Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENTENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

519

King, Jr., Martin Luther. Letter from the Birmingham Jail. San

Francisco, Harper San Francisco, 1994.

Thoreau, Henry David. Civil Disobedience. 1866. Boston, D. R.

Godine, 1969.

van den Haag, Ernest. Political Violence and Civil Disobedience.

New York, Harper & Row, 1972.

Zashin, Elliot M. Civil Disobedience and Democracy. New York,

Free Press, 1972.

Civil Rights Movement

The African-American struggle for civil rights marks a turning

point in American history because it represents the period when

African Americans made their entry into the American mainstream.

Although the focus of the long persistent drive for civil rights was

centered around political issues such as voting, integration, educa-

tional opportunities, better housing, increased employment opportu-

nities, and fair police protection, other facets of American life and

culture were affected as well. Most noticeably, African Americans

came out of the civil rights movement determined to define their own

distinct culture. New styles of politics, music, clothing, folktales,

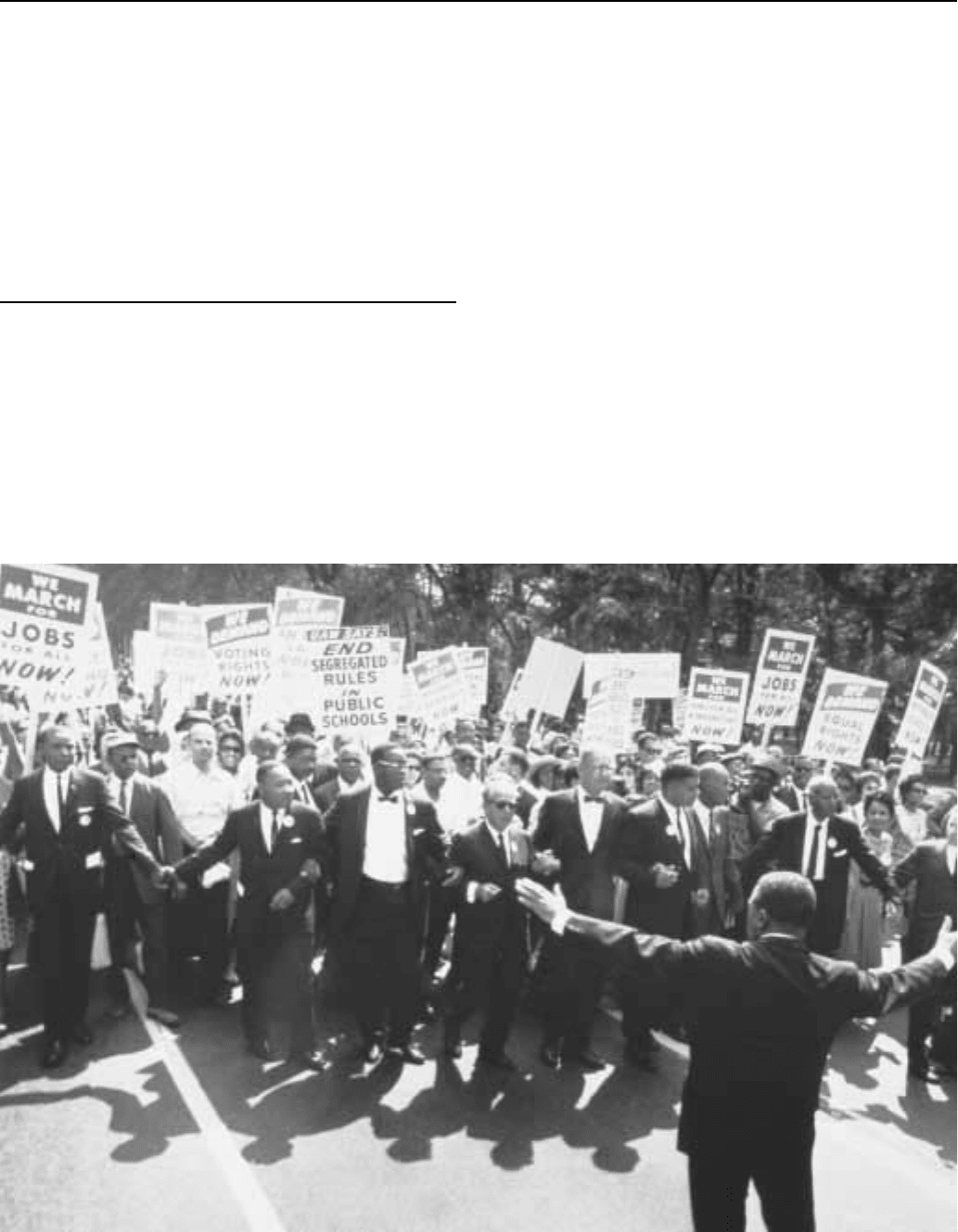

A protest for Civil Rights.

hairstyles, cuisine, literature, theology, and the arts were all evident at

the end of the civil rights movement.

Although African Americans have a long tradition of protest

dating back to the seventeenth century, the mid-1950s represented a

turning point in the black struggle for equal rights. With the historic

Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision that outlawed

the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson doctrine of ‘‘Separate But Equal,’’

African Americans realized that the time was right to end all vestiges

of Jim Crow and discrimination. On the heels of Brown, black

Southerners undertook battles to achieve voting rights and integra-

tion, under the broad leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr. Through

marches, rallies, sit-ins, and boycotts, they were able to accomplish

their goals by the late 1960s. With voting rights and integration won

in the South, African Americans next shifted their attention to the

structural problems of northern urban blacks. However, non-violent

direct-action was not the preferred tool of protest in the North where

the self-defense message of Malcolm X was popular. Rather, the

method of protest was urban unrest, which produced very few

meaningful gains for African Americans other than the symbolic

election of black mayors to large urban centers.

Immediately, the civil rights movement ushered in a new black

political culture. With the right to vote won in 1965 with the passage

of the Voting Rights Act, African Americans now began to place a

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

520

tremendous emphasis on political participation. Throughout the South

African Americans went to the polls in large numbers seeking to elect

representatives that would best represent their interests. In the North

where the right to vote had been in existence since the mid-nineteenth

century, a different type of political culture emerged. As a result of the

civil rights movement black voters in the North began to move away

from the idea of coalition building with white liberals, preferring

instead to establish all-black political organizations. These clubs

would not only attack the conservativeness of the Republican Party

but they would also begin to reassess their commitment to the

democratic party at the local, state, and national level. In essence, the

race was moving toward political maturity; no longer would their

votes be taken for granted.

Another aspect of the nascent black political culture was a re-

emergence of black nationalism which was re-introduced into Ameri-

can society by Malcolm X. While a spokesman for the Nation of

Islam, Malcolm X made African Americans feel good about them-

selves. He told them to embrace their culture and their heritage, and he

also spoke out openly against white America. Via his autobiography

and lectures, Malcolm X quickly emerged as the instrumental figure

in this renewed black consciousness. Shortly after his assassination in

1965, the proprietors of black culture immediately gave Malcolm

deity status. His name and portrait began to appear everywhere:

bumper stickers, flags, T-shirts, hats, and posters. Although Malcolm

popularized this new revolutionary frame of mind, by no means did he

have a monopoly on it. Throughout the 1960s African Americans

spoke of black nationalism in three main forms: territorial, revolu-

tionary, and cultural. Territorial nationalists such as the Republic of

New Afrika and the Nation of Islam, called for a portion of the United

States to be partitioned off for African Americans as payment for

years of slavery, Jim Crow, and discrimination. But they insisted that

by no means would this settle the issue. Instead, this would just be

partial compensation for years of mistreatment. Revolutionary na-

tionalists such as the Black Panther Party sought to overthrow the

capitalist American government and replace it with a socialist utopia.

