Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the American colonies by the desperate economic condi-

tion of their homeland.

During the 18th century, Ireland grew more rapidly

than any European country, with the population of the

island increasing from 3 million in the 1720s to more than

8 million by the early 1840s. The exploding Irish popula-

tion—which grew by 1.4 million between 1821 and 1841

alone—coincided with the fall of agricultural prices and the

decline of the textile industry at the end of the Napoleonic

Wars (1815), throwing hundreds of thousands out of work,

with little prospect for economic improvement. The situa-

tion was made worse by the Irish land system, dominated by

Protestant landlords, with most of the cottiers (tenant farm-

ers with very small holdings) and laborers being Irish. Those

most hurt economically were the larger tenant farmers, both

Protestant and Catholic, who were often unable to pay rents

and evicted from their lands, then entered an already

depressed workforce. Rather than replace evicted farmers,

landlords—often absentee in England—shifted to sheep and

cattle raising as a more economically viable activity for the

poor land. Also, with no system of primogeniture guaran-

teeing the eldest son the whole land inheritance, Irish farms

were quickly divided among large families, with plots soon

becoming too small to support a family. A series of potato

famines further heightened the distress, adding starvation to

destitution as compelling factors toward immigration.

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the poorest

laborers and cottiers tended to stay in Ireland or to immi-

grate to Britain, where industrialization was rapidly opening

job opportunities. Protestants, generally better off finan-

cially than their Catholic neighbors, found it easier to immi-

grate to the New World, especially to the colonies of what

would later become the United States. They had the added

incentive of escaping rural violence then common, as

Catholic secret societies attempted to undermine the Protes-

tant Ascendancy.

Most Irish immigrants arrived in ports along the eastern

seaboard of North America, including Halifax, Nova Sco-

tia; Montreal, Quebec; Boston; Philadelphia; and New York.

Most landed first at Canadian ports, as transportation rates

there were considerably cheaper. Many then migrated south-

ward, often after a number of years. Most immigrants stayed

in the cities, but a significant number ventured into the

Appalachian backcountry of Pennsylvania, South Carolina,

and Georgia. By 1800, the Irish population of Philadelphia

was 6,000, the largest in America. Most were Presbyterians,

but there were Quakers and Episcopalians as well and an

increasing number of Catholics by the turn of the century.

The Irish were the largest non-English immigrant group in

the colonial era, numbering perhaps 400,000 by 1790 (see

B

RITISH IMMIGRATION

). Between 1820 and 1840, the char-

acter of Irish immigration began to change, with a greater

percentage of poor Irish Catholics among them. During this

period, more than one-third of all immigrants to the United

States were Irish, most by way of Canada. By the 1840s,

however, they usually came directly to Boston or New York

City.

Although fewer Irish stayed in Canada, between 1770

and 1830, they transformed the character of the maritime

colonies. N

EWFOUNDLAND

, once thought of only as a

“colony built around a fishery,” was the first area of sub-

stantial Irish settlement. By the late 18th century, more and

more sojourning fishermen were choosing to settle perma-

nently on the island, despite a formal British ban. By the

1830s, when declining trade virtually ended Irish immigra-

tion, half of Newfoundland’s population was Irish (38,000).

As Newfoundland’s transatlantic economy suffered after

1815, more Irish Catholics chose to settle in N

OVA

S

COTIA

or N

EW

B

RUNSWICK

. Though Irish Catholics remained a

small minority on Cape Breton Island, by 1837 they consti-

tuted more than one-third of the population of Halifax,

and almost a third of the population of the entire colony.

Between 1827 and 1835, it is estimated that 65,000 Irish

immigrated to New Brunswick, attracted both by the fish-

eries and the rich farmland. Most were from the Irish

provinces of Munster and Ulster, and perhaps 60 percent

were Catholic. The Irish formed the largest immigrant

group in Canada during the first half of the 19th century,

more than the English, Scottish, and Welsh combined.

The Great Famine of 1845–49 dramatically accelerated

an already-growing trend. The Irish peasantry had since the

18th century relied largely on the potato for their basic food

supply. In the 1840s, an average male might eat 14 pounds

of potatoes each day. Pigs, the primary source of meat in

the Irish diet, were also fed potatoes. When potato blight

destroyed a large percentage of the potato crops in 1845,

1846, and 1848, the laboring population had few choices. A

million or more may have died as a result of the famine;

another million chose to emigrate. In the 1820s, 54,000

Irish immigrants came to America; in the 1840s, 781,000.

The immigrant wave peaked in the 1850s when 914,000

Irish immigrants arrived, most coming through New York

Harbor. With friends or family already in the United States

and British North America, the decision to emigrate became

easier. Between 1845 and 1860, about 1.7 million Irish set-

tled in the United States, and another 360,000, in Canada.

Although the rate of immigration declined as the century

progressed, the aggregate numbers remained large. Between

1860 and 1910, another 2.3 million Irish immigrated to

the United States, and about 150,000, to Canada.

Whereas 18th-century Scots-Irish had often headed for

the frontier, Irish immigrants after the Great Famine almost

always settled in eastern cities. Many stayed in Boston and

New York to work in industry or fill newly emerging public-

sector jobs as police officers or firemen. Others moved on

to jobs in canal and railway construction, filtering westward

along with the progress of the country. Irish people were

widely discriminated against in the 19th century but created

154154 IRISH IMMIGRATION

an extensive culture of self-help, aided by their numbers and

an almost universal commitment to the Roman Catholic

Church (see N

ATIVISM

). The Irish helped transform the

Catholic Church from a struggling minor denomination at

the turn of the century to a major social and cultural force.

By the 1870s, Irish Catholics came to dominate the church,

which had earlier been led principally by French and Ger-

man priests. In Canada, Irish Catholics joined with the sig-

nificant French minority to further strengthen the Catholic

Church there. By the early 20th century, Irish Americans

were holding key political and financial positions in Boston,

New York, and other large American cities. In Canada, they

played a smaller role, however, being fewer in both number

and percentage than in the United States, and having come

to a society with an already-established Catholic Church in

the French tradition.

As late as the 1920s, an average of more than 20,000

Irish immigrants were arriving annually in the United States.

