Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Pula, James. Polish Americans: An Ethnic Community. New York:

Twayne, 1995.

Radecki, Henry, with Benedykt Heydenkorn. A Member of a Distin-

guished F

amily:

The Polish Group in Canada. Toronto: McClel-

land and S

tewart, 1976.

Reczynska, Anna. For Bread and a Better Future: Emigration from

Poland to C

anada, 1918–1939. North York: Multicultural His-

tor

y Society of Ontario, 1996.

Renkiewicz, Frank, ed. The Polish Presence in Canada and America.

Tor

onto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1982.

Thomas,

William I., and Florian Znaniecki. The Polish Peasant in Europe

and America (1918–1920). N

ew York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1927.

Znaniecka-Lopata, H. Polish Americans. 2d rev. ed. New Brunswick,

N.J.: T

ransaction,

1994.

Zubrzycki, J. Soldiers and Peasants: The Sociology of Polish Immigration.

London: Orbis, 1988.

Portuguese immigration

The Portuguese have a long tradition of migration—to

Brazil, to North America, and to other European countries.

Yet of more than 1.5 million Portuguese emigrants between

1880 and 1960, less than 5 percent immigrated to North

America. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 1,177,112 Americans and

357,690 Canadians claimed Portuguese ancestry. The largest

concentrations of Portuguese Americans lived in New York

City, New England, and California. The largest Portuguese

communities in Canada were in Toronto and Montreal.

Portugal occupies 35,300 square miles on the Iberian

Peninsula in the extreme southwest of Europe, including the

Azores and Madeira Islands. Portugal faces the Atlantic on

the west and south and borders Spain on the north and east.

In 2002, the population was estimated at 10,066,253.

About 92 percent are ethnic Portuguese, with the rest of

diverse groups, mostly from Portugal’s African and Brazil-

ian empire. The chief religion is Roman Catholicism. Most

of the Iberian Peninsula was conquered by the Muslim

Moors in the eighth century, and local rulers spent the next

700 years driving them out. In the process, Henry of Bur-

gundy was made count of Portucale by King Alfonso VI of

Leon and Castile. By the 12th century, Portugal was recog-

nized as an independent kingdom, though it sometimes fell

under the political influence of its more powerful neighbor.

The Portuguese had a rich seafaring tradition and took the

lead in European exploration from the first decade of the

15th century. By the mid-16th century their empire

included Brazil, Guinea, Angola, Mozambique, Ceylon,

Formosa, and the East Indies. With a small population and

relatively few resources, Portugal declined as an international

power beginning in the 17th century. A republican revolu-

tion in 1910 drove out King Manoel II from power. For

much of the 20th century, Portugal was ruled by dictators or

military regimes. In 1982, the constitution was revised,

however, leading to greater political stability.

Portuguese immigration to the United States was in

many ways defined by Portugal’s unique geographical posi-

tioning in the Atlantic Ocean. The earliest substantial immi-

gration was from the colonial territory of Cape Verde,

followed by a new wave beginning in the 1870s from the

Azore Islands, then finally by a larger mainland and Madeira

Island group from about 1900 on. Once in the United

States, however, they tended to identify with the larger Por-

tuguese community. The first Portuguese known in the

Americas were Sephardic Jews who settled in Dutch New

Amsterdam (later New York City) in the 1650s. One Aaron

Lopez became a successful merchant after settling in New-

port, Rhode Island, in 1752, and through him a labor con-

nection was established that brought a small number of

Portuguese immigrants in the late 18th and early 19th cen-

turies. Most of these were whalers and seamen, including

Cape Verdeans of mixed black and Portuguese parentage,

who eventually settled in port towns, including New Bed-

ford and Edgartown in Massachusetts; on Long Island, in

New York; and Stonington, Connecticut (see C

APE

V

ERDEAN IMMIGRATION

). In the 1870s, significant num-

bers of Azorean Portuguese began to immigrate to the

United States, mainly for economic opportunities. Signifi-

cant numbers also immigrated to Hawaii (then the Sand-

wich Islands), where they worked on sugar plantations.

Portuguese immigration from the mainland began around

the turn of the 20th century, peaking at almost 90,000

between 1910 and 1920. Some Portuguese immigrants con-

tinued work in the fishing industry, but most settled in mill

towns, such as Fall River and Taunton, Massachusetts, or

worked as industrial laborers in Providence and Pawtucket,

Rhode Island.

Two pieces of legislation greatly reduced Portuguese

immigration in the 1920s. First, the I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of

1917 required a literacy test, which few Portuguese could

meet. Then the J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

of 1924 established a

low quota of emigrants from Portugal. Between 1931 and

1940, only 3,329 were admitted. In 1958, the United States

passed the Azorean Refugee Act, admitting 4,800 immi-

grants from the island of Fayal in the wake of volcanic erup-

tions and earthquakes. With passage of the I

MMIGRATION

AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

of 1965, which abolished racial

quotas, there was a great resurgence of Portuguese immigra-

tion. During the following 20 years, almost 200,000 came

to the United States. Between 1991 and 2002, the annual

average immigration from Portugal was little more than

2,000.

