Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

broadly conceived changes that would be embodied in the

I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1976.

Further Reading

Hawkins, Freda. Canada and Immigration. 2d ed. Kingston and Mon-

treal: M

cGill–Queen’s University Press, 1989.

———. Critical

Years in Immigration: Canada and Australia Compared.

Kingston and M

ontreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1989.

Kelley

, Ninette, and Michael Trebilcock. The Making of the Mosaic: A

History of C

anadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of

T

oronto Press, 2000.

Immigration Restriction League (IRL)

Founded by Charles Warren in Boston in 1894, the Immi-

gration Restriction League (IRL) proposed a literacy test for

the purpose of r

estricting immigration. With the support of

prominent Boston families and a large number of aca-

demics, the IRL came near success in 1895, 1903, 1912, and

1915. Finally, with passage of the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of

1917, a literacy test was adopted, with both houses of

Congress overriding President Woodrow Wilson’s veto. This

marked a turning point in American immigrant legislation,

moving away from regulation toward restriction.

As more and more Americans began to question the wis-

dom of an open-door policy toward immigrants, the most

radical proposal for keeping out immigrants generally was the

literacy test, an idea first introduced by the economist

Edward W. Bemis in 1887. Bemis proposed that all male

adults who could not read or write their own language should

be prohibited from entering the United States. The literacy

test gained little support until a cholera epidemic brought

by immigrant ships in 1892 and the depression of the fol-

lowing year led to broader support for extreme measures. The

IRL adopted the test as their political goal. Leading the orga-

nization’s lobbying efforts were two Harvard classmates,

Prescott Farnsworth Hall and Robert De Courcy Ward.

Despite antipathies toward the Irish, the organization was

prepared to accept their presence in American life at the

expense of eastern and southern Europeans. As Hall put it,

the question was whether the United States would be “peo-

pled by British, German and Scandinavian stock, histori-

cally free, energetic, progressive, or by Slav, Latin and Asiatic

races, historically downtrodden, atavistic, and stagnant.”

Although literacy legislation was vetoed on four occasions,

Hall and Ward were persistent, continuing to revive the issue

at every favorable opportunity, appealing to business and

labor leaders as well as members of Congress. Active U.S.

involvement in the European war from 1917 led to a rapid

increase in xenophobia and thus to conditions favorable to

passage of the restrictive legislation, which outlawed “all

aliens over sixteen years of age . . . who cannot read the

English language, or some other language or dialect.”

See also

NATIVISM

.

Further Reading

Curran, Thomas. Xenophobia and Immigr

ation, 1820–1930. Boston:

Twayne Publishers, 1975.

Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism,

1860–1925. 2d ed. N

ew Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University

Press, 1988.

Solomon, Barbara Miller. Ancestors and Immigrants. Cambridge,

Mass.: H

ar

vard University Press, 1956.

indentured servitude

Indentured servitude as a means of colonization or immi-

gration is a labor system in which a laborer agrees to pro-

vide labor exclusively for one employer for a fixed number of

years in return for his or her travel, living expenses and often

some financial consideration at the end of service. The nor-

mal contract of indenture in colonial North America pro-

vided the servant with cost of passage from Europe; food,

shelter, and clothing during the period of indenture; and

land or other provisions when the contract was completed.

Indentures in the middle and southern colonies were usually

fixed at five to seven years, with seven being most common.

In New England and N

EW

F

RANCE

, a period of three or

four years was most common.

The indenture system worked because it met the needs

of North American entrepreneurs and agriculturalists, who

were short of labor; European paupers, who were short of

money; and European governments, which had too many

paupers and criminals with whom to deal. Private operations

such as the Virginia Company, the Plymouth Company, and

the Company of New France realized that the lure of land

was not enough to attract potential investors; there had to be

a laboring class available to do most of the menial work.

Companies advertised varying combinations of free passage

to the Americas, land, tools, and clothing for a servant who

completed the period of servitude. Some servants were pre-

purchased by colonial merchants or landowners. During the

first half of the 17th century, prepurchasing posed a consid-

erable risk for the buyer, however, for the servant was more

likely to die than to complete his or her term of service. To

address the risk, the Virginia Company developed a head-

right system that rewarded purchasers with 50 acres of land

for every servant brought to the colony at their own expense.

In other cases, prospective settlers would indenture them-

selves to the company, which would then sell the contracts

upon arrival in American ports. Most indentured servants

were from the agricultural classes, though craftspeople and

artisans were always in demand. By the 18th century, skilled

workers were sometimes able to negotiate especially favor-

able terms of indenture.

Many servants, like settlers generally, did not survive the

voyage to the New World. If they did successfully complete

their indenture, there were often legal challenges to obtain-

ing what they had been promised. Life was harsh, and laws

144144 IMMIGRATION RESTRICTION LEAGUE

were passed prohibiting servants from marrying, trading, or

having children. Corporal punishment was common, and

infractions of the law often included extension of the term

of service. Men and women indentured as a couple were

sometimes divided, and if one spouse died, the other was

required to serve both terms. Children were indentured

until the age of 21. As news of these hardships filtered back

to Britain, fewer paupers willingly undertook to indenture

themselves. In the second half of the 17th century, people

were frequently forced into servitude through deceit, brutal-

ity, or as an alternate punishment for crime. In some years,

thousands of criminals were deported to America as inden-

tured servants.

Indentured servitude had a profound effect on the

development of North America. It was most common in

the middle and southern colonies, where it accounted for

more than half of all colonial immigrants but was utilized

widely throughout the British and French colonies. On the

Canadian prairies, servants from Scotland and Ireland

married Native American women, and their children were

first-generation Métis. Servants came from all classes and

races and from many European countries, though English

paupers and convicts made up the majority. A few rose in

society according to their early expectations, with some

becoming landowners and legislators. Most, however,

remained servants or were provided with marginal lands

when their contracts were fulfilled. Often pushed into the

most dangerous and least profitable areas of settlement,

these poor whites became discontented and hard to gov-

ern. The first Africans transported to America came as

indentured servants sold at Jamestown, in 1619. As

planters realized that a seven-year term of service created

an unsteady supply of labor and that freedmen and -

women were often dissatisfied with their social condition,

landowners increasingly turned to

SLAVERY

for their labor

needs in the 18th century. After the 1660s, indentured ser-

vants were almost always European, and the majority sur-

vived their indenture. As late as the 1770s, more than 40

percent of immigrants to America were indentured ser-

vants. Enlightened ideals regarding liberty, the American

Revolution (1775–83; see A

MERICAN

R

EVOLUTION AND

IMMIGRATION

), and the growth of industrial capitalism

combined to undermine the system of indentured servi-

tude, which finally faded out around 1830.

