Powell J. Encyclopedia Of North American Immigration

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Further Reading

Baker, Lee D. From Savage to Negro: Anthropology and the Construction

of R

ace, 1896–1954. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1998.

Banton, M

ichael, and J

onathan Harwood. The Race Concept. New

Yor

k: Praeger, 1975.

Driedger, Leo, and Shiva S. Halli. Race and Racism: Canada’s Chal-

lenge. Montr

eal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2000.

Gossett, Thomas. Race: The History of an Idea in America. New York:

Oxford U

niversity Press, 1997.

Grieco, Elizabeth M., and Rachel C. Cassidy. “Overview of Race and

Hispanic Origin: Census 2000 Brief.” Washington, D.C.: U.S.

Census Bureau, C2KBR/01–1, March 2001.

Hannaford, Ivan. Race: The History of an Idea in the West. Baltimore:

J

ohns H

opkins University Press, 1996.

Lee, Sharon M. Using the N

ew Racial Categories in the 2000 Census, A

KIDS C

OUNT/PRB Report on Census 2000. Washington, D.C.:

Annie E. Casey Foundation and the P

opulation Reference

Bureau, March 2001.

Pollard, Kelvin M., and William P. O’Hare. “America’s Racial and Eth-

nic Minorities.” Population Bulletin 54, no. 3 (September 1999).

S

or

ensen. E., et al. Immigrant Categories and the U.S. Job Market.

Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press, 1992.

S

pain, D

aphne. America’s Diversity: On the Edge of Two Centuries.

Washington, D.C.: Population Reference Bureau, 1999.

S

tatistics Canada. “1996 Census: E

thnic Origin, Visible Minorities.”

Statistics Canada Web site. Available online. URL: http://www.

statcan.ca/Daily/English/980217/d980217.htm.

U.S. Office of Management and Budget. “Revisions to the Standards

for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity.”

Federal Register 62, no. 210 (October 30, 1997): pp.

58,782–58,790.

racism

Racism is a belief that humans can be distinctly categorized

according to external characteristics and that the various races

are fixed and inherently different from one another. It has

been an essential feature in defining intercultural relations in

North America since the arrival of the Spanish in the early

16th century and the ideological foundation of English and

French dominance. With a few exceptions, early European

settlers believed in their own superiority, which justified the

forced labor or enslavement of Native Americans and Africans

and the establishment of cultural norms to which immigrants

were expected to conform. Though racism implies a founda-

tion of biological determinism, there is not a clear line

between it and ethnocentrism, which judges the value of other

peoples and cultures according to the standard of one’s own

culture (see

NATIVISM

). Racism operated in some form against

most immigrant groups in North America, with the Irish,

Jews, Italians, and Slavic peoples initially viewed as inher-

ently different by members of the predominant English or

French cultures and thus justifiably subject to menial service

at low wages and expected to conform to the predominant

cultural norms. In its most extreme form, racism led to insti-

tutionalized discrimination against African Americans. Fol-

lowing U.S. civil rights reforms of the 1960s and a general

improvement in economic conditions for U.S. and Canadian

immigrants, institutional and cultural racism declined. Vary-

ing degrees of racism are still common, however, having been

most commonly exposed in high-profile law enforcement

cases such as the 1997 beating of Haitian immigrant Abner

Louima. Throughout the 1990s, heightened racial conscious-

ness led to more frequent charges of racism in government,

business, and the press.

Throughout the ancient and medieval world, humans

were not identified by race. People naturally noticed external

differences (phenotypes)—most notably skin color; hair

color and type; shape of head, nose, and teeth; and general

body build—that roughly corresponded to the later-defined

“three races” of European/white/Caucasian; African/

black/Negroid; and Asian/yellow/Mongoloid. Recognition of

these differences in phenotypes alone did not constitute

racism, however, as Africans, Asians, Native Americans, and

Europeans were all willing to enslave and otherwise take

advantage of peoples who looked much as they did. Extreme

prejudice most often centered instead on cultural traits asso-

ciated with the peoples of particular geographic regions, as in

the case of the Roman Cicero railing against British slaves

because they were “so stupid and so utterly incapable of being

taught.” The modern concept of races, the foundation of

racism, began to emerge as Europeans from the 15th cen-

tury onward began to explore and dominate remote regions

of the world, encountering cultures vastly different in cus-

toms, belief systems, and levels of development.

Until the mid-17th century, however, European ethno-

centrism still was not primarily motivated by race. The

English military governor of Munster, Sir Humphrey

Gilbert, had no qualms about brutally exterminating white

Irish men, women, and children in Ireland in 1569, cutting

off their heads and lining the path to his tent with them as

an example to others. Indentured servants (see

INDEN

-

TURED SERVITUDE

) of every race, ethnicity, and nationality

were harshly treated. Until the 1650s, it was still possible for

Africans in English colonies to serve their indenture, become

landowners, and even be masters to European servants.

SLAVERY

as a legal institution associated with race emerged

only with the development of slave codes from 1661, which

increasingly referred to racial distinctions in limiting the

freedoms of Africans. At about the same time, the term race

began to be used in a modern sense to designate peoples

with common distinguishable physical characteristics.

This

sense of the term did not become widespr

ead, however, until

the 18th century when systematic classification of peoples

seemed to give scientific credence to such divisions (see

RACIAL AND ETHNIC CATEGORIES

).

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by means of nat-

ural selection, put forward in On the Origin of Species

244 RACISM

(1859), ironically worked both to support and undermine

racism. In the short term, it suggested that some races had

not evolved as far as others and thus were intellectually or

morally inferior. This pseudoscientific interpretation of Dar-

win was used to justify British and American imperial con-

quests, as well as continued discrimination against Native

Americans and African Americans and the exploitation of

non-European laborers such as the Chinese, Japanese, and

Asian Indians. In the long term, however, natural selection’s

focus on adaptation suggested why people living in similar

geographic regions developed similar physical characteris-

tics, despite living thousands of miles apart. Based on the

science of genetics, which was not developed until the 20th

century, it has become generally accepted that differences in

the genetic structure of humans (genotypes) are far more

meaningful than differences in external features (pheno-

types) and that all human beings are biologically part of the

same species, with few consequential differences. The tradi-

tional identification of race by skin color is no more mean-

ingful than identification on the basis of blood type,

dentition, or sickle-cell traits, all of which cut across tradi-

tional racial lines.

Further Reading

Aarim-Heriot, Najia. C

hinese Immigrants, African Americans, and

Racial Anxiety in the United States, 1848–82. Champaign: Uni-

versity of I

llinois Press, 2003.

“Abercrombie Pulls ‘Racist’ Asian Theme T-shirts.” CNN.com. April

19, 2002. Available online. URL: http://www.cnn.comm/2002/

BUSINESS/asia/04/19/sanfran.abercrombie,reut/index.html.

Accessed April 19, 2002.

