Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

84

4

East Indian immigration See I

NDIAN

IMMIGRATION

.

Ecuadorean immigration

Almost all Ecuadorean immigration to North America has

occurred since the 1960s. In the U.S. census of 2000 and

the Canadian census of 2001, 260,559 Americans and

8,785 Canadians claimed Ecuadorean descent. Some assess-

ments place the U.S. figures at more than twice that

amount, taking into account a high rate of illegal immigra-

tion. During the mid-1990s, the Ecuadorean consulate in

Manhattan estimated the total number of Ecuadoreans to be

almost twice the official figure. In 2000, the Immigration

and Naturalization Service estimated that 108,000

Ecuadoreans were in the United States illegally. More than

half of Ecuadoreans live in New York City, with a substan-

tial population also in Los Angeles. In Canada, more than

80 percent of Ecuadoreans live in Ontario.

Ecuador occupies 106,800 square miles of northwestern

South America between 2 degrees north latitude and 5

degrees south latitude. Colombia forms the country’s border

to the north, Peru to the east and to the south, and the

Pacific Ocean to the west. Ranges of the Andes Mountains

split the country into areas of hot lowlands along the coast,

cooler highlands in the central regions, and tropical low-

lands to the east. Ecuador includes the Galapagos Islands

lying almost 800 miles off the coast. In 2002, the popula-

tion was estimated at 13,183,978. Mestizos compose the

largest ethnic group, making up 55 percent of the popula-

tion. Amerindians make up another 25 percent, Spanish 10

percent, and blacks 10 percent. Almost all practice Roman

Catholicism. In 1533, Spain conquered the indigenous Inca

Empire and ruled Ecuador until 1822, when Simón Bolívar

and José de San Martín drove them out. After indepen-

dence, the region of Ecuador joined with Colombia,

Panama, and Venezuela to form Gran Colombia, but

Ecuador and Venezuela withdrew from the union in 1830.

Oil exports became the cornerstone of the Ecuadorean econ-

omy throughout the industrial age, but since 1982, the

country has faced economic crisis due to declining revenues.

An earthquake in 1987 destroyed a large section of the

country’s major oil pipeline and left 20,000 homeless.

Elected officials, struggling to solve Ecuador’s financial

problems, finally adopted the U.S. dollar as the national cur-

rency in 2000.

There were almost no Ecuadoreans in the United States

prior to World War II (1939–45). After the arrival of sev-

eral thousand in the 1950s, however, a tightening of restric-

tions led to a significant decline. As Ecuador suffered

frequent incursions from more powerful neighbors, eco-

nomic and political instability worsened, leading more

Ecuadoreans to seek opportunities in the United States. Two

events during the mid-1960s powered a great wave of immi-

gration. The Ecuadorean Land Reform, Idle Lands, and Set-

tlement Act of 1964 was designed to aid the poor by

redistributing land to peasant farmers. Uneducated and

untrained in modern agriculture, debt frequently forced

E

them to sell their lands, leaving them without a livelihood.

The desire for economic opportunity coincided with the

passage of the U.S. I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965, which allowed more immigration from Western

Hemispheric nations and led to a steady increase in num-

bers. Almost 37,000 Ecuadoreans came during the 1960s,

50,000 in the 1970s, and 56,000 during the 1980s. Between

1992 and 2002, an average of about 7,200 Ecuadoreans

immigrated to the United States each year.

In the 1950s, a few Ecuadoreans immigrated to Canada

from Azuay Province, whose main industry in the produc-

tion of straw hats had declined dramatically. The first large-

scale migration began, however, in the late 1960s, when

many poor immigrants were attracted by Italian builders

seeking cheap labor. The peak of Ecuadorean immigration

came between 1970 and 1975, when about 20,000 arrived.

Of 10,095 Ecuadorean immigrants in Canada in 2001,

about 4,000 arrived between 1991 and 2001. Most

observers place the actual number of Ecuadoreans in Canada

at two or even three times the official figure of 8,785.

Further Reading

Hanratty, D., ed. Ecuador: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: Fed-

eral Resear

ch Division, Library of Congress, 1991.

Hurtado, Osvaldo. Political Power in Ecuador. Albuquerque: Univer-

sity of New Mexico P

r

ess, 1980.

Kyle, David. Transnational Peasants: Migrations, Networks and Ethnic-

ity in Andean Ecuador. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press, 2000.

M

ata, Fernando. Immigrants from the Hispanic World in Canada:

Demographic Profiles and Social Adaptation. Toronto: [n.a] 1988.

Pooley, E. “Little Ecuador.” New York 18 (S

eptember 16, 1985), p. 32.

Egyptian immigration

Egyptians have never emigrated in large numbers from their

homeland. In the U.S. census of 2000 and the Canadian

census of 2001, 142,832 Americans and 41,310 Canadians

claimed Egyptian descent. The largest concentrations of

Egyptians in the United States are in the New York

metropolitan area (especially Jersey City and Manhattan),

Los Angeles, and Chicago. Quebec was the preferred desti-

nation for most Egyptians during the early phrase of immi-

gration, though by 2001 Toronto and Montreal had equally

large communities.

Egypt occupies 383,900 square miles of the northeast

corner of Africa between 23 and 32 degrees north latitude.

The Mediterranean Sea forms its border to the north; Israel

and the Gaza Strip, to the east; Sudan, to the south; and

Libya, to the west. Egypt is mostly barren excepting the fer-

tile Nile Valley along which most of the population lives. In

2002, the population was estimated at 69,536,644, with

more than 10 million in the capital city of Cairo. More than

90 percent of Egyptians are Muslim, and about 6 percent are

Coptic Christians. Egypt is an ancient nation with archaeo-

logical records of native dynasties dating back to 3200

B

.

C

.

The Persians invaded Egypt in 341

B

.

C

. and were followed

by the Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, and Arabs. The Mam-

luks ruled from 1250 until 1517 when the Ottoman Turks

added Egypt to their empire. Britain assumed administra-

tion of Egypt following Turkish decline and maintained

power until 1952, when Egypt gained its independence fol-

lowing a military uprising. A republic was proclaimed in

1953 and has remained relatively stable. Between 1948 and

1979, Egypt participated in several wars against Israel.

