Townsend C.R., Begon M., Harper J.L. Essentials of Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

6.3.2 Character displacement in Canadian sticklebacks

If character displacement has ultimately been caused by competition, then the

effects of competition should decline with the degree of displacement. Brook

sticklebacks, Culaea inconstans, coexist in some Canadian lakes with ninespine

sticklebacks, Pungitius pungitius (the species are ‘sympatric’), whereas in other

lakes brook sticklebacks live alone. In sympatry, the brook sticklebacks possess

significantly shorter gill rakers (more suited for foraging in open water), longer

jaws and deeper bodies. We can consider the brook sticklebacks living alone as

having pre-displacement morphology and the sympatric brook sticklebacks as

post-displacement phenotypes. When each phenotype was placed separately in

enclosures in the presence of ninespine sticklebacks, the pre-displacement brook

sticklebacks grew significantly less well than their sympatric post-displacement

counterparts (Figure 6.12). This is clearly consistent with the hypothesis that the

post-displacement phenotype has evolved to avoid competition, and hence

enhance fitness, in the presence of ninespine sticklebacks.

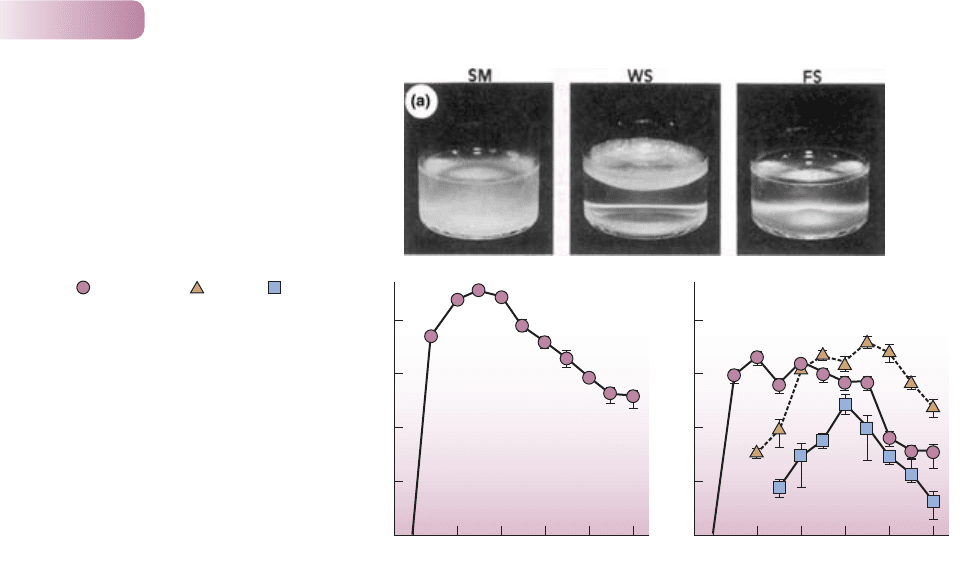

6.3.3 Evolution in action: niche-differentiated bacteria

The most direct way of demonstrating the evolutionary effects of competition within

a pair of competing species is for the experimenter to induce these effects – impose

the selection pressure (competition) and observe the outcome. Surprisingly

perhaps, there have been very few successful experiments of this type. To find an

example of niche differentiation giving rise to coexistence of competitors in a

selection experiment, we must turn away from interspecific competition in the

strictest sense to competition between three types of the same bacterial species,

Pseudomonas fluorescens, which behave as separate species because they reproduce

asexually. The three types are named ‘smooth’ (SM), ‘wrinkly spreader’ (WS) and

‘fuzzy spreader’ (FS), on the basis of the morphology of their colonies plated

out on solid medium. In liquid medium they also occupy quite different parts of

the culture vessel (Figure 6.13a), that is, they have separate niches. In vessels that

were continually shaken, so that no separate niches could be established, an

initially pure culture of SM individuals retained its purity (Figure 6.13b). But in

the absence of shaking, WS and FS mutants arose in the SM population, increased

in frequency and established themselves (Figure 6.13c): evolution had favored

niche differentiation and the consequent avoidance of competition.