Portuguese immigration to Canada was much slower in

beginning, but the official numbers are generally considered

to be greatly understated. Portuguese fishermen had plied

Canadian waters since the 15th century but left no perma-

nent settlements. Between 1900 and 1950, only about 500

Portuguese came to Canada, many illegally. In the 1950s,

however, Canada openly sought agricultural and construc-

234 PORTUGUESE IMMIGRATION

tion workers, and the Portuguese were eager to fill the posi-

tions. Almost 140,000 settled in Canada in the 1960s and

1970s, the peak period of immigration. The majority were

single men from the Azores, and they lived in poor housing

in the inner cities. Although they gradually progressed in the

economy, most Portuguese remained out of the Canadian

cultural mainstream at the turn of the 21st century. From the

1970s on, Portuguese immigration to Canada steadily

declined. Of the 153,535 Portuguese immigrants in Canada

in 2001, about 43,000 came between 1981 and 2001.

Further Reading

Anderson, Grace, and David Higgs. “A Future to Inherit”: The Por-

tuguese Communities of Canada. T

oronto: McClelland and Stew-

art, 1976.

Car

doso, Manoel da Silveira. The Portuguese in America: 590

B

.

C

.–

1974: A Chronology and Fact Book. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana

Publications, 1976.

D

ias, E. Mayone. “Portuguese Immigration to the East Coast of the

United States and California: Contrasting Patterns.” In Portugal

in D

evelopment: Emigration, Industrialization, the European Com-

munity. Eds. T. C. Brueau, V. M P. Da Rosa, and A. Macleod.

O

ttawa: U

niversity of Ottawa Press, 1984.

Higgs, David. The Portuguese in Canada. St. John: Canadian Histori-

cal Association, 1982.

———, ed. Portuguese Migration in Global Perspective. Toronto: Uni-

v

ersity of

Toronto Press, 1990.

Joy, Annamma. Ethnicity in Canada: Social Accommodation and Cul-

tur

al P

ersistence among the Sikhs and the Portuguese. New York:

AMS Press, 1989.

Noivo, Edite. Inside E

thnic Families: Three Generations of Po

r

tuguese-

Canadians. Montreal: McGill–Queen

’s University Press, 1998.

Pap, Leo. The Portuguese-Americans. New York: Twayne, 1981.

———. The Por

tuguese in the United States: A Bibliography. New York:

Center for M

igration Studies, 1976.

Williams, J. And Yet They Come: Portuguese Immigration from the Azores

to the U

nited S

tates. New York: Center for Migration Studies,

1982.

Prince Edward Island

Ile-St.-Jean (Isle St. John) was claimed for France by

S

AMUEL DE

C

HAMPLAIN

in 1603. It was sparsely populated

and was part of A

CADIA

, in N

EW

F

RANCE

. French immi-

grants began to settle the island in the 1720s, but numbers

remained small, and France ceded it to Britain following

the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’ W

AR

(1756–63). After Britain acquired

the territory, it anglicized the island’s name. The number of

settlers remained small, both because of its isolation and the

difficulty for colonists to acquire clear title to the land. In

1767, the British government issued land grants to military

officers and others, requiring that they bring in colonists in

order to redeem their lands. Few attempted to fulfill this

requirement, and absentee landlords often made outright

purchase difficult. This drove many of the 600 United

Empire Loyalists, who had emigrated from America by way

of Nova Scotia in 1783–84, to seek residence in other parts

of the empire. Until 1769, the Isle St. John was governed as

part of N

OVA

S

COTIA

. In 1799, the British government

changed the island’s name to Prince Edward Island.

The first large-scale immigration to Prince Edward

Island began in 1772 when 300 displaced Highland Scots

arrived on the island, establishing a trend that would con-

tinue for more than 50 years as the Scottish Highlands were

cleared for grazing. Among the philanthropists who pro-

moted emigration, the most successful was T

HOMAS

D

OUG

-

LAS

, fifth earl of Selkirk, who assisted 800 Highlanders to

emigrate in 1803 and hundreds more in succeeding years.

Prince Edward Island gained self-government in 1851.

In 1867, it refused to join the Dominion of Canada, fear-

ing that it would lose political control of the island. An eco-

nomic downturn in the early 1870s, however, convinced

most of the islanders that federation was a wise policy. In

1873, Prince Edward Island joined the Dominion of

Canada as the seventh province.

Further Reading

Brown, Wallace. The King’s Friends: The Composition and Motiv

es of the

American Loyalist Claimants. Providence, R.I.: Brown University

Press, 1965.

Bumsted, J. M. Land, Settlement, and Politics on Eighteenth C

entury

Prince Edward Island. Kingston, Canada: McGill–Queens Uni-

versity Press, 1987.

Careless, J. M. S., ed. Colonists and Canadiens, 1760–1867. Toronto:

M

acmillan of Canada, 1971.

Cowan, Helen I. British Emigration to British North A

merica:

The

First Hundred Years. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1961.

M

acNutt, W. S. The Atlantic Provinces: The Emergence of Colonial Soci-

ety, 1712–1857. Tor

onto: McClelland and Stewart, 1965.

M

oore, Christopher. The Loyalists: Revolution, Exile, Settlement.

Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1984.

S

elkir

k, Lord. Lord Selkirk’s Diary, 1803–1804: A Journal of His Trav-

els in British North A

merica and the Northeastern United States.

Ed. Patrick C. T. White. Toronto: Champlain Society, 1958.

W

ilson, B

ruce. Colonial Identities: Canada from 1760–1815. Ottawa:

National Ar

chives of Canada, 1988.

Proposition 187 (Save Our State Initiative)

Proposition 187 was a controversial California anti-immi-

gration initiativ

e approved by California voters on Novem-

ber 8, 1994. Because some of its provisions were almost

certainly unconstitutional, federal injunctions prohibited its

implementation; nonetheless, Proposition 187 symbolized a

growing

NATIVISM

in the United States at the end of the

20th century.