During the 1930s, however, the annual rate dropped dra-

matically to 1,300. During the 1930s, depression and the

declaration of Irish independence (1937) combined to pro-

vide more stability in Ireland and the beginnings of a grad-

ual improvement in the Irish economy. Between 1951 and

1990, more than 120,000 Irish immigrants arrived in the

United States. Between 1992 and 2002, more than 4,000

arrived annually, with numbers falling dramatically after

1995. The Irish percentage of total immigrant arrivals aver-

aged about 38 percent between 1820 and 1860, ensuring a

substantial impact on the culture of the United States. By

the post–World War II period, the Irish were part of the

American mainstream, and new immigration was largely by

individuals seeking greater economic opportunity. Between

1950 and 2002, Irish immigrants composed only 0.7 per-

cent of all immigrants coming to the United States.

Irish immigration to Canada after the Great Famine

tended to be more heavily Protestant than in the United

States. It also marked the final widespread arrival of Irish

there. In the worst years of the famine, between 1846 and

1850, about 230,000 Irish arrived in the maritime colonies

and the Canadas. Nativism was prevalent in Canada as well

as the United States. The Irish, often arrived ill and in poor

condition and were herded into overcrowded quarantine sta-

tions where infectious diseases were rife, suggesting to local

residents an association with filth and disease. At the peak of

the immigration in the 1830s and 1840s, almost two-thirds

of all Canadian immigrants were Irish. During that period

more than 624,000 Irish immigrants arrived, accounting for

more than half of all Irish immigrants between 1825 and

1978. By the 1850s, higher taxes, less regular transporta-

tion between Ireland and Canada, and lower fares to the

United States diverted most Irish immigrants to the south.

Between 1855 and 1869, fewer than 60,000 Irish arrived.

During the 1880s and 1890s, the few who came tended to

be Protestants who settled in Ontario and the west, though

Irish numbers in the western provinces remained small. Irish

immigration further declined in the 20th century. Of the

25,850 Irish immigrants in Canada in 2001, more than 35

percent (9,185) arrived before 1961, and only 6 percent

(1,835) after 1990. Throughout most of the 19th and 20th

centuries, Irish Protestants have outnumbered Irish

Catholics in Canada about two to one.

See also C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY

OVERVIEW

;U

NITED

S

TATES

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND

POLICY OVERVIEW

.

Further Reading

Bayor, Ronald H., and Timothy J. Meagher, eds. The New York Irish.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

B

r

own, Thomas N. Irish American Nationalism: 1870 to 1890.

Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1966.

B

r

undage, David. The Making of Western Labor Radicalism: Denver’s

Organiz

ed Workers. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

De

zell, Maureen. Irish America: Coming into Clover. New York: Dou-

bleday, 2001.

Diner, H

asia. Erin’

s Daughters in America: Irish Immigrant Women in

the N

ineteenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Pr

ess, 1983.

Dolan, Jay P. The Immigr

ant Church: New York’s Irish and German

C

atholics: 1815–1865. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Pr

ess, 1975.

Elliott, Bruce S. Irish Migrants in the Canadas: A New Approach. Mon-

tr

eal and Kingston: M

cGill–Queen’s University Press, 1988.

Emmons, David. The Butte Irish: Class and Ethnicity in an American

M

ining T

own, 1875–1925. Urbana: University of Illinois Press,

1989.

E

rie, S

tephen R. Rainbow’s End: Irish-Americans and the Dilemmas of

Ur

ban Machine Politics, 1840–1985. Berkeley: University of Cal-

ifornia Pr

ess, 1988.

Freeman, Joshua. In T

ransit: The Transport Workers Union in New York

C

ity, 1933–1966. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Houston, Cecil J., and William J. Smyth. Irish Emigration and Cana-

dian S

ettlement: Patterns, Links, and Letters. Toronto: University

of T

oronto Press, 1990.

Ignatiev, Noel. How the Irish Became White. New York: Routledge, 1996.

K

eneally

, Thomas. The Great Shame and the Triumph of the Irish in

the English S

peaking World. New York: Anchor Books, 2000.

Mackay

, Donald. Flight from Famine: The Coming of the Irish to

Canada. T

oronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1990.

McCaffr

ey, Lawrence. The Irish Diaspora in America. Bloomington:

Indiana U

niversity Press, 1976.

Miller, Kerby A. Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to

N

or

th America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Miller

, Kerby A., et al. Irish Immigrants in the Land of Canaan: Letters

and Memoirs fr

om Colonial and Revolutionary America,

1675–1815. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

M

itchell, B

rian. The Paddy Camps: The Irish of Lowell, 1821–1861.

Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988.

M

urphy

, Terence, and Gerald Stortz, eds. Creed and Culture: The Place

of English-S

peaking Catholics in Canadian Society, 1750–1930.

Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1993.

155IRISH IMMIGRATION 155

Wilson, David A. The Irish in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Historical

Association, 1989.

Italian immigration

Italy was second only to Germany as a source country for

immigrants to the United States after 1820. Although Ital-

ian immigration to Canada was much slower to develop,

only Great Britain sent more immigrants there between 1948

and 1972. According to the 2000 U.S. census and the 2001

Canadian census, 15,723,555 Americans and 1,270,370

Canadians claimed Italian descent. Early areas of Italian con-

centration were N

EW

Y

ORK

,N

EW

Y

ORK

;B

OSTON

; and

Pennsylvania, though the Italian population dispersed widely

throughout the country during the 20th century. During

the 19th century, almost all Italian Canadians lived in M

ON

-

TREAL

. By 2001, Toronto had the largest concentration of

Italians, and Montreal, the second largest.

Italy consists of a long peninsula, the large islands of

Sicily and Sardinia, and numerous smaller islands, all situated

in the central Mediterranean Sea. It is bordered by France on

the west, Switzerland and Austria on the north, and Slovenia

on the east. It covers 116, 324 square miles, and in 2002, it

had a population of about 58 million. More than 95 percent

of the population is ethnically Italian, and more than 80 per-

cent are Roman Catholics. Though Italy was the location of

the great Roman civilization, it was divided politically

throughout the Middle Ages, and its affairs often revolved

around the papal court in Rome. The cultural revival known

as the Renaissance began in northern Italy during the 14th

century, producing some of the greatest scholars, artists, and

philosophers in history. Various parts of the Italian peninsula

were ruled by France, the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and

Austria until the nationalistic Risorgimento movement suc-

ceeded in unifying all the Italian states during the 1860s.

