Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHEERSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

489

Ted Danson (second from right) and Shelley Long (right) with the rest of the cast in a scene from the sitcom Cheers.

devised one prank which ended with Cliff, Carla, Norm, and Woody

on an endless cross-country bus trek. The sadism reached its zenith

during a petty rivalry throughout the run of the series with a

competing bar, Gary’s Olde Time Tavern. The feud culminated

during the final season, when the Cheers gang convinced the smug

Gary that an investor would pay him $1 million for his land. Gary

gleefully took a wrecking ball to his establishment.

Cheers ended in 1993 after 11 seasons and 269 episodes. Series

co-creators Glen and Les Charles had once confessed their ideal

Cheers ending: Sam and Diane admit they can’t live with or without

each other and take each other’s life in a murder-suicide. In the actual

finale, Diane did return to the bar, contemplating a reconciliation with

Sam, but the two finally realized they were no longer suitable for each

other. In other developments, upwardly mobile Rebecca impulsively

married a plumber, Cliff won a promotion at the post office, and—

miracle of miracles—Norm finally got a steady job. In the last

moments of the series, the regulars sat around the bar to discuss the

important things in life. As the show faded out one final time, Sam

walked through the empty bar, obviously the most important thing to

him, at closing time.

There has been no consensus as to the best single episode of

Cheers. Some prefer the Thanksgiving episode at Carla’s apartment,

ending in a massive food fight with turkey and all the trimmings in

play. Others recall Cliff’s embarrassing appearance on the Jeopardy!

game show, with a cameo from host Alex Trebek. There was also the

penultimate episode, where the vain Sam revealed to Carla that his

prized hair was, in fact, a toupee. Perhaps the finest Cheers was the

1992 hour-long episode devoted to Woody’s wedding day, a classic,

one-set farce complete with a Miles Gloriosus-like soldier, horny

young lovers, and a corpse that wouldn’t stay put.

Cheers was inspired by the BBC situation comedy Fawlty

Towers (1975, 1979), set at a British seaside hotel run by an

incompetent staff. That show’s creator/star, John Cleese, appeared on

Cheers in an Emmy-winning 1987 cameo as a marriage therapist who

went to great lengths to convince Sam and Diane that they were

thoroughly incompatible. Co-creator James Burrows was the son of

comedy writing great Abe Burrows, responsible for the long-running

1940s radio comedy Duffy’s Tavern (‘‘where the elite meet to eat’’), a

program set in a bar which was also noted for its eccentric characters

and top-notch writing.

Grammer reprised his role of Frasier Crane in the spin-off series

Frasier, which debuted in the fall of 1993 to high ratings and critical

acclaim. The series won Best Comedy Emmy awards during each of

its first five seasons.

—Andrew Milner

CHEMISE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

490

FURTHER READING:

Bianculli, David. Teleliteracy. New York, Ungar, 1993.

Javna, John. The Best of TV Sitcoms: The Critics’ Choice: Burns and

Allen to the Cosby Show, the Munsters to Mary Tyler Moore. New

York, Harmony Books, 1988.

Chemise

Fashion designer Cristobal Balenciaga’s ‘‘chemise’’ dramati-

cally altered womenswear in 1957. Since Christian Dior’s New Look

in 1947, women wore extremely narrow waists, full wide skirts, and

fortified busts. The supple shaping of Balenciaga’s chemise, which

draped in a long unbroken line from shoulder to hem, replaced the

hard armature of the New Look. The chemise was a hit not only in

couture fashion, where Yves Saint Laurent showed an A-line silhou-

ette in his first collection for Dior, but also in Middle America, where

Americans copied the simple shape which required far less construc-

tion and was therefore cheaper to make. Uncomfortable in the body

conformity of the New Look, women rejoiced in a forgiving shape

and the chemise, or sack dress, became a craze. The craze was

parodied in an I Love Lucy episode in which Lucy and Ethel pine for

sack dresses but end up wearing feed sacks.

—Richard Martin

F

URTHER READING:

Chappell, R. ‘‘The Chemise—Joke or No Joke . . . ’’ Newsweek.

May 5, 1959.

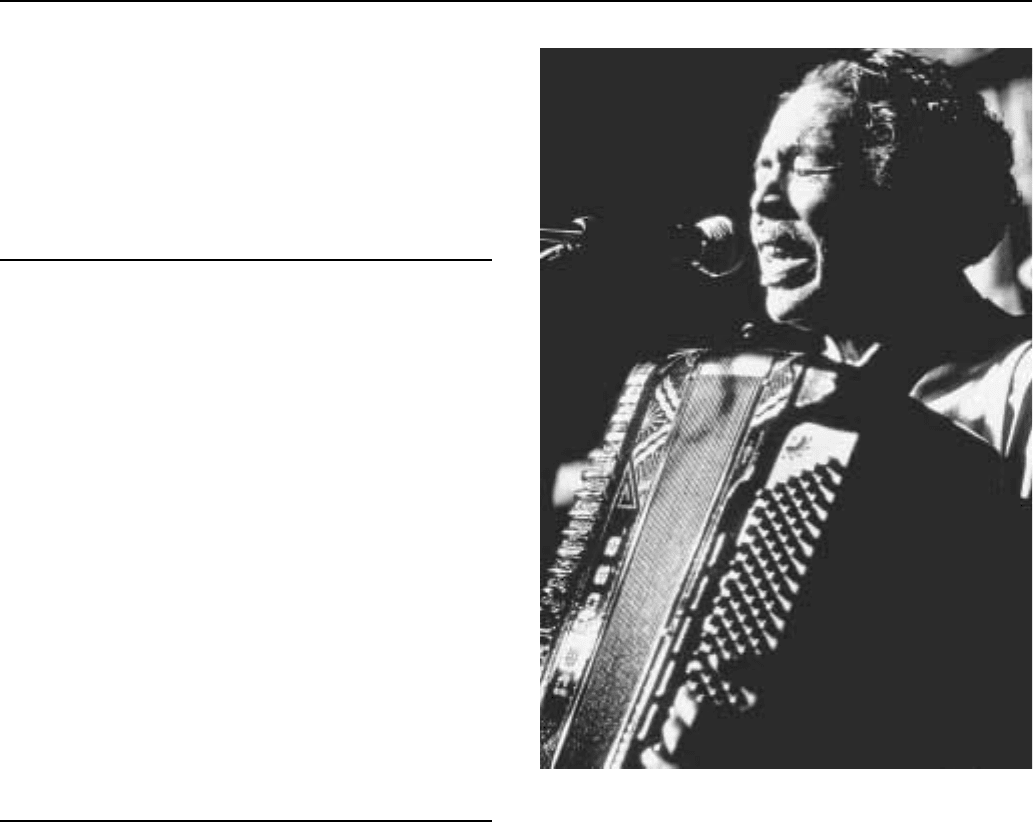

Chenier, Clifton (1925-1987)

Although he passed away in the late 1980s, Clifton Chenier

remains the undisputed King of Zydeco. It was Clifton Chenier who

took the old dance music of the rural Louisiana Creoles and added

blues, soul, and country and stirred it all up until it became what we

now call zydeco. His name was virtually synonymous with this type

of music, and he became the most respected and influential zydeco

artist in the world. Chenier popularized the use of the big piano key

accordion, which allowed him to play a diversity of styles within the

expanding zydeco genre. He pushed the envelope with energetic

renditions of French dance standards or newer tunes transformed

through zydeco’s characteristic syncopated rhythms and breathy

accordion pulses. Chenier assembled a band of musicians who were

not just good but were the best in the business; they were a close-knit

group that became legendary for high intensity concerts lasting four

hours straight without a break. And there at the helm was Chenier,

gold tooth flashing like the chrome of his accordion, having the time

of his life.