Almaguer, Tomás. Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White

S

upremacy in California. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1994.

B

anton, M

ichael, and Jonathan Harwood. The Race Concept. New

Yor

k: Praeger, 1975.

Boyko, John. Last Steps to Freedom: The Evolution of Canadian Racism.

2d ed. Winnipeg, Canada: J. Gordon Shillingford, 1998.

Chase, Allan. The Legacy of Malthus:

The Social Costs of the N

ew Sci-

entific Racism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977.

Conrad, Earl. The Invention of the Negro. New York: Paul S. Eriksson,

1967.

Cose, E

llis. A N

ation of Strangers: Prejudice, Politics, and the Populating

of America. N

ew York: Morrow, 1992.

Daniels, R

oger. The Politics of Prejudice. New York: Atheneum, 1968.

Driedger

, Leo, and Shiva S. Halli. Race and Racism: Canada’s Chal-

lenge. Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2000.

F

erguson, T

ed. A White Man’s County. Toronto: Doubleday, 1975.

Gould, S

tephen J. The Mismeasure of Man. Rev. ed. New York: W. W.

Nor

ton, 1996.

Haas, Michael. Institutional Racism: The Case of Hawaii. Westport,

Conn.: P

raeger

, 1992.

Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism,

1860–1925. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Pr

ess,

1955.

Jordan, Winthrop D. White over Black: American Attitudes toward the

Negro, 1550–1812. New York: W.

W. Norton, 1977.

Laquian, Eleanor, Aprodicio Laquian, and Terry McGee, eds. The

Silent D

ebate: Asian Immigration and Racism in Canada. Vancou-

ver: I

nstitute of Asian Research, University of British Columbia,

1998.

Massey, Douglas S. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of

the U

nder

class. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993.

McClain, Charles J. In Search of Equality:

The Chinese S

truggle against

Discrimination in Nineteenth-Century America. Berkeley: Univer-

sity of California Pr

ess, 1994.

McClellan, Robert. The Heathen Chinese: A Study of American Attitudes

to

war

d China. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1971.

Miller

, Stuart. The Unwelcome Immigrant: The American Image of the

Chinese, 1785–1882. Berkeley: Univ

ersity of California P

ress,

1969.

Olson, James. Equality Deferred: Race, Ethnicity, and Immigration in

America, since 1945. Belmont, Calif.: W

adsworth, 2003.

railways and immigration

Railways were integral to immigration in several ways. First,

they were the physical means by which the vast majority of

European immigrants made their way from interior regions

RAILWAYS AND IMMIGRATION 245

This cartoon, published in California during the 1860s,

suggests the racist assumptions of many Americans and

Canadians in the 19th century. Note the distinctly simian

(monkey- or apelike) features of the Irishman (left) and the

characterization of the Chinese man (right). In 1883, Prime

Minister John A. Macdonald informed the Canadian parliament

that he was “sufficient of a physiologist” to understand that

Chinese and European Canadians could not “combine and

that no great middle race can arise from the mixture of the

Mongolian and the Arian.”

(Library of Congress, Prints &

Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-22399])

of Britain, the German states, and the Austrian and Russian

Empires to port cities like Liverpool, in England, and Ham-

burg, in Germany. Prior to the development of the railroad,

land travel to a distant port was slow, frequently dangerous,

and often unrealistic. Once in North America, the railroad

efficiently and inexpensively transported immigrants to

places of opportunity far away from ports, including indus-

trial areas, such as Cleveland, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan;

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; St. Louis, Missouri; and Chicago,

Illinois, and the agricultural lands of the interior. Earlier

travel by horse and wagon or on foot were both expensive

and impractical for most immigrants, especially as they were

undertaken in a foreign land and across places where one’s

language was not spoken. Finally, the railroad was essential

for bringing supplies to the interior and moving out wheat,

cotton, cattle, gold, coal, and other commodities. For the

West to be productive, it had to be connected to the

Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coast ports.

Steam-powered railways were developed in Britain at

the beginning of the 19th century. By the late 1820s, sub-

stantial railway lines were established in both Britain and the

eastern United States. Within the next 10 years railway lines

were constructed in Canada and most of western Europe.

In 1869, the first transcontinental railroad was completed in

the United States; in 1885, the last spike in the Canadian

Pacific Railway was driven in the Monashee Mountains of

British Columbia, laying the foundation for westward

expansion to the interior prairies and the Pacific.

The rapid growth of railways in the United States and

Canada during the 19th century provided many employ-

ment opportunities for immigrants and a means of dispers-

ing them throughout the country. The Central Pacific

Railroad, as it pushed to complete the first transcontinental

railroad in the United States, employed more than 10,000

Chinese laborers. In 1850, American railway lines stretched

8,683 miles, all east of the Mississippi River. By 1890, there

were 163,597 miles of track, including 70,622 miles west

of the Mississippi. Such large capital investments necessi-

tated cheap labor and allowed national economies to main-

tain stability while absorbing thousands of immigrants.