Chapter 6 Interspecific competition

199

AFTER GRAY & ROBINSON, 2001

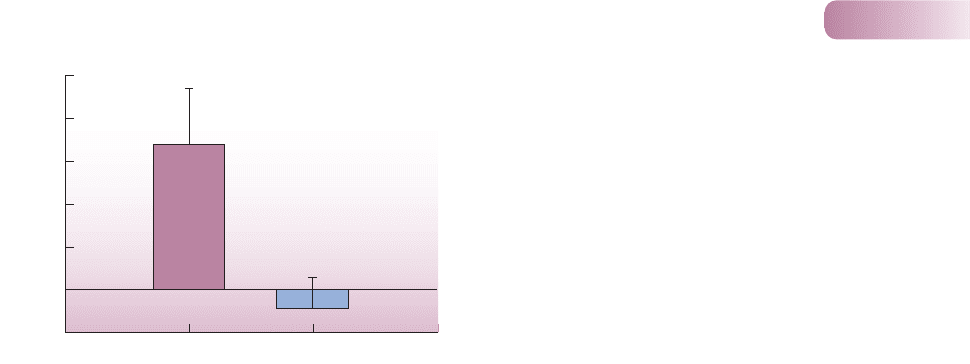

Sympatric Alone

–0.03

0.00

0.03

0.06

0.09

0.12

0.15

Brook stickleback median growth

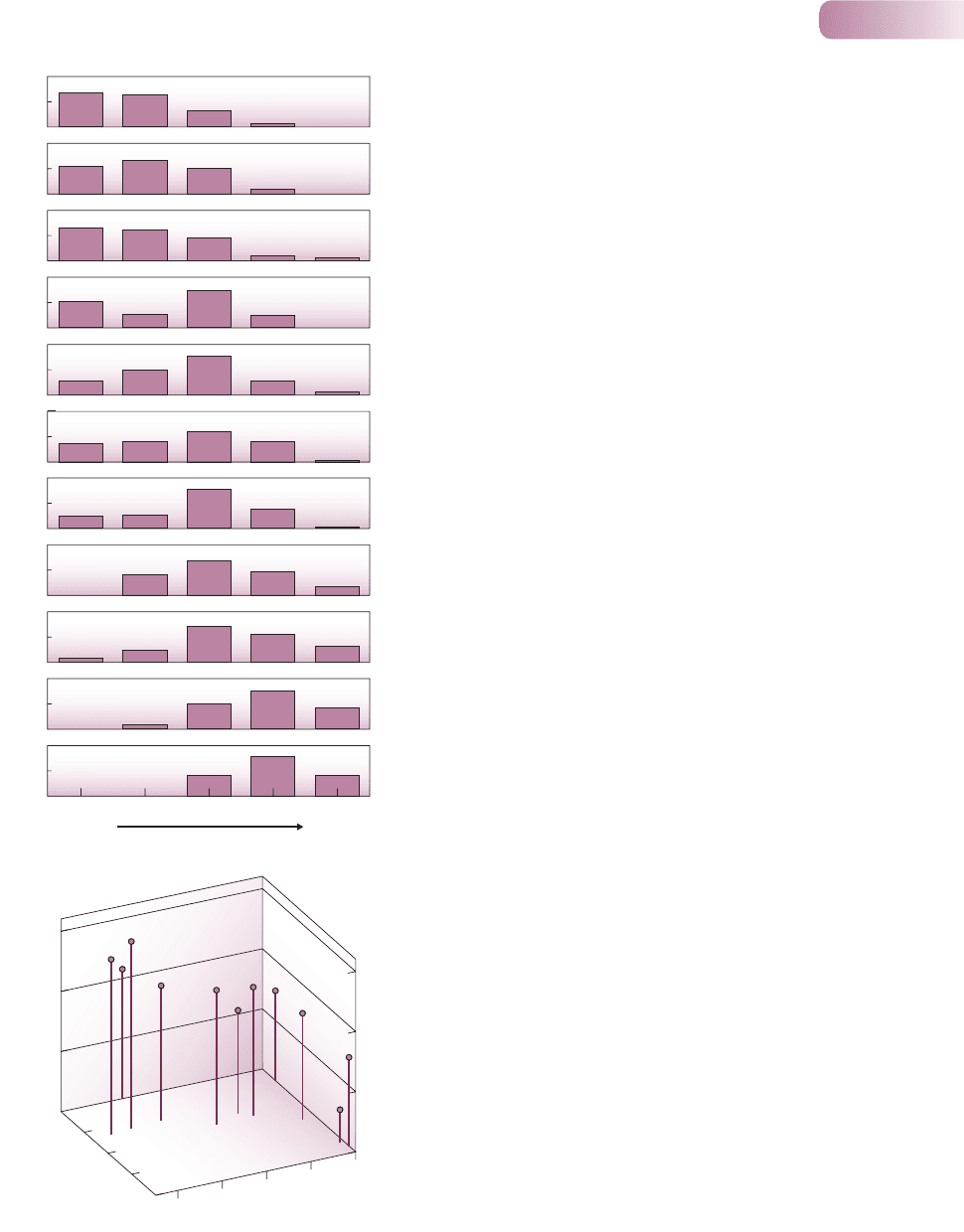

Figure 6.12

Means (with standard errors) of group median growth (natural log of

the final mass of fish in each enclosure divided by the initial mass

of the group) for sympatric brook sticklebacks, representing post-

displacement phenotypes (maroon bar), and brook sticklebacks living

alone, representing pre-displacement phenotypes (blue bar), both

reared in the presence of ninespine sticklebacks. In competition

with ninespine sticklebacks, growth was significantly greater for

post-displacement vs pre-displacement phenotypes (P = 0.012).

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 199

6.4 Interspecific competition and

community structure

Interspecific competition, then, has the potential to either keep apart (Section 6.2)

or drive apart (Section 6.3) the niches of coexisting competitors. How can these

forces express themselves when it comes to the role of interspecific competition

in molding the shape of whole ecological communities – who lives where and

with whom?

6.4.1 Limiting resources and the regulation of diversity

in phytoplankton communities

We begin by returning to the question of coexistence of competing phytoplankton

species. In Section 6.2.4, we saw how two diatom species could coexist in the

laboratory on two shared limiting resources – silicate and phosphate. In fact,

theory predicts that the diversity of coexisting species should be proportional

to the number of resources in a system that are at physiological limiting levels

(Tilman, 1982): the more limiting resources, the more coexisting competitors.

A direct test of this hypothesis examined three lakes in the Yellowstone region

of Wyoming, USA using an index (Simpson’s index) of the species diversity of

phytoplankton there (diatoms and other species). If one species exists on its own,

the index equals 1; in a group of species where biomass is strongly dominated

by a single species, the index will be close to 1; when two species exist at equal

biomass, the index is 2; and so on. According to the theory, therefore, this index

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

200

0246810 0246810

(b) (c)

Number of bacteria (ml

–1

)

10

10

10

9

10

8

10

7

10

6

10

10

10

9

10

8

10

7

10

6

Time (day)

