation on these. In the late 1940s and into

the 1950s, comedy began to change with the cultural changes of the

times. The United States was experiencing a push towards conserva-

tism; middle-class mores were pervasive and commonly exempli-

fied in such light ‘‘comedy’’ shows as Father Knows Best and

Donna Reed. Additionally, McCarthyism had people fearful of any-

thing ‘‘different’’ they said being held against them. There was,

however, also a strong backlash against this conservatism typi-

fied in the ‘‘Beatnik’’ movement, including artists such as Allen

Ginsburg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Bruce was part of this counter-

culture movement.

Bruce was born Leonard Alfred Schneider on October 13, 1925

in Mineola, New York. His father, Mickey, was a podiatrist and his

mother, Sadie, played bit parts as an actor and did routines in small

comedy clubs under the names of Sally Marr and Boots Mallow.

From a very young age, Bruce’s mother took him to burlesque and

nightclubs. Her willingness to expose him to this style of ‘‘open

sexuality’’ influenced most of his career. Bruce’s very early career

was doing conventional comedy routines in the ‘‘Borscht Belt’’—the

Jewish area of the Catskills where many (Jewish) comedians, such as

BRUCEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

373

Danny Kaye and Jerry Lewis, got their start; he also did comedy

routines in strip clubs. In 1942, Bruce enlisted in the Navy, serving

until 1945, when he was dishonorably discharged for claiming to be

obsessed with homosexual ideas.

Bruce started developing his own notable style, which not only

included the ‘‘obscenities’’ he is often remembered for, but also a

running social commentary told in fast-paced, personally-based mono-

logues that used various accents and voices to emphasize his pointed

style. He received his first national recognition when he was on the

Arthur Godfrey Talent Show in 1948. Soon after, his career was

furthered when his act at a San Francisco nightclub, Anne’s 440, was

reviewed by influential cutting-edge columnists Herb Caen and Ralph

Gleason (who later wrote many of Bruce’s liner notes for his

recordings). Some of his early recordings, all under the Fantasy

record label, include Interviews of Our Times, American, and The Sick

Humor of Lenny Bruce.

Two quintessential personal events also happened during these

‘‘earlier’’ years—Bruce met stripper Honey Harlow in 1951, whom

he married that year in June, and he was introduced to heroin, which

became a life-long habit and another reason for his many arrests.

Harlow had six abortions, some say at the insistence of Bruce, and

later gave birth to a daughter, Brandie Kathleen ‘‘Kitty,’’ in 1955.

When Bruce and Harlow divorced in 1957, Bruce was awarded

custody of Kitty.

In the early 1960s Bruce’s career skyrocketed, and by February

1961 he performed to a full house at Carnegie Hall. While he was

popular with people immersed in the counter-culture movement, he

also attracted many mainstream and even conservative people. Main-

stream comedians, such as Steve Allen, understood, appreciated, and

supported his comedy; Bruce appeared on Allen’s television show

three times. Others were highly insulted, not just by his ‘‘obscene

language,’’ but, for instance, by what they considered his blasphe-

mous attitudes towards organized religion. His act ‘‘Religions, Incor-

porated,’’ in which he compared religious leaders to con artists and

crooks, infuriated some and made others praise the raw intelligence

and honesty of his comedy. Other people were critical, but titillated by

his humor. Bruce often told the story about how people said they were

horrified by his common ‘‘threat’’ to urinate on his audience, but

when he would not do it people would complain and ask for their

money back.

The 1960s brought Bruce’s long series of arrests for narcotics

and obscenities, as well as his being banned from performing. In

September 1961, he was arrested for possession of narcotics, though

the charges were dropped because he had authorized prescriptions—

but in October 1962 he was once again arrested for possession of

narcotics in Los Angeles. With his January 1, 1963 arrest for narcotics

possession, however, some began to question whether the circum-

stances surrounding his arrests were, at the very least, ‘‘suspicious’’;

his convictions were based on testimony by an officer who was at the

time suspected of smuggling drugs. Conversely, though, Bruce him-

self once turned in a small-time drug dealer in exchange for his own

freedom from a drug charge.

Bruce’s first and probably best known arrest for obscenity was in

October 1961. He used the word ‘‘cocksucker’’ in his act at the San

Francisco Jazz Workshop; the word violated the California Obscenity

Code. (A number of reviewers have pointed out that in the 1980s

Meryl Streep won an Academy Award for the movie Sophie’s Choice,

where she also used the term ‘‘cocksucker.’’) With lawyer Albert

Bendich—who represented Allen Ginsberg when he was charged

with obscenity for his book Howl—Bruce eventually emerged vic-

torious and the event was seen as a landmark win for First

Amendment rights.

In October 1962, Bruce was arrested for being obscene during

his act at Hollywood’s Troubador Theater. In the same year, after two

Australian appearances, he was kicked out of Australia and banned

from Australian television; he was also deported from England twice.

