Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHILD STARSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

499

film, television, and music. Popular culture will ever worship at the

Fountain of Youth.

From the early days of vaudeville in the nineteenth century, child

actors have held their own against adult stars. Adored by fans, many

became household names across America. In the first decade of the

twentieth century, during the infancy of motion pictures, film direc-

tors hoped to lure the top tykes from the stage onto the screen, but

most stage parents refused, feeling that movies were beneath them

and their talented children. Everything changed when a curly haired,

sweet-faced sixteen-year-old, who had been a big Broadway star as

Baby Gladys, fell on hard times and reluctantly auditioned for movie

director D. W. Griffith. Griffith hired the former Baby Gladys on the

spot, renamed her Mary Pickford, and made her into ‘‘America’s

Sweetheart.’’ She became America’s first movie star. As noted in

Baseline’s Encyclopedia of Film, Mary Pickford was, ‘‘if popularity

were all, the greatest star there has ever been.... Little Mary became

the industry’s chief focus and biggest asset, as well as the draw of

draws—bigger, even, than Chaplin.’’

The success of Mary Pickford in many ways paralleled the

ascendancy of movies themselves. As audiences embraced the young

star, they embraced the medium, and movies grew into a national

obsession. Along with Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, himself a former

child star in British vaudeville, became one of the motion picture

industry’s success stories. A huge star by the late teens, Chaplin made

the films that America wanted to see. When he discovered a young

boy performing in vaudeville who reminded him of himself as a child,

Chaplin created a film for them both to star in. Little Jackie Coogan’s

endearing performance in The Kid made the six-year-old a household

name and launched Hollywood’s Child Star Era.

During the 1920s, studios churned out silent films at an amazing

rate. Westerns, action pictures, murder mysteries, and romances all

drew audiences to the theatres. After The Kid, so did movies starring

children, including the immensely popular Our Gang series. Movie

studios sent out continual casting calls in search of clever and cute

kids, and parents from all over America began to flock to Hollywood

in search of fame and fortune for their offspring. When Jackie Coogan

was awarded a million-dollar movie contract in 1923, the race to find

the next child star was on. As Diana Serra Carey, a former child star

who became very famous during the 1920s and 1930s as Baby Peggy,

has written: ‘‘Although the child star business was a very new line to

be in, it opened up a wide choice of jobs for many otherwise unskilled

workers, and it grew with remarkable speed. Speed was, in fact, the

name of the game. Parents, agents, producers, business managers, and

a host of lesser hangers-on were all engaged in a desperate race to

keep ahead of their meal ticket’s inexorable march from cuddly infant

to graceless adolescent.’’ Soon Hollywood was filled with a plethora

of people pushing their youthful products.

In 1929, when the stock market crashed and America fell into the

Great Depression, the movie industry faced a crisis: in a time of

severe economic hardship, would Americans part with their hard-

earned money to go to the movies? But sound had just come in, and

America was hooked. For a nickel, audiences could escape the harsh

reality of their daily lives and enter a Hollywood fantasy. Movies

boomed during the Depression, and child stars were a big part of

that boom.

By the early 1930s, children had come to mean big business for

Hollywood. The precocious and versatile Mickey Rooney had been a

consistent money earner since the mid-1920s, as were new stars such

as The Champ’s Jackie Cooper. But nothing would prepare Holly-

wood, or the world, for the success of a curly haired six-year-old

sensation named Shirley Temple.

The daughter of a Santa Monica banker and his star-struck wife,

Shirley Temple was a born performer. At three, the blond-haired,

dimpled cherub was dancing and singing in two-reelers. By six, when

she starred in Stand Up and Cheer, she had become a bona fide movie

star. Baseline’s Encyclopedia of Film notes: ‘‘Her bouncing blond

curls, effervescence and impeccable charm were the basis for a

Depression-era phenomenon. Portraying a doll-like model daughter,

she helped ease the pain of audiences the world over.’’ In 1934, she

received a special Academy Award. A year later, she was earning one

hundred thousand dollars a year. For most of the 1930s, Shirley

Temple was the number one box office star. Twentieth-Century Fox

earned six million dollars a year on her pictures alone.

During the height of the Child Star Era, the major studios all

boasted stables of child actors and schoolrooms in which to teach

them. Among the top stars of the decade were the British Freddie

Bartholomew, number two to Shirley Temple for many years; Deanna

Durbin, the singing star who single-handedly kept Universal Studios

afloat; and the incredibly gifted Judy Garland. But for every juvenile

star, there were hundreds of children playing supporting and extra

roles, hoping to become the next Shirley Temple.

As America emerged from the Depression and faced another

World War, the child stars of the 1930s faced adolescence. Shirley

Temple, Freddie Bartholomew, and Jackie Cooper had become

teenagers, and Hollywood didn’t seem to know what to do with them.

Audiences were not interested in watching their idols grow up on

screen, and most child stars were not re-signed by their studios.

Shirley Temple was literally thrown off the lot that she had grown up

on. But there were always new kids to take the place of the old, and in

the 1940s, Hollywood’s top stars included Roddy McDowall, Marga-

ret O’Brien, Natalie Wood, and Elizabeth Taylor. As their predeces-

sors had done, these child stars buoyed American audiences through

difficult times. And again, when their own difficult times came with

adolescence, American audiences abandoned them. Fortunately, for

many of the child stars of the 1940s, times were changing, and so was

Hollywood. As the studio system and Child Star Era began to crumble

in the late 1940s, these youthful actors and actresses found work in

independent films and in television.

By the early 1950s, audiences were calling for a different kind of

film, and Hollywood was complying. Television became the new

breeding ground for child stars, as youthful actors were called upon to

appear in such popular sitcoms as Leave It to Beaver in the 1950s, My

Three Sons in the 1960s, The Brady Bunch in the 1970s, Diff’rent

Strokes in the 1980s, and Home Improvement in the 1990s. Although

TV audiences were interested in watching the children on their

favorite shows grow up on the air, making the transition from child to

teenager more easily accomplished, because the life of a series was

generally short, youthful TV stars faced the same trouble as their child

movie star predecessors once the show went off the air. They found it

difficult to be taken seriously as adult actors. They also found it

difficult to adjust to a life out of the limelight. As Jackie Cooper once

said: ‘‘One thing I was never prepared for was to be lonely and

frightened in my twenties.’’

The music industry, too, has always had its fair share of child

prodigies. From Mozart to Michael Jackson, audiences have always

CHINA SYNDROME ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

500

been drawn to youthful genius. But while some young stars such as

Little Stevie Wonder managed to make the transition to adult star-

dom, there are equally as many children who have not made it. And

when the music industry began creating child acts to promote, it soon

found itself facing the same problems as had movies and television.

Would audiences who found child singers cute still buy their records

when they were less-than-talented adults? In too many cases, the

answer was no.

