Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Wittke, Karl. Refugees of Revolution: The German Forty-eighters in

America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1952.

Zucker

, Alfred E., ed. The Forty-Eighters: Political Refugees of the Ger-

man Rev

olutions of 1848. New York: Columbia University Press,

1959.

Rhode Island colony

From the establishment of Providence Plantation by Roger

Williams in 1636, Rhode Island was known as the refuge of

dissident troublemakers. Principally made up of indepen-

dent, agricultural communities, it remained small and

almost totally populated by English settlers.

Europeans first explored coastal Rhode Island in the

early 16th century. It was not permanently settled, how-

ever, until Williams sought personal and religious free-

dom after being driven from the M

ASSACHUSETTS

COLONY

in 1636. Having come to New England as a Puri-

tan (see P

ILGRIMS AND

P

URITANS

), he declared himself a

Separatist, encouraging his congregation to break ties with

the Church of England and denouncing the charter of the

Massachusetts Bay colony. Other dissidents driven from

Massachusetts, including William Coddington, John

Clarke, and Anne Hutchinson, established Portsmouth

and Newport in 1638. Fearing the evil effects of the

absence of English law in Providence, a number of promi-

nent citizens left to found Warwick in 1643. Four years

later, Providence, Portsmouth, Newport, and Warwick

joined together in order to repel encroachments from bor-

dering colonies. A new charter of 1663 provided the legal

basis for self-government that lasted into the 19th cen-

tury. In 1686, Rhode Island was forced, along with Mas-

sachusetts Bay, Plymouth, C

ONNECTICUT COLONY

, and

N

EW

H

AMPSHIRE COLONY

, into the Dominion of New

England, a heavy-handed autocratic experiment that failed

as a result of the deposition of King James II of Britain

during the Glorious Revolution of 1688–89.

The religious freedom that prevailed in early Rhode

Island made it a refuge for several persecuted groups

including Baptists, Quakers, Antinomians, Jews, and

French Huguenots (Calvinists), groups that drew from

diverse ethnic and national backgrounds. Although small,

the colony prospered. Its diverse economy incorporated

rich farmlands, whaling and fishing industries, and exten-

sive transatlantic commerce. By the time of the A

MERICAN

R

EVOLUTION

(1775–83), the colony regularly traded with

England, the Portuguese islands, Africa, South America,

the West Indies, and other British mainland colonies. The

most lucrative commerce was in slaves, forming one leg of

a triangular route that brought molasses from the West

Indies to Rhode Island, whose distilleries made rum, which

was then sent to Africa for the purchase of slaves. Rhode

Island was, however, the first colony to prohibit the slave

trade, in 1774.

Further Reading

Archer, Richard. Fissures in the Rock: New England in the Seventeenth

C

entury. Hanover: University of New Hampshire, University

Pr

ess of New England, 2001.

James, Sydney V. Colonial Rhode I

sland: A H

istory. New York: Scribner,

1975.

McLoughlin, William G. Rhode Island: A History. New York: W. W.

Nor

ton, 1986.

W

eeden, William B. Early Rhode Island: A Social History of the People.

New York: Grafton Press, 1910.