246 RAILWAYS AND IMMIGRATION

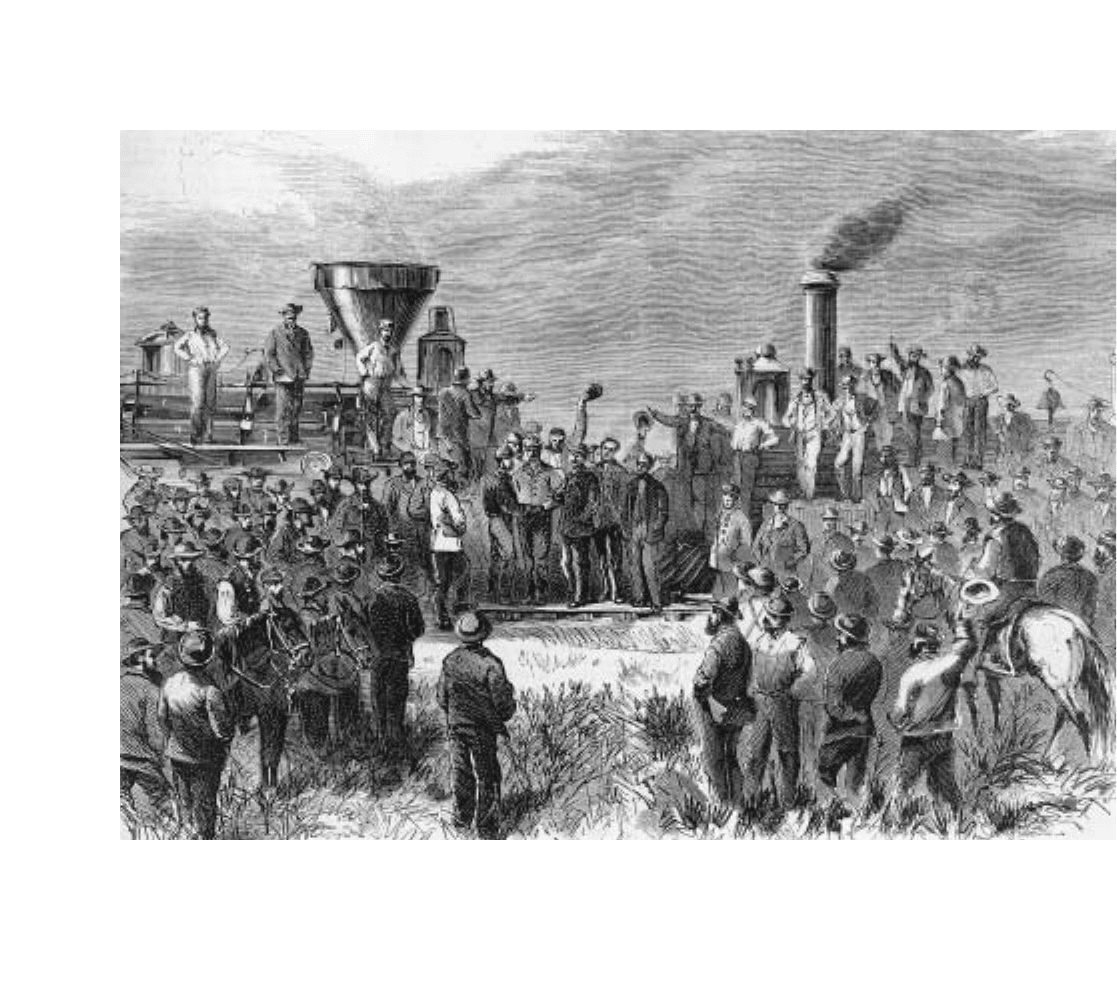

This engraving shows the completion of the Pacific Railroad and the meeting of locomotives of the Union and Central Pacific

lines.The completion of the first transcontinental railroad in the United States in the summer of 1869 made possible the settling

of the great central prairies.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [LC-USZ62-116354])

Masses of Irish immigrants who could not afford to start

farming, instead accepted backbreaking jobs with the rail-

way. Beginning in 1862, Irish workers were employed by the

Union Pacific to construct the eastern section of the first

U.S. transcontinental railway. The western section of the

line was constructed almost entirely by Chinese immigrants

from California employed by the Central Pacific. Along

with large numbers of Greeks, Italians, Japanese, and Rus-

sians, Irish and Chinese immigrants continued to play a

major role in railway construction throughout the United

States and Canada. Once completed, railways increased

worker mobility across the nation. Wealthier immigrants,

usually of German origin, could arrange rail passage from

their arrival city to Midwestern states, such as the Dakotas,

where free homesteads were available.

When large projects demanded an immediate labor

force, workers could be contracted by labor brokers from

immigrant population centers, then shipped by rail any-

where in the country. The ready supply of immigrant work-

ers greatly accelerated railway and industrial growth in the

19th century. In Canada, with fewer concentrations of

laborers, short-term labor contracts were issued to workers

from eastern Europe as late as 1913.

Railway companies also played a direct role in promot-

ing immigration to North America. Before construction

began, most railway companies received federal land grants

along their proposed route. As early as 1855, the Illinois

Central began to recruit immigrants from Britain, Germany,

and Scandinavia to encourage population growth on the

granted land. In the 1870s and 1880s, other companies fol-

lowed suit, such as the Northern Pacific, which actually

established its own Bureau of Immigration. Companies sent

recruiting agents to Europe with newsletters and brochures

to entice settlers to move to preplanned communities, offer-

ing free passage and discount land to immigrants who would

agree to relocate. In Canada, the Canadian Pacific Railroad

used similar techniques in London to market its massive fed-

eral land grants to British immigrants. Consequently, rail-

ways established specific patterns of ethnic settlement along

their lines.

At the turn of the 20th century, an influx of principally

male Mexican workers flooded the agricultural and railway

labor markets of the southwestern United States. Railway

worker camps formed the foundation for many modern

Mexican-American communities. With the rise of the auto-

mobile culture in the 20th century, railways waned as the

primary means of internal transportation in the United

States but continued to provide a frequently undetectable

method of crossing America’s southern border.

With the Canadian prairies filling more slowly than

those in the United States, the role of the railroad remained

more pivotal. With the dramatic decline of immigrant

admissions and rise in alien deportations during World War

I (1914–18), the Canadian government tried several means

of attracting agriculturalists and domestics, who were in

high demand. Its first choice of source country was clearly

Great Britain, but the E

MPIRE

S

ETTLEMENT

A

CT

was rela-

tively unsuccessful in attracting the agricultural immigrants

desperately needed for developing the prairies. More suc-

cessful was the Railway Agreement of 1925, which autho-

rized the Canadian Pacific and Canadian Northern railways

to recruit agriculturalists and farm laborers from southern

and eastern Europe, whose immigration to Canada was at

that time “non-preferred.” Always seeking more customers,

the railroads actively advertised in Europe and between

1925 and 1929 brought more than 185,000 immigrants to

the agricultural west. The groups that most benefited from

this last phase of direct railway settlement were Germans

from both central Europe and Russia, Mennonites, Ukraini-

ans, Poles, and Hungarians.

See also N

EW

O

RLEANS

, L

OUISIANA

.

Further Reading

Dempsey, Hugh A., ed. The CPR

West: The Iron Road and the Making

of a Nation. Vancouver, Canada, and Toronto: Douglas and

McIntyre, 1984.

Eagle, J

ohn A. The C

anadian Pacific Railway and the Development of

Wester

n Canada, 1896–1914. Kingston, Montreal, and London:

McGill–Queen’

s University Press, 1989.

England, Robert. The Colonization of Western Canada: A Study of Con-

temporary Land Settlement, 1896–1934. London: P.S. King,

1936.

G

ordon, Sarah. Passage to Union: How the Railroads Transformed Amer-

ican Life, 1829–1929. Chicago: Ivan Dee, 1996.

Gates, Paul Wallace. The Illinois Central R

ailroad and Its Colonization

Work. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1934.

Holbrook, Stewart H. The Story of American Railroads. New York:

C

r

own, 1947.

O’Connor, Richard. Iron Wheels and Broken Men. New York: Put-

nam, 1973.

Raleigh, Sir Walter (ca. 1552–1618) explorer,

courtier, man of letters

Although a man of many accomplishments, Sir Walter

Raleigh is best known as an explorer and the founder of

R

OANOKE COLONY

(1585), England’s first colonial settle-

ment in the Americas. Though the venture failed, Raleigh

was able to challenge Spain’s supremacy in the New World,

and the settlers of Roanoke returned with valuable informa-

tion that would later aid colonists in successfully establish-

ing an English presence in Virginia.