Concern over the cost of providing social services to ille-

gal immigrants, the increase of immigrant-related crime,

and fear of a continuing flow of illegal immigrants from

Mexico led Californians to approve (59 percent to 41 percent)

PROPOSITION 187 235

Proposition 187, which denied education, welfare benefits,

and nonemergency health care to illegal immigrants. In 1994,

it was estimated that more than 40 percent of all illegal immi-

grants in the United States were in California.

Anticipating legal challenges, proponents of Proposi-

tion 187 included language to safeguard all provisions not

specifically deemed invalid by the courts. Decisions by fed-

eral judges in both 1995 and 1998, however, upheld previ-

ous decisions regarding the unconstitutionality of the

proposition’s provisions, based on Fourteenth Amendment

protections against discriminating against one class of peo-

ple, in this case immigrants.

See also P

LYLER V

.D

OE

.

Further Reading

Martin, Philip. “Proposition 187 in California.” International Migra-

tion Review 29 (1995): 255–263.

Ono, K

ent, and John M. Sloop. Shifting Borders: Rhetoric, Immigra-

tion, and Califor

nia’s Proposition 187. Philadelphia: Temple Uni-

versity P

ress, 2002.

Puerto Rican immigration

Puerto Rico is a Caribbean island commonwealth of the

United States, located about 1,000 miles southeast of

Miami. Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens but do not pay fed-

eral taxes or vote in presidential elections while living in

Puerto Rico. They are not required to have visas or passports

to travel to the United States, and there are no quotas on

their entry. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 3,406,178 Americans claimed

Puerto Rican ancestry, while only 1,045 Canadians did so.

More than 1.3 million Puerto Ricans live in the New York

City area, and there are significant communities in Chicago,

Miami, and most of the major cities in the East. During the

1990s, Puerto Ricans increasingly chose smaller towns and

cities in Texas, California, and Florida.

Puerto Rico covers 3,515 square miles, facing the

Atlantic Ocean to the north and the Caribbean Sea to the

south. Puerto Rico was inhabited by Arawak Indians when

C

HRISTOPHER

C

OLUMBUS

first claimed the land for Spain

in 1493. Within a few decades, virtually all the native peo-

ples had died of disease, war, or forced labor. More than 95

percent of the population of 3,829,000 (2001) consider

themselves Puerto Ricans. They are mainly descended from

Europeans—most notably Spaniards, and some Corsicans,

Irish, and Germans—with some Indian influences from the

early period and a significant African component from the

long period of slavery between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Under the Spanish Crown, Puerto Rico remained relatively

poor and enjoyed virtually no political rights. As a result,

nationalistic rebellions broke out in the 1830s, 1860s, and

1890s. Through the Spanish-American War of 1898, the

United States gained control of Puerto Rico (along with the

Philippines and Guam) and in 1900 passed the Organic

(Foraker) Act, which established a civilian government

largely under the control of a governor appointed by the

U.S. president. The Jones Act of 1917 provided more auton-

omy and conferred U.S. citizenship on Puerto Ricans but

left most of the power in the hands of the governor. The

Crawford-Butler Act of 1947 enabled Puerto Ricans to elect

their own governor, and in 1952, a new constitution was

authorized, making Puerto Rico a commonwealth in associ-

ation with the United States. Apart from matters of foreign

policy and currency, Puerto Rico is largely autonomous. The

debate over Puerto Rico’s future course—full independence,

continued autonomy as a commonwealth, or full statehood

in the Union—raged throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Eco-

nomically, the commonwealth has benefited from its associ-

ation with the United States, though not as much as many

had hoped. Puerto Rico has the highest per-capita income

among Caribbean islands, but it would have the lowest

among the states of the United States. In a nonbinding 1998

referendum, 46.5 percent of Puerto Ricans voted for state-

hood, demonstrating how deeply divided the population

remains on the issue.

The first significant migration to U.S. territory involved

5,000 Puerto Rican contract laborers who were hired to

work on sugar plantations in Hawaii between 1899 and

1901. Others began to migrate to the continental United

States after World War I (1914–18). Between 1910 and

1930, the Puerto Rican population in the United States

grew from 1,500 to more than 52,000. Ten years later,

Puerto Ricans numbered 70,000, with 88 percent living in

New York City. Improved transportation technologies,

including low-cost commercial air travel, dramatically

increased the rate of Puerto Rican migration after World

War II (1939–45). Throughout the 1950s, an average of

45,000 came to the United States annually, with increasingly

diversified destinations. By 1970, the percentage of Puerto

Ricans living in New York City had declined to less than 60

percent. After a downturn in numbers in the 1970s, struc-

tural problems in the economy led to a renewed migration

after 1980. Since World War II, there has always been a high

rate of return migration. The numbers of Puerto Ricans in

the United States nevertheless has risen significantly in every

decade, from some 1.5 million in 1970 to 2 million by

1980, 2.7 million in 1990, and 3.4 million in 2000.

Further Reading

Ambert, Alba N., and María D. Álvarez, eds. Puerto Rican Children on

the Mainland: I

nterdisciplinary Perspectives. New York: Garland,

1992.

Díaz-Briquets, Sergio, and Sidney Weintraub, eds. Determinants of

E

migration from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.

Boulder, Colo.: Westvie

w P

ress, 1991.

Rivera-Batiz, Francisco, and Carlos E. Santiago. Island Paradox: Puerto

Rico in the 1990s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1998.

236 PUERTO RICAN IMMIGRATION

———. Puerto Ricans in the United States: A Changing Reality. Wash-

ington, D.C.: National Puerto Rican Coalition, 1994.