Though Egypt lost the Sinai Peninsula in 1967, it regained

it by negotiation in 1982 and became the first Arab state to

recognize the legitimacy of Israel. In 1991, Egypt gave polit-

ical and military support to Allied forces during the Persian

Gulf War of 1991. Throughout the 1990s and into the 21st

century a strong element of Islamic fundamentalism was

present in Egypt, though the government officially con-

demned it.

Egyptian society has historically migrated little. The

earliest emigrants from Egypt were not Egyptian at all, but

rather Armenian refugees from the Ottoman Empire who

had first settled in Egypt before immigrating to the United

States in the 1920s (see A

RMENIAN

I

MMIGRATION

). Fol-

lowing World War II (1939–45), Egyptians immigrated to

North America mainly for economic and educational

opportunities, though a small number of Copts began to

find their way to the United States. By the 1960s, an increas-

ing number were emigrating for political reasons. Copts and

Jews often felt isolated in an increasingly nationalistic atmo-

sphere, and they occasionally qualified as refugees. Even

when they were not persecuted, they often found few oppor-

tunities in the predominantly Muslim society. After Egypt’s

defeat in the Arab-Israeli War of 1967, a small but steady

exodus began. In the decade after 1967, about 15,000 Egyp-

tians, mainly Copts, came to the United States, including

many scientists and other professionals. As economic power

in the Middle East shifted from Egypt to the Persian Gulf

States in the 1970s, the Egyptian economy declined and

many well-trained Egyptians found themselves without jobs.

Poorer, unskilled labor tended to work in other Middle East-

ern countries, while the better educated, especially if they

were Christian, came to the United States or Canada. Most

settled in the greater New York area, but others began to set-

tle in Washington, D.C., southern California, Illinois, and

Michigan. Between 1992 and 2002, more than 50,000

Egyptians immigrated to the United States.

A few usually well-to-do Egyptian immigrants came to

Canada during the 1950s; however, most between 1956 and

1966 were non-natives. Of the 8,825 immigrants during

that period, 32 percent were Armenians; 15 percent,

Lebanese; 11 percent, Greeks; 6 percent, Jews; and 3 per-

cent, Italians. Between 1967 and 1975, Egyptians were gen-

erally welcomed in Canada because of their high levels of

85EGYPTIAN IMMIGRATION 85

education and training, and about three-quarters chose to

settle in Quebec Province, mostly in Montreal. By the mid-

1970s, however, a greater number of native Egyptians were

more comfortable with English and took advantage of the

jobs produced by the economic growth in Toronto. By the

early 1980s, the annual number of immigrants had declined

from about 900 to about 500. With the introduction of new

provisions in the Canadian immigration code to encourage

investors, Egyptian immigration once again picked up, with

5,455 Egyptians arriving between 1986 and 1991. Of

Canada’s 35,980 immigrants in 2001, 12,295 arrived

between 1991 and 2001.

See also A

RAB IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Awad, Mohammed. E

gyptian with a Million Dollars. Cairo: n.p., n.d.

Brewer, Douglas J., and Emily Teeter. Egypt and the Egyptians. New

Yor

k: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Hagopian, Elaine C., and Ann Paden, eds. The Ar

ab Americans: Stud-

ies in Assimilation. Wilmette, Ill.: Medina University Press Inter-

national, 1969.

Metz, Helen C. Egypt: A Country Study

. Washington, D.C.: Federal

Resear

ch Divison, Library of Congress, 1991.

Orfalea, Gregory. Before the Flames: A Quest for the History of Arab

Americans. Austin: University of

Texas Press, 1988.

Patrick, T. H. Traditional Egyptian Christianity: A History of the Cop-

tic Orthodox Church. St. Cloud, Minn.: North Star Press, 1996.

Sell, R. “International Migration among E

gyptian E

lites: Where

They’ve Been; Where They’re Going.” Journal of Arab Affairs 92

(1990): 147–176.

Watterson, B. Coptic Egypt. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic P

r

ess, 1988.

Ellis Island

The Ellis Island immigration station, located in New York

harbor, was the entry point for three-quarters of American

immigrants between its opening in 1892 and the imple-

mentation of the restrictive J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924.

Between 1892 and its closing in 1954, it was the introduc-

tion to America for more than 12 million immigrants. It

became for most European immigrants a symbol of Ameri-

can opportunity for a better life during an era of almost

unrestricted European immigration. In 1932, the Ellis

Island station stopped receiving steerage-class immigrants

and finally closed in 1954. It was reopened in 1990 as the

National Immigration Museum, part of the Statue of Lib-

erty National Monument.

Beginning in 1855, immigrants were processed through

the C

ASTLE

G

ARDEN

station at the southern tip of Man-

hattan Island. As the volume of immigration increased dra-

matically in the 1870s and 1880s, however, it became clear

that it would no longer be adequate for processing hundreds

of thousands of immigrants each year. Almost 5 million

were processed during the 1880s alone. The problem was

made worse when New York State officials threatened to

close Castle Garden unless the federal government agreed

to fund its operations, which was done in 1882 by levying a

head tax of 50¢ on every immigrant, gradually raised to $8

by 1917. New federal guidelines in 1890 requiring more

extensive physical and mental examinations, combined with

the massive influx of immigrants, finally led the federal gov-

ernment to establish a new immigrant depot, this time on

Ellis Island. While it was being constructed, between 1890

and 1892, immigrants were processed in a wholly inade-

quate federal barge office.

Ellis Island was named for its last private owner, Samuel

Ellis, who purchased it in the 1770s. The site chosen for the

facilities had formerly housed a naval arsenal, Fort Gibson.

The new structure was designed to process up to 5,000 immi-

grants per day. The building of the facilities was accompa-

nied by the creation of a new bureaucracy. In 1891, the office

of superintendent of immigration was created, ending the

uneasy and ill-defined collaboration between the federal gov-

ernment and state boards and commissions, and finally pro-

viding the United States—one century and 16 million

immigrants later—with a formal framework for addressing

immigrant concerns. In a day when immigrants were wel-

comed by politicians and policy makers as cheap labor for

developing the economy, the process at Ellis Island was meant

to help immigrants into the country. Examinations tended to

be brief, unless someone displayed obvious deformities or ill-

ness. Most immigrants passed through the facilities on the day

they arrived, and the rejection rate for most of its history was

about 1 percent. Immigration officials were nevertheless

charged with screening “any convict, lunatic, idiot” or “pau-

pers or persons likely to become a public charge,” the latter

known as the LPC clause. Contract laborers were also pro-

hibited after passage of the A

LIEN

L

ABOR

A

CT

(Foran Act) of

1885, and about 1,000 aliens were denied entrance each year

between 1892 and 1907 on these grounds.