Born in Devonshire, as a young man Raleigh attended

Oriel College, Oxford, before joining the French Huguenot

army in 1569. During the 1570s, he gained distinction as a

poet and man of letters in London. In 1578 he joined his

half brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, in search of the North-

west Passage but ended in attacking Spanish holdings in the

Americas. After Raleigh spent two years fighting the Irish

RALEIGH, SIR WALTER 247

(1580–81), Queen Elizabeth came to recognize him as an

expert on Irish affairs, and he quickly rose in royal favor.

Extravagant and arrogant, he was widely disliked at court

but was knighted in 1584 and eventually rose to the position

of captain of the queen’s guard.

After Gilbert’s death in 1583, Raleigh was given his char-

ter to claim American lands in the name of the queen. She

also grudgingly gave him a ship and a small sum of money.

Though Raleigh remained in London to oversee the financing

of the operation, his men made three unsuccessful attempts to

establish Roanoke colony on the outer banks of the Carolinas.

In and out of favor with Queen Elizabeth, Raleigh did gain

permission to lead an expedition in 1595 to Guiana (modern

Venezuela), where he believed he had found extensive deposits

of gold, as he wrote in The Discov

ery of the Large, Rich, and

B

eautiful Empire of Guiana . . . (1596). Upon Elizabeth’s death

in 1603, he was convicted of treason. The ne

w king, James I,

stripped Raleigh of his titles and imprisoned him in the Tower

of London for 13 years. He used the time to write his monu-

mental The History of the Wor

ld (1614). Raleigh finally con-

vinced the cash-strapped king to release him in or

der to

pursue English claims in Guiana. Raleigh’s final expedition

(1617) produced no wealth, however, and he was beheaded

for treason the following year.

Further Reading

Quinn, David Beers. Raleigh and the British Empire. London: English

Univ

ersities Press, 1962.

Raleigh, Walter. The Works of Sir Walter Ralegh. 8 vols. 1829. Reprint,

N

e

w York: Burt Franklin, 1965.

Wallace, Willard M. Sir Walter Raleigh. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton

U

niv

ersity Press, 1959.

Red River colony

The Red River colony, established by T

HOMAS

D

OUGLAS

,

Lord Selkirk, in 1812, was the first farming settlement in

western British North America. Though a collective failure

economically and politically, it demonstrated that individuals

could successfully farm the western prairies, laying the foun-

dation for the settlement of Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

Selkirk, a philanthropist who had established smaller

settlements on Prince Edward Island and at Baldoon,

Ontario, acquired controlling interest of the Hudson’s Bay

Company between 1808 and 1812 with an eye toward set-

tling Scottish crofters (tenant farmers with very small hold-

ings) who had been driven from their Highland farms. In

1811, he purchased 116,000 square miles of Rupert’s Land

from the company, extending from Lake Winnipeg in the

north to the headwaters of the Red River in the south. In

return for this immense tract, almost as large as Britain and

Ireland combined, Selkirk was responsible for providing 200

company men with a 200-acre pension when they retired.

Crofters were required to pay 10 pounds each for trans-

portation and a year’s supplies, with a grant of 100 acres of

land at five shillings per acre to each head of household.

Such bounty seemed too good to be true, and it was.

The transplanted Scots were under constant threat from the

Sioux and the Métis (Canadians of native and mostly French

parentage), who in 1817 proclaimed the region as their own

“nation.” The newcomers had no proper tools for farming

the tough prairie sod, and when they did manage to raise

crops or cattle, ferocious winters, wolves, grasshoppers,

blackbirds, and floods were there to steal the fruits of their

labor. The placement of 270 Scots in the Red River settle-

ment (1812–16) also led to violent opposition from the

North West Fur Company, whose trade routes were

infringed. A protracted legal struggle cost Selkirk much of

his fortune. In addition, the colony was poorly governed;

Selkirk himself only visited once, in 1817. Not surprisingly,

the Red River settlement grew slowly.

In 1821 the population was a little more than 400.

More than half were Scots, but there was a significant num-

ber of Irish and smaller numbers of French Canadians and

Swiss. As the population grew, the character of the colony

changed dramatically. By the mid-1820s, most of the origi-

nal settlers had died or departed for the United States or

Upper Canada. By the 1830s, the population was composed

almost entirely of Métis. When they rebelled against intru-

sion by the Canadian government in 1869–70, there were

5,754 of mixed Native American–French descent and 4,083

of mixed Native American–British descent. From this con-

flict emerged the province of Manitoba and parts of the

Northwest Territories.

Further Reading

Friesen, Gerald. The Canadian Prairies: A History. Toronto: Univer-

sity of T

oronto Press, 1984.

MacEwan, Grant. Cornerstone Colony: Selkirk’s Contribution to the

C

anadian W

est. Saskatoon, Canada: Western Producer Prairie

Books, 1977.

M

or

ton, W. L. Manitoba: A History. Rev. ed. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press, 1967.

P

ritchett, J. P. The Red River Valley, 1811–1849: A Regional Study. New

H

av

en, Conn.: Yale University Press, Ryerson Press, 1942.

Refugee Act (United States) (1980)

The Refugee Act of 1980 formed the basis of refugee policy

in the U

nited States until 1996. It declared that American

policy was to “respond to the urgent needs of persons sub-

ject to persecution” by any of the following means “where

appropriate”:

Humanitarian assistance for their care and maintenance

in asylum areas, efforts to promote opportunities for reset-

tlement or voluntary repatriation, aid for necessary trans-

portation and processing, admission to this country

248 RED RIVER COLONY

[United States] of refugees for special humanitarian con-

cern to the United States, and transitional assistance to

refugees in the United States. The Congress further

declares that it is the policy of the United States to encour-

age all nations to provide assistance and resettlement

opportunities to refugees to the fullest extent possible.

The Refugee Act was designed to bring U.S. law into

compliance with international treaty obligations, particu-

larly the United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of

Refugees, to which the United States had acceded in 1968.

The act therefore separated refugee and immigration policy

and adopted the broader UN definition of a refugee as

Any person who . . . owing to a well-founded fear of

being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality,

membership of a particular social group or political

opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is

unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail him-

self of the protection of that country; or who, not having

a nationality and being outside the country of his for-

mer habitual residence . . . is unable or, owing to such

fear, is unwilling to return to it.

Refugees were exempted from the immigrant preference sys-

tem, as were immediate relatives. The act provided for quo-

tas to be reviewed annually. In 1980, 50,000 new refugee

applicants were admitted. The number rose to 110,000 by

the mid-1990s.

Currently, the president, in consultation with Congress,

establishes the annual refugee quota from each geographical

area. The Department of State is then responsible for deter-

mining specific countries from which refugees will be

accepted. In 1997, for instance, 78,000 refugees were per-

mitted to enter the United States, with slots for Africa

(7,000), East Asia (10,000), Eastern Europe and the former

Soviet Union (48,000), Latin America and the Caribbean

(4,000), and the Near and Middle East (4,000) and another

5,000 spots allocated as a reserve for trouble areas.