Rodríguez, Clara. Puerto Ricans: Born in the USA. Boston: Unwin

Hyman, 1989.

Sánche

z-K

orrol, Virginia. From Colonia to Community: The History of

Pu

erto Ricans in New York City, 1917–1948. Westport, Conn.:

Greenwood P

ress, 1983.

Torre, Carlos Antonio, Hugo Rodríguez Vecchini, and William Bur-

gos, eds. The Commuter Nation: Perspectives on Puerto Rican

Migr

ation. R

ío Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial de la Universidad

de P

uerto Rico, 1994.

Torres, Andrés. Between the Melting Pot and the Mosaic: African Amer-

icans and P

uer

to Ricans in the New York Political Economy.

Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995.

Puritans See P

ILGRIMS AND

P

URITANS

.

PURITANS 237

Quaker immigration

The Quakers, officially members of the Religious Society of

Friends, were a pietistic Christian sect founded by George

Fox in England in the 1640s. Quakers believed that Christ’s

presence in the hearts of individuals provided an inner light

that would guide them in their beliefs and actions. As a

result, they emphasized inward spiritual experience rather

than conformity to outward creeds. At a time when all Euro-

pean states expected conformity to a state church, and the

Church of England had the strong support of a parliament

fearful of dissent, the Quakers were considered radical and

were often persecuted. In practice, they were generally paci-

fists, egalitarians, and social reformers, emphasizing society’s

common humanitarian concerns. But they refused to swear

oaths in court or recognize distinctions in society and as

such were both annoying and potentially dangerous to the

state and the aristocratic society in which they lived. Quaker

missionaries first immigrated to the Massachusetts Bay

colony in 1656, where they were not well received. Puritan

magistrates drove them out of the colony and ordered the

execution of several Friends between 1659 and 1661.

The transformation of Quakers from mistrusted reli-

gious radicals to model pioneers was largely the work of

W

ILLIAM

P

ENN

, who was born into an aristocratic English

family. Penn was expelled from Oxford University in 1662

for unorthodox religious views and eventually joined the

Society of Friends. In 1668, he published Truth Exalted, the

first of his 150 books, pamphlets, and tracts, and trav

eled

extensively in B

ritain and Europe, preaching and promoting

the doctrines of the Quakers. Violating numerous laws pro-

hibiting non-Anglican (Church of England) preaching,

meeting, and publishing, he spent two years in prison. He

nevertheless was well connected politically, having friends

among the supporters of the Stuart kings as well as the

Whigs who opposed the Stuart monarchy. When the N

EW

J

ERSEY COLONY

foundered, in 1674, a group of Quaker

investors, including Penn, bought a stake in it and divided it

into East Jersey and West Jersey. West Jersey became the first

Quaker colony in America, but it eventually went bankrupt

and was rejoined to East Jersey in 1702 to form a royal

colony. Dismayed by Quaker quarreling in Jersey, in the

late 1670s, Penn turned his attention to the unsettled land

west of Jersey as a possible refuge for persecuted European

Quakers. In 1681, he was granted a royal charter guarantee-

ing both land and governance, thereby enabling him to

establish the P

ENNSYLVANIA COLONY

from the first accord-

ing to Quaker principles.

In 1682, Penn published his Frame of Government,

which established the principles of liberty of conscience,

freedom from persecution, and due process of law

. In the

same year, he purchased the Three Lower Counties (later,

D

ELAWARE COLONY

) from James, Duke of York, in order

to guarantee access to the sea. As a proprietor, he advertised

widely throughout England, Ireland, and the German states,

lauding the rich Pennsylvania soil and the high degree of

personal freedoms enjoyed there. Indeed, the colony became

a model of the religious toleration that Penn so deeply sup-

ported. Although Quakers held the most influential posi-

238

Q

4

tions of leadership and governed according to Quaker prin-

ciples—there was no army and only a small police force—

Pennsylvania was from the first both ethnically and

religiously diverse. In 1685 alone, 8,000 immigrants arrived,

most of them Quakers from the British Isles. They largely

settled in southeastern Pennsylvania, around the cosmopoli-

tan city of P

HILADELPHIA

. Between the 1680s and the

1720s, Mennonites, Amish, Moravians, Dunkers, Schwenk-

felders, and Lutherans arrived from across Europe and soon

outnumbered the Quakers. Only a few years into the

colony’s development, Penn could boast that the people of

Pennsylvania were “a collection of divers nations in Europe,”

including “French, Dutch, Germans, Swedes, Danes, Finns,

Scotch, Irish, and English.”

Diversity and toleration together produced an unruly

political process in Pennsylvania, with the Quaker-domi-

nated urban areas frequently at odds with the country, espe-

cially the Three Lower Counties, which were inhabited

principally by Dutch, Swedish, and Finnish settlers who had

little connection with Penn. In 1701, Penn’s Charter of Lib-

erties granted political control to a unicameral assembly, free

from proprietary influence. By 1725, most of the 25,000

Quakers who had immigrated to the Delaware Valley lived

in Pennsylvania. By 1760, Germans accounted for more

than one-third of the entire population of the colony, and

after 1760, German and Scots-Irish settlers rapidly filled

the trans-Appalachian Pennsylvania west, far from Quaker

influence and English control. By 1756, Quakers had lost

political control in the colony.

Further Reading

Barclay, Robert. B

arclay’s “Apology” in Modern English. Ed. Dean Frei-

day. Richmond, Ind.: Friends United, 1967.

Davies, Adrian. The Quakers in E

nglish Society

, 1655–1725. New York:

Clarendon Press of Oxford University Press, 2000.