They argued that the problems faced by African Americans were

rooted in the capitalist control of international economic affairs. Thus,

the Black Panthers viewed the black nationalist struggle as one of

both race and class. Lastly, the cultural nationalism espoused by

groups such as Ron Karenga’s US organization sought to spark a

revolution through a black cultural renaissance. In the eyes of his

supporters, the key to black self-empowerement lay in a distinct black

culture. They replaced European cultural forms with a distinct Afro-

centric culture. One of Karenga’s chief achievements was the devel-

opment of the African-American holiday ‘‘Kwanzaa.’’ Kwanzaa was

part of a broader theory of black cultural nationalism which suggested

that African Americans needed to carry out a cultural revolution

before they could achieve power.

One of the most visible effects of the civil rights movement on

American popular culture was the introduction of the concept of

‘‘Soul.’’ For African Americans of the 1960s, Soul was the common

denominator of all black folks. It was simply the collective thread of

black identity. All blacks had it. In essence, soul was black culture,

something separate and distinct from white America. No longer

would they attempt to deny nor be ashamed of their cultural heritage;

rather they would express it freely, irrespective of how whites

perceived it. Soul manifested itself in a number of ways: through

greetings, ‘‘what’s up brother,’’ through handshakes, ‘‘give me some

skin,’’ and even through the style of walk. It was no longer acceptable

to just walk, one who had soul had to ‘‘strut’’ or ‘‘bop.’’ This was all a

part of the attitude that illustrated they would no longer look for

white acceptance.

One of the most fascinating cultural changes ushered in by the

civil rights movement was the popularity of freedom songs, which at

times were organized or started spontaneously during the midst of

demonstrations, marches, and church meetings. These songs were

unique in that although they were in the same tradition as other protest

music, this was something different. These were either new songs for

a new situation, or old songs adapted to the times. Songs such as ‘‘I’m

Gonna Sit at the Welcome Table,’’ ‘‘Everybody Says Freedom,’’

‘‘Which Side Are You On,’’ ‘‘If You Miss Me at the Back of the

Bus,’’ ‘‘Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,’’ and ‘‘Ain’t Scared of Your

Jails,’’ all express the feelings of those fighting for black civil rights.

While these songs were popularized in the South, other tunes such as

‘‘Burn, Baby, Burn,’’ and the ‘‘Movement’s Moving On,’’ signaled

the movements shift from non-violence to Black Power. Along with

freedom songs blacks also expressed themselves through ‘‘Soul

music,’’ which they said ‘‘served as a repository of racial conscious-

ness.’’ Hits such as ‘‘I’m Black and I’m Proud,’’ by James Brown,

‘‘Message from a Black Man,’’ by the Temptations, Edwin Starrs’s

‘‘Ain’t It Hell Up in Harlem,’’ and ‘‘Is It Because I’m Black’’ by Syl

Johnson, all testified to the black community’s move toward a

cultural self-definition.

African Americans also redefined themselves in the area of

literary expression. Black artists of the civil rights period attempted to

counter the racist and stereotyped images of black folk by expressing

the collective voice of the black community, as opposed to centering

their work to gain white acceptance. Instrumental in this new ‘‘black

arts movement,’’ were works such as Amiri Baraka’s Blues People,

Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, and Dutchman. These

works illustrate the distinctiveness of black culture, while simultane-

ously promoting race pride and unity.

The black revolution was principally the catalyst for a new

appreciation of black history as well. Prior to the civil rights move-

ment, the importance of Africa in the world and the role of African

Americans in the development of America was virtually ignored at all

levels of education, particularly at the college and university level.

Whenever people of African descent were mentioned in an education-

al setting they were generally introduced as objects and not subjects.

However, the civil rights movement encouraged black students to

demand that their history and culture receive equal billing in acade-

mia. Students demanded black studies courses taught by black

professors. White university administrators reluctantly established

these courses, which instantly became popular. Predominantly white

universities and colleges now offered classes in Swahili, Yoruba,

black history, and black psychology to satisfy the demand. Due to the

heightened awareness, all black students were expected to enroll in

black studies courses, and when they didn’t, they generally had to

provide an explanation to the more militant factions on campus.

Students not only demanded black studies courses but they also

expressed a desire for colleges and universities that would be held

accountable to the black community. Traditional black colleges and

universities such as Howard, Spelman, and Fisk, were now viewed

with suspicion since they served the racial status quo. Instead, schools

such as Malcolm X College of Chicago and Medgar Evers College of

CUNY became the schools of choice since they were completely

dedicated to the black community.

The 1960s generation of African Americans also redefined

themselves in the area of clothing. Again, they were seeking to create

something unique and distinct from the white mainstream. The new

CIVIL WAR REENACTORSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

521

attire consisted of wide-brimmed hats, long full-cut jackets, platform

shoes, bell-bottoms, leather vests, and wide-collar shirts. These

outfits were complimented by African-like beads, earrings, belts,

medallions, and bracelets. However, the more culturally conscious

rejected all types of western culture in favor of dashikis, robes, and

sandals. In response to these new cultural tastes clothing companies

began specifically targeting the black consumer by stating that their

items were designed to meet the body style of blacks. To complement

the new clothing look African Americans also began to reject the

European standard of beauty. Whereas African Americans were once

ashamed of their full lips, broad nose, high cheekbones, and coarse

hair, they now embraced them. Black women took hair straighteners

and hot combs out of their bathrooms and began to wear ‘‘naturals,’’

cornrows, and beads, which many considered to be the most visible

sign of black self-expression.

Interestingly enough, black Americans also experienced a slight

shift in eating tastes. Although collard greens, ‘‘chitlins,’’ catfish,

pigs feet, and fried-chicken had been a staple in the black diet for

years, it was now labeled ‘‘soul food,’’ because it provided a cultural

link to the African ancestral homeland.

African-American folktales took on a whole new importance

during the civil rights movement as the famed ‘‘trickster tales’’

became more contemporary. Folklorists made the black hero superior

to that of other culture’s, by stressing its mental agility, brute physical

strength, and sexual prowess. These heroes also reversed the tradi-

tional socio-economic arrangements of America as well. Characters

such as Long-Shoe Sam, Hophead Willie, Shine, and Dolemite, all

used wit and deceit to get what they wanted from white America. In

the eyes of black America, traditional heroes such as Paul Bunyan

and Davy Crockett were no match for this new generation of

black adventurers.

The civil rights movement also encouraged blacks to see God,

Jesus, and Mary as black. As their African ancestors, these deities

would assist African Americans in their quest for physical, mental,

and spiritual liberation. By stressing that a belief in a white God or

Jesus fostered self-hatred, clergyman such as Rev. Albert Cleague of

Detroit sought to replace the traditional depiction of God and Jesus

with a black image. Throughout the country black churches followed

Cleague’s lead as they removed all vestiges of a white Christ in favor

of a savior they could identify with. Followers of this new Black

Christian Nationalism also formulated a distinct theology, in which

Jesus was viewed as a black revolutionary who would deliver African

American people from their white oppressors.

As with other facets of black popular culture, television also

witnessed a change as a result of the black revolution. With the

renewed black consciousness clearly evident, the entertainment in-

dustry sought to capitalize by increasing the visibility of black actors

and actresses. Whereas in 1962 blacks on TV were only seen in the

traditional stereotyped roles as singers, dancers, and musicians, by

1968 black actors were being cast in more positive roles, such as Greg

Morris in Mission Impossible, Diahann Carroll in Julia, Clarence

Williams III in the Mod Squad, and Nichelle Nichols, who starred as

Uhura in Star Trek. While these shows did illustrate progress, other

shows such as Sanford and Son and Flip Wilson’s Show all reinforced

the traditional black stereotype. In the film industry, Hollywood

would not capitalize on the renewed black consciousness until the

early 1970s with blaxploitation films. In the mid-1960s however,

African Americans were continually portrayed as uncivilized, barbar-

ic, and savage, in movies such as The Naked Prey, Dark of the Sun,

and Mandingo.