Though on the victorious side of World War I (1914–18),

Italians were dissatisfied with the peace settlement and hit

hard by the weakened international economy. This led to the

rise of the Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who led Italy

into World War II (1939–45) on the side of Nazi Germany.

After being defeated, Italy was reorganized as a republic

(1946). Though politically unstable throughout the 20th

century, the country avoided excessive social turmoil and

played a leading role in the development of the North

Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union.

Many of the earliest European explorers of North

America were Italians, including Christopher Columbus,

John Cabot, Amerigo Vespucci, and Giovanni da Verrazano.

Some northern Italians traveled to North America during

the 17th and 18th centuries, settling in New York, Virginia,

Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and

Georgia. Actual Italian settlement remained small, however,

until after Italian unification during the 1860s. Between

1820 and 1860, only about 14,000 Italians immigrated to

the United States, most coming as individuals from north-

ern Italy, seeking economic opportunity. Some were

attracted to the West Coast with the C

ALIFORNIA GOLD

RUSH

of 1849. By the Civil War (1861–65), Italians were

widely dispersed around the country, with California

(2,805) and New York (1,862) having the largest popula-

tions. The first substantial migration came after the pro-

mulgation of a new Italian constitution in 1861, which

tended to benefit the industrialized and advanced north, at

the expense of the already impoverished, semifeudal agri-

cultural south. As the population in Italy soared, increasing

from 25 million in 1861 to 35 million in 1901, the plight of

peasant laborers in the south worsened. Large estates were

still often controlled by absentee landlords who did little to

bring modern technology into the farming process. As a

result, desperate sharecroppers and laborers left the worn-

out soil for new opportunities in the United States.

Italian immigration increased dramatically during the

1880s, with the source area gradually shifting from north to

south. Between 1876 and 1924, when the restrictive J

OHN

-

SON

-R

EED

A

CT

was passed, more than 4.5 million Italians

immigrated to the United States, about three-quarters of

them from the impoverished south. Typically immigrants

were young men who hoped to work one or two seasons

before returning to Italy to start a better life. They usually

spoke no English, so they turned to labor bosses (see

PADRONE SYSTEM

) who established widespread networks

for providing Italian labor to construction jobs throughout

the East. Because the padrones sometimes cheated the vul-

nerable immigrants, they were carefully scrutinized by gov-

ernment and social workers and began to decline in

influence by the first decade of the 20th century. After the

turn of the century, gender rates were more balanced. By

1910, Italian women made up more than one-third of the

female workforce in New York’s garment industry (see

I

NTERNATIONAL

L

ADIES

’G

ARMENT

W

ORKERS

’U

NION

)

and more than 70 percent of the total workforce of the arti-

ficial flower industry.

The rate of return for Italians was high. Between 1899

and 1924, 3.8 million Italians arrived, while 2.1 million

returned to Italy during the same period. Italian immigra-

tion reached its peak in the first decade of the 20th century,

when more than 2 million Italians arrived. Generally poor,

uneducated, and Roman Catholic, Italians suffered severely

from

NATIVISM

. As a result, they created social enclaves—

Little Italies—in most major American cities, fostering a

love of the old country and traditional ways of life, though

these neighborhoods were seldom inhabited solely by Ital-

ians. In part, this was because Italian immigrants frequently

moved. In the first generation, they generally lived in the

worst slums of New York City, Boston, Philadelphia,

Chicago, and San Francisco. By the turn of the century, Ital-

ian families had often moved to more spacious working-class

neighborhoods. By 1910, there were 340,765 Italian immi-

156156 ITALIAN IMMIGRATION

grants in New York City, the largest Italian population out-

side Italy and much larger than such famous Italian cities as

Florence and Venice. New York’s Italian community, like

most others in the country, was dominated by southern Ital-

ians. The one major exception to this trend was San Fran-

cisco, where fewer southern Italians migrated.

By the late 1920s, Italian immigration had dropped sig-

nificantly. Though Italian Americans numbered in the mil-

lions, they still had little political power to show for it.

Fiorello H. La Guardia, mayor of New York City from 1934

to 1945, was a notable exception. About 116,000 came dur-

ing the 1930s and 1940s, most blending smoothly into the

growing middle-class Italian community. Immigration

revived during the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s,

when 400,000 arrived, but tapered off again thereafter.

Greater political stability and economic development in

Italy after 1980 kept immigration numbers relatively low.

Between 1992 and 2002, Italian immigration averaged

about 2,500 per year.

Much less receptive to non-British immigrants, Canada

was slow to encourage Italian immigration. A small number

of nobles aided in the French and British settlement of

North America. Enrico di Tonti served as a lieutenant on

several of explorer René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle’s expe-

ditions between 1679 and 1682. After the end of the

Napoleonic Wars (1815), several hundred Italians who had

served in the Meuron and de Watteville foreign regiments of

the British army settled in Canada, principally around

Drummondville, Quebec, and in southern Ontario. A small

number of Italians immigrated individually during the 19th

century, but the numbers remained small until the turn of

the century. In 1901, there were still fewer than 11,000 Ital-

ians in Canada, almost all of whom lived in Montreal.