The first structures on Ellis Island were nothing like the

substantial and familiar Main Building—now housing the

National Immigration Museum—that immigrants recall in

their memoirs. Instead, they were all built of Georgia pine

and were opened for business on January 1, 1892. On June

14, 1897, a fire destroyed virtually everything, including

many immigration records dating back to 1855. Before

rebuilding, the government stipulated that the new structures

had to be fireproof. The permanent reception center was

opened in 1900, though it soon proved to be inadequate.

During the first year of operation, in 1892, about

446,000 immigrants landed in New York, but numbers

declined significantly through the 1890s, averaging about

231,000 per year between 1893 and 1899. Much to the sur-

prise of many officials, however, immigration through New

York increased dramatically after 1898. From about 179,000

arrivals in 1898, the immigrant flow peaked in 1906–07,

when almost 1.9 million landed in New York. In 1913–14,

8686 ELLIS ISLAND

another almost 1.8 million immigrants were processed. As a

result, new dormitories, hospitals, kitchens, and other struc-

tures were built or expanded between 1900 and 1915.

When an immigrant ship arrived in New York harbor,

first- and second-class passengers were given a cursory exam-

ination on board and were then transferred to shore. Most

only saw the Ellis Island facilities from a distance or actually

went there if some question had been raised on board. Steer-

age, or third-class, passengers were examined more care-

fully, for they were, in the minds of immigration officials, far

more likely to become public charges. After traveling in

crowded and rank conditions on the bottom decks of

steamships for up to two weeks, immigrants would gather

their belongings to be ferried to Ellis Island. Most immi-

grants were given a cursory medical examination—the “six

second physical,” as it came to be called—and had their

papers checked against shipping manifests. They were then

briefly interviewed, as immigration officials worked from

the ship’s manifest log that contained the answers to 29

questions previously completed by the immigrant. The

whole process typically took three to five hours. Those

admitted typically purchased rail or coastal steamer tickets

to their final destinations and were then ferried to either

Manhattan or the Jersey shore. The small number refused

entry were detained pending an appeal or deportation.

With the massive influx of “new immigrants,” mainly

from southern and eastern Europe (see

NEW IMMIGRA

-

TION

), in the first decade of the 20th century, many Amer-

icans were skeptical about the policy of relatively

unrestricted immigration. Nevertheless, most immigrants

were treated fairly, if perfunctorily, and many officials took a

genuine interest in their welfare. Long before he became

mayor of New York City (1934–45), Fiorello La Guardia

championed the immigrant cause, working as an interpreter

at Ellis Island (1907–10).

After World War I (1914–18), American consulates were

established around the world and were responsible for issuing

visas and checking credentials, thus lessening the work at the

87ELLIS ISLAND 87

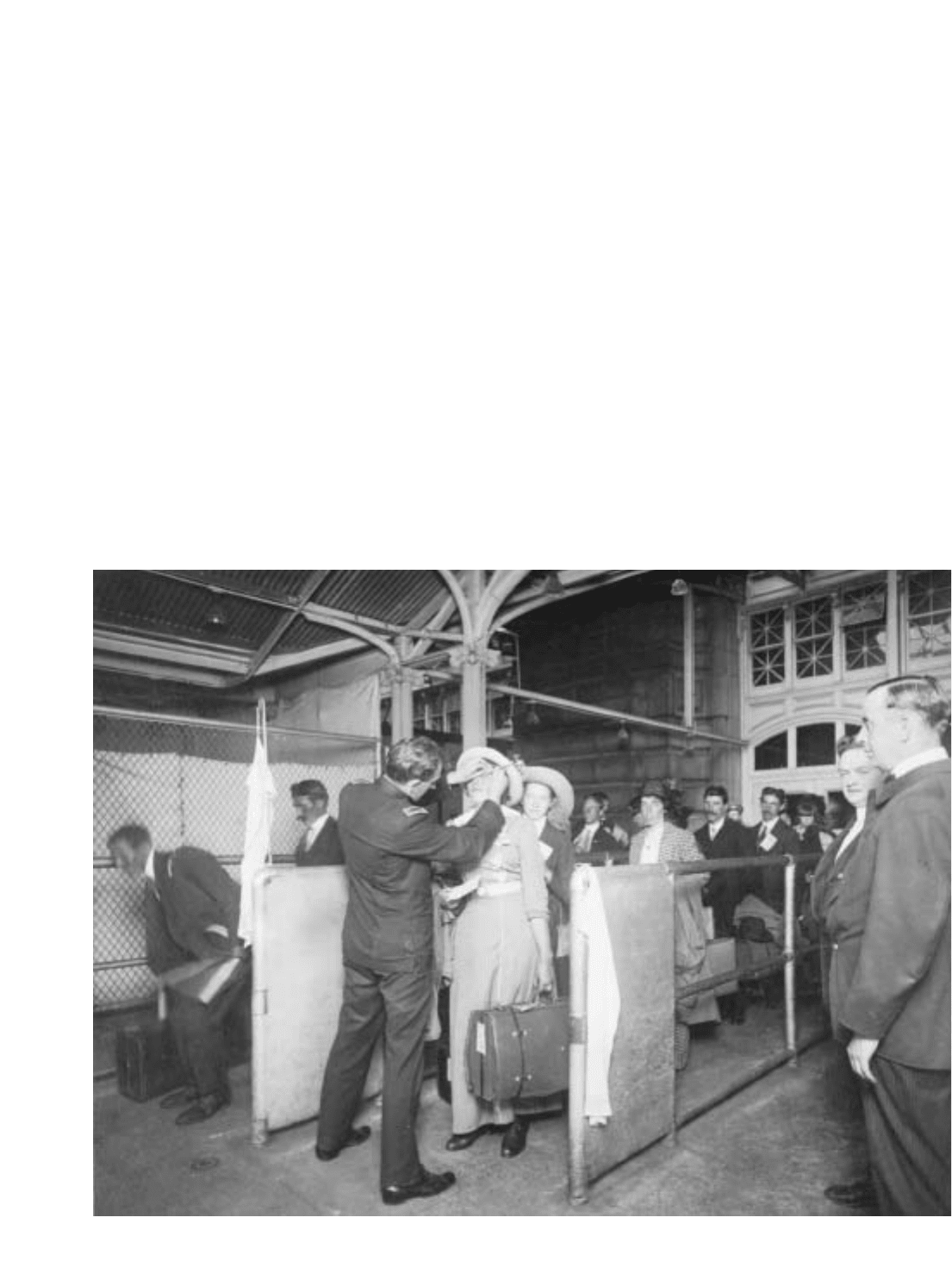

An inspector performs the required eye examination for the highly contagious trachoma at Ellis Island. Rigorous medical

examinations and hygienic regimens were imposed on immigrants in both European and U.S. ports.

