Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

coastal province of Eritrea, which became an Italian protec-

torate in 1889. Italy successfully conquered the country’s

heartland in 1935. Freed by Britain in 1941, Ethiopia was

ruled by Haile Selassie I until 1974, when he was ousted by

a military junta. In 1977, Ethiopia began to cooperate with

Communist Russia and Cuba, countries that helped

Ethiopia defeat invading Somalian troops in 1978. In 1984,

a severe famine killed nearly 1 million people. Both the

political unrest and famine led to widespread immigration.

There is no record of formal Ethiopian immigration to

the United States prior to 1980, though some were admitted

as students prior to that time. The R

EFUGEE

A

CT

of that year

established a formal procedure for admitting African

refugees. Ethiopians formed the largest group between 1982

and 1994, about 68 percent of the African total. Between

1976 and 1994, more than 33,000 Ethiopian refugees were

resettled in the United States, often after spending time in

Sudanese camps. In 1993, Eritrea declared independence

from Ethiopia, and a war ensued until 2000 when the

province won its independence. The war cost Ethiopia nearly

$3 billion and displaced approximately 350,000 Ethiopians.

Multiparty elections for a federal republic were first held in

1995, following a coup by the Ethiopian People’s Revolu-

tionary Democratic Front. Between 1992 and 2002, annual

Ethiopian immigration to the United States averaged about

5,000. Between 1983 and 2001, more than 31,000

Ethiopian refugees were admitted to the United States.

Prior to the political turmoil of the 1970s, only a handful

of Ethiopian students resided in Canada. With the refugee cri-

sis of the 1980s, Canada began to screen and admit a num-

ber of Ethiopians, mostly those who spoke English and came

from middle- and upper-class families. Many came from

countries of first asylum, including Kenya, Italy, Egypt, and

Greece. Toronto was the number-one destination as it pro-

vided the greatest job opportunities. Of 13,710 Ethiopian

immigrants in 2001, fewer than 600 had arrived prior to

1981, and more than 8,100, between 1991 and 2001.

Further Reading

Chichon, D., E. M. Gozdziak, and J. G. Grover, eds. The Economic

and Social Adjustment of N

on-Southeast Asian Refugees. Dover,

N.H.: Research Management Corporation, 1986.

K

oehn, P. H. Refugees from Revolution: U.S. Policy and Third World

M

igr

ation. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1991.

Moussa, Helene. Storm and S

anctuary: The Journey of Ethiopian and

E

ritrean Women Refugees. Dundas, Ontario: Artemis Enterprises,

1993.

Ofcansky, Thomas P

., and LaV

erle Berry. Ethiopia: A Country Study

.

Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1993.

Sor

enson, John. “Politics of Social Identity: Ethiopians in Canada.”

Jour

nal of Ethnic Studies 19, no

. 1 (1991): 67–86.

Woldemikael, T. M. “Ethiopians and Eritreans.” In Refugees in Amer-

ica in the 1990s: A Refer

ence Handbook. Ed. D. W. Haines. West-

port, Conn.: Gr

eenwood Press, 1996.

ethnicity and race See

RACIAL AND ETHNIC

CATEGORIES

;

RACISM

.

Evian Conference

Sponsored by the United States, the Evian Conference

brought 30 nations together in Evian, France, to discuss the

plight of European refugees during summer 1938.

In 1937, recognizing the worsening condition of Jews

in Europe, President Franklin Roosevelt relaxed screening

rules for refugees. At the same time, the American public

was strongly opposed to an increased Jewish presence in the

country, with one poll suggesting that 82 percent were

against the entry of large numbers of Jewish refugees. Roo-

sevelt invited 32 nations to attend the largely ineffectual

conference. Just as the United States public was unwilling to

take the lead in relocating Jewish refugees, all other countries

shrank from taking aggressive action. During the 1930s,

Canada had been especially marked by international policy

makers as a large country with available land for resettling

overcrowded and mistreated populations, from the Japanese

to the Jews. The Canadian government under W

ILLIAM

L

YON

M

ACKENZIE

K

ING

thus attended reluctantly, fearing

that Canada’s appearance would suggest a readiness to accept

more Jewish refugees. Canadians generally were isolationists,

and Quebecois especially were opposed to both interna-

tional involvements of every kind and resettlement of Jews

in particular. All countries at the conference eventually

agreed with the Canadian view that “governments with

unwanted minorities must equally not be encouraged to

think that harsh treatment at home is the key that will open

the doors to immigration abroad.” The conference did lead

to establishment of the Intergovernmental Committee on

Refugees, but lack of funds and international support ham-

pered its work. Adolf Hitler, the Nazi leader of Germany,

interpreted the results as confirmation that the Jews had lit-

tle international support.

Further Reading

Abella, Irving, and Harold Troper. None Is Too Many: Canada and the

Jews of E

urope, 1933–1948. Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys,

1982.

B

r

eitman, Richard, and Alan M. Kraut. American Refugee Policy and

Eur

opean Jewry, 1933–1945. Bloomington: Indiana University

Pr

ess, 1987.

Feingold, Henry L. The Politics of Rescue: The Roosevelt Administration

and the H

olocaust, 1938–1945. D

etroit: Wayne State University

Pr

ess, 1973.

Stewart, Barbara McDonald. United States Government Policy on

Refugees from N

azism, 1933–1940. N

ew York: Garland Publish-

ing, 1982.

9494 ETHNICITY AND RACE

95

4

Fairclough, Ellen Louks (1905–2004) politician

Ellen Louks Fairclough, Canada’s first woman federal cabi-

net minister, presided over a major overhaul of the coun-

try’s longstanding “white Canada” immigration policy.

Regulations implemented on February 1, 1962, eliminated

almost all elements of race-related exclusion and led to a

significant increase in immigration from Africa, the Middle

East, and Latin America, most notably from the West Indies

(see W

EST

I

NDIAN IMMIGRATION

).