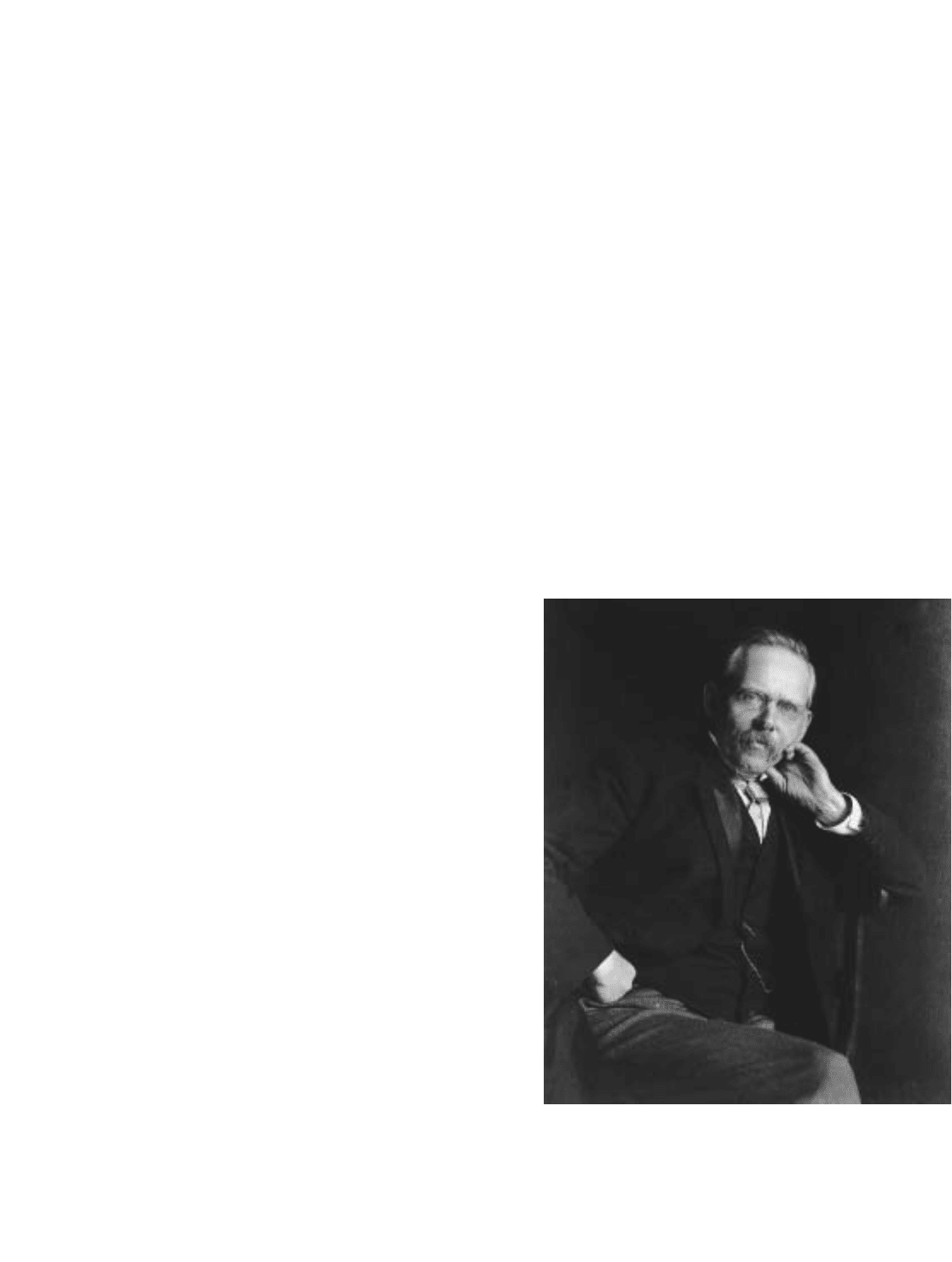

Riis, Jacob (1849–1914) journalist, author

An immigrant himself, Jacob Riis became one of the first

progressive photojournalists in the United States, drawing

the public’s attention to the plight of poor immigrants living

in U.S. cities. Although he has sometimes been criticized for

perpetuating ethnic stereotypes and favoring immigrants

from northern and western Europe, his photographs and

writings did much to encourage America’s middle class to

adopt more favorable attitudes toward immigration and

254 RHODE ISLAND COLONY

This photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston shows Jacob Riis, a

Danish immigrant journalist and photographer, ca. 1900. Riis

established his reputation as a reformer with the innovative

How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New

Y

ork (1890),

which stressed the importance of the immigrant

envir

onment.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

[LC-USZ62-47078])

urban reform. How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the

Tenements of New York (1890) remains the classic represen-

tation of the trials and the humanity of the urban poor dur-

ing the great wav

e of immigration that swept the country

between 1880 and 1914.

Riis was born in Ribe, Denmark, the third of 14 chil-

dren. The family was poor, but his father was a respected

teacher. Following Elisabeth Nielsen’s rejection of his pro-

posal of marriage at the insistence of her parents, Riis

immigrated to the United States in 1870. After several

years of itinerant labor, he established himself as a reporter

and eventually bought the South Brooklyn News. This pro-

vided him with the r

esour

ces to ask Nielsen to reconsider

his proposal, which she did. Riis established his reputa-

tion as a police reporter for the New York Tribune

(1877–90) and New York Evening Sun (1890–99). Work-

ing in the worst slums of N

e

w York City, he found his life-

work depicting the horrors of the slums and especially the

degrading conditions in which children were raised. In

How the Other Half Lives (1890), he used innovative pho-

tographic techniques and a progressive prose to suggest

that, ho

w

ever degraded immigrants might appear, they

were not inherently bad. During the 1890s his friendship

with Theodore Roosevelt (successively New York police

commissioner, governor of New York, and president of

the United States) led to a variety of progressive reforms

aimed at slum clearance, the building of parks and play-

grounds, and better treatment for the indigent.

Riis’s numerous works, including The Children of the

Poor (1892), Out of Mulberr

y S

treet: Stories of Tenement Life

in New York City (1898), A Ten Years’ War: An Account of the

Battle with the S

lum in New York (1900), and Children of

the Tenements (1903) identified for his middle-class r

eaders a

host of other progressiv

e causes, which were led by others.

Although Riis became a U.S. citizen in 1895, he often vis-

ited his hometown and continued to extol the virtues of his

native Denmark.

Further Reading

Alland, Alexander, Sr. Jacob A. Riis: Photographer and Citizen. Miller-

ston, N.Y.: A

perture, 1974.

Lane, James B. Jacob A. Riis and the American City. Port Washington,

N.Y

.: K

ennikat Press, 1974.

Riis, Jacob. How the Other Half Lives. Ed. David Leviatin. Boston:

B

edfor

d Books, 1997.

Riis, Jacob. The Making of an American. Ed. Roy Lubove. New York:

H

arper and R

ow, 1966.

Roanoke colony

The Roanoke colony, established as a business venture by

S

IR

W

ALTER

R

ALEIGH

, was the first English settlement in

the New World. Although three successive attempts at set-

tlement failed (1585, 1586, 1587), the colony heralded

England’s entry into the competition for lands in the Amer-

icas, further heightening long-standing tensions with Spain.

Raleigh, as most explorers of his time, was looking for

gold or silver, but he was also conscious of England’s inter-

national position relative to Spain. He carefully planned the

first English colony in territory claimed by Spain but far

north of any actual settlement. An island located between

the North Carolina mainland and the Outer Banks,

Roanoke was difficult to reach, requiring navigation of the

treacherous Cape Hatteras. Raleigh first sent Ralph Lane, a

fellow veteran of the Irish wars, to build a fort on Roanoke.

Most of the ships failed to reach the island, and food was

scarce when they arrived. Relations with the native peoples

were bad from the beginning. When Sir Francis Drake vis-

ited the colony in 1586, the remaining settlers determined

to return to England with him. A second attempt in 1586

foundered in the West Indies. The third attempt in 1587

was led by John White, an experienced seaman who had

sailed with Martin Frobisher in the 1570s and a survivor of

the first venture. His intent was to settle on Chesapeake Bay,

but a disagreement with a ship’s captain left the colonists

again on Roanoke Island. White was sent back to England

for supplies, but diplomatic tensions and war with Spain

kept him from returning until 1590. By then the colony had

been deserted. The mysterious carving of the word Croatoan

on a post suggested that the survivors had joined the nearby

I

ndian settlement called C

roatoan, but no other trace of the

colonists was ever found. White’s paintings of the landscape,

animals, and peoples of the region left an indelible visual

impression of a potential land of plenty.

Further Reading

Kupperman, Karen O

rdahl. Roanoke: The Abandoned Colony. Reprint.