When little Ronnie Howard of The Andy Griffith Show was cast

as a teenager on Happy Days, it was a big step for a child star. When

he became a successful movie director, he was lauded as having

dodged the stigma of child stardom. Others have followed in his

footsteps, most notably Jodie Foster, a two-time Academy Award

winner who is one of Hollywood’s most respected actresses and

directors. And, of course, Shirley Temple went on to have a distin-

guished political career, serving as a United States ambassador. But

for every Ron Howard, Jodie Foster, Roddy McDowall, or Shirley

Temple, there are hundreds of former child stars who have had to face

falling out of the spotlight. For all the former child stars who have

managed to create for themselves a normal adult life, there are far too

many who have fallen into a life of dysfunction or drug use. For

others, such as Rusty Hamer, a child star for nine years on Make Room

for Daddy, or Trent Lehman, who played Butch on Nanny and the

Professor, the transition from child star to adulthood ended in suicide.

In 1938, twenty-four-year-old Jackie Coogan went to court to

sue his mother for his childhood earnings, which were between two

and four million dollars. Married to a rising young starlet named Betty

Grable, Coogan was broke and sought to get what was legally his. By

the end of the trial, his millions were found to be almost all gone, and

the strain of the trial destroyed his marriage. But out of Coogan’s

tragedy came the Coogan Act, a bill which forced the parents of child

actors to put aside at least half of their earnings. That still hasn’t

prevented child stars such as Gary Coleman from having to go to court

to fight for their hard-earned millions, however.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the motion picture industry has

witnessed a resurgence of interest in child stars. River Phoenix and

Ethan Hawke, both teenage actors, managed to make the difficult

transition to adult roles. But Phoenix, although a seemingly mature

young man praised for his formidable talents, found the pressures of a

Hollywood lifestyle too much and died of an accidental drug overdose

in 1993. In the early 1990s, Macaulay Culkin was perhaps the biggest

child star since Shirley Temple. But when audiences lost interest in

the teenager, he stopped working altogether. Soon his parents were

engaged in a battle over custody and money, while the tabloids ran

articles about Culkin’s troubled life.

Despite the object lessons drawn from the lives of so many child

stars, audiences will continue to pay to see juvenile performers even

as the television, movie, and music industries will continue to

promote them. Child stars represent the duel-edged sword that is

American popular culture. Epitomizing the youthful glamour by

which Americans are taught to be seduced, children have entranced

audiences throughout the twentieth century. But on the other side of

glamour and fame are the bitter emptiness of rejection and the harsh

reality of life out of the spotlight. Perhaps former child star Paul

Petersen said it best: ‘‘Fame is a dangerous drug and should be kept

out of the reach of children—and their parents as well.’’

—Victoria Price

F

URTHER READING:

Cary, Diana Serra. Hollywood’s Children: An Inside Account of the

Child Star Era. Dallas, Southern Methodist University, 1997.

Monaco, James, and the editors of Baseline. The Encyclopedia of

Film. New York, Perigee, 1991.

Moore, Dick. Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star: And Don’t Have Sex or

Take the Car. New York, Harper and Row, 1984.

Zierold, Norman J. The Child Stars. New York, Coward-McCann, 1965.

The China Syndrome

Possibly more than any other film, The China Syndrome’s

popularity benefited from a chance occurrence. The China Syndrome

showed many Americans their worst vision of technology gone

wrong, but it proved entirely too close to reality when its release

coincided with a near meltdown at Three Mile Island, Pennsylvania.

In the film, Jane Fonda and Michael Douglas play the television news

team who, while researching the newly perfected nuclear technology,

capture on film an accident resulting in a near meltdown of the power

plant. Fonda and Douglas’s characters find themselves trapped be-

tween the public’s right to know and the industry’s desire to bury the

incident. The nuclear accident depicted by the film became the

platform for ‘‘NIMBY’’ culture, in which expectations of comfort

and a high standard of safety compelled middle-class Americans to

proclaim ‘‘Not in my backyard!’’ Together, these incidents—one

fictional and another all too real—aroused enough concern among

Americans to prohibit nuclear energy from ever becoming a consider-

able source of power for the nation.

—Brian Black

Chinatown

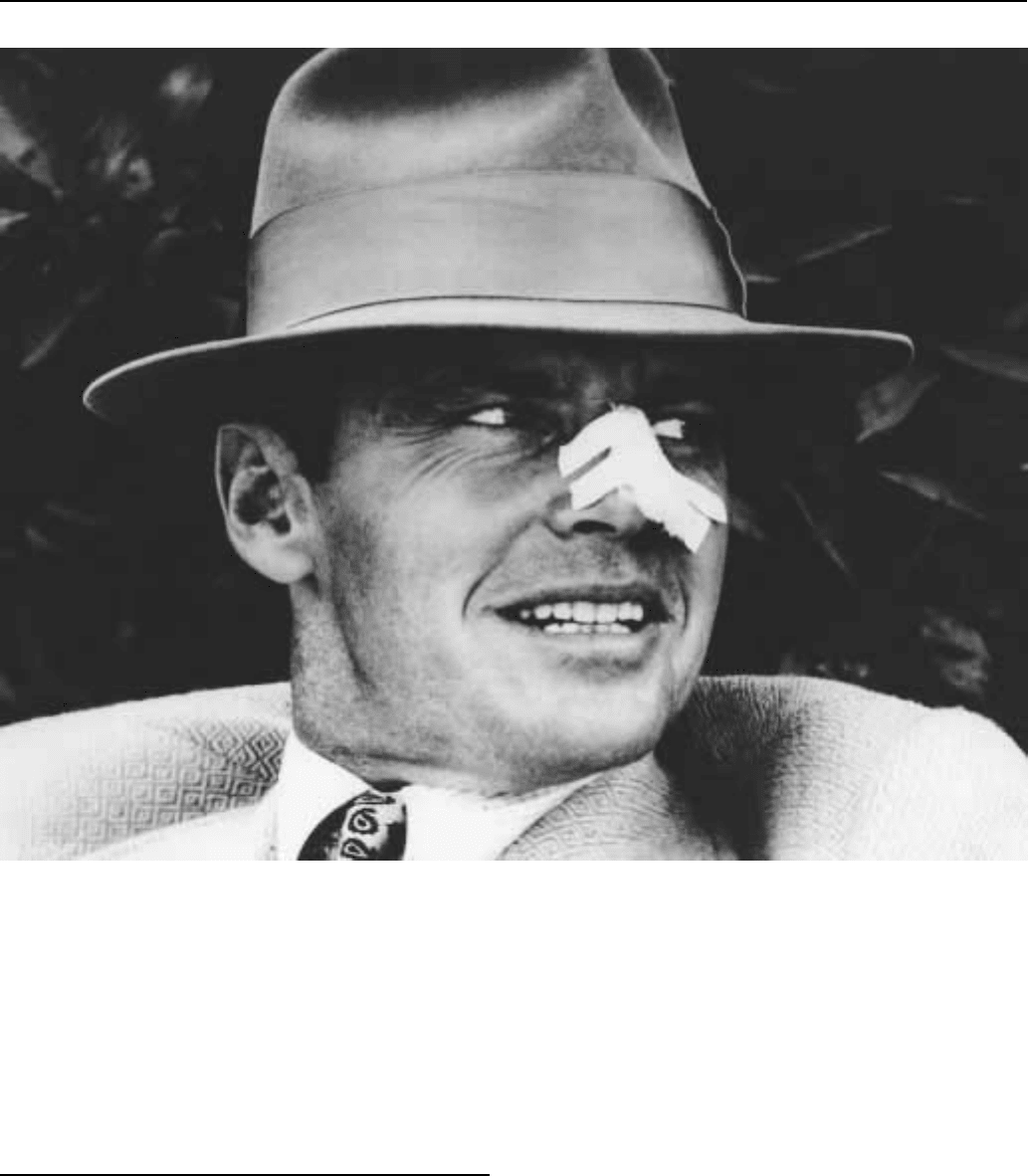

Roman Polanski directed this 1974 classic film portraying the

mystery and intrigue of Raymond Chandler’s fascinating novel. Jack

Nicholson played Jake Gittes, a private detective trapped in the odd

Asian-immigrant culture of the desert West. Hired to investigate the

murder of the chief engineer for the Los Angeles Power and Water

Authority in 1930s California, Gittes finds himself pulled into the

unique political and economic power structure of the arid region:

water politics with all its deceits and double dealings dominates

planning and development.