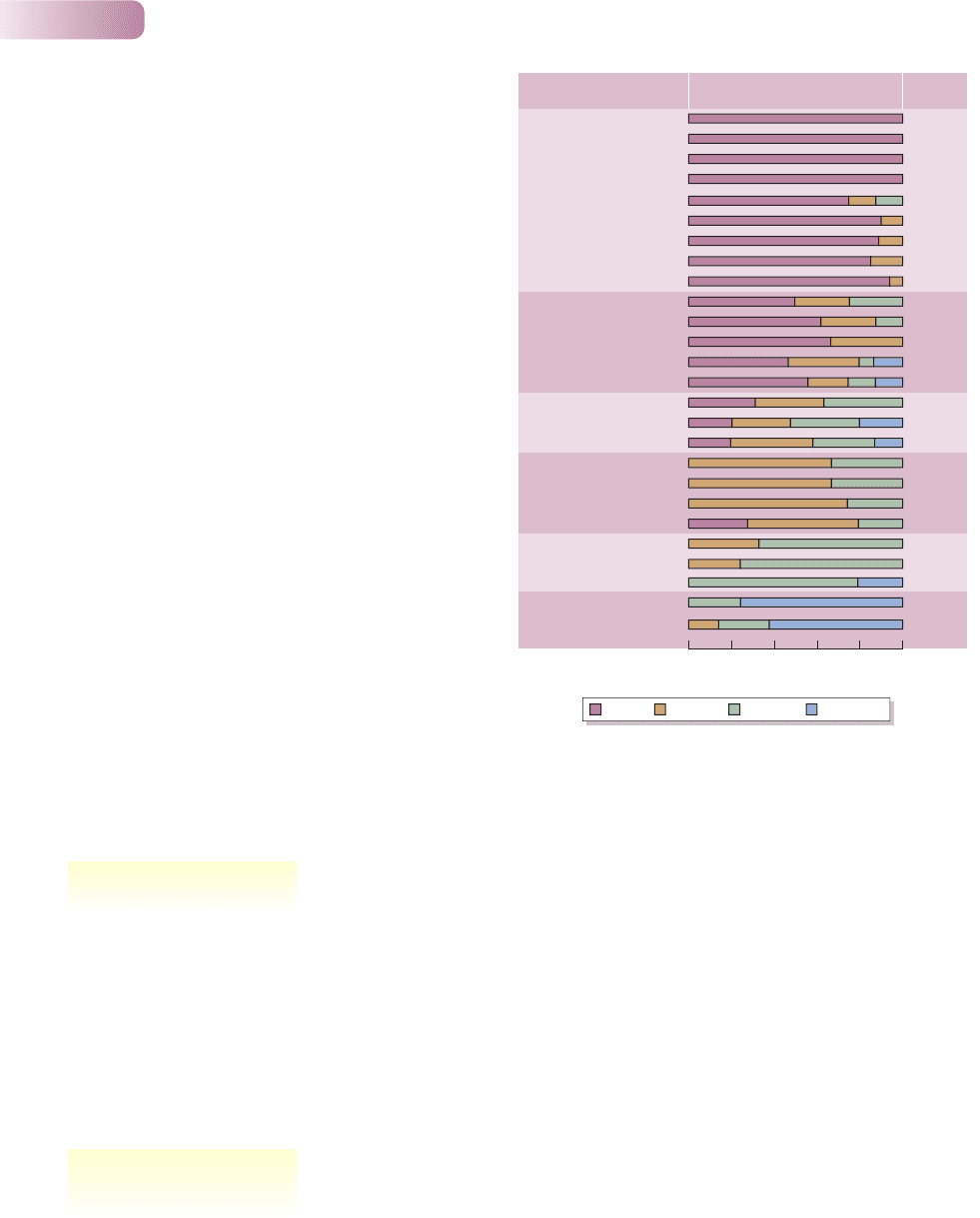

Figure 6.13

(a) Pure cultures of three types of the

bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens

(smooth, SM; wrinkly spreader, WS;

fuzzy spreader, FS) concentrate their

growth in different parts of a liquid

culture vessel. (b) In shaken culture

vessels, pure SM cultures are

maintained. Bars are standard errors.

(c) But in unshaken, initially pure SM

( ) cultures, WS ( ) and FS ( )

mutants arise, invade and establish.

Bars are standard errors.

AFTER RAINEY & TREVISANO, 1998, BY PERMISSION OF NATURE

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 200

should increase in direct proportion to the number of resources limiting growth.