New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 1991.

Miller, Lee. Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony. New York:

P

enguin, 2002.

Q

uinn, David Beers. England and the Discovery of America,

1481–1620. New Y

ork: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974.

———. Set Fair for Roanoke. University of North Carolina Press,

1985.

———, ed. The Roanoke V

oyages, 1584–1590: Documents to Illustrate

the English Voyagees to North America under the Patent Granted to

Walter Raleigh in 1584. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications,

1991.

Rølvaag, Ole Edvart (1876–1931) author, educator

Ole Rølvaag became one of the premier chroniclers of the

Norwegian immigrant experience in the United States. His

masterpiece Giants in the Earth (1927) is often considered

one of the best, most po

w

erfully written novels about pio-

neer life in America.

Rølvaag was born into a fishing family on the island of

Dønna, Norway. He immigrated to the United States in

RØLVAAG, OLE EDVART 255

1896, working on his uncle’s farm in Elk Point, South

Dakota, to help pay for his education. After years of toil, he

earned a bachelor’s degree from St. Olaf College in Min-

nesota in 1905, and after a year of study at the University of

Oslo, he returned to join the faculty of St. Olaf College.

There he taught Norwegian language and literature until his

death. He became a U.S. citizen in 1908 and married Jenny

Berdahl the same year. The harshness of Rølvaag’s own expe-

rience, from the years of hard work to the loss of two chil-

dren, contributed to the tone of his novels, which

emphasized the psychological uncertainty and loss experi-

enced by Norwegian immigrants. Hoping to encourage sec-

ond- and third-generation Norwegians to maintain their

native culture, Rølvaag finally realized that it was an impos-

sible dream. “Again and again,” he wrote, second-generation

Norwegians “have had impressed on them: all that has

grown on American earth is good, but all that can be called

foreign is at best suspect.” Other important works include

Letters from America (1912), On Forgotten Paths (1914), and

Pure Gold (1930). The English translation The Book of Long-

ing (1933) and Rølvaag’s last book, Their Father’s God

(1931), were published posthumously.

Further Reading

Jorgenson, Theodore, and Nora O. Slocum. Ole Edvart Rølvaag. New

Yor

k: Harper, 1939.

Moseley, Ann. Ole Edvart Rølvaag. Boise, Idaho: Boise State Univer-

sity

, 1987.

Reigstad, Paul. Rølvaag: H

is Life and Art. Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Press, 1972.

Roma immigration See G

YPSY IMMIGRATION

.

Romanian immigration

Most ethnic Romanians from the Ottoman, Austrian, and

Russian Empires and the state of Romania came as laborers

and peasants and sought work wherever they could find it in

North America. In the United States, they were attracted

mainly to the industrial cities of the North, most promi-

nently Cleveland, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; and Chicago,

Illinois. In Canada, peasants found opportunities to home-

stead on the prairies of what are now Saskatchewan and

Alberta. According to the U.S. census of 2000 and the

Canadian census of 2001, 367,310 Americans and 131,830

Canadians claimed Romanian ancestry. By 2000, Romani-

ans were widely spread throughout North America. In the

1990s, New York, Los Angeles, and Ontario were replacing

the older areas as most favored areas of settlement.

Romania occupies 88,800 square miles in southeast

Europe on the Black Sea. It is bordered on the north and east

by Ukraine, on the east by Moldova, on the west by Hungary

and Serbia and Montenegro, and on the south by Bulgaria.

In 2002, the population was estimated at 22,364,022, with

89.1 percent of the population being Romanian, and 8.9 per-

cent, Hungarian. More than two-thirds are adherents of the

Romanian Orthodox Church; Roman Catholics and Protes-

tants each make up about 6 percent of the population. Roma-

nian tribes first created a Dacian kingdom that was occupied

by the Roman Empire between 106 and 271. During that

time, the people and their language were Romanized, setting

them apart from the Slavs and Magyars who lived in sur-

rounding areas. The foundation of the modern state struc-

ture was laid in the 13th century, particularly in the regions of

Moldavia and Walachia, two principalities that were incorpo-

rated into the Ottoman Empire early in the 16th century. The

western region of Transylvania, occupied by Romanians,

Magyars, and Germans, formed a borderland between the

lands of the Muslim Ottoman conquest and the Austrian and

Hungarian lands of Christian Europe. Moldavia and Walachia

were united to form Romania in 1863, and became fully inde-

pendent in 1878. As an ally of Nazi Germany in World War

II (1939–45), Romania lost considerable territory, including

northern Bukovina, Bessarabia, and Trans-Dniestria. Falling

under Soviet

COLD WAR

domination, Romania’s economy

deteriorated until it became one of the poorest countries in

Europe. The country of Moldova, independent since the

breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, was essentially the old

Romanian province of Bessarabia, and its people, mostly

Romanians.

The first Romanians to immigrate to North America

were Jews who came between 1870 and 1895 from Mol-

davia; Bessarabia, then under Russian control; or Bukovina,

under Austrian control. Their numbers were small, but they

did establish the basis for a permanent settlement in what

would become Saskatchewan, in Canada. Between 1905

and 1908, they were joined by more than 200 additional

homesteaders, brought to the area by Maurice, baron de

Hirsch’s Jewish Colonization Society. The first significant

immigration in both the United States and Canada came

between 1895 and 1920. During that period, it is estimated

that more than 80,000 Romanians immigrated to the

United States. Exact figures are difficult to determine, as

most statistics were based on country of origin, which most

often would have been Austria, Russia, or Hungary. Even

after World War I (1914–18), with the creation of an

expanded Romania, pre–World War I borders were fre-

quently used to determine classification. Nevertheless, most

Romanians came as single men intending to earn money

and then return home, and the rate of return migration was

high. Most were unskilled and found work in iron, steel,

auto, and meatpacking industries of the U.S. North and

Midwest. The Canadian experience in this period was very

different, with most coming from peasant backgrounds in

Transylvania and settling in Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Exact numbers are difficult to determine, as the majority of

Romanians actually emigrated from lands controlled by the

256 ROMA IMMIGRATION

Austro-Hungarian or Ottoman Empires. As settled farmers,

Canadian Romanians tended to stay in North America. By

1921, there were about 30,000 Romanians in Canada.