Further Reading

Coldham, Peter Wilson. Emigrants in Chains: A Social History of

Fo

rced Emigration to the Americas of Felons, Destitute Children,

Political and Religious Non-Conformists, Vagabonds, Beggars and

Other Undesirables, 1607–1776. Baltimore: Genealogical Pub-

lishing, 1994.

E

mmer, P. C., and E. van den Boogaart, eds. Colonialism and Migra-

tion: Indentur

ed Labor before and after Slavery. Dordrecht,

Netherlands: N

ijhof, 1986.

Galenson, David W. White Servitude in Colonial America: An Economic

A

nalysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Grabbe, H

ans-Jurgen. “The Demise of the Redemptioner System in

the United States.” American S

tudies [West Germany] 29, no. 3

(1984): 277–296.

K

ettner, James H. The Development of American Citizenship,

1608–1870. Chapel H

ill: University of North Carolina Press,

1978.

S

mith, A. E. Colonists in Bondage. Chapel Hill: University of North

Car

olina P

ress, 1947.

Vachon, André. Dreams of Empire: Canada before 1700. Ottawa: Pub-

lic Ar

chiv

es of Canada, 1982.

Indian immigration (Asian Indian

immigration)

According to the 2000 U.S. census, 1,899,599 Americans

claimed Asian I

ndian descent. Although most w

ere Hindus

and Muslims, almost 150,000 were Christians from south-

ern India. Asian Indians were spread throughout the coun-

try, though around 70 percent lived in New York,

Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Texas, Michigan, Illinois, Ohio,

and California. As a group, Indians were among elite immi-

grants, generally well educated and often arriving with cap-

ital to invest in business or industry. At the turn of the 21st

century, approximately 4 percent of American medical doc-

tors were foreign-born Indians or of Indian descent. Accord-

ing to the 2001 Canadian census, approximately 100,000

Canadians claimed either South Asian ancestry or descent

from an Indian ethnic group, while 713,330 identified them-

selves as East Indian. Indians are widely spread throughout

Canada. Early settlement centered in British Columbia; after

1960, T

ORONTO

was the favored destination.

Exact numbers of immigrants are difficult to ascertain,

as the term Indian applies to more than a dozen ethnic

gr

oups and has been used to r

efer to two distinct political

entities. From the late 18th century until 1947, India com-

prised all the diverse religious and ethnic groups governed

directly or indirectly as part of British imperial territory

between Afghanistan and Burma (present-day Myanmar).

This included large and distinct communities of Pakistanis,

Punjabis, Bengalis (Bangladeshis), Sinhalese, and Tamils,

among others. Although the term Hindu was frequently

used into the 1960s in refer

ence to migrants fr

om the whole

of British India, it was in many cases inaccurate, as Pakista-

nis were most often Muslims, Punjabis either Muslims or

Sikhs, and Bengalis either Hindus or Muslims. The “Indian”

peoples spoke a variety of languages, including Gujurati,

Urdu, Hindi, Tamil, Punjabi, Bengali, and Telegu. When

Britain withdrew from its Indian empire in 1947, predomi-

nantly Muslim territories of the Sind and Punjab in the west

and eastern Bengal and Assam, a thousand miles to the east,

were collectively granted independence as the new state of

Pakistan. The predominantly Hindu island of Ceylon (Sri

145INDIAN IMMIGRATION 145

Lanka) was granted independence in the following year.

What remained became the modern country of India, the

seventh-largest country in the world by landmass, with

1,146,600 square miles, and second only to China in popu-

lation, with just over 1 billion people. It incorporates cli-

matic and vegetative patterns ranging from the high

Himalayan Mountains in the north to the deserts of

Rajasthan in the northwest to the rain forests of Assam in

the northeast. With mixed ethnic and religious populations,

a peaceful division of land proved impossible, and more

than 1 million people died in communal violence surround-

ing the partition. About 80 percent of Indians are Hindus,

and 14 percent Muslims. Ethnic and religious tensions in

India and along the border with Pakistan remain high, pro-

viding a powerful impetus for some Indians to emigrate.

There is evidence of Indian sailors and adventurers set-

tling in the United States as early as the 1790s, but they did

not begin to migrate to North America in significant num-

bers until around the turn of the 20th century. They then

generally came as part of two groups: poor laborers or elites.

With the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1834,

Indian labor became an important commodity. It has been

estimated that between 1834 and 1934, some 30 million

Indians indentured themselves for terms of labor in eastern

and southern Africa, the Caribbean, Southeast Asia and

western Europe. Between 1904 and 1911, 6,100 Indians

immigrated to the United States, living almost exclusively

on the West Coast. Many were Punjabi Sikhs who had first

immigrated to western Canada but found work in lumber

mills and on railway gangs in California and the Pacific

Northwest. The largest concentrations were in the San

Joaquin, Sacramento, and Imperial Valleys of California.