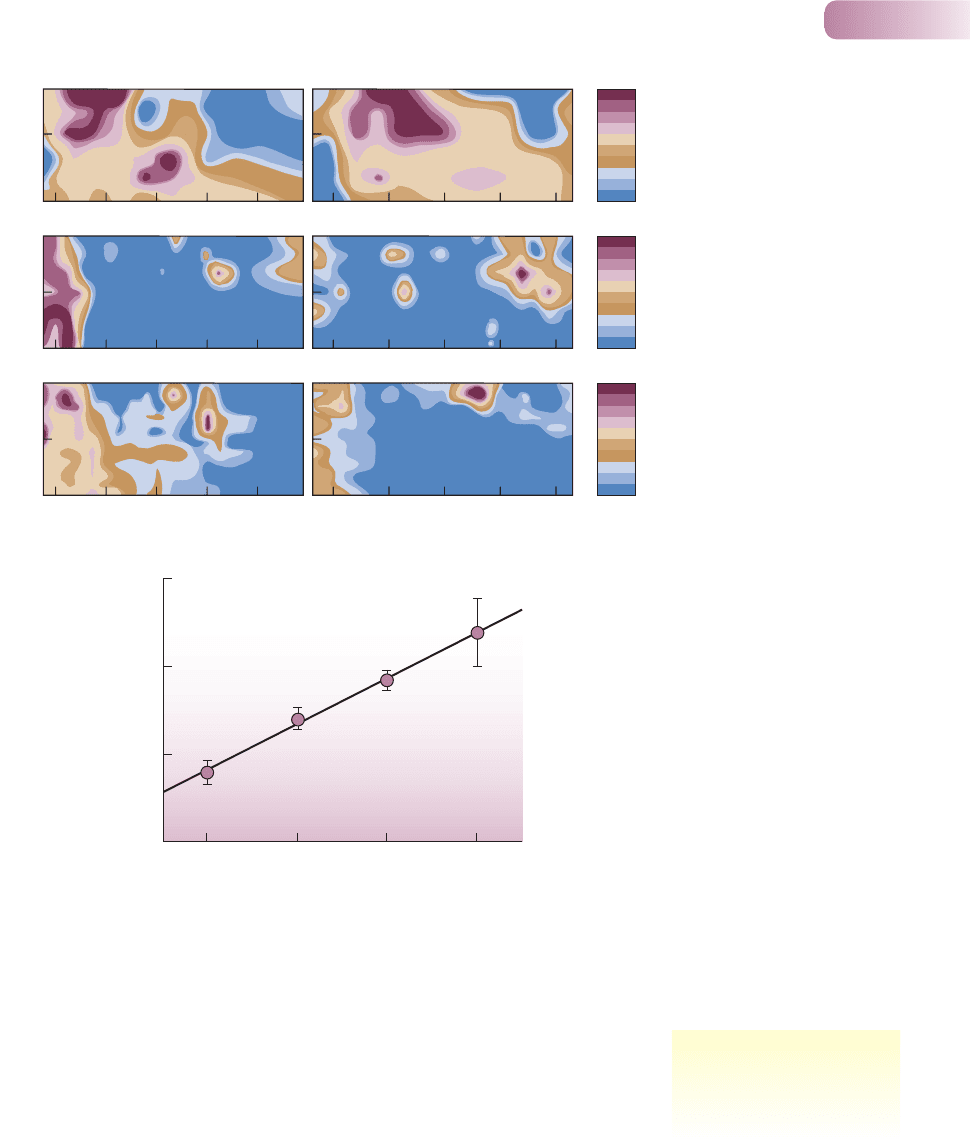

The spatial and temporal patterns in phytoplankton diversity in the three lakes

for 1996 and 1997 are shown in Figure 6.14a.

The principal limiting resources for phytoplankton growth are nitrogen, phos-

phorus, silicon and light. These parameters were measured at the same depths

and times that the phytoplankton were sampled, and it was noted where and when

any of the potential limiting factors actually occurred at levels below threshold

limits for growth. Consistent with the theory, species diversity increased as the

number of resources at physiologically limiting levels increased (Figure 6.14b).

This suggests that even in the highly dynamic environments of lakes, where

equilibrium conditions are rare, resource competition plays a role in continu-

ously structuring the phytoplankton community. It is heartening that the results

Chapter 6 Interspecific competition

201

FROM INTERLANDI & KILHAM, 2001, WITH PERMISSION

Depth (m)

50

25

0

MJ J AS M J J A S

30

15

0

25

10

0

Date

Simpson’s

diversity

index

96>> 97>>

7

5

1

6

4

1

6

4

1

Lewis

Jackson

Yellowstone

(a)

1

1234

2

3

4

Measured limiting resources

(b)

Simpson’s diversity index

r

2

= 0.996

n = 23 n = 84 n = 100 n = 14

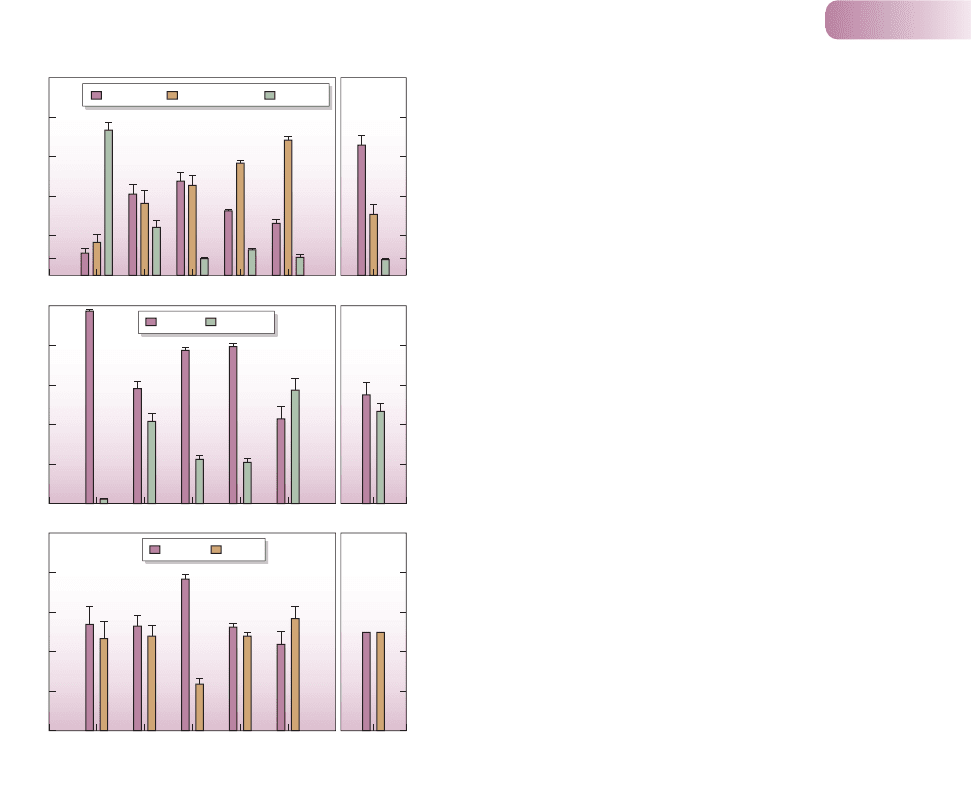

Figure 6.14

(a) Variation in phytoplankton

species diversity (Simpson’s index)

with depth in 2 years in three large

lakes in the Yellowstone region.