(National Archives #090-G-125-12)

port of entry. Passage of the restrictive quota legislation of

1921 and 1924 (see E

MERGENCY

Q

UOTA

A

CT

;J

OHNSON

-

R

EED

A

CT

) also significantly reduced the number of immi-

grants allowed into the United States and marked the

beginning of Ellis Island’s decline as a processing center.

Whereas annual immigration averaged about 740,000

between 1903 and 1914, it dropped to about 152,000

between 1925 and 1930, and 30,000 during the Great

Depression years of the 1930s. By that time, Ellis Island had

become better known for detention than for entry and in

1932, finally stopped receiving steerage-class immigrants.

During World War II (1939–45), the Ellis Island facil-

ities were used to house enemy merchant detainees and as a

training ground for the U.S. C

OAST

G

UARD

. They were

finally closed in 1954. In 1965, the area was incorporated

with the Statue of Liberty National Monument and opened

to the public on a limited basis. After the largest historic

restoration in U.S. history, beginning in 1984 and costing

$160 million, the Main Building was opened to the public

in 1990 as the Ellis Island Immigration Museum. The

museum traces the role that Ellis Island played in the lives of

millions of immigrants, placing it in the context of the

broader patterns of immigration to the United States. A vari-

ety of exhibits, many including personal testimonies in

video and interactive displays, cover more than 40,000

square feet of floor space. Included in the museum’s collec-

tions are oral histories from some 2,000 immigrants, the

result of the Ellis Island Oral History Program, which is

housed there. There is also a research library with special col-

lections on the Statue of Liberty, immigration, ethnic

groups, and Ellis Island itself.

The list of famous Americans who passed through Ellis

Island is long, and includes individuals from every area of

American culture. Here is a small sample:

Country of Origin Immigrants

Austria Felix Frankfurter, Baron von Trapp

E

ngland Bob H

ope, Jule Styne

Hungary Bela Lugosi

Italy Frank Capra, Frank Costello,

Rudolph Valentino

Jamaica Marcus Garvey

Lebanon Kahlil Gibran

Lithuania Al Jolson, Pauline Newman

Norway Knute Rockne

Poland Samuel Goldwyn, Meyer Lansky,

Hyman Rickover

Romania Edward G. Robinson

Russia Irving Berlin, Max Factor,

Isaac Asimov, Mary Antin

Trinidad C. R. L. James

Further Reading

Chermayeff, Ivan, Fred Wasserman, and Mary J. Shapiro. Ellis Island:

A

n Illustrated History of the Immigrant Experience. New York:

Macmillan, 1991.

C

oan, Peter Morton. Ellis I

sland Interviews: In Their Own Words. New

Yor

k: Checkmark Books, 1997.

Houghton, Gillian. Ellis Island: A Primary Source History of an Immi-

gr

ant

’s Arrival in America. New York: Rosen Publishing, 2003.

Kraut, Alan M.

Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the “Immigrant

Menace.

” New York: Basic Books, 1994.

La Guar

dia, Fiorello H. The Making of an Insurgent: An Autobiography,

1882–1919. P

hiladelphia: Lippincott, 1948.

Per

ec, Georges, and Robert Bober. Ellis Island. New York: New Press,

1995.

P

itkin, Thomas. K

eepers of the Gate: A History of Ellis Island. New York:

New

York University Press, 1975.

Yans-McLaughlin, Virginia, and Marjorie Lightman. Ellis Island and

the P

eopling of A

merica. New York: New Press, 1997.

Emergency Quota Act (United States) (1921)

Signed in May 1921, the Emergency Quota Act established

the first ethnic quota system for selective admittance of

immigrants to the United States. With widespread concern

about the importation of communist and other radical polit-

ical ideas, Americans widely supported more restrictive leg-

islation. The measure limited immigration to 357,800

annually from the Eastern Hemisphere; more than half the

quota was reserved for immigrants from northern and west-

ern Europe.

Even as the United States entered World War I in 1917,

there was substantial concern over the “dumping” of dan-

gerous and poor immigrant refugees from Europe. When

the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1917 failed to halt a continuing

flood of hundreds of thousands of Europeans after the war,

support for an ethnic quota grew. Support for immigration

restriction included, for the first time, many within the busi-

ness community, who found that immigrants from Canada,

Mexico, and the West Indies were dramatically lessening

the need for potentially radicalized European labor. In order

to ensure that Bolsheviks, anarchists, Jews, and other “unde-

sirables” were kept to a minimum, the Emergency Quota

Act set the number of immigrants from each national ori-

gin group at 3 percent of the foreign-born population of

that country in 1910. During 1909 and 1910, immigration

from England, Ireland, Scotland and Scandinavia had been

particularly high. About 1 percent of the quota was allotted

to non-Europeans.

Further Reading

Daniels, Roger. Guarding the Golden Door: A

merican Immigration Pol-

icy and Immigrants since 1882. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

Erickson, Charlotte. “S

ome Thoughts on the Social and Economic

Consequences of the Quota Acts.” European Contributions to

A

merican S

tudies 10 (1986): 28–46.

8888 EMERGENCY QUOTA ACT

Hutchinson, E. P. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

LeM

ay

, Michael C. From Open Door to Dutch Door: An Analysis of U.S.

I

mmigration Policy since 1820. New York: Praeger, 1987.

Empire Settlement Act (Canada) (1922)

With the dramatic decline of immigrant admissions and rise

in alien deportations during World War I (1914–18; see

W

ORLD

W

AR

I

AND IMMIGRATION

), the Canadian govern-

ment tried several means of attracting agriculturalists and

domestics. Its first choice of source country was Great Britain.