Provisions of the racially restrictive A

LIEN

L

AND

A

CT

(1913), I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

(1917) and National Origins

and Quota Act (1924), along with the 1923 Supreme Court

ruling that Indians were ineligible for naturalized citizen-

ship, made it impossible for them to assimilate, and eco-

nomic depression made it unattractive for further

146146 INDIAN IMMIGRATION

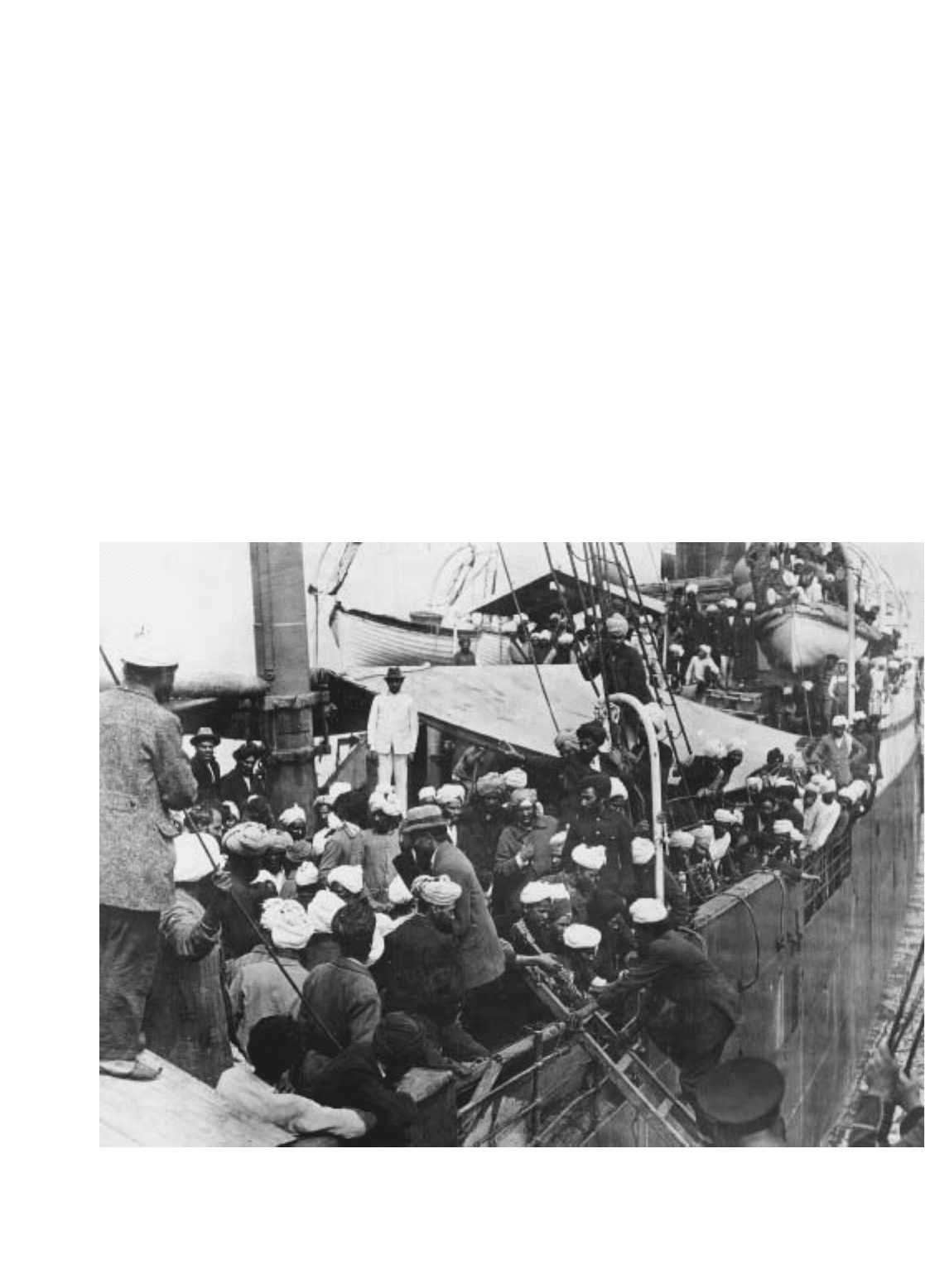

Indian immigrants on board the Komogata Maru in English Bay,Vancouver, British Columbia, 1914. Indian businessman Gurdit Singh

sponsored the voyage for 376 East Indian workers sailing from Shanghai, openly challenging restrictive Canadian legislation. After

a two-month court battle, the Komogata Maru was forced to leave Canadian waters.

(National Archives of Canada/PA-34014)

immigrants to come. As a result, Sikhs and Muslims often

took Mexican wives, creating a significant “Mexidu” culture

that consisted of more than 300 families. More than 6,000

Indians were either deported or chose to leave the United

States so that by 1940, fewer than 2,500 “Hindus” were liv-

ing the country. Although illegal immigration through Mex-

ico may have added several thousand more, the total

number of residents was never more than a few thousand.

Among the elite groups, teachers (swamis), students, and

merchants were most common, representing the well edu-

cated from many ethnic groups, including Bengalis. Stu-

dents who came to the United States were frequently

involved with the Indian nationalist movement, but their

numbers were never large. The renewal of immigration of

Indians under provisions of the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

(1965) led to increased numbers but

was of a wholly different character than the earlier migra-

tion. Most were not Sikhs, few settled in California or the

West, and almost none were agriculturalists. The majority of

recent Indian immigrants were well-trained professionals

and entrepreneurs, who were often overqualified for the jobs

they held. Between 1992 and 2002, about 480,000 Indians

immigrated to the United States.

Many Sikhs sought opportunities afforded them as sub-

jects of a British Empire that stretched across the world.

They often served as soldiers or employees of steamship

companies, and many eventually settled in Canada. The first

significant wave of Indian immigrants came between 1903

and 1918, when more than 5,000, mainly Sikhs, arrived. In

the early 20th century, this led to fairly homogenous Indian

communities in western Canada, where most of the men

had originally settled before bringing over their families.

Denied the right to participate in the national political pro-

cess, Indians focused on local community organization and

loudly protested their denial of rights. By World War I

(1914–18), many community leaders were members of the

Socialist Party and in some way affiliated with the revolu-

tionary Ghadar Party which sought the overthrow of the

British in India. As the organization was infiltrating the

United States, it was crushed in Canada and many of its

leaders forced out of the country. With the breakup of the

old British imperial system after World War II (1939–45),

newly independent countries had to negotiate treaties pro-

viding for regular immigrant status. The Canadian govern-

ment made some gestures toward India but major reform

was slow in coming.

In 1947, Indians in Canada finally were enfranchised.

The I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

(1952) provided for reunification

of immediate family members, and the subsequent order-in-

council (P.C. 1956-785) allowed an annual quota of 150

Indians beyond those eligible under the category of imme-

diate-family sponsorship. When Canada relaxed social and

ethnic barriers in the early 1960s, more South Indians began

to immigrate, most frequently choosing Ontario or Quebec

for settlement. By 1969, India became one of the top 10

source countries for Canadian immigration. Immigration

peaked in the early 1970s, after which an economic down-

turn in Canada led to more restrictive policies based on

desired skills. By the turn of the 21st century, the Indian

community in Canada included much ethnic diversity and

numerically had shifted from west to east. In 2001, 314,685

Indian immigrants were living in Canada, with more than

235,000 born in India and most of the rest in Fiji, Trinidad

and Tobago, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. About 92 per-

cent arrived after 1971, 156,000 between 1996 and 2001

alone. More than three-quarters of all immigrants came

under family reunification provisions. In the 1990s, how-

ever, increasing ethnic and religious tensions in India led to

a greater concern for political refugees. Whereas only six of

4,115 refugee visas were granted between 1977 and 1988,

the following 10 years (1989 and 1998) saw 2,621 claims

granted by the Immigration and Refugee Board, 27 percent

of all claims received.

See also B

ANGLADESHI IMMIGRATION

; P

AKISTANI

IMMIGRATION

;S

OUTH

A

SIAN IMMIGRATION

;S

RI

L

ANKAN

IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Agarwal, Pankaj. Passage from India: Post-1965 Indian Immigrants

and Their Childr

en—Conflicts, Concerns, and Solutions. Palos

Ver

des, Calif.: Yuvati Publications, 1991.

Barrier, N. Gerald, and Verne A. Susenbery, eds. The Sikh Diaspora:

Migration and the Experience beyond Punjab

. Columbia, Mo.:

S

outh Asia Publications, 1989.

Birbalsingh, F

rank, ed. Indenture and Exile: The Indo-Caribbean Expe-

rience. Toronto: Tsar P

ublications, 1989.

Buchignani, Norman, Doreen M. Indra, with Ram Srivastava. Con-

tinuous Journey: A Social H

istory of South Asians in Canada.

Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1985.

Chandrasekhar

, S., ed. F

rom India to America: A Brief History of Immi-

gration. La J

olla, Calif.: Population Review, 1986.

Daniels, R

oger. History of Indian Immigration to the United States: An

Interpretative Essay

. New York: Asia Society, 1989.

G

ibson, M. A. Accommodation without Assimilation: Sikh Immigrants

in an American H

igh School. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University

Press, 1989.

H

elw

eg, A. Wesley, and Usha M. Helweg. An Immigrant Success Story:

East I

ndians in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylva-

nia Press, 1990.

J

ensen, J

oan M. Passage from India: Asian Indian Immigrants in North

America. N

ew Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988.

Johnston, Hugh J. M. The East Indians in C

anada. Ottawa: Canadian

Historical Association, 1984.

J

oy, Annamma. Ethnicity in Canada: Social Accommodation and Cul-

tural P

ersistence among the S

ikhs and the Portuguese. New York:

AMS P

ress, 1989.

La Brack, Bruce. “South Asians.” In A N

ation of Peoples: A Sourcebook

on A

merica’s Multicultural Heritage. Ed. Elliott Robert Barkan.

Westpor

t, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999.

147INDIAN IMMIGRATION 147

Leonard, Karen Isaksen. Making Ethnic Choices: California’s Punjabi

Mexican Americans. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992.

Lessinger, Johanna. From the Ganges to the Hudson. Needham Heights,

M

ass.: Allyn and Bacon, 1995.

Petivich, Carla. The Expanding Landscape: South Asians in the Dias-

por

a. Chicago: M

anohar, 1999.

Sara, P

armatma. The Asian Indian Experience in the United States.

Cambridge, Mass.: Schenkman Books, 1985.

S

heth, P

ravin. Indians in America: One Stream, Two Waves, Three Gen-

erations. J

aipur, India: Rawat Publications, 2001.

Tatla, D

arshan Singh. Sikhs in North America: Sources for the Study of

Sikh Community in N

orth America and an Annotated Bibliography.

New York: Greenwood Press, 1991.

V

an der

Veer, Peter, ed. Nation and Migration: The Politics of Space in

the South Asian Diaspor

a. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylva-

nia Pr

ess, 1995.

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW,

Wobblies)

Founded in 1905, the Industrial W

or

kers of the World

(IWW) was the most important of the radical labor organi-

zations that operated in the United States and Canada.

Many unskilled immigrants initially joined, then left as they

became better situated in the labor market. Though immi-

grants often rejected the IWW for fear of losing their jobs in

strike actions, the organization worked directly to foster

interethnic cooperation. During World War I (1914–18; see

W

ORLD

W

AR

I

AND IMMIGRATION

), membership rose dra-

matically, with a corresponding wave of strikes and labor

militancy. Increasingly, both domestic and foreign workers

who opposed the war and believed they were not being well

served by traditional craft unions joined the IWW. This led

to further tensions, as industrialists and politicians sought to

establish links between German activity and the radical

labor movement. In 1918, the Canadian government made

the IWW and 13 socialist or anarchist organizations illegal.

When a move to join the Communist International was nar-

rowly defeated in 1920, the organization began to disinte-

grate, reflecting in part the immigrant move toward

mainstream politics and assimilation.

See also

LABOR ORGANIZATION AND IMMIGRATION

,

TERRORISM AND IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Dubofsky, Melvyn. We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers

of the W

orld. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1969.

148148 INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD

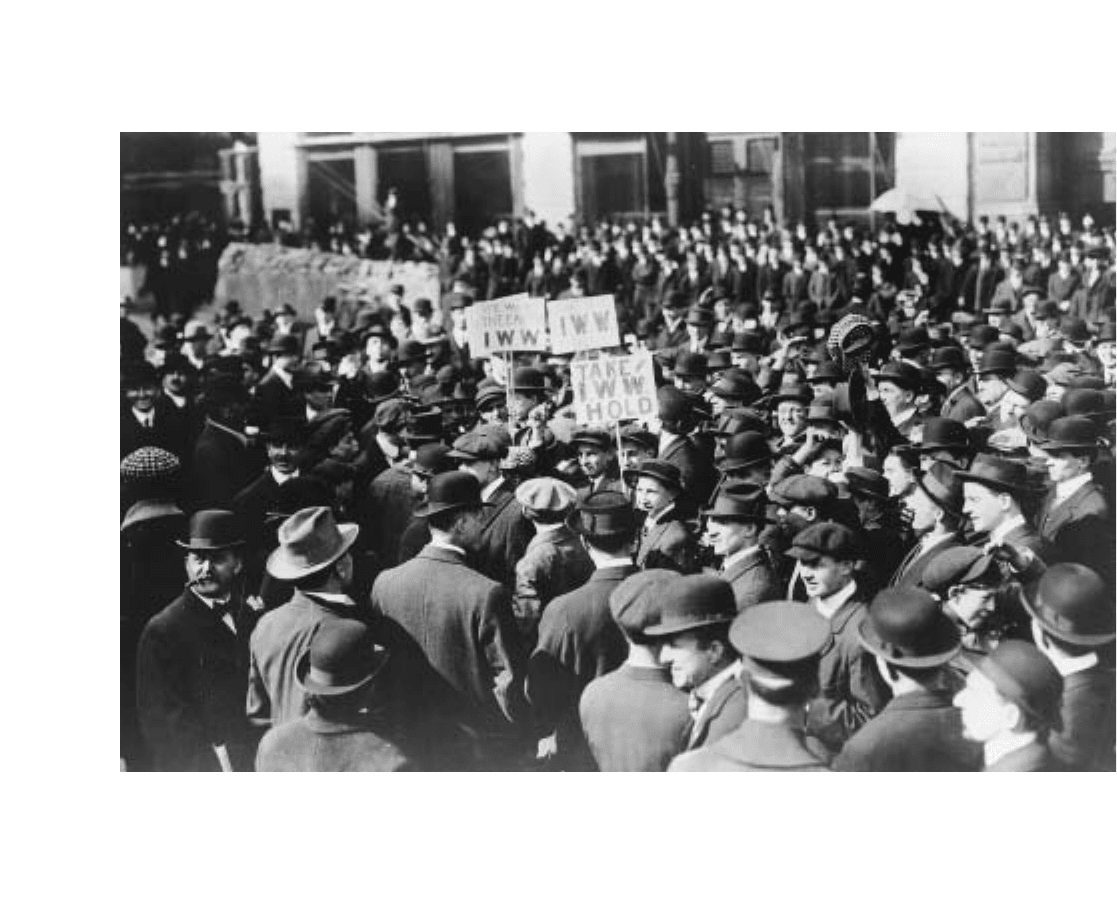

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) demonstration in New York City in 1914.The IWW was the most important radical

labor union in the United States and Canada, and it attracted many immigrants who believed that their interests were not taken

seriously by traditional labor unions.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-30519])

Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the

State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925. New York:

Cambridge Univ

ersity Press, 1987.