Color indicates depth–time variation

in a total of 712 discrete samples;

maroon denotes high species

diversity, blue denotes low species

diversity. (b) Phytoplankton diversity

(Simpson’s index; mean ± SE)

associated with samples with

different numbers of measured

limiting resources. It was possible

to perform this analysis on 221

samples from those displayed in (a);

the number of samples (n) in each

limiting resource class is shown.

Diversity clearly increases with the

number of limiting resources.

as predicted, highest

phytoplankton diversity

occurred where many

resources were limiting

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 201

of experiments performed in the artificial world of the laboratory (Section 6.2.4)

are echoed here in the much more complex natural environment.

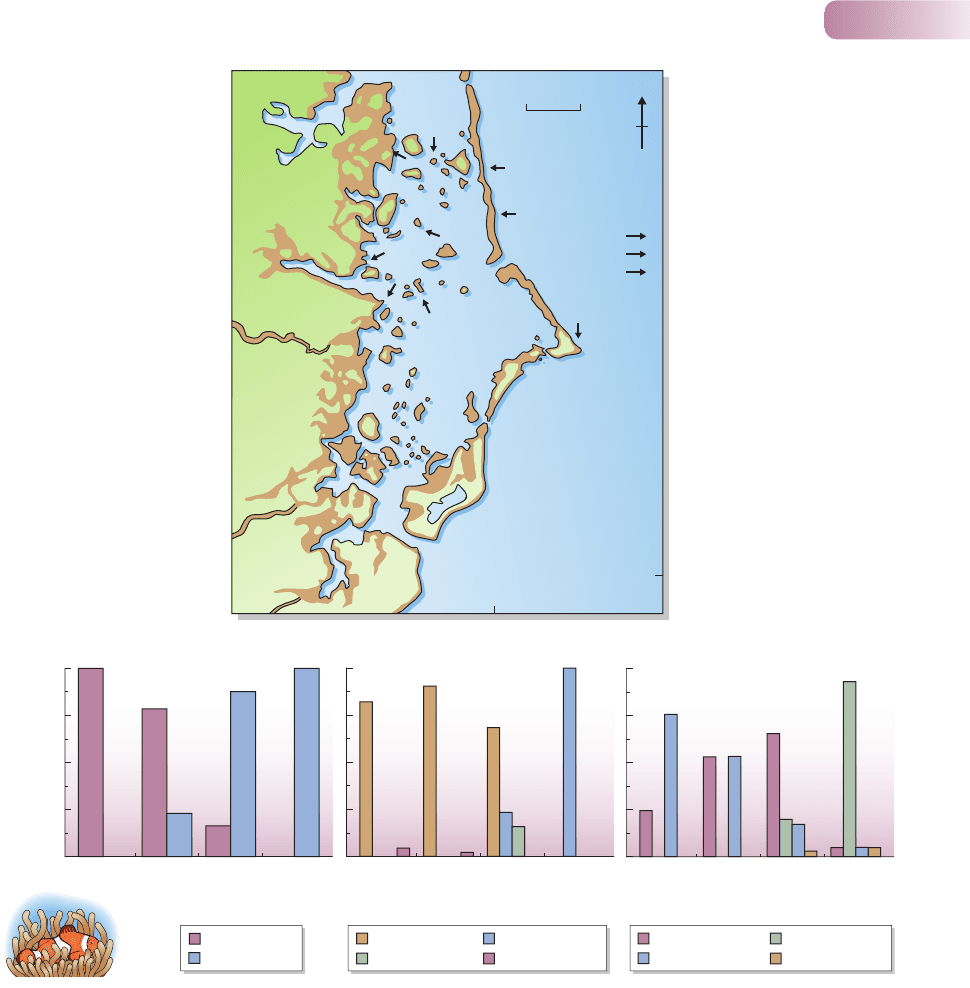

6.4.2 Niche complementarity amongst anemone fish

in Papua New Guinea

In another study of niche differentiation and coexistence, a number of species of

anemone fish were examined near Madang in Papua New Guinea. This region has

the highest reported species richness of both anemone fish (nine) and their host

anemones (10). Each individual anemone tends to be occupied by individuals

of just one species of anemone fish, because the residents aggressively exclude

intruders. However, aggressive interactions were less frequently observed between

anemone fish of very different sizes. Anemones seem to be a limiting resource for

the fish in that almost all anemones were occupied, and when some were trans-

planted to new sites they were quickly colonized. Surveys in four zones (nearshore,

mid-lagoon, outer barrier reef and offshore: Figure 6.15a) showed that each

anemone fish was primarily associated with a particular species of anemone;

each also showed a characteristic preference for a particular zone (Figure 6.15b).

Crucially, moreover, anemone fish that lived with the same anemone were typic-

ally associated with different zones. For example, Amphiprion percula occupied

the anemone Heteractis magnifica in nearshore zones, while A. perideraion

occupied H. magnifica in offshore zones. Finally, associated with the lowered level

of aggression, small anemone fish species (A. sandaracinos and A. leucokranos)

were able to cohabit the same anemone with larger species.

Two important points are illustrated here. First, the anemone fish demon-

strate niche complementarity; that is, niche differentiation involves several niche

dimensions: species of anemone, zone on the shore and, almost certainly, some

other dimension, perhaps food particle size, reflected in the size of the fish. Fish

species that occupy a similar position along one dimension tend to differ along

another dimension. Second, the fish can be considered to be a guild, in that they

are a group of species that exploit the same class of environmental resource in a

similar way, and insofar as interspecific competition plays a role in structuring

communities, it tends to do so, as here, not by affecting some random sample of

the members of that community, nor by affecting every member, but by acting

within guilds.

6.4.3 Species separated in space or in time

In spite of the many examples where there is no direct connection between

interspecific competition and niche differentiation, there is no doubt that niche

differentiation is often the basis for the coexistence of species within natural

communities. There are a number of ways in which niches can be differentiated.

