Pendergast T., Pendergast S. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Volume 1: A-D

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHURCH SOCIALSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

509

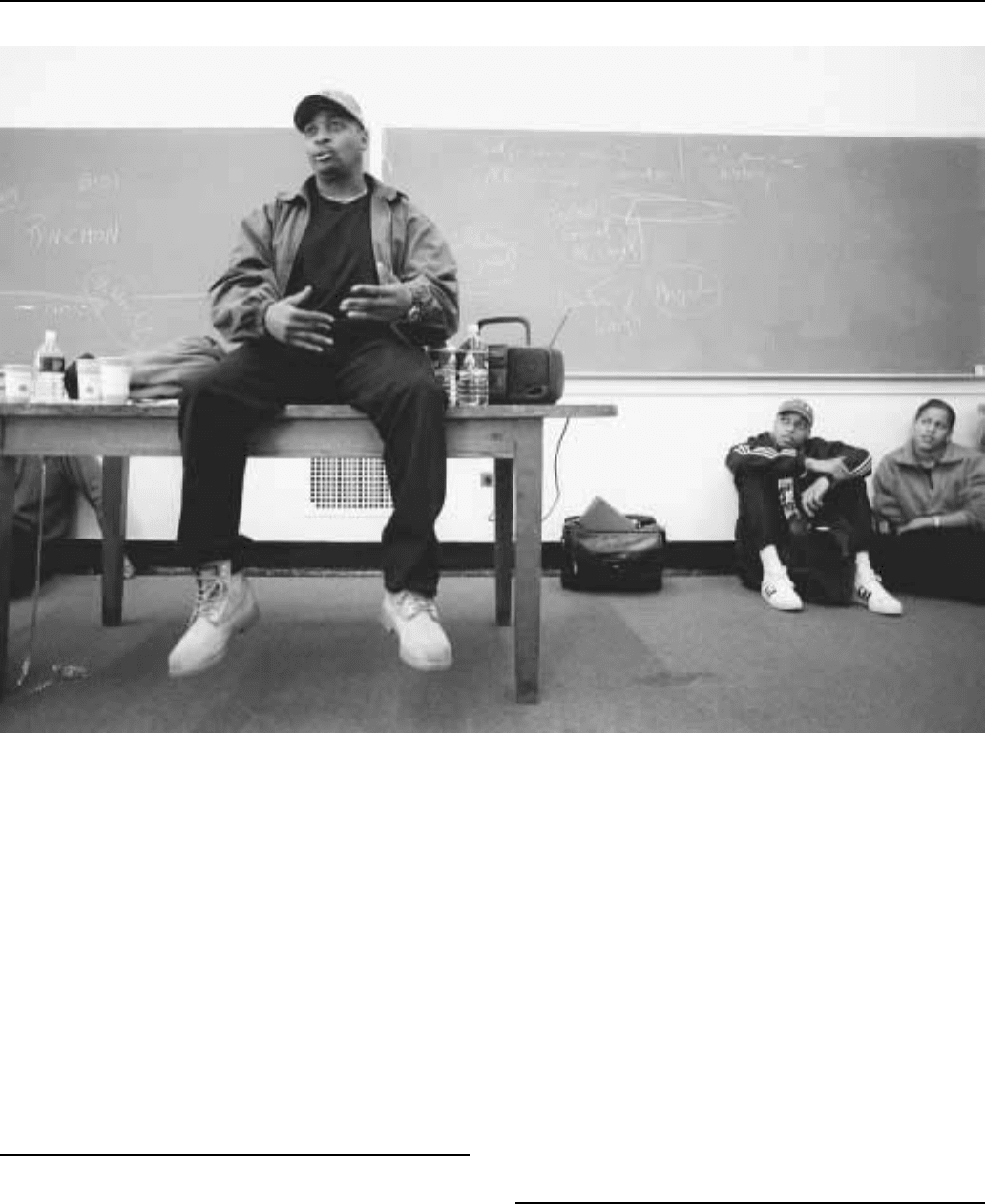

Chuck D speaks to Columbia University students in 1998.

never changed Public Enemy’s course, and in 1998 the group released

a highly political and sonically dense soundtrack album for Spike

Lee’s film He Got Game.

—Kembrew McLeod

F

URTHER READING:

Chuck D. Fight the power: Rap, Race, and Reality. New York,

Delacorte Press, 1997.

Fernando, S.H., Jr. The New Beats: Exploring the Music, Culture, and

Attitudes of Hip-Hop. New York, Anchor Books, 1994.

Chun King

Chun King was one of the earliest brands of mass-marketed

Chinese food in the United States, offering convenient ‘‘exotic’’

dinners in a can. Beginning with chicken chow mein in 1947, Chun

King later expanded its menu to include eggrolls and chop suey.

Although chow mein was Chinese-American, the maker of Chun

King foods was not. The founder and president of Chun King was

Jeno F. Paulucci, the son of Italian immigrants. Paulucci began his

career in the food industry working in a grocery, and later sold fruits

and vegetables from a car. Paulucci saw an opportunity in Chinese

food and began canning and selling chow mein. The business grew

into a multi-million dollar industry, and in the late 1960s Paulucci

sold the company for $63 million. In the 1990s ConAgra and Hunt-

Wesson marketed Chun King chow mein, beansprouts, eggrolls,

and sauces.

—Midori Takagi

F

URTHER READING:

Cao, Lan, and Himilce Novas. Everything You Need to Know About

Asian-American History. New York, Penguin, 1996.

Church Socials

A gathering of church members for celebratory, social, or

charitable purposes, church socials in America have remained popu-

lar—while becoming more varied and elaborate—throughout the past

two centuries.

CIGARETTES ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

510

Church socials in America are rooted in ancient Jewish festivals.

Jews traveled to Jerusalem to participate in public worship activities

that commemorated important events or celebrated the harvest.

Because the tribes of Israel were separated geographically, these

festivals served the additional purpose of providing the cement

needed for national unity. Old prejudices and misunderstandings

were often swept away by these major events.

With the birth of the church, Christians shared common meals

designed to enhance relationships within the church. The Bible says

in Acts 2:46, ‘‘. . . They broke bread in their homes and ate together

with glad and sincere hearts.’’ Eventually, the Agape meal or ‘‘love

feast’’ became popular. It provided fellowship and opportunity to

help the poor and widows. It was later practiced in the Moravian and

Methodist churches.

Socials enhance church celebrations of Easter, Christmas, and

other holidays. Because the Bible says that Jesus’ resurrection took

place at dawn, Christians often meet together early on Easter morning

for a ‘‘Sunrise Service’’ followed by a breakfast. An Easter egg hunt

is often included, though some frown on this as a secular activity.

Churches plan various Christmas socials such as caroling, exchang-

ing gifts, and serving special dinners. Opinions vary on whether to

include Christmas trees and Santa Claus. Some avoid them as secular

symbols while others include them because they believe these tradi-

tions have Christian origins. As American society embraced other

holidays such as Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, Valentine’s Day, the

Fourth of July, and Thanksgiving, churches discovered fresh opportu-

nities for social activities including mother-daughter, father-son,

sweetheart, and Thanksgiving banquets. Churches in communities

sometimes join together for patriotic celebrations on the Fourth of July.