The film acquired a cult following because of its dark, intriguing

story—seemingly based in another world and era—and the enduring

popularity of Jack Nicholson. Chinatown’s film noir setting places it

in a long line of fine films deriving from the 1940s mysteries of Alfred

Hitchcock. The defining characteristic of such films is uncertainty—

of character and plot. Gittes repeatedly appears as the trapped

character searching in vain for truth; indeed, the viewer searches with

him. In the end, the evil is nearly always exposed. However, typical to

film noir, Chinatown’s conclusion leaves the viewer strangely unsure

if truth actually has emerged victorious.

CHIPMUNKSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

501

Jack Nicholson in a scene from the film Chinatown.

In 1990, Nicholson starred in and directed Chinatown’s sequel,

The Two Jakes, set in 1948 California. Oil has replaced water as the

power source for regional wealth, creating a fine backdrop for another

dark mystery based on adultery and intrigue.

—Brian Black

The Chipmunks

The Chipmunks—Alvin, Simon, and Theodore—were the only

cartoon rodents to sell millions of records and star in their own

television series. The voices of all three chipmunks, as well as the part

of David Seville, were performed by actor/musician Ross Bagdasarian

(1919-1972). As Seville, Bagdasarian had enjoyed a #1 hit with

‘‘Witch Doctor’’ in early 1958; later that year he released ‘‘The

Chipmunk Song’’ (‘‘Christmas Don’t Be Late’’) in time for the

Christmas season, and sold over four million singles in two months.

The Chipmunks, with their high warbling harmonies, churned out a

half dozen records in the late 1950s and early 1960s. All of

Bagdasarian’s records were on the Liberty label, and the chipmunks

were named for three of Liberty’s production executives.

The Chipmunks’ popularity led to a primetime cartoon series

(The Alvin Show) on CBS television during the 1961-62 season. In

1983, Ross Bagdasarian, Jr., revived the act with a second successful

cartoon series, Alvin and the Chipmunks, which aired on NBC from

1983 to 1990, and a new album, Chipmunk Punk.

—David Lonergan

F

URTHER READING:

Brooks, Tim, and Earle Marsh. The Complete Directory to Prime

Time Network TV Shows. 5th edition. New York, Ballantine

Books, 1992.

‘‘Cartoon-O-Rama Presents: The Alvin Show.’’ http://

members.aol.com/PaulEC1/alvin.html. February 1999.

CHOOSE-YOUR-OWN-ENDING BOOKS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

502

Whitburn, Joel. The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. 6th edition. New

York, Billboard Books, 1996.

Chong, Tommy

See Cheech and Chong

Choose-Your-Own-Ending Books

Thanks to the interactive capabilities of the computer, traditional

styles of linear narrative in storytelling can be altered by means of

hypertext links that allow readers the ability to alter the direction of a

story by making certain decisions at various points, in effect choosing

their own endings. This interactive style was presaged in the 1970s

when several children’s publishers began offering books that invited

readers to custom-design the flow of a story by offering a choice of

different pages to which they could turn. Strictly speaking, ‘‘Choose-

Your-Own-Ending Books’’ refer to several series of children’s books

published by Bantam Books since 1979. Originated by author Edward

Packard, Bantam’s ‘‘Choose-Your-Own-Adventure’’ series num-

bered about 200 titles in the first 20 years of publication, with spinoffs

such as ‘‘Choose Your Own Star Wars Adventure’’ and ‘‘Choose

Your Own Nightmare.’’

The ‘‘Choose Your Own Adventure’’ series has proven to be

immensely popular among its young readers, who unwittingly gave

their blessing to the concept of interactive fiction even before it

became commonplace on computer terminals or CD-ROMs. A 1997

profile of Packard in Contemporary Authors quoted an article he

wrote for School Library Journal in which he stated that ‘‘multiple

plots afford the author the opportunity to depict alternative conse-

quences and realities. Complexity may inhere in breadth rather than in

length.’’ The technique appealed to young readers for whom active

participation in the direction of a narrative was a sign of maturity and

ownership of the text.

The first book Packard wrote in this style, Sugarcane Island, a

story about a trip to the Galapagos Islands, did not excite interest

among publishers so he put it aside for five years. It finally found a

home with Vermont Crossroads Press, an innovative children’s book

publisher, which brought out the book in 1976. The fledgling series

gained national attention when the New York Times Book Review

(April 30, 1978) devoted half a page to a Pocket Books/Archway

edition of Sugarcane Island and to a Lippincott edition of Packard’s

Deadwood City. Reviewer Rex Benedict wrote: ‘‘Dead or alive, you

keep turning pages. You become addicted.’’

Other reviewers, especially in the school library press, felt that

the books were gimmicky and that they prevented children from

developing an appreciation for plot and character development.

An article in the journal Voice for Youth Advocates endorsed the

books for their participatory format, however, noting that ‘‘readers’

choices and the resulting consequences are fertile ground for develop-

ing students’ ability to predict outcomes or for group work on

values clarification.’’

Writers who have contributed to the series and its various

spinoffs have included Richard Brightfield, Christopher Golden,

Laban Carrick Hill, Robert Hirschfeld, Janet Hubbard-Brown, Vince

Lahey, Jay Leibold, Anson Montgomery, R. A. Montgomery, and

Andrea Packard.

—Edward Moran

F

URTHER READING:

Contemporary Authors, New Revision Series, vol. 59. Detroit, Gale

Research, 1998.

Packard, Edward. Cyberspace Warrior. New York, Bantam, 1994.

———. Deadwood City. Philadelphia and New York, J. B. Lippin-

cott, 1978.

———. Fire on Ice. New York, Bantam, 1998.

———. Sugarcane Island. Vermont Crossroads Press, 1976.