In the aftermath of World War II (see W

ORLD

W

AR

II

AND IMMIGRATION

), thousands of “Forty-eighters” arrived

as refugees. About 10,000 were admitted to the United States

under provisions of the D

ISPLACED

P

ERSONS

A

CT

(1948).

Most were relatively well educated and staunchly anticom-

munist, with a large percentage of professionals among them.

Most settled in the industrial heartland, especially in New

York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cleveland,

and the mid-sized industrial towns of Ohio and western

Pennsylvania. During the long years of communist rule, emi-

gration was difficult, but with the fall of the communist

regime in 1989, Romanians again began to immigrate to

North America, mainly seeking economic opportunities.

Between 1990 and 2002, average annual Romanian immi-

gration to the United States was about 5,000. The movement

was proportionately much greater to Canada. Of the 60,165

Romanian immigrants in Canada in 2001, more than 58

percent of them (35,170), came between 1991 and 2001.

Many of them came from Yugoslavia’s Vojvodina region, flee-

ing persecution and civil war.

See also A

USTRO

-H

UNGARIAN IMMIGRATION

; R

US

-

SIAN IMMIGRATION

;Y

UGOSLAV IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Barton, J. Peasants and Strangers: Italians, Rumanians, and Slovaks in

an American City

, 1890–1950. Cambridge, Mass.: Har

vard Uni-

versity Press, 1976.

Galitzi, Christine A. A Study of Assimilation among the Roumanians in

the U

nited S

tates. 1929. Reprint, New York: AMS Press, 1968.

Patterson, G. J. “Greek and Romanian Immigrants as Hyphenated

Americans: Towar

ds a

Theory of White Ethnicity.” In New Direc-

tions in Gr

eek-American Studies. Eds. D. Georgakas and C. C.

Moskos. N

ew York: Pella, 1991.

———. “The Persistence of White Ethnicity in Canada: The Case of

the Romanians.” East European Q

uarterly 19 (1986): 493–500.

———. The Romanians of Saskatchewan: Four Generations of Adapta-

tion. Ottawa: National Museum of Man, 1977.

Tranu, Jean. Présence roumaine au C

anada. Montreal: J. Tranu, 1986.

Romany immigration See G

YPSY IMMIGRATION

.

Royal African Company

In 1672, the Royal African Company was granted a

monopoly in the British slave trade in order to ensure an

adequate labor force for the plantations of the Caribbean

and the southern colonies of the Atlantic seaboard of North

America. The company flourished between 1672 and 1698,

when Parliament opened the slave trade to all merchants.

Africans were brought to America in small numbers

beginning in 1619, when a Dutch warship landed about 20

workers at Port Comfort, Virginia (see A

FRICAN FORCED

MIGRATION

).

SLAVERY

as a legal institution was not pro-

vided for in the colonies, however, until 1661, and most

Africans in English colonies until the 1650s were probably

servants. With the passage of the first N

AVIGATION

A

CTS

in 1650–51 and the advent of a royal policy under Charles

II (r. 1660–85) discouraging the emigration of indentured

servants (see

INDENTURED SERVITUDE

), a labor shortage

ensued on southern plantations. In order to provide a more

stable labor force for tobacco, rice, and indigo farmers, in

1660, the British government chartered the Company of

Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa. During the second

Anglo-Dutch War (1665–67), the company failed but was

reorganized in 1672 as the Royal African Company. By the

1680s, it was averaging more than 25 annual voyages to

Africa and transporting 5,000 slaves a year. Still, the com-

pany was unable either to turn a profit or supply the

demand for slave labor. By 1713 the company was virtually

bankrupt, although it maintained some forts on the West

African coast until it was formally dissolved in 1821.

Further Reading

Collins, Edward Day. “Studies in the Colonial P

olicy of England,

1672–1680: The Plantations, the Royal African Company, and

the Slave Trade.” In American Historical Association Annual

Report .

.

. for the Year 1900. Washington, D.C.: American His-

torical Association, 1901.

Davies, K. G. The Royal African Company. London and New York:

Routledge/Thoemmes Pr

ess, 1999.

Galenson, David W. Traders, Planters, and Slaves: Market Behavior in

Early English America. New York: Cambridge Un

iversity Press,

1986.

Killinger, Charles Lintner. “The Royal African Company Slave Trade

to Virginia, 1689–1713.” M.A. thesis, College of William and

Mary, 1969.

Law, Robin, David Ryden, and J. R. Oldfield. The British Transatlantic

S

lav

e Trade. 4 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2003.

Russian immigration

Though Russia controlled parts of the modern United States

and Canada, it left relatively little cultural mark during its

early 19th-century settlement of the Pacific Northwest. Rus-

sian presence is thus largely the product of immigration

between 1881 and 1914. According to the U.S. census of

2000 and the Canadian census of 2001, 2,652,214 Ameri-

cans and 337,960 Canadians claimed Russian descent,

though many of these were members of ethnic groups for-

merly part of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. By

2000, Russians were spread widely throughout the United

States and Canada, though more than 40 percent of Russian

Americans lived in the Northeast and almost one-third of

Russian Canadians lived in Ontario.

Russia is the largest country in the world by landmass,

occupying 6,585,000 square miles, or more than 76 percent

RUSSIAN IMMIGRATION 257

of the total area of the former Union of Soviet Socialist

Republics (USSR). It stretches from eastern Europe across

northern Asia to the Pacific Ocean. Finland, Norway, Esto-

nia, Latvia, Belarus, and Ukraine border Russia to the west;

Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, China, Mongolia, and

North Korea border on the south; the small Russian enclave

of Kaliningrad, west of Lithuania, is bordered by Poland on

the south. In 2002, the population was estimated at

145,470,197. In 1997, the ethnic composition of the coun-

try was 86.6 percent Russian and 3.2 percent Tatar. The

remaining 10 percent was composed of relatively small

numbers of more than a dozen ethnic minorities. The chief

religions were Russian Orthodox and Muslim, although

most Russians claimed no religious affiliation.