The principal effect of the civil rights movement on American

popular culture was a renewed racial consciousness not witnessed

since the Harlem Renaissance. This cultural revolution inspired

African Americans to reject the white aesthetic in favor of their own.

Although they had fought and struggled for full inclusion into

American society, the civil rights drive also instilled into African

Americans a strong appreciation of their unique cultural heritage.

Through new styles of music, clothing, literature, theology, cuisine,

and entertainment, African Americans introduced a completely new

cultural form that is still evident today.

—Leonard N. Moore

F

URTHER READING:

Anderson, Terry. The Movement and the Sixties: Protest in America

from Greensboro to Wounded Knee. Oxford, Oxford University

Press, 1995.

Dickstein, Morris. Gates of Eden: American Culture in the Sixties.

New York, Basic Books, 1977.

Seeger, Pete, and Bob Reiser. Everybody Says Freedom. New York,

W.W. Norton and Company.

Van Deburg, William. Black Camelot: African-American Culture

Heroes in Their Times, 1960-1980. Chicago: University of Chica-

go Press, 1997.

———. New Day in Babylon. Chicago, University of Chicago

Press, 1992.

Civil War Reenactors

Reenactors are those people whose hobby involves dressing in

the manner of soldiers from a particular period of time in order to

recreate battles from a famous war. Those individuals who choose to

restage Civil War battles form the largest contingent of reenactors.

They are part of a larger group of Civil War buffs who actively

participate in genealogy research, discussion groups, and roundtables.

The American Civil War divided the country in bitter warfare from

1861 to 1865 but its legacy has endured long since the fighting ceased.

The war wrought extensive changes which shaped United States

society and its inhabitants. Historian Shelby Foote, renowned for his

participation in Ken Burns’ popular PBS series The Civil War,

observes that ‘‘any understanding of this nation has to be based, and I

mean really based, on an understanding of the Civil War. I believe that

firmly. It defined us.’’ The importance of the Civil War in American

culture and memory makes it significant in popular culture. The Civil

War has a long history of serving ‘‘as a vehicle for embodying

sentiments and politics in our day.’’ The Civil War has therefore been

entwined with popular culture before, during, and since its actual

battles occurred as popular cultural producers fought to determine

how its meaning would apply to postwar society.

Civil War reenactments range in size from small one-day

skirmishes to large encampments like the 125th Anniversary of

Gettysburg that attracted 12,000 soldiers and 100,000 audience

members. The larger events are great tourist attractions that feature

concerts, lectures, exhibitions, encampments, and demonstrations of

camp life, hospitals, Civil War fashions, and other topics. These large

reenactments are often cosponsored by the National Park Service and

local museums as they involve numerous volunteers and intensive

CIVIL WAR REENACTORS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

522

A reenactment of the battle at Andersonville, Georgia.

preparations. The battles themselves are choreographed events where

the soldiers shoot blanks and show a great concern for the safety of all

involved. The reenactors who stage these events are part of the

amateur and living history movement that encourages direct audience

interaction and has enjoyed increasing popularity in the late twentieth

century. Living history museums rose in popularity in the United

States in the 1920s with the founding of automobile giant Henry

Ford’s Greenfield Village in Michigan and John D. Rockefeller’s

Colonial Williamsburg village in Virginia. The majority of the people

in the United States learn their history from popular culture rather

than academic books and classes. Popular cultural forms of history

provide their audiences with forms, images, and interpretations of

people and events from America’s past. Their popularity makes their

views on history widely influential. Civil War reenactors understand

that popular history is a valuable form of communication. They view

living history as a valuable education tool, viewing their participation

as a learning experience both for them and for their audience.

The first group to reenact the Civil War consisted of actual

veterans belonging to a society known as the Grand Army of the

Republic. These late-nineteenth-century encampments were places

where these ex-soldiers could affirm the passion and the sense of

community to fellow soldiers that their wartime experiences engen-

dered. Veterans also showed their respect for the former enemies who

had endured the same indescribable battle-time conditions. Commu-

nity sponsored historical pageants replaced the early reenactments as

the veterans largely died off, until the fragmentation of society after

World War II broke apart any strong sense of community. Reenacting

emerged in its late-twentieth-century form during the 1960s Civil

War centennial commemorations. The battles staged during this

period found a receptive audience. Public enthusiasm for reenactments

faded in the late 1960s and 1970s as the result of a national mood of

questioning blind patriotism and American values. The phenomenal

popularity of the living history movement in the 1980s, however,

quickly led to a resurgence of Civil War reenacting.

Twentieth-century Civil War reenactors have found themselves

involved in the controversies between amateur and professional

historians. Academics have accused the reenactors of engaging in

cheap theatrics to capture their audience’s interest and questioned the

morality of the use of actual battlefields as reenactment sites. They

have also been criticized for their sentimentalized historical portraits.

Civil War reenactors have a highly developed sense of culture

among themselves. Most are generally white males in their thirties

and are very passionate about the endeavor. There are a few women

and African-Americans who participate, but they often meet with

hostility. Reenactors are mostly not academic historians but are

usually quite knowledgeable, conducting considerable research to

CLAIROL HAIR COLORINGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

523

create their historical characters and outfit themselves in meticulous

detail. They categorize their fellow reenactors by a tiered system that

demonstrates their amount of dedication to the activity and to the goal

of complete authenticity. ‘‘Farbs’’ are those reenactors who lack

seriousness and attention to detail and are usually more interested in

the social and alcoholic aspects of the encampments. ‘‘Authentic’’

reenactors concern themselves with detail but are willing to allow

some twentieth-century comforts whereas ‘‘hard core’’ reenactors

share a precise and uncompromising commitment to accuracy. ‘‘Hard

core’’ reenactors are also those who wish to ban women from

participation despite the fact that many women disguised as men

actually fought in the Civil War. Reenacting involves a great deal of

preparation time as participants must obtain proper clothing and

hardware and memorize complicated drills for public exhibition.

Magazines such as the North-South Trader’s Civil War, Civil War

Book Exchange and Collector’s Newspaper, Blue and Gray, Ameri-

ca’s Civil War, Civil War News, Civil War Times, and the Camp

Chase Gazette cater to the large market of Civil War buffs and

reenactors looking for necessary clothing and equipment. The reenactor

must also make every effort to stay in character at all times, especially

when members of the public are present.

The reenactors are largely unpaid amateur history fans who often

travel great distances to participate in what can prove to be a very

expensive hobby. Many participants welcome the chance to escape

everyday life and its worries through complete absorption in the

action of staged battles, the quiet of camp life, and the portrayal of

their chosen historical character. Many also seek a vivid personal

experience of what the Civil War must have been like for its actual

participants. They are quite intense in their attempt to capture some

sense of the fear and awe that must have overwhelmed their counter-

parts in reality. They find that experiential learning provides a much

better understanding of the past than that provided by reading dry

academic works. Jim Cullen observes in that by ‘‘sleeping on the

ground, eating bad food, and feeling something of the crushing

fatigue that Civil War soldiers did, they hope to recapture, in the most

direct sensory way, an experience that fascinates yet eludes them.’’