One, as we have seen, is resource partitioning or differential resource utilization.

This can be observed when species living in precisely the same habitat neverthe-

less utilize different resources. In many cases, however, the resources used by

ecologically similar species are separated spatially. Differential resource utilization

will then express itself as either a microhabitat differentiation between the species

(different species of fish, say, feeding at different depths) or even a difference in

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

202

species similar in one dimension

tend to differ in another

dimension

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 202

geographic distribution. Alternatively, the availability of the different resources

may be separated in time; that is, different resources may become available at

different times of the day or in different seasons. Differential resource utilization

may then express itself as a temporal separation between the species.

Chapter 6 Interspecific competition

203

N

OS 3

O3

O2

M1

N1

N2

N3

M2

O1

M3

OS 2

OS 1

Madang

01

(a)

(b)

100

75

50

25

0

Nearshore Mid-

lagoon

Fish

species

A. percula

A. perideraion

A. clarkii

A. leucokranos

A. clarkii

A. sandaracinos

A. chrysopterus

A. melanopus

A. chrysopterus

A. leucokranos

n = 4 n = 17 n = 54 n = 25

n = 102 n = 8 n = 80 n = 7

n = 4 n = 80 n = 28 n = 80

Outer

barrier

OffshoreNearshore Mid-

lagoon

Outer

barrier

OffshoreNearshore Mid-

lagoon

Outer

barrier

Offshore

Stichodactyla mertensii

Heteractis crispa

Heteractis magnifica

Anemones occupied by each

fish species (%)

Nagada

Harbor

Madang

Lagoon

Bismarck Sea

145° 50’ E

5° 13’ S

km

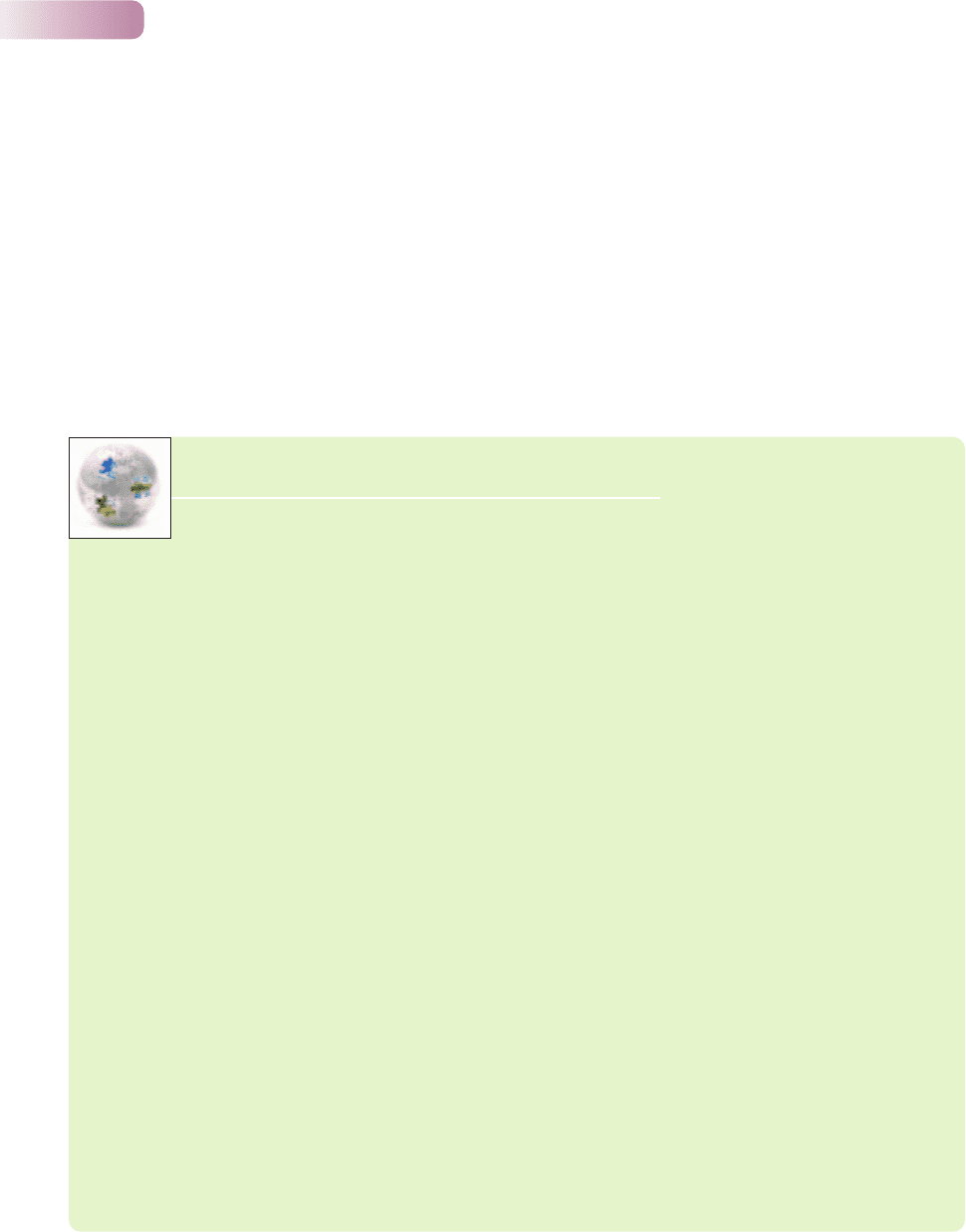

Figure 6.15

(a) Map showing the location of three replicate study sites in each of four zones within and outside Madang Lagoon (N, nearshore; M, mid-lagoon;

O, outer barrier reef; OS, offshore reef). The blue areas indicate water, brown shading represents coral reef, and green represents land.