Socials get people together in informal settings so that they will

become better acquainted and work together more effectively in the

church. Congregations in rural and small town America enjoy popular

social activities involving food and games. Ham, bean, and cornbread

dinners, chili suppers, ‘‘pot luck’’ meals, homemade ice cream

socials, wiener roasts, picnics, hayrides, softball games, watermelon

eating contests, and all-day singing events are only a few examples. In

fact, for these rural congregations, church socials have often been the

only source of social activities in a community. In some cases, homes

were so far apart, separated by acres of farmland, that churches were

the only places where people could go to meet others. Many people

went to church socials on dates, and was a place where they often met

their future spouses. Some churches included dancing and alcoholic

beverages, but others believed those activities were inappropriate for

churches to sponsor. Churches in both rural and urban areas often

have family nights designed especially for busy families. A family

comes to church on a weeknight and shares a meal with other families

before Bible study or other small group activities.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, churches began

planning more elaborate socials. Churches in or near urban areas

attend professional sports. This is so widespread that most profession-

al stadiums offer discount rates for church groups. Churches join

together to sponsor basketball, softball, and volleyball leagues. While

most churches rent community facilities, some have built their own

gymnasiums and recreation halls. Other social activities involve trips

to major recreation areas such as amusement parks. Swimming,

picnicking, camping, and enjoying amusement rides are a few of the

activities that round out these outings that last whole days or even

entire weekends. Some church groups in recent years have provided

cruises, trips to major recreational sites such as Branson, Missouri,

and even vacations to other countries. While more elaborate, a cruise

for Christian singles, for example, serves the same purpose as the

traditional hayride and wiener roast.

As the early church was concerned for widows, orphans, the sick

and the poor, and gave generously to meet those needs, so modern

church socials may be founded on the desire to assist the needy or

fund church programs. As a result, activities such as homemade-ice-

cream socials, sausage-and-pancake suppers, and craft bazaars are

opened to the public. Some Catholic churches sponsor festivals that

take on the flavor of county fairs. Amusement rides, carnival games,

and food booths draw thousands of people. Money is used to pay for

parochial schools or some other church project. (Some Catholic and

many non-Catholic churches believe that these activities are too

secular. Card playing, gambling, and the drinking of alcoholic bever-

ages included in some of these events have also been quite controver-

sial.) Some churches use their profits to support Christian retirement

homes and hospitals. Some believe churches should not sell food or

merchandise, but they give free meals away to the poor in the

community. Other groups such as the Amish still have barn raising

and quilting socials to help others in their community.

—James H. Lloyd

F

URTHER READING:

Clemens, Frances, Robert Tully, and Edward Crill. Recreation in the

Local Church. Elgin, Ill., Brethren Press, 1961.

Conner, Ray. A Guide to Church Recreation. Nashville, Convention

Press, 1977.

Roadcup, David, ed. Methods for Youth Ministry: Leadership Devel-

opment, Camp, VBS, Bible Study, Small Groups, Discipline, Fine

Arts, Film, Mission Trips, Recreation, Retreats. Cincinnati, Stand-

ard Publishing, 1986.

Smith, Frank Hart. Social Recreation and the Church. Nashville,

Convention Press, 1983.

Cigarettes

It is highly unlikely that in 1881, when James A. Bonsack

invented a cigarette-making machine, that he or anybody else could

have predicted the mélange of future symbolism contained in each

conveniently packaged stick of tobacco. The cigarette has come to

stand for more than just the unhealthy habit of millions in American

popular culture. It represents politics, money, image, sex, and freedom.

The tobacco plant held residence in the New World long before

Columbus even set sail. American Indians offered Columbus dried

tobacco leaves as a gift and, it is rumored, he threw them away

because of the fowl smell. Later on, however, sailors brought tobacco

back to Europe where it gained a reputation as a medical cure-all.

Tobacco was believed to be so valuable that during the 1600s, it was

frequently used as money. In 1619, Jamestown colonists paid for their

future wives’ passage from England with 120 pounds of tobacco. In

1621, the price went up to 150 pounds per mate. Tobacco later helped

finance the American Revolution, also known as ‘‘The Tobacco

War,’’ by serving as collateral for loans from France.

Tobacco consumption took many forms before reaching the

cigarette of the modern day. Spanish colonists in the New World

smoked tobacco as a cigarito: shredded cigar remnants rolled in plant

husks, then later in crude paper. In France, the cigarito form was also

CIGARETTESENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

511

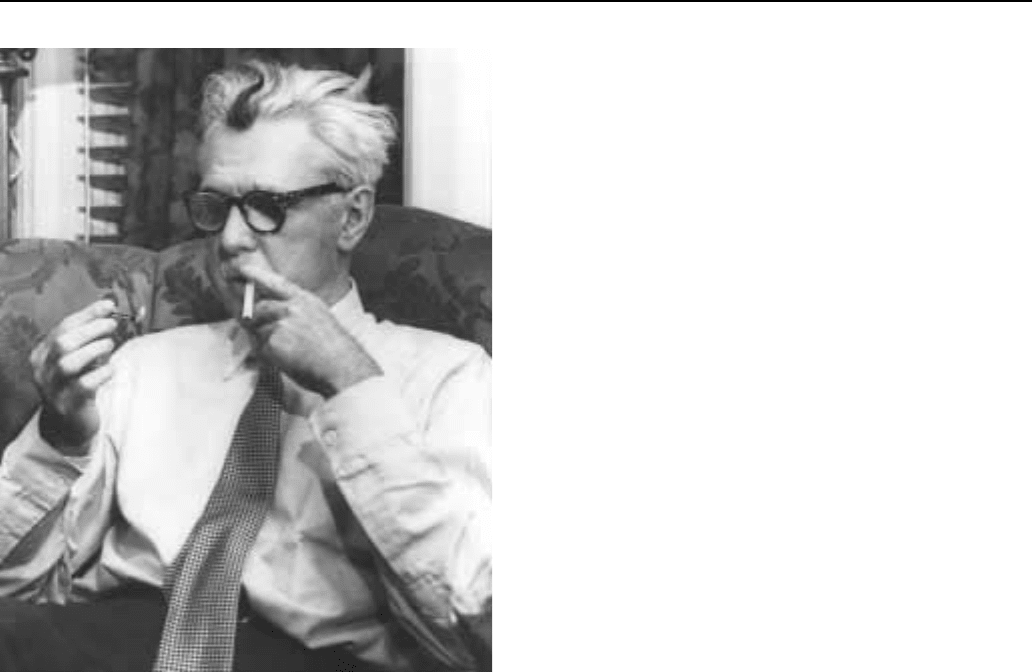

James Thurber enjoying a cigarette.

popular, especially during the French Revolution. As aristocrats

commonly consumed the snuff version of tobacco, the masses chose

an opposing form. A moderate improvement to the Spanish cigarito,

the French cigarette was rolled in rice straw. In 1832, an Egyptian

artilleryman in the Turkish/Egyptian War created the paperbound

version of today whose popularity spread to the British through

veterans of the Crimean War. In England, a tobacconist named Philip

Morris greatly improved the quality of the Turkish cigarette but

still maintained only a cottage industry, despite the cigarette’s

growing popularity.