Clifton Chenier was born on June 25, 1925 into a sharecropping

family near Opelousas, Louisiana. He became dissatisfied early on

with the farming life, and headed west with his brother Cleveland to

work in the oil refineries around Port Arthur, Texas. Having learned

from his father how to play the accordion, Chenier decided to attempt

a transition toward performing as a professional. Driving a truck

during the day and playing music at night, Chenier, along with his

Clifton Chenier

brother on rubboard, soon became a popular attraction in local

roadhouses. Often the pair comprised the entire band, and this was

zydeco in its purest form, an extension of the earlier French ‘‘la-la’’

music played at Creole gatherings throughout southwest Louisiana,

now taken to new heights and amplitude for a wider audience.

Chenier credits Rhythm and Blues (R & B) artist Lowell Fulson with

showing him how to be a good performer, always mixing it up and

pleasing the crowd—these lessons stayed with him for the rest of his

career. One of his earliest recordings, ‘‘Ay-Tete-Fee’’ became a hit

record in 1955.

During the early 1960s, Chenier began recording albums for

Chris Strachwitz’s west coast Arhoolie Records, where he eventually

became that label’s biggest seller. His first Arhoolie album, Louisiana

Blues and Zydeco, was a hard-fought compromise between the

producer’s desire for traditional zydeco, and Chenier’s wish to cross

over into soul and the potentially even more lucrative R & B. The final

version of the album represented a mixture of these two directions and

included for the first time on record a blues number sung in French.

Following that release, Chenier’s popularity soared, and a frenetic

schedule of touring ensued. Over the next few years, Clifton Chenier

would realize the wisdom of Strachwitz’s insistence on sticking close

to unadulterated zydeco, which was already a musical gumbo of

various ingredients, and he became more of a traditionalist himself,

CHERRY AMESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

491

championing Creole culture and the French language wherever

he played.

All through the 1970s Chenier and his Red Hot Louisiana Band

traveled the ‘‘crawfish circuit’’ between New Orleans and Houston,

playing in parking lots, in clubs and bars, and in Catholic church halls

where zydeco dances were sponsored with increasing frequency. This

kept the music rooted in its place of origin, and served to accentuate

the rising awareness of Creole ethnic identity. When touring further

afield, he became a regular attraction at blues festivals around the

country and even made a successful sweep through Europe. It was

about this time that he began wearing a crown on stage, dubbing

himself the ‘‘King of Zydeco.’’ His musical performances were

featured in several documentary films, including Hot Pepper and J’ai

Ete au Bal. In 1984, Chenier won a Grammy Award for the album I’m

Here, and was now a nationally, and even internationally recognized

musician. But his health had gone downhill. Plagued by poor circula-

tion, he was diagnosed with diabetes and had portions of both legs

amputated. After a final, tearful performance at the 1987 Zydeco

Festival in Plaisance, Louisiana, he canceled a scheduled tour due to

illness, and on December 12, 1987, at the age of 62, Clifton died in a

Lafayette hospital. His legacy lives on, as does his fabled Red Hot

Louisiana Band, now led by son C.J. Chenier, an emerging zydeco

artist in his own right.

There has never been anyone, before or since, who could play the

accordion like Clifton Chenier. While his vocal renditions of songs

were truly inspired, his voice always served as accompaniment to the

accordion, rather than the other way around. Besides having talent

and the gift of making music, he was able to establish a warm and

unaffected rapport with his audience. He knew who he was, he loved

what he was doing, and he genuinely enjoyed people. Fans and critics

alike are unreserved in their emphatic assessment of Clifton Chenier’s

artistry and his place in the annals of popular music. And musicians in

the Red Hot Louisiana Band fondly recall the feeling of playing with

this soulful master who had so much energy and who injected such

pure feeling into his music. As former member Buckwheat Zydeco

put it, ‘‘Clifton Chenier was the man who put this music on the map.’’

—Robert Kuhlken

F

URTHER READING:

Broven, John. South to Louisiana: The Music of the Cajun Bayous.

Gretna, Louisiana, Pelican Publishing, 1983.

Tisserand, Michael. The Kingdom of Zydeco. New York, Arcade

Publishing, 1998.

Cher

See Sonny and Cher

Cherry Ames

Packed with wholesome values and cheerfulness, the Cherry

Ames nursing mystery series was popular with girls in the mid-

twentieth century. Cherry, a dark-haired, rosy-cheeked midwestern

girl, was always perky and helpful, ready to lend a hand in a medical

emergency and solve any mysteries that might spring up along the

way. The books never claimed to have literary quality. Their creator,

Helen Wells, admitted they were formulaic—not great literature, but

great entertainment.

The series consisted of 27 books published by Grosset and

Dunlap between 1943 and 1968, authored by Helen Wells and Julie

Tatham. Aggressively marketed to girls, the books contained all sorts

of consumer perks: the second book in the series was offered free with

the first, and each book showed a banner on the last page advertising

the next exciting adventure. The first 21 volumes were issued in

colorful dust jackets showing Cherry in her uniform, proclaiming ‘‘It

is every girl’s ambition at one time or another to wear the crisp

uniform of a nurse.’’ (Indeed, this uniform was described over and

over, along with Cherry’s off-duty snappy outfits.) Early copies in the

series had yellow spines, but the format was quickly changed to green

spines, probably to avoid confusion with the ubiquitous Nancy Drew

books. There was also a companion volume written by Wells in 1959,

entitled Cherry Ames’ Book of First Aid and Home Nursing.

In the early years, the novels were patriotic, pro-nursing tales in

which Cherry called for other girls to join her and help win World War

II. The later books were mysteries, with Cherry as a girl sleuth. Titles

followed the format of Cherry Ames, Student Nurse and included

Cherry Ames, Cruise Nurse, Cherry Ames, Chief Nurse, Cherry

Ames, Mountaineer Nurse, among many others. Cherry’s nursing

duties brought her to such exotic locales as a boarding school, a

department store, and even a dude ranch.

Wells (1910-1986), the creator of the series and author of most

of the books, was no stranger to girls’ series—she was also the author

of the Vicki Barr flight attendant series and other books for girls.

Tatham (1908—), wrote a few books in the middle of the series.

Under the pseudonym Julie Campbell she also authored both the

Trixie Belden and Ginny Gordon series.

The Cherry Ames series became internationally popular, with

editions published in England, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and

Japan. In England, books spawned a set of Cherry Ames Girls’

Annuals. There was a Parker Brothers board game produced in 1959,

‘‘Cherry Ames’ Nursing Game,’’ in which players vie to be the first to

complete nursing school.

