Pike Robert, Neal Bill. Corporate finance and investment: decisions and strategy

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

.

Chapter 13 Treasury Management and working capital policy 325

We pick up the last two points later, but deal with the structural issues in the fol-

lowing sections.

■ Degree of centralisation

Even in the most highly decentralised companies, it is common to find a centralised

treasury function. The advantages of centralisation are self-evident:

1 The treasurer sees the total picture for cash, borrowings and currencies and is there-

fore able to influence and control financial movements on a global basis to achieve

maximum after-tax benefit. The gains from centralised cash management can be

considerable.

2 Centralisation helps the company develop greater expertise and more rapid knowl-

edge transfer.

3 It permits the treasurer to capture any benefits of scale. Dealing with financial and

currency markets on a group basis not only saves unnecessary duplication of effort,

but should also reduce the cost of funds.

The major benefits from decentralising certain treasury activities are:

■ By delegating financial activities to the same degree as other business activities, the

business unit becomes responsible for all operations. Divisional managers in cen-

tralised treasury organisations are understandably annoyed at being assessed on

profit after financing costs, over which they have little direct control.

■ It encourages management to take advantage of local financing opportunities of which

group treasury may not be aware and be more receptive to the needs of each division.

■ Profit centres and cost centres

In many large multinational firms, there is a substantial flow of cash each year in both

domestic and foreign currencies. The volumes involved offer the opportunity to speculate,

UK TREASURER

International Consumer Products Group

West London

■ UK headquartered consumer products group with wide range of household name

brands. Turnover exceeds £3 billion from some 40 countries.

■ Will be a member of a small team reporting to the Group Treasurer and will have

responsibility for all banking, supported by a team of two.

■ Principal activities will cover the dealing area; cash management systems and liaison

with the Group’s bankers; interest risk management, both forex and interest rate; and

ad hoc projects including overseas banking reviews

■ Graduate, part or fully qualified ACT with hands-on dealing room experience.

Background is likely to be within a substantial international group. An accountancy

qualification would be advantageous.

■ Excellent communicator, able to quickly establish credibility and develop sound work-

ing relationships across the business. A team-worker with flexibility of approach, com-

mitted to technical excellence.

■ This is a first-class opportunity within a group which has an excellent reputation for its

pro-active approach to treasury management.

A typical job advertisement in the press.

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 325

.

especially if the more favourable interest rates and exchange rates are available. Moreover,

such firms probably employ staff skilled in cash and foreign exchange management tech-

niques and may decide to use these resources pro-actively, i.e. to make a profit.

In a profit centre Treasury (PCT), staff are authorised to take speculative positions,

usually within clearly specified limits, by trading financial instruments in the same way

as a bank. Such ‘in-house banks’ are judged on their return on capital achieved, although

it is difficult to arrive at an accurate measure of capital employed. The main problem

with operating a profit centre is that traders may exceed their permitted positions, either

through negligence or in pursuit of personal gain. (See the Barings case on page 333.)

Conversely, a cost centre Treasury (CCT) aims at operating as efficiently as possible,

and eliminates risks as soon as they arise. DS Smith, the firm in the introductory case,

clearly operates a CCT, i.e. it hedges rather than speculates, as a matter of policy.

JP Morgan Fleming conducts an annual survey of cash and treasury management

practices, in conjunction with the ACT. In 2003, it found that 82 per cent of its 347

respondents considered their treasury function to be a cost centre (aiming ‘to manage

the exposure providing value-added solutions that do not increase the risk of the com-

pany’), while 18 per cent considered their Treasury to be a profit centre (aiming ‘to take

active balance sheet risks to enhance returns’).

326 Part IV Short-term financing and policies

profit centre treasury

(PCT)

A corporate treasury that aims

to makes a profit from its

dealing – managers are judged

on profit performance

cost centre treasury (CCT)

A treasury that aims to min-

imise the cost of its dealings

13.3 FUNDING

Corporate finance managers must address the funding issues of: (1) how much should

the firm raise this year, and (2) in what form? We devote two later chapters to these

questions, examining long-, medium- and short-term funding. For the present, we sim-

ply raise the questions that subsequent chapters will pursue in greater depth.

1 Why do firms prefer internally generated funds? Internally generated funds, defined as

profits after tax plus depreciation, represent easily the major part of corporate funds.

In many ways, it is the most convenient source of finance. One could say it is equiv-

alent to a compulsory share issue, because the alternative is to pay it all back to share-

holders and then raise equity capital from them as the need arises. Raising equity

capital, via the back door of profit retention, saves issuing and other costs. But, at the

same time, it avoids the company having to be judged by the capital market as to

whether it is willing to fund its future operations in the form of either equity or loans.