In April 1963, on arriving in England, he was classified as an

‘‘undesirable alien’’ and sent back to the United States within two

hours. Upon arrival in the United States, customs agents stripped and

internally searched Bruce. Soon after, he was arrested for obscenity in

both Chicago and Miami. In 1963, Bruce also published his autobiog-

raphy, How To Talk Dirty and Influence People, and it was eventually

serialized in Playboy magazine. Despite—or perhaps because of—

these events, Bruce continued to make recordings throughout the

early 1960s, including To Is a Preposition, Come is a Verb, The

Berkeley Concert, and Live at the Curran Theatre.

Another of Bruce’s pivotal and very influential obscenity arrests

occurred in April 1964 at New York’s Cafe A Go-Go, where Tiny

Tim was his warm-up act. Over 100 well-known ‘‘alternative’’ artists

and activists, including Dick Gregory, Bob Dylan, Joseph Heller,

James Baldwin, and Gore Vidal, signed a petition which Allen

Ginsberg helped write. The petition protested New York using

obscenity laws to harass Bruce, whom they called a social-satirist on

par with Jonathan Swift and Mark Twain. Bruce himself said he did

not believe his arrest was about obscenity, but rather his views against

the system. New York’s District Attorney of that time, Richard Kuh,

felt Bruce should not be shown mercy because he lacked remorse;

Bruce openly stated he had no remorse and was only seeking justice.

On November 4, 1964, his work was deemed illegal for violating

‘‘contemporary community standards’’ and for being offensive to the

‘‘average person.’’ This was a severe blow to Bruce, as clubs were

afraid to hire him: if New York City responded in such a way, other

clubs around the United States would surely be shut down if he were

to perform in them. In October 1965, Bruce went to the San Francisco

office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), complaining that

California and New York were conspiring against his rights. Not

surprisingly, the FBI took no action.

Between difficulty being hired, his drug addiction, and his

financial concerns, Bruce found himself in an extremely difficult

predicament. A few days after complaining to the FBI he filed

bankruptcy in Federal Court. A few months later, under the influence

of drugs, he fell 25 feet out a window, resulting in multiple fractures in

both his legs and ankles. His last performance was at the Fillmore

West in San Francisco in June 1966, where he played with Frank

Zappa and The Mothers of Invention. Two months later, on August 3,

1966, Bruce was dead from a so-called accidental overdose of

morphine. Some say the police staged photographs of the scene to

make it look as if he accidentally overdosed. Regardless of the

circumstances, conspiracy and harassment were on Bruce’s mind

when he died—at the time of his death he was in the midst of writing

about the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees people protection

against ‘‘unreasonable search and seizure.’’

Sadly, Bruce neither lived to see his New York obscenity

conviction overruled in 1966, nor the dramatic changes that much of

his pioneering work helped catalyze. Ironically, by the 1970s, many

plays, books, and movies, were produced about Bruce that romanti-

cized and glorified his work. In death, he became part of the

mainstream entertainment world that often shunned him. The most

well-known and mainstream of these productions was the 1974 film

BRYANT ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

374

Lenny, based on the play by Julian Barry and starring Dustin Hoffman

as Bruce. Indeed, despite his incredible influence, many born after his

time thought of Bruce only as Hoffman’s portrayal in this stylized

film. Paradoxically, only eight years after his death, the film Lenny

was only given an ‘‘R’’ rating for routines that got Bruce arrested time

and time again. That his own work was considered so ‘‘tame’’ just a

short time after his death is perhaps a testimony to the degree of

change Lenny Bruce really initiated.

—tova gd stabin

F

URTHER READING:

Barry, Julian. Lenny: A Play, Based On the Life and Words of Lenny

Bruce. New York, Grove Press, 1971.

Bruce, Lenny. The Almost Unpublished Lenny Bruce: From the

Private Collection of Kitty Bruce. Philadelphia, Running Press, 1984.

———. The Essential Lenny Bruce, edited by John Cohen. New

York, Douglas Books, 1970.

———. How To Talk Dirty and Influence People: An Autobiogra-

phy. Chicago, Playboy Press, 1973.

Goldman, Albert Harry. Ladies and gentlemen—Lenny Bruce!! New

York, Random House, 1974.

Kofsky, Frank. Lenny Bruce: The Comedian as Social Critic and

Secular Moralist. New York, Monad Press, 1974.

Saporta, Sol. ‘‘Lenny Bruce on Police Brutality.’’ Humor. Vol. 7, No.

2, 1994, 175.

———. ‘‘The Politics of Dirty Jokes: Woody Allen, Lenny Bruce,

Andrew Dice Clay, Groucho Marx, and Clarence Thomas.’’

Humor. Vol. 7, No. 2, 1994, 173.

Thomas, William Karl. Lenny Bruce: The Making of a Prophet.