By the 1970s, the Cherry Ames books were out of print and were

being phased out of libraries. The character had a rebirth in the 1990s,

however, when author and artist Mabel Maney created a series of

wickedly funny gay parodies of the girl-sleuth series books, bringing

out their (almost certainly unintentional) lesbian subtext. In her first

book, The Case of the Not-So-Nice Nurse, the ‘‘gosh-golly’’ 1950s

meet the ‘‘oh-so-queer’’ 1990s when lesbian detectives ‘‘Cherry

Aimless’’ and ‘‘Nancy Clue’’ discover more than just the answer to

the mystery.

—Jessy Randall

F

URTHER READING:

Mason, Bobbie Ann. The Girl Sleuth: A Feminist Guide. New York,

Feminist Press, 1975.

Parry, Sally E. ‘‘‘You Are Needed, Desperately Needed’: Cherry

Ames in World War II.’’ Nancy Drew and Company: Culture,

Gender, and Girls’ Series. Edited by Sherrie A. Inness. Bowling

Green, Ohio, Popular Press, 1997.

CHESSMAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

492

Chessman, Caryl (1921-1960)

In 1948, a career criminal named Caryl Chessman was charged

with being a ‘‘red light bandit’’ who raped and robbed couples in

lovers’ lanes near Los Angeles. Chessman was sentenced to death for

kidnapping two of the victims. His 12-year effort to save himself from

California’s gas chamber intensified the debate over capital punish-

ment. Chessman was successful in persuading various judges to

postpone his execution. This gave him time to make legal arguments

against his conviction and death sentence and to write Cell 2455

Death Row, an eloquent, bestselling book which purportedly de-

scribed the author’s life and criminal career.

The courts ultimately ruled against Chessman’s legal claims.

Many celebrities opposed his execution, including the Pope and

Eleanor Roosevelt. In February 1960, Chessman was granted a stay of

execution while the state legislature considered California Governor

Edmund Brown’s plea to abolish the death penalty. The Governor’s

effort, however, failed and Chessman was executed on May 2, 1960.

—Eric Longley

F

URTHER READING:

Brown, Edmund G., and Dick Adler. Public Justice, Private Mercy: A

Governor’s Education on Death Row. New York, Weidenfeld and

Nicolson, 1989.

Chessman, Caryl. Cell 2455 Death Row. New York, Prentice-

Hall, 1954.

Kunstler, William M. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt? The Original

Trial of Caryl Chessman. New York, William Morrow and

Company, 1961.

Largo, Andrew O. Caryl Whittier Chessman, 1921-1960: Essay and

Critical Bibliography. San Jose, California, Bibliographic Infor-

mation Center for the Study of Political Science, 1971.

The Chicago Bears

Like their home city, the Chicago Bears are a legendary team of

‘‘broad shoulders’’ and boundless stamina. One of the original

members of the National Football League (NFL), the Bears have

captured the attention of football fans since the heyday of radio. An

organization built on innovation and achievement both on and off the

field, the Bears’ remarkable victories earned them the nickname

‘‘Monsters of the Midway.’’ Bears players from Red Grange to

Walter Payton swell the ranks of the famous in football. By the 1990s

the Bears had achieved more victories than any other team in the NFL,

and have 26 members in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

In 1920, A.E. Staley, owner of the Staley Starch Works in

Decatur, Illinois, hired 25-year-old George Halas to organize a

professional football team. It was a daunting task. Halas approached

his former boss, Ralph Hay of the Canton Bulldogs, with the idea of

forming a professional football league. On September 17, 1920, Halas

met with 12 other team officials in Ralph Hay’s Humpmobile

dealership in Canton, Ohio, where they created the American Profes-

sional Football Association, the predecessor of the modern National

Football League. Of the 13 teams in the original league, only the

Bears and Cardinals remain in existence.

The Decatur Staleys—as the Bears were first called—played

their first game on October 3, 1920 at Staley Field. The Decatur team

was one of only a few to show a profit in the first year of operation.

Due to a recession in 1921, Staley was forced to withdraw support for

the team; but Halas assumed ownership and transferred the franchise

to Chicago. The team selected Wrigley Field as its home. Halas

compared the rough and tumble stature of his players to the baseball

stars of the Chicago Cubs, and renamed the team the Chicago Bears in

January 1922. The team colors, blue and orange, were derived from

Halas’s alma mater, the University of Illinois.

The first major signing for the team occurred in 1925, when

University of Illinois star Red Grange was hired by Halas. Grange

proved to be a strong gate attraction for the early NFL organization.

Although he only played in several games due to injury, he nonethe-

less managed to draw a game crowd of 75,000 in Los Angeles. During

the 1920s the team was a success on the field and at the gate, posting a

winning season every year except one.

The Bears quickly established a reputation as a tough, brawling

team capturing many hard-fought victories. New and exciting players

typified the team over succeeding seasons. Bronko Nagurski, a

tenacious runner requiring several players to take him down, joined

the illustrious 1930 lineup. An opposing coach was rumored to have

said the only way to stop Nagurshi was to shoot him before he went on

the field. Nagurski’s two-yard touchdown pass to Red Grange beat

Portsmouth in the 1932 championship game, the first football game

played indoors at Chicago Stadium. Sidney Luckman was recruited as

the premiere T-formation quarterback in 1939. With Luckman at

passer, the reinvigorated T-formation decimated the Washington

Redskins in a 73-0 title game rout. The Bears became the ‘‘Monsters

of the Midway,’’ and Luckman the most famous Jewish sports legend.

The fighting power of the Bears was strengthened by the addition of

unstoppable George ‘‘One Play’’ McAfee at halfback. He could score

running, passing, kicking, or receiving. Clyde ‘‘Bulldog’’ Turner was

selected as center and linebacker to assist McAfee. Turner proved to

be one of the fastest centers in NFL history.

Following up-and-down seasons during the 1950s, the Bears

regained notoriety by capturing another NFL title in 1963. This was

the first game broadcast on closed circuit television. The recruitment

of running back Gale Sayers in 1965 revitalized the Bears’ fighting

spirit. Sayers was an immediate sensation, setting an NFL scoring

record in his rookie year, and rushing records in subsequent years.

Sportswriters honored Sayers as the greatest running back in pro

football’s first half century. Standing in the shadow of Gale Sayers

was halfback Brian Piccolo. The two men were the first interracial

roommates in the NFL. Piccolo seldom played until Sayers’s knee

injury in 1968. When Sayers was awarded the George Halas Award

for pro football’s most courageous player in 1970, he dedicated the

award to Piccolo, who was dying of cancer. The bond between

Piccolo and Sayers was the subject of the television movie, Brian’s

Song, as well as several books. The Bears were bolstered by the

daunting presence of premiere middle linebacker Dick Butkus, who

became the heart and soul of the crushing Bears defense. George

Halas announced his retirement in 1968, after 40 seasons, with 324

wins, 15 loses, and 31 one ties. Halas remained influential in the

operation of the Chicago Bears and the NFL until his death in 1983.

The Bears played their final season game at Wrigley Field in

1970, and then moved to Soldier Field. Successive coaches Abe

Gibron, Jack Pardee, and Neil Armstrong produced mediocre seasons

with the Bears during the 1970s. The one bright spot during this

period was the recruitment of Walter Payton. Called ‘‘Sweetness’’

CHICAGO JAZZENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

493

because of his gentle manner, Payton led the NFL in rushing for five

successive years (1976-1980). After four coaching seasons Arm-

strong was replaced by former Bears tight end Mike Ditka. Under

Ditka’s command the Bears began winning again. In 1984, Walter

Payton broke Jim Brown’s career rushing record, and at the end of

1985 the team posted a 15-1 regular season mark, tying an NFL

record. On January 26, 1986, in their first Super Bowl appearance, the

Bears trounced New England 46-10, setting seven Super Bowl

records, including the largest victory margin and most points scored.