See also

REFUGEE STATUS

.

Further Reading

Kennedy, Edward M. “Refugee Act of 1980.” International Migration

Review 15 (1981): 141–156.

Loescher, G

il, and John A. Scanlan. Calculated Kindness: Refugees and

America

’s Half-Open Door, 1945–Present. New York: Free Press,

1986.

M

itchell, Christopher

, ed. Western Hemisphere Immigration and

United States F

oreign Policy. University Park: Pennsylvania State

U

niversity Press, 1992.

Refugee Relief Act (United States) (1953)

Enacted on August 7, 1953, the Refugee Relief Act (RRA)

authorized the granting of 205,000 special nonquota visas

apportioned to individuals in three classes, along with

accompanying members of their immediate family, includ-

ing refugees (those unable to return to their homes in a com-

munist or communist-dominated country “because of

persecution, fear of persecution, natural calamity or military

operations”), escapees (refugees who had left a communist

country fearing persecution “on account of race, religion,

or political opinion”), and German expellees (ethnic Ger-

mans then living in West Germany, West Berlin, or Austria

who had been forced to flee from territories dominated by

communists). Visas were allotted to the following groups:

German expellees (55,000); Italian refugees (45,000); Ger-

man escapees (35,000); escapees residing in North Atlantic

Treaty Organization (NATO) countries, Turkey, Sweden,

Iran, or Trieste (25,000, including second, third, and fourth

preferences); Greek refugees (17,000, including second,

third, and fourth preferences); Dutch refugees (17,000,

including second, third, and fourth preferences); refugees

who had taken refuge in U.S. consular offices in East Asia

but were not indigenous to the region (2,000); refugees who

had taken refuge in U.S. consular offices in East Asia and

were indigenous to the region (3,000); Chinese refugees

(2,000); and those qualifying for aid from the United

Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in

the Near East (2,000). The act also provided for 4,000 non-

quota visas for eligible orphans under 10 years of age. An act

of September 11, 1957 reassigned unused visas from the

1953 quota.

See also

REFUGEE STATUS

.

Further Reading

Divine, Robert. American Immigration Policy, 1924–1952. New

Haven, Conn.: Yale U

niversity Press, 1957.

Hutchinson, E. P. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

Loescher, Gil, and John A. Scanlan. Calculated Kindness: Refugees and

A

merica

’s Half-Open Door, 1945–Present. New York: Free Press,

1986.

Proudfoot, Malcolm J. European Refugees, 1939–1952: A S

tudy in

Forced Population Movement. London: Faber and Faber, 1957.

Vernant, J

acques. The Refugee in the Post-War World. New Haven,

Conn.: Yale Univ

ersity Press, 1953.

refugee status

A refugee is a special category of immigrant not subject to

regular immigration quotas. In international law, a refugee is

defined as a person fleeing natural disaster or past or future

persecution on the basis of race, culture, or political or reli-

gious beliefs. Individual countries grant asylum—the right

to legally resettle—according to national interests as embod-

ied in domestic legislation. Because of international treaty

obligations, both the United States and Canada provide

REFUGEE STATUS 249

special treatment to those deemed refugees, including eco-

nomic assistance in first countries of asylum and selective

resettlement in North America. Refugees have a legal status

enabling them to work and receive welfare benefits, whereas

asylum seekers are considered temporary guests who may at

any point be declared illegal aliens. The United States has

consistently resettled more refugees than any other country,

though there has been considerable controversy over the

terms of American policy.

Although Thomas Jefferson spoke eloquently on behalf

of asylum for “unhappy fugitives from distress,” the United

States followed no consistent refugee policy until after

World War II (1939–45). With virtually open immigration

to the United States prior to World War I (1914–18), it was

not in most cases necessary to specially designate refugees.

Thousands of religious and revolutionary exiles who might

today qualify for refugee status were admitted to the young

republic after 1776 but with no special legislative provisions.

The American government implicitly recognized the refugee

status of men and women who had been convicted of polit-

ical crimes by excluding them from legislation aimed at pro-

hibiting the immigration of criminals (1875, 1882, 1891,

1903, 1907, 1910). Shortly after World War II (see W

ORLD

W

AR

II

AND IMMIGRATION

), a number of measures admit-

ted refugees according to special circumstances: President

Harry S. Truman’s presidential directive of 1945 admitted

42,000 war refugees; the W

AR

B

RIDES

A

CT

(1946) qualified

wives and children of U.S. servicemen to enter; and the D

IS

-

PLACED

P

ERSONS

A

CTS

(1948, 1950) admitted more than

400,000 homeless Europeans. In 1951, the United Nations

Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees established

an international definition and prohibited forcible repatria-

tion (refoulement), though it did not require any country

to resettle refugees. The United States did not sign the Con-

vention Relating to the Status of Refugees but devised

similar policies through domestic legislation. The M

C

C

AR

-

RAN

-W

ALTER

I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATURALIZATION

A

CT

(1952) did not specifically address refugee status, leading to

passage of the R

EFUGEE

R

ELIEF

A

CT

(1953), granting asy-

lum in the United States to those fleeing communist perse-

cution. This formed the primary basis for establishing

refugee status in the United States throughout the

COLD

WAR

(1945–91) and was embodied in the permanent

amendment of the I

MMIGRATION AND

N

ATIONALITY

A

CT

in 1965, which established a preference class for those who

“because of persecution or fear of persecution . . . have fled

from any Communist or Communist-dominated country or

area, or from any country within the general area of the

Middle East.” From the mid-1950s through 1979, less than

one-third of 1 percent of refugee admissions were from non-

communist countries, and as late as 1987, 85 percent of

refugees were from the communist countries of Cuba, Viet-

nam, Laos, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Poland, Russia, and

Romania.

The R

EFUGEE

A

CT

(1980), designed to bring U.S. law

into compliance with international treaty obligations, sepa-

rated refugee and immigration policy and adopted the

broader UN definition of a refugee, leading to a great influx

of immigrants. Nevertheless, the disparity between treat-

ment of 130,000 Cubans who were granted refugee status

following the M

ARIEL

B

OATLIFT

(1980) and the forcible

return of thousands of Haitians, Guatemalans, and Salvado-

rans fleeing right-wing dictatorships was evident. Despite

the broader provisions of the Refugee Act, the administra-

tion of President Ronald Reagan reduced refugee admissions

by two-thirds and continued to favor those from communist

countries. The I

LLEGAL

I

MMIGRATION

R

EFORM AND

I

MMI

-

GRANT

R

ESPONSIBILITY

A

CT

(1996) further expanded the

definition of a refugee to include anyone fleeing “coercive

population control procedures,” a phrase specifically aimed

at China.