The immediacy of the battles and surrounding camp life is part of the

hobby’s appeal. Cullen also suggests one of reenacting’s more

negative aspects in observing that certain participants seek a ritual

reaffirmation of their own past which may hide a thinly veiled racism

in the face of a growing emphasis on new multicultural pasts.

—Marcella Bush Treviño

F

URTHER READING:

Bodner, John E. Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemora-

tion, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century. Princeton, Prince-

ton University Press, 1992.

Catton, Bruce. America Goes to War: The Civil War and Its Meaning

in American Culture. Lincoln, University Press of Nebraska, 1985.

Cullen, Jim. The Civil War in Popular Culture: A Reusable Past.

Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

Hadden, R. Lee. Reliving the Civil War: A Reenactor’s Handbook.

Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, Stackpole Press, 1996.

———. Returning to the Civil War: Grand Reenactments of an

Anguished Time. Gibbs Smit, 1997.

Claiborne, Liz (1929—)

After spending 25 years in the fashion business, Liz Claiborne

became an overnight success when she opened her own dress compa-

ny in 1976. By the time she and husband Arthur Ortenberg retired in

1989, their dress company had grown into a fashion colossus that

included clothing for men and children as well as accessories, shoes,

fragrances, and retail stores. Claiborne successfully combined an

emphasis on sensible dresses with a keen intuition for the professional

woman’s desire to appear sophisticated and dressed up at the office.

Her sensibility to what people want in fashion carried over into a

successful sportswear line. Her genius as a fashion designer was

highlighted by the fact that Claiborne was one of most stable fashion

companies on the New York Stock Exchange, serving as a model for

publicly-owned fashion companies until it faltered in the 1990s.

—Richard Martin

F

URTHER READING:

Klensch, Elsa. ‘‘Dressing America: The Success of Liz Claiborne.’’

Vogue. August, 1986.

‘‘Liz Claiborne.’’ Current Biography. June, 1989.

Clairol Hair Coloring

In 1931, Lawrence M. Gelb, a chemical broker, discovered and

bought ‘‘Clairol’’ hair color in Europe to market in the United States.

From the start, he promoted Clairol with the idea that beautiful hair

was every woman’s right, and that hair color, then considered risqué,

was no different from other cosmetics. With the 1956 introduction of

‘‘Miss Clairol,’’ the first at-home hair coloring formula, Clairol hair

color and care products revolutionized the world of hair color. The

do-it-yourself hair color ‘‘was to the world of hair color what

computers were to the world of adding machines,’’ Bruce Gelb, who

worked with his father and brother at Clairol, told New Yorker

contributor Malcolm Gladwell.

The firm’s 1956 marketing campaign for a new, Miss Clairol

product ended the social stigma against hair coloring and contributed

to America’s lexicon. Shirley Polykoff’s ad copy—which read ‘‘Does

she or doesn’t she? Hair color so natural only her hairdresser knows

for sure!’’—accompanied television shots and print photos of whole-

some-looking young women, not glamorous beauties associated with

professional hair color but attractive homemakers with children. With

ads that showed mothers and children with matching hair color, Miss

Clairol successfully divorced hair coloring from its sexy image.

Moreover, women could use the evasive ‘‘only my hairdresser knows

for sure’’ to avoid divulging the tricks they used to craft an appealing

public self. For women in the 1950s, hair color was a ‘‘useful

fiction—a way of bridging the contradiction between the kind of

woman you were and the woman you were supposed to be,’’

wrote Gladwell.

Hair color soon became an acceptable image-enhancing cosmet-

ic. In 1959 Gelb’s company was purchased by Bristol Meyers, which

has continued to expand the line into the 1990s. From the decade Miss

Clairol was introduced to the 1970s, the number of American women

coloring their hair increased dramatically, from 7 to 40 percent. By

the 1990s, store shelves were crowded with many brands of at-home

CLANCY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

524

hair colorings and the image of hair coloring had changed as the

brands proliferated. Hair color was no longer something women hid.

Instead women celebrated their ability to change their look on a

whim. Supermodel Linda Evangelista would appear as a platinum

blonde one day, a redhead the next, and a brunette the next. The brand

Féria advertised hair color that didn’t pretend to be natural. Clairol’s

ads accommodated this change as well. While keeping with the image

of the-girl-next-door, Clairol’s shampoo-in color Nice ’n Easy ads

featured Julia Louis-Dreyfus, well-known as Elaine on the popular

sitcom Seinfeld, spotting women on the street and giving them public

hair colorings. Clairol had initiated an appealing formula that gave

women new freedom to shape their image as they pleased.

—Joan Leotta

F

URTHER READING:

‘‘Clairol’s Influence on American Beauty and Marketing.’’ Drug &

Cosmetic Industry. New York, August, 1996.

Gladwell, Malcolm. ‘‘True Colors.’’ New Yorker. New York, March

22, 1999, 70-81.

Clancy, Tom (1947—)

Known for his potboiling thrillers with political, military, and

espionage themes, author Tom Clancy’s influence on American

popular culture has been incalculable. Within the high-tech action

adventure that has proved so beguiling to the movie industry and its

audiences, as well as to a vast number of people who buy books of

escapist fiction, Clancy evokes a disturbing picture of the world we

live in, and has come to be regarded as the spokesman for the

American nation’s growing mistrust of those who govern them. If his

name is instantly identified with the best-selling The Hunt for Red

October (1984) and the creation of his Cold Warrior hero Jack Ryan

(incarnated on screen by Harrison Ford) in a series beginning with

Patriot Games (1992), his work is considered to have a serious

significance that transcends the merely entertaining.

On February 28, 1983, the Naval Institute Press (NIP) received a

manuscript from a Maryland insurance broker, whose only previous

writings consisted of a letter to the editor and a three-page article on

MX missiles in the NIP’s monthly magazine, Proceedings of the U.S.

Naval Institute. The arrival of the manuscript confounded the recipi-

ents. As the publishing arm of the U.S. Naval Institute, NIP is an

academic institution responsible for The Bluejackets’ Manual which,

according to them, has served as ‘‘a primer for newly enlisted sailors

and as a basic reference for all naval personnel from seaman to

admiral’’ for almost a century. NIP created an astonishing precedent

by publishing the manuscript, and the obscure insurance broker

became a world-famous best-selling author of popular genre fiction.

Clancy’s manuscript was based on the fruitless attempt of the

Soviet missile frigate Storozhedoy to defect from Latvia to the

Swedish island of Gotland on November 8,1975. The mutiny had

been led by the ship’s political officer Valeri Sablin, who was

captured, court-marshaled, and executed. In Clancy’s tale, Captain

First Rank Marko Ramius successfully defects to the United States,

not in a frigate, but in a submarine, the Red October. The Naval

Institute Press published The Hunt for Red October in October 1984,

its first venture into fiction in its long academic history. It skyrocketed

onto The New York Times best-seller list when President Reagan

pronounced it ‘‘the perfect yarn.’’ In March 1985, author and

president met in the Oval office, where the former told the latter about

his new book on World War II. According to Peter Masley in The

Washington Post, Reagan asked, ‘‘Who wins?’’ to which Clancy

replied, ‘‘The good guys.’’

Born on April 12, 1947 in Baltimore, Thomas L. Clancy, Jr.

grew up with a fondness for military history in general and naval

history in particular. In June 1969, he graduated from Baltimore’s

Loyola College, majoring in English, and married Wanda Thomas in

August. A severe eye weakness kept him from serving in the Vietnam

War, and he worked in insurance for 15 years until the colossal

success of his first novel. The book was a bestseller in both hard cover

and paperback, and was successfully filmed—although not until

1990—with an all-star cast headed by Sean Connery. Meanwhile, he

was free to continue writing, building an impressive oeuvre of both

fiction and non-fiction. In a 1988 Playboy interview, Marc Cooper

claimed that Clancy had become ‘‘a popular authority on what the

U.S. and the Soviets really have in their military arsenals and on how

war may be fought today.’’ Indeed, his novels have been brought into

use as case studies in military colleges.