By the 1900s cigarettes rose to the highest selling form of

tobacco on the market. Mass urbanization picked up the pace of daily

life and popularized factory-made products such as soap, canned

goods, gum, and the cigarette. James A. Bonsack’s newly invented

cigarette machine could turn out approximately 200 cigarettes per

minute, output equal to that of forty or fifty workers. Cigarettes were

now a more convenient form of tobacco consumption—cleaner than

snuff or chew, more portable than cigars or pipes—and also were

increasingly more available. England’s Philip Morris set up shop in

America as did several other tobacco manufacturers: R.J. Reynolds

(1875), J.E. Liggett (1849), Duke (1881, later, the American Tobacco

Company), and the oldest tobacco company in the United States, P.

Lorillard (1760). The cigarette quickly became enmeshed in Ameri-

can popular culture. In 1913, R.J. Reynolds launched its Camel brand

whose instant appeal, notes Richard Kluger in Ashes to Ashes, helped

inspire this famous poem from a Penn State publication: ‘‘Tobacco is

a dirty weed. I like it. / It satisfies no moral need. I like it. / It makes

you thin, it makes you lean / It takes the hair right off your bean / It’s

the worst darn stuff I’ve ever seen. / I like it.’’ Since their introduc-

tion, cigarettes have maintained a status as one of the best-selling

consumer products in the country. In 1990, 4.4 billion cigarettes were

sold in America. That same year, several states restricted their sale.

The greatest propagator of what King James I of England

referred to as ‘‘the stinking weed,’’ has been war: the American

Revolution, the French Revolution, the Mexican and Crimean Wars,

the U.S. Civil War, and the greatest boost to U.S. cigarette consump-

tion—World War I. During the first World War, cigarettes were

included in soldiers’ rations and as Kluger suggests, ‘‘quickly became

the universal emblem of the camaraderie of mortal combat, that

consummate male activity.’’ Providing the troops with their daily

intake of cigarettes, a very convenient method of consumption during

combat, was viewed as morale enhancing if not downright patriotic.

Regardless of intention, the tobacco manufacturers ensured them-

selves of a future market for their product.

At the same time, women became more involved in public life,

earning the right to vote in 1920, and entering the work force during

the absence of the fighting men. Eager to display their new sense of

worth and fortitude, women smoked cigarettes, some even publicly.

The tobacco industry responded with brands and advertisements

aimed especially at women. While war may have brought the ciga-

rette to America, marketing has kept it here. Since the introduction of

the cigarette to America, the tobacco industry has spent untold

billions of dollars on insuring its complete assimilation into U.S.

popular culture. Despite the 1971 ban of radio and television adver-

tisements for cigarettes, the industry has successfully inducted char-

acters such as Old Joe Camel, The Marlboro Man, and the Kool

Penguin into the popular iconography. A 1991 study published by the

Journal of the American Medical Association revealed that 91 percent

of six year olds could identify Joe Camel as the character representing

Camel cigarettes and that Joe Camel is recognized by preschoolers as

often as Mickey Mouse. Aside from advertising, cigarettes have been

marketed, most notably to the youth market, through a myriad of other

promotional activities from industry-sponsored sporting and enter-

tainment events to product placement in movies. In 1993 alone, the

tobacco industry spent $6 billion keeping their cigarettes fresh in the

minds of Americans.

While Hollywood has inadvertently, and sometimes quite inten-

tionally, made the cigarette a symbol of glamour and sexuality—the

smoke gingerly billowing as an afterglow of, or substitute for, the act

itself—anti-tobacco activists have equally pursued an agenda of

disclosure, regulation, and often, prohibition. A war has been waged

on the cigarette in America and everyone, smoker or not, was engaged

by the end of the 1990s. The health hazards of smoking have been

debated since at least the 1600s, but litigation in the twentieth century

revealed what the tobacco industry had known but denied for years:

that nicotine, the active substance in cigarettes, is an addictive drug,

and that cigarette smoking is the cause of numerous diseases and

conditions which claim the lives of nearly half a million Americans

each year. The cigarette has thus become for many an emblem of

deception and death for the sake of profit, or even, with the discovery

of second-hand smoke as a carcinogen, a catalyst for social review.

For others, it remains a symbol of money and power and politics or the

Constitutional First Amendment invoked by so many smokers in their

time of need. The cigarette is indeed a dynamic symbol in American

society—habit, hazard, inalienable right.

—Nadine-Rae Leavell

CIRCUS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

512

FURTHER READING:

Glantz, Stanton A., and John Slade, Lisa A. Bero, Peter Hanauer,

Deborah E. Barnes. The Cigarette Papers. Berkeley, University of

California Press, 1996.

Kluger, Richard. Ashes to Ashes: America’s Hundred-Year Cigarette

War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip

Morris. New York, Vintage Books, 1996.

McGowen, Richard. Business, Politics, and Cigarettes: Multiple

Levels, Multiple Agendas. San Rafael, California, Quantum

Books, 1995.

Smith, Jane Webb. Smoke Signals: Cigarettes, Advertising, and the

American Way of Life: An Exhibition at the Valentine Museum,

Richmond, Virginia, April 5-October 9, 1990. Chapel Hill, North

Carolina Press, 1990.

Circus

Long before the advent of film, television, or the Internet, the

circus delivered the world to people’s doorsteps across America.

Arriving in the United States shortly after the birth of the American

republic, the growth of the circus chronicled the expansion of the new

nation, from an agrarian backwater to an industrial and overseas

empire. The number of circuses in America peaked at the turn of the

twentieth century, but the circus has cast a long shadow on twentieth

century American popular culture. The circus served as subject matter

for other popular forms like motion pictures and television, and its

celebration of American military might and racial hierarchy percolat-

ed into these new forms. From its zenith around 1900, to its decline

and subsequent rebirth during the late twentieth century, the circus

has been inextricably tied to larger social issues in American culture

concerning race, physical disability, and animal rights.

In 1793, English horseman John Bill Ricketts established the

first circus in the United States. He brought together a host of familiar

European circus elements into a circular arena in Philadelphia:

acrobats, clowns, jugglers, trick riders, rope walkers, and horses. By

the turn of the twentieth century, the circus had become a huge, tented

amusement that traveled across the country by railroad. In an age of

monopoly capitalism, American circuses merged together to form

giant shows; for example, the Ringling Brothers circus bought

Barnum and Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth in 1907. The biggest

shows employed over 1,000 people and animals from around the

world. These circuses contained a free morning parade, a menagerie

and a sideshow. Their canvas big tops could seat 10,000 spectators

and treated audiences to three rings and two stages of constant

entertainment. Contemporary critics claimed that the circus was ‘‘too

big to see all at once.’’ In the early 1900s, nearly 100 circuses, the

biggest number in American history, rambled across the country.

In 1900, ‘‘circus day’’ was a community celebration. Before

dawn, hundreds of spectators from throughout a county gathered to

watch the circus train rumble into town. The early morning crowd

witnessed scores of disciplined muscular men, horses, and elephants

transform an empty field into a temporary tented city. In mid-

morning, thousands more lined the streets to experience, up close, the

circus parade of marching bands, calliopes, gilded wagons, exotic

animals, and people winding noisily through the center of town. In the

United States, the circus reached its apex during the rise of American

expansion overseas. Circus proprietors successfully marketed their

exotic performances (even those featuring seminude women) as

‘‘respectable’’ and ‘‘educational,’’ because they showcased people

and animals from countries where the United States was consolidat-

ing its political and economic authority. With its displays of exotic

animals, pageants of racial hierarchy (from least to most ‘‘evolved’’),

and dramatizations of American combat overseas, the circus gave its

isolated, small-town audiences an immediate look at faraway cul-

tures. This vision of the world celebrated American military might

and white racial supremacy. The tightly-knit community of circus

employees, however, also provided a safe haven for people ostracized

from society on the basis of race, gender, or physical disability.