Hamden, Connecticut, Archon Books, 1989.

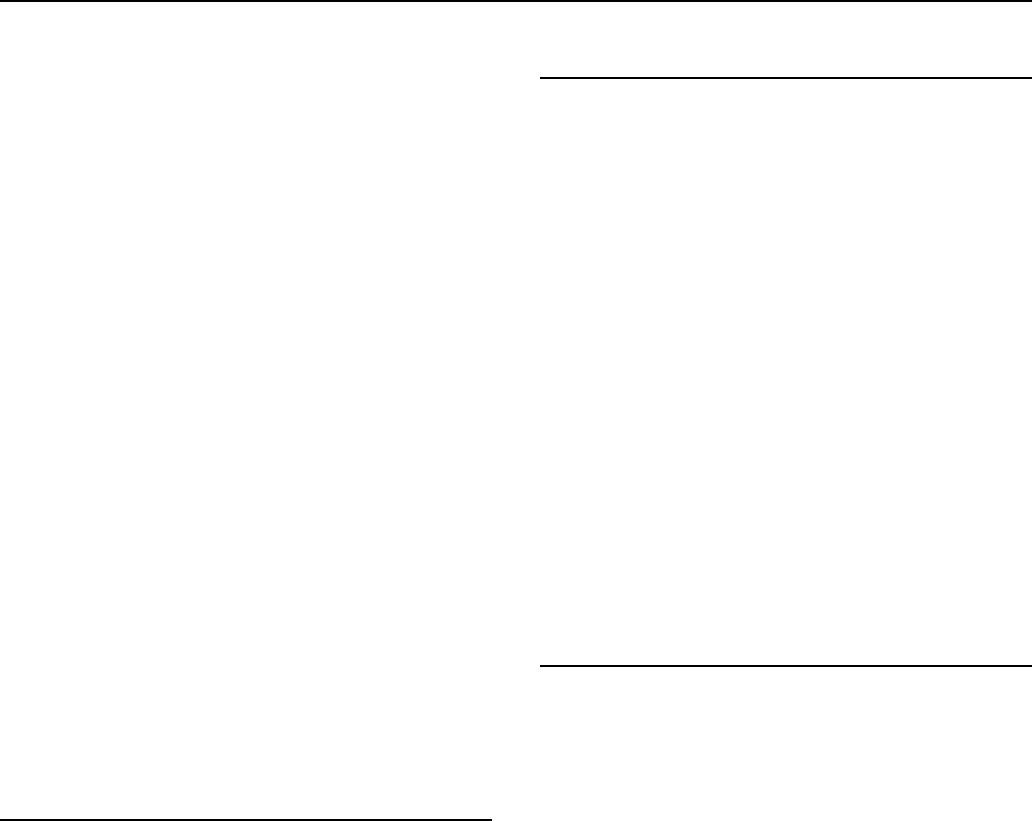

Bryant, Paul “Bear” (1913-1983)

Legend, hero, homespun philosopher, not to mention fashion

statement in his houndstooth check hat, Paul “Bear” Bryant has been

called a combination of “ham and humble pie.” A museum and a

football stadium in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, bear his name, and a movie,

released in August 1984, called, simply, The Bear, recounts his life.

His wife, however, didn’t like the film; she couldn’t imagine actor

Gary Busey playing her husband. “Papa was handsome,” she said,

and it was not only she who thought this. Men as well as women

agreed that Bear Bryant was a good-looking man. Morris Franks, a

writer for the Houston Chronicle, averred, “No Hollywood star ever

made a more dramatic entrance. He would jut that granite-like jaw

out, turn his camel’s hair topcoat collar up and be puffing on a

cigarette.” The coach evinced a wide-ranging appeal; even his life

was a sort of romance. He married his college sweetheart, Mary

Harmon, a University of Alabama beauty queen, and for 48 years she

remained by his side as best friend, alter ego, and helpmate to the man

who had once wrestled a bear in his home state of Arkansas for five

bucks and won.

Paul Bryant satisfied America’s craving for rags-to-riches and

larger-than-life stories. As the eleventh of twelve children, young

Paul grew up dirt poor in rural Arkansas, in a place called Morro

Bottom that consisted of six houses on Morro Creek. The Bryant

home was made up of four small rooms, a big dining room, and a little

upstairs area; but Paul thought of it as a plantation, and in the

mornings and evenings before and after school, he worked behind the

plow. He didn’t own a pair of shoes until age 13, but as he affirmed to

the boys who played on his teams, “If you believe in yourself and have

pride and never quit, you’ll be a winner. The price of victory is high

but so are the rewards.”