Between the 1870s and 1914, more than 13 million Italians

emigrated. Before 1900, about 70 percent were bound for

Argentina, Brazil, and other South American destinations,

and most of the rest for the United States. After 1900, about

two-thirds settled in North America. The number choosing

157ITALIAN IMMIGRATION 157

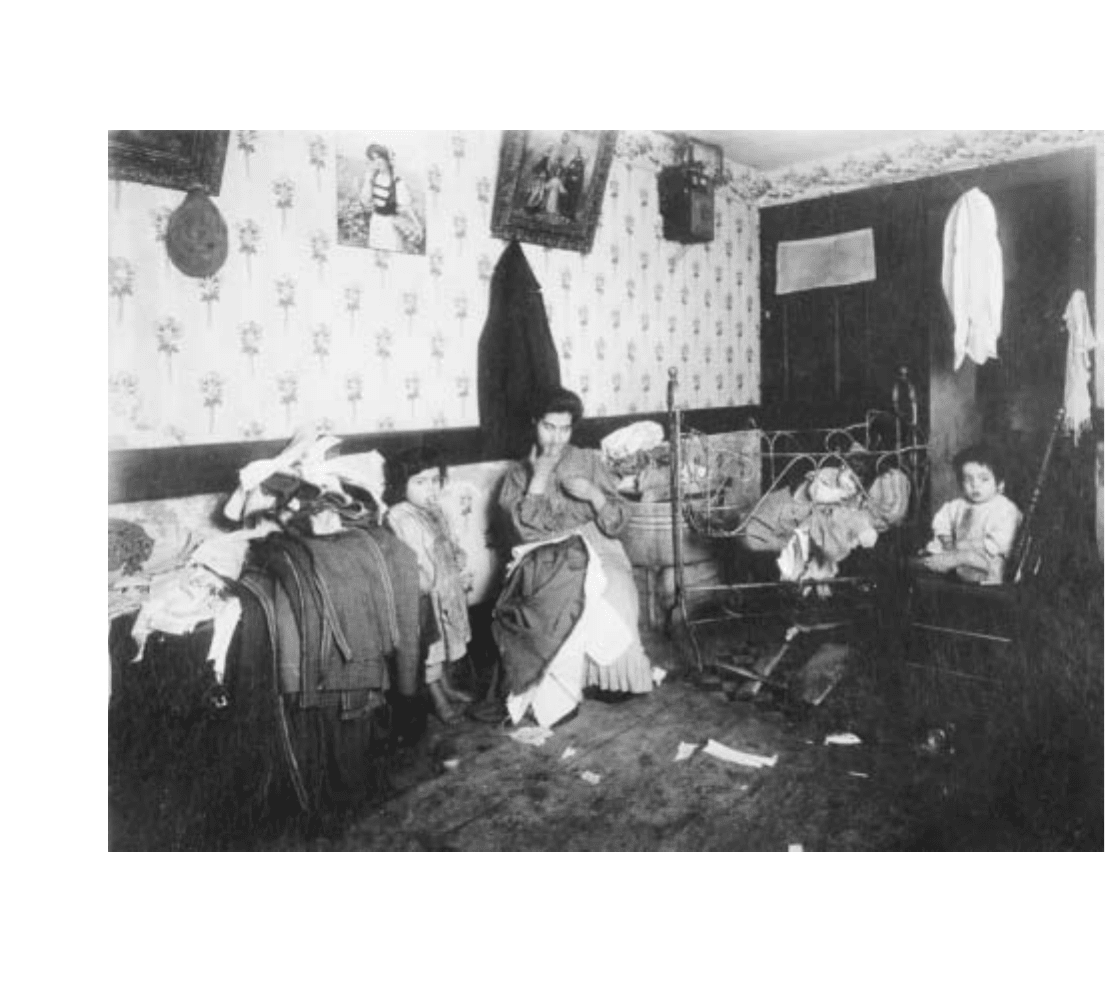

This 1912 photo shows Mrs. Guadina, a struggling Italian immigrant in NewYork City, trying to complete her batch of piece work

in order to be paid. According to the visiting city official, there seemed to be no food in the house, the father was out of work,

and a fourth child was expected soon.

(Photo by Lewis W. Hine for the Department of Commerce and Labor, Children’s Bureau/National

Archives #102-LH-2821)

158

Canada was small, and often closely related to work oppor-

tunities originating in the United States. The Canadian

Pacific Railway, for instance, imported laborers both from

the United States and Italy.

The great period of Italian immigration to Canada

came during the 1950s and 1960s, when more than

500,000 immigrants arrived. Though many left Italy as tem-

porary workers, a far greater number of the post–World War

II immigrants stayed to settle. As the Canadian economy

expanded, Italy became an important source for construc-

tion workers and unskilled labor, taking advantage of new

Canadian policies that liberalized provisions of family spon-

sorship. The Canadian government concluded a bilateral

agreement with Italy in 1950, allowing Italian Canadians

greater opportunities for bringing family members into the

country. During the 1950s, about 80 percent of Italian

immigrants were sponsored family members. The more

restrictive

IMMIGRATION REGULATIONS

of 1967 made it

more difficult for unskilled Italians to qualify and coincided

generally with a revival in the Italian economy. As a result,

Italian immigration declined sharply during the 1970s,

when only 48,000 arrived. In the 1980s, still fewer Italians

came, averaging less than 2,000 per year. Of the 314,455

Italian immigrants residing in Canada in 2001, fewer than

15,000 came during between 1981 and 2001.

See also C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY

OVERVIEW

;U

NITED

S

TATES

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND

POLICY OVERVIEW

.

Further Reading

Alba, Richard D. “Italian Americans: A Century of Ethnic Change.”

In Origins and Destinies: Immigration, Race and E

thnicity in

America. Ed. Silvia Pedraza and Rubén G. Rumbaut. Belmont,

Calif

.: Wadsworth, 1996.

———. Italian Americans: Into the Twilight of Ethnicity. Englewood

Cliffs, N.J.: P

r

entice Hall, 1985.

Briggs, John W. An Italian Passage: Immigrants to Three American

C

ities, 1890–1930. N

ew Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press,

1978.

D

e Conde, Alexander

. Half Bitter, Half Sweet: An Excursion into Ital-

ian-American H

istory. New York: Scribner’s, 1971.

Foerster, R

obert F. The Italian Emigration of Our Times. C

ambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1924.

Gallo, Patrick. Old Bread, New Wine: A Portrait of Italian Americans.

Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1981.

G

ans, Herbert. Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian-Americans.

New York: Free Press, 1982.

H

a

rvey, Robert F. From the Shores of Hardship: Italians in Canada.

Welland, Canada: Soleil, 1993.

M

angione,

Jerre, and Ben Morreale. La Storia. New York: Harper,

1993.

Morr

eale, B

en, and Robert Carola. Italian Americans: The Immigrant

E

xperience. Southport, Conn.: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 2000.

Orsi, R

obert A. The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in

Italian Har

lem, 1880–1950. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University

P

ress, 1988.