During the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, the trans-

formation of Russian state boundaries significantly affected

the character of its immigration. The old heartland of the

Russian peoples was a region in eastern Europe between

modern Kiev, Ukraine, and Moscow. The Slavic peoples

who inhabited the Kiev region were driven northward by the

Mongol invasion of the 13th century. By 1480, Ivan III (the

Great) (r. 1462–1505) established Russian independence of

the Mongols and began to forge a modern state. Ivan the

Terrible (r. 1533–84), grandson of Ivan III, was the first

grand prince to be called “czar” (awe-inspiring) and began

the expansion of the state to include significant numbers of

non-Russian peoples. Between 1667 and 1795, Russia con-

quered huge tracts of eastern Europe, mainly from the king-

doms of Poland and Sweden. These lands included the

peoples of modern Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, eastern

Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine. In 1815, following the

Napoleonic Wars, Russia acquired most of the remainder of

Poland and Moldova (Bessarabia). Throughout the 19th

century, Russia continued to expand, especially into the

Caucasus Mountain region and central Asia, occupying

regions that would later become the modern countries of

Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan,

Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, as well as into

Finland in the north. As a result, during the great age of

immigration from eastern Europe between 1880 and 1920,

more than a dozen major ethnic groups were often classi-

fied by immigration agents as “Russian,” though they were

in fact part of these older nations. The Bolshevik Revolution

of 1917 in Russia, which ushered in the world’s first Com-

munist government, soon spread to most of the surrounding

territories acquired by Russia, leading to the establishment

of a new state, the USSR, or Soviet Union. The USSR was

roughly coterminus with the old Russian Empire prior to

258 RUSSIAN IMMIGRATION

A group of Russian emigrants from Siberia, ca. 1910, stand near a train. Beginning in the 1870s, the more conservative elements

of religious communal groups, such as the Mennonites and Doukhobors, tended to choose western Canada with its greater

accommodation of their religious practices, while those seeking individual freedom and economic opportunity most often chose

the prairies of the United States.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-1782])

the revolution, except for the loss of Finland, Latvia, Esto-

nia, Lithuania, and Poland, which became independent

countries after World War I (1914–18). During World War

II (1939–45), the Soviet Union reoccupied parts of Finland,

Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Moldova and exer-

cised extensive control over the foreign and immigration

policies of the nominally independent countries of Poland,

Czechoslovakia, Hungary, East Germany, and Romania.

Finally, burdened by the ongoing expense of

COLD WAR

conflict with the United States and internal rebellions

throughout Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union collapsed in

1991, leaving 15 separate states, based largely on national

boundaries prior to Russian occupation, each having its own

annual immigration quota to the United States and Canada.

The one important national difference was that each for-

mer Soviet socialist republic had a significant Russian pop-

ulation, descended mainly from bureaucrats and settlers

deliberately placed by the Soviet government to facilitate

control from the Russian capital of Moscow.

Russians who first migrated eastward through Siberia to

Alaska and the Pacific coasts of the United States and

Canada during the late 18th century were mostly trappers,

merchants, and colonial officials. The first permanent Rus-

sian settlement in Alaska was on Kodiak Island in the 1780s,

and Russia, along with Great Britain and the United States,

claimed the Pacific Northwest. Numbers of Russian settlers

in North America were always small, however. In 1867,

when Alaska was sold to the United States, fewer than 1,000

Russians lived in Alaska, but they had established a distinc-

tive cultural presence in coastal regions. Prior to 1880, there

was little Russian immigration to the United States.

Immigration from the Russian Empire during the late

19th and early 20th centuries, on the other hand, was mas-

sive—an estimated 3.2 million between 1881 and 1914—

but included a relatively small proportion of ethnic

Russians (fewer than 100,000). The czarist government

practically forbade the immigration of the non-Jewish pop-

ulation, encouraging instead migration to the burgeoning

industrial cities or to new farmlands in Siberia and the Rus-

sian Far East. About half of Russia’s immigrants were there-

fore Jews, and most of the rest were religious dissenters,

including Old Believers, Mennonites (see M

ENNONITE

IMMIGRATION

) Doukhobors, and Molokans. Slavic peoples

recently incorporated in the Russian Empire, including

Poles, Belarusians, and Carpatho-Rusans; and the descen-

dants of Germans who had homesteaded the southern

farmlands of Russia during the 18th century. The vast

majority of immigrants from the Russian Empire landed in

New York City and settled there or in other industrial cities

of the American North. The pacifist Molokans formed the

only large migration of Russians to the West Coast of the

United States, with about 5,000 immigrating to California

between 1904 and 1912. Although there were about

20,000 Russian Molokans in the United States in 1970—

RUSSIAN IMMIGRATION 259

Main Ethnic Populations in the Former Soviet Republics, 1991

Republics Ethnic Groups

Armenia Armenians, 93 percent

Azerbaijan Azerbaijani, 78 percent; Armenians, 8 percent; Russians, 8 percent

Belarus Belarusians, 78 percent; Russians, 13 percent

Estonia Estonians, 61.5 percent; Russians, 30 percent

Georgia Georgians, 69 percent;Armenians, 9 percent; Russians, 7 percent

Latvia Latvians, 52 percent; Russians, 34 percent

Lithuania Lithuanians, 80 percent; Russians, 9 percent; Poles, 8 percent

Kazakhstan Kazakhs, 42 percent; Russians, 38 percent; Ukrainians, 5 percent

Kyrgyzstan Kirghiz, 52 percent; Russians, 21.5 percent; Uzbeks, 13 percent

Moldova Moldovans, 64 percent; Ukrainians, 14 percent; Russians, 13 percent

Russia Russians, 83 percent

Tajikistan Tajiks, 59 percent; Uzbeks, 23 percent; Russians, 10 percent

Turkmenistan Turkmen, 68 percent; Russians, 13 percent; Uzbeks, 8.5 percent

Ukraine Ukrainians, 71 percent; Russians, 20 percent; Belarusians, 8 percent

Uzbekistan Uzbeks, 69 percent; Russians, 11 percent

As a result of ethnic mixing across several centuries, immigration figures from lands once controlled by Russia are difficult to establish.