Bryant played college football at the University of Alabama on

the same team as Don Hudson, who was thought to be the greatest

pass-catching end in football in 1934. Nicknamed “Old 43” or “the

Other End,” Paul may not have been The End, but he became a hero

after playing a game against rival Tennessee with a broken leg. When

the team doctor removed his cast, Bryant was asked if he thought he

could play, and the rest is legend. Number 43 caught an early pass and

went for a touchdown. Later in the game, he threw a lateral to a player

who scored another. Examining the X-rays of the broken bone,

Atlanta sportswriter Ralph McGill, who had initially been doubtful

about the injury, acclaimed Bryant’s courage, but Bear, in typical big-

play fashion, replied, “It was just one little bone.”

Bryant went on to head coaching jobs at Maryland, Kentucky,

and Texas A & M, before returning to the University of Alabama.

When asked to come back to his alma mater, Bryant gave his famous

“Mama Called” speech to the fans and players at A & M. He said,

“When you were out playing as a kid, say you heard your mother call

you. If you thought she just wanted you to do some chores, or come in

for supper, you might not answer her. But if you thought she needed

Paul ‘‘Bear’’ Bryant

BUCKENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

375

you, you’d be there in a hurry.” Bryant served as head coach at the

University of Alabama from 1958 to 1982, where he led the Crimson

Tide to 323 victories and six national championships. He was named

the National Coach of the Year in 1961, 1971, and 1973, and SEC

Coach of the Year ten times.

Although he guided the Crimson Tide to thirteen SEC titles,

Coach Bryant stood for more than winning; he was a role model. His

players maintain that he taught them about life. The coach liked to say

that life was God’s gift, and a commitment should be made to put

something into it.

Paul Bear Bryant never failed in his dedication to the sport he

loved. After his death, Bryant’s heartfelt eulogies describing what the

Bear meant to Alabama, to coaching, and to the players who had been

molded by him, led author Mickey Herkowitz to conclude that college

football without Bryant would be like New Year’s Eve without a

clock. It was estimated that some 100,000 mourners lined the inter-

state from Tuscaloosa to Birmingham, Alabama, to pay their last

respects to a small town boy known as Bear. “Thanks for the

Memories, Bear,” their signs read, “We Love You,” and “We’ll Miss

You.” A hero had fallen, but he is remembered. Many feel he can

never be replaced.

—Sue Walker

F

URTHER READING:

Herskowitz, Mickey. The Legend of Bear Bryant. Austin, Texas,

Eakin Press, 1993.

Stoddard, Tom. Turnaround: The Untold Story of Bear Bryant’s First

Year As Head Coach at Alabama. Montgomery, Alabama, Black

Belt Press, 1996.

Brynner, Yul (1915-1985)

In 1951 Yul Brynner, a Russian-born Mongolian, made a multi-

award-winning Broadway debut in The King and I, and in 1956 he

won the Best Actor Oscar for the screen version. He shaved his head

for the role, and it is to this image of baldness as a badge of virile

exoticism that he owed his subsequent prolific and highly paid film

career during the 1960s and 1970s, as well as his continuing status as a

twentieth-century icon. Seemingly ageless, he continued to star in

revivals of the show until shortly before his much-publicized death

from lung cancer. Much of his early life is shrouded in self-created

myth, but he arrived in the United States in 1941, having worked as a

trapeze artist with the Cirque d’Hiver in Paris until injury intervened.

A largely mediocre actor, who appeared in increasingly mediocre

films, relying on his mysterious, brooding personality, he is also

remembered for his roles as the pharaoh in The Ten Commandments

(1956) and the black-clad leader of The Magnificent Seven (1960).

—Robyn Karney

F

URTHER READING:

Katz, Ephraim. The International Film Encyclopedia. New York,

HarperCollins, 1994.

Thomson, David. A Biographical Dictionary of Film. New York,

Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Bubblegum Rock

Bubblegum rock emerged in the late 1960s as a commercial

response to demographic changes in the rock music industry. With

major rock artists such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones maturing

after 1967 toward more adult styles, both musically and lyrically, as

they and their audiences grew up, they left behind a major segment of

the rock music marketplace: the pre-teen crowd. The music industry

rushed to capitalize on this younger market by assembling studio

musicians to record novelty songs with catchy hooks and sing-along

lyrics and packaging them as real ‘‘bands.’’ The approach worked,

resulting in a string of hits including, among many others, ‘‘Yummy

Yummy Yummy’’ by Ohio Express, ‘‘Simon Says’’ by 1910 Fruitgum

Company, and ‘‘Sugar Sugar’’ by the Archies. The genre peaked in

1969, but the tradition continued into the 1990s with such groups as

Hanson that appealed to the pre-teen market.

—Timothy Berg

F

URTHER READING:

Miller, Jim, editor. The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock &

Roll. New York, Rolling Stone Press, 1980.

Various Artists. Bubblegum Classics, Vol. 1-5. Varese Sarabande, 1995.