Perin, Roberto, and Franc Sturino, eds. “Arrangiarsi

”: The Italian

Immigr

ation Experience in Canada. Montreal: Guernica, 1989.

Ramirez, Bruno. The Italians in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Historical

Association, 1989.

Smith, Judith E. Family Connections: A History of Italian and Immi-

grant Lives in Pro

vidence, Rhode I

sland, 1900–1940. Albany: State

University of N

ew York Press, 1985.

Spada, A. V. The Italians in Canada. Ottawa and Montreal: Italo-

Canadian Ethnic and Historical Research Center, 1969.

158 ITALIAN IMMIGRATION

Jamaican immigration

Jamaicans are the largest West Indian immigrant group in

Canada and the third largest in the United States, behind

Puerto Ricans and Cubans. In the U.S. census of 2000 and

the Canadian census of 2001, 736,513 Americans and

211,720 Canadians claimed Jamaican descent. The majority

of Jamaicans in the United States live in New York City and

other urban communities of the Northeast, though a signif-

icant number also live in Florida. Toronto is by far the pre-

ferred destination of Jamaicans in Canada.

The island of Jamaica occupies 4,200 square miles in

the Caribbean Sea. Its nearest neighbors are Cuba to the

north and Haiti to the east. In 2002, the population was

estimated at 2,665,636. The people are 90 percent black,

descended from slaves brought to Jamaica by the British

during the 17th and 18th centuries. About 61 percent of the

population is Protestant and 4 percent Roman Catholic.

More than a third of Jamaicans are members of other reli-

gious groups, many of which teach African revivalist doc-

trines. The best-known Afro-Caribbean religion is

Rastafarianism, which venerates Haile Selassie, who before

becoming emperor of Ethiopia was named Ras Tafari, as a

god. It was made internationally famous by the reggae musi-

cian Bob Marley in the 1970s, who sang about its belief in

the eventual redemption and return of blacks to Africa.

Jamaica was inhabited by Arawak peoples until Columbus

visited the island in 1494 and brought European diseases

that soon wiped out the native population. The island was

occupied by Britain in the 1650s, becoming its principal

sugar-producing island in the Caribbean. Jamaica won its

independence in 1962. Socialist governments throughout

the 1970s frequently clashed with the United States and

Canada over bauxite mining interests and

COLD WAR

ideol-

ogy, leading to considerable political unrest in Jamaica. Dur-

ing the 1980s, Jamaican politics became more conservative,

and relations with the North American mainland improved.

Prior to the 1960s, both the United States and Canada

treated immigrants from Caribbean Basin dependencies and

countries, in various combinations, as a single immigrant unit

known as “West Indians,” making it impossible to determine

exactly how many Jamaicans were among them. Before 1965,

however, Jamaican immigrants clearly predominated, and

English-speaking immigrants generally far outstripped others.

Between 1900 and 1924, about 100,000 West Indians immi-

grated to the United States, many of them from the middle

classes. The restrictive J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

(1924) and eco-

nomic depression in the 1930s virtually halted their immi-

gration, but some 40,000 had already established a cultural

base in New York City, particularly in Harlem and Brooklyn.

About 41,000 West Indians were recruited for war work after

1941, but most returned to their homes after World War II.

Isolationist policies of the 1950s and relatively open access to

Britain kept immigration to the United States low until pas-

sage of the Immigration Act of 1965, which shifted the basis

of immigration from country of origin to family reunification.

The M

C

C

ARRAN

-W

ALTER

I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURAL

-

IZATION

A

CT

of 1952 had established an annual quota of

only 800 for all British territories in the West Indies. When

159

J

4

Jamaica became independent, however, the country qualified

for increased immigration quotas. Between 1992 and 2002,

an average of more than 16,000 Jamaicans immigrated to the

United States annually.

Many Jamaicans in both the United States and Canada

were well educated and enjoyed greater economic success

than other Americans of African descent. Their political

influence in the United States was proportionally greater

than their numbers would suggest, leading to tension

between West Indians generally and African Americans.

Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey, who came to the

United States in 1916, and U.S. secretary of state Colin

Powell, son of Jamaican immigrants, brought considerable

attention to the Jamaican immigrant community during

the 20th century.

West Indian immigration to Canada remained small

throughout the 20th century. Following restrictive legisla-

tion enacted in 1923, it is estimated that only 250 West

Indians were admitted during the entire decade of the

1920s. By the mid 1960s, only 25,000 West Indians lived

there. Canadian regulations after World War II (1939–45)

prohibited most black immigration, and special programs,

such as the 1955 domestic workers’ campaign, allowed only

a few hundred well-qualified West Indians into the country

each year until 1967, when the point system was introduced

for determining immigrant qualifications. Jamaica never-

theless maintained the largest source of Caribbean immi-

grants. Of Canada’s 120,000 Jamaican immigrants in 2001,

more than 100,000 came after 1970.

See also W

EST

I

NDIAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Barrett, Leonard E. The Rastafarians. Boston: Beacon Press, 1997.

Eato, George. Canadians of J

amaican H

eritage. Chatham, Canada:

1986.

Foner, Nancy

. “The Jamaicans: Race and Ethnicity among Migrants in

New York City.” In New Immigrants in New York. Ed. Nancy

Foner. New York: Columbia University Press, 1987.

Kasinitz, Philip. Caribbean New York: Black Immigrants and the Poli-

tics of R

ace. I

thaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1992.

Owens-W

atkins, Irma. Blood Relations. Bloomington: University of

Indiana P

ress, 1996.

Palmer, R. W. Pilgrims from the Sun: West Indian Migration to Amer-

ica. New York: Twayne, 1995.

P

arrillo, V

incent. Strangers to These Shores. 5th ed. Boston: Allyn and

Bacon, 1997.

V

ickerman, Milton. Crosscurrents: West Indian Immigrants and Race.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

W

alker, James W. St. G. The West Indians in Canada. Ottawa: Cana-

dian Historical Association, 1984.

W

estmoreland, Guy T., Jr. West Indian Americans. Westport, Conn.:

G

r

eenwood Press, 2001.

Jamestown,Virginia See V

IRGINIA COLONY

.