2 How much should companies borrow? There is no easy solution to this question. But it

is a vital question for corporate treasurers. Borrow too much and the business could

go bust; borrow too little and you could be losing out on cheap finance.

The problem is made no easier by the observation that levels of borrowing dif-

fer enormously among companies and, indeed, among countries. Levels of bor-

rowing in Italy, Japan, Germany and Sweden are generally higher than in the UK

and the USA. One reason is the difference in the strength of relationship between

lenders and borrowers. Bankers in Germany and Japan, for example, tend to take

a longer-term funding view than UK banks. Japanese banks may even form part

of the same group of companies. For example, the Bank of Tokyo, one of Japan’s

Self-assessment activity 13.1

How would you define treasury management?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

Let us now examine the four pillars of treasury management: funding, banking rela-

tionships, risk management, and liquidity and working capital.

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 326

.

Chapter 13 Treasury Management and working capital policy 327

leading banks, is part of the Mitsibushi conglomerate (www.mitsibushi.com). We

devote Chapters 18 and 19 to the key question of how much a firm should borrow.

3 What form of debt is appropriate? If the strategic issue is to decide upon the level of

borrowing, the tactical issue is to decide on the appropriate form of debt, or how to

manage the debt portfolio. The two elements comprise the capital structure deci-

sions. The debt mix question considers:

(a) form – loans, leasing or other forms?

(b) maturity – long-, medium- or short-term?

(c) interest rate – fixed or floating?

(d) currency mix – what currencies should the loans be in?

The first three issues are discussed in Chapters 15 and 16 and currency issues are

dealt with in Chapter 22.

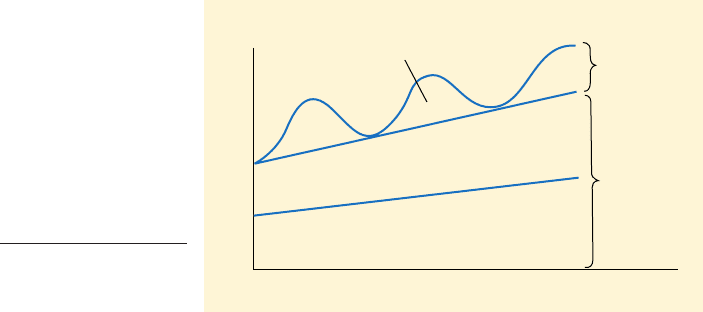

4 How do you finance asset growth? Each firm must assess how much of its planned

investment is to be financed by short-term finance and how much by long-term

finance. This involves a trade-off between risk and return.

Current assets can be classified into:

(a) Permanent current assets – those current assets held to meet the firm’s long-term

requirements. For example, a minimum level of cash and stock is required at

any given time, and a minimum level of debtors will always be outstanding.

(b) Fluctuating current assets – those current assets that change with seasonal or

cyclical variations. For example, most retail stores build up considerable stock

levels prior to the Christmas period and run down to minimum levels follow-

ing the January sales.