In April 1989, Clancy was invited to serve as an unpaid consult-

ant to the National Space Council, and has lectured for the CIA, DIA,

and NSA. A 1989 Time magazine review added a moral dimension to

his growing public authority: ‘‘Clancy has performed a national

service of some sorts: he has sought to explain the military and its

moral code to civilians. Such a voice was needed, for Vietnam had

created a barrier of estrangement between America’s warrior class

and the nation it serves. Tom Clancy’s novels have helped bring down

this wall.’’ It is the dawning of the idea that the novel as a textual form

is slowly attempting to replace that which we conventionally labeled

‘‘history’’ that has been an important factor in the growing critical

interest in Clancy’s thrillers, dealing as they do with the politics of our

times. Whereas the ‘‘literary’’ aspect of a text is traditionally located

in its ability to deal with the ontological and existential problems of

man and being, we now find ‘‘literary’’ values in those texts that deal

with pragmatic problems: man and being in the here and now. Read

from this standpoint, Clancy’s thrillers can be seen not as an escape

from reality, but as presenting real, and relevant, issues and ex-

periences, drawing on society’s loss of trust in the great myths

of existence: truth, and the questionable value of official and

governmental assurances.

Although Clancy claims, in The Clancy Companion, that he

writes fiction ‘‘pure and simple . . . projecting ideas generally into the

future, rather than the past,’’ critics have labeled him the father of the

techno-thriller. In his novels Red Storm Rising (a Soviet attack on

NATO; 1986), Cardinal of the Kremlin (spies and Star Wars missile

defense; 1988), Clear and Present Danger (the highest selling book

of the 1980s, dealing with a real war on drugs; 1989), Debt of Honor

(Japanese-American economic competition and the frailty of Ameri-

ca’s financial system; 1994) and Executive Orders, (rebuilding a

destroyed U.S. government; 1996), the machine is hero and technolo-

gy is as dominant as the human characters. In both his fiction and non-

fiction the scenarios predominantly reflect the quality of war games.

‘‘Who the hell cleared it?’’ the former Secretary of the Navy, John

Lehman, remarked after reading The Hunt for Red October. Clancy,

whose work includes his ‘‘Guided Tour’’ series (Marine, Fighter

Wing) and the ‘‘Op-Center’’ series (created by Clancy and Steve

Pieczenik, but written by other authors), has always insisted that he

finds his information in the public domain, basing his Naval technolo-

gy and Naval tactics mostly on the $9.95 war game Harpoon.

CLARKENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

525

In November 1996 Tom Clancy and Virtus Corporation founded

Red Storm Entertainment to create and market multiple-media enter-

tainment products. It released its first game, Politika, in November

1997, the first online game ever packaged with a mass-market

paperback, introducing ‘‘conversational gaming’’ in a net based

environment. Clancy has called it ‘‘interactive history.’’ The huge

success of his books, multimedia products, and movies that are based

on his novels allowed him to make a successful $200 million bid for

the Minnesota Vikings football team in March 1998.

—Rob van Kranenburg

F

URTHER READING:

Greenberg, Martin H. The Tom Clancy Companion. New York,

Berkley Pub Group, 1992.

Clapton, Eric (1945—)

Eric Clapton, a lifelong student of the blues, has been in more

bands that he himself formed than any other guitarist in rock music.

He first distinguished himself with the group, the Yardbirds, where he

earned the ironic nickname, ‘‘Slowhand,’’ for his nimble leads. When

the Yardbirds went commercial, Clapton left them to pursue pure

blues with John Mayall, a singer, guitarist, and keyboard player who

was regarded as the Father of British Blues for his discovery and

promotion of luminary musicians in the field. Clapton proved to be

Mayall’s greatest discovery. On John Mayall’s Blues Breakers,

Featuring Eric Clapton (1966) Clapton displayed an unprecedented

fusion of technical virtuosity and emotional expressiveness, giving

rise to graffiti scribbled on walls in London saying, ‘‘Clapton

is God.’’

When jazz-trained bassist Jack Bruce joined the Blues Breakers,

Clapton grew intrigued by his improvisational style. He recruited

Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker to form the psychedelic blues-rock

power-trio Cream. They became famous for long, bombastic solos in

concert, and established the ‘‘power trio’’ (guitarist-bassist-drum-

mer) as the definitive lineup of the late 1960s, a form also assumed by

Blue Cheer, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and Rory Gallagher’s band,

Taste. Cream disbanded after four excellent studio albums, having set

a new standard for rock musicianship and Clapton, bored with the

improvisational style, became interested in composing songs.

Blind Faith, a band comprised of established musicians from

other famous bands and often called the first ‘‘supergroup,’’ was

formed by Clapton in 1969. He retained Ginger Baker, and recruited

guitarist/pianist Steve Winwood (from the recently disbanded Traf-

fic) and bassist Rick Grech. They produced only one album (Blind

Faith, 1969), for Clapton soon transferred his interest to the laid-back,

good-vibes style of Delaney and Bonnie, who had opened for Blind

Faith on tour. Delaney and Bonnie encouraged him to develop his

singing and composing skills, and joined him in the studio to record

Eric Clapton (1970). Clapton then formed Derek and the Dominos

with slide guitarist Duane Allman in 1970 and released Layla and

Other Assorted Love Songs, one of the finest blues-rock albums ever

made. Unfortunately, the band, beset with intense personal conflicts

and drug problems, was dissolved and Clapton, increasingly reliant

on heroin, became a recluse.

In 1973 Pete Townsend organized the Rainbow Concert with

Steve Winwood and other stars to bring Clapton back to his music.

Clapton kicked the heroin habit, and in 1974 resumed his solo career

with the classic 461 Ocean Boulevard. Although Layla could never be

surpassed on its own terms, 461 was a worthy follow-up, mature and

mellow, and set the tone for the remainder of Clapton’s career. He had

become attracted to minimalism, in search of the simplest way to

convey the greatest amount of emotion. Developments in the 1980s

included work on film soundtracks and a regrettable tilt toward pop

under producer Phil Collins, but the 1990s found him once again

drawn to the blues, while still recording some beautiful compositions

in the soft-rock vein.

The subtleties of the mature Clapton are not as readily appreciat-

ed as the confetti-like maestro guitar work of Cream or Derek and the

Dominos. Once regarded as rock’s most restlessly exploring musi-

cian, too complex to be contained by any one band, by the 1990s

Clapton had become the ‘‘Steady Rollin’ Man,’’ the self-assured

journeyman of soft rock. A younger generation, unaware of his earlier

work, was often puzzled by the awards and adulation heaped upon

this singer of mainstream hits like ‘‘Tulsa Time,’’ but a concert or live

album showed Clapton displaying the legendary flash of old. Except

for a few low points (No Reason to Cry, 1976), and the Phil Collins-

produced albums Behind the Sun (1985) and August (1986), Eric

Clapton aged better than many of his contemporaries, finding a

comfortable niche without pandering to every new trend.

—Douglas Cooke

F

URTHER READING:

DeCurtis, Anthony, ‘‘Eric Clapton: A Life at the Crossroads.’’

Included in the CD boxed set Eric Clapton: Crossroads.

Polydor, 1988.

Headlam, Dave. ‘‘Blues Transformations in the Music of Cream.’’ In

Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis, edited by John

Covach and Graeme M. Boone. New York, Oxford University

Press, 1997.

Roberty, Marc. The Complete Guide to the Music of Eric Clapton.