In the early twentieth century, the circus overlapped consider-

ably with other popular amusements. Many circus performers worked

in vaudeville or at amusement parks during the winter once the circus

finished its show season. Vaudeville companies also incorporated

circus acts such as juggling, wire-walking, and animal stunts into their

programs. In addition, the Wild West Show was closely tied to the

circus. Many circuses contained Wild West acts, and several Wild

West Shows had circus sideshows. Both also shared the same

investors. Circuses occasionally borrowed their subject matter from

other contemporary amusements. At the dawning of the American

empire, international expositions like the Columbia Exposition in

Chicago (1893) profitably displayed ethnological villages; thus,

circuses were quick to hire ‘‘strange and savage tribes’’ for sprawling

new ethnological congresses of their own. The new film industry also

used circus subjects. Thomas Edison’s Manufacturing Company

produced many circus motion pictures of human acrobatics, trick

elephants, and dancing horses, among others. Circuses such as the

Ringling Brothers Circus featured early film as part of their novel

displays. During the early twentieth century, the circus remained a

popular film subject in movies like Charlie Chaplin’s Circus (1928)

and Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932). Several film stars, such as Burt

Lancaster, began their show business careers with the circus. Cecil B.

DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth won an Oscar for Best Picture

in 1952. These popular forms capitalized on the circus’ celebration of

bodily feats and exotic racial differences.

The American circus began to scale back its sprawling features

in the 1920s, owing to the rise of the automobile and the movies. Most

circuses stopped holding a parade because streets became too con-

gested with cars. As motion pictures became increasingly sophisticat-

ed—and thus a more realistic mirror of the world than the circus—

circuses also stopped producing enormous spectacles of contempo-

rary foreign relations. Yet, despite its diminishing physical presence,

the circus was still popular. On September 13, 1924, 16,702 people,

the largest tented audience in American history, gathered at Concordia,

Kansas, for the Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey circus. In the

milieu of the rising movie star culture of the 1920s, the circus had its

share of ‘‘stars,’’ from bareback rider May Wirth to aerialist Lillian

Leitzel and her dashing trapeze artist husband, Alfredo Codona. Like

their movie star counterparts in the burgeoning consumer culture,

circus stars began to advertise a wealth of products in the 1920s—

from soap to sheet music. Leitzel became so famous that newspapers

around the world mourned her death in 1931, after she fell when

a piece of faulty equipment snapped during a performance in

Copenhagen, Denmark.

During the Great Depression, the colorful traveling circus pro-

vided a respite from bleak times. When nearly a quarter of the United

CISNEROSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

513

States workforce was periodically unemployed, clown Emmett Kelly

became a national star as ‘‘Willie,’’ a tramp character dressed in rags,

a disheveled wig, hat, and smudged face, who pined for lost love and

better circumstances. The circus continued to profit during World

War II, when railroad shows traveled under the auspices of the Office

of the Defense Transportation. Circuses exhorted Americans to

support the war effort. Yet Ringling Brothers and Barnum and

Bailey’s ‘‘Greatest Show On Earth’’ nearly disintegrated after 168

audience members died in a big top fire (sparked by a spectator who

dropped a lit cigarette) during a performance in Hartford, Connecti-

cut, on July 6, 1944.

By the early 1950s, circus audience numbers were in decline, in

part because the circus no longer had a monopoly on novelty or

current events. Television, like movies and radio, provided audiences

with compelling and immediate images that displaced the circus as an

important source of information about the world. Yet, as a way to link

itself to familiar, well-established popular forms, early television

often featured live circus and vaudeville acts; circus performers were

also featured on Howdy Doody as well as game shows like What’s My

Line? Ultimately, however, television offered Americans complete

entertainment in the privacy of the home—which dovetailed nicely

with the sheltered, domestic ethos of suburban America during the

early Cold War. In this milieu, public amusements like movies and

the circus attracted fewer customers. In 1956, just 13 circuses existed

in America. As audiences shrank, showmen scaled back even further

on their labor-intensive operations. Moreover, the rise of a unionized

workforce (during the industrial union movement during the 1930s)

meant that circus owners could no longer depend on a vast, cheap

labor pool. Thus, John Ringling North cut his workforce drastically in

1956 when he abandoned the canvas tent for indoor arenas and

stadiums. Circus employees and fans alike mourned the ‘‘death’’ of

the familiar tented circus—a fixture of the circus business since 1825.

American social movements also transformed the circus. Circus

performances of racial difference became increasingly controversial

during the 1950s. Civil rights leaders had long objected to racist

performances in American popular entertainment, but in the context

of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union,

officials in the United States also protested because they feared that

racist performances would legitimize Soviet claims that American

racism was a product of American capitalism. Consequently, officials

no longer aided circus agents’ efforts to hire foreign performers slated

to work as ‘‘missing links,’’ ‘‘savages,’’ or ‘‘vanishing tribes,’’ and

performances of ‘‘exotic’’ racial difference, particularly at the side-

show, slowly disappeared from the 1950s onward. In addition,

disabled rights activists effectively shut down the circus sideshow and

its spectacles of human abnormality by the early 1980s.

Lastly, the spread of the animal rights movement in the 1970s

transformed the circus. Fearful of picketers and ensuing bad publicity,

several circuses in the 1990s arrive silently at each destination and

stop at night to avoid protesters. Cirque du Soleil, an extraordinarily

successful French Canadian circus from Montreal (with a permanent

show in Las Vegas), uses no animals in its performances. Instead,

troupe members wear tight lycra body suits, wigs, and face paint to

imitate animals as they perform incredible aerial acrobatics to the beat

of a slick, synthesized pop musical score and pulsating laser lights.

Yet, arguably, Cirque du Soleil (among others) is actually not a circus

because of its absence of animals: throughout its long history, the

circus has been defined by its interplay of humans and animals in a

circular arena.

Despite the transformation of its content, the American circus

endures at the turn of the twenty first century. Certainly, towns no

longer shut down on ‘‘circus day,’’ yet a growing number of small

one-ring circuses have proliferated across America. Shows like the

Big Apple Circus, Circus Flora, and Ringling Brothers Barnum and

Bailey’s show, ‘‘Barnum’s Kaleidoscope,’’ have successfully recre-

ated the intimate, community atmosphere of the nineteenth century

one-ring circus, without the exploitation of physical and racial

difference that characterized the older shows. Ultimately, in the

1990s, a decade of increasingly distant, fragmented, mass-mediated,

‘‘virtual’’ entertainment, the circus thrives because it represents one

of the few intimate, live (and hence unpredictable) community

experiences left in American popular culture.

—Janet Davis

F

URTHER READING:

Albrecht, Ernest. The New American Circus. Gainesville, University

Press of Florida, 1995.

Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amuse-

ment and Profit. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Cooper, Diana Starr. Night After Night. Washington, D.C., Island

Press, 1994.

Hammarstrom, David Lewis. Big Top Boss: John Ringling North and

the Circus. Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1992.

Speaight, George. A History of the Circus. London, Tantivy Press, 1980.