Moore, Rosemary. The Light in Their Consciences: Early Quakers in

B

ritain, 1646–1666. U

niversity Park: Pennsylvania State Univer-

sity Press, 2000.

T

r

ueblood, Elton. The People Called Quakers. Richmond, Ind.: Friends

United, 1971.

Quebec

The Canadian province of Quebec is unique in North

America in maintaining a predominantly French heritage,

despite being surrounded by English-speaking areas that

would eventually become the Canadian provinces of

Ontario, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and the U.S.

states of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, and New York.

As a result, Quebec eventually gained a considerable mea-

sure of autonomy and an independent immigration policy.

S

AMUEL DE

C

HAMPLAIN

founded the first permanent

French settlement at Quebec in 1608, a fur-trading post that

linked France with the vast interior regions of North Amer-

ica that formed the core of the large colonial territory known

as N

EW

F

RANCE

. Along with the commercial impulse came

missionaries. In 1642, the Société de Notre-Dame de Mont-

réal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle France

founded Ville Marie, later known as M

ONTREAL

. Adminis-

trative mismanagement, failure to secure settlers, and the

constant threat from the region’s Native Americans brought

a complete reorganization of the government, which was

brought under royal control in 1663. During the entire

period of French control, only about 12,000 permanent

settlers immigrated to New France, with most concentrated

along the St. Lawrence Seaway, which came to be known as

Canada and is roughly coterminus with the modern

province of Quebec. According to a Swedish visitor in the

18th century, the heartland of Canada was “a village begin-

ning at Montreal and ending at Quebec,” for “the farm-

houses are never above five arpents [293 meters] and

sometimes but three apart, a few places excepted.”

Through an agreement with the French West Indies

Company, between 1663 and 1673, several thousand settlers

arrived, most from Brittany and Île-de-France, though some

QUEBEC 239

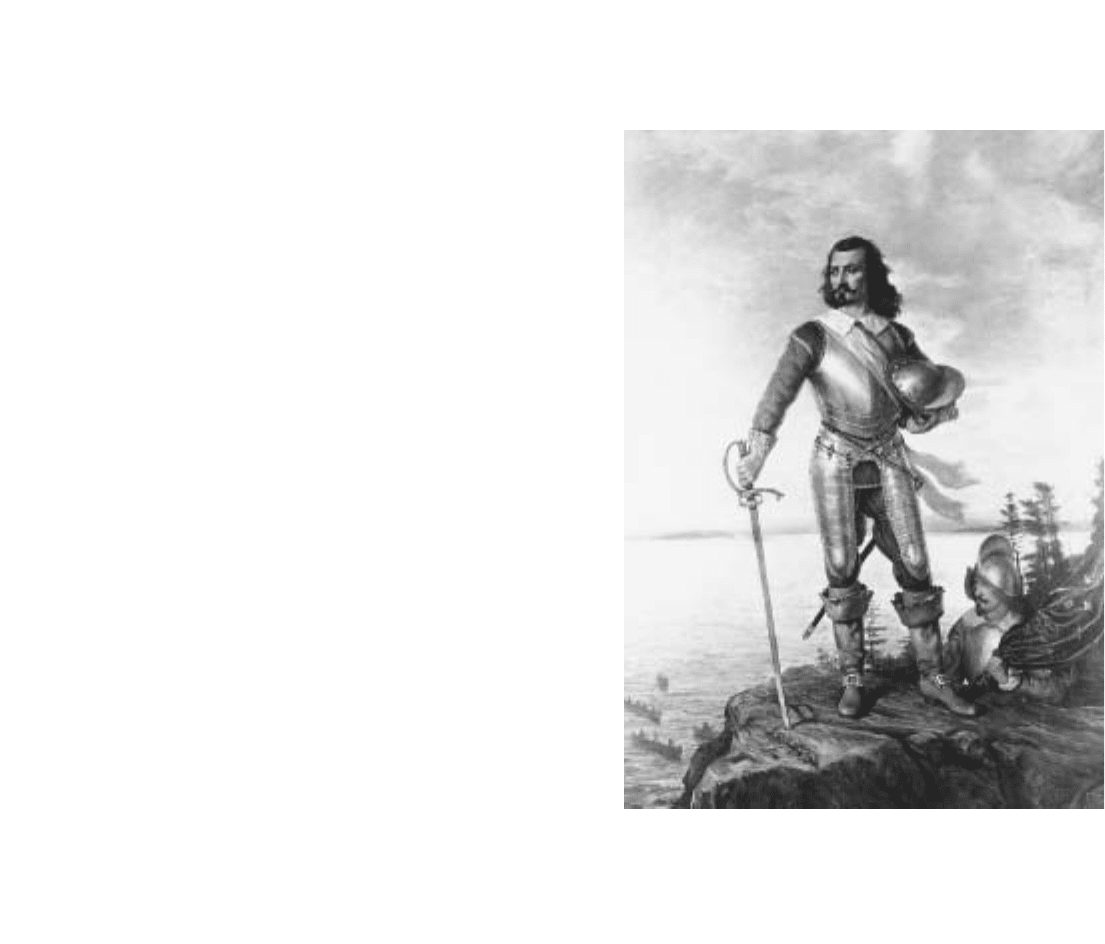

Samuel de Champlain founded the first permanent French

settlement in the New World at Quebec in 1608.