Renshaw, Patrick. The

Wobblies: The Story of Syndicalism in the United

S

tates. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1967.

Rober

ts, Barbara. Whence They Came: Deportation from Canada,

1900–1935. Ottawa: U

niversity of Ottawa Press, 1988.

R

obin, Martin. Radical Politics and Canadian Labour, 1890–1930.

Kingston, Canada: Industrial Relations Centre, Queen’s Univer-

sity

, 1968.

Inouye, Daniel K. (1924– ) politician

Hawaii’s first U.S. congressman and the first member of

Congress of Japanese descent, Daniel Inouye has repre-

sented, for more than 40 years, the patriotism of Japanese

Americans. Committed to a strong national defense, he

fought for compensation to Japanese Americans who had

been imprisoned in internment camps during World War

II (1939–45; see J

APANESE INTERNMENT

, W

ORLD

W

AR

II).

The son of Japanese immigrants, Inouye was born in

Honolulu and graduated from the public school system

there. As a freshman in college, in 1943, he enlisted in the

442nd Regimental Combat Team and fought in Italy,

where he lost his right arm and earned the Distinguished

Service Cross (upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 2000).

Having experienced the discrimination then common

against Japanese Americans, he determined to work on

behalf of social change and to that end earned a law degree

from George Washington University. Inouye won a Demo-

cratic seat in the Hawaiian territorial legislature in 1954.

After serving in the U.S. House of Representatives follow-

ing Hawaiian statehood (1959–63), he was elected seven

times as U.S. senator from Hawaii (1963–2005). In the

late 1970s, he supported the efforts of the Japanese Amer-

ican Citizens’ League, which lobbied Congress to establish

the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment

of Citizens (CWRIC). As a result of the league’s efforts, the

Civil Liberties Act was signed by President Ronald Reagan

in 1988, providing an apology for the internment and

$20,000 for each survivor then alive. Speaking in favor of

the measure before the Senate on April 20, 1988, Inouye

observed that the CWRIC found no documented cases of

espionage or sabotage by Americans of Japanese descent

and reminded senators that “proportionately and percent-

agewise,” more Japanese Americans had served during

World War II than non-Japanese, despite the fact that they

were restricted to ethnic units.

Further Reading

“Biography of Daniel K. Inouy

e.” United States Senate. Available on-

line. URL: http://inouye.senate.gov. Accessed May 13, 2004.

Inouye, Daniel K., with Lawrence Elliot. Journey to Washington. Engle-

wood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1967.

International Ladies’ Garment Workers’

Union

(ILGWU)

Founded in 1900 in New York City, the International Ladies’

Garment

Workers’ Union (ILGWU) was remarkably suc-

cessful in forcing adoption of sanitary codes and safety regu-

lations and achieving better pay during the first two decades

of the 20th century. Comprising mostly women immigrants,

the organization flourished in eastern cities, though there were

local unions elsewhere. The majority of early members were

Jewish and Italian, establishing a pattern for the garment trade

to be dominated by the newest immigrants. The union’s great-

est early successes were the “Uprising of 1909,” in which

20,000 shirtwaist makers staged a 14-week strike, and the

“Great Revolt,” which saw 60,000 garment workers win “The

Protocol of Peace.” The organization, increasingly an owners’

union, continued to function under the original name, pro-

viding clear working standards and impartial arbitration of

grievances. In 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, in which 146

workers died as flames engulfed an unsafe and unaffiliated

workshop, focused national attention on the plight of gar-

ment workers. In the same year, the Independent Cloakmak-

ers Union of Toronto became the first Canadian union to

affiliate with the ILGWU.

In 1914, a similar organization known as the Amalga-

mated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) was formed,

with an affiliated branch established in Montreal in 1917. In

1976, the ACWA merged with the Textile Workers Union of

America to form the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile

Workers Union, which in turn merged with the ILGWU in

1995 to form the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and

Textile Employees (UNITE), representing more than

250,000 American and Canadian workers. By the 1980s,

union membership was largely from the Caribbean Basin,

South America, and East Asia. International visibility of the

garment trade was once again heightened in 1996, with rev-

elations of sweatshop conditions found in the manufacture

of television personality Kathie Lee Gifford’s clothing line.

Throughout the late 20th and early 21st century, UNITE

took an increasingly activist role in international politics,

joining with environmental and student groups to protest

international working conditions and the policies of such

international economic groups as the World Trade Organi-

zation.

Further Reading

Lorwin, Lewis Levitzki. The Women’s Garment Workers: A History of the

International Ladies’ Gar

ment Worker’s Union. New York: B. W.

Huebsch, 1924.

S

tein, Leon. Out of the Sweatshop: The Struggle for Industrial Democ-

racy. New Y

ork: Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co., 1977.

Tyler, Gus. Look for the Union Label: A History of the International

Ladies’ G

arment Workers’ Union. New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1995.

UNITE! Web site. Av

ailable online. URL: http://www.uniteunion.

org/. Accessed May 13, 2004.

149INTERNATIONAL LADIES’ GARMENT WORKERS’ UNION 149

Waldinger, Roger D. Through the Eye of the Needle: Immigrants and

Enterprise in New York’s Garment Trades. New York: New York

Univ

ersity Press, 1986.

Iranian immigration

During the 1990s, Iranians formed the largest immigrant

group from the Middle East in both the United States and

Canada. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 338,266 Americans and 88,220

Canadians claimed Iranian ancestry. By far the greatest con-

centration of Iranians in the United States was in California;

about half of all Canadian Iranians lived in T

ORONTO

.

Iran, known throughout much of its history as Persia,

occupies 630,900 square miles, with Turkey and Iraq on the

west; Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and the Caspian

Sea on the north; Afghanistan and Pakistan on the east; and

the Persian Gulf and Arabia Sea on the south. In 2002, the

population was estimated at 66,128,965. The people are eth-

nically divided between Persians (51 percent), Azerbaijani

(24 percent), Gilaki/Mazandarani (8 percent), Kurds (7 per-

cent), and Arabs (3 percent). Iran is the only country in the

world with a government under the control of Shia Muslims,

who comprise 89 percent of the population; 10 percent are

Sunni Muslims. From their homeland in Iran, the Persians

created one of the world’s largest empires between the 6th

and 4th centuries

B

.

C

., when they were conquered by Alexan-

der the Great. After more than 500 years under a Greek-

speaking government, the native Sasanians returned to power

between

A

.