Born in Hamilton, Ontario, Ellen Louks became a

chartered accountant. During the 1930s she helped her hus-

band, businessman D. H. Gordon Fairclough, to organize

the Young Conservative Association of Hamilton. She

served as a city alderman (1946–49) and deputy mayor

(1950) before winning a seat in the House of Commons in

1950. When John Diefenbaker became prime minister in

1957, he named Fairclough secretary of state and in the fol-

lowing year appointed her to the newly created post of min-

ister of citizenship and immigration. Upon taking up the

post in May 1958, she was immediately confronted with the

press of applicants for sponsored immigration and a growing

backlog in applications. The Conservative government

sought to limit the extent of family sponsorship, then

backed down. As Fairclough explained, she rescinded the

restrictive Order in Council 1959–310 because it was based

on previous legislation enacted by the Liberals, and she was

therefore willing to reconsider the government’s position in

anticipation of more extensive revisions. These revisions

were finally implemented in the immigration regulations of

1962, which established skills, rather than race, as the basis

for Canadian immigration. The new regulations also made

the General Board of Immigration Appeals largely indepen-

dent of the Department of Citizenship and Immigration.

In 1962, Fairclough was made postmaster general but was

defeated in the election of 1963, at which time she retired

from politics. She died on November 13, 2004.

Further Reading

Conrad, Margaret. “‘Not a Feminist, but...’: the Political Career of

Ellen Louks Fairclough, Canada’s First Feminine Federal Cabinet

Minister.” Journal of Canadian Studies 31, no. 2 (Summer 1996):

5–28.

Fairclough, Ellen Louks. Saturday’s Child: Memoirs of Canada’s First

Female Cabinet Minister. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,

1995

Hawkins, Freda. Canada and Immigration: Public Policy and Public

Concern. 2d ed. Kingston and Montreal: Institute of Public

Administration of Canada and McGill–Queen’s University Press,

1988.

Newman, Peter Charles. Renegade in Power: The Diefenbaker Years.

Indianapolis, Ind.: Bobbs-Merrill, 1964.

Federation for American Immigration

Reform

See

NATIVISM

.

Fiancées Act See W

AR

B

RIDES

A

CT

.

F

Fijian immigration See S

OUTH

A

SIAN

I

MMIGRATION

.

Filipino immigration

Because the United States had acquired the Philippines as a

colonial territory in 1898, Filipinos were in some ways priv-

ileged immigrants during the 20th century and second in

number only to Chinese among Asian immigrants to the

United States. They were third in Canada, behind Chinese

and East Indian immigrants. In the U.S. census of 2000 and

the Canadian census of 2001, 2,364,815 Americans and

327,550 Canadians claimed Filipino descent. The largest

concentrations of Filipinos in the United States are in Cali-

fornia, Hawaii, and Chicago, Illinois, with significant areas

of settlement in cities with large naval bases, including San

Diego, California; Bremerton, Washington; Jacksonville,

Florida; and Charleston, South Carolina. More than half of

Filipino Canadians live in Ontario, with a large settlement

also in Vancouver, British Columbia.

The Philippines is a country of 7,100 islands occupying

115,000 square miles in the South China and Philippine Seas

between 5 and 19 degrees north latitude. Nearby countries

include Taiwan to the north and Malaysia and Indonesia to

the south. Most of the population, an estimated 82,841,518,

resides on 11 major mountainous islands that take up the

greatest part of the country’s land area. About 83 percent of

the population practices Roman Catholicism; 9 percent,

Protestantism; and 5 percent, Islam. Malay peoples indige-

nously inhabited the Philippine Islands when Magellan

landed there with his Spanish fleet in 1521. Spain governed

the islands until 1898, when they were ceded to the United

States following the Spanish-American War. A nationalist

uprising broke out the following year but was successfully

suppressed by U.S. forces by 1905. From 1941 to the end of

World War II in 1945, the islands were occupied by Japan.