Canadian policy after World War II favored interna-

tional cooperative efforts to assist refugees in the country of

first asylum. The Canadian I

MMIGRATION

A

CT

of 1952

250 REFUGEE STATUS

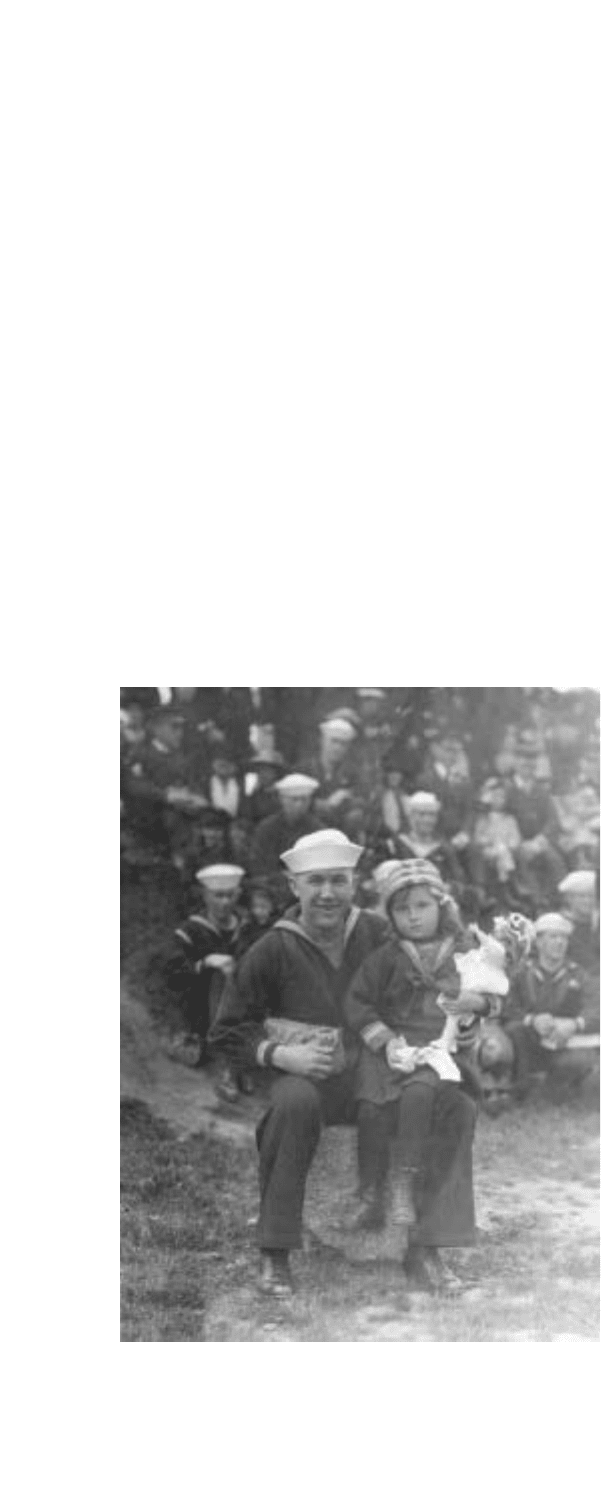

A refugee child is adopted by a U.S. sailor in May 1918.

Although the American and Canadian governments had

admitted refugees since the early colonial period, neither

developed an official refugee policy until the 1950s.

(National

Archives #72-135418)

provides for Canadian resettlement of those who qualify

under the United Nations Convention agreement, though

candidates must pass through an extensive process handled

by the Convention Refugee Determination Division of the

Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB).

Further Reading

Dirks, Gerald E. Canada’s Refugee Policy: Indifference or Opportunism?

Montr

eal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1977.

H

utchinson, E. P. Legislative History of American Immigration Policy,

1798–1965. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1981.

Loescher

, G

il, and John A. Scanlan. Calculated Kindness: Refugees and

America

’s Half-Open Door, 1945–Present. New York: Free Press,

1986.

S

immons, Alan B. “Latin American M

igration to Canada: New Link-

ages in the Hemispheric Migration and Refugee Flow Systems.”

International Journal 48 (Spring 1993): 282–309.

religion and immigration

The quest for religious freedom has played an important

role in immigration to North America from the 17th cen-

tury to the present day. In some cases, it has been the pre-

eminent reason for leaving homelands in which religious

persecution was endemic. In more cases, religious freedom

was one issue among others, as people sought both personal

freedoms and economic opportunities not available in their

home countries.

The earliest settlers to come to North America mainly

for religious reasons were the Pilgrims (see P

ILGRIMS AND

P

URITANS

), who settled in Plymouth Bay, Massachusetts.

Having already separated from the Church of England and

migrated to Holland in 1610, it was then easier for them

to choose the drastic step of leaving Europe forever in

1620. The much larger migration of Puritans in the 1630s

and 1640s, led by J

OHN

W

INTHROP

, hoped to build a

“city upon a hill,” a model community where full citizen-

ship was reserved for members of a reformed Church of

England (later known as the Congregational Church). This

ideal lasted only a few decades before secularization and

democratization began to dilute the religious character of

the M

ASSACHUSETTS COLONY

. Nevertheless, the early reli-

gious principles of the Pilgrims and Puritans helped estab-

lish a cultural pattern that persisted broadly well into the

20th century. The decline of Puritan influence in state

affairs by the late 17th century foreshadowed the religious

tolerance that would be commonly practiced in the Amer-

ican colonies and later in the United States. Among the

early British settlements in North America were other

colonies founded principally for religious reasons. M

ARY

-

LAND COLONY

was established as a haven for persecuted

Roman Catholics; R

HODE

I

SLAND COLONY

and P

ENN

-

SYLVANIA COLONY

both developed in response to the per-

secution of Baptists and Q

UAKERS

, respectively, and were

established with religious freedom as a fundamental prin-

ciple. Just as internal mobility had been common in En-

gland and within the British Isles, it was endemic in

southwestern Germany, Switzerland, and the Low Coun-

tries (Belgium and the Netherlands). As a result, smaller

religious sects saw immigration as a potential solution to

ongoing political and social disorder. As historian Bernard

Bailyn has observed, “a thousand local rivulets fed streams

of emigrants moving through northern and central Europe

in all directions.” Migration began late in the 17th century

and continued almost unabated until World War I

(1914–18). By the mid-18th century there were already

dozens of Amish (see A

MISH IMMIGRATION

), Mennonites

(see M

ENNONITE IMMIGRATION

), Dunker, and Schwenk-

felder (see S

CHWENKFELDER IMMIGRATION

) settlements,

mostly in Pennsylvania. Gradually, throughout the 18th

century, the power of state religion receded and religious

freedom became the norm throughout the colonies. This

freedom, while not universally changing people’s religious

prejudices, was embodied in the first amendment to the

new United States Constitution of 1789, stipulating that

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment

of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. . . .”