In 1922, the Canadian and British governments reached an

agreement leading to passage of the Empire Settlement Act

in the British Parliament, a measure encouraging immigration

to Canada of British agriculturalists, farm laborers, domestic

laborers, and children under 17. Inducements varied accord-

ing to specific schemes devised under the measure but

included the sale of land on credit, agricultural training, and

most prominently, establishment of a special transportation

rate for the targeted groups. Numerous amendments and

extensions to the act during the 1920s eventually covered a

number of specialized programs, including the unsuccessful

plan to resettle 10,000 unemployed British miners, giving

them jobs in the Canadian west harvesting wheat. Three-

quarters of the 8,000 who came to Canada eventually

returned. More successful was the program providing trans-

portation assistance and guaranteeing standard wages and

transition support for more than 22,000 domestic workers.

Child immigrants remained in high demand in Canada,

though increased scrutiny by government and humanitarian

groups led to tighter restrictions in 1924. Eventually about

130,000 British immigrants were given assistance under the

measure during the 1920s and 1930s, though Canadian sup-

port faded from the late 1920s on.

Further Reading

Avery, Donald. “Dangerous Foreigners”: European Immigrant Workers

and Labour Radicalism in Canada, 1896–1932. Toronto:

M

cClelland and Stewart, 1979.

Bagnell, Kenneth. The Little Immigrants: The Orphans Who Came to

Canada. Tor

onto: Macmillan, 1980.

Kelley, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

Histor

y of Canadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

Tor

onto Press, 1998.

Schnell, R. L. “The Right Class of Boy: Youth Training Schemes and

Assisted Emigration to Canada under the Empire Settlement Act,

1922–39.” History of Education 24, no. 2 (March 1995): 73–90.

enclosure movement

An economic and social process during the 17th and 18th

centuries that gradually destroyed the old open-field system

of agriculture in Britain. The resulting efficiency led to a sur-

plus of farm laborers increasingly dependent on wages. As

the surplus grew in the late 18th century, agricultural work-

ers from marginalized areas looked to emigration as a means

of economic relief.

As a part of a favorable economic transformation that

laid the foundation for the Industrial Revolution, British

landowners raised productivity by increasing specialization

and by alternating use of arable and grass lands, which in

turn led to greater demand for what had previously been

considered marginal land. In order to improve production

by draining land, hedging fields, and rotating crops, lands

previously used collectively by village farmers were taken

over by large landowners. During the early 18th century this

was done locally by private agreement. By the 1760s, it

became a matter of national legislation. Between 1760 and

1793, 1,611 enclosure acts were passed, favoring larger

landowners and causing much rural distress. The Highlands

of Scotland were particularly hard hit, leading to a large

S

COTTISH IMMIGRATION

to British North America and

later, the United States.

See also B

RITISH IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Neeson, J. M. Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social

Change in England, 1700–1820. R

eprint. Cambridge: Cam-

bridge Univ

ersity Press, 1996.

Thirsk, Joan, ed. Agricultural Change: Policy and Practice 1500–1750.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

English immigration See B

RITISH IMMIGRATION

.

entertainment and immigration

Entertainment in early 19th century North America was cen-

tered in the home. While the upper classes might attend

opera, the theater, and the symphony; the middle class, min-

strel shows or plays; and the working classes, saloon variety

shows, most people were entertained at home by family and

friends, and the development of amateur musical or theatri-

cal talent was considered a mark of social grace. In rural areas

and among the poor, folk music and dances developed.

Immigrants of high artistic achievement usually represented

in their performances the European elite culture routinely

copied in America and Canada, playing in productions of

Shakespeare or in classical symphonies. Popular immigrant

entertainment was usually associated more narrowly with

immigrant folk culture—German church hymns, Irish bal-

lads, and local Ukrainian folk troupes, for example. Prior to

the 20th century, the vast majority of immigrants were either

unskilled or semiskilled laborers or agriculturalists, who

wished to fondly remember their homelands in their enter-

tainments. Sometimes these nostalgic longings developed

89ENTERTAINMENT AND IMMIGRATION 89

into rich performance communities in the large cities,

including an extensive repertoire of Yiddish-language adap-

tations of both classics of the stage and melodrama. Though

most ethnic performers never joined the mainstream English

stage, they nevertheless served large audiences. The first

phase of immigrant entertainment then was self-consciously

fashioned by performers for their own ethnic groups and

had little impact on society at large. Immigrants themselves

were scarcely included in the songs and plays of the main-

stream culture, and when they were, it was usually as a

stereotype, such as the drunken Irishman or the Jewish shy-

lock. It usually took immigrants many years to acquire an

understanding of American art forms; once they did, how-

ever, they played a powerful role in defining the cultural

landscape.

Two closely related developments in the entertainment

industry at the end of the 19th century opened doors for

many immigrants. The rapid growth of cities during the

Industrial Revolution, particularly after 1880, led to the cre-

ation of a variety of venues that were an extension of the

British music hall and designed specifically for mass popular

entertainment, thus marking the beginnings of American

vaudeville. In the 1890s, the music publishing industry was

transformed by the deliberate search for composers and lyri-

cists to supply the new mass market. Tin Pan Alley, the col-

lective name given to the New York music publishing

district, was constantly searching for clever lyrics and great

tunes and was willing to take on anyone who could write to

meet a popular style. Together, vaudeville and Tin Pan Alley

ushered in a new age of mass entertainment.