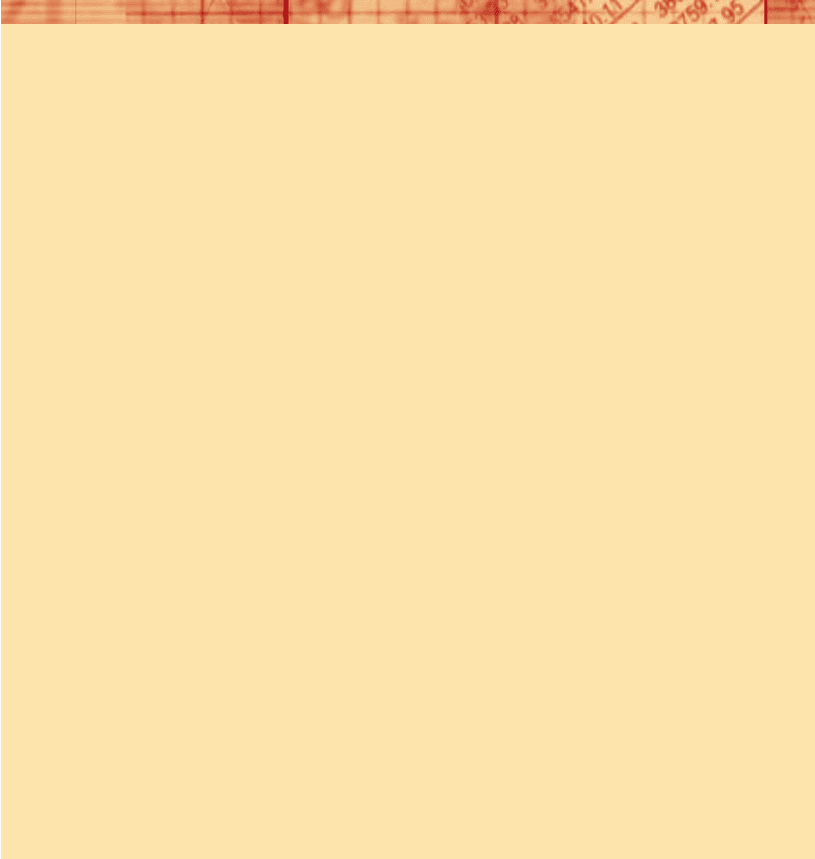

Figure 13.1 illustrates the nature of fixed assets and permanent and fluctuating cur-

rent assets for a growing business. How should such investment be funded? There are

several approaches to the funding mix problem.

First, there is the matching approach (Figure 13.1), where the maturity structure of

the company’s financing exactly matches the type of asset. Long-term finance is used

to fund fixed assets and permanent current assets, while fluctuating current assets are

funded by short-term borrowings.

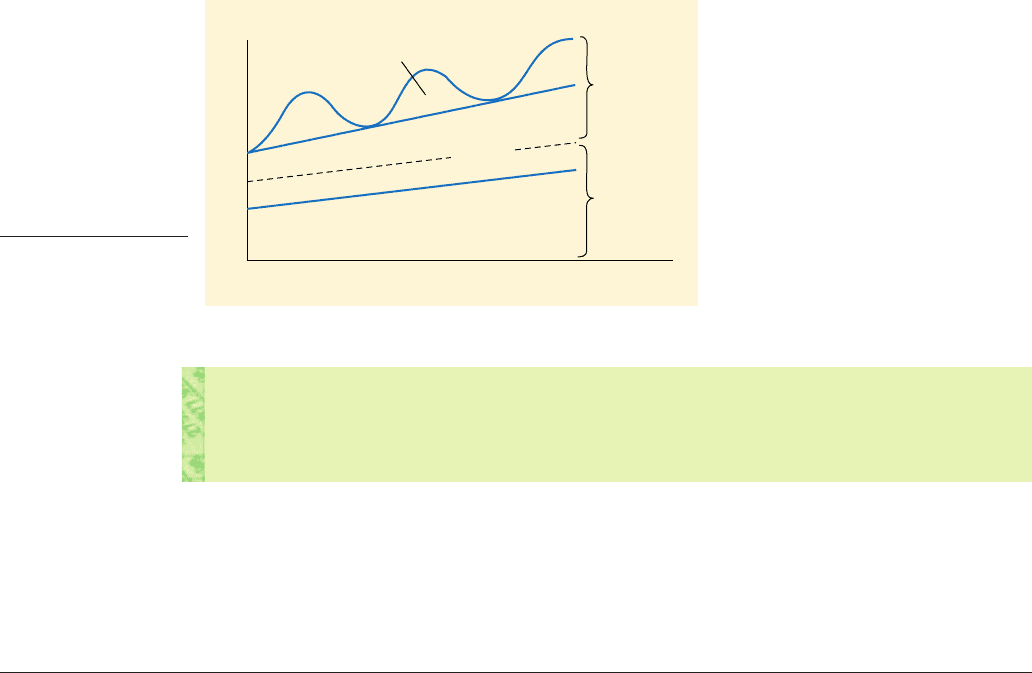

A more aggressive and risky approach to financing working capital is seen in Figure

13.2, using a higher proportion of relatively cheaper short-term finance. Such an

approach is more risky because the loan is reviewed by lenders more regularly. For

example, a bank overdraft is repayable on demand. Finally, a relaxed approach would

be a safer but more expensive strategy. Here, most if not all the seasonal variation in

current assets is financed by long-term funding, any surplus cash being invested in

short-term marketable securities or placed in a bank deposit.

Permanent current assets

Fixed assets

Time

Long-term

borrowing

+

equity

capital

Short-term

borrowing

Fluctuating

current assets

Capital (£)

0

Figure 13.1

Financing working

capital: the matching

approach

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 327

.