D

. 226 and 640, when Arab Muslims conquered

the region. Unlike other Islamic regions, Iran’s population

was largely of the Shiite branch of Islam, which held that

only descendants of Muhammad should rule or exercise high

spiritual authority. The Safavid dynasty reached a peak of

political influence and cultural development in the 16th and

17th centuries but steadily declined in power with the advent

of European expansion. During the latter years of the Qajar

dynasty (1779–1921), Iran’s economy was largely controlled

by Russians in the north and British in the south. Moham-

mad Reza Pahlavi, who came to power as the shah of Iran in

1941 alienated religious leaders by his campaign of rapid

modernization. The shah was overthrown in 1979 and

replaced by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who estab-

lished a fundamentalist Islamic republic and waged war over

border territories with Iraq throughout the 1980s. Muslim

extremists, angered by American support for the shah and

supported by the Iranian government, also seized a group of

American embassy workers in November 1979, holding

them for 444 days. Not only was there an anti-Iranian back-

lash in the United States, with the embassy closed in Tehran

it became necessary for potential immigrants to travel to a

third country to obtain visas. During the 1990s, the Iranian

government gradually became more moderate. Fundamen-

talist clerics continued to exert widespread influence how-

ever. In 2004 they declared several hundred reformers ineli-

gible to stand for parliament, thus allowing fundamentalists

to regain control of the legislature.

It is impossible to say how many Iranians may have

immigrated to North America prior to World War II

(1939–45), but the number was extremely small. Almost

everyone from the Middle East was classified as an Arab

prior to 1900, and frequently as a Syrian until 1930. The

first significant group of Iranian immigrants came between

1950 and 1977, when about 35,000 came to the United

States. This number is misleading, however, as nearly

400,000 nonimmigrants (visitors and students) also arrived

during this period, many of whom eventually stayed in the

United States. The fall of the pro-Western government of

the shah in 1979 gave new impetus to educated and mod-

ernized Iranians to immigrate—in 1990, half the Iranian

population 25 years or older had at least a bachelor’s degree.

About 200,000 sought refuge in the United States between

1979 and 2000, and eventually almost 60,000 were granted

refugee or asylee status. In 2000 and 2001 alone, almost

12,000 Iranian refugees were admitted. A substantial num-

ber of them were from minority groups, including Assyri-

ans and Armenians (most of whom were Christians), Kurds,

and Jews. Altogether almost 117,000 Iranians were admitted

to the United States between 1992 and 2002.

Iranians first came to Canada in significant numbers

after 1964 and then after 1978. Most of these several thou-

sand immigrants were well-trained professionals or students,

in some way tied to the rapid modernization plans of the

shah. Many were doctors, and most blended into Canadian

professional society. After the Islamic revolution in 1979,

however, most immigrants were fleeing persecution. Their

numbers included supporters of the old regime, but also

many students, feminist groups, and other reformers who

had supported the revolution in order to oust the shah but

whose modernist views were not tolerated by the new fun-

damentalist regime. In 1986 and 1987, for instance, the

government dismissed 11,000 government employees,

mostly women, in a “purification” campaign. More than 90

percent of Iranian immigrants to Canada came between

1981 and 2001. Beginning in 1996, Iran broke into the top

10 source countries for Canadian immigration. Between

1996 and 2002, more than 6,400 Iranians immigrated

annually, including more than 4,200 refugees between 2000

and 2002.

Further Reading

Ansari, Abdolmaboud. Iranian Immigrants in the United States: A Case

Study of Dual M

arginality. New York: Associated Faculty Press,

1988.

———. The Making of the Iranian Community in America. New York:

P

ardis Press, 1992.

Bill, James A. The Eagle and the Lion: The

T

ragedy of American-Ira-

nian Relations. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University P

ress, 1988.

150150 IRANIAN IMMIGRATION

Bozorgmehr, Mehdi. “Diaspora in the Post-Revolutionary Period.” In

Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 7. Costa Mesa, Calif.: Mazda Publish-

ers, 1900.

———, ed. “I

ranians in America.” (special issue). Iranian Studies 31,

no. 1 (1998): 3–95.

Bozorgmehr, Mehdi, and George Sabagh. “High Status Immigrants: A

Statistical Profile of Iranians in the United States.” Ir

anian Stud-

ies 21, nos. 3–4 (1988): 4–34.

Fathi, Asghar

, ed. Iranian Refugees and Exiles since Khomeini. Costa

Mesa, Calif.: M

azda Press, 1991.

Khalili, Laleh. “Mixing Memory and Desire: Iranians in the United

States.” May 13, 1998. The Iranian. Available online.

http://www

.iranian.com/Features/May98/Iranams/index.html.

Accessed February 24, 2004.

Moallem, Minso. “Pluralité des rapports sociaux: similarité et dif-

férence. Le cas des Iraniennes et Iraniens au Québec.” Ph.D.

thesis, University of Montreal, 1989.

Moghaddam, Fathali M. “Individual and Collective Integral Strategies

among Iranians in Canada.” International Journal of Psychology 22

(1987): 306–314.

N

afici, H

amid. “The Poetics and Practice of Iranian Nostalgia in

Exile.” Diaspora 1, no. 3 (Winter 1991): 285–302.

Shadbash, Sh

aram. “Iranian Immigrants in the United States: The

Adjustment Experience of the First Generation.” Ph.D. thesis,

Boston University, 1994.

Iraqi immigration

Unlike some other Muslim groups, Iraqis had little exposure

to Western culture before immigrating to North America in

the wake of the first Persian Gulf War (1991) and therefore

had more difficulty assimilating. According to the U.S. cen-

sus of 2000 and the Canadian census of 2001, 37,714

Americans and 26,655 Canadians claimed Iraqi ancestry.

U.S. centers of settlement include the greater D

ETROIT

area,

C

HICAGO

, and L

OS

A

NGELES

. About half of Iraqis in

Canada live in T

ORONTO

.

Iraq is the easternmost Arab nation, occupying 167,400

square miles. It is bordered by Jordan and Syria on the west,

Turkey on the north, Iran on the east, and Kuwait and Saudi

Arabia on the south. In 2002, the population was estimated

at 23,331,985. The people are ethnically Arabs (65 percent),

Kurds (23 percent), Azerbaijani (5.6 percent), and Turk-

men (1.2 percent). More than 96 percent of Iraqis are Mus-

lims, though there are clear divisions between the 62 percent

Shia and 34 percent Sunni. The region known to the Greeks

as Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates

Rivers, is the heart of Iraq. The well-watered river banks pro-

vided abundant crops and led to the development of the

world’s first civilization around 3500

B

.