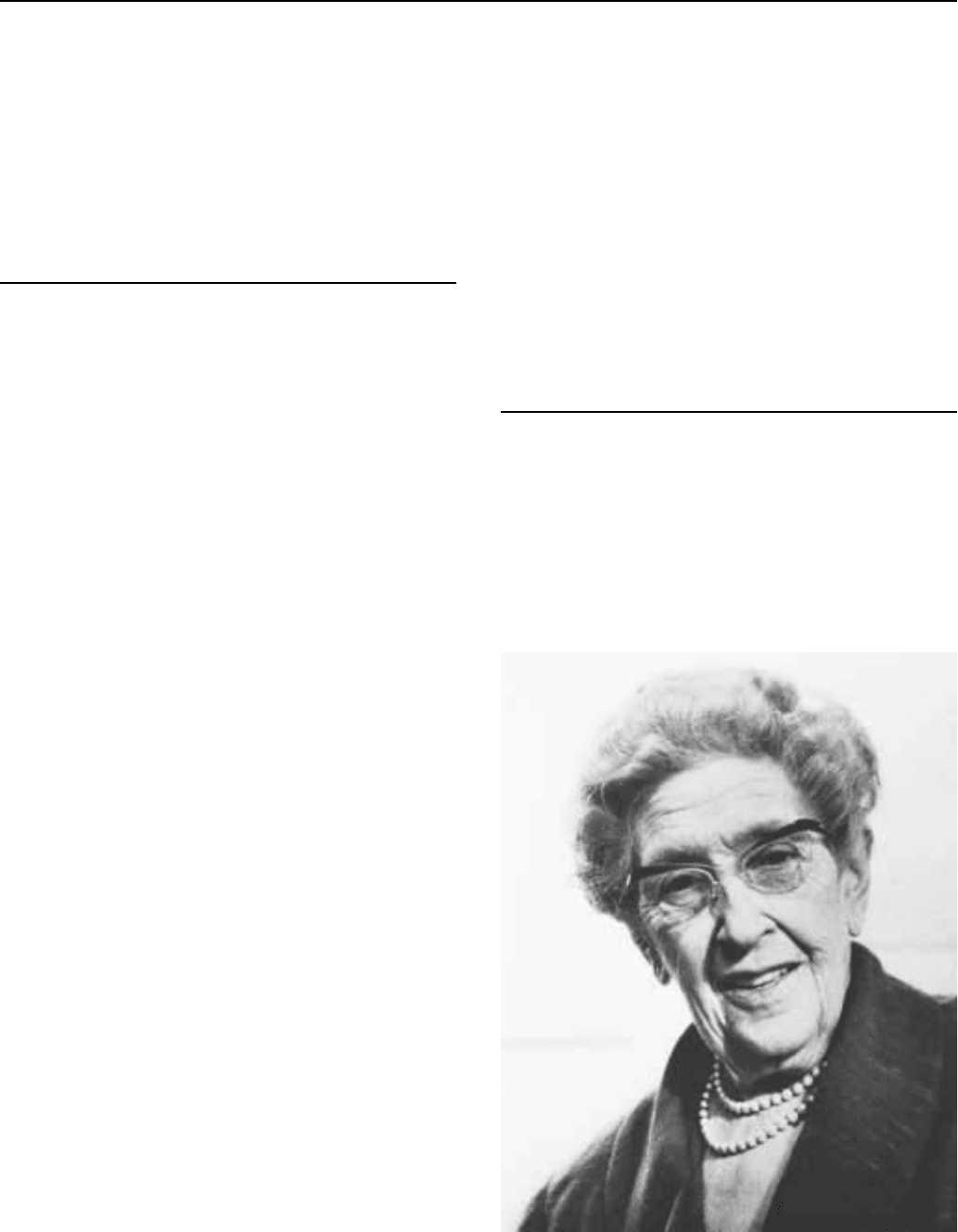

Christie, Agatha (1890-1979)

Deemed the creator of the modern detective fiction novel and

nicknamed the Duchess of Death, Agatha Christie continues to be one

of the most popularly read authors since the publication of her first

book, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, in 1920. Since then, more than

100 million copies of her books and stories have been sold.

Born Agatha Miller on September 15, 1890, in Torquay, located

in Devonshire, England, Christie enjoyed a Victorian childhood

where her parents’ dinner parties introduced her to Henry James and

Rudyard Kipling. Formally educated in France and debuting in Cairo,

Agatha Christie

CHRISTMASENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

503

Agatha began writing seriously after she married Archibald Christie

in 1914. She wrote her first novel in 1916 in just two weeks. Several

publishers rejected the manuscript. Almost two years later, John Lane

accepted the book and offered her a contract for five more.

While her creative interests increased, Christie’s relationship

with her husband steadily declined until he left her in 1926 for his

mistress, Nancy Neele. On December 6 of the same year, Christie

disappeared for eleven days. Her car was found abandoned at Newlands

Corner in Yorkshire. Later, employees at the Hydro Hotel in Harrogate

recognized Christie as a guest at the spa resort, where Christie had

identified herself to hotel employees and guests as Teresa Neele from

South Africa. Christie later claimed to have been suffering from

selective amnesia; she never wrote about her disappearance.

Divorcing her first husband in 1928, Christie married Max

Mallowan in 1930 after meeting him during an excursion to Baghdad

in 1929. Accompanying him on archeological excavations, Christie

traveled extensively in the Middle East and also to the United States in

1966 for his lecture series at the Smithsonian Institute. While stateside,

Christie began to write a three-part script based on Dickens’s Bleak

House. She only completed two parts of the project before withdraw-

ing herself from the script. While she enjoyed novel and short story

writing, Christie cared little for scriptwriting and even less for the film

adaptations made from her novels, even though critics praised Charles

Laughton’s and Marlene Dietrich’s performances in Witness for the

Prosecution (1955).

Several national honors arose in accordance with Christie’s

popular fame as a novelist. In 1956, she was named Dame Command-

er of the Order of the British Empire, and in 1971, Christie was

appointed Dame of the British Empire. Despite these accolades,

Christie continued to lead a quiet private life, writing steadily until her

death in 1979.

Though mystery novels as a genre became fashionable in the

nineteenth century, Christie popularized the format so successfully

that mystery writers continue to follow her example. Christie built on

an early modern theme of comedies: a misunderstanding, crime, or

murder occurs in the first act, an investigation follows with an

interpolation of clue detection and character analysis, and the story

concludes with a revelation, usually of mistaken identities, leading to

the capture of the murderer.

During her life, Christie wrote sixty-six novels, more than one

hundred short stories, twenty plays, an autobiography, and other

various books of poetry and nonfiction. Though her play The Mouse-

trap (1952) is the longest running play in London’s West End,

Christie’s most enduring work incorporates the two now-famous

fictional detectives Hercule Poirot and Jane Marple.

A Belgian immigrant living in London, Hercule Poirot embodies

the ideal elements of a modern detective, though Christie clearly

fashioned him after Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. Like

Holmes, Poirot studies not only the clues of the crime but also the

characters of the suspects. What distinguishes him from Holmes is

Poirot’s attention to personal appearance. Even while traveling by

train in Murder on the Orient Express, Poirot finds time to set and

style his moustache. Because of his attention to detail, Poirot, in a

time before fingerprint matches and DNA testing, solves mysteries by

using what he terms ‘‘the little gray cells.’’

Miss Marple, an elderly spinster, acts as Poirot’s antithesis

except for her ability to solve mysteries. Marple is a successful

detective because of her unobtrusive and innocuous presence. Few

suspects assume an older woman with a knitting bag can deduce a

motive behind murder. Marple, like Poirot, however, does embody a

particularly memorable trait: she doesn’t trust anyone. In Christie’s

autobiography, the author describes Miss Marple: ‘‘Though a cheer-

ful person she always expected the worst of everyone and everything

and was, with almost frightening accuracy, usually proved right.’’