328 Part IV Short-term financing and policies

The issue of whether to borrow long-term or short term is examined in more detail

in the next section.

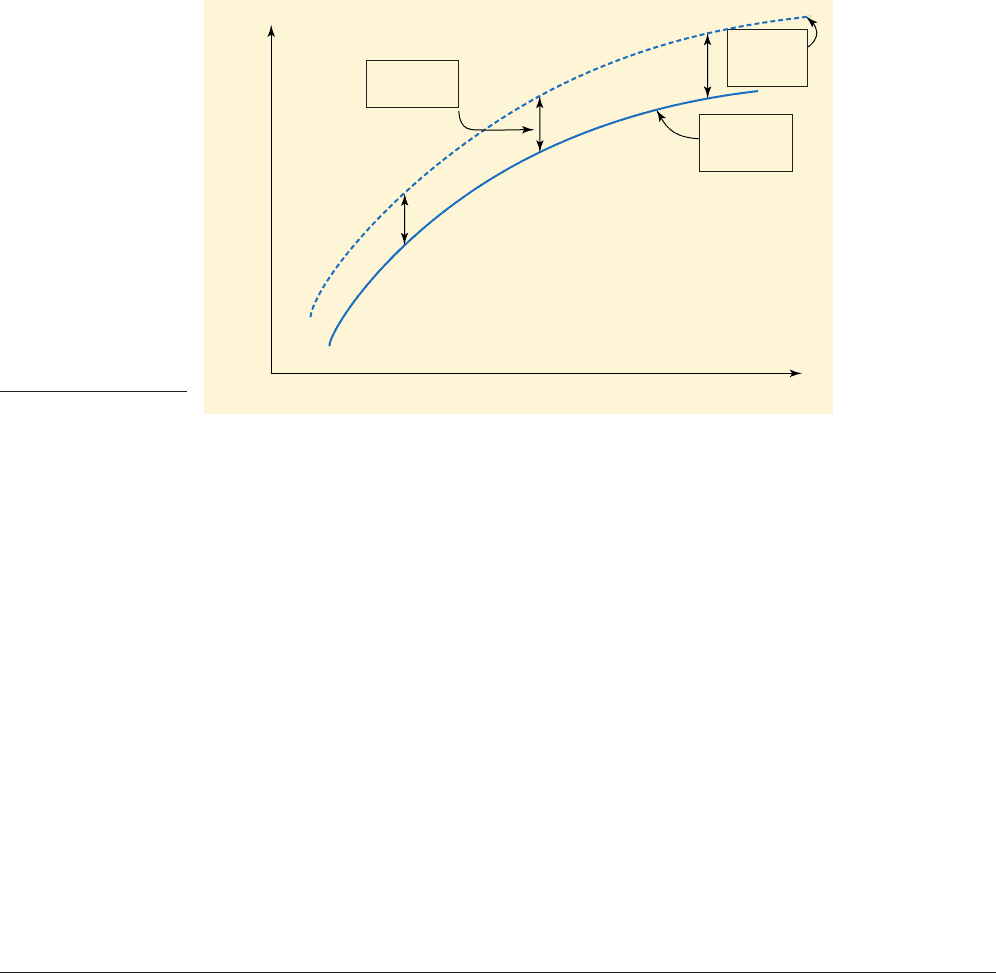

13.4 HOW FIRMS CAN USE THE YIELD CURVE

In Chapter 3, we examined the term structure of interest rates showing the yields on

securities of varying times to maturity. The yield curve offers important information to

treasury managers wanting to borrow funds. Although it is based on the structure of

yields on government stock, similar principles apply to the market for corporate loans,

or bonds. However, corporates have higher default risk than governments so that mar-

kets require higher yields on corporate bonds.

The market for government stock provides a benchmark that dictates the gener-

al shape of the yield curve with the curve for corporate bonds located above this.

Figure 13.3 reproduces Figure 3.3 with an additional yield curve to describe yields

in the market for corporate bonds. The distance between the two lines represents

the premium required by the market to cover the risk of default by corporate bor-

rowers. For top-grade corporate borrowers, with a very high credit rating, the pre-

mium will be relatively narrow, whereas firms considered to be more risky will be

subject to higher risk premia. The corporate versus government yield premium

would usually widen with time to maturity as corporate insolvency risk probably

increases with time.

Today’s yield curve incorporates how people expect interest rates to move in the

future. An upward-sloping yield curve reflects investors’ expectations of higher future

interest rates and vice versa. The action points are clear:

■ A rising yield curve may be taken to imply that higher future interest rates are

expected. This suggests firms might borrow long-term now, and avoid variable

interest rate borrowing.