London, Omnibus, 1995

Schumacher, Michael. Crossroads: the Life and Music of Eric

Clapton. London, Little, Brown and Company, 1995.

Shapiro, Harry. Eric Clapton: Lost in the Blues. New York, Da Capo

Press, 1992.

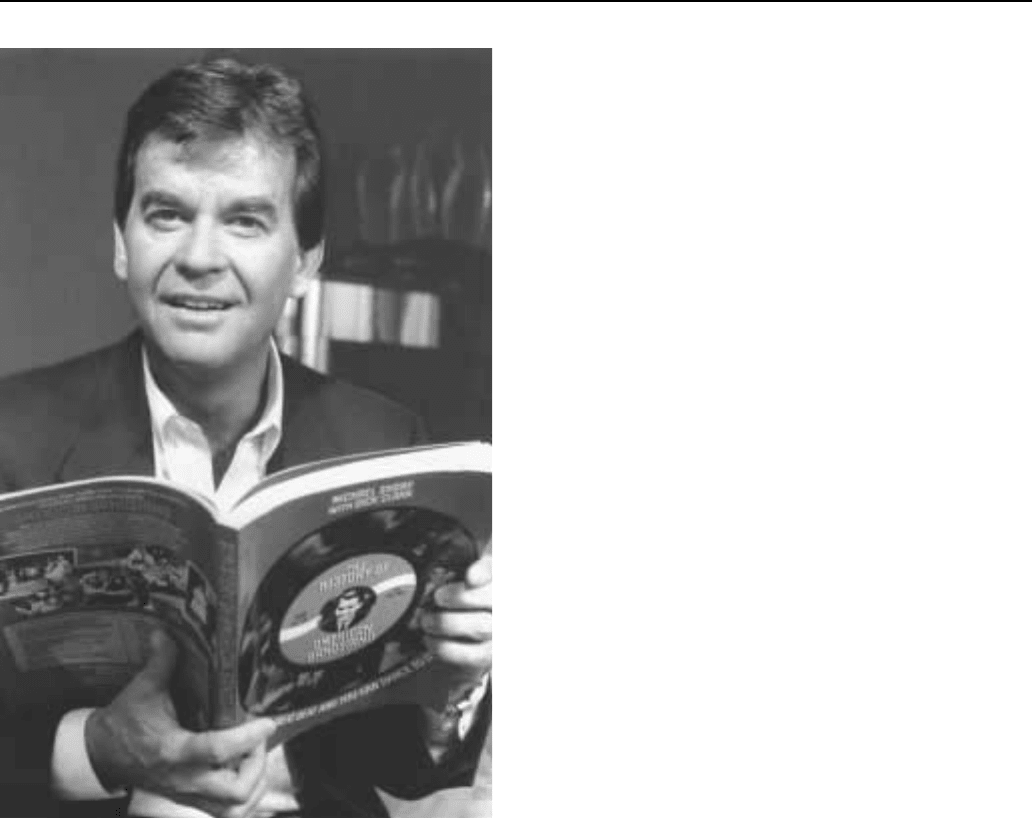

Clark, Dick (1929—)

As host of American Bandstand for more than 30 years, Dick

Clark introduced rock ’n’ roll music via television to a whole

generation of teenaged Americans while reassuring their parents that

the music would not lead their children to perdition. With his eternally

youthful countenance, collegiate boy-next-door personality, and trade-

mark ‘‘salute’’ at the close of each telecast, Clark is one of the few

veterans of the early days of television who remains active after

nearly half a century in broadcasting.

Richard Wagstaff Clark was born in 1929 in Mount Vernon,

New York. His father owned radio stations across upstate New York,

and his only sibling, older brother Bradley, was killed in World War

II. Clark grew up enamored of such radio personalities as Arthur

Godfrey and Garry Moore, and instantly understood the effectiveness

and appeal of their informal on-air approach. Clark studied speech at

CLARK ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

526

Dick Clark

Syracuse University, supplementing his studies with work at campus

radio station WAER. After graduating in 1951, he worked for several

radio and television stations in central New York radio and television,

and even briefly adopted the on-air name ‘‘Dick Clay,’’ to his

later embarrassment.

In 1953 Clark moved to Philadelphia to host an afternoon radio

show, playing popular vocalists for local teenagers. Three years later,

he was chosen as the new host of a local-TV dance show, Bandstand,

which featured the then-new sounds of rock ’n’ roll music. The

show’s previous host, Bob Horn, had been arrested on a morals charge.

Clark was an instant hit with his viewers. By the fall of 1957,

Bandstand was picked up nationally by the ABC network. American

Bandstand quickly became a national phenomenon, the first popular

television series to prominently feature teenagers. Clark demanded

that the teens who appeared on the program observe strict disciplinary

and dress-code regulations. Boys were expected to wear jackets and

ties, and girls, modest skirts and not-too-tight sweaters. Many of the

teens who danced on the show, from Italian-American neighborhoods

in south and west Philadelphia, became national celebrities them-

selves. One of the most popular segments of American Bandstand

was one in which members of the studio audience were asked to rate

new songs, a poll whose results were taken seriously by record

executives. New styles of rock music rose or fell on the whims of the

teenagers, who would explain their decisions by such statements as

‘‘I’d give it an 87. . . it’s got a good beat, and you can dance to it.’’

Interestingly, Clark’s audience panned ‘‘She Loves You,’’ the Beatles’

first hit. The Bandstand audiences introduced a national audience to

such dance moves as the Pony, the Stroll and, most famously, the

Twist, by Philadelphia native Chubby Checker.

As Clark was becoming a millionaire, his career was threatened

by the payola scandals of the 1950s, when it was learned that record

companies illegally paid disc jockeys to play their rock and roll

records. Clark admitted that he partially owned several music pub-

lishers and record labels that provided some of the music on American

Bandstand, and he immediately sold his interests in these companies

as the scandal broke, while insisting, however, that songs from these

companies did not get preferential treatment on his show. Clark made

such a convincing case before a House committee studying payola in

1959 that Representative Owen Harris called him ‘‘a fine young

man’’ and exonerated him. Clark thus provided rock music with a

clean-cut image when it needed it the most.

Clark produced and hosted a series of Bandstand-related concert

acts that toured the United States in the 1950s and 1960s. During their

tours in the South, these were among the first venues where blacks

and whites performed on the same stage. Eventually, even the seating

in these arenas became desegregrated. In 1964, Bandstand moved

from Philadelphia to Los Angeles, coinciding with the popularity of

Southern California ‘‘surf’’ music by The Beach Boys and Jan and

Dean. From that point, the show began relying less on playing records

and more on live performers. Many of the top acts of the rock era

made their national television debut on Bandstand, such as Buddy

Holly and the Crickets, Ike and Tina Turner, Smokey Robinson and

the Miracles, Stevie Wonder and the Talking Heads, and the teenaged

Simon and Garfunkel, known then as Tom and Jerry.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Clark expanded his television

presence beyond Bandstand with Dick Clark Productions, which

generated between 150 and 170 hours of programming annually at its

peak. During these years, Clark hosted the long-running $10,000

Pyramid game show from 1973 through the late 1980s; in subsequent

versions, the word association-based Pyramid expanded with infla-

tion, eventually offering $100,000, and featured numerous celebrity

guests. In 1974 ABC lost the broadcast rights to the Grammy Awards,

and asked Clark to create an alternative music awards show. The

American Music Awards quickly became a significant rival to the

Grammys, popular among artists and audiences alike. In the 1980s,

Clark also produced and hosted a long-running NBC series of highly-

rated ‘‘blooper’’ scenes composed of outtake reels from popular TV

series. His co-host was Ed McMahon of the Tonight Show, who had

been friends with Clark since they were next-door neighbors in

Philadelphia during the 1950s. Clark also replaced Guy Lombardo as

America’s New Year’s Eve host, emceeing the televised descent of

the giant ball in New York’s Times Square on ABC beginning in 1972.