In 1946, the Philippines was granted independence, and a

republican government was formed. Between 1972 and 1981,

President Ferdinand Marcos (first elected in 1965) ruled the

country by martial law. Marcos was deposed in 1986, leading

to significant political destabilizing under President Corazon

Aquino. Between the 1965 election of Marcos and his 1986

overthrow, some 300,000 Filipinos immigrated to the United

States. Communist and Muslim insurgents launched a coup

9696 FIJIAN IMMIGRATION

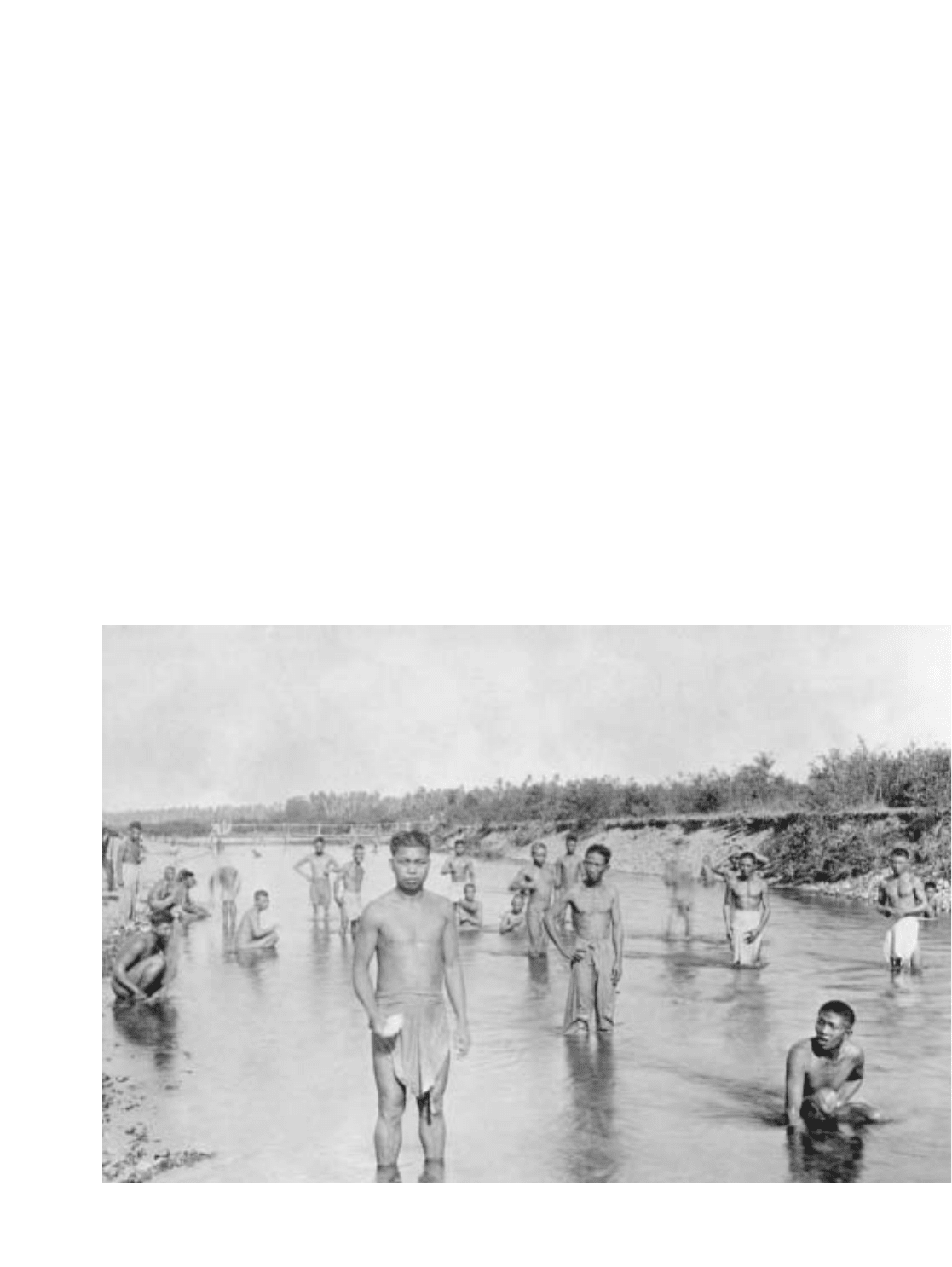

Prisoners taken by the United States during the Filipino insurrection, 1898–1902. By 1930, there were more than 63,000 Filipinos

in Hawaii, having largely replaced Chinese, Japanese, and Korean workers banned from entry into the United States.

(National

Archives #72-91212)

in 1989 that was defeated with help from the United States. A

Muslim region in the south was eventually granted auton-

omy in 1996, ending the ongoing rebellion.

Some of the earliest Filipino immigrants to North

America were sailors who left their ships in New Orleans,

Louisiana, during the 19th century. The number of immi-

grants remained small, however, until the first decade of the

20th century. With provisions of the C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

(1882) and the G

ENTLEMEN

’

S

A

GREEMENT

(1907)

largely excluding Chinese, Japanese, and Korean laborers,

there was high demand for cheap agricultural labor in

Hawaii and California. In 1906, the Hawaiian Sugar

Planters’ Association began to actively recruit in the Philip-

pines, and by the mid-1920s, there was a large voluntary

workforce seeking admission. By 1931, 113,000 Filipino

workers had come to Hawaii. About 39,000 eventually

returned to the Philippines, but more than 18,000 eventu-

ally migrated to California. In addition to these, some

27,000 Filipinos immigrated directly to the mainland, most

hired under the

PADRONE SYSTEM

of labor supply. Most Fil-

ipino immigrants were young men, and as late as 1940, the

ratio of Filipino men to women was still 3.5 to 1. With the

rise in unemployment during the depression, the T

YDINGS

-

M

C

D

UFFIE

A

CT

of 1934 limited Filipino immigration to 50

per year. As important, with the Philippines being made a

commonwealth and destined for independence, Filipinos

were reclassified from nationals to aliens.

A second period of immigration, particularly associ-

ated with military developments, occurred between 1946

and 1964. Filipino Americans had served with distinction

during World War II, helping substantially in driving the

Japanese from the Philippines. The W

AR

B

RIDES

A

CT

of

1946 enabled American soldiers to bring some 5,000 Filip-

ina brides to the United States following World War II. The

Military Bases Agreement of 1947 permitted the United

States to make use of 23 sites in the Philippines and thus to

maintain a formidable presence there into the 1990s.

Exemptions to the Tydings-McDuffie Act enabled the

United States to recruit more than 22,000 Filipinos into

the navy (between 1944 and 1973), most of whom were

assigned to work in mess halls or as personal servants.

Exemptions also enabled some 7,000 additional Filipino

agricultural workers into the country.

A new phase of immigration began with the I

MMIGRA

-

TION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965, which both elimi-

nated race as a factor in the selection process and classified

immediate relatives of U.S. citizens as special immigrants,

thus admitted outside the annual quota of 20,000. The sig-

nificant family reunification numbers were augmented in

1974 when the Philippines instituted an ongoing overseas

employment program. This led to an average of more than

600,000 Filipino workers migrating each year, though most

of these went to the countries of the Middle East and East

Asia. A large percentage of those immigrating to the United

States were highly trained professionals, especially doctors

and nurses. Emigration to Canada remained small in part

because Canadian immigration policy encouraged migration

only of professional and skilled workers.