■ A falling yield curve may be taken to imply that lower future interest rates are

expected. This suggests firms might borrow short-term now, and utilise variable

interest rate borrowing.

Permanent current assets

Fluctuating

current assets

Short-term

borrowing

Long-term

borrowing

+

equity

capital

Fixed assets

Capital (£)

Time

0

Figure 13.2

Financing working

capital needs: an

aggressive strategy

Self-assessment activity 13.2

What do you understand by the matching approach in financing fixed and current assets?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 328

.

Chapter 13 Treasury Management and working capital policy 329

Default risk

premium

Yields on

corporate

bonds

Yields on

government

securities

Yield

(%)

Years to maturity

Figure 13.3

Yield curves

■ Words of warning

In some circumstances, managers may be deceived by short-term rates. Say, they follow

a policy of borrowing at short-term rates while the yield curve is upward-sloping,

planning to switch to long-term borrowing when short-term rates exceed long-term

rates.

For example, Jordan plc wants to borrow for six years, and the yield curve current-

ly slopes upwards. The yields on five-year and six-year bonds are 5.5 per cent and

5.8 per cent respectively, while the yield on one-year bonds is 5.0 per cent. So, Jordan

goes for one-year bonds, planning to issue a five-year bond a year later. But what if, a

year later, the whole yield curve shifts upwards due to macro-economic changes, e.g.

a rise in the expected rate of inflation, so that Jordan has to pay say, 7.5 per cent on a

five-year bond? Obviously, this is now more expensive than arranging to lock in the

5.8 per cent rate at the base year. Equally obviously, the reverse could apply – Jordan

may benefit from a downward shift in the yield curve. However, the point is that firms

should not be over-influenced by relatively small differentials along the yield curve.

We examine specific methods of short- and medium-term borrowing in Chapter 15

and methods of long-term borrowing in Chapter 16.

13.5 BANKING RELATIONSHIPS

Many large companies deal with several banks in order to maximise their access to

credit. Global businesses may deal with hundreds of banks; Eurotunnel, at one time,

had 225 banks to deal with! The number of banks dealt with will depend on the com-

pany’s size, complexity and geographical spread. While it makes sense to have more

than one bank, too many can make it difficult to foster strong relationships. The real

value of a good banking relationship is discovered when things get tough and when

continued bank support is required.

We often hear the charge, particularly from smaller businesses, that banks are provid-

ing an inadequate service or charging too high interest rates. It seems that the banking

relationship can be more of a love/hate relationship than a healthy financial partnership.

A flourishing banking relationship requires the company to deal openly, honestly

and regularly with the bank, keeping it informed of progress and ensuring there are

no nasty surprises.

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 329

.

330 Part IV Short-term financing and policies

Self-assesment Activity 13.3

Take a look at the latest Annual Report of Cadbury Shweppes (www.cadburyschweppes.com).

What does the Operating and Financial Review say about its treasury risk management policy?

13.6 RISK MANAGEMENT

The financial manager should recognise the many types of risk to be managed:

■ Liquidity risk – managing corporate liquidity to ensure that funds are in place to

meet future debt obligations. We discuss this later in the chapter.

■ Credit risk – managing the risks that customers will not pay. We discuss this in the

next chapter.

■ Market risk – managing the risk of loss arising from adverse movements in market

prices in interest rates, foreign exchange, equity and commodity prices. It is this

form of risk that we now consider.

Every business needs to expose itself to risks in order to seek out profit. But there

are some risks that a company is in business to take, and others that it is not. A major

company, like Ford, is in business to make profits from making cars. But is it also in

business to make money from taking risks on the currency movements associated with

its worldwide distribution of cars?

While the risks of business can never be completely eliminated, they can be man-

aged. Risk management is the process of identifying and evaluating the trade-off

between risk and expected return, and choosing the appropriate course of action.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is all too easy to see that some decisions were

‘wrong’. In this sense, errors of commission are more visible than errors of omission;

the decision to invest in a risky project which subsequently fails is more obvious than

the rejected investment which competitors take up with great success. As with all

aspects of decision making, risk management decisions should be judged in the light

of the available information when the decision is made. The treasurer plays a vital role

in identifying, assessing and managing corporate risk exposure in such a way as to

maximise the value of the firm and ensure its long-term survival.