Generally Britain’s Canadian colonies were less officially

tolerant, but by the 1780s, there was little attempt to pun-

ish Catholics or Dissenters. Unlike the new republic to

the south, however, Catholics did not enjoy full rights

until later in the 19th century, when they gradually gained

rights to vote and sit in legislatures.

The first major movements from the German states to

the United States in the 1830s and from Norway and Swe-

den in the 1850s were related to persecution of pietistic sects

in those areas. The much larger migration that followed

until the turn of the century was less generally a religious

movement, though communities established by earlier reli-

gious emigrants made it easier for all immigrants who fol-

lowed. As a result, the religious impulse was important in

immigration beyond the numbers who came to North

America for strictly religious reasons.

Sometimes religion was a characteristic of great but

accidental importance. The Irish had been fleeing their over-

populated island in the tens of thousands since the 1820s

simply to live, and the need was all the greater as a result of

the Great Famine of the 1840s. Though religion was not the

reason for their migration, by the 1850s, they established

an ethnic Catholicism that was unprecedented and in

Canada reinforced the Catholic presence of the French. The

NATIVISM

of the 19th century was significantly anti-

Catholic in character, negatively reinforcing the American

norm of white, Anglo-Saxon Protestantism. Italians too were

almost universally Roman Catholic but feared no religious

persecution in their homelands. That Greeks, Russians, and

Ukrainians were members of Orthodox Christian churches

was only incidental to their decisions to immigrate and their

RELIGION AND IMMIGRATION 251

faith merely one of a dozen strange customs that clouded the

sight of Americans and Canadians.

As nationalism grew as an ideological force throughout

the 19th century, radical communal groups were almost

always viewed hostilely and frequently were persecuted. As

a result, groups of Amish, Mennonite, Doukhobor, and

Hutterite settlers made their way to North America. The

Amish and the Mennonites often settled with or near com-

munities established in the 18th century, while the Hut-

terites and Doukhobors established themselves on the

unsettled prairies of the United States and Canada between

the 1870s and 1910. Their attempts to live communally and

by pacifist principles tested the degree of religious tolerance

afforded in both the United States and Canada. Both coun-

tries placed restrictions on communal living, and antipacifist

sentiment was especially strong in the United States during

World War I.

Although religion was less prominent a factor in driving

the

NEW IMMIGRATION

after 1880, it continued to play an

important role in defining legal tolerance for all religions.

Because Italians, Poles, and many Germans were Roman

Catholic, Catholicism came to be identified with ethnicity.

For specific groups, religion was still the principal reason

for migration. Jews, for instance, faced an intensification of

religious persecution in Russia and Austria after 1880 and

thus looked to the religious freedom of the United States

(especially between 1880 and 1900) and Canada (especially

between 1900 and 1920). Many Jews who came, however,

were not Orthodox, and some openly embraced socialist,

rather than religious, solutions to problems. So, although

old-stock Americans tended to identify people’s religion

with their ethnicity, there was in fact considerable diversity

in the practice of most of the Old World religions once their

practitioners were transplanted to North America. In the

wake of World War II (1939–45) and the ending of colo-

nial empires between 1950 and 1970, Jews continued to

seek freedom of religion in the West.

Canada and the United States proved to be a religious

haven throughout the 20th century. Despite persistent anti-

Semitism, particularly in Quebec, Jews continued to immi-

grate to the United States and Canada, first as refugees from

German-held territories in World War II, and then as

refugees from the officially atheistic Soviet Union. By the

1960s, they had largely entered the cultural mainstream.

Communal groups such as the Mennonites were also driven

from the Soviet Union and found acceptance in the United

States and Canada. More significant in terms of numbers

was the vast influx of non-Protestant settlers coming as a

result of liberalized, nonethnic immigration policies enacted

in the 1960s. Roman Catholic Mexicans and Filipinos and

other immigrants from Latin America; Buddhist Chinese,

Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians; Hindu Indians;