The 1990s were a milestone decade for the NFL Chicago

franchise: The team played its 1,000th game in 1993, and was the first

team to accumulate 600 victories. Mike Ditka was replaced as head

coach by Dave Wannstedt in 1993. Following the 1998 season

Wannstedt’s contract was terminated, and Jacksonville Jaguars de-

fensive coordinator Dick Jauron was named head coach. For almost

80 years, the Chicago Bears have been one of the powerhouse teams

in American football. Through all their ups and downs, they have

remained true to the city that has been their home—as a tough, proud,

all-American sports franchise, whose influence continues to be felt

throughout popular culture.

—Michael A. Lutes

F

URTHER READING:

Chicago Bears 1998 Media Guide. Chicago, Chicago Bears Public

Relations Department, 1998.

Mausser, Wayne. Chicago Bears, Facts and Trivia. Wautoma, Wis-

consin, E. B. Houchin, 1995.

Roberts, Howard. The Chicago Bears. New York, G.P. Putnam’s

Sons. 1947.

Vass, George. George Halas and the Chicago Bears. Chicago,

Regnery Press. 1971.

Whittingham, Richard. Bears: A Seventy-Five-Year Celebration.

Rochester, Minnesota, Taylor Publishing, 1994.

———. The Bears in Their Own Words: Chicago Bear Greats Talk

About the Team, the Game, the Coaches, and the Times of Their

Lives. Chicago, Contemporary Books. 1991.

———. The Chicago Bears: An Illustrated History. Chicago, Rand

McNally. 1979.

The Chicago Bulls

One of professional basketball’s dynasty teams, the Chicago

Bulls were led by perhaps the best basketball player ever, Michael

Jordan, from 1984-1993 and 1995-1998. When they began their first

season in 1966, the Bulls were a second-rate team, and continued to be

so, even posting a dismal 27-win record in 1984. That finish gave

them the opportunity to draft the North Carolina shooting guard, and

from then on, with his presence, the Bulls never failed to make the

playoffs. Jordan led the Chicago team to six National Basketball

Association championships, from 1991 to 1993 and again from 1996

to 1998. In the process, the team’s bull emblem and distinctive red and

black colors became as recognizable on the streets of Peking as they

were in the gang neighborhoods of Chicago’s South Side. Jordan

became a worldwide celebrity, better known than President Bill

Clinton. When he retired from basketball on January 13, 1999, his

Chicago news conference was broadcast and netcast live worldwide.

Fellow players Dennis Rodman and Scottie Pippen and team coach

Phil Jackson never became as well known as the legendary Jordan,

but were nonetheless important contributors during the Bulls’

championship years.

—Richard Digby-Junger

F

URTHER READING:

Bjarkman, Peter C. The Encyclopedia of Pro Basketball Team Histo-

ries. New York, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994, 98-114.

Broussard, Mark, and Craig Carter, editors. The Sporting News

Official NBA Guide, 1996-97 Edition. St. Louis, The Sporting

News Publishing Co., 1996.

Sachare, Alex, editor. The Official NBA Basketball Encyclopedia.

New York, Villard Books, 1994.

The Chicago Cubs

Secure in their roles as major-league baseball’s ‘‘lovable los-

ers,’’ the National League’s Chicago Cubs have not appeared in a

World Series since 1945 and have not won a World Series title since

1907. Despite a legacy of superstar players including 1990s home-run

hero Sammy Sosa, 1980s MVP Ryne Sandberg, and the legendary

Ernie ‘‘Mr. Cub’’ Banks engaged in the most dramatic home-run race

in the history of baseball. He and St. Louis Cardinals slugger Mark

McGwire battled each other shot for shot throughout the season, with

the Cardinal first-baseman finally slamming 70 home runs to Sosa’s

66. Both players shattered Roger Maris’s long-standing single-season

home run record of 61 while helping to revive the popularity of

baseball, whose status had suffered following the 1994 strike.

—Jason McEntee

F

URTHER READING:

Bjarkman, Peter C., editor. Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball

Team Histories. Westport, Connecticut, Meckler, 1991.

The Chicago Cubs Media Guide. Chicago, Chicago National League

Ball Club, 1991.

Golenbock, Peter. Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the

Chicago Cubs. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

‘‘The Official Web Site of the Chicago Cubs.’’ http:www.cubs.com.

May 1999.

Chicago Jazz

Although New Orleans is the acknowledged birthplace of jazz,

Chicago is regarded as the first place outside of the South where jazz

CHICAGO JAZZ ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

494

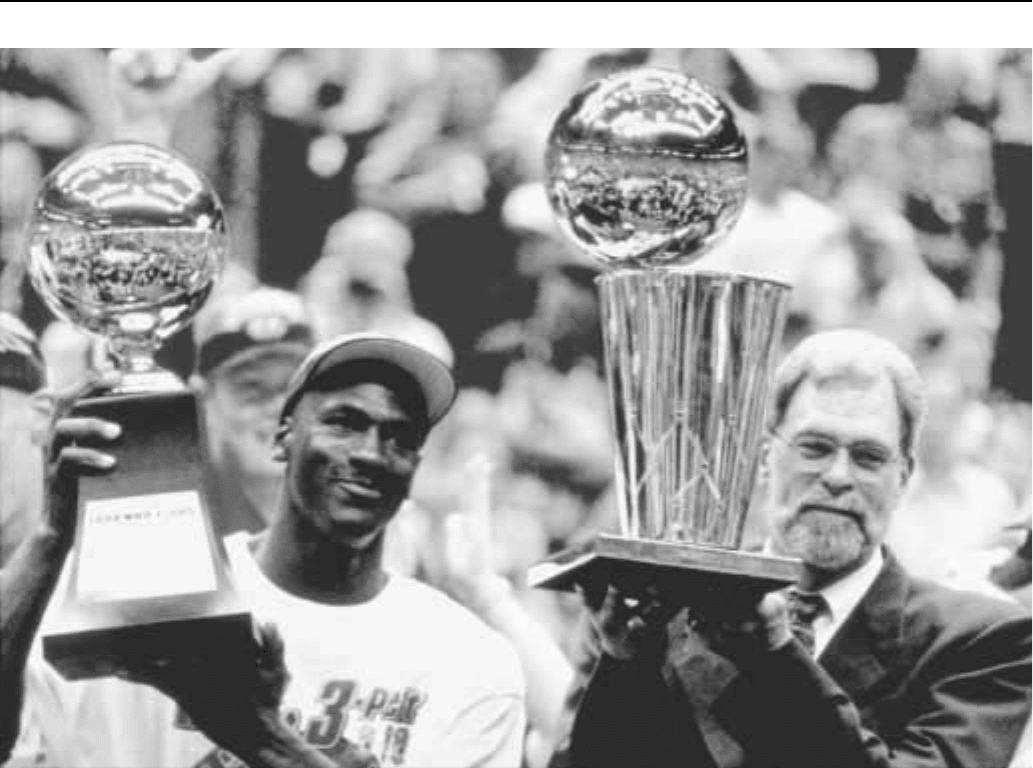

Chicago Bulls’ captain Michael Jordan holding his series MVP trophy and head coach Phil Jackson holding the Bulls’ sixth NBA Championship Trophy.

was heard, and New Orleans-style jazz was first recorded in Chicago.