Taylor, Robert Lewis. Center Ring: The People of the Circus. Garden

City, New York, Doubleday and Co., 1956.

Cisneros, Sandra (1954—)

Born and raised in Chicago, Chicana writer and poet Sandra

Cisneros is best known for The House on Mango Street (1983), a

series of interconnected prose poems. She is one of a handful of

Latina writers to make it big in the American literary scene and the

first Chicana to sign with a large publishing firm. Cisneros graduated

from Loyola University in Chicago and went on to the prestigious

Iowa Writers Workshop at the University of Iowa where she earned

an MFA. Her poetry collections include My Wicked, Wicked Ways

(1987) and Loose Woman (1994). She also has authored a collection

of essays and short stories, Woman Hollering Creek (1991). Her

poems and stories offer a conversational style, chatty and rambling.

Her writing is lean and crisp, peppered with Spanish words.

—Beatriz Badikian

F

URTHER READING:

Doyle, Jacqueline. ‘‘More Room of Her Own: Sandra Cisneros’s The

House on Mango Street.’’ The Journal of the Society for the Study

of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States. Vol. 19, No. 4,

Winter 1995, 5-35.

Kanoza, Theresa. ‘‘Esperanza’s Mango Street: Home for Keeps.’’

Notes on Contemporary Literature. Vol. 25, No. 3, May 1995, 9.

CITIZEN KANE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

514

Citizen Kane

Orson Welles’ film Citizen Kane has been consistently ranked as

one of the best films ever made. A masterpiece of technique and

storytelling, the film helped to change Hollywood film-making and

still exerts considerable influence today. However, at the time of its

premiere in 1941, it was a commercial failure that spelled disaster for

Welles’ Hollywood career.

Citizen Kane tells the story of millionaire press magnate Charles

Foster Kane (played by Welles). The film opens with Kane on his

death bed in his magnificent Florida castle, Xanadu, murmuring the

word ‘‘Rosebud.’’ A newsreel reporter (William Alland) searches for

clues to the meaning of the word and to the meaning of Kane himself.

Interviewing many people intimately connected with Kane, the

reporter learns that the millionaire was not so much a public-minded

statesman as he was a tyrannical, lonely man. The reporter never

learns the secret of Kane’s last word. In the film’s final moments, we

see many of Kane’s possessions being thrown into a blazing furnace.

Among them is his beloved childhood sled, the name ‘‘Rosebud’’

emblazoned across it.

Citizen Kane encountered difficulties early on. Welles fought

constantly with RKO over his budget and against limits on his control

of the production. Furthermore, because the film was based in part on

Orson Welles (center) in a scene from the film Citizen Kane.

the life of publisher William Randolph Hearst, Hearst’s papers

actively campaigned against it, demanding that Citizen Kane be

banned and then later refusing to mention or advertise it altogether.

Although the scheme backfired, generating enormous publicity for

the movie, a frightened RKO released the film only after Welles

threatened the studio with a lawsuit.

Critics reacted positively, but were also puzzled. They enthusi-

astically applauded Citizen Kane’s many technical innovations.

Throughout the film, Welles and his crew employed depth of field (a

method in which action in both the foreground and background

clearly are in focus, and used to great effect by cinematographer

Gregg Toland), inventive editing, sets with ceilings, chiaroscuro

lighting, and multilayered sound. Although sometimes used in for-

eign film, many of these techniques were new to Hollywood. They

have since, however, become standard for the industry.

Critics also were impressed by Citizen Kane’s many virtuoso

sequences: a ‘‘March of Time’’-type newsreel recounting the bare

facts of Kane’s life; the breakfast table scene, where in a few minutes

his first marriage deteriorates to the strains of a waltz and variations

(by noted screen composer Bernard Herrmann, in his first film

assignment); a tracking shot through the roof of a nightclub; and a

faux Franco-Oriental opera. None of these sequences, however, are

showstoppers; each propels the narrative forward.

CITY LIGHTSENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

515

That narrative proved puzzling both to critics and to audiences at

large. Written by Herman J. Mankiewicz and Welles (although there

is considerable controversy over how much Welles contributed), the

narrative employs a series of flashbacks that tell different pieces of

Kane’s life story and reveal the witnesses’ various perceptions of him.

By arranging these pieces out of order, the script opened the door for

later screenwriters to avoid the demands of strict chronology. At the

time, however, this innovation confused most audiences.

While Citizen Kane did well in New York, the film did poor

business in small-town America. The film was a commercial failure,

allowing RKO’s officials to eventually let go of Welles. Thereafter,

he found it increasingly difficult to make movies in Hollywood.

Shunned by the studio system, he was forced to spend much of his

time simply trying to raise money for his various projects.

For a while, Citizen Kane itself seemed to suffer a similar fate.

Although the film was nominated for a host of Oscars, Academy

members took RKO’s side in the studio’s battle with Welles, award-

ing the movie only one Oscar for best original screenplay. The film

lost to How Green Was My Valley for best picture. Citizen Kane soon

sank into obscurity, rarely discussed, except when described as the

beginning of the end of Welles’ film career.

After World War II, RKO, seeking to recoup its losses, released

Citizen Kane in European theaters hungry for American films and

also made it available for American television. Exposed to a new

generation of moviegoers, the film received new critical and popular

acclaim. Riding the wave of Citizen Kane’s new-found popularity,

Welles was able to return to Hollywood, directing Touch of Evil in 1958.

Consistently ranked number one on Sight and Sound’s top ten

films list since the mid-1950s, Citizen Kane continues to attract,

inspire, and entertain new audiences. In 1998, it was voted the best

American film of the twentieth century by the American Film Institute.

—Scott W. Hoffman

F

URTHER READING:

Carringer, Robert L. The Making of Citizen Kane. Berkeley, Universi-

ty of California Press, 1996.

Higham, Charles. The Films of Orson Welles. Berkeley, University of

California Press, 1970.

Kael, Pauline. The Citizen Kane Book. Boston, Little, Brown and

Company, 1971.

McBride, Joseph. Orson Welles. New York, Viking Press, 1972.

Naremore, James. The Magic World of Orson Welles. New York,

Oxford University Press, 1978.