Perhaps the most representative talent of the period was

singing star Sophie Tucker, born to a Russian-Jewish woman

in Poland in 1884. She came to the United States as an

infant and grew up in Connecticut. At the age of 10, Tucker

was singing in the family café. In the first decade of the new

century, she was performing blackface, before joining the

Ziegfeld Follies in 1909. Billed as the “Last of the Red-Hot

Mamas,” she starred on Broadway and on film. As vaudeville

faded in the 1930s, she continued to pack nightclubs and

performed on radio and television. She was one of the first

recording stars, when primitive Edison cylinders were being

used, and produced albums into the 1950s. An even bigger

star, Al Jolson was billed during the first half of the 20th cen-

tury as “The World’s Greatest Entertainer.” Born Asa Yoel-

son in Lithuanian Russia in 1886, Jolson came to America

with his Jewish family in 1894. Attracted to the latest rag-

time craze, he became deeply immersed in American popu-

lar culture. He sang in the circus, performed on the comedy

stage, developed a comedy act, and began to perform in

blackface. He debuted on Broadway in 1911. Around 1918,

he began writing lyrics. With The Jazz Singer in 1927, he

helped usher in the era of talking films; in it, he sang “B

lue

9090 ENTERTAINMENT AND IMMIGRATION

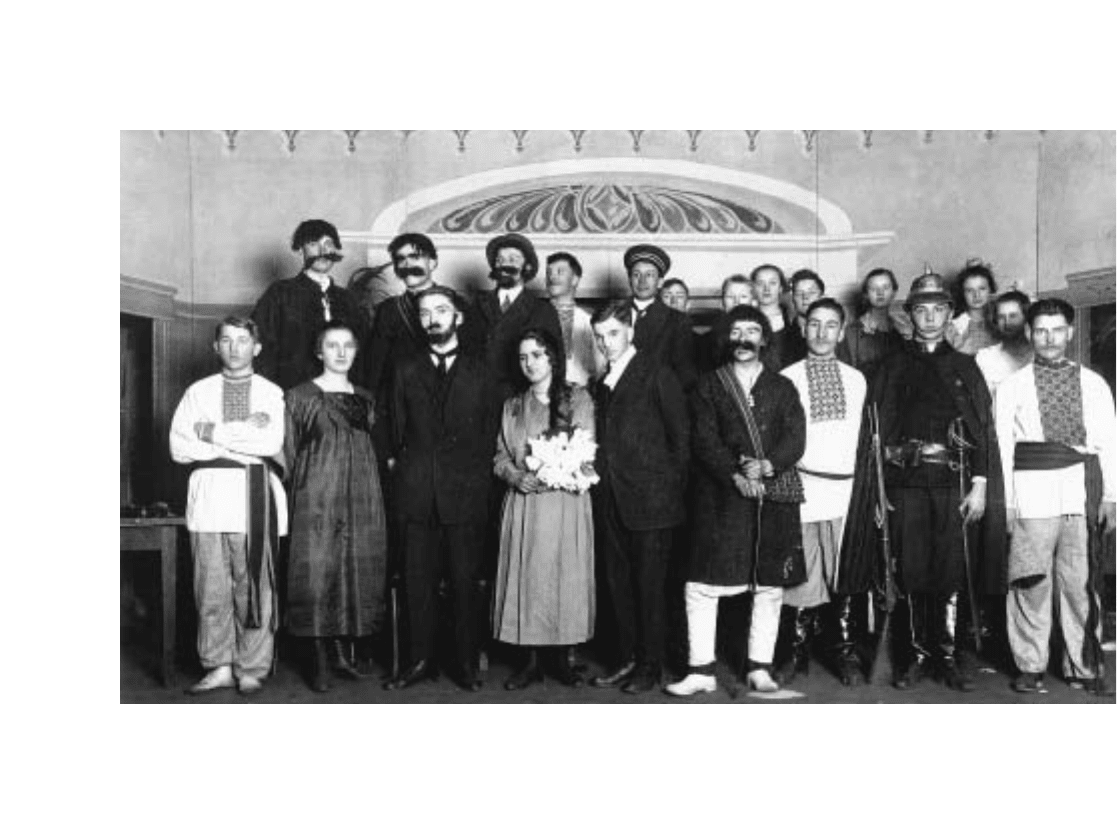

P. Mohyla Ukrainian Institute Drama Group, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, 1919. Ethnic drama troupes like this were common in

Canada and the United States, helping to maintain ethnic identity and solidarity.

(George E. Dragan Collection/National Archives of

Canada/PA-088603)

Skies,” the tune of another Russian immigrant, Irving

Berlin. Though the vaudevillian style was waning in the

1930s, Jolson made the transition to radio, became wildly

popular entertaining U.S. troops, and continued to enter-

tain until his death in 1950.

The entertainment industry enabled immigrants both

to transcend their ethnic backgrounds and to help transform

the perception of immigrants. Tucker was famous for her

trademark song “My Yiddishe Momme.” Others, such as

George M. Cohan and Chauncey Olcott, of Irish descent,

did much to dispel stereotypes with songs like “Yankee Doo-

dle Dandy,” “You Can’t Deny You’re Irish,” and “When Irish

Eyes Are Smiling.” America’s best-loved popular composer

of the first half of the 20th century, Irving Berlin, was pro-

lific, writing more than 900 songs for Tin Pan Alley, the

vaudeville stage, film, and Broadway musicals. Born Israel

Baline in czarist Russia in 1888, he composed dozens of clas-

sic American songs, including “God Bless America,” “White

Christmas,” “Easter Parade,” and symbolically, “There’s No

Business Like Show Business.”

From the early days of the film industry, immigrants

found a niche for their talents and capital. Jews were among

the first movie theater owners, and most of the early Holly-

wood studios were either started or controlled by Jewish

immigrant businessmen, including Samuel Goldwyn (born

in Poland), Harry Warner (born in Poland), and Carl

Laemmle (born in Germany). Italian-born Frank Capra

became one of America’s best-loved film directors, promot-

ing mainstream American ideals in movies such as Mr.

S

mith G

oes to Washington (1939) and It’s a Wonderful Life

(1947). Charlie Chaplin, born in England, was considered

by many to be America’s great comic genius of the early 20th

century

. E

lia Kazan, born Elia Kazanjoglou in Constantino-

ple, directed some of the most culturally searching films and

plays of the century, including On the Waterfront (1953) and

East of Eden (1954).

I

n the 1950s and early 1960s, the enter

tainment indus-

try was conscious of ethnicity and frequently embraced it.

Cuban Desi Arnaz was integral to the success of the beloved

I Love Lucy television program, and the music of crooners

such as F

rank S

inatra, Tony Bennett, and Dean Martin—

the latter the son of an Italian barber—was freely laced with

the sentiments of old Italy. As immigration became more

global with the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of

1965, improved transportation and communications

opened the United States and Canada to international

trends in entertainment, reinforcing areas already started by

immigrants. Though Arnaz and others had helped popular-

ize Cuban music in the 1950s, an interest in a wider world

music began to develop, with explorations of the instru-

ments and rhythms of India, Brazil, and Africa. The popu-

lar music of the British Invasion of the mid-1960s,

spearheaded by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, was

deeply rooted in American folk and ethnic music, especially

blues and jazz, as well as songs from the old Tin Pan Alley

tradition. Ironically, the segregationist mindset of the Amer-

ican entertainment industry was finally changed, in part,

with the help of English and Irish musicians who enthusias-

tically embraced the music of black America and brought it

back to the land of its roots.