Popular in the 1920s, ‘‘Chicago Jazz’’ refers to a white style of music,

closely related to New Orleans Jazz, in which soloists were more

prominent than the ensemble. The music is also tighter or less

rhythmically realized than the New Orleans style.

When World War I increased employment opportunities for

African Americans outside the South, Chicago became a center of the

black community. Jazz moved to Chicago to fill the need for familiar

entertainment. From the black neighborhoods, jazz moved into the

white areas of Chicago, where young Chicago kids were fascinated

with the new sounds.

The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, a group of white New

Orleans musicians who were the first band to record jazz, included

Chicago musicians for their famous appearance at the Friar’s Inn.

That appearance and their 1917 jazz recording increased its visibility

and attracted a large following for the new music. The New Orleans

Rhythm Kings, an influence on the great Bix Beiderbecke, followed

in 1922 but were no match for King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, which

Oliver had formed in New Orleans and taken to Chicago in 1918,

where Louis Armstrong joined in 1922. The Creole Jazz Band

recorded the most significant examples of New Orleans-style jazz.

King Oliver’s band brought African-American jazz to Chicago

and soon attracted a following comparable to that of rock stars today.

Armstrong often played at more than one club in a night. Other New

Orleans greats who came to Chicago in the 1920s included Sid-

ney Bechet, both Johnny and Baby Dodds, Jimmy Noone, and

Freddie Keppard.

Banjoist Eddie Condon (1905-1973) is considered the leader of

the Chicago School, carrying on battles against the boppers, whom he

considered to have spoiled jazz. His musicians included cornetist

Jimmy McPartland (1907-1991), Bud Freeman, Frankie Teschemacher,

and Red McKenzie. This was the core of the Austin High Gang, the

core of the Chicago Jazz movement. The first recording of the

Chicago style was on December 10, 1927. But Condon says that they

were just a bunch of guys who happened to be from Chicago. Condon

pioneered multi-racial recordings, getting many of the New Orleans

musicians together with white musicians.

Jimmy McPartland (1907-1991), the other link in the Chicago

Jazz School, was the center of the Austin High Gang. He learned the

solos note for note of the New Orleans Rhythm Kings and then copied

Bix Beiderbecke’s work. He even replaced Bix in the Wolverines.

McPartland carried the message of classic Dixieland cornet around

the world and remained associated with the Chicago Jazz style until

his death.

—Frank A. Salamone

CHICAGO SEVENENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

495

FURTHER READING:

Ian Carr, et al. Jazz: The Rough Guide. London, Rough Guides, 1995.

The Chicago Seven

It was violent clashes between anti-war protesters and police

during the Chicago Democratic Convention of 1968 that created the

Chicago Seven’s place in political and cultural history. The seven

political radicals were indicted for the so-called ‘‘Rap Brown’’ law,

which made it illegal to cross state lines and make speeches with the

intent to ‘‘incite, organize, promote, and encourage’’ riots, conspira-

cy, and the like. There were originally eight defendants: David

Dellinger, a pacifist and chairman of the National Mobilization

against the Vietnam War; Tom Hayden and Rennie Davis, leaders of

the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS); Abbie Hoffman and

Jerry Rubin, leaders of the Youth International Party—or ‘‘Yippies;’’

John Froines and Lee Weiner, protest organizers; and Bobby Seale,

co-founder of the Black Panther Party. The riots and subsequent trial

triggered more massive and violent anti-war demonstrations around

the country. The conflict in Chicago, however, was not simply about

America’s involvement in Vietnam. The conflict was also about the

political system, and to those millions who watched the confronta-

tions between police and demonstrators on television, it marked a

crisis in the nation’s social and cultural order.

The demonstrators, many of whom had been involved with civil

rights battles in the South, saw their protests at the convention as an

opportunity to draw media attention to their cause. Following the

murders of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, many

protesters were anxious to become more confrontational and militant

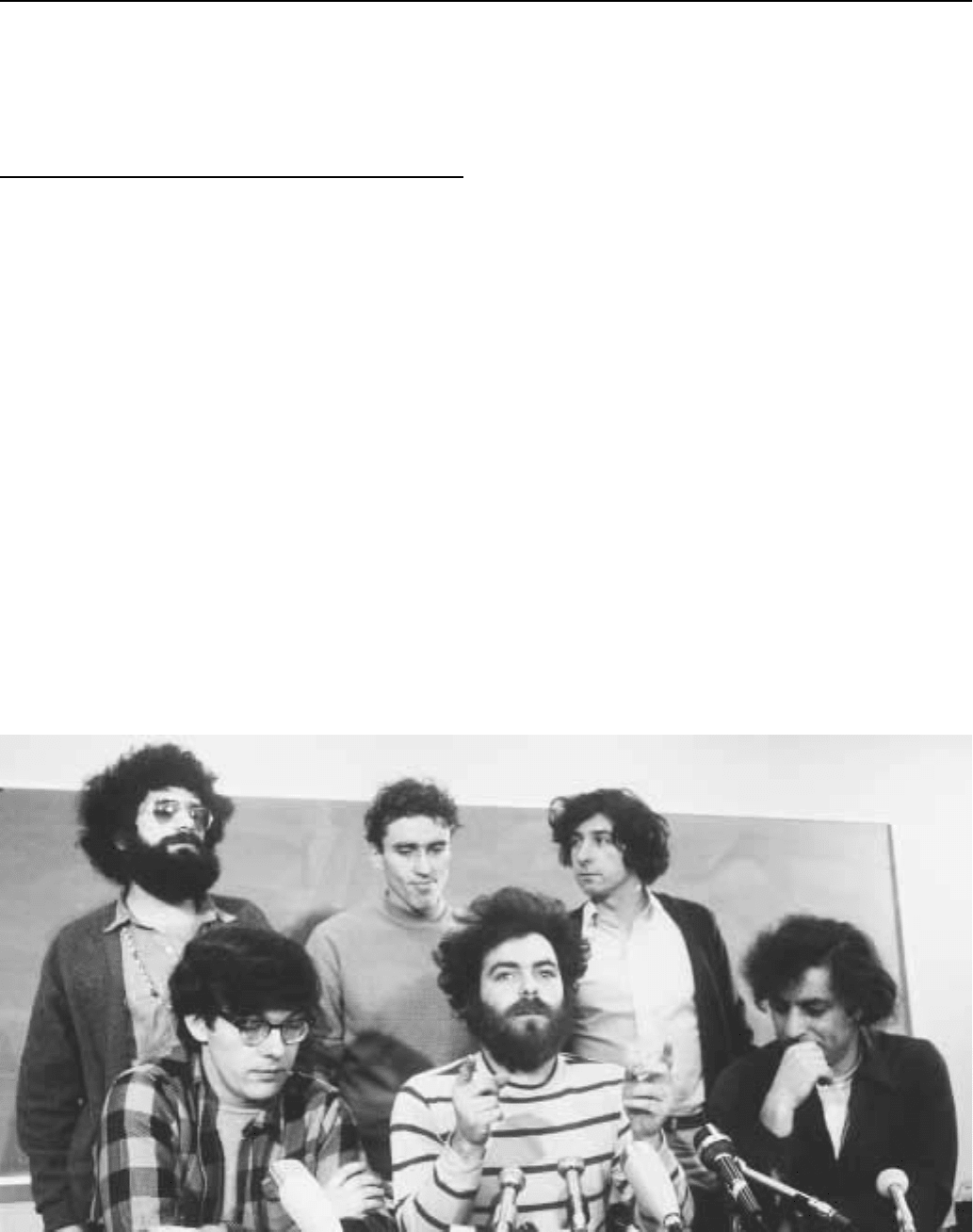

Members of the Chicago Seven: (back row from left) Lee Weiner, Bob Lamb, Tom Hayden, (front row from left) Rennie Davis, Jerry Rubin, and Abbie