Buck, Pearl S. (1892-1973)

Author and humanitarian activist Pearl S. Buck almost single-

handedly created the prism through which an entire generation of

Americans formed its opinion about China and its people. Her work

and personality first came to the attention of a wide audience in 1931,

with the publication of her signature novel The Good Earth, based on

her experiences growing up in China with a missionary family during

the convulsive period from the Boxer Rebellion to the civil wars of the

1920s and 1930s. She wrote more than seventy other books—many of

which were best-sellers and Book-of-the-Month Club selections—

and hundreds of pieces in many genres, including short stories, plays,

poetry, essays, and children’s literature, making her one of the

century’s most popular writers. As a contributing writer to Asia

magazine (later Asia and the Americas), published by her second

husband, Richard Walsh, she brought a precocious ‘‘Third-World’’

consciousness to Americans by advocating an end to colonialism

while advancing the causes of the peasantry, especially women.

In 1938, Buck became the first of only two American women to

win the Nobel Prize for literature, though her books have fallen out of

favor with critics and academicians and she is rarely anthologized

today or studied in college literature courses. Her work has remained

a sentimental favorite of millions of readers around the world.

Contemporary Chinese-American writer Maxine Hong Kingston has

credited Buck with acknowledging Asian voices, especially those of

women, for the first time in Western literature. Biographer Peter Conn

declared in his 1996 study Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography that

‘‘never before or since has one writer so personally shaped the

imaginative terms in which America addresses a foreign culture. For

two generations of Americans, Buck invented China.’’ He quoted

historian James Thomson’s belief that Buck was ‘‘the most influen-

tial Westerner to write about China since thirteenth-century Marco

Polo.’’ Living in the United States during the second half of her life,

BUCK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

376

Pearl S. Buck

Buck was prominent in many progressive social movements, lending

her support to causes on behalf of disarmament, immigrants, women,

and racial minorities. Her outspoken activism, especially during and

after World War II, earned her an FBI dossier and the ire of

McCarthyists in the 1950s.

Pearl Buck was born Pearl Sydenstricker in Hillsboro, West

Virginia, on June 26, 1892, the daughter of Presbyterian missionaries

Absalom and Carie (Stulting) Sydenstricker, who were then on leave

from their post in China, to which they returned when Pearl was three

months old. Except for a brief foray in the States around the time of

the Boxer Rebellion, Pearl stayed in China until 1910, when she

enrolled in Randolph-Macon Woman’s College in Virginia, graduat-

ing as president of the class of 1913 and remaining as a teaching

assistant in psychology. She returned to China soon afterwards to care

for her ailing mother and remained there for most of the next twenty

years, during which time she took an avid interest in the daily lives of

Chinese peasants as well as the intellectuals’ movements for reforms

in literature and society that, in 1919, coalesced in the May 4

movement. Since she was fluent in Chinese language and culture,

Buck came to support the new wave in Chinese literature, a dissident

movement that called for a complete reconstruction of literature as a

way of promoting political and social change. In 1917, she had

married John Lossing Buck, an agricultural missionary, and moved

with him to Nanhsuchou, where she experienced firsthand the back-

wardness and poverty that would later find its way into the pages of

her fiction and nonfiction.

During the 1920s, Buck began interpreting China to American

readers through articles she wrote for the Atlantic, the Nation, and

other magazines. In 1924 she and her husband returned briefly to the

United States, both to pursue masters degrees at Cornell University,

hers in English and his in agricultural economics. Using a masculine

pen name, she won a prestigious campus literary prize for her essay

‘‘China and the West,’’ which criticized China’s traditional treatment

of women and girls while praising the achievements of Chinese art

and philosophy. The couple returned to Nanjing but were forced to

flee in 1927 during the Chinese civil war, taking refuge in Japan for a

while before returning to Shanghai. They were soon alienated by the

corruption and elitism of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang and by the

violence of Mao Zedong’s Communists. Motivated by a need to find a

suitable school for their mentally retarded daughter, Carol, the Bucks

returned to the United States in 1929 thanks to a Rockefeller Founda-

tion grant for John’s agricultural survey work. Pearl had already

begun to write novels about her experiences in China; the first of

them, East Wind, West Wind, was published by John Day in 1930. It

was among the first serious novels to interpret to American readers

the upheavals in traditional Chinese society, particularly in terms of

the changing role of women. On March 2, 1931, John Day published

Buck’s second novel, The Good Earth. The book became an over-

night sensation after Will Rogers lauded it on the front page of the

New York Times as ‘‘not only the greatest book about a people ever

written but the best book of our generation.’’ The Good Earth won

Buck a Pulitzer Prize in 1932, was translated into some thirty

languages, and was made into a popular motion picture. MGM’s offer

of $50,000 for the film rights was at the time the most lucrative deal

between an author and a Hollywood studio. Buck’s always precarious

financial situation improved considerably, and she found herself

much in demand as a lecturer and writer. She moved to the United

States permanently in 1932, the year John Day published her third

novel, Sons.