■ Stages in the risk management process

Identify risk exposure. Taking risks is all part of business life, but businesses need to be

quite sure exactly what risks they are taking. For example, while a firm will probably

insure against the risk of fire, it may not consider the risk of loss of profits from the

resulting disruption of the fire. The Brazilian coffee farmer could see his whole crop

wiped out by a late frost. The UK fashion exporter could see her profit margins disap-

pear because of the strong value of sterling.

Before any attempt is made to cover risks, the treasurer should undertake a com-

plete review of corporate risk exposure, including business and financial risks. Some

of these risks will naturally offset each other. For example, exports and imports in the

same currency can be netted off, thereby reducing currency exposure.

Evaluate risks. We saw in Chapter 8, that there are various ways in which the risks

of investments can be forecast and evaluated. The decision as to whether the risk expo-

sure should be reduced will depend on the corporate attitude to risk (i.e. its degree of

risk aversion) and the costs involved. Hedgers take positions to reduce exposure to

risk. Speculators take positions to increase risk exposure.

hedgers

Hedgers tries to minimise or

totally eliminate exposure to

risk

speculators

Speculators deliberately take

positions to increase their

exposure to risk, hoping for

higher returns.

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 330

.

Chapter 13 Treasury Management and working capital policy 331

Manage risks. The treasurer can manage risk exposure in four ways: risk retention,

avoidance, reduction and transfer, each of which is considered below.

1 Risk retention. Many risks, once identified, can be carried – or absorbed – by the firm.

The larger and more diversified the firm’s activities, the more likely it is to be able

to sustain losses in some areas. There is no need to pay premiums to market insti-

tutions when the risk can easily be absorbed by the company. Firms may hold pre-

cautionary cash balances, or maintain lower than average borrowing levels, in order

to be better able to absorb unanticipated losses. It should, of course, be borne in

mind that there are costs associated with such action, particularly the lower return

to the firm from holding such large cash balances.

2 Risk avoidance. Some businesses prefer to keep well away from high-risk invest-

ments. They prefer to stick to conventional technology rather than promising new

technology manufacture, and to avoid doing business with countries with volatile

exchange rates. Such risk-avoiding behaviour may be acceptable in the short term,

but, ultimately, it threatens the firm’s competitiveness and survival.

3 Risk reduction. We all that know that by having a good diet and taking the right

amount of exercise, we can reduce our exposure to the risk of catching a cold.

Similarly, firms can reduce exposure to failure by doing the right things. Risk of

fire can be reduced by an effective sprinkler system; risk of project failure can be

reduced by careful planning and management of the implementation process and

clear plans for abandonment at minimum cost should the need arise.

4 Risk transfer. Where a risk cannot be avoided or reduced and is too big to be

absorbed by the firm, it can be turned into someone else’s problem or opportunity

by ‘selling’, or transferring, it to a willing buyer. Bear in mind that most risks are

two-sided. There may be a speculator willing to acquire the very risk that the

hedger firm wishes to lose. It is this area of risk transfer which is of particular

importance to corporate finance. Whole markets and industries have developed

over the years to cater for the transfer of risk between parties.

Risk can be transferred in three main ways.

■ Diversification. We saw, in Chapter 9, that the risk exposure of the firm or share-

holder can be considerably reduced by holding a diversified portfolio of invest-

ments. Diversification rarely eliminates all risk because most assets have returns

positively correlated with the returns from other assets in the portfolio. It does,

however, eliminate sufficient risk for the firm to consider absorbing the remaining

risk exposure.

■ Insurance. This seeks to cover downside risk. A premium is paid to the insurer to

transfer losses arising from insured events but to retain any gains. As we saw in

Chapter 12, financial options are a form of insurance whereby losses are transferred

to others while profits are retained.

■ Hedging. With hedging, the firm exchanges, for an agreed price, a risky asset for a

certain one. It is a means by which the firm’s exposure to specific kinds of risk can

be reduced or ‘covered’. Hence the fashion exporter can now enter into a contract

guaranteeing an exchange rate for her exports to be paid in three months’ time.

Similar hedges can be created for risks in interest rates, commodity prices and many

more transactions.

Hedging has a cost, often in the form of a fee to a financial institution, but this cost

may well be worth paying if hedging reduces financial risks. The extent to which an

exposure is covered is termed the hedge efficiency: eliminating all financial risk is a

‘perfect hedge’ (i.e. 100 per cent efficiency).

Bako Ltd is a medium-size bakery business. The financial manager has identified that

its main risk exposures lie in the following areas:

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 331

.