C

. A succession of

empires ruled by Arabs, Persians, Indo-Europeans, and

Greeks controlled the region prior to its conquest by Mus-

lim armies in the 630s. Baghdad was one of the most

advanced and sophisticated cities in the world under the

Abbasid caliphate in the ninth century but gradually

declined in the face of Islamic divisions and eventual Mon-

gol conquest in 1258. The Ottoman Turks ruled Iraq from

the 16th century to 1917. After World War I (1914–18),

Iraq was a territory mandated to British oversight and even-

tually gained full independence in 1932. After considerable

political turmoil, including attempted Kurdish revolts

(1945, 1974) and Communist control of the central gov-

ernment (1973), the Baathist Saddam Hussein gained office

in 1979. Iraqis benefitted in the 1970s and 1980s from con-

siderable oil revenues and resulting social improvement, but

Hussein also took the country to war and brutally repressed

all political opponents. In 1980, he launched an invasion of

Iran, which led to a devastating eight-year war and the death

of some 1 million Iraqis. In August 1990, Iraq invaded

Kuwait, leading to U.S. involvement and the first Persian

Gulf War (1991) in which the Iraqi army was largely

destroyed. The terrorist attacks of S

EPTEMBER

11, 2001,

heightened U.S. suspicions regarding Iraqi support for al-

Qaeda and other terrorist organizations. This combined

with Iraqi evasion of required United Nations inspections

regarding the development of weapons of mass destruction,

resulted in a U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. Saddam

Hussein was captured by American forces on December 13,

2003. In April 2004 Iraqi leaders determined to put Hussein

on trial for crimes committed during his rule, though pub-

lic proceedings had not begun before the end of the year. On

June 28, 2004, the U.S.-led coalition returned sovereignty

to an Iraqi interim government, with nationwide elections

scheduled for January 2005. About 140,000 U.S. troops

remained in Iraq at the end of 2004.

Prior to World War II (1939–45), only a few hundred

Iraqis immigrated to North America, most from the privi-

leged class and for economic opportunities. Many of these

were minority Chaldean Christians, who began to settle in

and around Detroit as early as 1910. By the end of World

War II, the Chaldean population in Detroit numbered

about 1,000. Although a few students came for study after

the war, immigration remained small until the 1970s, when

political events drove many dissidents from the country

under the flag of pan-Arab unity, Hussein crushed a Kurdish

revolt in 1975, and in 1979 began a systematic suppression

of communists, Kurds, Shia Muslims, and Baathists who

had fallen out of favor. About 300,000 Shias were driven to

Iran, and many of those eventually made their way to the

United States. The first extensive immigration, however,

came only after the 1991 Persian Gulf War, when about

10,000 Iraqi refugees were admitted to the United States,

mostly Kurds and Shiites who had assisted or sympathized

with the U.S.-led war. Between 1992 and 2002, about

50,000 Iraqis immigrated to the United States, many as

refugees. Between 1996 and 2001 alone, 14,000 Iraqi

refugees were admitted.

On April 9, 2003, hundreds of Iraqis celebrated in

the streets of Dearborn, Michigan (suburban Detroit),

151IRAQI IMMIGRATION 151

celebrating the coalition capture of Baghdad and the over-

throw of Hussein. In 2004, many recent Iraqi immigrants

waited to see if conditions in the country would stabilize

following the restoration of sovereignty to a new Iraqi gov-

ernment in June 2004, with an eye to returning to their

home country.

Iraqi immigration to Canada was largely the result of

the disruptions of the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s and the

two Persian Gulf wars of 1991 and 2003. Between 1945 and

1975, there were no more than 200 Iraqi immigrants. With

the rise of Hussein and the intensification of political perse-

cution after 1979, a small but steady stream of dissidents left

the country, with almost 6,500 coming to Canada by 1992.

Of 25,825 Iraqis immigrants in Canada in 2001, only 2,230

(8.6 percent) came before 1981. With constant war and the

brutal suppression of Kurds and Shiites by the Iraqi govern-

ment, immigration increased in the 1990s. Between 1991

and 2001, almost 20,000 Iraqis immigrated to Canada.

See also A

RAB IMMIGRATION

;I

RANIAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Abraham, N., and S. Y. Abraham. Arabs in the New World: Studies on

Ar

ab-American Communities. Detroit: Center for Urban Studies,

Wayne S

tate University, 1983.

Abu-Labar, Baha. An Olive Branch on the Family Tree: The Arabs in

C

anada. T

oronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1980.

Elkholy

, Abdo A. The Arab Moslems in the United States: Religion and

Assimilation. N

ew Haven, Conn.: College and University Press,

1966.

Haddad, Y

v

onne Yazbeck. The Muslims of America. New York: Oxford

Univ

ersity Press, 1991.

Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck, and Jane Idleman Smith, ed. Muslim Com-

munities in N

or

th America. Albany: State University of New York

Press, 1994.

McCarus, E

rnest, ed. The Development of Ar

ab-A

merican Identity. Ann

Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Makiya, Kanan. Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq. Updated

ed. B

er

keley: University of California Press, 1998.

Metcalf, Barbara Daly. Making Muslim Space in N

or

th America and

Europe. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Sengstock, M. C. Chaldean A

mericans: Changing Conceptions of Ethnic

Identity. New Y

ork: Center for Migration Studies, 1982.

S

uleiman, Michael W. Arabs in America: Building a New Future.

Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000.

Tripp, Charles. A History of I

raq. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2000.

Waugh, Earle H., et al., eds. Muslim Families in North America.

Edmonton, Canada: Univ

ersity of Alberta Press, 1991.

Irish immigration

The Irish were the first of Europe’s many impoverished peo-

ples to seek economic advantages in the New World in large

numbers in the 19th century, providing one of the great

immigration streams to both Canada and the United States.

According to the 2000 U.S. census and the 2001 Canadian

census, 30,528,492 Americans and 3,822,660 Canadians

claimed Irish descent. Most Irish immigrants originally set-

tled in major urban centers, most prominently N

EW

Y

ORK

City, B

OSTON

, P

HILADELPHIA

, M

ONTREAL

, and Q

UEBEC

.

Because significant Irish immigration began early in the

17th century and continued for 300 years under a wide vari-

ety of circumstances, the Irish are now spread throughout

North America and have become an integral part of Ameri-

can and Canadian culture.

The island of Ireland covers a little more than 32,000

square miles in the North Atlantic Ocean, about 80 miles

west of Great Britain. In ancient times, it was inhabited by

Celtic peoples, and the land was usually divided among mul-

tiple kings. The Irish were converted to Christianity in the

fifth century by St. Patrick and for hundreds of years pro-

duced outstanding Christian scholars and missionaries. By

the 12th century, English kings established a foothold near

modern Dublin and gradually extended their control over

the eastern half of the island. During the 1640s, most of Ire-

land was brought under English control by Oliver Cromwell,

leading to a diffuse but persistent Irish resistance. Beginning

in the 15th century, large numbers of Scots and English citi-

zens were resettled in Ireland, mostly in the six counties of

the north, on lands confiscated from the rebellious Irish

nobility (see U

LSTER

). These settlers formed the basis of the

Protestant Ascendancy, a minority population that gradually

came to view itself as Irish. By the late 18th century, many

members of the Protestant Ascendancy were themselves call-

ing for either self-government or complete independence

from Great Britain. After the rebellion of 1798, Ireland was

brought under more direct British control with the creation

of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801).