From the 1970s, the entertainment industry in North

America was internationalized by visitors from abroad and

immigrants from within. Improvements in transportation

and communication enabled filmmakers, actors, comedians,

musicians, and other performers to tap the richest enter-

tainment market in the world. The flood of immigrants

from non-European countries following the relaxation of

immigration restrictions during the 1960s and 1970s cre-

ated new audiences for all forms of international entertain-

ment. European, Indian, Iranian, Chinese, and Japanese

filmmakers worked more frequently in the United States

and began to have their films more widely viewed in North

America. Non-English-language films were seldom unqual-

ified commercial successes, but they developed dedicated

followings, particularly in major urban centers, and were

regularly reviewed by critics. Some directors, such as Tai-

wan’s Ang Lee, studied in the United States and stayed to

do much of their work there. Lee’s master’s project, Fine

L

ine, was full of immigrant themes, with an I

talian man flee-

ing the Mafia and a Chinese woman hiding fr

om immigra-

tion officials. Opportunities for classical musicians and

dancers continued to attract many foreign artists to the large

cultural centers of the United States, including New York,

Boston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The 1961 defection

of Rudolph Nureyev, Russia’s leading dancer, on grounds of

artistic freedom brought international attention to the cul-

tural implications of the

COLD WAR

.

A wide variety of world music forms were brought to

North America, the “music capital” of the world, for sales

and exposure. British groups remained the most popular

non-American acts, as Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Elton

John, the Bee Gees, and others regularly toured the United

States and Canada. Occasionally Australian (Men at Work,

Kylie Minogue), Swedish (ABBA), Irish (U-2), and other

European performers would enjoy popularity, but no other

country consistently produced successful rock and pop

music in North America as did Great Britain. Latin music,

well known to jazz musicians before World War II

(1939–45), became more broadly popular in the 1950s and

1960s, as hundreds of thousands of Cuban refugees immi-

grated to the United States between 1957 and 1981 and

Mexico emerged as the number-one source country for

American immigration. With millions of North Americans

whose first language was Spanish, a specialized Latino music

scene developed, with various local forms. Tejano, for

instance, combining country and Mexican traditions,

became wildly popular among Chicanos in the Southwest,

before Texas singer Selena took it into the mainstream with

91ENTERTAINMENT AND IMMIGRATION 91

hits in the 1990s. Gloria Estefan, born in Havana, had pre-

viously done the same for Cuban salsa, taking her band, the

Miami Sound Machine, from Spanish-language dance clubs

to the top of the U.S. pop charts in the late 1980s. During

the 1970s and 1980s, Spain’s Julio Iglesias became the lead-

ing Latin singer in the world and hugely successful in North

America. A new generation of Latino artists continued to

successfully fuse Latin and pop idioms into the 21st century,

including Ricky Martin (Puerto Rican), Enrique Iglesias

(Spanish, Julio’s son), and Shakira (Colombian-Lebanese),

among others, Some immigrants, such as Carlos Santana,

entered the rock mainstream directly. Santana had his own

blues-rock band in the 1960s and 1970s, then reemerged in

the 1990s to play with a host of new stars.

Not all world music was equally popular. The Indian

sitar music of Ravi Shankar became fashionably stylish in

the 1960s and 1970s without being commercially successful.

The francophone musical tradition in Canada remained

highly regionalized, with the exception of the phenomenal

crossover appeal of Celine Dion in the 1990s. Reggae, on

the other hand, brought from Jamaica and popularized by

Bob Marley, was embraced by North American audiences

to become part of the musical mainstream. In 2002, Sean

Paul’s dancehall reggae united reggae and modern hip hop,

whose raps were influenced by the ska and rock-steady pre-

cursors to reggae in the 1960s. African musicians became

popular in the 1990s when Paul Simon featured a South

African backup band, and the Dave Matthews Band of

South Africa became one of the most popular acts of the

decade. Most often, however, these innovators were only

temporary migrants in the United States and Canada,

recording music in New York City; Chicago, Illinois; Mus-

cle Shoals, Alabama; or Nashville, Tennessee, or touring to

promote their work.

Some entertainers, however, stayed to become perma-

nent residents or citizens, preferring to be close to their

biggest market or seeking to evade political turmoil or the

high tax rates common in Europe. The Russian classical

composer Igor Stravinsky moved to the United States in

order to teach at Harvard for one year but ended settling in

West Hollywood and becoming a citizen in 1945. British-

born John Lennon of Beatles fame waged a long battle with

the U.S. government in order to win his green card in 1973.

Many stage and film stars, including Ingrid Bergman (Swe-

den), Richard Burton (Wales), and Arnold Schwarzenegger

(Austria) came to work in the United States, then chose to

remain.

See also

SPORTS AND IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Bona, Mary Jo, and Anthony Julian Tamburri, eds. Through the Look-

ing Glass: I

talian and Italian-American Images in the Media.

Staten Island, N.Y.: American Italian Historical Association,

1994.

Er

dman, H

arley. Staging the Jew: The Performance of American Ethnic-

ity

. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1962.

Friedman, Lester D., ed. U

nspeakable Images: Ethnicity and the Amer-

ican Cinema. C

hicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

J

ones, Dorothy R. The Portrayal of China and India on the American

Screen, 1896–1955:

The Evolution of Chinese and Indian Themes,

Locales, and Characters as Portrayed on the American Screen. Cam-

bridge, M

ass.: Center for I

nternational Studies, MIT, 1955.

Kanellos, Nicolás. Hispanic Theater in the United States. Houston: Arte

Público P

r

ess, 1984.

———. A H

istory of Hispanic Theatre in the United States: Origins to

1940. A

ustin: University of Texas Press, 1990.

Maloney

, Paul. Scotland and the Music Hall, 1850–1914. Manchester,

U.K.: Manchester U

niversity Press, 2003.

Marchetti, Gina. Romance and the “Yellow Peril”: Race, Sex and Dis-

cursiv

e S

trategies in Hollywood Fiction. Berkeley: University of

California Pr

ess, 1993.

Marcuson, Lewis R. The Stage Immigrant: The Irish, Italians, and Jews

in A

merican Dr

ama, 1920–1960. New York: Garland, 1990.

Naficy, H. The M

aking of Exile C

ultures: Iranian Television in Los Ange-

les. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Par

enti, Michael. “The Media Are the Mafia: Italian-American Images

and the Ethnic Struggle.” National R

eview 30, no. 10 (1979):

20–27.

Rogin, Michael. B

lackface, White Noise: J

ewish I

mmigrants in the Hol-

lywood Melting Pot. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1996.