As in most developing countries, worker migration was

seen as beneficial in both easing unemployment and increas-

ing remittances to the Philippines. In 1995, for instance,

remittances totaled $4.87 billion, or about 2.5 percent of

the gross national product, and the amounts remained high

into the first decade of the 21st century. Between 1991 and

2002, more than 600,000 Filipinos immigrated to the

United States.

It is difficult to arrive at precise figures for Filipino

immigration to Canada. Not only were Filipinos grouped

under the category “Other Asians” until 1967, but they also

followed a distinctive pattern of immigration with no prece-

dents in the Chinese, Japanese, or Asian Indian communi-

ties. There were virtually no immigrants prior to World War

II, and fewer than 100 by 1964. Beginning in 1965, however,

a steady immigration began, which was accelerated by the

new

IMMIGRATION REGULATIONS

of 1967, which included

a points system that gave preference to skilled workers in

high demand areas, such as health care. Between 1971 and

1992, total immigration from the Philippines placed them in

the top 10 of source countries, and between 1994 and 2002,

the country ranked from second to sixth each year, with a

total of about 110,000 immigrants. Unlike other Asian

groups, most Filipino immigrants were women who came for

job opportunities in medical fields, especially nursing, and

clerical areas. Although the gender differential gradually

became more balanced, by the 1990s Filipina women still

composed about 60 percent of the immigrant population.

Another difference between Filipino and other Asian

immigration is that most early immigrants came first from

the United States, where their relationship afforded special

opportunities for access to the country. Sometimes unable to

remain in the United States, they learned that visas were

available for skilled technicians in Canada, particularly in

Ontario. By the early 1970s, they were bringing family

members and encouraging others to emigrate directly from

the Philippines. As Canadian immigration policy in the

1980s gave special weight to family reunification, more Fil-

ipinos took advantage of the provisions. During the 1980s

and 1990s, Filipino immigrants were less likely to choose

Toronto, though it remained the foremost Filipino com-

munity in Canada with a population of 140,000 in 2001.

Vancouver’s was second, with more than 60,000. Of

232,670 Filipino immigrants in Canada in 2001, about 96

percent arrived after 1970.

See also B

ULOSAN

, C

ARLOS

.

Further Reading

Brands, H. W. Bound to Empire:

The United States and the Philippines.

New York: Oxford U

niversity Press, 1992.

97FILIPINO IMMIGRATION 97

Cariaga, Roman R. The Filipinos in Hawaii: Economic and Social Con-

ditions, 1906–1936. San Francisco: R. and E. Research Associ-

ates, 1974.

Carino, B

enjamin. “F

ilipino Americans: Many and Varied.” In Origins

and Destinies: I

mmigration, Race, and Ethnicity in America. Eds.

Silvia P

edraza and Rubén G. Rumbaut. Belmont, Calif.:

Wadsworth, 1996.

Cheng, Lucie, and Edna Bonacich, eds. Labor Immigration under Cap-

italism: A

sian

Workers in the United States before World War II.

Ber

keley: University of California Press, 1984.

C

usipag, Ruben J., and Maria Corazon Buenafe. Portrait of Filipino

Canadians in O

ntario, 1960–1990. Ontario, 1993.

Espina, Maria E.

Filipinos in Louisiana. New Orleans, La.: A. F.

Laborde and S

ons, 1988.

Espiritu, Yen Le. Filipino American Lives. Philadelphia: Temple Uni-

v

ersity P

ress, 1995.

Guyotte, Roland L. “Generation Gap: Filipinos, Filipino Americans,

and Americans, Here and There, Then and Now.” Journal of

A

merican E

thnic History 17 (Fall 1997): 64–70.

Laquian, Eleanor M. A Study of F

ilipino I

mmigration to Canada,

1962–1972. Ottawa: United Council of Filipino Associations in

Canada, 1973.

Lasker, B

r

uno. Filipino Immigration to the Continental United States

and to H

awaii. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931.

Mangiafico, Luciano. Contemporary American I

mmigr

ants: Patterns of

Filipino, Korean, and Chinese Settlement in the United States. New

York: Praeger, 1988.

Melendy, H. B

r

ett. “Filipinos in the United States.” Pacific Historical

Review 43, no. 4 (1974): 520–547.

Pido, Antonio J. A. The Filipinos in America: Macro/Micro Dimen-

sions of I

mmigration and Integration. Staten Island, N.Y.: Center

for M

igration Studies, 1992.

Ramos, Rodel J. In Search of a Future:

The S

truggle of Immigrants. Scar-

borough, Canada: RJRAMOS Enterprises, 1994.

Root, Maria P. P., ed. Filipino Americans: Transformation and Identity.

Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1997.

S

an Juan, Epifanio, et al. From Exile to Diaspora: Versions of the Filipino

Experience in the U

nited States. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press,

1998.

T

eodor

e, Luis V., Jr., ed. Out of This Struggle: The Filipinos in Hawaii.

Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1981.

Toff, Nancy, ed. The Filipino Americans. New York: Chelsea House,

1989.

Finnish immigration

Finns were among the earliest settlers in North America,

forming a substantial portion of the colony of New Swe-

den, founded in 1638 along the Delaware River (see

D

ELAWARE COLONY

). In the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 623,573 Americans and

114,690 Canadians claimed Finnish descent. Finns were

widely dispersed throughout the northern tier of the

United States, with Michigan and Minnesota having the

largest numbers. More than half of Canadian Finns live in

Ontario.