The seemingly ageless Clark, dubbed ‘‘America’s oldest living

teenager’’ by TV Guide, ushered his series with aplomb through the

turbulent 1970s. It was on Bandstand where an audience first body-

spelled ‘‘Y.M.C.A.’’ to The Village People’s number-one hit. With

changes in musical tastes and practices, the popularity of Bandstand

began to wane. What had begun as a local two-and-a-half hour daily

show in the mid-1950s had gradually been whittled down to a weekly,

hour-long show by the 1980s. There were several culprits: competing

network music programs, including The Midnight Special, Solid

CLARKEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

527

Gold, and even Saturday Night Live were competing with Bandstand

to get the hottest acts of the day. The advent of MTV in 1981, with

round-the-clock music videos, further cut into the series’ influence.

As the years passed, new rock groups devoted more time to video

production and promotion, and less to appearing live on shows. Clark

retired from Bandstand in the spring of 1989; with a new host, a

syndicated version of the long-running show called it quits later that

year, only weeks shy of making it into the 1990s.

Ironically enough, however, MTV’s sister station had a hand in

reviving interest in American Bandstand. In 1997, VH-1 ran a weekly

retrospective, hosted by Clark, of highlights from the 1970s and

1980s version of Bandstand. The success of the reruns coincided with

the fortieth anniversary of the show’s national debut, and Clark

returned to Philadelphia to unveil a plaque on the site of the original

American Bandstand television studio. That same year, Clark pub-

lished a comprehensive anniversary volume, and he also announced

the founding of an American Bandstand Diner restaurant chain.

Modeled after the Hard Rock Café and Planet Hollywood chains,

each diner was designed in 1950s style, with photos and music of the

greats Clark helped make famous.

—Andrew Milner

F

URTHER READING:

Clark, Dick and Bronson, Fred. Dick Clark’s American Bandstand.

New York, Harper Collins, 1997.

Jackson, John A. American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of

a Rock and Roll Empire. New York, Oxford University, 1997.

The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll. New York,

Random House, 1992.

Clarke, Arthur C. (1917—)

British writer Arthur Charles Clarke’s long and successful career

has made him perhaps the best-known science fiction writer in the

world and arguably the most popular foreign-born science fiction

writer in the United States. Clarke is best known for 2001: A Space

Odyssey (1968), the film script he wrote with noted director

Stanley Kubrick.

Clarke’s writings are in genre of ‘‘hard’’ science fiction—stories

in which science is the backbone and where technical and scientific

discovery are emphasized. He is considered one of the main forces for

placing ‘‘real’’ science in science fiction; science fiction scholar Eric

Rabkin has described Clarke as perhaps the most important science-

oriented science fiction writer since H. G. Wells. His love and

understanding of science coupled with his popularity made him a

central figure in the development of post-World War II science

fiction. Clarke’s success did much to increase the popularity of

science and create support for NASA and the U.S. space program.

For Clarke, technological advancement and scientific discovery

have been generally positive developments. While he was cognizant

of the dangers that technology can bring, his liberal and optimistic

view of the possible benefits of technology made him one of the small

number of voices introducing mass culture to the possibilities of the

future. His notoriety was further enhanced domestically and globally

when he served as commentator for CBS television during the Apollo

11, 12, and 15 Moon missions.

A second theme found in Clarke’s work which resonates in

popular culture suggests that no matter how technologically advanced

humans become, they will always be infants in comparison to the

ancient, mysterious wisdom of alien races. Humanity is depicted as

the ever-curious child reaching out into the universe trying to learn

and grow, only to discover that the universe may not even be

concerned with our existence. Such a theme is evident in the short

story ‘‘The Sentinel’’ (1951), which describes the discovery of an

alien artifact created by an advanced race, millions of years earlier,

sitting atop a mountain on the moon. This short story provided the

foundation for 2001 (1968). One of Clarke’s most famous books,

Childhood’s End (1950), envisions a world where a portion of earth’s

children are reaching transcendence under the watchful eyes of alien

tutors who resemble satanic creatures. The satanic looking aliens

have come to earth to assist in a process where select children change

into a new species and leave earth to fuse with a cosmic overmind—a

transformation not possible for those humans left behind or for their

satanistic alien tutors.

Clarke’s achieved his greatest influence with 2001, which was

nominated for four Academy Awards, including best picture, and

ranked by the American Film Institute as the 22nd most influential

American movie in the last 100 years. Clarke’s novelization of the

movie script, published under the same title in 1968, had sold more

that 3 million copies by 1998 and was followed by 2010: Odyssey

Two (1982). The sequel was made into a film directed by Peter

Hyams, 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984, starring Roy

Scheider). Clarke has followed up the first two books in the Odyssey

series with 2061: Odyssey Three (1988) and 3001: The Final

Odyssey (1997).

The impact of 2001 is seen throughout American popular

culture. The movie itself took audiences on a cinematic and cerebral

voyage like never before. As Clarke said early in 1965, ‘‘MGM

doesn’t know it yet, but they’ve footed the bill for the first six-million-

dollar religious film.’’ The film gave the public an idea of the wonder,

beauty, and promise open to humanity at the dawn of the new age of

space exploration, while simultaneously showing the darker side of

man’s evolution: tools for progress are also tools for killing. Nowhere

is this more apparent than in HAL, the ship’s onboard computer.

Although Clarke possesses a liberal optimism for the possibilities

found in the future, HAL poignantly demonstrates the potential

dangers of advanced technology. The name HAL, the computer’s

voice, and the vision of HAL’s eye-like optical sensors have since

become synonymous with the danger of over reliance on computers.

This is a theme seen in other films ranging from Wargames (1983) to

the Terminator (1984, 1991) series. The killings initiated by HAL and

HAL’s subsequent death allow the surviving astronaut to pilot the

ship to the end of its voyage. Here the next step of man takes place as

the sole survivor of this odyssey devolves into an infant. The Star

Child is born; Man evolves into an entity of pure thought. The

evolution/devolution of the astronaut completes the metaphor that

humanity does not need tools to achieve its journey’s end, our final

fulfillment, but only ourselves.

The message of 2001 is powerfully reinforced by the music of

Richard Strauss. Strauss’ dramatic ‘‘Also Sprach Zarathustra,’’ com-

posed in 1896, was used several times during the movie but never

with more impact than in the ‘‘Dawn of Man’’ segment. As the movie

progressed, this music (as well as music composed by Johan Strauss)

came to carry the narrative nearly as effectively as the dialogue.

CLEMENTE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

528

Some have even suggested that the film influenced the language

of the astronauts aboard the Apollo 13 mission. When HAL reports

the ‘‘failure’’ of the AE 35 Unit, he says ‘‘Sorry to interrupt the

festivities, but we have a problem.’’ On the Apollo 13 command

module, named Odyssey, the crew had just concluded a TV broadcast

which utilized the famous ‘‘Zarathustra’’ theme when an oxygen tank

exploded. The first words sent to Earth were ‘‘Houston, we’ve had

a problem.’’

—Craig T. Cobane

F

URTHER READING:

Boyd, David. ‘‘Mode and Meaning in 2001.’’ Journal of Popular

Film. Vol. VI, No. 3, 1978, 202-15.

Clarke, Arthur C. Astounding Days: A Science Fictional Autobiogra-

phy. New York, Bantam Books, 1989.