City Lights

A silent film at the dawn of the talking picture technological

revolution, City Lights appeared to popular acclaim and remains, for

many, Charlie Chaplin’s finest achievement. When Chaplin, known

the world over for his ‘‘Little Tramp’’ character, began filming City

Lights in 1928, talking pictures had become the rage in the movie

industry, and most filmmakers who had originally conceived of their

works as silent films were now adapting them into partial talkies or

junking them altogether. Chaplin halted production on City Lights to

weigh his options, and, when he resumed work several months later,

he stunned his Hollywood peers by deciding to keep the film in a

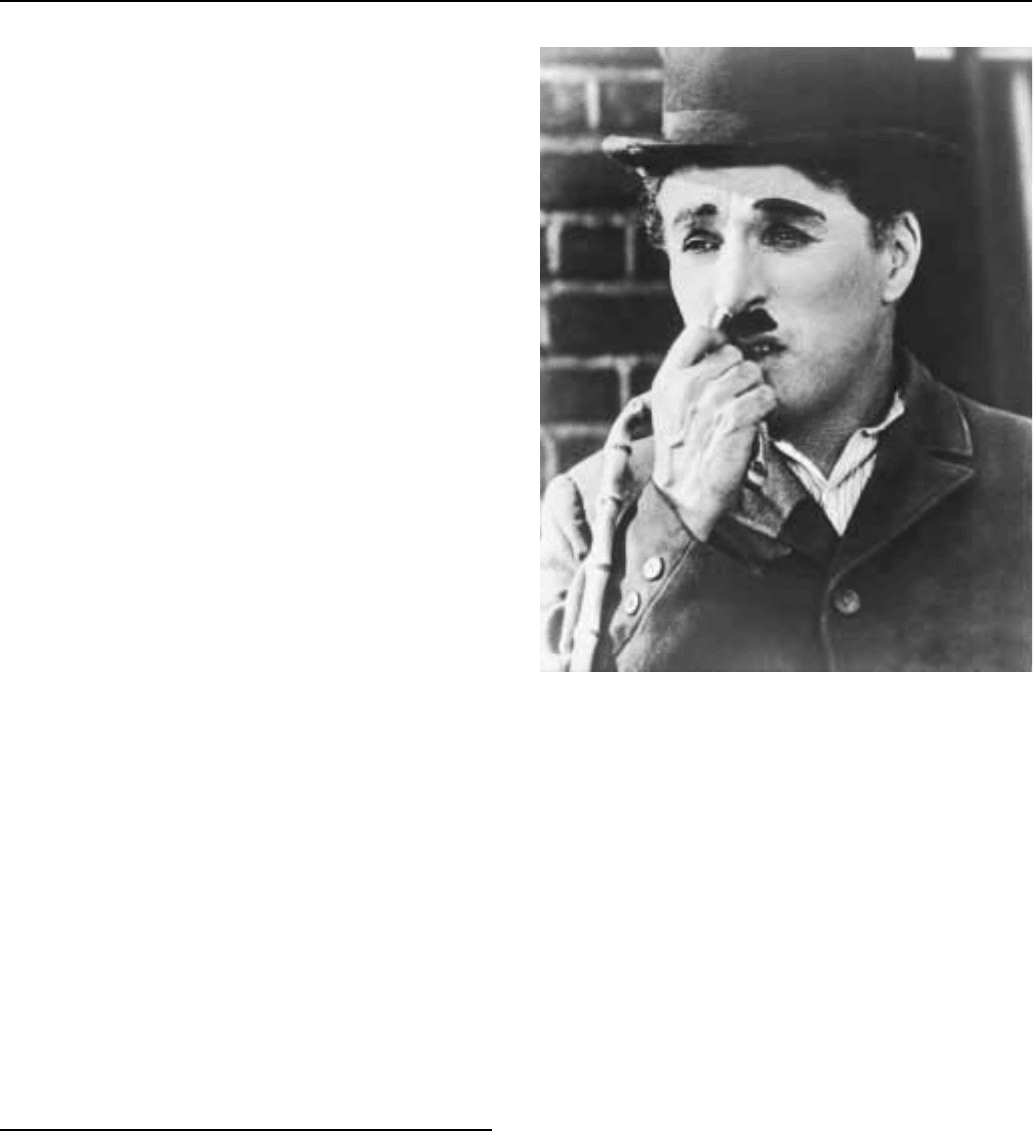

Charlie Chaplin in a scene from the film City Lights.

silent form. ‘‘My screen character remains speechless from choice,’’

he declared in a New York Times essay. ‘‘City Lights is synchronized

[to a musical score] and certain sound effects are part of the comedy,

but it is a non-dialogue picture because I preferred that it be that.’’ For

many, the film that resulted is a finely wrought balance of pathos and

comedy, the very quintessence of Chaplin. The movie debuted in 1931.

Chaplin, who not only produced, directed, and starred in City

Lights but also wrote and edited it and composed its musical score,

centered his film on the Little Tramp and his relationship with a

young, blind flower vendor who has mistaken him for a rich man. The

smitten Tramp, not about to shatter her fantasy, undergoes a series of

comic misadventures while trying to raise money for an operation that

would restore her vision. He interrupts the suicide attempt of a

drunken man who turns out to be a millionaire. The two become

friends, but unfortunately the millionaire only recognizes the Tramp

when drunk. Determined to help the young woman, the Tramp takes

on such unlikely occupations as street sweeping and prize fighting

(both of which go comically awry) before the millionaire finally

offers him one thousand dollars for the operation. Robbers attack at

just that moment, knocking the millionaire in the head. Police arrive

and assume the Tramp is the thief (the millionaire, sobered by the

blow, does not recognize him), but the Tramp manages to give the

money to the woman before they catch him and haul him off to jail.

After his release, he discovers that the young woman, now sighted,

runs her own florist shop. She doesn’t recognize the shabbily dressed

Tramp at first and playfully offers him a flower. When she at last

realizes who he is, the film concludes with the most poignant

exchange of glances in the history of world cinema.

CITY OF ANGELS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

516

Chaplin found the casting of the nameless young blind woman to

be particularly difficult. According to his autobiography, one of his

biggest challenges ‘‘was to find a girl who could look blind without

detracting from her beauty. So many applicants looked upward,

showing the whites of their eyes, which was too distressing.’’ The

filmmaker eventually settled on Virginia Cherrill, a twenty-year-old

Chicagoan with little acting experience. ‘‘To my surprise she had the

faculty of looking blind,’’ Chaplin wrote. ‘‘I instructed her to look at

me but to look inwardly and not to see me, and she could do it.’’ He

later found the neophyte troublesome to work with, however, and

fired her about a year into production. He recruited Georgia Hale, who

had co-starred with him in The Gold Rush in 1925, to replace her but

eventually re-hired Cherrill after realizing how much of the film he

would have to re-shoot.

Chaplin’s problems extended to other aspects of the movie. He

filmed countless retakes and occasionally stopped shooting for days

on end to mull things over. Most famously, he struggled for eighty-

three days (sixty-two of which involved no filming whatsoever) on

the initial encounter of the Tramp and the young woman, unable to

find a way of having the woman conclude that the Tramp is wealthy.

Inspiration finally struck, and Chaplin filmed a brief scene in which a

limousine door slammed shut a moment before the Tramp met her.

Chaplin’s difficulties on the set mattered little to audiences.

They loved his melancholy yet comic tale of two hard-luck people and

made it an unqualified hit (the movie earned a profit of five million

dollars during its initial release alone). A few reviewers criticized the

film’s old-fashioned, heavily sentimental quality, but the majority

praised Chaplin’s work. Its regressive form and content notwithstand-

ing, City Lights appealed strongly to audiences and critics alike.

—Martin F. Norden

F

URTHER READING:

Chaplin, Charles. My Autobiography. New York, Simon and

Schuster, 1964.

———. ‘‘Pantomime and Comedy.’’ New York Times. January 25,

1931, H6.

Maland, Charles J. Chaplin and American Culture: The Evolution of a

Star Image. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989.

Molyneaux, Gerard. Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights. New York,

Garland, 1983.

The City of Angels

The official slogan for the city of Los Angeles (L.A.) is ‘‘Los

Angeles brings it all together.’’ Its unofficial name is ‘‘The City of

Angels.’’ In the first instance, reality belies the motto in that Los

Angeles’ most salient feature is its diffuse layout. In the second, it is

difficult to think of someone saying ‘‘The City of Angels’’ without a

Raymond Chandler-esque sneer. But that, too, is L.A.; duplicitous,

narcissistic, and paradoxical. Perhaps no city has been loved or

abhorred with such equal vigor, or typified by so many contradictions.