Japanese immigration

For most of the 20th century, Japanese Americans formed

the largest Asian ethnic group in the United States. Accord-

ing to the 2000 U.S. census and the 2001 Canadian census,

1,148,932 Americans and 85,230 Canadians claimed

Japanese descent. Although many Japanese immigrants

came to the United States as laborers, by the 1960s they

had largely moved out of ethnic neighborhoods and into the

American mainstream. In 2000, they were still highly con-

centrated in California and on the West Coast, though they

were increasingly dispersing throughout the country. More

than 40 percent of Japanese Canadians live in British

Columbia.

Japan is a 152,200-square-mile archipelago situated in

the Pacific Ocean about 100 miles east of Korea and 500

miles east of China. The Russian island of Sakhalin is Japan’s

nearest neighbor to the north. In 2002, the population was

estimated at 126,771,662, more than 99 percent of whom

were ethnic Japanese. The major religions are Buddhism and

Shintoism. A mountainous country with few natural

resources, Japan is among the most densely populated coun-

tries in the world, a factor largely contributing to its immi-

gration history. Japan borrowed heavily from Chinese

culture between the 5th and 10th centuries but generally

adapted Chinese models to its own culture patterns and

transformed them into a unique Japanese culture. After a

brief period of trade and contact with Portuguese, Dutch,

and English merchants and missionaries, Japan largely

closed itself off from the world during the Tokugawa era

(1603–1868). During the 1850s, the United States forced

Japan to open its ports to trade, much as Britain had done in

China during the 1830s. Unlike China, however, Japan was

relatively successful in modernizing without sacrificing its

culture. Borrowing heavily from Western models, after

1868, Japan created a parliamentary democracy, eliminated

many elements of its feudal social system, and modernized

its military. After defeating China (1894–95) and Russia

(1904–05), Japan became the principal regional power in

East Asia. During the 1920s and 1930s, the fragile and lim-

ited Japanese democracy was heavily influenced by the

Japanese army and navy, which sought military solutions to

overpopulation and a lack of natural resources. Japan’s occu-

pation of Manchuria (1931) and northern China (1937) led

into World War II (1939–45), which ended with the

destruction of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

by U.S. atomic bombs in August 1945. With the aid of U.S.

reconstruction, Japan became an important

COLD WAR

ally

and developed one of the world’s strongest economies from

the 1970s on.

Patterns of Japanese immigration were similar in both

the United States and Canada. Significant Japanese migra-

tion to the American West began in the 1880s in the wake

of the C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

(1882). Prohibited from

hiring Chinese laborers, plantation owners in Hawaii

160 JAMESTOWN,VIRGINIA

brought Japanese, many of whom had been displaced by

the demise of the old Tokugawa regime: Between 1885 and

1904, more than 100,000 Japanese were brought to work in

Hawaii, making them the largest ethnic group in the

islands. At the same time, many Japanese students and

other travelers were venturing to the mainland. By 1900,

they had been joined by laborers, making a Japanese popu-

lation of almost 30,000 in California. Between 1890 and

1910, a similar number landed in British Columbia,

though many continued on to the United States. As thou-

sands of Japanese migrated to North America annually in

the wake of U.S. annexation of Hawaii in 1898, Ameri-

cans and Canadians in California and British Columbia

protested strongly. Between April and June 1900, almost

8,000 Japanese laborers arrived in British Columbia (due in

part to the pent-up demand), alarming local citizens.

Though the Japanese government agreed to stop immigra-

tion by the end of July, the provincial legislature feared it

would only be a temporary decision and thus passed “An

Act to Regulate Immigration into British Columbia,”

requiring Japanese to complete an application for entry in a

European language. Clearly in violation of the Anglo-

Japanese Treaty of 1894, the measure was disallowed by

the Canadian government, leading to a constitutional

impasse. A Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese

Immigration recommended that anti-Japanese legislation

be allowed only if the Japanese government lifted its ban on

laborers. Although almost no Japanese entered British

Columbia between 1901 and 1907, American prohibitions

on laborers in 1907 and a rapidly growing economy in

British Columbia combined to encourage a return of

Japanese laborers, between 5,000 and 10,000 in 1907–08.

Once again alarmed, Canada secured a Gentlemen’s Agree-

ment that the Japanese government would issue no more

than 400 passports annually to laborers and domestic ser-

vants bound for Canada.

Californians were similarly afraid of the “yellow peril,”

especially with the economic uncertainty following the San

Francisco earthquake in April 1906. The mayor and the Asi-

atic Exclusion League, with almost 80,000 members, pres-

sured the San Francisco school board to pass a measure

segregating Japanese students (October 11), violating Japan’s

most-favored-nation status and deeply offending the

Japanese nation. U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt repu-

diated the school board’s decision and praised Japan. At the

same time, between December 1906 and January 1908, he

negotiated three separate but related agreements that

addressed both Japanese concerns over the welfare of the

immigrants and California concerns over the growing num-

bers of Japanese laborers. In February 1907, immigration

legislation was amended to halt the flow of Japanese laborers

from Hawaii, Canada, or Mexico, which in turn led the San

Francisco school board to rescind (March 13) their segrega-

tion resolution. In discussions of December 1907, the

Japanese government agreed to restrict passports for travel to

the continental United States to nonlaborers, former resi-

dents, or the family members of Japanese immigrants. This

allowed for the continued migration of laborers to Hawaii

and for access to the United States by travelers, merchants,

students, and

PICTURE BRIDES

. While the U.S. G

ENTLE

-

MEN

’

S

A

GREEMENT

helped the two countries move past

the crisis, the whole matter left an indelible impression of

the strength of American

NATIVISM

.

Japanese immigration to the United States was almost

totally halted with passage of the J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of

1924. During the 1930s and 1940s, fewer than 200

Japanese immigrated to the United States annually, and less

than half that number to Canada. Relations worsened fol-

lowing Japan’s invasion of China in 1937. When the navy of

imperial Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December

7, 1941, Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians were

widely suspected of sympathy with their homeland. Despite

the absence of any evidence of sabotage or espionage, on

February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed

Executive Order 9066, which led to the forcible internment

of 120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were

born in the United States. In the same month, the Canadian

government ordered the expulsion of 22,000 Japanese Cana-

dians from a 100-mile strip along the Pacific coast (see

J

APANESE INTERNMENT

).