(b) The percentage of three common species of anemone (Heteractis magnifica, H. crispa and Stichodactyla mertensii) occupied by different

anemone fish species (Amphiprion spp., in key below) in each of the four zones. The number of anemones censused in each zone is shown by n.

AFTER ELLIOTT & MARISCAL, 2001

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 203

The other major way in which niches can be differentiated is on the basis of

conditions. Two species may use precisely the same resources, but if their ability

to do so is influenced by environmental conditions (as it is bound to be), and

if they respond differently to those conditions, then each may be competitively

superior in different environments. This too can express itself as either a micro-

habitat differentiation, or a difference in geographic distribution, or a temporal

separation, depending on whether the appropriate conditions vary on a small

spatial scale, a large spatial scale or over time. Of course, it is not always easy to

distinguish between conditions and resources, especially with plants (see Chapter 3).

Niches may then be differentiated on the basis of a factor (such as water), which

is both a resource and a condition.

6.4.4 Spatial separation in trees and tree-root fungi

Trees vary in their capacity to use resources such as light, water and nutrients.

A study in Borneo of 11 tree species in the genus Macaranga showed marked

differentiation in light requirements, from extremely light-demanding species

such as M. gigantea to shade-tolerant species such as M. kingii (Figure 6.16a).

Average light levels intercepted by the crowns of trees tended to increase as they

grew larger, but the ranking of the species did not change. The shade-tolerant

species were smaller (Figure 6.16b) and persisted in the understorey, rarely estab-

lishing in disturbed microsites (e.g. M. kingii), in contrast to some of the larger,

high-light species that are pioneers of large forest gaps (e.g. M. gigantea). Others

were associated with intermediate light levels and can be considered small-gap

specialists (e.g. M. trachyphylla). The Macaranga species were also differentiated

along a second niche gradient, with some species being more common on clay-rich

soils and others on sand-rich soils (Figure 6.16b). This differentiation may be

based on nutrient availability (generally higher in clay soils) and/or soil moisture

availability (possibly lower in the clay soils because of thinner root mats and

humus layers). Hence, as with the anemone fish, there is evidence of niche com-

plementarity: species with similar light requirements tended to differ in terms of

preferred soil textures. In addition, though, the apparent niche partitioning by

Macaranga species was partly related to space horizontally (variation in soil types

and in light levels from place to place) and partly to space vertically (height in the

canopy, depth of the root mat).

Differential resource utilization in the vertical plane has also been demon-

strated for fungi intimately associated with plant roots (ectomycorrhizal fungi;

see Section 8.4.5) in the floor of a forest of pine, Pinus resinosa (Figure 6.17).

Until recently, it was not possible to study the distribution of ectomycorrhizal

species in their natural environment. Now DNA analyses make this possible and

allow their distributions to be compared. The forest soil has a well-developed litter

layer above a fermentation layer (F layer) and a thin humified layer (H layer),

with mineral soil beneath (B horizon). Of the 26 species separated by the DNA

analysis, some were very largely restricted to the litter layer (group A in Figure 6.17),

others to the F layer (group D), the H layer (group E) or the B horizon (group F).

The remaining species were more general in their distributions (groups B and C).

This is therefore an example of where a spatial (microhabitat) separation cannot

simply be ascribed to one resource or condition: there are no doubt several that

vary with the soil layers.

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

204

trees in Borneo: height, depth,

gaps and soil

separation with depth in

ectomycorrhizal fungi

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 204

Chapter 6 Interspecific competition

205

% all trees

High light

Crown illumination index

Low light

(a)

54321

60

0

2.0

K (n = 20)

60

0

2.1

L (n = 255)

60

0

2.6

U (n = 229)

60

0

2.8

V (n = 103)

60

0

3.2

A (n = 226)

60

0

3.5

B (n = 222)

60

0

3.4

T (n = 215)

60

0

3.6

Y (n = 35)

60

0

4.0

H (n = 115)

60

0

4.0

W (n = 103)

60

0

Mean Cl = 4.2

G (n = 42)

30

20

10

75

65

55

45

35

40

30

20

10

0

30

20

10

0

% trees in high light

% trees on

sand-rich soils

Maximum tree height (m)

G

W

H

Y

T

A

B

K

U

L

V

(b)

Figure 6.16

(a) Percentage of individuals in each of five crown illumination (CI)

classes for 11 Macaranga species (sample sizes in parentheses).

(b) Three-dimensional distribution of the 11 species with respect

to maximum height, the proportion of stems in high light levels

[class 5 in (a)] and proportion of stems in sand-rich soils. Each

species of Macaranga is denoted by a single letter. G, gigantean;

W, winkleri; H, hosei; Y, hypoleuca; B, beccariana; T, triloba;

A, trachyphylla; V, havilandii; U, hullettii; L, lamellate; K, kingii.

AFTER DAVIES ET AL., 1998

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 205

6.4.5 Temporal separation in mantids and

tundra plants

One common way in which resources may be partitioned over time is through

a staggering of life cycles through the year. It is notable that two species of

mantids, which feature as predators in many parts of the world, commonly

coexist both in Asia and North America. Tenodera sinensis and Mantis religiosa

have life cycles that are 2–3 weeks out of phase. To test the hypothesis that this

asynchrony serves to reduce interspecific competition, the timing of their egg

hatch was experimentally synchronized in replicated field enclosures (Hurd &

Eisenberg, 1990). T. sinensis, which normally hatches earlier, was unaffected by

M. religiosa. In contrast, the survival and body size of M. religiosa declined in the

presence of T. sinensis. Because these mantids are both competitors for shared

resources and predators of each other, the outcome of this experiment probably

reflects a complex interaction between the two processes.