Seller, M

axine Schwar

tz, ed. Ethnic Theatre in the U

nited States. West-

port, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1983.

Shaheen, J. The TV Arab: Our Popular P

r

ess. Bowling Green, Ohio:

Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1984.

Slobin, Mark. Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of the Jewish Immi-

grants. Urbana: University of Illinois Pr

ess, 1982.

Torres, Sasha, ed. Living Color: Race and Television in the United States.

Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1988.

Whitcomb

, I

an. Irving Berlin and Ragtime America. New York: Cen-

tury

, 1987.

Estonian immigration

Estonian immigration to North America has been small and

closely tied to political events in Europe. In the U.S. census

of 2000 and the Canadian census of 2001, 25,034 Ameri-

cans and 22,085 Canadians claimed Estonian descent. Early

settlement in the United States included in New York City,

San Francisco, and Astoria, Oregon. In 2000, most Estoni-

ans in the United States lived in the Northeast, with a sig-

nificant number also in California. Toronto was the center

of Estonian settlement in Canada.

Estonia occupies 17,400 square miles of eastern Europe

along the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Finland between 57 and

59 degrees north latitude. Russia lies to the east and Latvia to

the south. In 2002, the population was estimated at

1,423,316, 65 percent of which are ethnic Estonians. Rus-

sians made up another 28 percent of the population. Chief

religions of the country were Evangelical Lutheranism and

9292 ESTONIAN IMMIGRATION

Russian Orthodox. Prior to World War I (1914–18) Estonia

was a province of the Russian Empire. As such, it is impossi-

ble to determine how many Estonians immigrated prior to

1922 because they were almost universally referred to as Rus-

sians, representing the country of their birth. A few Estoni-

ans were among the Swedish party that settled the colony of

New Sweden along the Delaware River during the 17th cen-

tury (see D

ELAWARE COLONY

), and small groups settled near

Pierre, South Dakota; New York City; and San Francisco

after 1894. It was not until the failed socialist Revolution of

1905, however, that the first large group of Estonians came

to the United States, many of them committed Socialists.

With the independence of Estonia in 1920 and passage of

the restrictive E

MERGENCY

Q

UOTA

A

CT

(1921) and J

OHN

-

SON

-R

EED

A

CT

(1924), Estonian immigration declined sig-

nificantly. Estonia was conquered by the Soviet Union in

1940 and incorporated as a Soviet Socialist Republic, driving

thousands of refugees into displaced persons camps in Ger-

many after World War II (1939–45). Between 1946 and

1955 more than 15,000 were accepted in the United States

as refugees. Under Soviet rule, Estonians generally were not

allowed to emigrate, but upon gaining their independence

in 1991, it became more common. Between 1992 and 2002,

about 2,500 Estonians immigrated to the United States.

Only a handful of Estonians, mainly individuals and a

few families, settled in Canada prior to World War II. The

earliest Estonians were probably fishermen working out of

Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Between 1899 and 1903,

there were 16 Estonian farms near Sylvan Lake (modern

Alberta). By 1916, there were about 1,500 Estonians in

Canada. Only 700 immigrated during the 1920s and 1930s,

including members of a failed settlement near St. Francis,

British Columbia. After World War II, Canada admitted

about 14,000 Estonian refugees, most between 1947 and

1951, and often after they had first made stops in Sweden or

Germany. Of 6,395 Estonians in Canada in 2001, almost 80

percent arrived prior to 1961; only 845 immigrated between

1991 and 2001. Most Estonians who immigrated to the

United States and Canada as refugees were well educated and

staunchly anticommunist and tended to assimilate quickly.

See also R

USSIAN IMMIGRATION

; S

OVIET IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Aun, Karl. The Political Refugees: A History of the Estonians in Canada.

Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1985.

K

urlents, Alfr

ed, ed. Eestlased Kanadas (Estonians in Canada). Vol. 2.

Tor

onto: Kanada Eestlaste Ajaloo Komisjon, 1985.

Larr, Mart. War in the Woods: Estonia’s Struggle for Survival,

1944–1956. Trans. Tiina Ets. New York: Compass Press, 1992.

P

ennar, Jaan, et al., eds. The Estonians in America, 1627–1975: A

Chronolog

y and Factbook. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana Publica-

tions, 1975.

Raun, T

oiv

o U. Estonia and Estonians. 2d ed. Stanford, Calif.: Hoover

Institution Pr

ess, 2002.

Tannberg, Keresti, and Tonu Parming. Aspects of Cultural Life: Sources

for the S

tudy of E

stonians in America. New York: Estonian Learned

Society in America, 1975.

W

alko, M. Ann. R

ejecting the Second Generation Hypothesis: Main-

taining Estonian E

thnicity in Lakewood, New Jersey. New York:

AMS Pr

ess, 1989.

Ethiopian immigration

Ethiopians were among the first Africans to voluntarily

immigrate to the United States, mainly as a result of

COLD

WAR

conflicts. In the U.S. census of 2000 and the Cana-

dian census of 2001, 86,918 Americans and 15,725 Cana-

dians claimed Ethiopian descent. Main concentrations of

settlement included Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, New

York City, and Dallas, Texas. About half of all Ethiopian

Canadians lived in Toronto.

Ethiopia occupies 431,800 square miles of East Africa

between 4 and 17 degrees north latitude. It is bordered by

the Red Sea and Eritrea to the north; Somalia and Djibouti,

to the east; Kenya, to the south; and Sudan, to the west. A

high-altitude plateau dominates the eastern portion of the

land, while the mountains of the Great Rift Valley cover the

west. In 2002, the population was estimated at 65,891,874

and was divided into two major ethnic groups and a number

of smaller ones. The Oromo made up 40 percent of the pop-

ulation, and Amhara and Tigrean another 32 percent.

Nearly 50 percent of Ethiopians were Muslim; 40 percent,

Ethiopian Orthodox; and 12 percent, animists. Ethiopia

wielded regional dominance in the medieval period. In 1880

Ethiopia was invaded by Italy but remarkably managed to

maintain its independence during the colonial era of the

19th and early 20th centuries, excepting the northern

93ETHIOPIAN IMMIGRATION 93

An Estonian family near Jewett City, Connecticut, 1942. A

failed revolution in Russia in 1905 led to the first major wave

of Estonian immigration to the United States.

(Photo by John

Collier/Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USF34-

083824-C])