252 RELIGION AND IMMIGRATION

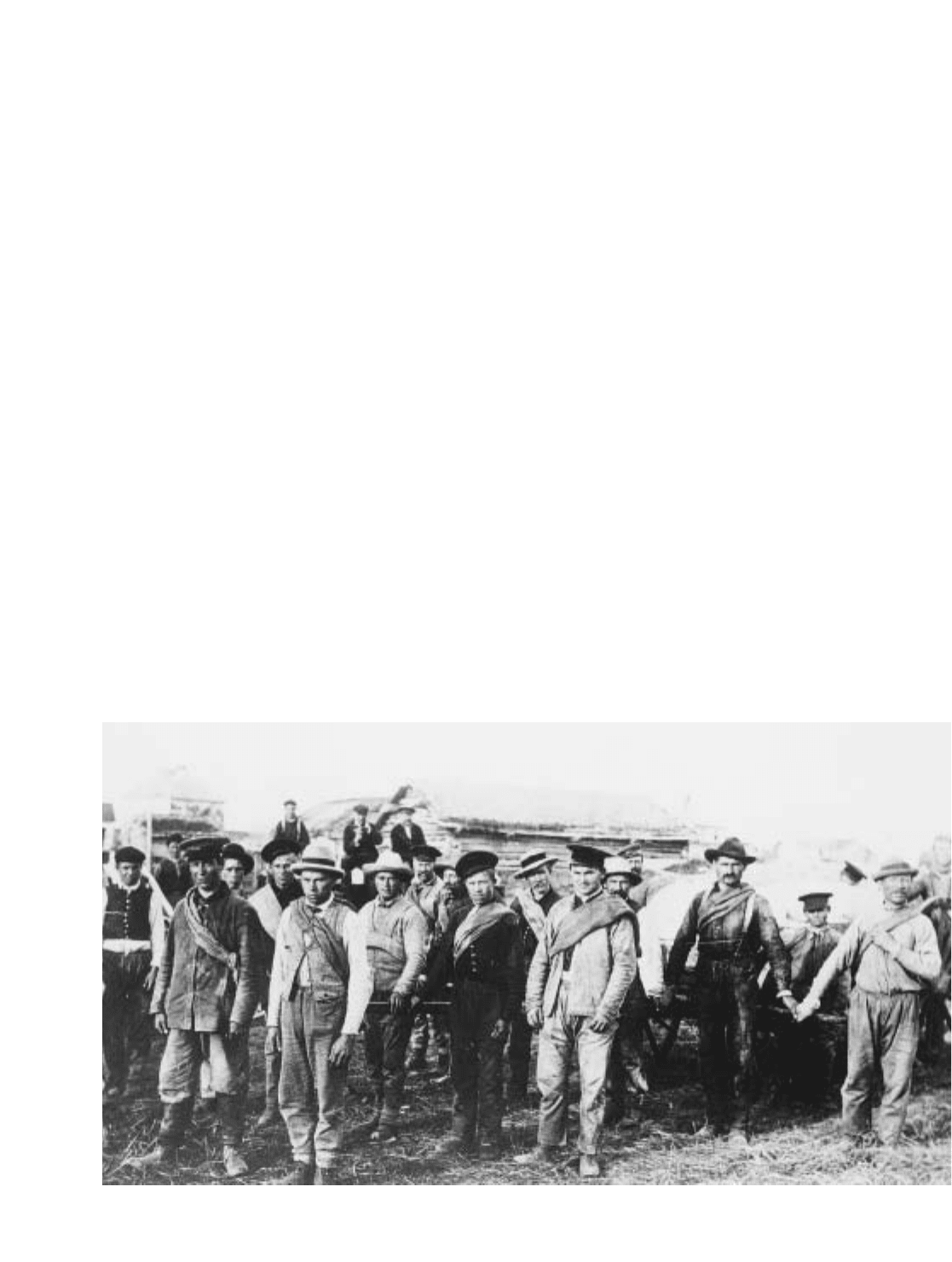

Doukhobors of the Thunder Hill Colony, Manitoba, move supplies from Yorkton, Saskatchewan, to their villages, 1899. Aided by

Leo Tolstoy and Peter Kropotkin, more than 7,500 Doukhobors escaped czarist persecution to settle in the Canadian West after

1889.

(National Archives of Canada/PA-005209)

and Muslim Indians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Iranians,

Egyptians, and Palestinians significantly changed the char-

acter of many areas, including California generally, and espe-

cially the major metropolitan areas of Los Angeles and San

Francisco, California; Houston, Texas; Seattle, Washington;

Toronto, Ontario; and Montreal, Quebec. The United

States and Canada continually affirmed the freedom of reli-

gious practice. Despite occasional outbreaks of nativism,

notably in the wake of the S

EPTEMBER

11, 2001, terrorist

attacks, which were broadly associated with Islamic religious

extremism, there were few overt attacks on members of reli-

gious minorities, and when there were attacks, they were

prosecuted criminally.

Further Reading

Abramson, Harold J. Ethnic Diversity in Catholic America. New York:

Wiley

, 1973.

Alexander, June. The Immigrant Church and Community: Pittsburgh’s

Slo

vak Catholics and Lutherans, 1880–1915. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Uni-

versity of P

ittsburgh Press, 1987.

Balmer, Randall. A Perfect Babel of Confusion: Dutch Religion and

English C

ulture in the Middle Colonies. New York: Oxford Uni-

versity P

ress, 1989.

Burns, Jeffrey M., et al., eds. Keeping Faith: European and Asian

Catholic Immigrants. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2000.

D

olan, J

ay P. The Immigrant Church: New York’s Irish and German

Catholics: 1815–1865. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Pr

ess, 1975.

Fenton, John Y. South Asian Religions in the Americas: An Annotated

Bibliogr

aphy of Immigrant Religious Traditions. Westport, Conn.:

Gr

eenwood Press, 1995.

———. Transplanting Religious Tr

aditions: Asian Indians in America.

New York: Praeger, 1988.

Gaustad, Edwin Scott. A R

eligious Histor

y of America. 2d ed. San Fran-

cisco: Harper and Row, 1990.

Kim, Jung Ha, and Pyong Gap Min, eds. Religions in Asian America:

Building F

aith Communities. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira

Pr

ess, 2001.

Koszegi, Michael A., and J. Gordon Melton, eds. Islam in North Amer-

ica: A Sourcebook. New York: G

arland, 1992.

M

cCaffrey, Lawrence. The Irish Catholic Diaspora in America. Wash-

ington, D.C.: Catholic Univ

ersity of America Press, 1997.

Murphy, Andrew R. Conscience and Community: Revisiting Toleration

and Religious Dissent in Early Moder

n England and America. Uni-

versity Park: P

ennsylvania State University Press, 2001.

Numrich, Paul David. Old Wisdom in the New World: Americanization

in Two Immigr

ant Theravada Buddhist Temples. Knoxville: Uni-

v

ersity of Tennessee Press, 1996.

Podell, Jane, ed. Buddhists, Hindus, and Sikhs in America. New York:

Oxford U

niversity Press, 2001.

Prebish, Charles S., and Kenneth K. Tanaka, eds. The Faces of Bud-

dhism in America. B

erkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Seager

, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America. New York: Columbia

University Press, 1999.

S

mith,

Timothy. “Religion and Ethnicity in America.” American His-

torical Review 83 (D

ecember 1978): 1,155–1,185.

Stephenson, G. M. The Religious Aspects of Swedish Immigration. M

in-

neapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1932.

Williams, Raymond. Religions of Immigrants from India and Pakistan:

New

Thr

eads in the American Tapestry. Cambridge: Cambridge

Univ

ersity Press, 1988.

Zakai, Avihu. Exile and Kingdom: History and Apocalypse in the Puri-

tan M

igr

ation to America. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ

ersity

Press, 1992.

revolutions of 1848

Throughout 1848, a series of liberal revolutions swept

across most of western and central Europe, offering the

promise of greater political and religious freedoms. The

revolts began in Paris, France, in February. As word spread

to liberals elsewhere, uprisings followed in Austria-Hun-

gary, Italy, and the German states, leading to the estab-

lishment of representative assemblies. The most promising

of these, the Frankfurt parliament, wrote a liberal consti-

tution but found no solution to the grossdeutsch (greater

G

ermany) v

ersus kleindeutsch (smaller Germany) prob-

lem and was eventually dispersed by J

une 1849. By the

end of 1849, virtually all the old regimes had been

restored, driving thousands of revolutionaries and their

associates into exile.

The fact that there were still 39 separate German states

after settlement of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 meant that

there was almost continuous political debate over the fate

of both individual states and the collective nation of the

Germans. The handful of men and women who emigrated

for purely political reasons after the Carlsbad Decrees of

1819 or the repression of the early 1830s was only a tiny

fraction of the approximately 160,000 Germans who came

to the United States between 1820 and 1840. Following

the failed revolutions of 1848, the numbers increased. Still,

of some 750,000 German immigrants between 1848 and

1854, only a few thousand were actual political refugees.

Most Germans were responding to significant economic and

social changes that made the old way of life more difficult.

The majority of the exiled leaders stayed in Europe, with

London, England, a favored destination. The most notable

effect of the revolutions in the United States was to provide

an already skilled and hardworking people with a solid core

of professional leadership that eased German transition into

the professions and ultimately into the mainstream of Amer-

ican life.

Further Reading

Kamphoefner, Walter

. The Westphalians: From Germany to Missouri.

Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987.

Moltmann, G

unter. “German Emigration to the United States in the

First Half of the Nineteenth Century as a Form of Social

Protest.” In Germany and A

merica. Ed. Hans Trefousse. New

York: Brooklyn College Press, 1980.

REVOLUTIONS OF 1848 253