(Library of

Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-97748])

were recruited from Holland, Portugal, and various German

states. Among this wave of immigrants, however, there were

few families. Most were trappers, soldiers, churchmen, pris-

oners, and young indentured servants (see

INDENTURED

SERVITUDE

); by 1672, all plans for systematic immigration

were stopped. After 1706, merchants from a number of

European countries and their local agents were granted per-

mission to do business in Canada, leading to a thriving trade

in Quebec and Montreal. Indentured servants occasionally

came, and soldiers stationed in the colony as a result of the

ongoing conflict with Britain sometimes stayed on. The

number of slaves was always small, perhaps 4,000 Native

American and African slaves for the entire duration of New

France. More than a thousand convicts were forcibly trans-

ported. Remarkably, from this miscellaneous and meager

collection of 9,000 immigrants, the population of Canada

swelled to 70,000 by the 1750s. In a series of wars for con-

trol of North America (1689–1763), virtually all of New

France was lost to the British, the final blow coming in the

S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’ W

AR

(1756–63).

In 1763, France signed the Treaty of Paris, handing over

New France east of the Mississippi River to Great Britain.

Canada’s French population of some 70,000 was brought

under control of the British Crown, which organized the

most populous areas as the colony of Quebec. At first

administering the region under British law and denying

Catholics important rights, the British further alienated

their new citizens. In an attempt to win support of Que-

bec’s French-speaking population, Governor Guy Carleton

in 1774 persuaded the British parliament to pass the Q

UE

-

BEC

A

CT

(1774), which guaranteed religious freedom to

Catholics, reinstated French civil law, and extended the

southern border of the province to the Ohio River, incor-

porating lands claimed by Virginia and Massachusetts. This

marked the high point of escalating tensions that led to the

American Revolution (1775–83) and eventual loss of the

thirteen colonies and trans-Appalachian regions south of the

Great Lakes.

Loss of the thirteen colonies led to the migration of

40,000–50,000 United Empire Loyalists, who had refused

to take up arms against the British Crown and who were

thus resettled at government expense, most with grants of

land in N

OVA

S

COTIA

,N

EW

B

RUNSWICK

, and western

Quebec. The special provisions of the Quebec Act, which

aimed at preserving French culture and encouraging loyalty,

angered the new English-speaking American colonists. As a

result, the British government divided the region into two

colonies by the Constitutional Act of 1791. Lower Canada,

roughly the modern province of Quebec, included most of

the French-speaking population. There, government was

based on French civil law, Catholicism, and the seigneurial

system of land settlement. Upper Canada, roughly the mod-

ern province of Ontario, included most of the English-

speaking population and used English law and property

systems. Both colonies had weak elected assemblies. After

the French Revolution, Revolutionary Wars, and

Napoleonic Wars (1789–1815), hard times led English,

Irish, and Scottish people to immigrate to British North

America in record numbers. Fearing loss of control of the

government of Lower Canada, some French Canadians

revolted in 1837, which triggered a rebellion in Upper

Canada. Both rebellions were quickly quashed, and the

British government unified the two Canadas into the single

Province of Canada (1841). This form of government did

not work well, however, as the main political parties had

almost equal representation in the legislature and thus had

trouble forming stable ministries.

From 1848, the rapidly growing provinces in British

North America won self-government and virtual control

over local affairs. By the 1860s, there was general agreement

on the need for a stronger central government, which led to

the confederation movement. Passage of the British North

America Act in 1867 created the Dominion of Canada and

reestablished French-speaking Quebec as a separate

province. Although citizens of Quebec were permitted to use

both French and English as their official language and

granted control of education and civil law, friction over a

wide variety of issues heightened the province’s sense of iso-

lation. Quebec disapproved of government policies during

the Boer War (1899–1902), World War I (1914–18), and

World War II (1939–45). It was the most isolationist part of

Canada, vigorously opposing all immigration but especially

the immigration of Jews. By 1968, an independent Ministry

of Immigration of Quebec was established, enabling Québe-

cois to maintain control of the ethnic population of the

province, ensuring the priority of francophone culture.

Leaders also opposed vigorous industrialization, as enriching

English entrepreneurs while destroying traditional French-

Canadian culture. Finally, in the 1960s widespread dis-

agreement over apportionment of taxes led to a separatist

movement that continued into the 21st century under the

banner of the Parti Québecois (formed in 1968). In a dra-

matic referendum in October 1995, with more than 94 per-

cent of the electorate casting ballots, 50.6 percent voted

against Quebec sovereignty. Parti Québecois leaders openly

blamed “ethnics” for siding with the anglophones in order to

thwart independence. Most observers believe that Quebec’s

independence will come in the relatively near future.

Montreal is the economic heart of the province of Que-

bec and thus attracts a large number of migrants from other

parts of Canada, as well as immigrants from outside the

country. The city of Quebec, on the other hand is more

homogenous and more closely reflects the traditional con-

cerns of the French founders. The largest non-European eth-

nic groups in Montreal in 2001 were Haitian (69,945, 2.1

percent of the population), Chinese (57,655, 1.7 percent of

the population), and Greek (55,865, 1.6 percent of the pop-

ulation). No non-European ethnic group in the city of Que-

240 QUEBEC

bec numbered more than 1,400, or 0.2 percent of the pop-

ulation (Chinese).

See also C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY

REVIEW

.

Further Reading

Anctil, Pierre, and Gary Caldwell, eds. Juifs et réalités juives au Q

uebec.

Quebec: Institut québecois de recherche sur la culture, 1984.

Behiels, M

ichael D. Quebec and the Question of Immigration: From

Ethnocentrism to Ethnic P

luralism, 1900–1985. Ottawa: Cana-

dian Historical Association, 1991.