Like a prophet without honor in her own country, however, Buck

soon found herself the target of criticism from church leaders who

objected to the absence of a positive Christian message in The Good

Earth, as when a Presbyterian bureaucrat complained to Buck that

‘‘the artist in you has apparently deposed the missionary.’’ A year

later, in the presence of church officials at a Presbyterian women’s

luncheon in New York, she courageously denounced typical mission-

aries as ‘‘narrow, uncharitable, unappreciative, ignorant’’ in their

zeal for conversion, which put her at the center of an already gathering

storm critical of the missionary endeavor. Her break with denomi-

national orthodoxy was sealed in an article she wrote for Cos-

mopolitan, ‘‘Easter, 1933,’’ in which she repudiated dogmatism

and found humanitarian parallels between the teachings of Christ

and the Buddha; shortly after its publication, she resigned as a

Presbyterian missionary.

Buck continued writing fiction about China, and John Day

published her fourth novel, The Mother, in 1934, about the tribula-

tions of an unnamed Chinese peasant widow abandoned by her

husband and condemned by custom to a life of loneliness and sexual

frustration. In June of 1935, she got a Reno divorce from her husband

and, that same day, married Richard Walsh, her editor/publisher at

John Day. Buck had already begun to assume a significant role in the

BUCK ROGERSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

377

company’s affairs, especially in the editorial direction of Asia maga-

zine, which he had just taken over. With Walsh and Buck at its helm,

the periodical quickly changed from being a travel-oriented publica-

tion to a serious journal of ideas, with contributions by Lin Yutang,

Bertrand Russell, Rabindranath Tagore, Margaret Mead, Agnes

Smedley, and other noted writers and intellectuals. As a contributor,

Pearl Buck expressed her growing dissatisfaction with Chiang Kai-

shek’s policies while remaining anti-Communist herself.

During this period, the Walshes adopted four children, and in

1936 John Day published Buck’s memoir of her mother, The Exile. A

commercial as well as critical success, it was soon followed with

Fighting Angel, a memoir of her father. As a boxed set, the two were

offered as a joint Book-of-the-Month Club selection, The Flesh and

the Spirit. It was during this period that Buck began to ally herself

with American pacifist and disarmament groups, such as the Wom-

en’s International League for Peace and Freedom, as well as with the

Urban League and other groups advocating racial desegregation. She

also became increasingly concerned about the rise of Nazism and the

plight of Jews in Europe. The couple founded the China Emergency

Relief Committee, with Eleanor Roosevelt as its honorary chair, to

give humanitarian aid to victims of Japanese aggression in East Asia.

In 1938, Pearl Buck became the fourth woman and the first

American woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, a

decision that was greeted with derision in some American literary

circles, who felt Buck was too much of a ‘‘popular’’ writer to deserve

such an honor. When told of the award, she remarked in Chinese ‘‘I

don’t believe it,’’ adding in English, ‘‘It should have gone to

[Theodore] Dreiser.’’ While the prize was given for the entire body of

her work, the twin biographies of her parents were specifically cited

as her finest works. In her Nobel lecture, she argued that the great

Chinese novels should be regarded as highly in the West as the works

of Dickens or Tolstoy.

Just before the United States became involved in World War II,

Walsh and Buck founded the East and West Association ‘‘to help

ordinary people on one side of the world to know and understand

ordinary people on the other side.’’ This group, and the other non-

governmental organizations in which they were involved, helped

solidify a network of American business people and intellectuals that

was instrumental in developing American attitudes toward Asia in the

postwar period. Also during the 1940s, Buck became more deeply

interested in women’s issues at home. In 1941 she published Of Men

and Women, a collection of nine essays on gender politics that

challenged the patriarchal hegemony in American society. A New

York Times critic even argued that Buck’s view of gender resembled

that of Virginia Woolf’s. Resisting the ‘‘official’’ stance of main-

stream women’s organizations, Buck became a fervid supporter of

more radical women’s-rights groups that first proposed the Equal

Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, though Buck still

hesitated to call herself ‘‘a feminist or active in women’s suffrage.’’

Buck’s novel Dragon Seed was published in 1942, after the

United States had entered the Pacific War. The book, which called

particular attention to war as an example of savagery against women,

drew much of its narrative from actual events, such as the Japanese

rape of Nanjing, and it also urged its Chinese protagonists to endure

privation and create a new, more humanitarian society. At home, she

was among the most vociferous critics of segregation and racial

discrimination, which she thought unworthy of the noble cause for

which American sacrifices were being made. She supported the

growing claims of African Americans for equality, and emerged as a

strong proponent of the repeal of exclusion laws directed against

Chinese immigration. Buck had been under FBI surveillance since

her pacifist activities in the 1930s, and her appearance at rallies with

such leftist activists as Paul Robeson and Lillian Hellman earned her a

300-page dossier, one of the longest of any prominent writer. During

the postwar era, Buck was accused of membership in several ‘‘Com-

munist Front Organizations.’’