Provisions of the M

C

C

ARRAN

-W

ALTER

I

MMIGRATION

AND

N

ATURALIZATION

A

CT

of 1952, in conjunction with

the rapid development of the Japanese economy, led to a

steady but unspectacular immigration starting in the 1950s,

averaging almost 5,000 per year between 1961 and 1990.

With a healthy Japanese economy through the 1980s, most

Japanese preferred to remain at home, but the economic

downturn of the 1990s led to increased migration in search

of economic opportunities. Between 1992 and 2002,

Japanese immigration averaged about 7,500 per year.

Between 1910 and 1970, Japanese were the largest Asian

ethnic group in the United States but by 2001 had dropped

to sixth, behind Chinese, Filipinos, Asian Indians, Koreans,

and Vietnamese.

Between 1900 and 1937, between 25,000 and 30,000

Japanese entered Canada, mostly as fishermen or laborers.

These numbers are misleading, however, as many immi-

grants of this period used Canada as a backdoor for entry

to the United States as a result of the restrictions of

Canada’s Gentlemen’s Agreement. Between 1937 and

1952, fewer than 200 Japanese entered Canada, most as a

result of family reunification or for humanitarian reasons.

As the Japanese economy began to boom in the 1960s,

immigration rates to Canada remained low, averaging

about 500 in most years, a little higher in times of eco-

nomic uncertainty. Most of these immigrants were young,

well-educated professionals. Of 17,630 Japanese immi-

grants in Canada in 2001, almost 8,000 came between

JAPANESE IMMIGRATION 161

1991 and 2001, the largest decade of immigration in the

post–World War II era.

Further Reading

Adachi, Ken. The Enemy That Never Was: A History of the Japanese

Canadians. T

oronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1991.

Daniels, Roger

. Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United

S

tates since 1850. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

Herman, M

asako. The Japanese in America, 1843–1973. Dobbs Ferry,

N.Y.: O

ceana, 1974.

Makabe, Tomoko. The Canadian Sansei. Toronto: University of

T

or

onto Press, 1998.

Moriyama, Alan T. Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies and

H

awaii, 1894–1908. H

onolulu: University of Hawaii Press,

1985.

N

akano, M.

Japanese American Women: Three Generations,

1890–1900. San Francisco: Mina Press, 1990.

Niiya, B., ed. Encyclopedia of Japanese American History: An A-to-Z

R

eference from 1868 to the Present. Updated edition. New York:

Facts On File, 2000.

R

o

y, Patricia E. A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians

and Japanese I

mmigrants, 1858–1914. Vancouver, Canada: Uni-

versity of British Columbia Press, 1989.

S

pickar

d, Paul. Japanese Americans: The Formation and Transforma-

tion of an Ethnic G

roup. New York: Twayne, 1996.

Ward, W. P

eter. The Japanese in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Histori-

cal Association, 1982.

Japanese internment, World War II

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on Decem-

ber 7, 1941, Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians

were widely suspected as supporters of the aggressive mili-

tarism of the Japanese Empire. Despite the absence of any

evidence of sabotage or espionage, on February 19, 1942,

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order

9066, which led to the forcible internment of 120,000

Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom had been born in

the United States. In the same month, the Canadian gov-

ernment ordered the expulsion of 22,000 Japanese Canadi-

ans from a 100-mile strip along the Pacific coast.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the U.S.

Congress passed the Alien Registration Act (1940), requir-

ing all non-naturalized aliens aged 14 and older to register

with the government and tightening naturalization

requirements. With the U.S. declaration of war against

Germany, Italy, and Japan following the attack on Pearl

Harbor, more than 1 million foreign-born immigrants

from those countries became “enemy aliens.” Italians and

Germans were so deeply assimilated into American culture,

however, that they were largely left alone. More visibly dis-

tinct and ethnically related to the attackers, Japanese

immigrants and Americans of Japanese descent were

quickly targeted in the early-war hysteria. The territory of

Hawaii was put under military rule, and the 37 percent of

its population of Japanese ancestry was carefully watched,

though they were not interned or evacuated. On the main-

land, many politicians and members of the press, along

with agricultural and patriotic pressure groups, urged

action against the Japanese, leading to Executive Order

9066, empowering the War Department to remove people

from any area of military significance.

Japanese Americans were forced to dispose quickly of

their property, usually at considerable loss. They were often

allowed to take only two suitcases with them. Internment-

camp life was physically rugged and emotionally challeng-

ing. Most nisei, or second-generation Japanese in the United

States, thought of themselves as thoroughly American and

felt betrayed by the justice system. They nevertheless

remained loyal to the country, and eventually more than

33,000 served in the armed forces during World War II.

Among these were some 18,000 members of the 442nd Reg-

imental Combat Team, which became one of the most

highly decorated of the war. Throughout the war, about

120,000 were interned under the War Relocation Authority

in one of 10 hastily constructed camps in desert or rural

areas of Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Arkansas, Idaho, Califor-

nia, and Wyoming. In three related cases that came before

the Supreme Court—Yasui v

. United States (1942),

H

irabayashi v. United States (1943), and K

OREMATSU V

.

U

NITED

S

TATES

(1944)—the government’s authority was

upheld, though a dissenting judge noted that such collective

guilt had been assumed “based upon the accident of race.”

The camps were finally ordered closed in December 1944.

The Evacuation Claims Act of 1948 provided $31 million in

compensation, though this was later determined to be less

than one-10th the value of property and wages lost by

Japanese Americans during their internment. In Canada, the

government bowed to the unified pressure of representatives

from British Columbia, giving the minister of justice the

authority to remove Japanese Canadians from any desig-

nated areas. While their property was at first impounded

for later return, an order-in-council was passed in January

1943 allowing the government to sell it without permission

and then to apply the funds to the maintenance of the

camps. With labor shortages by 1943, some Japanese Cana-

dians were allowed to move eastward, especially to Ontario,

though they were not permitted to buy or lease lands or

businesses. Though it was acknowledged that “no person of

Japanese race born in Canada” had been charged with “any

act of sabotage or disloyalty during the years of war,” the

government provided strong incentives for them to return to

Japan. After much debate and extensive challenges in the

courts, more than 4,000 returned to Japan, more than half

of whom were Canadian-born citizens. More than 13,000 of

those who stayed left British Columbia, leaving fewer than

7,000 in the province.