Both detectives have been made famous in the United States by

the critically acclaimed television series Poirot and Agatha Christie’s

Miss Marple, produced by and aired on the Arts and Entertainment

network, and beginning in 1989, and on the PBS weekly program

Mystery! Although more than sixty-five film and made-for-television

adaptations have been produced from Christie’s novels, none claims

the following these series command. Immortalizing the roles of

Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, David Suchet and Joan Hickson

have indelibly imprinted images of the detectives in the minds of fans.

Though Agatha Christie died long before the creation of the series,

her legacy of detective fiction will be remembered in the United

States not only in print but on the small screen as well.

—Bethany Blankenship

F

URTHER READING:

Bargainnier, Earl F. The Gentle Art of Murder: The Detective Fiction

of Agatha Christie. Bowling Green, Ohio, Bowling Green Univer-

sity Popular Press, 1980.

Christie, Agatha. An Autobiography. London, William Collins Sons

& Co, 1977.

Gerald, Michael C. The Poisonous Pen of Agatha Christie. Austin,

University of Texas Press, 1993.

Keating, H. R. F. Agatha Christie: First Lady of Crime. London,

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977.

Osborne, Charles. The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie. London,

Michael O’Mara Books Limited, 1982.

Wagoner, Mary S. Agatha Christie. Boston, Twayne Publishers, 1986.

Christmas

For Americans, the celebration of Christmas is often considered

one of the most important holidays of the year. Because of the diverse

heritages and customs, in addition to Kwanzaa, a tradition begun in

the later part of the twentieth century, the American Christmas

consists of traditions from not only the German, but English, Dutch,

and other Eastern European countries as well. Having religious

significance, Christmas also celebrates the child found in each

individual and the desire for peace. Falling during the same month as

the Jewish observance of Chanukah or Hanukkah (the Feast of Lights)

and the African-American celebration of Kwanzaa, the season of

Christmas serves as a time of celebration, feasting, and a search

for miracles.

While Christmas generally is considered the celebration of

Jesus’s birth, the early Puritans, who settled the New England region,

refused to celebrate the occasion. Disagreeing with the early church

fathers who established the holiday around a pagan celebration for

easy remembrance by the poor, the Puritans considered the obser-

vance secular in nature. Set during the winter solstice when days grow

dark early, Christmas coincides with the Roman holiday of Saturnalia;

the date, December 25, marks the celebration of Dies Natalis Invicti

Solis, or the birth day of the Unconquered Sun by the Romans.

CHRISTMAS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

504

An early Coca-Cola advertising poster featuring the company’s

famed Santa Claus.

Puritans believed that these pagan customs, which included no work,

feasting, and gift giving, were inappropriate for the celebration of the

Lord’s birth. While the northern colonists did not observe the day, the

southern colonists celebrated in much the same style as their British

counterparts—with banquets and family visits. Firecrackers or guns

were used to welcome the Christ Child at midnight on Christmas. The

residents of New York (New Amsterdam) celebrated the season in a

similar fashion as their Dutch ancestors had with St. Nicholas Day

(December 6), established to honor the patron saint of children.

Gradually, all observances became centered around the date Decem-

ber 25, with traditions becoming mixed and accepted between differ-

ent ethnic backgrounds.

With these strong ties to religion, Christmas serves an important

role for the Christian faith. The four Sundays before Christmas, or the

season of Advent, prepares the congregation for the arrival of the

Messiah. With wreathes consisting of greenery, four small purple

candles, and one large white candle, church members are reminded of

the four elements of Christianity: peace, hope, joy, and love. This

season of the church year ends with the lighting of the Christ candle

on Christmas morning, signalling the two week period of Christmastide.

Nativity scenes, or creches, adorn altars as a visual reminder of the

true meaning of Christmas.

While attendance at church services and midnight masses seems

commonplace, the first visible sign of the Christmas season appears in

the decoration of the home. Some families decorate the outside of

their home with multi-strings of colored lights, while others focus

their decorations around an evergreen tree of spruce, fir, or cedar. In

the 1960s, a new type of Christmas tree appeared on the market which

allows families to prepare for the season early and leave their

decorations up well into the New Year. Artificial trees have ranged in

style from the silver aluminum trees (1960s) to the imitation spruce

and snow-covered fir. A custom attributed to Martin Luther, the

Christmas tree often appears decorated with lights and ornaments

consisting of family heirlooms—a central theme which had meaning

to the family—or religious symbols. Christmas trees became widely

used after 1841 when Prince Albert placed one for his family’s use at

Windsor Castle. Originally, the Christmas tree was decorated with

candles. With the introduction of electricity, however, strings of small

and large bulbs ranging in color from white to multi-color illumine the

tree. The lighting of the tree dates back to the days when light was

used to dispel the evil found in darkness. Around the base of the tree,

gifts, creches, or large scale displays of Christmas villages represent

some important memory or tradition in the family’s heritage or life.

The Christmas tree is not the only greenery used during the

holiday season. Wreaths of holly, fir, and pine appear on doors and in

windows of homes. Each represents a part of the mystical past or

ancestors’ beliefs. The holly, which the ancients used to protect their

home from witches, also represents the crown of thorns worn by Jesus

at His crucifixion. The evergreen fir and pine represent everlasting

life. Mistletoe, a Druid tradition and hung in sprigs or as a Kissing

Ball, brings the hope of a kiss to the one standing beneath the spray.

The red and white flowering poinsettia, native to Central American

countries and brought to the United States by Dr. Joel Poinsett,

represents the gift of a young Mexican peasant girl to the Christ Child.

Christmas serves as a time when gifts are exchanged between

family and friends. This custom, while attributed to the gifts brought

by the Magi to the Christ Child, can be traced to the earlier celebration

of Saturnalia by the Romans. While the name varies with the country

of origin, the bearer of gifts to children holds a special place in

people’s hearts and comes during the month of December. The most

recognized gift-giver is based on Saint Nicholas, a bishop of Myra in

300 to 400 A. D., and the tradition was brought to America by the

Dutch of New York. Saint Nicholas’ appearance went undefined until

the early 1800s when he appeared in the stories of Washington Irving.

While Irving’s stories would include general references to Saint

Nicholas, Clement Clark Moore would give Americans the image

most commonly accepted. A professor of Divinity, in 1822 Moore

wrote ‘‘A Visit from Saint Nicholas,’’ also known as ‘‘The Night

Before Christmas,’’ as a special gift for his children. A friend, hearing

the poem, had it published anonymously the following year in a local

newspaper. Telling the story of the visit of Saint Nicholas, the poem

centers around a father’s experience on Christmas Eve; the poem

reveals and establishes a new vision of St. Nicholas. St. Nicholas

drives a miniature sleigh pulled by eight reindeer named Dasher,

Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donner, and Blitzen. Moore’s

description of Saint Nicholas describes the clothing worn by the man.

‘‘He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot, / And his clothes

were all tarnished with ashes and soot; / A bundle of toys he had flung

CHRISTOENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

505

on his back, / And he looked like a peddler just opening his sack.’’ For

the nineteenth century reader, the image of someone dressed like a

peddler with a bag of toys on his back could be easily visualized.