There might be a significant Russian component in immigration from any of these 15 countries, though the majority of Russians today

come from Russia itself.

most in Los Angeles and California—they were rapidly

becoming acculturated. Canada especially courted commu-

nal agriculturalists from Russia by promoting group colo-

nization. This led to the establishment of colonies by

Mennonites in Saskatchewan (1870s), the Doukhobors in

Saskatchewan (1890s), and the Molokans in Alberta

(1920s).

After the Bolshevik Revolution, emigration under the

Soviet Union (1917–91) was virtually halted, both because

of even more stringent Soviet controls and because of suspi-

cion of radical ideologies by U.S. and Canadian officials (see

S

OVIET IMMIGRATION

). With the breakup of the Soviet

Union in 1991, Russians were finally allowed to immigrate

freely to the West. Almost a half million Soviets or former

Soviets immigrated to the United States during the 1990s,

probably about 15 percent of them ethnic Russians. The

number of ethnic Russians immigrating continued to grow

through the late 1990s, from 11,529 in 1998 to 20,413 in

2001. Of Canada’s 142,000 immigrants from the former

Soviet Union (2001), 53 percent came between 1991 and

2001.

See also E

STONIAN IMMIGRATION

;H

UTTERITE IMMI

-

GRATION

;J

EWISH IMMIGRATION

;L

ATVIAN IMMIGRATION

;

L

ITHUANIAN IMMIGRATION

; P

OLISH IMMIGRATION

;

U

KRAINIAN IMMIGRATION

.

Further Reading

Hardwick, S. Russian Refuge: Religion, Migration and Settlement on the

North A

merican Pacific Rim. Chicago: University of Chicago

P

ress, 1993.

Jeletzky, T. F., ed. Russian Canadians: Their Past and Present. Ottawa:

Borealis P

ress, 1983.

Kipel, Vitaut. Belarusy u ZshA. Minsk, 1993.

Koch, F

. C. T

he Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, from 1763

to the P

resent. University Park: Pennsylvania State University

Pr

ess, 1977.

Kuropas, Myron B. The U

krainian Americans: Roots and Aspirations,

1884–1954. T

oronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

Long, J. W

. From Privileged to Dispossessed: The Volga Germans,

1860–1917. Lincoln: U

niversity of Nebraska Press, 1988.

M

agosci, Paul R. The Carpatho-Rusyn Americans. New York: Chelsea

House, 1989.

———. O

ur People: Carpatho-Rusyns and Their Descendants in North

A

merica. 3d r

ev. ed. Toronto: Multicultural History Society of

Ontario, 1994.

———.

The Russian Americans. New York: Chelsea House, 1987.

M

orris, R. A. O

ld Russian Ways: Cultural Variations among Three Rus-

sian Gr

oups in Oregon. New York: AMS Press, 1991.

Pilkington, H

ilary. Migration, Displacement and Identity in Post-Soviet

Russia. Ne

w York: Routledge, 1998.

Raeff

, Marc. Russia Abroad: A Cultural History of the Russian Emigra-

tion, 1919–1939. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Smith, B. S., and B. J. B

arnett, eds. R

ussian America: The Forgotten

F

rontier. Tacoma: Washington State Historical Society, 1990.

Starr, S. F., ed. Russia’s A

merican Colony. Durham, N.C.: D

uke Uni-

versity Press, 1987.

Stumpp, K. The German-Russians: Two Centuries of P

ioneering. Lin

-

coln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Rus-

sia, 1971.

Westerman, V. The Russians in America: A Chronology and Fact Book.

Dobbs F

erry, N.Y.: Oceana, 1977.

260 RUSSIAN IMMIGRATION

Salvadoran immigration

Salvadoran immigration to the United States is a new phe-

nomenon, the product of a long civil war that decimated the

country during the 1980s. According to the U.S. census of

2000 and the Canadian census of 2001, 655,165 Americans

and 26,735 Canadians claimed Salvadoran descent. The

Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) estimated in

2000 that another 189,000 Salvadorans were in the coun-

try illegally, though many groups believe that figure to be

low. The number of Salvadoran Canadians is probably twice

as high as the official count. Almost half of Salvadoran

Americans live in the greater Los Angeles area, with signifi-

cant concentrations in New York City, San Francisco, Hous-

ton, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. More than a third of

Salvadoran Canadians live in Ontario, with large concentra-

tions also in Quebec.

El Salvador covers 8,000 square miles in Central Amer-

ica. It is bordered by Guatemala on the west and Honduras

on the north and east. In 2002, the population was estimated

at 6,237,662. The people are largely mestizo (94 percent)

with a small Amerindian population (5 percent). More than

three-quarters of the population is Roman Catholic. El Sal-

vador became independent of Spain in 1821 and of the Cen-

tral American Federation in 1839. A fight with Honduras in

1969 over the presence of 300,000 Salvadoran workers left

2,000 dead. A military coup overthrew the government of

President Carlos Humberto Romero in 1979, but the ruling

military-civilian junta failed to quell a rebellion by leftist

insurgents armed by Cuba and Nicaragua. Right-wing death

squads organized to eliminate suspected leftists were blamed

for thousands of deaths in the 1980s. The administration of

U.S. president Ronald Reagan staunchly supported the gov-

ernment with military aid. After 15 years of conflict, the civil

war ended January 16, 1992, as the government and leftist

rebels signed a formal peace treaty. It has been estimated that

75,000 people died in the conflict.