Cairns, Alan C. Char

ter versus Federalism: The Dilemmas of Constitu-

tional R

efor

m. Montreal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s Univer-

sity Pr

ess, 1992.

Eccles, William J. Canada under Louis XIV, 1663–1701. Toronto:

M

cClelland and S

tewart, 1964.

———. Fr

ance in America. N

ew York: Harper and Row, 1972.

Martel, Marcel. French Canada: An Account of Its Creation and Break-

U

p, 1850–1967. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association,

1998.

M

inistèr

e d’Immigration, Rapport Annuel, 1980–81. Quebec: Min-

istère d

’Immigration, 1981.

Moogk, Peter N. La Nouvelle France:

The M

aking of French Canada—

A Cultural History. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press,

2000.

Pâquet, Martin. Toward a Q

uebec Ministry of Immigration,

1945–1968. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1997.

Trigger, Bruce G. Natives and Newcomers: Canada’s “H

er

oic Age” Recon-

sidered. Kingston, Canada: McGill–Queen

’s University Press,

1987.

Vachon, André. Dreams of Empire: Canada before 1700. Ottawa: Pub-

lic Archives of Canada, 1982.

Quebec Act (1774)

The Quebec Act of 1774 was passed by Great Britain on

the heels of a constitutional crisis in Massachusetts and the

failure of attempts to attract English-speaking immigrants to

Q

UEBEC

, the French culture region they had acquired at

the end of the S

EVEN

Y

EARS

’W

AR

(1756–63).

Following the war, Britain had ruled Canada by military

authority. In the Proclamation of 1763, Britain prohibited

settlement beyond the Appalachian Mountains, hoping to

attract English-speaking settlers northward, both to dilute

French influence and to halt the expansion of self-govern-

ing colonies. Having little success, Governor Guy Carleton

determined that Canada would always have a French-speak-

ing majority and that Britain should thus do all it could to

gain the loyalty of the inhabitants in the event of rebellion in

the thirteen colonies to the south. The Quebec Act acknowl-

edged that “experience” had dictated that 65,000 French

Catholics could not be governed according to English prin-

ciples and that it was “inexpedient” at the moment to form

an elective assembly. The king would thus appoint a provin-

cial council that would oversee the continued application of

French civil law in the colony and guarantee the right to

practice Roman Catholicism. These provisions angered

English settlers there, who in 1763 had been promised a rep-

resentative assembly and a British system of law. More

provocatively, the act enlarged Quebec to include much of

what is now Quebec and Ontario, the area bounded by the

Great Lakes, the Ohio River, the Appalachian Mountains,

and the Mississippi River. Although not overtly directed at

Massachusetts, the Quebec Act was the final in a series of

coercive measures—the “Intolerable Acts” as they were

dubbed in Massachusetts—that imposed greater Crown

control over colonial politics and justice. These coercive

measures led to the calling of the First Continental

Congress in September 1774. Most French Canadians

remained neutral during the A

MERICAN

R

EVOLUTION

,

(1775–83), which secured for the newly independent

colonies the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys.

Further Reading

Bailyn, Bernard, and Philip D. Morgan, eds. Strangers within the

Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British E

mpire. Chapel Hill:

Univ

ersity of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Lawson, Philip. The Imperial Challenge: Quebec and Britain in the Age

of the A

merican R

evolution. Montreal and Kingston:

McG

ill–Queen’s University Press, 1990.

Neatby, Hilda. Quebec, 1760–1791. Toronto: McClelland and Stew-

ar

t, 1966.

———, ed. The Q

uebec Act: Pr

otest and P

olicy. Scarborough, Canada:

Prentice-Hall, 1972.

Stanley, George. Canada Invaded, 1775–1776. Toronto: Hakkert,

1973.

QUEBEC ACT 241

racial and ethnic categories

Immigration in the 19th and 20th centuries transformed

Canada and the United States from countries predomi-

nantly populated by west Europeans (notably English,

French, Scots-Irish, and German) to countries composed of

most of the world’s racial and ethnic groups. Between 1950

and 1998, for instance, the minority population of the

United States more than tripled, and it was estimated that

by the middle of the 21st century, non-Hispanic whites

would constitute only about 50 percent of the population.

In an attempt to understand and plan for the results of pop-

ulation changes, questions regarding race and ethnicity have

been part of the immigration process and census taking in

North America over the years, though in a variety of forms

according to the needs of the day (see

CENSUS AND IMMI

-

GRATION

). These questions were introduced in Canada in

1765 and in the United States in 1790. Racial and ethnic

identification became an essential part of governmental

planning from the 1840s onward in the wake of the Irish

famine, or Great Potato Famine (1845–51), and the wave

of immigration that swept the United States and Canada

between 1865 and 1914. There has never been a universally

accepted definition of race, however. At various times in his-

tory it has stood for contemporary concepts of tribe, nation,

or ethnic group. Since the 18th century race was increasingly

used to distinguish a gr

oup based on skin color and other

physical characteristics.

The classification most commonly

accepted throughout the West recognized three major races:

Caucasians (white), Mongolians (yellow), and Africans

(black). Other taxonomists incorporated personality and

moral traits in identifying race. As the 19th century pro-

gressed, romantic thought and Darwinism combined with

racial classification to create an intellectual atmosphere in

which

RACISM

flourished.