Moore did not end his description here, but gave a physical

description of the man as well. With twinkling eyes and dimples,

Saint Nicholas has a white beard which gives him a grandfatherly

appearance. In addition, Moore added: ‘‘He had a broad face and a

little round belly, / That shook, when he laughed, like a bowlful of

jelly.’’ The jolly gentleman of childhood Christmas fantasy has

become a reality. The description is so vivid that artists began to

feature this portrait of Saint Nicholas in their seasonal drawings. In

1881 Thomas Nast, a cartoonist in New York, would define the

gentleman and give him the characteristics for which he has become

known. Saint Nicholas’s name has changed to the simplified Santa

Claus and has become a lasting part of the Christmas tradition.

Santa Claus and his miraculous gifts have played such a part of

the Christmas celebration that many articles, movies, and songs have

been written about the character. The most famous editorial ‘‘Yes,

Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus,’’ appeared in The Sun in 1897 after a

child wrote asking about Santa’s existence. The response to the

child’s letter is considered a Christmas classic, with many newspa-

pers repeating the editorial on Christmas Day. This same questioning

regarding Santa Claus’ existence is portrayed in the film Miracle on

34th Street (1947), where a young girl learns not only to believe in

what can be seen but also in the unseen. Johnny Marks adds to the

legend of Santa Claus and his reindeer with the song ‘‘Rudolph the

Red-nosed Reindeer’’ (1949), which is performed most notably by

Gene Autry. This song, while using Moore’s names for the reindeer,

adds a new one, Rudolph, to the lexicon of Santa Claus.

The spirit of Santa Claus has not only given the season a defining

symbol, but has also created a season with an emphasis on commer-

cialization. Santa’s bag of toys means money for the merchants.

Christmas items and the mention of shopping for Christmas may

begin as early as the summer, with Christmas tree displays appearing

in retail stores in September and October. Christmas has become so

important to the business world that some specialty stores dedicate

their merchandise to promoting the business of Christmas year-round.

Shopping days are counted, reminders are flashed across the evening

news, and advertisements are placed in newspapers. The images of

Christmas not only bring joy, but also anxiety as people are urged to

shop for the perfect gift and to spend more money.

While the season of Christmas symbolizes various things to

different people, the Christ Child and Santa Claus represent two

differing views of the celebration. The traditions and customs of the

immigrant background have merged and provide the season with

something for everyone. Adding to the celebration the Jewish festival

Chanukah, and the African-American celebration Kwanzaa, the sea-

son of Christmas seems to run throughout the month of December.

With the merging of the sacred and the pagan, magic is revisited and

dreams are fulfilled while money is spent in the never-ending cycle

of giving.

—Linda Ann Martindale

F

URTHER READING:

Barnett, James H. The American Christmas: A Study in National

Culture. New York, Macmillan Company, 1954.

Barth, Edna. Holly, Reindeer and Colored Lights: The Story of the

Christmas Symbols. New York, Seabury Press, 1971.

Moore, Clement C. The Night Before Christmas. New York, Harcourt

Brace and Company, 1999.

Nissenbaum, Stephen. The Battle for Christmas. New York, Alfred

A. Knopf, 1997.

Weinecke, Herbert H. Christmas Customs Around the World. Phila-

delphia, Westminster Press, 1959.

Christo (1935—)

The most well-known environmental artist of this half century,

Christo first captured the public’s attention in the 1960s by wrapping

large-scale structures such as bridges and buildings. In the following

three decades his artworks became lavish spectacles involving mil-

lions of dollars, acres of materials, and hundreds of square miles of

land. His projects are so vast and require so much sophisticated

administration, bureaucracy, and construction, that he is best thought

of as an artist whose true medium is the real world.

Christo Vladimiorov Javacheff was born in Gabrovo, Bulgaria,

into an intellectually enlightened family. After study in the art

academy in Bulgaria, his work for the avant-garde Burian Theatre in

1956 proved decisive. Christo began wrapping and packaging ob-

jects—a technique called ‘‘empaquetage’’—a year after his move to

Paris in 1957. Empaquetage was a reaction to the dominance of

tachiste painting, the European version of American abstract expres-

sionism. Conceptual in nature, wrapping isolates commonplace ob-

jects and imbues them with a sense of mystery. Christo often used

transparent plastic and rope to wrap cars, furniture, bicycles, signs

and, for brief periods, female models.

In Paris, Christo became acquainted with the Nouveau Réalistes

group, which was interested in using junk materials and with the

incorporation of life into art. Soon his artworks utilized tin cans, oil

drums, boxes, and bottles. He married Jeanne-Claude de Guillebon,

who became his inseparable companion, secretary, treasurer, and

collaborator. So close is their partnership that Christo’s works often

bear Jeanne-Claude’s name as well as his own.

The early sixties witnessed Christo’s first large-scale projects.

Several of these involved barrels, the most famous of which was Iron

Curtain—Wall of Oil Drums (1962). A response to the then-new

Berlin wall, it consisted of more than two hundred barrels stacked

twelve feet high. It effectively shut down traffic for a night on a Paris

street. As the sixties wore on, and particularly after Christo moved to

New York, his works became larger and even more conceptual. He

created Air Packages (large sacs of air that sometimes hovered over

museums), wrapped trees, and even packaged a medieval tower. In

1968 Christo wrapped two museum buildings, the Künsthalle Muse-

um in Bern, Switzerland, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in

Chicago. The latter required sixty-two pieces of brown tarpaulin and

two miles of brown rope.

About this time, Christo’s attention turned to the vast spaces of

landscape. For Wrapped Coast—One Million Square Feet, Little Bay,

Australia (1969) he covered a rocky, mile-long stretch of coastline

with a million square feet of polythene sheeting and thirty-six miles of

CHRISTO ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

506

The ‘‘Wrapped Trees’’ project by Christo and his wife Jeanne-Claude in the park of the Foundation Beyeler in Riehen, Switzerland, 1998.

rope. The work was the first of his projects in which Christo had to

solve problems connected to government agencies and public institu-

tions. Controversy erupted when nurses on the privately owned land

protested because they thought that hospital money was being divert-

ed and that a recreational beach would be shut down. Actually,

Christo paid for the project himself and allowed for the beach to

remain open.

While teaching in Colorado, Christo became intrigued by the

Rocky Mountain landscape. Valley Curtain (1971-72, Rifle Gap,

Colorado) was composed of two hundred thousand square feet of

nylon hung from a cable between two cliffs. The bright orange nylon

curtain weighed four tons. Organizational, economic, and public

relations problems delayed construction for a time, but these were

exactly the challenges Christo and Jeanne-Claude had become so

adept in solving. To raise the $850,000 needed, the couple created the

Valley Curtain Corporation. As would become customary, Christo’s

drawings, plans, models, and photographs of Valley Curtain were

sold as art objects to raise money for building the massive artwork.

The first curtain was almost instantly ripped to pieces by high winds; a

union boss had told his workers to quit for the day before it was

properly secured. The second curtain was ruined by a sandstorm the

day after it was hung, but not before it was unfurled to the cheers of

media, news crews, and onlookers. A half-hour documentary was

made to register the course of the work’s construction. In all of

Christo’s projects, photography and documentary film are used

extensively to record the activities surrounding what are essentially

temporary structures.