Although she continued to write, little of her later fiction

achieved the literary stature of her earlier work, with the possible

exception of Imperial Woman (1956), a fictionalized account of the

last Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi, who had ruled China during Buck’s

childhood there. Her autobiography, My Several Worlds, was pub-

lished in 1954; a sequel, A Bridge to Passing, appeared in 1962. Her

activism continued unabated, however, and she founded Welcome

House, an adoption agency for interracial children, especially for

Amerasians, which placed children with adoptive parents regardless

of race. During the 1960s, her reputation escaped untarnished when

her companion, Ted Harris—her husband, Richard Walsh, had died in

1953—was vilified in the press for alleged irregularities and personal

wrongdoing in connection with the Welcome House organization.

In the early 1970s, when relations with Communist China began

to thaw, Buck hoped to visit China with the Nixon entourage, but her

request for a visa was turned down by the Chinese government who

accused her works of displaying ‘‘an attitude of distortion, smear and

vilification towards the people of new China and its leaders.’’ It was

obvious that her record of leftist activism did not engender support

within the Nixon administration. She became ill soon afterwards, and

after a bout with gall bladder complications, she died on March 6, 1973.

—Edward Moran

F

URTHER READING:

Conn, Peter. Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography. New York,

Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Stirling, Nora. Pearl Buck. Piscataway, New Century Publishers, 1983.

Buck Rogers

Long before Star Trek and Star Wars, there was Buck Rogers,

the first comic strip devoted to science fiction. Debuting early in

1929, it introduced readers to most of its stock features, including

rocket ships, space travel, robots, and ray guns, concepts considered

by most to be wildly improbable, if not downright impossible. A

graduate of a pulp fiction magazine, Anthony ‘‘Buck’’ Rogers served

as a sort of ambassador for the science fiction genre, presenting many

of its premises, plots, and props to a mass audience. Indeed, it was

Buck Rogers that inspired a wide range of people, from creators of

comic book superheroes and future astronauts to scientists and Ray

Bradbury. Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, as the strip was initially

titled, helped introduce the United States to the possibilities of the

future, such as space travel and the atomic bomb, while simultaneous-

ly offering quite a few wild and exciting adventures.

Buck Rogers was the creation of Philadelphia newspaperman

Philip Francis Nowlan, who was forty when he sold his first science

fiction story to Amazing Stories. Titled ‘‘Armageddon—2419 A.D.,’’

it appeared in the August 1928, issue, and featured twenty-nine-year-

old Anthony Rogers, who got himself trapped in a cave-in at an

BUCK ROGERS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

378

abandoned Pennsylvania coal mine. Knocked out by an accumulation

of radioactive gases, Rogers slept for five centuries and awakened to a

world greatly changed. America was no longer the dominant power in

the world. In fact, the nation was a ‘‘total wreck—Americans a hunted

race in their own land, hiding in dense forests that covered the

shattered and leveled ruins of their once-magnificent cities.’’ The

world was ruled by Mongolians, and China was the locus of power.

Finding that the Han Airlords ruled North America, Rogers joined the

local guerilla movement in its fight against the conquerors, and took

advantage of 25th century anti-gravity flying belts and rocket guns, as

well as his own knowlege, to concoct winning strategies against them.

His partner was Wilma Deering, destined to be the woman in his

life, who he met soon after emerging from the mine. A dedicated

freedom fighter, Wilma was considerably more competent and active

than most comparable female science fiction characters of the time.

Rogers and Wilma, along with their other new comrades, saved

America in Nowlan’s sequel, ‘‘The Airlords of Han,’’ which ap-

peared in Amazing Stories the following year. By that time, Anthony

Rogers, newly-named Buck, was the hero of his own comic strip.

John F. Dille, who ran his own newspaper feature syndicate in

Chicago, noticed Nowlan’s initial story in Amazing Stories, and

encouraged him to turn it into a comic strip, ‘‘a strip which would

present imaginary adventures several centuries in the future—a strip

in which the theories in the test tubes and laboratories of the scientists

could be garnished up with a bit of imagination and treated as

realities.’’ Dille picked artist Dick Calkins to work with Nowlan, who

was already on the syndicate staff and had been trying to interest his

boss in a strip about cavemen and dinosaurs. Apparently assuming

that someone who could depict the dim past ought to be able to do the

same for the far future, Dille put Calkins on the team. Buck Rogers in

the 25th Century, a daily strip at first, began on Monday, January 7,

1929, the same day, coincidentally, that the Tarzan comic strip

was launched.