For postmodern philosophers (especially Europeans) who study the

city as they would a text, the city fascinates with its sheer moderni-

ty—a tabula rasa over which the thick impasto of America’s aspira-

tions and proclivities has been smeared. Viewed from the air, the city

terrifies with its enormity, but one can discern a map of sorts, a

guidepost pointing towards the future.

From its very beginning Los Angeles has existed more as a sales

pitch than a city; a marketing campaign selling fresh air, citrus fruits,

and the picturesque to the elderly and tubercular. In the 1880s, when

Los Angeles was little more than a dusty border town of Spanish

Colonial vintage, attractively packaged paeans to sun-kissed good-

living were flooding the Midwest. Pasadena was already a well-

known summer destination for East Coast millionaires, and the

campaign sought to capitalize on a keeping-up-with-the-Jones senti-

ment calculated to attract prosperous and status conscious farmers.

Behind the well-heeled came the inevitable array of servants, lackeys,

and opportunists. The farm boom dried-up, and the transplanted,

oftentimes marooned mid-westerners sat on their dusty front porches

wondering where they went wrong—a dominant leit motif of L.A.

literature along with conflagrations, earthquakes, floods, crowd vio-

lence, and abject chicanery.

Until the film industry invaded in the early 1910s, Los Angeles

could offer few incentives to attract industry, lacking a port or even

ready access to coal. The only way civic leaders could entice

businessmen was by offering the most fervently anti-labor municipal

government in the country, and Los Angeles developed a reputation

for quelling its labor unrest with great dispatch. L.A.’s leading lights

were as canny at pitching their real estate holdings as they were

ruthless in ensuring the city’s future prosperity. To insure adequate

water to nourish the growing metropolis, founding father William

Mulholland bamboozled the residents of Owens Valley, some 250

miles to the northeast, into selling their water rights under false

pretenses and building an enormous aqueduct into the San Fernando

Valley. In 1927 the embittered farmers, having witnessed their fertile

land return to desert, purchased an advertisement in the Los Angeles

Times which read: ‘‘We, the farming communities of the Owens

Valley, being about to die, salute you.’’ The publisher of the newspa-

per, General Harrison Gray Otis, was a major investor in Mulholland’s

scheme. Even back then, irony was a way of life in Southern California.

Fate was kind to Los Angeles. With the film industry came

prosperity, and a spur to real estate growth. But beneath the outward

prosperity, signs of the frivolity and moral disintegration L.A. was

famous for provoking were apparent to those with an eye for details.

Thus, Nathaniel West, author of the quintessential Los Angeles novel,

Day of the Locust, could write of a woman in man’s clothing

preaching the ‘‘crusade against salt’’ or the Temple Moderne, where

the acolytes taught ‘‘brain-breathing, secret of the Aztecs,’’ while up

on Bunker Hill, a young John Fante would chronicle the lives of the

hopelessly displaced Midwest pensioners and the sullen ghetto

underclass from his cheap hotel room overlooking downtown. Across

town, European luminaries such as Arnold Schoenberg, Thomas

Mann, and Bertolt Brecht found the leap from Hitler’s Germany to

palm trees and pristine beaches a difficult transition to make. The

contrast between the European exiles and their American counter-

parts was as plain as day, and illustrates the contradictory schools of

thought about the City of Angels. The Europeans regarded the city as

a curiosity to be tolerated, or wondered at, while West, Fante, and

their better known brethren were almost uniform in their strident

denunciations of what they perceived as overt Philistinism. British

novelist Aldous Huxley oscillated between condemnation and ap-

proval. These foreigners perceived the myriad contradictions of Los

Angeles: The beauty of its locale and the crassness of its people; the

film industries’ pollyanna-like flights of fancy and the bitter labor

CIVIL DISOBEDIENCEENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

517

struggles that accompanied their creation; the beauty of the art deco

style that Los Angeles adopted as its own, and the eyesores (building

shaped like hot-dogs, space ships, ginger-bread houses) constructed

alongside them.

For obvious reasons, L.A. became a center for the defense

industry during World War II, and the factories springing up like

mushrooms on the table-flat farmland attracted the rootless detritus of

the Depression, who only a few years back were regularly turned back

at the Nevada border by the California Highway Patrol. The great

influx of transplants flourished in their well-paid aerospace assembly

line jobs, enjoying a semblance of middle class living. It became the

clarion call of a new sales pitch—the suburban myth. The suburbs

marketed a dream, that of single family homes, nuclear families, and

healthful environment. Within a few years, pollution from the legions

of commuters who clogged L.A.’s roadways dispelled the illusion of

country living. Another recent innovation, the shopping mall, while

invented in Seattle, was quickly adopted as a native institution, to the

further degradation of downtown Los Angeles.

The veterans had children, who, nourished on their parent’s

prosperity, became a sizeable marketing demographic. The children

took to such esoteric sports as surfing, hot rodding, and skateboarding,

fostering a nationwide craze for surf music and the stylistic excesses

of hot-rod artists such as Big Daddy Roth. For a time, Los Angeles

persevered under this placid illusion, abruptly collapsed by the 1965

Watts riots and the Vietnam war. In a city without discernible

boundaries, the idea of a city center is an oxymoron. Downtown Los

Angeles, the nexus of old money Los Angeles, slowly withered,

crippled further by urban renewal projects that made the downtown

ghost town something of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

This, then, is L.A., a heady mixture of status and sleaze,

weirdness and conformity, natural beauty and choking pollution. Los

Angeles is indeed the most postmodern of cities, a city with more of a

reflection than an image, and where the only safe stance is the ironic

one. In the early 1990s, L.A. was hit by earthquakes, fires, and another

riot of its black populace, this time provoked by the acquittal of

policeman accused of beating a black motorist more briskly than

usual. Los Angeles once again managed to recover, refusing once

again to be crippled by its inner contradictions. With its limited array

of tropes, the city trots out its endgame against any natural limitations

to its growth. As the city evolves, postmodern theoreticians stand by

rubbing their palms together, predicting the city’s inevitable denoue-

ment while the sun shines mercilessly overhead.

—Michael Baers

F

URTHER READING:

Davis, Mike. City of Quartz. New York, Verso, 1990.

———. Ecology of Fear. New York, Metropolitan Books, 1998.

Didion, Joan. Slouching Towards Bethlehem. New York, Washington

Square Press, 1981.

Fante, John. Ask the Dust. Santa Barbara, Black Sparrow Press, 1980.

Klein, Norman. The History of Forgetting. New York, Verso, 1997.

Lovett, Anthony R., and Matt Maranian. L.A. Bizarro. Los Angeles,

Buzz, 1997.

Pynchon, Thomas. The Crying of Lot 49. New York, Lippincott, 1963.

West, Nathanael. Day of the Locust. New York, Random House, 1939.

Civil Disobedience

Civil disobedience is a nonviolent, deliberate, and conspicuous

violation of a law or social norm, or a violation of the orders of civil

authorities, in order to generate publicity and public awareness of an

issue. Protesters directly confront the rule and confront authorities

who would enforce it, and demand a change in the rule. Civil

disobedience communicates the protesters’ unity and strength of

interest in an issue and provides evidence of their commitment and

willingness to sacrifice for the cause. It also presents a latent threat of

more overt action if the regime fails to act on the issue.