For his next project, Running Fence (1976), Christo raised two

million dollars through the sale of book and film rights and from

works of art associated with the project. Christo obtained the permis-

sion of fifty-nine private ranchers and fifteen government organiza-

tions. Ironically, the strongest opposition came from local artists who

regarded the project as a mere publicity stunt. Christo then became a

passionate lobbyist for his project, appearing at local meetings and

agency hearings. Winding through Marin and Sonoma counties, the

eighteen-foot-high fence traversed twenty-four miles over private

ranches, roads, small towns, and subdivisions on its way to a gentle

descent into the Pacific Ocean. Open-minded viewers found it lyrical-

ly beautiful; indeed, beauty is one of Christo’s unabashed aims.

Surrounded Islands, Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida,

1980-83 was Christo’s major work of the eighties and involved

floating rafts of shocking pink polypropane entirely enclosing eleven

small islands. It required more than four hundred assistants and $3.5

million to complete. Sensitive to the environment, Christo decided

not to surround three islands because they were home to endangered

manatees, birds, and plants. Even so, Christo and Jeanne-Claude still

CHRYSLER BUILDINGENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

507

had to contend with lawsuits, lawyers, and public groups. Though

Surrounded Islands extended for eleven miles and traversed a major

city, it was strikingly lovely. Like Running Fence, Surrounding

Islands existed for only two weeks.

Christo staged The Umbrellas, Japan—U.S.A. 1984-91 simulta-

neously in the landscapes north of Tokyo and of Los Angeles.

Roughly fifteen hundred specially designed umbrellas (yellow ones

in California, blue ones in Japan) dotted the respective countrysides

over areas of several miles. Only twenty-six landowners had to be

won over in California; in Japan, where land is even more precious,

the number was 459. The umbrellas were nearly twenty feet high and

weighed over five hundred pounds each. Having cost the artist $26

million to produce, the umbrellas stood for only three weeks begin-

ning on October 9, 1991. Christo ended the project after a woman in

California was killed when high winds uprooted an umbrella. Dur-

ing the dismantling of the umbrellas in Japan, a crane operator

was electrocuted.

Altogether, Christo’s art involves manipulating public social

systems. As the artist has said, ‘‘We live in an essentially economic,

social, and political world.... I think that any art that is less political,

less economical, less social today, is simply less contemporary.’’

—Mark B. Pohlad

F

URTHER READING:

Baal-Teshuva, Jacob. Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Cologne, Benedikt

Taschen, 1995.

Christo: The Reichstag and Urban Projects. Munich, Prestel, 1993.

Laporte, Dominique G. Christo. Translated from the French by Abby

Pollak. New York, Pantheon Books, 1986.

Spies, Werner. Introduction to Christo, Surrounded Islands, Biscayne

Bay, Greater Miami, Florida, 1980-83, by Christo. New York,

Abrams, 1985.

Vaizey, Marina. Christo. New York, Rizzoli, 1990.

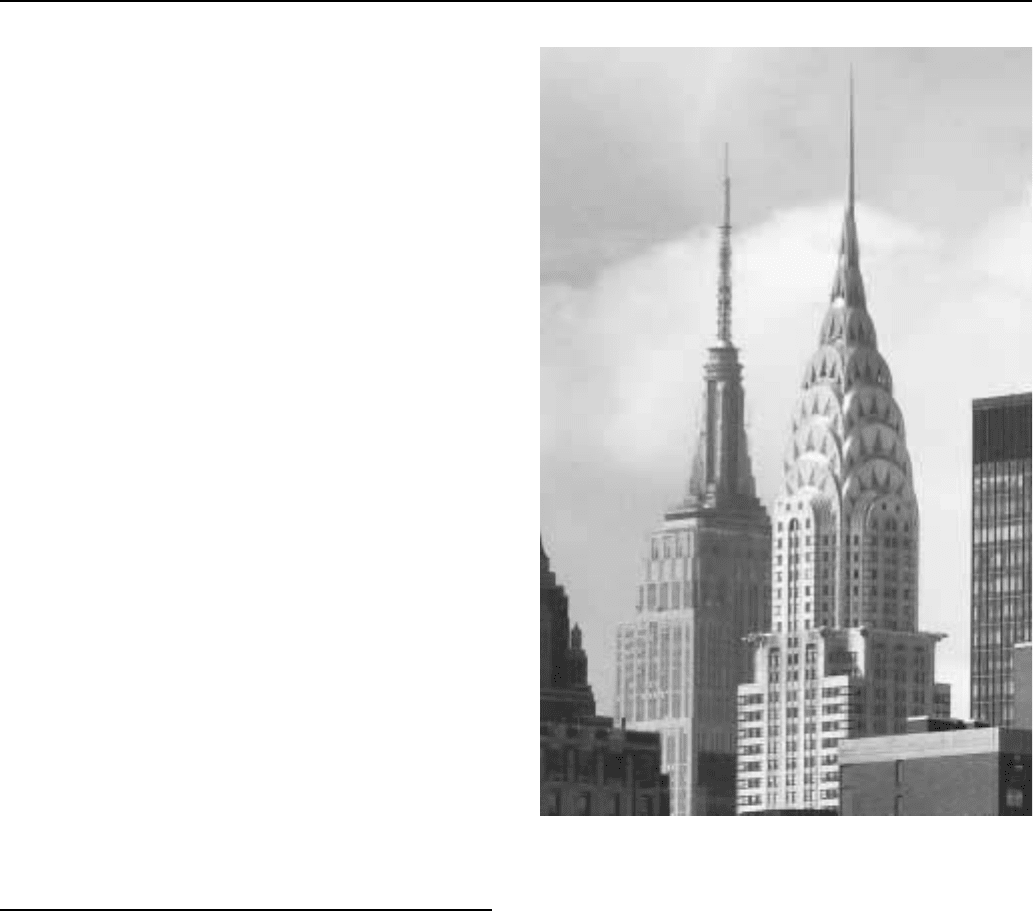

Chrysler Building

A monument to the glitzy Jazz Age of the 1920s, the Chrysler

Building in New York City is America’s most prominent example of

Art Deco architecture and the epitome of the urban corporate head-

quarters. This unabashedly theatrical building, which was briefly the

world’s tallest after its completion in 1930, makes an entirely differ-

ent statement than its nearby competitor, the Empire State Building.

The Chrysler Building’s appeal was summarized by architectural

critic Paul Goldberger, who wrote, ‘‘There, in one building, is all of

New York’s height and fantasy in a single gesture.’’