Finland occupies 117,800 square mile of Scandinavian

Europe between 60 and 70 degrees north latitude along the

Gulf of Bothnia and the Gulf of Finland. Norway borders

Finland to the north, Russia to the east, and Sweden to the

west. The southern and central regions of the country are

relatively flat, with many lakes. Northern regions are moun-

tainous. In 2002, the population was estimated at

5,175,783. Ethnic Finns make up 93 percent of the people,

while Swedes compose another 6 percent. About 89 percent

of the population claims Evangelical Lutheranism as their

religion. Eurasians first settled Finland, but Sweden con-

trolled the territory from 1154 until 1809, when it became

an independent grand duchy of Russia. Throughout the

19th century, Finland was granted extraordinary freedoms

of self-government and religion and exemption from Rus-

sian military service. Pan-Slavic policies during the first

decade of the 20th century, however, spurred a rise in

nationalism that led to a declaration of independence in

1917. Finland was first recognized as a republic in 1919,

after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the creation of

the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union took control of large

amounts of Finnish territory in 1939 and even more

throughout World War II (1939–45). Following the war,

however, a treaty of mutual assistance was signed (1948),

enabling Finland to develop largely outside the

COLD WAR

conflicts so prevalent in other parts of Europe. A new treaty

was signed in 1992, and in 1995 Finland became a member

of the European Union.

Finns were among the colonists who established New

Sweden along the Delaware River in 1638. As the colony

successively changed hands, however, first going to the

Dutch and then the English, by the 18th century, Finns

had blended into the predominant British culture. In

Alaska, Finns and Russians settled in the 1840s and 1850s,

especially around Sitka. Perhaps 500 moved to British

Columbia and California when Alaska was purchased by the

United States in 1867, finding work in mines or on the rail-

roads. The number of Finnish immigrants remained small

until the 1860s, when widespread economic depression led

to massive emigration, particularly from northern Finland.

Most of the immigrants had taken part in the Laestadian

religious revival of the 1860s, and their migration was char-

acterized by families hoping to maintain a separatist lifestyle.

Finland was also experiencing unprecedented population

growth, tripling during the 19th century and creating a large

surplus population for which there were few jobs and no

land. From the 1890s, the majority of immigrants were

young and from the more populated south, motivated by

both economic opportunity and, after 1904, opposition to

Czar Nicholas II’s newly imposed nationalistic policies and

forced military service. A high percentage of Finns had

become politically radicalized prior to leaving Europe and

often became involved with socialist or anarchist politics

upon their arrival. It has been estimated that some 300,000

9898 FINNISH IMMIGRATION

Finns settled permanently in the United States between

1864 and 1924. The actual number of immigrants was

higher, but there was an unusually high rate of return among

Finnish radicals. In the 1920s and early 1930s, 10,000

immigrated to the Soviet Union, although thousands of

ordinary Finns seeking a better life still sought permission to

immigrate to the United States. When passage of the restric-

tive J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

in 1924 drastically cut the

Finnish quota, Finns increasingly turned their attention to

Canada.

While a few hundred Finns migrated to British

Columbia when Alaska was purchased, others were just

beginning to seek economic opportunities outside Finland

and Sweden. Immigration figures prior to World War I

(1914–18) are unreliable, as they were frequently classified

or grouped in various combinations with Swedes, Norwe-

gians, Russians, or, in the case of continental migration,

Americans. Perhaps 5,000 Finns immigrated during the

19th century, and another 20,000 between 1900 and 1914.

With the application of restrictive legislation in the United

States, more than 36,000 Finns flocked to Canada between

1921 and 1930, before they, too, were shut out by Canada’s

depression-era policies in the 1930s. Undoubtedly many of

these Finnish immigrants used Canada as a backdoor to the

United States, but thousands stayed to settle. Many who did

were active in socialist politics, founding radical newspapers

and helping to organize the Lumber Workers Industrial

Union of Canada in northern Ontario. Disheartened by

slow progress and the onset of the depression, thousands left

Canada during the 1930s, most for Finland, but many too

for neighboring Soviet Karelia.

The Russian invasion of Finland in 1939 prompted a

new wave of sympathy for the Finns and a new era of

Finnish immigration. Between 1948 and 1960, more than

17,000 immigrated to Canada, many fearing renewed Soviet

aggression. During the later 20th century, immigration to

both the United States and Canada was small, composed

mainly of students and professionals seeking educational or

economic advancement. Between 1992 and 2002, an aver-

age of fewer than 600 immigrated to North America, with

about five-sixths of them coming to the United States.

Because Finns tended to immigrate individually, rather than

communally, they became largely indistinguishable from the

greater society, just as had been the case in the colonial

period.

Further Reading

Dahlie, Jorgen, and Tissa Fernando, eds. Ethnicity,

Power and Politics

in Canada. Toronto: Methuen, 1981.

Engle, E. F

inns in North America. Annapolis, Md.: Leeward, 1975.

Hammasti, P. G. Finnish Radicals in Astoria, Or

egon, 1904–1940. N

ew

York: Arno, 1979.

H

oglund, A. W. Finnish Immigrants in America, 1880–1920. Madi-

son: University of Wisconsin P

ress, 1960.

Jalkanen, R. J., ed. The F

inns in North America: A Social Symposium.

East Lansing: M

ichigan State University Press for Suomi College,

1969.

Karni, M. G., ed. Finnish Diaspor

a. 2 vols. Toronto: Multicultural His-

tory Society of Ontario, 1981.

Kerkkonen, M. “Finland and Colonial America.” In Old Friends—

Str

ong T

ies. Eds. V. Niitemaa et al. Turku, Finland: Institute for

M

igration, 1976.

Kero, Reino Migration from Finland to North America in the Years

betw

een the U

nited States Civil War and the First World War.

Turku, Finland: Turun Yliopisto, 1974.

Kivisto, P

. I

mmigrant Socialists in the United States: The Case of Finns

and the Left. Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University

P

r

ess, 1984.

Kolehmainen, J. I. From Lake Erie’s Shores to the Mahoning and Mono-

g

a

hela Valleys: A History of the Finns in Ohio, Western Pennsylva-

nia, and West Virginia. Painsville: Ohio Finnish-American

H

istorical S

ociety, 1977.