Civil disobedience is a form of political participation available

to citizens without the money, media support, lobbying resources,

voting strength, political skills, or political access necessary to

influence decision-makers through more traditional means. The tactic

was used by Mahatma Gandhi in the 1940s to secure the end of British

colonial rule in India; by Martin Luther King, Jr. and other American

civil rights leaders in the 1960s to end legal racial segregation and to

secure voting rights for African Americans; and by non-voting age

college students during the 1960s to protest America’s war in

Vietnam. Civil disobedience brings people into the political system

who were previously outside the system and is one of the few tactics

available to empower concerned citizens who lack any other means to

press their demands for change. Social minorities and deviant subcul-

tures use civil disobedience to challenge and change the norms of

society or to demand their independence from the rules of society.

Civil disobedience usually takes one of three forms. First, civil

disobedience may take the form of deliberate and purposeful violation

of a specific targeted statute or social norm in order to focus popular

and media attention on the rule, to encourage others to resist the rule,

and to encourage authorities to change the rule. Examples include

1960s American civil rights sit-ins and demands for service at

segregated lunch counters, anti-war protesters refusing to submit to

selective service calls, and feminists publicly removing restrictive

brassieres in protest of clothing norms. In the 1970s, trucker convoys

deliberately exceeded the 55-mile-per-hour federal highway speed

limit to protest the limit. According to Saul Alinsky in Rules for

Radicals, this tactic is effective only in non-authoritarian and non-

totalitarian regimes with a free press to publicize the violation of the

law and basic civil rights to prevent civil authorities and social

majorities from overreacting to the violation.

Second, civil disobedience may take the form of passive resist-

ance in which protesters refuse to respond to the orders of authorities

but are otherwise in full compliance with the law. Examples have

included civil rights protesters and anti-war activists who ignore

police orders to disperse and force police to physically carry them

from a public protest site. Feminists have resisted social norms by

refusing to shave their legs. The organization Civilian Based Defense

promoted passive resistance as a national defense strategy and sug-

gested that the threat of withholding cooperation and engaging in

active non-cooperation with the enemy may be as effective a deterrent

to an invader’s aggression as the use of military force.

Third, civil disobedience may take the form of non-violent

illegal activity in which protesters disrupt activities they oppose and

seek to be arrested, punished, and even martyred to gain publicity and

to influence public opinion. Examples have included anti-war protest-

ers who trespass on military installations and illegally seize military

property by chaining themselves to it, radical environmentalists who

CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR CULTURE

518

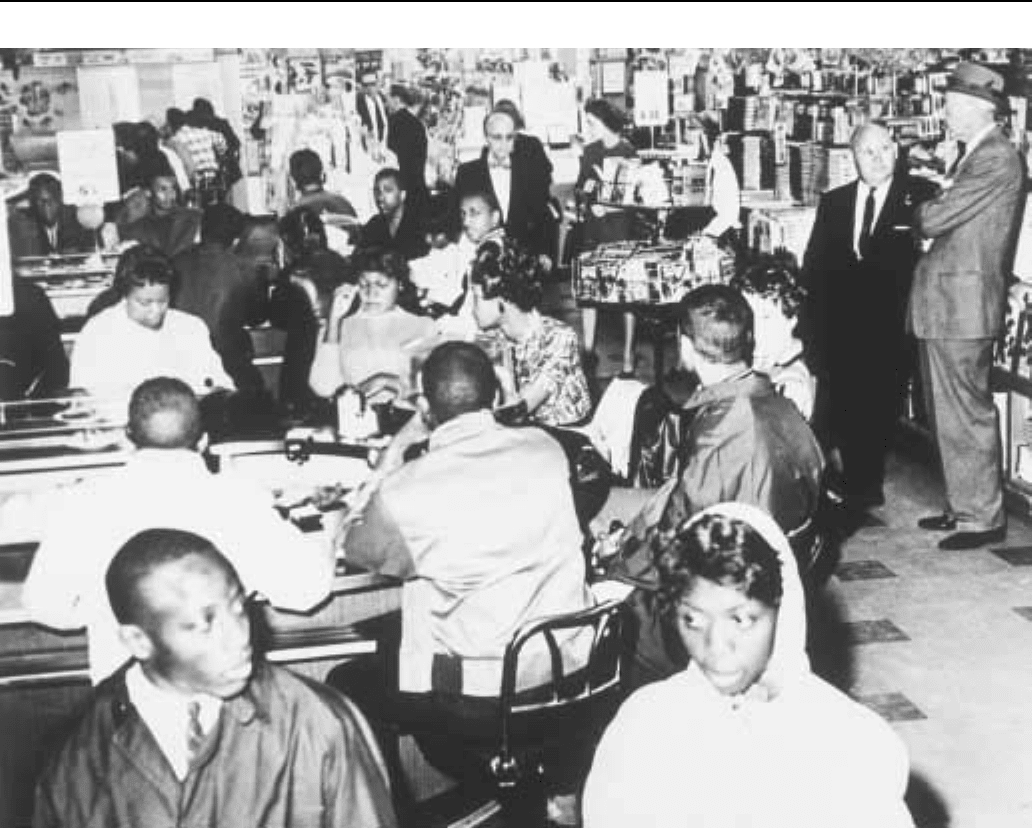

Student protesters at Woolworth’s lunch counter, Atlanta, Georgia, 1960.

‘‘spike’’ trees with nails to disrupt logging activities, and animal

rights activists who throw blood on persons wearing animal fur coats.

Civil disobedience is distinctly different from nonconformity,

social pathology, eccentricity, or social disorganization. Nonconformity

is willful violation of a rule because the values established in the rule

are contrary to the social, cultural, or moral values and norms of a

subgroup of the civil society—but the violation is not intended to

encourage a change in the rule. For example, a fundamentalist

Mormon practices polygamy because he believes religious proscriptions

require him to do so, not because he seeks to change or protest the

marriage laws of the state. Social pathology is the failure to conform

to civil law because failures in the individual’s socialization and

education processes leave the individual normless and, therefore, free

to pursue his personal self-interest and selfish desires without concern

for law. Eccentricity is socially encouraged nonconformance in which a

cultural hero, genius, intellectual, or artist is granted cultural license

to violate the law based on the person’s unique status or contributions

to society. Finally, social disorganization is the failure of the political

or social system to enforce its rules because authority has become

ineffective or has been destroyed in war or revolution, leaving

individuals in a state of anarchy and licensed to make their own rules.

Civil disobedience as a political tactic and social process in-

creases in popularity and use as society decreases its reliance on

violence and force to achieve political goals or to gain the advantage

in social conflict or competition. It also increases in popularity when

political outsiders seek to assert themselves in the political process

and find all other avenues of political participation beyond their

abilities and resources or find all other avenues prohibited to them by

political insiders or by civil authorities.

—Gordon Neal Diem

F

URTHER READING:

Alinsky, Saul. Rules for Radicals. New York, Random House, 1971.

Ball, Terence. Civil Disobedience and Civil Deviance. Beverly Hills,

California, Sage Publications, 1973.

Bay, Christian, and Charles Walker. Civil Disobedience: Theory and

Practice. Saint Paul, Minnesota, Black Rose Books, 1975.

Bedau, Hugo. Civil Disobedience: Theory and Practice. New York,

Pegasus, 1969.