The Chrysler Building was originally designed for real estate

speculator William H. Reynolds by architect William Van Alen. In

1928, Walter Percy Chrysler, head of the Chrysler Motor Corpora-

tion, purchased the site on the corner of Lexington Avenue and 42nd

Street in midtown Manhattan, as well as Van Alen’s plans. But those

plans were changed as the design began to reflect Chrysler’s dynamic

personality. The project soon became caught up in the obsessive quest

for height that swept through the city’s commercial architecture in the

1920s and 1930s. Buildings rose taller and taller as owners sought

both to maximize office space as well as to increase consumer

visibility. Van Alen’s initial design projected a 925-foot building with

The Chrysler Building (foreground)

a rounded, Byzantine or Moorish top. At the same time, however, Van

Alen’s former partner, H. Craig Severance, was building the 927-foot

Bank of the Manhattan Company on Wall Street. Not to be outdone,

Van Alen revised his plans, with Chrysler’s blessing, to include a new

tapering top that culminated in a spire, bringing the total height to

1,046 feet and establishing the Chrysler Building as the world’s

tallest. The plans were kept secret, and near the end of construction

the spire was clandestinely assembled inside the building, then

hoisted to the top. The entire episode defined the extent to which the

competition for height dominated architectural design at the time. The

Chrysler Building’s reign was brief, however; even before it was

finished, construction had begun on the Empire State Building, which

would surpass the Chrysler by just over two-hundred feet.

The finished building is a dazzling display of panache and

corporate power. The most famous and notable aspect of the Chrysler

Building is its Art Deco decoration. With its polychromy, zigzag

ornamentation, shining curvilinear surfaces, and evocation of ma-

chines and movement, the Art Deco style—named after the 1925

Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes

in Paris—provided Van Alen with a means to express the exuberance

and vitality of 1920s New York, as well as the unique personality of

CHUCK D ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

508

the building’s benefactor. The interior of the Chrysler Building

reflects the company’s wealth. In the unique triangular lobby, remi-

niscent of a 1930s movie set, the lavish decorative scheme combines

natural materials like various marbles, onyx, and imported woods

with appropriate machine-age materials like nickel, chrome, and

steel. Outside, a white brick skin accentuated by gray brick trim was

laid over the building’s steel frame in a pattern that emphasized the

building’s verticality. Steel gargoyles in the form of glaring eagles—

representing both America and hood ornaments from Chrysler Com-

pany automobiles—were placed at the corners of the building’s

highest setback. (These gargoyles became famous after a photo of

photographer Margaret Bourke-White standing atop one of them was

widely circulated). The crowning achievement of the building, both

literally and figuratively, is the spire. A series of tapering radial

arches, punctuated by triangular windows, rise to a single point at the

top. The spire’s stainless steel gleams in the sun. The arches at the

spire’s base were based on automobile hubcaps. In fact, the entire

building was planned with an elaborate iconographic program, in-

cluding radiator cap gargoyles at the fourth setback, brick designs

taken from Chrysler automobile hubcaps, and a band of abstracted

autos wrapping around the building. The use of such company-

specific imagery incorporated into the building’s design anticipated

the postmodern architecture of the 1980s.

The Chrysler Building was not the first corporate headquarters

specifically designed to convey a company’s image, but it may have

been the most successful. The unique building was a more effective

advertising tool for the Chrysler Company than any billboard, news-

paper, or magazine ad. The Chrysler Building, with its shining

telescoped top, stood out from the rather sedate Manhattan skyscrap-

ers. While some observers see the building as kitsch or, in the words

of critic Lewis Mumford, ‘‘inane romanticism,’’ most appreciate its

vitality. Now one of the world’s favorite buildings, the Chrysler

Building has become an American icon, symbolizing the pre-Depres-

sion glamour and the exuberant optimism of the Jazz Age.

—Dale Allen Gyure

F

URTHER READING:

The Chrysler Building. New York, Chrysler Tower Corporation, 1930.

Douglas, George H. Skyscrapers: A Social History of the Very Tall

Building in America. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland &

Company, 1996.

Goldberger, Paul. The Skyscraper. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Reynolds, Donald Martin. The Architecture of New York City. New

York, Macmillan Publishing Company, 1984.

Chuck D (1960—)

The primary rapper in one of the most significant hip-hop groups

in the genre’s history, Chuck D founded the New York City-based

Public Enemy in order to use hip-hop music as an outlet to dissemi-

nate his pro-Black revolutionary messages. Because of the millions of

albums Public Enemy sold and the way the group changed the

landscape of hip-hop and popular music during the late-1980s, Public

Enemy’s influence on popular music specifically, and American

culture in general, is incalculable.

Chuck D (born Carlton Ridenhour August 1, 1960) formed

Public Enemy in 1982 with fellow Long Island friends Hank Shocklee

and Bill Stepheny, both of whom shared Chuck D’s love of politics

and hip-hop music. In 1985, a Public Enemy demo caught the

attention Def Jam label co-founder Rick Rubin, and by 1986 Chuck D

had revamped Public Enemy to include Bill Stepheny as their

publicist, Hank Shocklee as a producer, Flavor Flav as a second MC,

Terminator X as the group’s DJ and Professor Griff as the head of

Public Enemy’s crew of onstage dancers. Public Enemy burst upon

the scene in 1987 with their debut album Yo! Bum Rush the Show, and

soon turned the hip-hop world on its head at a time when hip-hop

music was radically changing American popular music. Chuck D’s

early vision to make Public Enemy a hotbed of extreme dissonant

musical productions and revolutionary politics came into fruition

with the release of 1988’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us

Back. Recognized by critics at Rolling Stone, SPIN, The Source and

the Village Voice as one of most significant works of popular music of

the twentieth century, It Takes a Nation. . . took music to new

extremes. That album combined furiously fast rhythms, cacophonous

collages of shrieks and sirens, and Chuck D’s booming baritone

delivery that took White America to task for the sins of racism

and imperialism.

Chuck D once remarked that hip-hop music was Black Ameri-

ca’s CNN, in that hip-hop was the only forum in which a Black point

of view could be heard without being filtered or censored. As the

leader of Public Enemy, a group that sold millions of albums

(many to White suburban teens) Chuck D was one of the only

oppositional voices heard on a widespread scale during the politically

conservative 1980s.

Public Enemy’s commercial and creative high point came during

the late 1980s and early 1990s. The group recorded their song ‘‘Fight

the Power’’ for Spike Lee’s widely acclaimed and successful 1989

film Do the Right Thing, increasing Public Enemy’s visibility even

more. After the much-publicized inner group turmoil that resulted

from anti-Semitic remarks publicly made by a group member, Chuck

D kicked that member out, reorganized the group and went to work on

the biggest selling album of Public Enemy’s career, Fear of a

Black Planet.

By then, Chuck D had perfected the ‘‘Public Enemy concept’’ to

a finely-tuned art. He used Public Enemy’s pro-Black messages to

rally and organize African Americans, the group’s aggressive and

propulsive sonic attack to capture the attention of young White

America, and their high visibility to edge Chuck D’s viewpoints into

mainstream discourse. Throughout the 1990s, Chuck D appeared on

numerous talk shows and other widely broadcast events.

Taking advantage of his notoriety, Chuck D often lectured at

college campuses during the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s. He

became a political election correspondent for music video network

MTV and, in 1997, he published a book on race and politics in

America titled Fight the Power.

In a musical genre driven by novelty and innovation, Public

Enemy’s—and Chuck D’s—influence and commercial success began

to wane by the mid-1990s. In 1996 he released the commercially

unsuccessful solo album, Autobiography of Mista Chuck. But unlike

many artists who change their formula when sales decline, Chuck D