Emigration from El Salvador was small prior to 1970.

Fewer than 21,000 came to the United States between 1951

and 1970, many from the middle and upper classes, seek-

ing greater economic opportunity and most frequently set-

tling in Florida and California. There was virtually no

immigration to Canada. The civil war in El Salvador, how-

ever, created the greatest refugee crisis in the Western Hemi-

sphere, uprooting a quarter of the country’s population and

leading to massive immigration. More than half left the

country, principally for Mexico, the United States, and

Canada. The United States, heavily involved in the

COLD

WAR

conflict, was throughout most of the period reluctant

to admit Salvadorans as political asylees, though almost

430,000 Salvadorans were admitted between 1981 and

2000. These came mainly from the lower and middle classes

and were generally less well educated. Canada, on the other

hand, began to relax its admissions policies in response to

the war. In March 1981, the Canadian government made it

easier for Salvadorans to gain entry on humanitarian

grounds and two years later allowed them to apply for visas

while outside the country. Of 38,460 Salvadoran immi-

grants in Canada in 2001, only 1,215 arrived before 1981.

4

261

S

On May 20, 1999, the INS relaxed application rules for

permanent resident status for Salvadorans who fled repres-

sive governments during the Salvadoran civil war. As a

result, they were allowed to remain in the United States dur-

ing their application process, and they were not required to

prove that they would suffer extreme hardship if returned

to El Salvador. As a result of these changes, more Salvado-

rans took advantage of the legal application process.

Between 2000 and 2002, annual Salvadoran immigration to

the United States averaged 28,000.

Further Reading

Bonner, Raymond. Weakness and Deceit: U.S. Policy and El Salvador.

New York: Times Books, 1984.

Leslie, Leigh A. “F

amilies F

leeing War: The Case of Central Americans.”

Marriage and Family Review nos. 19, 1–2 (1993): 193–205.

M

ahler

, Sarah J. American Dreaming: Immigrant Life on the Margins.

Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995.

———. Salvadorans in Suburbia: Symbiosis and Conflict. Boston:

Allyn and B

acon, 1995.

Menjívar, Cecilia. Fragmented Ties: Salvadoran Immigrant Networks in

A

merica. B

erkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

———. “Salv

adorans and Nicaraguans: Refugees Become Workers.”

In Illegal Immigration in America: A Reference Handbook. Ed.

D

avid H

aines and Karen E. Rosenblum. Westport, Conn.:

Greenwood Press, 1999.

Mitchell, Christopher, ed. Western Hemisphere Immigration and

U

nited States Foreign Policy. University Park: Pennsylvania State

Univ

ersity Press, 1992.

Montes Mozo, S., and J. J. García Vásquez. Salv

adoran Migration to

the U

nited States: An Exploratory Study. Washington, D.C.:

Hemispheric Migration Project, Center for Immigration P

olicy

and Refugee Assistance, Georgetown University, 1988.

Neuwirth, Gertrude. The Settlement of S

alvadorean Refugees in Ottawa

and Toronto. Ottawa: Employment and Immigration Canada,

1989.

Samoan immigration See P

ACIFIC

I

SLANDER

IMMIGRATION

.

San Francisco, California

San Francisco was the first great immigrant city of the Amer-

ican West, receiving people from around the world during

the C

ALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH

of 1848–49. In 2000, its

metropolitan population of 7,039,362 was one of the most

culturally diverse in the United States. About 30 percent of

its population was Asian and 14 percent Hispanic (see H

IS

-

PANIC AND RELATED TERMS

). The largest non-English eth-

nic groups of the greater metropolitan area (including

Oakland and San Jose) were Mexican (988,841), Irish

(649,758), Chinese (521,645), Italian (422,963), Filipino

(382,224), Vietnamese (156,832), and Asian Indian

(155,121).

Established by Spain as the Mission of Saint Francis of

Assisi in 1776, the settlement remained small until Mexico

gained its independence from Spain in 1821 and a number

of Californians decided to settle the distant territory more

than 2,300 miles from the capital of Mexico City, a village

then named Yerba Buena. England, Russia, and the United

States all sought control of the great natural harbor of San

Francisco Bay, a goal that the United States achieved with

victory in the U.S.-M

EXICAN

W

AR

(1846–48). The discov-

ery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in the Sacramento Valley of Cal-

ifornia in January 1848 transformed the newly acquired

village on the bay. Between 1848 and the granting of state-

hood in 1850, more than 90,000 people migrated to Cali-

fornia, most from within the United States, but large

numbers also arrived from Mexico, Chile, Australia, and

many regions of Europe. Almost all arrived through the port

of San Francisco, turning a sleepy village into a city of

25,000 in less than two years. Among the immigrants were

large numbers of Chinese workers from the impoverished

and flood-ravaged province of Guangdong (Canton). San

Francisco soon became known for its lawlessness and violent

NATIVISM

, especially directed at Chileans, Chinese, and

Irish. By 1870, the city was almost evenly divided between

those born in the United States (76,000) and those born

outside the country (74,000), most of them being Irish,

Chinese, German, and Italian. Bowing to pressure from San

Francisco and California generally, in 1882 Congress passed

the C

HINESE

E

XCLUSION

A

CT

, the first racial immigration

legislation in the United States. Nativist legislation contin-

ued with the G

ENTLEMEN

’

S

A

GREEMENT

(1907) and the

A

LIEN

L

AND

A

CT

(1913).

With increasing government regulations following pas-

sage of the Chinese Exclusion Act and its related extensions,

it became impossible to adequately examine immigrants at

the two-story shed at the Pacific Mail Steamship Company

Wharf, then in use as a processing facility. Following the

example of the E

LLIS

I

SLAND

facility of New York, the gov-

ernment created a new immigration detention center on

A

NGEL

I

SLAND

. Sometimes called “the Ellis Island of the

West,” Angel Island was located on the largest island in San

Francisco Bay, about two miles east of Sausalito. During its

30-year history (1910–40), as many as 1 million immigrants

passed through the facilities—both departing and arriving—

including Russians, Japanese, Asian Indians, Koreans, Aus-

tralians, Filipinos, New Zealanders, Mexicans, and citizens of

various South American countries. Almost 60 percent of

these immigrants were, however, Chinese. The immigration

center on Angel Island was built to stringently enforce anti-

Chinese legislation, rather than to aid potential immigrants.