McAleer, Neil. Odyssey: The Authorised Biography of Arthur C.

Clarke. London, Victor Gollancz, 1992.

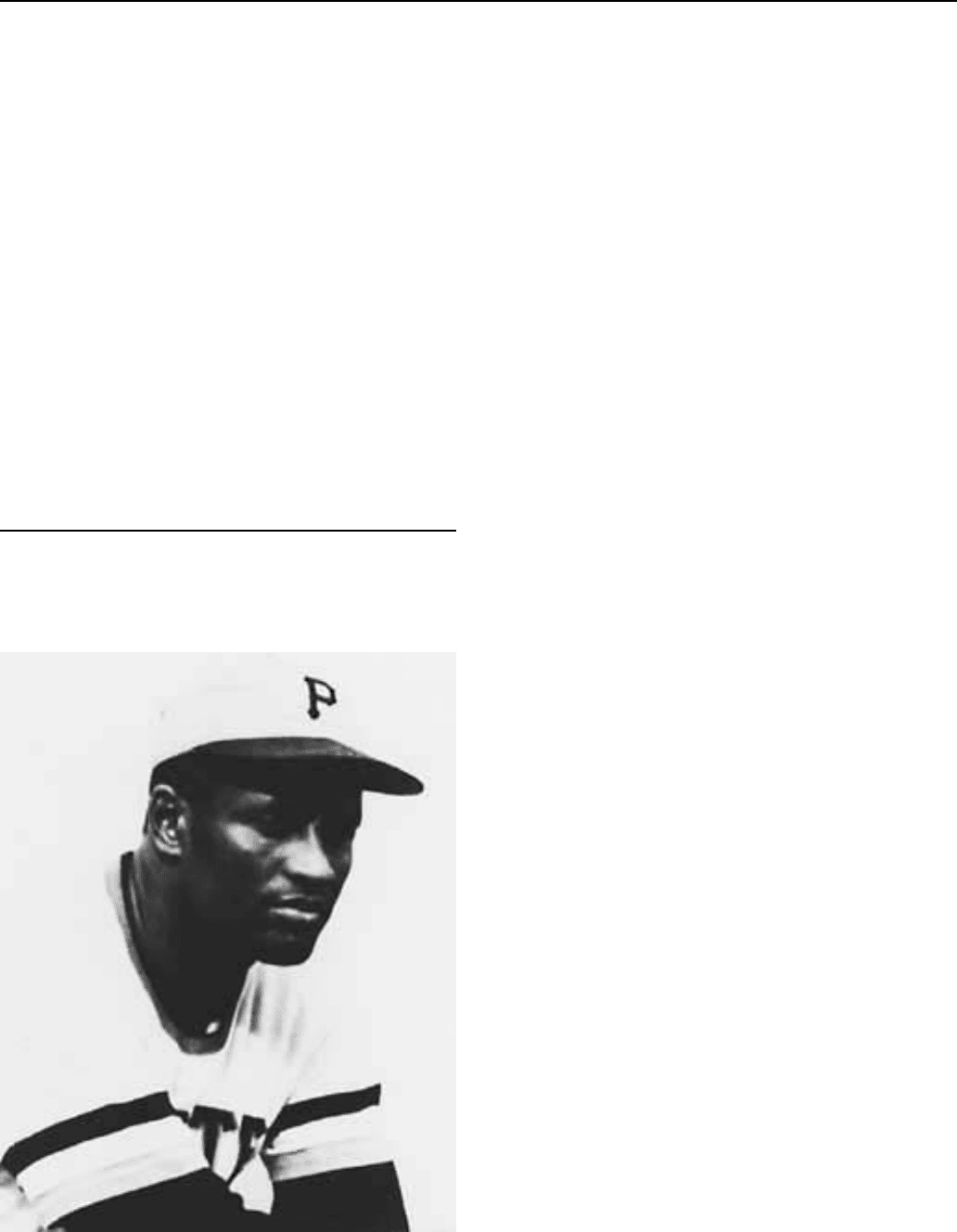

Clemente, Roberto (1934-1972)

Longtime Pittsburgh Pirates rightfielder Roberto Clemente is

much more than one of the premier major leaguers of his generation.

While his statistics and on-field accomplishments earned him election

Roberto Clemente

to the Baseball Hall of Fame, equally awe-inspiring are his sense of

professionalism and pride in his athleticism, his self-respecting view

of his ethnicity, and his humanism. Clemente, who first came to the

Pirates in 1955, died at age 38, on New Year’s Eve 1972, while

attempting to airlift relief supplies from his native Puerto Rico to

Nicaraguan earthquake victims. He insisted on making the effort

despite bad weather and admonitions that the ancient DC-7 in which

he was flying was perilously overloaded. This act of self-sacrifice,

which came scant months after Clemente smacked major-league hit

number 3,000, attests to his caliber as a human being and transformed

him into an instant legend.

Roberto Walker Clemente was born in Barrio San Anton in

Carolina, Puerto Rico. While excelling in track and field as a

youngster, his real passion was baseball—and he was just 20 years old

when he came to the major leagues to stay. On the ballfield, the

muscular yet sleek and compact Clemente dazzled as he bashed extra-

base hits, made nifty running catches, and fired perfect strikes from

deep in the outfield to throw out runners. He was particularly noted

for his rifle arm. As Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers announcer Vin

Scully once observed, ‘‘Clemente could field a ball in New York and

throw out a guy in Pennsylvania.’’

Clemente’s on-field record is exemplary. In his 18 seasons with

the Pirates, he posted a .317 batting average. He won four National

League batting crowns, and earned 12 consecutive Gold Gloves for

his fielding. On five occasions, he led National League outfielders in

assists. He played in 12 all-star games. He was his league’s Most

Valuable Player (MVP) in 1966, and was the World Series MVP in

1971. When he doubled against Jon Matlack of the New York Mets on

September 30, 1972, in what was to be his final major league game, he

became just the eleventh ballplayer to belt 3,000 hits.

Yet despite these statistics and the consistency he exhibited

throughout his career, true fame came to Clemente late in life. In the

1960 World Series, the first of two fall classics in which he appeared,

he hit safely in all seven games. He was overshadowed, however, by

his imposing opponents, the Mickey Mantle-led New York Yankees,

and by teammate Bill Mazeroski’s dramatic series-winning home run

in game 7. Clemente really did not earn national acclaim until 1971,

when he awed the baseball world while starring in the World Series,

hitting .414, and leading his team to a come-from-behind champion-

ship over the favored Baltimore Orioles. According to sportswriter

Roger Angell, it was in this series that Clemente’s play was ‘‘some-

thing close to the level of absolute perfection.’’

Clemente was fiercely proud of his physical skills. Upon com-

pleting his first season with the Pirates, his athletic ability was likened

to that of Willie Mays, one of his star contemporaries. The ballplay-

er’s response: ‘‘Nonetheless, I play like Roberto Clemente.’’ During

the filming of the 1968 Neil Simon comedy The Odd Couple, a

sequence, shot on location at Shea Stadium, called for a Pittsburgh

Pirate to hit into a triple play. In the film, Bill Mazeroski is the hitter.

Supposedly, Clemente was set to be at bat during the gag, but pulled

out because of the indignity.

In the decade-and-a-half before his 1971 World Series heroics,

Clemente yearned for the kind of acknowledgment won by a Mays or

a Mantle. Certainly, he was deserving of such acclaim. Had he been

playing in New York, Los Angeles, or Chicago, rather than in a city

far removed from the national spotlight, he might have been a high

profile player earlier in his career. Compounding the problem was

Clemente’s ethnic background. Furthermore, Clemente was keenly

aware of his roots, and his ethnicity; he even insisted that his three