Readers responded favorably to Buck Rogers, and it began

picking up papers across the country. One early fan was a young

fellow in the Midwest by the name of Ray Bradbury. Many years

later, he recalled the impact that the early strips had on him: ‘‘What,

specifically, did Buck Rogers have to offer that instantly ’zapped’ us

into blind gibbers of love? Well, to start out with mere trifles—rocket

guns that shoot explosive bullets; people who fly through the air with

’jumping belts’; ’hovercrafts’ skimming over the surface of the earth;

disintegrators which destroyed, down to the meanest atom, anything

they touched; radar-equipped robot armies; television-controlled

rockets and rocket bombs; invasions from Mars; the first landing on

the Moon.’’

Among the regular characters, in addition to Buck and Wilma,

were Dr. Huer, scientific genius, inventor, and mentor to Buck; Black

Barney, a reformed air pirate; Killer Kane, slick-haired traitor and

recurrent villain; and Buddy Deering, teenage brother of Wilma.

When a Sunday page was added early in 1930, it was devoted chiefly

to Buddy’s adventures. It was intended to appeal to youthful readers

who supposedly made up the majority audience for Sunday funnies.

Buddy spent much of his time on Mars, where he was often involved

with young Princess Aura of the Golden People. In separate daily

sequences, Buck also journeyed to the Red Planet, but concentrated

on battling the evil Tiger Men. The Martian equivalent of the

Mongols, the Tiger Men had come to earth in their flying saucers to

kidnap human specimens. When they grabbed Wilma for one of their

experiments, Buck designed and built the world’s first interplanetary

rocket ship so that he could rescue the victims who had been taken to

Mars. ‘‘Roaring rockets!’’ he vowed. ‘‘We’ll show these Martians

who’s who in the solar system!’’

Astute readers in the 1930s may have noticed that the Sunday

pages were considerably better looking than the daily strips. That was

because a talented young artist named Russell Keaton was ghosting

them. He remained with the feature for several years. When he left to

do a strip of his own, he was replaced by another young ghost artist,

Rick Yager. Buck Rogers, especially on Sundays, was plotted along

the lines of a nineteenth-century Victorian picaresque novel. There

was a good deal of wandering by flying belt, rocket ship, and on foot.

Characters drifted in and out, appeared to be killed, but showed up

again later on after having assumed new identities. Reunions and

separations were frequent. The strip’s trappings, however, were far

from Dickensian, offering readers the latest in weapons, modes of

transportation, and lifestyles of the future. By 1939, the atomic bomb

was appearing in the strip. With the advent of World War II, most of

the villains were again portrayed as Asians.

Buck Rogers also played an important role in the development of

the comic book. A reprint of a Buck Rogers comic book was used as a

premium by Kellogg’s in 1933, which was before modern format

comic books had ever appeared on the newsstands. In 1934, Famous

Funnies, the first regularly-issued monthly comic, established the

format and price for all comic books to follow. The Buck Rogers

Sunday pages, usually four per issue, began in the third issue. It also

seems likely that Buck Rogers and his associates, who were among

the first flying people to be seen in comic books, had an influence on

the flying superheroes who came along in the original material funny

books of the later 1930s.

Almost as impressive as Buck’s daring exploits 500 years in the

future, was his career as a merchandising star during the grim

Depression era. In 1932, a Buck Rogers radio show began airing,

heard every day in fifteen-minute segments and sponsored by Kellogg’s.

The serial was heard in various forms throughout most of the decade

and into the next. In 1933, the first Big Little Book devoted to the

futuristic hero was printed. Buck Rogers was marketed most success-

fully in the area of toys. Commencing in 1934, Daisy began manufac-

turing Buck Rogers rocket pistols; that same year the Louis Marx

company introduced a toy rocket ship. The zap guns were especially

popular, so much so that Daisy began producing them at night and on

Saturdays to meet the demand.

Buck Rogers conquered the silver screen in the 1930s. Universal

released a twelve-chapter serial in 1939, with Buster Crabbe as Buck,

and Constance Moore as Wilma. Anthony Warde, who made a career

of playing serial heavies, was Killer Kane. Not exactly a gem in the

chapter play genre, Buck Rogers took place on Earth and Saturn. The

serial was later condensed into a 101-minute feature film. Under

the title Destination Saturn, it occasionally shows up on late-

night television.

Nowlan was removed from the strip shortly before his death in

1940, and Calkins left in 1947. Rick Yager carried on with the Sunday

pages and the dailies before Murphy Anderson took over. By the late

1950s, George Tuska, also a graduate of the comic books, was

drawing both the Sunday and the daily strips. Science fiction writers

such as Fritz Leiber and Judith Merrill provided scripts. The Sunday

strip ended in 1965, and the daily two years later. But Buck Rogers

was not dead.

He returned, along with Wilma and Doc Huer, in a 1979 feature

film that starred Gil Gerard. That production led to a television series

and another comic strip, written by Jim Lawrence, drawn by Gray