Whereas the rejection rate at Ellis Island was about 1 percent,

it was about 18 percent on Angel Island, reflecting the clear

anti-Chinese bias that led to its establishment.

Upon arrival in San Francisco, Europeans and first- and

second-class travelers were usually processed on board and

262 SAMOAN IMMIGRATION

allowed to disembark directly to the city. All others were fer-

ried to Angel Island, where the men and women were sepa-

rated before undergoing stringent medical tests, performed

with little regard for the dignity of the immigrant, looking

particularly for parasitic infections. Afterward, prospective

immigrants were housed in crowded barracks, sleeping in

three-high bunk beds, awaiting interrogation. The grueling

interviews, held before a Board of Special Inquiry, includ-

ing two immigrant inspectors, a stenographer, and a trans-

lator, covered every detail of the background and lives of

proposed entrants. Any deviation from details offered by

family members resulted in rejection and deportation. And

if a successful entrant ever left the country, the transcript of

his interrogation was on record for use when he returned.

The whole process could take weeks, as family members on

the mainland had to be contacted for corroborating evi-

dence. In the case of deportation proceedings and their

appeals, an immigrant might spend months or more than a

year on Angel Island. The unsanitary conditions on Angel

Island and degrading treatment of Asian immigrants led to

outrage among progressives, but little was done to alter the

situation before a fire destroyed the administration building

in 1940.

With completion of the Panama Canal in 1914, travel

between the East and West Coast became more efficient,

further contributing to the rapid growth of San Francisco.

As Los Angeles and Oakland began to develop their port

and commercial facilities, San Francisco gradually lost its

preeminent position as the West Coast center of com-

merce.

World War II (1941–45) changed the character of San

Francisco. Becoming increasingly industrial, it attracted

large numbers of African Americans, principally from the

South, altering the racial composition of the city. Japanese

and Chinese citizens continued to demonstrate their loy-

alty during the war, though their fate was radically differ-

ent. Under great suspicion while the United States was at

war with imperial Japan, some 18,000 Japanese Ameri-

cans from the greater San Francisco area were interned as

a result of Executive Order 9066 (see J

APANESE INTERN

-

MENT

,W

ORLD

W

AR

II). With China as an ally, however,

Chinese San Franciscans earned greater respect and a wider

number of job opportunities. By the 1960s, the Chinese

were moving into the cultural mainstream, and the

Japanese followed soon after. After World War II, San

Francisco increasingly became a destination for Mexican

and Central American immigrants who replaced the Irish

and Italians steadily moving out of the inner city. In the

20th century, minority politics came to dominate San

Francisco. While the majority of Californians supported

anti-immigrant propositions, such as 187, 209, and 227

(see P

ROPOSITION

187), San Franciscans consistently

opposed them and earned a reputation for generally lib-

eral politics.

Further Reading

Berchell, Robert A. T

he San Francisco Irish, 1848–1880. Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1980.

Broussard, Albert S. Black San Francisco: The Struggle for Racial Equal-

ity in the

W

est, 1900–1954. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas,

1993.

Chen, Y

ong. Chinese San Francisco, 1850–1943: A Trans-Pacific Com-

munity

. S

tanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2000.

Chinn, Thomas. B

ridging the Pacific: San Francisco Chinatown and Its

People. S

an Francisco: Chinese Historical Society of America,

1989.

Cinel, D

ino

. From Italy to San Francisco: The Immigrant Experience.

Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1982.

Gumina, Deanna Paoli. The Italians of San Francisco, 1850–1930.

New York: Center for Migration Studies, 1978.

Jain, U

sha R. The G

ujaratis of San Francisco. New York: AMS Press,

1989.

La B

rack, Bruce. The Sikhs of Northern California, 1904–1975: A

Socio-H

istoric S

tudy. New York: AMS Press, 1988.

Wong, B. P

. Ethnicity and Entrepreneurship: Immigrant Chinese in the

San F

rancisco Bay Area. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1996.

Yung, J

udy. Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San

Fr

ancisco. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Schwenkfelder immigration

The Schwenkfelders were a small, pietistic sect that emi-

grated from southern Germany and lower Silesia in the Aus-

trian Empire beginning in 1731. After being persecuted for

two centuries, and denied the right to Christian burial, they

decided to follow like-minded German immigrants to the

P

ENNSYLVANIA COLONY

where religious freedom was guar-

anteed. They arrived in Philadelphia in six migrations

between 1731 to 1737, with the largest group of 200 sail-

ing from Rotterdam in 1734. They settled farmsteads

around Philadelphia, especially in modern Berks and Lehigh

Counties. By 2003, almost all Schwenkfelders had joined

more established Christian denominations, though many

still claimed to be followers of the old doctrine.

Schwenkfelders followed the teachings of Caspar

Schwenckfeld von Ossig (1489–1561), a devout Catholic

and member of the Silesian nobility. He was drawn to Mar-

tin Luther’s reform teachings but disagreed with him over

the exact nature of the Lord’s Supper and the baptism of

infants. Schwenckfeld believed that the Bible should not be

literally interpreted or used as a “paper pope” but rather

that believers should trust the Holy Spirit for insight into

its meaning. Family was central to Schwenkfelder worship,

with house churches the norm. As a result, the Society of

Schwenkfelders was loosely organized, and its members

freely associated with more established churches, where they

could share their gifts of spiritual insight. In 2003, there was

still an organized church, consisting of five congregations

and about 2,600 members associated with the United

Church of Christ, though many who claim Schwenkfelder

SCHWENKFELDER IMMIGRATION 263