United States

Although the United States did not explicitly incorporate

racial concepts into immigration policy until the C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

(1882), the practice of slavery in the South

until 1865 implicitly recognized racial distinctions. Also,

from colonial times, there were perceptions of desirable and

undesirable immigrants. In the 1924 J

OHNSON

-R

EED

A

CT

,

the foundation of U.S. immigration policy until 1965, the

government established permanent quotas based on 2 per-

cent of the foreign-born population in 1890, reflecting the

“racial” composition of the country prior to massive immi-

gration from southern and eastern Europe. During the latter

half of the 20th century, an understanding of genetics and

the dramatic increase of mobility and hybridization led most

scholars to accept the inadequacy of traditional racial classi-

fications in explaining human biodiversity. By the start of

the 21st century, ethnicity, rather than race, was seen as a

more valuable tool for analysis and explanation, as it incor-

porated language, religion, geography, and custom in estab-

lishing group identities.

In addressing the needs of its citizens, however, the U.S.

government could not altogether dispense with historical

racial classifications. The close association of slavery and race

242

R

4

and the lingering effects of racism encouraged in African

Americans a strong sense of racial identity according to the

older conception. On the other hand, the fastest-growing

minority category of Hispanics was culturally, rather than

racially, based (see H

ISPANIC AND RELATED TERMS

). Quan-

tification was especially important in 2000, as the census

directly affected legislative redistricting and fair political rep-

resentation. The 2000 census therefore asked two overlap-

ping questions regarding race and Hispanic origin.

Respondents were given a wide range of terms with which to

identify themselves, including both traditional racial con-

cepts (for example, “white”; “Black, African Am., or Negro”;

“American Indian or Alaska Native”) and specific ethnic

groups (for example, “Asian Indian” or “Native Hawaiian”).

In addition, respondents could identify themselves as “some

other race,” writing in their own self-designation. In 2000,

the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) established

the following definitions regarding racial and ethnic catego-

rization for use in the census:

“White” refers to people having origins in any of the orig-

inal peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.

It includes people who indicated their race or races as

“White” or wrote in entries such as Irish, German, Ital-

ian, Lebanese, Near Easterner, Arab, or Polish.

“Black or African American” refers to people having

origins in any of the black racial groups of Africa. It

includes people who indicated their race or races as

“Black, African Am., or Negro” or wrote in entries such

as African American, Afro American, Nigerian, or

Haitian.

“American Indian or Alaska Native” refers to people

having origins in any of the original peoples of North,

Central, and South America and who maintain tribal

affiliation or community attachment. It includes people

who indicated their race or races by marking this cate-

gory or writing in their principal or enrolled tribe, such

as Rosebud Sioux, Chippewa, or Navajo.

“Asian” refers to people having origins in any of the

original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the

Indian subcontinent. It includes people who indicated

their race or races as “Asian Indian,” “Chinese,” “Fil-

ipino,” “Korean,” “Japanese,” “Vietnamese,” or “Other

Asian,” or wrote in entries such as Burmese, Hmong,

Pakistani, or Thai.

“Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander”

refers to people having origins in any of the original peo-

ples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.

It includes people who indicated their race or races as

“Native Hawaiian,” “Guamanian or Chamorro,”

“Samoan,” or “Other Pacific Islander” or wrote in

entries such as Tahitian, Mariana Islander, or Chuukese.

“Some other race” was included in U.S. Census

2000 for respondents who were unable to identify with

the five OMB race categories. Respondents who provided

write-in entries such as Moroccan, South African,

Belizean, or a Hispanic origin (for example, Mexican,

Puerto Rican, or Cuban) are included in the Some

Other Race category.

For statistical purposes, the government understood

that “Spanish/Hispanic/Latino” could refer to people of

any race. The OMB defined “Hispanic or Latino” as “a

person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central

American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of

race.”

Canada

Canada’s unique history led to a distinct set of racial and eth-

nic classifications for purposes of enumeration and policy

development, including those of European descent, those

of “Aboriginal” (that is, indigenous) ancestry, an increasing

number of immigrants who fit neither category, and those of

multiple ethnic origins. Questions regarding race and eth-

nicity were modified on the 1996 census.

Before 1996, the 15 most frequent origins were listed

after the question, “To what ethnic or cultural group(s) did

this person’s [the respondent’s] ancestors belong?” along

with two blank spaces for others answers to be included. In

1996, no prelisted categories were included after the ques-

tion, although 24 examples of possible origins were listed,

including, for the first time, “Canadian.” In 1996, 5.3 mil-

lion persons (19 percent) considered “Canadian” as their

only ethnic origin, while another 3.5 million persons (12

percent) reported their origins to be “Canadian” and some

other ethnic group. As a result of this change, which allows

almost unlimited self-identification, it is difficult to com-

pare ancestry figures before and after 1996. With no

prelisted census categories, Statistics Canada categorized

responses for compilation purposes.

Most ethnic questions were self-explanatory, though

some require clear definition. Respondents who reported

“French-only ancestry” include both those who listed

France as the country of origin and those who listed Aca-

dia as the basis of their ethnic origin. Both “North Ameri-

can Indian ancestry” and “Métis ancestry” (European and

Indian) were considered in the compilation of “Aboriginal”

figures. Finally, using the Employment Equity Act defini-

tion, the census defined a “visible minority” as “Persons,

other than Aboriginal peoples, who are not-Caucasian in

race or non-white in color,” and incorporates in this cate-

gory self-identified responses including Chinese, South

Asians, Blacks, Arabs and West Asians, Filipinos, Southeast

Asians, Latin Americans, Japanese, Koreans, and Pacific

Islanders.

See also C

ANADA

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND POLICY

REVIEW

;U

NITED

S

TATES

—

IMMIGRATION SURVEY AND

POLICY REVIEW

.

RACIAL AND ETHNIC CATEGORIES 243