Kolehmainen, J. I., and G. W. Hill. Haven in the Woods: The Story of

the Finns in

W

isconsin. Madison: State Historical Society of Wis-

consin, 1951.

Lindström-B

est, Varpu. Defiant Sisters: A Social History of Finnish

Immigr

a

nt Women in Canada. 2d ed. Toronto: Multicultural His-

tor

y Society of Ontario, 1992.

———. The Finns in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Associa-

tion, 1985.

Ross, C., and K. M. Wargelin Brown, eds. Women Who Dared: The

History of F

innish A

merican Women. St. Paul: Immigration His-

tory

Research Center, University of Minnesota, 1986.

Virtanen, Keijo. Settlement and Return: Finnish Emigr

ants

(1860–1930) in the I

nternational Overseas Return Migration

Movement. Helsinki, Finland: Migration Institute, 1979.

Wasatjerna, H. R., ed. History of the Finns in Minnesota. Trans. T.

R

osvoll. Duluth, Minn.: Finnish-American Historical Society,

1957.

Foran Act See A

LIEN

C

ONTRACT

L

ABOR

A

CT

.

Fourteenth Amendment (United States) (1868)

Proposed in 1865 and ratified in 1868, the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the U

nited States

defined citizenship to include former slaves and to protect

them from violations of their civil rights. Aimed at state

abuses against African Americans in the wake of the Civil

War (1861–65), it also provided equal protection to natu-

ralized immigrants.

Section One of the amendment stated that “all persons

born or naturalized in the United States . . . are citizens of

the United States” and that the government may not

deprive them of “life, liberty, or property, without due pro-

cess of law,” or deny them “equal protection” before the

law. The “due process” clause was later interpreted by the

courts to extend to state as well as federal law; and the

99FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT 99

“equal protection” clause, to such categories as sex and dis-

ability, as well as race. Other sections of the amendment

eliminated the three-fifths compromise, by which only 60

percent of the slave population was counted for purposes

of state representation in the House of Representatives;

prohibited the holding of public office by anyone who had

sworn an oath to the government and then rebelled; voided

debts incurred in support of rebellion; and gave Congress

the authority to pass enforcing legislation.

Fourteenth Amendment protections extended specifi-

cally to immigrants in many ways, especially as courts began

to interpret its clauses more broadly in the 20th century.

Segregation of housing by race was, in part, invalidated on

Fourteenth Amendment grounds. The Supreme Court

referred to it in G

RAHAM V

. R

ICHARDSON

(1971) in estab-

lishing that “alienage,” like race, was inherently suspect as a

category before the law. Also, when the state of Texas refused

to finance the education of illegal alien children, the

Supreme Court ruled in P

LYLER V

.D

OE

(1982) that the

Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to citizens alone, but

under the equal protection clause to all people “within the

jurisdiction” of the state.

Further Reading

Abraham, Henry J., and Barbara A. Perry. Freedom and the Court:

Civil Rights and L

iberties in the United States. 8th ed. St.

Lawrence: U

niversity of Kansas Press, 2003.

Benedict, Michael Les. A Compr

omise of Principle: Congressional

R

epublicans and Reconstruction, 1863–1869. New York: W. W.

Norton, 1974.

Cox, J

ohn H. Politics, Principle, and Prejudice: Dilemma of Recon-

struction America, 1865–66. New York: Free Press, 1963.

Foner

, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s U

nfinished Revolution,

1863–1877. New York: HarperCollins, 1988.

Hyman, H

arold M., and William Wiecek. Equal Justice Under Law:

Constitutional Dev

elopment, 1835–1875. New York: Harper and

Row, 1982.

French colonization See N

EW

F

RANCE

.

French immigration

As one of the founding nations of colonial Canada, the

French helped define the political and cultural character of

the modern country. In the Canadian census of 2001,

4,710,580 Canadians—almost 16 percent of the total pop-

ulation—claimed French or Acadian origins (see A

CADIA

),

second only to those claiming English descent. The true

number was undoubtedly considerably higher, however, as

almost 12 million respondents claimed “Canadian” descent,

and almost 100,000, “Quebecois.” In the U.S. census of

2000, 10,659,592 Americans claimed either French or

French-Canadian descent. Although French Americans were

largely assimilated, there were significant concentrations in

the counties of Worcester and Middlesex, in Massachusetts,

and in Providence, Rhode Island. Rural concentrations were

highest in L

OUISIANA

parishes, among descendants of the

Acadian refugees. French settlement in Canada was concen-

trated in the province of Q

UEBEC

, where French culture was

maintained and a large degree of autonomy preserved in

the face of expanding British influence. Almost 90 percent

of Canadians who mainly speak French live in Quebec.

France occupies 210,400 square mile in western

Europe, between the Atlantic Ocean, and Mediterranean

Sea. Spain lies to the southwest; Italy, Switzerland, and Ger-

many to the east, Luxembourg and Belgium to the north. In

2002, the population was estimated at 59,551,227. During

the Middle Ages a strong French national identity emerged

from a variety of Celtic, Latin, Teutonic, and Slavic influ-

ences. As one of the great imperial powers from the 16th

century, France gained control of colonial territories in

North America, the Caribbean, South America, Africa,

India, and Southeast Asia. Although France failed to estab-

lish any substantial settlement colonies outside of North

America, in the wake of decolonization after 1945, millions

of inhabitants of former colonial territories became French

citizens, changing the demographic character of the nation.