In 1978, the Japanese American Citizens’ League

formed the National Committee for Redress, spearheading

162 JAPANESE INTERNMENT, WORLD WAR II

efforts for a formal apology and compensation for survivors.

In 1980, Congress established the Commission on Wartime

Relocation and Internment of Citizens (CWRIC). After 18

months of investigations, the commission issued its final

report in 1983, concluding that “a grave injustice was done

to American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese

descent.” No documented case of sabotage or disloyalty by

a Japanese American was found, and it was discovered that

the Justice and War Departments had altered records and

thereby misled the courts. After a further five years of nego-

tiation, in 1988, the Civil Liberties Act was signed by Pres-

ident Ronald Reagan, who noted that Japanese Americans

had proven “utterly loyal,” providing an apology and

$20,000 to each camp survivor still living. The eventual pay-

out was more than $1.6 billion. Less than two weeks later,

the Canadian government publicly apologized and provided

compensation, including $12,000 to each survivor, a $12

million social and educational package for the Japanese

community, and a further $12 million to the Canadian Race

Relations Foundation.

Further Reading

Daniels, Roger. Prisoners without Trial: Japanese Americans in World

War II. N

ew York: Hill and Wang, 1993.

Hatamiya, Leslie

T. Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and the Pas-

sage of the Civil L

iberties Act of 1988. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford

Univ

ersity Press, 1993.

Hillmer, Norman, ed. On Guard for Thee: War, Ethnicity, and the

C

anadian S

tate, 1939–1945. Ottawa: Canadian Committee for

the Histor

y of the Second World War, 1988.

Irons, Peter. Justice Delayed: The Record of the Japanese American Intern-

ment C

ases. M

iddletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press,

1989.

Miki, R

o

y, and Cassandra Kobayashi. Justice in Our Time: The

J

apanese-Canadian Redress Settlement. Vancouver, Canada: Talon-

books, 1991.

Nakano, T

akeo

Ujo. Within the Barbed Wire Fence: A Japanese Man’s

A

ccount of his Internment in Canada. Toronto: University of

Tor

onto Press, 1980.

Roy, Patricia, et al. Mutual H

ostages: Canadians and Japanese during the

S

econd World War. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990.

Sunahara, A. G. The P

olitics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese

Canadians during the Second

World War. Toronto: Lorimer, 1981.

Jewish immigration

The Jewish immigrant experience was unique in North

American history. Jews suffered the double discrimination of

being both foreign and non-Christian in countries whose

cultures were largely defined by Christian patterns of belief

and practice. After much discrimination in the 19th and

early 20th centuries, the Jewish community as a whole nev-

ertheless prospered in the United States and Canada. In

2001, the American Jewish population was estimated at just

over 6 million, or about 2.3 percent of the population.

According to the Canadian census of 2001, about 350,000

Canadians claimed Jewish descent, about 1.2 percent of the

total population. N

EW

Y

ORK

,N

EW

Y

ORK

is the center of

American Judaism, with a population of more than 1.5 mil-

lion. Jews make up almost 9 percent of the population of

New York State. Toronto and Montreal have the largest Jew-

ish Canadian populations.

Statistics on Jewish immigration are more problematic

than for most groups. Before 1948, there was no Jewish

homeland, as most Jews had been driven out of Palestine in

the first century by the Romans. As most immigration statis-

tics for the 19th and 20th centuries related principally to

country of origin or land of birth, Jewish numbers were

obscured. Closely related to the means of collecting data was

the group’s wide dispersion. Jews inhabited most European

countries and many Middle Eastern countries, complicating

estimates based on emigration records or historical circum-

stances. Having come in large numbers from central Europe

(where they spoke German), eastern Europe (where they

spoke Yiddish), and North Africa and the Balkans (where

they spoke Ladino), they had no common language and

quickly gave up their Old World languages in favor of

English or French. Finally, there is no clear consensus on the

standards for being Jewish. Although Judaism is rooted in

the traditional religious beliefs and practices that originated

in Palestine during the second millennium

B

.

C

. perhaps 20

percent or more of Jews are not religious. Among those who

are, the Orthodox carefully observe the historical rules of the

Torah, while Reform Jews look to scripture for moral prin-

ciples that can be adapted to the changing circumstances of

Jewish life. Reconstructionist Jews are more concerned with

the preservation of Jewish culture than Jewish religion,

JEWISH IMMIGRATION 163

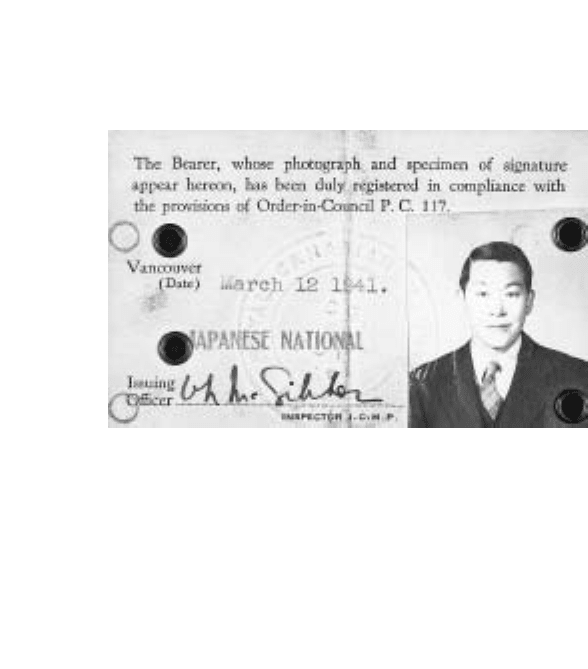

This photo shows the front of Sutekichi Miyagawa’s

internment identification card issued by the Canadian

government in compliance with Order-in-Council P.C. 117,

Vancouver, British Columbia, March 12, 1941. During World

War II, some 120,000 Japanese Americans and 22,000 Japanese

Canadians were interned or relocated.

(National Archives of

Canada/PA-103542)