Hoffman.

with political and police forces. The Yippies, led by Hoffman and

Rubin, looked to harness the energy of America’s rebellious youth

culture, with its rock music and drugs, to bring about social and

political change. The Yippies were formed solely for the purpose of

confronting those involved with the Democratic Convention. They

believed that the mass media and music could lead young people to

resist injustices in the political system. Hoffman and Rubin, the most

flamboyant and disruptive participants in the court trial—after Seale

was removed—did not believe that the ‘‘New Left’’ would be able to

bring about change through rational discourse with existing powers.

Hence, they led a movement which relied upon guerrilla theater, rock

music, drug experiences, and the mass media to broadcast their

agenda of social revolution to a generation of alienated young people

brought up on television and advertising. Influencing policies or

candidates was not the aim behind the radicalism of the Chicago

Seven. Rather, they worked to reveal the ugliness of a country full of

poverty, racism, violence, and war through a confrontation with the

armed State. The fact that their actions took place in America’s

second largest city, during a nationally televised political convention,

only intensified their message of resistance and rejection.

Chicago mayor Richard Daley and his police force characterized

the demonstrations as attacks upon their city and the law. They

viewed the Chicago Seven and the national media as outside agitators

who trampled on their turf. The Walker Report, however, which was

later commissioned to investigate the events of the convention week,

concluded that the police were responsible for much of the violence

during the confrontations. Perhaps the most memorable statement

about the events surrounding the rebellion were uttered by Mayor

Daley at a press conference during the convention: ‘‘The police-

man isn’t there to create disorder. The policeman is there to

preserve disorder.’’

CHILD ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

496

The trial of the eight defendants began in September of 1969 and

lasted for five months. Judge Julius Hoffman inflexibility and obvi-

ous bias against the defendants provoked righteous anger, revolution-

ary posturing, guerrilla theater, and other forms of defiant behavior

from the defendants. Bobby Seale’s defiant manner of conducting his

own defense—his attorney was in California recuperating from

surgery—resulted in his spending three days in court bound and

gagged. Judge Hoffman then declared his case a mistrial and sen-

tenced him to four years in prison for contempt of court. Hence, the

Chicago Eight became the Chicago Seven. William Kunstler and

Leonard Weinglass were the defense attorneys. Judge Hoffman and

prosecutor Thomas Foran constantly clashed with the defendants who

used the court as a setting to continue to express their disdain for the

political and judicial system. In February, all of the defendants were

acquitted of conspiracy but five were found guilty of crossing state

lines to riot. Froines and Weiner were found innocent of teaching and

demonstrating the use of incendiary devices. An appeals court over-

turned the convictions in 1972, citing procedural errors and Judge

Hoffman’s obvious hostility to the defendants.

—Ken Kempcke

F

URTHER READING:

Epstein, Jason. The Great Conspiracy Trial: An Essay on Law,

Liberty, and the Constitution. New York, Vintage Books, 1971.

Farber, David. Chicago ’68. Chicago, University of Chicago

Press, 1988.

Hayden, Tom. Trial. New York, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970.

Schultz, John. The Chicago Conspiracy Trial. New York, Da Ca-

po, 1993.

Child, Julia (1912—)

Julia Child made cooking entertainment. A well-bred, tall,

ebullient woman who came to cooking in the middle of her life, Julia

Child appeared on television for the first time in the early 1960s and

inaugurated a new culinary age in America. Blessed with an ever-

present sense of humor, a magnetic presence in front of the camera,

and the ability to convey information in a thoroughly engaging

manner, Julia Child spirited Americans away from their frozen foods

and TV dinners and back into the kitchen, by showing them that

cooking could be fun.

For someone who would become one of the most recognizable

and influential women in the world, it took Julia Child a long time to

find her true calling. She spent the first 40 years of her life in search of

her passion—cooking—and when she found it, she was unrelenting in

promoting it. But like so many privileged women of her generation,

Julia Child was not brought up to have a career. Born on August 15,

1912 into the conservative affluence of Pasadena, California, Julia

McWilliams was the daughter of an aristocratic, fun-loving mother

and a well-off, community-minded businessman father. Raised in a

close family, who provided for her every need, Julia was a tree-

climbing tomboy who roamed the streets of Pasadena with her passel

of friends. Her childhood was full of mischievous fun, and food

formed only the most basic part of her youth. Her family enjoyed

hearty, traditional fare supplemented by fresh fruits and vegetables

from nearby farms.

Julia Child

By her early teenage years, Julia was head and shoulders taller

than her friends, on her way to becoming a gigantic, rail thin 6 feet 2

inches. Lithe and limber, the athletic teenager enjoyed tennis, skiing,

and other sports, and was the most active girl in her junior high

school. When she graduated from ninth grade, however, her parents

decided it was time for Julia to get a solid education, and so they sent

her to boarding school in Northern California. At the Katherine

Branson School for Girls, Julia quickly became a school leader,

known, as her biographer Noël Riley Fitch has written, for ‘‘her

commanding physical presence, her verbal openness, and her physi-

cal pranks and adventure.’’ As ‘‘head girl,’’ Julia stood out among her

classmates socially, if not intellectually. She was an average student,

whose interests chiefly lay in dramatics and sports and whose greatest

culinary delight was jelly doughnuts. But her education was solid

enough to earn her, as the daughter of an alumna, a place at prestigious

Smith College in Massachusetts.

In her four years at Smith, Julia continued in much the same vein

as in high school. She was noted for her leadership abilities, her sense

of adventure, and, as always, her height. At 6 feet 2 inches, she was

once again the tallest girl in her class. At Smith, she received a solid

education. But, as Julia would later remark, ‘‘Middle-class women

did not have careers. You were to marry and have children and be a

nice mother. You didn’t go out and do anything.’’ And so after

graduation, Julia returned home to Pasadena. After a year, however,

she grew restless and returned to the East Coast, hoping to find a job in

New York City. Sharing an apartment with friends from Smith and

supported mostly by her parents, Julia found a job at Sloane’s, a

CHILDENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

497

prestigious home-furnishing company. She worked for the advertis-

ing manager, learning how to write press releases, work with photog-

raphers, and handle public relations. She loved having something to

do and reveled in the job. Having always been interested in writing,

Julia also began submitting short pieces to magazines such as the

Saturday Review of Literature. Her life now had some larger purpose.