By 2000, 82 percent of the population was Roman Catholic,

and 7 percent, Muslim, the latter mostly from the former

French colonies of Algeria and Morocco. France allied itself

with the fledgling United States of America during the rev-

olution against Britain and generally maintained cordial

relations with the United States throughout the 20th cen-

tury, though differences over relations with the Middle East

increasingly strained Franco-American relations during the

later 20th and early 21st century. Although traditionally

hostile to Great Britain in foreign affairs during the 18th

and 19th centuries, France and Britain were allies during the

two world wars and partners in both the North Atlantic

Treaty Organization and the European Union.

French explorer J

ACQUES

C

ARTIER

claimed Acadia and

the St. Lawrence Seaway in the 1530s, but the bitter win-

ters restricted French interest to fishing along coastal waters.

S

AMUEL DE

C

HAMPLAIN

established the first permanent

French settlement in North America at Quebec (1608),

where only eight of the original 24 French settlers survived

the first winter. In 1627, Champlain became head of the

C

OMPAGNIE DE LA

N

OUVELLE

F

RANCE

, which was granted

title to all French lands and a monopoly on all economic

activity except fishing, in return for settling 4,000 French

Catholics in Canada. Although the fur trade flourished, the

French were little interested in farming settlements. Within

New France, there were three areas of settlement: Acadia, the

mainland and island areas along the Atlantic coast;

Louisiana, the lands drained by the Mississippi, Missouri,

and Ohio river valleys; and Canada, the lands on either side

of the St. Lawrence Seaway and just north of the Great

100100 FRENCH COLONIZATION

Lakes. Among these, only Canada, with the important set-

tlements of Quebec and Montreal, developed a significant

population.

A harsh climate and continual threats from the British

and the Iroquois, made it difficult for private companies to

attract settlers to Canada. In 1663, Louis XIV (r.

1648–1713) made New France a royal colony but was only

moderately successful at enticing colonists. Revocation of

the Edict of Nantes (1685), which had provided freedom of

worship, drove 15,000 Protestant French Huguenots to

British North America, many of whom were wealthy or

skilled artisans. Most settled in New York, though important

settlements were also founded in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and

South Carolina. During the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

(1756–63),

6,000 French speakers in present-day Nova Scotia, New

Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island were exiled to Britain’s

southern colonies and to Louisiana, then still in the hands of

France. There, they became the largest French-speaking

enclave in the United States, the Cajuns. Canada’s remain-

ing French population of some 70,000 was brought under

control of the British Crown, which organized the most

populous areas as the colony of Quebec. During the entire

period of French control, only about 9,000 French settlers

actually immigrated to New France.

In general, the French did not immigrate in great num-

bers compared with other Europeans. When they did immi-

grate, it tended to be to the United States and as individuals

rather than as groups. During the French Revolution

(1789–99) some 10,000 political refugees escaped to the

United States, many by way of French colonies in the

Caribbean. That number included some 3,000 African

French Creoles who established themselves in Philadelphia.

A record number of French immigrants came as a result of

the C

ALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH

, including about 30,000

between 1849 and 1851.

French immigration during the late 19th and early 20th

centuries was sporadic and often related to political events

and economic crises. One peak period was 1871–80, when

more than 72,000 arrived. Some were refugees from the

failed Paris commune of 1870. Many immigrated from

Alsace and Lorraine in the wake of the transfer of the region

to Germany after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71).

Many others came as France faced economic depression

beginning in 1872. A second peak came in the first decade

of the 20th century, when more than 73,000 arrived, many

seeking economic opportunities. Still, given its size and pop-

ulation, France’s contribution to the greatest decade of

immigration seems small, measuring only 0.8 percent of

the 8.8 million immigrants to arrive in the United States

between 1901 and 1910. During the 1930s, French immi-

gration declined dramatically, with only about 1,200 com-

ing per year. After World War II (1939–45), rates of

immigration remained low and declined significantly after

the initial years of hardship immediately following the war.

Between 1941 and 1960, about 90,000 French citizens

immigrated to the United States; between 1961 and 1980,

about 70,000; and between 1981 and 2000 about 65,000.

Between 1992 and 2002, French immigration averaged

about 3,000 annually. On the whole, the French do not have

a strong tradition of emigration; those who did immigrate to

the United States tended to eschew ethnic identification and

to assimilate relatively quickly.

Despite the fact that French immigration to Canada

almost totally ceased after the Seven Years’ War, as late as

the first census in 1871, the French composed 32 percent

of the Canadian population, and 40 years later, in 1911, 26

percent. French immigrants were still favored throughout

the 20th century, along with British and Americans,

although it was difficult to get French citizens to come. In

some cases, French Canadians were actually leaving. Dur-

ing the 1860s, the difficulty in acquiring land under the old

French seigneurial land system led thousands of young

French Canadians to migrate to New England, where they

frequently worked in industry or the building trades, usually

with the intention of returning. Most, however, ended up

staying in the United States.

During the early 20th century, few French immigrated

to Canada—only about 35,000 between 1900 and 1944.

In 1921, the French-born population was about 19,000 and

continued to decline until the late 1940s.

The Canadian I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1952 once again

placed the French in the most-favored category for immi-

gration, with all “citizens of France born in France or in

Saint-Pierre and Miquelon Islands” eligible for admission so

long as they had means of support or employment. This,

coupled with two converging trends between 1945 and the

mid-1970s, promoted an increase in immigration. The

postwar slump during the late 1940s and early 1950s led

thousands of French to apply for Canadian visas. Also,

around 1960 political leaders in Quebec began to see

French immigration as a means of reversing the decline of

francophone citizens, as their birthrates fell and more

Anglophones began to enter Quebec. As a result, a number

of agreements reached with the Canadian federal govern-

ment enabled them to launch initiatives to attract French

immigrants. Almost 90,000 came to Canada—most to

Quebec—between 1945 and 1970, but their numbers

declined thereafter. Of some 70,000 French immigrants in

Canada in 2001, about 44,000 came after 1970, and the

French-Canadian percentage of the population continued

to decline to 16 percent.