332 Part IV Short-term financing and policies

Risk exposure Market hedge

Raw material prices – specifically, flour and sugar Commodity

Currency movements on imports and exports Currency

Interest rate movements on its variable-rate borrowings Financial

Loss of profits, e.g. lost production from a possible Insurance

bakery fire or a bad debt

The first three risks can be managed through hedging in the commodity, currency

and financial markets, letting the market bear the risks. The last can be covered

through various forms of insurance.

■ Derivatives

The financial instruments employed to facilitate hedging are termed derivatives,

because the instrument derives its value from securities underlying a particular asset,

such as a currency, share or commodity. One of the earliest derivatives was money

itself, which for centuries derived its value from the gold into which it could be con-

verted. ‘Derivative’ has today become a generic term that is used to include all types of

relatively new financial instruments, such as options and futures.

The esoteric world of derivatives has hardly been out of the news in recent years.

Procter & Gamble, Barings Bank, Metallgesellschaft and Kodak are all examples of

major businesses whose corporate fingers have been burned through derivative trans-

actions. Although sometimes viewed as instruments of the devil, derivatives are real-

ly nothing more than an efficient means of transferring risk from those exposed to it,

but who would rather not be (hedgers), to those who are not, but would like to be

(speculators).

Derivatives are financial instruments, such as options or futures, which enable

investors either to reduce risk or speculate. They offer the treasurer a sophisticated

‘tool-box’ to manage risk. A risk management programme should reduce a company’s

exposure to the risks it is not in business to take, while reshaping its exposure to those

risks it does wish to take. Risk exposure comes mainly in unexpected movements in

interest rates, commodity prices and foreign exchange, all of which should be managed.

There are, essentially, four main types of derivative: forwards, futures, swaps and

options.

Forward contracts

A forward contract is an agreement to sell or buy a commodity (including foreign cur-

rency) at a fixed price at some time in the future. In business, buyers and sellers are

often subject to exactly opposite risks. The manufacturer of confectionery is concerned

that the price of sugar may rise next year, while the sugar cane producer is concerned

that the price may fall. In a world where it is extremely difficult to predict future com-

modity prices, both parties may want to exchange uncertain prices for sugar delivered

next year for a fixed price.

By agreeing a price for sugar delivery next year, the confectionery manufacturer

hedges against prices escalating, while the sugar cane producer hedges against prices

dropping. They do this by entering into a forward contract, enabling future transac-

tions and their prices to be agreed today, but not to be paid for until delivery at a spec-

ified future date.

Forward markets exist for most of the major commodities (e.g. cocoa, metals and

sugar), but even more important is the forward market in foreign exchange.

A forward currency contract is when a company agrees to buy or sell a specified

amount of foreign currency at an agreed future date and at a rate that is agreed in

advance.

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 332

.

Chapter 13 Treasury Management and working capital policy 333

For example, if you want to pay US$50,000 in six months’ time, you can use a for-

ward contract to hedge against adverse currency movements. You can agree a price

today that will pay for the dollars by arranging with your bank to buy dollars forward.

At the end of six months, you pay the agreed sum and take delivery of the US dollars

(see Chapter 21 for a fuller explanation).

Futures contracts

Like a forward contract, a futures contract is a commitment to buy or sell an asset at an

agreed date and at an agreed price. The difference is that futures are standardised in

terms of period, size and quality and are traded on an exchange. In the UK, this is the

London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange (LIFFE).

A chemical company plans to buy crude oil in three months’ time. The spot price

(i.e. current market price) for Brent crude is $40 a barrel and a three month futures con-

tract can be agreed at $42 a barrel. To guard against the possibility of an even higher

price rise, the company enters a ‘long’ futures position (i.e. agrees to buy) at $42 a bar-

rel, thereby reducing its exposure to oil price hikes. If, in three months time, the spot

oil price has risen beyond $42, the company will not suffer unforeseen losses.

No future in futures for Barings?

When Nick Leeson was posted by the Barings group to work as a clerk at Simex, the

Singapore International Monetary Exchange, who would have thought that he would eventu-

ally, apparently single-handedly, bring the famous bank to its knees?

He progressed well and by 1993 had risen to general manager of Barings Futures

(Singapore), a 25-person operation that ran the bank’s Simex activities. The original role of the

operation was to allow clients to buy and sell futures contracts on Simex, but the group

decided to focus on trading on its own account as part of its group strategy. In the first seven

months of 1994, Leeson’s department generated profits of US$30.7 million, one-fifth of the

whole of Barings’ group profits in the previous year.