But Julia’s stay in New York would only last a few years.

Unhappy over the breakup of a relationship and worried about her

mother’s health, Julia returned home to Pasadena, where her mother

died two months later. As the oldest child, Julia decided to stay in

California to take care of her father and soon found work writing for a

new fashion magazine and later heading up the advertising depart-

ment for the West Coast branch of Sloane’s. But by the early 1940s,

with America at war, Julia had grown impatient with her leisurely

California life. A staunch Rooseveltian Democrat, Julia wanted to be

a part of the war effort and so applied to the WAVES and the WACS.

But when her height disqualified her from active service, Julia moved

to Washington, D.C., where she began work in the Office of Strategic

Services, the American branch of secret intelligence.

With her gift for leadership, Julia quickly rose in the ranks,

working six days a week, supervising an office of 40 people. She still

dreamed of active service, and when the opportunity arose to serve

overseas, she jumped at the chance. In early 1944, 31-year-old Julia

McWilliams sailed for India. In April, she arrived in Ceylon, where

she went to work at the OSS headquarters for South East Asia.

Although she considered the work drudgery, she loved being in a

foreign country, as well as the urgency of the work at hand. She met

many interesting people, men and women, not the least of whom was

a man ten years older than she, an urbane officer named Paul Child.

Stationed in Ceylon and later in China, Julia and Paul became

good friends long before they fell in love. She was fascinated by his

background—a multilingual artist, he had lived in Paris during the

1920s and was a true man of the world. One of his great passions was

food, and he gradually introduced Julia to the joys of cuisine. In

China, the two friends would eat out at local restaurants every chance

they could. She would later write: ‘‘The Chinese food was wonderful

and we ate out as often as we could. That is when I became interested

in food. There were sophisticated people there who knew a lot about

food . . . I just loved Chinese food.’’

Julia recognized it first—she had fallen in love. It took Paul a

little longer to realize that he was head-over-heels for this tall,

energetic, enthusiastic Californian. In fact, after the war, the two went

their separate ways, only coming together later in California. In their

time apart, Julia had begun perfunctory cooking lessons, hoping to

show off her newfound skills to Paul. By the time they decided to

drive across country together, they knew they would be married. Julia

and Paul Child set up house together in Washington, D.C., awaiting

Paul’s next assignment. When they were sent to Paris, both were ecstatic.

Julia’s first meal upon landing in France was an epiphany. She

later reflected, ‘‘The whole experience was an opening up of the soul

and spirit for me . . . I was hooked, and for life, as it turned out.’’

While settling in Paris, Julia and Paul ate out at every meal, and Julia

was overwhelmed by the many flavors, textures, and sheer scope of

French cuisine. She loved everything about it and wanted to learn

more. In late October 1949, Julia took advantage of the GI Bill and

enrolled at the Cordon Bleu cooking school. It was the first step in a

long journey that would transform both her life and American

culinary culture.

The only woman in her class, Julia threw herself into cooking,

spending every morning and afternoon at the school and coming

home to cook lunch and dinner for Paul. On the side, she supplemen-

ted her schooling with private lessons from well-known French chefs,

and she attended the Cercle des Gourmettes, a club for French women

dedicated to gastronomy. There she met Simone Beck and Louisette

Bertholle. The three soon became fast friends and, after Julia graduat-

ed from Cordon Bleu, they decided to form their own cooking school

geared at teaching Americans in Paris. L’Ecole des Trois Gourmands

was formed in 1952 and was an instant success. Out of this triumvirate

came the idea for a cookbook that would introduce Americans to

French cuisine.

With the help of an American friend, the idea was sold to

Houghton Mifflin. The most popular American cookbooks, The Joy

of Cooking and Fanny Farmer, were old classics geared toward

traditional American fare. Julia envisioned a cookbook that would

capture the American feel of The Joy of Cooking in teaching Ameri-

cans about French cuisine. For the next ten years, Julia and her

companions labored tirelessly over their cookbook. Even when Paul

and Julia were transferred, first to Marseille then to Bonn, Washing-

ton, and Oslo, the Trois Gourmands remained hard at work. Julia was

meticulous and scientific, testing and re-testing each recipe, compar-

ing French food products to American, keeping up with American

food trends, and polishing her writing and presentation style. Less

than a year from the finish, however, Houghton Mifflin suddenly

pulled out and it seemed that the project would never come to fruition.

Then Knopf stepped in and in 1961, shortly after Julia and Paul

returned to the United States for good, Mastering the Art of French

Cooking was released. An immediate success, the cookbook, with its

superb quality, clear and precise recipes, and unique pedagogical

approach to cooking, became the standard against which all other

cookbooks would come to be judged. At 49 years old, Julia Child was

hailed as a great new American culinary voice. In a country where

most people’s meals consisted of canned items, frozen foods, and TV

dinners, the food community hailed her classical training. As Karen

Lehrman wrote in ‘‘What Julia Started,’’ ‘‘In the 1950s, America was

a meat-and-potatoes kind of country. Women did all of the cooking

and got their recipes from ladies’ magazine articles with titles like

‘The 10-Minute Meal and How to Make It.’ Meatloaf, liver and

onions, corned beef hash—all were considered hearty and therefore

healthy and therefore delicious. For many women, preparing meals

was not a joy but a requirement.’’ Julia Child would change all that.

Julia and Paul settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a decision

that would ultimately make Julia Child a household name. As the

home of many of the country’s finest institutions of higher learning,

Cambridge boasted the best-funded educational television station,

WGBH. Early in 1962, WGBH approached Julia about putting

together a cooking show. Filmed in black and white in rudimentary

surroundings, the show was a success from the very start. Julia Child

was a natural for television. Although each show was carefully

planned and the meals meticulously prepared, on-air Julia’s easy

going manner, sense of humor, and joie de vivre shone through,

making her an instant hit.

Within a year, Julia Child’s The French Chef was carried on

public television stations around the country and Julia Child was a

household name with a huge following. As Karen Lehrman describes,

‘‘Julia may or may not have been a natural cook, but she certainly was

a natural teacher and comedian. Part of the entertainment came from

her voice alone, which can start a sentence on a bass note and end of

falsetto, and elongate in different keys several seemingly random

words in between. But she also had an exceptional presence, a keen

CHILD STARS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

498

sense of timing and drama, and a superb instinct for what’s funny.

Most important, she completely lacked pretension: She played her-

self. She made noises (errgh, oomph, pong), called things weird or

silly, clashed pot lids like cymbals, knocked things over, and in

general made quite a mess. ‘When, at the end of the program, she at

last brings the finished dish to the table,’ Lewis Lapham wrote in

1964, ‘she does so with an air of delighted surprise, pleased to

announce that once again the forces of art and reason have triumphed

over primeval chaos.’’’

For the next 30 years, Julia Child would appear on television, but

because she viewed herself as a teacher, only on public television.

Supported by Paul every step of the way, Julia would transform

cooking from a housewife’s drudgery to a joyous event for both men

and women. In doing so, she changed the culinary face of America.