Further Reading

Allain, M., and G. Conrad, eds. France and North America. 3 vols.

Lafay

ette: University of Southwestern Louisiana Press,

1973–87.

Brasseaux, Carl A. Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a People,

1803–1877. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1992.

101FRENCH IMMIGRATION 101

102

———. The “Foreign French”: Nineteenth-Century French Immigration

into Louisiana. 2 vols. Lafayette: University of Southwestern

Louisiana, 1990, 1992.

———. T

he F

ounding of New Acadia: The Beginnings of Acadian Life

in Louisiana, 1765–1803. B

aton Rouge: Louisiana State Univer-

sity Pr

ess, 1987.

Brault, Gerard J. The F

rench-Canadian Heritage in New England.

H

anover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1986.

Cr

eaghy, R. Nos cousins d’Amérique: Histoire des Français aux Etats-

Unis. Paris: P

ayot, 1988.

D

oty, C. Stewart. The First Franco-Americans: New England Life His-

tories from the F

ederal Writers’ Project, 1938–1939. Orono: Uni-

versity of M

aine at Orono Press, 1985.

Ekberg, Carl J. French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi

F

r

ontier in Colonial Times. Urbana: University of Illinois Press,

1998.

H

oude, J

ean-Louis. French Migration to North America, 1600–1900.

Chicago: Editions Houde, 1994.

Louder, D

ean, and Eric Waddell. French America: Mobility, Identity,

and Minority Experience acr

oss the Continent. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana S

tate University Press, 1983.

Martel, Marcel. French Canada: An Account of Its Creation and Break-

Up, 1850–1967. Ottawa: Canadian H

istorical Association,

1998.

———. Le deuil d’un pays imaginé. Rêves, lutes et déroute du C

anada

français. Les rapports entre le Q

uébec et la francophonie canadienne

(1867–1975). Ottawa: Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa, CRCCF,

1997.

Pula, James S. The French in America, 1488–1974: A Chronology and

Fact Book. Dobbs F

erry, N.Y.: Oceana, 1975.

Quintal, C. The Little Canadas of New England. Worcester, Mass.:

Fr

ench Institute, Assumption College, 1983.

Ramirez, Bruno. On the M

ove: French-Canadian and Italian Migrants

in the N

orth Atlantic Economy, 1860–1914. Toronto: McClelland

and Ste

wart, 1991.

Roby, Yves. Les F

ranco Américains de la Nouvelle-Angleterre,

1776–1930. S

illery, Quebec: Éditions du Septentrion, 1990.

Silv

er, Arthur. The French-Canadian Idea of Confederation:

1864–1900. 2d ed. Toronto, 1997.

W

eil, F

rançois. “French Migration to the Americas in the Nineteenth

and Twentieth Centuries as a Historical Problem.” Study Emi-

gr

azione 33, no

. 123 (1996): 443–460.

———. Les Franco-Americains. Paris: Belin, 1989.

Z

oltv

any, Y. F. The French Tradition in America. New York: Harper and

Ro

w, 1969.

French and Indian War See S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

.

102 FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR

Gentlemen’s Agreement

The Gentlemen’s Agreement was an informal set of execu-

tive arrangements between the United States and Japan in

1907–08 that defused a hostile standoff over the results of

Japanese labor migration to California. President Theodore

Roosevelt persuaded the San Francisco school board to

rescind an order segregating Chinese, Japanese, and Korean

students in return for a promise to halt the flow of Japanese

laborers into the United States.

Japan’s emergence as an important East Asian power fol-

lowing the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) heightened ten-

sions between the United States and Japan. In the wake of

the war, Japanese immigration to the United States

exploded, reaching up to 1,000 a month by 1906. Japan also

posed a potential threat to the Philippines, an American

colony since 1898. Tensions were to some extent alleviated

with the signing of the Taft-Katsura Agreement (1905), by

which Japan agreed not to invade the Philippines in return

for recognition of Japanese supremacy in Korea. In the same

year, however, both houses of the California legislature

urged their Washington, D.C., delegation to propose formal

limitations on Japanese immigration. The crime and uncer-

tainty following the San Francisco earthquake in April 1906

led to increased hostility toward Japanese immigrants. The

mayor and the Asiatic Exclusion League, with almost

80,000 members, pressured the San Francisco school board

to pass a measure segregating Japanese students (October

11). The resolution not only violated Japan’s most-favored

nation status but deeply offended the Japanese nation and

led to talk of war between the two countries.

Not wishing local affairs to undermine international

policy, Roosevelt sought a diplomatic solution. In his annual

address, on December 4, he repudiated the school board’s

decision and praised Japan. Between December 1906 and

January 1908, three separate but related agreements were

reached that addressed both Japanese concerns over the wel-

fare of the immigrants and California concerns over the

growing numbers of Japanese laborers. In February 1907,

immigration legislation was amended to halt the flow of

Japanese laborers from Hawaii, Canada, or Mexico, which

in turn led the San Francisco school board to rescind (March

13) its segregation resolution. In discussions of December

1907, the Japanese government agreed to restrict passports

for travel to the continental United States to nonlaborers,

former residents, or the family members of Japanese immi-

grants. This allowed for the continued migration of laborers

to Hawaii and for access to the United States by travelers,

merchants, students, and

PICTURE BRIDES

. Japanese foreign

minister Tadasu Hayashi agreed to the terms of the discus-

sions in January 1908. With the dramatic decline in the

numbers of Japanese laborers, Filipinos were increasingly

recruited to take their place. To demonstrate that America’s

East Asian policy was not made from a position of weakness,

Roosevelt followed the Gentlemen’s Agreement with a world

tour of 16 American battleships, with a symbolic stop in

Japan.

103

4

G