In plants too, resources may be partitioned in time. Thus, tundra plants grow-

ing in nitrogen-limited conditions in Alaska are differentiated in their timing

of nitrogen uptake, as well as the soil depth from which it is extracted and the

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

206

Percentage occurrences

1000 20406080

Species Vertical distribution Group

A

B

C

D

E

F

Litter F layer H layer B horizon

Unknown species 009

Unknown species 010

Unknown species 007

Unknown species 008

Unknown species 006

Unknown species 005

Unknown species 001

Unknown species 002

Unknown species 003

Unknown species 004

Unknown species 014

Unknown species 013

Unknown species 015

Ramaria concolor

Tylopilus felleus

Lactarius sp.

Trichoderma sp.

Scleroderma citrinum

Russula sp. (white 1)

Clavulina cristata

Cenococcum geophilum

Suillus intermedius

Clavarioid 2

Russula sp. (white 2)

Amanita rubescens

Amanita vaginata

Figure 6.17

The vertical distribution of 26 ectomycorrhizal fungal species in the

floor of a pine forest determined by DNA analysis. Most have not

formally been named but are shown as a code. Vertical distribution

histograms show the percentage of occurrences of each species

in the litter (maroon), F layer (yellow), H layer (green) and

B horizon (blue).

AFTER DICKIE ET AL., 2002

staggered life cycles in mantids

nitrogen, depth and time in

Alaskan plants

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 206

chemical form of nitrogen used. To trace how tundra species differed in uptake

of different nitrogen sources, McKane et al. (2002) injected three chemical forms

labeled with the rare isotope

15

N (ammonium, nitrate and glycine) at two soil

depths (3 and 8 cm) on two occasions (June 24 and August 7). Concentration of

the

15

N tracer was measured in each of five common tundra plants 7 days after

application. The five plants proved to be well differentiated in their use of nitrogen

sources (Figure 6.18). Cottongrass (Eriophorum vaginatum) and the cranberry bush

(Vaccinium vitis-idaea) both relied on a combination of glycine and ammonium,

but cranberry obtained more of these forms early in the growing season and at

a shallower depth than cottongrass. The evergreen shrub Ledum palustre and

the dwarf birch (Betula nana) used mainly ammonium, but L. palustre obtained

more of this form early in the season while the birch exploited it later. Finally,

the grass Carex bigelowii was the only species to use mainly nitrate. Here, niche

complementarity can be seen along three niche dimensions: nitrogen source,

depth and time.

Chapter 6 Interspecific competition

207

AFTER MCKANE ET AL., 2002

Uptake of available soil nitrogen (% of each species’ total)

Available soil nitro

g

en (% of total)

Available

soil nitrogen

100

0

20

40

60

80

(a)

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

20

40

60

80

(b)

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

20

40

60

80

(c)

Carex

Eriophorum

Vaccinium

Ledum

Betula

3 cm 8 cm

June August

Glycine Ammonium Nitrate

Figure 6.18

Mean uptake of available soil nitrogen (± SE) in terms of

(a) chemical form, (b) timing of uptake and (c) depth of uptake by

the five most common species in tussock tundra in Alaska. Data

are expressed as the percentage of each species’ total uptake

(left panels) or as the percentage of the total pool of nitrogen

available in the soil (right panels).

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 207

6.5 How significant is interspecific

competition in practice?

Competitors may exclude one another, or they may coexist if there is ecologically

significant differentiation of their realized niches (Section 6.2). On the other

hand, interspecific competition may exert neither of these effects if environ-

mental heterogeneity prevents the process from running its course (Section 6.2.8).

Evolution may drive the niches of competitors apart until they coexist but

no longer compete (Section 6.3). All these forces may express themselves at the

level of the ecological community (Section 6.4). Interspecific competition some-

times makes a high profile appearance by having a direct impact on human activity

(Box 6.2). In this sense, competition can certainly be of practical significance.

Part III Individuals, Populations, Communities and Ecosystems

208

6.2 TOPICAL ECONCERNS

6.2 Topical ECOncerns

When exotic plant species are introduced to a new

environment, by accident or on purpose, they some-

times prove to be exceedingly good competitors and

many native species suffer harmful consequences as

a result. Some of them have even more far-reaching

consequences for native ecosystems. This newspaper

article by Beth Daley, published in the Contra Costa

Times on June 27, 2001, concerns grasses that have

invaded the Mojave Desert in the southern United

States. Not only are the invaders outcompeting native

wild flowers, they have also dramatically changed the

fire regime.

Invader grasses endanger desert by

spreading fire

The newcomers crowd out native plants and

provide fuel for once-rare flames to damage

the delicate ecosystem.

Charred creosote bushes dot a mesa in the

Mojave Desert, the ruins of what was likely the

first fire in the area in more than 1000 years.

Though deserts are hot and dry, they aren’t

normally much of a fire hazard because the

vegetation is so sparse there isn’t much to burn

or any way for blazes to spread.

But, underneath these blackened creosote

branches, the cause of the fire seven years ago

has already grown back: flammable grasses fill

the empty spaces between the native bushes,

creating a fuse for the fire to spread again.

Tens of thousands of acres in the Mojave and

other southwestern deserts have burned in the

last decade, fueled by the red brome, cheat

grass and Sahara mustard, tiny grasses and

plants that grow back faster than any native

species and shouldn’t be there in the first place.

. . . The grasses brought to America from

Eurasia more than a century ago have no natural

enemies, and little can stop their spread across

empty desert pavement. And, once an area is

cleared of native vegetation by one or repeated

fires, the grasses grow in even thicker,

sometimes outcompeting native wildflowers and

shrubs.

. . . ‘These grasses could change the entire

makeup of the Mojave Desert in short order’, said

William Schlesinger of Duke University, who has

studied the Mojave Desert for more than 25

years. When he began his research in the 1970s,

the grasses were in the Mojave, but there still

Competition in action

9781405156585_4_006.qxd 11/5/07 14:51 Page 208