Throughout the 19th century, resolution of the Irish prob-

lem was continually hampered by two closely related issues:

the question of the traditional unity of the island of Ireland

and the cultural and religious division of the land between

the Protestants of the north and the Roman Catholics of the

south. The Irish Civil War (1919–21) led to the division of

the land into the Republic of Eire—making up 27,133

square miles, or about 85 percent, of the island, fully inde-

pendent from 1937, and Northern Ireland—the six counties

of the north (5,451 square miles), which remained legisla-

tively linked to Great Britain. Eire’s population of 3.8 million

(2001) was 92 percent Roman Catholic; 45 percent of

Northern Ireland’s 1.7 million people (2001) were Roman

Catholic. With Catholic population growth in the north

steadily outstripping that of Protestants, it was expected that

Catholics would constitute the majority population in the

north within a relatively short period of time, thus enhancing

the possibility that the island will be politically reunified.

Following the Protestant Reformation of the 16th cen-

tury, Irish exiles, revolutionaries, and dispossessed

Catholics frequently immigrated to Spain, France, and the

152152 IRISH IMMIGRATION

Low Countries. In the 17th century alone, it has been esti-

mated that there were 35,000 Irish soldiers in the French

army. These, along with Irish merchants employed by

France, made their way to N

EW

F

RANCE

in significant

numbers during the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1700,

there were 130 families either fully Irish or of mixed

Franco-Irish heritage. As political turmoil in Ireland

increased, France and New France remained popular desti-

nations for those with strong anti-British sentiments,

including a few disgruntled settlers from British colonies to

the south. Protestant immigrants, however, far outnum-

bered Catholic immigrants until the 1820s, and most

Protestants settled in the British colonies south of New

France. Between 1717 and 1775, more than 100,000 Pres-

byterian Scots-Irish settled in America, mainly because of

high rents or famine and most coming from families who

had been in Ireland for several generations. In the colonial

period, they were in fact usually referred to simply as Irish,

making it difficult to determine exact figures. Although

Scots-Irish filtered throughout the colonies, they most fre-

quently settled along the Appalachian frontier and largely

influenced the religion and culture of the frontier regions

as they developed. Altogether this represented the largest

movement of any group from the British Isles to British

North America in the 18th century. Many came as inden-

tured servants (see

INDENTURED SERVITUDE

), driven to

153IRISH IMMIGRATION 153

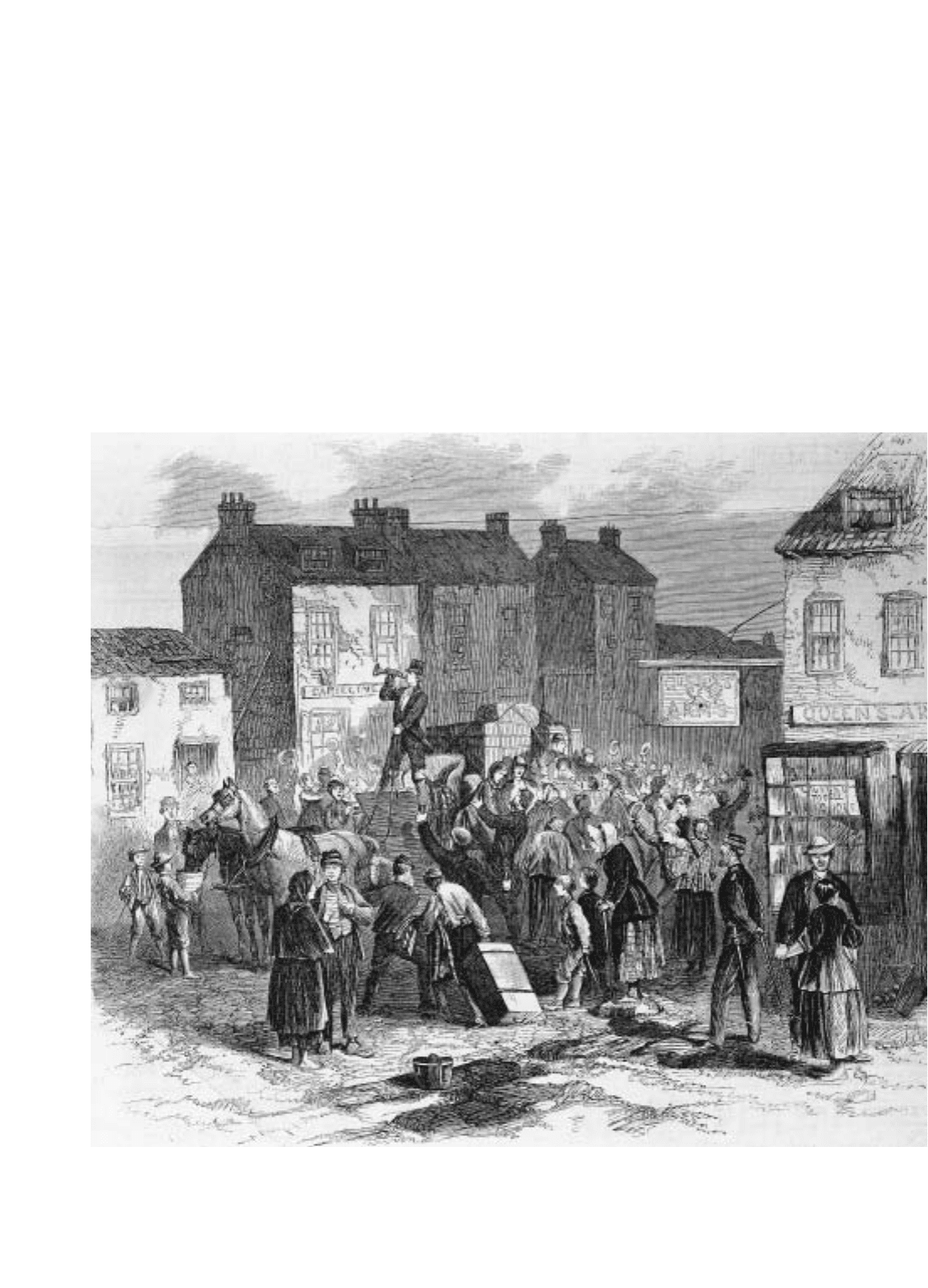

This illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 20, 1866, shows Irish immigrants leaving their home for America

on the mail coach from Cahirciveen, County Kerry, Ireland. With poverty rampant in Ireland, emigration was an attractive

alternative for many Irish well before—and long after—the great potato famine.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

[LC-USZ62-2022])