She became a universally recognizable and much loved pop culture

icon. Her shows became the object of kindhearted spoof and satire—

the best of which was done by Dan Ackroyd on Saturday Night Live—

and her image appeared in cartoons. But mostly it was Julia herself

who continued to attract devoted viewers of both sexes, all ages, and

many classes. As Noël Riley Fitch wrote, ‘‘The great American fear

of being outré and gauche was diminished by this patrician lady who

was not afraid of mistakes and did not talk down to her audience.’’

Julia-isms were repeated with glee around the country, such as the

time she flipped an omelet all over the stove and said, ‘‘Well, that

didn’t go very well,’’ and then proceeded to scrape up the eggs and

put them back in the pan, remarking, ‘‘But you can always pick it up if

you’re alone. Who’s going to see?’’ Her ability to improvise and to

have fun in the kitchen made her someone with whom the average

American could identify. As Julia herself said, ‘‘People look at me

and say, ‘Well, if she can do it, I can do it.’’’

As America got turned on to food, be it quiche in the 1970s,

nouvelle cuisine in the 1980s, or organic food in the 1990s, Julia

stayed on top of every trend, producing many more exceptional

cookbooks. The Grande Dame of American cuisine, Julia Child

remains the last word on food in America. Founder of the American

Institute of Wine and Food, Julia Child continues to bring together

American chefs and vintners in an effort to promote continued

awareness of culinary issues and ideas both within the profession—

which, thanks to Julia, is now among the fastest growing in Ameri-

ca—and among the public. Popular women chefs, such as Too Hot

Tamales, Susan Feniger and Mary Sue Miliken, abound on television,

thanks to Julia who, though she did not think of herself as a feminist,

certainly liberated many women through her independence and

passionate commitment to her career. Karen Lehrman has written,

‘‘Julia Child made America mad for food and changed its notions of

class and gender.’’ A uniquely American icon, Julia Child not only

transformed the culinary landscape of this country, but she became a

role model for men and women of all ages and classes.

—Victoria Price

F

URTHER READING:

Child, Julia. Mastering the Art of French Cooking. New York, Alfred

A. Knopf, 1961.

Fitch, Noël Riley. Appetite for Life: The Biography of Julia Child.

New York, Doubleday, 1997.

Lehrman, Karen. ‘‘What Julia Started.’’ U.S. News and World

Report. Vol. 123, No. 11, September 22, 1997, 56-65.

Reardon, Joan. M.F.K Fisher, Julia Child, and Alice Waters: Cele-

brating the Pleasures of the Table. New York, Harmony

Books, 1994.

Villas, James. ‘‘The Queen of Cuisine.’’ Town and Country. Vol.

148, No. 5175, December 1994, 188-193.

Child Stars

In Hollywood, it has been said that beauty is more important than

talent, but youth is most important of all. The image of America

conveyed by the motion picture industry is one of beautiful, young

people in the prime of life. The most youthful of all are the children—

fresh-faced innocents in the bloom of youth transformed into Holly-

wood stars who represent the dreams of a nation. Certainly this was

the case during the Depression, when child stars such as Shirley

Temple, Freddie Bartholomew, and Deanna Durbin were the motion

picture industry’s top box office draws, inspiring a global mania for

child actors. In what has come to be known as the Child Star Era, these

juvenile audience favorites often single-handedly supported their

studios, becoming more famous than their adult counterparts. When

the Golden Age of Hollywood came to an end after World War II, so

did the Child Star Era. But the appeal of child stars remains strong in

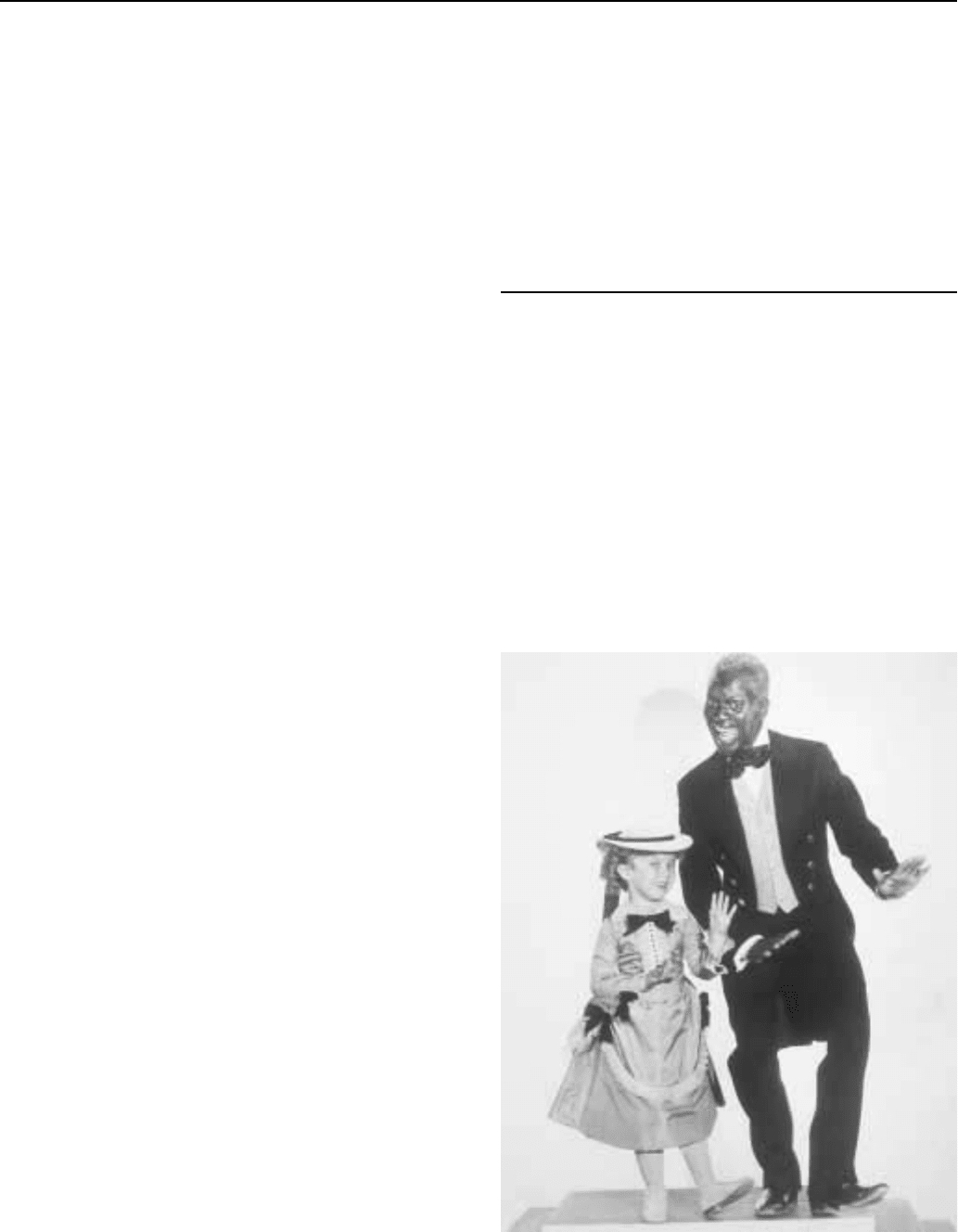

Shirley Temple and Bill ‘‘Bojangles’’ Robinson.