The bank set up an integrated Group Treasury and Risk function to try to manage its risk

exposure better. Leeson adopted a new strategy of buying and selling options (or ‘straddles’)

on the Nikkei 225 index, paying the premium into a secret trading account. In effect, he was

betting on the market not having sharp movements up or down. But on 17 January 1995, an

earthquake hit Japan, causing immense damage and loss of life. It also led to a collapse of the

Nikkei 225 index, exposing Barings to huge losses.

Leeson’s response was to invest heavily in buying Nikkei futures contracts in an apparent

attempt to support the market price. Some have suggested he was simply applying the tradi-

tional ‘wisdom’ of trying to salvage an otherwise hopeless position by a ‘double-or-quits’

approach. If so, the high-risk strategy backfired. The result is well known: Barings Futures

(Singapore) lost million for the group, leaving the group with no future and resulting

in its acquisition by the Dutch bank Internationale Nederlandes Group (ING) for

Nick Leeson left the following fax for his boss in London: ‘Sincere apologies for the predica-

ment that I have left you in.’

Was it the use of futures derivatives that brought Barings down? Derivatives were certainly

involved, and it is hardly conceivable that such a disaster could have arisen from, say, share

dealing. But it was the strategy and lack of controls – not the instrument – that were the real

problems. To ban derivatives on the grounds that they are dangerous instruments would be

akin to banning cars because they lead to more accidents than bicycles. But we all know that

it is usually the person behind the wheel, not the car, that is at fault. Similarly, it is the deriva-

tives trader and his or her trading strategy that are really the problem when spectacular col-

lapses like that of Barings occur.

£1.

£860

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 333

.

334 Part IV Short-term financing and policies

If, however, just before delivery, the spot price has fallen to $38 a barrel, the com-

pany will want to benefit from the lower price. It will buy at the spot price and cancel

the long contract by entering into a short contract (i.e. an agreement to sell) at around

the $38 spot price. The loss of $4 a barrel on the two contracts is offset by the profit of

$4 from buying at the spot rather than the original futures price.

Why might a company prefer a futures contract when a forward contract could be

tailor-made to meet its specific requirements? The main reason lies in the obvious ben-

efits from trading through an exchange, not least that the exchange carries the default

risk of the other party failing to abide by the contract terms, so-called ‘counterparty

risk’. For this benefit, both the buyer and seller must pay a deposit to the exchange,

termed the ‘margin’.

Financial futures have become highly popular among both hedgers and traders,

who buy or sell futures in order to profit from a view that the market will go up or

down. The main forms of financial futures contracts cover short-term interest futures,

bond futures and equity-linked futures using stock market indices.

Swaps

Swaps are arrangements between two firms to exchange a series of future payments. A

swap is essentially a long-dated forward contract between two parties through the

intermediation of a third party, such as a bank. For example, a company might agree to

a currency swap, whereby it makes a series of regular payments in yen in return for

receiving a series of payments in US dollars.

Options

An option gives the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an asset at an agreed

price at, or up to, an agreed time. It is this right not to exercise the option that distin-

guishes it from a future. We discussed options in Chapter 12.

A farmer has a ripening crop which he plans to sell in September. He would like to

benefit from any price movements but also be ‘insured’ against any fall in price. A put

option (i.e. the right to sell at an agreed price) is rather like insurance. If the price falls,

the option to sell at an agreed price is exercised. If the price rises, the option is not exer-

cised, and the spot price at the date of sale is taken.

Self-assessment activity 13.4

Consider the following example of a company which plans to buy aluminium. It enters

into a call option contract, paying an appropriate premium for the right to buy alumini-

um at $1,500/tonne in three months’ time. If, at the end of the period, the spot price is

$1,400/tonne, should the company exercise its option or let it lapse?

(Answer in Appendix A at the back of the book)

■ To hedge or not to hedge

Does hedging enhance shareholder value? Some argue that it helps firms achieve com-

petitive advantage over rivals by cost-effectively reducing risks over which it has lit-

tle experience and exploiting those risks over which it has strong levels of competence.

Pure theorists, on the other hand, argue that corporate hedging is a costly process

doing no favours for shareholders. After all, portfolio diversification by investors is

one form of hedging. Corporate hedging does nothing that shareholders could not do

themselves, employing derivatives in exactly the same way as corporate treasurers to

follow their own risk management strategy. So why do most large companies hedge?

All shareholders in a business have a vested interest in its long-run prosperity and

hedging risk exposure is an important means of avoiding financial distress.

CFAI_C13.QXD 10/26/05 11:42 AM Page 334